Introduction

This is a tutorial about writing code in Excel spreadsheets using Visual Basic for Applications (VBA).

Excel is one of Microsoft’s most popular products. In 2016, the CEO of Microsoft said «Think about a world without Excel. That’s just impossible for me.” Well, maybe the world can’t think without Excel.

- In 1996, there were over 30 million users of Microsoft Excel (source).

- Today, there are an estimated 750 million users of Microsoft Excel. That’s a little more than the population of Europe and 25x more users than there were in 1996.

We’re one big happy family!

In this tutorial, you’ll learn about VBA and how to write code in an Excel spreadsheet using Visual Basic.

Prerequisites

You don’t need any prior programming experience to understand this tutorial. However, you will need:

- Basic to intermediate familiarity with Microsoft Excel

- If you want to follow along with the VBA examples in this article, you will need access to Microsoft Excel, preferably the latest version (2019) but Excel 2016 and Excel 2013 will work just fine.

- A willingness to try new things

Learning Objectives

Over the course of this article, you will learn:

- What VBA is

- Why you would use VBA

- How to get set up in Excel to write VBA

- How to solve some real-world problems with VBA

Important Concepts

Here are some important concepts that you should be familiar with to fully understand this tutorial.

Objects: Excel is object-oriented, which means everything is an object — the Excel window, the workbook, a sheet, a chart, a cell. VBA allows users to manipulate and perform actions with objects in Excel.

If you don’t have any experience with object-oriented programming and this is a brand new concept, take a second to let that sink in!

Procedures: a procedure is a chunk of VBA code, written in the Visual Basic Editor, that accomplishes a task. Sometimes, this is also referred to as a macro (more on macros below). There are two types of procedures:

- Subroutines: a group of VBA statements that performs one or more actions

- Functions: a group of VBA statements that performs one or more actions and returns one or more values

Note: you can have functions operating inside of subroutines. You’ll see later.

Macros: If you’ve spent any time learning more advanced Excel functionality, you’ve probably encountered the concept of a “macro.” Excel users can record macros, consisting of user commands/keystrokes/clicks, and play them back at lightning speed to accomplish repetitive tasks. Recorded macros generate VBA code, which you can then examine. It’s actually quite fun to record a simple macro and then look at the VBA code.

Please keep in mind that sometimes it may be easier and faster to record a macro rather than hand-code a VBA procedure.

For example, maybe you work in project management. Once a week, you have to turn a raw exported report from your project management system into a beautifully formatted, clean report for leadership. You need to format the names of the over-budget projects in bold red text. You could record the formatting changes as a macro and run that whenever you need to make the change.

What is VBA?

Visual Basic for Applications is a programming language developed by Microsoft. Each software program in the Microsoft Office suite is bundled with the VBA language at no extra cost. VBA allows Microsoft Office users to create small programs that operate within Microsoft Office software programs.

Think of VBA like a pizza oven within a restaurant. Excel is the restaurant. The kitchen comes with standard commercial appliances, like large refrigerators, stoves, and regular ole’ ovens — those are all of Excel’s standard features.

But what if you want to make wood-fired pizza? Can’t do that in a standard commercial baking oven. VBA is the pizza oven.

Yum.

Why use VBA in Excel?

Because wood-fired pizza is the best!

But seriously.

A lot of people spend a lot of time in Excel as a part of their jobs. Time in Excel moves differently, too. Depending on the circumstances, 10 minutes in Excel can feel like eternity if you’re not able to do what you need, or 10 hours can go by very quickly if everything is going great. Which is when you should ask yourself, why on earth am I spending 10 hours in Excel?

Sometimes, those days are inevitable. But if you’re spending 8-10 hours everyday in Excel doing repetitive tasks, repeating a lot of the same processes, trying to clean up after other users of the file, or even updating other files after changes are made to the Excel file, a VBA procedure just might be the solution for you.

You should consider using VBA if you need to:

- Automate repetitive tasks

- Create easy ways for users to interact with your spreadsheets

- Manipulate large amounts of data

Getting Set Up to Write VBA in Excel

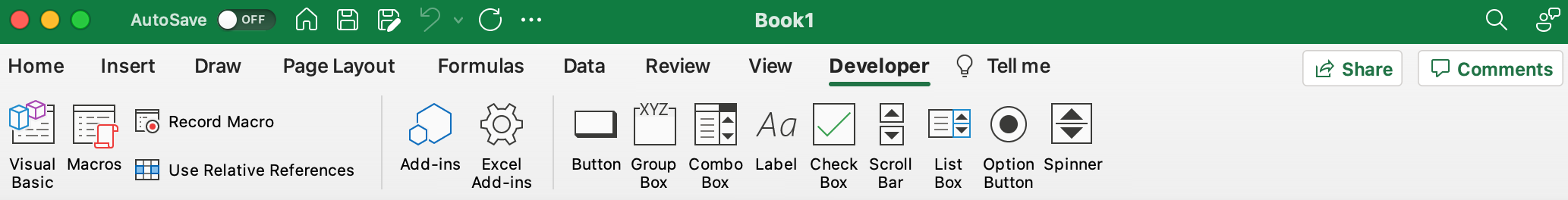

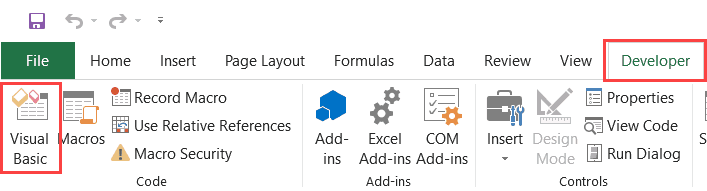

Developer Tab

To write VBA, you’ll need to add the Developer tab to the ribbon, so you’ll see the ribbon like this.

To add the Developer tab to the ribbon:

- On the File tab, go to Options > Customize Ribbon.

- Under Customize the Ribbon and under Main Tabs, select the Developer check box.

After you show the tab, the Developer tab stays visible, unless you clear the check box or have to reinstall Excel. For more information, see Microsoft help documentation.

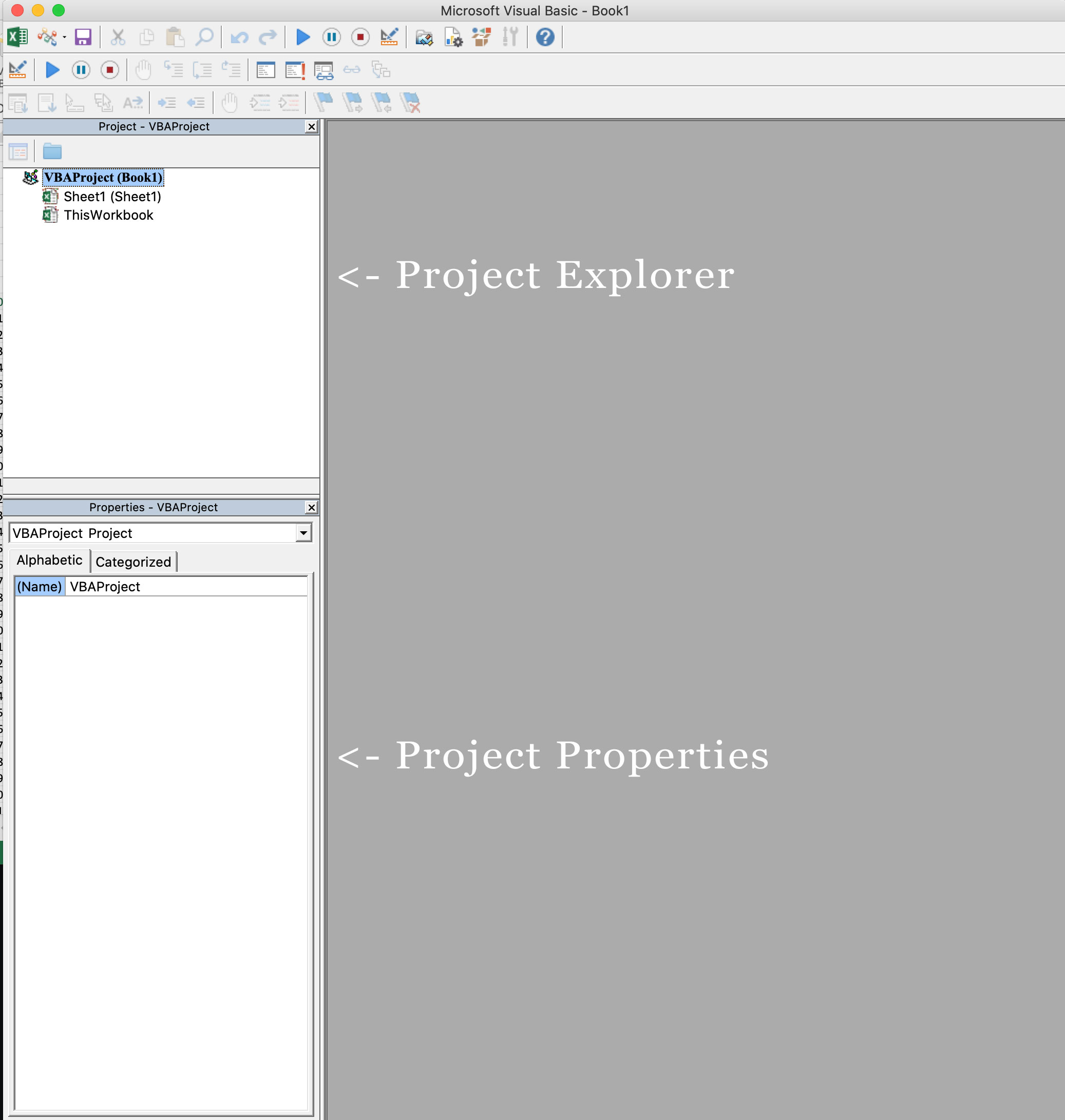

VBA Editor

Navigate to the Developer Tab, and click the Visual Basic button. A new window will pop up — this is the Visual Basic Editor. For the purposes of this tutorial, you just need to be familiar with the Project Explorer pane and the Property Properties pane.

