«Jot» and «tittle» are not everyday words in English. What do they mean and how should Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:18 be understood? Jerusalem Perspective‘s editor-in-chief, David Bivin, tackles these questions on behalf of a subscriber’s request for help.

| Rather listen instead? |

| JP members can click the link below for an audio version of this essay.[*]

Premium Members One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership Login & Purchase |

In a statement about the continuing validity of the Torah, Jesus uses a difficult-to-understand idiom. The Greek reads: ἕως ἂν παρέλθῃ ὁ οὐρανὸς καὶ ἡ γῆ, ἰῶτα ἓν ἢ μία κεραία οὐ μὴ παρέλθῃ ἀπὸ τοῦ νόμου (“…until pass away the heaven and the earth, iota one or one point by no means will pass way from the law…”; Matt. 5:18).

Most English translations have not helped readers understand the idiom:

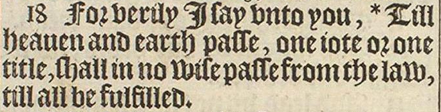

“Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law…” (KJV)

“…till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the law…” (RSV)

“…until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law…” (ESV)

Premium Members

If you are not a Premium Member, please consider becoming one starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually):

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than a membership, you may also purchase access to this entire page for $1.99 USD. (If you do not have an account select «Register & Purchase.»)

Login & Purchase

The featured image shows the text of Matt. 5:18 in The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament and the New: Newly Translated out of the Originall Tongues: & with the former Translations diligently compared and revised by his Majesties Special Commandment Appointed to be read in Churches Imprinted at London by Robert Barker Printer to the Kings most Excellent Majestie Anno Dom. 1611 (also known as The King James Version).

Premium Members

If you are not a Premium Member, please consider becoming one starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually):

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than a membership, you may also purchase access to this entire page for $1.99 USD. (If you do not have an account select «Register & Purchase.»)

Login & Purchase

John’s Gospel says that «In the beginning was the Word and the Word was God…» I don’t understand the meaning of «the Word?» Is the «Word» a person? How can a word be God?

The prologue of John’s gospel is an important work within the New Testament because it provides perhaps the clearest statement of Jesus’ identity in spiritual terms. Essentially, John’s prologue states Jesus is and always has been God, but it also seeks to explain, to a certain extent, the nature of Jesus’ existence and His role within the Godhead.

Let’s start by examining the opening verses in John’s Gospel:

John 1:1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

John 1:2 He was in the beginning with God.

John 1:3 All things came into being through Him, and apart from Him nothing came into being that has come into being.

John uses the Greek word logos to describe Jesus «in the beginning,» or before creation and time began. Logos means word, but specifically, it means the spoken word or a statement. Jesus is God’s spoken word, according to John.

John then explains that the Word (Jesus) was «with» God and «was» God. This statement yields two important conclusions regarding Jesus and the Trinity: Jesus is God and existed from the beginning as God, yet Jesus’ existence is somehow distinct from God the Father. Jesus was «with» God and «was» God at the same time. This is the mystery of the Trinity: all three Persons in the Godhead are One God and yet all are distinct from one another.

Moving to verse 3, John says that it was the Word (Him) that created all things. From this statement, we begin to see why Jesus is called the «Word» by John. Consider these facts we learn from John’s Gospel and elsewhere in Scripture:

First, we know from scripture that God the Father is Spirit (John 4:24), meaning He doesn’t exist in physical form. So, there is no physical substance to God the Father. The Creation cannot experience the Father as He truly is since we are bound to a physical dimension yet He is not physical.

Secondly, we know that the third member of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, is likewise spirit only and therefore invisible (John 3:6-8). He can only be known by observing His work in the Creation, Jesus says in John 3. Therefore, Jesus is the only member of the Godhead Who takes on physical form, and for that reason, He is the member of the Godhead responsible for creating all things physical. As John said in chapter 1, all things were made by and through Jesus. Paul echos the same thing in Col 1:15-17.

Moreover, Paul teaches in Colossians that Jesus is the «image of the invisible God,» meaning He is the only member of the Godhead Who entered into and become a part of physical Creation. For this reason, Jesus can be perceived in a physical sense because He is incarnate. In fact, the incarnation of Jesus was intended, in part, to bring mankind a greater awareness of Who God is and what He is like. Therefore, Jesus is both the source of all Creation and an Ambassador of the Godhead into that creation.

Next, consider how the Creation itself was established in Genesis 1. Genesis 1 teaches that the world was created by the spoken word of God (note the repeating phrase in Genesis 1, «Then God said…»). So when God the Father determined to create the universe and everything in it, He «spoke» it into existence. But as John said in verse 3, Jesus was the One who made all things, therefore we can say that Jesus was God’s logos, or spoken Word.

We can begin to understand this partnership (at least to some degree) by drawing an analogy to how our own thoughts and words reach into the physical world. When we desire to command something to happen in the world around us, we must first conceive the idea in our minds. No one can see our thoughts. They are invisible, yet they certainly exist. Without our thoughts, we could purpose to do nothing at all.

If our thoughts are to become visible in some way, they must move from the invisible realm of our mind and into the physical world. The progression from invisible to visible requires we transfer our invisible thoughts into a spoken command. The brain communicates our thoughts to our mouth where it becomes logos: spoken words. Once the spoken word leaves our mouth, it enters the physical world and yields its intended effect. This simple analogy helps explain how God the Father worked with God the Son (i.e., the Word) to establish Creation.

God the Father purposed to create the universe and all that it contains, and when the moment arrived to make it so, God’s «thoughts» were made a physical reality by the Son, Who brought all things into being according to the Father’s plan, and now the Spirit of God attends to the Creation after its formation.

This is John’s meaning when he says that Jesus is the Word. He meant that Jesus is the physical manifestation of God the Father, just as a spoken word is the physical manifestation of our inner thoughts. Until Jesus took action and created the universe, there was no physical reality to God’s presence. But when God «spoke» (i.e., when Jesus took action), the Creation came into existence.

Later, Jesus arrived in Person to meet with His creation, and as Jesus spoke His words to His disciples, He fulfilled the Father’s purpose by providing a physical representation of the Godhead to His creation. Hebrews says it this way:

Heb. 1:1 God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways,

Heb. 1:2 in these last days has spoken to us in His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world.

Heb. 1:3 And He is the radiance of His glory and the exact representation of His nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power…

Paul reiterates this same thought in Colossians when he says:

Col. 1:15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.

Col. 1:16 For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities — all things have been created through Him and for Him.

Jesus is the Word because He was the means through which the Father brought all physical reality into existence and because He is the One Who represents the Father’s invisible nature and character to that creation. Just as your spoken word is the physical manifestation of your thoughts and personality, Jesus is the «Word» of the invisible God to His creation.

Even as a lover of books, this might be one of the most terrifying pictures I’ve ever seen.

“The Bible is not the Word of God, Jesus is. John says he is the Eternal Logos, the true Word spoken from all eternity, and to put such a focus on the Bible as the Word of God is to take it off their point: Jesus. In fact, it’s tantamount to bibliolatry–elevating the Bible to the 4th person of the Trinity.”

Ever heard something like that before? It’s become a truism among many of the Christian internet set, and something like it has been popular in theological circles for some time now.

I must admit, when I first heard the slogan myself, I was thrown off a bit. I mean, John does identify Jesus as the Logos, the Word, of God from all of eternity–the truest and deepest reality Father is eternally speaking. What’s more, it’s true that from time to time you can run across someone in a fundamentalist church who treats the Scriptures as if they were dropped from heaven and yet remain utterly oblivious to its central content. I can begin to see what motivates some to adopt it.

However, after the initial appeal, it appears to me that this is a mistaken move that many (though not all) use as a lead-up to falsely pitting Christ against the Scriptures. In fact, I’ve come to see this as sadly little more than a rhetorical sleight of hand, passing itself off as serious theology.

A Word About Words – The first is concerned with the basic nature of language and the simple text of the Bible. It should be an obvious point that words or phrases can, quite comfortably, have more than one proper use, or an expanded lexical range. For example, the phrase “God’s will” can refer to God’s will of command expressed in his explicit commands, but it can also refer to God’s will of decree by which he governs history. Both meanings are appropriately designated by that phrase, and context will usually clarify any confusion on that point. It ought to be uncontroversial to say the same thing is true of the phrase “the Word of God.”

