Hey, what’s up everyone? One of the things that I aim to do here at Japanese Tactics is to help get people answers to their exact questions. I like to take this particular approach to writing, instead of just blogging about whatever’s on my mind at the time (although I will do that on occasion!).

How do I know what people want? I ask questions, I read people’s comments, and I have a few ways to see what questions people are looking for in Google Searches.

Interestingly enough, there are actually quite a few people out there who want to know: How Do You Say OLD MAN in Japanese?

Here’s the short answer: 老人 (roujin).

But it’s pretty rare when a language has only one way to say something. For example, how many different ways can you say OLD MAN in English?

- Old Man

- Old Guy

- Ancient Dude

- Gramps

- Old Geezer

See what I mean? Yeah there is that one basic way, but it’s totally plain vanilla. What if you wanted to wanted to add some flavor to it? They say “variety is the spice of life” after all.

So I wanted to give you some different words for OLD and some different words for MAN in Japanese so that you could expand your vocabulary and have a little fun at the same time.

After I go through each of these words individually, I’ll combine them together and provide some example sentences with audio. The best way to understand it is to see it in action, and then do it yourself. Let’s begin!

What is the Japanese Word for OLD?

The Japanese word for old is 古い (furui). This is an ‘i-adjective’ so it follows all those lovely rules when it comes to its different conjugations:

–Is old = 古いです (furui desu)

–Was old = 古かったです (furukatta desu)

–Is not old = 古くないです (furukunai desu)

–Was not old = 古くなかったです (furukunakatta desu)

And when you want to change from formal/polite speech to informal/casual speech all you have to do is drop the copula です.

formal/polite = 古いです

informal/casual = 古い

Whew, enough with the grammar!

The interesting thing about this kanji 古 is that it is a combination of the kanji for the number ten 十 , and also the kanji for mouth 口 . I believe in this situation, the mouth represents “generations of people.”

So ten generations is a very long time. And therefore, it’s old!

But here’s the only problem: 古い can’t be used with people. You’ll have to use a different approach when talking about old guys.

You could use 年を取っている (toshi o totte iru) to say “I am old” in Japanese.

This one is pretty interesting since a literal translation would be “I am (in the continuous action of) taking the age.”

That way of speaking sounds kind of weird in English. But if it helps you to remember the meaning, then it’s good to use it!

And to say ANCIENT in Japanese you would use the word 古代 (kodai). As you can see, this is a compound word that uses the kanji for old 古.

What is the Japanese Word for MAN?

The most common Japanese word that you will see used for MAN is 男 (otoko).

This kanji has some history baked into it. It is a combination of the kanji for rice field 田 and power 力. If you think about it, it was common back in the day for the men of the village to use their physical power to work all day long in the rice fields.

Gotta’ bring home the rice, right? No bacon here! 🙁

And this is the kanji that you’re gonna see used for “men” 男 when you need to use the public restrooms. FYI the one you will see for “women” is 女.

This kanji 男 brings the connotation of “the male gender” when it’s used as a ‘no-adjective’ in the words 男の子 (otoko no ko) meaning “male child” or “boy”, and 男の人 (otoko no hito) meaning “male person” or more simply “man”.

And there is another common word 男性 (dansei) that also means “man.”

This word is created by combining 男 for “male” and 性 for “sex/gender.”

I was talking with a native about these words the other day and I was told that 男の人 is kind of polite and would really only be used to describe other men.

If you were going to talk about yourself, as in “I am a man” then you would be more likely to use 男 or 男性.

Which Word to Use?

Unfortunately knowing how to say “old” and “man” in Japanese doesn’t really work as there are several special ways to say “old man.” Think of it as one single word, rather than two (like it is in English)

Use 老人 (roujin) when talking about someone else who is old.

Use 年を取っている (toshi o totte iru) when you want to say that you are old.

Use おじん (ojin) when you want to call someone something like “gramps.”

Use 翁 (ō) when you want to refer to him as a “venerable gentleman.”

Use 爺 (jiji) when you want to call him an “old geezer!”

Maybe once you’re in the hot springs, you might decide to strike up a conversation with one of the nice older gentlemen. He could be a simple man and describe himself like this:

- 俺は男性で、年を取ってるけど、まだ楽しみたい!

ore wa dansei de, toshi o totteru kedo, mada tanoshi mitai!

I’m a man and I am old, but I still want to have fun!

Here’s another example sentence that talks about old guys:

- 爺ちゃんはやっとのことで脱出した。

jiji-chan wa yatto nokoto de dasshutsu shita.

The old Geezer escaped, but with difficulty.

Now what do you do if you want to get the attention of an older guy, but you don’t know his name? Is there a word that translates to something like “mister” in Japanese?

As a matter of fact, there is!

For an older man, they use the word おじいさん (ojiisan). This is actually the word for “grandpa.” Or to be more specific: “someone else’s grandpa.”

If you read my earlier post on sisters then you’ll remember that people will often times call a young women お姉さん (oneesan) which means “older sister,” when they don’t know her name.

So you can deduce from these two examples that it is common in Japanese to use these kinds of words with people who’s names you don’t know.

Old Guys in Anime, Manga, and JRPGs

Have you ever noticed that there’s a lot of old guys in things like anime, manga, and JRPGs?

I’m talking about the Turtle Hermit, Master Roshi in Dragon Ball Z. Yes, the one who’s always reading pervy magazines!

