I’m going to answer your question from the point of view of interpreting what’s said in the video, specifically… I think this is one of the main points of your question and I think understanding that will help you understand the wonderful world that is «who vs whom».

Let’s look at what she says, first:

Many writers believe that ‘whom’ is on its way out because it can sound very pompous.

As you’ve seen in the comments, there are differing opinions on this… my personal feeling is that, in the relaxed, informal world of spoken English, this is more likely and in the more formal world of written English, it’s less likely to feel pompous.

Some even believe it’s circling the drain.

Probably true to some degree. Note she says «some»… she doesn’t say «it’s widely believed to be circling the drain» — the idiom here meaning it’s on the way out of popular use.

As I’ve stated in a comment, if you gave the average American a question about whether «who» or «whom» was appropriate in a series of sentences, they’d likely get it wrong. I probably get it wrong occasionally.

However, it is still used in expressions like ‘to whom it may concern’.

Yes… but it’s a bit reductive to imply that this is the only place it’s regularly used. I’d argue this is simply a better-known idiom, so more people are likely to know that this is an example of the correct usage.

In the sentence ‘the girl whom you’ve been dancing with is on her way to the top’

There’s a couple things about this sample sentence that I feel are suboptimal:

- She’s split the preposition off of the object, «whom», by rearranging the sentence.

- I, personally, wouldn’t use either «who» or «whom» in this particular arrangement of the sentence.

Better versions of the sentence (in my mind) would be to either omit the pronoun entirely

the girl you’ve been dancing with is on her way to the top

or to keep the preposition before the object

the girl with whom you’ve been dancing is on her way to the top

Now, at least, including the pronoun makes some sense to me. I still prefer the version without «whom» as this version feels a bit odd or stilted to me.

I suppose the rearrangement could be an Australian construction but I’m not sure.

most writers would use ‘who’ rather than ‘whom’, and it’s fine to do that.

This is, I think, where the main crux of the question comes in. I think it’s bad teaching to say «most writers do X»… I disagree that «most writers» would use the construction in her sample. Regardless of that, she says «it’s fine to do that»… and that is true. It may be a technically ungrammatical choice to use «who» but it is not an uncommon actual use.

That being said, she only says «it’s fine to use who in place of whom», which is generally true… what she does not say is «don’t use whom».

So, in relation to the two options in your question, the answer is, «neither«. You are quite welcome to use (or continue to use) «whom» appropriately. There is no reason to intentionally use «who» when you know that «whom» is correct. If you’re unsure which is correct, it’s acceptable in many circles to use «who» in all cases… but don’t be startled if someone corrects you.

From my point of view, saying «to who were you speaking» sounds wrong… because it should be «whom». There are some great references in our network for proper usage of who and whom and encourage you to check them out for more information.

Who and whom are wh-words. We use them to ask questions and to introduce relative clauses.

Who as a question word

We use who as an interrogative pronoun to begin questions about people:

Who’s next?

Who makes the decisions here?

Who did you talk to?

We use who in indirect questions and statements:

The phone rang. She asked me who it was.

Can you tell me who I should talk to.

I can’t remember who told me.

Emphatic questions with whoever and who on earth

We can ask emphatic questions using whoever or who on earth to express shock or surprise. We stress ever and earth:

Whoever does she think she is, speaking to us like that? (stronger than Who does she think she is?)

Who on earth has left all this rubbish here? (stronger than Who has left all this rubbish here?)

Who in relative clauses

We use who as a relative pronoun to introduce a relative clause about people:

The police officer who came was a friend of my father’s.

He shared a flat with Anne Bolton, who he married, and eventually they moved to Australia.

Whom

Whom is the object form of who. We use whom to refer to people in formal styles or in writing, when the person is the object of the verb. We don’t use it very often and we use it more commonly in writing than in speaking.

We use whom commonly with prepositions. Some formal styles prefer to use a preposition before whom than to leave the preposition ‘hanging’ at the end of the sentence:

Before a job interview it is a good idea, if you can, to find out some background information about the people for whom you would be working. (preferred in some formal styles to … about the people whom you would be working for)

Over 200 people attended the ceremony, many of whom had known Harry as their teacher.

We use it in relative clauses:

She gave birth in 1970 to a boy whom she named Caleb James.

We use it in indirect questions and statements:

He didn’t ask for whom I had voted.

He told me where he went and with whom. (preferred in some formal styles to He told me where he went and who with.)

See also:

-

Relative clauses

-

Questions: interrogative pronouns (what, who)

-

Indirect speech: reporting questions

-

Prepositions

-

Relative pronouns: who

-

Relative pronouns: whom

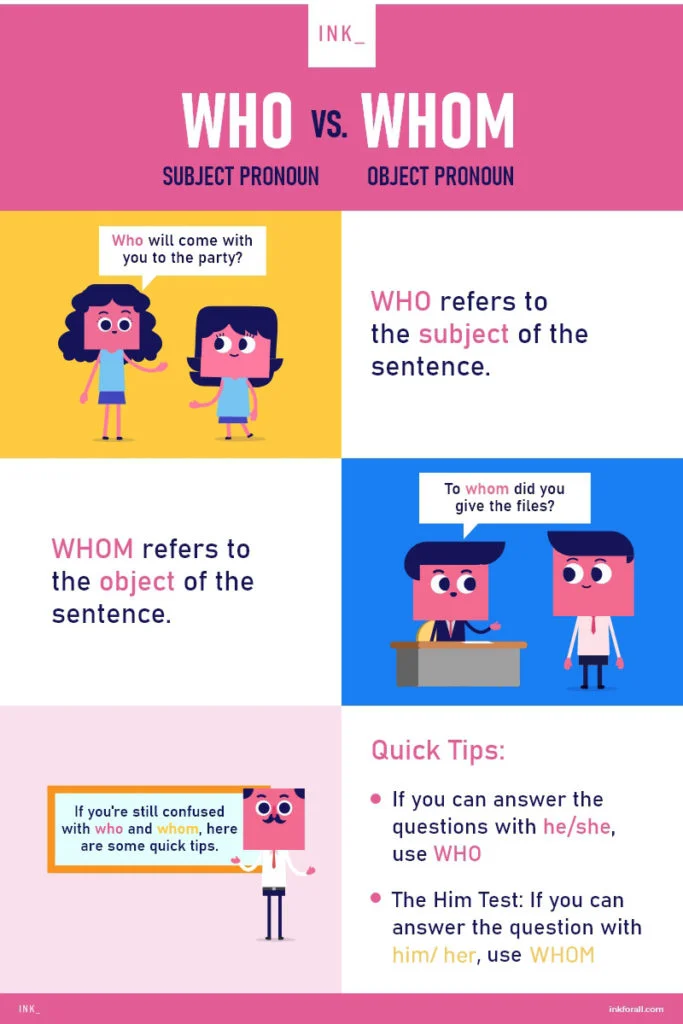

Who and whom are two words that sound very much alike. However, that similarity just makes when to use who vs. whom all the more confusing.

