A Guide to Japanese Pronunciation: Sounds, Words, and Sentences

Who knew glottal fricatives and voiced alveolar nasal stops could be so rewarding?

May 23, 2018

•

words written by

•

Art by

Aya Francisco

How do you feel about your Japanese pronunciation? Depending on your native language, a lot of it is very easy. You can produce accurate sounds, similar to those of a native Japanese speaker.

Spend an hour going through this page. You’ll be able to apply these concepts literally every time you use or study Japanese.

But, there are a few sounds that most people aren’t doing right. R’s and F’s, for example. Beyond that, there are pronunciation challenges such as long vowels, double consonants, the nasal が, and pitch accent. Not to mention it all gets ten times more difficult once you start applying these concepts to sentences, not just words.

Can Japanese people understand you even if you don’t do all of those things? Probably. But to us, learning proper pronunciation is part of the fun. And, don’t you want to speak the best Japanese you possibly can? It’s not as hard as you think to make progress with your pronunciation. Instead of ignoring it, spend an hour going through this page. You’ll be able to apply these concepts literally every time you use or study Japanese.

We’re going to start with foundational work first, then build from there. As you read, try it all out: the mouth shapes, the sounds, the tongue positions—I think you’ll be surprised at how much you’re able to improve in such a short time.

- Japanese Sounds and Writing

- Syllables and Spelling

- Japanese Sounds and Your Mouth

- Japanese Vowels

- Consonants

- Where the Sound Is Blocked

- How the Sound Is Blocked

- Vocal Cords

- Mouth vs Nose

- Important Differences

- ふ

- ひ

- ん

- らりるれろ

- を

- じ/ぢ and ず/づ

- Pronouncing Vocabulary

- Short and Long Sounds

- Double Consonants

- Dropping す ち and し

- Nasal が

- Pitch and Speaking Japanese

- Pitch Accent Patterns

- Same Spelling, Different Pitch

- Pronouncing Phrases and Sentences

Prerequisite: This guide is going to use hiragana and some katakana, so we highly recommend you learn it beforehand by reading our guides. Don’t worry! They can be learned in a day or two, just come back when you’re ready. The final section will include Japanese sentences that fall around the intermediate level.

Japanese Sounds and Writing

First, we need to start with the sounds that are available to us. For that, we look at written Japanese, which is made up of three parts.

- Hiragana

- Katakana

- Kanji

Hiragana and katakana are phonetic syllabaries, which is a fancy way of saying two things:

- The symbols represent sounds

- Each symbol represents a syllable

While hiragana and katakana look different, they both represent the same sounds, they just have different uses. Kanji are the characters borrowed from China, but luckily, you don’t have to worry about kanji or katakana right now. Let’s focus on hiragana and how understanding it can help you with Japanese pronunciation.

Each hiragana symbol represents a syllable sound. This is different from English in a few different ways. First, just because you know how to pronounce a word in English doesn’t mean you know how to spell it. English is notoriously difficult to learn for many reasons, but a big one is that spelling and pronouncing words can be a big headache. We have words like colonel, recipe, through, and threw. It’s a fascinating mess.

Japanese, on the other hand, has mostly kept up with how words are pronounced and written. This means that what you see is (almost always) what you get, and if you can say it, you can spell it, and vice versa1.

Syllables and Spelling

Understanding that Japanese is made up of phonetic syllables is incredibly helpful when it comes to understanding how to pronounce them.

Each hiragana symbol represents a syllable.

There are vowels: あいうえお

And consonants plus vowels: かきくけこ (and the rest)

Instead of splitting up their individual sounds, Japanese keeps these sounds in larger chunks. For example, if you wanted to express the sound か in English it would be spelled «ka» with the consonant k and the vowel a. For ち it would be two consonants to make the sound ch (c+h) and the vowel i. Instead of separating everything into its smallest part or combinations to represent unique sounds (like ch) with letters, Japanese uses syllables to make the same sound using fewer symbols.

I could get a lot deeper into syllables and how they differ in Japanese, but this is enough to understand pronouncing Japanese for now. If you’d like to learn more, you can alway head over to our article on haiku, and read the section on mora (the Japanese equivalent to syllables).

Understanding that Japanese is made up of phonetic syllables (syllables that directly correlate to a sound) is incredibly helpful when it comes to understanding how to pronounce them.

Japanese Sounds and Your Mouth

Every sound in a language, Japanese included, can be explained by the place where the sound originates and the movements of your mouth, nose, and throat. We’re going to learn some terms that you can use to help understand these sounds in Japanese.

In some languages, these placements and the variations between them can get complicated, but Japanese doesn’t have many sounds compared to languages like English or Mandarin or Russian, so you’re already at an advantage!

Japanese Vowels

Let’s begin with the least complicated sounds in Japanese: vowels. Vowels are made when the air coming out of your lungs is not blocked by anything. That air travels from your lungs, vibrates through your vocal cords, and out of your mouth without anything else getting in the way.

The only thing that distinguishes vowel sounds from each other is the placement of your tongue as the air comes out of your mouth.

Two things are important for us to know:

- The tongue’s height

- The tongue’s dimensions

For height, the tongue can be in the high, mid, or low position.

For dimensions, the tongue can be front, center, or back.

Let’s look at all of the Japanese vowels:

あ = low, center

い = high, front

う = high, back

え = mid, front

お = mid, back

Now say each of these sounds out loud, and feel where your tongue is in your own mouth as you imitate the audio. Feel it move forward and backward as well as up and down.

- あ

- い

- う

- え

- お

That’s it! Those are all of the vowel sounds in Japanese, and the best thing is that they pretty much never change. They’re always pronounced the same way, no matter what word they’re in, and what they come before or after doesn’t change them. This is rare in other languages, like English, where the vowel «a» could be pronounced differently depending on where it is in a word.

Say these words aloud:

cat

care

car

caw

Did you feel your tongue move around? They are all short words with «a» as the middle vowel, but each of them are made with your tongue in a different position in your mouth. This is one of the reasons that English can’t be called a phonetic language. Those are actually four different sounds, and in IPA (the International Phonetic Alphabet) we use four different symbols to represent them because, for the sake of pronunciation, they’re different vowels.

cat: æ

care: eə

car: ɑ

caw: ɔ

So while it may seem that we have the same number of vowels as Japanese in English, it’s only true for the written language. In reality, English is a much more phonetically rich language—there are actually more sounds than it seems!

Consonants

Consonants are created when the air is blocked on its way out of your body.

Consonants have a few more things going on than vowels, and are created when the air is blocked on its way out of your body. Remember, vowels don’t have any blockage, they’re only affected by your tongue’s position, but your tongue isn’t actually blocking any of that air from getting out. It’s shaping the air so that the sound changes slightly before it exits.

There are four important things to consider when we make consonants:

- Where the sound is blocked

- How the sound is blocked

- If your vocal cords vibrated

- If it went through your mouth or your nose

Where the Sound Is Blocked

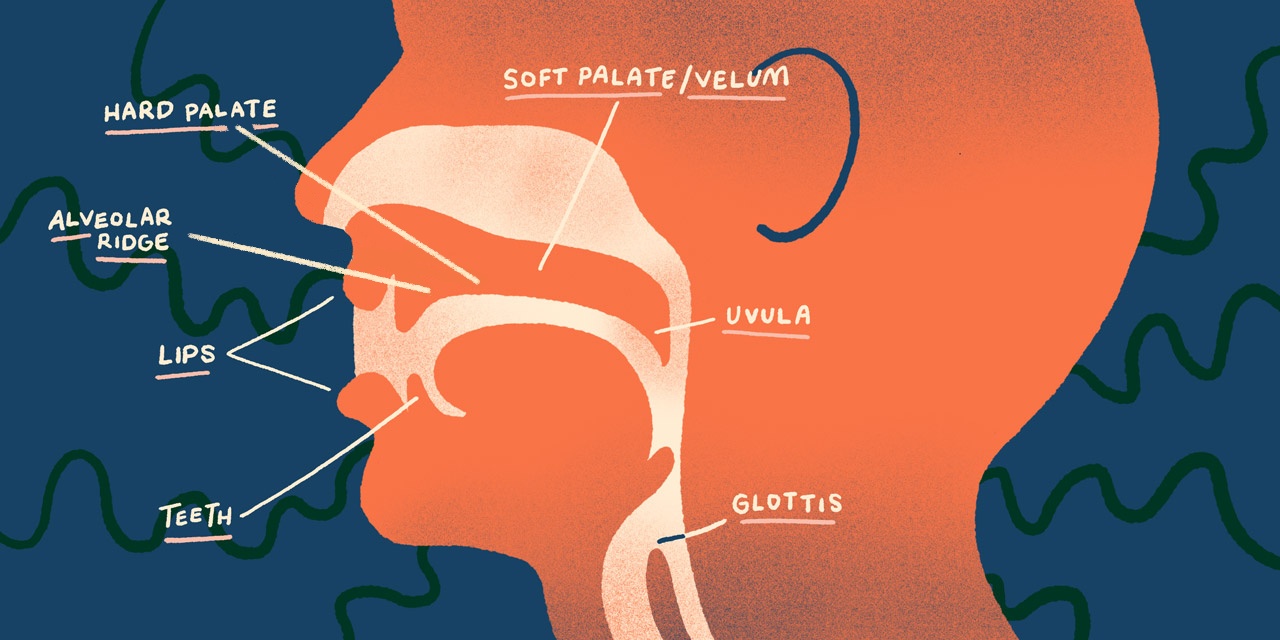

There are different places in your mouth where sound can be blocked and what parts can do the blocking. Thanks to biology and linguistics coming together, all of these body parts have names.

Lips: The mouth openings you use for smooching and smiling.

Teeth: The hard points you use to chomp food.

Hard Palate: That bony, ribbed hard part behind your teeth on the roof of your mouth.