At the most straightforward level, the phrase “The word of God” just means “a word God has spoken.” We find hundreds of references to God’s speech (“the word of the Lord came to”) littered throughout the canon, whether in the Law, the prophets, or the wisdom literature. Every time God spoke to Moses, he heard “the word of God.” Every time a prophet prophesied and used the phrase “Thus says the Lord”, they were speaking the “word of God.” Over and over, we see the preaching of the Gospel in Acts described as the “word of God.” That Jesus Christ is the eternal Logos of God does not change the fact that it is entirely appropriate to speak of the utterances of Jeremiah or Isaiah as the “word of God.” How much more then for the totality of all that God has “breathed out” by his Spirit?

For those worried about confusion on this point, this is why sometimes theologians have gone out of their way to distinguish what they mean by the phrase, specifying “the Word of God incarnate” (ie. Jesus) or “the Word of God written” (ie. the Bible). They know very clearly that one has certain properties that the other doesn’t. For instance, the Son of God doesn’t have the properties of being made up of 66 books by various authors over a period of a thousand years or so. On the other hand, the Bible doesn’t have the property of being eternally-generated by the Father, or being incarnate, crucified, risen, and ascended in glory. Straightforward enough.

So when the author of Hebrews speaks about the Son’s unique revelatory function he says “In the past God spoke to our ancestors through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, and through whom also he made the universe” (1:1-2), it’s important note that he doesn’t follow that up with, “so now that we have this final Word let’s not call those previous communications ‘God’s Word.’” The conclusion simply does not follow.

Which brings me to the next point: the Word’s own view of the words.

Christ himself presents us with the Word.

What Did Jesus Say? I’ve written before that it’s rather misleading to pit Jesus against the OT, or the “red letters” against the black letter sections of the Bible, given his own view of it. Once again, consider:

Is it not written in your Law, “I said, you are gods”? If he called them gods to whom the word of God came—and Scripture cannot be broken— do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, “You are blaspheming,” because I said, “I am the Son of God”? (John 10:34-36)

Not only is Jesus not squeamish about equating the Old Testament Scripture with the “Word of God”, he re-emphasizes their inviolability and authority by adding that they can’t be “broken.” Passages like this could be multiplied ad nauseam. In this he is followed by all of the apostles.

But instead of just repeating myself, J.I. Packer has some wisdom for us on this point:

But who is this Christ, the Judge of Scripture? Not the Christ of the New Testament and of history. That Christ does not judge Scripture; he obeys it and fulfills it. Certainly, He is the final authority of the whole of it. Certainly, He is the final authority for Christians; that is precisely why Christians are bound to acknowledge the authority of Scripture. Christ teaches them to do so.

A Christ who permits His followers to set Him up as the Judge of Scripture, One by whom its authority must be confirmed before it becomes binding and by whose adverse sentence it is in places annulled, is a Christ of human imagination, made in the theologian’s own image, One whose attitude to Scripture is the opposite to that of the Christ of history. If the construction of such a Christ is not a breach of the second commandment, it is hard to see what is.

—“Fundamentalism” and the Word of God, 61–62 (HT: Matt Smethurst)

In other words, if Jesus identifies the Scriptures as God’s Word, why are we so squeamish about following suit?

The Trinitarian Word – Finally, this approach is confused because in doesn’t see that the Bible is the Trinitarian Word of God. Michael Horton calls our attention to the Trinitarian coordinates of inspiration in The Christian Faith. Reminding us of the structure of all trinitarian actions he writes “In every work of the Godhead, the Father speaks in the Son and by the perfecting agency of the Spirit.” (pg. 156) The Bible is the “Word of God” because in all the Law, the narratives, the Psalm, Prophets, Gospels, and Epistles we hear the Father testifying to the Son (John 5:39) by way of the power of the Spirit (2 Pet. 1:21).

We can see something like this understanding in Heinrich Bullinger’s Second Helvetic Confession. After calling attention to the locus classicus establishing this doctrine (“All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching,for reproof,” etc. (II Tim. 3:16–17), Bullinger puts it this way:

SCRIPTURE IS THE WORD OF GOD. Again, the selfsame apostle to the Thessalonians: “When,” says he, “you received the Word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it, not as the word of men but as what it really is, the Word of God,” etc. (I Thess. 2:13.) For the Lord himself has said in the Gospel, “It is not you who speak, but the Spirit of my Father speaking through you”; therefore “he who hears you hears me, and he who rejects me rejects him who sent me” (Matt. 10:20; Luke 10:16; John 13:20). (Chap. 1)

In a sense, it is only as we acknowledge the Bible as the Word of the Father about the Son that we truly see the Son as the Father’s own True Word. It is through the testimony of the Word of God written that we recognize Jesus as the Word of God Incarnate. What’s more, given the current illumination of the text by the Spirit we ought say with Bullinger that “God himself spoke to the fathers, prophets, apostles, and still speaks to us through the Holy Scriptures” about the Son.

At this point I think it becomes clearer that to pit Jesus as the Word of God incarnate against the Bible as the Word of God written is a false choice. It’s not only confused both at the level of language, not the attitude towards the Scripture taught to us by Jesus, but at the deeper level I fear it leads many to denigrate the diverse testimony of God to Christ in Scripture all in the name of elevating him.

So then, is Jesus the Word of God? Yes and Amen. Should we still speak of the Bible as the Word of God? Of course we should–Jesus told us to.

Soli Deo Gloria

- ‘Jesus isn’t the word of God’

- 2nd Helvetic Confession

- bibliolatry

- bibliology

- Heinrich Bullinger

- inspiration

- J.I. Packer

- Michael Horton

- the Word of God

- theology

- Trinitarian word

I was told that the name of Jesus is special, and saying His name in a prayer means it will be answered. Is that true?

Anonymous GodWords Reader

This question has a few layers. Some claim that praying “in Jesus’ name” will ensure that He will give us what we ask. Some believe that we should refer to the Messiah by His ‘actual’ name, which – they presume – is Hebrew. Some go so far as to say that those who get His name wrong are actually worshipping a false god, and that these people can’t be saved as a result.

What name was Jesus given at birth?

My name, given at birth, is Anthony. My nickname is Tony. Some of my friends call me by other nicknames, but all of those names refer to me. You might ask what my “real” name is, and there’s no single answer. Names can be a bit complicated.

Jesus was given a name at birth. According to Matthew 1:21 that name is Iesous. That’s Greek. Because Jesus and His family are Jews, one presumes that they spoke Aramaic or Hebrew. However, Jesus isn’t named with a Hebrew name in the Bible. We see only Iesous.

We know that Iesous is the Greek version of the Hebrew name Yeshua, or Y’shua, or Yehosua. It’s the same name as “Joshua.” At no point do we see Jesus referred to in the Bible as either Yeshua or Y’shua, but it seems reasonable to assume that the angel told Joseph to name Him “Yeshua.” Y’shua and Yehosua are simply other forms of the name, like Tony is to Anthony.

So: what is Jesus’ “real name” in Hebrew? My name in Spanish is Antonio. Since I’m American and my parents spoke only English, it’s okay to assume that my “real name” is Anthony. In the same way, Jesus’ name – according to the Bible – is Iesous… but it’s okay to assume that the angel was speaking Hebrew, and that Joseph actually named the baby Yeshua.

A linguistic timeline

Jesus’ name in Hebrew is Yeshua, which is a shortened version of Yehoshua.

Yeshua translated into Greek is Iesous.

Iesous transliterated into Latin is Jesu.

Jesu became Jesus in English.

So: Jesus’ name, in English, is kind of “Joshua”. Weird, huh? Translators primarily use the name Jesus to differentiate between Joshua (Moses’ right-hand man) and Jesus (Son of God, Creator of the universe, Messiah).

Is it a translation?

A translation conveys meaning, so Iesous inherits its meaning from Yeshua. A transliteration is simply a letter-for-letter switch: the letters in one language are swapped for letters in another language that make the same sounds. Jesus is not a translation, it’s a modernized Latin transliteration of Iesous. Jesu is a Latin word that sounds like the Greek Iesous.

Jesus does not mean “Yahweh saves” or “the Lord saves” or even “He saves”. Despite the fact that Jesus Himself means a great deal to many people, there’s no English meaning to Jesus at all. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with saying that Jesus’ name means “Yahweh saves.” It’s not linguistically correct, but that’s not very important most of the time.

Isn’t there power in Jesus’ name?

