Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese Mahāyāna school of Buddhism that strongly emphasizes dhyāna, the meditative training of awareness and equanimity. This practice, according to Zen proponents, gives insight into one’s true nature, or the emptiness of inherent existence, which opens the way to a liberated way of living.

Kamakura Daibutsu of Kōtoku-in temple in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

| Japanese Zen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 禅 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 禪 | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thiền | ||||||

| Chữ Hán | 禪 | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 선 | ||||||

| Hanja | 禪 | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 禅 | ||||||

|

- See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan

HistoryEdit

OriginsEdit

According to tradition, Zen originated in India, when Gautama Buddha held up a flower and Mahākāśyapa smiled. With this smile he showed that he had understood the wordless essence of the dharma. This way the dharma was transmitted to Mahākāśyapa, the second patriarch of Zen.[1]

The term Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (chán), an abbreviation of 禪那 (chánnà), which is a Chinese transliteration of the Sanskrit word of dhyāna («meditation»). Buddhism was introduced from India to China in the first century AD. According to tradition, Chan was introduced around 500 C.E. by Bodhidharma, an Indian monk teaching dhyāna. He was the 28th Indian patriarch of Zen and the first Chinese patriarch.[1]

Early Japanese ZenEdit

Zen was first introduced into Japan as early as 653-656 C.E. in the Asuka period (538–710 C.E.), at the time when the set of Zen monastic regulations was still nonexistent and Chan masters were willing to instruct anyone regardless of buddhist ordination. Dōshō (道昭, 629–700 C.E.) went over to China in 653 C.E., where he learned Chan from the famed Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (玄奘, 602 – 664 C.E.), and he studied more fully with a disciple of the second Chinese patriarch, Huike (慧可, 487–593 C.E.) . After returning home, Dōshō established the Hossō school, basing it on Yogācāra philosophy and built a Meditation Hall for the purpose of practising Zen in the Gangō-ji in Nara. In the Nara period (710 to 794 C.E.), the Chan master, Dao-xuan (道璿, 702-760 C.E.), arrived in Japan, he taught meditation techniques to the monk Gyōhyō (行表, 720–797 C.E.), who in turn was to instruct Saichō (最澄, 767-822 C.E.), founder of the Japanese Tendai sect of Buddhism. Saicho visited Tang China in 804 C.E. as part of an official embassy sent by Emperor Kammu (桓武天皇, 781-806 C.E.). There he studied four branches of Buddhism including Chan and Tiantai, which he was, by that time, already familiar with.

The first attempt of establishing Zen as an independent doctrine was in 815, when the Chinese monk Yikong (義空) visited Japan as the representative of Chan’s Southern-school lineage, based on the teachings of the master Mazu Daoyi (馬祖道一, 709–788 C.E.), who was the mentor of Baizhang (百丈懐海, 720–814 C.E.), the supposed author of the initial set of Zen monastic regulations. Yikong arrived in 815 C.E. and tried unsuccessfully to transmit Zen systematically to the eastern nation. It is recorded in an inscription left at the famous Rashõmon gate protecting the southern entryway to Kyoto that, on leaving to return to China, Yikong said he was aware of the futility of his efforts due to hostility and opposition he experienced from the dominant Tendai Buddhist school. What existed of Zen in the Heian period (794-1185 C.E.) was incorporated into and subordinate to the Tendai tradition . The early phase of Japanese Zen has been labeled «syncretic» because Chan teachings and practices were initially combined with familiar Tendai and Shingon forms.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Kamakura (1185–1333 C.E.)Edit

Zen found difficulties in establishing itself as a separate school in Japan until the 12th century, largely because of opposition, influence, power and criticism by the Tendai school. During the Kamakura period (1185–1333 C.E.), Nōnin established the first independent Zen school on Japanese soil, known as the short-lived and disapproved Daruma school.[7][6] In 1189 Nōnin[8] sent two students to China, to meet with Cho-an Te-kuang (1121–1203 C.E.), and ask for the recognition of Nōnin as a Zen-master. This recognition was granted.[9]

In 1168 C.E., Eisai traveled to China, whereafter he studied Tendai for twenty years.[10] In 1187 C.E. he went to China again, and returned to establish a local branch of the Linji school, which is known in Japan as the Rinzai school.[11] Decades later, Nampo Jōmyō (南浦紹明) (1235–1308 C.E.) also studied Linji teachings in China before founding the Japanese Ōtōkan lineage, the most influential branch of Rinzai.

In 1215 C.E., Dōgen, a younger contemporary of Eisai’s, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Rujing. After his return, Dōgen established the Sōtō school, the Japanese branch of Caodong.[11]

Zen fit the way of life of the samurai: confronting death without fear, and acting in a spontaneous and intuitive way.[11]

During this period the Five Mountain System was established, which institutionalized an influential part of the Rinzai school. It consisted of the five most famous Zen temples of Kamakura: Kenchō-ji, Engaku-ji, Jufuku-ji, Jōmyō-ji and Jōchi-ji.[12]

Muromachi (or Ashikaga) (1336–1573 C.E.)Edit

During the Muromachi period the Rinzai school was the most successful of the schools, since it was favoured by the shōgun.

Gozan-systemEdit

In the beginning of the Muromachi period the Gozan system was fully worked out. The final version contained five temples of both Kyoto and Kamakura. A second tier of the system consisted of Ten Temples. This system was extended throughout Japan, effectively giving control to the central government, which administered this system.[13] The monks, often well educated and skilled, were employed by the shōgun for the governing of state affairs.[14]

| Gozan system | ||

| Kyoto | Kamakura | |

|---|---|---|

| First Rank | Tenryū-ji | Kenchō-ji |

| Second Rank | Shōkoku-ji | Engaku-ji |

| Third Rank | Kennin-ji | Jufuku-ji |

| Fourth Rank | Tōfuku-ji | Jōchi-ji |

| Fifth Rank | Manju-ji | Jōmyō-ji |

Rinka-monasteriesEdit

Not all Rinzai Zen organisations were under such strict state control. The Rinka monasteries, which were primarily located in rural areas rather than cities, had a greater degree of independence.[15] The O-to-kan lineage, that centered on Daitoku-ji, also had a greater degree of freedom. It was founded by Nampo Jomyo, Shuho Myocho, and Kanzan Egen.[16] A well-known teacher from Daitoku-ji was Ikkyū.[11]

Another Rinka lineage was the Hotto lineage, of which Bassui Tokushō is the best-known teacher.[17]

Azuchi-Momoyama (1573–1600 C.E.) and Edo (or Tokugawa) (1600–1868 C.E.)Edit

After a period of war Japan was re-united in the Azuchi–Momoyama period. This decreased the power of Buddhism, which had become a strong political and military force in Japan. Neo-Confucianism gained influence at the expense of Buddhism, which came under strict state control. Japan closed the gates to the rest of the world. The only traders to be allowed were Dutchmen admitted to the island of Dejima.[11] New doctrines and methods were not to be introduced, nor were new temples and schools. The only exception was the Ōbaku lineage, which was introduced in the 17th century during the Edo period by Ingen, a Chinese monk. Ingen had been a member of the Linji school, the Chinese equivalent of Rinzai, which had developed separately from the Japanese branch for hundreds of years. Thus, when Ingen journeyed to Japan following the fall of the Ming dynasty to the Manchu people, his teachings were seen as a separate school. The Ōbaku school was named after Mount Huangbo (黄檗山, Ōbaku-sān), which had been Ingen’s home in China.

Well-known Zen masters from this period are Bankei, Bashō and Hakuin.[11] Bankei Yōtaku (盤珪永琢?, 1622–1693 C.E.) became a classic example of a man driven by the «great doubt». Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉?, 1644 – November 28, 1694) became a great Zen poet. In the 18th century Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴?, 1686–1768) revived the Rinzai school. His influence was so immense that almost all contemporary Rinzai lineages are traced back to him.

Meiji Restoration (1868–1912 C.E.) and Imperial expansionism (1912–1945 C.E.)Edit

The Meiji period (1868–1912 C.E.) saw the Emperor’s power reinstated after a coup in 1868 C.E.. At that time Japan was forced to open to Western trade which brought influence and, eventually, a restructuring of all government and commercial structures to Western standards. Shinto became the officiated state religion and Buddhism was coerced to adapt to the new regime. The Buddhist establishment saw the Western world as a threat, but also as a challenge to stand up to.[18][19]

Buddhist institutions had a simple choice: adapt or perish. Rinzai and Soto Zen chose to adapt, trying to modernize Zen in accord with Western insights, while simultaneously maintaining a Japanese identity. This Japanese identity was being articulated in the Nihonjinron philosophy, the «Japanese uniqueness» theory. A broad range of subjects was taken as typical of Japanese culture. D.T. Suzuki contributed to the Nihonjinron-philosophy by taking Zen as the distinctive token of Asian spirituality, showing its unique character in the Japanese culture[20]

This resulted in support for the war activities of the Japanese imperial system by the Japanese Zen establishment—including the Sōtō sect, the major branches of Rinzai, and several renowned teachers. According to Sharf,

They became willing accomplices in the promulgation of the kokutai (national polity) ideology—the attempt to render Japan a culturally homogeneous and spiritually evolved nation politically unified under the divine rule of the emperor.[20]

War endeavours against Russia, China and finally during the Pacific War were supported by the Zen establishment.[19][21]

A notable work on this subject was Zen at War (1998) by Brian Victoria,[19] an American-born Sōtō priest. One of his assertions was that some Zen masters known for their post-war internationalism and promotion of «world peace» were open Japanese nationalists in the inter-war years.[web 1] Among them as an example Hakuun Yasutani, the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan School, even voiced antisemitic and nationalistic opinions after World War II. Only after international protests in the 1990s, following the publication of Victoria’s ‘Zen at war’, did the Sanbo Kyodan express apologies for this support[web 2] This involvement was not limited to the Zen schools, as all orthodox Japanese schools of Buddhism supported the militarist state. Victoria’s particular claims about D. T. Suzuki’s involvement in militarism have been much disputed by other scholars.

