The company where I work we name internal software after characters/things from The Lord of the Rings universe. I will be creating a new project for the marketing department and I’m scratching my head thinking of a character/object/city that represents wealth/success.

As I was asking this question, Smaug came to mind because of his hoard of gold, but Smaug has a negative connotation to it (i.e. greed vs. success).

Is there an affluent city or person that you can think of that would be a good name for our new marketing software?

EDIT:

Everyone really likes your ideas guys but since we use Frodo as a main app, the marketing guy though that Bilbo might be a good choice. In case you’re wondering we have Palantir that runs on a giant wide screen for viewing order statuses and we’re thinking about using Sauron for another «all-seeing eye type dashboard».

Also, a couple ideas the company had were: Mordor, Wormtoungue, and Gimli. I guess marketing wasn’t opposed to having their application named after an evil character.

Thank you everyone for your contributions!

|

«Can you see anything?» «Nothing. There’s nothing.» The descriptive majority of this article’s text is unsourced, and should be supported with references. |

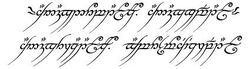

The Black Speech text inscribed on the One Ring

- Frodo: «It’s some form of Elvish. I can’t read it.»

Gandalf: «There are few who can. The language is that of Mordor, which I will not utter here.» - —Frodo Baggins and Gandalf the Grey, on the inscription on the One Ring, The Fellowship of the Ring (film)

The Black Speech, also known as the Dark Tongue of Mordor, was the official language of Mordor.

History

Sauron created the Black Speech to be the unifying language of all the servants of Mordor, used along with different varieties of Orkish and other languages used by his servants. J.R.R. Tolkien describes the language as existing in two forms, the ancient «pure» forms used by Sauron himself, the Nazgûl, and the Olog-hai, and the more «debased» form used by the soldiery of the Barad-dûr at the end of the Third Age. The only example given of «pure» Black Speech is the inscription upon the One Ring:

- «Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul,

- ash nazg thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul.«

- —The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Ch. II: «The Council of Elrond»

When translated into English, these words form the lines:

- «One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

- One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.«

- —J.R.R. Tolkien’s epigraph to The Lord of the Rings

These are the first two lines from the end of a verse about the Rings of Power.

Many Orkish dialects had adopted words from the Black Speech. One Orc from the band that took Merry and Pippin prisoners utters a tirade of curses at one point that is presumably Orkish, but apparently contains at least some elements of Black Speech.

Black Speech could be understood by anyone who wore the One Ring. Samwise Gamgee wore the ring in the Tower of Cirith Ungol to be invisible from Orcs of Sauron, and in the process heard many of the Orcs’ plans.

Background

In real life, J. R. R. Tolkien created this language with the intention of making it harsh and ugly. The Black Speech is unfortunately one of the more incomplete languages in Tolkien’s novels, as the forces of good are reluctant to utter it. Unlike Elvish languages, there are no poems or songs written in it (apart from the Ring’s inscription), and because Tolkien designed it to be unpleasant in his own mind, he did not enjoy writing in it; according to Tolkien, he once received a goblet from a fan with the Ring inscription on it in Black Speech, and Tolkien, finding it distasteful, never drank from it and used it only as an ashtray. The result is a random collection of words that are hard to actually use in day-to-day conversation. We learn from the text in the ring and its translation that the Black Speech is a strongly agglutinating language.

Russian historian Alexander Nemirovski identified an ergative case in durbatuluk and thrakatuluk according to a common suffix —tuluk meaning «them all», relating to the verb’s object rather than to its subject. This was found as a similarity to other ergative languages such the Hurrian language of ancient Mesopotamia.

Earlier versions of the legendarium

Melkian had been the linguistic phylum of the servants of Melko in an early conception of the legendarium, seen in The Lhammas. In this branch were the Black Speech, Orkish, and all other tongues of evil races. The other two phyla were Oromëan, from which descended both Elvish and Mannish languages, and Aulëan, the branch of Khuzdul.[1]

Words

Some of these words are true to J.R.R. Tolkien’s books; most others are part of the Neo-Black Speech lexicon invented in the making of Peter Jackson’s film trilogies.

- -a — to (Debased Black Speech)

- alba — elf

- agh -and (for conjoining sentences)

- ash — one

- burz — dark

- burzum — darkness

- durb — rule

- carnish — ambush

- gazat — dwarf

- ghâsh — fire

- gimb — find

- glob — filth

- gûl — wraith

- hai — folk

- -ishi — in

- krimp — bind

- lug — tower

- mas — mine

- nazg — ring

- nugu — nine

- olog — troll

- ombi — seven

- ronk — pit/pool (bagronk, as muttered by an Orc in The Two Towers, means «dung-pit»)

- sha -and (for binding nouns)

- shara — man

- sharkû — old/old man (Debased Black Speech)

- shre — three

- snaga- slave

- thrak — bring

- -tul -them

- ûk — all

- -um -ness

- uruk — orc

- zagh — mountain pass/mountains

See also

- Neo-Black Speech

References

- ↑ The History of Middle-earth, Vol. V: The Lost Road and Other Writings, chapter VII: «The Lhammas»

Translations

| Foreign Language | Translated name |

| Afrikaans | Swart Spraak |

| Albanian | Fjala e zezë |

| Amharic | ጥቁር ንግግር |

| Arabic | الكلام الأسود |

| Aragonese | Luenga negra |

| Armenian | Սեւ ելույթը |

| Azerbaijani | Qara çıxış |

| Basque | Hizkuntza beltza |

| Belarussian Cyrillic | Чорная мова |

| Bengali | ব্ল্যাক বাক |

| Bosnian | Crni Govor |

| Bulgarian Cyrillic | Черна реч |

| Burmese | အနက်ရောင်မိန့်ခွန်း |

| Cambodian | សុន្ទរកថាខ្មៅ |

| Catalan | Llengua Negra |

| Cebuano | Itom nga Sinultihan |

| Chinese | 黑暗語 |

| Cornish | Kows Du |

| Croatian | Crni Govor |

| Czech | Černá řeč |

| Danish | Sort Tale |

| Dutch | Zwarte Taal |

| Esperanto | Nigra lingvo |

| Estonian | Must kõne |

| Faroese | Svartur Mál |

| Fijian | Vosa Loaloa |

| Filipino | Itim na pananalita |

| Finnish | Musta kieli |

| French | Noir parler/Langue noire |

| Frisian | Swarte Rede |

| Galician | Lingua negra |

| Georgian | შავი ენა |

| German | Schwarze Sprache |

| Greek | Μαύρη Ομιλία |

| Gujarati | બ્લેક સ્પીચ |

| Haitian Creole | Nwa Lapawòl |

| Hausa | Baƙi Jawabin |

| Hebrew | שפה השחורה |

| Hindi | काले भाषण |

| Hmong | Hais lus dub |

| Hungarian | Fekete Beszéd |

| Icelandic | Svartur Tal |

| Indonesian | Bicara Hitam |

| Irish Gaelic | Teanga dhubh |

| Italian | Linguaggio Nero |

| Japanese | 暗黒語 |

| Javanese | Wicara Ireng |

| Kannada | ಕಪ್ಪು ಭಾಷೆ |

| Kazakh | Қара тіл (Cyrillic) Qara til (Latin) |

| Korean | 암흑어 |

| Kurdish | Axaftina Reş (Kurmanji) |

| Kyrgyz Cyrillic | кара сөз |

| Latvian | Melnā runa |

| Lithuanian | Juodoji kalba |

| Luxembourgish | Schwaarz Ried |

| Macedonian Cyrillic | Црна говор |

| Malagasy | Mainty Miteny |

| Malaysian | Ucapan Hitam |

| Malayalam | ബ്ലാക്ക് സ്പീച്ച് |

| Maltese | Diskors Iswed |

| Maori | Kōrero Pango |

| Marathi | काळा भाषण |

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Хар хэлсэн үг |

| Navajo | Shash Saad |

| Nepalese | काला भाषण |

| Norwegian | Svart Tale |

| Pashto | تور وینا |

| Persian | زبان سیاه |

| Polish | Czarna Mowa |

| Portuguese | Língua Negra |

| Punjabi | ਕਾਲੇ ਸਪੀਚ |

| Romanian | Limba Neagră |

| Romansh | Linguatg Naira |

| Russian | Чёрное наречие |

| Sanskrit | राजिका वाच् |

| Samoan | Tautala Uliuli |

| Scottish Gaelic | Dubh Òraid |

| Serbian | Црни Говор (Cyrillic) Crni Govor (Latin) |

| Sindhi | ڪارو تقرير |

| Sinhalese | කළු කථාව |

| Slovak | Temná reč |

| Slovenian | Črni govor |

| Somalian | Hadalka Madow |

| Spanish | Lengua Negra |

| Sundanese | Hideung Biantara |

| Swahili | Nyeusi Hotuba |

| Swedish | Svartspråket |

| Tahitian | Parau Ereere |

| Tajik Cyrillic | Суханронии сиёҳ |

| Tamil | கறுப்பு பேச்சு |

| Telugu | బ్లాక్ స్పీచ్ |

| Thai | แบล็กสปีช / ภาษามืด |

| Turkish | Kara Lisan |

| Turkmen | Gara dil |

| Ukrainian Cyrillic | Чорна говірка |

| Urdu | سیاہ خطاب |

| Uzbek | Қора Нутқ (Cyrillic) Qora Nutq (Latin) |

| Vietnamese | Chữ Đen |

| Welsh | Lleferydd Du |

| Xhosa | Intetho Abamnyama |

| Yiddish | שוואַרץ שפּראַך |

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is the 2001 epic fantasy adventure film and the first installment in The Lord of the Rings motion picture trilogy based on the volume novel by J. R. R. Tolkien. It tells the tale of nine companions starting out on a quest to destroy the One Ring and secure the fate of Middle Earth.