Alveolar Ridge: The ridge right before the end of the hard palate.

Soft Palate (Velum): The soft part after the alveolar ridge that doesn’t have any bones or ridges.

Uvula: The dangly tissue in the back of your throat.

Glottis: The opening between your vocal cords.

If you moved your tongue around your mouth or looked in the mirror while you read that, you’re using this guide correctly. I highly recommend you explore your mouth to see and feel these bits (but don’t touch your uvula, it’ll make you throw up).

How the Sound Is Blocked

How the air is being blocked in your mouth goes hand-in-hand with where it’s being blocked. We also have terms for the different types of blockage that go on in there.

Stops: The air is being completely blocked.

Fricatives: The air is being forced through a narrow opening and is not completely blocked, instead this narrow opening creates «friction,» thus the name «fricative.»

Affricates: This is a combination of a stop and a fricative. The air is stopped for a short time and then released through a narrow opening, creating friction.

Liquids: Similar to fricatives, but with less friction, allowing more space for the air to move through.

And then there’s the special case:

Glides: A mix of a vowel and a consonant, sometimes called a «semivowel.» They’re almost exactly like vowels except that you move more than your tongue to make them. They act like consonants in Japanese, so we put them here.

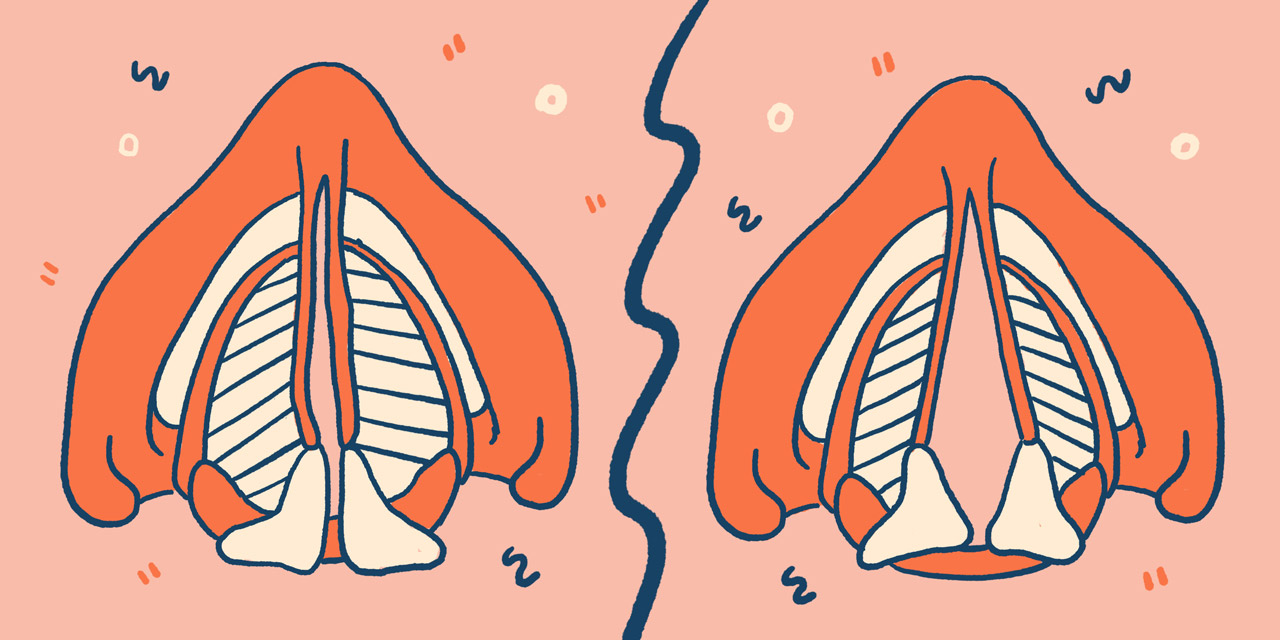

Vocal Cords

Your vocal cords (or vocal folds) are these two little flaps of membrane that live in your throat and control how much air goes out of your trachea, which is the tube that leads into your lungs (as opposed to your stomach). They open when you breathe, and constrict causing them to vibrate when you speak. Every time you make a vowel sound, your vocal cords are vibrating. That vibration is the origin of the sound you then shape with your tongue, lips, and other mouth parts.

But not all consonants need the vocal cords to vibrate to create a sound. Your body is capable of making sounds without needing your vocal cords. Try to make kissy-sounds with your lips. Or snap your fingers. You didn’t need your vocal cords to make those sounds, but you still made them with your body, and you could hear them.

We call consonants that do vibrate the vocal cords voiced consonants. While consonants that do not vibrate the vocal cords are then unvoiced consonants.

For this same reason, all vowels in Japanese are considered voiced because they all require your vocal cords to vibrate. The name «vowel» actually comes from the word for «vocal,» so that should help you remember vowels are voiced.

Another bonus we get from hiragana being a phonetic syllabary is that all voiced consonants are marked with little markings called diacritics.

゛(dakuten) means a sound is voiced

゜(handakuten) means an h turns to a p

Mouth vs Nose

A sound’s final destination is how it leaves (or tries to leave) your body. After its journey from your lungs, past your vocal cords, and up into your face it has two methods of escape: your mouth and your nose. This is where we can go back to our first important thing: where is the sound being blocked?

If the air is going into your mouth, then we call this an oral consonant. But if the air is going into your nose to make the sound, we call it a nasal consonant.

When talking about consonants, oral consonants are much more common in Japanese and English. This means they’re usually omitted when explaining a sound, just like saying a «voiced vowel» is redundant, you usually don’t see something called an «oral consonant,» and instead nasal consonants will be marked as the outliers.

Let’s go over the different consonant sounds in Japanese so you can feel exactly what’s happening in your own mouth. These won’t be in aiueo order, which you probably used to learn hiragana. Instead, we’re going to travel through your mouth based on the order of the important things above. Think of it like a tour of your own mouth parts.

Remember to keep these four important questions in your mind:

- Where is the air being blocked?

- How is the air being blocked?

- Did your vocal cords vibrate?

- Did the air go through your nose or your mouth?

We have some special adjectives that answer each one.

- Bilabial = both lips

- Alveolar = alveolar ridge

- Velar = velum/soft palate

- Nasal = nose

- Palato-Alveolar = behind alveolar ridge but before soft palate

- Glottal = glottis

- Uvular = uvula

Voiced Bilabial Stops: ばびぶべぼ

Voiceless Bilabial Stops: ぱぴぷぺぽ

Voiced Bilabial Nasal Stop: まみむめも ん

Both of your lips are coming together to completely stop the air. There are three types of bilabial stops in Japanese: b, p, and m.

- ば

- び

- ぶ

- べ

- ぼ

- ぱ

- ぴ

- ぷ

- ぺ

- ぽ

- ま

- み

- む

- め

- も

- ん

Voiced Alveolar Stop: だでど

Voiceless Alveolar Stop: たてと

Voiced Alveolar Nasal Stop: なにぬねの ん

Your tongue is hitting right behind your teeth to completely stop the air. There are three types of alveolar stops in Japanese: d, t, and n.

- だ

- で

- ど

- た

- て

- と

- な

- に

- ぬ

- ね

- の

- ん

Voiceless Velar Stop: かきくけこ

Voiced Velar Nasal Stop: ん (sometimes がぎぐげご)

The middle of your tongue is hitting your velum/soft palate to completely stop the air. There are three types of velar stops in Japanese: g, k, and in some accents a nasal g sound that we don’t have in English, and looks like this in IPA: ŋ. More on that later.

- が

- ぎ

- ぐ

- げ

- ご

- か

- き

- く

- け

- こ

- ん

Voiceless Bilabial Fricative: ふ

Your lips are forming a small opening, creating friction, for the air to pass through. There is only one of these in Japanese and none in English, but it’s in between f and h. More on that later.

- ふ

Voiced Alveolar Fricative: ざずぜぞ

Voiceless Alveolar Fricative: さすせそ

Your tongue is creating friction close behind your teeth. There are two types of alveolar fricatives in Japanese: z and s.

- ざ

- ず

- ぜ

- ぞ

- さ

- す

- せ

- そ

Voiceless Palato-Alveolar Fricative: し

The tip of your tongue is creating friction close behind the alveolar ridge. This is the only one in Japanese, and it’s slightly further back than its English counterpart: sh.

- し

Voiceless Palatal Fricative: ひ

The body of your tongue is creating friction close to your hard palate. There is only one in Japanese, and it has no match in English. More on that later.

- ひ

Voiceless Glottal Fricative: はへほ

You’re creating friction between your vocal cords, at the glottis, which is the name for the opening between them. Basically these folds are coming closer together than they normally do, and the sound is coming from that friction. There is one glottal fricative in Japanese: h.

- は

- へ

- ほ

Voiced Alveolar Affricate: づ

Voiceless Alveolar Affricate: つ

Your tongue is stopping behind your teeth, then releasing, creating friction. There are two alveolar affricates in Japanese: dzu and tsu.

- づ

- つ

Voiced Palato-Alveolar Affricate: じぢ

Voiceless Palato-Alveolar Affricate: ち

The tip of your tongue is stopping behind the alveolar ridge, then releasing, creating friction. There are three palato-alveolar affricates in Japanese: ji, dzi, and chi. Although じ and ぢ used to be pronounced differently, they are now considered the same sound, with the exception of a few regional dialects.

- じ

- ぢ

- ち

Voiced Alveolar Liquid: らりるれろ

Alveolar liquids in Japanese are special because they do something called an alveolar tap. This means the tip of your tongue is touching the alveolar ridge for just a moment before releasing. There is one alveolar liquid in Japanese, which is usually represented with an r, but don’t be fooled. They aren’t the same sound. More on that later.