No. The word “Jesus” has no magical powers, and saying it accomplishes nothing spiritually. It’s a name. There’s no special power in the name itself.

There’s nothing about the name itself that makes it more likely that God will give you what you pray for. When the New Testament tells us to pray in Jesus’ name, it doesn’t teach us that the name itself is special. It tells us that the person is special. When an ambassador speaks to a foreign leader, they speak “in the name of” – with the authority of – the one they represent. Jesus is an ambassador, speaking to the Father on our behalf… and speaking to us on behalf of the Father.

When we pray, we’re asking God to act on our behalf. There’s nothing in the Bible to support the superstitious notion that speaking His name does anything on its own. That’s more like witchcraft than Christianity… if you say the incantation right, you get the result. It’s nonsense.

The words have no power of their own, and God will either grant what we ask or He won’t. He will do what He knows is best, regardless of how often or how sincerely we say “Jesus.” When we pray in Jesus’ name, we’re pointing to our relationship with the Father… and that’s made possible by our relationship with Jesus. It’s a bit like saying, “We’re friends, right? Would you loan me $20?”

Should we pray in Jesus’ name?

We should feel free to pray in Jesus’ name. If you’d rather say “Y’shua,” that’s okay. Neither will produce magical results just because we speak the words. However: let’s not be superstitious and pretend that our incantations change anything. We’re asking God for help, or praising Him for being so awesome. We should do that all the time.

Interact with me on Twitter!

Craig S. Keener

BECAUSE WE HAVE ADDRESSED THE BACKGROUND of the prologue in some detail above, this opening paragraph merely summarizes that background. John addresses a community of predominantly Jewish Christians rejected by most of their non-Christian Jewish communities because of their faith in Jesus. The leaders of the synagogues make a case similar, or perhaps related, to that of second-century Palestinian rabbis: Judaism is a religion of Torah, and the prophetic, messianic Jesus movement has departed from proper obervance of God’s Word (particularly from orthodox monotheism). John responds that following Jesus not only entails true observance of Torah; Jesus himself is God’s Word, and thus no one can genuinely observe Torah without following Jesus. Jewish language about Wisdom, Torah, and God’s Word (rooted in OT wisdom texts but substantially developed since then) provide John a culturally intelligible (albeit only partly adequate) means to communicate Jesus» deity, supremacy, and perfect relationship with the Father while maintaining Jewish monotheism.

The Preexistent Word (1:1–2)

John connects the three lines in this first verse in rhythmic fashion; as Boismard points out, he avoids monotony «by coupling the clauses together according to a device in vogue among the Semites: the first word of the second and third phrases takes up the last word of the preceding one (Word-Word … God-God).»3193 Together with v. 2, the four lines provide also a full chiasm, which itself subdivides into two smaller chiastic structures:

A In the beginning

Β was

C the word

D and the word

Ε was

F with God

F» and God

É was

D» the word3194

C This one

B» was

Á in the beginning with God

The double chiasms appear as follows:

A In the beginning

Β was

C the word

C and the word

B» was

Á with God

A And God

Β was

C the word

C» This one

B» was

Á In the beginning with God3195

In neither case is the balance exact, but the parallelism of the Psalms and other Semitic poetry is usually similarly inexact. This careful structure opens John’s prologue and Gospe1.

1. In the Beginning (1:1a, 2)

Although λόγος is the subject of 1:1a, b, and c, John has an important reason to open his Gospel with the phrase «in the beginning.» As most commentators observe, «beginning» alludes to the beginning of creation,3196 and the opening words of John’s prologue echo Gen 1:1.3197 This allusion is important precisely because he goes on to speak of creation in 1:3. Although John will go on to depict the advent of a new creation (the usual referent of άρχή in his Gospel, e.g., 2:11; 8:25; 15:27; 16:4; cf. 6:64; 1 John 1:1),3198 he refers here to the literal beginning of creation (cf. 8:44; 9:32; 17:24); not only other Genesis allusions3199 but the explicit reference to the world’s creation in 1(particularly in view of parallels in contemporary literature cited below), the origination of John the Baptist, and so forth, reinforce this point. The opening words establish the plainly Jewish tone of the Gospel, though John’s purpose is to explain Jesus, not simply to expound the text of Genesis as a midrashic expositor would.3200

Early Jewish wisdom texts celebrated the existence of Wisdom «in the beginning,»3201 and Wisdom,3202 Torah,3203 and the Logos3204 were sometimes called «the beginning.» (Although Jewish teachers discovered this use from their exegesis of Prov 8:22, their openness to it might reflect the Greek philosophical use of αρχή as «first principle,» similar to one philosophical understanding of λόγος.)3205 John does imply more than Jewish Wisdom language normally indicated, but it was easier to stretch Wisdom or Logos language to new bounds than to try to communicate Jesus» identity with no point of contact.3206 Paul had earlier used a similar point of contact in Col 1:15–203207 with terms like «image» and «firstborn.»3208 Others have suggested that John may echo the «beginning» of the traditional gospel account;3209 suggesting a play on the «beginning» of Genesis and «the proper beginning for the story of Jesus,» Aune points out that «beginning» in Mark 1«is virtually a technical term in historical and biographical writing, based on the notion that the complete explanation of a historical phenomenon must be based on its origins.»3210

That John intends an allusion to Genesis 1 may be regarded as certain; that he also plays on fuller nuances in postbiblical Wisdom language (identifying Wisdom with the beginning) is quite possible; that he also intends an allusion to the proper «beginning» of the Gospel account is possible, though the strongest evidence (primarily Mark 1:1) is not compelling. For the sake of emphasis 1recapitulates from 1the intimacy of Father and Son in the beginning, at creation (so also 1:3; 8:58); thus those who reject the incarnate Jesus reject God himself. Jesus did not «make himself» God (10:33); he shared glory with the Father before the world began (17:5).

2. The Word’s Preexistence (1:1–2)

Although Johns concept of the Words préexistence surpasses that of his contemporaries (see below on ήν), his language would have impelled readers to recall the contemporary Wisdom language he surpasses.

2A. Wisdom or Torah as God’s First Creation

Many texts depict Wisdom’s creation at the beginning, often including Wisdom’s participation in the creation of the rest of the universe (on which see comment on John 1:3). Thus in Sirach Wisdom exclaims, «Before the world, from the beginning (άπ» άρχής) He created me.»3211 The author declares, «Before all things was Wisdom created, and understanding of counsel from eternity.»3212

First-century Jewish literature similarly stressed that God’s law was «prepared from the creation of the world.»3213 Some second-century Tannaim, identifying Torah with Wisdom in Prov 8:22–23, declared that Torah was God’s first creation;3214 Amoraim followed this teaching.3215 Although later rabbis sometimes claimed that God created six or seven things before the world, they generally listed Torah first.3216 In one scheme where God created six things before the world, for instance, only Torah and the throne of glory were formed before the world, and Torah was created first; God merely contemplated the other «préexistent» creations.3217 (Although many rabbis declared that the Messiah was among those things which existed before the world was formed,3218 more often only the name of, or plan for, the Messiah existed beforehand.3219 Similarly the patriarchs preexisted, but usually only in God’s plan or as spirits in God’s plan.3220 In contrast to the teaching of Wisdom’s/ Torah’s préexistence, teachings concerning préexistent messiahs or patriarchs have little substantial early attestation3221 and should not be regarded as relevant for the study of the Fourth Gospe1.)3222

Rabbis differed, however, on how long before the world God created Torah; some scholars said two thousand years,3223 others said 974 generations.3224 Apart from these elaborations, the earliest form of the Torah idea is identical with the Wisdom image on which it is based: God created Torah before he created anything else.3225

Our extant sources for Jewish opinion indicate that the language of Torah’s existence often served a practical (perhaps homiletic) rather than merely speculative purpose.3226 Various early sources claim that Torah existed before Sinai;3227 in contrast to Genesis’s portrayal of patriarchs who sometimes violated Torah’s later prohibitions,3228

Jubilees has them almost «squeaky clean» on this count,3229 and when whitewashing them is impossible, Jubilees provides an explanation.3230 The rabbis naturally developed this opinion.3231