Main Who vs. Whom Takeaways:

- Who and whom are both pronouns.

- When you’re referring to the subject of the sentence, use who.

- Confirm you’re using the correct pronoun by replacing who with she/he/they.

- When your’re referring to the object, use whom.

- Confirm you’re using the correct pronoun by replacing whom with her/him/them.

- Sometimes you may have to break the who or whom rule to make your content more readable. Or, to prevent awkward and unnatural phrasing.

In this super easy guide, we’ll show you a few simple tricks to remember the difference and use both pronouns like a pro, every time. Also, you’ll see both in action with tons of who vs. whom examples. Don’t forget to test your skills with our quick quiz at the end of this article.

How Do You Use Whom?

You should use whom to refer to the object of a verb or a preposition. Here’s a quick and easy trick to be sure whom is the correct pronoun to use: Replace whom with him or her. If the sentence still makes sentence and is grammatically correct, thenyou know whom is the correct choice.

On the other hand, if he or she sounds better, then you should use who instead. You can remember this trick by associating the “m” in him with the “m” in whom. Another clue is to look for a preposition. For example, whom usually follows a preposition.

How Do You Use Whom in a Sentence?

Here are examples of how to use whom in a sentence:

Remember: The “m” in him goes with the “m” in whom. If you can answer the question with him, then use whom.

What’s the Difference Between Who’s and Whom?

Aside from spelling, who’s and whom have different functions in a sentence. To begin with, who’s is a contraction. Meaning, it’s a two-word term joined together by an apostrophe. It could mean who is or who has. On the other hand, whom is a pronoun and often acts as the object of a verb or preposition.

Here are some examples of how to use who’s in a sentence:

Who vs. Whom: They/Them?

Just like you can use he/him to confirm whether to use who/whom, you can also use they/them. This is because who and whom can represent singular pronouns like he and him as well as plural pronouns like they and them. For plural pronouns, replace who with they. If the sentence is still grammatically correct, then you know that who is the correct pronoun. Conversely, if them sounds better, then you know that whom is the correct pronoun to use.

Remember: If you can replace who or whom with he/she/they, then you should be using who.

Who vs. Whom Example Sentences?

1. Is Many of Whom Correct?

Yes, the phrase many of whomis correct to use whom instead of who. This is because you should use whom to refer to object of a verb or preposition. Since of is a preposition, whomis the correct pronoun to follow it. Another way you can confirm if whom is correct is to replace it with another pronoun like him, her, or them. If the sentence is still grammatically correct, then whom is correct.

2. Who or Whom I Worked With?

The ideal answer is with whom I worked. Whom goes with the object of the verb or preposition in a sentence. Since this phrase contains the preposition with, the most correct way to craft this sentence is using whom. Test if whomis correct by replacing it with him. Does the sentence still make sense? Then whom is the best pronoun to use.

3. Who I Live With or Whom I Live With?

Whom I live with or with whom I live are the correct ways to phrase this. The rule is that who refers to the subject of the sentence while whom refers to object of the verb and or the preposition. Here, we have the preposition with and the verb live. Both of these refer to the person you live with, not the subject of the sentence (I). For this reason, whom is the correct pronoun. Confirm this by rewriting the sentence to use the pronouns him/her/them. If the sentence is still correct, then you know that whom is the correct choice.

4. Who I Admire or Whom I Admire?

Here, the correct answer is whom I admire.This is because we use whom to refer to the object of a preposition or verb. In this phrase, there is no preposition. However, there is a verb: admire. Whom is the object of this verb. In other words, whom receives the action of you admiring. You can confirm that whom is correct because you can replace it with him and the sentence is still grammatically correct.

5. Who I Hate or Whom I Hate?

For this example, whom I hate is the correct phrasing. This is because whom usually refers to the object of a preposition or a verb. We don’t have a preposition in this phrase. But, we do have the verb hate. What’s more, whom is receiving the action of hate. This makes whom the object of the hate.

Since whom is used for the object of a verb, we know that whom is the correct choice here. Confirm this by replacing whom with her or him. If the sentence is still grammatically correct, then whom is the right pronoun to use. If not, then you should use who.

6. Who or Whom Did You See?

Even though you often hear who did you see in everyday conversations, the most grammatically correct answer is whom did you see. Whom refers to the object of the preposition or verb in a sentence. This sentence doesn’t have a preposition, but it does have a verb: see. What’s more, this verb refers to the person you saw (the object), and not you (the subject).

Usually, who refers to the subject. Since whom refers to the object of a verb, it’s the correct pronoun to use in this sentence. One way to confirm this is to rewrite the sentence using him or her. If the sentence is still correct, then you confirm that whom is the correct pronoun.

7. Who or Whom I’ve Never met?

The correct phrasing here is whom I’ve never met. The reason is that whom typically refers to the object of a sentence’s preposition or verb. In other words, whom receives the action.

On the other hand, who usually refers to the subject. This phrase doesn’t feature a preposition, but it does have the verbs have and met. Have is a linking verb, so it’s not showing any action.

However, met is an action verb and is acting on whom. As a result, whom receives the action. The verb met refers to the object (whom) and not the subject (I). Therefore, we know that whom is the correct pronoun. Verify this by rewriting the sentence to substitute whom with she or he.

8. Who We Miss or Whom We Miss?

Whom we miss is correct, not who we miss. Who refers to the subject whilewhom refers to the object of the preposition or verb. We is the subject.

However, the verb miss doesn’t refer to the subject we. Instead, it refers to the person you miss. This means that the person you miss is an object of the verb miss. For this reason, whom is the correct pronoun to refer to the person you miss.

Test this by rewriting the sentences to replace whom with the pronouns him, her, or they. Is the sentence still grammatically correct? If it is, then the correct answer is whom. If it’s not, then you should use who instead.