Criticisms of post-WWII ZenEdit

Some contemporary Japanese Zen teachers, such as Harada Daiun Sogaku and Shunryū Suzuki, have criticized Japanese Zen as being a formalized system of empty rituals in which very few Zen practitioners ever actually attained realization. They assert that almost all Japanese temples have become family businesses handed down from father to son, and the Zen priest’s function has largely been reduced to officiating at funerals, a practice sardonically referred to in Japan as sōshiki bukkyō (葬式仏教, funeral Buddhism).[citation needed] For example, the Sōtō school published statistics stating that 80 percent of laity visited temples only for reasons having to do with funerals and death.[22]

TeachingsEdit

Buddha-nature and sunyataEdit

Ensō (c. 2000) by Kanjuro Shibata XX. Some artists draw ensō with an opening in the circle, while others close the circle

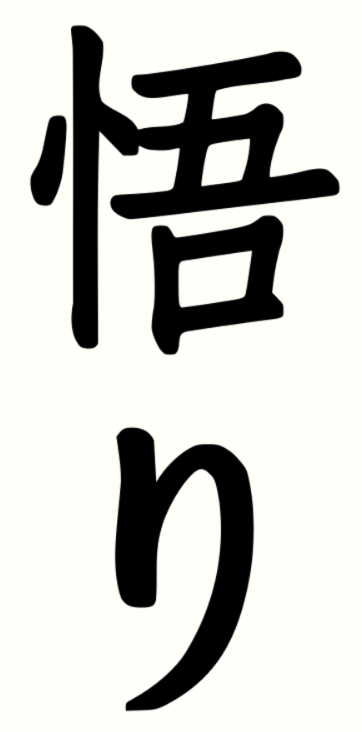

The Japanese term 悟り satori, made up of the kanji 悟 (pronounced wù in Mandarin and meaning «understand») and the hiragana syllable り ri.

Mahayana Buddhism teaches śūnyatā, «emptiness», which is also emphasized by Zen. But another important doctrine is the buddha-nature, the idea that all human beings have the possibility to awaken. All living creatures are supposed to have the Buddha-nature, but don’t realize this as long as they are not awakened. The doctrine of an essential nature can easily lead to the idea that there is an unchanging essential nature or reality behind the changing world of appearances.[23]

The difference and reconciliation of these two doctrines is the central theme of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.[23]

Kensho: seeing one’s true natureEdit

The primary goal of Rinzai Zen is kensho, seeing one’s true nature, and mujodo no taigen, expression of this insight in daily life.[24]

Seeing one’s true nature means seeing that there is no essential ‘I’ or ‘self’, that our true nature is empty.

Expression in daily life means that this is not only a contemplative insight, but that our lives are expressions of this selfless existence.[web 3]

Zen meditationEdit

Zen emphasizes zazen, meditation c.q. dhyana in a sitting position. In Soto, the emphasis is on shikantaza, ‘just sitting’, while Rinzai also uses koans to train the mind. In alternation with zazen, there is walking meditation, kinhin, in which one walks with full attention.

To facilitate insight, a Zen teacher can assign a kōan. This is a short anecdote, which seems irrational, but contains subtle references to the Buddhist teachings.[25] An example of a kōan is Joshu’s ‘Mu’:[26]

A monk asked: «Does a dog have buddha-nature?» Joshu responded: «Mu!»

Zen-meditation aims at «non-thinking,» in Japanese fu shiryō and hi shiryō. According to Zhu, the two terms negate two different cognitive functions both called manas in Yogacara, namely «intentionality»[27] or self-centered thinking,[28] and «discriminative thinking» (vikalpa).[27] The usage of two different terms for «non-thinking» points to a crucial difference between Sōtō and Rinzai in their interpretation of the negation of these two cognitive functions.[27] According to Rui, Rinzai Zen starts with hi shiryō, negating discriminative thinking, and culminates in fu shiryō, negating intentional or self-centered thinking; Sōtō starts with fu shiryō, which is displaced and absorbed by hi shiryō.[29][note 1]

Contemporary Zen organizationsEdit

The traditional institutional traditions (su) of Zen in contemporary Japan are Sōtō (曹洞), Rinzai (臨済), and Ōbaku (黃檗). Sōtō and Rinzai dominate, while Ōbaku is smaller. Besides these there are modern Zen organizations which have especially attracted Western lay followers, namely the Sanbo Kyodan and the FAS Society.

SōtōEdit

Sōtō emphasizes meditation and the inseparable nature of practice and insight. Its founder Dogen is still highly revered. Soto is characterized by its flexibility and openness. No commitment to study is expected and practice can be resumed voluntarily.

RinzaiEdit

Rinzai emphasizes kōan study and kensho. The Rinzai organisation includes fifteen subschools based on temple affiliation. The best known of these main temples are Myoshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Tofuku-ji. Rinzai is characterized by its stringent regiments of meditation through every second of life. Whether a practitioner is practicing seated meditation, walking meditation, working, or even out in public, meditation can be applied to each instance of a Rinzai student’s life.

ObakuEdit

Ōbaku is a small branch, which organizationally, is part of the Rinzai school.

Sanbo KyodanEdit

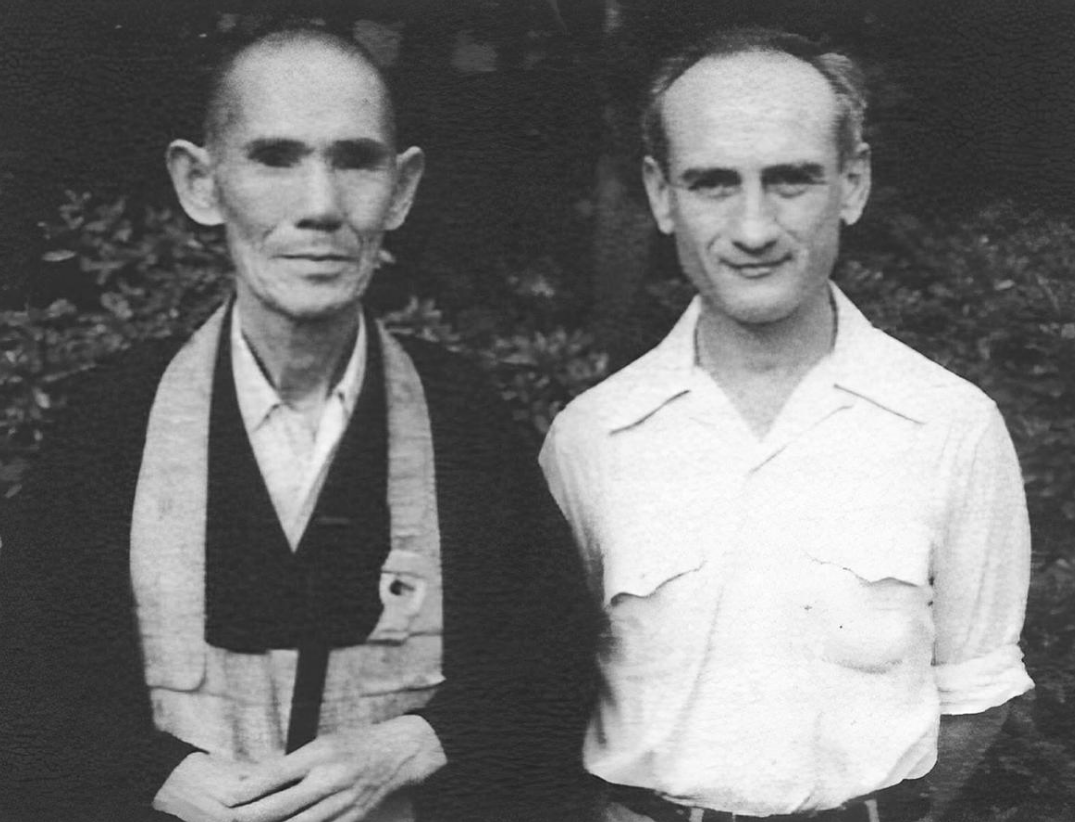

Haku’un Yasutani and Phillip Kapleau

The Sanbo Kyodan is a small Japanese school, established by Hakuun Yasutani, which has been very influential in the West. Well-known teachers from this school are Philip Kapleau and Taizan Maezumi. Maezumi’s influence stretches further through his dharma heirs, such as Joko Beck, Tetsugen Bernard Glassman, and especially Dennis Merzel, who has appointed more than a dozen dharma heirs.