I’m thinking of The Old Man in the original Legend of Zelda that tells you “it’s dangerous to go alone. Take this!” as he gives you your first sword for your grand adventure.

I’m talking about Obi-Wan Kinobi in the original Star Wars, who teaches Luke Skywalker about the powers of The Force!

Okay, that last one’s not from Japan!

What’s with this common thread you may ask? Well I’ve got an answer for ya: it’s The Hero’s journey.

You see, The Hero’s Journey is a pattern of narrative that gets used in an incredible amount of stories. Take a look at it here if you want to read more about it, but the basic gist is that a normal guy who becomes a hero will run into a mentor early on and will learn something valuable from this old guy that will help him out on his journey.

I highly recommend that you check out the whole process because once you understand it, you will start seeing the pattern used all the time!

Either way, you now know all about old guys in Japanese!

Words related to ages, people’s ages, in Japanese are tricky ones. This is because for every single word there seems to be a very similar word which is the wrong on. Even the phrase «years old» in English doesn’t translate word-per-word to Japanese.

Index:

- Counting Years Old

- Hatachi 二十歳

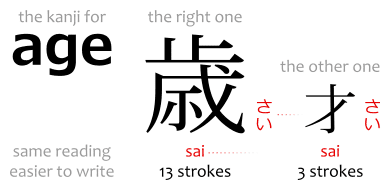

- Sai 歳 vs. Sai 才

- Twenties, Thirties, Forties, Fifties

- Words For Age in Japanese

- Aging and Getting Old

- Asking Someone’s Age in Japanese

If you tried to translate it word-per-word, you’d first need the word for «years» in Japanese. Like «20 years» which would be ni jyuu nen 20年. That, that nen, is a Japanese counter, and it goes without saying you’d need to know the numbers in Japanese to use it.

After that, watashi wa nijyuu nen 私は20年 would be «I’m 20 years.» Since I’m sure you aren’t a length of time worth 2 decades, that would be the wrong way to say it. We want to say «years old» so we need a word for that «old.»

However, Japanese doesn’t work that way. You can just say «X years» and suffix a word for «old» and have «years old.» Instead, you use the sai 歳 counter, which counts years of age specifically. That is, nen 年 counts «years,» and sai 歳 counts «years old».

So, to say «I am 20 years old» in Japanese, you’d say watashi wa ni jyuu sai 私は20歳. Except not, because the readings of the kanji get glued together, so it’d become nijyussai にじゅっさい or nijissai にじっさい instead. Except that that, too, would be the wrong way. Because the correct word for «20 years old» in Japanese is hatachi 20歳.

Counting Years Old

I’ll admit it. This is confusing. Basically, every single other age is read normally, see:

- issai 一歳

One year old - nisai 二歳

Two years old - sansai 三歳

Three years old. - yonsai 四歳

Four years old. - gosai 五歳

Five years old. - rokusai 六歳

Six years old. - nanasai 七歳

Seven years old. - hassai 八歳

Eight years old. - kyuusai 九歳

Nine years old. - jyussai 十歳

Ten years old. - jyuu issai 十一歳

Eleven years old. - jyuu nisai 十二歳

Twelve years old. - jyuu sansai十三歳

Thirteen years old. - jyuu yonsai 十四歳

Fourteen years old. - jyuu gosai 十五歳

Fifteen years old. - jyuu rokusai 十六歳

Sixteen years old. - jyuu nanasai 十七歳

Seventeen years old. - jyuu hassai 十八歳

Eighteen years old. - jyuu kyuusai 十九歳

Nineteen years old.

(as a matter of fact, zerosai ゼロ歳 would be «zero years old,» but you probably won’t find this word unless you are reading Saiki Kusuo no Psi-Nan 斉木楠雄のΨ難)

Hatachi 二十歳

But then, when it gets to 20, it’s not ni jyussai 二十歳, as one would expect, but hatachi 二十歳 which is totally different.

This is a «special kanji reading,» or jyukujikun 熟字訓, and it happened because the archaic word hata meaning «twenty (not specifically years old)» was used with the also archaic chi suffix centuries ago, before the introduction of kanji in Japan. So it kind of stuck. (source: 20歳はなぜ「はたち」)

From there on, the readings get normal again.

- nijyuu issai 二十一歳

Twenty one years old. - nijyuu nisai 二十二歳

Twenty two years old. - nijyuu sansai 二十三歳

Twenty three years old.

- san jyussai 三十歳

Thirty years old. - yon jyussai 四十歳

Forty years old. - go jyussai 五十歳

Fifty years old. - roku jyussai 六十歳

Sixty years old.

- hyakusai 百歳

One hundred years old

Sai 歳 vs. Sai 才

Now, I’m pretty sure when you looked at the sai 歳 kanji you thought: «how the ******* **** do you even write this thing?!» And you’re right, it’s a difficult kanji.

Which is why sometimes a simpler kanji, sai 才, is used in its place. Like this: jyuu hassai 18才, «eighteen years old» instead of jyuu hassai 18歳.

In this case, the difference between 歳 and 才 is exactly none. They are interchangeable. This is mostly because 歳 is taught in high-school while 才 is taught years earlier, meaning that when a middle-school student needs to write down his age he may not know the complex 13-stroke 歳 kanji but he may know the simpler 3-stroke 才 kanji which has the same reading, so that one ends up being used instead. In every other situation, you can’t replace 歳 with 才.

