Word-building in

English, major means of WB in English:

a) affixation;

b) conversion;

c) composition; types

of compounds.

WB

is the process of creating new words in a language with the help of

its inner sources.

Two

types of WB proper :

-

Word derivation when 1 stem undergoes different changes;

-

Word composition when 2 or more stems are put together.

The most important means of word derivation are:

a) affixation;

b) conversion;

c) composition; types of compounds.

Affixation,

conversion, composition are the most productive or major means of WB

in modern English.

Shortening

occupies the intermediate position between major & “minor” or

less productive & unproductive means of WB.

Minor

means of word-building are:

-

Back formation = reversion;

-

Blending = telescoping;

-

Reduplication = doubling the stem;

-

Sound immitation;

-

Sound interchange;

-

Shift of stress, etc.

Affixation is the most productive means of word-building in English.

Affixation is the formation of new words by adding a derivational

affix to a derivational base.

Affixation is subdivided into:

-

Suffixation

-

Prefixation.

The essential differences between suffixes &

preffixes is that preffixes as a rule only modify the lexical meaning

of a word without changing the part of speech to which the word

belongs

e.g. to tie – to untie

However, some preffixes form new words in a

different part of speech:

e.g. friend – N., to be friend-V., adj.- little., V.-

to be little.

Suffixes do not only modify the lexical meaning of a word but also

form a word belonging to a different part of speech.

Suffixes are usually classified according to the part of speech they

form:

-

Noun-forming suffixes ( to read – reader, dark – darkness);

-

Adjective-forming (power-powerful);

-

Verb-forming ( to organize, to purify);

-

Adverbal-forming (quick-quickly).

Prefixes are usually classified according to their meaning:

-

Negative prefixes (-un; -non; -in; -dis…);

-

Reversative = privative (-un; -de; -dis..);

-

Pejorative (уничижительные)

(mis-; mal- (maltreat-дурно

обращаться); pseudo-); -

Preffixes of time & order (fore-(foretell); pre-(prewar); post-;

ex-(ex-wife); -

Prefixes of repetition (re- rewrite);

-

Locative prefixes (super-; sub-subway; into-; trans –atlantic))

The 2 main criteria, according to which all the affixes are

subdivided are:

1)

origin;

2) productivity.

As to their origin (etymology) affixes are:

-

Native;

-

Borrowed.

Borrowed affixes may be classified according to the source of

borrowing (Greek, Latin, etc.) According to their productivity, i.e.

the ability to build new words at the present time, English affixes

are:

-

Productive or living affixes, used to build new words now;

-

Non-productive = unproductive affixes, not used in the word-building

now, or used very rarely.

Productivity shouldn’t be confused with frequency. What is frequent

may turn out to be non-productive (-some (adj.)-handsome is very

frequent, but not productive).

Some native prefixes still productive in English

are: — fore; -out (grow); over (estimate); -un (able); -up

(bringing); -under, -mis, etc.

Productive foreign prefixes are: -dis (like); -en (close); -re(call);

-super (natural); -pre (war); -non (drinking); -anti (noise).

Native noun-forming suffixes in modern English are: -er (writer);

-ster (youngster), -ness(brightness), etc.

Adjective-forming native suffixes (productive in English) are: -y

(rocky); -ish (Turkish), ful; -ed (cultured); -less (useless), etc.

Foreign productive noun-forming suffixes are: -ee

(employee); -tion (revolution); -ism(Gr., realism); -ist, etc.

Borrowed productive verb-forming suffixes of

Romanic origin are: -ise,ize (organize), -fy, ify (signify).

Prefixation is more typical of adjectives & verbs. Suffixation is

approximately evenly used in all parts of speech.

There are 2 types of semantic relations between affixes:

-

Homonymy;

-

Synonymy.

Homonymous prefixes are: -in: inactive, to inform.

Homonymous suffixes are: -ful1

(adjective-forming), -ful2

(noun-forming-spoonful), -ly1

(adj.-forming-friendly), -ly2

(adverb-forming-quickly).

Some affixes make a chain of synonyms: the native

suffix –er denoting an agent, is synonymous to suffix –ist

(Gr.)-socialist & to suffix –eer – also denoting an agent

(engineer) but often having a derrogatory force (`sonneteer-

стихоплёт, profiteer –

спекулянт, etc.)

Some affixes are polysemantic: the noun-forming suffix –er has

several meanings:

-

An agent or doer of the action –giver, etc.

-

An instrument –boiler, trailer

-

A profession, occupation –driver;

-

An inhabitant of some place –londoner.

b)

Conversion

is one of the most productive word-building means in English. Words,

formed by means of conversion have identical phonetic & graphic

initial forms but belong to different parts of speech (noun –

doctor; verb –to doctor). Conversion

is a process of coining (создание)

a new word in a different part of speech & with different

distribution characteristic but without adding any derivative

elements, so that the basic form of the original & the basic form

of the derived words are homonymous (identical). (Arnold)

The

main reason for the widespread conversion in English is its

analytical character, absence of scarcity of inflections. Conversion

is treated differently in linguistic literature. Some linguists

define conversion as a non-affixal way of word-building (Marchened

defines conversion as the formation of new words with the help of a

zero morpheme, hence the term zero derivation)

Some

American & English linguists define conversioon as a functional

shift from one part of speech to another, viewing conversion as a

purely syntactical process. Accoding to this point of view, a word

may function as 2 or more different parts of speech at the same time,

which is impossible. Professor Smernitsky treats conversion as a

morphological way of word-building. According to him conversion is

the formation of a new word through the changes in its paradigm.

Some

other linguists regard conversion as a morphological syntactical way

of word-building, as it involves both a change of the paradigm &

the alterration of the syntactic function of the word.

But

we shouldn’t overlook the semantic change, in the process of

conversion. All the morphological & syntactical changes, only

accompany the semantic process in conversion. Thus, conversion may be

treated as a semantico-morphologico-syntactical process.

As a word within the conversion pair is

semantically derived from the other there are certain semantic

relationswithin a conversion pair.

De-nominal words (от

глагола) make up the largest group &

display the following semantic relations with the nouns:

-

action characteristic of the thing: -a butcher; to butcher

-

instrumental use of the thing: -a whip; to wheep

-

acquisition of a thing: a coat; to coat

-

deprivation of a thing: skin – to skin.

Deverbal substantives (отглаг.сущ)they

may denote:

-

instance of the action: to move – a move;

-

agent of the action: to switch – a switch;

-

place of the action: to walk- a walk;

-

object or result of the action: to find – a find.

The English vocabulary abounds mostly in verbs,

converted from nouns( or denominal verbs) & nouns, converted from

verbs (deverbal substances): pin –to pin; honeymoon-to honeymoon.

There are also some other cases of conversion: batter-to batter, up –

to up, etc.

c)

Composition is one of the most productive word-building

means in modern English. Composition is the production of a new word

by means of uniting 2 or more stems which occur in the language as

free forms (bluebells, ice-cream).

According

to the type of composition & the linking element, there are

following types of compounds:

-

neutral compounds; (1)

-

morphological compounds; (2)

-

syntactical compounds. (3)

(1)

Compounds built by means of stem junction (juxt – opposition)

without any morpheme as a link, are called neutral compounds. The

subtypes of neutral compounds according to the structure of immediate

constituents:

a)

simple neutral compounds (neutral compounds proper) consisting of 2

elements (2 simple stems): sky –blue;film-star.

b) derived compounds (derivational compounds) –

include at least one derived stem: looking-glass, music-lover,

film-goer, mill-owner derived compounds or derivational should be

distinguished from compound derivatives, formed by means of a suffix,

which reffers to the combination of stems as a whole. Compound

derivatives (сложно-произв.слова)

are the result of 2 acts of word-building composition &

derivation. ( golden-haired, broad-shouldered, honey-mooner,

first-nighter).

c)

contracted compounds which have a shortened stem or a simple stem in

their structure, as “V-day” (victory), G-man (goverment), H-bag

(hand-bag).

d)

compounds, in which at least 1 stem is compound (waterpaper(comp)

–basket(simple))

(2)

Compounds with a specific morpheme as a link (comp-s with a linking

element = morphological compounds). E.g. Anglo-Saxon, Franko-German,

speedometer, statesman, tradespeople, handicraft, handiwork.

(3)

Compounds formed from segments of speech by way of isolating speech

sintagmas are sometimes called syntactic compounds, or compounds with

the linking element(s) represented as a rule by the stems of

form-words (brother-in-law, forget-me-not, good-in-nothing).

II.

Compounds may be classified according to a part of speech they belong

& within each part of speech according to their structural

pattern (structural types of compound-nouns):

-

compounds nouns formed of an adjectival stem + a noun stem A+N.

e.g.blackberry, gold fish

-

compound nouns formed of a noun-stem +a noun stem N+N

e.g. waterfall, backbone, homestead, calhurd

III.

Semantically compounds may be: idiomatic (non-motivated),

non-idiomatic

(motivated).

The compounds whose meanings can be derived from the meanings of

their component stems, are called non-idiomatic, e.g. classroom,

handcuff, handbag, smoking-car.

The

compounds whose meanings cannot be derived from the meanings of their

component stems are called idiomatic, e.g. lady-bird, man of war,

mother-of-pearls.

The

critiria applied for distinguishing compounds from word combinations

are:

-

graphic;

-

phonetic;

-

grammatical (morphological, syntactic);

-

semantic.

The graphic criteria can be relied on when

compounds are spelled either sollidly, or with or with a hyphen, but

it fails when the compound is spelled as 2 separate words,

e.g.

blood(-)vessel

(крово-сосудистый)

The phonetic criterium is applied to comp-s which

have either a high stress on the first component as in “hothead”

(буйная голова),

or a double stress “ `washing-ma`chine”, but it’s useless when

a compound has a level stress on both components, as in “

`arm-chair, `ice-cream” etc.

If we apply morphological & syntactical

criterium, we’ll see that compounds consisting of stems, possess

their structural integrity. The components of a compound are

grammatically invariable. No word can be inserted between the

components, while the components of a word-group, being independant

words, have the opposite features (tall-boy(высокий

комод), tall boy (taller&

cleverer,tallest)).

One of the most reliable criteria is the semantic

one. Compounds generally possess the higher degree of semantic

cohesion (слияние) of its elements

than word-groups. Compounds usually convey (передавать)

1 concep. (compare: a tall boy – 2 concepts, & a tallboy – 1

concept). In most cases only a combination of different criteria can

serve to distinguish a compound word from a word combination.

CONVERSION. COMPOSITION Lecture 4

CONVERSION Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech; the morphemic shape of the original word remains unchanged. The new word acquires a meaning, which differs from that of the original one though it can be easily associated with it. The converted word acquires a new paradigm and a new syntactic function, which is peculiar to its new category as a part of speech.

I took a taxi. They taxied to the station. They ran in and out. He knows the ins and outs of our town. He went home then. The then word will be mad they say. Two noes make a yes. I will take no no for an answer. She mothered Betty to the point of hysteria. We tea at four. There is a constant struggle between the haves and the have-nots. But me no buts if me no ifs.

