Table of Contents

- Is gone an adjective?

- What type of adjective is gone?

- Is gone a noun verb or adjective?

- Is gone a verb?

- What is the main verb of gone?

- What type of speech is gone?

- What form of verb is gone?

- What kind of verb is went?

- What kind of verb is believe?

- Is am a verb or adverb?

- Is had a verb form?

- Why is had a verb?

- Is was happy a verb?

- Is end a noun or verb?

- What kind of noun is the word end?

- What is a verb ending in that is used as a noun?

- What part of speech is only?

- What part of speech is not only?

- What can I say instead of not only?

- Which part of speech is since?

- What part of speech is many?

gone adjective (LEFT)

What type of adjective is gone?

Adjective versus present perfect: “Gone” is originally the past participle of “to go,” but in your example, it’s used as an adjective, meaning “not here” — specifically, someone who was here in the past but has left and is now elsewhere.

Is gone a noun verb or adjective?

As detailed above, ‘gone’ can be a verb, a preposition or an adjective. Preposition usage: You’d better hurry up, it’s gone four o’clock. Adjective usage: The days of my youth are gone. Adjective usage: I’m afraid all the coffee’s gone at the moment.

Is gone a verb?

Gone vs. Went is the past tense of go. Gone is the past participle of go. If you aren’t sure whether to use gone or went, remember that gone always needs an auxiliary verb before it (has, have, had, is, am, are, was, were, be), but went doesn’t. I could have gone to the store yesterday.

What is the main verb of gone?

go

What type of speech is gone?

gone

| part of speech: | verb |

|---|---|

| definition: | past participle of go1. |

| part of speech: | adjective |

| definition 1: | no longer at a particular place; departed. He was here a minute ago, but now he’s gone. antonyms: present similar words: absent |

What form of verb is gone?

“Gone” is the past participle of “go,” and is used to form the past perfect (pluperfect) verb tense.

What kind of verb is went?

Yes, ‘went’ is the preterite (or simple past tense) of the verb ‘to go’. It is an irregular verb. The past participle of ‘to go’ is ‘gone’.

What kind of verb is believe?

believe is a verb, belief is a noun, believable is an adjective:I don’t believe you. Her religious beliefs guide her life.

Is am a verb or adverb?

The definition of am is a verb that is used with the word I as the first person singular version of the verb be. An example of when the word am would be used is when saying you are having dinner.

Is had a verb form?

The verb have has the forms: have, has, having, had. The base form of the verb is have. The present participle is having. The past tense and past participle form is had.

Why is had a verb?

had verb (HAVE) past simple and past participle of have , also used with the past participle of other verbs to form the past perfect: When I was a child I had a dog. No more food please – I’ve had enough. I had heard/I’d heard they were planning to move to Boston.

Is was happy a verb?

“happy” is an adjective that qualifies the noun “reading”. “Happy” cannot be a verb, there’s no verb in that sentence but the verb “have” is implied: I wish you have a happy reading, meaning : “I wish you enjoy your reading.”

Is end a noun or verb?

An end is a conclusion or a last part of a long object. To end is to cease. The word end has many other senses as a verb, noun, and adjective and is used in several idioms.

What kind of noun is the word end?

Final point

What is a verb ending in that is used as a noun?

A gerund is a verbal ending in -ing that functions as a noun.

What part of speech is only?

adjective

What part of speech is not only?

The phrase ‘not only’ is part of a pair that makes up a correlative conjunction.

What can I say instead of not only?

What is another word for not only that?

| and | furthermore |

|---|---|

| moreover | also |

| besides | further |

| in addition | likewise |

| plus | what is more |

Which part of speech is since?

Since is used either as a conjunction (introducing a clause) or as a preposition (introducing a phrase) , or occasionally as an adverb (standing alone).

What part of speech is many?

adverb, determiner, predeterminer, pronoun. UK /ˈmeni/

For those interested in a little info about this site: it’s a side project that I developed while working on Describing Words and Related Words. Both of those projects are based around words, but have much grander goals. I had an idea for a website that simply explains the word types of the words that you search for — just like a dictionary, but focussed on the part of speech of the words. And since I already had a lot of the infrastructure in place from the other two sites, I figured it wouldn’t be too much more work to get this up and running.

The dictionary is based on the amazing Wiktionary project by wikimedia. I initially started with WordNet, but then realised that it was missing many types of words/lemma (determiners, pronouns, abbreviations, and many more). This caused me to investigate the 1913 edition of Websters Dictionary — which is now in the public domain. However, after a day’s work wrangling it into a database I realised that there were far too many errors (especially with the part-of-speech tagging) for it to be viable for Word Type.

Finally, I went back to Wiktionary — which I already knew about, but had been avoiding because it’s not properly structured for parsing. That’s when I stumbled across the UBY project — an amazing project which needs more recognition. The researchers have parsed the whole of Wiktionary and other sources, and compiled everything into a single unified resource. I simply extracted the Wiktionary entries and threw them into this interface! So it took a little more work than expected, but I’m happy I kept at it after the first couple of blunders.

Special thanks to the contributors of the open-source code that was used in this project: the UBY project (mentioned above), @mongodb and express.js.

Currently, this is based on a version of wiktionary which is a few years old. I plan to update it to a newer version soon and that update should bring in a bunch of new word senses for many words (or more accurately, lemma).

-

#1

Hi WR,

I found a similar thread in the topic’s list but I still can’t see any difference between:

E.g. «She has gone» and «She is gone»

I’ve even tried in my english books and dictionaries but I’m still missing the point!

Thanks

Regards

Alessandro

-

#2

She has gone.

Normal use of past tense of the verb go.

Focus of attention on her going.

She is gone.

Unusual, poetic if not archaic, use of gone (participle) as an adjective.

Focus of attention on the fact that she is no longer here.

Did you find this thread?

To be with past participle — I am gone, I am come

-

#3

She has gone.

Normal use of past tense of the verb go.

Focus of attention on her going.She is gone.

Unusual, poetic if not archaic, use of gone (participle) as an adjective.

Focus of attention on the fact that she is no longer here.Did you find this thread?

I’ll have a look now.

Thanks you’re helping me a lot today.

-

#4

She is gone can simply mean that she is dead.

-

#5

I think I should insist that we’re dealing with «she’s gone» as a standalone phrase, without any complements (eg, she’s gone away or she’s gone to the cinema are outside the scope of this post).

In this case, you can’t see any difference in meaning because there is none really. Or maybe one that is ever so subtle.

She is gone = she’s no longer here

She has gone = she has left.

Same result but with a slight shift of emphasis.

I might be more likely to say she has gone, when the subject is she because I’d want to emphasize the fact that she went away, that she left me (if that were the context).

But I’d very naturally say «it is gone» for, eg, a wart I had on my hand that disappeared overnight.

Or I’d actually say it’s gone, but

thinking

it is gone.

-

#6

Yes, there is a difference in meaning.

She has gone means «she went someplace.» The destination usually is either specified or understood.

She is gone means «she isn’t here,» and no destination or new location is specified (at least, not as part of that phrase). Sometimes there is no destination (as with the wart example).

In some contexts they can be used interchangeably. If asked, «Has she left yet?» one could reply either, «She is gone,» or «She has gone.»

«To be gone» with a destination specified is mostly archaic usage (although still used in phrases like «he is gone to Heaven»; religious language usage in general tends to retain archaic forms).

-

#7

I am still not sure hoe to distinguish from had gone, has gone, is gone, will be gone to were gone, especially when each of them is connected with a subordinate sentence. Here are the examples I got.

1. He had gone when I arrived home. —> Should it be: He had gone when I have arrived home. Which is correct? It appears to be that he has already left the house before I got back home.

2. My cell phone is gone, and I can’t find it. —> It just doesn’t sound correct to me. How should I correct it?

3. After I come home, my jeans are gone. —> It just doesn’t sound correct to me. How should I correct it?

4. While they were gone to the shop, help me to wash my car. —> Should it be: helped me to wash my car?

Thank you

-

#8

Your use of is gone or has gone in these examples is okay. I’ve marked other problems.

1. He had gone when I arrived home. —>

He had gone when I have arrived home.

It appears to be that he has already left the house before I got back home.

2. My cell phone is gone, and I can’t find it.

3. After

When I come home, my jeans are gone.