Twenties, Thirties, Forties, Fifties

Sometimes ages are not referred to as exact but as classes of ten. You don’t say «there’s something you have to learn by your 30th birthday,» you say «there’s something you have to learn by twenties.» In Japanese, this is said by using another counter, the one for «eras» (seriously), «generations» or «reigns:» dai 代.

- jyuu dai 10代

Tens - nijyuu dai 20代

Twenties - sanjyuu dai 30代

Thirties - yonjyuu dai 40代

Forties - gojyuu dai 50代

Fifties

And so on.

Do note that because this counter is meant for eras, it isn’t necessarily always about ages like above. For example, in Naruto ナルト, the «Third Hokage» would be san-dai-me hokage 三代目火影. Literally «Third Generation Hokage.» The words above can’t be used for random things either, only for years. You can’t say «tens of things» or something alike with them.

Another way to refer to tens of years would be the soji 十路 words: futasoji 二十路, misoji 三十路, yosoji 四十路, isoji 五十路, etc. These represent the ages twenty, thirty, forty and fifty respectively.

Words For Age in Japanese

Now we know how to say «years old» in Japanese, but how do you say «age»?

It depends.

The most literal way to say «age» (of people) is nenrei 年齢, but toshi 年 also may mean someone’s age in some cases. Do note that these words use the kanji for «years» (年) and not the one for «age» (歳), which only adds to the confusion.

Also note that toshi 年 can mean just «year,» as in any year. The word kotoshi 今年 means «this (current) year» for example. To avoid ambiguity, some authors will use the kanji for «age» with the toshi reading when they mean the age and not the year: toshi 歳.

In English, though we may not notice it, the word «age» has multiple different meanings. Most of the time it’s about someone’s age, but when it’s not, the word in Japanese becomes different. For example, jidai 時代 refers to a given span of the world’s age. A certain time. For example:

- kaizoku no jidai 海賊の時代

Age of pirates - mukashi wa souiu jidai dattanda 昔はそういう時代だったんだ

In the past it was that kind of age. (where that kind of stuff was normal)

Aging and Getting Old

The word toshi 年 is also part of other words about age, specifically about aging.

First off, to say someone’s older or younger than someone else, that is, an «elder» or a «junior» to him, the toshi word is used in combination with the up and down directions in Japanese to create toshiue 年上 and toshishita 年下, literally «year above» (elder) and «year below» (junior). This is slightly different from senpai 先輩 and kouhai 後輩 as it deals strictly with age.

Normally, to say respect your «elders,» relatively, you’d use toshiue, however, in some cases, specially in games, an absolute «elder» is used instead. «The elder of the village,» for example. In this case, the word would be roujin 老人, literally an «old person.»

In verbs, oiru 老いる means to «grow old» and so does the phrase toshi wo toru 年を取る, although it may sound kind of funny because the latter literally says «pick years» (then again, English has «get old»). These two verbs can also be used as adjectives when conjugated to the past: oita hito 老いた人 and toshi wo totta hito 年を取った人 meaning «old people» or, more literally, «people who have gotten old.»

It’s important to note that there’s no simple adjective word that means «old» in Japanese for people. The word furui 古い is an adjective, it means «old,» but you can’t use it with people, because it means some thing is old. Old clothes, old house, old words, etc. It isn’t used to talk about the age of people.

However, for some reason, there are adjective word to say «young» in Japanese. And not just one of them, either. First there’s wakai 若い, literally «young.» A wakai hito 若い人 is a «young person,» there’s also wakamono 若者, same thing. Then, there the adjective osanai 幼い, which means «very young,» younger than wakai, and found in that famous osananajimi 幼なじみ word, which means «childhood friend,» the kind of trope character that always does something in the plot.

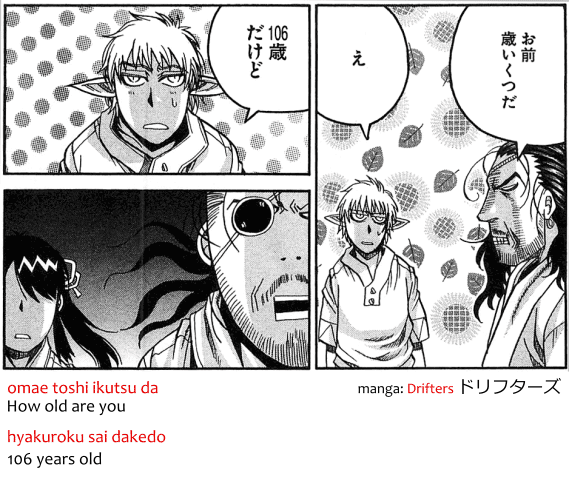

Asking Someone’s Age in Japanese

Finally, about asking someone’s age, there are a couple ways to go about it.

First off, in English we say «how old are you?» This is an adjective-measuring question, like saying «how tall is that building?» or «how fast is an unladen swallow?» In Japanese, something like that isn’t used and instead you’d ask how many years of age does a person have. See:

- toshi wa ikutsu desu ka? 歳はいくつですか?

otoshi wa ikutsu desu ka? お歳はいくつですか?

How old are you?