- Directed by Peter Jackson. Written by Frances Walsh, Philippa Boyens and Peter Jackson.

One Ring to rule them all. (taglines)

Gandalf the Grey[edit]

- [to Frodo] Keep it secret. Keep it safe.

- [reading] The year 3434 of the Second Age. Here follows the account of Isildur, the High King of Gondor, at the finding of the Ring of Power. «It has come to me, the One Ring. It shall be an heirloom of my Kingdom. All those who follow in my bloodline shall be bound to its fate, for I shall risk no hurt to the Ring. It is precious to me, though I buy it with a great pain. The markings upon the band begin to fade. The writing, which at first was as clear as red flame, has all but disappeared – a secret now that only fire can tell.»

- My dear Frodo. Hobbits really are amazing creatures. You can learn all that there is to know about their ways in a month and yet, after a hundred years, they can still surprise you.

- Be careful, both of you. The Enemy has many spies in his service; birds and beasts. [to Frodo] Is it safe? Never put it on, for then the agents of the Dark Lord will be drawn to its power. Always remember, Frodo, the Ring is trying to get back to its master. It wants to be found.

- [reading the inscription on a sarcophagus] «Here lies Balin, son of Fundin, Lord of Moria». He is dead then. It’s as I feared.

- [reading the Book of Mazarbul’s last entry] «They have taken the Bridge and the Second Hall. We have barred the gates, but cannot hold them for long. The ground shakes… Drums. Drums in the deep. We cannot get out. A Shadow moves in the dark… We cannot get out… They are coming.»

- Fool of a Took! Throw yourself in next time, and rid us of your stupidity!

- [confronting the Balrog on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm] You cannot pass! I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the Flame of Anor. The dark fire will not avail you, Flame of Udûn! Go back to the shadow. You shall not pass!

- Fly, you fools!

Galadriel[edit]

- [opening narration] The world is changed. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air. Much that once was is lost, for none now live who remember it. It began with the forging of the Great Rings. Three were given to the Elves; immortal, wisest and fairest of all beings. Seven to the Dwarf Lords, great miners and craftsmen of the mountain halls. And nine… Nine rings were gifted to the Race of Men, who above all else desire power. For within these rings was bound the strength and will to govern each race. But they were all of them deceived, for another ring was made. In the land of Mordor, in the fires of Mount Doom, the Dark Lord Sauron forged, in secret, a Master Ring to control all others. And into this Ring he poured all his cruelty, his malice and his will to dominate all life. One Ring to rule them all.

One by one, the Free Lands of Middle-Earth fell to the power of the Ring. But there were some who resisted. A last alliance of Men and Elves marched against the armies of Mordor. And on the slopes of Mount Doom, they fought for the freedom of Middle-Earth. Victory was near, but the power of the Ring could not be undone. It was in this moment, when all hope had faded, that Isildur, son of the king, took up his father’s sword. Sauron, the enemy of the free peoples of Middle-Earth, was defeated. The Ring passed to Isildur, who had this one chance to destroy evil forever, but the hearts of Men are easily corrupted. And the Ring of Power has a will of its own. It betrayed Isildur, to his death.

And some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend. Legend became myth. And for two and a half thousand years, the Ring passed out of all knowledge. Until, when chance came, it ensnared a new bearer. The Ring came to the creature Gollum, who took it deep into the tunnels of the Misty Mountains. And there it consumed him. The Ring brought to Gollum unnatural long life. For 500 years, it poisoned his mind. And in the gloom of Gollum’s cave, it waited. Darkness crept back into the forests of the world. Rumor grew of a shadow in the East – whispers of a nameless fear. And the Ring of Power perceived its time had now come. It abandoned Gollum. But something happened then the Ring did not intend. It was picked up by the most unlikely creature imaginable. A Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins of the Shire. For the time will soon come when Hobbits will shape the fortunes of all…

- Farewell, Frodo Baggins. I give you the Light of Eärendil, our most beloved star. May it be a light for you in dark places, when all other lights go out.

Bilbo Baggins[edit]

- [writing his book] The twenty-second day of September in the year 1400 by Shire reckoning. Bag End, Bagshot Row, Hobbiton, West Farthing, The Shire, Middle Earth. The Third Age of this world. «There and back again, A Hobbit’s tale, by Bilbo Baggins». Now, where to begin? Ah, yes. «Concerning Hobbits». Hobbits have been living and farming in the four Farthings of the Shire for many hundreds of years. Quite content to ignore and be ignored by the world of the Big Folk. Middle Earth being, after all, full of strange creatures beyond count. Hobbits must seem of little importance, being neither renowned as great warriors, nor counted amongst the very wise. …In fact, it has been remarked by some that Hobbits’ only real passion is for food. A rather unfair observation as we have also developed a keen interest in the brewing of ales and the smoking of pipeweed. But where our hearts truly lie is in peace and quiet and good tilled earth. For all Hobbits share a love of all things that grow. And yes, no doubt to others, our ways seem quaint. But today of all days, it is brought home to me it is no bad thing to celebrate a simple life.

- [writing in his book] And so life in the Shire goes on, very much as it has this past age. Full of its own comings and goings with change coming slowly, if it comes at all. For things are made to endure in the Shire, passing from one generation to the next. There’s always been a Baggins living here under the Hill, in Bag End. [to himself] And there always will be.

- [telling a story to the Hobbit children] So there I was at the mercy of three monstrous trolls. And they were all arguing amongst themselves about how they were going to cook us. Whether it be turned on a spit or whether they should sit on us one by one and squash us into jelly. They spent so much time arguing the witherto’s and whyfor’s that the sun’s first light cracked open over the top of the trees…Poof! And turned them all into stone!

- [to Frodo] I’m sorry I brought this upon you, my boy. I’m sorry that you must have to carry this burden. I’m sorry for everything.

Sauron[edit]

- [speaking to Frodo] You cannot hide. I see you! There is no life in the void…only death.

- [speaking to Saruman] Build me an army worthy of Mordor!

Dialogue[edit]

- Frodo: You’re late.

- Gandalf: A wizard is never late, Frodo Baggins. Nor is he early; he arrives precisely when he means to.

- Gandalf: So, how is the old rascal? I hear it is going to be a party of special significance.

- Frodo: You know Bilbo. He’s got the whole place in an uproar.

- Gandalf: Well, that should please him.

- Frodo: Half the Shire’s been invited. And the rest are turning up anyway.[They laugh]

- [Extended Edition only]

- Frodo: To tell you the truth, Bilbo’s been a bit odd lately. I mean… more than usual. He’s taking to locking himself in his study. He spends hours and hours poring over old maps when he thinks I’m not looking. He’s up to something. [Gandalf acts nonchalant] All right, then, keep your secrets. But I know you have something to do with it.

- Gandalf: Gracious me.

- Frodo: Before you came along, we Bagginses were very well thought of.

- Gandalf: Indeed?

- Frodo: Never had any adventures or did anything unexpected.

- Gandalf: If you’re referring to the incident with the dragon, I was barely involved. All I did was give your uncle a little nudge out of the door.

- Frodo: Whatever you did, you’ve been officially labeled a ‘disturber of the peace.’

- Gandalf: [surprised] Oh, really?

- [Gandalf arrives at Bag End, goes through the gate, and knocks on the door with his staff]

- Bilbo: [from inside] No, thank you! We don’t want any more visitors, well-wishers, or distant relations!

- Gandalf: And what about very old friends?

- [Bilbo opens the door]

- Bilbo: Gandalf?

- Gandalf: Bilbo Baggins.

- Bilbo: My dear Gandalf! [hugs Gandalf]

- Gandalf: It’s good to see you. One hundred and eleven years old; who would believe it? You haven’t aged a day. [they both laugh]

- Bilbo: Come on, come in! Welcome, welcome.

- Gandalf: Frodo suspects something.

- Bilbo: Of course he does! He’s a Baggins! Not some blockheaded Bracegirdle from Hardbottle.

- Gandalf: You will tell him, won’t you?

- Bilbo: Yes, yes.

- Gandalf: He’s very fond of you.

