History

The etymology of getting it on.

Eons before Salt-N-Pepa recorded their boundary-pushing hit, humans have been talking about sex—but the ways we’ve done so have invariably shifted over time. From the Biblical sense of ‘knowing someone’ to more modern synonyms for sex (anyone care to do the devil’s dance?), our language around intimacy has shifted just as the taboos around it have, too.

Early origins

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “sex” itself stems from Old French, with an origin around 1200. At that time, the word simply referred to genitals. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century when it was first used to refer to the act of intercourse, and this usage became more popular in the earlier 20th century. So how did we refer to the act before then?

Latin roots

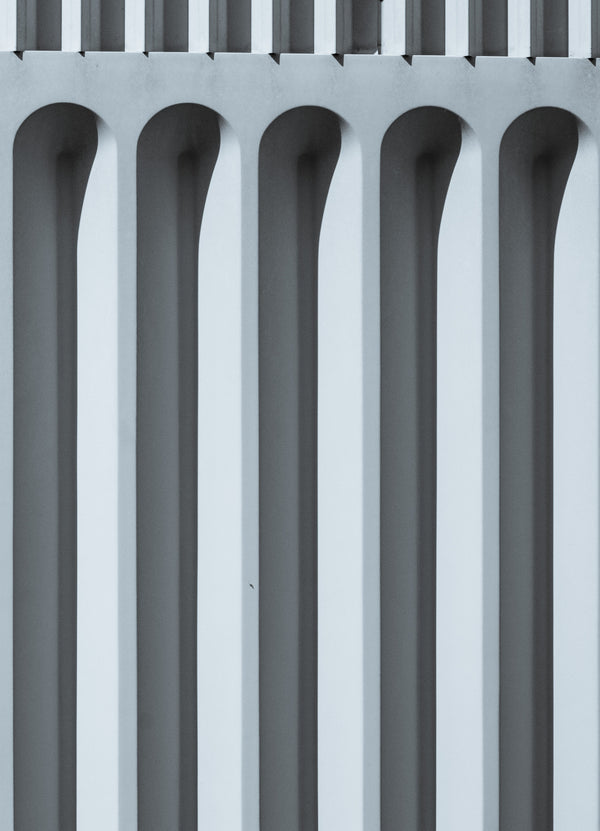

Well, around 1300, the word “fornication” arose, also from Old French’s “fornicacion,” which has the Latin root “fornix,” which means “arch.” So the story goes: prostitutes in ancient Rome hung out under vaulted ceilings, which gave this seemingly standard architectural word a risqué connotation—and this root is also why the word fornication is strictly used to refer to two people who are not married to one another.

Biblical sense

While the Bible’s use of “knowing” seems to stretch long across time, this word usage originates around 1200, from translations of Genesis in the Old Testament: Adam knew his wife, Eve. And now, centuries later, we use this euphemism cheekily, adding “in the biblical sense” as a tag on to a passing remark.

The f-word

It might come as a surprise that the seemingly most modern way we refer to coitus—good old “fuck”—has a centuries-long history, too. According to Dictionary.com, this word was first recorded in a dictionary in 1598, and has Old Germanic roots in the word ficken or fucken—which means to “strike or penetrate” and Latin roots in words that translate roughly “to prick or puncture.” The word was relatively common at its origin, but by the 18th century, came to be considered vulgar, and it was even banned from the Oxford English Dictionary. In 1960, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, the word started to lose at least a little bit of its taboo, thanks to the often-banned novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence, which uses the word frequently enough that its publishers had to go to court to have it ruled fair for publication.

Shakespeare’s innuendos

Over time, there are countless other words we’ve used to describe getting it on, from Shakespeare’s countless innuendos (stabbed, fubbed off), to 1650’s development of the word “come,” which has been used cheekily pretty much ever since. If one thing’s clear from history, no single word can ever seem to do the act justice.

Related Products

Related

Wiki User

∙ 14y ago

Best Answer

Copy

It is a word used to describe the activities associated with

procreation (intercourse)or as a means of defining gender groups.

(Male and Female).