Excel VBA Examples

First, let’s create a file for us to play around in.

- Open a new Excel file

- Save it as a macro-enabled workbook (. xlsm)

- Select the Developer tab

- Open the VBA Editor

Let’s rock and roll with some easy examples to get you writing code in a spreadsheet using Visual Basic.

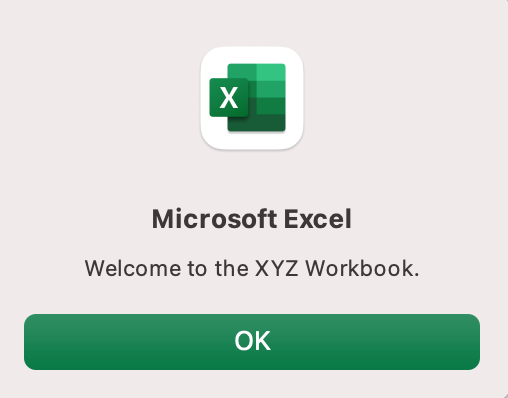

Example #1: Display a Message when Users Open the Excel Workbook

In the VBA Editor, select Insert -> New Module

Write this code in the Module window (don’t paste!):

Sub Auto_Open()

MsgBox («Welcome to the XYZ Workbook.»)

End Sub

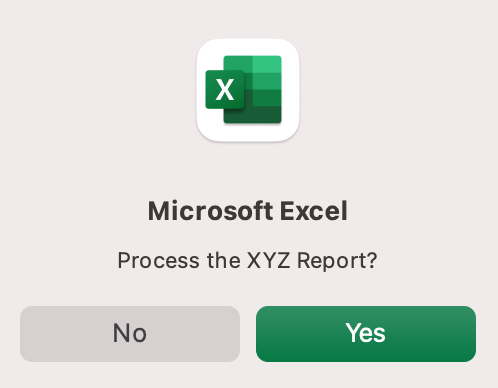

Save, close the workbook, and reopen the workbook. This dialog should display.

Ta da!

How is it doing that?

Depending on your familiarity with programming, you may have some guesses. It’s not particularly complex, but there’s quite a lot going on:

- Sub (short for “Subroutine): remember from the beginning, “a group of VBA statements that performs one or more actions.”

- Auto_Open: this is the specific subroutine. It automatically runs your code when the Excel file opens — this is the event that triggers the procedure. Auto_Open will only run when the workbook is opened manually; it will not run if the workbook is opened via code from another workbook (Workbook_Open will do that, learn more about the difference between the two).

- By default, a subroutine’s access is public. This means any other module can use this subroutine. All examples in this tutorial will be public subroutines. If needed, you can declare subroutines as private. This may be needed in some situations. Learn more about subroutine access modifiers.

- msgBox: this is a function — a group of VBA statements that performs one or more actions and returns a value. The returned value is the message “Welcome to the XYZ Workbook.”

In short, this is a simple subroutine that contains a function.

When could I use this?

Maybe you have a very important file that is accessed infrequently (say, once a quarter), but automatically updated daily by another VBA procedure. When it is accessed, it’s by many people in multiple departments, all across the company.

- Problem: Most of the time when users access the file, they are confused about the purpose of this file (why it exists), how it is updated so often, who maintains it, and how they should interact with it. New hires always have tons of questions, and you have to field these questions over and over and over again.

- Solution: create a user message that contains a concise answer to each of these frequently answered questions.

Real World Examples

- Use the MsgBox function to display a message when there is any event: user closes an Excel workbook, user prints, a new sheet is added to the workbook, etc.

- Use the MsgBox function to display a message when a user needs to fulfill a condition before closing an Excel workbook

- Use the InputBox function to get information from the user

Example #2: Allow User to Execute another Procedure

In the VBA Editor, select Insert -> New Module

Write this code in the Module window (don’t paste!):

Sub UserReportQuery()

Dim UserInput As Long

Dim Answer As Integer

UserInput = vbYesNo

Answer = MsgBox(«Process the XYZ Report?», UserInput)

If Answer = vbYes Then ProcessReport

End Sub

Sub ProcessReport()

MsgBox («Thanks for processing the XYZ Report.»)

End Sub

Save and navigate back to the Developer tab of Excel and select the “Button” option. Click on a cell and assign the UserReportQuery macro to the button.

Now click the button. This message should display:

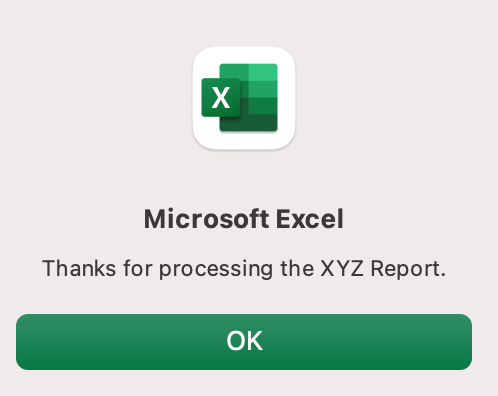

Click “yes” or hit Enter.

Once again, tada!

Please note that the secondary subroutine, ProcessReport, could be anything. I’ll demonstrate more possibilities in example #3. But first…

How is it doing that?

This example builds on the previous example and has quite a few new elements. Let’s go over the new stuff:

- Dim UserInput As Long: Dim is short for “dimension” and allows you to declare variable names. In this case, UserInput is the variable name and Long is the data type. In plain English, this line means “Here’s a variable called “UserInput”, and it’s a Long variable type.”

- Dim Answer As Integer: declares another variable called “Answer,” with a data type of Integer. Learn more about data types here.

- UserInput = vbYesNo: assigns a value to the variable. In this case, vbYesNo, which displays Yes and No buttons. There are many button types, learn more here.

- Answer = MsgBox(“Process the XYZ Report?”, UserInput): assigns the value of the variable Answer to be a MsgBox function and the UserInput variable. Yes, a variable within a variable.

- If Answer = vbYes Then ProcessReport: this is an “If statement,” a conditional statement, which allows us to say if x is true, then do y. In this case, if the user has selected “Yes,” then execute the ProcessReport subroutine.

When could I use this?

This could be used in many, many ways. The value and versatility of this functionality is more so defined by what the secondary subroutine does.

For example, maybe you have a file that is used to generate 3 different weekly reports. These reports are formatted in dramatically different ways.

- Problem: Each time one of these reports needs to be generated, a user opens the file and changes formatting and charts; so on and so forth. This file is being edited extensively at least 3 times per week, and it takes at least 30 minutes each time it’s edited.

- Solution: create 1 button per report type, which automatically reformats the necessary components of the reports and generates the necessary charts.

Real World Examples

- Create a dialog box for user to automatically populate certain information across multiple sheets

- Use the InputBox function to get information from the user, which is then populated across multiple sheets

Example #3: Add Numbers to a Range with a For-Next Loop

For loops are very useful if you need to perform repetitive tasks on a specific range of values — arrays or cell ranges. In plain English, a loop says “for each x, do y.”

In the VBA Editor, select Insert -> New Module

Write this code in the Module window (don’t paste!):

Sub LoopExample()

Dim X As Integer

For X = 1 To 100

Range(«A» & X).Value = X

Next X

End Sub

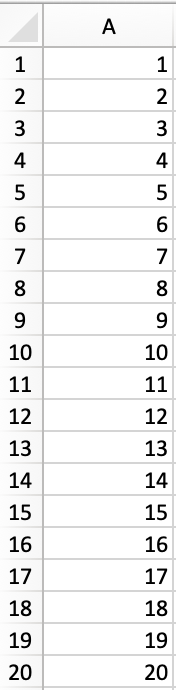

Save and navigate back to the Developer tab of Excel and select the Macros button. Run the LoopExample macro.

This should happen:

Etc, until the 100th row.

How is it doing that?

- Dim X As Integer: declares the variable X as a data type of Integer.

- For X = 1 To 100: this is the start of the For loop. Simply put, it tells the loop to keep repeating until X = 100. X is the counter. The loop will keep executing until X = 100, execute one last time, and then stop.

- Range(«A» & X).Value = X: this declares the range of the loop and what to put in that range. Since X = 1 initially, the first cell will be A1, at which point the loop will put X into that cell.

- Next X: this tells the loop to run again

When could I use this?

The For-Next loop is one of the most powerful functionalities of VBA; there are numerous potential use cases. This is a more complex example that would require multiple layers of logic, but it communicates the world of possibilities in For-Next loops.

Maybe you have a list of all products sold at your bakery in Column A, the type of product in Column B (cakes, donuts, or muffins), the cost of ingredients in Column C, and the market average cost of each product type in another sheet.

You need to figure out what should be the retail price of each product. You’re thinking it should be the cost of ingredients plus 20%, but also 1.2% under market average if possible. A For-Next loop would allow you to do this type of calculation.

Real World Examples

- Use a loop with a nested if statement to add specific values to a separate array only if they meet certain conditions

- Perform mathematical calculations on each value in a range, e.g. calculate additional charges and add them to the value

- Loop through each character in a string and extract all numbers

- Randomly select a number of values from an array

Conclusion

Now that we’ve talked about pizza and muffins and oh-yeah, how to write VBA code in Excel spreadsheets, let’s do a learning check. See if you can answer these questions.

- What is VBA?

- How do I get set up to start using VBA in Excel?

- Why and when would you use VBA?

- What are some problems I could solve with VBA?