FAS SocietyEdit

The FAS Society is a non-sectarian organization, founded by Shin’ichi Hisamatsu. Its aim is to modernize Zen and adapt it to the modern world. In Europe it is influential through such teachers as Jeff Shore and Ton Lathouwers.

Zen in the Western worldEdit

Early influencesEdit

Although it is difficult to trace when the West first became aware of Zen as a distinct form of Buddhism, the visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago during the World Parliament of Religions in 1893 is often pointed to as an event that enhanced its profile in the Western world. It was during the late 1950s and the early 1960s that the number of Westerners pursuing a serious interest in Zen, other than descendants of Asian immigrants, reached a significant level.

Eugen Herrigel’s book Zen in the Art of Archery[32] describing his training in the Zen-influenced martial art of Kyūdō, inspired many of the Western world’s early Zen practitioners. However, many scholars, such as Yamada Shoji, are quick to criticize this book.[33]

D.T. SuzukiEdit

The single most influential person for the spread of Zen Buddhism was D. T. Suzuki.[18][20] A lay student of Zen, he became acquainted with Western culture at a young age. He wrote many books on Zen which became widely read in the Western world, but he has been criticised for giving a one-sided and overly romanticized vision of Zen.[18][20][34]

Reginald Horace Blyth (1898–1964) was an Englishman who went to Japan in 1940 to further his study of Zen. He was interned during World War II and started writing in prison. While imprisoned he met Robert Aitken, who was later to become a roshi in the Sanbo Kyodan lineage. Blyth was tutor to the Crown Prince after the war. His greatest work is the 5-volume «Zen and Zen Classics», published in the 1960s. Here he discusses Zen themes from a philosophical standpoint, often in conjunction with Christian elements in a comparative spirit. His essays include «God, Buddha, and Buddhahood» and «Zen, Sin, and Death».

Beat ZenEdit

The British philosopher Alan Watts took a close interest in Zen Buddhism and wrote and lectured extensively on it during the 1950s. He understood Zen as a vehicle for a mystical transformation of consciousness, and also as a historical example of a non-Western, non-Christian way of life that had fostered both the practical and fine arts.

The Dharma Bums, a novel written by Jack Kerouac and published in 1959, gave its readers a look at how a fascination with Buddhism and Zen was being absorbed into the bohemian lifestyles of a small group of American youths, primarily on the West Coast. Beside the narrator, the main character in this novel was «Japhy Ryder», a thinly veiled depiction of Gary Snyder. The story was based on actual events taking place while Snyder prepared, in California, for the formal Zen studies that he would pursue in Japanese monasteries between 1956 and 1968.[35]

Christian ZenEdit

Thomas Merton (1915–1968) was a Catholic Trappist monk and priest.[web 4] Like his friend, the late D.T. Suzuki, Merton believed that there must be a little of Zen in all authentic creative and spiritual experience. The dialogue between Merton and Suzuki[36] explores the many congruencies of Christian mysticism and Zen.[37][38][non-primary source needed]

Father Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle

Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle (1898–1990) was a Jesuit who became a missionary in Japan in 1929. In 1956 he started to study Zen with Harada Daiun Sogaku. He was the superior of Heinrich Dumoulin, the well-known author on the history of Zen. Enomiya-lassalle introduced Westerners to Zen meditation.

Robert Kennedy (roshi), a Catholic Jesuit priest, professor, psychotherapist and Zen roshi in the White Plum lineage has written a number of books about what he labels as the benefits of Zen practice to Christianity. He was ordained a Catholic priest in Japan in 1965, and studied with Yamada Koun in Japan in the 1970s. He was installed as a Zen teacher of the White Plum Asanga lineage in 1991 and was given the title ‘Roshi’ in 1997.

In 1989, the Vatican released a document which states some Catholic appreciation of the use of Zen in Christian prayer. According to the text none of the methods proposed by non-Christian religions should be rejected out of hand simply because they are not Christian:

On the contrary, one can take from them what is useful so long as the Christian concept of prayer, its logic and requirements are never obscured.[web 5]

Zen and the art of…Edit

While Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert M. Pirsig, was a 1974 bestseller, it in fact has little to do with Zen as a religious practice, nor with motorcycle maintenance for that matter. Rather it deals with the notion of the metaphysics of «quality» from the point of view of the main character. Pirsig was attending the Minnesota Zen Center at the time of writing the book. He has stated that, despite its title, the book «should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice». Though it may not deal with orthodox Zen Buddhist practice, Pirsig’s book in fact deals with many of the more subtle facets of Zen living and Zen mentality without drawing attention to any religion or religious organization.

A number of contemporary authors have explored the relationship between Zen and a number of other disciplines, including parenting, teaching, and leadership. This typically involves the use of Zen stories to explain leadership strategies.[39]

ArtEdit

In Europe, the Expressionist and Dada movements in art tend to have much in common thematically with the study of kōans and actual Zen. The early French surrealist René Daumal translated D.T. Suzuki as well as Sanskrit Buddhist texts.

Western Zen lineages derived from JapanEdit

Over the last fifty years mainstream forms of Zen, led by teachers who trained in East Asia and their successors, have begun to take root in the West.

United StatesEdit

Sanbo KyodanEdit

In North America, the Zen lineages derived from the Sanbo Kyodan school are the most numerous. The Sanbo Kyodan is a Japan-based reformist Zen group, founded in 1954 by Yasutani Hakuun, which has had a significant influence on Zen in the West. Sanbo Kyodan Zen is based primarily on the Soto tradition, but also incorporates Rinzai-style kōan practice. Yasutani’s approach to Zen first became prominent in the English-speaking world through Philip Kapleau’s book The Three Pillars of Zen (1965), which was one of the first books to introduce Western audiences to Zen as a practice rather than simply a philosophy. Among the Zen groups in North America, Hawaii, Europe, and New Zealand which derive from Sanbo Kyodan are those associated with Kapleau, Robert Aitken, and John Tarrant.

The most widespread are the lineages founded by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi and the White Plum Asanga. Maezumi’s successors include Susan Myoyu Andersen, John Daido Loori, Chozen Bays, Tetsugen Bernard Glassman, Dennis Merzel, Nicolee Jikyo McMahon, Joan Hogetsu Hoeberichts, and Charlotte Joko Beck.

SotoEdit

Soto has gained prominence via Shunryu Suzuki, who established the San Francisco Zen Center. In 1967 the Center established Tassajara, the first Zen Monastery in America, in the mountains near Big Sur.

The Katagiri lineage, founded by Dainin Katagiri, has a significant presence in the Midwest. Note that both Taizan Maezumi and Dainin Katagiri served as priests at Zenshuji Soto Mission in the 1960s.

Taisen Deshimaru, a student of Kodo Sawaki, was a Soto Zen priest from Japan who taught in France. The International Zen Association, which he founded, remains influential. The American Zen Association, headquartered at the New Orleans Zen Temple, is one of the North American organizations practicing in the Deshimaru tradition.

Soyu Matsuoka established the Long Beach Zen Buddhist Temple and Zen Center in 1971, where he resided until his death in 1998. The Temple was headquarters to Zen centers in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Everett, Washington.

Matsuoka created several dharma heirs, three of whom are still alive and leading Zen teachers within the lineage: Hogaku ShoZen McGuire, Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston Sensei, and Kaiten John Dennis Govert.

Brad Warner is a Soto priest appointed by Gudo Wafu Nishijima. He is not a traditional Zen teacher, but is influential via his blogs on Zen.

RinzaiEdit

Rinzai gained prominence in the West via D.T. Suzuki and the lineage of Soen Nakagawa and his student Eido Shimano. Soen Nakagawa had personal ties to Yamada Koun, the dharma heir of Hakuun Yasutani, who founded the Sanbo Kyodan.[40] They established Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji in New York. In Europe there is Havredal Zendo established by a Dharma Heir of Eido Shimano, Egmund Sommer (Denko Mortensen).

Some of the more prominent Rinzai Zen centers in North America include Rinzai-ji founded by Kyozan Joshu Sasaki Roshi in California, Chozen-ji founded by Omori Sogen Roshi in Hawaii, Daiyuzenji founded by Dogen Hosokawa Roshi (a student of Omori Sogen Roshi) in Chicago, Illinois, and Chobo-Ji founded by Genki Takabayshi Roshi in Seattle, Washington.

United KingdomEdit

The lineage of Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi is represented in the UK by the White Plum Sangha UK.

Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey was founded as a sister monastery to Shasta Abbey in California by Master Reverend Jiyu Kennett Roshi. It has a number of dispersed priories and centres.[citation needed] Jiyu Kennett, an Englishwoman, was ordained as a priest and Zen master in Shoji-ji, one of the two main Soto Zen temples in Japan.[note 2] The Order is called the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives.[citation needed] There are several affiliated temples across the UK, including the Norwich Zen Buddhist Priory.[41]

Taisen Deshimaru Roshi’s lineage is known in the UK as IZAUK (International Zen Association UK).[citation needed]

The Zen Centre in London is connected to the Buddhist Society.