- Bilbo: I know, he’d probably come with me if I asked him to. I think in his heart, Frodo’s still in love with the Shire; the woods, the fields, little rivers… I am old, Gandalf. I know I don’t look it, but I’m beginning to feel it in my heart. I feel thin, sort of stretched, like butter scraped over too much bread. I need a holiday, a very long holiday. And I don’t expect that I shall return. In fact, I mean not to.

- Bilbo: My dear Bagginses and Boffins. [cheers] Tooks and Brandybucks. [cheers] Grubbs! [cheers] Chubbs! [cheers] Hornblowers! [cheers] Bolgers! [cheers] Bracegirdles! [cheers] And Proudfoots!

- Proudfoot: Proudfeet!

- Bilbo: Proudfoots. Today is my one hundred and eleventh birthday! [cheers] Alas, eleventy one years is far too short a time to live among such excellent and admirable Hobbits. I don’t know half of you half as well as I should like and I like less than half of you half as well as you deserve. [confused silence] I, uh, I have things to do…I’ve put this off for far too long. I regret to announce this is the end. I’m going now. I bid you all a very fond farewell. Goodbye. [puts the Ring on and vanishes]

- Bilbo: You will keep an eye on Frodo, won’t you?

- Gandalf: Two eyes, as often as I can spare them.

- Bilbo: I’m leaving everything to him.

- Gandalf: What about this ring of yours? Is that staying too?

- Bilbo: Yes, yes. It’s in an envelope over there on the mantelpiece. No, wait, it’s… here in my pocket. Isn’t that odd, now? And yet, why not? Why shouldn’t I keep it?

- Gandalf: I think you should leave the ring behind, Bilbo. Is that so hard?

- Bilbo: Well, no… and yes. [agitated] Now it comes to it, I don’t feel like parting with it! It’s mine, I found it! It came to me!

- Gandalf: There’s no need to get angry.

- Bilbo: Well, if I’m angry, it’s your fault! [to himself] It’s mine… my own… [Hisses] My precious…

- Gandalf: [alarmed] «Precious»? It’s been called that before, but not by you.

- Bilbo: [angry] Oh, what business is it of yours what I do with my own things?!

- Gandalf: I think you’ve had that ring quite long enough.

- Bilbo: You want it for yourself!

- Gandalf: BILBO BAGGINS! [The room grows darker and Gandalf’s voice grows deeper] DO NOT TAKE ME FOR SOME CONJURER OF CHEAP TRICKS! I AM NOT TRYING TO ROB YOU! [gently and normally] I’m trying to help you. [Bilbo, frightened, hugs Gandalf] All your long years, we have been friends. Trust me, as you once did. Let it go.

- Bilbo: You’re right, Gandalf. The ring must go to Frodo. Well, it’s late, the road is long.

- Gandalf: [sternly] Bilbo. The ring is still in your pocket.

- Bilbo: [sheepish] Oh, yes… of course.

- [With great effort, he drops the ring to the floor, and rushes outside, appearing relieved]

- Bilbo: I’ve thought of an ending for my book. «And he lived happily ever after… to the end of his days.»

- Gandalf: And I’m sure you will, my friend.

- Bilbo: Goodbye, Gandalf.

- [Bilbo and Gandalf shake hands]

- Gandalf: Goodbye, dear Bilbo. [Bilbo sets off] Until our next meeting.

- Frodo: [Reading the inscription on the Ring] There are markings. It’s some form of Elvish. I can’t read it.

- Gandalf: There are few who can. The language is that of Mordor, which I will not utter here.

- Frodo: Mordor?

- Gandalf: In the common tongue it says, «One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them.»

- Gandalf: This is the One Ring, forged by the Dark Lord Sauron, in the fires of Mount Doom, taken by Isildur from the hand of Sauron himself.

- Frodo: Bilbo found it… in Gollum’s cave.

- Gandalf: Yes. For 60 years, the Ring lay quiet in Bilbo’s keeping, prolonging his life, delaying old age. But no longer, Frodo. Evil is stirring in Mordor. The Ring has awoken. It’s heard its Master’s call.

- Frodo: But he was destroyed. Sauron was destroyed!

- [The Ring whispers]

- Gandalf: No, Frodo. The spirit of Sauron endured. His life-force is bound to the Ring, and the Ring survived. Sauron has returned. His Orcs have multiplied; his fortress of Barad-dûr is rebuilt in the land of Mordor. Sauron needs only this Ring to cover all the lands in a second darkness. He is seeking it — seeking it, all his thought is bent on it. The Ring yearns above all else to return to the hand of its Master. They are one, the Ring and the Dark Lord. Frodo… he must never find it.

- Frodo: All right. We put it away. We keep it hidden; we never speak of it again. No one knows it’s here do they? Do they, Gandalf?

- Gandalf: There is one other who knew Bilbo had the Ring. I looked everywhere for the creature Gollum, but the enemy found him first. I don’t know how long they tortured him, but amidst the endless screams and inane babble, they discerned two words.

- Gollum: «Shire»! «Baggins«!

- Frodo: «Shire»? «Baggins«? But that will lead them here! Take it, Gandalf! Take it!

- Gandalf: No, Frodo.

- Frodo: You must take it!

- Gandalf: You cannot offer me this Ring!

- Frodo: I’m giving it to you!

- Gandalf: Don’t… tempt me, Frodo! I dare not take it. Not even to keep it safe. Understand, Frodo, I would use this Ring from the desire to do good. But through me, it would wield a power too great and terrible to imagine.

- Frodo: But it cannot stay in the Shire!

- Gandalf: No! No, it can’t.

- Frodo: [pause, then realizes his burden, gripping the Ring] What must I do?

- [Gandalf finds Sam spying on him and Frodo]

- Gandalf: CONFOUND IT ALL, SAMWISE GAMGEE! Have you been eavesdropping?!

- Sam: I ain’t been droppin’ no eaves sir, honest. I was just cutting the grass under the window there, if you’ll follow me.

- Gandalf: A little late for trimming the verge, don’t you think?

- Sam: I heard raised voices–

- Gandalf: What did you hear?! Speak!

- Sam: N-nothing important! That is, I heard a good deal about a Ring and Dark Lord and something about the end of the world, but… Please, Mr. Gandalf, sir, don’t hurt me. Don’t turn me into anything… unnatural.

- Gandalf: [smiles at Frodo] No… perhaps not. I’ve thought of a better use for you.

- [Later, Frodo and Gandalf leave the Shire with a horse next to them, initially appearing as if Gandalf turned turned Sam into a horse.]

- Gandalf: Come along, Samwise, keep up! [Sam appears behind them, following them & struggling with all the luggage]

- Sam: This is it.

- Frodo: What?

- Sam: If I take one more step, I’ll be the farthest away from home I’ve ever been.

- Frodo: Come on, Sam. Remember what Bilbo used to say: «It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no telling where you might be swept off to.»

- Saruman: Sauron has regained much of his former strength. He cannot yet take physical form, but his spirit has lost none of its potency. Concealed within his fortress, the Lord of Mordor sees all. His gaze pierces cloud, shadow, earth, and flesh. You know of what I speak, Gandalf. A Great Eye, lidless, wreathed in flame.

- Gandalf: The Eye of Sauron.

- Saruman: He is gathering all evil to him. Very soon, he will have summoned an army great enough to launch an assault upon Middle Earth.

- Gandalf: You know this? How?

- Saruman: I have seen it.

- Gandalf: A Palantír is a dangerous tool, Saruman.

- Saruman: Why? Why should we fear to use it? [uncovers the Palantír he keeps]

- Gandalf: They are not all accounted for, the lost Seeing Stones. We do not know who else may be watching. [recovers the Palantír; the Eye of Sauron is shown to be agitated by this]

- Saruman: The hour is later than you think. Sauron’s forces are already moving. The Nine have left Minas Morgul.

- Gandalf: The Nine?

- Saruman: They crossed the River Isen on Midsummer’s Eve, disguised as riders in black.

- Gandalf: [Shocked] They’ve reached the Shire?!

- Saruman: They will find the Ring… and kill the one who carries it.

- Gandalf: Frodo!

- [He moves towards the the doors, but Saruman seals them all]

- Saruman: You did not seriously think that a Hobbit could contend with the will of Sauron? There are none who can. Against the power of Mordor, there can be no victory. We must join with him, Gandalf. We must join with Sauron. It would be wise, my friend.

- Gandalf: [Disgusted] Tell me, «friend»… when did Saruman the Wise abandon reason for madness?!

- [Angered, Saruman uses his powers to throw Gandalf to the floor. The two fight, but Saruman gains the upper hand]

- Saruman: I gave you the choice of aiding me willingly! But you have elected the way of pain!

- [Strider has ushered Frodo into his room]

- Strider: You draw far too much attention to yourself, Mr. «Underhill.»

- Frodo: What do you want?

- Strider: More caution from you. That is no mere trinket you carry.

- Frodo: I carry nothing.

- Strider: Indeed. I can avoid being seen if I wish, but to disappear entirely; that is a rare gift.

- Frodo: Who are you?