(note: the o prefix is usually used when talking about things of other people. In this case, of their age)

In the phrase above, we ask directly about the «years of age» of a person. A variation of this uses the person itself as the grammatical topic. See:

- anata wa ikutsu desu ka? あなたはいくつですか?

How old are you? (literary: how many are you?) - kare wa ikutsu des uka? 彼はいくつですか?

How old is he? - kanojo wa ikutsu desu ka? 彼女はいくつですか?

How old is she?

Another variation of this uses no topic at all. Just an o prefixed ikutsu.

- oikutsu desu ka? おいくつですか?

How old are you?

There must be a hundred ways to use this word to say the exact same thing You can use da instead of desu ka, drop the topic particle, use a different pronoun, etc. The ikutsu alone stays the same.

Another way of asking someone’s age in Japanese is using a counter question through the sai 歳 counter, the same way it would be done with any other counter. For example:

- anata wa nansai desu ka? あなたは何歳ですか?

How old are you? (literary: how many years old are you?) - kare wa nansai desu ka? 彼は何歳ですか?

How old is he?

Note: anata あなた, «you,» or whoever it may be, is often omitted in speech and inferred from context. So nansai desu ka? 何歳ですか is a valid phrase in certain contexts even though it sounds like someone’s just saying «how old?»

How Old Will You Be?

Sometimes, specially when people talk about their «birthdays,» tanjoubi 誕生日, the talk shifts from how old they are right now to how old are they going to be after their special day. In this case, the verb «to become,» naru なる, is often used to ask future questions.

- kotoshi de oikutsu ni narundesuka? 今年でおいくつになるんですか?

How old are [you] going to be this year?

You may already know that Japan has the world’s longest life expectancy. But did you know that Japanese are also the most well prepared for their longevity with a vast array of special words for different ages? Although many (umm, almost all?) of these words are not commonly used, they’re still fun to know. And you never know what’s going to come up on a Japanese game show or in your izakaya parties. Here’s the list!

The only one you absolutely must use

20 years old : 二十歳 (はたち)

In Japanese, you don’t say にじゅっさい, you say はたち.

Okay, if you’re just learning Japanese to communicate or for travel, you can stop here and you won’t be missing any vital information. The rest of these words are obscure at best and archaic at worst even for native Japanese (seriously, we’re talking post-JLPT-1級 level, here).

But if you’re like me and the thought of “archaic Japanese” gives you a jolt of excitement, or if you’re just curious, read on…

Words based on the calendar or life events

We’ll start with a collection of age words that are based on perceived or actual life events.

- 10 : 辻髪 (つじかみ) – This is the name of a Japanese children’s hair style.

- 15 : 笄年 (けいねん) – Girls only. 15 is the age when they could start using hairpins in their hair.

- 20 : 丁年 (ていねん) – Men only. Under the Ritsuryo law system, this was the age when a man became subject to official assignments (丁) (e.g. to X days of labor or taxes).

- 40 : 初老 (しょろう) – This is when you start (初) becoming old (老). In English, we would say “over the hill.”

- 50 : 中老 (ちゅうろう) – You’re in the middle (中) of becoming old.

- 50 : 艾年 (がいねん) – The age when your hair begins to turn white like a mugwort plant (艾:よもぎ)

- 60 : 丁年 (ていねん) -The word for the year a person entered the official assignments system was also used for the year when one left it.

- 60: 還暦 (かんれき) — Literally meaning “revolving the calendar”, because the 10 calendar signs (十干/じっかん) and the 12 astrological signs (十二支/じゅうにし) realign every 60 years.

- Note: 還暦 is 61 years old under the “counting age” system. (See Below)

- 120 : 大還暦 (だいかんれき) – The “big calendar revolution”, this means you made it twice around the 60 year cycle. Congratulations!

One from a Chinese poem

- 70 : 古希 (こき)

This age word is from a famous poem by Tang Dynasty Chinese poet Du Fu (Japanese: 杜甫/とほ). In Japanese translation, the relevant lines are:

酒債は尋常行く処に有り 人生七十古来稀なり

There is an English translation of this poem (曲江: Winding River) available, if you’re interested.

One for Shogi players

-

将棋 (しょうぎ) : a chess-like Japanese board game

81 : 盤寿 (ばんじゅ) — Because the 9×9 Shogi board has 81 places.

Kanji play

When your language has thousands of highly complex characters, and you’re bored in the winter with nothing but a bottle of sake, word games are just a natural occurrence. Hundreds of years of Japanese ingenuity brings us these linguistic gems:

- 48 : 桑年 (そうねん) – The old form for 桑 is 桒, which can be broken down as four 十 characters and one 八 character, adding up to 48.

- 61 : 華寿 (かじゅ) – Because 華 can be seen as 6 十 characters and a 一.

- 66 : 緑寿 (ろくじゅ) – Because 緑 can be read as ろく, the same as 六 (6).

- 77 : 喜寿 (きじゅ) – The grass script form for 喜 is 㐂, which is actually 3 sevens, but if you pretend one of them is a 10 it becomes 七十七 = 77.

- 80 : 傘寿 (さんじゅ) – The abbreviated form of 傘 is 仐, which is 八十= 80.

- 81 : 半寿 (はんじゅ) – Because 半 can be broken down as 八 + 十 + 一 = 八十一 = 81.

- 88 : 米寿 (べいじゅ) – Because the kanji can be broken down as 八+十+八 = 八十八 = 88.