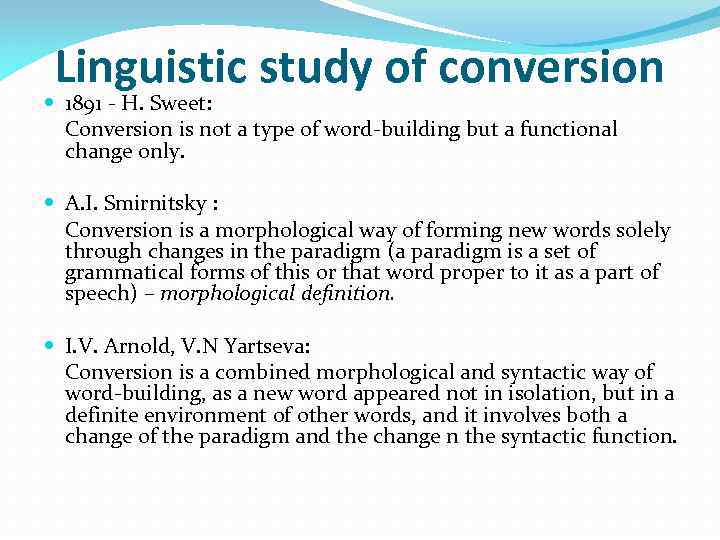

Linguistic study of conversion 1891 — H. Sweet: Conversion is not a type of word-building but a functional change only. A. I. Smirnitsky : Conversion is a morphological way of forming new words solely through changes in the paradigm (a paradigm is a set of grammatical forms of this or that word proper to it as a part of speech) – morphological definition. I. V. Arnold, V. N Yartseva: Conversion is a combined morphological and syntactic way of word-building, as a new word appeared not in isolation, but in a definite environment of other words, and it involves both a change of the paradigm and the change n the syntactic function.

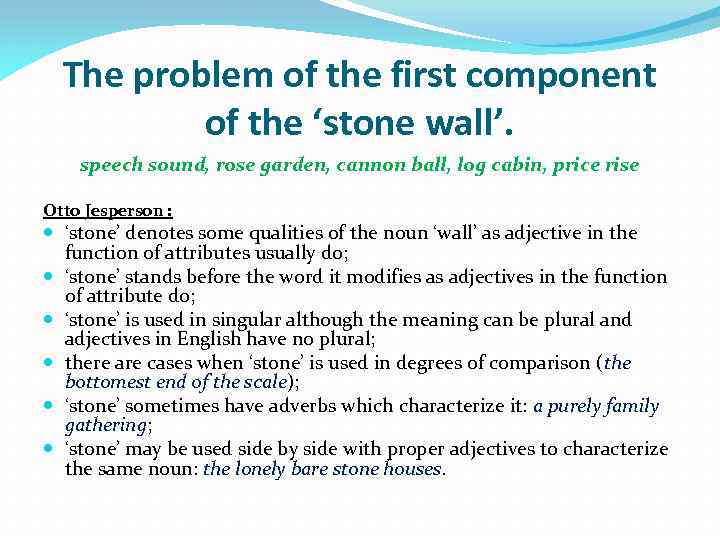

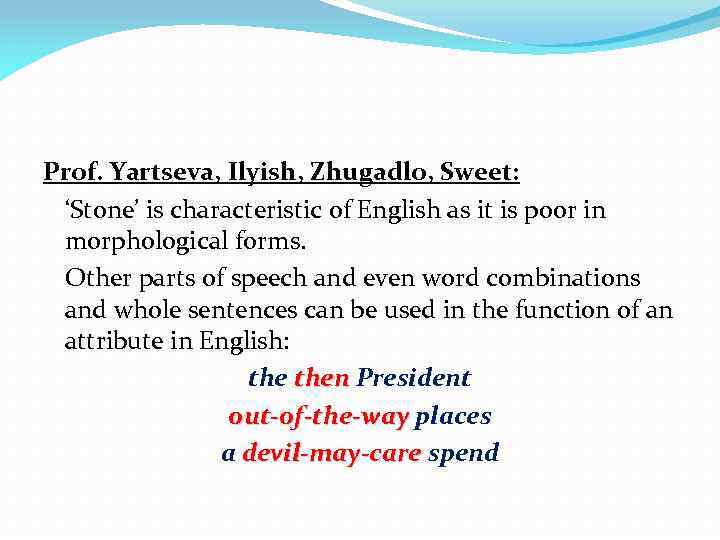

The problem of the first component of the ‘stone wall’. speech sound, rose garden, cannon ball, log cabin, price rise Otto Jesperson : ‘stone’ denotes some qualities of the noun ‘wall’ as adjective in the function of attributes usually do; ‘stone’ stands before the word it modifies as adjectives in the function of attribute do; ‘stone’ is used in singular although the meaning can be plural and adjectives in English have no plural; there are cases when ‘stone’ is used in degrees of comparison (the bottomest end of the scale); ‘stone’ sometimes have adverbs which characterize it: a purely family gathering; ‘stone’ may be used side by side with proper adjectives to characterize the same noun: the lonely bare stone houses.

Prof. Yartseva, Ilyish, Zhugadlo, Sweet: ‘Stone’ is characteristic of English as it is poor in morphological forms. Other parts of speech and even word combinations and whole sentences can be used in the function of an attribute in English: then President out-of-the-way places a devil-may-care spend

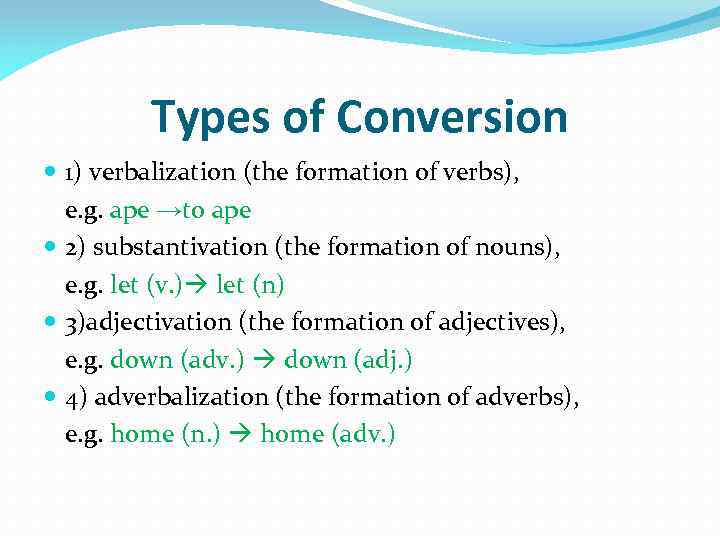

Types of Conversion 1) verbalization (the formation of verbs), e. g. ape →to ape 2) substantivation (the formation of nouns), e. g. let (v. ) let (n) 3)adjectivation (the formation of adjectives), e. g. down (adv. ) down (adj. ) 4) adverbalization (the formation of adverbs), e. g. home (n. ) home (adv. )

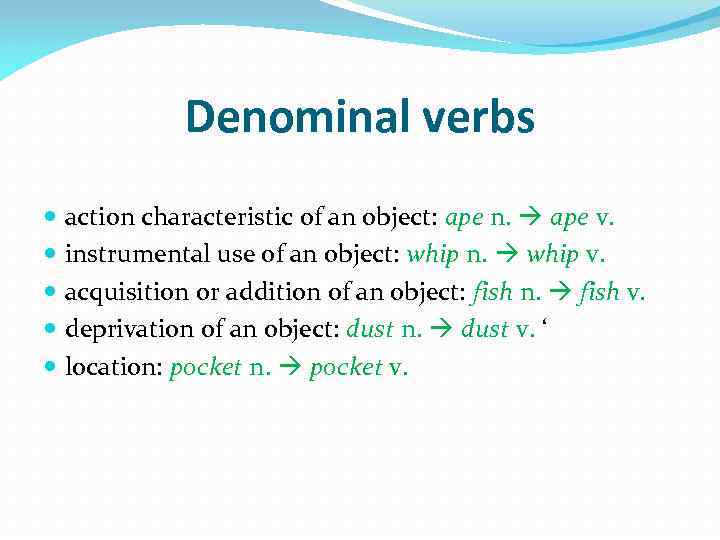

Denominal verbs action characteristic of an object: ape n. ape v. instrumental use of an object: whip n. whip v. acquisition or addition of an object: fish n. fish v. deprivation of an object: dust n. dust v. ‘ location: pocket n. pocket v.

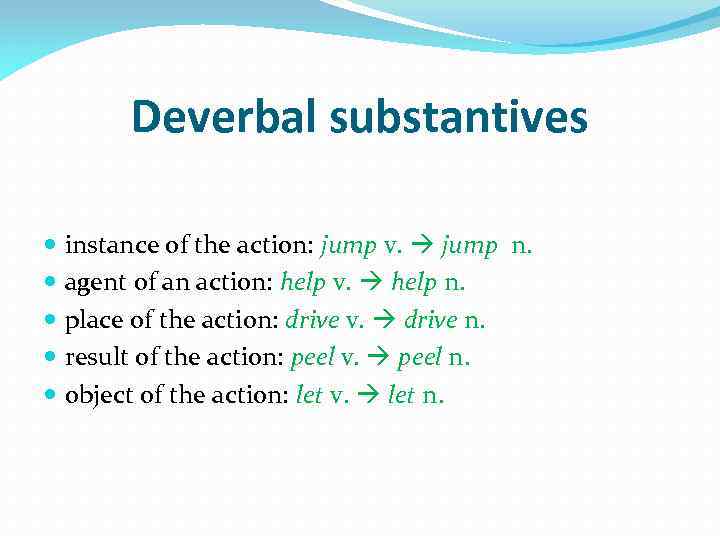

Deverbal substantives instance of the action: jump v. jump n. agent of an action: help v. help n. place of the action: drive v. drive n. result of the action: peel v. peel n. object of the action: let v. let n.

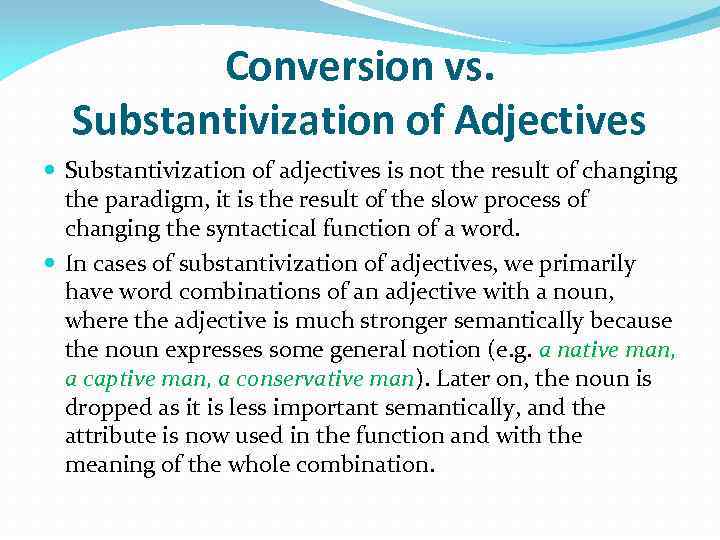

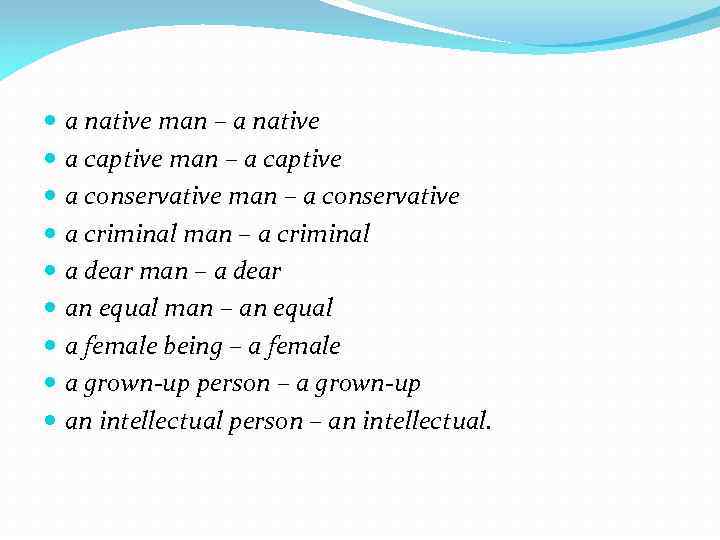

Conversion vs. Substantivization of Adjectives Substantivization of adjectives is not the result of changing the paradigm, it is the result of the slow process of changing the syntactical function of a word. In cases of substantivization of adjectives, we primarily have word combinations of an adjective with a noun, where the adjective is much stronger semantically because the noun expresses some general notion (e. g. a native man, a captive man, a conservative man). Later on, the noun is dropped as it is less important semantically, and the attribute is now used in the function and with the meaning of the whole combination.

a native man – a native a captive man – a captive a conservative man – a conservative a criminal man – a criminal a dear man – a dear an equal man – an equal a female being – a female a grown-up person – a grown-up an intellectual person – an intellectual.