- Strider: Are you frightened?

- Frodo: Yes.

- Strider: Not nearly frightened enough. I know what hunts you. [Strider spins round and draws his sword as Sam, Merry and Pippin storm in]

- Sam: Let him go! Or I’ll have you, longshanks!

- Strider: You have a stout heart, little Hobbit, but that will not save you. You can no longer wait for the wizard, Frodo. They are coming.

- Frodo: [overhearing the Black Riders] What are they?

- Strider: They were once Men. Great Kings of Men. Then Sauron the Deceiver gave to them nine Rings of Power. Blinded by their greed, they took them without question, one by one falling to darkness. Now, they are slaves to his will. They are the Nazgûl, Ringwraiths, neither living nor dead. At all times they feel the presence of the Ring, drawn to the power of the One. They will never stop hunting you.

- Strider: Gentlemen, we do not stop till nightfall.

- Pippin: What about breakfast?

- Strider: You already had it.

- Pippin: We had one, yes. What about second breakfast?

- [Strider walks away]

- Merry: I don’t think he knows about second breakfast, Pip.

- Pippin: What about elevenses? Luncheon? Afternoon tea? Dinner? Supper? He knows about them, doesn’t he?

- Merry: I wouldn’t count on it.

- [Strider tosses them apples]

- Arwen: [in Elvish, to the wounded Frodo] Frodo. I am Arwen. I’ve come to help you. Hear my voice. Come back to the light.

- Merry: Who is she?

- Arwen: [kneeling down by Frodo] Frodo…

- Sam: She’s an Elf.

- [Arwen and Aragorn inspect Frodo’s wound]

- Arwen: He’s fading. He’s not going to last. We must get him to my father. [Aragorn carries Frodo towards Arwen’s horse Asfaloth] I’ve been looking for you for two days.

- Merry: Where are you taking him?

- Arwen: There are five Wraiths behind you. Where the other four are, I do not know.

- Strider: [Elvish] Stay with the hobbits. I’ll send horses for you.

- Arwen: [Elvish] I’m the faster rider, I’ll take him.

- Strider: [Elvish] The road is too dangerous.

- Pippin: What are they saying?

- Arwen: [Elvish] Frodo is dying. If I can get across the river, the power of my people will protect him. [common tongue] I do not fear them.

- Strider: [Elvish] As you wish. [common tongue] Arwen, ride hard. Don’t look back.

- Arwen: [Elvish] Run fast, Asfaloth! Run fast! [she rides away with Frodo]

- Sam: What are you doing?! Those Wraiths are still out there!

- Ringwraith: Give up the Halfling, She-Elf!

- Arwen: [Draws her sword] If you want him, come and claim him!

- Saruman: The friendship of Saruman is not lightly turned aside. One ill turn deserves another. It is over. Embrace the power of the Ring… or embrace your own destruction!

- [Gandalf has noticed Gwaihir, the Great Eagle, approaching]

- Gandalf: There is only one Lord of the Ring. Only one who can bend it to his will. And he does not share power! [jumps onto the Eagle’s back and escapes]

- Saruman: [watching them fly off] So you have chosen death.

- Frodo: [reading Bilbo’s book] «There and Back Again: A Hobbits Tale by Bilbo Baggins.» This is wonderful.

- Bilbo: I meant to go back. Wander the paths of Mirkwood, visit Lake-town, see the Lonely Mountain again. But age it seems has finally caught up with me

- Frodo: [looks at a map of the Shire] I miss the Shire. I spent all my childhood pretending I was off somewhere else. Off with you on one of your adventures. My own adventure turned out to be quite different. I’m not like you, Bilbo.

- Bilbo: My dear boy…

- Elrond: [watching Frodo] His strength returns.

- Gandalf: That wound will never fully heal. He will carry it the rest of his life.

- Elrond: And yet, to have come so far still bearing the Ring, the Hobbit has shown extraordinary resilience to its evil.

- Gandalf: It is a burden he should never have had to bear. We can ask no more of Frodo.

- Elrond: Gandalf, the enemy is moving. Sauron’s forces are massing in the East; his Eye is fixed on Rivendell. And Saruman, you tell me, has betrayed us. Our list of allies grows thin.

- Gandalf: His treachery runs deeper than you know. With foul craft, Saruman has crossed Orcs with Goblin-Men. He’s breeding an army in the caverns of Isengard. An army that can move in sunlight, and cover great distance at speed. Saruman is coming for the Ring.

- Elrond: This evil cannot be concealed by the power of the Elves. We do not have the strength to fight both Mordor and Isengard! Gandalf, the Ring cannot stay here. This peril belongs to all Middle Earth. They must decide now how to end it. The time of the Elves is over. My people are leaving these shores. Who will you look to when we’ve gone? The Dwarves? They hide in their mountains, seeking riches. They care nothing for the troubles of others.

- Gandalf: It is in Men that we must place our hope.

- Elrond: [bitterly] Men? Men are weak. The race of Men is failing. The Blood of Númenor is all but spent, its pride and dignity forgotten. It is because of Men the Ring survives. I was there, Gandalf. I was there three thousand years ago, when Isildur took the Ring. I was there the day the strength of Men failed.

- Elrond: (flashback) Isildur, hurry! Follow me!

- Elrond: I led Isildur into the heart of Mount Doom, where the Ring was forged – the one place it could be destroyed.

- Elrond: (flashback) Cast it into the fire! (Isildur hesitates) Destroy it!

- Isildur: (flashback) No. (Isildur leaves Mount Doom)

- Elrond: (flashback) Isildur!

- Elrond: It should have ended that day, but evil was allowed to endure. Isildur kept the Ring. The line of Kings was broken. There’s no strength left in the World of Men. They’re scattered, divided, leaderless.

- Gandalf: There is one who could unite them. One who could reclaim the Throne of Gondor.

- Elrond: He turned from that path a long time ago. He has chosen exile.

- Boromir: You are no elf?

- Aragorn: Men of the South are welcome here.

- Boromir: Who are you?

- Aragorn: I’m a friend of Gandalf the Grey.

- Boromir: Then we are here on a common purpose… friend.

- [Boromir examines the shards of Narsil]

- Boromir: The shards of Narsil. [picks up hiltpiece] The blade that cut the ring from Sauron’s hand. [cuts himself with the sword] It’s still sharp. [looks at Aragorn] But no more than a broken heirloom. [drops hiltpiece in an almost-disrespectful manner]

- Arwen: [Elvish] Do you remember when we first met?

- Aragorn: [Elvish] I thought I had wandered into a dream.

- Arwen: [Elvish] Long years have passed. You did not have the cares you carry now. Do you remember what I told you?

- Aragorn: You said you’d bind yourself to me, forsaking the immortal life of your people.

- Arwen: And to that I hold. I would rather share one lifetime with you than face all the ages of this world alone. [hands him her pendant] I choose a mortal life.

- Aragorn: You cannot give me this.

- Arwen: It is mine to give to whom I will. Like my heart.

- [At the Council of Elrond]

- Elrond: Strangers from distant lands, friends of old, you have been summoned here to answer the threat of Mordor. Middle Earth stands upon the brink of destruction; none can escape it. You will unite or you will fall. Each race is bound to this fate, this one doom. Bring forth the Ring, Frodo.

- [Frodo puts the Ring on a stand for all to see]

- Boromir: So it is true. [Stands and walks towards the Ring] In a dream, I saw the Eastern sky grow dark. But in the West, a pale light lingered. A voice was crying, «The doom is near at hand, Isildur’s Bane is found.» [Reaches for the Ring] Isildur’s Bane…

- Elrond: Boromir!

- Gandalf: [Speaking the words engraved on the Ring] Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul, ash nazg thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul!

- [The light darkens and the air rumbles; Boromir backs away from the Ring]

- Elrond: Never before has anyone dared utter words of that tongue here, in Imladris.

- Gandalf: I do not ask for pardon, Master Elrond, for the Black Speech of Mordor may yet be heard in every corner of the West! The Ring is altogether evil.

- Boromir: But it is a gift. A gift to the foes of Mordor. Why not use this Ring? Long has my father, the Steward of Gondor, kept the forces of Mordor at bay. By the blood of our people are your lands kept safe! Give Gondor the weapon of the enemy! Let us use it against him!

- Aragorn: You cannot wield it. None of us can. The One Ring answers to Sauron alone. It has no other master.

- Boromir: And what would a Ranger know of this matter?

- Legolas: This is no mere Ranger. He is Aragorn, son of Arathorn. You owe him your allegiance.

- Boromir: Aragorn? This is Isildur’s heir?

- Legolas: And heir to the throne of Gondor.

- Aragorn: [in Elvish] Sit down, Legolas.

- Boromir: Gondor has no King. Gondor needs no King.

- Gandalf: Aragorn is right. We cannot use it.

- Elrond: You have only one choice. The Ring must be destroyed.

- Gimli: What are we waiting for?