If you have a fair idea of how to you could answer these questions, then this was successful.

Whether you’re an occasional user or a power user, I hope this tutorial provided useful information about what can be accomplished with just a bit of code in your Excel spreadsheets.

Happy coding!

Learning Resources

- Excel VBA Programming for Dummies, John Walkenbach

- Get Started with VBA, Microsoft Documentation

- Learning VBA in Excel, Lynda

A bit about me

I’m Chloe Tucker, an artist and developer in Portland, Oregon. As a former educator, I’m continuously searching for the intersection of learning and teaching, or technology and art. Reach out to me on Twitter @_chloetucker and check out my website at chloe.dev.

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

The first step to working with VBA in Excel is to get yourself familiarized with the Visual Basic Editor (also called the VBA Editor or VB Editor).

In this tutorial, I will cover all there is to know about the VBA Editor and some useful options that you should know when coding in Excel VBA.

What is Visual Basic Editor in Excel?

Visual Basic Editor is a separate application that is a part of Excel and opens whenever you open an Excel workbook. By default, it’s hidden and to access it, you need to activate it.

VB Editor is the place where you keep the VB code.

There are multiple ways you get the code in the VB Editor:

- When you record a macro, it automatically creates a new module in the VB Editor and inserts the code in that module.

- You can manually type VB code in the VB editor.

- You can copy a code from some other workbook or from the internet and paste it in the VB Editor.

Opening the VB Editor

There are various ways to open the Visual Basic Editor in Excel:

- Using a Keyboard Shortcut (easiest and fastest)

- Using the Developer Tab.

- Using the Worksheet Tabs.

Let’s go through each of these quickly.

Keyboard Shortcut to Open the Visual Basic Editor

The easiest way to open the Visual Basic editor is to use the keyboard shortcut – ALT + F11 (hold the ALT key and press the F11 key).

As soon as you do this, it will open a separate window for the Visual Basic editor.

This shortcut works as a toggle, so when you use it again, it will take you back to the Excel application (without closing the VB Editor).

The shortcut for the Mac version is Opt + F11 or Fn + Opt + F11

Using the Developer Tab

To open the Visual Basic Editor from the ribbon:

- Click the Developer tab (if you don’t see a developer tab, read this on how to get it).

- In the Code group, click on Visual Basic.

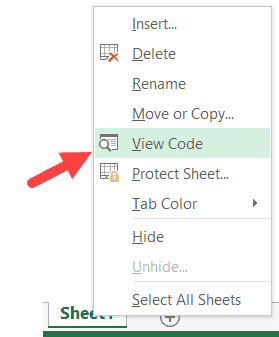

Using the Worksheet Tab

This is a less used method to open the Vb Editor.

Go to any of the worksheet tabs, right-click, and select ‘View Code’.

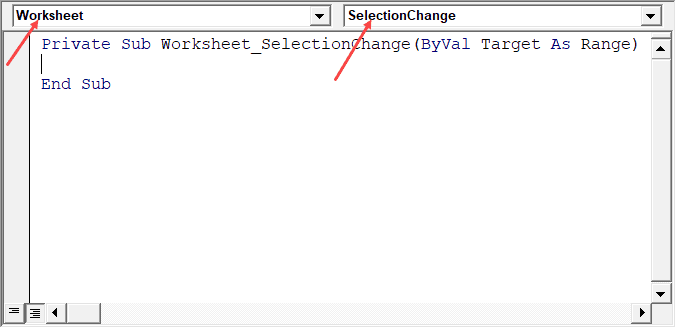

This method wouldn’t just open the VB Editor, it will also take you to the code window for that worksheet object.

This is useful when you want to write code that works only for a specific worksheet. This is usually the case with worksheet events.

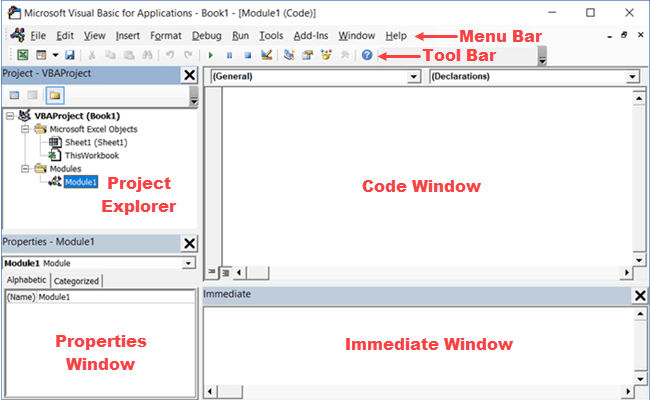

Anatomy of the Visual Basic Editor in Excel

When you open the VB Editor for the first time, it may look a bit overwhelming.

There are different options and sections that may seem completely new at first.

Also, it still has an old Excel 97 days look. While Excel has improved tremendously in design and usability over the years, the VB Editor has not seen any change in the way it looks.

In this section, I will take you through the different parts of the Visual Basic Editor application.

Note: When I started using VBA years ago, I was quite overwhelmed with all these new options and windows. But as you get used to working with VBA, you would get comfortable with most of these. And most of the time, you’ll not be required to use all the options, only a hand full.

Below is an image of the different components of the VB Editor. These are then described in detail in the below sections of this tutorial.

Now let’s quickly go through each of these components and understand what it does:

Menu Bar

This is where you have all the options that you can use in the VB Editor. It is similar to the Excel ribbon where you have tabs and options with each tab.

You can explore the available options by clicking on each of the menu element.

You will notice that most of the options in VB Editor have keyboard shortcuts mentioned next to it. Once you get used to a few keyboard shortcuts, working with the VB Editor becomes really easy.

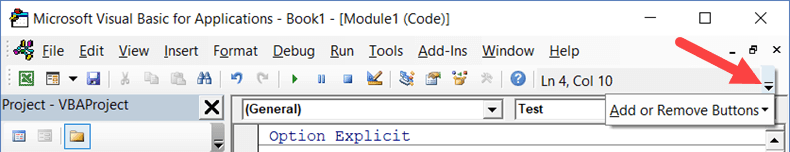

Tool Bar

By default, there is a toolbar in the VB Editor which has some useful options that you’re likely to need most often. This is just like the Quick Access Toolbar in Excel. It gives you quick access to some of the useful options.

You can customize it a little by removing or adding options to it (by clicking on the small downward pointing arrow at the end of the toolbar).

In most cases, the default toolbar is all you need when working with the VB Editor.

You can move the toolbar above the menu bar by clicking on the three gray dots (at the beginning of the toolbar) and dragging it above the menu bar.

Note: There are four toolbars in the VB Editor – Standard, Debug, Edit, and User form. What you see in the image above (which is also the default) is the standard toolbar. You can access other toolbars by going to the View option and hovering the cursor on the Toolbars option. You can add one or more toolbars to the VB Editor if you want.

Project Explorer

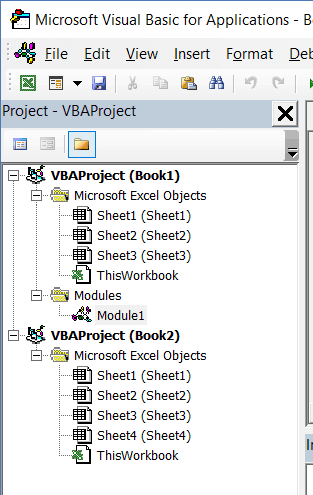

Project Explorer is a window on the left that shows all the objects currently open in Excel.

When you’re working with Excel, every workbook or add-in that is open is a project. And each of these projects can have a collection of objects in it.

For example, in the below image, the Project Explorer shows the two workbooks that are open (Book1 and Book2) and the objects in each workbook (worksheets, ThisWorkbook, and Module in Book1).

There is a plus icon to the left of objects that you can use to collapse the list of objects or expand and see the complete list of objects.

The following objects can be a part of the Project Explorer:

- All open Workbooks – within each workbook (which is also called a project), you can have the following objects:

- Worksheet object for each worksheet in the workbook

- ThisWorkbook object which represents the workbook itself

- Chartsheet object for each chart sheet (these are not as common as worksheets)

- Modules – This is where the code that is generated with a macro recorder goes. You can also write or copy-paste VBA code here.

- All open Add-ins

Consider the Project Explorer as a place that outlines all the objects open in Excel at the given time.

The keyboard shortcut to open the Project Explorer is Control + R (hold the control key and then press R). To close it, simply click the close icon at the top right of the Project Explorer window.

Note: For every object in Project Explorer, there is a code window in which you can write the code (or copy and paste it from somewhere). The code window appears when you double click on the object.

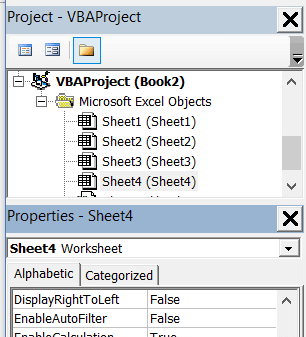

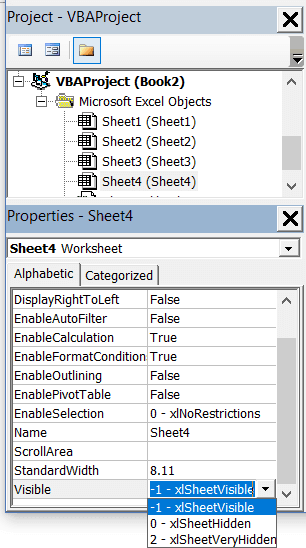

Properties Window

Properties window is where you get to see the properties of the select object. If you don’t have the Properties window already, you can get it by using the keyboard shortcut F4 (or go to the View tab and click Properties window).

Properties window is a floating window which you can dock in the VB Editor. In the below example, I have docked it just below the Project Explorer.