2B. The Préexistence of Johns Logos

For John, the Word was not only «from the beginning» (άπ» άρχής, 1 John 1:1), but «in the beginning» (John 1:1). Many commentators have laid heavy stress on the verb ήν: in contrast to many Wisdom texts which declare that Wisdom or Torah was created «in the beginning» or before the creation of the rest of the world, John omits Jesus» creation and merely declares that he «was.» This verb may thus suggest the Word’s eternal preexistence;3232 after all, how could God have been without his Word? That God created «all things» through the Word in 1(naturally excluding the Word itself as the agent) further underlines the contrast between the Word and what was created.3233

In short, the verb suggests a preexistence of greater magnitude than that of Wis-dom/Torah in most Jewish texts. One might be tempted to argue that such a suggestion is too much to hang on a mere linking verb; after all, «beginning» could refer only to the rest of creation, as sometimes in Jewish texts, and is defined in this text only by the allusion back to the creation of heavens and earth in Gen 1:1.3234 The temptation to diminish the force of the ήν is probably removed, however, by the literary contrast between Jesus» «becoming» flesh (1:14; cf. 1:6) and his simply «being» in the beginning,3235 and finally eliminated by identifications of Jesus with his Father’s deity throughout the Fourth Gospe1. If John can say that the Word «was God» (1:1c; cf. 1:18), that Jesus claims, «Before Abraham was, I am» (8:58), and that it is appropriate to believe in Jesus as Lord and God (20:28), John’s Jesus is more than merely divine Wisdom.3236 Jesus may remain distinct from and subordinate to the Father and may exercise roles frequently equivalent to the exalted role of Wisdom in Jewish literature; yet he does not precisely fit the traditional categories. John utilizes the closest concept available from his milieu, but modifies it to fit his Christology rather than his Christology to fit beliefs about divine Wisdom.

2C. The Word Was with God (1:1b)

John repeatedly emphasizes Jesus» intimacy with the Father, sometimes in the language of him being with the Father (3:2; 8:29; cf. 8:38; 16:32), as Jesus also is with his disciples (cf. 11:54; 13:33; 14:9, 17, 25; 15:27; 16:4; 17:12). Jesus was with the Father before creation (17:5).

Wisdom texts celebrated the special relationship between God and his Wisdom. Wisdom was present (παρούσα) with God when he made the world;3237 Wisdom lives together (συμβίωσιν) with him;3238 in later rabbis, Wisdom/Torah claims to be «with God» at creation.3239 Johns Logos also has a special relationship with God, indicated in part by the προς with the accusative3240 but even more so by continual reaffirmations throughout this Gospel of their close relationship.3241 Although the image of father and son was not always one of intimacy and harmony (cf. Luke 15:12–13),3242 the picture in this Gospel is that of a perfect, ideal father-son relationship (e.g., 8:29, 35–38). As Appold notes, the motif of Jesus» oneness with God, stressed throughout the Gospel, begins as early as this line.3243

Although one scholar emphasizes John’s statements distinguishing Jesus from the Father (e.g., 14:28) and argues against Jesus» deity in the Gospel,3244 the Gospel is equally clear in affirming Jesus» deity (1:1c, 18; 8:58; 20:28) and in distinguishing him from the Father. John addresses «an identification by nature of two distinct persons,»3245 an image developed by the Athanasian faction at Nicea in a manner consistent with its roots.3246

3. The Word’s Deity (1:1c)

In this line it becomes clear that, although John employs the basic myth of Wisdom as the nearest available analogy to communicate his Christology, it proves inadequate. Jesus is not created like Wisdom (Sir 1:4; John 1:1b), but is himself fully deity (1:1c), bursting the traditional categories for divine Wisdom.3247 It is not surprising that the early centuries of Christians felt that emphasis on Jesus» deity was a major reason for the Fourth Gospe1.3248

Not all writers used the title θεός in the same way. It was the standard term for any deity in traditional Greek religion, but these deities acted in ways both repulsive to first-century Jews and embarrassing to many Greek and Roman thinkers. Deities could prove powerless to help mortals they loved, even mortals who were related to them;3249 some could be captured and questioned for information.3250 By contrast, the God of Judaism was omnipotent (Rev 1:8),3251 though paganism in this period (especially Roman paganism) generally also attributed this trait to the supreme deity.3252 Some pagan deities stole mortals» property3253 and killed those who might let out the secret;3254 deities–often married–could seduce and rape various mortals,3255 but slay such mortals if they proved unfaithfu1.3256 (Their sexual exploits proved fertile ground for early Jewish and Christian critiques of paganism.)3257 Hera could jealously avenge her honor in response to Zeus’s adultery;3258 insulted by mortals» neglect3259 or criticisms,3260 deities could also plot their deaths.3261 Greeks could complain about the injustice of their deities» decrees;3262 with an entire pantheon, one could pit some deities against others (as in the Trojan War)3263 in ways that would have been unthinkable to monotheists. Mortals could also threaten them with unbelief if they failed to act.3264 Many Greek and Roman thinkers had become revolted by the literal sense of the old myths.3265

Many Greek thinkers articulated a morally purer notion of the divine.3266 Most Platonists adopted Aristotlés idea of God «as a mind thinking itself,» though in a later period they returned to the early Platonic notion of a first principle higher than mind.3267 The early Stoic view of God bordered on pantheism, identified with the universal reason, the pervasive active principle in the universe acting on passive matter.3268 Contemporary Stoics, however, accommodated the notion of a personal deity against their earlier pantheism.3269 Thus they could speak of God as Zeus or a personal equivalent of Nature;3270 even though gods and people might function as distinct entities, all deities except Zeus would be resolved into the primeval fire. Although generally still polytheistic, Greeks in general had no problems depicting a supreme god as simply «God.»3271 Some also praised the Jewish people for rejecting Egyptian images of beasts (also rejected by Greeks) and preferring τό θείον.3272

Some Jewish writers, especially those who, like Philo, were influenced by Greek thought, could use «god» loosely as well as for the supreme deity. But even when writers like Philo (following Exod 7:1) call Moses a «god,»3273 Moses remains distinct from the supreme, eternal God to be worshiped,3274 for whom the title is normally reserved.3275 Further, Philo has a text (Exod 7:1) that allows him to accommodate some Hellenistic conceptions of heroes in an apologetically useful manner. Finally, for all the associations of Moses with the divine in Philo, the language comes short of Johns language for Jesus.3276 Jesus appears as God s agent in the Fourth Gospel, but not just like Moses as God’s chief agent; Jesus is one greater than Moses (1:17), namely the Word itself (1:14). In John’s claim, Jesus is therefore not merely the «ultimate prophet.» «God» in the third line (1:1c) hardly signifies something dramatically different from what the term signified in the two lines that preceded it (l:lab), even if one presses a distinction on the basis of the anarthrous construction; like other early Christians (e.g., Mark 12:29; 1Tim 1:17), John acknowledges only one God (e.g., John 5:44; 17:3).

Many commentators doubt that the anarthrous construction signifies anything theologically at al1. It certainly cannot connote «a god,» as in «one among many,» given Jesus» unique titles, role, and relationship with the Father later in the Gospe1.3277 Nor should it mean «divine» in a weaker sense distinct from Gods own divine nature, for example, in the sense in which Philo can apply it to Moses.3278 Had John meant merely «divine» in a more general sense, the common but more ambiguous expression τό θείον was already available;3279 thus, for example, Philo repeatedly refers to the divine Word (θείος λόγος)3280 and Aristeas refers to «the divine law» (του θείου νόμου).3281

The anarthrous construction cannot be pressed to produce the weaker sense of merely «divine» in a sense distinct from the character of the Father’s deity. In one study of about 250 definite predicative nominatives in the NT, 90 percent were articular when following the verb, but a comparable 87 percent were anarthrous when before the verb, as here.3282 Grammatically, one would thus expect John’s predicate nominative «θεός» to be anarthrous, regardless of the point he was making. Further, John omits the article for God the Father elsewhere in the Gospel, even elsewhere in the chapter (e.g., 1:6, 12, 13, 18).3283 The same pattern of inconsistent usage appears in early patristic texts,3284 and apparently Greek literature in genera1.3285 And in a context where absolute identification with the Father would be less of a danger, John does not balk at using the articular form to call Jesus ό θεός (20:28).3286

Still, the nuance must be slightly different from «God» elsewhere in this verse, given the distinction between God and the Logos in the second line; John indeed spends much of the rest of his Gospel clarifying the ambiguous distinction between God and the Logos promulgated in the lines of this first verse. (Philo, who distinguishes the Logos from God,3287 once makes a point that God’s eldest Logos is θεός–anarthrous–whereas God himself is ό θεός–articular;3288 thus Philo may make a distinction analogous to John’s here.3289 In John’s case, however, the distinction is clearer from context than from grammar, as noted above; and John’s Logos is more likely eternal, and certainly personal, than Philós.)