4. While they were gone to the shop, [subject is needed] help me to wash my car.

… my brother helped me to wash my car.

-

#9

thank you for your help, it is very helpful : )

-

#10

Yes, there is a difference in meaning.

She has gone means «she went someplace.» The destination usually is either specified or understood.

She is gone means «she isn’t here,» and no destination or new location is specified (at least, not as part of that phrase). Sometimes there is no destination (as with the wart example).

In some contexts they can be used interchangeably. If asked, «Has she left yet?» one could reply either, «She is gone,» or «She has gone.»

…

In speaking, how common is the contraction «she’s gone» used, in which «she’s» may mean «she is» or «she has» ?

-

#11

Very common. It could mean either, but usually «she has», because we say «she has gone» much more often than we say «she is gone».

-

#12

There is no way of discovering this information; to obtain it we would have to ask, each time we heard it, «What do you mean? Has or is?» Which isn’t practicable.

However, if we assume that the difference is the same as the use of «is gone» and «has gone» which is shown in THIS Ngam. To show the overall use, you can compare that with THIS Ngram which shows the uses of «she is gone,she has gone,she went,she goes»

From the first Ngram, we see «she is gone» declining from 1810 to 1920 — I suspect this is caused by Victorian literature’s decline, which revelled in the death of daughters and wives. «O she is gone! A short life but one that brought much pleasure to all around her…» etc.

-

#13

There is no way of discovering this information; to obtain it we would have to ask, each time we heard it, «What do you mean? Has or is?» Which isn’t practicable.

…

What do you mean by «isn’t practicable»? People don’t really ask or care about whether it is «has or is»? How often would you hear the contraction form as in «she’s gone»?

-

#14

How often would you hear the contraction form as in «she’s gone»?

sun, that’s an impossible question. I’ve already told you it’s very common. What answer do you expect? Three times a day, 47 times a week, 349 times a month, 29,352 times a year?

-

#15

sun, that’s an impossible question. I’ve already told you it’s very common. What answer do you expect? Three times a day, 47 times a week, 349 times a month, 29,352 times a year?

Sorry for not making the question clear. I would expect the answer as two out of ten native speakers probably using it, or one out of ten times when this context comes up.

Last edited: Jun 15, 2013

-

#16

Sun, it is very common. That means most people will use it, and most of those use it most of the time, whenever they say «she’s gone to the shops» or «he’s gone to the pub» or «little Johnnie’s gone to school».

-

#17

In speech, native speakers overwhelmingly use contractions. So you will hear «she’s» instead of «she is» or «she has» almost all of the time.

«She is/has» with a strongly-pronounced «is/has» is the exception, and not the rule, in speech.

Also note that AE uses «She is gone» more often than BE.

-

#18

Yes, there is a difference in meaning.

She has gone means «she went someplace.» The destination usually is either specified or understood.

She is gone means «she isn’t here,» and no destination or new location is specified (at least, not as part of that phrase). Sometimes there is no destination (as with the wart example).

In some contexts they can be used interchangeably. If asked, «Has she left yet?» one could reply either, «She is gone,» or «She has gone.»

«To be gone» with a destination specified is mostly archaic usage (although still used in phrases like «he is gone to Heaven»; religious language usage in general tends to retain archaic forms).

Sun, it is very common. That means most people will use it, and most of those use it most of the time, whenever they say «she’s gone to the shops» or «he’s gone to the pub» or «little Johnnie’s gone to school».

In speech, native speakers overwhelmingly use contractions. So you will hear «she’s» instead of «she is» or «she has» almost all of the time.

«She is/has» with a strongly-pronounced «is/has» is the exception, and not the rule, in speech.

Also note that AE uses «She is gone» more often than BE.

So most of the time native speakers don’t distinguish between «she is gone» and «she has gone» , though these two sentences have subtle different focuses. Is that correct?

-

#19

So most of the time native speakers don’t distinguish between «she is gone» and «she has gone» though these two sentences have subtle different focuses. Is that correct?

That does not logically follow.

Most of the time native speakers pronounce «she is gone» and «she has gone» in exactly the same way. That doesn’t mean that native speakers do not or cannot distinguish «she is gone» and «she has gone.»

«You» and «ewe» both sound the same in speech, but all native speakers know the (very significant) difference between them.

-

#20

…

Most of the time native speakers pronounce «she is gone» and «she has gone» in exactly the same way. That doesn’t mean that native speakers do not or cannot distinguish «she is gone» and «she has gone.»

…

How would you tell the difference if something is heard in exactly the same way?

-

#21

How would you tell the difference if something is heard in exactly the same way?

Context?

Are there not homophones in Chinese?

-

#22

Context?

Are there not homophones in Chinese?

So, it is up to the listener to interpret the sentence based on the context?

Chinese is a totally different language than English. Any language has its own way to avoid ambiguity.

-

#23

So, it is up to the listener to interpret the sentence based on the context?

Yes. That’s the case with all sentences, and (I think) in all languages.

And it shouldn’t be particularly difficult to figure out whether «is» or «has» is intended.

-

#24

Speaking personally, I would never say «she is gone», whereas I might say «she has gone» (although I would very rarely use this uncontracted version in speech). Therefore, when I use the contraction «she’s gone», it can only mean one thing in my case. Because that is how I speak, I would automatically ‘hear’ anyone else’s contraction as meaning «she has gone».

As a matter of interest, would many native speakers use the uncontracted («she is gone») version in modern speech?

-

#26

My belief is that «She is gone» is a vastly American turn of phrase. I’m not surprised that it seems foreign to BE speakers.

«She is gone» means something like «Whatever happened to her, we can never get her back.» Maybe she’s dead; maybe she’s just broken up with you.

-

#27

Hullo, everyone.

«He’s gone» [S + Be + Gone (especially in its contracted form)] means that S is not here at present. Obviously S is not here as a result of having gone away some time before what is the here and now of the interlocutors.

My impression is that this «structure» is alive and well, as is witnessed by the «more complex» forms:

1. How long is he been gone (now)?

2. When you wake up tomorrow morning, I’ll have been gone for at least a couple of hours.

GS

-

#28

Hullo, everyone.

«He’s gone» [S + Be + Gone (especially in its contracted form)] means that S is not here at present. Obviously S is not here as a result of having gone away some time before what is the here and now of the interlocutors.

My impression is that this «structure» is alive and well, as is witnessed by the «more complex» forms:1. How long is he been gone (now)?

2. When you wake up tomorrow morning, I’ll have been gone for at least a couple of hours.GS

As a BE speaker, I have to say that the first of those sounds totally wrong to me, whereas the second is perfectly normal usage, even here in England.

-

#29

«How long is he been gone?» sounds wrong to me, too. I think it’s because it is wrong. It has to be «How long has he been gone?»

-

#30

Hullo, everyone.

«He’s gone» [S + Be + Gone (especially in its contracted form)] means that S is not here at present. Obviously S is not here as a result of having gone away some time before what is the here and now of the interlocutors.

My impression is that this «structure» is alive and well, as is witnessed by the «more complex» forms:1. How long is he been gone (now)?

How long has he been gone?

(But maybe only common in AmE!)

2. When you wake up tomorrow morning, I’ll have been gone for at least a couple of hours.GS

I agree with The Prof: In 1. above the structure of is followed by been gone is not idiomatic English. Question 1 might be asked of a colleague in a collaborating company, at a business meeting for example, when asking about the ousted/departed CEO.

Cross posted…

-

#31

So sorry. Of course what I wrote is wrong: what I meant was «…has been gone», as perhaps can be inferred from the presence of «have» in the more articulated Future Perfect in the second example.

GS

-

#32

How would you tell the difference if something is heard in exactly the same way?

1. Context.

2. Experience.

3. Expectation. If Andygc said «She’s gone,» he (being British) would probably mean «She has gone.» If I heard him say that, though, I (being American) would assume he meant «She is gone,» because I do not say «She has gone.»

-

#33

Scenario: the movie «Nightfall», the most recent in the 007 series, featuring Michael Craig and Xavier Bardem — and superb Lady Judy Dench as «M» — in the leading roles.

(87th minute from the start).

Ex-MI6 agent Silva (Xavier Bardem) manages to escape from the glass cage where he’d been confined and kills a couple of guards for good measure.