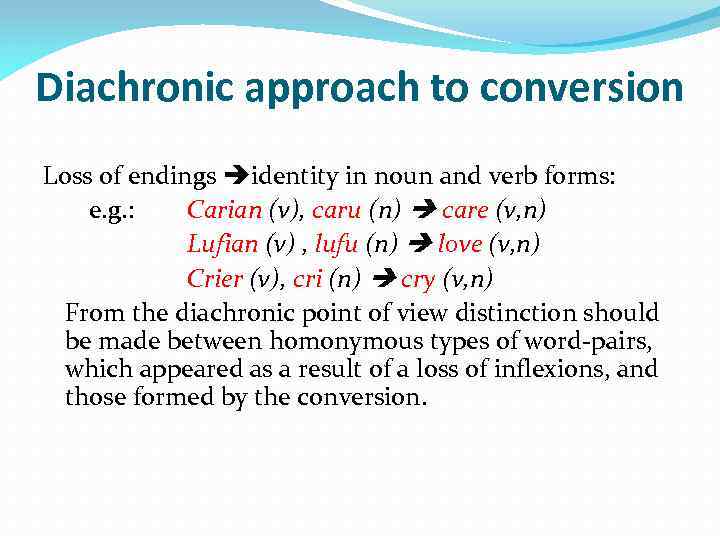

Diachronic approach to conversion Loss of endings identity in noun and verb forms: e. g. : Carian (v), caru (n) care (v, n) Lufian (v) , lufu (n) love (v, n) Crier (v), cri (n) cry (v, n) From the diachronic point of view distinction should be made between homonymous types of word-pairs, which appeared as a result of a loss of inflexions, and those formed by the conversion.

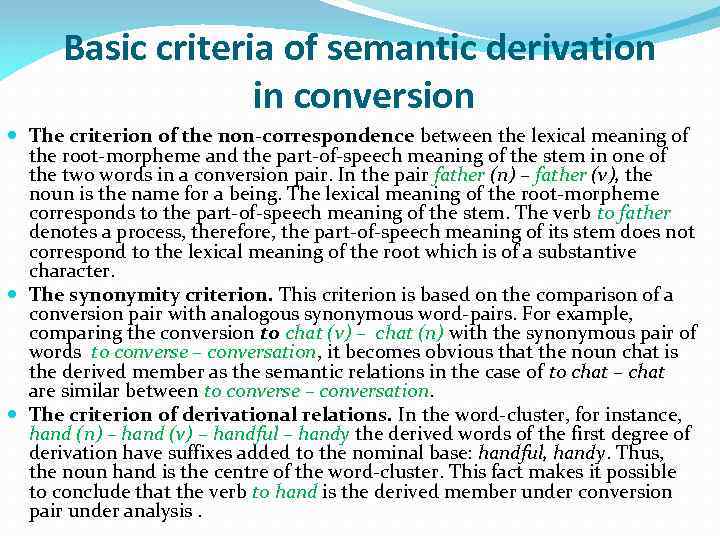

Basic criteria of semantic derivation in conversion The criterion of the non-correspondence between the lexical meaning of the root-morpheme and the part-of-speech meaning of the stem in one of the two words in a conversion pair. In the pair father (n) – father (v), the noun is the name for a being. The lexical meaning of the root-morpheme corresponds to the part-of-speech meaning of the stem. The verb to father denotes a process, therefore, the part-of-speech meaning of its stem does not correspond to the lexical meaning of the root which is of a substantive character. The synonymity criterion. This criterion is based on the comparison of a conversion pair with analogous synonymous word-pairs. For example, comparing the conversion to chat (v) – chat (n) with the synonymous pair of words to converse – conversation, it becomes obvious that the noun chat is the derived member as the semantic relations in the case of to chat – chat are similar between to converse – conversation. The criterion of derivational relations. In the word-cluster, for instance, hand (n) – hand (v) – handful – handy the derived words of the first degree of derivation have suffixes added to the nominal base: handful, handy. Thus, the noun hand is the centre of the word-cluster. This fact makes it possible to conclude that the verb to hand is the derived member under conversion pair under analysis.

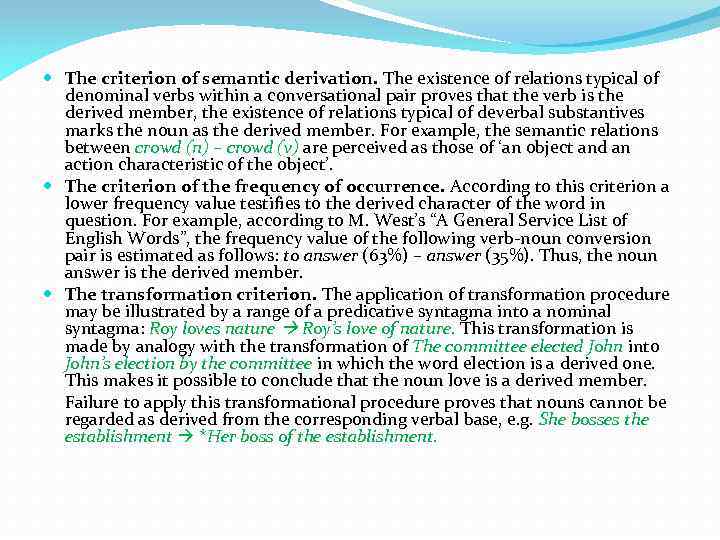

The criterion of semantic derivation. The existence of relations typical of denominal verbs within a conversational pair proves that the verb is the derived member, the existence of relations typical of deverbal substantives marks the noun as the derived member. For example, the semantic relations between crowd (n) – crowd (v) are perceived as those of ‘an object and an action characteristic of the object’. The criterion of the frequency of occurrence. According to this criterion a lower frequency value testifies to the derived character of the word in question. For example, according to M. West’s “A General Service List of English Words”, the frequency value of the following verb-noun conversion pair is estimated as follows: to answer (63%) – answer (35%). Thus, the noun answer is the derived member. The transformation criterion. The application of transformation procedure may be illustrated by a range of a predicative syntagma into a nominal syntagma: Roy loves nature Roy’s love of nature. This transformation is made by analogy with the transformation of The committee elected John into John’s election by the committee in which the word election is a derived one. This makes it possible to conclude that the noun love is a derived member. Failure to apply this transformational procedure proves that nouns cannot be regarded as derived from the corresponding verbal base, e. g. She bosses the establishment *Her boss of the establishment.

WORD-COMPOSITION Word-composition is the type of the wordformation, in which new words are produced by combining two or more Immediate Constituents, which are both derivational bases.

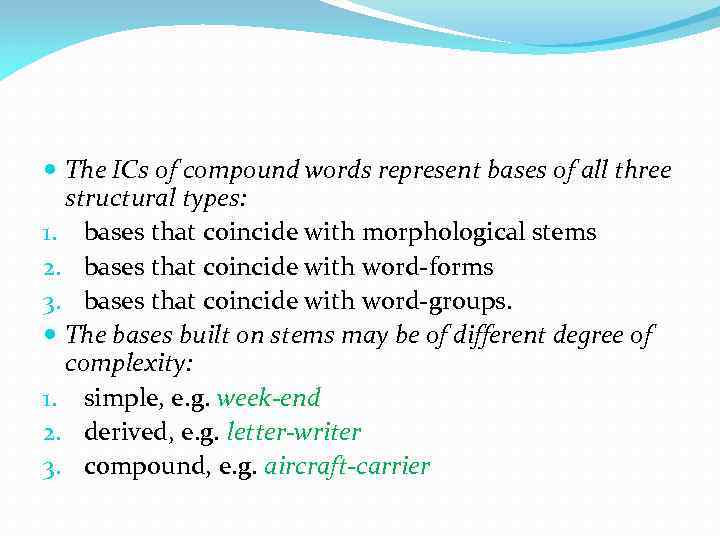

The ICs of compound words represent bases of all three structural types: 1. bases that coincide with morphological stems 2. bases that coincide with word-forms 3. bases that coincide with word-groups. The bases built on stems may be of different degree of complexity: 1. simple, e. g. week-end 2. derived, e. g. letter-writer 3. compound, e. g. aircraft-carrier

Meaning components The meaning of a compound word is made up of two components: structural and lexical. The structural meaning of compounds is formed on the base of: 1) the meaning of their distributional pattern and 2) the meaning of their derivational pattern.

Distributional pattern The distributional pattern of a compound is the order and arrangement of the ICs that constitute a compound word. A change in the order and arrangement of the same ICs signals the compound words of different lexical meanings, cf. : a fruit-market and market-fruit. The distributional pattern of a compound carries a certain meaning of its own which is largely independent of the actual lexical meaning of their ICs.

Derivational pattern The meaning of the derivational pattern can be abstracted and described through the interrelation of their ICs. N+Ven : duty-bound, wind-driven, mud-stained ‘instrumental or agentive relations’ Derivational patterns in compounds may be monosemantic or polysemantic. N+N N 1) the purpose (bookshelf); 2) resemblance (needle-fish); 3) of instrument or agent (windmill, sunrise).

