This article provides a list of common Japanese words that have different meanings from what you may have already learnt in Japanese classes!

うるさい

urusai

As you may know, うるさい in Japanese usually means “loud/noisy”. However, when it is used as “~にうるさい”, it means “be particular/picky/not easily satisfied about ~”. Its rationale is that if you harp on about your specific preferences about something, other people may find you a bit annoying and noisy (but it’s not a negative word at all!)

私はラーメンの味(あじ)にうるさい

I’m particular about the taste of ramen.

ヒモ

himo

ヒモ/ひも usually means “a string”, but also means “an indolent man who financially depends on his girlfriend excessively like a parasite and is reluctant to work by himself”, e.g. living in her house without paying the rent, or even asking her for an allowance to spend on gambling. This is a derogatory term for men who exploit and abuse their girlfriends financially, and therefore shouldn’t be used to describe those who stay home to manage their household and take care of their children instead of working outside.

私の彼氏を甘(あま)やかし過(す)ぎて、ヒモになってしまった。

I spoiled my boyfriend too much and he has become a ヒモ (a person who depends on me financially).

さくら

sakura

As you know, さくら (桜 in kanji) means “cherry blossom”. Oddly enough, however, when written in katakana (i.e. サクラ), it can also mean “a shill”: a person who pretends to be a real customer and promotes certain products or services. Note that サクラ can also mean “cherry blossom” depending on the context.

この口コミサイトにはサクラがたくさんいる

There are lots of shills on this review site

切れる

kireru

切れる is a basic Japanese intransitive verb that usually means “be cut” or “snap”, as in “ヒモが切れた” meaning “The string has been cut/has snapped”. However, it also means “run out” in a different context, as in “トイレットペーパーが切れているのに気がついた” meaning “I’ve just realised that the toilet paper has run out”. Furthermore, if it is used in the expression “~ が切れる” in which a noun denoting a date or period is put before が, it means “(something) passes the period”. For instance, “賞味期限(しょうみきげん)が切れた牛乳(ぎゅうにゅう)” means “The milk that has passed its best-before date.” and “チケットの有効期限(ゆうこうきげん)が切れた” means “The ticket has passed its valid date/has expired”. In a casual conversation, 切れる also means “get very angry/furious”, but in this case, it is more often written in hiragana and katakana, as in “キレる”, e.g. “彼はキレたら怖(こわ)い” means “He is very scary when he gets furious”.

See also

逆ギレ (gyaku gire) Meaning “Reversed Anger” in Japanese

滑る

suberu

The Japanese word “滑(すべ)る” usually means “to slip”, as in “滑って転(ころ)んだ” meaning “(I) slipped and fell”. But it is also used to describe when someone tries to tell a joke but nobody finds it funny, introducing a quiet and awkward moment.

(e.g.)

彼女を笑(わら)わせようとしたら完全(かんぜん)にすべった

I tried to make her laugh but completely “slipped”.

* One of my friends once gave me a useful tip on how to deal with the situation when you’ve accidentally “slipped”: look at something far away, pretending that you are distracted by it and don’t notice that your joke completely failed!

Besides, 滑る also figuratively means “to fail school entrance exams”. Therefore, when it snows in Japan, students preparing for those kinds of exams (= 受験生) pay full attention to their steps to avoid slipping on ice.

なめる

nameru

なめる usually means ‘to lick”, as in “自分(じぶん)の指(ゆび)をなめる” (lick my fingers), but it also means “underestimate/mock/look down on something or someone”, as in “彼の力(ちから)をなめるなよ” meaning “Don’t underestimate his power”. Well, actually there isn’t a direct relation between these meanings, but it may help you memorise them if you picture a person who mocks someone by sticking his/her tongue out, like Albert Einstein’s iconic photo (albeit this is probably not what he intended.)

くさい

kusai

くさい usually means “smelly/stinky”, but it also means “(someone’s act is) cheesy/corny/too much”, which means, in other words, their act is, well, sh*tty (and thus “smelly”). Not only a clichéd act, it also describes a corny line that makes you cringe a bit, like “君を愛するために僕は生まれてきたんだ”, meaning “I was born to love you”.

Incidentally, “嘘(うそ)くさい” is another idiomatic expression that literally means “(something) smells like a lie” and actually means “fishy”.

くさい演技(えんぎ)はやめて、本当(ほんとう)のこと私(わたし)に言(い)って?

Please stop doing your “smelly” act, and tell me the truth?

「君(きみ)以外(いがい)何(なに)もいらない」?よくそんなくさいセリフ言えるね!

“I don’t need anything but you”? How dare you can say such a “smelly” line!

この本(ほん)に書(か)いていることはなんか嘘くさい

What is written in this book is a bit fishy.

嫌い

kirai

嫌い usually means “dislike”, as in りんごが嫌い means “I dislike an apple”. In a formal context, however, it is also used as a noun meaning “a bad tendency”, as in “彼(かれ)は話(はなし)を誇張(こちょう)するきらいがある” meaning “He has a bad tendency to exaggerate his stories”. In the latter case, the word is often written in hiragana to avoid confusion.

引く

hiku

引く (ひく, hiku) usually means “draw/pull”, as in “ロープを引く (pull a rope)”. However, it is also used as a slang term meaning “be put off by something/someone”, i.e. when you feel like drawing back because you find something/someone cringeworthy and off-putting. For instance, you would 引く (hiku) when someone says some disgusting sexual jokes.

Refer to the previous post for related words and pronunciation of 引く:

引く (hiku) Meaning “Be Put off” as Japanese Slang

ブーメラン

būmeran

ブーメラン is a loanword from “boomerang” in English. However, as a slang term, it also refers to a hypocritical criticism that is thrown at others but also applies to the person who makes the criticism (i.e. a “look-who-is-talking” statement.). It’s called ‘boomerang’ because, after being thrown at others, it comes back to the criticiser like a boomerang.

More detailed explanations at:

Japanese Slang ブーメラン (Boomerang) Meaning “Hypocritical”

“A nation’s culture resides in the hearts and in the soul of its people.” ~ Gandhi.

Over the years, learning new Japanese words has evolved into a passion of mine. If I could sum up my findings so far, it’s that Japanese culture makes you aware of small details that were always there but didn’t necessarily notice before.

Despite researching my first trip to Japan to death as I do for all destinations I visit, I returned with the realisation that there is always so much more to learn (hence my multiple trips thereafter). Their language and absolutely beautiful Japanese words are no exception!

I now have an insatiable appetite to quash my curiosity and fascination with Japanese culture, religion and aspects of day-to-day-life. Learning through language is a great way to achieve this, and I love sharing all these findings with you throughout my Japan blog.

Not only have I categorised this list into beautiful Japanese words, I’ve also included motivational, meaningful, inspirational and untranslatable expressions. This comprehensive guide is a collection of my favourite Japanese words and phrases that have helped bring more meaning into my life – and I hope they will for you, too!

TIP: If you’d like to learn the correct way to pronounce the words and expressions in this article, my guide to Japanese for tourists explains exactly what you need to know for language learning (and includes a free cheat sheet, too!)

This post contains affiliate links, at no extra cost to you. I may earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Japanese words video

If you prefer to learn from a video, I’ve summed up this article in 45 seconds (if you can’t see it in the space below, simply disable your ad blocker:

Beautiful words in Japanese

Ikigai

生きがい

When browsing an airport bookstore, I first learnt this beautiful Japanese word when I saw this paperback ranking highly on the bestseller shelves. Intrigued by the blurb and promise, I excitedly bought the book and dove right into it.

What I didn’t realise was ikigai is the word used to describe the very passion that gets you out of bed in the morning; your reason for being. It’s a combination of what you’re good at, something you love and something the world needs. Just ask any centenarian in Okinawa why they still enjoy working everyday!

Japanese people believe everyone has an ikigai, they just need to find it. On completing the book, I recognised that this very blog you’re reading, right now, has been my ikigai since I launched it in 2017. My passion for sharing responsible travel tips, advice and my love of Japan with you is what I look forward to each and every day.

Ichi go ichi e

一期一会

This is one of the most insightful Japanese words I’ve had the pleasure of learning from an actual geisha. During my traditional tea ceremony in Kyoto, it was explained that ichi go ichi e has very strong ties to enjoying tea in Japan.

Translating to “once in this lifetime”, ichi go ichi e serves as a gentle reminder for us to treasure each individual moment as can never truly be replicated again.

Even if you invited the same people to enjoy tea at a later date, at the same time, wore the same clothes etc, aspects of the encounter would always differ to the original, such as conversation or weather.

This concept can be applied to each and every situation throughout life. Isn’t it fascinating?

Nakama

仲間

A nakama can be described as a very good friend that one considers family, even if they’re not related by blood. You never know, you might end up making a nakama when undertaking cultural experiences in Japan.

Perhaps it’s a friend you frequently see, or the kind of friend you only have the chance to catch up with once every few years in person as they live far away. But when you do, the bond of friendship is so strong it’s like all that time in between has never passed!

Do you have a nakama?