- [He roars and strikes the Ring with his axe; the axe breaks, leaving the Ring perfectly intact]

- Elrond: The Ring cannot be destroyed, Gimli, son of Glóin, by any craft that we here possess. The Ring was made in the fires of Mount Doom. Only there can it be unmade. It must be taken deep into Mordor and cast back into the fiery chasm from whence it came! One of you… must do this.

- Boromir: One does not simply walk into Mordor. Its Black Gates are guarded by more than just Orcs. There is evil there that does not sleep. The Great Eye is ever watchful. It is a barren wasteland, riddled with fire, ash and dust. The very air you breathe is a poisonous fume. Not with ten thousand men could you do this. It is folly!

- Legolas: Have you heard nothing Lord Elrond has said? The Ring must be destroyed!

- Gimli: And I suppose you think you’re the one to do it?!

- Boromir: And if we fail, what then?! What happens when Sauron takes back what is his?!

- Gimli: I will be dead before I see the Ring in the hands of an Elf! [The council argue amongst themselves] Never trust an Elf!

- Gandalf: Do you not understand?! While you bicker amongst yourselves, Sauron’s power grows! None will escape it! You’ll all be destroyed!

- [As Frodo focuses on the Ring, everyone’s arguing voices are drowned out by Sauron’s voice reciting the Ring’s inscription. Frodo gets to his feet]

- Frodo: I will take it! [All continue to argue] I will take it! [All fall silent] I will take the Ring to Mordor. Though… I do not know the way.

- Gandalf: I will help you bear this burden, Frodo Baggins, for as long as it is yours to bear.

- Aragorn: If by my life or death I can protect you, I will. You have my sword…

- Legolas: And you have my bow.

- Gimli: And my axe.

- Boromir: You carry the fate of us all, little one. If this is indeed the will of the Council, then Gondor will see it done.

- [Sam rushes in]

- Sam: Hey! Mr. Frodo’s not going anywhere without me!

- Elrond: No, indeed. It is hardly possible to separate you, even when he is summoned to a secret council, and you are not.

- Merry: We’re coming, too! [Elrond looks astounded] You’d have to send us home tied up in a sack to stop us!

- Pippin: Anyway, you need people of intelligence on this sort of mission… quest… thing.

- Merry: That rules you out, Pip.

- Elrond: Nine companions. So be it. You shall be the Fellowship of the Ring.

- Pippin: Great! Where are we going?

- Gandalf: Frodo, come and help an old man. How’s your shoulder?

- Frodo: Better than it was.

- Gandalf: And the Ring? You feel its power growing, don’t you? I’ve felt it too. You must be careful now. Evil will be drawn to you from outside the Fellowship… and, I fear, from within.

- Frodo: Who then, do I trust?

- Gandalf: You must trust yourself. Trust your own strengths.

- Frodo: What do you mean?

- Gandalf: There are many powers in this world, for good or for evil. Some are greater than I am. And against some, I have not yet been tested.

- [Gandalf has tried to open the Doors of Durin, to no avail]

- Gandalf: I once knew every spell in all the tongues of Orcs.

- Pippin: What are you going to do, then?

- Gandalf: Knock your head against these doors, Peregrin Took! And if that does not shatter them, and I am allowed a little peace from foolish questions, I will try to find the opening words.

- Pippin: [Whispering] Merry.

- Merry: What?

- Pippin: I’m hungry.

- Frodo: There’s something down there!

- Gandalf: It’s Gollum.

- Frodo: Gollum?

- Gandalf: He’s been following us for three days.

- Frodo: He escaped the dungeons of Barad-dûr?

- Gandalf: Escaped… or was set loose. Now the Ring has drawn him here. He hates and loves the Ring, as he hates and loves himself. He will never be rid of his need for it. Sméagol’s life is a sad story. Yes, Sméagol he was once called… before the Ring found him. Before it drove him mad.

- Frodo: It’s a pity Bilbo didn’t kill him when he had the chance.

- Gandalf: Pity? It was pity that stayed Bilbo’s hand. Many that live deserve death, and some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them, Frodo? Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the very wise cannot see all ends. My heart tells me that Gollum has some part to play, for good or ill, before this is over. The pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many.

- Frodo: I wish the Ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened.

- Gandalf: So do all who live to see such times; but that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us. There are other forces at work in this world, Frodo, besides the will of evil. Bilbo was meant to find the Ring. In which case, you were also meant to have it. And that is an encouraging thought.

- Boromir: What is this new devilry?

- Gandalf: A Balrog… a demon of the Ancient World. This foe is beyond any of you. RUN!

- Gimli: Stay close, young Hobbits. They say a great sorceress lives in these woods. An Elf witch of terrible power. All who look upon her fall under her spell…

- Galadriel: [in Frodo’s mind] Frodo.

- Gimli: …and are never seen again.

- Galadriel: [to Frodo] Your coming to us is as the footsteps of doom. You bring great evil here, Ringbearer.

- Sam: Mr. Frodo?

- Gimli: Well, here’s one Dwarf she won’t ensnare so easily. I have the eyes of a hawk and the ears of a fox!

- [Haldir and a group of elves appear, holding Gimli and the others at arrow point]

- Haldir: The Dwarf breathes so loud, we could have shot him in the dark.

- Celeborn: Eight there are here, yet nine there were set out from Rivendell. Tell me, where is Gandalf? For I much desire to speak with him.

- Galadriel: He has fallen into shadow. The Quest stands upon the edge of knife. Stray but a little and it will fail, to the ruin of all. Yet hope remains while the company is true. Do not let your hearts be troubled. Go now and rest for you are weary with sorrow and much toil. Tonight you will sleep in peace. [to Frodo, telepathically] Welcome, Frodo of the Shire… one who has seen THE EYE!

- Aragorn: Take some rest. These borders are well protected.

- Boromir: I will find no rest here. I heard her voice inside my head. She spoke of my father and the fall of Gondor, and she said to me: «Even now, there is hope left.» But I cannot see it. It is long since we had any hope. My father is a noble man, but his rule is failing and our… our people lose faith. He looks to me to make things right and I would do it, I would see the glory of Gondor restored. Have you ever seen it, Aragorn? The White Tower of Ecthelion, glimmering like a spike of pearl and silver. Its banners caught high in the morning breeze. Have you ever been called home by the clear ringing of silver trumpets?

- Aragorn: I have seen the White City… long ago.

- Boromir: One day our paths will lead us there, and the tower guards shall take up the call: «The Lords of Gondor have returned!»

- Galadriel: Will you look into the mirror?

- Frodo: What will I see?

- Galadriel: Even the wisest cannot tell. For the mirror shows many things. Things that were, things that are, and some things… that have not yet come to pass.

- [Looking into the mirror, Frodo sees the Orcs enslave the Hobbits and reduce the Shire to an industrial wasteland; finally, the Eye of Sauron causes him to stumble backwards]

- Galadriel: I know what it is you saw; for it is also in my mind. [in Frodo’s mind] It is what will come to pass if you should fail. The Fellowship is breaking. It is already begun. He will try to take the Ring. You know of whom I speak. One by one, it will destroy them all.

- Frodo: If you ask it of me, I will give you the One Ring. [holds out the Ring to Galadriel]

- Galadriel: You offer it to me freely? I do not deny that my heart has greatly desired this… [Suddenly fierce] In place of a Dark Lord, you would have a Queen! Not dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Dawn! Treacherous as the Sea! Stronger than the foundations of the Earth! All shall love me and despair! [Stops, shaken, and becomes calm again] I pass the test. I will diminish, and go into the West… and remain Galadriel.

- Frodo: I cannot do this alone.

- Galadriel: You are a Ringbearer, Frodo. To bear a Ring of Power is to be alone. [holds up her hand to show a silver, flower-jeweled Ring] This is Nenya, the Ring of Adamant, and I am its keeper. This task was appointed to you and if you do not find a way, no one will.

- Frodo: I know what I must do, it’s just that… I’m afraid to do it.

- Galadriel: Even the smallest person can change the course of the future.

- Saruman: Do you know how the Orcs first came into being? They were Elves once. Taken by the Dark Powers. Tortured, and mutilated. A ruined and terrible form of life. And now… perfected. My fighting Uruk-hai… Whom do you serve?

- Lurtz: Saruman!

- Saruman: [to his army of Uruk-hai soldiers] Hunt them down! Do not stop until they are found! You do not know pain; you do not know fear! You will taste man-flesh!! [to Lurtz] One of the Halflings carries something of great value. Bring them to me alive…and unspoiled. Kill the others!

- [Extended Edition only]

- Aragorn: Gollum. He’s tracked us since Moria. I hoped we would lose him on the river, but he’s too clever a waterman.

- Boromir: And if he alerts the enemy to our whereabouts, it’ll make the crossing even more dangerous.

- Sam: Have some food, Mr. Frodo.

- Frodo: No, Sam.

- Sam: You haven’t eaten anything all day. And you’re not sleeping, either. Don’t think I haven’t noticed. Mr. Frodo!

- Frodo: I’m all right.

- Sam: But you’re not. I’m here to help you. I promised Gandalf that I would.