Grammar permits us to translate θεός in 1as either «God» or «divine.» Regarding Jesus as merely «divine» but not deity violates the context; identifying him with the Father does the same. For this reason, John might thus have avoided the article even had grammatical convention not suggested it;3290 as a nineteenth-century exegete argued, an articular θεός would have distorted the sense of the passage, «for then there would be an assertion of the entire identity of the Logos and of God, while the writer is in the very act of bringing to view some distinction between them.»3291

Provided we allow the immediately preceding uses of «God» (and analogous identifications throughout the Gospel) to define the sense of the Logos’s deity,3292 one might wish to translate the predicate nominative adjectivally as «divine,» to distinguish the divine Word from the God with whom the Word coexisted in the beginning. It is with just such grammatical and contextual complexities that ante-Nicene and early post-Nicene Christianity was forced to grapple. An early twentieth-century commentator, observing that John’s language makes Jesus partaker of the divine essence yet not identical with «the whole Godhead… is just the problem which the doctrine of the Trinity seeks to solve.»3293

Scholars from across the contemporary theological spectrum recognize that, although Father and Son are distinct in this text, they share deity in the same way;3294 thus some translate: «the Word had the same nature as God,»3295 or much less ambiguously (though still not quite precisely) «What God was, the Word was.»3296 That is perhaps the closest English translation by which one may hope to catch John’s nuance: fully deity but not the Father. That many sectors of Judaism had already stretched monotheism to accommodate a divine agent distinct from the Father made John’s apologetic task easier, even if he stretched the divine agent idea farther than most of his contemporaries (occasionally excepting Philo).

The Word and Creation (1:3)

John’s Logos, like Wisdom/Torah, is God’s agent of creation, a role that may also prefigure his work in the new creation. Before examining parallels between the Johannine Logos and Jewish tradition’s Wisdom/Torah, we must survey some of the various backgrounds that have been proposed for the creative Logos of 1:3.

1. Proposed Greek Parallels

Scholars who view John s purpose as antignostic could find plenty of antignosticism in 1:3; in contrast to gnostic beliefs, Christ alone is the mediator of creation in John. In Gnosticism, emanations from the primal Aeon formed the evil material world;3297 the creator was generally the Demiurge, a power far removed from the original deity.3298 Were Mandaic literature not so late, one could even read the verse from an anti-Mandaic angle, noting later rabbinic polemic against the idea of Adam as a divine agent in creation, a tenet of later Mandaism.3299 Yet creation through mediation was hardly limited to gnostic sources; in Greek texts a supreme deity could create other deities to assist in creation.3300 Further, Jewish circles were familiar with the idea of mediation in creation, which appears in Philo;3301 polemic against it appears in rabbinic3302 and other3303 sources about angelic involvement in creation. Further, John’s language does not imply polemic against such a view as Col 1does; we may observe John’s lack of polemic against a gnostic view of creation, for instance, in that he neither agrees with gnosticism that matter is evil3304 nor emphasizes the contrary Jewish position of the goodness of creation (1Tim 4:4), though he certainly accepts the latter position (cf. 1:14).3305 Still, for John, Jesus is the only mediator of creation, with or without polemic against other claims; Greeks well understood the divine instrumental function of διά with reference to creation.3306

Others have found here echoes of the Stoic doctrine of the Spermatikos (generative) Logos3307 or other Greek conceptions of the source of being.3308 One may even compare with Johns wording the anticreation language of Democritus («Nothing can come into being from that which is not» [μηδέν τε εκ του μη οντος γίνεσθαι])3309 and by Diogenes of Apollonius3310–though other Greek texts3311 and especially the Dead Sea Scrolls offer verbal parallels to John 1no less striking («apart from his counsel [מבלעזיו] nothing is performed»;3312 «all things come to be through Your will that are»;3313 «apart from Your will nothing is performed»;3314 «from God were all things made»3315). Although Johns emphasis is christological rather than cosmological, which rules out a polemic against anticreationists here (contrast 2Pet 3:4–6),3316 his cosmology, like that of the OT and much contemporary Jewish tradition, conflicted with the idea of an uncreated, imperishable universe.3317

More relevant among Greek cosmogenies, however, is the Platonic view of a creator (δημιουργός) building the material universe according to the ideal pattern perceptible by reason.3318 In contrast to much earlier Platonic thought, some middle Platonist contemporaries of John were beginning to take the nature of creation in Platós Timaeus literally,3319 asserting that Soul shaped matter.3320 Thus, as Plutarch summarizes Plato, God, matter, and form constituted the first principles, matter being «the least ordered of substances,» form (ιδέα) being «the most beautiful of patterns» (παραδει γμάτων), «and God the best of causes.»3321 A later neoplatonist like Plotinus could declare that the world of intellect formed the universe, which is now held together by the Logos.3322 Middle Platonism’s contribution to the Fourth Gospel is at most indirect, but might be acknowledged by way of Jewish philosophers like Philo, for whom the doctrine of God’s pattern in creation is paramount. For Philo, too, God used the world of intellect as a pattern for the rest of the world.3323 Some philosophers extrapolated from creation to the existence or nature of the creator, an apologetic followed by some early Christian writers (cf. Rom 1:19–20).3324 Such concerns are, however, beyond John’s purview; it is not a creator’s existence that generates controversy among his audience but the creator’s identification with Jesus.

2. Jewish Views of Creation

Greeks were divided as to whether matter had always existed3325 or whether visible things were formed from visible3326 or invisible things;3327 Jewish writers generally followed the latter view, that God had created.3328 Although some Jewish writers maintained the view of a creation ex nihilo3329 (many contend that this view surfaces only after the Fourth Gospel),3330 others interpreted Gen 1 in light of the typical pagan conception of a primeval chaos out of which God ordered the universe.3331 All agreed, however, that God was «the One who made the world,»3332 usually including the primeval matter he later reformed. Samaritan liturgy came to emphasize creation heavily,3333 and some Jewish teachers sought mystic insight into the way God created the world.3334 Occasional parallels indicate that at least some later rabbinic traditions preserve reminiscences of earlier speculations that were more widespread.3335 Philo, who, like later Platonists, synthesized older Platonism and elements of the more popular Stoic thought,3336 argued that God formed the universe (starting with the incorporeal world)3337 through his Logos,3338 through which he also sustains it.3339 Such a view comported acceptably with the common Greek philosophical ideas that God created through matter and form or that reason ordered existing matter (see comment above). In Philo, Logos is not only divine Reason structuring matter, but as in some middle Platonic thought a determinate pattern which is God’s image.3340 Thus God made the world as a copy of his divine image, the Logos being his archetypal seal imprinted on them.3341 Like John, who connects the creative Logos with God’s written Logos,3342 Philo connects the creative Logos with the wisdom of Reason by which he draws the perfect (τέλειος) man, the wise man, to himself.3343 Philo also connects creation with the law of Moses, and by arguing that the universe was created in harmony with Moses» law and that those who obey the law obey Nature,3344 he explicitly identifies Moses» law with the universal natural law that phi-losophers conceived as pervading the cosmos.3345 Unlike John, Philo was at home in the cultural sphere of philosophically educated hellenized Judaism; but both reflect in many respects a common milieu.3346

But Philo was not the first Jewish writer to suggest that God started from a pattern in creation. As early as the second century B.C.E., Jewish writers indicated God’s prior design for creation rooted in knowledge or wisdom.3347 While expounding on God alone being able to justify, Qumran’s Manual of Discipline declares that «All things come to be by his knowledge [בדעתו] and he sustains [or, establishes] them by his plan3348 [כםחשכח]». Later rabbis applied the Platonic image to Torah: God the builder used Torah as his architect, consulting Torah with its plans and diagrams.3349 Some Tannaim felt that God stamped each person with the seal of Adam (m. Sank. 4:5). Further, Jewish writers fully exploited OT passages which already taught that God created the world by speaking (Gen 1; Ps 33) or through his Wisdom (Prov 8).

3.

