Язык историческое явление. Это не остаются неизменными для любого значительного периода времени или в течение любого времени на все, но она постоянно меняется протяжении всей своей истории.

История английского языка является одним из основных курсов, формирующих языковую фон специалиста в филологии. Это показывает место среди английском других языках и обеспечивает более широкий подход к его изучению; это показывает связей английского языка с других германских языках, а также он связывает с языками других групп.

Эволюция английского языка тесно связана с историей английского народа.

Таким образом, объектом истории английского языка язык . Сама его фонетические, грамматические и лексические аспекты

предметом курса является:

• основные изменения в фонетической структуре и орфографии языка на разных этапах развития языка;

• эволюции грамматического строя;

• рост и развитие словарного запаса. Таким образом, предметом нашего курса является изменение характера языка посредством более чем 15 столетий своего существования. Она изучает возникновение и развитие английского языка, его структуры и особенностей в старину, его сходство с другими языками и той же семьи и его уникальных особенностей. Она начинается с видом на началах языке, первоначально диалектов сравнительно небольшое число родственных племен, которые мигрировали с континента на Британские острова, диалектов индоевропейской семьи — синтетический изменяемую язык с хорошо развитой системой именных форм, довольно слабо представлены системы глагольных категорий, с бесплатным слова Порядок и словарный запас, что практически полностью состоял из слов местного происхождения. В фонологии было строгое разделение гласных в длинных и коротких, сравнительно немногих дифтонгов и неразвитая система согласных. Могучие факторы повлияли на язык преобразования его в основном аналитической языке сегодня, с нехваткой номинальных форм и словесной системе, что значительно перевешивает системах многих других европейских языках. Его система гласных богат, его словарный запас огромен. Его написание система довольно запутанной. Цель изучения истории английского языка расследование и систематическое изучение языкового развития с древнейших времен до наших дней. Кроме того изучение истории английского языка студент достигает разнообразие стремится как теоретического, так и практического. 1. Во-первых, обеспечивает студента со знанием лингвистической истории достаточной для объяснения основных черт современного английского языка. Например, через столетия писал и написание меняется на английском языке. В то время, когда латинские буквы были впервые использованы в Великобритании (7 в.) Письмо было фонетическое: буквы стоял тот же звук. После введения печати (15 в.) В письменной форме слова стали фиксированными, в то время как звуки продолжает меняться. Мы столкнулись с рядом особенностей, которые появляются непонятные от современной точки зрения. Эти особенности могут быть найдены в грамматике, фонетике и словарного: любой студент знает о трудностях на чтение и написание слов, где звуки, представленных рядом букв, например: свет, дочь, знаете, и спрашивает, почему сочетание «EA» указывает разные Звучит например: говорить, здорово, услышать, сердце, голову. В сфере лексики имеется значительный сходство между английской и немецкой, например: зимой — дер зима, лето — дер Соммер. Такие черты наблюдаются во многих языках, но мы не можем объяснить их, если мы остаемся в рамках современного английского языка, мы можем только догадываться, что они не являются предметом случайно, и что должно быть какая-то причина позади них. Эти причины относятся к более или менее отдаленное прошлое, и они могут быть обнаружены только собирается в истории английского языка. История английского языка может объяснить, почему некоторые вещества образуют множественное число их изменением корневой гласной, например: человеко-мужчин или почему слова «овец, оленей» имеют неизменным во множественном числе или почему глаголы «должен могут» не принять -s в 3-м лице единственного числа настоящего времени изъявительного. 2. Другой важной целью данного курса носит более теоретический характер. В то время как проследить эволюцию английского языка во времени, студент будет сталкиваться с рядом теоретических вопросов, таких, как отношения между статикой и динамикой в языке, роль лингвистических и экстралингвистических факторов и так далее. Эти проблемы могут быть рассмотрены на теоретическом плане в рамках общей лингвистике. В описании эволюции английского языка, они будут обсуждаться в отношении конкретных языковых фактов, которые обеспечат лучшее понимание этих фактов и демонстрируют применение общих принципов к языкового материала. 3. Еще одна цель этого курса заключается в предоставлении студентам английского языка с более широким филологического мировоззрения. История английского языка показывает место английского языка в языковой мире. Для достижения этих целей студент должен знать теоретические основы предмета и работать с текстом, чтобы применить теоретические знания для практического анализа английских текстов в разные периоды развития языка. Таким образом, основная цель изучения истории английского языка, чтобы объяснить современном этапе языка для того, чтобы студент английского языка, чтобы читать книги и говорить на языке с пониманием усложнить » Механизм «они используют.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Lecture 1

1. What are the basic elements of the relationship between a language and extralinguistic world?

The relation of language to the extralinguistic world involves three basic sets of elements: language signs, mental concepts

and parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing) which are usually called denotata

(Singular: denotatum).