Wabi sabi

侘寂

It’s difficult to sum up the meaning of wabi sabi into a few short words. Deriving from Zen buddhism, in the simplest form it could be described as the acceptance of finding beauty in imperfections and the impermanence of things.

Finding beauty in flaws is a huge part of Japanese aesthetics. In a world where striving to achieve perfection is prioritised, it’s nice to see a contrasting perspective is also widely accepted throughout Japan. Perhaps more of us should view imperfections in this way? More about wabi sabi here.

TIP: A great example of wabi sabi is kintsugi, which I describe in more detail further down the page.

Natsukashii

懐かしい

Do you ever come across old items or photographs that warm your heart? Even the scent of perfume or candles can evoke particular memories. Natsukashii is that feel-good emotion of sentimentality when remembering back to a time you hold close to your heart.

I certainly feel this when I think back to my time swooning over cherry blossom petals bathing in the setting sun’s orange glow in Kawagoe!

Natsukashii differs from nostalgia in a way because it’s not the feeling of longing to return to that particular time. It’s simply feeling grateful to have had a particular experience in the past without the desire to return to that moment.

Kintsugi

金継ぎ

This beautiful practice is believed to date back to 15th century Japan. Kintsugi translates to “the art of broken pieces” whereby broken pottery was repaired with gold, rather than being discarded.

Filling the cracks with gold is an indication that flaws can be seen as a unique part of the object’s history, which adds to its overall beauty and character.

I recently learnt the brand Siletti has a range of kintsugi-style crockery that allow you to bring the look of this centuries-old tradition into your home in a modern way.

Motivational Japanese words

Ame futte ji katamaru

雨降って地固まる

If any nation were to claim ame futte ji katamaru as their unofficial motto, it would have to be Japan. As a country that has natural disasters such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to thank for its creation, the saying “after the rain, earth hardens” is quite fitting.

What this means is overcoming adversity builds character and resilience. It’s believed that after a storm, things tend to stand on more solid ground than they did before.

Just take the last 100 years for example. The people of Japan have endured the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the Great Kobe Earthquake of 1995 and the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 2011 resulting in a devastating tsunami and nuclear meltdown.

Aside from the ongoing cleanup from the 2011 Fukushima area disaster mentioned above, today you’d be forgiven for thinking each of these locations never endured such hardship – they’ve rebuilt stronger than before.

Ganbaru

頑張る

The Japanese word ganbaru can be used as an expression of encouragement. However, it can have several meanings, ranging from “to do more than one’s best”, “to stand firm”, “to endure”. It encapsulates having focus and determination to step outside your comfort zone and achieve goals.

To fully comprehend how to use ganbaru, this article goes into great detail!

Nanakorobi yaoki

七転び八起き

Translating to “Fall down seven times, stand up eight”, this has got to be one of my most favourite motivational Japanese words. It’s always a great reminder to never give up on your goals, no matter how many obstacles you encounter along the way.

Did you know Daruma dolls are said to be linked to the saying nanakorobi yaoki? Their rounded shape is symbolic of having a fighting spirit to overcome adversity. Representing good fortune and perseverance, Daruma dolls make the perfect Japanese souvenirs!

Hikari wa subete no yami no naki ni arimasu

光はすべての闇の中にあります

Translating to “There is light in all darkness”, this term is self-explanatory.

The English word equivalent would be “every dark cloud has a silver lining”, meaning out of a bad situation there is hope that good things can happen.

Meaningful Japanese words

Shinrin yoku

森林浴

In our fast-paced, digitally-connected world of bustling cities, the art of shinrin yoku plays a very important role in Japanese culture. Translating to “forest bathing”, these meaningful Japanese words help us remember to immerse ourselves in nature as often as possible to reconnect with our natural environment.

Believed to have healing properties and serve as a kind of preventative medicine, practicing shinrin yoku allows us to temporarily forget about our modern troubles, eye-straining screens and day-to-day nuances.

To awaken a sense of connection to nature, the aim is to to really slow down and use all our senses to take in the surrounding scenery… The sounds of birdsong; the motion of leaves swaying in the breeze; the smell of recent rains or nearby flowers. Without realising at the time, I was able to achieve this in the tranquil moss forests of Kyoto.

TIP: Interested in learning more about shinrin yoku and how it can help you, even if you don’t have any forests nearby? I can highly recommend this book by two of my favourite authors on Japanese culture.

Omotenashi

おもてなし

If you’ve visited Japan, has a Japanese local ever gone out of their way to assist you with something? Ladies, did you ever notice the basket beneath your chair in a restaurant to put your handbag whilst eating to prevent it getting dirty on the floor? Did you notice the taxi driver’s white gloves and the vehicle’s door opening automatically?

These are all examples of omotenashi – superb Japanese hospitality and attention to detail. This trait is one of the many things Japan is famous for.

Hospitality and respect are deeply ingrained into all aspects of everyday life in Japanese culture. It is not done for financial reward (such as tipping, because one of the don’ts in Japan is leaving a tip for service). It’s just expected.

While I can recall countless experiences of omotenashi during my visits to Japan over the years, it wasn’t until more recently I discovered there was a word in Japanese to encompass this. Say it with me now: o-mo-ten-a-shi!

Komorebi

木漏れ日

Meaning “sunlight filtering through the trees”, komorebi can be used to describe the way leaves and the sun’s glow interact with one another. Even a slight breeze causes leaves to manipulate the sun’s rays into dancing, angular patterns.

Komorebi always makes me think back to my half-hour walk through dense forest in Nagano to Jigokudani Snow Monkey Park. The best time to witness the monkeys playing is when the park opens, which is the perfect moment to witness komorebi.

The early morning mist slowly lifted as I journeyed along the track, revealing soft rays of sunlight flickering through the trees. Isn’t it such a beautiful word?

Inspirational Japanese words

Ukiyo

浮世

Can you remember back to a time where you lived in the moment, so much so you felt completely detached from life’s bothers? Felt so carefree, inspired, like the world was floating? Ukiyo is the word to describe this feeling, translating to “the floating world”.

Every time I visit Kyoto I’m reminded of ukiyo. I forget about my phone with its constant notifications and just be. With its beautifully preserved Edo-era streets, ancient wooden pagodas and incredibly landscaped gardens, it’s effortless for one’s mind to escape to a floating world in Kyoto.

TIP: My talented friend Lisa in Japan evokes the feeling of ukiyo so beautifully with her photography. If you love Japanese cherry blossoms, don’t resist taking a peek at our collaboration in my article about spending spring in Japan!

Datsuzoku

脱俗

Meaning “a break from habit or daily routine”, datsuzoku can be used to refer to freedom from the ordinary. It can also mean going against the grain to live a life unbound by convention.

The beauty of being able to travel internationally in previous years is a great example of this. Venturing to a new destination to temporarily experience how others live reminds me of datsuzoku. To be in a contrasting part of the world and witness others do something different to what I’d expect was always a welcome break from my usual daily routine.

I think this is how most of us felt before the events of 2020! I loved the freedom to book a ticket and fly to Japan when the opportunity arose, especially when I dedicated the time to undertake most of these day trips from Tokyo.

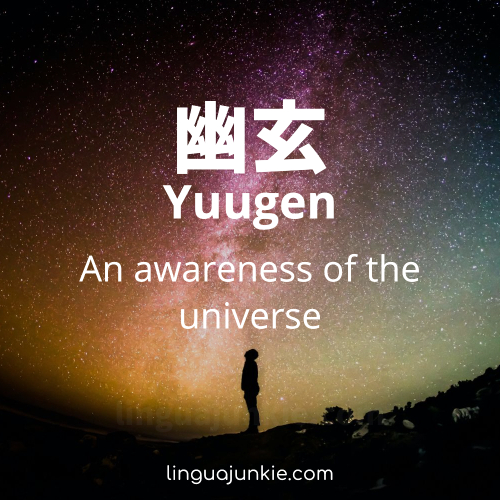

Yugen

幽玄

To put things bluntly, sometimes it’s ridiculously easy to get caught up in the daily grind we forget we’re all on a massive spherical rock hurtling through space at an unthinkable speed. Haha, think about it!

Do you ever take a few moments to stare at the moon and stars? Have you ever thought no matter where we are in the world, we all see the same moon? Yugen translates to “a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe”.

When I gaze into the night skies, I can’t help but think about what an incredible expanse space must be, our galaxy, and our place in the universe. Even if we don’t fully comprehend it, we’re all part of something much bigger than ourselves.

If you’re like me you’ve been reminded of yugen during your travels, especially to destinations steeped in history. Strolling through the centuries-old temples of Kamakura or adoring the gassho-zukuri farmhouses of Hida Folk Village in Takayama reminded me the same sun has risen and set on these structures, each and every day, for centuries. Isn’t that so humbling to realise?

Untranslatable and cool Japanese words

Tsundoku

積ん読

Tsundoku refers to “the act of buying books without reading them”; creating a collection of unread novels and the like. Do you know someone this aesthetic Japanese word could relate to? I’ve been guilty of this in the past!