- ら

- り

- る

- れ

- ろ

Voiced Velar Glide: わ

The body of your tongue is moving toward your velum/soft palate, and your lips are moving closer together. There is one velar glide in Japanese: w.

- わ

Voiced Palatal Glide: やゆよ

The body of your tongue is moving toward your hard palate. There is one palatal glide in Japanese: y.

- や

- ゆ

- よ

Voiced Uvular Nasal: ん

The body of your tongue is touching your uvula, but it probably feels like it isn’t that far back. There is one uvular nasal in Japanese: n.

- ん

Important Differences

Now let’s get into all of those «more on that later» stuff we put off earlier. Just because Japanese doesn’t have as many sounds as English, doesn’t mean the ones they do have are exactly the same. There are a few important differences that will help you sound more like a native speaker and less like a Japanese learner.

ふ

Hiragana teaches this as hu or fu, but these aren’t accurate because this sound doesn’t exist in English. The English fu is made by stopping the air with your bottom lip and your teeth. This is a labio-dental stop, which as you probably noticed, isn’t even in our list of Japanese mouth sound adjectives. That’s because they just don’t have any.

The ふ sound is made by blowing air through a narrow space between both lips, making it a bilabial fricative.

- ふるい

- おふろ

- ふくろう

- おふだ

ひ

Hiragana teaches this as hi, but sometimes it sounds less like heat and more like the German ich or the English huge, when an old man says it kinda of exaggeratedly. For some people this is very easy to hear, while other people may make their h sound much closer to ours in English. The man in the following audio, has a very clear Japanese ひ.

- ひと

- ひとり

- ひろい

ん

Did you notice that ん showed up on our list four times?! That’s because this is the most inconsistent sound in Japanese. In fact, just its existence is unique because it’s the only consonant in Japanese that isn’t a syllable in the traditional English sense.

ん is a consonant without a vowel after it. It changes in pronunciation depending where it is. It is the biggest exception in all of the Japanese sounds!

How to pronounce it depends on where it appears.

ん → n

- よん

- てんのう

- ほんです

ん → m

- せんぱい

- しんぶん

ん → ŋ

- せんご

- ほんが

When ん changes based on where it is, it is called «coarticulation,» and it happens in English too. Your brain is basically deciding that it’s easier for your mouth to say it this way. Listen once more to «shimbun.»

- しんぶん

Pronouncing ん correctly is super important because of the confusion it can cause with なにぬねの. This is a common issue with English speakers in Japan, especially people reading romaji pronunciations from guides and travel books.

Let’s say you’re in the city of Itami and you want to find New Itami Station. This is spelled shinitamieki in romaji. But it’s pronounced:

- しんいたみえき

However, if you mistake that for:

- しにたみえき

Did you notice that ん showed up on our list four times?! That’s because this is the most inconsistent sound in Japanese.

It sounds like you’re saying, «I feel like I want to die Station» not «New Itami Station.»

There are over fifty cases where switching ん with なにぬねの just in train station names can make you end up in the wrong place. We checked! So it’s pretty important that you’re able to read hiragana and pronounce it, especially without relying on romaji.

らりるれろ

The Japanese r/l sound is the sound people get tripped up by the most. Probably because it seems like it should be pronounced like the two English sounds it gets translated to the most: r and l.

Let’s take a look at those English sounds:

They’re both alveolar voiced liquids (alveolar ridge plus less friction than other consonants), like the Japanese らりるれろ, but the tongue is doing very different things:

r: the tongue is in the middle of the mouth, curled up, and not touching any other parts.

l: the tip of your tongue is touching your alveolar ridge, but the air is moving around the sides.

らりるれろ: the tip of your tongue is touching the alveolar ridge quickly, then releasing.

While they are all voiced, in the same area, and let quite a bit of air through, your tongue is doing different things.

- ら

- り

- る

- れ

- ろ

If you have to compare it to English, think of the r/l location but the d sound.

を

While you may spell this «wo» when you’re typing, を is pronounced like お when you’re talking and using it as a particle. However, in songs and old Japanese, you’ll sometimes hear it pronounced as «wo.»

- を

じ/ぢ and ず/づ

In modern Japanese, these pairs of voiced sounds, じ/ぢ and ず/づ, are pronounced exactly the same way. There are a few regional dialects in which people still differentiate these sounds. However, because of the widespread influence of the Tokyo accent, the difference in pronunciation is becoming less significant.

Despite these shared sounds, in written Japanese, you won’t encounter ぢ or づ as much as you do じ or ず. This is because づ and ぢ are only used when つ and ち are voiced in cases of rendaku or repeating sounds. Here are some examples.

- つづく

- はなづまり

- ちぢまる

- ちかぢか

Pronouncing Vocabulary

You know how to pronounce all the sounds! But making words is more than just shoving those separate sounds together to make words. Well, in some cases it isn’t, but there are plenty of new things that come with pronouncing different Japanese words.

All of these are essential to pronouncing words clearly!

Short and Long Sounds

Japanese has different symbols for long and short sounds. In hiragana, long sounds are usually represented with a vowel and in katakana with the ー symbol. In hiragana, short sounds are represented with the っ commonly referred to as the «small tsu.» Similarly, katakana uses its own small tsu ッ.

Long sounds:

- vowel sound followed by あいうえお

- ー

Short sounds:

- っ

- ッ

Let’s practice hearing and saying the differences:

- りょうこう

- りょこう

- ローマ字

Can you hear the differences? A really helpful way to think about this difference is to focus on the emphasis. Japanese may not have stress or emphasis the same way as we do in English, but if you listen, you can hear that the long sounds have more stress. And the short sounds have stress on the other parts of the words they’re in.

One very common mispronunciation of long sounds is between these two words:

- かわいい

- こわい

かわいい means cute. こわい means scary. Many new learners mix the two up and call people scary when they mean to say they’re cute. Hear the difference? Now you won’t make this mistake!

Double Consonants

While it doesn’t look like there are two consonants here, we write them that way in English. This means the consonant takes up extra time and sounds like a pause is happening before it. This is called «gemination.»

- きっぷ

- ちょっと

- がっこう

Don’t mix these two up!

- ようか

- よっか

One is a long sound and the other is a double consonant. Can you hear how different they sound? One means eight days, and the other means four days—you definitely don’t want to get those wrong.

You can also hear this when ん and なにぬねの meet, but because ん is our special exception symbol, this isn’t represented with っ.

- てんのう

Dropping す ち and し

One of the first things new learners are corrected on is their pronunciation of です and ます. Looking at them, it seems straightforward: combine the two sounds, and you get the pronunciation, but it isn’t so simple.

The す sound has a habit of dropping its vowel う. This is called «devoicing.»

- です des

- ます mas

- すき ski

It’s especially common at the end of a word or before certain consonants.

And す isn’t the only sound that gets devoiced. ち and し are other common offenders.

- しち

- わかりました

- すずきさん

Can you hear how short they sound?

Nasal が

This is a regional change, but it’s not uncommon, especially if you spend time with people older than you. Certain areas of Japan change the g sounds of がぎぐげご to the nasal velar stop you know as ん. Let’s listen to a man with this accent, pay close attention to how nasal the g sounds get.

- ながい

- つぎ

- あげる

It may sound like these words are being pronounced wrong, but they’re not! It’s just another variation that pops up from time to time.

Pitch and Speaking Japanese

If you’ve ever tried speaking Japanese to a Japanese person, and they didn’t understand you even though you definitely said the right words, there is a high chance it’s your pitch that threw them off.

The final ingredient to pronouncing Japanese words correctly is pitch.

Japanese is not like English—it does not have stress or emphasis that determines how to pronounce each word. Nor is it like Mandarin, as it does not have tones that denote meaning. But it’s not a «flat» language either, which seems to be a common assumption and mistake even among teachers.

Pitch in the context of speaking Japanese is similar to what we talk about in singing a song. These are the notes that go up and down on a scale. While the exact notes aren’t always the same and can differ depending on where in Japan you are, copying the pitch accents of those around you will help you sound like a native.

If you’ve ever tried speaking Japanese to a Japanese person, and they didn’t understand you even though you definitely said the right words, there is a high chance it’s your pitch that threw them off.

While we won’t go into everything here, because Japanese pitch accent can get pretty technical, let’s cover some of the basics.

Pitch Accent Patterns

We talk about pitch in Japanese in terms of highs and lows. The actual starting position differs based on your natural speaking voice and range. Think of it this way: the tune is the same, but the key changes based on the instrument (i.e. the voice of the person).

There are a few basic rules that can help you immensely in learning how to pronounce words like a native:

- If a word starts low, the next sound goes high

- If a word starts high, the next sound goes low

- Most long words go low again near the end

There are many ways to look up each individual word to make sure you’re pronouncing it the correct way, which our friend Dogen went over a while back. If you really want to get into it, I’ll leave you in his hands.