2. What is a language sign, a concept and a denotatum? Give definitions. Show the relation between them?

The LS is a sequence of sounds (in spoken language) or symbols (in written language) which is associated with a single

concept in the minds of speakers of that or another language. Те, що ми написали чи сказали.

The MC is an array of mental images and associations related to a particular part of the extralinguistic world (both really

existing and imaginary), on the one hand, and connected with a particular language sign, on the other. Тлумачення. Яка який

яке?

Denotata- parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing)- object + concept.

Denotatum is the actual object or meaning of a word, rather than the feeling or ideas connected with the word.

The relation between words (language signs) and parts of the extralinguistic world (denotata) is only indirect and going

through the mental concepts.

The relationship between a language sign and a concept is ambiguous: it is often different even in the minds of different

people, speaking the same language, though it has much in common, hence, is recognizable by all the members of the

language speakers community.

3. What is a lexical meaning, a connotation and an association? Give definitions and examples.

LM is the general mental concept corresponding to a word or a combination of words.

noodle — 1. type of paste of flour and water or flour and eggs pre- pared in long, narrow strips and used in soups, with a sauce,

etc.; 2. fool.

Connotation is an additional, contrastive value of the basic usually designative function of the lexical meaning. (emotional

attitude). For example, blue is a color, but it is also a word used to describe a feeling of sadness, as in: “She’s feeling blue.”

Connotations can be either positive, negative, or neutral.

Compare the words to die(померти) and to peg out(здихати). It is easy to note that the former has no connotation, whereas

the latter has a definite connotation of vulgarity.

An association is a more or less regular connection established between the given and other mental concepts in the minds of

the language speakers.

A rather regular association is established between green and fresh {young) and between green and environment protection.

4. What is the range of application of a word? Give examples.

The peculiarities of conceptual fragmentation of the world by the language speakers are manifested by the range of

application of the lexical meanings (reflected in limitations in the combination of words and stylistic peculiarities). This is

yet another problem having direct relation to translation — a translator is to observe the compatibility rules of the language

signs (e. g. make mistakes, but do business).

5. What are the main sources of translation ambiguity stemming from the sign-concept relationship?

The concepts being strongly subjective and largely different in different languages for similar denotata give rise to one of the

most difficult problems of translation, the problem of ambiguity of translation equivalents(неоднозначність

еквівалентів перекладу).

Denotata — parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing)- object + concept.

Denotatum is the actual object or meaning of a word, rather than the feeling or ideas connected with the word.

Another source of translation ambiguity is the polysemantic nature of the language signs: the relationship between the signs

and concepts is very seldom one-to-one, most frequently it is one-to-many or many-to-one, i.e. one word has several meanings

or several words have similar meanings.

Language and Extralinguistic World Lecture 1

Overview • notions of a linguistic sign, concept and denotatum; • relations between linguistic sign, concept and denotatum; • difference between the denotative and connotative meanings of a linguistic sign; • mental concept of a linguistic sign; • relations of polysemy and synonymy • ambiguity of translation equivalents.

Basic Elements Denotatum Mental concept Language sign

Language Sign is a sequence of sounds (in spoken language) or symbols (in written language) which is associated with a single concept in the minds of speakers of that or another language.

Language Sign Vrouw Frau Femeie Kobieta

Mental Concept is an array of mental images and associations related to particular part of the extralinguistic world (both really existing and imaginary), on the other hand, and connected with a particular language sign, on the other

Mental Concept Meet Mr. X. He is an engineer.

THUS Differences in relations between language signs and mental concepts translation difficulties

Mental Concept Elements • • Lexical meanings Connotations Associations Grammatical meanings

Lexical Meaning is the general mental concept corresponding to a word or a combination of words.

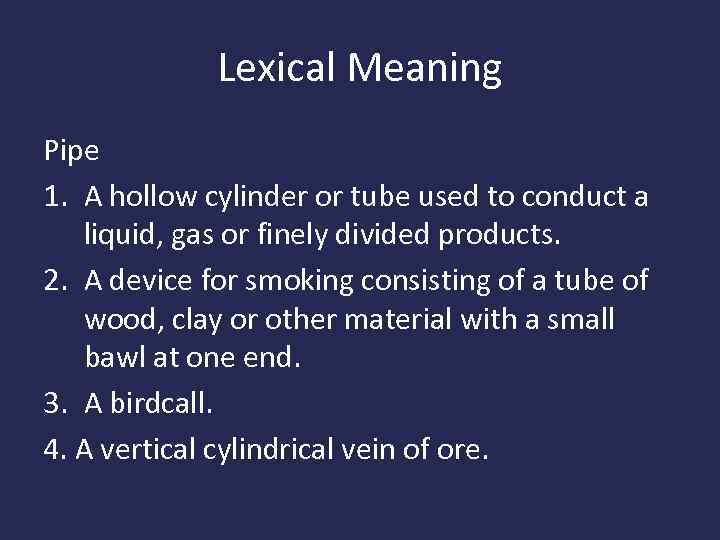

Lexical Meaning Pipe 1. A hollow cylinder or tube used to conduct a liquid, gas or finely divided products. 2. A device for smoking consisting of a tube of wood, clay or other material with a small bawl at one end. 3. A birdcall. 4. A vertical cylindrical vein of ore.