Properties window allows us to change the properties of a selected object. For example, if I want to make a worksheet hidden (or very hidden), I can do that by changing the Visible Property of the selected worksheet object.

Related: Hiding a Worksheet in Excel (that can not be un-hidden easily)

Code Window

There is a code window for each object that is listed in the Project Explorer. You can open the code window for an object by double-clicking on it in the Project Explorer area.

Code window is where you’ll write your code or copy paste a code from somewhere else.

When you record a macro, the code for it goes into the code window of a module. Excel automatically inserts a module to place the code in it when recording a macro.

Related: How to Run a Macro (VBA Code) in Excel.

Immediate Window

The Immediate window is mostly used when debugging code. One way I use the Immediate window is by using a Print.Debug statement within the code and then run the code.

It helps me to debug the code and determine where my code gets stuck. If I get the result of Print.Debug in the immediate window, I know the code worked at least till that line.

If you’re new to VBA coding, it may take you some time to be able to use the immediate window for debugging.

By default, the immediate window is not visible in the VB Editor. You can get it by using the keyboard shortcut Control + G (or can go to the View tab and click on ‘Immediate Window’).

Where to Add Code in the VB Editor

I hope you now have a basic understanding of what VB Editor is and what all parts it has.

In this section of this tutorial, I will show you where to add a VBA code in the Visual Basic Editor.

There are two places where you can add the VBA code in Excel:

- The code window for an object. These objects can be a workbook, worksheet, User Form, etc.

- The code window of a module.

Module Code Window Vs Object Code Window

Let me first quickly clear the difference between adding a code in a module vs adding a code in an object code window.

When you add a code to any of the objects, it’s dependent on some action of that object that will trigger that code. For example, if you want to unhide all the worksheets in a workbook as soon as you open that workbook, then the code would go in the ThisWorkbook object (which represents the workbook).

The trigger, in this case, is opening the workbook.

Similarly, if you want to protect a worksheet as soon as some other worksheet is activated, the code for that would go in the worksheet code window.

These triggers are called events and you can associate a code to be executed when an event occurs.

Related: Learn more about Events in VBA.

On the contrary, the code in the module needs to be executed either manually (or it can be called from other subroutines as well).

When you record a macro, Excel automatically creates a module and inserts the recorded macro code in it. Now if you have to run this code, you need to manually execute the macro.

Adding VBA Code in Module

While recording a macro automatically creates a module and inserts the code in it, there are some limitations when using a macro recorder. For example, it can not use loops or If Then Else conditions.

In such cases, it’s better to either copy and paste the code manually or write the code yourself.

A module can be used to hold the following types of VBA codes:

- Declarations: You can declare variables in a module. Declaring variables allows you to specify what type of data a variable can hold. You can declare a variable for a sub-routine only or for all sub-routines in the module (or all modules)

- Subroutines (Procedures): This is the code that has the steps you want VBA to perform.

- Function Procedures: This is a code that returns a single value and you can use it to create custom functions (also called User Defined Functions or UDFs in VBA)

By default, a module is not a part of the workbook. You need to insert it first before using it.

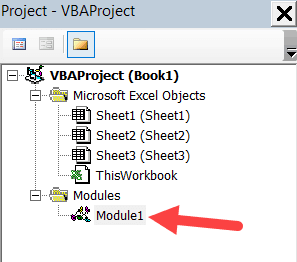

Adding a Module in the VB Editor

Below are the steps to add a module:

- Right-click on any object of the workbook (in which you want the module).

- Hover the cursor on the Insert option.

- Click on Module.

This would instantly create a folder called Module and insert an object called Module 1. If you already have a module inserted, the above steps would insert another module.

Once the module is inserted, you can double click on the module object in the Project Explorer and it will open the code window for it.

Now you can copy-paste the code or write it yourself.

Removing the Module

Below are the steps to remove a module in Excel VBA:

- Right-click on the module that you want to remove.

- Click on Remove Module option.

- In the dialog box that opens, click on No.

Note: You can export a module before removing it. It gets saved as a .bas file and you can import it in some other project. To export a module, right-click on the module and click on ‘Export file’.

Adding Code to the Object Code Window

To open the code window for an object, simply double-click on it.

When it opens, you can enter the code manually or copy-paste the code from other modules or from the internet.

Note that some of the objects allow you to choose the event for which you want to write the code.

For example, if you want to write a code for something to happen when selection is changed in the worksheet, you need to first select worksheets from the drop-down at the top left of the code window and then select the change event from the drop-down on the right.

Note: These events are specific to the object. When you open the code window for a workbook, you will see the events related to the workbook object. When you open the code window for a worksheet, you will see the events related to the worksheet object.

Customizing the VB Editor

While the default settings of the Visual Basic Editor are good enough for most users, it does allow you to further customize the interface and a few functionalities.

In this section of the tutorial, I will show you all the options you have when customizing the VB Editor.

To customize the VB Editor environment, click Tools in the menu bar and then click on Options.

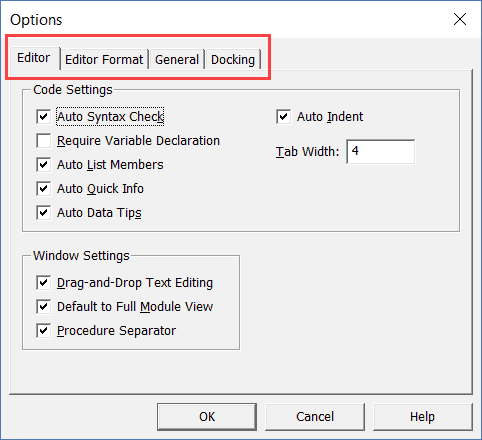

This would open the Options dialog box which will give you all the customization options in the VB Editor. The ‘Options’ dialog box has four tabs (as shown below) that have various customizations options for the Visual Basic Editor.

Let’s quickly go through each of these tabs and the important options in each.

Editor Tab

While the inbuilt settings work fine in most cases, let me still go through the options in this tab.

As you get more proficient working with VBA in Excel, you may want to customize the VB Editor using some of these options.

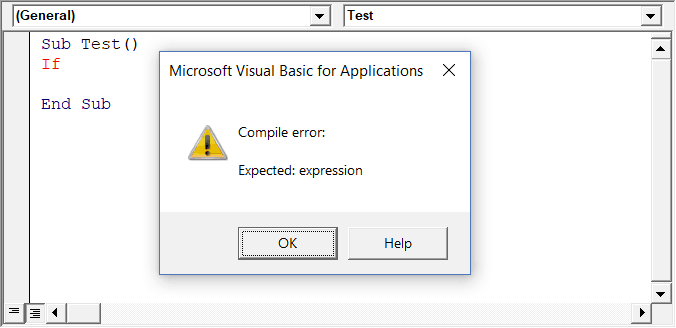

Auto Syntax Check

When working with VBA in Excel, as soon as you make a syntax error, you will be greeted by a pop-up dialog box (with some description about the error). Something as shown below:

If you disable this option, this pop-up box will not appear even when you make a syntax error. However, there would be a change in color in the code text to indicate that there is an error.

If you’re a beginner, I recommend you keep this option enabled. As you get more experienced with coding, you may start finding these pop-up boxes irritating, and then you can disable this option.

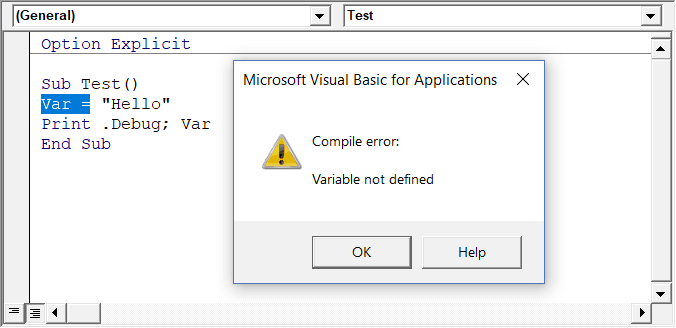

Require Variable Declaration

This is one option I recommend enabling.

When you’re working with VBA, you would be using variables to hold different data types and objects.

When you enable this option, it automatically inserts the ‘Option Explicit’ statement at the top of the code window. This forces you to declare all the variables that you’re using in your code. If you don’t declare a variable and try to execute the code, it will show an error (as shown below).

In the above case, I used the variable Var, but I didn’t declare it. So when I try to run the code, it shows an error.

This option is quite useful when you have a lot of variables. It often helps me find misspelled variables names as they are considered as undeclared and an error is shown.

Note: When you enable this option, it does not impact the existing modules.

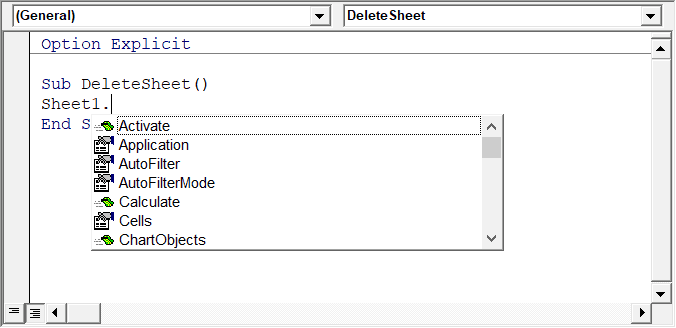

Auto List Member

This option is quite useful as it helps you get a list of properties of methods for an object.

For example, if I want to delete a worksheet (Sheet1), I need to use the line Sheet1.Delete.

While I am typing the code, as soon as I type the dot, it will show me all the methods and properties associated with the Worksheet object (as shown below).

Auto list feature is great as it allows you to:

- Quickly select the property and method from the list and saves time

- Shows you all the properties and methods which you may not be aware of

- Avoid making spelling errors

This option is enabled by default and I recommend keeping it that way.