Wiki User

∙ 14y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Why is sex a word?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

«Sex» redirects here. For other uses, see intimacy (regarding sex acts), or romantic and sexual orientations (regarding sexuality).

| |

Content warningThis article mentions discrimination, and educational talk about genitals. If you are not comfortable with reading about this kind of topic, we suggest you take a step back. |

Sexes are a system of categories, a way of putting kinds of bodies into categories. Living things of many species evolved to be specialized into their own male, female, and intersex kinds, each known as a sex. A sex is generally determined by reproductive body parts. In humans, these imply— but do not prove— a correlation with chromosomes. In gender studies, the sex and gender of a person are thought of as two distinct things: sex is about the body, whereas gender is about the self. What most people mean when they talk about someone’s sex is their assigned gender at birth.

Distinction between sex and gender[edit | edit source]

The distinction between sex and gender differentiates a person’s biological sex (the anatomy of an individual’s reproductive system, and secondary sex characteristics) from that person’s gender, which can refer to either social roles based on the sex of the person (gender role) or personal identification of one’s own gender based on an internal awareness (gender identity).[1][2] In this model, the idea of a «biological gender» is an oxymoron: the biological aspects are not gender-related, and the gender-related aspects are not biological. In some circumstances, an individual’s assigned sex and gender do not align, and the person may be transgender.[1] In other cases, an individual may have biological sex characteristics that complicate sex assignment, and the person may be intersex.

The sex and gender distinction is not universal. In ordinary English, sex and gender are often used interchangeably.[3][4] Some dictionaries and academic disciplines give them different definitions while others do not. Some languages, such as German or Finnish, have no separate words for sex and gender, and the distinction has to be made through context. On occasion, using the English word gender is appropriate.[5][6]

Among scientists, the term sex differences (as compared to gender differences) is often used for sexually dimorphic traits that are thought to be evolved results of sexual selection.[7][8]

Biological essentialism[edit | edit source]

The form of sexism called biological essentialism is the belief that your body is the main thing that makes you who you are. It is supposed to define you forever, no matter what you change about yourself, think about yourself, or anything. It says the gender you were assigned at birth must be your only real gender. Biological essentialism is used to justify most forms of sexism. It is harmful to virtually everyone, of any sex or gender.[9] Some transgender exclusionists use biological essentialism to discriminate against transgender and nonbinary people.

Assigned gender at birth[edit | edit source]

The «Phall-O-Meter» is a satirical measure that critiques the medical standard of assigning sex at birth solely based on the size of a newborn’s phallus.

When people speak of a person’s «sex», usually what they really mean is their assigned gender at birth. This is because a person’s sex is much more difficult to determine than most people believe. For example, chromosomes are part of defining someone’s sex, but most people never get their chromosomes tested. A baby’s assigned gender at birth is based on only one thing: the presence or absence of what a doctor thinks is probably a penis. This will be the only basis of that child’s legal gender. As the person grows up, the doctor’s guess about their sex can turn out to be wrong, because some intersex conditions only become clear once a person has gone through puberty. Even then, the person might have unusual chromosomes or internal reproductive organs without ever knowing about it.

«Sex identity» can mean either how a person categorizes their own physical sex,[10][11] or it can mean how other people categorize that person’s sex.[12]

Some activists advocate for society to cease assigning gender at birth. For example, author and lawyer Martine Rothblatt wrote: «As we gradually free ourselves from stamping newborn babies as one sex or the other, gender expectations will become self-defining and the full cultural liberation of all people can occur at last.»[13] In 2020, several MDs published an opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine stating that «Sex designations on birth certificates offer no clinical utility, and they can be harmful for intersex and transgender people. Moving such designations below the line of demarcation wouldn’t compromise the birth certificate’s public health function but could avoid harm.»[14]

Other phrasing[edit | edit source]

People writing about gender use several different phrases to refer to assigned gender at birth. Some of them are more accurate and respectful than others. This list gives some of these phrases.

- Assigned Gender At Birth (AGAB). Most people are either Assigned Female At Birth (AFAB) or Assigned Male At Birth (AMAB). This is an accurate and respectful phrase.

- Gender Assigned At Birth (GAAB) is a different word order for the above phrase, with the same meaning. This makes Female Assigned At Birth (FAAB), and Male Assigned At Birth (MAAB).