James Bond (Michael Craig) arrives on the scene of the killing and sees that Silva has disappeared.

James Bond: «He is gone!».

I believe this to be a precious example for EFL teachers and students and I’m more than glad to share it with all foreros.

Best.

GS

PS I think Craig/Bond speaks British English — and a rather good variety of RP, at that.

-

#34

Yes, «she is gone» suggests she has vanished unexpectedly. It would especially be used of someone who can’t go of their own accord.: «She’s gone down the road»=»she has gone», but «the woman was lying dead on the floor and now she’s gone»=»she is gone».

I think it’s for this reason that we’re more likely to say of an inanimate object «it is gone», than of a human. It suggests a state of being gone, rather than a deliberate movement.

-

#35

Speaking personally, I would never say «she is gone», whereas I might say «she has gone» (although I would very rarely use this uncontracted version in speech). Therefore, when I use the contraction «she’s gone», it can only mean one thing in my case. Because that is how I speak, I would automatically ‘hear’ anyone else’s contraction as meaning «she has gone».

As a matter of interest, would many native speakers use the uncontracted («she is gone») version in modern speech?

…

I think the only time I might say «She is gone.» is when using «gone» as a euphemism for «dead». but I’ve never actually said it.

…

3. Expectation. If Andygc said «She’s gone,» he (being British) would probably mean «She has gone.» If I heard him say that, though, I (being American) would assume he meant «She is gone,» because I do not say «She has gone.»

It’s quite a big deviation in the usage of «she is gone» and «she has gone», isn’t it?

Last edited: Jun 16, 2013

-

#36

1. Context.

2. Experience.

3. Expectation. If Andygc said «She’s gone,» he (being British) would probably mean «She has gone.» If I heard him say that, though, I (being American) would assume he meant «She is gone,» because I do not say «She has gone.»

I hear lots of AmE speakers use «She’s gone (home)» at the end of the work day as a contraction of «She has gone (home already)» — often in response to the question «Where is she?». In that context, no-one wuld interpret it as «She’s dead» In contrast, in a hospital here someone is on the verge of death and a friend arrives asks «How is she?» someone might say «She’s gone» meaning she just died. Context ….

-

#37

Scenario: the movie «Nightfall», the most recent in the 007 series, featuring Michael Craig and Xavier Bardem — and superb Lady Judy Dench as «M» — in the leading roles.

(87th minute from the start).

Ex-MI6 agent Silva (Xavier Bardem) manages to escape from the glass cage where he’d been confined and kills a couple of guards for good measure.

James Bond (Michael Craig) arrives on the scene of the killing and sees that Silva has disappeared.James Bond: «He is gone!».

I believe this to be a precious example for EFL teachers and students and I’m more than glad to share it with all foreros.

Best.

GS

![Smile :) :)]()

PS I think Craig/Bond speaks British English — and a rather good variety of RP, at that.

I don’t have access to the film to check this out for myself, but the question that immediately springs to my mind is, are you absolutely sure that James Bond is saying «He is gone», rather than, «he’s gone»? In my mind, the two would sound almost identical, so are you sure?

Please understand that I am not trying to be awkward here — it’s just that I am having trouble imagining Bond, or indeed any British speaker, using an

uncontracted

«he is gone«, or even «he has gone».

-

#38

Ok. These are my observations on some of the several (unrelated) matters mentioned so far.

1. The form «she is gone» for the present perfect is obsolete except in poetry. Today we would say «she has gone» for the present perfect.

2. In present day English, the word gone in «she is gone» is an adjective describing the person’s state (not their action that achieved that state!). «She is gone» means «she is no longer here», «she has disappeared/vanished/escaped», «she is dead», «she is no longer in a relationship with me» etc.

3. The contraction «she’s gone» can be used for both «she has gone» and «she is gone». In some caes, the context dictates that only one meaning is possible. In everyday use, «she’s gone home» can only mean «she has gone home» (because «she is gone home» is an archaism). «Sir, I just checked her cell and she’s gone!» almost certainly means «she is gone». In other cases, the clues are less blatant. In a few cases, it might be uncertain which meaning is intended, but I’d wager that in those cases guessing the wrong meaning will not cause any great error in understanding.

Last edited: Jun 16, 2013

-

#39

«Sir, I just checked her cell and she’s gone!» almost certainly means she is gone

Not if I had said it! As «she is gone» isn’t something I ever say, it would not have occured to me to interpret it that way. But that must just be me. Either way, I agree with you about guessing the wrong meaning not causing any great error in understanding.

-

#40

As pointed out by skymouse, she is gone = she is no longer here.

I am reminded of the poem about the mother bathing her baby (or Your Baby ‘As Gorn* Dahn** The Plug-‘Ole), which includes the lines:

She was but a moment, but when she looked back

Her baby

was gawn

* and in anguish she cried

‘Oh where is my baby?’ The Angels replied,

‘Your baby has gone down the plug-hole.’

(

http://monologues.co.uk/musichall/Songs-W/When-Mother-Washing-Baby.htm)

* gawn/gorn=gone

** dahn=down

-

#41

One idea coming from the comparison of English with the other two germanic languages, German and Dutch:

In German, we use both «sein» (to be) and «haben» (to have) to form the present perfect tense. «Sein» is used with all verbs that signify a «mutation» (thus they’re called «mutative verben»), meaning a change of their nature or appearance in some way, and also a change of location. «Haben» (to have) is used with all verbs signifying action, and also reflexive verbs. It’s the exact same with Dutch.

So my bet is that sentences like «She is gone» are relicts from the time when all the germanic languages where still more or less the same, and that these sentence constructions emphasize the «mutation» or «change» of somebody or something.

For example: «She has gone» = Emphasis on how she ACTED: «She actually walked away from here, or took a cab, or whatever»

«She is gone» = Emphasis on the fact that she «changed»: «She changed in the peculiar way that she’s not here anymore».

other example: «She has changed» = Emphasis lies more on the process of changing, like «She actively changed her behaviour, her appearance, etc»

«She is changed» = Emphasis lies more on the fact that she is different now, and it’s more or less uncertain if she changed through active behaviour on her part, or if she was influenced by someone or something else.

Notice that the perfect tense with «to be» is similar to the passive present tense. I guess that’s the reason why you nearly never hear it in spoken language.

-

#42

…

Please understand that I am not trying to be awkward here — it’s just that I am having trouble imagining Bond, or indeed any British speaker, using anuncontracted

«he is gone«, or even «he has gone».

What do you mean by «Bond» here?

What you are saying is that British speakers would not use the

uncontracted

«she is gone» or «she has gone«?

-

#43

Why doesn’t the WRF dictionary include «no longer present» as a definition?

gone /ɡɒn/vb

- the past participle of go

adj (usually postpositive)

- ended; past

- lost; ruined (esp in the phrases gone goose or gosling)

- dead or near to death

- spent; consumed; used up

- informal faint or weak

- informal having been pregnant (for a specified time): six months gone

- (usually followed by on) slang in love (with)

-

#44

I presume the format of the dictionary has that meaning under the entry for go (verb) :

to depart: we’ll have to go at eleven

When you have departed, you are no longer present.

-

#45

I presume the format of the dictionary has that meaning under the entry for go (verb) : When you have departed, you are no longer present.

… unless you have returned as many times as you have departed.

At least in AmE, if you have returned after the last time you went, we can still say you have gone, but we would not say you are gone. Saying you are gone is saying you are not present, and several of the figurative meanings of the adjective «gone» are extensions of this basic meaning.

-

#46

…

At least in AmE, if you have returned after the last time you went, we can still say you have gone, …

Is there any example to be given?

-

#47

I presume the format of the dictionary has that meaning under the entry for go (verb) : When you have departed, you are no longer present.

When you (have departed) [verb], you are (no longer present) [adjective].

I would expect the adjective to be defined, as well as the verb.

-

#48

When you (have departed) [verb], you are (no longer present) [adjective].

I would expect the adjective to be defined, as well as the verb.

Hence my conclusion on how the dictionary is formatted

-

#49

How would you tell the difference if something is heard in exactly the same way?

We can tell by the context.

-

#50

Hullo, The Prof.

As often — too often, sometimes — happens with SKY programming on our TV’s, last night they broadcast the 007 movie again, ie for the third time in one week.

I seized the opportunity to watch the famous scene again and I can say that the sentence is «He is gone».