Although if you do plan on buying a bunch of books to actually read, take a look at my detailed review of the best travel books for Japan to help get your future trip planning off to a brilliant start.

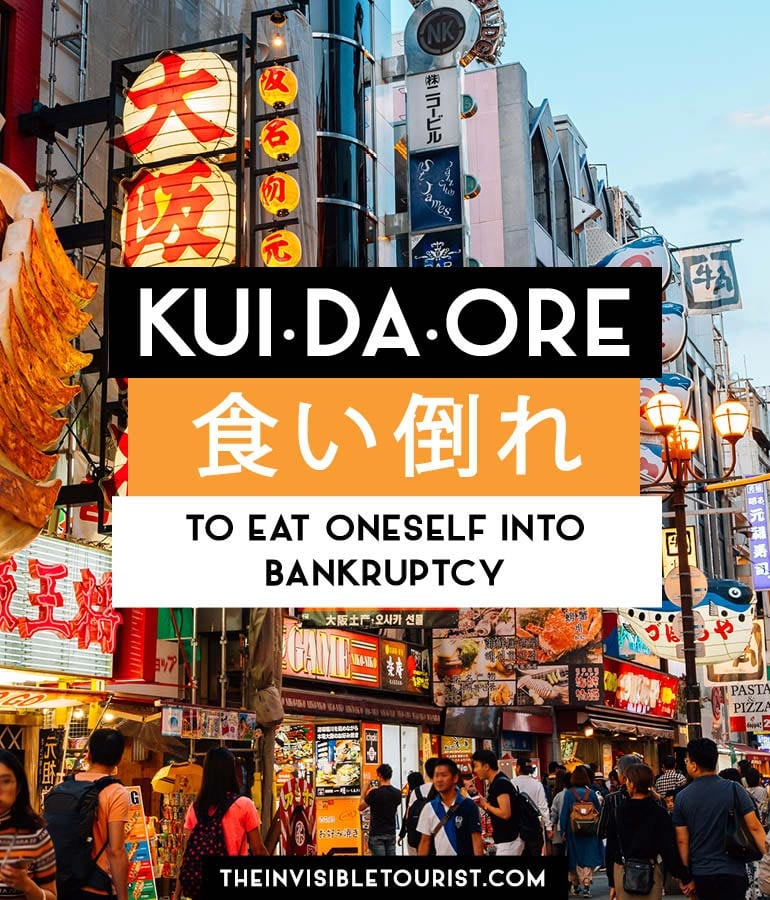

Kuidaore

食い倒れ

Ever wanted to buy ALL. THE. FOOD. in Japan? Of course, there is a cool Japanese word for this. Kuidaore quite literally means to “eat yourself into ruin” by spending all your money on food until you’re bankrupt.

Sounds a little dramatic but when you’re walking down Dotonbori in Osaka and the incredible aromas of sizzling street food meander their way to your nostrils, it’s easy to understand how someone could eat themselves into bankruptcy!

TIP: If you’re hoping to visit Dotonbori someday, my 3 day Osaka itinerary and Nara day trip guide has all the bases covered. Just make sure you leave some small change to buy senbei (crackers) for Nara’s sacred deer!

Kuchisabishii

口寂しい

Have you ever had that feeling around 3pm where you need to eat something without actually being hungry? To chew on something just for the sake of it? This is why I love the Japanese language, there is a word for this feeling – kuchisabishii!

Kuchisabishii translates “to eat because your mouth is lonely”. Should I be proud or ashamed to admit this? Haha, in all seriousness though, if you have been craving Japanese sweets and snacks to cure your lonely mouth I have some good news.

Take a look at my guides and reviews for how to have Japanese treats delivered to your door RIGHT NOW – direct from Tokyo!

- Traditional and artisanal Japanese sweets with Sakuraco →

- Trendy and fun Japanese snacks with TokyoTreat →

- Popular and traditional snacks from Japan →

Which are your favourite Japanese words with meaning?

This concludes my all-time favourite Japanese words and meanings! Through learning Japanese in a simple way, we realise we can incorporate different aspects into our own lives. Paying attention to seemingly ordinary things with a refreshed perspective can help bring more meaning into daily life.

I personally find that so satisfying and humbling considering these kinds of expressions don’t exist in the English language. Do you agree?

Which of these Japanese words is your favourite? Did I miss any? Leave me a note in the comments below! I hope you learnt something new and use some of these expressions more often. Now you know what a nakama is, if you’re lucky enough to have one be sure to let them know 😊

Want to learn my strategies for how to “blend in” anywhere around the globe? Find out by reading my #1 Amazon New Release Book!

Are you thinking about visiting Japan someday? Why not check out my popular itineraries and travel guides while you’re here for inspiration? From must-see destinations to lesser-known places off the beaten path, I have your future Japan trip planning covered. You can also come and join me on Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram and TikTok for more Japan inspiration!

Like it? Pin it! 📌

This guide to beautiful Japanese words contains affiliate links, at no extra cost to you. I may earn a small commission if you decide to make a purchase and if you do, thanks for your support! This helps with the costs of running my blog so I can keep my content free for you. As always, I only recommend a product or service that I genuinely love and use myself!

Like what you see? ✅ Sign up for my latest updates!

Enter your email here

Australian-based Alyse has travelled «The Invisible Tourist Way» for 15 years and hopes to encourage fellow travellers to do so, too. Based on her travels to 260+ cities across 32 countries, through her blog and #1 Amazon New Release book she shares passionate advice about responsible travel, history and preserving local cultures for more enriching experiences. Her dreams? Always about the next destination and how to make the most of it by «blending in.»

Japanese is a beautiful language, full of unique words to describe phenomena, feelings, and abstract ideas that cannot be neatly into a single English word. It’s one of the reasons why foreigners love to learn Japanese, as, when you experience the world through the language of another, you view life differently from how you would in your mother tongue.

Japan’s native language is full of interesting features, with complex sounds that make the language aesthetical. In this article, we provide the Japanese word first, the pronunciation second, and a contextual explanation of its meaning.

So, whether you’re learning to speak fluent Japanese, or you’re curious as to what deeper meaning you can find in life through the language, here are 21 unique Japanese words with deeper meanings and their translations.

1. 幽玄 – Yūgen

“Profound and mysterious beauty.”

This beautiful Japanese word is used in the context of a deep emotional response to a piece of art, like a Jackson Pollock painting, or nature.

Similar to the English ‘sublime’, yūgen deals with the depth of meaning we find in the world through our imaginative perception of the universe and its wonders. Our perception triggers an emotional response that cannot be explained, for it is much bigger than us alone, and yet we are part of it.

2. 懐かしい – Natsukashii

“Bringing forth happy, poignant memories of the past.”

Natsukashii is used in the context of an object, sense, or scene bringing back sentimental memories of the past that illicit a warm, poignant feeling within.

Not to be confused with the English word ‘nostalgia’, natsukashii is not related to a feeling tinged with sadness and longing. Natsukashii makes one feel grateful to have lived the memory, and move forward in life, without the desire to go back to it as it is something that cannot exist again.

3. 金継ぎ – Kintsugi

“The art of broken things.”

Kintsugi is used in the context of a broken object, like pottery, repaired with (traditionally) gold lacquer.

It’s a practice that was developed 15th century Japan that sought to create beauty out of what would have been considered worthless.

4. 侘寂 – Wabi-sabi

“Imperfect beauty.”

In terms of Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi is a central concept to both the language and traditional philosophy.

It comes from the teachings of Buddhism, Japan’s most popular religion alongside Shinto, about the transient, imperfect nature of life itself. Wabi-sabi serves to remind us that all things are impermanent, incomplete, and imperfect, which means that perfection is ultimately impossible. Therefore, we should always try to see the beauty in everything.

Japanese craftsmen often create or leave imperfections in their work, making their craft a physical symbol of this philosophy.

5. 木漏れ日 – Komorebi

“Dappled sunlight filtered through tree leaves.”

Have you ever walked through a wooded area, or Japanese garden, on a sunny summer’s day, and seen beams of light shining through the canopy? Or the dappled effect of those beams on the forest floor? That is komorebi.

This wonderful word is also used to describe the feeling of longing to be near someone who is too far away for you to visit, and missing their presence and all that it brings.

6. 生きがい – Ikigai

“A reason for being.”

Ikigai describes your reason for being, the reason you get up in the morning. Be it a family member, hobby, pet, or profession, Ikigai is how you would describe the thing that keeps you going through your ups and downs, and motivates you to move forward in life.

The Japanese believe that everyone has an Ikigai, it’s just a matter of finding it.

7. 物の哀れ – Mono-No-Aware

“The poignant sadness of impermanent things.”

Zen Buddhism teaches that all things are both imperfect and impermanent. Mono-no-aware is the poignant sadness of this awareness, which is beautiful in itself.

For example; the beauty of spring. After a long and bleak winter, we observe the beauty of fresh leaves on the trees, and pink cherry blossoms blooming as spring rolls in. But, the seasons are transient, and, if you feel a notable sadness that this state of natural beauty is only a moment in time that cannot last forever, that is Mono-no-aware.