9. Who or Whom I Love so Much?

The correct way to phrase this whom I love so much,not who I love so much. We know that whom is correct because this pronoun refers to the object of a preposition or verb. We may not have a preposition, but we have the verb love. This verb refers to the person being loved (object), and not the I, or the person doing the loving (subject).

Since who refers to the subject while whom refers to the object of the verb, whom is correct. Check that whom is the correct pronoun by rewriting the sentence with him,her, or them. If the sentence is still grammatically correct with one of these other pronouns, then you know whom is correct. However, if he, she, or they fit better, then you know who is correct.

10. Who or Whom Wants Ice Cream?

Who wants ice cream is the correct way to phrase this sentence. The best way to confirm that who is the correct pronoun is to replace it with he/she/they. Does the sentence still make sense? Is it still grammatically correct? If yes, then you know who is correct. If no, then you should use whom.

What’s more, use who to refer to the subject of the sentence. Another way we know that who wants ice cream is correct option is because the subject of the sentence is who.

11. Is it “Who to Ask” or “Whom to Ask”?

The grammatically correct way to phrase this is whom to ask. The phrase to ask really means should I ask. Whenever we need a pronoun that refers to the subject, we use who.

However, when we need one that refers to the object of a preposition or a verb, we use whom. Here, the implied verb shouldrefers to implied subject I. So, now we need a pronoun to go with the verb ask.

Sincewhom refers to the object of the verb and not the subject, we know that whom is the correct pronoun. An easy way to confirm this is to rephrase the sentence using him/her/them. These work as substitutes for whom while he/she/they work for who.

12. Who to Follow or Whom to Follow?

Although the majority of people would probably say who, whom to follow is correct. This is because the phrase to follow actually means should I follow. Therefore, the implied verb should refers to implied subject I.

Since we use who to refer to the subject, we can rule out who. Instead, we use whom to refer to the object of the preposition or verb. Specifically, we need an object for the verb follow. This is why whom is the correct answer.

Easily verify this is by rephrasing the sentence using him/her/them. You can use these pronouns as substitutes for whom and the existence will remain correct. Similarly use he/she/they for who.

13. Who Should you Invite to the Party?

Even though most people would use who, the grammatically correct way to phrase this sentence is Whom should you invite to the party. The trick to know with certainty that the answer is whom is to rephrase the sentence using him/her/them. This is because we use whom to refer to the object of a preposition or verb, and these pronouns can substitute whom.

Conversely, we use who to refer to the subject of the sentence, and he/she/they can substitute who. In this example, the verb shouldrefers to the subject you. However, we need an object for the verb invite. Therefore, whom is the best fit.

Whom: Death of a Pronoun

Many modern grammarians consider whomto be a dying word.

It wouldn’t be the first pronoun to fall out of use, either. Others that have gone before it include thy, thine, ye, and thee. Although they may still show up in religious writing, they’ve fallen out of common use.

Although whom and whomever still have a place in formal writing, they are no longer common in spoken English. Many publications have also ceased using them. Instead, they opt to rephrase sentences to include easier-to-digest pronouns such as him, her, and them.

Who vs. Whom Recap

Who and whom are both pronouns. Depending on your sentence structure, you can easily determine which one to choose.

Ask yourself the following:

- Are you referring to the subject of the sentence? If so, use the pronoun who.

- Is the object of the sentence what you’re referring to? If so, use the pronoun whom.

Here’s a trick that you can use if you get stuck. When deciding on whom vs. who, think of it as him vs he.

- If you can answer the question with “he,” you’ll want to use who—no “m” at the end!

- However, if you can answer the query with “him,” you’ll want to use whom. They both have an “m” at the end!

But wait! What if you’re talking about a lady instead of a gentleman? No worries—we only used “he” or “him” because it makes it easier to highlight the “m” connection. While “whom“or“him” is a quick and memorable mnemonic device, the same idea applies to “she” or “her.”

- If you can answer the question with “she,” you’ll want to use who.

- On the other hand, if the answer to the question is “her,” you’ll want to use whom.

Ready to Dominate This Who vs. Whom Quiz?

Whom Question #1

A. Noun

B. Pronoun

C. Verb

D. Adverb

Correct!

Wrong!

The answer is B. “Whom” is an interrogative pronoun.

Who Question #2

A. The object of the sentence

B. The subject of the sentence

C. The object of the preposition

D. All of the above

Correct!

Wrong!

The answer is B. Use “who” when referring to the subject of a sentence.

Who vs. Whom Question #3

Please select 2 correct answers

A. The object of the verb

B. The subject of the sentence

C. The object of the preposition

D. All of the above

Correct!

Wrong!

The answers are A and C. Use “whom” when referring to the object of a verb or preposition.

Who or Whom Question #4

Correct!

Wrong!

The answer is C. While it’s easy to remember “him” because “m” is present, “her” will also do the trick.

Whom vs Who Question #5

Correct!

Wrong!

The answer is WHOM. Here, “whom” refers to the object of the verb.

Who and Whom Question #6

Correct!

Wrong!

The answer is WHO. “Who” refers to the subject of the sentence.

Read More: ??♀️ Whoever vs. Whomever: The Easiest Guide on When to use Which Pronoun

-

#1

hi, i have already come across this kind of questions a few times, but in fact i don’t know which one is formally correct. so here are the questions:

Who are these books for?

For whom are these books?I think that they are both correct but are there any shades in meaning or use?thanks

-

#2

I think it depends on what you mean by ‘correct’.

«For whom are these books?» is grammatically correct. «Whom» is the object of the verb. However, its use in everyday speech would sound archaic and pedantic.

«Who are these books for?» is not strictly ‘correct’ English, but I suspect that the vast majority of native (UK) English speakers would use this version of the question in normal conversation.

-

#3

I think it depends on what you mean by ‘correct’.

«For whom are these books?» is grammatically correct. «Whom» is the object of the verb. However, its use in everyday speech would sound archaic and pedantic.

«Who are these books for?» is not strictly ‘correct’ English, but I suspect that the vast majority of native (UK) English speakers would use this version of the question in normal conversation.

and can this be generalized for all the «wh-» questions? what about these examples:

From where does this originate?

With what would you like to start?

By what tool did you do that?Are they acceptable or should I put the prepositions at the end?

-

#4

I’m not a native, but a construction like:

Where are you from?

What are you looking for?

sounds more pleasant to me.

-

#5

(a) From where does this originate? — «Where does this originate from?»

(b) With what would you like to start? — «What would you like to start with?»