Connotation is an additional, contrastive value of the basic usually designative function of the lexical meaning. Example: To avoid = to back out Fish = fish in oil field ?

Association is a more or less regular connection established between the given and other mental concepts in the minds of the language speakers

Translation Challenges Ambiguity of translation equivalents Polysemy and Synonymy

Изображение слайда

2

Слайд 2: The evolution of the language includes the internal or structural development and “ external” history o f the language

Internal linguistic changes are changes at the:

phonetic and phonological levels ( historical phonetics (phonology ))

morphological level ( historical morphology )

syntactic level ( historical syntax )

lexical level ( historical lexicology )

Изображение слайда

3

Слайд 3: Interdependence of changes at different linguistic levels

The history of noun morphology = simplification:

nouns have lost most of their cases (OE – 4, NE — 2).

Phonetic weakening of final syllables

Analogical levelling of forms at the morphological level

Stabilisation of word order at the level of syntax

OE sunu > ME sune (also spelt sone ) > NE son

Изображение слайда

4

Слайд 4: The external history of the language embraces a number of issues:

the spread of the language in geographical and social space

the differentiation of language into functional varieties (geographical variants, dialects, standard and sub-standard forms, etc.)

contacts with other languages

Изображение слайда

The concept of language space – i.e. the geographical and social space occupied by the language.

The concept of linguistic situation – embraces the functional differentiation of language and the relationships between the functional varieties.

Изображение слайда

6

Слайд 6: Statics and Dynamics in Language History

There are certain permanent universal properties in all languages at any period of time

e.g.the division of sounds into vowels and consonants;

the distinction between the main parts of speech and parts of the sentence.

English has many stable characteristics which have proved almost immune to the impact of time

e.g. some parts of the vocabulary have been preserved through ages: most pronouns, form-words, words denoting basic concepts of life

Изображение слайда

7

Слайд 7: Statics and Dynamics in Language History

e.g. many ways of word-formation have remained historically stable.

e.g. grammatical categories

number in nouns, degrees of comparison in adjectives have suffered little alteration,

case or gender have undergone profound changes.

Statics and dynamics can be found both in synchrony and in diachrony.

Dynamics in diachrony = linguistic change

Изображение слайда

8

Слайд 8: CONCEPT OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE

3 main types of difference in language: geographical, social, temporal.

Linguistic changes imply temporal differences.

Linguistic changes are transformations of the same units in time which can be registered as distinct steps in their evolution.

Изображение слайда

9

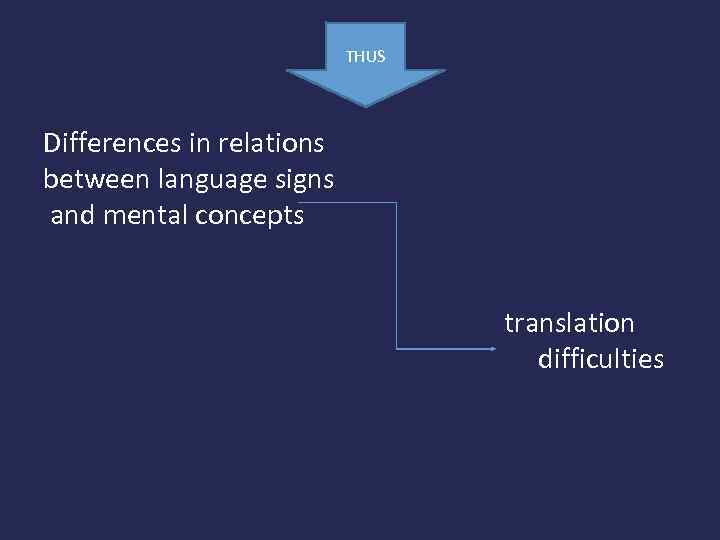

Слайд 9: e.g. OE ME NE to find — fundon [fundon] — founden [f H nden]- found (the Past tense pl of the Ind. Mood) — (Past pl of the Subj. and Part.II) — (the 3 forms had fallen together)

These changes are defined as structural or intralinguistic :

phonetic and spelling changes,

phonetic and morphological changes,

morphological changes in the place of the form in the verb paradigm and its grammatical meaning (it stands now both for the sing and pl since these forms are not distinguished in the Past tense)

Изображение слайда

10

Слайд 10: Replacements are linguistic changes, which involve some kind of substitution. Types of replacements

One-to-one replacement

but [u] > [ A ], feet [e:] > [ J ]; OE ēa > French river

Merging or mergers

the Modern Common case of nouns is the result of the merging of the three OE cases – Nom., Gen., Acc.)

