This article is about the representation of a thing or abstraction as a person. For the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities, see Anthropomorphism.

Personification is the representation of a thing or abstraction as a person. In the arts, many things are commonly personified. These include numerous types of places, especially cities, countries, and continents, elements of the natural world such as the months or four seasons, four elements,[1] four cardinal winds, five senses,[2] and abstractions such as virtues, especially the four cardinal virtues and seven deadly sins,[3] the nine Muses,[4] or death.

In many polytheistic early religions, deities had a strong element of personification, suggested by descriptions such as «god of». In ancient Greek religion, and the related ancient Roman religion, this was perhaps especially strong, in particular among the minor deities.[5] Many such deities, such as the tyches or tutelary deities for major cities, survived the arrival of Christianity, now as symbolic personifications stripped of religious significance. An exception was the winged goddess of victory, Victoria/Nike, who developed into the visualisation of the Christian angel.[6]

Generally, personifications lack much in the way of narrative myths, although classical myth at least gave many of them parents among the major Olympian deities.[7] The iconography of several personifications «maintained a remarkable degree of continuity from late antiquity until the 18th century».[8] Female personifications tend to outnumber male ones,[9] at least until modern national personifications, many of which are male.

Sandro Botticelli, Calumny of Apelles (c. 1494–95), with 8 personification figures: (from left) Hope, Repentance, Perfidy, innocent victim, Calumny, Fraud, Rancour, Ignorance, the king, Suspicion.

Personifications are very common elements in allegory, and historians and theorists of personification complain that the two have been too often confused, or discussion of them dominated by allegory. Single images of personifications tend to be titled as an «allegory», arguably incorrectly.[10] By the late 20th century personification seemed largely out of fashion, but the semi-personificatory superhero figures of many comic book series came in the 21st century to dominate popular cinema in a number of superhero film franchises.

According to Ernst Gombrich, «we tend to take it for granted rather than to ask questions about this extraordinary predominantly feminine population which greets us from the porches of cathedrals, crowds around our public monuments, marks our coins and our banknotes, and turns up in our cartoons and our posters; these females variously attired, of course, came to life on the medieval stage, they greeted the Prince on his entry into a city, they were invoked in innumerable speeches, they quarrelled or embraced in endless epics where they struggled for the soul of the hero or set the action going, and when the medieval versifier went out on one fine spring morning and lay down on a grassy bank, one of these ladies rarely failed to appear to him in his sleep and to explain her own nature to him in any number of lines».[11]

History[edit]

Classical world[edit]

Personification as an artistic device is easier to discuss when belief in the personification as an actual spiritual being has died down;[12] this seems to have happened in the ancient Graeco-Roman world, probably even before Christianisation.[13] In other cultures, especially Hinduism and Buddhism, many personification figures still retain their religious significance, which is why they are not covered here. For example Bharat Mata was devised as a Hindu goddess figure to act as a national personification by intellectuals in the Indian independence movement from the 1870s, but now has some actual Hindu temples.[14]

Personification is found very widely in classical literature, art and drama, as well as the treatment of personifications as relatively minor deities, or the rather variable category of daemons.[15] In classical Athens, every geographical division of the state for local government purposes had a personified deity which received some cultic attention, as well as Demos, a male personification for the governing assembly of free citizens, and Boule, a female one for the ruling council. These appear in art, but are often hard to identify if not labelled.[16]

Personification in the Bible is mostly limited to passing phrases which can probably be regarded as literary flourishes,[17] with the important and much-discussed exception of Wisdom in the Book of Proverbs, 1–9, where a female personification is treated at some length, and makes speeches.[18] The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation can be regarded as personification figures, although the text does not specify what all personify.[19]

According to James J. Paxson in his book on the subject «all personification figures prior to the sixth century A.D. were … female»;[20] but major rivers have male personifications much earlier, and are more often male, which often extends to «Water» in the Four Elements.[21] The predominance of females is at least partly because Latin grammar gives nouns for abstractions the female gender.[22]