Creation by Word, Wisdom, Torah

God spoke the world into being in Gen 1, and John’s contemporaries continued to celebrate this OT pattern. Both early nonrabbinic writers3350 and Tannaim3351 reported that God created the world «only by an act of speech»; indeed, one Tannaitic title for God was «the One who spoke and summoned the universe into being.»3352 Although «this utterance did not receive the connotation of «Logos» in the Philonic sense» and «was not hyposta-tized,»3353 many have found the background for John’s creative Logos wholly or partly in the creative word of Genesis, whose «beginning» John 1evokes.3354

Texts connect creation by Gods word with creation by his wisdom3355 or Torah. In one exegetically ingenious early tradition, God’s ten words on which the world was founded («And he said» occurs ten times in a portion of the creation narrative)3356 represent the Ten Commandments.3357 Building on Prov 8, it was only natural that subsequent texts should attribute creation to divine Wisdom, for example, in Wis 7(Wisdom as the τεχνίτης of all things; cf. Heb 11:10).3358 And if to Wisdom, then naturally also to Torah, especially among those who became Torah’s most prominent expositors.3359 Not only was the world created by Word, Wisdom, and Torah, it was sustained by Word,3360 Wisdom,3361 and Torah.3362 Later rabbis interpreted this in a very practical sense, rather than simply theoretically: the world was sustained through the practice of Torah,3363 hence in some sense through the righteous.3364 Thus as sages could declare that the world was created for Torah,3365 some could also declare it was created for the righteous3366 or Israel3367 who would practice Torah; some texts claimed that it was created for humanity rather than the reverse.3368 (Greco-Roman thought also speculated on the purpose of creation, whether for gods and mortals,3369 for humanity,3370 or clearly not for that purpose.)3371

John here affirms what the earliest suspected pre-Pauline creeds had affirmed in the first two decades of the church’s existence: Jesus is the Father’s agent in creation (1Cor 8:5–6; Col 1:15–17).3372 Like most of those creeds (see above), John identifies Jesus with incarnate Wisdom. (See the introductory section to the prologue, above, for a more detailed discussion of various proposed backgrounds for the Logos.) «All things» (πάντα)3373 emphasizes Jesus» priority, hence supremacy, over whatever is created (3:35; 13:3; cf. Rev 4:11), hence over all humanity (17:2), whether or not humanity acknowledged it (1:10–11).

The Word as Life and Light (1:4–5)

Commentators dispute the proper syntactical sense of ό γέγονεν at the end of 1:3. Should we read the phrase with the rest of v. 3, as in, «apart from him nothing came into being that has come into being; in him was life»?3374 Or should we read the phrase with v. 4, «apart from him nothing came into being; what came into being through him was life»?3375 Church fathers and later manuscripts that are punctuated suggest that those generations thought the latter view makes better sense of the Greek.3376 A somewhat parallel Semitic construction in the Manual of Discipline may, however, support the former reading;3377 one would not expect later Greco-Christian writers to recognize such a construction. (Other exegetical options have sought to circumvent these alternatives.)3378 Ultimately the syntax contributes less to our grasp of John’s sense than the context contributes; since John identifies «life» with «light» (1:4; 8:12), and «light» contextually refers to Christ (1:9–10), we must understand that on a functional level «life» is ultimately Jesus himself ( 11:25; 14:6; cf. 3:15; 5:24).

This verse introduces the light/darkness dualism of the rest of the Gospe1. Both light (1:4, 5, 7, 8, 9; 3:19, 20, 21; 5:35; 8:12; 9:5; 11:9, 10; 12:35, 36, 46) and day (9:4), darkness (1:5; 3:19; 8:12; 12:35,46) and night (9:4; 11:10) appear regularly throughout the Gospel, sometimes even with symbolic significance in the narratives (e.g., 3:2; 13:30; 19:39; perhaps 6:19).3379 The verse also introduces the theme of life, which appears some thirty-five times in the Gospe1.3380

This passage creates a literary chain (life, life, light, light, darkness, and darkness) called a sorites. Such a pattern also appears in Wis 6:17–20,3381 though it is not limited to wisdom texts.3382 For John, «life» and «light» are not simply abstractions: the Life raises Lazarus (11:25,43–44); the Light gives light to blind eyes (9:5–7); the Word becomes flesh (1:14).

1. Uses of Light Imagery

Light/darkness dualism figures heavily in gnosticism,3383 but is no less pervasive in earlier sources.3384 Philosophers spoke of true knowledge as providing light;3385 Philo regarded God as light and the archetype of all other kinds of light.3386 Writers commonly applied to good and evil the contrast between light and darkness.3387 One may also compare the vision of God in various texts.3388

A figurative use of light appears frequently in the OT3389 and in the non-Johannine Gospel tradition dependent on the OT.3390 A variety of Jewish sources employ darkness and light figuratively for evil and good respectively3391 or with reference to enlightenment in wisdom,3392 but it was the Dead Sea Scrolls which decisively moved NT scholars away from seeking a gnostic background for Johns «light/darkness» dualism.3393 Like John, the Dead Sea Scrolls also use «day» figuratively with «light,» and «night» with «darkness.»3394

Jewish teachers applied light and darkness imagery to a variety of specific occasions, all of which reflect a common appreciation for the goodness of light and a common disdain for the dangers of darkness (e.g., Job 18:5,18; 24:13,16; also in early Christian texts, e.g., Rom 2:19; 13:12; 2Cor 6:14; Eph 1:18; 4:18; 5:8, 11; 6:12; Col 1:13). The image applied to the primeval light before or from the creation,3395 a concept of possible relevance in the context of John 1:1–4.3396 (In Gen 1:3, the light came at Gods word, a tradition that continued to be developed.)3397 Because this light would be restored,3398 it also was connected with OT images of eschatological light and glory.3399 Other Jewish teachers regularly called particularly righteous sages or other persons lights (cf. John 5:35; Matt 5:14),3400 including Abraham,3401 Jacob,3402 Moses,3403 David,3404 and ultimately the Messiah;3405 the designation also could be applied to Israel,3406 Jerusalem,3407 the temple,3408 or to God himself.3409

But in the context of John’s prologue, it seems particularly relevant to observe that Jewish literature portrays both Wisdom3410 and Torah3411 as light (e.g., Ps 119:105, 130; Prov 6:23), as many commentators note.3412 Jesus as God’s Word, Wisdom, and Torah is light to enlighten God’s people, just as Torah was light offered to God’s people at Sinai. «Light of people» (1:4) means light for humanity (3:19), light for «the world» (9:5). Early Christians came to consistently apply the image of transition from darkness to light to a transfer from Satan’s realm to God’s at a believer’s conversion (Acts 26:18; 2Cor 4:6; Col 1:13; 1Pet 2:9; cf. Luke 1:79). In John’s prologue, this light relates to glory (1:14), as in Rev 18:1; 21:23.3413

2. Jesus as the Life

John often speaks of «life» (5:25, 26, 29; 6:33, 57, 63; 11:26; 14:6, 19; 17:3; 20:31; cf. 4:50; 6:44) or of «eternal life» (3:15, 16, 36; 4:14, 36; 5:21, 24, 39, 40; 6:27,40, 47, 48; 6:51, 53, 54, 58,68; 8:12; 10:10, 28; 11:25; 12:25, 50; 17:2);3414 although Judaism typically understood this as a future experience, John applies present tense verbs to it (3:16,36; 5:24; 6:47, 54; cf. 14:19), connecting it with faith (3:15, 16, 36; 6:27–29, 40, 47; 11:25, 26; 20:31) and following (8:12) in the present. Jesus» resurrection brings this life to believers (14:19; 20:22). Jesus embodies life because he embodies the truth and the way to God ( 14:6), roles which Judaism traditionally associated with Wisdom and Torah, God’s gracious instruction for the ways of life.3415

In numerous Jewish texts, Wisdom (cf. Prov 3:18; 13:14)3416 and Torah3417 provide or embody life, as modern scholars often observe.3418 Some Jewish texts mention the availability of both life and light in Torah.3419 The tradition of life in Torah probably derives from OT promises that if one obeyed the law one would live (Lev 18:5; Deut 30:6,19); although the texts themselves apply to long life on the land (Deut 4:1, 40; 5:33; 8:1; 30:16, 19–20) and many interpreted them accordingly,3420 it was natural to read them (as some later rabbis did) by means of qal vaomer (the «how much more» argument) as applying to the world to come.3421 Ultimately, God was Israel’s life (Deut 30:20), meaning in context, the one who would bless the people to live long in the land if they obeyed his commandments.