- Frodo: You can’t help me, Sam. Not this time. Get some sleep.

- Boromir: Minas Tirith is the safer road. You know that. From there, we can regroup. Strike out at Mordor from a place of strength.

- Aragorn: There is no strength from Gondor that can avail us.

- Boromir: You were quick enough to trust the Elves! Have you so little faith in your own people? Yes, there is weakness! There is frailty! But there is courage, also! And honor to be found in men, but you will not see that! You’re afraid! All your life, you have lived in the shadows, scared of who you are, of what you are!

- Aragorn: I will not lead the Ring within a hundred leagues of your city!

- Boromir: [carrying gathered wood] None of us should wander alone. You, least of all. So much depends on you. [Frodo is silent] Frodo? I know why you seek solitude. You suffer. I see it day by day. You’re sure you do not suffer needlessly? There are other ways, Frodo. Other paths that we might take.

- Frodo: I know what you would say. And it would seem like wisdom, but for the warning in my heart.

- Boromir: Warning? Against what? We’re all afraid, Frodo, but to let that fear drive us to destroy what hope we have, don’t you see that is madness?

- Frodo: There is no other way.

- Boromir: [frustrated] I ask only for the strength to defend my people! [throws down the wood] If you would but lend me the Ring…

- Frodo: No!

- Boromir: Why do you recoil? I am no thief.

- Frodo: You are not yourself.

- Boromir: What chance do you think you have? They will find you. They will take the Ring. And you will beg for death before the end! [Frodo tries to walk away] You fool! It is not yours, save by unhappy chance! It could have been mine! It should be mine! [pins Frodo to the ground] Give it to me! Give it to me!

- Frodo: No!

- Boromir: Give it to me!

- Frodo: No! [puts the Ring on his finger and slips away, invisible]

- Boromir: I see your mind. You will take the Ring to Sauron! You will betray us! You go to your death, and the death of us all! Curse you! Curse you, and all the Halflings! [suddenly gets ahold of himself and starts choking up] Frodo? Frodo. What have I done? Please, Frodo. Frodo, I’m sorry! Frodo!

- Aragorn: Frodo?

- Frodo: It has taken Boromir.

- Aragorn: Where is the Ring?

- Frodo: Stay away! [Frodo bolts, and Aragorn follows him]

- Aragorn: [confused] Frodo! I swore to protect you.

- Frodo: Can you protect me from yourself? [holds out the Ring] Would you destroy it?

- [Aragorn reaches out for the Ring, hearing Sauron’s voice whisper to him. He pushes Frodo’s hand away]

- Aragorn: I would have gone with you to the end. Into the very fires of Mordor.

- Frodo: I know. Look after the others. Especially Sam. He will not understand.

( Boromir Grunts )

- Boromir: [dying] They took the little ones.

- Aragorn: Be still.

- Boromir: Frodo… Where is Frodo?

- Aragorn: I let Frodo go.

- Boromir: Then you did what I could not. I tried to take the Ring from him.

- Aragorn: The Ring is beyond our reach now.

- Boromir: Forgive me. I could not see it. I have failed you.

- Aragorn: No, Boromir. You fought bravely. You kept your honor. [tries to remove an arrow from Boromir]

- Boromir: Leave it. It is over. The world of men shall fall. All will come to darkness. And my city to ruin.

- Aragorn: I do not know what strength is in my blood, but I swear to you I will not let the White City fall… Nor our people fail.

- Boromir: Our people… I would have followed you, my brother… my captain… my king. [dies]

- Aragorn: Be at peace, Son of Gondor. [kisses Boromir’s head] They will look for his coming from the white tower, but he will not return.

- Frodo: Go back, Sam! I’m going to Mordor alone.

- Sam: Of course you are. And I’m coming with you!

- [Sam wades in the water]

- Frodo: You can’t swim! Sam! [Sam sinks below the surface] SAM!

- [Sam nearly drowns, but Frodo pulls him up into the raft]

- Sam: I made a promise, Mr. Frodo. A promise! «Don’t you leave him, Samwise Gamgee.» And I don’t mean to! I don’t mean to.

- Legolas: Hurry! Frodo and Sam have reached the eastern shore.

- [Aragorn does not move]

- Legolas: You mean not to follow them.

- Aragorn: Frodo’s fate is no longer in our hands.

- Gimli: Then it has all been in vain. The Fellowship has failed.

- Aragorn: Not if we hold true to each other. We will not abandon Merry and Pippin to torment and death. Not while we have strength left. Leave all that can be spared behind. We travel light. Let’s hunt some Orc!

- Gimli: Yes!

- [Last lines]

- Frodo: Mordor… I hope the others find a safer road.

- Sam: Strider’ll look after ’em.

- Frodo: I don’t suppose we’ll ever see them again.

- Sam: We may yet, Mr Frodo. We may.

- Frodo: Sam… I’m glad you’re with me.

Taglines[edit]

- One Ring to rule them all.

- The Legend Comes to Life

- One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them.

- Fate Has Chosen Him. A Fellowship Will Protect Him. Evil Will Hunt Them.

- Middle-earth comes to life…

- Even the smallest person can change the course of the future.

- All you have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to you.

- Power can be held in the smallest of things…

- Its power corrupts all who desire it. Only one has the will to resist it. A Fellowship of Nine must destroy it.

Cast[edit]

- Elijah Wood as Frodo Baggins

- Ian McKellen as Gandalf the Grey

- Liv Tyler as Arwen Undómiel

- Viggo Mortensen as Aragorn / Strider

- Sean Astin as Samwise Gamgee

- Cate Blanchett as Lady Galadriel

- John Rhys-Davies as Gimli

- Billy Boyd as Peregrin Took

- Dominic Monaghan as Meriadoc Brandybuck

- Orlando Bloom as Legolas

- Christopher Lee as Saruman the White

- Hugo Weaving as Lord Elrond

- Sean Bean as Boromir

- Ian Holm as Bilbo Baggins

- Andy Serkis as Sméagol / Gollum

- Marton Csokas as Celeborn

- Craig Parker as Haldir

- Lawrence Makoare as Lurtz

- Bret McKenzie as Figwit

- Carole Jeghers as Animals’ vocal effects

See also[edit]

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1978)

- The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

- The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)

- The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012)

- The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013)

- The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014)

External links[edit]

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring quotes at the Internet Movie Database

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Official Lord of the Rings Site

J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic The Lord of the Rings has captivated readers and viewers alike for generations. While the legendary author may have passed away a half a century ago, his monumental story lives on and only continues to gain steam via movies and TV. And one of the primary ways Tolkien’s trilogy has managed to captivate such a large audience is through the emotional rise and fall of its many compelling characters. From Boromir’s redemptive exit to Sauron’s crumbling catastrophe, The Lord of the Rings trilogy is littered with epic sacrifices, gruesome deaths, and both happy and sad endings.

We wanted to see just how legendary each deceased character’s final moments ended up being, based on the litmus test of what they were talking about when they perished. With that in mind, we decided to round up the last words of every fallen Lord of the Rings hero and villain to do some comparing and contrasting.

(Be warned — major spoilers below!)

Let’s set up some ground rules

Before we get started, it’s important to point out how we’re going to go about this. For starters, we’ve gone ahead and gathered the heroes and villains who die during the story. We’ve included major heroes from flashbacks, as well as any primary characters who pass on during the story itself.

The other important question to answer before we start is what version of each character’s «last words» we’re going to go with. After all, it’s not like we’re working with a single iteration. Obviously, there are Tolkien’s original books, but added into the mix are two cinematic adaptations. First, there’s the initial, two-part cartoon created in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and of course, we have Peter Jackson’s live-action trilogy.

We’ve decided to focus on two of these sources. Whenever possible, we’ll go with a combination of Peter Jackson’s adaptations and the original books. Even then, things will get dicey at points. Many of the fallen characters don’t necessarily have concrete «last words» in either version. When this happens, we’ll make sure to give a brief rundown of their final moments. After all, actions speak louder than words, right?

Okay, without further ado, here are the last words of every fallen Lord of the Rings hero and villain.

Isildur’s last words revolve around the One Ring

Isildur is the hero who cuts the One Ring from Sauron’s hand, only to fall to the shiny trinket’s hidden power not long afterward. While not a primary character in The Lord of the Rings story, Isildur shows up early in The Fellowship of the Ring film and is referenced throughout the narrative since his actions literally set up the entire «destroy the Ring» scenario. Heck, the Ring is literally referred to as «Isildur’s Bane» since owning it leads to his death — which is why we’re here.

Isildur dies when he’s ambushed by orcs and shot while trying to escape across the Great River. In the film, he doesn’t talk but is shown dead, floating in the water. Chronologically, if you back up enough, this would make his last words in the film officially, «No,» spoken nefariously as he rejects Elrond’s plea for him to throw the One Ring into the fires of Mount Doom.