We made some handy examples of almost all of the pitch accent combinations you’ll hear in Japanese. Listen to each one, and see if you can hear the patterns as they’re indicated in the «Pitch Pattern» column with just two letters:

H: High

L: Low

Note: The letter in parentheses shows the pitch of the particle that follows the word, and isn’t included in the audio. So for example, the LH(H) pitch pattern for 水 tells you that 水 itself has a low pitch followed by a high pitch, and that the は in 水は — or the を in 水を — would have a high pitch.

| Pitch Pattern | Japanese | Reading | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L(H) | 名 | な | |

| LH(H) | 水 | みず | |

| LHH(H) | 会社 | かいしゃ | |

| LHHH(H) | 大学 | だいがく | |

| LHHHH(H) | 中国語 | ちゅうごくご | |

| LHHHHH(H) | 見物人 | けんぶつにん | |

| LHHHHHH(H) | 五十音順 | ごじゅうおんじゅん | |

| LHHHHHHH(H) | いい加減にしろ | いいかげんにしろ | |

| H(L) | 木 | き | |

| HL(L) | 秋 | あき | |

| HLL(L) | 電気 | でんき | |

| HLLL(L) | 文学 | ぶんがく | |

| HLLLL(L) | シャーベット | しゃーべっと | |

| HLLLLL(L) | ケンモホロロ | けんもほろろ | |

| HLLLLLL(L) | 呉越同舟 | ごえつどうしゅう | |

| LH(L) | 花 | はな | |

| LHL(L) | お菓子 | おかし | |

| LHLL(L) | 雪国 | ゆきぐに | |

| LHLLL(L) | 普及率 | ふきゅうりつ | |

| LHLLLL(L) | お巡りさん | おまわりさん | |

| LHH(L) | 男 | おとこ | |

| LHHL(L) | 歳時記 | さいじき | |

| LHHLL(L) | 山登り | やまのぼり | |

| LHHLLL(L) | 金婚式 | きんこんしき | |

| LHHLLLLL(L) | 副大統領 | ふくだいとうりょう | |

| LHHH(L) | 弟 | おとうと | |

| LHHHL(L) | 小型バス | こがたばす | |

| LHHHLL(L) | 国語辞典 | こくごじてん | |

| LHHHLLL(L) | 私立大学 | しりつだいがく | |

| LHHHH(L) | 桃の花 | もものはな | |

| LHHHHL(L) | 炭酸ガス | たんさんがす | |

| LHHHHLL(L) | 幼年時代 | ようねんじだい | |

| LHHHHLLL(L) | 大学院生 | だいがくいんせい | |

| LHHHHH(L) | 十一月 | じゅういちがつ | |

| LHHHHHL(L) | お願いします | おねがいします | |

| LHHHHHLL(L) | 自動販売機 | じどうはんばいき | |

| LHHHHHH(L) | 携帯ストラップ | けいたいすとらっぷ | |

| LHHHHHHHHH(L) | 宜しくお願いします | よろしくおねがいします |

In no universe do you ever need to memorize these patterns. They’re just here to give you a feel for how Japanese words naturally rise and fall. Messing them up a little bit probably won’t hurt anything, and Japanese people will almost always know what you mean, even if you don’t get the pitch quite right.

However, if you nail your pitch, you’ll sound more like a native than the average second-language Japanese speakers out there.

Same Spelling, Different Pitch

There are a few cases where Japanese words seem to share the same pronunciation, but actually have different pitch accent patterns.

| Pitch Pattern | Japanese | Reading | English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL(L) | 箸 | はし | Chopsticks | |

| LH(L) | 橋 | はし | Bridge | |

| HL(L) | 神 | かみ | God | |

| LH(L) | 紙 | かみ | Paper | |

| LH(L) | 髪 | かみ | Hair | |

| LH(H) | 酒 | さけ | Alcohol | |

| HL(L) | 鮭 | さけ | Salmon | |

| LH(H) | 飴 | あめ | Candy | |

| HL(L) | 雨 | あめ | Rain |

These little differences are where knowing pitch accent can really help you sound like a real natural!

Why not try and see if you got it? We made a listening test with the above words in sentences. Download it below by joining our mailing list.

Download Pronunciation Listening Test by signing up to the Tofugu newsletter

Warning: Remember that accents change depending on where you are and where the people you’re talking to grew up. There is no «one accent» that all of Japan shares, just like how there are tons of different ways to pronounce words in English.

Pronouncing Phrases and Sentences

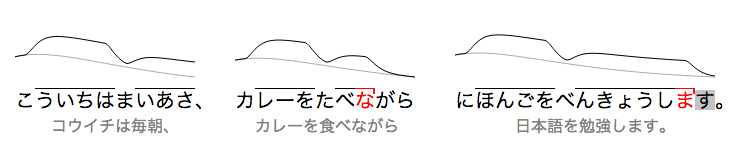

Pitch is also important when you combine these words into longer phrases and finally sentences. The trend in Japanese is that phrases start high and gradually go lower. Phrases are usually broken up by particles and punctuation, letting you take a breath and build back up again.

Let’s look at some examples of how pitch builds and falls, first with some phrases, and then with full sentences.

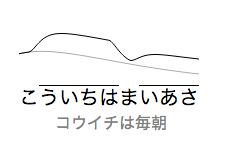

- コウイチは毎朝

- Every morning Koichi

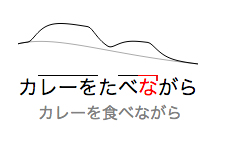

- カレーを食べながら

- while eating curry

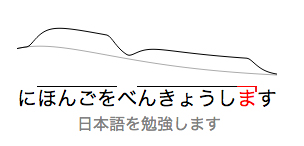

- 日本語を勉強します

- studies Japanese

Can you see and hear how each phrase starts high and slowly lowers? Let’s look at the entire sentence.

- コウイチは毎朝、カレーを食べながら日本語を勉強します。

- Every morning Koichi studies Japanese while eating curry.

Each phrase is separate even in one sentence. Here we have two pauses, once after the comma, once after ながら, a grammar point that means «while doing.»

Each word still has its own pitch accent, but they blend together a bit in each phrase. Letting you pause at the right places does a few important things for your Japanese pronunciation:

- You have time to think about the next phrase. If you try to say one long string of words it’s really easy to get tongue-tied. Take a breath here and reset.

- It makes what you’re saying clear and easy to understand. If you blurt out a long sentence it may be hard for native speakers to understand what you’re saying, because…

- Native speakers pause at these parts too! We have pauses like this in English too, so make sure you aren’t talking like a speed demon for no reason.

Okay, let’s look at another sentence.

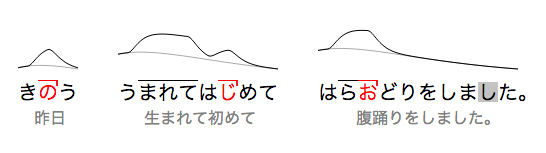

- 昨日

- Yesterday,

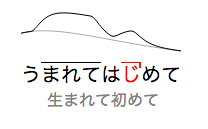

- 生まれて初めて

- for the first time in my life

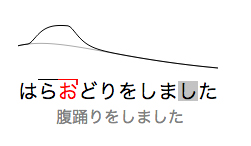

- 腹踊りをしました

- I did Japanese belly dancing

- 昨日生まれて初めて腹踊りをしました。

- Yesterday, I did Japanese belly dancing for the first time in my life.

Once again we have two pauses, once after 「昨日」and once between the two phrases 「生まれて初めて」 and 「腹踊りをしました」. Let’s look at and listen to a few more sentences.

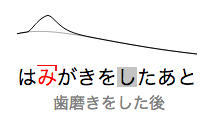

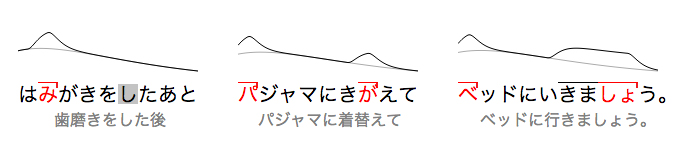

- 歯磨きをした後

- After you brush your teeth

- パジャマに着替えて

- change to your jammies

- ベッドに行きましょう

- and go to the bed

- 歯磨きをした後パジャマに着替えてベッドに行きましょう。

- After you brush your teeth, change to your jammies, and go to the bed.

We see the same pattern here as we did in the sentence before it. After you「歯磨きをした後」 you 「パジャマに着替えて」 and then 「ベッドに行きましょう」.

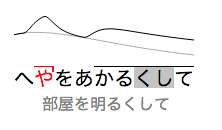

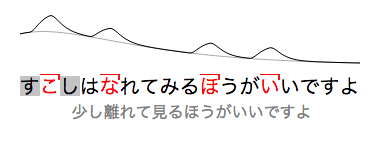

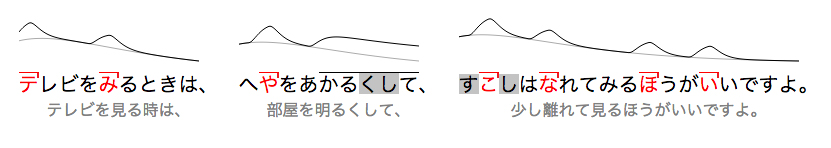

- テレビを見る時は

- When you watch TV

- 部屋を明るくして

- you should keep the lights in the room on

- 少し離れて見る方がいいですよ

- and watch it from from a bit of a distance

- テレビを見る時は、部屋を明るくして、少し離れて見る方がいいですよ。

- When you watch TV, you should keep the lights in the room on and watch it from from a bit of a distance.

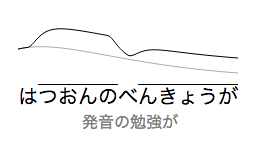

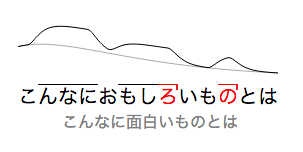

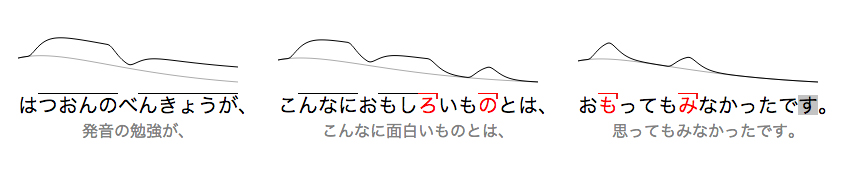

- 発音の勉強が

- learning pronunciation

- こんなに面白いものとは

- would be this interesting

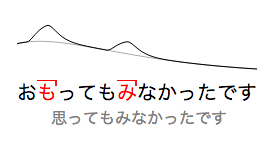

- 思ってもみなかったです

- I never thought that

- 発音の勉強が、こんなに面白いものとは、思ってもみなかったです。

- I never thought that learning pronunciation would be this interesting.