«Light» and «life» were natural images to use together. Greek texts regularly spoke of those who died as banished from the «light,»3422 recognizing the darkness of the shadowy netherworld of deceased souls.3423 One could also speak of a beloved person as «the light of our life.»3424 Hebrew poetry employed the same image conjoining «light» and «life,»3425 probably suggesting a shared eastern Mediterranean imagery of death and the netherworld. It is possible that the mention of «life» also continues the Genesis allusions (Gen 2:7; cf. John 20:22), like «the beginning» (1:1; Gen 1:1), creation (1:3; Gen 1:1); probably also God’s speech or word (1:1–18; Gen 1:3–6, 8–11, 14, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28–29) and light versus darkness (1:4–5; Gen 1:3–5).

3. Light Prevails over Darkness

Antithesis was a typical rhetorical form in both Greek and Jewish thought3426 and particularly relevant in a setting whose language implies a sort of moral dualism, as here.

Darkness appears as a negative symbol in most ancient literature,3427 including later Jewish texts.3428 The struggle between light and darkness and their respective hosts is quite evident in the Dead Sea Scrolls; the current conflict between the two, darkness appearing to hold the upper hand in the world,3429 would be resolved in favor of the sons of light at the final battle.3430 As one early Christian writer declares, «Let not light be conquered by darkness, Nor let truth flee from falsehood.»3431

The language of John 1indicates some sort of conflict between light and darkness, but the nature of the conflict is disputed. Does κατέλαβεν mean that darkness could not «apprehend» the light intellectually (so Cyril of Alexandria),3432 that darkness did not accept the light,3433 or that darkness could not «conquer» the light (Origen and most Greek Fathers)?3434 More than likely John, whose skill in wordplays appears throughout his Gospel, has introduced a wordplay here: darkness could not «apprehend» or «overtake» the light, whether by comprehending it (grasping with the mind) or by overcoming it (grasping with the hand).3435 (Playing on different senses of a term [or different terms spelled the same way] was a rhetorical device that some rhetoricians called traductio.)3436 Johns language may adapt similar language (though lacking this wordplay) in Wis 7:30, where evil cannot overpower Wisdom even though night overtakes day.3437 To the extent that the verb tense indicates a specific historical application beyond its general application to history, the past action probably summarizes the whole of Jesus» incarnate ministry;3438 the darkness thus implies Jesus» opposition among «the Jews» (cf. 1:11) and in the «world» in general which they represent.3439 One will not be «overcome» by darknes if one walks in the light (12:35), which penetrates darkness and exposes what is in that darkness (cf. Eph 5:13).

John Only a Witness (1:6–8)

The prologue is emphatic in its contrast between John and Jesus, as between creation and creator: the world was made (έγένετο) «through him» (Jesus) in 1:3. When the prologue declares that «through him» (John) all might believe (in Jesus) in 1:6, it notes that he came (έγένετο) for that purpose. In our introduction to the prologue, we observed that most of the prologue could constitute a hymn in three equal sections of twelve lines, if the lines about John were excluded. Most reconstructions of the original form of the prologue that exclude any part of it exclude the lines about John. Whether or not the prologue was written as a seamless whole, it is likely that the material about John (whom we shall sometimes call «the Baptist,» to distinguish him from the author to whom the Gospel is traditionally attributed) was present in the prologue from the time it became part of the Fourth Gospe1. (The lines about John may in part be woven into the rest of the prologue to connect it with the historical ministry of Jesus beginning in 1:19.3440 John, like Mark and some examples of the apostolic preaching in Acts, starts the gospel narrative with the Baptist.)3441

In a prologue which features the cosmic and préexistent Christ, lines about the Baptist seem hopelessly out of place to modern readers. The question we must thus ask is the function the Baptist material serves for John’s implied readers, the first community he was addressing. Two theories commend the most attention: the author contrasts the prophet John with the supreme Lord because some contemporaries were exalting John inappropriately; or the author uses John to serve a broader symbolic function (like the function that many attribute to the beloved disciple), namely, the importance of a witness. Both theories merit attention and both may be correct; the acceptance of either does not logically exclude the possibility of the other.

1. Polemic against a Baptist Sect

Writers in the early twentieth century advanced the thesis that the Fourth Gospel’s portrayal of John the Baptist represented Johannine polemic against the Baptist’s followers.3442 Reitzenstein and his followers, like Bultmann, accepted medieval claims of the Mandean sect to have grown directly from a movement founded by John the Baptist. Because the Mandeans were both anti-Christian and anti-Jewish, Reitzenstein doubted that their source was Christian or Jewish, and regarded their source of traditions later related to Christianity as deriving from the Baptist.3443 Such an application of the criterion of dissimilarity is unwarranted, however, for several reasons: first, many gnostic sects were anti-orthodox Christian or anti-Jewish yet sprang from orthodox Christian or Jewish roots.

Second, the Baptist’s own traditions would hardly be anti-Jewish; and if the character of the traditions could be modified after John’s time to yield anti-Judaism, why could they not have also originated in a later period? Third, all evidence for Mandean belief is too late to be of value; like supposed evidence in the Slavonic Josephus, it is medieva1.3444 If we recognize Jewish or orthodox Christian roots in anti-Jewish and anti-orthodox gnostic texts as early as the second century, how much more should we reject Reitzenstein’s suggestion of Mandean doctrinés independence based on its anti-Christian character? Bultmann thinks that the Fourth Gospel has christianized material originally applied to John the Baptist by adding 1:6–8, 15, and possibly 1:17;3445 but this postulates that followers of the Baptist had ideas for which we lack a shred of first-century evidence, and against which in fact is any evidence we do have (such as Acts 19:3–5).

Still, the text suggests an intentional contrast between Jesus and John, and a polemical agenda is difficult to dismiss. Other texts in the Fourth Gospel reinforce this impression. The Baptist waxes eloquent in 3:27–36 concerning Jesus» obvious superiority; cf. also 1:15, 24–27, 29–34; 4:1; 5:36; 10:41. (Some see in such texts a sign of positive relations between John’s community and the Baptist sect,3446 but one wonders how positively Johannine Christians would view a sect that they considered to have defective Christology and thus soteriology; cf. 14:6.) One may ask why the Baptist, as distinct from other characters, should need to be so self-effacing. If one responds that it is merely because he appears to be the only unambiguously positive witness in the Gospel, we may point to the beloved disciple and ask why he is not similarly self-effacing. It is reasonable to suppose that our author was concerned about John’s reputation vis-â-vis that of the Lord. Further, in contrast to the Synoptics, where the Baptist’s ministry paves the way for that of Jesus but the ministries overlap little, the Fourth Gospel overlaps the period of the two ministries (3:23–24).3447 Conflicts with followers of the Baptist could stand behind this difference, whether the Synoptics minimized the overlap or (more likely) John emphasized it, or both.3448 More important, Painter has demonstrated the polemical intention of 1:6–8 by contrasting its various assertions with the prologués much greater confessions of Jesus.3449

The later Mandeans were clearly not the only sect that appropriated the Baptist as a founder; Acts 19attests Ephesian disciples of John still unacquainted with the full teachings of the Jesus movement, who apparently emigrated from Palestine before Jesus» resurrection and settled in the region of John’s probable provenance.3450 Further, a polemic against John the Baptist appears in the Pseudo-Clementines (e.g., 2.17), which affirm both Jesus» superiority to the Baptist and Peter’s superiority over Pau1.3451 The Fourth Gospel, however, is nearly a century earlier than our earliest extant documents claiming the Baptist’s messiahship; do we place more weight on Acts 19’s reference to the Baptist’s disciples than the text can bear?3452

Yet despite the generally positive treatment of the Baptist, his exalted abasement is part of a larger polemic. His positive water ritual is inferior to Jesus» baptism in 1:26, 33, but this contrast represents part of a much more thoroughgoing contrast between Jewish purification and water rituals on the one hand and Jesus» purification on the other. Followers of the Baptist are not those who deify John; like adherents of other purification rituals, however (Jews, ch. 2; Samaritans, ch. 4), they may diminish the role of Jesus.3453 This suggestion would allow the Baptist polemic to function merely as a subsidiary issue in the overall conflict with synagogue authorities many have postulated (see introduction).