(c) By what tool did you do that? — «What tool did you do that with?»

There is a general rule in English: that you should never end a sentence with a preposition. The alternative versions that I have supplied are therefore ‘wrong’ in every case; however, this is a rule that is rarely obeyed in normal everyday speech. If you want to speak English like a native, use the versions that I have written.

Last edited: Feb 28, 2012

-

#6

DocPenfro, but using prepositions in the beginning of a sentence is «grammatically correct», isn’t it?

I mean, it’s not common in the colloquial speech, but it can take place in, for example, classic literature?

-

#7

I see Doc’s view grammaticaly ‘sound’.

-

#8

(a) From where does this originate? — «Where does this originate from?»

(b) With what would you like to start? — «What would you like to start with?»

(c) By what tool did you do that? — «What tool did you do that with?»There is a general rule in English: that you should never end a sentence with a preposition. The alternative versions that I have supplied are therefore ‘wrong’ in every case; however, this is a rule that is rarely obeyed in normal everyday speech. If you want to speak English like a native, use the versions that I have written.

this is how i teach it in my classes, claiming that your versions are «gramatically correct», mentioning that mine may occur in formal language, but that preposition-ending questions are more standard in general… funny how contradictory it is. Sometimes i find something in English what completely breaks all the standard rules (which i keep when i teach). then i feel like a fool…

-

#9

Vektus and Ibo81:

What does ‘correct’ usage really mean? I would understand it to mean ‘according to the conventional usage of educated native speakers’. What are ‘rules’? They are descriptive, i.e. they describe the way in which native speakers use English. I might turn to those rules for advice, but they are not prescriptive like motoring laws. The language changes over time, and a construction that was thought of as ‘ungrammatical’ a generation ago may be regarded as standard and acceptable today. Even the educated native speakers would take liberties in everyday speech, although they might try to use more formal language in a written essay. To answer Vektus’ question: I was taught the rule, that you should not end a sentence with a preposition, nearly fifty years ago. The Oxford Dictionary online now says that it is ‘perfectly acceptable’ to do so. I can only recommend that you read as much as possible of recently-written English, and listen to sources such as the BBC, which generally maintains high standards. You should also bear in mind that any non-native teacher of English may still be clinging to a set of rules that he or she learned a long time ago. It is difficult to accept change, particularly as you get older, and to realise that your ‘knowledge’ is no longer valid. Unfortunately it is something that we have to put up with.

Last edited: Feb 28, 2012

-

#10

In my view, while putting the preposition at the beginning of the sentence is still correct, putting it at the end can no longer be considered incorrect. I don’t have the sources but I believe it has been used for centuries and not just for a generation or two. It is used at the beginning more in relative clauses than in questions and, in a formal text, this is more for the purposes of clarity than for «correctness».

Of course, a descriptive rule becomes prescriptive when a non-native asks: «What should I say/write if I want to sound natural to a native speaker?»

-

#11

In the 19th century there was a theory that prepositions should never be used to end a sentence

with

(!).

This was based on Latin, and never had any real foundation in English. It has been ignored by the best writers for centuries, and it’s time it was relegated to the dustbin of history. It often sounds pretentious; don’t teach it as a rule, don’t use it unless it really helps the sense.

Or, as Churchill is said to have responded: «This is a habit up with which I will not put».

-

#12

It is not incorrect in English to end a sentence with a preposition. The idea that there exists or existed such a rule is a myth, a superstition. We should all stop repeating it.

From Oxford Dictionaries online:

Were you taught that a preposition should never be placed at the end of a sentence? There are times when it would be pretty much impossible to organize a sentence in a way that would avoid doing this, for example:

…

There’s no necessity to ban prepositions from the end of sentences. Ending a sentence with a preposition is a perfectly natural part of the structure of modern English.

From Garner’s Modern American Usage

«The spurious rule about not ending sentences with prepositions is a remnant of Latin grammar, in which a preposition was the one word that a writer could not end a sentence with. But Latin grammar should never straightjacket English grammar. If the superstition is a «rule» at all, it is a rule of rhetoric and not of grammar, the idea being to end sentences with strong words that drive a point home.

From the Washington Square Press Handbook of Good English:

Note that it is permissible to end a sentence with a preposition, despite a durable superstition that it is an error. He told me where to stand at is an error, but not because the preposition at is at the end; at shouldn’t be in the sentence at all.

Find several more examples of reliable sources exploding this myth (with publication dates ranging from 1902 through 2004) here:

http://grammar.about.com/od/grammarfaq/f/terminalprepositionmyth.htm

Last edited: Feb 28, 2012

-

#13

DocPenfro, thank you.

I’ve met mostly sentences with prepositions in the end, and I would definitely say this way, but I was interested in this:

«For whom are these books?» is grammatically correct. However, its use in everyday speech would sound archaic and pedantic.

So, knowing that such constructions were normal some time ago (but not now!), one won’t be confused when meeting it in some classic book, for example. Reading is very useful and helpful (especially if you have a lack of practice), but in some cases the expressions can be old-fashioned, like in classic literature. That’s why I’ve asked.

Thank you very much indeed.

Of course, a descriptive rule becomes prescriptive when a non-native asks: «What should I say/write if I want to sound natural to a native speaker?»

Exactly! Nice remark.

-

#14

[…] So, knowing that such constructions were normal some time ago (but not now!), one won’t be confused when meeting it in some classic book, for example. […]

As DocPenfro says, language changes over time, but of course it’s continuous — not just ‘now vs before’. There’s now, and before that, and before that again, etc … Linguistically conservative people (none in this thread!) tend to argue in favour of the form that’s just going (or just gone) out of fashion, overlooking the fact that that form itself was once controversially new, and replaced something else. Take the example:

(a) From where does this originate? — «Where does this originate from?».

No doubt at some time in the past there was a debate about whether «From where …?» should be allowed to replace «Whence does this originate?», which in turn may have been daringly modern relative to the marvellously neat «Whence cometh this?» (Answer: «Hither and thither» ).

My point is that ‘normal’ or ‘not’ isn’t black and white. «Where …from» is current. «From where …» is current but rarer. «Whence …» is extremely rare. «Whence cometh» is totally obsolete.

Ws

-

#15

As various posters have said, both forms are accepted these days.

For whom is this gift? <—> Who is this gift for?

With whom did you go? <—> Who did you go with?

etc.

However, if you mix the two forms, it sounds quite bad —

Whom is this gift for?