I’ve been in the English-teaching profession for decades now and I think I can perceive the subtle difference in vowel length between /hiz/ and /hiɪz/. Besides, reasonable evidence that Bond/Craig pronounced the latter is given by the English subtitles, which clearly read «He is gone» (my bold, of course).

All the best.

GS

QUESTION: Can we use verb «Go» in passive voice?

Here, in this post, I’ll show that «GO» can be in passive voice by showing an active/passive pair of sentences, where the direct object of «GO» of an active sentence is passivized to create that passive version.

Consider the context of where a family is on a road trip, the parents up front driving, the children in the back. The following two examples use the verbs «went» and «gone» of the verb lexeme «GO»:

-

«They went [twenty-five miles] before they knew it.» <— active

-

«[Twenty-five miles] were gone before they knew it.» <— passive

and compare them to versions that use the verb lexeme «TRAVEL» instead of «GO»:

-

«They traveled [twenty-five miles] before they knew it.» <— active

-

«[Twenty-five miles] were traveled before they knew it.» <— passive

The «GO» versions appear to have meanings similar to their corresponding «TRAVEL» versions: actives #1 with #3, and passives #2 with #4.

Note that the active-voice versions #1 and #3 are transitive; and their direct objects are realized by the noun phrase (NP) «twenty-five miles». That NP becomes the subject in the two passive-voice versions (#2 and #4).

And so, it seems that example #2:

- «[Twenty-five miles] were gone before they knew it.» <— passive

does use «GO» in passive voice.

Note: Some might be wondering if an adjective «gone» is actually being used in example #2 «[Twenty-five miles] were gone before they knew it.» That issue is looked into within the following «LONG VERSION» of this answer post.

——————————————

LONG VERSION:

——————————————

Here, I’ll go into more grammatical depth in a process of finding a passive example of «GO» that isn’t a prepositional passive. This process involves the passivization of the direct object of «GO» of an active clause.

Note: One bugbear of a problem is that there are many adjectives that have the same shape as a past-participle verb. This means that some clauses which appear to have the form of a passive clause might actually be active clauses that use an adjective.

Here are some potential candidates that might be «GO» passives:

-

«It was gone.» <— (Something was no longer here.)

-

«His chore to mow the lawn was gone.» <— (Someone had removed that chore from his list.)

-

«Twenty-five miles were gone before they knew it.» <— (A family is on a road trip.)

There are at least three categories that have the word «gone»:

-

preposition: as a past-participle shaped preposition.

-

adjective: as a past-participle shaped adjective.

-

verb: as a past-participle verb form.

note: A past participle is a verb form (i.e. a verb). It is not an adjective, nor is it a preposition. Though, be aware that it is a common practice to refer to an adjective having a past-participle shape as a «past-participle adjective».

PREPOSITION «gone»:

This is a preposition that is rather limited in usage. Its usage is limited to informal style, and limited to BrE dialects of today’s standard English.

Here’s a related excerpt from the 2002 CGEL, page 611:

The main prepositions that are homonymous with the gerund-participle or past participle forms of verbs are as follows:

- [24] according & T . . . given . . . gone & BrE . . . granted

The symbol ‘&’ indicates that the preposition differs in complementation and/or meaning from current usage of the verb: we have prepositional according to Kim but not verbal *They accorded to Kim, and so on.

Gone differs from given and granted in that the corresponding verb is not understood passively; it is used, in informal style, with expressions of time or age as complement: We stayed until gone midnight («after»); He’s gone 60 («over»).

And that seems to be all that we need to know about the preposition «gone». It probably won’t be mentioned again in the rest of this post.

ADJECTIVE «gone»:

This adjective is a member of the class of past-participle adjectives.

Here’s a related excerpt from the 2002 CGEL, page 541:

Past participles following be have a passive rather than perfect interpretation and (leaving aside cases of semantic specialization as in the drunk example [ He was drunk — f.e.] ) the same normally applies to corresponding adjectives. Thus distressed in [35] denotes a state resulting from being distressed in the passive verbal sense.

There are, however, a few exceptions. Kim is retired, for example, means that Kim is in the state resulting from having retired. Similarly, They are gone means that they are in the state resulting from having gone or departed. [fn 5]

So, the adjective «gone» in their example «They are gone» has a perfect interpretation, not a stative passive one that is usually found with past-participle adjectives.

Notice that their example is similar to example #1:

- «It was gone.» <— (Something was no longer here.)

And so, the word «gone» in example #1 is probably an adjective (just as it was in CGEL‘s example They are gone).

Also, here’s their footnote 5 on page 541:

The adjective gone also has various specialized meanings in informal style, including «pregnant» (cf. She’s five months gone) and «infatuated» (cf. He’s quite gone on her).

A verbal passive can have either a dynamic or a stative interpretation. And often it can be difficult to figure out whether a clause is a verbal passive clause with a stative interpretation, or an active clause with a past-participle adjective (adjectival passive). Many times a clause can be ambiguous as to interpretation, where it is understood that the clause can support both interpretations.

There are a handful of grammar tests that are often used to provide evidence w.r.t. a verbal passive versus an adjectival passive (adjective). Many times these tests can be helpful. But many times it can still be unclear. And many times a clause can be considered to be ambiguous.

But the adjective «gone» is unusual for a past-participle adjective, because it doesn’t have a stative passive interpretation. Rather, it has a perfect interpretation. Because of this, it might be easier to differentiate verbal passive clauses from clauses that use the adjective. But we shall see.

VERB «gone»:

The rest of this post will mostly deal with the verb «gone»: though, the adjective «gone» will be important in the discussion here too.

Differentiating between a past-participle verb and a past-participle adjective can often involve that bugbear of an issue: verbal passive versus adjectival passive. A verbal passive clause can often have either a dynamic interpretation or a stative interpretation. But a clause using an adjectival passive can only have a stative interpretation (w.r.t. that adjective). And so this means, that just because a clause has a stative interpretation, that does not rule out the possibility of the clause being a passive.

But since the adjective «gone» has a perfect interpretation, not a stative passive interpretation, then, hopefully that’ll make things easier in attempting to differentiate the verb from the adjective.

Now, let’s look at example #3:

- «Twenty-five miles were gone before they knew it.» <— (A family is on a road trip.)

Its subject is the expression «twenty-five miles», which is a measure phrase NP. A measure phrase NP can often easily function as a subject or object of a clause.

In example #3, the word «gone» has a verbal interpretation similar to that of the verb «traveled» in the passive «Twenty-five miles were traveled before they (even) knew it.» Let’s look at that «traveled» passive and its corresponding active:

-

A. «They traveled [twenty-five miles] before they knew it.» <— active

-

B. «[Twenty-five miles] were traveled before they knew it.» <— passive

and compare them to the versions that use «GO» instead of the verb «TRAVEL»:

-

C. «They went [twenty-five miles] before they knew it.» <— active

-

D. «[Twenty-five miles] were gone before they knew it.» <— passive? (same as #3)

The «GO» versions appear to have the same meanings as their corresponding «TRAVEL» versions: active #A with #C, and passive #B with #D.

This supports the argument that the verb («went») in #C and the word («gone») in #D are also both verbs, just like how the verbs («traveled») in #A and #B are both verbs. Since #C («went») is in active voice, then #D («gone») would then be in passive voice and that means that the word «gone» would be the past-participle verb «gone».

In other words: since example #3 has an active/passive pair with corresponding meanings (#C and #D), it seems that the word «gone» in example #3 can be interpreted as a verb, and so, it is reasonable to consider example #3 as a verbal passive.

Note that the active-voice clause version #C is transitive; and its direct object is that NP «twenty-five miles». That seems to be rather straightforward, especially since the direct object can be easily passivized (as is seen in the passive version #D).

CONCLUSION: I think this post has provided sufficient evidence to show that example #3 at the top of this post could be seen to be a verbal passive:

- «Twenty-five miles were gone before they knew it.» <— (A family is on a road trip.)

In that example, the word «gone» has a verbal interpretation similar to that of the verb «traveled» in the passive «Twenty-five miles were traveled before they (even) knew it.»

And so, it does seem that the verb «GO» can be used in passive voice, where its subject is the passivized direct object of a corresponding active voice version (an active: «They went twenty-five miles before they knew it»).