Zenways[42] is a Rinzai school organisation in South London. It is led by Daizan Roshi a British teacher who received Dharma transmission from Shinzan Miyamae Roshi.

The Western Chan Fellowship is an association of lay Chán practitioners based in the UK.[citation needed] They are registered as a charity in England and Wales, but also have contacts in Europe, principally in Norway, Poland, Germany, Croatia, Switzerland and the US.

See alsoEdit

- Buddhism

- Outline of Buddhism

- Timeline of Buddhism

- List of Buddhists

- Buddhism in Japan

- Buddhist modernism

- Chinese Chán

NotesEdit

- ^ Compare vitarka-vicara, «discursive thinking,» which is present in the dhyana, and stilled in the second dhyana. While the Theravada-tradition interprets vitarka-vicara as the concentration of the mind on an object of meditation, thereby stilling the mind, Polak notes that vitarka-vicara is related to thinking about the sense-impressions, which gives rise to further egoistical thinking and action.[30] The stilling of this thinking fits into the Buddhist training of sense-withdrawal and right effort, culminating in the eqaunimity and mindfulness of dhyana-practice.[30][31]

- ^ Her book The Wild White Goose describes her experiences in Japan

ReferencesEdit

- ^ a b Cook 2003.

- ^ Dumoulin, Heinrich; Heisig, James W; Knitter, Paul F (1990). Zen Buddhism, a history: volume 2, Japan. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-908240-9. OCLC 1128825155. Archived from the original on 2021-07-11. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Kraft, Kenneth; University of Hawaii Press (1997). Eloquent Zen: Daitō and early Japanese Zen. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1383-3. OCLC 903351450. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Groner, Paul (2002). Saichō: the establishment of the Japanese Tendai School. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2371-9. OCLC 633217685. Archived from the original on 2021-07-11. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Nukariya, Kaiten; Kwei Fung Tsung Mih (2015). The religion of the Samurai: a study of Zen philosophy and discipline in China and Japan. ISBN 978-1-4400-7255-0. OCLC 974991710. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ a b Heine, Steven (2005). Did Dogen go to China? What Dogen wrote and when he wrote it. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530570-8. OCLC 179954965. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ a b Breugem, V. M. N. (2012-05-30). From prominence to obscurity : a study of the Darumashū : Japan’s first Zen school (Thesis). Leiden University. hdl:1887/19051. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ Breugem 2006, p. 39-60.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b, p. 7-8.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b, p. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d e f Snelling 1987

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:151

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:151–152

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:153

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:185

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:185–186

- ^ Dumoulin 2005b:198

- ^ a b c McMahan 2008

- ^ a b c Victoria 2006

- ^ a b c d Sharf 1993

- ^ Victoria 2010

- ^ Bodiford 1992:150

- ^ a b Kalupahana 1992.

- ^ Kapleau 1989

- ^ Sharfa 1993

- ^ Mumonkan. The Gateless Gate. Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2015-03-27.

- ^ a b c Zhu 2005.

- ^ Kalupahana 1992, p. 138-140.

- ^ Zhu 2005, p. 427.

- ^ a b Polak 2011.

- ^ Arbel 2017.

- ^ Herrigel 1952

- ^ Shoji & Year unknown

- ^ Hu Shih 1953

- ^ Heller & Year unknown

- ^ Merton 1968

- ^ Merton 1967a

- ^ Mertont 1967b

- ^ Warneka 2006

- ^ Tanahashi 1996

- ^ «Norwich Zen Buddhist Priory». Order of Buddhist Contemplatives. 24 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Zenways website https://zenways.org/

SourcesEdit

Printed sourcesEdit

- Almgren, Irina (2011), The myth of the all-wise zen-master and the irritating complexity of reality, archived from the original on 2012-04-26, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Arbel, Keren (2017), Early Buddhist Meditation: The Four Jhanas as the Actualization of Insight, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781315676043, ISBN 9781317383994, archived from the original on 2019-04-04, retrieved 2018-12-15

- Bodiford, William M. (1992), «Zen in the Art of Funerals: Ritual Salvation in Japanese Buddhism», History of Religions, 32 (2): 146–164, doi:10.1086/463322, S2CID 161648097

- Breugem, Vincent M.N. (2006), From Prominence to Obscurity: a Study of the Darumashū: Japan’s first Zen School, Thesis (PDF), Leiden University, archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-03-19, retrieved 2014-03-29

- Cook, Francis Dojun (vertaler) (2003), The Record of Transmitting the Light. Zen Master Keizan’s Denkoroku, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Dumonlin, Heinrich (2000), A History of Zen Buddhism, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005a), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005b), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7

- Ford, James Myoun, A Note On Dharma Transmission And The Institutions Of Zen, archived from the original on 2012-01-20, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Hau, Hoo (1975), The Sound of the One Hand: 281 Zen Koans with Answers

- Heine, Steven (2008), Zen Skin, Zen Marrow

- Heller, Christine (n.d.), Chasing Zen Clouds (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-14, retrieved 2007-01-07

- Herrigel, Eugen (1952), Zen in the Art of Archery, Pantheon, NY: Vintage Books, ISBN 978-0-375-70509-0

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2005), Introduction. In: Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan (PDF), World Wisdom Books, pp. xiii–xxi, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-09, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Hu Shih (January 1953), «Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism in China. Its History and Method», Philosophy East and West, 3 (1): 3–24, doi:10.2307/1397361, JSTOR 1397361, archived from the original on 2020-02-17, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Jaksch, Mary (2007), The Road to Nowhere. Koans and the Deconstruction of the Zen Saga (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-02-20, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Kalupahana, David J. (1992), The Principles of Buddhist Psychology, Delhi: ri Satguru Publications

- Kapleau, Philip (1989), The three pillars of Zen

- Lachs, Stuart (2006), The Zen Master in America: Dressing the Donkey with Bells and Scarves, archived from the original on 2012-01-20, retrieved 2011-12-13

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-518327-6

- McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen. Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism, The University Press Group Ltd, ISBN 978-0-520-23798-8

- McRae, John (2005), Critical introduction by John McRae to the reprint of Dumoulin’s A history of Zen (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-11, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Merton, Thomas (1967a), The Way of Chuang Tzu, New York: New Directions, ISBN 978-0-8112-0103-2

- Merton, Thomas (1967b), Mystics and Zen Masters, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-52001-4

- Merton, Thomas (1968), Zen and the Birds of Appetite, New Directions Publishing Corporation, ISBN 978-0-8112-0104-9

- Polak, Grzegorz (2011), Reexamining Jhana: Towards a Critical Reconstruction of Early Buddhist Soteriology, UMCS

- Sato, Kemmyō Taira, D.T. Suzuki and the Question of War (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-25

- Scaligero, Massimo (1960). «The Doctrine of the «Void» and the Logic of the Essence». East and West. 11 (4): 249–257.

- Sharf, Robert H. (August 1993), «The Zen of Japanese Nationalism», History of Religions, 33 (1): 1–43, doi:10.1086/463354, S2CID 161535877, archived from the original on 2020-12-29, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995), Whose Zen? Zen Nationalism Revisited (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-02, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Shoji, Yamada (n.d.), The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-14, retrieved 2007-01-03

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Suzuki, Shunryu (2011), Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki; Chayat, Roko Sherry (1996), Endless Vow. The Zen Path of Soen Nakagawa, Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications

- Tweed, Thomas A. (2005), «American Occultism and Japanese Buddhism. Albert J. Edmunds, D. T. Suzuki, and Translocative History» (PDF), Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 32 (2): 249–281, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-22, retrieved 2011-12-14

- Victoria, Brian Daizen (2006), Zen at war (Second ed.), Lanham e.a.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Victoria, Brian Daizen (2010), «The «Negative Side» of D. T. Suzuki’s Relationship to War» (PDF), The Eastern Buddhist, 41 (2): 97–138, archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-20, retrieved 2011-12-13

- Warneka, Timothy H. (2006), Leading People the Black Belt Way: Conquering the Five Core Problems Facing Leaders Today, Asogomi Publishing International, ISBN 978-0-9768627-0-3

- Wetering, Janwillem van de (1999), The Empty Mirror: Experiences in a Japanese Zen Monastery

- Zhu, Rui (2005), «Distinguishing Sōtō and Rinzai Zen: Manas and the Mental Mechanics of Meditation» (PDF), East and West, 55 (3): 426–446, archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-14, retrieved 2018-12-14

Web-sourcesEdit

- ^ Jalon, Allan M. (11 January 2003). «Meditating On War And Guilt, Zen Says It’s Sorry». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Apology for What the Founder of the Sanbo-Kyodan, Haku’un Yasutani Roshi, Said and Did During World War II

- ^ Jeff Shore: The constant practice of right effort[permanent dead link]