If you want to ace a Japanese speaking contest, using these types of pitch patterns and pauses can be the difference between a win and an «honorable mention.»

While not all sentences are nicely broken up like this, these rise and fall patterns and pauses are extremely common in spoken Japanese. And if you want to ace a Japanese speaking contest, using these types of pitch patterns and pauses can be the difference between a win and an «honorable mention.»

Each of the breakdowns above were made using a wonderful website called Prosody Tutor Suzuki-kun, made by the people behind the Online Japanese Accent Dictionary. Their pronunciation studies and tools can be invaluable when it comes to learning how to pronounce words, phrases, and sentences in Japanese.

If you’d like to use their tools, specifically for parsing out longer sentences like those above, they have a small English guide here. Eventually, you’ll outgrow it, picking up the cadence and pitch of the Japanese speakers you interact with. But until then, use tools like this to impress your Japanese teachers, tutors, and friends with how natural your pronunciation sounds.

For the fun of it, we also recorded some «natural» versions of these sentences as well, so you can hear the difference between the radio and speech friendly accent above and the everyday conversational accent below. If you can say these sentences with the same speed, accent, and tempo, you’ll be speaking like a Japanese pro in no time.

- コウイチは毎朝、カレーを食べながら日本語を勉強します。

- Every morning Koichi studies Japanese while eating curry.

- 昨日生まれて初めて腹踊りをしました。

- Yesterday, I did Japanese belly dancing for the first time in my life.

- 歯磨きをした後パジャマに着替えてベッドに行きましょう。

- After you brush your teeth, change to your jammies, and go to the bed.

- テレビを見る時は、部屋を明るくして、少し離れて見る方がいいですよ。

- When you watch TV, you should keep the lights in the room on and watch it from from a bit of a distance.

- 発音の勉強が、こんなに面白いものとは、思ってもみなかったです。

- I never thought that learning pronunciation would be this interesting.

We also recorded a podcast about Japanese pronunciation where we ask more questions, mess up (for your education, of course), and make a ton of mouth noises into the mic. You can subscribe to The Tofugu Podcast for more on the Japanese language and Japan on Apple Podcasts, Soundcloud, or wherever you get your podcasts.

The table below contains a list of the Japanese words with audio. To hear the audio, click GET FLASH TO HEAR AUDIO shown at the beginning of the list of words. This will help you read and also hear the words the way they’re pronounced by a native. Simply hover with your mouse over each image to hear the pronunciation. You can also listen to the whole audio by pressing the play button on the audio player below. You can check our Learn Japanese page for other lessons.

We hope you enjoyed learning the Japanese words. You can also visit our Learn Japanese page for other grammar and vocabulary lessons.

|

Menu: |

Alphabet |

Phrases |

Adjectives |

|

Japanese Homepage |

Numbers |

Nouns |

Vocabulary |

|

Learn Japanese |

Plural |

Videos |

Practice |

The links above are only a small sample of our lessons, please open the left side menu to see all links.

We’re now at the final section of hiragana characters and the individual sounds that they represent. In this lesson you will learn what the combination sounds in Japanese are and how to form them.

This part gets interesting as we once again take the basic hiragana that you’ve already learned and alter them slightly in order to represent some new consonant and vowel combinations.

However, we do it differently than we did the first time. Instead of adding dashes or circles to the basic kana, we are going to add more kana. Although they are smaller (and cute!).

How To Make Combination Kana

This part can kind of be thought of like a mathematical formula. Here’s what I mean by that:

Take any hiragana that is a Consonant + the い [i] vowel, and combine it with one of the three [y] kana: や, ゆ, or よ.

き and や become きゃ = kya

き and ゆ become きゅ = kyu

き and よ become きょ = kyo

Note that when this happens, the [i] sound from the first kana disappears. What this means is that きゃ = kya is a single sound.

[kya] is the correct way to say it – It’s just one syllable.

[ki-ya], which is two syllables, would be incorrect.

This might feel a little weird for you at first, so just be sure to pay extra close attention when you listen to it and then try to make a single sound when you produce it.

Also, something to note is that, you will probably have noticed that the [y] kana in these combo-kana are only half of their normal size!

This shows that they belong to the normal size hiragana that immediately precedes them.

Even though きゃ is created by using a normal sized kana in conjunction with a half-sized kana, it is still considered as one single mora.

What Is A Mora?

In the last lesson I told you that I would go into more details on what a mora is, and I think now is a good time to do that.

A “mora” is defined as “a unit in phonology that determines syllable weight” but we can make it easier to understand when it applies specifically to Japanese.

To make things simple (and useful) we can say that a mora is a single kana character and its associated sound.

That would mean that き [ki] is a single mora and きや [ki ya] is two mora.

When it comes to these new combination sounds, such as きゃ [kya] we are essentially taking two morae and merging them into a new single mora.

Since the Japanese language using the consonant + vowel combination so often, we might initially think that mora and syllables are the same thing, but once we get into the section of this course where we study the sounds in complete words, we will see that a syllable can actually encompass several morae.

So think of “mora” as a single phonetic character in Japanese, and remember that these combination kana are just one mora.

They Are Called “You-On” In Japanese

I hope that it makes sense now why I’ve been calling them “combination hiragana” from the way they are constructed.

However, they are actually called “you-on” in Japanese which translates as “contracted sound.”

You might recall the daku-on and handaku-on from before and notice a pattern right at the end of these words. They all end with “on” which is actually the Japanese word for “sound.”

There are a total of eleven groups. Here are the first six groups now.

きゃ = kya

きゅ = kyu

きょ = kyo

And of course here are the voiced counterparts as well.

ぎゃ = gya

ぎゅ = gyu

ぎょ = gyo

The [y] sound is changed to a [h] sound when the first kana used is the し [shi] character.

しゃ = sha

しゅ = shu

しょ = sho

It changes once again to a [j] sound when じ is used, which is the voiced counterpart to the above し.

じゃ = ja

じゅ = ju

じょ = jo

When we use ち we actually get the [h] sound again.

ちゃ = cha

ちゅ = chu

ちょ = cho

Thankfully, from here on out it’s all [y] sounds with these you-on. We will see the next group now and then all five remaining groups after some example words.

にゃ = nya

にゅ = nyu

にょ = nyo

Some Example Words

Content goes here.

きょねん = Last year

かいしゃ = Company

にゃん = Meow (the sound a cat makes)

としょかん = Library

じゅんび = Preparation

おちゃ = Green tea

ぎょせん = Fishing boat

Be Careful About These Sounds

Now here’s a question for you to ponder: “Will a [y] hiragana always fuse with a preceding Consonant + [i] kana?”

The answer is no.

There will occasionally be times when they do not combine, and are instead two separate sounds. I wouldn’t say that it’s common, but it does happen.

The tricky thing is that, at first, it can be kind of hard to distinguish the difference between these two situations. I’d like to show you what I mean.

Take a look at these next two words and see how close they sound to one another, and yet they are still different:

The below sounds are #1 [sha], and #2 [shi-ya]:

- しゃしん = Picture

- しや = Outlook

Did you catch the difference between the しゃ [sha] sound in the first word and the しや [shiya] in the second word. This ought to help you tell the difference between the combination sounds and regular ones.

If you can’t quite tell the difference yet, just be aware that it exists and listen a few extra times to help train your ears.

It also helps if you practice making the two sounds yourself. Try saying しゃ [sha] which is one mora, and then しや [shiya] which is two morae, a few times.

The Rest Of The You-on

First we’ll start with the [h] sound in combination with [y].

ひゃ = hya

ひゅ = hyu

ひょ = hyo

And the Daku-on version.

びゃ = bya

びゅ = byu

びょ = byo

And the Handaku-on version.

ぴゃ = pya

ぴゅ = pyu

ぴょ = pyo

The [m] is pretty simply as well.

みゃ = mya

みゅ = myu

みょ = myo

Finally we get to the tricky one.

りゃ = rya

りゅ = ryu

りょ = ryo

Special Notes On The [ry] Group

There are two situations that most English speakers struggle with when it comes to creating these りゃ, りゅ, and りょ sounds.

The first one I have talked about a little bit where a person creates two separate sounds [ri-yo] one after the other, rather than the single sound that is correct [ryo].

I would say that this is the most common struggle, and just being aware of it usually helps solve it.

The other problem people have is that they don’t hear that initial [r] sound at all and pronounce it as just [yo] when again, the correct sound is [ryo].

This second one is very subtle and you have to pay close attention so that you can catch it when others are talking.

There are two ways I would recommend you practice these sounds in order to help get ahead of these potential problems.

The first way is to practice making two sounds as separate morae followed immediately by the one combination sound. You can do it slowly at first in order to get a good feel for it before then speeding up to a normal pace.

り – や [ri-ya] and then りゃ [rya]

り – ゆ [ri-yu] and then りゅ [ryu]

り – よ [ri-yo] and then りょ [ryo]

The point of this exercise is to feel and hear how they are different from one another so that you can get used to them.

The other way to practice making the correct sound is to start with the tip of your tongue touching the top of your mouth (similar to the [r] group from before) and then try pronouncing the [y] sounds and notice how this is different from just the normal [ya-yu-yo] sounds where your tongue lays flat in your mouth the entire time.

This ought to help train you to make the three [ry] sounds correctly and keep it distinct from any other sounds that are close to it, but not quite the same.

Again, these are tricky sounds for English speakers so the best way to overcome them is to first be aware of them, and then do a lot of practice listening and repeating.

And remember to go easy on yourself. This isn’t something that you need to get perfect right away. The skill will come in due time the more you play with the language.

More Example Words

ひゃくまん = One million

ぴゅぴゅ = (the sound of) Whistling of wind

りゃくご = Abbreviation

りょかん = Ryokan – A Japanese style inn

Part 1 Complete!