But perhaps a counter-argument to all this could be that example #3 is similar in structure to: «They were gone», which uses an adjective «gone». Consider:

- The family had just begun a long road trip. To keep themselves entertained, the children played Punch Bug. One mile was traveled, then two. The children were getting quite loud. They were gleefully punching away on each other’s arms. Before the children knew it, twenty-five miles were gone. They were gone because the children had been kept occupied.

The first «gone» has the meaning of the verbal «traveled»; and so, it is the verb «gone» and is in a passive clause. The second «gone» seems to be an adjective «gone»; but its sentence doesn’t (?) seem to work here in this context. Its subject NP «They» seems to be trying to use the previous «twenty-five miles» as its antecedent, and trying to describe its referent as being in a state that had resulted after having gone or departed. But that adjectival use of «gone» doesn’t seem to work here.

And so, er, . . .

ASIDE: This post has also shown that «GO» can head a transitive clause:

- «They went [twenty-five miles] before they knew it.»

with the measure phrase NP «twenty-five miles» as its direct object.

EXTRA STUFF:

Let’s look at example #2:

- «His chore to mow the lawn was gone.» <— (Someone had removed that chore from his list.)

It means that that specific chore was removed from a list of chores; that is, that someone had removed or deleted that chore from the list. An active voice sentence that somewhat corresponds to example #2 could be something like «Someone [ removed / deleted / *went ] his chore to mow the lawn from his list.» (Note that «went» doesn’t work in that last example.)

But in a way, it seems that that item (chore) has metaphorically taken itself off his list of chores (and it did this by itself or with outside assistance); that is, that item is now in the state resulting from having departed, or having left, the list. And so, example #2 seems to be in active voice that is using an adjective «gone».

In other words, the word «gone» in example #2 is probably an adjective. It seems similar to «It was gone»—which is using the adjective «gone» to describe the state that a referent (corresponding to «It») is in after having gone or having departed.

Perhaps seeing a measure phrase NP functioning as a clausal direct object or subject might seem to be a bit unusual. But NPs that function as direct objects, w.r.t. syntax, might often seem to be a bit unusual in various constructions.

Consider the cognate object:

-

He grinned a wicked grin.

-

She always dreams the same dream.

Sometimes the active voice might not have an acceptable passive: A wicked grin was grinned, which would probably be unacceptable in the usual normal contexts. Anyway, the NP «a wicked grin» is a rather unusual object.

Consider object of conveyed reaction:

- She smiled her assent.

For this specific example, the NP «her assent» cannot be passivized: *Her assent was smiled, which is ungrammatical.

note: The above examples were borrowed from the 2002 CGEL, page 305.

The verb «GO» is a rather unusual verb, in that it has many different uses. Consider: «Tom will be going to town soon», «Sue went and told the teacher». And because «GO» is rather unusual, that would probably make any analysis a bit more difficult, perhaps.

NOTE: The 2002 CGEL is the 2002 reference grammar by Huddleston and Pullum (et al.), The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.

What is an adjective?

An adjective is a word that describes something (a noun).

An adjective gives us more information about a person or thing.

Correct order of adjectives

Adjectives sometimes appear after the verb To Be (CARD – LINK TO VIDEO)

The order is To Be + Adjective.

- He is tall.

- She is happy.

Adjectives sometimes appear before a noun.

The order is Adjective + Noun.

- Slow car

- Brown hat

BUT… Sometimes you want to use more than one adjective to describe something (or someone).

What happens if a hat is both brown AND old?

Do we say… an old brown hat OR a brown old hat?

An old brown hat is correct because a certain order for adjectives is expected.

A brown old hat sounds incorrect or not natural.

So what is the correct order of adjectives before a noun?

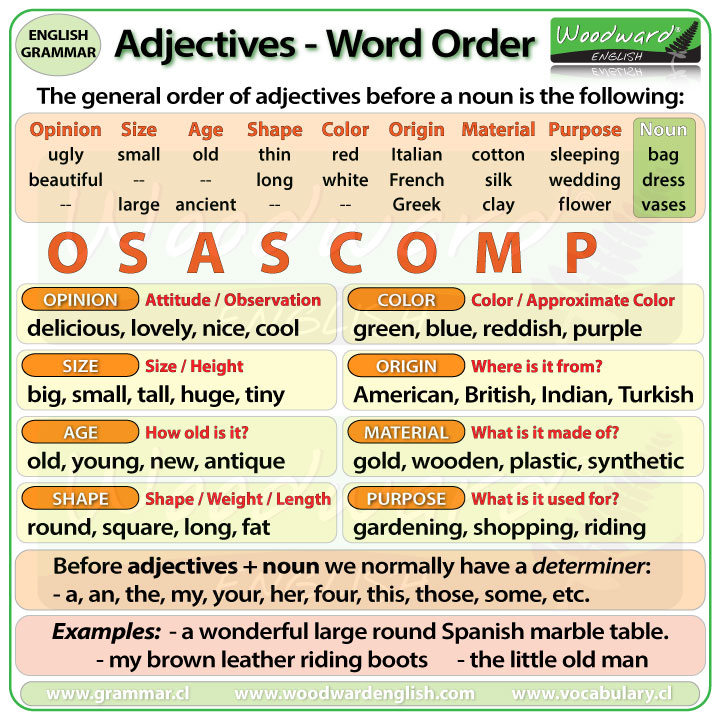

The order of adjectives before a noun is usually the following:

Opinion – Size – Age – Shape – Color – Origin – Material – Purpose

If we take the first letter of each one, it creates OSASCOMP which is an easy way to remember the order.

Let’s look at an example about describing a bag.

- It is an ugly small old thin red Italian cotton sleeping bag

It is not common to have so many adjectives before a noun, but I do this so you can see the correct order of adjectives.

Ugly is an opinion, small is a size, old refers to age, thin refers to shape, red is a color, Italian refers to its origin, cotton refers to the material the bag is made of, sleeping is the purpose of the bag.

I will go into more details about each of these categories in a moment. First, let’s see two more examples:

- A beautiful long white French silk wedding dress.

- Large ancient Greek clay flower vases.

Let’s study the first one.

Here we have a dress. Dress is a noun, the name of a thing. Let’s describe this dress.

What type of dress is it? What is the purpose of this dress?

It is used for weddings so it is…

- a wedding dress.

Let’s image the dress is made of silk. It isn’t made of plastic or gold, it is made of silk.

Silk is a material so it goes before the purpose. We say it is:

- a silk wedding dress.

Now, this dress was made in France. France is a noun, its adjective is French.

Its origin is French. Its origin, French, goes before the material, Silk. So we say it is:

- a French silk wedding dress.

Let’s add the color of the dress. What color is it? White. Color goes before Origin so we say it is:

- a white French silk wedding dress.

What is the shape of this dress? Is it long or short? It is long. The adjective Long goes under the category of shape because shape also covers weight or length. (We will see more about this in a moment) We now say it is:

- a long white French silk wedding dress.

Let’s add one more adjective. Is the dress beautiful or ugly? Well, you should always say it is beautiful or it will ruin her wedding day.

Beautiful is an opinion and adjectives about opinions go before all the other adjectives. So our final description of the dress is:

- a beautiful long white French silk wedding dress.

Now of course we don’t normally add so many adjectives before a noun. This example is just to show you the order of adjectives.

The order is NOT fixed

IMPORTANT: The order of adjectives before a noun is NOT 100% FIXED.

This chart is only a guide and is the order that is preferred.

You may see or hear slight variations of the order of adjectives in real life though what appears in the chart is the order that is expected the most.

Now, let’s look at each type of adjective in more detail (with examples)…

Types of Adjectives

OPINION

Opinion: These adjectives explain what we think about something. This is our opinion, attitude or observations that we make. Some people may not agree with you because their opinion may be different. These adjectives almost always come before all other adjectives.

Some examples of adjectives referring to opinion are:

- delicious, lovely, nice, cool, pretty, comfortable, difficult

For example: She is sitting in a comfortable green armchair.

Comfortable is my opinion or observation, the armchair looks comfortable. The armchair is also green.

Here we have two adjectives. The order is comfortable green armchair because Opinion (comfortable) is before Color (green).

SIZE

Size: Adjectives about size tell us how big or small something is.