Lexical meaning The lexical meaning of compounds is formed on the base of the combined lexical meanings of their constituents. The semantic centre of the compound is the lexical meaning of the second component modified and restricted by the meaning of the first. The lexical meanings of both components are closely fused together to create a new semantic unit with a new meaning, which dominates the individual meanings of the bases, and is characterized by some additional component not found in any of the bases. handbag

Classification of compound words 1. According to the relations between the ICs compound words 2. According to the part of speech compounds represent 3. According to the means of composition 4. According to the type of bases that form compounds

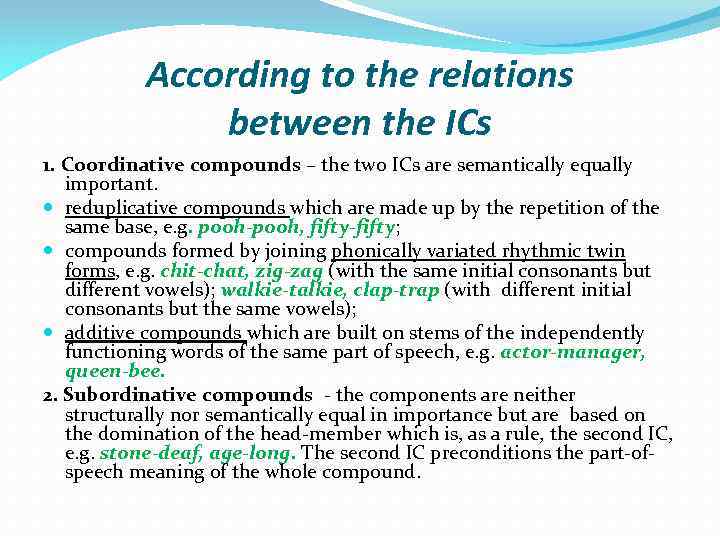

According to the relations between the ICs 1. Coordinative compounds – the two ICs are semantically equally important. reduplicative compounds which are made up by the repetition of the same base, e. g. pooh-pooh, fifty-fifty; compounds formed by joining phonically variated rhythmic twin forms, e. g. chit-chat, zig-zag (with the same initial consonants but different vowels); walkie-talkie, clap-trap (with different initial consonants but the same vowels); additive compounds which are built on stems of the independently functioning words of the same part of speech, e. g. actor-manager, queen-bee. 2. Subordinative compounds — the components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of the head-member which is, as a rule, the second IC, e. g. stone-deaf, age-long. The second IC preconditions the part-ofspeech meaning of the whole compound.

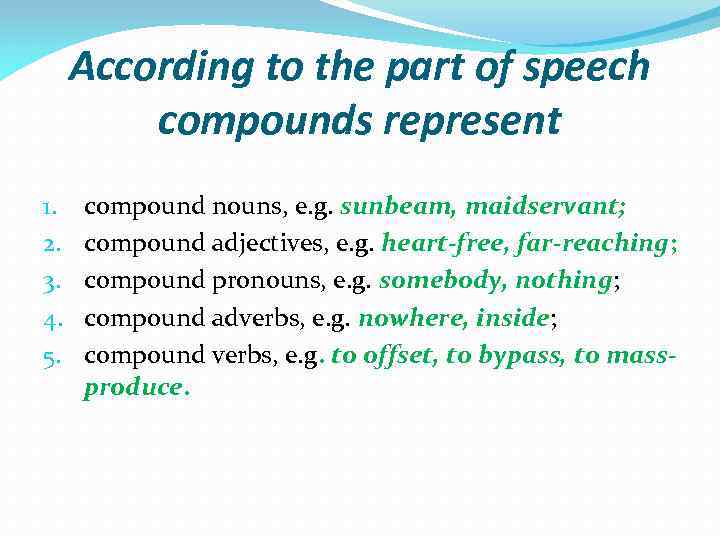

According to the part of speech compounds represent 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. compound nouns, e. g. sunbeam, maidservant; compound adjectives, e. g. heart-free, far-reaching; compound pronouns, e. g. somebody, nothing; compound adverbs, e. g. nowhere, inside; compound verbs, e. g. to offset, to bypass, to massproduce.

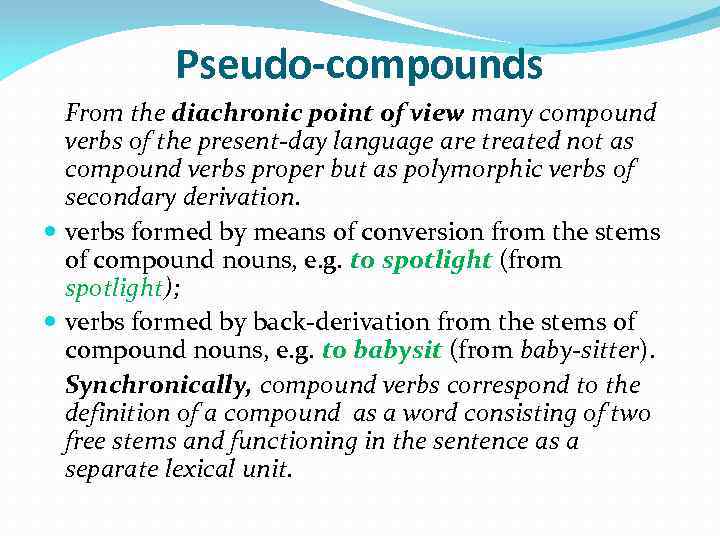

Pseudo-compounds From the diachronic point of view many compound verbs of the present-day language are treated not as compound verbs proper but as polymorphic verbs of secondary derivation. verbs formed by means of conversion from the stems of compound nouns, e. g. to spotlight (from spotlight); verbs formed by back-derivation from the stems of compound nouns, e. g. to babysit (from baby-sitter). Synchronically, compound verbs correspond to the definition of a compound as a word consisting of two free stems and functioning in the sentence as a separate lexical unit.

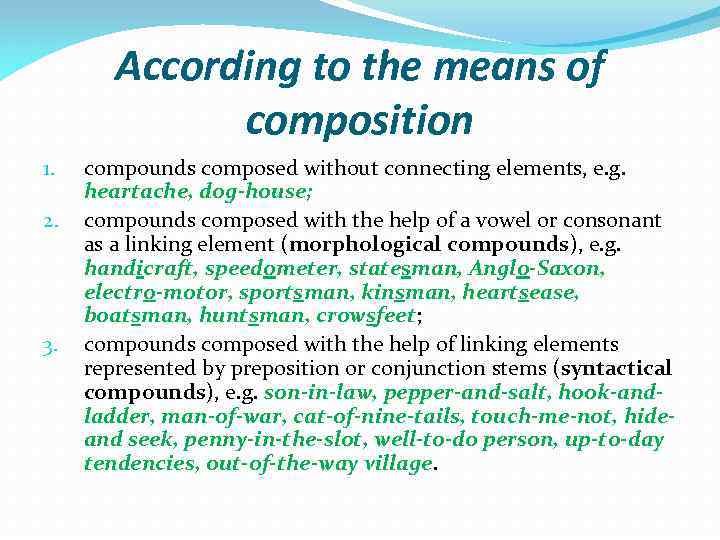

According to the means of composition 1. 2. 3. compounds composed without connecting elements, e. g. heartache, dog-house; compounds composed with the help of a vowel or consonant as a linking element (morphological compounds), e. g. handicraft, speedometer, statesman, Anglo-Saxon, electro-motor, sportsman, kinsman, heartsease, boatsman, huntsman, crowsfeet; compounds composed with the help of linking elements represented by preposition or conjunction stems (syntactical compounds), e. g. son-in-law, pepper-and-salt, hook-andladder, man-of-war, cat-of-nine-tails, touch-me-not, hideand seek, penny-in-the-slot, well-to-do person, up-to-day tendencies, out-of-the-way village.

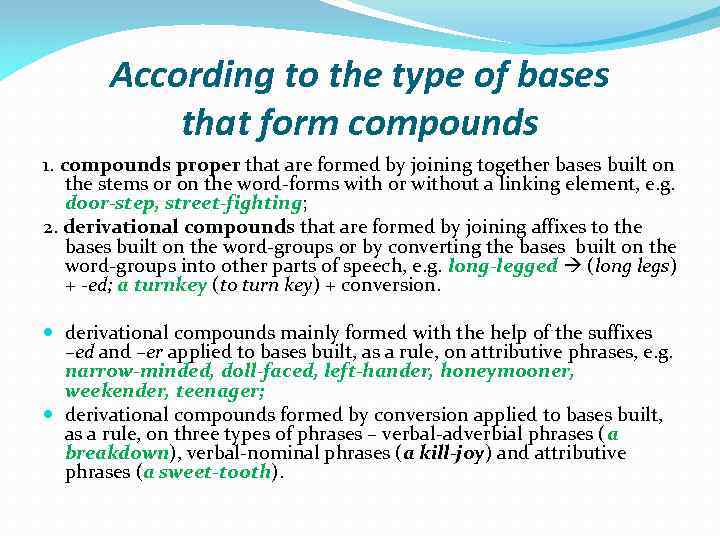

According to the type of bases that form compounds 1. compounds proper that are formed by joining together bases built on the stems or on the word-forms with or without a linking element, e. g. door-step, street-fighting; 2. derivational compounds that are formed by joining affixes to the bases built on the word-groups or by converting the bases built on the word-groups into other parts of speech, e. g. long-legged (long legs) + -ed; a turnkey (to turn key) + conversion. derivational compounds mainly formed with the help of the suffixes –ed and –er applied to bases built, as a rule, on attributive phrases, e. g. narrow-minded, doll-faced, left-hander, honeymooner, weekender, teenager; derivational compounds formed by conversion applied to bases built, as a rule, on three types of phrases – verbal-adverbial phrases (a breakdown), verbal-nominal phrases (a kill-joy) and attributive phrases (a sweet-tooth).

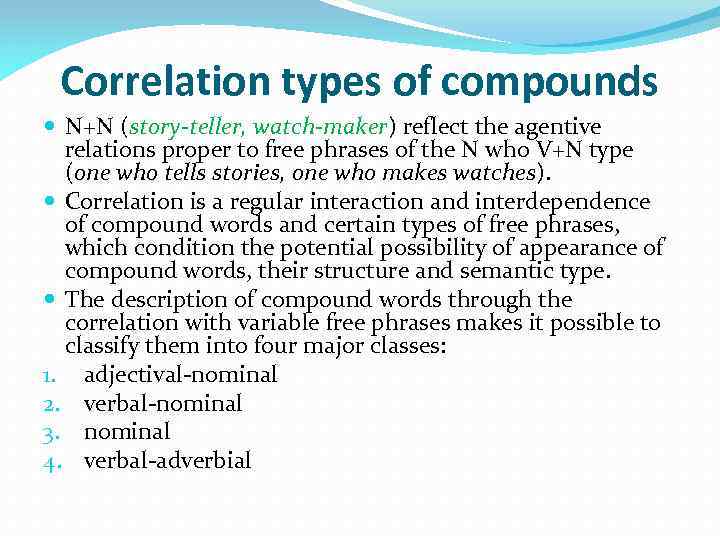

Correlation types of compounds N+N (story-teller, watch-maker) reflect the agentive relations proper to free phrases of the N who V+N type (one who tells stories, one who makes watches). Correlation is a regular interaction and interdependence of compound words and certain types of free phrases, which condition the potential possibility of appearance of compound words, their structure and semantic type. The description of compound words through the correlation with variable free phrases makes it possible to classify them into four major classes: 1. adjectival-nominal 2. verbal-nominal 3. nominal 4. verbal-adverbial