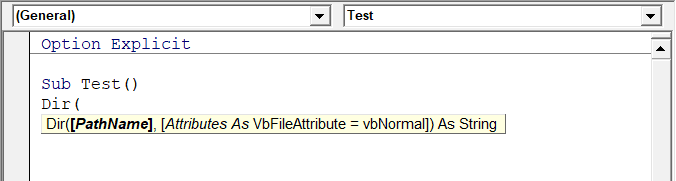

Auto Quick Info Options

When you type a function in Excel worksheet, it shows you some information about the function – such as the arguments it takes.

Similarly, when you type a function in VBA, it shows you some information (as shown below). But for that to happen, you need to make sure the Auto Quick Info option is enabled (which it is by default).

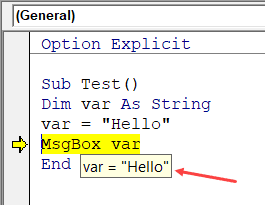

Auto Data Tips Options

When you’re going through your code line by line and place your cursor above a variable name, it will show you the value of the variable.

I find it quite useful when debugging the code or going through the code line by line which has loops in it.

In the above example, as soon as I put the cursor over the variable (var), it shows the value it holds.

This option is enabled by default and I recommend you keep it that way.

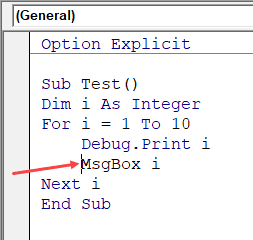

Auto Indent

Since VBA codes can get long and messy, using indentation increases the readability of the code.

When writing code, you can indent using the tab key.

This option ensures that when you are done with the indented line and hit enter, the next line doesn’t start from the very beginning, but has the same indentation as the previous line.

In the above example, after I write the Debug.Print line and hit enter, it will start right below it (with the same indentation level).

I find this option useful and turning this off would mean manually indenting each line in a block of code that I want indented.

You can change the indentation value if you want. I keep it at the default value.

Drag and Drop Text Editing

When this option is enabled, it allows you to select a block of code and drag and drop it.

It saves time as you don’t have to first cut and then paste it. You can simply select and drag it.

This option is enabled by default and I recommend you keep it that way.

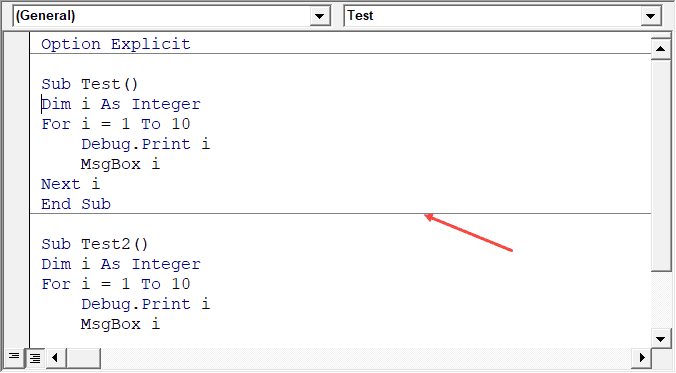

Default to Full Module View

When this option is enabled, you will be able to see all the procedures in a module in one single scrollable list.

If you disable this option, you will only be able to see one module at a time. You will have to make a selection of the module you want to see from the drop-down at the top right of the code window.

This option is enabled by default and I recommend keeping it that way.

One reason you may want to disable it when you have multiple procedures that are huge and scrolling across these is taking time, or when you have a lot of procedures and you want to quickly find it instead of wasting time in scrolling.

Procedure Separator

When this option is enabled, you will see a line (a kind of divider) between two procedures.

I find this useful as it visually shows when one procedure ends and the other one starts.

It’s enabled by default and I recommend keeping it that way.

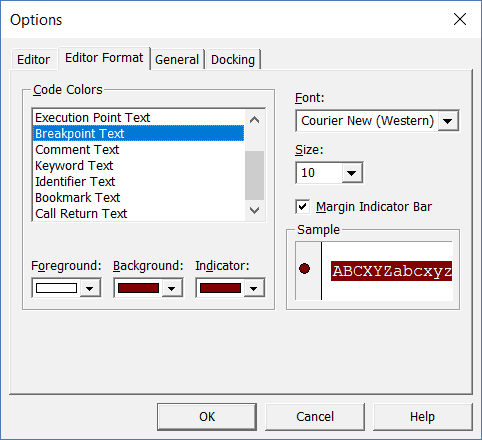

Editor Format Tab

With the options in the Editor Format tab, you can customize the way your code looks in the code window.

Personally, I keep all the default options as I am fine with it. If you want, you can tweak this based on your preference.

To make a change, you need to first select an option in the Code Colors box. Once an option is selected, you can modify the foreground, background, and indicator color for it.

The font type and font size can also be set in this tab. It’s recommended to use a fixed-width font such as Courier New, as it makes the code more readable.

Note that the font type and size setting will remain the same for all code types (i.e., all the code types shown in the code color box).

Below is an image where I have selected Breakpoint, and I can change the formatting of it.

Note: The Margin Indicator Bar option when enabled shows a little margin bar to the left of the code. It’s helpful as it shows useful indicators when executing the code. In the above example, when you set a breakpoint, it will automatically show a red dot to the left of the line in the margin bar. Alternatively, to set a breakpoint, you can simply click on the margin bar on the left of the code line that you want as the breakpoint.

By default, Margin Indicator Bar is enabled and I recommend keeping it that way.

One of my VBA course students found this customization options useful and she was color blind. Using the options here, she was able to set the color and formats that made it easy for her to work with VBA.

General Tab

The General tab has many options but you don’t need to change any of it.

I recommend you keep all the options as is.

One important option to know about in this tab is Error Handling.

By default, ‘Break on Unhandled Errors’ is selected and I recommend keeping it that way.

This option means that if your code encounters an error, and you have not handled that error in your code already, then it will break and stop. But if you have addressed the error (such as by using On Error Resume Next or On Error Goto options), then it will not break (as the errors are not unhandled).

Docking Tab

In this tab, you can specify which windows you want to get docked.

Docking means that you can fix the position of a window (such as project explorer or the Properties window) so that it doesn’t float around and you can view all the different windows at the same time.

If you don’t dock, you will be able to view one window at a time in full-screen mode and will have to switch to the other one.

I recommend keeping the default settings.

Other Excel tutorials you may like:

- How to Remove Macros From an Excel Workbook

- Comments in Excel VBA (Add, Remove, Block Commenting)

- Using Active Cell in VBA in Excel (Examples)

For some people, the answer will revolve around having to learn a new programming language and coding. However, if you’re anything like me, your answer will be the Visual Basic Editor (or VBE).

The first few times I opened the Visual Basic Editor I had no idea what I was looking at or what I was supposed to do. At the time, I really wished I had access to an Excel tutorial that explained the main features of the VBE comprehensively. Unfortunately, I didn’t find it.

Obviously, in the last few years I’ve come a long way. Nowadays, I have no problems using the Visual Basic Editor and feel quite comfortable working on it. However, sometimes I take a look around the Internet to see if I can find a good and comprehensive Excel tutorial about the VBE. The truth is that, as of the time of this writing, there are not that many online resources covering this in detail.

I find this a little bit surprising. After all, I’m sure about one thing:

Many people who are interested in learning macros and Visual Basic for Applications feel confused the first time they open the Visual Basic Editor. I know it because, as explained above, that happened to me. This is a pity because, in practice, you’re likely to constantly work with the VBE on your way to becoming a proficient VBA user.

The place where you’ll find those Code Windows is the Visual Basic Editor. Therefore, if you want to become an advanced macro and VBA user, you must understand how to use the VBE properly.

The importance of the Visual Basic Editor and the lack of resources covering the VBE in detail are the main reasons why I decided to write this Excel tutorial. In this post, I cover the following topics:

Enough with the introduction. Let’s get into the first topic of this Excel tutorial about the Visual Basic Editor.

The Visual Basic Editor is not exactly the same as Excel. It is actually a separate application, even though you’ll usually open it through Excel. In fact, in order for the VBE to be able to run, Excel must be open.

The main function of the VBE is to allow you to write and edit VBA code.

The Visual Basic Editor is sometimes referred to as the Integrated Development Environment (IDE). In this Excel tutorial, I use the first term (Visual Basic Editor or VBE) but don’t be confused if you see the second term being used in other places.

How To Open The Visual Basic Editor In Excel

You can open the VBE using either of the following methods:

- Click on “Visual Basic” in the Developer tab of the Ribbon.

- Use the keyboard shortcut “Alt + F11”.

How Does The Visual Basic Editor Look

The basic VBE window can be divided in the following 6 sections, all of which I explain below. In reality, there are more components than those which appear in this screenshot (such as the Locals and Watch Windows) but, since they’re more advanced, I’ll cover them in a future Excel tutorial.

The Visual Basic Editor:

- Has several windows.

- Is highly customizable.

As a consequence of the above, there is the possibility that your VBE window doesn’t look exactly as the screenshot above.

In fact, if this is the first time that you’re opening the Visual Basic Editor, you probably can’t see element #6 that appears in the lower part of the image above. The reason is that this particular window (known as the Immediate Window) is, by default, hidden. I explain how you can easily unhide it below.

As you get more familiar with the VBE, you’ll notice that you have a lot of flexibility regarding how the interface looks like. The Visual Basic Editor allows you to, for example:

- Hide or un-hide windows.

- Move or re-arrange windows.

- Dock windows.

Let’s dive right in and understand the 6 main components of the Visual Basic Editor.