Some examples of adjectives referring to size are:

- big, small, tall, huge, tiny, large, enormous

For example: a big fat red monster.

Notice how big is first because it refers to size and fat is next because it refers to shape or weight. Then finally we have the color red before the noun.

AGE

Age: Adjectives of age tell us how old someone or something is. How old is it?

Some examples of adjectives referring to age are:

- old, young, new, antique, ancient

For example: a scary old house

Scary is my opinion, old refers to the age of the house. Scary is before old because opinion is before age.

SHAPE

Shape: Also weight and length. These adjectives tell us about the shape of something or how long or short it is. It can also refer to the weight of someone or something.

Some examples of adjectives referring to shape are:

- round, square, long, fat, heavy, oval, skinny, straight

For example: a small round table.

What is the shape of the table? It is round.

What is the size of the table? It is small.

The order is small round table because size is before shape.

COLOR

Color: The color or approximate color of something.

Some examples of adjectives referring to color are:

- green, blue, reddish, purple, pink, orange, red, black, white

(adding ISH at the end makes the color an approximate color, in this case reddish is “approximately red”)

Our example: a long yellow dress.

What is the color of the dress? It is yellow.

The dress is also long. Long which is an adjective of shape or more precisely length, is before an adjective of color.

ORIGIN

Origin: Tells us where something is from or was created.

Some examples of adjectives referring to origin are:

- American, British, Indian, Turkish, Chilean, Australian, Brazilian

Remember, nationalities and places of origin start with a capital letter.

For example: an ancient Egyptian boy.

His origin is Egyptian. Egyptian needs to be with a capital E which is the big E.

Ancient refers to age so it goes before the adjective of origin.

MATERIAL

Material: What is the thing made of or what is it constructed of?

Some examples of adjectives referring to material are:

- gold, wooden, plastic, synthetic, silk, paper, cotton, silver

For example: a beautiful pearl necklace

Pearl is a material. They generally come from oysters.

The necklace is made of what material? It is made of pearls.

The necklace is also beautiful so I put this adjective of opinion before the adjective referring to material.

PURPOSE

Purpose: What is it used for? What is the purpose or use of this thing? Many of these adjectives end in

–ING but not always.

Some examples of adjectives referring to purpose are:

- gardening (as in gardening gloves), shopping (as in shopping bag), riding (as in riding boots)

Our example: a messy computer desk

What is the purpose of the desk? It is a place for my computer, it is designed specifically to use with a computer. It is a computer desk. In this case, the desk is also very messy. Messy is an opinion. Some people think my desk is messy. So, the order is opinion before purpose.

So this is the general order of adjectives in English and you can remember them by the mnemonic OSASCOMP.

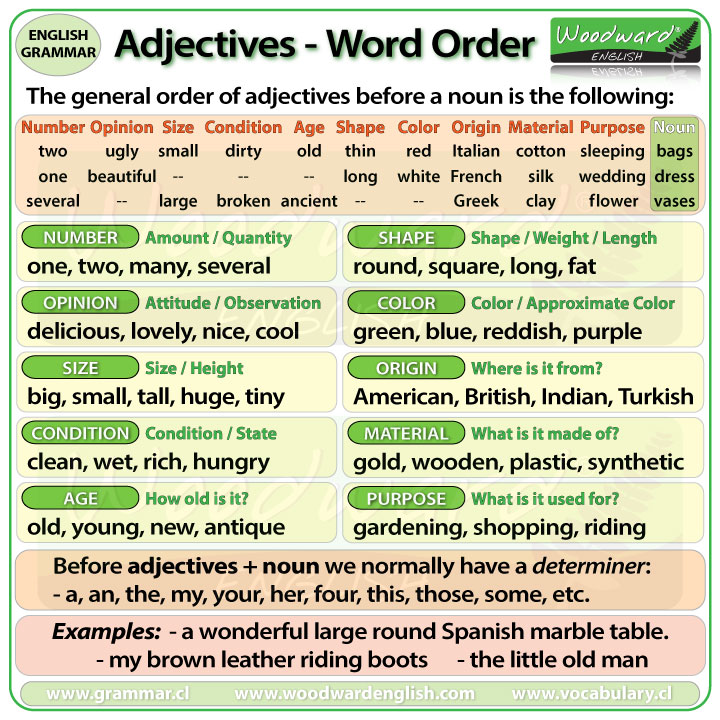

BUT did you know that we could add some extra categories?

BONUS ADJECTIVE GROUPS

We can add the adjective categories of Number and Condition.

NUMBER

Number: Tells us the amount or quantity of something.

It is not only for normal cardinal numbers like, one, two, three… but also other words that refer to quantity such as many or several.

Our examples of adjectives referring to numbers are:

- One, two, three, many, several

For example: three hungry dogs

Number adjectives go before all the other adjectives, including adjectives about opinion.

Hungry is a condition or state so the order is Three hungry dogs.

CONDITION

Condition: Tells us the general condition or state of something

Our examples of adjectives referring to condition or state are:

- Clean, wet, rich, hungry, broken, cold, hot, dirty

For example: Two smelly old shoes.

Smelly is a condition or state. Smelly is before old which refers to age. The number two is at the beginning as numbers always are.

Adjectives – Word Order – Summary Chart

Adjectives Word Order – Practice Quiz

The Adjective is one of the parts of speech that describes some extra information about the noun or a pronoun in a sentence.

The adjective may be present single or multiple in a sentence that presents before a noun or a pronoun. Some articles like (a, an, the) are also called adjectives.

Many adjectives come before nouns or come along with linking verbs like feel, seen, appear, etc. Some adjectives never come before the noun, while some are placed just after the noun.

An adjective also improvises a noun or a pronoun. Some sentences contain more than one adjective. They must be assigned with commas.

Types of adjectives:

There are eight types of an adjective, depending on the place of an adjective in a sentence, meaning, and other illustrations,

- Descriptive Adjective

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Distributive adjective

- Interrogative Adjective

- Numeral Adjective

- Quantitative Adjective

- Proper Adjective

- Possessive Adjective

Descriptive Adjective:

A descriptive adjective is used to illustrate or to give some description of the qualities of a noun or pronoun of a sentence.

The list of adjectives contains more descriptive adjectives, which are also known as qualitative adjectives.

Examples:

- Harley Davidson bikes are stylish, fast, and expensive.

- Here, the words stylish, fast, and expensive provide extra details of the bike, called descriptive adjectives.

- Daniel bought a beautiful flower bouquet to present her gorgeous girlfriend.

- She is very hungry.

- Oxford University has an attractive auditorium.

- He came into the party with an ugly hairstyle.

Demonstrative Adjective:

The demonstrative adjective is used to demonstrate certain things, people, or animals.

This adjective is also telling the position of the noun and comes before other adjectives in the phrase of a sentence to which it is going to modify.

This, these, that, and those are demonstrative adjectives.

Where this and these are used to assign singular and plural nouns that are close to us.

And that and those are used to assign singular and plural nouns that are far from us.

Examples,

- Those pictures were just awesome when we looked at the exhibition.

- Here, the word “those” demonstrates the pictures and tells us that they are far away from their reach.

- Watching these kinds of movies is nothing but wasting time.

- These all are my office colleagues.

- Collect all the fruits and put them on that table.

- These cookies are nicer baked than yesterday’s cookies.

Distributive Adjective:

Distributive Adjectives are generally used to point to a particular group or individual and are used with singular nouns. It is used to modify nouns.

It contains E-type adjectives that are accompanied by nouns or pronouns in a sentence.

- Each, every, neither, and either are four distributive Adjectives.

Examples,

- Each student has to take part in cultural events.

- Here, the word “each” is used to distribute them into single ones.

- There were two washing machines, but neither worked properly.

- I will be happy with either decision.

- Every bogie of a train is filled with coal.

- The monkey divides the piece of bread and gives them to each cat.

Interrogative Adjective:

Interrogative adjectives are adjectives that tend to ask questions or to interrogate nouns or pronouns and to modify them as well in a sentence.

There are three interrogative adjectives, “what, which, and whose,” respectively.

These adjectives no longer function like adjectives if the noun or a pronoun does not present just after these words in a sentence.

Other wh- type or question words can not be considered adjectives because they don’t modify the nouns or pronouns, respectively.

Examples,

- Which bracelets do you like the most?