Splitting or split

the consonant [k] has split into [k] and [ C ]

kin, keep vs chin, child

Изображение слайда

Изображение слайда

HISTORICAL CHANGES

A change is historical if it can be shown as a phonetic modification of an earlier form.

e.g. the modern plural ending of nouns — es has descended directly from its prototype, OE -as due to phonetic reduction and loss of the vowel (OE st ān-as vs. NE ston-es )

Both the change and the resulting form are called historical

ANALOGICAL CHANGES

An analogical form does not develop directly from its prototype; it appears on the analogy of other forms, similar in meaning and shape.

e.g. when the plural ending -es

began to be added to nouns which had never taken — as – but had used other endings: -u, -an, -a, — it was a change by analogy or an instance of analogical levelling. This analogical change gave rise to new forms referred to as “analogical” (OE nam-an > NE nam-es )

Изображение слайда

13

Слайд 13: Rate of Linguistic Changes

slow and gradual

is restricted by the communicative function of the language

different levels of the language develop at different rates

Изображение слайда

14

Слайд 14: Lexical level – rapid changes, easy to observe

Phonetic level – changes can not be sudden or rapid since the system of phonemes must preserve the oppositions between the phonemes required for the distinction of morphemes

Grammatical system is very slow to change. As the most abstract level it must provide stable formal devices for arranging words into classes and for connecting them into phrases and sentences.

Изображение слайда

15

Слайд 15: Mechanism of Change. Role of Synchronic variation

A linguistic change begins with synchronic variation (formal and semantic).

Synchronic variation is found in every language at every stage of its history.

It is caused by functional differentiation and tendencies of historical development.

New features, which appear as instances of synchronic variation, represent dynamics in synchrony and arise in conformity with productive historical trends

Изображение слайда

Изображение слайда

17

Слайд 17: Causes of Language Evolution

Extralinguistic

Events in the history of the people relevant to the development of the language:

structure of the society;

expansion over new geographical areas;

migrations;

mixtures and separation of tribes;

political and economic unity or disunity;

contacts with other nations;

the progress of culture and literature

Intra-linguistic

General factors or regularities

(operate in all languages as inherent properties of any language system)

Specific factors (operate in one language or in a group of related languages at a certain period of time )

Изображение слайда

18

Слайд 18: General factors or regularities

assimilative and simplifying phonetic changes

[kn] > [n] in know, knee

[t] was missed out in often, listen

Изображение слайда

19

Слайд 19: Specific factors

English belongs to the Germanic group of languages and shares man y Germanic trends of development with cognate languages.

The Common Germanic trends were transformed and modified in the history of English.

As a result English displayed a tendency towards a more analytical grammatical structure, but it has gone further than most other languages because of the combination of internal and external conditions and due to the interaction of changes at different linguistic levels.

Изображение слайда

In the 14 th c. the following words were pronounced as they are spelt, the Latin letters retaining their original sound values. Show the phonetic changes since the 14 th c.

e.g. ME nut [nut] > NE [n A t]

ME moon, fat, meet, rider, want, knee, turn, first, part, for, often

Изображение слайда

Point out the peculiarities in the following passage from Shakespeare’s SONNETS (17th c.):

It is my love that keeps mine eyes awake;

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat –

Bring me within the level of your frown.

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate!

Изображение слайда

22

Слайд 22: 1) A linguistic change is a synchronic fact (A. Sommerfelt)

2) Visible change is the tip of an iceberg. Every alteration that eventually establishes itself, had to exist formerly as a choice. This means that the seedbed for variation in time is simply the whole landscape of variation in space

(D. Bolinger)

Изображение слайда

23

Последний слайд презентации: THEORETICAL ASPECTS OF LANGUAGE HISTORY

3) The structure of language is nothing but the unstable balance between the needs of communication, which require more numerous and more specific units and man’s inertia, which favours less numerous, less specific and more frequently occuring units

(A. Martinet)

Изображение слайда

Introduction. The subject matter of lexicology

Plan

-

The

subject matter of lexicology. -

Lexicology

in its relations to grammar, phonology and stylistics.

/.

THE

SUBJECT MATTER OF LEXICOLOGY

Lexicology

(Gr.

Lexis

— «word»

and logos

—

«learning») is a branch of linguistics that studies the

vocabulary of a given language. Its subject matter

is words and their meaning, their etymology and structural

peculiarities, their stability and synonymic relations, their

stylistic value.

Lexicology

should be organically related to all branches of linguistics such as

phonetics, stylistics, grammar and history of the language.

Changes

of word meanings undergone by words in the course of language

development are described by semasiology.

The

semantic structure of words

is described in terms of lexico-semantic variation, distributional

value and synonymic differentiation. This part of the science of

language is the

basis of lexicology.

Lexicology

should also include information on compiling dictionaries.