- ^ A Chronology of Thomas Merton’s Life Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine. The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ «Vatican discernments on the use of Zen and Yoga in christian prayer». Archived from the original on 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

Further readingEdit

- Modern classics

- Paul Reps & Nyogen Senzaki, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

- Philip Kapleau, The Three Pillars of Zen

- Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

- Classic historiography

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China. World Wisdom Books. ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan. World Wisdom Books. ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7

- Critical historiography

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995a), Whose Zen? Zen Nationalism Revisited (PDF)

- Victoria, Brian Daizen (2006), Zen at War. Lanham e.a.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. (Second Edition)

- Borup, Jorn (n.d.), Zen and the Art of inverting Orientalism: religious studies and genealogical networks

- Mcrae, John (2003), Seeing through Zen. Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. The University Press Group Ltd . ISBN 978-0-520-23798-8

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518327-6

- (Japanese) Zen as living religious institution and practice

- Borup, Jørn (2008), Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism: Myōshinji, a Living Religion, Brill

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1994), Teaching and Learning in the Zen Rinzai Monastery. In: Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol.20, No. 1, (Winter, 1994), 5-35 (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-25

External linksEdit

- Overview

- Zen Buddhism WWW Virtual Library

- The Zen Site

- Rinzai-zen

- Joint Council for Rinzai and Obaku Zen

- The International Research Institute for Zen Buddhism

- Soto-zen

- Website on Soto Zen

- Sanbo Kyodan

- Sanbo Kyodan Homepage

- Critical Zen-practice

- David Chapman

- Brad Warner

- Against the stream

- Zen-centers

- Zen Centers at Curlie

- Zen centers of the world

- Zen centers

- Texts

- Sacred-text.com’s collection of Zen texts

- Buddhanet’s collection of Zen texts

- Shambhala Sun Zen Articles Archived 2008-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Kyoto and Japanese Buddhism by Tokushi Yusho. Introduction to Zen culture in Kyoto.

- Critical Zen Research

- Steven Heine (2007), A Critical Survey of Works on Zen since Yampolsky

- Homepage of Robert H. Sharf

| Zen | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 禪 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 禅 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thiền | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 禪 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 선 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 禪 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 禅 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ぜん | |||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Zen |

Zen (Chinese: 禪; pinyin: Chán; Japanese: 禅, romanized: zen; Korean: 선, romanized: Seon; Vietnamese: Thiền) is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty, known as the Chan School (Chánzong 禪宗), and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.[1]

The term Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (chán), an abbreviation of 禪那 (chánnà), which is a Chinese transliteration of the Sanskrit word ध्यान dhyāna («meditation»).[note 1] Zen emphasizes rigorous self-restraint, meditation-practice and the subsequent insight into nature of mind (見性, Ch. jiànxìng, Jp. kensho, «perceiving the true nature») and nature of things (without arrogance or egotism), and the personal expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit of others.[3][4] As such, it de-emphasizes knowledge alone of sutras and doctrine,[5][6] and favors direct understanding through spiritual practice and interaction with an accomplished teacher[7] or Master.

Zen teaching draws from numerous sources of Sarvastivada meditation practice and Mahāyāna thought, especially Yogachara, the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, and the Huayan school, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[8][9] The Prajñāpāramitā literature,[10] as well as Madhyamaka thought, have also been influential in the shaping of the apophatic and sometimes iconoclastic nature of Zen rhetoric.[11]

Furthermore, the Chan School was also influenced by Taoist philosophy, especially Neo-Daoist thought.[12]

Etymology[edit]

The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation (kana: ぜん) of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (Middle Chinese: [dʑian]; pinyin: Chán), which in turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna (ध्यान),[2] which can be approximately translated as «contemplation», «absorption», or «meditative state».[13]

The actual Chinese term for the «Zen school» is 禪宗 (pinyin: Chánzōng), while «Chan» just refers to the practice of meditation itself (Chinese: 習禪; pinyin: xíchán) or the study of meditation (Chinese: 禪學; pinyin: chánxué) though it is often used as an abbreviated form of Chánzong.[14]

«Zen» is traditionally a proper noun as it usually describes a particular Buddhist sect. In more recent times, the lowercase «zen» is used when discussing the philosophy and was officially added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 2018.[15]

Practice[edit]

Dhyāna[edit]

The practice of dhyana or meditation, especially sitting meditation (坐禪,Chinese: zuòchán, Japanese: zazen / ざぜん) is a central part of Zen Buddhism.[16]

Chinese Buddhism[edit]

The practice of Buddhist meditation first entered China through the translations of An Shigao (fl. c. 148–180 CE), and Kumārajīva (334–413 CE), who both translated Dhyāna sutras, which were influential early meditation texts mostly based on the Yogacara (yoga praxis) teachings of the Kashmiri Sarvāstivāda circa 1st–4th centuries CE.[17] Among the most influential early Chinese meditation texts include the Anban Shouyi Jing (安般守意經, Sutra on ānāpānasmṛti), the Zuochan Sanmei Jing (坐禪三昧經,Sutra of sitting dhyāna samādhi) and the Damoduoluo Chan Jing (達摩多羅禪經,[18] Dharmatrata dhyāna sutra).[19] These early Chinese meditation works continued to exert influence on Zen practice well into the modern era. For example, the 18th century Rinzai Zen master Tōrei Enji wrote a commentary on the Damoduoluo Chan Jing and used the Zuochan Sanmei Jing as source in the writing of this commentary. Tōrei believed that the Damoduoluo Chan Jing had been authored by Bodhidharma.[20]

While dhyāna in a strict sense refers to the four dhyānas, in Chinese Buddhism, dhyāna may refer to various kinds of meditation techniques and their preparatory practices, which are necessary to practice dhyāna.[21] The five main types of meditation in the Dhyāna sutras are ānāpānasmṛti (mindfulness of breathing); paṭikūlamanasikāra meditation (mindfulness of the impurities of the body); maitrī meditation (loving-kindness); the contemplation on the twelve links of pratītyasamutpāda; and contemplation on the Buddha.[22] According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen, these practices are termed the «five methods for stilling or pacifying the mind» and serve to focus and purify the mind, and support the development of the stages of dhyana.[23] Chan also shares the practice of the four foundations of mindfulness and the Three Gates of Liberation (emptyness or śūnyatā, signlessness or animitta, and wishlessness or apraṇihita) with early Buddhism and classic Mahayana.[24]

Pointing to the nature of the mind[edit]

According to Charles Luk, in the earliest traditions of Chán, there was no fixed method or formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were simply heuristic methods, to point to the true nature of the mind, also known as Buddha-nature.[25] According to Luk, this method is referred to as the «Mind Dharma», and exemplified in the story (in the Flower Sermon) of Śākyamuni Buddha holding up a flower silently, and Mahākāśyapa smiling as he understood.[25] A traditional formula of this is, «Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas.»[26]

Observing the mind[edit]

According to John McRae, «one of the most important issues in the development of early Ch’an doctrine is the rejection of traditional meditation techniques,» that is, gradual self-perfection and the practices of contemplation on the body impurities and the four foundations of mindfulness.[27] According to John R. McRae the «first explicit statement of the sudden and direct approach that was to become the hallmark of Ch’an religious practice» is associated with the East Mountain School.[28] It is a method named «Maintaining the one without wavering» (shou-i pu i, 守一不移),[28] the one being the nature of mind, which is equated with Buddha-nature.[29] According to Sharf, in this practice, one turns the attention from the objects of experience, to the nature of mind, the perceiving subject itself, which is equated with Buddha-nature.[30] According to McRae, this type of meditation resembles the methods of «virtually all schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism,» but differs in that «no preparatory requirements, no moral prerequisites or preliminary exercises are given,» and is «without steps or gradations. One concentrates, understands, and is enlightened, all in one undifferentiated practice.»[28][note 2] Sharf notes that the notion of «Mind» came to be criticised by radical subitists, and was replaced by «No Mind,» to avoid any reifications.[32][note 3]

Meditation manuals[edit]

Early Chan texts also teach forms of meditation that are unique to Mahāyāna Buddhism, for example, the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind, which depicts the teachings of the 7th-century East Mountain school teaches a visualization of a sun disk, similar to that taught in the Sutra of the Contemplation of the Buddha Amitáyus.[34]

Later Chinese Buddhists developed their own meditation manuals and texts, one of the most influential being the works of the Tiantai patriarch, Zhiyi. His works seemed to have exerted some influence on the earliest meditation manuals of the Chán school proper, an early work being the widely imitated and influential Tso-chan-i (Principles of sitting meditation, c. 11th century), which doesn’t outline a vipassana practice which leads to wisdom (prajña), but only recommends practicing samadhi which will lead to the discovery of inherent wisdom already present in the mind.[35]

Common contemporary meditation forms[edit]

Mindfulness of breathing[edit]

During sitting meditation (坐禅, Ch. zuòchán, Jp. zazen, Ko. jwaseon), practitioners usually assume a position such as the lotus position, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza, often using the dhyāna mudrā. Often, a square or round cushion placed on a padded mat is used to sit on; in some other cases, a chair may be used.