Component #1: Menu Bar

If you’ve been using computers for a reasonable amount of time, you’re probably quite familiar with menu bars. If that’s the case, the VBE menu bar is not very different from the other menu bars you’ve seen before.

The menu bar, basically, contains several drop-down menus. Each of the drop-down menus contains commands that you can use to interact and do things with the different components of the Visual Basic Editor.

One thing you’ll notice when clicking on any menu, is that several commands have a keyboard shortcut that is displayed at that point. Take a look, for example, at the Debug menu and notice all the keyboard shortcuts that appear on the right side of this image:

Component #2: Toolbar

Again, if you’re a computer user, a toolbar is an item that you’ve probably seen many times before. You’re probably aware that a toolbar contains on-screen buttons, icons, menus and other similar elements that you can use while working with the VBE.

The toolbar that appears in the screenshot above is called the Standard toolbar. This is the only toolbar that the Visual Basic Editor displays by default. There are, however, 3 other basic toolbars:

- The Debug toolbar.

- The Edit toolbar.

- The UserForm toolbar.

In addition to the above, the VBE gives you the possibility to customize the toolbars in several ways.

You can change all of these settings by going to the View menu and selecting “Toolbars”. The Visual Basic Editor displays a menu with the 4 different toolbars and the option to access the Customize dialog.

The toolbars with a checkmark to their left are those currently displayed by Excel. You can add or remove a checkmark in order to display or hide a particular toolbar by clicking on its name. For example, in the screenshot below, only the Standard toolbar is being displayed.

If you click on “Customize”, the Visual Basic Editor displays the Customize dialog, which looks as follows:

Using this dialog box, you can control additional aspects regarding the toolbars that are displayed by the VBE. This includes, for example, the possibility of controlling the display of the Shortcut Menus toolbar or adding new toolbars.

You may be wondering what toolbar display set up is commonly applied by VBA users. In practice, there are different opinions.

- Some advanced VBE users use the default settings.

- However, other advanced VBA users display several toolbars.

You can also add commonly used commands that aren’t by default in the Standard toolbar.

Component #3: Project Window / Project Explorer

The Project Window, also known as the Project Explorer, is useful for navigation purposes.

This is the section of the Visual Basic Editor where you’ll be able to find every single Excel workbook that is currently open. This includes add-ins and hidden workbooks. More particularly, each Excel workbook or add-in that is open at the moment appears in the Project Explorer as a separate project.

A project is (basically/simply) a set of modules. If it makes it easier to understand you can take John Walkenbach’s explanation in Excel VBA Programming for Dummies, who says that a project can be seen as “a collection of objects arranged as an outline”.

As explained by Walkenbach in Excel 2013 Power Programming with VBA, each project may have the following nodes:

- A node called “Microsoft Excel Objects” always appears in any project. This node usually contains 2 types of objects:

- #1: Each worksheet in the relevant Excel workbook. In other words, each of the worksheets is considered a separate object.

- #2: The Excel workbook itself, called “ThisWorkbook”.

- The Modules node appears when the project contains VBA modules.

- If the project contains UserForm objects, which are used to create custom dialog boxes, the Project Explorer displays a node called “Forms”.

- A project can also contain class modules (modules that define a class) and, in that case, the Project Window displays a node called “Class Modules”.

- Finally, if a project has references, there is a node called “References”.

Let’s take a look at how all of this looks in the VBE interface:

In the screenshot below, the only project that appears is the Excel workbook “Book 1. xlsm”. Within the Microsoft Excel Objects node, you can see that the Excel workbook has 2 worksheets. Finally, this particular project contains 1 VBA module and, therefore, the Modules node is visible. There are, however, no UserForm objects, class modules or references. Therefore, the Forms, Class Modules and References nodes don’t appear.

You can expand or contract the items that appear in the outline by double-clicking on them or by clicking on the “+” or “-” that appear to the left of each item, depending on the case.

You can also control whether the items that are displayed in the Project Window appear in a hierarchical or a non-hierarchical list. You change this setting by clicking on the Toggle Folders button of the Project Window.

The screenshot above shows items being displayed in a hierarchical list. When displayed in a non-hierarchical list, the Project Window looks roughly as follows:

You can also hide or unhide the Project Explorer itself. I explain how to do this below.

How To Display The Project Window

If you can’t see the Project Explorer, you can make the Visual Basic Editor display it by using any of the following methods:

- Clicking on “Project Explorer” in the View menu.

- Clicking on the Project Explorer icon in the toolbar.

- Using the keyword shortcut “Ctrl + R”.

How To Hide The Project Window

You can hide the Project Explorer by using either of the following methods:

- Clicking on the close button of the Project Window.

- Right-clicking anywhere on the Project Explorer and selecting “Hide”.

Component #4: Properties Window

The Properties Window displays the properties of the object that is currently selected in the Project Explorer and allows you to edit those properties.

Just as with the Project Window, you can hide or unhide the Properties Window. You’re likely to (eventually) work with the Properties Window, particularly in the context of creating UserForms. If you’re just beginning to use the VBE, you probably won’t need this window too much.

In any case, let’s take a look at how you can hide or unhide the Properties Window.

How To Unhide The Properties Window

You can get the Visual Basic Editor to show the Properties Window by using any of the following methods.

- Clicking on “Properties Window” within the View menu.

- Clicking on the Properties Window icon.

- Using the “F4” keyboard shortcut.

How To Hide The Properties Window

You can get the Visual Basic Editor to hide the Properties Window by doing either of the following:

- Click on the Close button of the Properties Window.

- Right-click on the Properties Window and select “Hide”.

Component #5: Programming Window / Code Window / Module Window

As you may expect, the Code Window of the Visual Basic Editor is where your VBA code appears, and where you can write and edit such code. At the beginning, though, the Programming Window is empty as in the screenshot above.

There is a Code Window for every single object in a project. You can access the window of a particular object by going to the Project Explorer and doing any of the following:

- Double clicking on the object. The main exception to this rule are UserForms. If you double-click on a UserForm, the Visual Basic Editor displays the UserForm in Design view, a topic I’ll cover in future tutorials.

- Selecting the object and, then, clicking on “Code” in the View menu.

- Selecting the object and clicking on the View Code icon that appears at the top of the Project Explorer.

- Right-clicking on the object and selecting “View Code”.

- Using the keyboard shortcut “F7”.

Component # 6: Immediate Window

The main purpose of the Immediate Window is to help you noticing errors, checking or debugging VBA code.

The Immediate Window is, by default, hidden. However, as with most of the other windows, you can unhide it. Let’ take a look at how you can do both the hiding and the un-hiding:

How To Unhide The Immediate Window

You can unhide the Immediate Window by doing either of the following:

- Clicking on “Immediate Window” in the View menu.

- Using the “Ctrl + G” keyboard shortcut.

However, as explained in Excel VBA Programming for Dummies, if you’re just getting started with the VBE “this window won’t be all that useful”. Therefore, if you’re just beginning to work with macros and Visual Basic for Applications, you probably don’t need to display the Immediate Window.

If you’re a more advanced user, you’ll probably want to have the Visual Basic Editor show the Immediate Window, since this can be very useful.

How To Hide The Immediate Window

You can hide the Immediate Window using either of the following methods:

- Click the Close button.

- Right-click on the Immediate Window and select “Hide”.

You already know that:

- The VBE allows you to customize several aspects.

- On your way to becoming a macro and VBA expert you’ll probably spend a significant amount of time working with the Visual Basic Editor.

Therefore, its important to have a basic idea of…

How To Customize The Visual Basic Editor

If you want to customize the Visual Basic Editor, the first thing you’ll want to do is open the Options dialog. To do this, go to the Tools menu and click on “Options”.

The Options dialog looks roughly as follows.

As you can see, there are plenty of settings you can modify. In most cases, you can enable or disable an option by clicking on the blank box to the left of it. If there is a checkmark, the option is enabled. If the box is empty, the option is not enabled.

In the screenshot above, the only option that is not enabled is “Require Variable Declaration”.

For the moment, let’s take a look at some of the most common suggestions made by Excel experts. The following sections go separately through each of the 4 tabs in the Options dialog:

- Editor.

- Editor Format.

- General.

- Docking.

Editor Tab

The Editor tab is where you can determine the settings for the Code Window and Project Window. Let’s take a look at the main settings of this tab.

Code Settings

Setting #1: Auto Syntax Check.

This option allows you to determine what happens when you make a syntax error while entering VBA code. There are 2 options:

- If Auto Syntax Check is enabled, a dialog box pops up as soon as the VBE discovers that you’ve made a syntax error. This dialog box gives you a rough idea of what mistake you’ve made. Additionally, the Visual Basic Editor highlights the syntax error by using a different font color (usually red).

Let’s take a look at the VBA code for a very simple macro that deletes rows when some of the cells are blank. The second statement of this macro is “Selection.EntireRow.SpecialCells(xlBlanks).EntireRow.Delete”. If, for example, I press the Enter key after “Selection.”, the Visual Basic Editor gives me the following warning signs:

- If Auto Syntax Check is disabled, the Visual Basic Editor displays syntax errors in a different font color (usually red). Under this setting, no dialog boxes pop on your screen.

In the case of the syntax error used as an example above, the VBE looks roughly as follows:

Should you enable or disable the Auto Syntax Check?

This decision comes down to personal preference and knowledge of Visual Basic for Applications.

You may want to disable the Auto Syntax Check if you:

- Think that having dialog boxes popping up anytime you make a syntax error is annoying.

- Have enough knowledge of VBA in order to find out what is the problem with a statement that has a syntax error.

Some advanced VBA users are of the opinion that Auto Syntax Check should be disabled. The main reason for this is that the VBE highlights the error by (by default) using red font. In this context, the message box displayed by the VBE may be redundant.

However, if you’re a beginner, keeping the Auto Syntax Check enabled can be of great help.