This

is called lexicography.

The

general study of words and vocabulary, irrespective of the specific

features of any particular language, is known as general

lexicology. The

description of the characteristic peculiarities in the vocabulary of

a given language is the subject matter of special

lexicology. The

latter is based on the fundamental principles of general lexicology,

which forms a part of general science of language.

Language

is highly organized and systematic. The central interest in

vocabulary studies lies therefore in determining the properties of

words and different

sort of relationships existing between them in a language. The ways

in which the development of meaning is influenced by extralinguistic

reality deserve considerable attention as well. The notions rendered

in word-meanings are, in fact, generalized reflections of things and

phenomena of

the outside world, the connection of words with the elements of

objective reality and their relevance to the mental and cultural

development of human

society. Things that are connected in reality come to be naturally

connected in language too. The study of language in our day has taken

on new

vitality and interest.

The

subject matter of

historical lexicology is

the evolution of the vocabulary. Dealing with changes that occur in

time this part of linguistics treats of origin of words and their

development, investigates the linguistic and extralinguistic forces

modifying the structure of words, their meaning and usage. Historical

lexicology must survey the vocabulary as a system in its evolution,

describing its change and development in the course of time.

The

study of the vocabulary in its synchronic aspect, i.e. at a given

stage of its development (in its modern state), is the subject matter

of descriptive

lexicology.

As

any science, lexicology directs upon its subject matter a close

scrutiny attempting to produce careful objective descriptions of

linguistic facts and refine the results of its observations.

All

the words in a language make up what is generally called the

vocabulary of the language.

The

volume and the character of the vocabulary are determined by the

social-economic and cultural history of the people speaking the

language. Social, political and cultural changes in human society

cause changes in the vocabulary of the language. The vocabulary grows

and changes together with

the development of human society. Language as a whole in all its

aspects, its words and idioms, its peculiarities of constitution, its

pronunciation, and the very tones of voice, language in its

completeness, is the most perfect mirror of the manners of the age.

Words are the necessary tools with which we convey thoughts and

feelings. When a new product, a new conception comes into the thought

of a people, it inevitably

finds a name in their language. A vocabulary is a kind of mirror,

reflecting the character, the mentality and the activity of the

people who use it; it is most sensible to changes and never remains

stable. Like all other forms of life, living languages are in a

constant state of evolution.

The

rapid advances which are being made in scientific knowledge, the

extension of sciences and arts to many new purposes and objects

create a continual demand for the formation of new words to express

new ideas, new agencies and new wants.

The

history of a community must be reflected in changes of the

vocabulary; as objects and ideas are forgotten, the corresponding

words or phrases

must be out of use, and as new knowledge is gained linguistic forms

to match it appear.

A

major interest is presented by linguistic relationships of lexical

units within the vocabulary. Distinction must be made at this point

between syntagmatic

and

paradigmatic

relations;

the former are based on the linear character of speech and are

studied by means of contextual, transformational

and other types of analysis, the latter reveal themselves in the

morphemic structure of words and are described in terms of morphemes

and their arrangement.

In

paradigmatic relationships we naturally distinguish:

(a)

the interdependence of elements within words,

(b)

the interdependence of words within

the vocabulary,

(c)

the influence of other aspects of the same language.

2.

LEXICOLOGY IN ITS RELATION TO GRAMMAR, PHONOLOGY AND STYLISTICS

As

a branch of linguistics lexicology has its own aims and methods of

scientific research; its main task is the study of the vocabulary of

a given language.

It must be borne in mind that the language system is so complex that

when we come to consider the best way in which one should arrange

linguistic

facts we are always confronted with the problem of the proper

distinction between all levels of linguistic organization.

The

affinities between these levels will always remind us that one level

of linguistic structure cannot well be treated in isolation from each

other.

No

part of a language can be adequately described without reference to

all other parts.

Internal

relations of elements within complex wholes are of the essence of

language with its many interdependent structures and systems at all

levels, the functions of every linguistic element and abstraction

being dependent on its relative place therein. This is, in fact, one

of the fundamental features of language and of the treatment of

language in modern linguistics.

Syntagmatic

and paradigmatic relations are nearly as important in vocabulary

studies as they are at the levels of grammar and phonology.

Different

ways of word-making, for instance, give sufficient evidence to say

that word-making can be assigned equally well to the provinces of

lexis

and grammar. The categories and types of word-formation, which

characterize the present-day English linguistic system, are largely

dependent upon

its grammatical structure.

Take

such examples as nouns used in the plural in a special sense:

ach’ice

=

counsel,

advices =

information

colour

=

tint,

colours — 1)

plural of tint, 2) flag

custom

=

habit,

customs= 1)

plural of habit, 2) duties

spectacle

= sight, spectacles = 1)

plural of sight, 2) eyeglasses

damage

= injury, damages =

compensation for injury

Sometimes,

when two kinds of pluralization, have produced two plurals of a word,

different uses and meanings have resulted, and as a consequence

the older form has not been ousted by the -s

form.