To regulate the mind, Zen students are often directed towards counting breaths. Either both exhalations and inhalations are counted, or one of them only. The count can be up to ten, and then this process is repeated until the mind is calmed.[36] Zen teachers like Omori Sogen teach a series of long and deep exhalations and inhalations as a way to prepare for regular breath meditation.[37] Attention is usually placed on the energy center (dantian) below the navel.[38] Zen teachers often promote diaphragmatic breathing, stating that the breath must come from the lower abdomen (known as hara or tanden in Japanese), and that this part of the body should expand forward slightly as one breathes.[39] Over time the breathing should become smoother, deeper and slower.[40] When the counting becomes an encumbrance, the practice of simply following the natural rhythm of breathing with concentrated attention is recommended.[41][42]

Silent Illumination and shikantaza[edit]

A common form of sitting meditation is called «Silent illumination» (Ch. mòzhào, Jp. mokushō). This practice was traditionally promoted by the Caodong school of Chinese Chan and is associated with Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091—1157) who wrote various works on the practice.[43] This method derives from the Indian Buddhist practice of the union (Skt. yuganaddha) of śamatha and vipaśyanā.[44]

In Hongzhi’s practice of «nondual objectless meditation» the mediator strives to be aware of the totality of phenomena instead of focusing on a single object, without any interference, conceptualizing, grasping, goal seeking, or subject-object duality.[45]

This practice is also popular in the major schools of Japanese Zen, but especially Sōtō, where it is more widely known as Shikantaza (Ch. zhǐguǎn dǎzuò, «Just sitting»). Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification of the practice can be found throughout the work of the Japanese Sōtō Zen thinker Dōgen, especially in his Shōbōgenzō, for example in the «Principles of Zazen»[46] and the «Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen».[47] While the Japanese and the Chinese forms are similar, they are distinct approaches.[48]

Hua Tou and Kōan contemplation[edit]

Main article: Kōan

Calligraphy of «Mu» (Hanyu Pinyin: wú) by Torei Enji. It figures in the famous Zhaozhou’s dog kōan

During the Tang dynasty, gōng’àn (Jp. kōan) literature became popular. Literally meaning «public case», they were stories or dialogues, describing teachings and interactions between Zen masters and their students. These anecdotes give a demonstration of the master’s insight. Kōan are meant to illustrate the non-conceptual insight (prajña) that the Buddhist teachings point to. During the Sòng dynasty, a new meditation method was popularized by figures such as Dahui, which was called kanhua chan («observing the phrase» meditation), which referred to contemplation on a single word or phrase (called the huatou, «critical phrase») of a gōng’àn.[49] In Chinese Chan and Korean Seon, this practice of «observing the huatou» (hwadu in Korean) is a widely practiced method.[50] It was taught by the influential Seon master Chinul (1158–1210), and modern Chinese masters like Sheng Yen and Xuyun. Yet, while Dahui famously criticised «silent illumination,»[51][52] he nevertheless «did not completely condemn quiet-sitting; in fact, he seems to have recommended it, at least to his monastic disciples.»[51]

In the Japanese Rinzai school, kōan introspection developed its own formalized style, with a standardized curriculum of kōans, which must be studied and «passed» in sequence. This process includes standardized «checking questions» (sassho) and common sets of «capping phrases» (jakugo) or poetry citations that are memorized by students as answers.[53] The Zen student’s mastery of a given kōan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as dokusan, daisan, or sanzen). While there is no unique answer to a kōan, practitioners are expected to demonstrate their spiritual understanding through their responses. The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer and guide the student in the right direction. The interaction with a teacher is central in Zen, but makes Zen practice also vulnerable to misunderstanding and exploitation.[54] Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during zazen (sitting meditation), kinhin (walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. The goal of the practice is often termed kensho (seeing one’s true nature), and is to be followed by further practice to attain a natural, effortless, down-to-earth state of being, the «ultimate liberation», «knowing without any kind of defilement».[55]

Kōan practice is particularly emphasized in Rinzai, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.[56]

Nianfo chan[edit]

Nianfo (Jp. nembutsu, from Skt. buddhānusmṛti «recollection of the Buddha») refers to the recitation of the Buddha’s name, in most cases the Buddha Amitabha. In Chinese Chan, the Pure Land practice of nianfo based on the phrase Nāmó Āmítuófó (Homage to Amitabha) is a widely practiced form of Zen meditation which came to be known as «Nianfo Chan» (念佛禪). Nianfo was practiced and taught by early Chan masters, like Daoxin (580-651), who taught that one should «bind the mind to one buddha and exclusively invoke his name».[57] The practice is also taught in Shenxiu’s Kuan-hsin lun (觀心論).[57]

The Ch’uan fa-pao chi (傳法寶紀, Taisho # 2838, ca. 713), one of the earliest Chan histories, also shows this practice was widespread in early Chan:

Coming to the generation of [Hung-]jen, [Fa-]ju and Ta-tung, the dharma-door was wide open to followers, regardless of their capacities. All immediately invoked the name of the Buddha so as to purify the mind.[57]

Evidence for the practice of nianfo chan can also be found in Changlu Zongze’s (died c. 1107) Chanyuan qinggui (The Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery), perhaps the most influential Ch’an monastic code in East Asia.[57]

Nianfo continued to be taught as a form of Chan meditation by later Chinese figures such as Yongming Yanshou, Zhongfen Mingben, and Tianru Weize. During the late Ming, the tradition of Nianfo Chan meditation was continued by figures such as Yunqi Zhuhong and Hanshan Deqing.[58] Chan figures like Yongming Yanshou generally advocated a view called “mind-only Pure Land” (wei-hsin ching-t’u), which held that the Buddha and the Pure Land are just mind.[57]

This practice, as well as its adaptation into the «nembutsu kōan» was also used by the Japanese Ōbaku school of Zen. Nianfo chan is also practiced in Vietnamese Thien.

Bodhisattva virtues and vows[edit]

Victoria Zen Centre Jukai ceremony, January 2009

Since Zen is a form of Mahayana Buddhism, it is grounded on the schema of the bodhisattva path, which is based on the practice of the «transcendent virtues» or «perfections» (Skt. pāramitā, Ch. bōluómì, Jp. baramitsu) as well as the taking of the bodhisattva vows.[59][60] The most widely used list of six virtues is: generosity, moral training (incl. five precepts), patient endurance, energy or effort, meditation (dhyana), wisdom. An important source for these teachings is the Avatamsaka sutra, which also outlines the grounds (bhumis) or levels of the bodhisattva path.[61] The pāramitās are mentioned in early Chan works such as Bodhidharma’s Two entrances and four practices and are seen as an important part of gradual cultivation (jianxiu) by later Chan figures like Zongmi.[62][63]

An important element of this practice is the formal and ceremonial taking of refuge in the three jewels, bodhisattva vows and precepts. Various sets of precepts are taken in Zen including the five precepts, «ten essential precepts», and the sixteen bodhisattva precepts.[64][65][66][67] This is commonly done in an initiation ritual (Ch. shòu jiè, Jp. Jukai, Ko. sugye, «receiving the precepts»), which is also undertaken by lay followers and marks a layperson as a formal Buddhist.[68]

The Chinese Buddhist practice of fasting (zhai), especially during the uposatha days (Ch. zhairi, «days of fasting») can also be an element of Chan training.[69] Chan masters may go on extended absolute fasts, as exemplified by master Hsuan Hua’s 35 day fast, which he undertook during the Cuban missile crisis for the generation of merit.[70]

Physical cultivation[edit]

Traditional martial arts, like Japanese archery, other forms of Japanese budō and Chinese martial arts (gōngfu) have also been seen as forms of zen praxis. This tradition goes back to the influential Shaolin Monastery in Henan, which developed the first institutionalized form of gōngfu.[71] By the late Ming, Shaolin gōngfu was very popular and widespread, as evidenced by mentions in various forms of Ming literature (featuring staff wielding fighting monks like Sun Wukong) and historical sources, which also speak of Shaolin’s impressive monastic army that rendered military service to the state in return for patronage.[72] These Shaolin practices, which began to develop around the 12th century, were also traditionally seen as a form of Chan Buddhist inner cultivation (today called wuchan, «martial chan»). The Shaolin arts also made use of Taoist physical exercises (taoyin) breathing and energy cultivation (qìgōng) practices.[73] They were seen as therapeutic practices, which improved «internal strength» (neili), health and longevity (lit. «nourishing life» yangsheng), as well as means to spiritual liberation.[74]

The influence of these Taoist practices can be seen in the work of Wang Zuyuan (ca. 1820–after 1882), a scholar and minor bureaucrat who studied at Shaolin. Wang’s Illustrated Exposition of Internal Techniques (Neigong tushuo) shows how Shaolin exercises were drawn from Taoist methods like those of the Yi jin jing and Eight pieces of brocade, possibly influenced by the Ming dynasty’s spirit of religious syncretism.[75] According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen, Chinese Buddhism has adopted internal cultivation exercises from the Shaolin tradition as ways to «harmonize the body and develop concentration in the midst of activity.» This is because, «techniques for harmonizing the vital energy are powerful assistants to the cultivation of samadhi and spiritual insight.»[76] Korean Seon also has developed a similar form of active physical training, termed Sunmudo.