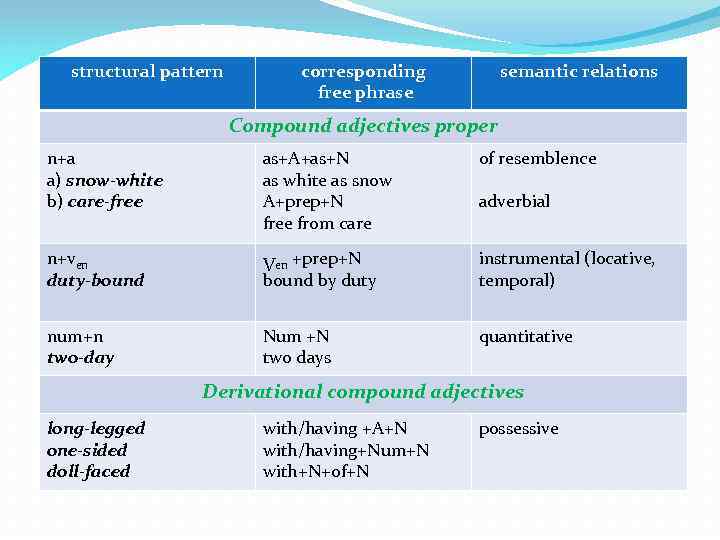

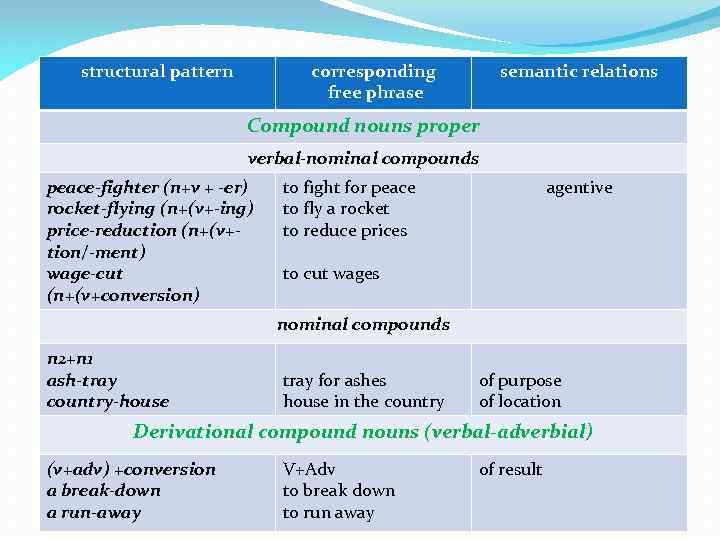

structural pattern corresponding free phrase semantic relations Compound adjectives proper n+a a) snow-white b) care-free as+A+as+N as white as snow A+prep+N free from cre care of resemblence n+ven duty-bound Ven +prep+N bound by duty instrumental (locative, temporal) num+n two-day Num +N two days quantitative adverbial Derivational compound adjectives long-legged one-sided doll-faced with/having +A+N with/having+Num+N with+N+of+N possessive

structural pattern corresponding free phrase semantic relations Compound adjectives proper Compound nouns proper n+a as+A+as+N verbal-nominal compoundsof resemblence a) snow-white(n+v + -er) as to fight for peace white as snow peace-fighter agentive b) care-free (n+(v+-ing) A+prep+Nrocket adverbial rocket-flying to fly a price-reduction (n+(v+- free from creprices to reduce tion/-ment) n+ven wage-cut duty-bound (n+(v+conversion) Ven +prep+N to cut wages bound by duty instrumental (locative, temporal) nominal compounds num+n Num +N quantitative two-day two days n 2+n 1 ash-tray for ashes of purpose Derivational compound adjectives country-house in the country of location long-legged with/having +A+N possessive Derivational compound nouns (verbal-adverbial) one-sided with/having+Num+N (v+adv) +conversion V+Adv of result doll-faced with+N+of+N a break-down to break down a run-away to run away

A

Abbreviation (syn. clipping, shortening) – a shortened form of a word or phrase, e.g., prof – professor, pike — turnpike, etc.

Abbreviation, graphical – a sign representing a word or word-group of high frequency of occurrence, e.g., Mr – Mister, Mrs – Mistress, i.e. (Latin “id est”) – that is, cf (Latin “cofferre”) – compare.

Abbreviation, lexical (syn. acronym) – a word formed from the first (or first few)

letters of several words which constitute a compound word or word-group, e.g.,

U.N.E.S.C.O. – United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, B.B.C. – the British Broadcasting Corporation, S.O.S. – Save Our Souls, B.A. – Bachelor of Arts, etc.

Ablaut (syn. vowel gradation or interchange) – a change from one to another vowel, characteristic of Indo-European languages, e.g., to bear – burden, to abide – abode, to bite – bit, to ride – rode, to strike – stroke, etc.

Absolute (total, complete) synonyms – synonyms so identical in their meaning that

one can always be substituted for by the other in any given context, e.g., fricative – spirant, almost – nearly, mirror – looking-glass, flection – inflection, noun – substantive, etc.

Acronym (see lexical abbreviation) – a word formed from the initial letters of a fixed phrase or title, e.g., TV – television, VIP – very important person, hi-fi –

high fidelity, etc.

Adjectivalization – the use of nouns and participles as adjectives, e.g., a stone wall,

home affairs, swimming-pool, etc.

Adverbialization – the use of adjectives as adverbs, e.g., he spoke loud (loudly), it tastes good, etc.

Affix (affixational morpheme) – a derivational morpheme which is always bound to a stem or to a combination containing a stem, e.g., un mistak able, un pardon able, ir regulari ty. Affixes are subdivided into prefixes, suffixes and infixes according to their position (see prefix, suffix, infix), e.g., un-, dis-, re-, -ful, -less, -able,

etc.

Affixation – is the formation of new words by adding derivative affixes to derivational bases or stems, e.g., kind + ness, grate + ful, un + happy, im +

moral, etc.

Allomorphs – positional variants of a morpheme characterized by complementary distribution (they are used in mutually exclusive environment and stand in alternation with each other), e.g., allomorphs of the prefix in- are: il- (illegal), ir- (irregular), im- (impossible), etc.

Amelioration or elevation (a semantic shift of meaning) – the improvement of the connotational component of meaning, i.e. a lexeme develops a positive meaning, e.g., nice originally meant foolish, knight originally meant boy, fame originally meant report, common talk, rumour, minister originally meant servant, etc.

Americanism – a word or a set expression peculiar to the English language as spoken in the USA, e.g., cookie – biscuit (Br.E.), fall – autumn (Br.E.), truck – lorry (Br.E.), movies – pictures (Br.E.), sidewalk – pavement (Br.E.), etc.

Antonyms – words of the same parts of speech different in sound-form, opposite in

their denotational meaning or meanings and interchangeable in some contexts, e.g., short – long, to begin – to end, regular – irregular, day – night, thick – thin, early – late, etc.

Aphaeresis, aphesis – initial clipping, i.e. the formation of a word by the omission of

the initial part of the word, e.g., phone from telephone, mend from amend, story

from history, etc.

Apocope – final clipping, i.e. the omission of the final part of the word, e.g., exam from examination, gym from gymnasium or gymnastics, lab from laboratory, ref from referee, etc.

Archaisms – words which have come out of active usage, and have been ousted by their synonyms. They are used as stylistic devices to express solemnity. Many lexical archaisms belong to the poetic style: woe (sorrow), betwixt (between), to chide (to scold), save (except) etc.

Sometimes the root of the word remains and the affix is changed, then the old affix is considered to be a morphemic archaism, e.g. beautious (-ous was

substituted by -ful); darksome (some was dropped); oft (-en was added) etc.

Assimilation (of a loan word) – a partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical and morphological standards of the English language and its semantic system.

Asyntactical compounds – compounds whose components are placed in the order that contradicts the rules of English syntax, e.g., snow-white (N + A) (in syntax: white snow – A + N), pale-green – A + A, etc. (see syntactic compounds).

В

Back-formation – derivation of a new word by subtracting a real or supposed affix from an existing word, e.g., to sculpt – sculptor, to beg – beggar, to burgle – burglar, etc.

Barbarisms – unassimilated borrowings or loan words, used by English people in conversation or in writing, printed in italics, or in inverted commas, e.g., such French phrases as топ cher – my dear, tête-a-tête – face to face, or Italian words, addio, ciao – good bye.

Blending or telescoping – formation of a word by merging parts of words (not morphemes) into one new word; the result is a blend, fusion, e.g., smog

(smoke + fog), transceiver (transmitter + receiver), motel (motor + hotel),

brunch (breakfast + lunch), etc.

Borrowings (also loan words) – words taken over from another language and (partially or totally) modified in phonetic shape, spelling, paradigm or meaning according to the standards of the English language, e.g., rickshaw (Chinese), sherbet (Arabian), ballet, café, machine, cartoon, police (French), etc.

Bound form (stem or morpheme) – a form (morpheme) which must always be combined with another morpheme (i.e. always bound to some other morpheme)

and cannot stand in isolation, e.g., nat- in native, nature, nation; all affixes are bound forms.

Briticism – a lexical unit peculiar to the British variant of the English language, e.g.,

petrol is a Briticism for gasoline; opposite Americanism.

C

Cliché – a term or phrase which has become hackneyed and stale, e.g., to usher in a new age (era), astronomical figures, the arms of Morpheus, swan song, the irony of fate, etc.

Clipping – formation of a word by cutting off one or several syllables of a word, e.g., doc (from doctor), phone (from telephone), etc. (see abbreviation, apocope, aphaeresis, syncope).

Cockney – the regional dialect of London marked by some deviations in pronunciation and few in vocabulary and syntax, e.g., fing stands for thing,

farver for farther, garn for go on, toff for a person of the upper class.

Coding (in lexicology) – replacing words or morphemes by conventional word- class symbols, e.g., to see him go (V + N/pron + V), blue-eyed ((A + N) +

-ed), etc.

Cognates (cognate words) words descended from a common ancestor, e.g.,

brother (English), брат (Ukrainian), frater (Latin), Bruder (German).

Collocability – see lexical valency.

Collocation – habitual lexico-phraseological association of a word in a language with other particular words in a sentence, e.g., to pay attention to, to meet the demands, cold war, etc.

Colloquial (of words, phrases, style) – belonging to, suitable for, or related to ordinary; not formal or literary conversation, e.g., there you are, you see, here’s

to us, to have a drink, etc.

Combinability (occurrence-range, collocability, valency) – the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Complementary distribution – is said to take place when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment (i.e. they appear in mutually exclusive environment and stand in alternation with each other, e.g., variants of the prefix

in- (im-, il-, ir-) are characterized by complementary distribution as in imperfect, illegal, irregular.

Composition – see word-composition.

Compounding – see word-composition.

Compound-derivative or derivational compound – a word formed simultaneously by composition and derivation, e.g., blue-eyed, old-timer, teenager, kind-hearted, etc.

Compound words or compounds – words consisting of at least two stems or root

morphemes which occur in the language as free forms, e.g., tradesman, Anglo- Saxon, sister-in-law, honeymoon, passer-by, etc.

Concept (syn. notion) – an idea or thought, especially a generalized idea of a class of objects, the reflection in the mind of real objects and phenomena in their

essential features and relations.

Connotation – complementary meaning or complementary semantic and (or) stylistic shade which is added to the word‟s main meaning and which serves to express all sorts of emotional, expressive, evaluative overtones.

Connotational (meaning) – the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.

Content – the main substance or meaning, e.g., the content of a poem is

distinguished from its form.

Context – the minimum stretch of discourse necessary and sufficient to determine which of the possible meanings of a polysemantic word is used.

Contrastive distribution – characterizes different morphemes, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings (see complementary

distribution), e.g., the suffixes -able and -ed are different morphemes, because adjectives in -able mean capable of being, e.g., measurable, whereas -ed has a resultant force, e.g. measured.