This can be seen in such pairs as:

brother-

brethren, brothers

cloth-cloths,

clothes

cow-kine,

cows

fish-fish,

fishes

die-

dice, dies

penny-pence,

pennies

No

right line of demarcation can be drawn between grammatical and

lexical meanings.

Some

concrete nouns may be used both as mass-nouns and as thing-nouns.

In

the latter meaning they may form s-plural;

fruit is used in the singular,

the plural fruits

is

used only when meaning «different kinds of fruit», the

plural form may also be used figuratively, as in fruits

of labour; fish is

generally used in the singular, the plural

fishes means

«different kinds of fish».

We

should distinguish grammar and vocabulary in terms of different kind

of generality.

Some

linguistic facts on the lexical level are no less general than those

in grammar, word-making, in particular. And with this comes the

realization

that there is a system in vocabulary, and lexicology must reasonably

treat not only of specific but also of general facts.

The

interrelation between vocabulary

and

grammar

is

not less characteristic in making new words through conversion, which

has existed at all stages

of the language and has flourished most in Modern English. A

converted word

develops

a meaning of its own and diverges so far from its original

function that it is felt to be an independent word, a homonym.

The

constant reciprocal action of vocabulary and

grammar

will be exemplified by different processes of compounding, most

productive in various languages, English including.

Contextual

restrictions of word-meanings deserve special attention.

A

single unambiguous word meaning is not always automatically assured.

Compare the following;

-

to

smoke a cigarette; -

to

smoke fish, meat, etc

(=

to care meat, fish, etc.).

-

The

table is round (table =

an article of furniture); -

The

fruit was unfit for table (table =

meal); -

The

table of contents (table +

a condensed tabulated statement, a schedule).Examples

like these may be given in numbers.

Mention

must be made at this point about the language basis for ambiguities

and their resolution. There are different types of ambiguity. The

first and

most familiar is a matter of vocabulary. Many words, including almost

all the common ones, are known to have two or more distinct meanings.

The combinations taking any of the available meanings for each word

in a sentence may be extremely numerous.

In

the resolution of vocabulary ambiguities one factor primary in

importance is grammatical structure. And this must always be taken

account of in the study of language or of any single system within

language.

The

meaning of the word is very often signalled by the «grammatical»

context in which it occurs.

Compare

the variant lexical meanings of the verb take

in

the following sentences:

She

took a book from the table.

She

took to thinking.

She

took me to be asleep.

He

took to the life of travelling.

You

were late, 1 take it (/

take

it =

I suppose).

The

verb to

mean + infinitive

means “to

intend»,

to

mean + gerund

means «to signify», «to have as a consequence»,

«to result in something». Compare

the following:

-

He

had never really meant to write that letter —

He

had never intended to write that letter. -

This

means changing all my plans —

This

resulted in changing all my plans.

To

remember+gerund

refers to the past and means «not to need to be reminded»,

to

remember +

infinitive refers to the future and means «not to omit

to do something».

The

construction verb + gerund can also be compared with one consisting

of verb + adverbial infinitive, e.g.:

-

The

horse stopped to drink; -

The

horse stopped drinking.

Further

examples of the so-called «grammatical» context, which

operates to convey the necessary meaning, will be found in cases

when, for instance, the passive form of the verb gives a clue

concerning its particular lexical meaning. For example, the verb to

succeed, as

registered in dictionaries,

can mean:

-

слідувати

за чимось, кимсь, бути наступником,

змінювати; -

мати

успіх, досягати успіху, досягати мети,

удаватись.

As

is known, the passive form of this verb excludes the secondary range

of its meaning.

That

lexicology should be viewed in relation to other parts of linguistic

learning, such as phonetics and style, is also quite obvious.

The

phonetic

interpretation of

the linguistic material is of undoubted interest in modern language

learning.

This

dimension in phonetic analysis appears when sounds that have a

recognized status when considered as individual segments are strung

together

in a sustained flow of talk. When a single phoneme, for instance, is

examined in relation to a total constellation of sounds in which it

may appear, the factors of pitch, loudness, rhythm, duration and

juncture are at once observed. These five factors are also phonemes.

In phonemic terms, they are called prosodic

or

suprasegmental

(in

contrast to segmental phonemes). All these are of primary importance

in talk as it appears in action.

The

meaning of a word may sometimes rely on the situation of the accent

expressed mainly in terms of pitch (where there are no associated

changes

of quality), e.g.:

rebel

[‘

rebl] (n) — [ri ‘ bel] (v)

Further

examples are such words as: anyone,

anything, anybody following

a negative which may have a different meaning according to their

pitch

pattern, e.g.:

/

‘can

t ‘eat anything -1 can eat nothing.

I

‘can’t eat anything -1 can eat some things.