Bows and quivers at Engaku-ji temple, the temple also has a Dōjō for the practice of Kyūdō and the Zen priests practice this art here.[77]

In Japan, the classic combat arts (budō) and zen practice have been in contact since the embrace of Rinzai Zen by the Hōjō clan in the 13th century, who applied zen discipline to their martial practice.[78] One influential figure in this relationship was the Rinzai priest Takuan Sōhō who was well known for his writings on zen and budō addressed to the samurai class (especially his The Unfettered Mind) .[79]

The Rinzai school also adopted certain Chinese practices which work with qi (which are also common in Taoism). They were introduced by Hakuin (1686–1769) who learned various techniques from a hermit named Hakuyu who helped Hakuin cure his «Zen sickness» (a condition of physical and mental exhaustion).[80] These energetic practices, known as naikan, are based on focusing the mind and one’s vital energy (ki) on the tanden (a spot slightly below the navel).[81][82]

The arts[edit]

Certain arts such as painting, calligraphy, poetry, gardening, flower arrangement, tea ceremony and others have also been used as part of zen training and practice. Classical Chinese arts like brush painting and calligraphy were used by Chan monk painters such as Guanxiu and Muqi Fachang to communicate their spiritual understanding in unique ways to their students.[83] Zen paintings are sometimes termed zenga in Japanese.[84] Hakuin is one Japanese Zen master who was known to create a large corpus of unique sumi-e (ink and wash paintings) and Japanese calligraphy to communicate zen in a visual way. His work and that of his disciples were widely influential in Japanese Zen.[85] Another example of Zen arts can be seen in the short lived Fuke sect of Japanese Zen, which practiced a unique form of «blowing zen» (suizen) by playing the shakuhachi bamboo flute.

Intensive group practice[edit]

Intensive group meditation may be practiced by serious Zen practitioners. In the Japanese language, this practice is called sesshin. While the daily routine may require monks to meditate for several hours each day, during the intensive period they devote themselves almost exclusively to zen practice. The numerous 30–50 minute long sitting meditation (zazen) periods are interwoven with rest breaks, ritualized formal meals (Jp. oryoki), and short periods of work (Jp. samu) that are to be performed with the same state of mindfulness. In modern Buddhist practice in Japan, Taiwan, and the West, lay students often attend these intensive practice sessions or retreats. These are held at many Zen centers or temples.

Chanting and rituals[edit]

Chanting the Buddhist Scriptures, by Taiwanese painter Li Mei-shu

Most Zen monasteries, temples and centers perform various rituals, services and ceremonies (such as initiation ceremonies and funerals), which are always accompanied by the chanting of verses, poems or sutras.[86] There are also ceremonies that are specifically for the purpose of sutra recitation (Ch. niansong, Jp. nenju) itself.[87]

Zen schools may have an official sutra book that collects these writings (in Japanese, these are called kyohon).[86] Practitioners may chant major Mahayana sutras such as the Heart Sutra and chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (often called the «Avalokiteśvara Sutra»). Dhāraṇīs and Zen poems may also be part of a Zen temple liturgy, including texts like the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi, the Sandokai, the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī, and the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra.

The butsudan is the altar in a monastery, temple or a lay person’s home, where offerings are made to the images of the Buddha, bodhisattvas and deceased family members and ancestors. Rituals usually center on major Buddhas or bodhisattvas like Avalokiteśvara (see Guanyin), Kṣitigarbha and Manjushri.

An important element in Zen ritual practice is the performance of ritual prostrations (Jp. raihai) or bows.[88]

One popular form of ritual in Japanese Zen is Mizuko kuyō (Water child) ceremonies, which are performed for those who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion. These ceremonies are also performed in American Zen Buddhism.[89]

A widely practiced ritual in Chinese Chan is variously called the «Rite for releasing the hungry ghosts» or the «Releasing flaming mouth». The ritual might date back to the Tang dynasty, and was very popular during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when Chinese Esoteric Buddhist practices became diffused throughout Chinese Buddhism.[90] The Chinese holiday of the Ghost Festival might also be celebrated with similar rituals for the dead. These ghost rituals are a source of contention in modern Chinese Chan, and masters such as Sheng Yen criticize the practice for not having «any basis in Buddhist teachings».[91]

Another important type of ritual practiced in Zen are various repentance or confession rituals (Jp. zange) that were widely practiced in all forms of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. One popular Chan text on this is known as the Emperor Liang Repentance Ritual, composed by Chan master Baozhi.[92] Dogen also wrote a treatise on repentance, the Shushogi.[93] Other rituals could include rites dealing with local deities (kami in Japan), and ceremonies on Buddhist holidays such as Buddha’s Birthday.[94]

Funerals are also an important ritual and are a common point of contact between Zen monastics and the laity. Statistics published by the Sōtō school state that 80 percent of Sōtō laymen visit their temple only for reasons having to do with funerals and death. Seventeen percent visit for spiritual reasons and 3 percent visit a Zen priest at a time of personal trouble or crisis.[95]

Esoteric practices[edit]

Depending on the tradition, esoteric methods such as mantra and dhāraṇī are also used for different purposes including meditation practice, protection from evil, invoking great compassion, invoking the power of certain bodhisattvas, and are chanted during ceremonies and rituals.[96][97] In the Kwan Um school of Zen for example, a mantra of Guanyin («Kwanseum Bosal«) is used during sitting meditation.[98] The Heart Sutra Mantra is also another mantra that is used in Zen during various rituals.[99] Another example is the Mantra of Light (kōmyō shingon), which is common in Japanese Soto Zen and was derived from the Shingon sect.[100]

In Chinese Chan, the usage of esoteric mantras in Zen goes back to the Tang dynasty. There is evidence that Chan Buddhists adopted practices from Chinese Esoteric Buddhism in findings from Dunhuang.[101] According to Henrik Sørensen, several successors of Shenxiu (such as Jingxian and Yixing) were also students of the Zhenyan (Mantra) school.[102] Influential esoteric dhāraṇī, such as the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra and the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī, also begin to be cited in the literature of the Baotang school during the Tang dynasty.[103] Many mantras have been preserved since the Tang period and continue to be practiced in modern Chan monasteries. One common example is the Śūraṅgama Mantra,which has been heavily propagated by various prominent Chan monks, such as Venerable Hsuan Hua who founded the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas.[104] Another example of esoteric rituals practiced by the Chan school is the Mengshan Rite for Feeding Hungry Ghosts, which is practiced by both monks and laypeople during the Hungry Ghost Festival.[105][106][107] Chan repentance rituals, such as the Liberation Rite of Water and Land, also involve various esoteric aspects, including the invocation of esoteric deities such as the Five Wisdom Buddhas and the Ten Wisdom Kings.[108][109]

There is documentation that monks living at Shaolin temple during the eighth century performed esoteric practices there such as mantra and dharani, and that these also influenced Korean Seon Buddhism.[110] During the Joseon dynasty, the Seon school was not only the dominant tradition in Korea, but it was also highly inclusive and ecumenical in its doctrine and practices, and this included Esoteric Buddhist lore and rituals (that appear in Seon literature from the 15th century onwards). According to Sørensen, the writings of several Seon masters (such as Hyujeong) reveal they were esoteric adepts.[111]

In Japanese Zen, the use of esoteric practices within Zen is sometimes termed «mixed Zen» (kenshū zen 兼修禪), and the figure of Keizan Jōkin (1264–1325) is seen as introducing this into the Soto school.[112][113] The Japanese founder of the Rinzai school, Myōan Eisai (1141–1215) was also a well known practitioner of esoteric Buddhism and wrote various works on the subject.[114]

According to William Bodiford, a very common dhāraṇī in Japanese Zen is the Śūraṅgama spell (Ryōgon shu 楞嚴呪; T. 944A), which is repeatedly chanted during summer training retreats as well as at «every important monastic ceremony throughout the year» in Zen monasteries.[115] Some Zen temples also perform esoteric rituals, such as the homa ritual, which is performed at the Soto temple of Eigen-ji (in Saitama prefecture). As Bodiford writes, «perhaps the most notable examples of this phenomenon is the ambrosia gate (kanro mon 甘露門) ritual performed at every Sōtō Zen temple», which is associated feeding hungry ghosts, ancestor memorial rites and the ghost festival.[116] Bodiford also notes that formal Zen rituals of Dharma transmission often involve esoteric initiations.