Congratulations, you have now completed the first part of this course!

You now have a solid understanding and exposure to the individual sounds in Japanese. In addition to that, you can now read and write hiragana which is the first writing system in Japanese and a visual representation of these sounds.

In the second section of the course we are going to explore the sounds that only appear within complete words.

This next part ought to be fun, as it will open the door further on your understanding and mastery of the sounds of Japanese.

But before we get to that, let’s do one final review on everything that we’ve covered so far. I am also going to give you a complete chart of these hiragana (free!) that you can download and use whenever you want to.

Go to the Table of Contents

Go to the next lesson

A very important (and often underrated) aspect of Japanese that will help you communicate effectively is good pronunciation.

Getting your tongue around a new language can be hard work, but the reality is that proper pronunciation is essential to speaking.

If you can speak clearly, you will be understood — even if your grammar and vocab aren’t perfect.

The opposite is not true, however, as perfectly formed sentences mean nothing to a person if they can’t understand the sounds coming out of your mouth.

Good pronunciation can also greatly improve your confidence, which means you’ll be more willing to put yourself out there and speak as often as possible.

Like all physical skills, the key to good pronunciation is simple…

Practice!

You can’t train your tongue to shape the right sounds by reading about it. The muscles need to be developed, and your ears need to be trained to identify the subtle differences too.

Although this does generally get harder with age (part of the reason immigrant kids usually have much better pronunciation than their parents), with practice, it can still be learnt.

Quite simply, the more you do it, the easier it gets, and the more natural you will sound.

Below is my detailed guide to Japanese pronunciation. It includes a thorough explanation of all the different sounds in the language, as well as audio for each sound and a few useful words to practice with.

Select which characters to display:

Select whose voice to play:

To begin with, Japanese has only five vowel sounds. While English only has five vowels, they are each pronounced differently when used in different combinations with other letters, bringing the total number of unique vowel sounds up to around 20, depending on a person’s accent. Compared with this, the five sounds in Japanese are easy to learn.

Here are the five vowel sounds:

(Click to play audio)

These five vowels are also the first five “letters” of the «syllabary», the Japanese equivalent of the alphabet. Together, they are often referred to as the “a-line”.

In speech and writing, each of these sounds are used on their own or in combination with consonant sounds to produce other “letters”. For example, the first consonant sound is a “k” sound, but this can only be written or spoken

in combination with one of the above five vowel sounds.

As such, the next five “letters” in the syllabary after the a-line are:

As you have probably guessed, these five sounds can be referred to as the “ka-line”.

It is important to remember that there is no such thing in Japanese as a “k” on its own, and this is the same for all other consonant sounds, with the exception of “n”, as will be explained shortly.

After the ka-line, the pattern continues, starting with “sa” and followed by “ta”, “na”, “ha”, “ma”, “ya”, “ra” and “wa”. There are, however a few exceptions to this basic pattern, so we will now look at each of these lines one by one.

The exception here is that the second sound is “shi”, not “si”.

Pro tip: When typing using IME or similar Japanese language input tools, you do not need to type the «h» to get 「し」 — «si» will do the job and save you a fraction of a second. The same goes for other similar exceptions below, such as «chi» and «tsu».

The exceptions here are the “i” and “u” variations, where “ti” is pronounced “chi”, and “tu” is pronounced “tsu”, as in the word “tsunami”.

No exceptions here. Next:

The third sound here is not a “hu” sound but a “fu” sound, as in Mt. Fuji. It is, however, a lighter sound than the English “f ”, and sounds a bit like the sound you might make when unsuccessfully trying to whistle. Your bottom lip should not touch your teeth.

Also, note that 「は」 is pronounced «wa» when used as a particle. This may seem confusing at first, but the particle 「は」 is so common that it shouldn’t take long before you are able to recognise when it is a particle and when it is just part of another word. To learn more about particles and the role they play in Japanese sentences, check out my article on Japanese sentence structure.

Again, no exceptions. Easy.

The ya-line only has the “a”, “u”, and “o” sounds, but is otherwise quite straightforward. The “yi” and “ye” sounds were used once upon a time, but have since died out of the language. As a result, the Japanese currency today is pronounced “en” in Japanese, not “yen”.

Although there are no exceptions in the ra-line, the «r» sound is unquestionably the hardest sound for native English speakers to master. It is usually written as an “R” in romaji, but the sound itself is much lighter than the English “R”, somewhere between an “R” sound and an “L” sound. This is why Japanese people often struggle to distinguish between “R” and “L” when learning English — they use the same sound to cover both letters when speaking English.

The ra-line sounds are achieved by flicking your tongue lightly against the roof of your mouth. Of course, descriptions like this are hard to implement in practice, so like all other sounds, the best way to learn to pronounce the ra-line correctly is to listen and practice repeatedly until your tongue builds up the necessary muscles to make the sound effortlessly.

Although difficult, this is definitely worth the time, as correct pronunciation of the ra-line will make your Japanese sound much better to a native speaker’s ears, and this alone can earn you lots of respect.

This line only has the “a” and “o” variations, and the “w” sound is effectively silent in the case of “wo”. The “wo” therefore sounds the same as the “o” from the a-line, but they are used differently in writing and are not interchangeable. Essentially, «wo» is only ever used as a particle, some examples of which can be seen in my other articles, such as this one on sentence structure or this one about word order.

Lastly, we have this:

This “n” is the only consonant that stands alone without a vowel sound attached. It is slightly different to the “n” sound produced in the na-line, although you can get away with a regular “n” sound in most cases.

It is important to note that this “n” sound should always be pronounced as its own syllable, and not blended into other sounds. For example, the name “Shinichi” is actually made up of the sounds shi-n-i-chi (しんいち), with the “n” sound being the lone “n”, not a part of “ni”. This name should therefore be pronounced with a distinct separation of “shin” and “ichi”.

There are a few ways to differentiate this “n” sound from na-line sounds when writing in romaji, with my preferred option being “n’” (“n” followed by an apostrophe). This is only really necessary, however, when the «n» is followed by an a-line sound.

Similarly, when “n” is followed by a na-line character, it is usually written as “nna”, “nni”, etc., to show that there is an “n” sound followed by a separate na-line sound. For example, the commonly known Japanese word for “hello”, sometimes spelled “konichiwa”, actually contains this “n” followed by “ni”, and should therefore be written as “konnichiwa”.

We have now looked at all of the sounds that appear in the main part of the syllabary, but there are more! There are also a couple of important combinations and other points that are vital to achieving correct pronunciation in Japanese which we will cover soon.

But first, we have to look at…

Voiced variations

There is another set of «letters» that are strongly related to some of the sounds introduced above as they are, in Japanese terms, simply a transformation of those sounds.

The first line that this applies to is the ka-line. By adding two small lines, known as «dakuten» or «ten-ten», to the upper right of each of the ka-line characters, the hard “k” sound changes into a softer “g” sound as follows:

か ka → が ga

き ki → ぎ gi

く ku → ぐ gu

け ke → げ ge

こ ko → ご go

With just two small lines added to each character, we essentially have a new consonant sound.

These altered characters, however, do not appear in the main syllabary, as they are considered simply as variations of the ka-line. Why? Because the “k” sound and the “g” sound are essentially the same except for one small difference — the “g” sound is voiced, while the “k” sound is not.

If you’re not sure what a voiced or unvoiced sound is, say aloud the English “k” sound alone without a vowel, and compare this with what happens when you do the same with an English “g”. You should notice that your mouth moves in much the same way, but while you don’t use your voice for the “k” sound, you do for the “g”. This is because “g” is a voiced consonant, whereas “k” is not.

So, in Japanese, the unvoiced consonant sounds — that is, all sounds in each of the ka-, sa-, ta- and ha-lines — can be altered to create a voiced sound that is written in a similar way to their unvoiced counterparts. The other lines (na, ma, ya, ra and wa) don’t have these because these sounds are already voiced.

Additionally, in some cases, words that normally use the unvoiced sound (eg. the “k” sound) use the voiced sound (eg. “g”) instead when combined with other words, as it may be easier to say. For example, the number “three” is “san” and the word for “floor” (of a building) is “kai”, yet the third floor could be referred to as “san gai”. This kind of adaptation can be seen all throughout the language.

Of course, like the main sounds, there are a few exceptions among these voiced alternatives, so let’s look at each line individually.

Like the ka-line itself, these are nice and straightforward.

The one to note here is the second sound, which is pronounced “ji”, not “zi”.

The second sound, “ji”, is effectively the same as that from the modified sa-line above, and is rarely used. (If you need to type it, type «di», as typing «ji» will usually produce the za-line version).

The “dzu” sound is basically a heavier version of the “tsu” sound where the “dz” is a voiced version of the unvoiced “ts” sound. Just be careful, as repeating this sound may lead you towards a career in beat-boxing (sorry…).

This brings us to the last of these unvoiced sounds, the ha-line. However, this line is unique as it actually has two voiced alternatives — a “b” sound and a “p” sound.

Firstly, the “b” sound is made by adding two lines (dakuten) like the others:

Meanwhile, the “p” sound is achieved by adding a small circle (handakuten, or «half» dakuten, since it is considered half-voiced) instead of two lines, as follows:

As you can see, both the “b” and “p” variations of the ha-line are straightforward and don’t have any special sounds.

Combining sounds

We have now covered all of the individual sounds in Japanese (ie. the ones that just use a single kana character). Now let’s look at a few other sounds that are created by combining sounds together, plus a couple of important points to remember when speaking Japanese.

Small ya-line combinations

The three ya-line sounds can be combined with any of the sounds that end in “i” (except for “i” itself from the “a-line”) to produce another variation of sounds.

When written, the ya-line sounds are written smaller than regular characters. For example, “ki” + “small ya” would become “kya”, as if you were saying “ki” and then “ya” but without the “i” sound.