- 90 : 卒寿 (そつじゅ) – Because the abbreviated form of 卒 is 卆, which is 九+十 = 九十 = 90.

- 95 : 珍寿 (ちんじゅ) – Because the left side of the kanji can be 十二 and the right 八三 (83 + 12 = 95)

- 99 : 白寿 (はくじゅ) – Because if you take one (一) away from the kanji for 100 (百), it becomes 白

- 100 : 百寿 (ももじゅ) – This one’s obvious… (百 = 100)

- 108 : 茶寿 (ちゃじゅ) – Because the kanji can be broken down as 十十 (20) plus 八十八 (88)

- 111 : 皇寿 (こうじゅ) – Because 白 is understood to be 99 (detailed above), and 王 is 一+十+一 = 12. 99 + 12 = 111

- 111 : 川寿 (せんじゅ) – Because 川 looks like 111.

- 119 : 頑寿 (がんじゅ) — Because 二 + 八 (元) = 10 and 百 + 一 + 八 = 109. 109 + 10 = 119.

- 120 : 昔寿 (せきじゅ) – Because 廿 (= 十十 = 20) + 百 (100) = 120.

And just to make sure that we never, ever run out of words…

- 1001 : 王寿 (おうじゅ) – Because 王 can be broken down as 千 + 一.

- 1007 : 毛寿 (もうじゅ) – Because 毛 can be broken down as 千 + 七.

- 1082 : 科寿 (かじゅ) – Because 科 can be broken down as 千 +八 + 十 + 二

These words (that include 寿), are collectively known as 賀寿 (がじゅ).

Chouju

In Japanese, longevity (長寿/ちょうじゅ) is broken down into 3 stages, but there’s differences of opinion over which specific ages they indicate, so you might want to think of these words just as general estimates.

- 下寿 (かじゅ) : 60… or 80

- 中寿 (ちゅうじゅ) : 80… or 100

- 上寿 (じょうじゅ) : 100 or higher

Haka: a word with two ages?

破瓜 (はか) is another kanji/wordplay term for age, but is unusual because it means a different age when referring to different genders. The kanji 破 means to split or tear something, and apparently 瓜 (the kanji) can be split into two 八 八 characters (personally, I don’t see it). Hence:

- 瓜 = 八 + 八 = 16 (women)

- 瓜 = 八 x 八 = 64 (men)

Soji

Japan also has a whole class of words ending in 十路 (そじ) to count age in tens. In really old Japanese, (until about the Heian period) these words were also also used in counting regular objects.

- 20 : 二十路 (ふたそじ)

- 30 : 三十路 (みそじ)

- 40 : 四十路 (よそじ)

- 50 : 五十路 (いそじ)

- 60 : 六十路 (むそじ)

- 70 : 七十路 (ななそじ)

- 80 : 八十路 (やそじ)

- 90 : 九十路 (ここのそじ)

Confucius says

The Confucian text The Classic of Rites also specifies a collection of words for specific ages. Sorry ladies, you’re only allowed to use the ones from 50 on.

- 10 : 幼学 (ようがく)

- 20 : 弱冠 (じゃっかん)

- 30 : 年壮 (ねんそう)

- 30 : 壮室 (そうしつ) (if you have a wife)

- 40 : 強仕 (きょうし)

- 50 : 杖家 (じょうか)

- 60 : 杖卿 (じょうきょう)

- 70 : 杖国 (じょうこく)

- 80 : 杖朝 (じょうちょう)

- 81 : 漆寿 (しつじゅ)

The stages of life

You may have heard the words 少年 (しょうねん) or 青年 (せいねん) before, but did you know that these words point to different, generally understood stages of life? Exactly what ages these words refer to is not set in stone, but some documents from the Japanese Ministry of Health use the following groups:

- 0 to 4 : 幼年期

- 5 to 14 : 少年期

- 15 to 24 : 青年期

- 25 to 44 : 壮年期

- 45 to 64 : 中年期

- 65 onward : 高年期

Note about 壮年 (そうねん): 壮 here means to prosper or be active. 壮年 can refer either to age 30 specifically, or to all of a person’s active and productive years (generally starting at age 30).

Confucian age words

More? Yes, Japan also offers another selection of age words based one passage from the Confucian analects, in which he writes:

At fifteen my heart was set on learning; at thirty I stood firm; at forty I had no more doubts; at fifty I knew the mandate of heaven; at sixty my ear was obedient; at seventy I could follow my heart’s desire without transgressing the norm.

Source: Electronic Library: The Analects of Confucius (look for passage 2:4)

- 15 : 志学 (しがく)

- 30 : 而立 (じりつ)

- 40 : 不惑 (ふわく)

- 50 : 知命 (ちめい)

- 60 : 耳順 (じじゅん)

- 70 : 従心 (じゅうしん)

Note: these words are only for men.

Counting age the Asian way

The traditional way to count your age in East Asian countries is to start at one, not zero like we do in the west, and to increment by one at the end of every calendar year instead of on the individual’s birthday. The system is known in Japanese as 数え年 (かぞえどし) but Japan and most other Asian countries nowadays have very thoroughly adopted the western counting method (満年齢・:まんねんれい), with the exception of Korea where the old counting method is still the de facto system.