- Designated Gender At Birth (DGAB). Most people are either Designated Female At Birth (DFAB) or Designated Male At Birth (DMAB). This phrase is used interchangeably with AGAB, with much the same meaning.

- Coercively Assigned Gender At Birth (CAGAB). Most people are either Coercively Assigned Female At Birth (CAFAB) or male (CAMAB). Unlike AGAB and GAAB, CAGAB emphasizes that the gender was assigned against the person’s will, and implies that the person was abused as a child. People disagree about who gets to say their gender was coercively assigned. Some say only intersex people can call themselves CAGAB, and that the coercion refers to non-consensual practices such as genital surgery given to intersex infants to make their genitals «normal.» However, many children who aren’t intersex also have a gender role assigned to them by means of coercion and abuse. For example, some parents put gender non-conforming and transgender children through «conversion therapy» to make the children conform to their assigned gender.

The next list of phrases gives those that aren’t as accurate or respectful. Please use one of the above phrases instead of them.

- Biological sex (biological girl, biological boy) isn’t a good phrase for talking about assigned gender or sex. For example, although a typical transgender woman was assigned male at birth, it could offend her to call her a biological male. She’s not a non-biological woman or a robot. Because she is a woman, she might not consider herself to have a «male biology». It would be more tactful to describe her as AMAB. Even more tactful, no direct explicit reference to her assigned gender at birth at all, and simply say that she is a trans woman.

- Genetic girl and genetic boy aren’t good things to call someone, for similar reasons as «biological sex». «Genetic» refers to chromosomes, but doctors usually don’t check babies’ chromosomes at birth. During pregnancy, some OBGYN practices offer fetal genetic testing and use the sex chromosome result to assign a gender, but chromosomes aren’t part of how gender is assigned at birth. Even adults only rarely get to find out what their chromosomes are. Doctors only do that test if they think it might answer questions certain kinds of challenges with health and fertility. Intersex conditions prove that there is no guarantee that a person’s assigned gender might match their chromosomes.

- Natal sex (as in natal female and natal male). This means the sex that a person supposedly had when they were born.[12] Because of the problems in determining a baby’s actual sex, a more accurate phrase is «assigned at birth» or one of its variants.

Dyadic sexes[edit | edit source]

Dyadic means «not intersex.» The dyadic sexes are male and female, with no noticable intersex characteristics. Dyadic sexes should not be confused with cisgender or binary gender.

There is some controversy around the usage of the term «dyadic.»[15][16] Dyad means two, so dyadic promotes the idea of a dualism for sex: male and female. Although well intended, it may fall short of deconstructing binary of sex and acknowledging the complexity of human biology. Other common terms for «not intersex» are perisex[17][18] and endosex[19][20], which avoid this binary implication. Other proposed terms, which have not gained much use, include intrasex and juxtasex.[16]

Assigned female at birth[edit | edit source]

Assigned Female At Birth (AFAB), also called Female Assigned At Birth (FAAB), or Designated Female At Birth (DFAB). The term Coercively Assigned Female At Birth (CAFAB) means the same, but with additional nuances. Less accurate or respectful terms for this are biological female, genetic girl, and natal female.

When a person is born, a doctor will say the baby is female based on this one criteria: the absence of a penis, or rather, or a clitoris smaller than a certain size. The doctor doesn’t check the baby for the presence of a vagina, so sometimes the absence of this is missed. Some people with intersex conditions who were AFAB only discover they don’t have a vagina once they are older. The doctor also doesn’t check the baby’s chromosomes to assign a female gender, so a person who was AFAB doesn’t necessarily have XX chromosomes.

A person who was AFAB usually but doesn’t necessarily consider their sex to be female. Being AFAB doesn’t mean that a person necessarily has a female gender identity, which is the main criteria for someone being female. Being AFAB doesn’t necessarily mean that someone is a person perceived as a woman (PPW).

Transgender people who were AFAB are usually assumed to be transgender men. However, some transgender people who were AFAB are nonbinary, not trans men. Transgender people who were AFAB can be said more broadly to be on the transmasculine spectrum, which can include some AFAB nonbinary people, and AFAB butches. However, the umbrella term of transmasculine doesn’t include transgender people who were AFAB who don’t think of themselves as masculine.