In Japanese culture, mono-no-aware means you must take time to be present, and appreciate the impermanence of such natural beauty.

8. 守りたい – Mamori Tai

“I will always protect you.”

This heartfelt sentiment is typically reserved for when you’re expressing your feelings to a loved one, be it a family member, close friend, or romantic partner.

9. いただきます – Itadakimasu

“I humbly receive.”

In Japanese culture, Itadakimasu is often said before every meal. It is said to show appreciation for the work that went into the meal, at every stage; for the time and patience it took to grow the organic produce, the life of the animal or fish that now provides reviving protein and nutrients, and the love and care that went into preparing the finished meal.

It’s very utterance provides the diner a moment to be mindful and appreciative of the act of dining as a process of many, instead of one.

10. 森林浴 – Shinrin-yoku

“Forest bathing.”

This word translates literally; ‘shinrin’ means forest, and ‘yoku’ translates as bathing.

It’s scientifically recognised that walking among trees and nature can induce an inner sense of balance, lowering your blood pressure and cortisol levels. Shinrin-yoku is a word that describes that experience, but in more spiritual terms, referring to the calm that washes over us when immersed in a forest as a return to our natural essence.

11. 木枯らし – Kogarashi

“Wintry wind.”

This word is typically used to describe the first gusts of cold wind that signals the arrival of winter. The kind of wind that seems to penetrate beneath the skin, raising goosebumps, and sending a shiver through your body.

12. ふるさと – Furusato

“One’s hometown.”

Although furusato describes your hometown, at its core, the word refers to the place you feel your heart belongs. This place may not be where you were born or where you find yourself in the present, but it’s where you feel most at home and hold in your heart.

13. 浮世 – Ukiyo

“Floating world.”

This short Japanese word holds a layering of surprisingly deep and complex meanings. It’s a homophonous word that’s relatively uncommon, but interesting nonetheless – we had to include it!

In its origins, the term ‘ukiyo’ was associated with Buddhism and meant “transient, unreliable world”. Literally, ukiyo translates as “浮” floating, “世” world/society.

The word gained popularity in Edo-period Japan, specifically Yoshiwara, to describe the urban lifestyle and culture that existed at the time. Yoshiwara was home to (and infamous for) the licensed red-light district (now Tokyo), and a variety of late-night entertainment establishments, frequented by the Japanese middle class thrill-seekers of the time. It implies a dreamlike quality to the district, where nothing is as it seems.

Today, ukiyo is used to refer to a state of mind, emphasising being present in the moment and detaching one’s self from the stress and difficulties of life in order to truly live.

14. 一期一会 – Ichi-go ichi-e

“Treasuring an unrepeatable moment.”

Ichi-go ichi-e literally translates to “one time, one meeting”, but is used to describe the Japanese cultural concept of treasuring an unrepeatable moment.

The term stands to remind people that no moment in life can be repeated, our lives are made up of a series of unique moments and events that will never happen again.

For example, you go for tea with a group of friends and have a lovely time – that moment can never be repeated. You might try to replicate – inviting the same group of friends, to the same tea house, and ordering the same beverages – but, no matter how many variables are the same as it was before, it’s a separate experience, and it cannot truly be the same as it was.

Fittingly, the concept is most commonly used in relation to Japanese tea ceremonies.

15. 風物詩 – Fuubutsushi

“Things which remind of a season.”

For example, the smell of cherry blossoms might remind you of spring, whereas the smell of a log burner may signal that winter is approaching. Those smells are fuubutsushi.

Fuubutsushi applies to textures, flavours, and scenes/images, too.

16. 恋の予感 – Koi no yokan

“A premonition of love.”

In the Western world, many will have heard of, or even experienced, “love at first sight”, but koi no yokan is different.

Koi no yokan occurs when you first meet someone and know that, although you may not be in love with them at first sight, you will be in the near future.

17. 積ん読 – Tsundoku

“Acquiring books, but letting them pile up without reading them.”

Yes, there’s a word for that odd habit you have, and, if there’s a word for it, that means it’s more universal than you thought!

With so much going on in our perpetually busy lives these days, sometimes it’s hard to find the time to read as much as we’d like. You buy one or two books to tick off your reading list, and make a start on the first. But, then, you hear about another book that’s meant to be amazing, so you go to the bookshop, and walk out with four.

Before you know it, you practically have a library in your home, the majority of which haven’t been read. That is tsundoku (“積む” tsumu, ‘to pile up’, and “読” doku, ‘reading’) – don’t worry, it’s common!

18. 食い倒れ – Kuidaore

“To eat until you’re bankrupt.”

Kuidaore is a fun, cool Japanese word with a deep meaning that had to make our top 21 list. It’s used by foodies who love to go out to eat, be it at restaurants or street food markets.

It’s a word commonly found in Dōtonbori, one of the most popular tourist destinations in Osaka, Japan, and one of our top 20 places to visit in Japan. Dōtonbori is home to a dazzling array of nighttime entertainment and, thanks to its wide variety of mouthwatering restaurants, is considered the best place in Osaka for food and drink, too. You’ll find the phrase kuidaore in Dōtonbori’s tourist guides and advertisements, encouraging visitors to indulge in the many cuisines until you simply can’t eat any more (or, afford to!).

Kuidaore is sometimes romanised (romanticised Japanese) as cuidaore, which is part of the proverb: 「京都の着倒れ、大阪の食い倒れ」, meaning “ruin yourself with fashions in Kyoto, ruin yourself with meals in Osaka”.

19. 甘美な (かんび な) – Kanbina

“A word that sounds sweet and pleasant to the ear.”

A fitting addition to our list, kanbina is an expression used when a word a beautiful to hear – and the Japanese language is full of such words. It might be the way the word rolls off the tongue, the shape of the sounds, or the meaning behind it that makes it sweet and pleasant to the ear. It can also be used to compliment someone, or flirt with them, when they first tell you their name.

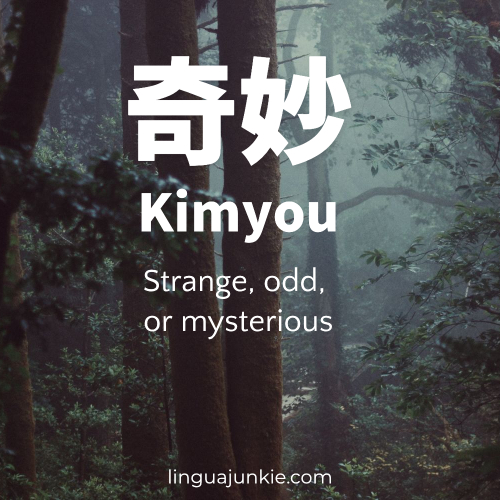

20. 奇妙 – Kimyou

“Strange, odd and/or mysterious.”

Kimyou can be used to describe situations, objects, or locations that strike you as mysterious, or strange. For example, a misty cemetery, an optical illusion, or an anonymous letter.

21. 花霞 – Hanagasumi

“A mist of flowers.”

An image common in springtime across Japan is a flurry of cherry blossom petals on the wind, so many that it appears like a haze of white and pink. Hanagasumi is the word the Japanese use to describe the sight, and, hopefully, you’ll have the opportunity to experience it first-hand.

We hope you enjoyed our list of Japanese words with deep meanings, perhaps one or two have been powerful enough to add a layer of meaning to your life. If you’re looking to further your knowledge of the Japanese language, the best way to learn is to immerse yourself in the culture. Get in touch today to find out how you can make you can explore Japan whilst earning a living.

Did you know that in the Japanese language, there are many words with multiple meanings? These words can come across very differently depending on the situation you use them in!

In this blog article, we will be sharing with you 10 Japanese words that have multiple meanings, some of which you might even find very familiar too!

1. はい Hai

はい Hai literally means “yes” in English.

Everywhere you go in Japan, you can hear people saying “はい, はい” (hai, hai) when talking to others. In this case, the other meaning of はい (hai) is “I understand what you are saying” or simply put, being “affirmative”. This links with Aizuchi, which are Japanese conversational interjections, to show active listening. When はい (hai) is used in a conversation, it shows that the listener has attention and interest towards the speaker. Hence, saying はい (hai) does not always necessarily mean that you are agreeing with the other person, but just confirming what they said!

2. 難しい Muzukashii

難しい (Muzukashii) means “difficult” in English.

難しい (Muzukashii) can also be used as a way to refuse someone politely when they ask you to do something. Instead of being straightforward to reject, you can use “難しいですね” to tell the other person ambiguously that you are reluctant.

Sentence Example:

A: 貴社での就職を手伝ってくれませんか? Kishadeno shushoku o tetsudattekuremasenka?

(Could you help me get the job at your company?)

B: 難しいですね.. Muzukashii desune..

(No I can’t..)

3. 結構 Kekkou

When you search up the meaning of 結構 (kekkou), you may find yourself with a few definitions, such as “wonderful; nice”, “enough” and “quite; reasonably”. 結構 (kekkou) can be used in many ways, and the meaning can also vary depending on the tone of your voice!