Conversion (root formation, functional change, zero-derivation) – the formation

of a new word solely by changing its paradigm or the method of forming a new word by changing an existing one into another part of speech without any derivational affixes (or other external changes), so that the resulting word is homonymous with the original one, e.g. water (n) – to water (v); dry (adj) – to dry (v); must (v) – a must (n), go (v) a go (n).

Convertive prefix – a prefix which transfers words to a different part of speech, e.g. pre + war (n) = prewar (adj); de + plane = deplane (v); de + part (n) = depart (v).

Contextual synonyms – words (synonyms) similar in meaning only under some specific distributional conditions (in some contexts), e.g. bear, suffer and stand when used in the negative construction can’t bear, can’t suffer, can’t stand become synonyms.

Coordinative (or copulative) compounds – compounds whose components are structurally and semantically independent and constitute two structural and

semantic centres, e.g., actor-manager, fifty-fifty, secretary-stenographer, etc.

D

Degradation of meaning (also pejoration or deterioration) – the appearance of a derogatory and scornful emotive charge in the meaning of the word, i.e. a lexeme develops a negative meaning, e.g. knave (OE – boy), silly (OE – happy), boor (OE – farmer).

Demotivation – loss of motivation, when the word loses its ties with another word or

words with which it was formerly connected and associated, ceases to be understood as belonging to its original word-family, e.g. lady, breakfast,

boatswain, to kidnap, etc.

Denominal verb – a verb formed by conversion from a noun or an adjective, e.g., stone – to stone, rat – to rat, empty – to empty, nest – to nest, corner – to corner, etc.

Denotation (see referent) – the direct, explicit meaning or reference of a word or term.

Denotational (or denotative) meaning – the component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible, i.e. the component of meaning signifying or identifying the notion or the object and reflecting some essential features of the notion named; see referential meaning.

Derivation – the process of forming new words by affixes, sound and stress interchange, e.g. work – worker, kind – unkind, food – feed, blood – bleed, life – live, present – present, import – import. Some scholars include conversion into

derivation, too.

Derivational affix — an affix which serves to form new words, e.g. -less in help less

or dis- in dislike, etc.

Derivational level of analysis is aimed at establishing the derivational history of the word in question, i.e. at establishing through what word-building means it is built and what is its structural or word-building pattern. The method of analysis into immediate and ultimate constituents (IC‟s and UC‟s) is very effective on this level, e.g. threateningly (adv) falls into the following IC‟s:

1) threatening + — ly on the pattern A + -ly,

2) threaten + -ing on the pattern V +-ing,

3) threat + -en on the pattern N+ -en

Thus, the adverb threateningly is a derivative built through affixation in three steps.

Derivational suffix – a suffix serving to form new words, e.g. read- able, help less, use ful etc., see suffix.

Derivative (syn. derived word) – a word formed through derivation, e.g. manhood, rewrite, unlike, etc.

Derived stem – a stem (usually a polymorphemic one) built by means of derivation;

a stem comprising one root-morpheme and one or more derivational affixes, e.g.

courageously, singer, tigress, etc.

Descriptive approach – see synchronic approach.

Deterioration – see degradation of meaning.

Deverbal noun – a noun formed from a verb by conversion, e.g. to buy – a buy,

must – a must, to cut – a cut, etc.

Diachronic or historic approach (in lexicology) – the study of the vocabulary in its

historical development, see synchronic approach.

Dialect (local) – a variety of the English language peculiar to some district and having no normalized literary form, e.g. Cockney, Northern, Midland, Eastern dialects

of England, etc., see variant.

Dictionary – a book of words in a language usually listed alphabetically with definitions, translations, pronunciations, etymologies and other linguistic information. Kinds of dictionaries: bilingual, encyclopaedic, etymological,

explanatory, general, ideographic, linguistic, multilingual, phraseological, pronouncing, special, unilingual etc.

Differential meaning (of a morpheme) – the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from the others containing identical morphemes, e.g. cranberry, blueberry, blackberry.

Distribution – possible variants (the total, sum) of the immediate lexical, grammatical and phonetic environment of a linguistic unit (i.e. the position of a linguistic sign in relation to other linguistic signs). For a morpheme it is the preceding and following morpheme(s), for a word it is the preceding and the

following word(s), for a phoneme it is the preceding and the following phoneme(s); see the complementary and contrastive distribution.

Distributional meaning (of a morpheme) – the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word, cf, ring-finger and finger ring.

Distributional pattern – a phrase (word) all elements of which including the head- word are coded, e.g. to hear smb sing (V+ N/pron + V,), copybook (N + N), red-

haired (A + N + suffix).

Distributional formula – a structure (phrase, word) whose components except the head one are coded, e.g. to hear somebody sing (hear + N/pron + V). In distributional formulas of words affixes are usually coded: e.g. blue-eyed ((A + N) + -ed).

Doublet – see etymological doublet.

E Elevation of meaning – see amelioration.

Ellipsis – the omission of a word or words considered essential for grammatical completeness but easily understood in the context, e.g. daily (paper), (cut-price) sale, private (soldier), etc.

Emotive charge – a part of the connotational component of meaning evoking or directly expressing emotion, e.g. cf: girl and girlie.

Etymological doublet – either of two words of the same language which were derived by different routes from the same basic word, e.g. chase – catch, disc – dish, shirt – skirt, scar – share, one — an, raid — road, etc.

Etymology – a branch of lexicology dealing with the origin and history of words, especially with the history of form.

Etymological level of analysis is aimed at establishing the etymology (origin) of the word under analysis, i.e. at finding out whether it is a native English word, or a borrowing or a hybrid, e.g. ballet is a French borrowing, threateningly is a native

English word, nourishing is a hybrid composed of morphemes of different origin: nourish is a French borrowing, but -ing is a native English suffix.

Euphemism – a word or phrase used to replace an unpleasant word or expression by a conventionally more acceptable one, e.g. to be no more, to pass away for to die;

to tell stories, to distort the facts for to lie; remains for corpse; paying guest for

lodger.

Extension (also generalization or widening) of meaning – changes of meaning resulting in the application of a word to a wider variety of referents. It includes the change both from concrete to abstract and from specific to general, e.g. journal originally meant daily; a thing originally meant meeting, decision; salary originally meant salt money; pioneer originally meant soldier.

F

Form words,also called functional words, empty words or auxiliaries are lexical units used only in combination with notional words or in reference to them, e.g. auxiliary verbs – do, be, have, prepositions – in, at, for, conjunctions – while, since, etc.

Free forms – forms which may stand alone without changing their meaning, i.e. forms homonymous with words, e.g. the root-morpheme teach- in teacher.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words,

e.g. first-nighter.

Functional (or grammatical) affixes – affixes serving to build different (grammatical) forms of one and the same word, e.g. — (e)s in boys, classes, -ed in worked, etc.

Functional approach to meaning – an approach showing that the meaning of a linguistic unit (word) may be studied only through its relation to other linguistic

units (words) and not through its relation to either concept or referent, i.e. it

views the meaning as the function of distribution, see referential approach to meaning.

Functional meaning (of a morpheme) – the part-of-speech meaning of the morpheme, e.g. the part-of-speech meaning of the suffixes -ize in verbs and — ice – in nouns as in the words realize and justice, etc.

Fusion – see blend(ing), also phraseological fusions.

G

Generalization – see extension or widening of meaning, e.g. ready from OE rade

that meant prepared for a ride, animal from Latin anima soul.

Glossary – a list of special or difficult terms with explanations or translations, often included in the alphabetical order at the end of a book.

Grammatical homonyms – homonyms that differ in grammatical meaning only (i.e. homonymous word-forms of one and the same word), e.g. cut (infinitive) – cut (past participle); boys – boy’s.

Grammatical meaning – the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of grammatical forms of different words as, e.g., the meaning of the plural number in the word-forms of nouns: books, tables, etc., grammatical meaning expresses in speech the relationship between words.

Grammatical valency – the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures.

H

Historism – a word which denotes a thing that is outdated nowadays or the causes of the word‟s disappearance are extra-linguistic. Historisms are very numerous as names for social relations, institutions, objects of material culture of the past, e.g. transport means: brougham, berlin, fly, gig, phaeton etc.; vehicles as prairie schooner (a canvas-covered wagon used by pioneers crossing the North American prairies) etc.; weapons: breastplate, crossbow, arrow, etc.

Homographs – words identical in spelling but different both in their sound-form and

Homonyms – words identical in sound or spelling (or in both) but different in meaning (in semantic structure), e.g. sound (adj) – sound (n).

Homonyms proper (syn. absolute, perfect) – words identical in sound-form and spelling but different in meaning, e.g. temple – скроня, temple – храм; seal – печатка, seal – тюлень, etc.

Homonyms, etymological (syn. historical homonyms) – homonyms that are etymologically different words, e.g. sea – море, to see – бачити, bear – ведмідь, to bear – народжувати, etc.

Homonyms, full – words that are homonymous in all their forms, e.g. seal –

тюлень, seal – печать; mole – кріт, mole – родимка.

Homonyms, grammatical – words that have homonymous forms of the same word,

e.g. he asked – he was asked; boys’ – boys, etc.

Homonyms, lexical – words that differ in lexical meaning, e.g. knight (лицар) –

night (ніч), ball (м‟яч)- ball (бал), etc.

Homonyms, lexico-grammatical – words that differ both in lexical and grammatical meaning, e.g. swallow – ластівка, to swallow – ковтати, well – джерело, well – добре, etc.

Homonyms, partial – words that are homonymous in some of their forms,e.g.

brothers (pl) – brother’s (possessive case), etc.

Homophones – words identical in sound-form but different both in spelling and in meaning, e.g. to know – no, not – knot, to meet – meat, etc.

Hybrid – a word made up of elements derived from two or more different

languages, e.g. fruitless (Fr. + native), readable (native + Fr.), unmistakable

(native + native + Fr.), schoolgirl (Gk. + native), etc.

Hyperbole – an exaggerated statement not meant to be understood literally but expressing an emotional attitude of the speaker to what he is speaking about,

e.g. Lovely! Awful! Splendid! For ages, floods of tears, a world of good, awfully well etc.

Hyponymy – type of paradigmatic relationship when a specific term is included in a generic one, e.g. pup is the hyponym of dog, and dog is the hyponym of animal, etc.

I

Ideographic (relative) synonyms – synonyms denoting different shades of meaning or different degrees of intensity (quality), e.g. large, huge, tremendous; pretty, beautiful, fine; leave, depart, quit, retire; understand, realize, etc.

Idiom – an accepted phrase, word-group, or expression the meaning of which cannot be deduced from the meanings of its components and the way they are put together, e.g. to talk through one’s hat, to smell a rat, a white elephant, red tape, etc.

Idiomatic (syn. non-motivated) – lacking motivation from the point of view of one’s mother tongue.

Immediate Constituents analysis – cutting of a word into IC’s. It is based on a binary principle.

Immediate Constituents (IC’s) – the two immediate (maximum) meaningful parts forming a larger linguistic unity, e.g. the IC‟s of teacher are teach and -er, red-haired – red and hair and -ed, etc.

Infix – an affix placed within the stem (base), e.g. stand and stood. Infixes are not productive in English.

International words – words borrowed from one language into several others simultaneously or at short intervals one after another, e.g. biology, student, etc.