Doctrine[edit]

Zen teachings can be likened to «the finger pointing at the moon».[117] Zen teachings point to the moon, awakening, «a realization of the unimpeded interpenetration of the dharmadhatu».[118] But the Zen-tradition also warns against taking its teachings, the pointing finger, to be this insight itself.[119][120][121][122]

Buddhist Mahayana influences[edit]

Though Zen-narrative states that it is a «special transmission outside scriptures», which «did not stand upon words»,[123] Zen does have a rich doctrinal background that is firmly grounded in the Buddhist tradition.[124] It was thoroughly influenced by Mahayana teachings on the bodhisattva path, Chinese Madhyamaka (Sānlùn), Yogacara (Wéishí), Prajñaparamita, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, and other Buddha nature texts.[125][126][127] The influence of Madhyamaka and Prajñaparamita can be discerned in the stress on non-conceptual wisdom (prajña) and the apophatic language of Zen literature.[125][128][129][note 4]

The philosophy of the Huayan school also had an influence on Chinese Chan. One example is the Huayan doctrine of the interpenetration of phenomena, which also makes use of native Chinese philosophical concepts such as principle (li) and phenomena (shi).[130] The Huayan theory of the Fourfold Dharmadhatu also influenced the Five Ranks of Dongshan Liangjie (806–869), the founder of the Caodong Chan lineage.[131]

Buddha-nature and subitism[edit]

Central in the doctrinal development of Chan Buddhism was the notion of Buddha-nature, the idea that the awakened mind of a Buddha is already present in each sentient being[132] (pen chueh in Chinese Buddhism, hongaku in Japanese Zen).[133] This Buddha-nature was initially equated with the nature of mind, while later Chan-teachings evaded any reification by rejecting any positivist terminology.[134][note 3] The idea of the immanent character of the Buddha-nature took shape in a characteristic emphasis on direct insight into, and expression of this Buddha-nature.[135][136] It led to a reinterpretation and Sinification of Indian meditation terminology, and an emphasis on subitism, the idea that the Buddhist teachings and practices are comprehended and expressed «sudden,»[137] c.q. «in one glance,» «uncovered all together,» or «together, completely, simultaneously,» in contrast to gradualism, «successively or being uncovered one after the other.»[138] The emphasis on subitism led to the idea that «enlightenment occurs in a single transformation that is both total and instantaneous»[139] (Ch. shih-chueh).[140]

While the attribution of gradualism, attributed by Shenhui to a concurring faction, was a rhetoric device, it led to a conceptual dominance in the Chan-tradition of subitism, in which any charge of gradualism was to be avoided.[135][note 5] This «rhetorical purity» was hard to reconcile conceptually with the actual practice of meditation,[142][135] and left little place in Zen texts for the description of actual meditation practices, apparently rejecting any form of practice.[143][135][134][note 6] Instead, those texts directly pointed to and expressed this awakened nature, giving way to the paradoxically nature of encounter dialogue and koans.[135][134]

Caodong/Sōtō/Tào Động[edit]

Main article: Sōtō

Japanese Buddhist monk from the Sōtō Zen sect

Sōtō is the Japanese line of the Chinese Caodong school, which was founded during the Tang Dynasty by Dongshan Liangjie. The Sōtō-school has de-emphasized kōans since Gentō Sokuchū (circa 1800), and instead emphasized shikantaza.[145] Dogen, the founder of Soto in Japan, emphasized that practice and awakening cannot be separated. By practicing shikantaza, attainment and Buddhahood are already being expressed.[146] For Dogen, zazen, or shikantaza, is the essence of Buddhist practice.[147] Gradual cultivation was also recognized by Dongshan Liangjie.[148]

A lineage also exists in Vietnam, founded by 17th-century Chan master Thông Giác Đạo Nam. In Vietnamese, the school is known as «Tào Động.»[149]

Linji/Rinzai[edit]

The Rinzai school is the Japanese lineage of the Chinese Linji school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Linji Yixuan. The Rinzai school emphasizes kensho, insight into one’s true nature.[150] This is followed by so-called post-satori practice, further practice to attain Buddhahood.[151][152][153]

Other Zen-teachers have also expressed sudden insight followed by gradual cultivation. Jinul, a 12th-century Korean Seon master, followed Zongmi, and also emphasized that insight into our true nature is sudden, but is to be followed by practice to ripen the insight and attain full buddhahood. This is also the standpoint of the contemporary Sanbo Kyodan, according to whom kenshō is at the start of the path to full enlightenment.[154]

To attain this primary insight and to deepen it, zazen and kōan-study is deemed essential. This trajectory of initial insight followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji in his Three Mysterious Gates and Hakuin Ekaku’s Four Ways of Knowing.[155] Another example of depiction of stages on the path are the Ten Bulls, which detail the steps on the path.

Scripture[edit]

The role of the scripture[edit]

Zen is deeply rooted in the teachings and doctrines of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[156] Classic Zen texts, such as the Platform sutra, contain numerous references to Buddhist canonical sutras.[157] According to Sharf, Zen monastics «are expected to become familiar with the classics of the Zen canon».[158] A review of the early historical documents and literature of early Zen masters clearly reveals that they were well versed in numerous Mahāyāna sūtras,[5][note 7][note 8][5][note 9] as well as Mahayana Buddhist philosophy such as Madhyamaka.[125]

Nevertheless, Zen is often pictured as anti-intellectual.[156] This picture of Zen emerged during the Song Dynasty (960–1297), when Chán became the dominant form of Buddhism in China, and gained great popularity among the educated and literary classes of Chinese society. The use of koans, which are highly stylized literary texts, reflects this popularity among the higher classes.[135] The famous saying «do not establish words and letters», attributed in this period to Bodhidharma,[161]

…was taken not as a denial of the recorded words of the Buddha or the doctrinal elaborations by learned monks, but as a warning to those who had become confused about the relationship between Buddhist teaching as a guide to the truth and mistook it for the truth itself.[162]

What the Zen tradition emphasizes is that the enlightenment of the Buddha came not through conceptualization but rather through direct insight.[163] But direct insight has to be supported by study and understanding (hori[164]) of the Buddhist teachings and texts.[165][note 10] Intellectual understanding without practice is called yako-zen, «wild fox Zen», but «one who has only experience without intellectual understanding is a zen temma, ‘Zen devil‘«.[167]

Grounding Chán in scripture[edit]

The early Buddhist schools in China were each based on a specific sutra. At the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, by the time of the Fifth Patriarch Hongren (601–674), the Zen school became established as a separate school of Buddhism.[168] It had to develop a doctrinal tradition of its own to ascertain its position[135] and to ground its teachings in a specific sutra. Various sutras were used for this even before the time of Hongren: the Śrīmālādevī Sūtra (Huike),[169] Awakening of Faith (Daoxin),[169] the Lankavatara Sutra (East Mountain School),[169][5] the Diamond Sutra[170] (Shenhui),[169] and the Platform Sutra.[5][170] The Chan tradition drew inspiration from a variety of sources and thus did not follow any single scripture over the others.[171] Subsequently, the Zen tradition produced a rich corpus of written literature, which has become a part of its practice and teaching. Other influential sutras are the Vimalakirti Sutra,[172][173][174] Avatamsaka Sutra,[175] the Shurangama Sutra,[176] and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra.[177]

In his analysis of the works of the influential Hongzhou school of Chan, Mario Poceski notes that they cite the following Mahayana sutras: the Lotus Sutra 法華經, the Huayan 華嚴經, the Nirvana 涅盤經, the Laṅkāvatāra 楞伽經, the Prajñāpāramitās 般若經, the Mahāratnakūta 大寶積經, the Mahāsamnipāta 大集經, and the Vimalakīrti 維摩經.[178]

Literature[edit]

The Zen-tradition developed a rich textual tradition, based on the interpretation of the Buddhist teachings and the recorded sayings of Zen-masters. Important texts are the Platform Sutra (8th century), attributed to Huineng ;[135] the Chán transmission records, teng-lu,[179] such as The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Ching-te ch’uan-teng lu), compiled by Tao-yün and published in 1004;[180] the «yü-lü» genre[181] consisting of the recorded sayings of the masters, and the encounter dialogues; the koan-collections, such as The Gateless Barrier and the Blue Cliff Record.

Organization and institutions[edit]

Religion is not only an individual matter, but «also a collective endeavour».[182] Though individual experience[183] and the iconoclastic picture of Zen[184] are emphasised in the Western world, the Zen-tradition is maintained and transferred by a high degree of institutionalisation and hierarchy.[185][186] In Japan, modernity has led to criticism of the formal system and the commencement of lay-oriented Zen-schools such as the Sanbo Kyodan[187] and the Ningen Zen Kyodan.[188] How to organize the continuity of the Zen-tradition in the West, constraining charismatic authority and the derailment it may bring on the one hand,[189][190][54] and maintaining the legitimacy and authority by limiting the number of authorized teachers on the other hand,[182] is a challenge for the developing Zen-communities in the West.

Narratives[edit]

The Chán of the Tang Dynasty, especially that of Mazu and Linji with its emphasis on «shock techniques», in retrospect was seen as a golden age of Chán.[135] It became dominant during the Song Dynasty, when Chán was the dominant form of Buddhism in China, due to support from the Imperial Court.[135] This picture has gained great popularity in the West in the 20th century, especially due to the influence of D.T. Suzuki,[191] and further popularized by Hakuun Yasutani and the Sanbo Kyodan.[183] This picture has been challenged, and complemented, since the 1970s by modern scientific research on Zen.[135][192][193][194][195][196]