Setting #2: Require Variable Declaration.

This option allows you to determine whether the Visual Basic Editor automatically inserts a statement at the beginning of any new VBA module to require that you define (explicitly) all the variables that you use in those modules. This statement is:

Option Explicit

Note that changing the Require Variable Declaration setting only affects future modules. Modules that are already in existence when you modify the setting are not affected.

As explained in Excel VBA Programming for Dummies, you should get used to defining explicitly all the variables that you use. In that sense, it may make sense to enable the Require Variable Declaration option. Some advanced VBA users say that you should enable Require Variable Declaration. One of the (main) benefits of enabling Require Variable Declaration is the fact it reduces the risk of errors arising out of misspelled variable names.

The case for enabling Require Variable Declaration is even stronger if you’re beginning to use the VBE. In this context, Require Variable Declaration (usually) saves you time when debugging and improves your understanding of Visual Basic for Applications.

Despite the above, some advanced Excel users keep this option turned off.

Setting #3: Auto List Members.

The Auto List Members settings allows you to determine whether, while you’re typing VBA code, the Visual Basic Editor displays a list of options that can be used to complete the statement you’re writing. The list generally includes methods and properties that may apply to the object that you’ve just finished typing.

Let’s see how this looks in practice by using the VBA code of the first macro that I explain in this blog post, and whose purpose is to delete an entire row if there are blank cells in specified cell range. In particular, let’s take a look at the second statement, which is “Range(“E6:E257″).Select” and see what happens while I’m typing it:

The screenshot below shows how the Visual Basic Editor automatically displays a list to help me complete the statement:

If you scroll down the list, you’ll notice that one of the suggestions included in that list is “Select”, which is what we’re looking for.

Auto List Members has several advantages, including the following:

- The Visual Basic Editor may show you properties and methods that you weren’t aware of.

- The list displayed by the VBE updates itself automatically as you type characters. For example, continuing with the same example as above, the screenshot below shows the suggestions made by the Visual Basic Editor after I’ve partially typed “Selection”:

- You can avoid typing. This is due to the fact that you can enter any of the members that appear in the list by selecting it and pressing the Tab key or double-clicking on the relevant member.

- When you use Auto List Members, you reduce the risk of making syntax errors.

Overall, Auto List Members is probably one of the most helpful features of the Visual Basic Editor. Unless you have a very compelling reason to do otherwise, enable it.

Setting #4: Auto Quick Info.

The Auto Quick Info setting allows you to determine whether the Visual Basic Editor displays information about the arguments of functions, properties and methods as you type them.

To see how Auto Quick Info works in practice, let’s go back once more over the statement “Range(“E6:E257″).Select” which I used to illustrate the Auto List Members option above. The screenshot below shows how the VBE helps me while I am typing the range:

Just as the Auto List Members setting, Auto Quick Info is a really helpful feature that you’ll probably want to keep enabled.

Setting #5: Auto Data Tips.

Auto Data Tips works when you’re in break mode, where program execution is temporarily suspended. This occurs for example when debugging VBA code, a topic I will cover in future tutorials.

If Auto Data Tips is enabled, and you’re in break mode, the Visual Basic Editor displays the value of a variable when you place the cursor over it.

Let’s take a look at Auto Data Tips in action. For these purposes, I use the VBA code for a macro that deletes an entire row when the row is completely empty. This particular macro has 2 variables: aRow and BlankRows. In the screenshot below, Excel displays the value of the variable BlankRows (BlankRows = Nothing) when I place the cursor on top of it:

This is another option that you’ll probably like to enable. This is particularly useful in the context of debugging.

Setting #6: Auto Indent.

This setting is self-explanatory. If you have Auto Indent enabled, the indentation of each line of VBA code is the same as the indentation of previous line.

In addition to the above, you can determine what is the indentation width by inputting a value in the Tab Width box. The default number of characters to indent is 4. The value you input here must be between 1 and 32.

Some advanced VBA users use a different number of spaces (usually less than 4) for the tab width. The reasoning behind using less indentation is that it keeps code from extending too far into the right of the screen. Other advanced VBA users suggest that if you’re not using a fixed width font (as I suggest below), it may advisable to increase the number of characters (used to indent) to have clear levels of indentation in your Code Window.

To see how this works in practice, let’s take a look at the piece of VBA code that appears in the previous example where I illustrated Auto Data Tips. The full VBA code of that macro looks as follows:

You’ll notice that, near the end, there are three statements that have exactly the same indentation. The image below highlights them:

Let’s assume that I am writing this piece of code and I’m about to type “BlankRows.Delete”, the second of the 3 statements I highlight in the image above:

- If Auto Indent is turned on, once I press the Enter key after “Application.ScreenUpdating = False”, the VBE takes me to a new row with exactly the same indentation. Notice the location of the cursor in the screenshot below:

- The result of pressing the Enter key is different if Auto Indent is not enabled. Check out what happens when this is the case and compare the location of the cursor between the image below and the image above:

Now, the cursor appears at the left margin of the Programming Window, regardless of the indentation of the previous row.

Appropriate indentation is very important. Therefore, you’ll probably want to enable Auto Indent and set a tab width that works well for your particular circumstances and VBE settings.

Window Settings

Setting #1: Drag-and-Drop Text Editing.

If you enable the Drag-and-Drop Text Editing, the Visual Basic Editor allows you to move pieces of text by dragging and dropping them with your mouse.

Whether you enable this option or not depends on your own taste. I prefer to use the keyboard to copy and move pieces of VBA code. However, you may prefer to use the mouse to drag and drop.

Even if you don’t plan to use it much, enabling Drag-and-Drop Text Editing doesn’t do harm.

Setting #2: Default to Full Module View.

This option makes reference to, and regulates, how procedures are displayed in the Programming Window.

- If Default to Full Module View is enabled, procedures generally appear as a single list in the Code Window.

Take a look, for example, at how 3 macros for deleting rows with empty cells appear in the following screenshot.

- If the option is turned off, you’ll only be able to see 1 procedure at a time. You can use the Procedure Box, which is the drop-down menu at the upper right corner of the Programming Window, to switch between the different procedures.

Continuing with the example of the macros for deleting rows with empty cells, this looks roughly as follows:

You can also turn the Full Module View on and off using the Procedure View (where you can only see 1 procedure at a time) and Full Module View (where you can see all the procedures as a single list) buttons that appear on the lower left corner of the Programming Window.

This is another setting where personal taste is important. I leave Default to Full Module View enabled and my guess is that most Excel users would prefer to do the same.

Setting #3: Procedure Separator.

This setting is kind of self-explanatory. If enabled, it separates the procedures in the Code Window with a bar. This looks roughly as follows:

Without procedure separators, the Code Window (with the same macros that appear above) looks roughly as follows:

You’d probably agree that the first screen is more organized and makes it easier to distinguish between the different procedures. If that’s the case, you’d prefer to enable Procedure Separators.

In certain cases, there may be reasons to disable Procedure Separators but this is not very common.

Editor Format Tab

As implied by its name, the Editor Format tab is where you can format the editor. In other words, here is where you can customize the way the VBA code looks.

On the right side of the Options dialog, you’ll notice that there is a Sample box. Here is where the VBE provides you an example of how the text in the Visual Basic Editor looks under the current settings. For example:

The Editor Format regulates the way the Visual Basic Editor looks using 4 sections. Let’s take a look at each of them.

Section #1: Code Colors.

The Code Colors settings allows you to determine 3 characteristics for any type of text: font color, highlighting color and margin indicator. You can adjust these settings in 2 simple steps.

Step #1: Determine The Category Of Text You Want To Configure.

You can select which type of text you want to adjust by selecting it in the first list that appears on the upper left corner of the Options dialog.

Step #2: Adjust The Foreground, Background and Indicator Settings.

Once you’ve selected the type of text whose settings you want to modify, you can proceed to set the following 3 characteristics by using the relevant drop-down menus:

- The font color, determined by “Foreground” in the Options dialog.

- The highlighting color, set by “Background”.

- Whether the Visual Basic Editor displays an indicator on the margin of the Programming Window, and the color of that indicator.

In order to understand how this looks in practice, let’s take a look at the default settings for 2 types of text.

- As you’ve seen above (when reading about the Auto Syntax Check option), the Visual Basic Editor highlights syntax errors by making their font color red (by default).

The following screenshot shows the configuration for this type of text in the Options dialog:

- One of the screenshots I use above (when explaining Auto Data Tips) shows text highlighted in yellow. This is known as Execution Point Text and its configuration looks as follows:

Code Color settings are, as many other of these settings, a matter of personal taste. I prefer to leave the default colors. However, you may want to play around with the settings to find the configuration you like the most.

Section #2: Font.

As you probably expect, Font settings allow you to determine which font is used to display the VBA code in the Programming Window.

The default font is Courier New and my suggestion is that you keep it. The reason for this is that this font is fixed-width. In fixed-width fonts:

- All of the characters are the same width; and (therefore)

- Use the same amount of horizontal space.

This (usually) enhances the readability of your VBA code. For example:

- All characters are appropriately aligned; and

- You can (more) easily identify multiple or missing spaces.

Section #3: Size.

This is another setting that is self-explanatory. Here is where you can specify the font size used in the Code Window. This setting is a matter of personal taste, although factors such as the monitor you’re using may affect your decision.

Section #4: Margin Indicator Bar.

You can use this setting to determine whether to turn on or off the margin indicator bar.

So, what is the margin indicator bar?

This is the grey bar that appears on the left side of the Programming Window of the VBE. It displays very useful indicators that’ll help you, for example, when debugging your VBA code.

In the last screenshot above, I showed you the Code Colors settings for Execution Point Text. Now, let’s take a look at how Execution Point Text appears in the Code Window. Notice the indicator for this text in the margin indicator bar.