J

Juxtaposition – the way of forming compounds by placing the stems side by side without any linking elements. It is very productive in English, e.g. airline, postman, blue-bell, waterfall, house-keeper, etc.

Juxtapositional compound – a compound whose components are joined together without any linking elements, i.e. by placing one component after another in a definite order, e.g. door-handle, snow-white, etc.

L

Lexical meaning – the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i.e. recurrent in all the forms of this word and in all the possible distributions of these forms.

Lexical transformation – a paraphrasis of a phrase (sentence) in which some word is replaced by its semantic equivalent or definition, e.g. (he is) an English teacher – (he is) a person who teaches English; (the sky was) cloudy – (the sky

was) covered with clouds, etc., see transformation.

Lexical valency (or valence, collocability) – the aptness of a word to appear in various combinations with other words.

Lexicography – a branch of applied lexicology concerned with the theory and practice of compiling dictionaries.

Lexicology – a branch of linguistics dealing with the vocabulary of a language and the properties of words, word-equivalents and word-collocations.

Litotes or understatement – a word or word-group which expresses the affirmative by the negation of its contrary, e.g. not bad for good, not small for great, no coward for brave, etc.

Loan-words – see borrowings.

M

Meaning – an essential aspect of any linguistic sign (word) reflecting objective reality in our consciousness. The relation between the object or notion named and the name itself. Kinds of meaning: abstract, archaic, basic, central, concrete, connotational or connotative, denotational or denotative, derived, differential (in morphemes), direct, distributional (in morphemes), etymological, extended, figurative, functional (in morphemes), grammatical, lexical, lexico-grammatical, literal, main, major, marginal, metaphoric, metonymic, minor, obsolete, original, secondary, transferred.

Metaphor – transfer of meaning based on the association of similarity, e.g.

1) similarity of shape: head of a cabbage, nose of a plane;

2) similarity in function or use: hand of a clock, wing of a plane;

3) similarity in temperature: hot scent, cold reason, warm heart;

4) likeness in colour: orange for colour and for fruit;

5) analogy between duration of time and space: long distance vs long speech;

6) transition of proper names into common ones: an Adonis, a Cicero, a Don

Juan;

7) likeness in position: foot of a man vs foot of a hill;

Metonymy – transfer of meaning based on contiguity, i.e. by naming a closely related object or idea, e.g.

1) giving the part for the whole (synecdoche): house may denote the Members of the Parliament; The White House, The Pentagon can mean its staff and

policy;

2) the sign for the thing signified: ‘gray hair’ – old age;

3) the container for the thing contained: the kettle is boiling (water);

5) geographical names turning into common nouns (to name the goods exported or originating there): china, champagne, burgundy, cheddar;

6) the material substitutes the thing made of: glass, iron, copper, nickel;

7) symbol for thing symbolized: „the crown‟ for monarchy.

Morpheme – the smallest linguistic unit possessing meaning (or the minimum

meaningful unit of language), e.g. un-luck-i-ly has four morphemes, see root morphemes and affixes.

Morphemic analysis – splitting the word into its constituent morphemes and

determining their number and types.

Morphemic level of analysis is aimed at establishing the number and type of the morphemes making up the word, e.g. the adverb threateningly is a polymorphemic word consisting of four morphemes of which one is a root

morpheme and three derivational morphemes.

Morphological composition – the way of forming compounds by joining together two stems with the help of special linking elements: -о-, -i-, -s-, e.g. handicraft, gasometer, sportsman, etc.

Morphological compound – a compound whose components are joined together with a linking element, e.g. speedometer, handiwork, spokesman, etc.

Morphological motivation (of a word or phraseological unit) – a direct connection between the structural (morphological) pattern of the word (or phraseological

unit) and its meaning, e.g. fatherless, greatly, thankful, etc.

Motivated (non-idiomatic, transparent) words are characterized by a direct connection between their morphemic or phonemic composition and their meaning, e.g. motorway, friendship, boom, cuckoo, etc.

Motivated word-groups are word-groups whose combined lexical meaning can be

deduced from the meaning of their component-members, e.g. to declare war, head of an army, to make a bargain, to cut short, to play chess, etc.

Motivation – the relationship between the morphemic or phonemic composition of the word and its meaning, e.g. schoolchild, moo, tick, etc.

N

Narrowing of meaning (also restriction or specialization) – the restriction of the semantic capacity of a word in the course of its historical development, e.g. meat originally meant food, dear originally meant beast, hound originally meant dog, etc.

Neologism – a new word or word equivalent formed according to the productive

structural patterns or borrowed from another language; a new meaning of an established word, e.g. dictaphone, travelogue, monoplane, multi-user, pocketphone, sunblock, etc.

Nonce-word – a word coined and used for a single occasion, e.g. Bunburyist (O. Wilde), dimple-making (Th. Hardy), library-grinding (S. Lewis), family- physicianery (J.K. Jerome).

О

Obsolete words – words that drop from the language completely or remain in the language as elements performing purely historical descriptive functions. Names of obsolete occupations are often preserved as family names, e.g. Chandler – candle maker, Latimer (i.e. Latiner) – interpreter, Webster – weaver (with — ster the old feminine ending).

Occasionalism – a word or a word-combination created in each case anew, e.g.

living metaphors whose predictability is not apparent, e.g. the ex-umbrella man, a

horse-faced woman, a gazelle-eyed youth, cobra-headed anger, etc.

Onomatopoeia (syn. sound imitation, sound symbolism) – the formation of a word by imitating the natural sound associated with the object or action involved, e.g. buzz, cuckoo, tinkle, cock-a-doodle-do, etc.

Origin – the historic source of any linguistic unit or item.

P

Paradigm – the system of grammatical forms characteristic of a word, e.g. to write,

wrote, written, writing, writes; girl, girl’s, girls, girl’’, etc.

Paradigmatic relationships are based on the interdependence of words within the vocabulary.

Paronyms are words kindred in sound form and meaning and therefore liable to be mixed but in fact different in meaning and usage and therefore only mistakenly

interchanged, e.g. to affect – to effect, allusion – illusion, ingenious – ingenuous,

etc.

Pejoration – see degradation.

Phrase (syn. collocation, word-combination, word-group) – a lexical unit comprising more than one word, e.g. to go to school, a red apple etc. Kinds of phrases: adjectival, e.g. rich in gold, etc.; free, e.g. green leaves – yellow leaves – dry leaves, etc.; nominal, e.g. a blue sky, Jack of all trades, etc.; verbal, e.g. to go to school, to cry over spilt milk, etc.; motivated, e.g. fine weather, to play the piano, etc.; non-motivated, e.g. red tape, by hook or by crook, etc.

Phraseological collocations (combinations) – motivated phraseological units made up of words possessing specific lexical valency which accounts for a certain degree of stability and strictly limited variability of member-words, e.g. to bear a grudge or to bear a malice, to win the race, to gain access, etc.

Phraseological fusions (idioms) – completely non-motivated invariable phraseological units whose meaning has no connection with the meaning of the

components (i.e. it cannot be deduced from the knowledge of components), e.g.

to pay through the nose (to pay a high price); red tape (bureaucratic methods), etc.

Phraseological units (syn. set expressions, fixed combinations, units of fixed context, idioms) – partially motivated or non-motivated word-groups that cannot be freely made up in speech but are reproduced as ready-made units.

Phraseological unities – partially non-motivated phraseological units whose meaning can usually be perceived through the metaphoric meaning of the whole unit, e.g. to know the way the wind blows, to show one’s teeth, to make a mountain out of a mole-hill, etc.

Phraseology – a branch of linguistics studying set-phrases – phraseological units of all kinds.

Pidgin – a simplified form of speech developed as a medium of trade or through other contacts between groups of people who speak different languages.

Polymorphic – having two or more morphemes, e.g. inseparable, boyishness,

impossibility, etc.

Polysemantic words – having more than one meaning, e.g. board, power, case, etc.

Polysemy – plurality of meanings, i.e. co-existence of the various meanings of the same word and the arrangement of these meanings in the semantic structure of the word, e.g. maid 1) a girl, 2) a woman servant.

Prefix – a derivational affix (morpheme) placed before the stem, e.g. un- (unkind), mis- (misuse), etc. Kinds of prefixes: borrowed, e.g. re-, ex-, sub-, ultra-, non-,

etc.; native, e.g. un-, under-, after-, etc.; non-productive (unproductive), e.g. in- (il-, im-, ir-), etc.; productive, e.g. un-, de-, non-, etc.

Prefixation – the formation of words with the help of prefixes. It is productive in

Modern English, especially so in verbs and adjective word-formation.

Productive affixes – affixes which participate in the formation of new words, in neologisms in particular, i.e. which are often used to form new words; opposite

non-productive (unproductive).

Productivity – the ability of a given affix to form new words.

Proverb – a sentence expressing popular wisdom, a truth or a moral lesson in a concise and imaginative way, e.g. a friend in need is a friend indeed, while there is life there is hope, make hay while the sun shines, etc.

R

Reduplication – a method of forming compounds by the repetition of the same root, e.g. to pooh-pooh, goody-goody, etc.

Reduplicative compound – a compound formed with the help of reduplication, e.g.

tick-tick, hush-hush, etc.

Referent (denotatum) – the part (aspect) of reality to which the linguistic sign refers

(objects, actions, qualities), etc.

Referential approach to meaning – the school of thought which seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between the word (sound-form), the concept (reference) underlying this form and the actual referent.

Referential meaning (denotational) meaning – denoting, or referring to something, either by naming it John, boy, red, arrive, with, if or by pointing it out be this so.

Root (morpheme) – the primary elements of the word conveying the fundamental lexical meaning (e.g. the lexical nucleus of the word) common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word family, e.g. speak, speaker, speech, spoken.

S

Semantic – relating to meaning, dealing with meaning in language.

Semantic changes – changes of meaning, see amelioration, degradation,

extension, narrowing of meaning.

Semantic field – a grouping of words based on the connection of the notions underlying their meanings, e.g. face, head, hand, arm, foot, etc.

Semantic fields – ideographic groups of words and expressions grouped together

according to the fields of human interest and activity which they represent, e.g.

the semantic field of time.

Semantic level of analysis – aimed at establishing the word‟s semantic structure or the type of meaning in which the word under analysis is used in a given context, e.g. sense is a polysemantic word, contemptuous is a monosemantic word.

Semantic motivation – based on the co-existence of direct and figurative meanings.

When a word is used in a transferred meaning, metaphorical or otherwise, the result will be semantically motivated: it will be transparent thanks to the

connection between the two senses, e.g. head of an army, the root of an evil, the

branches of science, etc.

Semantics – see semasiology.

Semasiology – the branch of lexicology that is devoted to the study of meaning.

Seme(me) – the meaning of a morpheme.

Semi-affixes (semi-suffixes) – elements which stand midway between root- morphemes and affixes, i.e. root-morphemes functioning as derivational affixes, e.g. -man (in sea man, air man, work man, chair man, etc.), -like (child like, gentleman like, businesslike, etc.); -proof (fire -proof, water -proof), etc.

Semiotics (semiology) – the science dealing with various systems of signs (including all sorts of codes, military and traffic signals, languages in general, etc.).

Set expression – see phraseological unit.

Simile – a comparison, but an indirect one, using words, such as seem, like, or as to link two objects of the comparison, e.g. My love is like a melody. I wandered lonely as a cloud, etc.

Slang – a vocabulary layer below the level of standard educated speech.