One relic of the old counting system in Japan is the Coming of Age celebration, where boys and girls who turned 20 during the previous year all get to celebrate their passage into adulthood. Read the wikipedia article on Asian age counting if you’re interested.

Two kanji for “sai”

While we’re talking about age, I figured it would be good to include a short word about 歳 and 才. Both of these characters are read さい, both mean age. What’s the difference? 才 was originally an abbreviated form of 歳, so you can think of it as less “official” than 歳. People often use 才 because it’s easier to read and write, but on government documents and official application forms, you will always see 歳 used.

Interestingly, if you’re talking about the age of an animal, you should write 才. Using 歳 with an animal apparently makes the animal seem more human, so depending on your point of view, you could use it with monkeys and such.

Credit where credit is due

Here I’ve compiled a list of the links I referred to when I was locating and organizing all this information. Although I’m sure you’ll never need to know any more than I’ve covered here, there are a couple alternate forms and other super-obscure words out there (particularly on the Wikipedia page) if you’re for some reason totally crazy about this topic.

- 年齢 on Wikipedia (JP)

- チョット雑学:数を表す文字

- 「寿」模擬授業指導案

- 年齢の名称・異称

- 年齢を表す言葉 (the difference between 歳 and 才)

advanced age vocabulary Posted under Language & Study by Nihonshock.

Learn a little Japanese everyday with the free Japanese Word of the Day Widget. Check back daily for more vocabulary!

兄 (あに) older brother (noun)

兄が妹を抱いている。

あにがいもうとをだいている。

The older brother is holding his younger sister.

私には、2人の兄がいて、二人とも警察官です。

わたしには、ふたりのあにがいて、ふたりともけいさつかんです。

I have two older brothers, and both are police officers.

意地悪な兄

いじわるなあに

mean older brother

Own a blog or website? Share free language content with your readers with the Japanese Word of the Day with Audio Widget. Click here for instructions on how to embed and customize this free widget!

The word for brother in Japanese depends on whether they are older or younger than you. Your older brother is 兄 (ani) in Japanese, while younger brother is 弟 (otouto). There is no way to say brother in Japanese without implying the sibling’s age.

7 Ways to Say Brother in Japanese

Let’s look at 7 ways Japanese people say brother, and examples of each. If you want to know how to learn more Japanese quickly, be sure to check out our learning Japanese roadmap!

1. 兄 (Ani) – One’s Older Brother

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, 兄 (ani) is the general term for your older brother in Japanese. Ani is the word you would use to talk about your older brother to other people. It is a fairly polite word but doesn’t come across as overly formal. Ani is appropriate for any company or conversation.

Example:

- 私の兄は先に学校へ行きました。

(Watashi no ani wa saki ni gakkou e ikimashita.)

My older brother went to school ahead of me.

2. お兄さん (Onii-San) – Big Brother

While お兄さん (onii-san) has the same kanji as ani, its reading is different. Onii-san means big brother in Japanese. It’s more often used to speak to one’s big brother, although it’s acceptable to say onii-san when referring to someone else’s brother in casual or formal conversation.

Onii-san can also be used as a title for young men, although this rule is typically confined to children and the elderly. “Tough guys” may also call a young man onii-san; the nuance to this title is often friendly and casual.

Variants of the word onii-san are 兄さん (nii-san) and お兄ちゃん・兄ちゃん (onii-chan・nii-chan). These titles are more affectionate, holding the same nuance as the English nickname bro or big bro. It also common to say the person’s name or nickname before onii-san. For example, まさお兄さん (Masao nii-san), たくや兄ちゃん (Takuya nii-chan), or even just using nii, like さとし兄 (Satoshi nii).

Examples:

1. お兄さんはどこですか?

(Onii-san wa doko desu ka?)

Where is your brother?

2. 兄さん!ご飯、できたよ!

(Nii-san! Gohan, dekita yo!)

Bro! Dinner’s ready!

3. あら、お兄さん、荷物を持ってくれてありがとうね。

(Ara, onii-san, nimotsu o motte kurete arigatou ne.)

Why, thank you for carrying my luggage, young man.

3. 兄貴 (Aniki) – One’s Older Brother, One’s Senior

Like onii-san, 兄貴 (aniki) is a way to say older brother in casual Japanese. Aniki may have been initially limited to formal Japanese, but it is currently considered impolite to use the word in formal conversations. Aniki is sometimes used to speak to one’s older brother, although this is often done as a joke.

兄君 (ani-gimi), which was the Samurai’s respectful word for 兄 (ani), was used in the times of warlords in Japan. 兄貴(aniki) is an abbreviation for 兄君 (ani-gimi). However, the kanji “貴 (ki)” does not have much of meaning in this case. It is believed that using 貴 (ki) is a change that happened recently.

Aniki can also be used to refer to one’s senior within a work-related or social group. When used for an older brother, aniki should be limited to casual conversation with people in your circle or age group.

Example:

1. 兄貴が試験に物の見事に合格した!母ちゃんと父ちゃんはめっちゃ喜んでいる。

(Aniki ga shiken ni mono no migoto nigoukaku shita! Kaa-chan to tou-chan wa meccha yorokondeiru.)

My brother passed his exams with flying colors! Mom and Dad are thrilled.