In the case of the sa-line, “shi” is the character with the “i” sound, so instead of “sya”, “syu” and “syo”, combining “shi” with the small ya-line characters produces the sounds “sha”, “shu” and “sho”. This idea also applies to some other sounds, as you will see below.

Here are all of the small ya-line combination versions of the main sounds:

Plus there are the voiced consonant variations:

Note that when a lone “n” sound is followed by a regular ya-line sound, it may be written in romaji as, for example, “n’ya” or «nnya». These should be pronounced as two separate sounds, and not joined together like the “nya”, “nyu” and “nyo” sounds above.

Small «tsu» (double consonants)

Some words, when written in Japanese, contain a small “tsu” inserted between other characters. When this is done, the word is pronounced with a tiny pause where the small “tsu” occurs, followed by an accentuation of the sound that follows the small “tsu”.

This must always be a consonant sound, and usually a hard, unvoiced or half-voiced sound (k, s, t, p). When written in romaji, the small “tsu” is instead written as a double letter.

Examples of words that have a small tsu/double consonant include Sapporo, Hokkaido, Nissan, and Nippon (an alternative to the word “Nihon”, meaning “Japan”, and often chanted by fans at international sporting events).

Even weighting of sounds, and no accents

When spoken, each kana character is given the same weighting, or an equal amount of time, and there is no accent placed on any of the characters.

To demonstrate this, consider the city of Osaka. Many English speakers will naturally put the accent on the first “a” and draw out this sound, so it sounds something like “Osaaka”.

In fact, when written in Japanese, Osaka is actually “おおさか” (”oosaka”). Since each kana character is given equal time, Osaka is actually a four character word pronounced “o-o-sa-ka”, with no accent anywhere, and the “o” sound making up half of the word.

The Japanese word for “hello” is similar. As mentioned earlier, this should actually be pronounced “ko-n-ni-chi-wa”, with a longer “n” sound than most English speakers normally say, and no accent on the first “i” (or anywhere else).

(Note that in hiragana, «konnichiwa» should be written as 「こんにちは」, since the 「は」is the particle pronounced «wa». It’s a particle because the word as a whole is a contraction of a longer phrase that is basically never used in full. The same is true for «konbanwa», which appears in the Practice Words section below.)

Another example might be “karate”. Like Osaka, the second syllable is usually accented by English speakers, but in fact equal time and weight should be given to each of “ka”, “ra” and “te”:

Elongated vowel sounds

When a sound is followed immediately by the same vowel sound, it is usually elongated as in the above example of “Osaka”. This applies whether the first of the repeated vowel sounds is paired with a consonant or not. For example, “toori”, meaning “street”, has an elongated “o” sound just the same as that in “Osaka”.

When written in romaji, my preferred method for expressing elongated sounds is with a line on the top of the vowel: ā, ī, ū, ē, ō. We can see this in «tōri» above.

The other main alternative is to repeat the vowel, effectively writing it as it would be typed in hiragana. In this case, however, note that an elongated «ō» sound is sometimes written as «ou», as this is how some such words are written in hiragana, as explained below.

When written in hiragana, elongated vowel sounds are usually expressed using the appropriate a-line character: おいしい (oishī = delicious), じゅう (jū = ten), etc. In the case of “o” sounds, however, the elongation of the “o” is often expressed with an 「う」 instead of an 「お」, such as in 「ありがとう」 (arigatō = thanks) and 「にちようび」 (nichiyōbi = Sunday).

In katakana, rather than using the a-line character, elongated vowel sounds are written with a 「ちょうおんぷ」 (chōonpu), or “long sound mark”: 「ー」. Examples of this can be seen in the words 「ケーキ」 (kēki = cake), 「コーヒー」 (kōhī = coffee) and 「スーパー」 (sūpā = supermarket).

Practice words

Of course, these sounds are only useful to us if we combine them to form words! Here are some useful words you can use to practice combining some of the sounds introduced above:

Good morning

ohayō gozaimasu*

おはよう ございます

Thank you

arigatō gozaimasu*

ありがとう ございます

You’re welcome

dō itashimashite**

どういたしまして

*»The «u» part of the «su» sound at the end of «ohayō gozaimasu» and «arigatō gozaimasu» are usually silent, hence these words end sounding like «mas».

**The «i» part of the «shi» sounds in «hajimemashite» and «dō itashimashite» are usually silent, hence these words end sounding like «shte».

Your Ultimate Japanese Pronunciation Guide

When learning a new language, pronouncing words correctly is one of the most important things, especially for practical communication. Learning Japanese pronunciation isn’t as difficult as learning Japanese grammar or its writing system, and if you can speak clearly, Japanese people will understand you even if your grammar and vocabulary aren’t perfect.

Compared to English, Japanese pronunciation is easier as it has less vowels and consonants than English does. Further, each syllable in Japanese has the same length and strength, as opposed to English where you have to be careful about which syllables to stress and speak strongly. As such, don’t be afraid to learn Japanese pronunciation. You can master Japanese pronunciation much faster than you think once you know the rules and tips.

Here’s our detailed guide to Japanese pronunciation to help you learn efficiently with JapanesePod101! Consider this our Japanese pronunciation key.

Ready to pronounce Japanese words like a native? Let’s get started!

Download Your FREE Guide to the Japanese Alphabet!

If you want to master the Japanese language and become fluent, you must learn the Japanese alphabet letters first. And you need physical worksheets to practice on.

This eBook is a MUST-HAVE for all Japanese learning beginners!

Download your FREE Japanese practice sheets PDF today and learn the Japanese language in no time!

This is a must-have guide for absolute beginners

Related Lessons

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Japanese Pronunciation

- Top 5 Mistakes to Avoid

- Vowel Sounds

- Consonant Sounds

- How to Improve Japanese Pronunciation

- Hard Words to Pronounce & How to Overcome

- Why is Correct Pronunciation in Japanese Important?

- Secrets to Learning the Correct Japanese Pronunciation

- How Japanesepod101 Can Help You Learn More Japanese

- How to Download Your Free Japanese eBook

- Related Lessons

1. Introduction to Japanese Pronunciation

It’s essential to know the Japanese writing systemin order to learn Japanese pronunciation efficiently and effectively. Once you master Hiragana / Katakana, you can pronounce anything in Japanese, as they’re the cornerstone of pronunciation in the Japanese language.

1- What is the Japanese Language Writing System?

The Japanese writing system is a combination of three different characters: Hiragana (ひらがな), Katakana (カタカナ), and Kanji (漢字). Kanji is Chinese characters and both Hiragana and Katakana are a syllabic grapheme. For learning Japanese pronunciation, Hiragana is the most important and thus we focus on Hiragana here. Later, we’ll also go more into comparing Japanese pronunciation to English.

Hiragana

Hiragana is the most basic Japanese writing system, the core Japanese alphabet. Japanese children and foreign Japanese learners start learning Japanese from here in order to read and write Japanese.

Hiragana consists of 46 basic characters which can represent all of the sounds in spoken Japanese, with a few variations which are closely related to some basic Hiragana and its sounds.

How to Read Hiragana

Unlike in the English alphabet, eachHiragana character represents one mora, the shortest syllable, and each character is read for the same length of time and spoken with the same strength. The characters represent the exact same sounds (please see the chart above) and all the Japanese sounds can be expressed by a single hiragana, or a combination of two hiragana letters.

All Hiragana end with a vowel (a, e, i, o, u).In this respect, Japanese pronunciation is far simpler than English pronunciation. Take the English alphabet “i,” for example. “I” itself is pronounced /aɪ/, but when it’s used in words such as “alive” and “ink,” the pronunciation of “i” changes.

On the contrary, the sound and pronunciation of Hiragana is the same, no matter what order the characters are in, or what combination of characters are in a word.

So once you master Hiragana, you’ll be able to pronounce all the Japanese words perfectly!

The first step to learn Japanese is to master Hiragana. When you can properly pronounce each Japanese words, your conversation skill will greatly improve.

2- How Many *Sounds* are there in Japanese?

As mentioned above, the basic sounds are represented by forty-six Hiragana characters.

However, there are fifty-eight other variations of sounds listed below. All are based on forty-six basic Hiragana.

1. Sound Variations

These are related to some of the basic Hiragana sounds. These characters are considered to be variations of the basic Hiragana, thus they don’t appear in the main syllabary.

For example:

When you look at the vertical “k” line in the Hiragana Chart above, there are “か (Ka), き (Ki), く(Ku), け (Ke), こ (Ko).” When adding “dakuten濁点” or two small lines to the upper right of each of the ka-line characters, the hard “k” sound changes into a softer “g” sound:

か (ka) → が (ga)

き (ki)→ ぎ (gi)

く (ku) → ぐ (gu)

け (ke) → げ (ge)

こ (ko) → ご (go)

Similarly, the lines of “s,” “t,” and “h” change into “z,” “d,” and “b” with dakuten as shown below.

When you add “handakuten 半濁点” or a small circle to the upper right of each of the h-line characters, the sound of “h” changes into the “p” sound:

は (Ha) → ぱ (Pa)

ひ (Hi) → ぴ (Pi)

ふ (Fu) → ぷ (Pu)

へ (He) → ぺ (Pe)

ほ (Ho) → ぽ (Po)

| あ段 | い段 | う段 | え段 | お段 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| が行 | が ガ ga |

ぎ ギ gi |

ぐ グ gu |

げ ゲ ge |

ご ゴ go |

| ざ行 | ざ ザ za |

じ ジ ji |

ず ズ zu |

ぜ ゼ ze |

ぞ ゾ zo |

| だ行 | だ ダ da |

ぢ ヂ ji |

づ ヅ zu |

で デ de |

ど ド do |

| ば行 | ば バ ba |

び ビ bi |

ぶ ブ bu |

べ ベ be |

ぼ ボ bo |

| ぱ行 | ぱ パ pa |

ぴ ピ pi |

ぷ プ pu |

ぺ ペ pe |

ぽ ポ po |

The number of sounds in Japanese pronunciation is not as many as those of English, so learning Japanese pronunciation is not so difficult if you know English.