When you want to describe something as “wonderful; nice”, you can say 結構です (kekkou desu).

Another way to use 結構 (kekkou) is when saying no to someone. For example, when someone offers to pour you a drink, you can say 結構です(kekkou desu), meaning “No, thank you, I’ve had enough”.

One other common way to use 結構 (kekkou) is “quite” or “reasonably”. If you want to say that something was quite fun, you can say 結構楽しかった (kekkou tanoshikatta).

4. どうも Doumo

どうも (Doumo) is a versatile word that can be used in many ways. It can be used to stress your feelings, whether it is for appreciating or apologizing.

どうも (doumo) can be used as an informal way of saying “hello”, “goodbye”, “thank you”, “sorry” and “very”.

Sentence Examples:

1) To use as “hello” or “goodbye” or “glad to meet you”: どうも Doumo

2) To use as “thank you”: どうもありがとう。 Doumo arigato.

3) To use as “sorry”: どうもすみません。 Doumo sumimasen.

5. ちょっと Chotto

ちょっと (Chotto) is one of the most useful words in the Japanese language that has a wide range of meanings.

ちょっと (Chotto) literally means “a little” in English. It can also mean “a while; a moment” and “rather; pretty”. You can use ちょっと (Chotto) in a situation when something is not easy for you and you want to say no in an ambiguous way.

Sentence Examples:

ちょっとだけ日本語が話せる。Chotto dake nihongoga hanaseru.

(I speak Japanese a little.)

ちょっと待って下さい!Chotto matte kudasai!

(Please wait for a moment!)

昨日のテストちょっと難しかったよ。Kinou no tesuto chotto muzukashikattayo.

(Yesterday’s test was rather difficult)

A: 昼ご飯を一緒に食べませんか?Hirugohan o isshoni tabemasenka?

(Do you want to eat lunch together?)

B: 用事があるので、ちょっと。。。Youji ga aru node, chotto…

(I have some things to do so…)

6. やばい Yabai

やばい (Yabai) originally means “dangerous” and is used to mean “Look out!” or “Heads up!”. Now, やばい (Yabai) is more commonly known as a slang word that is used for just about anything, positive or negative. It can mean ‘Shoot!’ or ’super’ when describing something.

Sentence Examples:

この携帯電話やばい高いよね?Kono keitai denwa yabai takai yone?

(This mobile phone is super expensive, don’t you think so?)

やばい!バスにのりお売れる!Yabai! Basuni noriokureru!

(Shoot! I’m going to miss the bus!)

7. 甘い Amai

甘い (Amai) means “sweet” in English and is used to describe food. Another meaning of 甘い (Amai) is “naive”, which you can use to describe a person!

8. しろ Shiro

しろ (Shiro) means “white” in English.

You can also use しろ (Shiro) to describe someone who is “pure” or “innocent”.

9. くろ Kuro

くろ (Kuro) means “black” in English and can also be used to describe a “guilty” person.

10. そば Soba

そば (Soba) is often known as the noodle “soba”, but it also means “nearby”!

Start taking Japanese lessons and learn the meaning of more Japanese words at Coto Academy!

Team Japanese uses affiliate links. That means that if you purchase something through a link on this site, we may earn a commission (at no extra cost to you).

“If we spoke a different language, we would perceive a somewhat different world.”

‒ Ludwig Wittgenstein

Do you agree with this quote? I know I do. Many languages have beautiful and unique words which cannot be translated precisely. These words often represent concepts which are so unique to that culture, there is simply no equivalent in any other language.

We’ve collected 12 of our favourite beautiful Japanese words with no exact English equivalent.

Of course, most of these ‘untranslatable words’ can be translated literally – after all, we did our best to provide translations in this article! But the concepts are unique, and so they require some explanation for English speakers.

The interesting thing about these Japanese words with deep meaning is that they reveal a lot about the Japanese character. Many of these words reflect Buddhist concepts which are unknown to most Westerners, but are central ideas in Japanese society.

By learning these unique Japanese words, you are one step closer to understanding the Japanese soul.

Shinrinyoku (森林浴)

Shinrinyoku literally translates as ‘forest bath’. It refers to taking a walk in the forest for its restorative and therapeutic benefits. Can’t you feel yourself relaxing as you soak up all the lovely green light? Scientists have actually found that walking in the forest has many health benefits such as lowering blood pressure and stress hormones. It seems the Japanese are one step ahead with their shinrinyoku practise!

Komorebi (木漏れ日)

Komorebi is an aesthetic Japanese word meaning ‘the sunlight filtered through leaves on trees’. This is a beautiful word to describe a beautiful moment. You can enjoy some komorebi while taking your shinrinyoku!

Kuidaore (食い倒れ)

Kuidaore means something like ‘to eat yourself bankrupt’. The word implies a kind of extravagant love of good food and drink – so much love that you will happily spend all your money on it! It comes from the words 食い (kui – eating) and 倒れる (daoreru – to go bankrupt, be ruined).

Kuidaore has come to be associated with the Dōtonbori district in Osaka, famed for its many restaurants and nightlife spots. You have been warned!

Tsundoku (積ん読)

Here’s one for the book lovers. Tsundoku is the practise of acquiring books and letting them pile up, unread. Anyone who just loves books but doesn’t have time to read them as fast as they buy them will understand this one. It uses the words 積む (tsumu – to pile up) and 読 (doku – to read). It’s also a clever pun, because tsunde oku means ‘pile up and leave’.

Wabi-sabi (侘寂)

Wabi-sabi means imperfect or incomplete beauty. This is a central concept in Japanese aesthetics, which comes from Buddhist teachings on the transient nature of life. A pot with a uneven edges is more beautiful than a perfectly smooth one, because it reminds us that life is not perfect.

A Japanese craftsman will intentionally add in a small flaw after completing his perfect work in honour of this concept.

Kintsugi (金継ぎ)

Another cool Japanese word, kintsugi (金継ぎ), also known as kintsukuroi (金繕い), is the practise of mending broken pottery with gold or silver to fill the cracks. This is a perfect example of wabi-sabi. Rather than rejecting a broken item, you can find a way to make it even more beautiful. This practise accepts the break as part of the object’s unique history.

Mono no aware (物の哀れ)

Mono no aware can be translated as ‘the sadness of things’. It comes from the words 物 (mono – thing) and 哀れ (aware – poignancy or pathos). The ‘sadness’ in question comes from an awareness of the transience of things, as taught by Zen Buddhism.

When we view something exceptionally beautiful, we might feel sad because we know it won’t stay so beautiful forever – but appreciation only heightens the pleasure we take in the beautiful thing in that moment.

The best example of mono no aware in Japanese culture is hanami, the ritual of appreciating the cherry blossoms each year. Cherry blossom are very special to the Japanese, but the flowers bloom for only two weeks in the springtime. We appreciate the flowers even more because we know they will fall soon.

Related post: 16+ Essential Japanese Words for Spring

Irusu (居留守)

Irusu is when somebody you don’t want to speak to rings your doorbell, and you pretend nobody’s at home. I think people do this the world over, even if other languages don’t have such a concise word for it!

Nekojita (猫舌)

Here’s a cute one! A nekojita is a person who is sensitive to hot foods and drinks. It literally translates as cat tongue! It’s made from the two words 猫 (neko – cat) and 舌 (shita – tongue). Do cats really hate hot things? I don’t know, but this cute Japanese word implies that they do!

Karoshi (過労死)

The sad Japanese word karoshi means death from overworking. Tragically, the fact that there is a word for this in Japanese also tells you something about Japanese culture.

Karoshi is usually associated with Japanese salarymen who work in a corporate culture of extreme long hours. The Japanese Ministry of Labour official defines karoshi as when somebody works over 100 hours of overtime in the month before their death. The phenomenon reached an all time high in 2016.

Shoganai (しょうがない)

If you live in Japan, this one will be very useful for you! Shoganai means ‘it can’t be helped’. It’s a fatalistic resignation to a situation that is out of your control. It is often used to mean that there is no point complaining about a situation, because you will not have the power to change it.

Some people suggest that the concept of shoganai is why Japanese people remain so stoic in the face of natural disasters such as tsunami and earthquakes.

Natsukashii (懐かしい)

The beautiful Japanese word natsukashii is often translated as ‘nostalgic’. However, whereas nostalgia is a sad emotion in English, natsukashii is associated with positive (yet poignant) feelings. Something is natsukashii if it allows you to relive happy memories of the past. It comes from the verb natsuku (懐く), meaning ‘to become attached to’, and could also be loosely translated as ‘fondly remembered’ or ‘beloved’. This warm but wistful feeling makes it one of the most aesthetic Japanese words.

Yoroshiku (宜しく)

Yoroshiku is probably the most common word on this list, and the word you’re most likely to come across if you’re a beginner studying Japanese! Still, yoroshiku is a great example of an untranslatable Japanese word.

Yoroshiku can mean different things in different contexts but the basic meaning is ‘please be good to me’. Of course, that sounds pretty awkward in English, which is why it’s so difficult to translate.