Whom did you go with?

-

#16

Use of who and whom. When object is he, use who and him then use whom.

I went to London with John/him. So question is whom did you go to London with?

If someone killed someone we should say, whom did you kill? But in movies I heard who.

Like we are four friend and brother wants to meet one what should I say, Whom do you want to see? I prefer whom.

Cagey

post mod (English Only / Latin)

-

#17

If you read the previous posts, you will see that most people agree that «With whom did you go?» and «Whom did you kill?» are grammatically correct, but that in ordinary speech people would say who: Who did you go with? Who did you kill?

To most people the forms with ‘whom’ sound too formal and stiff for ordinary speech and [

walking

] <talking>.

< Edit: My brain was on a stroll. >.

Last edited: Jan 26, 2015

-

#18

Not a good idea to be too stiff if you’re going walking, Cagey.

Ws

Let me quote Kennan here as his words still matter today:»Our first step must be to apprehend,

and recognize for what it is, the nature of the movement with which we are dealing.

Позвольте мне процитировать здесь Кеннана, потому что его слова до сих пор актуальны:« На первом этапе мы должны понять природу движения,

с которым мы имеем дело.

In view of the upcoming twentieth anniversary of the opening

for signature of the Convention on the Law of the Sea in 2002, I believe that his words still carry a message for all delegations as we strive to fulfil

our responsibilities as temporary curators of the oceans and the seas.

В преддверии предстоящей в 2002 году двадцатой годовщины

открытия для подписания Конвенции по морскому праву его слова, как я полагаю, попрежнему являются откровением для всех делегаций в то время,

когда мы пытаемся выполнить наши обязанности в качестве временных хранителей Мирового океана.

Mary Margaret, moved by

his

words, still cannot bring herself to take him back and leaves.

Мэри Маргарет, тронутая его словами, до сих пор не может заставить себя вернуть его обратно и садится в машину,

а он уходит.

President Kennedy’s vision exceeded the possibilities of

his

time, but his words speak to us still.

Предвидение президента Кеннеди превзошло возможности того времени, однако его слова по-прежнему актуальны для нас.

His words ring true for all who still suffer from human rights violations.

Его слова находят отклик в душах всех, кто все еще страдает от нарушений прав человека.

This is the story where the windstorm comes, the disciples panic,

and Jesus calms the wind with His words,“Peace, be still.”.

Это история, где метель приходит, ученики паники,

His words are

still

famous:“Earthly realm is short lived,

and the heavenly one forever”.

Знамениты его слова:« Земное это небольшое царство,

а Небесное это навсегда и во веки веков».

I’m talking about mercy,» said Woland, explaining his words, his fiery eye

still

fixed on Margarita.

Я о милосердии говорю,- объяснил свои слова Воланд, не спуская с Маргариты огненного глаза.

Results: 18686,

Time: 0.2091

English

—

Russian

Russian

—

English

The trouble with the word «word» is that it is very ambiguous. It used to mean «native word size» of a computer. Which was all over the place in the early years. Weird sizes too, multiples of 6 were popular, like 18 and 36 bits. Back then everybody understood that «word» didn’t say anything about the number of bits. The term «byte» didn’t get a meaning until much later.

That changed when micro-processors came around, first in 8 and 16-bit flavors. Where «word» got to be synonymous with «16-bits». That lasted a long time, until 32-bit processors became common. Processors like the 386 whose native word size is 32-bits but could still address 16-bit quantities as well. So to avoid breaking tons of assumptions, and keeping at least some of the existing assembly code compatible, they had to come up with a new word for the quantity of 32-bits. That became «dword», double word or 2 x 16-bits. And «word» stayed 16-bits, even though it now has nothing to do anymore with the native word size.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

слово все равно

слово по-прежнему

слово все еще

слово до сих пор

Предложения

The owner of the name can sometimes listen to his advice, but the last word still remains for her.

Обладательница имени может иногда прислушаться к его советам, но последнее слово все равно остается за ней.

But even if, in your opinion, the situation is deadlocked, the last word still leave behind a son or a daughter.

Но даже если, на ваш взгляд, ситуация тупиковая, последнее слово все равно оставьте за сыном или дочерью.

Even in today’s age of electronic mail, the written or printed word still travels around, through postal services.

Даже в сегодняшний век электронной почты, письменное или печатное слово по-прежнему путешествует по, посредством почтовой связи.

Does the word still mean anything in the flat wet world that is experiencing a real creativity mania, and where everybody wants to be and has to be creative?

Разве это слово по-прежнему имеет значение в плоском жидком мире, который переживает настоящую креативную манию, и где каждый хочет и должен быть креативным?

This word still exists in French as franc, it is also used as the translation of «Frank» and to name the local money, until the use of the euro in the 2000s.

Это слово все еще существует во французском языке как франк, оно также используется как перевод «франк», и в названии местных денег, до прихода евро в 2000-м году.

Of course, the decisive word still remains with your doctor, it is he who is able to prescribe Vishnevsky ointment or advise another drug.

Конечно, решающее слово всё равно остаётся за вашим лечащим врачом, именно он способен назначить вам мазь Вишневского или посоветовать другой препарат.

That simple word still hit like a hammer.

The opinion of the second half always takes into account in this case, but the last word still remains with him.

Всегда прислушиваются к мнению второй половинки, но при этом оставляют последнее слово за собой.

Every word still known by heart.

Thousand times to write that word still will not be enough to Express their meanness.

Тысячу раз написать это слово, все равно будет мало для выражения их подлости.

The oldest Old English word still used today that has the same direct meaning is ‘town’.

Самое старое древнеанглийское слово, которое до сих пор можно услышать среди носителей языка, имеет такое же прямое значение, что и слово «town» (город).

People who made the pledge might be dead but their word still lives on, Aslam.

Люди, которые дали клятву, могут быть мертвы, но их клятва до сих пор живет, Аслам джи.

Japanese emigrants across the word still often speak Japanese as their first language and still use Japanese in their everyday lives.

Японские эмигранты по всему миру довольно часто пользуются японским как своим первым языком и говорят по-японски в повседневной жизни.

However, it is believed that the last word still belongs to the Parliament.

Однако считается, что последнее слово все же принадлежит парламен-ту.

My word still good enough for you?

Мои слова ещё что-то значат для тебя?

Whose living word still stimulates the air?

Кому принадлежат слова Пока дышу, надеюсь?

The printed word still retains its magic.