2. Small Ya-Line Combinations

The three ya-line (や [Ya], ゆ [Yu], よ [Yo]) sounds can be combined with any of the sounds that end in い (i) (except for “い [i] ” itself from the “a-line”) to create another variation of sounds. In such cases, the ya-line sounds are represented by smaller characters of や (ya), ゆ (yu), よ (yo) instead of the regular-sized characters.

For example:

“き (Ki)” + “small ゃ (ya)” becomes “きゃ (kya).” When “ki” and “small ya” combine, the “i” sound disappears and it changes into the “kya” sound. The k-line becomes きゃ (kya), きゅ (kyu), and きょ (kyo).

Similarly, it applies to other sounds as shown below.

| や段 | ゆ段 | よ段 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| か行 | きゃ キャ kya |

きゅ キュ kyu |

きょ キョ kyo |

| さ行 | しゃ シャ sha |

しゅ シュ shu |

しょ ショ sho |

| た行 | ちゃ チャ cha |

ちゅ チュ chu |

ちょ チョ cho |

| な行 | にゃ ニャ nya |

にゅ ニュ nyu |

にょ ニョ nyo |

| は行 | ひゃ ヒャ hya |

ひゅ ヒュ hyu |

ひょ ヒョ hyo |

| ま行 | みゃ ミャ mya |

みゅ ミュ myu |

みょ ミョ myo |

| ら行 | りゃ リャ rya |

りゅ リュ ryu |

りょ リョ ryo |

| が行 | ぎゃ ギャ gya |

ぎゅ ギュ gyu |

ぎょ ギョ gyo |

| ざ行 | じゃ ジャ ja |

じゅ ジュ ju |

じょ ジョ jo |

| だ行 | ぢゃ ヂャ ja |

ぢゅ ヂュ ju |

ぢょ ヂョ jo |

| ば行 | びゃ ビャ bya |

びゅ ビュ byu |

びょ ビョ byo |

| ぱ行 | ぴゃ ピャ pya |

ぴゅ ピュ pyu |

ぴょ ピョ pyo |

Listening to the native’s pronunciation is very effective for learning. Please check out our YouTube channel of JapanesePod101.

2. Top 5 Mistakes to Avoid

Beginners in the Japanese language often make similar pronunciation mistakes. Japanese people may not understand you when you pronounce words incorrectly.

Here are the top five common mistakes in Japanese pronunciation.

Do you recognize any? Let’s get it fixed!

1- Shortening Double Vowels

While Japanese vowel sounds pronunciation are typically easy to grasp, this is one of the most common mistakes made by foreign learners. There are many Japanese words which have double vowels and a lot of beginners shorten long vowels. By shortening the double vowels, a word can have a different meaning despite sounding similar.

For example:

Tsūki (つうき:通気) — Ventilation / Air inflation

Tsuki (つき:月) — Moon

Hāku (はあく:把握) — Grasp / Comprehend / Understand

Haku (はく:吐く) — Vomit / Puke

When you omit the sound of “u” in Tsuuki, it becomes a different word (Tsuki) with a different meaning. There are many words that sound almost alike in Japanese like these, but be careful not to shorten vowels!

2- Not Pronouncing Vowels after Consonants, Especially for “Imported” Words

There are tons of “imported” words, or 外来語 (Gairaigo), in Japanese which are originally from foreign words, especially English. Although the sounds of these words are similar to the original ones, they became “Japanese” words and are pronounced in the Japanese way. If you pronounce them like they sound in English, most Japanese people unfortunately won’t understand you!

For example, check out this Japanese pronunciation list:

- hamu (ハム) — ham

- konpyūtā (コンピューター) — computer

- resutoran (レストラン) — restaurant

- koppu (コップ) — cup

- aisukurīmu (アイスクリーム) — icecream

- terebi (テレビ) — TV

- basukettobōru (バスケットボール) — basketball

- kurejitto kādo (クレジットカード) — credit card

In order to pronounce them correctly in Japanese, check how they’re spelled and listen carefully to how Japanese people pronounce them. Keep in mind that each Japanese sound is always “consonants + vowels,” except for ん (n).

3- Pronouncing Syllables too Strongly

If you’re a native English speaker, it’s natural to stress syllables in a word. But it’s not the case in Japanese! Each syllable has the same length and strength in Japanese, and a word sounds flat without stressed parts.

For example:

- The word “hamburger” is /ˈhæmˌbɜː(r)ɡə(r)/

- In English, “ha” is stressed and pronounced strongly.

- In Japanese, however, it’s pronounced “han-bā-gā,” with equal stress on all syllables.

- Japanese 3-Hiragana-name, such as Mariko, Naomi, Kaori, Takashi, Tomoki, Yutaka., etc.

- When native English speakers call Japanese 3-Hiragana-name, they tend to stress the latter syllables too strongly.

- In case of “Mariko,” ri is often stressed too strongly: “mah-REEEE-koh,” although it’s just “Ma-ri-ko” in Japanese, without stressing any particular syllable.

4- Japanese “R” is not English “R”

This might be very difficult and confusing for native English speakers (or native alphabet users).

In Japanese, the “R” sound in ら (ra), り (ri), る (ru), れ (re), ろ (ro), which compose the r-line in the Hiragana Chart, is not exactly the same as the English “R” sound. It actually sounds like something between the “R” and the “L” sound.

As the Japanese language doesn’t use Roman Alphabet, it’s hard to express “ら、り、る、れ、ろ” precisely in alphabet. However, alphabet “R” is commonly used to express “ら、り、る、れ、ろ” sounds nowadays, although it doesn’t represent the sound accurately.

Here are some tips for pronouncing “R” in ら (ra), り (ri), る (ru), れ (re), ろ (ro) in Japanese:

1) DO NOT ROLL your tongue for “R!”

Native English speakers tend to “roll” their tongue strongly when they pronounce “R” = “aarrrrr,” so that it sounds like it’s coming from deep in your throat. However, don’t roll your tongue with the Japanese “R” sound.

2) Pronounce “L” instead of “R.”

It sounds more similar to native Japanese pronunciation when you replace “R” with “L” in words.

Examples:

- Ringo (りんご) — Apple → “Lingo”

- Roku (ろく・6) — Six → “Loku”

- Rainen (らいねん・来年) — Next year → “Lainen”

- Rikai (りかい・理解) — Comprehension → “Likai”

5- Pronouncing the Little っ (Tsu) Incorrectly

This is probably one of the most difficult words to pronounce in Japanese for foreigners.

The small っ (tsu) , or 促音 (Sokuon), represents that the following consonant is a double consonant (except when the following consonant is “ch”). It denotes the gemination of the initial consonant of the kana that follows it.

Examples:

- Matte (まって・待って) — Wait → the sokuon represented by the doubled t consonant.

- Kippu (きっぷ・切符) — Ticket → the sokuon represented by the doubled p consonant.

- Gakkō (がっこう・学校) — School → the sokuon represented by the doubled k consonant.

- Shippai (しっぱい・失敗) — Failure → the sokuon represented by the doubled p consonant.

Many beginners don’t pronounce the small っ (tsu), or the sokuon with the doubled consonant, correctly

and tend to omit one consonant of the pair. For example, まって (matte) → まて (mate). This can change the meaning of a word, or cause it to not make sense.

Make sure you know the spelling of these words and how Japanese people pronounce them.

Knowing the correct spelling and how to read them helps you understand how to pronounce properly.

3. Vowel Sounds

1- Only 5 Japanese Vowels

Japanese pronunciation is far simpler than English pronunciation!

Japanese has only five vowels and these are terse vowels, pronounced clearly and sharply. Each letter almost always represents one single vowel sound. This makes Japanese vowel sounds pronunciation pretty simple to learn.

While English also has five vowels, they’re each pronounced differently when used in different combinations with other letters, bringing the total number of different vowel sounds up to around 20. In this respect, English vowel sounds cover all the Japanese vowel sounds.

Compared to English, Japanese vowels have only five basic sounds and they won’t change. Thus, they’re easy to learn!

|

あ |

い |

う |

え |

お |

|

a |

i |

u |

e |

o |

These five vowels are the first five “letters” of the syllabary (look at “a-line” in the Hiragana Chart in section 1). These are the most basic Hiragana and sounds of all.

- あ (a) represents the sound of “a” in “father.”

- い (i) represents the sound of “ee” in “feet.”

- う(u) represents the sound of “oo” in “food.” (”u” is pronounced with no forward movement of the lips.)

- え (e) represents the sound of “e” in “pet” (a short “e”).

- お (o) represents the sound of “o” in “on.”

Both in speaking and writing, each of these sounds is used on its own, or in combination with consonant sounds to produce other Hiragana or “letter.”

For example:

Look at the k-line in the Hiragana Chart.

The first consonant sound is a “k” sound, and by combining it with any of the five vowel sounds, it creates the k-line Hiragana and its sounds as follows.

|

か |

き |

く |

け |

こ |

|

ka (k + a) |

ki (k + i) |

ku (k + u) |

ke (k + e) |

ko (k + o) |

In the case of double vowels, such as 空気 (kūki)meaning “air,” the two vowels comprise two syllables, and they’re exactly twice as long as one vowel with equal stress. You may find that listening to the pronunciation yourself will help you grasp this better.

4. Consonant Sounds

1- 14 Japanese Consonants

There are 14 consonants in Japanese:

- /k/

- /s/

- /t/

- /n/

- /h/

- /m/

- /y/

- /r/

- /w/

- /g/

- /z/

- /d/

- /b/

- /p/