However, in Tolkien’s original writings — particularly in the book Unfinished Tales — the Númenórean king’s final line is a bit juicer. Ambushed and about to be killed, Isildur’s son, Elendur, tells his father to escape and bring the One Ring to the keepers of the three elven rings before it’s recaptured. His father replies, «I knew that I must do so; but I feared the pain. Nor could I go without your leave. Forgive me, and my pride that has brought you to this doom.» Epic final words spoken from a soon-to-be-deceased father to his soon-to-be-deceased son.

Elendil and Gil-galad both perish fighting Sauron

We need to take a minute to address Isildur’s father, Elendil, along with elven high king Gil-galad. Elendil is the first king of the realms of Gondor and Arnor, which are set up in Middle-earth at the end of the Second Age. And Gil-galad is an elven leader who rules over the bulk of the elves that remain in Middle-earth at that time. Eventually, Sauron picks a fight with them, and the two leaders form the Last Alliance, a massive coalition that gathers everyone around in order to attack Sauron and defeat him on his home turf in Mordor.

The Last Alliance is ultimately victorious but at the expense of both of these high kings. The leaders are killed in combat with Sauron just before Isildur cuts the One Ring from the villain’s hand. In fact, Isildur even does so using his father’s broken sword. At the council of Elrond, the leader of Rivendell, who was present at their deaths, recalls the scene, saying that, «I beheld the last combat on the slopes of [Mount Doom], where Gil-galad died, and Elendil fell, and Narsil broke beneath him…»

While neither character is officially given final words, they appear in both the books and films, and their bravery and deaths set the stage for Sauron’s first defeat at the end of the Second Age.

Déagol’s last words are incredibly heartbreaking

Everyone is fascinated by Sméagol, the hobbit-like creature eventually known as Gollum. He’s a pitiable wretch whose life is warped out of recognition after he encounters the One Ring. He eventually convinces himself that he got the bauble as a birthday present, but as fans know, the creature hardly receives the Ring in a gift-wrapped box. He steals it from a good friend, and in the process, murders his companion.

The colleague in question? One Déagol, another hobbit-like creature. One day, five centuries before the Lord of the Rings story begins, the pair of friends decide to go on a fishing excursion together, and Déagol is pulled into the water by a monstrous fish. He’s dragged to the bottom, where he finds the One Ring. When Sméagol sees the piece of jewelry, he demands that his friend give it to him since it’s his birthday. In the opening scene of The Return of the King, the poor fellow responds to Sméagol’s unreasonable request with, «Why?» And after that simple question, he winds up dead.

In the book, Déagol starts off with «why,» but he follows this up with the final words, «I don’t care. I have given you a present already, more than I could afford. I found this, and I’m going to keep it.» It’s an extra factoid that makes Sméagol’s violent reaction that much more cold-blooded.

Gandalf’s ‘last’ words are sad and stirring

Okay, okay. Gandalf doesn’t technically die. But he does «fall,» so we’re including him here. In fact, while his spirit lives on in Gandalf the White, there are some fairly significant implications that after Gandalf the Grey defeats the Balrog, his physical body is more or less reincarnated as Gandalf the White.

That said, Gandalf’s contest with the Balrog in Moria leaves us with one of the absolute best lines in all of The Lord of the Rings trilogy. In the books, he shouts, «You cannot pass!» And in the films, he thunders, «You shall not pass!» The line, delivered as the wizard stands on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, is enough to send shivers down the back. As he falls into the deep abyss, though, Gandalf’s official «last words» aren’t said in defiance to his enemies. Rather, they’re a cheeky command to his friends. As he falls he cries out, «Fly, you fools!»

Identical in both book and movie, the words simultaneously communicate a sense of care and frustration that sends the rest of the Fellowship members scampering out of Moria lickety-split. While he does return later in the story, Gandalf’s initial sacrifice is still a powerful moment that earns its place on this list in spades.

The Balrog doesn’t technically have last words … or any words

One of the villains that finds an untimely death earlier in the story is the Balrog. Also known as Durin’s Bane, the fiery demon comes across as indestructibly powerful in The Fellowship of the Ring, but early in his story, he’s actually a refugee fleeing from the catastrophic War of Wrath. In that war, Sauron’s original master, Morgoth, is defeated, and his surviving servants scatter across the continent, looking for places to hide.

The Balrog relocates deep under the thriving dwarven kingdom of Khazad-dûm for nearly 2,000 years. Eventually, though, he’s disturbed by the dwarves, at which point he drives them away, and the area becomes known as Moria or the «Black Pit.» When the Balrog attacks the Fellowship of the Ring, the quietly overpowered Gandalf ends up being the one who confronts the devil on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm.

The pair of combatants fall deep into the abyss below, where they begin a knock-down, drag-out duel that progresses from far underground all the way up to the top of the mountains above. There, with clouds, fire, and lightning surrounding them, the Balrog is eventually killed by Gandalf, breaking the mountainside as he falls. As with multiple villains in Tolkien’s writing, the Balrog doesn’t get any last words — or any words at all, for that matter — but its death is a momentous event, both because it means Gandalf is still alive and because it frees up Khazad-dûm for the dwarves to eventually return to their ancient home.

Lurtz always has his eyes on the prize

Most of the main characters in Peter Jackson’s films are from Tolkien’s original text. Sure, some of them are completely rewritten for the cinematic narrative, but very few are made up out of whole cloth. Lurtz is one of those completely fabricated characters. The uruk-hai captain leads Saruman’s forces in pursuit of the Fellowship of the Ring, and the fella provides a nifty mini-villain for the main characters to defeat in the otherwise villain-less finale of The Fellowship of the Ring.

While we get a few minor scenes with Lurtz earlier in the film, he receives the bulk of his screen time in his final moments. First, he turns Boromir into a living pin cushion, shooting the Gondorian hero with multiple arrows. After that, the orc captain gives Aragorn a run for his money in a kick-ass one-on-one duel. Eventually, though, the Ranger wins out, and Lurtz finds his arm and head removed from his body.

The perfect example of a pure plot device, Lurtz doesn’t have many lines in the film. During his final moments, he doesn’t even say anything at all as he quietly duels multiple members of the Fellowship. However, shortly before his last breath, the uruk-hai can be heard shouting to his own men, «Find the halflings. Find the halflings!» A workaholic to the bitter end, Lurtz can’t take his mind off of his mission, even in his last hour.

Boromir’s final moments will make you tear up

Boromir has one of the best character arcs of any hero in The Lord of the Rings. Heir to the steward of Gondor, he joins the Fellowship of the Ring only to fall to the lure of the One Ring. After attempting to steal it from Frodo, he repents and sacrifices his life by defending Merry and Pippin. Aragorn finds him moments before he takes his final breath, and Boromir is able to fill him in on the fact that he tried to take the Ring and what happened to Merry and Pippin. He also urges Aragorn to go to help his people. The emotional shared moment cuts to the quick, regardless of whether you’re watching or reading the event.

In the movies, Boromir’s last words are heart-rending, as he says, «I would have followed you, my brother, my captain, my king.» The confession that he’d finally accepted Aragorn not as a challenger to power but as his returned king is the perfect way to resolve his previous scorn for the Ranger at the Council of Elrond.

In the books, his final line reads, «Farewell, Aragorn! Go to Minas Tirith and save my people! I have failed.» To which Aragorn replies, «No! You have conquered. Few have gained such a victory. Be at peace! Minas Tirith shall not fall!» The response causes Boromir to smile before he breathes his last.

Haldir makes the most out of his Lord of the Rings role

Haldir of Lothlorien falls under the awkward category of minor book character who was turned into an overly involved movie hero. In the original source material, Haldir helps the Fellowship out as they travel through Lothlorien. He talks quite a bit and even shows up after the whole Mirror of Galadriel incident to help send the travelers on their way down the Great River. After that, we don’t meet him again. Period.

In the movies, though, Peter Jackson apparently decided that the Lothlorien guide was important enough that he needed to play a recurring role — in the film’s climactic battle, no less. As the men of Rohan prepare to fend off Saruman’s hordes, Haldir unexpectedly shows up with a bunch of high-quality archers. In the ensuing battle, Haldir meets an untimely death, and the plot moves on without him all the same.

Just before Haldir’s death, he shouts something inaudible to his retreating men. However, since that’s hardly worthy of «last words» sentiment, we thought it’d be better to highlight his previously spoken words when he arrives at Helm’s Deep. Facing King Théoden, he says, «I bring word from Elrond of Rivendell. ‘An alliance once existed between elves and men. Long ago, we fought and died together. We come to honor that allegiance.'» He follows this up with the perfect one-liner, «We are proud to fight alongside men once more.» There. That’s more like it.

Saruman should be nicer to Wormtongue

Saruman serves as one of the primary antagonists in The Lord of the Rings story. Originally sent to resist Sauron, the White Wizard eventually becomes corrupted and vies for power himself. This leads to his overthrow in The Two Towers and his eventual death at the hands of Gríma Wormtongue (two different ways, no less) in The Return of the King.