По представлениям знахарей слово сохраняет свою магическую силу

And though for many viewers in our country that word still sounds foreign, he has nowhere to go.

И хоть для многих зрителей в нашей стране это слово до сих пор звучит чужеродно, от него уже никуда не деться.

This is what the word still suggests in socialist countries and in underdeveloped capitalist countries.

Подобный смысл это слово сохраняет и в социалистических странах, и в отсталых капиталистических странах.

That symbol was called ‘shunya’, a word still used today to mean both nothing as a concept, and zero as a number.

Новый символ назвали «шунья», а этим словом до сих пор пользуются для выражения такого понятия как «ничто», а также и нуля в качестве числа.

Предложения, которые содержат word still

Результатов: 45. Точных совпадений: 45. Затраченное время: 92 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Пословицы и поговорки – это отражение народной мысли, установок, моральных ценностей. Обычно они имеют аналоги в других языках, поскольку воспроизводят “простые истины”, свойственные любому человеку каждой нации. Пословица может иметь другие образы, но будет доносить тот же смысл:

| Английские пословицы | Русские эквиваленты английских пословиц |

| When in Rome, do as the Romans do. | В чужой монастырь со своим уставом не ходят. |

| The early bird catches the worm. | Кто рано встаёт – тому Бог подает. |

| Too many cooks spoil the broth. | У семи нянек дитя без глазу. |

⠀

Но есть высказывания, которые вообще не имеют эквивалента в русском языке. Такие пословицы в наибольшей степени отражают отличия менталитета, поэтому составляют для нас особый интерес.

Кстати, сегодня мы узнаем не только смысл этих английских пословиц, но и связанные с ними занимательные истории.

Обрати внимание: если вдруг ты не согласен с описанным примером и точно знаешь русский аналог, то обязательно пиши об этом в комментариях – подискутируем! 🙂

Уникальное наследие: пословицы на английском языке с переводом

1. If you can’t be good, be careful.

Дословный перевод: Если не можешь быть хорошим, будь осторожен.

Если ты собираешься делать безнравственные вещи, убедись, что они не опасны для тебя или общества. Когда ты планируешь сделать что-то аморальное, удостоверься, что об этом никто не узнает.

Первое упоминание именно этой формулировки датируется 1903-м годом, но смысл выражения намного старше и берет свое начало из латинской пословицы “Si non caste, tamen caute” (если не целомудренно, то по крайней мере осторожно).

2. A volunteer is worth twenty pressed men.

Дословный перевод: Один доброволец стоит двадцати принужденных.

Значение пословицы по сути прямое: даже маленькая группа людей может быть полезнее, если у нее есть энтузиазм, стремление и т.д. Зародилась эта пословица в начале 18-го века.

В то время Королевский флот имел группу матросов, вооруженных дубинками, чья цель была “насобирать” моряков на флот. Они могли делать это, рассказывая о небывалых преимуществах службы, или же просто силой (все же вооружены дубинками они были неспроста).

Такое стечение обстоятельств не делало принужденного хорошим моряком. Отсюда и “вытекло” это умозаключение.

Заметь, что в этой пословице можно менять соотношение цифр:

100 volunteers are worth 200 press’d men.

One volunteer is worth two pressed men

и т.д.

3. Suffering for a friend doubleth friendship.

Дословный перевод: Страдание за друга удваивает дружбу.

Значение этой шотландской пословицы понятно без особых объяснений. Казалось бы, в русском языке есть довольно похожая пословица “друг познается в беде”. При этом очень интересен сам смысл “страдания за друга”. Если в русском варианте говорится о том, чтобы не отвернуться от друга и помочь ему в трудной ситуации, то здесь именно страдать вместе с ним, тем самым усиливая дружбу.

Еще одна интересная с точки зрения образов английская пословица о дружбе: Friends are made in wine and proven in tears (дружба рождается в вине, а проверяется в слезах).

Также читайте: Какой он — живой английский язык?

4. A woman’s work is never done.

Дословный перевод: Женский труд никогда не заканчивается.

Ну вот и о нашей нелегкой женской доле английские пословицы позаботились 🙂 Выражение пошло от старинного двустишия:

Man may work from sun to sun,

But woman’s work is never done.

Получается, значение пословицы в том, что женские дела (в отличие от мужских) длятся бесконечно. Видно это из примера:

“A woman’s work is never done!”, said Leila. She added: “As soon as I finish washing the breakfast dishes, it’s time to start preparing lunch. Then I have to go shopping and when the kids are back home I have to help them with their homework.”

(“Женский труд никогда не заканчивается!”, – Сказала Лейла. Она добавила: “Как только я заканчиваю мыть посуду после завтрака, приходит время готовить обед. Потом я должна идти по магазинам и, когда дети возвращаются домой, я должна помогать им с домашним заданием”.)

5. Comparisons are odious / odorous.

Дословный перевод: Сравнения отвратительны / воняют.

Люди должны оцениваться по их собственным заслугам, не стоит кого-либо или что-либо сравнивать между собой.

Два варианта пословица имеет не просто так. Первый вариант (Comparisons are odious) очень древний, и впервые он был запечатлен еще в 1440 году. А вот измененный вариант (Comparisons are odorous) был “создан” Шекспиром и использован им в пьесе “Много шума из ничего”.

6. Money talks.

Дословный перевод: Деньги говорят (сами за себя).

Значение – деньги решают все. Происхождение выражения является предметом споров среди лингвистов. Одни считают, что пословица зародилась в Америке 19-го века, другие – что в средневековой Англии.

Кстати, пословица использована в названии песни австралийской рок-группы AC/DC.

7. Don’t keep a dog and bark yourself.

Дословный перевод: Не держи собаку, если лаешь сам.

Значение этой английском пословицы: не работай за своего подчиненного. Высказывание очень древнее: первое упоминание зафиксировано еще в 1583 году.

По поводу отсутствия аналога: в разных источниках дана разная информация. Кто-то согласен с тем, что аналогов в русском языке нет, другие в качестве эквивалента предлагают пословицу:

За то собаку кормят, что она лает.

Однако, в Большом словаре русских пословиц такой пословицы о собаке нет вообще. Возможно, то что предлагают нам в качестве альтернативы, это адаптированный перевод именно английской пословицы (такое бывает).

8. Every man has his price.

Дословный перевод: У каждого есть своя цена.