4. 弟 (Otouto) – (One’s) Younger Brother

弟 (otouto) means little brother in Japanese. It is always used when talking about your little brother (to someone else). Japanese people may call their older brothers onii-san, but they will always refer to their younger brothers by name and never by otouto-san. This may have to do with the role that age plays in Japan’s social hierarchy.

However, when you add “san” to otouto (otouto-san) it becomes a polite way to refer to someone ele’s younger brother. See example #2 below.

Examples:

1. 弟がいます。ジェームスと言います。

(Otouto ga imasu. Jeemusu to iimasu.)

I have a little brother. His name is James.

2. スミスさんの弟さんは東京に住んでるんですよね?

(Sumisu san no otouto-san wa toukyou ni sunderun desu yo ne?)

Mr. Smith, your younger brother lives in Tokyo, right?

5. 兄上 (Ani-Ue) – Honored Older Brother

兄上 (ani-ue) is an archaic way to say older brother in Japanese. The title was mainly used within samurai households of pre-Meiji Japan.

People of the day might refer to their older brothers as ani-ue (literally honored brother) or the more respectful お兄様 (onii-sama). However, in modern Japanese, 兄上 (ani-ue) sounds out of place. You might find it in period literature or other media.

お兄様 (onii-sama) on the other hand is still used in formal situations (to address someone else’s or even your own older brother) and when writing letters.

Example:

- 兄上、刀を持ってきました。

(Ani-ue, katana o motte kimashita.)

Honored brother! I have brought your sword!

6. 兄弟 (Kyoudai) – Brothers

Many Japanese people mistakenly use the word 兄弟 (kyoudai) to mean “siblings” in Japanese. The original meaning of kyoudai is male siblings or brothers*. The meaning is in the kanji: 兄 (older brother) and 弟 (younger brother).

That said, kyoudai is implicitly a plural word. You can’t say 私の兄弟 (watashi no kyoudai) to mean my brother. It will always mean my brothers. Kyoudai is a useful word for describing your family members or home life to someone else.

*Important Note: While kyoudai is made up of the kanji for older and younger brother, it can be used with girls too. It’s also used when you want to ask someone if they have any siblings or inquire how many siblings they have (example #3 and 4 below).

For example, you could use it for:

- 男(の)兄弟 (otoko (no) kyoudai): male sibling(s)

- 女(の)兄弟 (onna (no) kyoudai): female sibling(s)

Examples:

1. 三人兄弟です。

(San nin kyoudai desu.)

I am one of three brothers.

2. うちの兄弟は二人とも軍人です。弟はまだ訓練中なんですけどね。

(Uchi no kyoudai wa futari tomo gunjin desu. Otouto wa mada kunrenchuu nan desu kedo ne.)

My brothers are both in the military. My younger brother is still training, though.

3. 兄弟はいますか?

(Kyoudai wa imasu ka?)

Do you have any siblings?

4. 何人兄弟ですか?

(Nan nin kyoudai desu ka?)

How many siblings do you have?

Other Words for Siblings

There are actually several words to describe siblings, but most of them are not common (except for shimai). You can use these to impress your Japanese friends instead!

| Japanese | Romaji | English Translation |

| 兄姉 | keishi | older brother and older sister |

| 兄妹 | keimai | older brother and younger sister |

| 姉弟 | shitei | older sister and younger brother |

| 姉妹* | shimai* | sisters; older sister and younger sister |

| 弟妹 | teimai | younger brother and younger sister |

*Note: 姉妹(shimai) is the only commonly used word these days.

7. 義理の兄・義理の弟 (Giri no Ani/ Giri no Otouto) – Brother-in-Law

If you wish to refer to your brother-in-law in Japanese, you can use either 義理の兄 (giri no ani) or 義理の弟 (giri no otouto). Of course, this depends on your brother-in-law’s age; remember that ani is an older brother, and otouto is a younger brother.

However, you don’t use 義理の兄 or 義理の弟 when you are speaking to your older or younger brother-in-law directly. These are only used when you are talking about your brother-in-law to people other than your family. When you want to talk to your younger brother-in-law, you would call them by their name. You don’t call your younger brother-in-law (or real younger brother) 弟 (otouto).

Here’s the interesting part. When you talk to your older brother-in-law directly, you can either call them by their name or onii-san. This is exactly the same as what you would call your real older brother, but there’s a special kanji for your brother-in-law.

- The kanji for an older brother-in-law (when speaking to him directly or speaking about him to your family) is: お義兄さん (onii-san)

- The kanji for older brother (related by blood) is: お兄さん (onii-san)

Even though there is one extra character in the kanji for an older brother-in-law, (お義兄さん vs. お兄さん) the reading is the same as お兄さん (onii-san).

There is also another way to say older and young brother-in-law in Japanese.

- 義兄 (gikei): Older brother-in-law

- 義弟 (gitei) : Younger brother-in-law

These two terms have the same meaning as 義理の兄 (giri no ani) or 義理の弟 (giri no otouto), but are more formal and mostly used in writing.

Example:

- I had dinner with my older brother-in-law last night.

昨夜、義理の兄と食事をしました。

(Yuube, giri no ani to shokuji o shimashita.)

Conclusion

There aren’t as many words for brother in Japanese as there are for mother or father, but the rules are a bit more specific. Remember the difference between older brother (兄, ani) and younger brother (弟, otouto), and you’re ready to go! If you want to learn how to speak Japanese naturally, check out more of our free guides. If you’re looking for the best program or lessons to improve your Japanese, we highly recommend Japanesepod101.