Sound imitation – see onomatopoeia.

Sound interchange – a diachronically relevant unproductive way of word-formation due to an alteration in the phonetic composition of the root, i.e. consonant interchange and vowel interchange (umlaut, or vowel mutation, and ablaut, or vowel gradation), e.g. to speak – speech, to prove – proof, blood – to bleed, food – to feed, etc.

Sound symbolism – associating a certain type or class of meaning with a certain sound or cluster of sounds, e.g. there seems to be in English an association

between the initial consonant cluster (sn) and the nose, e.g. snarl, sneer, sneeze, sniff, snore, snort, snuffle.

Specialization of meaning — see narrowing.

Standard English – the official language of Great Britain used by the press, the radio and the television and spoken by educated people. It may be defined as that form of English which is current and literary, substantially uniform and

recognized as acceptable wherever English is spoken or understood.

Stem – 1) the part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm (secondary stem), e.g. worker, lucky – the secondary stems are: worker- (cf. workers, worker‟s) and lucky- (cf. luckier, luckiest); 2) the part of the word that remains when the immediate derivational affix is stripped off, i.e. the part on which the word is built (primary or derivational stem), e.g. the primary stems of worker, lucky are work and luck. Kinds of stems: simple, e.g. place, green, derived, e.g. useful, uselessness, bound, e.g. arrogance, arrogant, compound, e.g. trade-union, etc.

Style of language – a system of expressive means of language peculiar to a specific sphere of communication, e.g. the newspaper style, the belles-letres style, etc.

Stylistic level of analysis is aimed at establishing the stylistic colouring of the word, e.g. nourishment is a word of literary style, threat is a word of neutral style,

baccy (curtailment of tobacco) is a word of colloquial style.

Stylistics – a branch of general linguistics dealing with the study of language styles and stylistic devices.

Stylistic synonyms – words that are similar in their denotational meaning(s) but different in their connotational meaning(s), e.g. motherly – maternal, to put off – to postpone, cf. absolute (total, complete) synonyms.

Subordinative (often called determinative) compound – a compound whose components are not equal in importance. The relation between them is based on the domination of one component over the other. The second component in

these compounds is the structural and semantic centre (head) which imparts the part-of-speech meaning to the whole word, e.g. banknote, teaspoon, duty-free, grandson, etc.

Substantivation – turning into nouns, e.g. female (n) from female (adj), relative (n)

from relative (adj), criminal (n) from criminal (adj), etc.

Substitution – the method of testing similarity (or difference) by placing into identical environment (within identical or similar contexts), e.g. I know this

book. – 1 know it.

Suffix – a derivational morpheme (an affix) placed after the stem, e.g. -ness

(goodness), -less (friend less), -er (work er), etc.

Suffixal derivative – a word formed with the help of a suffix.

Suffixation – the formation of words with the help of suffixes. It is very productive in Modern English, especially so in noun and adjective word-formation, e.g.

actor, thirsty, etc.

Synchronic approach (in lexicology) – the approach concerned with the vocabulary of a language as it exists at a given time, for instance at the present time, the previous stages of development considered irrelevant.

Syncope – medial clipping, i.e. the formation of the word by the omission of the middle part of the word, e.g. fancy from fantasy, specs from spectacles, etc. Synecdoche – a type of metonymy consisting in the substitution of the name of a

whole by the name of some of its parts or vice versa, e.g. a hand – a worker, employee, etc.

Synonymic dominant – the most general word in a given group of synonyms, e.g.

red, purple, crimson; doctor, physician, surgeon; to leave, abandon, depart. Synonymic set – a group of synonyms, e.g. big, large, great, huge, tremendous. Synonyms – words of the same part of speech different in their sound-form but

similar in their denotational meaning and interchangeable at least in some contexts, e.g. to look, to seem, to appear; high – tall, etc., see absolute or total, complete, ideographic, stylistic synonyms.

Syntactic compounds – compounds whose components are placed in the order that conforms to the rules of Modern English syntax, e.g. a know-nothing, a blackboard, daytime, etc. (cf. to know nothing, a black colour, spring time).

T

Telescoping — see blending.

Term – a word or word-group used to name a notion characteristic of some special field of knowledge, industry or culture, e.g. linguistic term: suffix, borrowing, polysemy, scientific term: radius, bacillus; technical term: ohm, quantum, etc.

Thematic group – a group of words belonging to different parts of speech and joined together by common contextual associations, e.g. sea, beach, sand, wave, to swim, to bathe, etc., they form a thematic group because they denote sea-objects.

Transform — the result of transformation, see next.

Transformation(al) analysis in lexicology – the method in which the semantic similarity or difference of words (phrases) is revealed by the possibility of transforming them according to a prescribed model and following certain rules

into a different form, e.g. daily – occurring every day, weekly – occurring every week, monthly – occurring every month, see lexical transformation.

Translation loans (loan-translations) – words and expressions formed from the material available in English by way of literal word-for-word or morpheme-for- morpheme translation of a foreign word or expression (i.e. formed according to patterns taken from another language), e.g. masterpiece (cf. German Meisterwerk); it goes without saying (cf. French cela va sans dire), etc.

U

Umlaut (syn. vowel mutation) – a partial assimilation to a succeeding sound, one of the causes of sound interchange, e.g. food – feed, blood – bleed, see sound interchange.

Unmotivated – see motivated (phrase, word).

Unproductive – see productive; also see affix, prefix, suffix.

Ultimate constituents (UC’s) – all the morphemes of a word (i.e. constituents incapable of further division into any smaller elements possessing sound form and meaning). The term is usually used in morphemic and IC‟s analysis of word- structure.

V

Valency (valence) – the combining power or typical cooccurrence of a linguistic element, i.e. the types of other elements of the same level with which it can occur; see lexical valency. Kinds of valency: lexical valency – the aptness of a word to occur with other words, grammatical valency — the aptness of a word to appear in specific syntactic structures.

Valency of affixes – the types of stems with which they occur.

Variants (of some language) – regional varieties of a language possessing literary form, e.g. Scottish English, British English, American English, see dialect.

Vocabulary – the system formed by the sum total of all the words and word equivalents of a language.

W

Word – a fundamental autonomous unit of language consisting of a series of phonemes and conveying a certain concept, idea or meaning, which has gained general acceptance in a social group of people speaking the same language and historically connected (one of general definitions); another definition – a basic autonomous unit of language resulting from the association of a given meaning with a given group of sounds which is susceptible of a given grammatical employment and able to form a sentence by itself. Kinds of words: archaic, borrowed, cognate, compound, derived, form, homonymous, international, monomorphic, monosemantic, motivated, native, non-motivated (unmotivated), notional, obsolete, onomatopoeic, polymorphic, polysemantic, root, synonymous.

Word-composition (also composition or compounding) – the way of forming new words by putting two or more stems together to build a new word. Composition is very productive in Modern English. It is mainly characteristic of noun and

adjective formation, e.g. headache, typewriter, killjoy, somebody, mother-in-law, wastepaper basket, Anglo-Saxon; pitch-dark, home-made, etc

Z

Zero-derivation – see conversion.

Zero-morpheme – see conversion.

Zoosemy – nicknaming from animals, i.e. when names of animals are used metaphorically to denote human qualities, e.g. a tiger stands for a cruel person, a fox stands for a crafty person, a chicken stands for a lively child, an ass or a goose stands for a stupid person, a bear stands for a clumsy person, etc.

|

Обзор компонентов Multisim Компоненты – это основа любой схемы, это все элементы, из которых она состоит. Multisim оперирует с двумя категориями… |

Композиция из абстрактных геометрических фигур Данная композиция состоит из линий, штриховки, абстрактных геометрических форм… |

Важнейшие способы обработки и анализа рядов динамики Не во всех случаях эмпирические данные рядов динамики позволяют определить тенденцию изменения явления во времени… |

ТЕОРЕТИЧЕСКАЯ МЕХАНИКА Статика является частью теоретической механики, изучающей условия, при которых тело находится под действием заданной системы сил… |

|

Типовые ситуационные задачи. Задача 1. Больной К., 38 лет, шахтер по профессии, во время планового медицинского осмотра предъявил жалобы на появление одышки при значительной физической Типовые ситуационные задачи. Задача 1.У больного А., 20 лет, с детства отмечается повышенное АД, уровень которого в настоящее время составляет 180-200/110-120 мм рт Задача 1.У больного А., 20 лет, с детства отмечается повышенное АД, уровень которого в настоящее время составляет 180-200/110-120 мм рт. ст. Влияние психоэмоциональных факторов отсутствует. Колебаний АД практически нет. Головной боли нет. Нормализовать… Эндоскопическая диагностика язвенной болезни желудка, гастрита, опухоли Хронический гастрит — понятие клинико-анатомическое, характеризующееся определенными патоморфологическими изменениями слизистой оболочки желудка — неспецифическим воспалительным процессом… |

Terms can be defined as linguistic designations of specialized concepts [5, p. 80]. They are more precise than non-terms and belong to systems of terms that correspond to concept systems. Traditionally, terms are associated with nouns, even though adjectives, verbs, and adverbs may also be terms. Term formation mainly follows the same rules as does general language vocabulary.

Term formation can be carried out in a specific environment, e.g. in a research laboratory, in a manufacturing company, at a conference, in a small enterprise, etc. Usually, term formation is influenced by the subject field in which it carried out, by the nature of the persons involved in the process of designation, by the stimulus causing the term formation, and of course, by the phonological, morphosyntactical and lexical structures of the language.

According to Sager, two types of term formation can be distinguished in relation to pragmatic circumstances of their creation: primary term formation and secondary term formation [2, p. 5]. Primary creation accompanies the formation of a concept and is monolingual. Secondary term formation occurs when a new term is created for an existing concept in the following two cases:

- as a result of the revision of a term in the framework of a single monolingual community, e.g. creation of a term in the concept of a normative document (standard) or rebaptism of a term as a result of the discovery of a new entity in the same subject field(e.g. “telephone” is now referred to as “fixed telephone” following the discovery of the “mobile telephone”);

- as a result of transferring knowledge to another linguistic community in which a corresponding terms needs to be created.

Primary and secondary term creation are governed by different motives and show the following differences:

in the case of primary term formation of a term there is no pre-existing linguistic entity, even though appropriate term formation rules exist. With secondary term formation, there is always an already existing term, which is the term of the source language, and which can serve as the basic for secondary formation;

primary formation is often quite spontaneous, whereas secondary formation is more frequently subject to rules and can be planned.

Terms are the linguistic representation of concepts. However, contrary to the situation prevailing in general language, where the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign is fully acceptable, special languages endeavor to make the process of designation systematic, based on certain specified linguistic rules, so that terms reflect the concept characteristics they refer to as precisely as possible. The aim of systematization of these principles is to achieve transparency and consistency in linguistic representation of knowledge. The following general linguistic schemes serve both of these principles:

- use of nouns derived from verbs with specific endings to designate concept which mean procedures and methods, e.g. “slic-ing”, “recycle-ing”, “evapora-tion”,etc;

- use of nouns derived from adjectives, as opposed to adjectives more frequently occurring in general language, in order to designate properties, qualities and states, e.g. “elastici-ty”, “conductivi-ty”,”shallow-ness”, etc;

- use of identical endings when terms are formed to name species or new parts in the same subject fields: “hard-ware”, “soft-ware”, “share-ware”, “free-ware”;