In the extended film version, Saruman’s death comes as he stands on top of the Tower of Orthanc in the midst of the drowned, ent-trampled ring of Isengard. He’s arguing with a group of heroes who’ve come to talk with him, and as the scene develops, Wormtongue attacks him from behind, stabs him, and sends him careening off the edge of the tower. Just before he’s killed, Saruman can be heard saying the last words, «You withdraw your guard, and I will tell you where your doom will be decided. I will not be held prisoner here.»

In the books, Saruman survives until the end of The Return of the King, at which point it’s discovered that he’s been masquerading as the troublemaker «Sharkey» as he orchestrates the systematic destruction of the Shire. Defeated at last by Frodo and his hobbit friends, he orders a broken Wormtongue to follow him, saying, «You do what Sharkey says, always, don’t you, Worm? Well, now he says, follow!» Just then, Wormtongue snaps, jumps on his master, and slits his throat.

Gríma Wormtongue goes out with a wimper

Gríma Wormtongue is a sad character. He kicks things off by secretly betraying his king, Théoden, and switching allegiances to the powerful Saruman. This move backfires pretty quickly when Gandalf arrives on the scene, prompting Wormtongue to flee to the White Wizard’s domain at Isengard. There, he serves faithfully yet miserably by his new master’s side.

In the films, he finds his ending early in the extended version of The Return of the King. After stabbing Saruman to death in a fit of rage, the tortuous creature is felled by a swift arrow fired by Legolas. His last word, uttered moments before, is simply, «No,» delivered in response to Saruman’s statement that he will never be free.

In the book The Return of the King, a fed-up Gríma backstabs Saruman again, this time in the Shire. His master had been laying waste to the hobbits’ homeland for months beforehand, until Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, with an army of hobbits at their heels, finally defeat him as the story wraps up. Just before he slits Saruman’s throat and is shot by arrows as a result, the warped and exhausted Wormtongue is accused by his wicked master of murdering Frodo’s cousin, to which he violently hisses, «You told me to; you made me do it.» Those are the hateful last words of a completely broken character.

Théoden’s last words all involve Éowyn

Théoden is already quite old when Gandalf frees him from the spells of his counselor, Gríma. From there, the king of Rohan personally leads his armies to Helm’s Deep, where they win an epic victory by the skin of their teeth. Then, they gather more troops and head to Minas Tirith, where the aged ruler dies in a glorious charge that kicks off the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

It’s none other than the Witch-king himself who kills Théoden in battle. In the movies, his airborne beast lands on the king, whipping him around, horse and all, and sending man and animal flying to their deaths. In the books, it’s specifically explained that «a black dart had pierced [his horse]. The king fell beneath him.»

After Éowyn and Merry defeat the Black Rider together, we get two different sets of final words. In the film The Return of the King, Théoden says goodbye to Éowyn in person, saying, «I go to my fathers in whose mighty company I shall not now feel ashamed.» He then whispers his daughter’s name, dying with his final statement unsaid. In the book, Théoden doesn’t realize that Éowyn is nearby. His final words are spoken to her brother, Éomer, «Hail, king of the Mark! Ride now to victory! Bid Éowyn farewell!» As Aragorn later states of the king, «He was a gentle heart and a great king … and he rose out of the shadows to a last fair morning.»

The Witch-king gets way too cocky for his own good

The Witch-king is a recurring villain throughout the trilogy. He leads the nine Ringwraiths on their deadly hunt for the Ring, stabs Frodo at Weathertop, and leads the massive army that attacks Minas Tirith … and that’s just his activity during the War of the Ring. The dude has a rap sheet that stretches way back before that, including sparking multiple wars and raising all sorts of hell for men, elves, and dwarves throughout the Second and Third Ages.

However, he finally meets his match during the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Doubly overconfident from millennia of success and a prophecy that no living man can kill him, he recklessly gets involved in the fighting, murders King Théoden, and then runs into Éowyn and Merry, who kill him in single combat. In the movie, his last words to Éowyn before Merry surprises him are, «Fool. No man can kill me. Die now.» In the books, his slightly different last words are, «Hinder me? Thou fool. No living man may hinder me!» Epic either way, the entire ending of the Witch-king is one of the highlights of the entire saga.

Gothmog is a guy who loves giving commands

We’ve come, once again, to a character who was dramatically over-dramatized for the films. Gothmog is second-in-command during the siege of Minas Tirith. He’s briefly mentioned in the books and doesn’t have an official «ending» in the source material. However, Peter Jackson decided to turn him into a funky-faced orc who’s high on his own authority and convinced that the age of the orc is about to begin — which, what?

Anyway, his involvement in the films does make him a big enough character to deserve a spot on the list. In The Return of the King, we see him ordering his soldiers around, dodging boulders shot by catapults and finally preparing for the sideswiping charge of the Rohirrim as dawn breaks and hope shines again. Later in the battle, the nasty dude can be seen crawling towards the wounded Éowyn. With his weapon lifted to kill, Aragorn and Gimli arrive in the nick of time and finish him off. In order to nab his last word, you need to back up to just before the Riders of Rohan come crashing into the side of his army. Organizing his soldiery and prepping them for the incoming tidal wave, he shouts, «Fire!» It’s a command that becomes his last on-screen utterance.

Denethor leaves The Lord of the Rings with some fiery last words

The steward of Gondor is an interesting character and one who’s difficult to categorize as hero or villain. He leads Gondor and (in the books, at least) does a decent job prepping for the inevitable onslaught from Mordor. Eventually, though, the steward breaks down under the pressure — not to mention the fear of the incoming king who he doesn’t want to hand power to — and tries to kill himself and his son, Faramir. So, yeah, he’s pretty bad when all’s said and done.

In the movies, Denethor’s final words, uttered as Gandalf and Pippin arrive to save the day, are, «No! You will not take my son from me!» As he loses control of the situation (and begins burning alive on his own pyre), he gazes on his son and quietly says, «Faramir,» before running to his doom.

In the books, Denethor’s last line is directed at Gandalf as he resigns himself to a suicidal end, declaring, «But in this at least thou shalt not defy my will: to rule my own end.» After this, he calls to his servants, «Come hither! Come, if you are not all recreant!» Snatching a torch, he sets the pyre on fire and purposefully lies down to die. As he lies there, he gives one great cry and then perishes amidst the flames.

The Mouth of Sauron might’ve miscalculated a bit

Fans of the Lord of the Rings films must watch the extended editions if they want to get familiar with the character known as the Mouth of Sauron. The renegade is a powerful official in the Dark Lord’s bureaucracy, and he comes out to haggle with the captains of the West when they arrive at the gates of Mordor at the end of The Return of the King. In the books, we don’t hear the last words of this manipulating administrator. However, he doubtless dies or goes into hiding after Sauron’s fall.

In the film, though, he’s proactively beheaded by Aragorn (the second villain to be decapitated by him on this list, we might add) in a questionable act of diplomacy. His last, admittedly provocative words before he’s unceremoniously executed are, «And who is this? Isildur’s heir? It takes more to make a king than a broken elven blade.» Foolish words to speak to a hero who makes a habit of removing his enemies’ heads from their bodies on a regular basis.

Gollum’s last words are precious

Gollum’s last words, or more accurately, last word, is arguably, the most famous line from the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy — at least as far as readers of the books are concerned. The antihero inadvertently saves the day by attacking Frodo Baggins just as he arrives at Mount Doom and chooses to claim the Ring rather than destroy it. Biting off Frodo’s ring finger, Gollum reclaims the overpowered piece of jewelry just in time to slip off the edge and fall to a fiery death.

In the film The Return of the King, his final words are a progression of «yes» and «precious.» These are repeated over and over again in ecstatic joy as he dances in the background before Frodo tackles him off the cliff, and he dies. In the book, Gollum specifically cries out, «Precious, precious, precious! My Precious! O, my Precious!» Then, all on his own and without any help from Frodo, Gollum steps backward just a tad too far and slips to his death. His true «last word» comes out of the depths as he wails «precious» one last time.

Sauron’s fall is an epic conclusion to The Lord of the Rings

Sauron is the antagonist of The Lord of the Rings. Heck, the entire series is named after him. While he doesn’t technically «die,» nor does he have any last words, he has to be included here if only because he’s the one, more than any other character, who truly falls. Whether you’re talking about Peter Jackson’s eyesore (pun intended) falling from a crumbling tower or the more spiritual implication of his defeat in the books, either way, Sauron truly falls low by the end of the story.

How low? In The Return of the King, Gandalf explains what will happen to Sauron after the Ring is destroyed, saying that, «If [the Ring] is destroyed, then [Sauron] will fall; and his fall will be so low that none can foresee his arising ever again,» adding that, «He will lose the best part of the strength that was native to him in his beginning, and all that was made or begun with that power will crumble, and he will be maimed forever, becoming a mere spirit of malice that gnaws itself in the shadows, but cannot again grow or take shape.» While he may not be dead or have formal last words, there’s no doubt that Sauron’s fall is one of the most memorably cataclysmic events in all of modern fantasy.

We’ve got to give Frodo a special mention