Depending on the context, yoroshiku or its more formal version, yoroshiku onegaishimasu could be translated as ‘nice to meet you’, ‘best wishes’, ‘I look forward to working with you’, ‘please’ or ‘thank you’. We usually say it when we first meet someone, when we ask someone for a favour, when we are about to start a project together, or when we simply want to express good will.

Itadakimasu (いただきます)

This is another unique, untranslatable Japanese word that even beginners should know. Japanese people always say itadakimasu before eating. Since we don’t have an equivalent word in English, we often borrow from another language to translate it – the French phrase bon appétit!

However, even this is not a true translation. The key meaning of itadakimasu is gratitude for the food. When you say itadakimasu, you are thanking everyone and everything involved in putting the food on your table – from the farmers, the shopkeepers and the chefs to the food itself. Perhaps, spiritually, it’s closer to saying the Christian tradition of saying grace before a meal.

Itadakimasu comes from the verb itadaku (頂く / いただく ), which is the humble form of the verb ‘to receive’. You can also say it when receiving a physical object, or asking for a favour.

Bimyou (微妙)

The dictionary has several translations of bimyou: subtle, delicate, doubtful, complex. As if that isn’t vague enough, bimyou has another kind of usage as a Japanese slang word.

Japanese people often describe something as bimyou when they don’t care or don’t really like it, but they don’t want to say that directly. It can also be a way to say something is unnecessary or a little bit off. And if you respond to an invitation with bimyou, that’s basically an indirect way to say no in Japanese. Depending on the context, in English we might say ‘meh’, ‘not really’ or ‘hmmm…’.

Yūgen (幽玄)

Thanks to reader Curi for suggesting this beautiful Japanese word! Yūgen means something like ‘profound, mysterious beauty’. It is often used in the context of a deep emotional response to art, literature, or the beauty of the natural world. It also can imply a level of sadness at the suffering of the human condition.

This is the feeling you might get when you watch a beautiful sunset or stare out at the ocean, and think about how small you are in the context of the universe. Yūgen has a big influence on Japanese art forms such as landscape painting and Noh theatre.

Ikigai (生き甲斐)

Ikigai is a beautiful Japanese word that refers to one’s life purpose or reason to live. This is another one where we often borrow the translation from French, because we lack the words in English: raison d’être.

It’s the thing that gives us a reason to get out of bed each morning. It could be work, a hobby, family or something else. Some experts suggest that ikigai is one reason why people live so long in Japan.

Of all the Japanese words with meaning in this article, ikigai is one that could literally change your life!

Wa (和)

Wa can be translated as harmony or peace. It can carry meanings such as avoiding conflict, preserving social unity, and visual harmony (for example, presenting your food beautifully on your dinner plate!)

Wa is a central concept in Japanese culture that affects everything from architecture to workplace politics. In fact, it is so central in Japan that wa is the old name for Japan, and it is used to refer to Japanese style things (as opposed to western/foreign). Some useful Japanese words using ‘wa’ in this way are:

- 和風 (wafuu) – Japanese style (e.g. food, restaurant)

- 和室 (washitsu) – Japanese style room

- 和服 (wafuku) – traditional Japanese clothing

- 和紙 (washi) – Japanese paper

Koi no yokan (恋の予感)

In English, we often talk about ‘love at first sight’. Koi no yokan is slightly different: it’s when you meet someone and perhaps you don’t fall in love straight away, but you have a very strong feeling that you will fall for them in the future! It can be translated literally as ‘love’s premonition’.

Kuchisabishii (口寂さびしい)

The cool Japanese word kuchisabishii translates literally as ‘lonely mouth’. Sounds cute, right? It’s used when you eat mindlessly, perhaps because you’re bored, rather than hungry. Your mouth is lonely and you’ve got to fill it up! You can say it about cigarettes as well as food.

Mottainai (もったいない)

Mottainai can most simply be translated as ‘wasteful’, but the full meaning goes deeper than that. Like many of the words on this list, mottainai has its roots in Buddhism and the concept that all things are precious.

You will typically hear people say it if someone wastes food, or throws away an object that could be reused. You can also say it about yourself to seem humble. For example, if someone gives you a gift and you say mottainai, you’re saying ‘don’t waste this beautiful object on me! I’m not worth it!’ Similarly, you could say it about your partner, to mean that you don’t deserve such a great person in your life.

Bureikou (無礼講)

Bureikou is a situation where you can be completely at ease: all pressure’s off, you can say and do what you like, and you don’t have to worry about status or hierarchy. An example of a bureikou is a company party when bosses and employees get drunk together and can speak as equals. Since social hierarchy is usually very important in Japan, holding a bureikou party is a way that bosses can encourage their employees to relax.

Coincidentally, this word is easy to remember because it sounds a bit like the English word break.

Furusato (故郷)

The kanji of furusato (故郷) mean old (故) village (郷). It is usually translated as ‘hometown’. However, although at first glance this word seems to have a simple translation, I would class furusato as an untranslatable Japanese word because it carries a lot of nuances that are missing from the English word!

For a start, furusato has rural connotations. While it can be used to describe someone’s literal hometown or birthplace (especially by people from the countryside), it is sometimes used to talk about the Japanese countryside in general. It’s a romantic, nostalgic word and conjures images of a traditional way of life.

People born in Tokyo would not describe the city as their furusato, but they might use that word to talk about their grandparents’ place in the country. The feeling is something like a ‘spiritual homeland’. Furusato is a common theme in Japanese music, literature and art.

Majime (真面目)

Majime is an adjective that is usually translated as ‘serious’. Again, while at first glance this seems easy to translate, it’s kind of an untranslatable Japanese word because it has slightly different connotations in Japanese than in English. Other ideas evoked by this word are earnest, responsible, reliable and trustworthy.

In English, ‘serious’ can often feel negative. If you describe someone as serious, you might be saying that they are too uptight and don’t know how to have fun. But in Japanese, majime is a positive quality that means you respect and trust someone. You would want to hire a majime employee for your business, or take a majime partner home to meet your parents!

Majime can be shortened to maji (マジ), often used in the format maji de?! (マジで) which is slang for ‘seriously?/no way!’

Related posts:

- 27 Beautiful and Inspirational Japanese Quotes

- 9+ Stunning Japanese Words For ‘Beautiful’

- 70+ Beautiful Japanese Nature Words to Inspire You

Do you know any beautiful or untranslatable Japanese words? Share them with us in the comments!

Want to learn more awesome Japanese words? Grab a free trial of our recommended course.

This article was first published on 01 April 2017 and last updated on 17 January 2022.

The Japanese culture is known for its appreciation of nature and for finding beauty in simplicity. It is no wonder then that their language reflects the zen-like beauty their culture emanates. There are hundreds of untranslatable Japanese words that have no English counterpart. Attempts to translate these beautiful Japanese words into English result in poetic descriptions that warm the soul.

Beautiful and Untranslatable Japanese Words with No English Equivalent

The pronunciations alone of these untranslatable Japanese words ooze beauty as they roll off the tongue. But their meanings paint beautiful imagery that English speakers can only wish to encompass in a single word.

1. Flower Petal Storm

Hanafubuki is usually used to describe how cherry blossom petals float down en-masse, like snowflakes in a blizzard. I certainly wouldn’t mind being caught in this storm.

2. Beauty in Imperfection

When you adopt a wabisabi perspective, you accept that life is imperfect and, therefore, can appreciate the beauty of imperfect things. Japanese artists embrace wabisabi by purposely leaving imperfections in their artwork. For instance, a knot left in a wood carving or a crack in a piece of pottery.

3. Collecting Books with Reading

Booklovers are all too familiar with the truth behind the Japanese word tsundoku. In English, this untranslatable Japanese word describes the act of piling up books that you never get around to reading.

4. Memories That Warm the Heart

While the Japanese word ‘natsukashii’ does have an English equivalent in the word ‘nostalgia,’ the use and meaning of the word are quite different. Natsukashii is used quite often in everyday language in Japan. When used, Japanese people are not saying “nostalgia”; they are expressing a feeling that warms the heart because it brings back memories.

5. It Is What It Is

We are all familiar with the English expression that we use when we can’t do anything about a situation or when we give up because it’s out of our control. “It is what it is,” we say. But the Japanese wrap this up into one untranslatable Japanese word: Shoganai.

6. Just Be Yourself

Often used at company outings, the Japanese word Bureikou (which, coincidentally, sounds like ‘break’ in English) releases people from the confines of social status to just be themselves. It is a way to tell people to take a break from the pressures of the real world to be who you are without consequence.

7. Selfless Hospitality

Omotenashi is an untranslatable Japanese word that represents careful thoughtfulness. It is the type of hospitality that puts the customer or guest first without the expectation of anything in return.

8. Mouth Lonely

‘Kuchisabishii’ makes the list because the literal translation is cute and oh-so appropriate to express its meaning. When you are ‘mouth lonely’ you eat out of boredom rather than hunger.

9. Leaves Changing Colour

Like Hanafubuki is used in Cherry Blossom season, Kouyou is used as Autumn arrives. Kouyou is a way to say, “The leaves are changing colour, so Autumn is near.”