A few of the physical characteristics of a person who was AFAB often include:

- A uterus, ovaries, and vagina, unless if they were born without one or another of them (agenesis), or had them removed (hysterectomy, oophorectomy, or vaginectomy, respectively) to treat or prevent disease

- The ability to give birth, unless if sterile, or without some of the anatomy listed above, or past childbearing years

- Breasts (a secondary sexual characteristic), unless if they never developed, or they had them removed (mastectomy) to treat or prevent breast cancer

- Has a hormone balance with estrogen higher than testosterone, and the presence of progesterone

- Chromosomes that are XX (textbook example), XY (androgen insensitivity syndrome/swyer syndrome), XXX (triple X syndrome), XXXX, X (Turner syndrome), or others. People rarely take a test to find out what these are, unless if they think it might explain another physical challenge.

It is possible for an AFAB person to have a body with few of the physical characteristics that are usually used to describe a typical cisgender female body.

Assigned male at birth[edit | edit source]

Assigned Male At Birth (AMAB), also called Male Assigned At Birth (MAAB), or Designated Male At Birth (DMAB). The term Coercively Assigned Male At Birth (CAMAB) means the same, but with additional nuances. Less accurate or respectful terms for this are biological male, genetic boy, and natal male.

When a person is born, a doctor will say the baby is male based on this one criteria: the presence of a penis or a clitoris over a certain size. The doctor doesn’t check the baby for the absence of a vagina, so sometimes the presence of this is missed. Some people with intersex conditions who were AMAB only discover they have a vagina once they are older. The doctor also doesn’t check chromosomes, so a person who was AMAB doesn’t necessarily have XY chromosomes.

Transgender people who were AMAB are usually assumed to be transgender women. However, some transgender people who were AMAB are nonbinary, not trans women. Transgender people who were AMAB can be said more broadly to be on the trans feminine spectrum, which can include some AMAB nonbinary people. However, the umbrella term of trans feminine doesn’t include transgender people who were AMAB who don’t think of themselves as feminine.

A few of the physical characteristics of a person who was AMAB often include:

- No vagina or uterus. However, some people who were AMAB were born with one or another of them (persistent Müllerian duct syndrome). Some only find out they have a uterus if they have scans or surgery on their abdomen for other reasons, or if they menstruate.

- Descended testes and scrotum, although sometimes testes never descend (cryptorchid), or are removed to treat or prevent disease

- Penis or large clitoris. With some intersex conditions, the difference between these can be unclear.

- Chromosomes that are XY (textbook example), XX (de la Chapelle syndrome), XXY (Klinefelter’s syndrome), XXYY, or others.

It is possible for a person who was AMAB to have a body with few of the physical characteristics that are usually used to describe a typical cisgender male body.

Intersex conditions[edit | edit source]

Intersex Awareness Day in Brussels, 2018.

See main article: intersex.

Intersex people are people born with any variation in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals that do not fit the typical definitions of male or female bodies.[21]

Because intersexuality is about the kind of body that someone is born with, not how they identify, intersex is not a gender, and is not the same thing as nonbinary. However, some intersex people can consider their gender identity to simply be «intersex.»

An intersex person may have any gender identity. An intersex person doesn’t necessarily identify as intersex, and may instead prefer to be called a man or woman. Or an intersex person may agree with their assigned gender; in this case, they would be described as either ipsogender or cisgender. Intersex people may think of themselves as cisgender, transgender, genderqueer, nonbinary, etc. An intersex person who feels that their intersex status has influenced their gender identity may identify as intergender. Some intersex people think of their intersex status as belonging to the broader range of LGBT identities.

People who identify as nonbinary aren’t necessarily intersex, and instead may be dyadic (meaning not intersex).

Discrimination against intersex people[edit | edit source]

«Dyadism» is a common kind of sexism. As a concept, dyadism is the incorrect belief that humans are strictly dyadic, having only two sexes. In action, dyadism is discrimination against intersex people. That discrimination can include erasure, harassment, medical malpractice, lack of marriage rights, religious intolerance, human rights violations, and hate crimes against intersex people. Dyadism is also the basis of other forms of sexism, including binarism, the belief that people have only two genders.