Even

more subtle distinctions fairly common in English, can be observed in

such cases, as for instance, green

house and greenhouse, big black snake and

big

blacksnake, blue bottle and

bluebottle.

In

each of these pairs there is a difference in meaning and it is

indicated not by individual phonemes but by overall pattern

they produce. The same phenomenon may be observed in other

structures.

In

cases when the lexical meaning of the words admits either

interpretation without lexico-grammatical incongruity, ambiguity is

presented in actual speech by contrast in intonation patterns. Thus,

for instance, a

dancing girl with

rise in pitch and primary stress both on the head-word girl

marks

dancing

as

a present participle: a

girl performing the act of dancing.

But a

dancing girl,

with primary stress and rise in pitch both on the head-word

and the modifier dancing,

identifies

dancing

as

a verbal noun and signals the meaning a

dancer – танцівниця.

That

there is a close relationship between lexicology

and

stylistics

is

also obvious.

Stylistics

treats

of selection among the linguistic forms described by grammar and

lexicology. For its great part it treats of the artistic modification

of

speech for the sake of securing a particular effect of emotional

colouring in pictorial language.

The

study of the vocabulary leads us to the observation that many words

suggest more that they literally mean, and sometimes words which have

the same literal or actual meaning (denotation) differ widely in

their suggested meaning (connotation). Some words are more general,

colourless and neutral

in tone. But other words have a distinctly literary or poetic

flavour, or suggestion, which may be colloquial (informal), formal,

humorous, vulgar,

slangy, childish, stilted, learned, technical and so on through the

various labels by which we may indicate the standing level of a word.

Multiformity

of synonymic forms of expression, and transpositions on the lexical

level, which we study in lexicology, are closely connected with the

stylistic

differentiation of a national language.

It

is obvious from what has been said above that it is quite impossible

to learn a foreign language on a lexical basis alone. Nevertheless

the knowledge

of lexicology provides us with a clear understanding of the laws of

vocabulary development and helps to master the language.

REVISION

MATERIAL

Suggested

Assignments on Lecture 1

-

Be

ready to discuss the subject matter of lexicology. -

Discuss

the statement that lexicology must be viewed in relation to other

aspects of language learning. -

Give

illustrative examples to show that the lexical meaning of the word

is very often signalled by the “grammatical” context in which it

occurs. -

Give

examples to show that the phonetic interpretation of the linguistic

units is of undoubted interest in vocabulary studies. -

Be

ready to discuss the relationship between lexicology and stylistics. -

Give

comment on the diachronic and synchronic approach in vocabulary

studies. -

Comment

on the fundamental principles of structural linguistics. -

Be

ready to discuss the basic concepts of the descriptive theory. -

Give

a few examples of contrastive, non-contrastive and complementary

distribution. -

How

can we illustrate the influence of linguistic context on

word-meanings?

11.Comment

on the difference between syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations

between words.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The causes or moving factors in language history have always attracted the attention of linguists and have given rise to various explanations and theories. In the early 19th c, philologists of the romantic trend (J. G. Herder, J. and W. Grimm and others) interpreted the history of the Indo-European, and especially the Germanic languages, as decline and degradation, for most of these languages have been losing their richness of grammatical forms, declensions, conjugations and inflections since the so-called «Golden Age» of the parent-language. Linguists of the naturalist trend (e.g. A. Schleicher) conceived language as a living organism and associated stages in language history with stages of life: birth, youth, maturity, old age, and death. In the later 19th c. the psychological theories of language (W. Wundt, H. Paul) attributed linguistic changes to individual psychology and to accidental individual fluctuations. The study of factual history undertaken by the Young Grammarians led them to believe that there are no superior or inferior stages in language history and that all languages are equal; changes are brought about by phonetic laws which admit of no exceptions (seeming exceptions are due to analogy, which may introduce a historically unjustified form, or else to borrowing from another language). Sociologists in linguistics (J. Vendryes, A. Meillet) maintained that linguistic changes are caused by social conditions and events in external history.

Some modern authors assert that causality lies outside the scope of linguistics, which should be concerned only with the fact and mechanism of the change; others believe that linguistics should investigate only those causes and conditions of language evolution which are to be found within the language system; external factors are no concern of linguistic history. In accordance with this view the main internal cause which produces linguistic change is the pressure of the language system. Whenever the balance of the system or its symmetrical structural arrangement is disrupted, it tends to be restored again under the pressure of symmetry inherent in the system.

The recent decades witnessed a revival of interest in extralinguistic aspects of language history. The Prague school of linguists was the first among the modern trends to recognise the functional stratification of language and its diversity dependent on external conditions. In present-day theories, especially in the sociolinguistic trends, great importance is attached to the variability of speech in social groups as the primary factor of linguistic change.