This is one of the settings that you’ll want to turn on. As mentioned above, margin indicators can be very useful when working on the Visual Basic Editor.

General Tab

The General tab of the Options dialog contains settings that fall in a variety of categories such as form, error handling and compiling. Additionally, several of them are relevant only for more advanced topics, such as debugging. Therefore, I only provide a rough explanation of the different options that are available in this tab.

When you’re starting to work with the VBE, the default settings in this tab (usually) work well enough.

Setting #1: Form Grid Settings.

Form Grid Settings allow you to control the way in which the VBE handles UserForms. This is a more advanced topic that I may cover in future tutorials.

Setting #2: Show ToolTips.

ToolTips are descriptions that the Visual Basic Editor can display in order to help you understand a particular toolbar button. If Show ToolTips is enabled, ToolTips are displayed automatically whenever you hover over a particular button.

As an example, the following image shows the ToolTip for the Project Explorer button in the VBE Standard toolbar:

Having ToolTips enabled is generally considered useful.

Setting #3: Collapse Proj. Hides Windows.

This option does what its title says: when you collapse a project in the Project Explorer, it hides any window related to that particular project. This (generally) applies to project, UserForm, object or module windows.

Let’s take a look at how this looks in practice. Notice how, in the following image, the project “Book 1.xlsm” is expanded and you can see the Programming Window that corresponds to Module1.

Compare the above with the next screenshot. In this image, I have simply collapsed the project in the Project Window. As a result, all related windows (the most prominent being the Code Window) are hidden.

If you expand the project again, the windows that have been hidden are restored in their previous positions.

Enabling Collapse Proj. Hides Windows is, usually, a good idea.

Setting #4: Edit and Continue & Notify Before State Loss.

When the Notify Before State Loss setting is enabled, the VBE issues you a notification if the following conditions are met:

- You’re running VBA code.

- You attempt to do something that requires the resetting of all the variables in the module.

Setting #5: Error Trapping.

As implied by its name, error trapping makes reference to how errors are trapped and handled when the VBA code runs.

Let’s take a quick look at what each of the 3 available options does:

- If you choose “Break on All Errors”, break mode is entered whenever there is an error in the VBA code. This includes cases where there may be an error handler or the code is in a class module. This option may be useful when doing debugging. However, at the beginning, I suggest that you don’t choose it.

- When “Break in Class Module” is enabled, break mode is entered if there is an error in the VBA code within a class module. This is the setting suggested by several advanced VBA users.

- “Break on Unhandled Errors” is the default setting. This is also the choice suggested by several advanced VBA users. Under this setting, break mode won’t be entered as long as there is an error handler that traps the error. However, if there is no adequate error handler, break mode is entered.

Setting #6: Compile.

The Compile settings allow you to control the moment at which VBA code is compiled.

Why is this important?

At this moment is not necessary to go too deep into the concept of compiling. For the moment, is enough to understand that applications written in a particular programming language (which can’t be executed by a computer) need to be transformed into another language (that can be executed by the computer). More precisely:

- VBA code must be compiled before it can be executed; but

- Not (absolutely) all VBA code in a project must be compiled before certain (usually the initial) parts of the VBA code can start running.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at the 2 options that appear in the General tab.

Option #1: Compile On Demand.

Compile On Demand means that the Visual Basic Editor compiles the VBA code as is needed. Let’s take a look at an example to understand how Compile On Demand works:

Let’s assume, for example, that you’re working with 5 procedures named “Procedure1” through “Procedure5”. You want to first run Procedure1. Procedure1 calls Procedure2 which, in turn, calls Procedure3. Procedure3 doesn’t call any further procedures.

If Compile On Demand is enabled, Procedure1 is the only procedure that is compiled at the beginning of the process described above. No additional code (from the other procedures) is compiled until the relevant procedure is called. Once Procedure1 calls Procedure2, the code of Procedure2 is compiled. Similarly, once Procedure2 calls Procedure 3, Procedure3 is compiled. Since Procedure4 and Procedure5 aren’t called, their codes are not compiled.

If Compile On Demand is disabled, the code of all the procedures (Procedure1 through Procedure5) is compiled before Procedure1 starts running. As you can imagine, under this scenario, the procedure you want to execute starts running a little bit later since there is more code to be compiled. Additionally, you won’t be able to run the procedure you want (Procedure1) if there is any language or compile error in any of the other procedures (Procedure2 to Procedure5).

Option #2: Background Compile.

This option is only available if you have enabled Compile On Demand. As implied by its name, Background Compile means that idle time is used for purposes of finish compiling a program in the background.

Docking Tab

The Docking tab is used to set the behavior of the different windows of the Visual Basic Editor. More precisely, is used to determine whether a tab docks, a concept that I explain below.

A window is dockable if the box to its left has a checkmark. Otherwise, the window isn’t dockable. In the screenshot below, the only window that isn’t dockable is the Object Browser.

You may be wondering what exactly happens when a window is dockable. The difference between being dockable and not is the following:

- When a window is docked, the VBE fixes that window in a certain spot along one of the edges of the Visual Basic Editor window.

Check out, for example, how the Project Explorer and the Properties Window are fixed along the left edge of the VBE window:

- If windows are not docked, you just have a bunch of windows within the VBE.

Compare the screenshot above with the following image, where the Project and Properties Windows are not docked. This image is only for illustration purposes. You can maximize and minimize these windows by clicking on the relevant buttons at the top right hand of the relevant window.

As you probably expect, I suggest that you dock most windows. Having the different VBE windows docked makes it easier to locate the window that you need when you need it, and generally improves the user experience.

If your screen is not big enough to dock the windows along the edges of the VBE, you may want to undock some of them. If you do this, you’ll probably have to switch between windows in order to get to the one you want. The advantage of having few (or none) docked windows is that you’ll have more space for your Code Window.

How To Add VBA Modules

When you record a macro, Excel automatically inserts a module into the Excel workbook you choose before beginning to record. However, there are other opportunities where you may want to add other VBA modules. You can do this by using either of the following methods.

How To Add A VBA Module: Method #1

Under this method, you can add a VBA module to a project in 2 easy steps.

Step #1: Select Project To Add Module To.

Go to the Project Explorer and select the project to which you want to add a module. For example, in the screenshot below, a module would be added to “VBAProject (Book 1.xlsm)”, which is the only open project.

Step #2: Insert Module.

Go to the Insert menu and select “Module”.

How To Add A VBE Module: Method #2

In this case, you add a module by right-clicking on the relevant project (in the Project Window), choosing “Insert” and clicking on “Module”.

How To Remove VBA Modules

Just as you can add new VBA modules to a project, you can remove them by using either of the 2 methods explained below. As a general rule, you can only remove VBA modules. You cannot remove other code modules, such as those for:

- Worksheets (Sheet#); or

- The workbook (ThisWorkbook).

How To Remove A VBA Module: Method #1

In this method, you can remove a VBA module by following 2 simple steps.

Step #1: Select Module To Be Removed.

Go to the Project Window and select the relevant module. For example, if you wanted to remove “Module2”.

Step #2: Remove Module.

Go to the File menu and select “Remove module_name”, where “module_name” stands for the name of the module you want to remove. For example, when removing “Module2”, the File menu looks roughly as follows:

How To Remove A VBA Module: Method #2

Under this method, you simply right-click on the relevant module in the Project Explorer and select “Remove module_name”. For example, in the case of “Module2”:

Regardless of which of the 2 methods above you use to remove a VBA module, the Visual Basic Editor displays a dialog asking you whether you want to export the module before actually removing it.

Most of the times, the reason why you’re removing a VBA module is because you don’t need the VBA code within it. In those cases, click “No”.

If, for any reason, you actually want to export the module, click on “Yes”. However, if you are interested in learning how to export objects in the Visual Basic Editor, take a look at the next section of this Excel tutorial…

How To Export Or Import An Object In The Visual Basic Editor

Let’s assume that you’re working on a VBA project and want to be able to access a particular object separately and use it, for example, in future VBA projects or share it with your colleagues. To do this, you need to learn how to export and import objects in the VBE.

But first, let’s define exporting and importing:

- Exporting an object means taking a particular VBA object from a VBA project and saving it in a separate file. Graphically, this looks as follows:

- Importing is, basically, the opposite of exporting. More precisely, it means taking a VBA object from a separate file and into a particular VBA project. Graphically:

You can’t export the objects that appear under the References node in the Project Explorer.

Also, if you export a UserForm object, the code associated with that UserForm is also exported. Therefore, exporting a UserForm actually creates 2 separate files.

Now, let’s take a look at how to export an object in the Visual Basic Editor…

How To Export An Object In The Visual Basic Editor

First of all, if your purpose for exporting an object is to use it another project, you may not need to go through the whole exporting and importing process. In most cases, you can simply do the following to have the object in both projects:

- Open both the original and the destination projects.

- Use the mouse to drag the relevant object from the original project to the destination project.

If you still need to export an object using the Visual Basic Editor, simply follow these 3 easy steps.

Step #1: Select The Object You Want To Export.

Go to the Project Window and click on the VBA object you want to export. For example, if you want to export Module2:

Step #2: Instruct The VBE To Export The Object.

You can instruct the Visual Basic Editor to export the object by using either of the following methods:

- Clicking on “Export File…” in the File menu:

- Right-clicking on the object you want to export and selecting “Export File…”.

- Using the “Ctrl + E” keyboard shortcut.

Step #3: Save The File.

Once you’ve instructed the VBE to export the object, the Export File dialog appears.

This dialog probably looks quite familiar. Here you get to save the exported object as any other file. Basically, choose the folder you want to save the file in (in the screenshot below is “Example”), give the file a name (in the image below is “Module2”) and click “Save”.