Because of dyadism, doctors think of intersex conditions as an irregularity. As a result, intersex people were given so-called «normalizing» or «corrective» surgeries, often at a very young age, and without their consent.

Sexes of nonhuman animals[edit | edit source]

A Common Blue (Polyommatus icarus) individual that is a gynandromorph, having a female form on one side and male on the other. Gynandromorphs occur in some animal species.

One common misconception is that all animals have only male and female sexes. However, nature is much more complex and varied. Many animal species are known to have a variety of intersex conditions, or very different kinds of sexes than occur among humans. For example: male seahorses that get pregnant, fish that change sex if there aren’t enough of a particular sex in their group, female deer with antlers, lionesses with manes, lizards that lay fertile eggs after two females mate together (parthenogenesis), hyenas that give birth through an organ that is nearly indistinguishable from a penis, and so on. Most animals don’t have sex chromosomes that are the same as the XX or XY set that are most common in humans. Learning about the diversity of animal sexes can help one recognize how much the sexes are an idea constructed by humans to describe and simplify reality, but our understanding of that reality tends to be limited by our own sexual stereotypes widespread in our culture.

To learn more about the diversity of animal sexes, read Joan Roughgarden’s book, Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People (2009).

See also[edit | edit source]

- Intimacy

- Sexism

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prince, Virginia. 2005. «Sex vs. Gender.» International Journal of Transgenderism. 8(4).

- ↑ Neil R., Carlson. Psychology: The science of behavior. Fourth Canadian edition. isbn 978-1-57344-199-5. Pearson, 2010. P. 140–141

- ↑ Udry, J. Richard (November 1994). «The Nature of Gender» (PDF). Demography. 31 (4): 561–573. doi:10.2307/2061790. JSTOR 2061790. PMID 7890091. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-11. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ↑ Haig, David (April 2004). «The Inexorable Rise of Gender and the Decline of Sex: Social Change in Academic Titles, 1945–2001» (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 33 (2): 87–96. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.359.9143. doi:10.1023/B:ASEB.0000014323.56281.0d. PMID 15146141. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2011. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ↑ Bograd, Michele; Weingarten, Kaethe (28 January 2015). «Reflections on Feminist Family Therapy Training». EBL-Schweitzer. New York: Routledge: 69. ISBN 978-1-317-72776-7. OCLC 906056635. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ↑ «Peruskäsitteet». Archived from the original on 2018-05-08. Retrieved 2018-02-11. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) (in Finnish)

- ↑ Mealey, L. (2000). Sex differences. NY: Academic Press.

- ↑ Geary, D. C. (2009) Male, Female: The Evolution of Human Sex Differences. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association

- ↑ Weiss, Suzannah (13 March 2017). «How Gender Essentialism Hurts Us All». Bustle. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ↑ «LGBTQI Terminology.» [1] [Dead link]

- ↑ «LGBT resources: Definition of terms».

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 «Trans, Genderqueer, and Queer Terms Glossary» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2017.

- ↑ «Gender Manifesto: a selection from The Apartheid of Sex». TV/TS Tapestry Journal. International Foundation for Gender Education (71): 33. Spring 1995.

- ↑ Shteyler, Vadim M.; Clarke, Jessica A.; Adashi, Eli Y. (2020). «Failed Assignments — Rethinking Sex Designations on Birth Certificates». New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (25): 2399–2401. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2025974. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Astorino, Claudia (10 September 2012). ««Dyadic»?». Full-Frontal Activism: Intersex and Awesome.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 «I’m sorry if this is bad to ask but why is dyadic a bad term to use?». To Cultivate an Ally. 27 October 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Lanquist, L.A. «Definitions». Trans Narrative. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ «What tf is perisex». Correcting Bisexuality Definitions One at a Time. 17 July 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ «What is intersex?». Intersex Human Rights Australia. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Mx. Anunnaki Ray Marquez (12 December 2019). «Biological and Anatomical Sex: Endosex, Intersex & Altersex». Retrieved 19 June 2020.

I prefer to use the word endosex to describe people who were not born intersex. In the past ‘dyadic’ was used for this same purpose. The very word ‘dyadic’ implies that only two sex exist which is not accurate if we are to respect intersex existence.

- ↑ «Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex» (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

I can only thoroughly explain this for one language, namely Hindi, and perhaps by extension other North Indian languages.