10. I Humbly Receive with Gratitude

Usually spoken before eating, ‘Itadakimasu’ is often translated as ‘bon appetit’ but much of the meaning is lost by doing so. Itadakimasu is beautifully nuanced to express gratefulness to all those responsible for producing the meal, from the farmers to the grocers to the cooks, and so on.

11. A Cold Wind of Winter

As winter approaches, Japanese people will use the word ‘Kogarashi’ every time a bitingly cold wind sends shivers down their spine.

12. Sunlight Leaking Through the Trees

In a single untranslatable Japanese word, ‘Komorebi’ illustrates a beautiful forest with sunlight peeking through the leaves of the trees. What English word could compare?

13. Bitter Sweetness of Fading Beauty

Though technically this is three words in Japanese, ‘Mono no aware’ shows an appreciation for things that quickly pass or are soon lost. This phrase is often used to describe the short Cherry Blossom season.

14. A Profound Sense of the Universe

Yugen describes the emotional response one feels when they consider things too big to comprehend, like how many stars are in the universe, or the mysteries of creation.

15. Soaking in the Forest

Literally translated to ‘Forest Bathing,’ Shinrin-yoku describes spending time in the forest to reduce stress, which has been clinically proven to be effective.

16. Worth Living For

Ikigai is a person’s reason for being. It’s the passion, purpose, or value that makes life worth living.

17. Love is Inevitable

Often translated as ‘Love at first sight,’ ‘Koi no Yokan’ is not quite the head-over-heels love you’d expect from the mistranslation. More accurately, it means you are bound to fall in love even if you don’t feel it now.

18. Light of a River in Darkness

Just like many untranslatable Japanese words, kawaakari conjures an entire landscape in the mind’s eye. This word refers to light reflected off a river at night or dusk.

19. From Strangers to Family

Ichariba chode embraces the spirit of friendliness to strangers. In ways, it can be compared to the sentiment of ‘Mi casa es su casa’ but more accurately means ‘from strangers to brothers or sisters.’

20. Golden Repair

In the way wabisabi embraces imperfections, kintsukuroi (or kintsugi) repairs pottery with gold or silver. Instead of trying to blend and hide the imperfection, kintsukuroi highlights its beauty.

21. Can’t Be Touched

Kyouka suigetsu is a Japanese phrase that can’t be easily translated into English. It refers to something that is visible but can’t be touched, like the moon’s reflection on the water. Or, an emotion that can’t be described in words.

22. An Unattainable Goal

Literally translated as ‘flower on a high peak,’ ‘takane no hana’ describes something that is beyond your reach.

23. Viewing the Moon

Japanese festivals often revolve around nature. Tsukimi is the act of viewing the moon, which is often enjoyed en-masse during moon-viewing festivals in September or October.

Translating Untranslatable Japanese Words

The Japanese language is filled with words that are very descriptive in their simplicity. A single word can have more depth and impact that is difficult to capture in other languages. When there is no English equivalent, translators must explore the nuances of a word’s meaning and endeavour to convey a word’s true meaning.

Check out our other article on “The 7 Hardest Languages to Translate into English” and learn more about Avo Translations’ experienced team of translators.

Last Updated on 18/12/2021 by

I’m not sure when my love for the Japanese language started. Still, I have always loved the language and especially the aesthetic behind the Japanese words.

In most languages, especially in Japanese, you will find words that cannot be translated as they have no direct equivalent. These words often convey feelings or concepts that do not exist or are not expressed in other cultures.

I have noted in this guide a selection of 20 Japanese words and expressions linked to the culture and aesthetics of Japan and which can inspire us all daily. For each word, there will be kanji, hiragana/katakana and rômaji readings.

Wabi sabi – ã‚ã³ã•ã³ – 侘寂

I first heard of wabi-sabi while purchasing a set of teacups in Kyoto’s flea market. One of the cups appeared to have a small crack mended together. This act of purposely leaving the imperfections visible (kintsugi) symbolizes the very heart of wabi-sabi.

The first kanji 侘 (wabi) means “the beauty found in simplicity and sobriety”. In contrast, the second kanji (sabi) represents “the feeling of peace that emanates from old things”, as well as refined simplicity. The two words together denote an aesthetic concept derived from the Zen philosophy of Buddhism, advocating simplicity and elegance. It is about recognizing the beauty in things old, modest and imperfect.

In the Zen philosophy, there are seven aesthetic principles that allow Wabi-sabi, the state of awareness of the imperfection of things:

- Kanso (ç°¡ç´ ) – simplicity

- Fukinsei (ä¸å‡æ–‰) – asymmetry, irregularity

- Shizen (自然) – naturalness without pretension

- Yugen (幽玄) – subtle grace, not obvious

- Datsuzoku (脱俗) – freeness

- Seijaku (é™å¯‚) – tranquility, silence

- Koko (考å¤): basic, weathered

Kintsugi – 金継ãŽ

The practice of mending broken pottery with gold and silver to fill the cracks is called Kintsugi (金継ãŽ). It is also sometimes referred to as kintsukuroi (金繕ã„). In a society where it is customary to over-consume, we tend to discard things that we believe are no longer perfect. Kintsugi offers a second life to broken items. It allows you to restore broken or damaged objects by sublimating them with gold, not by hiding cracks.

The philosophy behind kintsugi is to put forward the imperfections, errors and mistakes to celebrate them as a new/restored object rather than discarding them altogether.

Kanso – ç°¡ç´ – ã‹ã‚“ã

Kanso is the Japanese zen principle meaning simplicity or elimination of clutter. Things are expressed in a plain, simple, natural manner.â€

I’m sure most of us have heard of Marie Kondo, the Japanese organizing guru. Through her Netflix show Tidying Up With Marie Kondo, she set off the world into a decluttering craze.

Her “spark joy†catchphrase comes from the concept of kanso, which means simplicity. Like the Chinese feng shui, kanso focuses on harmonizing with your surroundings, thus (getting rid of clutter and non-essential items) choosing natural furniture and minimal artwork.

Ikigai – 生ããŒã„

Ikigai is a Japanese philoso[hy that refers to all the things worth living for. Since there is no direct translation, the word has different interpretations depending on how people use it. Linked to kanso, you can use ikigai to aid the reorganisation of your home in a minimalist way.

Above all, ikigai is about personal development to feel happier in your life.

Inspiring and Meaningful Japanese words

Shinrin yoku – 森林浴

Being in contact with nature does all of us good, especially nowadays where most people are forced to stay indoors. Walking in the woods or even a big park with lots of trees and nature does well to lift people’s morale and relieve stress.

“Forest baths,” or “shinrin-yoku,” are a Japanese medicinal practice that involves walking in the woods, fully breathing the scent of trees and listening to birds chirping.

It is believed to have many restorative and therapeutic benefits that are almost like food for the soul. Plus, Shinrin-yoku can be done anywhere with trees, no matter your fitness level.

Kuchisabishii – å£å¯‚ã—ã„

Have you gained a few pounds during lockdown due to the unlimited access to your fridge and lack of activity? Have you been making short trips to your kitchen or looking inside your fridge searching for something to eat? The act of eating out of boredom is a manifestation of “kuchisabishiiâ€.

The word would be translated as “lonely mouth†or “craving†in English. Still, there is no precise translation to express the compulsive aspect of this habit. Basically, you have enough room to eat even though you are not hungry.

I was introduced to this world during a call with a Japanese friend. She found not snacking hard with the abundance of delicious sweets and pastries.

Kuidaore – 食ã„倒れ

Kuidaore is something that many people worldwide, especially foodies, have experienced. Kuidaore describes a situation where someone loves food and drink so much that they will happily spend all their money on it. Foodies who visit all the hip restaurants are victims of this.

Fact: Kuidaore is associated with DÅtonbori, the foodie district in Osaka. The foodie hotspot has all lines after lines of restaurants, food stalls and markets. Every nook and cranny is filled with an eatery, all selling delicious food. Anyone who loves Japanese food must go there.

Irusu – 居留守

Imagine someone you don’t want to see at your doorstep, so you pretend you are not home. There is a word to express that in Japanese, and it’s called irusu.

Ganbatte – é ‘å¼µã£ã¦

Ganbatte is an essential word in Japan used to encourage people to strive for something. It’s all about the positivity of doing your best, moving forward, fighting, working hard and not giving up.

The word means to persevere, persist or insist and is often translated as good luck.

A similar expression – Nanakorobi yaoki – translates to “fall down seven times, stand up eight†and is one of the best ways to describe the Japanese spirit.

Mono no aware – 物ã®å“€ã‚Œ

Mono no aware refers to the awareness of the fading nature of beauty. It is about being aware of the temporary existence of things, therefore, appreciating them while they last. A great example of mono no aware is hanami and hanabi (summer fireworks). Cherry blossoms (sakura) are important to Japanese people since they have a short blooming period.