How do you say brother in your language? Let us know in the comments! Thank you for reading our article on how to say brother in Japanese.

How to Use

Input a Japanese word (or phrase), and this tool will return its synonyms for each sense/definition of the word (with a bit of overlap across some senses due to the differences in the wordings). It’s recommended to input a word in kanji (for the purpose of disambiguation). The synonyms are sorted based on the (semantic) similarity to the input word. The result may also include some blog posts of mine that are relevant to the input word (if there are any).

* I’m planning to refine this tool further (e.g. suggest synonyms for words given context). If you find some critical errors that need fixing ASAP, or if you have any suggestions/ideas to improve this tool, let me know via social media (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) or the contact page.

Details of the Options

- Show furigana: untick this box if you don’t need furigana for each synonym

- Similarity Filtering: Select “Strong” if you want to discard words that are not very (semantically) similar to the input word, and “Disable” if you want to see all the relevant words. The default option “Mild” goes in the middle.

- Frequency Filtering: Select “Strong” if you want to discard rare/uncommon words (recommended if you’re not interested in advanced words), and “Disable” if you want to see all words (some of which may be useless unless you want to be a wordsmith in Japanese). The default option “Mild” goes in the middle.

Both filtering options determine how many synonyms are shown in the result. If the result is sparse, try disabling either (or both) of them.

Acknowledgement

This tool employs two open-source Japanese lexicon databases, namely Japanese Wordnet (dubbed “Dictionary 1”) and JMDict (dubbed “Dictionary 2”). These resources are accessible through the links below.

- Japanese Wordnet (vXX) © 2009-2011 NICT, 2012-2015 Francis Bond and 2016-2017 Francis Bond, Takayuki Kuribayashi (linked to http://compling.hss.ntu.edu.sg/wnja/index.en.html)

- http://www.edrdg.org/wiki/index.php/JMdict-EDICT_Dictionary_Project

Other Tools

- Japanese Furigana Generator and Dictionary Lookup

This tool automatically assigns furigana to each kanji word in an input sentence, and also shows their definitions retrieved from JMDict.

- Japanese Gairaigo and Wasei-Eigo Converter/Generator

This (bit of a gag) tool automatically converts Japanese words into gairaigo (外来語, “loanwords”) written in katakana, and vice versa (e.g. 気さくな歌手 ↔ フレンドリーなシンガー, ハイパフォーマンス ↔ 高性能).

Relevant Blog Posts

If you’re the kind of a person who loves exploring synonyms (like me), the following posts may pique your interest:

- 40 Ways of Saying “Many/Much” in Japanese (Ooi, Ippai, Takusan, …)

- 30+ Japanese Words for “Very”: Synonyms of とても (totemo)

- Boku, Ore, Watashi, Atashi: 15 Japanese Person Pronouns

- 20 Japanese Words For Various Types of Rain

- 7 Ways of Saying/Writing よろしく (yoroshiku) in Japanese

- 50 Japanese Words and Idioms about Love & Relationship

- 5 Meanings of 気 (ki) and 30 気-related Phrases/Idioms

- List of 50+ Japanese Words to Describe Personality

- 30+ Essential Japanese Words to Describe Food

- Japanese Money-Related Idioms and Slang Words

- 40 Funny Japanese Old Slang Words to Sound like Oyaji (Old Men)

- Ashita, Asatte, Shiasatte, Yanoasatte: 13 Japanese Words Describing Dates

- 8 Funny and Cute Japanese Cat Idioms

And see more posts that introduce various words based on a particular topic here

In Japanese, the counter sai is used to express how old one is. It can be written with two different kanji: the traditional 歳 and the simplified and most commonly used 才.

To ask someone «how old are you?,» you can say:

- Nan sai desu ka (何歳ですか);

- Or in a more formal way, O ikutsu desu ka (おいくつですか).

The answer will be constructed with the number corresponding to the age followed by sai, then desu for politeness.

For example, to reply «I am 25 years old,» say: (Watashi wa) nidjugo-sai desu ((私は) 二十五歳です。)

The table below is a useful reminder on how to say age:

| In Japanese | Pronunciation | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 一歳 | issai | 1 year old |

| 二歳 | ni-sai | 2 years old |

| 三歳 | san’-sai | 3 years old |

| 四歳 | yon’-sai | 4 years old |

| 五歳 | go-sai | 5 years old |

| 六歳 | roku-sai | 6 years old |

| 七歳 | nana-sai | 7 years old |

| 八歳 | hassai | 8 years old |

| 九歳 | kyuu-sai | 9 years old |

| 十歳 | djuussai or djissai | 10 years old |

| 十一歳 | djuuissai | 11 years old |

| 十二歳 | djuuni-sai | 12 years old |

| … | … | … |

«20 years old» is the only phonetic irregularity and is pronounced hatatchi (二十歳). The counter sai is omitted despite being used in the written form. If you are 20 years old, you will say: Hatatchi desu (二十歳です。)

To say «and a half,» just add han (半) after sai. For example, «I am two and a half years old» is translated as Ni-sai han desu (二才半です).

|

JAPANESE SYMBOLS |

|

||

|

|

PRIVACY POLICY |

Japanese symbols (C) 2009. Some Rights Reserved, Free Japanese Symbols