For socio-linguistic reasons, Hindi speakers are inclined to communicate taboo and uncomfortable subjects in English since it creates emotional distance between themselves and the subject matter. It comes off as more «objective» or «impersonal.»

Of course, however, this specific example is also dependent on the history of British colonialism and the resultant exchanges between English and Indic languages.

Generally, I would just say that English medical terms tend to become loan words because, well, English-speaking researchers and countries dominate the sciences.

There is also the pervasiveness of English media. The term ‘sex’ probably comes up in a lot of songs and TV shows that are popular all over the world, making it easily recognizable and memorable.

“If only I could feel about sex as I do about writing!” young Susan Sontag wrote in her diary. “That I’m the vehicle, the medium, the instrument of some force beyond myself.” Cultivating such a symphonic relationship with one’s sexuality is a lifelong struggle for many, with a score composed during our earliest experiences of getting to know our bodies in relation to ourselves and others. To imbue those formative years with confident and friendly curiosity rather than shame and judgment is perhaps the single most important factor in becoming that instrument.

Half a century after two Danish schoolteachers published the first honest and intelligent guide to teenage sexuality as “a protest against the Victorian/authoritarian school system,” sex educator Cory Silverberg and illustrator Fiona Smyth offer a magnificent contemporary counterpart in Sex is a Funny Word: A Book about Bodies, Feelings, and You (public library). A follow-up to Silverberg and Smyth’s marvelous illustrated guide to the modern family, this candid, inclusive, stereotype-defying, and absolutely wonderful primer on sexuality and gender identity embraces diversity in all of its dimensions.

The book’s four protagonists, who represent a colorful range of ethnicities and fall on various points of the gender-identity and orientation continuum, guide the reader through the complexities of crushes, kissing, touching, puberty, masturbation, and many more mazes of the sexual ripening journey. With the playfulness of the comic genre and the solidity of thoughtful sex education, Silverberg and Smyth strip this universal coming-of-age process of its cultural baggage and celebrate the openminded, openhearted spirit of discovery so vital to fostering a healthy relationship with sexuality and a lifelong respect for one’s own body.

Most boys are born with a penis and scrotum, and most girls are born with a vulva, vagina, and clitoris.

But having a penis isn’t what makes you a boy. Having a vulva isn’t what makes you a girl.

The truth is much more interesting than that!

Maybe you’re called a boy but you know you’re a girl. You know how girls are treated and what they do. That’s how you want to be treated and what you want to do.

Maybe you’re called a girl but feel like a boy. You know how boys are treated and what they do. That’s how you want to be treated and what you want to do.

Maybe you aren’t sure, or don’t care that much. Maybe you feel like both. Maybe you just need some time to figure it out, without all the boy and girl stuff.

Because everyone’s bodies are different, all our feelings are different too.

Part of being a kid is learning what you like, what you don’t like, and who you are. That’s part of being a grown-up too. We never stop learning or changing.

Touching isn’t just something we do with other people. We also touch ourselves.

We touch ourselves all the time, in all kinds of places, for all kinds of reasons.

Touching yourself is one way to learn about yourself, your body, and your feelings.

You may have discovered that touching some parts of your body, especially the middle parts, can make you feel warm and tingly.

Grown-ups call this kind of touch masturbation.

Masturbation is when we touch ourselves, usually our middle parts, to get that warm and tingly feeling.

A crush is a special kind of feeling you have for another person. You can have a crush on any kind of person. You can have a crush on a friend or on someone you just met. You can even have a crush on someone you have never met.

Not everyone has crushes. If you do, the first time can be surprising, and can feel a bit strange.

You might think about them a lot. You might want to spend all your time with them if you could.

Just thinking about them can make you happy and nervous. When you are around them, you may feel excited, or awkward, or both.

There’s no right or wrong way to have a crush.

Complement the intelligent and inclusive Sex is a Funny Word with Kurt Vonnegut’s favorite vintage illustrated guide to sexuality and these wonderful LGBT children’s books that help kids make sense of their orientation and identity, then revisit Silverberg and Smyth’s equally delightful What Makes a Baby.

Artwork courtesy of Cory Silverberg and Fiona Smyth