Omotenashi – ãŠæŒã¦æˆã—

The Land of the Rising Sun is undoubtedly a warm country where you will be able to get help for the slightest problem. Omotenashi is about treating your guest, customer or neighbour the best way possible. It goes with ichigo ichie seen in tea ceremonies. The idea is that every meeting with a guest is a unique moment that should be treasured.

I believe this goes beyond the concept of “Treat others as you would like to be treatedâ€. The term describes deep hospitality often seen in accommodations, shops, restaurants, etc. the best places to experience omotenashi are tea ceremonies and ryokans.

Essential everyday Japanese words

A fundamental way of thinking in Japanese culture, especially Buddhism, is to appreciate. Not all of these essential Japanese words have a tangible equivalent in English. But knowing them and how to use them will help you make the most of your trip to Japan.

Itadakimasu – ã„ãŸã ãã¾ã™

When eating a meal, people say itadakimasu, which loosely translates to “bon appetit†or “let’s eatâ€. A better translation of this word is “ I humbly receiveâ€. The purpose is to thank the person who cooked the food you are about to eat and all the other people involved in the food production.

Gochisousama deshita – ã”ã¡ãã†ã•ã¾ã§ã—ãŸ

After you’ve finished eating, you say ã”ã¡ãã†ã•ã¾ã§ã—ãŸ, which means “Thank you for this meal.” as with Itadakimasu, it’s about being thankful for the food.

Whenever you are in someone’s house or a restaurant, it’s a polite thing to do to thank your host.

Otsukaresama – ãŠç–²ã‚Œæ§˜

In the same vein as itadakimasu and gochisousama, otsukaresama is used to thank someone. Short for ãŠç–²ã‚Œæ§˜ã§ã—㟠(otsukaresama deshita), it means “You are tired because you’ve worked hard!”. It’s a useful word used between coworkers or friends as a greeting, goodbye, or to express gratitude for their hard work and contribution.

When meeting my Japanese teacher (who is now a good friend) after work, she would say the first and last thing to me was “otsukare”. This word is one of my favourites as it is the synonym of all the hard work I put into learning the language.

Ojama shimasu – ãŠé‚ªé”ã—ã¾ã™

When entering someone’s room or house in Japan, you must say “ojamashimasu” which means ‘thank you for inviting me’ or ‘thank you for having me’. This expression is also used to say ‘sorry to disturb’ you when talking to someone or interrupting a conversation.

You say this every time you enter someone’s home, whether planned or unexpected. When you leave, you repeat the phrase but in the past tense: ãŠé‚ªé”ã—ã¾ã—㟠(ojama shimashita).

Hard to translate Japanese words

The Japanese language has many words that are hard to translate. Sometimes, they relate to a particular aspect of the country. Here are some of my favourite words.

Shouga nai – ã—ょã†ãŒãªã„

This word is handy as it enables people to think positively even in unpleasant or frustrating situations. “Shouga nai” means something similar to “it can’t be helped” or “nothing can be done.” Instead of brooding about things you have no control over, you can use the word, to forget about it. Worrying, guilt or regret then makes no sense.

Having said that, “shouga nai” is a far more complex word and comes with many cultural weights, which might be hard to understand. The expression refers to a philosophy of existence based on the importance of acceptance.

Tsundoku – ç©ã‚“èª

Do you have piles of books just waiting to be read? Do you visit bookstores and buy books because they look pretty? If so, then you might be doing tsundoku.

Tsundoku is the art of buying and accumulating books without ever reading them. The urge to buy a new book knowing that we won’t have time to read them indicates how much people love books, even as e-readers are present. I’m sure most of us have a book or two lying around and dying to be read. I am guilty as charged since I find it more and more difficult to leave my phone for a while.

Komorebi – 木æ¼ã‚Œæ—¥

Imagine you are in a park on a summer day, lying in the shade and enjoying a peaceful time. Suddenly you see the light filtering through the branches of a leafy tree and hitting the grass? In the Japanese language, it is called: komorebi. The shadow created on the ground, or even in our curtains, describes this everyday beauty. Poetic right? I don’t know if any other language has a way of describing this.

Cool Japanese Onomatopoeia Words

In the Japanese language, there are many onomatopoeia, words that mimic the sound of the things they are referring to. The Japanese language has different categories for onomatopoeia, each with its way of expressing things. Doki doki and Kasakasa are two of my favorites.

Doki doki – ã©ãã©ã – ドã‚ドã‚

Doki doki expresses both the sounds of a living thing (gisei-go) and an emotional state (gijou-go), which describes the feeling of excitement or nervousness and the actual sound of a rapid heartbeat.

When you exercise, for example, after climbing six flights of stairs, when you are excited, worried or upset, your heart rate goes faster, right? It goes something like dokidokidokidokidoki, but when you are relaxed, it’s more the slow doki…doki…doki… sound.

Kasakasa – ã‹ã•ã‹ã•, カサカサ

Kasakasa is a word that describes the rustling sound that dry things make when they touch each other.

I first came across this cute Japanese word when I visited Nikko with my Japanese friends. We walked along a path full of Ginko trees on an Autumn day. My friend said that the noise we were making when walking on Ginko leaves was “kasakasaâ€.

BONUS

Yoko-meshi – 横飯

Yoko-meshi is an expression I relate to and rank high on my favourites list. This beautiful Japanese word means “a meal eaten sideways”. It comes from “meshi”, which means ‘boiled rice’ and “yoko”, which means ‘horizontal”. And no, it doesn’t mean that we are eating rice the wrong way!

It refers to the stress and awkwardness of making yourself understood in a foreign language. The feeling you get when forced to speak in a different language and the anxiety of not being able to understand or be understood.

This concludes my guide to beautiful and meaningful Japanese words. Hope you enjoyed the article; if you did, please comment below and share it more widely. What are your favourite Japanese words mentioned above or not?

Want to learn some Japanese words before your next trip to Japan? Check out this blog post too:Â 30+ Useful Japanese phrases for travellers

Save This Post For Later On Pinterest

Credit photos: Canva & SecretMoona

Hi!

Beautiful in Japanese is 美しい (utsukushii) and beauty is 美しさ (utsukushisa).

But, if you want know some beautiful Japanese words, you’re in luck.

The language is full of words and phrases that are not immediately translatable into English. Aesthetic Japanese words that don’t have an English counterpart and require explanation.

In this guide, you’ll learn 55+ beautiful words and phrases. So, let’s jump in.

1. 木枯らし Cold, Wintry Wind

- Pronunciation:

- Kogarashi

“Kogarashi” is a chilly, cold, wintry wind. It lets you know of the arrival of winter. You know, the kind that sends the shivers down your spine and gives you goosebumps.

2. 木漏れ日 Sunlight filtering through the trees

- Pronunciation:

- Komorebi

When sunlight filters through the tree leaves and produces rays. You know that 木 stands for tree, 漏れ/もれ means leakage and the 日 kanji stands for the sun. So, tree leakage (of the) sun.

3. 物の哀れ Bitter-sweetness of fading beauty

- Pronunciation:

- Mono no aware

物/Mono means “thing.” And, “aware” looks like the English word, but it doesn’t have the same meaning or pronunciation. It means pity, sorrow or grief. So this refers to the “bittersweetness of fading beauty” – the acknowledged but appreciated, sad transience of things. Kind of like the last day of summer or the cherry blossoms – which don’t last long.

4. 幽玄 An awareness of the universe

- Pronunciation:

- Yuugen

Literally it means “subtle grace” or “mysterious profundity.” This word has different meanings depending on context. But most of the time, it refers to a profound awareness of the nature of the universe – the oneness of all things – to the point where it affects you emotionally.

Sound vague and odd? Well, don’t worry. To settle your mind, this word is not translatable and has no English equivalent… so if you’re confused, it’s okay.

5. 和 Harmony

- Pronunciation:

- Wa

This word means peace or harmony. It implies the importance to of avoiding conflict – so as to maintain the (Wa) harmony. And it refers to Japan and the Japanese way itself.

6. 改善 Continuous improvement

- Pronunciation:

- Kaizen

Literally, it means change for better. Whether one time or continuously – this is not implied or intended. It’s not until later that it become continuous improvement by the Japanese business world. Toyota kicked it off.

So, now, it’s just a word (used by businesses) to describe the process of “always improving” and getting better.

7. 紫 Purple

- Pronunciation:

- Murasaki

Yes, the color purple. Why did it make the list of beautiful Japanese words?

Simply because of how it sounds to the ear. Say it with me – murasaki! Okay, there’s more. Back in the old, old days– say around the year 1400 – this color was the color of the upper class and only high level officials and Imperial family could wear it. So, this color is a pretty big deal and a pretty beautiful Japanese word, in my opinion.

8. 森林浴 Forest Bathing

- Pronunciation:

- shinrin-yoku

So, 森林/shinrin means forest and 浴/yoku stands for bathing. And this refers to being immersed in a forest or talking a walk through the woods. It’s something to do to relax, reduce your stress and improve your health.

And studies confirm that this indeed lowers blood pressure and cortisol.

9. 奇妙 Strange, odd, or mysterious

- Pronunciation:

- Kimyou