Согласно этой пословице, подкупить можно любого, главное предложить достаточную цену. Наблюдение впервые зафиксировано в 1734 году, но, скорее всего, имеет и более давнюю историю.

Также читайте: История Англии: список лучших документальных фильмов

9. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

Дословный перевод: Подражание – самая искренняя форма лести.

Значение пословицы прямое. Эта формулировка восходит к началу 19-го века. Но сама мысль еще древнее и встречалась в текстах 18-го века, например, в 1714 году у журналиста Юстаса Баджелла:

Imitation is a kind of artless Flattery (Имитация является своего рода бесхитростной лестью).

10. It’s better to light a candle than curse the darkness.

Дословный перевод: Лучше зажечь свечу, чем проклинать темноту.

Вопрос об аналоге снова спорен: в некоторых источниках, где даны английские пословицы с переводом на русский, эквивалентом называют:

Лучше пойти и плюнуть, чем плюнуть и не пойти.

Хочу с этим поспорить. Значение русской пословицы: лучше сделать, чем жалеть, что не сделал. Смысл английской – лучше исправить положение, чем жаловаться на него. Лично мне смысловая составляющая про жалобы кажется первостепенной, поэтому приравнивать эти пословицы я бы не стала.

11. Stupid is as stupid does

Дословный перевод: Глуп тот, кто глупо поступает.

На самом деле это не совсем “народная пословица”, а фраза, которой Форест Гамп отбивался от назойливых вопросов о своем интеллекте:

Фраза ушла в народ 🙂 Прародитель этого выражения – пословица “Handsome is as handsome does” (красив тот, кто красиво поступает), уже имеющая аналог в русском языке: “Не тот хорош, кто лицом пригож, а тот хорош, кто для дела гож”.

Также читайте: Игра престолов с Lingualeo, или Hear me roar

12. You can’t make bricks without straw

Дословный перевод: Нельзя сделать кирпич без соломы.

Опять же в некоторых источниках в качестве аналога указывается русское “без труда не вытащишь и рыбку из пруда”. При этом английская пословица говорит не о трудолюбии, а о невозможности выполнить задачу без необходимых материалов.

“It’s no good trying to build a website if you don’t know any html, you can’t make bricks without straw.” (Не пытайся создать веб-сайт, если ты не знаешь HTML: ты не можешь делать кирпичи без соломы).

Согласно википедии выражение берет начало из библейского сюжета, когда Фараон в наказание запрещает давать израильтянам солому, но приказывает делать то же количество кирпичей, как и раньше.

Где искать пословицы и поговорки на английском языке по темам?

Возможно, это не все высказывания, не имеющие русских аналогов, ведь английских пословиц (и их значений) огромное множество. Кстати, ты вполне можешь поискать их самостоятельно в нашей Библиотеке материалов по запросу “proverb”, чтобы насытить свою английскую речь чудесными выражениями. Успехов! 🙂

Подтянуть английский язык помогает чтение в оригинале: так можно и словарный запас пополнить, и грамматику отработать. Однако часто возникает ситуация, когда все слова вроде и знакомы, но они как будто случайно оказались вместе. Вместе с руководителем онлайн-школы английского языка Wordika Вероникой Генераловой мы нашли самые необычные английские идиомы и разобрались, что они означают.

To be under the weather — Неважно себя чувствовать

Буквальный перевод: «быть под погодой».

Есть несколько версий происхождения выражения, но все они связаны с морем. В основе первой — особенности ведения бортового журнала: в нем капитан судна ежедневно отмечал погодные условия и состав команды корабля. Тех, кто не мог нести службу, записывали в специальную колонку. Во время шторма туда попадали и многочисленные страдальцы, сломленные морской болезнью. В ненастные дни эта секция часто переполнялась, поэтому моряков приходилось записывать в соседнюю колонку, в графу «Погода» (weather), то есть «under the weather».

Вторая версия связана с местом размещения больных моряков: во время качки всех, кому становилось плохо, отправляли «under the deck and away from the weather», то есть «под палубу, подальше от непогоды». Со временем из этой фразы выпали «палуба» и «подальше» — так появился современный вариант идиомы.

How did you know I was feeling so under the weather this evening? / Как ты узнал, что мне так нехорошо этим вечером?

Pot calling the kettle black — Кто бы говорил

Буквальный перевод: «горшок зовет котел черным (а сам не белее)».

Много лет назад люди готовили на открытом огне в чугунных горшках и медных котлах, после чего на них оставалась черная сажа. Медные котлы очищали и полировали после каждой готовки до блеска настолько, что стоящий рядом горшок отражался в нем, как в зеркале. Так и появилась идея о том, что горшок обвиняет чистый котел в нечистоплотности, хотя на самом деле именно он весь в саже.

Both game developers accuse each other for ripping their narratives: it’s like the pot calling the kettle black. / Оба разработчика игр обвиняют друг друга в плагиате сюжета, хотя чья бы корова мычала.

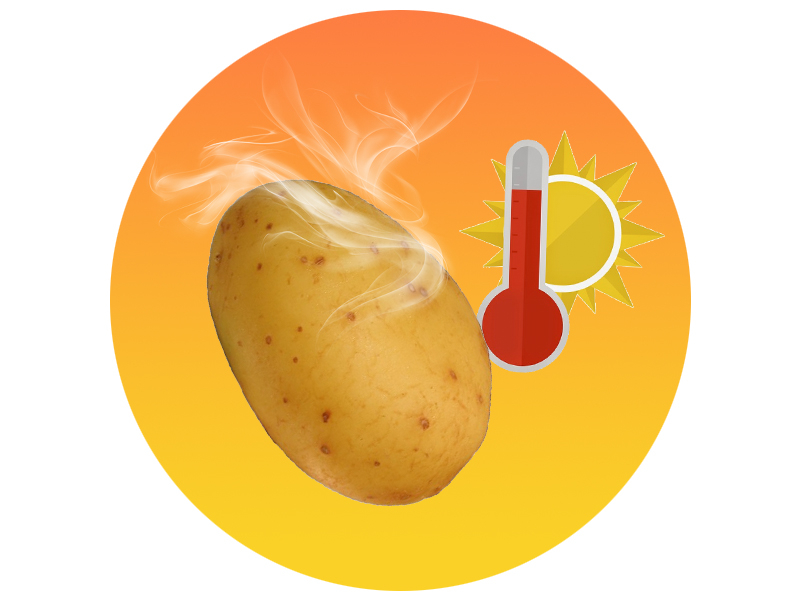

A hot potato — Щекотливый вопрос

Буквальный перевод: «горячая картошка».