An examination of other Johannine literature, particularly the reports implying current situations in Revelation’s letters to the seven churches, allows us to reconstruct a possible Sitz im Leben for the polemic reducing John’s status as compared with that of Jesus. If the Johannine Epistles reflect a stage in the community’s development not far advanced beyond that reflected in our present form of the Gospel, some charismatics may have found reason to appeal to a lesser Christology than that to which the Johannine charismatics held. These false prophets probably advocated compromise with the synagogue or (more likely) the imperial cult to avoid Roman harrassment and to fit in with civic life (1 John 4:1; cf. the idolatry of 5:21; cf. the prophets of Rev 2:14, 20).3454 That they nicknamed their own prophetic mentors «Balaam» or «Jezebel» is unlikely;3455 they might have sought a figure respected by both the early Christian and the broader Jewish communities. John the Baptist would suggest a strong role model for them–a prophet who shared their pneumatology and perhaps respect for Christ as traditional Christians did, but allegiance to whom would not demand the high Johannine Christology accepted by the Johannine community, whose exclusivism functioned as an affront to the synagogue community.

The author encourages his readers by responding that prophets such as John functioned as witnesses to Christs role, as should all true possessors of the Holy Spirit. If they considered themselves followers of the Baptist sect that may have existed in Asian cities such as Ephesus (Acts 19:3), Revelation calls them instead followers of the evil prophet Balaam, who led Israel astray to practice idolatry (a term the Johannine community might even apply to an inadequate Christology; cf. 1 John 5:21)3456 and fornication (which may apply to spiritual harlotry in Rev 2:14,20–21).3457 If the false prophets used the Baptist as a model, our author responds by viewing them as a subsidiary part of Judaism and its old purifications. The true Spirit baptism that John proclaimed belongs to Jesus and his followers; the true Baptist pointed to Jesus as Gods agent, to the true Spirit baptism, and to Jesus as the divine bestower of the Spirit. That our author directs against possible Baptist secessionists the same water motif polemic he employs against the synagogue suggests that in his eyes the faith of the Baptist’s adherents was little beyond that of the synagogue: inadequate.

2. John as a Witness

John was «not the light,» but a witness for the light (1:8; cf. 5:35). As in the rest of the Gospel, John here functions primarily or solely as a witness to Jesus (1:31; 3:28–30; 5:33)3458–a theme in the Fourth Gospel that extends far beyond whatever significance the author attaches to its particular application to the Baptist. The writer may thus use the Baptist to introduce his theme of witness;3459 the Word is the ultimate truth for all of human history, but is made known through witnesses, of which John the Baptist was one historical example. John the Baptist thus functions in the Fourth Gospel «as the prototype of Jesus» disciples,»3460 or as Dodd puts it, «the evangelist is claiming the Baptist as the first Christian confessor,» in contrast to the view represented in the Synoptic Gospels that he was not «in the Kingdom of God.»»3461

That the Fourth Gospel’s portrayal of the Baptist serves the Gospel’s agenda does not mean that the Baptist historically never testified to Jesus. But that Josephus does not mention such a component of the Baptist’s ministry is hardly surprising, since Josephus regularly plays down messianic ideology or casts messianic figures in a negative light.3462 Indeed, all our sources emphasize only those aspects of the Baptist’s ministry most useful to their presentation; Josephus tones down the Synoptic picture of John the prophet of eschatological judgment (as he tones down that aspect of the Essenes), essentially reducing him «to a popular moral philosopher in the Greco-Roman mode, with a slight hint of a neo-Pythagorean performing ritual lustrations.»3463 Probably without Johns polemic, the Synoptics also indicate that the Baptist testified to Jesus. But the Fourth Gospel casts John in this role so thoroughly that one suspects it has reason to do so.

Given the rejection of their faith by synagogue leaders whom they had respected, members of the Johannine community must have welcomed the Fourth Gospel’s provision of witnesses testifying to the truth of their Lord;3464 the motif recurs throughout the Gospe1.3465 «Witness» was especially a legal term,3466 but the term’s figurative extension naturally led to a more general usage.3467 In the LXX the term indicates an appeal to objective evidence,3468 and frequently appears in lawcourt or controversy imagery.3469 Personal testimony implied firsthand knowledge (usually historical3470 but occasionally revelatory).3471 Against some commentators,3472 John’s usage may retain some legal associations,3473 especially if, as many contend, the whole Gospel is viewed as a trial narrative.3474 As Painter concludes, «The World had Jesus on trial, but was unable to produce a valid witness. Jesus» witnesses not only cleared him of all charges; their evidence brought the world under judgement.»3475 In some early Jewish texts prophets also appear as «witnesses» (cf. Acts 10:43; 1Pet 1:11–12).3476

Here John came so «all» might believe through him; John s mission as depicted elsewhere limits the force of this language; the «all» in a testimony to «all» could be limited by context (3:26).3477 Jesus is for «all» (1:9; cf. 5:23,28; 11:48; 12:19), and his witness must likewise impact all (13:35). John was «sent» from God (1:6),3478 fitting the shaliach theme of the Gospel (see introduction), but also reflecting the tradition that he fulfilled (Mal 3:1; see Luke 7:27).

Long before the advent of the current emphasis on literary criticism, Karl Barth noted that the verses about the Baptist (1:6–8,15) which intrude so noticeably on the rest of the prologue are there for a purpose. By standing out from the rest of the prologue,3479 he proposed, they draw our attention to the issue, «the problem of the relation between revelation and the witness to revelation.»3480 The literary purpose of beginning the Gospel with a witness, John (1:6–8, 15, 19–51), and closing with another witness (whom tradition also calls John, 19:35; 21:24), seems to be to underline the importance of witness for the Johannine community. If God was invisible till Jesus revealed him (1:18), he and Jesus would now remain invisible apart from the believing community modeling in their lives the character of Jesus (1 John 4:12; John 13:35; 17:21–23).

The World Rejects the Light (1:9–11)

The light could overcome darkness, and a witness was provided so people could believe the light. When the light came to them, however, «the world» as a whole rejected the light; even Christ’s own people as a whole rejected him. The remnant who did embrace him, however, would be endued with the light’s character, so they, too, might testify of the light (cf. 1:12–14).

1. The True Light Enlightens Everyone (1:9)

In contrast to John (1:8), who was merely a «lamp» (5:35), Jesus was the true light itself (1:9). In this Gospel, adjectives signifying genuineness can apply to Jesus» followers (1:47; 8:31; cf. 1 John 2:5), but most often apply to Jesus (5:31; 6:32, 55; 7:18; 8:14; 15:1; cf. 7:26; Rev 3:7) or the Father (3:33; 7:28). In a pagan environment with pluralistic options, designating God as the «true» God (17:3; 1 John 5:20; 1 Thess 1:9) made sense; when contrasting Jesus with lesser alternatives in a Jewish context–here John the Baptist–the designation remained valuable.

Philosophers applied «enlightenment» to the revealing of philosophical truth;3481 Jewish people applied it to the gift of Torah;3482 and early Christians applied it especially to the reception of the gospe1.3483 But does John refer here to universal availability to those to whom witness is offered, or to a portion of the Logos revealed to all people with or without the gospel testimony?3484 In contrast to the purpose of Johns testimony stated in 1:7, Jesus» role in 1does not limit the sense of «every person»; unlike John, Jesus is the light and the Word itself (1:8–9).3485 Yet «every person» could mean «any person,» indicating universal availability in the relevant cases;3486 given the variation of usage for such common terms, lexical meanings cannot decide the sense of this verse.

Our answer to the question of the extent and nature of Jesus» enlightenment of humanity may depend in part on what we do with «coming into the world» at the end of v. 9. The phrase «come into the world» can suggest either birth (of people)3487 or other kinds of origination,3488 but indicates a historical moment rather than an eternal process (cf. 1 John 4:1–6).

Grammatically, the masculine or neuter singular participle can refer either to the light or to «every person.» If the participle applies to «every person,»3489 it could be meant to make «every person» more emphatic, underlining its absolute universality. In favor of this reading is the natural flow of the syntax from an immediate antecedent. On this reading, we might at least consider Glasson’s comparison of a rabbinic tradition in which God teaches the law to children in the womb.3490 But Greek antecedents are decided by form more than by proximity, and, as noted above, form is indecisive here. John’s usage is ultimately determinative; normally he speaks of Christ coming into the world, not of others.3491 As opposed to the later and rarer picture of prenatal Torah study, a much more widespread and early Jewish tradition may parallel John’s picture of the Light coming into the world enlightening all: God making available the light of his Word to all nations at a specific historical point at Mount Sinai.3492