- Here, “which” becomes an interrogative adjective because it asks to specify the noun “bracelet”.

- What location type are you looking to go to?

- In this question statement, the noun “location” comes after the word “what,” which makes this word an adjective.

- What is the exact location?

- But in this question statement, the noun is absent after the word “what,” which does not make this word an adjective.

- Whose ambition is to become an astronaut?

Numeral Adjective:

A numeral adjective determines the number of nouns present in any sentence.

Numeral Adjectives are of three types:

- Definite Numeral Adjectives(cardinal and ordinal):

- Definite numeral adjectives contain two types, Cardinal numeral adjectives, and ordinal numeral adjectives.

- A cardinal numeral adjective is used to count anything in numbers. (one, two, three, four, etc.)

- The ordinal numeral adjective is used to mention the order or position of anything. (first, second, third, etc.)

- Indefinite Numeral Adjectives:

- Indefinite numeral adjectives are words that witness the presence or absence of anything like some, few, more, many, all, no, etc.

- Distributive Numeral Adjectives:

- The distributive numeral adjectives are such adjectives that are used to distribute like each, neither, either, every, etc.

Examples,

- Mark purchased five Bugatti cars from the showroom. (Cardinal)

- Here, five tells us about the number of cars present.

- The second part of this movie is mind-blowing. (Ordinal)

- Some people can never understand french. (Quantitative)

- All the money you have can never buy happiness. (Indefinite)

- Every living thing needs energy. (distributive)

Quantitative Adjective:

The quantitative adjective is used to explain the noun ( person or thing )and its quantity in a sentence. Sometimes a numeral adjective is also called a quantitative adjective though it specifies the numbers.

The quantitative type of adjective belongs to the question statement category like “how much or how many,” respectively.

- Little, more, much, few, all, large, small, tall, thirty, fifty, etc. are quantitative adjectives.

Examples,

- I want many chocolates to eat. (how much)

- Here, “many” indicates the number of chocolates.

- Among all, some of them are Spanish, a few are Turkish, and the rest are Afrikans. (how many)

- He played the guitar for the very first time. (how many)

- There are 206 bones in a human skeleton. (how many)

- Two boys are seriously injured in an accident. (how many)

Proper Adjective:

A proper adjective is an adjective that gives extra information related to a proper noun of a person, thing, animal, or object.

Though it refers to a particular person of existence and hence needs to be capitalized.

Examples,

- Australian kangaroos are very healthy.

- Here, the word “Australian” represents Australia, which is a proper noun.

- People called them Astronomers who study Astronomy.

- African people are very hard workers.

- I tasted different types of food, but Indian food has the best taste.

- The highest currency in the world is the Kuwaiti Dinar.

Possessive Adjective:

A possessive adjective is an adjective that shows the possessive nature of the noun of a person or place in any sentence.

Possessive adjectives also function like possessive pronouns.

- First-person: My, ours.

- Second-person: Yours.

- Third-person: His, hers, its, their, whose.

Examples,

- My computer is working in better condition.

- Here, “my” belongs to me shows some possession quality.

- Their black Mercedes Benz car looks more attractive than this one.

- Whose father is an Ex-Army man?

- Is this band yours?

- Both sisters have their own cupboards for clothes.

Degrees of Adjectives:

In the English language, An adjective has three degrees to give some extra and detailed information about some nouns or pronouns like person, place, things, objects, or even ideas, respectively.

These degrees are only applicable to descriptive adjectives as it has a tendency to illustrate the qualities of nouns or pronouns.

The three degrees of Adjectives are,

- Positive degree.

- Comparative degree and

- Superlative degree.

For example,

- Hard, harder, hardest.

- Much, more, most.

- Good, better, best.

- Large, larger, largest.

- Beautiful, more beautiful, most beautiful.

- Bad, worse, worst.

- Tall, taller, tallest.

- Thin, thinner, thinnest, etc.

Positive degree:

A positive degree shows a correlation between the adjectives and the adverbs in a normal adjective form.

There is no comparison shown between adjectives and adverbs that are called a positive degree.

Examples,

- She looks pretty in this dress.

- He bought a phone which is thin in size.

- She ordered a large bucket of KFC for the treat.

- The climate is hot today.

- This metal sheet is hard enough to withstand the load we expected.

Comparative degree:

A comparative degree is a degree of adjective that applies to compare two things, either they are of the same origin or different.

It also compares one noun with another noun in a sentence.

Comparative degrees have a suffix -er.

Examples,

- Their goals are faster than our team’s.

- She is more beautiful than her elder sister.

- Today she looks happier than on other days.

- Your handwriting is better than mine.

- This swimming pool is deeper than that one.

Superlative degree:

The superlative degree is an adjective that compares the quality or quantity of any person, place, thing, or object among three or more to show either the least quality or highest degree.

The superlative degree has a suffix -est.

Examples,

- Seedan is one of the bravest men in his battalion.

- Usain Bolt made a world record for the fastest athlete in the Olympics.

- She is the most beautiful girl on our campus.

The formation of adjectives in English is a rather important and interesting topic. Of course, you can speak English at a fairly high level without going into such details, but such information will not be superfluous.

As in Russian, English adjectives can be derived from other parts of speech. These are usually verbs and nouns. Adjectives are formed using suffixes and prefixes. So, first things first.

Prefixes, or prefixes, are added at the beginning of a word and change its meaning. Usually they change the meaning of the adjective to the opposite, negative. A few examples:

There are several prefixes that change the meaning of a word, but without a negative meaning:

There are a lot of varieties of English adjectives formed in the suffix way. As an example, there is a picture with the main suffixes, as well as a few examples of words.

There is also a classification of English adjectives according to the parts of speech from which they are derived. Adjectives can be formed from nouns, verbs, as well as from other adjectives using various suffixes and prefixes, examples of which have already been considered. The very form of the word may also change. For example, the adjective long is formed from the noun length with a change at the root of the word.

Adjectives in English do not change by person, number and case. Qualitative adjectives vary in degree of comparison. As in Russian, there are three degrees of comparison in English: a positive, comparative и excellent

The positive degree is the main form of adjectives that indicates the presence of a given trait or quality.

This is an interesting book. — It’s an interesting book.

The positive degree of adjectives can be used when comparing two or more persons or objects in the following cases:

The comparative degree of adjectives is used to indicate a greater or lesser severity of a sign or quality in one object or person in relation to another.

For monosyllabic adjectives and two-syllable adjectives ending in -e, -y, -er, -ow, the comparative form is formed by adding the suffix -er.

small small — smaller smaller

simple is simple — simpler is simpler

pretty handsome — prettier prettier

narrow narrow — narrower already

The rest of the adjectives form a comparative degree of comparison with the words more more or less less, which is placed before the adjective.

For monosyllabic adjectives and two-syllable adjectives ending in -e, -y, -er, -ow, the superlative is formed by adding the suffix -est.

small small — smallest smallest

simple simple — simplest is the simplest

pretty beautiful — prettiest the most beautiful

narrow narrow — narrowest narrowest

The rest of the adjectives form a superlative degree of comparison with the words most most or least least, which is placed before the adjective.

The exceptions to the general rule of education of the comparative and superlative degree are the forms of the adjectives good good, bad bad, little small, little, much / many many, far distant

Source: http://www.study-languages-online.com/ru/en/english-adjective-comparative.html

Before memorizing a colossal number of adjectives, you need to figure out how adjectives are formed, what are degrees of adjectives in Englishand also know the word order. All this knowledge will help you use English adjectives correctly. Now let’s find out what an adjective is.

An adjective is a part of speech that denotes a feature of an object and answers the question what? What?

Example: beautiful is beautiful, blue is blue, unpredictable is unpredictable.

1) Simple (simple) — adjectives that have no prefixes or suffixes.

Example: black-white- black-and-white, cold-hearted- heartless, well-known- known

a) Suffix education. Adjective suffixes include:

b) Prefix method. Almost all prefixes that are added to adjectives have a negative meaning:

Sometimes we use two or more adjectives together. For example:

There is a small, brown, round table in the room — there is a small, brown, round table in the room.

In this sentence, the English adjectives small, brown, round are actual adjectives that give objective information about the size, color, shape of an object.

Example: The big, old, round, brown, German, wooden wardrobe.