Это выражение известно с середины XIX века и связано с другим фразеологизмом — «to drop like a hot potato» (стремительно от чего-либо избавиться). Ассоциация возникла на фоне того, как быстро из рук выскальзывает горячая картошка. Так словосочетание «hot potato» стало самостоятельно обозначать что-то не самое приятное, с чем хочется поскорее расправиться.

How will this crisis affect cinema production is a hot potato. / Как кризис повлияет на производство кино — щекотливый вопрос.

Cat got your tongue? — Язык проглотил?

Буквальный перевод: «кошка схватила тебя за язык?».

Изначально выражение звучало так: «Has the cat got your tongue?», позже его сократили до «Сat got your tongue». Точное происхождение выражения неизвестно, но есть несколько предположений.

Так, согласно первой версии, выражение пошло от плетки для наказания заключенных, которая по-английски называется «cat o’ nine tails» (буквально это можно перевести как «девятихвостая кошка»). Страх наказания этой плетью заставлял британских преступников держать язык за зубами.

Вторая версия отсылает к средневековой боязни ведьм и их верных спутников — черных котов. Поэтому, когда человек терял дар речи от удивления или шока, такую ситуацию сравнивали с проклятием, которое наложила чародейка явно не без помощи своего кота.

You could be more enthusiastic about the launch! Cat got your tongue? / Мог бы и порадоваться запуску проекта! Ты что, язык проглотил?

Neck of the woods — Трущобы, глушь

Буквальный перевод: «лесная шея».

Эта фраза характерна для американского английского. Впервые она появилась во времена колонистов, но варианты происхождения разнятся. По одной из версий, жители Нового Света старались максимально отстраниться от английских корней и использовали другие слова для обозначения привычных вещей: изначально «шеей» (а вернее, перешейком) называли узкий участок земли, окруженный с двух сторон водой. Американцы начали называть шеей еще и неширокую часть леса или пастбища, а позже и поселение, расположенное в такой местности.

Вторая версия связана с языком коренных американцев алгонкинов: их слово «naiack» означало «место» или «угол». Поселенцы могли перенять это выражение, но со временем его написание и произношение сблизилось с привычным англоязычным жителям Нового Света «neck».

Welcome to my neck of the woods. / Добро пожаловать в мою трущобу.

To go pear-shaped — Пойти наперекосяк

Буквальный перевод: «приобрести форму груши».

Одни лингвисты считают, что это выражение придумали пилоты Королевских военно-воздушных сил Великобритании в 1940-х годах: круги в воздухе — достаточно сложная фигура, поэтому часто вместо окружности у пилотов получалась груша. Другие полагают, что фразеологизм отсылает к Первой мировой войне: запуск воздушных шаров, использовавшихся в то время для наблюдения, шел наперекосяк, когда, надуваясь, они приобретали форму груши.

And when the main cast left, everything with the show went pear-shaped. / А когда основной актерский состав ушел, все в сериале пошло наперекосяк.

Blue in the face — До изнеможения

Буквальный перевод: «синее лицо».

Это выражение часто используется в описании разговоров и дискуссий. Фраза отсылает к ситуации, когда у непрерывно вещающего человека просто заканчивался воздух в легких и его лицо приобретало характерный синий оттенок.

She can talk about the history of feminism till she is blue in the face. / Она может говорить об истории феминизма до посинения.

Thick as thieves — Закадычные друзья

Буквальный перевод: «толстые, как воры».

Идиома появилась в начале XIX века и действительно имеет криминальное прошлое. В то время воры работали в бандах, и успех их планов зависел от уровня доверия внутри группировки, поэтому преступники знали друг о друге абсолютно все. Слово «thick» («толстый»), в данном случае означало «очень близкий», «тесно связанный». Изначально говорили «thick as two thieves», но позже числительное выпало, и получилось сегодняшнее выражение, которое означает близких друзей.

Hopper definitely knows Joyce’s whereabouts but he wouldn’t tell us anything — they are as thick as thieves. / Хоппер точно знает, где находится Джойс, но ничего не скажет: они закадычные друзья.

Wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole — Не приблизился бы и на километр

Буквальный перевод: «не стал бы трогать и баржевой палкой».

В XIX веке, когда многие баржи еще не могли плыть самостоятельно, люди использовали для их передвижения специальные толстые и длинные (около 3 м) палки или сучья. Они позволяли безбоязненно исследовать незнакомый или не очень презентабельный предмет, попадавшийся на пути следования, поэтому выражение стали использовать для обозначения чего-то особенно неприятного или опасного.

They don’t want any bad publicity, so they wouldn’t touch this influencer with a barge pole. / Им не нужны проблемы с репутацией, так что они и на километр не подойдут к этому блогеру.

Heart in one’s mouth — Сердце в пятки ушло

Буквальный перевод: «сердце во рту».

Считается, что впервые это выражение использовал Гомер в «Илиаде», чтобы передать чувство невероятного нервного напряжения. Древнегреческий поэт обратил внимание на ощущение, которое возникает в моменты страха и волнения: сердце бьется так часто, что вибрация начинает чувствоваться в горле.

When they told me my flight has been postponed, I had my heart in mouth. / Когда мне сказали, что мой рейс отложен, у меня сердце в пятки ушло.

Go bananas — Слететь с катушек

Буквальный перевод: «стать бананом».

Группа Little Big тут ни при чем. Историки и лингвисты полагают, что постарались студенты американских колледжей и обезьяны. Изначально существовал фразеологизм «go ape», который тоже означал сумасшествие и отсылал к образу обезьяны. Устойчивая ассоциация животных с их любимым лакомством в глазах американских студентов стала причиной изменения фразы.

Everybody went bananas when all the fitness clubs in the city opened again. / Все просто с катушек слетели, когда снова открылись все фитнес-клубы города.

Cool as a cucumber — Спокоен как удав

Буквальный перевод: «холодный, как огурец».

Даже в жару огурец обычно на несколько градусов холоднее воздуха — так и появилось сравнение хладнокровного человека, спокойного при любой ситуации, с плодом травянистого растения семейства тыквенных.

The passengers worried about possible speeding ticket, yet Victor was as cool as a cucumber. / Пассажиры переживали из-за возможного штрафа за превышение скорости, а Виктор все равно был спокоен как удав.

Опишите свое состояние одним словом. Игра «РБК Стиль».