Like any movement in nature and society, the evolution of language is caused by the struggle of opposites. The moving power underlying the development of language is made up of two main forces: one force is the growing and changing needs of man in the speech community; the other is the resisting force that curbs the changes and preserves the language in a state fit for communication. The two forces are manifestations of the two principal functions of language – its expressive and communicative functions. The struggle of the two opposites can also be described as the opposition of thought and means of its expression or the opposition of growing needs of expression and communication and the available resources of language.

These general forces operate in all languages at all times; they are so universal that they fail to account for concrete facts in the history of a particular language. To explain these facts many other conditioning factors must be taken into consideration.

The most widely accepted classification of factors relevant to language history divides them into external or extralinguistic and internal (also intra-linguistic and systemic).

Strictly speaking, the term «extra-linguistic» embraces a variety of conditions bearing upon different aspects of human life, for instance, the psychological or the physiological aspects. In the first place, however, extralinguistic factors include events in the history of the people relevant to the development of the language, such as the structure of society, expansion over new geographical areas, migrations, mixtures and separation of tribes, political and economic unity or disunity, contacts with other peoples, the progress of culture and literature. These aspects of external history determine the linguistic situation and affect the evolution of the language.

Internal factors of language evolution arise from the language system. They can be subdivided into general factors or general regularities, which operate in all languages as inherent properties of any language system, and specific factors operating in one language or in a group of related languages at a certain period of time.

The most general causes of language evolution are to be found in the tendencies to improve the language technique or its formal apparatus. These tendencies are displayed in numerous assimilative and simplifying phonetic changes in the history y of English (e.g. the consonant cluster [kn] in know and knee was simplified to [n]; [t] was missed out in often and listen, etc.) To this group we can also refer the tendency to express different meanings by distinct formal means and thus avoid what is known as «homonymy clashes».

On the other hand, similar or identical meanings tend to be indicated by identical means, therefore the plural ending of nouns -(e)s has gradually spread to most English nouns and replaced numerous markers of the plural.

Another group of general internal tendencies aims to preserve the language as a vehicle fit for communication. These tendencies resist linguistic change and account for the historical stability of many elements and features («statics in diachrony»). For instance, since the earliest periods English has retained many words and formal markers expressing the most important notions and distinctions, e.g. the words he, we, man, good, son; the suffix -d- to form the Past tense. This tendency also accounts for the growth of compensatory means to make up for the loss of essential distinctions, e.g. the wider use of prepositional phrases instead of case forms.

Among the general causes of language evolution, or rather among its universal regularities, we must mention the interdependence of changes within the sub-systems of the language and the interaction of changes at different linguistic levels.

Interdependence of changes at different linguistic levels can be illustrated by the history of noun morphology in English. In the course of history nouns have lost most of their cases (in OE there were four cases, nowadays – only two). The simplification of noun morphology involved changes at different levels: phonetic weakening of final syllables, analogical levelling of forms at the morphological level, and stabilisation of the word order at the level of syntax.

Some factors and causes of language evolution are confined to a certain group of languages or to one language only and may operate over a limited span of time. These specific factors are trends of evolution characteristic of separate languages or linguistic groups, which distinguish them from other languages. Since English belongs to the Germanic group of languages, it shares many Germanic trends of development with cognate languages. These trends were caused by common Germanic factors but were transformed and modified in the history of English, and were combined with other trends caused by specifically English internal and external factors. The combination of all these factors and the resulting course of evolution is unique for every language; it accounts for its individual history which is never repeated by other languages. Thus English, like other Germanic languages, displayed a tendency towards a more analytical grammatical structure, but it has gone further along this way of development than most other languages, probably owing to the peculiar combination of internal and external conditions and to the interaction of changes at different linguistic levels.

In conclusion it must be admitted that motivation of changes is one of the most difficult problems of the historical linguistics. The causes of many developments are obscure or hypothetical. Therefore in discussing the causes of the most important events in the history of English, we shall have to mention various theories and interpretations.

|

Практические расчеты на срез и смятие При изучении темы обратите внимание на основные расчетные предпосылки и условности расчета… |

Функция спроса населения на данный товар Функция спроса населения на данный товар: Qd=7-Р. Функция предложения: Qs= -5+2Р,где… |

Аальтернативная стоимость. Кривая производственных возможностей В экономике Буридании есть 100 ед. труда с производительностью 4 м ткани или 2 кг мяса… |

Вычисление основной дактилоскопической формулы Вычислением основной дактоформулы обычно занимается следователь. Для этого все десять пальцев разбиваются на пять пар… |

![THEORETICAL ASPECTS OF LANGUAGE HISTORY e.g. OE ME NE to find - fundon [fundon] - founden [f H nden]- found (the Past tense pl of the Ind. Mood) - (Past pl of the Subj. and Part.II) - (the 3 forms](https://s0.slide-share.ru/s_slide/4d0872873e5345c9de4027fbb9bf37d8/bb8b928e-07b1-4a5f-ac04-1672aeeaf80a.jpeg)