Source: http://enjoyeng.ru/grammatika/prilagatelnyie-v-angliyskom-yazyike-the-adjective

Different postfixes bring different nuances to the semantics of the formed adjectives. Shaping elements –ible / -able indicate the presence of a certain ability to perform an action, the other postfixes indicated below contain an indication of certain properties, qualities, for example:

Postfixes -ible / -able can be a bit tricky when you start learning English. There are significantly more adjectives with –able in English. When derivative adjectives are formed using these postfixes, the original stems can undergo certain changes, namely:

— receive — receivable: the final vowel «-e» of the original stem before the above suffixes is dropped; — rely — reliable: the final vowel «Y» of the stem, when adding these postfixes, turns into «i», and only the derivational postfix -able can be used after it;

— appreciate (highly appreciate, feel, recognize) — appreciable (tangible, significant, significant): after the final «i» in the original stem, only the postfix «-able» can be added.

In the described way, adjectives are formed using the postfixes -al, -ful, -y, which emphasize the presence of any certain qualities or properties, the postfix -less, indicating the absence of certain properties or qualities, the postfix -ous, characterizing certain character traits or giving corresponding quality characteristics, and a number of others, for example:

A feature of English derivative adjectives is the fact that the prefixes involved in their formation for the most part contain a negative meaning. Examples of such prefixes are un-, in-, im-, dis-. There are, of course, prefixes with other meanings:

- visible (visible) — invisible (invisible)

- correct (correct, correct, exact) — incorrect (incorrect, incorrect, inaccurate)

- dead (dead) — undead (raised from the dead)

- reasonable (reasonable, reasonable, reasonable) — unreasonable (unreasonable, unreasonable, unreasonable)

- legal (lawful, legal, legal) — illegal (illegal, illegal, illegal)

- local (local, local) — illocal (non-local, non-local)

- practical — impractical (impractical, unrealistic, practically impractical, unusable

Source: https://online-teacher.ru/blog/obrazovanie-prilagatelnyx-english

English Adjectives — Sentence Order and Comparison

An adjective in English is a part of speech that answers the questions: «what?», «What?», «What?», «What?» and denoting a sign of an object. An adjective describes an object or object in terms of color, shape, quality, size, character, origin, and properties.

The main difference between adjectives in the English language is that they do not change forms and endings in different cases, numbers, do not differ when describing nouns of different kinds. Coordination with other words occurs without changing the word form.

Qualitive and relative adjectives

There are two types of adjectives in English:

Qualitative — describe the color, shape, size, taste of the object: beautiful, weak, green, powerful, square, happy;

Relative — describe the origin of the object, what it is made of: wooden, stone, clay, cherry, grape, glass (wooden, stone, clay, cherry, grape, glass). Such adjectives do not have degrees of comparison.

Degrees of comparison of adjectives

Adjectives have three degrees of comparison: positive (initial), comparative, and excellent. The comparative and superlative degrees of quality English adjectives are formed according to special rules, among which there are exceptions that must be remembered.

Comparative degree

The comparative degree of short adjectives consisting of two or fewer syllables is formed by adding the suffix «-er» to the end of the word:

If a short English adjective ends in a closed syllable (from the end — a consonant, vowel, consonant), the last letter is doubled, and only then the suffix «-er» is added:

If a short adjective ends in a consonant + «y», the last letter «y» is changed to «i» and «-er» is added:

If the short word ends in «-e», add «-r»:

The comparative degree of long adjectives consisting of 3 or more syllables is formed using the word «more»:

Superlative degree

To form the superlative of a short adjective, it is necessary to put the definite article and add the suffix «-est»:

The superlong adjective is formed by adding «the most»:

Comparative and superlative exceptions

These English adjectives form a comparative and superlative degree not according to the rules, completely or partially changing the basis of the word.

- good — better — the best (good — better — best);

- bad — worse — the worst (bad — worse — the worst);

- little — less — the least;

- much (with uncountable) / many (with countable) — more — the most (many — more — most);

- far — farther / further — the farthest / the furthest

- old — older / elder — the oldest / the eldest.

“Father” and “further” differ in that the first word implies distances (go farther — go further), the second — has a figurative meaning (watch the film further — see the film further).

«Older» and «elder» differ in meaning: the first word describes age in the literal sense (the piece of furniture is older), the second is used for age relations in the family (my elder brother is my older brother).

There are words, the comparative and superlative degrees of which can be formed in both ways:

clever (smart) — cleverer (smarter) — the cleverest (the smartest)

clever — cleverer — the most clever

polite (polite) — politer — the politest

polite — politer — the most polite

friendly — friendlier — the friendliest

friendly — more friendly — the most friendly

They also include:

common, cruel, gentle, narrow, pleasant, shallow, simple, stupid, quiet.

Comparative expressions using adjectives in sentences

- twice as as — twice as;

- three times as as — three times than;

- half as as — half of something (twice)

- the same as — the same as;

- less than — less than;

- the least / most of all — least / most of all;

- the, the — what, so;

- than — what.

Your bag is twice as heavy as mine. “Your bag is twice the size of mine.

Mary’s copybook costs half as little as ours. — Mary’s notebook costs half ours.

Your dream is the same as important as theirs. “Your dream is as important as theirs.

This flower is less beautiful than that one growing in the garden. “This flower is less beautiful than the one that grows in the garden.

The more careful you are, the easier it is. “The more careful you are, the easier it will be to deal with it.

This exercise is the least difficult of all. — This exercise is the least difficult of all.

Source: https://englishbro.ru/grammar/adjectives-common-rules

Formation of degrees of comparison of adjectives in English

Comparison of adjectives in English is one of the simplest grammatical topics. The reason is that the existing degrees of comparison and methods of their formation largely coincide with those in the Russian language. As in Russian, there are two degrees of comparison in English: comparative и excellent… According to another classification, there is also a positive one — this is the usual form of adjectives.

Comparative forms in English

How the degrees of comparison are formed

There are two ways to form the degrees of comparison: analytical (adding words) and synthetic (adding suffixes). The choice of the desired method of formation depends on the adjectives themselves:

- for monosyllabic (simple) — we use the synthetic method of education

- for the polysyllabic — the analytical method.

Let’s consider all this in detail, giving examples.

Monosyllabic adjectives and the synthetic method for comparing them

Almost all simple adjectives in English form comparative degrees using suffixes:

table of adjectives

There are several cases where adding suffixes requires minor changes to the word itself:

- If in a monosyllabic adjective there is a short vowel before the final consonant, then we double it:

- Big — bigger — the biggest

- The final dumb -e goes off before -er, -est:

- Nice — nicer — the nicest

- The final –y is replaced with –i, provided that there is a consonant before –y:

If there is a vowel before -y in a word, there will be no substitutions:

- Gray — greyer — the greyest

Let’s sum up.

In the following picture, you will see an extremely simple diagram of the formation of the degrees of comparison of simple adjectives in English.

the degree of comparison of simple adjectives in English

There are no rules that have no exceptions

There is a small list of exceptions to the general rule: these words completely change their roots:

exclusion list

There is another type of exception, which is a small list of words that have two possible options for the formation of degrees, each of which has its own semantic characteristics. You need to know them in order to use them correctly in the context:

Adjectives with two possible options for the formation of degrees

As for two-syllable adjectives, some of them form their comparative forms as monosyllabic — by adding —er and —is… These include those who

- Ends in:

narrow — narrower — the narrowest

Source: https://englishfull.ru/grammatika/sravnenie-prilagatelnih.html

10 ways to tell an adjective from an adverb in English

An adjective is easy to recognize in a sentence by how it affects the noun, changing its properties. For example:

«He bought a shirt.» The word shirt is a noun, but it is not clear what kind of shirt it is. All we know is that someone bought a shirt.

«He bought a beautiful shirt.» In this example, the adjective beautiful appears, which changes the noun shirt, which makes it clear which shirt the person bought.

It is not difficult to recognize an adjective in a sentence — it, as a rule, answers the questions “Which one?”, “Which one?”, “Which one?”.

For example:

“The kind woman gave us a tasty cake.” What woman? Kind (kind). What kind of cake? Tasty

«The small boy is playing with a new toy.» The adjectives small (small) and new (new) tell us which boy and what kind of toy we are talking about.

So, the main thing to remember is the questions that the adjective answers in English:

- What is it?

- Which the?

- Which one?

Adverb