Pairs of winged victories decorated the spandrels of Roman triumphal arches and similar spaces, and ancient Roman coinage was an especially rich source of images, many carrying their name, which was helpful for medieval and Renaissance antiquarians. Sets of tyches representing the major cities of the empire were used in the decorative arts.[23] Most imaginable virtues and virtually every Roman province was personified on coins at some point, the provinces often initially seated dejected as «CAPTA» («taken») after its conquest, and later standing, creating images such as Britannia that were often revived in the Renaissance or later.[24]

Lucian (2nd century AD) records a detailed description of a lost painting by Apelles (4th century BC) called the Calumny of Apelles, which some Renaissance painters followed, most famously Botticelli. This included eight personifications of virtues and vices: Hope, Repentance, Perfidy, Calumny, Fraud, Rancour, Ignorance, Suspicion, as well as two other figures.[25]

Platonism, which in some manifestations proposed systems involving numbers of spirits,[26] was naturally conducive to personification and allegory, and is an influence on the uses of it from classical times through various revivals up to the Baroque period.

Literature[edit]

According to Andrew Escobedo, “literary personification marshalls inanimate things, such as passions, abstract ideas, and rivers, and makes them perform actions in the landscape of the narrative.”[27] He dates “the rise and fall of its [personification’s] literary popularity” to «roughly, between the fifth and seventeenth centuries».[28] Late antique philosophical books that made heavy use of personification and were specially influential in the Middle Ages included the Psychomachia of Prudentius (early 5th century), with an elaborate plot centred around battles between the virtues and vices,[29] and The Consolation of Philosophy (c. 524) by Boethius, which takes the form of a dialogue between the author and «Lady Philosophy». Fortuna and the Wheel of Fortune were prominent and memorable in this, which helped to make the latter a favourite medieval trope.[30] Both authors were Christians, and the origins in the pagan classical religions of the standard range of personifications had been left well behind.

A medieval creation was the Four Daughters of God, a shortened group of virtues consisting of: Truth, Righteousness or Justice, Mercy, and Peace. There were also the seven virtues, made up of the four classical cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance and courage (or fortitude), these going back to Plato’s Republic, with the three theological virtues of faith, hope and charity. The seven deadly sins were their counterparts.[31]

The major works of Middle English literature had many personification characters, and often formed what are called «personification allegories» where the whole work is an allegory, largely driven by personifications. These include Piers Plowman by William Langland ( c. 1370–90), where most of the characters are clear personifications named as their qualities,[32] and several works by Geoffrey Chaucer, such as The House of Fame (1379–80). However, Chaucer tends to take his personifications in the direction of being more complex characters and give them different names, as when he adapts part of the French Roman de la Rose (13th century). The English mystery plays and the later morality plays have many personifications as characters, alongside their biblical figures. Frau Minne, the spirit of courtly love in German medieval literature, had equivalents in other vernaculars.

In Italian literature Petrach’s Triomphi, finished in 1374, is based around a procession of personifications carried on «cars», as was becoming fashionable in courtly festivities; it was illustrated by many different artists.[33] Dante has several personification characters, but prefers using real persons to represent most sins and virtues.[34]

In Elizabethan literature many of the characters in Edmund Spenser’s enormous epic The Faerie Queene, though given different names, are effectively personifications, especially of virtues.[35] The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) by John Bunyan was the last great personification allegory in English literature, from a strongly Protestant position (though see Thomson’s Liberty below). A work like Shelley’s The Triumph of Life, unfinished at his death in 1822, which to many earlier writers would have called for personifications to be included, avoids them, as does most Romantic literature,[36] apart from that of William Blake.[37] Leading critics had begun to complain about personification in the 18th century, and such «complaints only grow louder in the nineteenth century».[38] According to Andrew Escobedo, there is now «an unstated scholarly consensus» that «personification is a kind of frozen or hollow version of literal characters», which «depletes the fiction».[39]

Visual arts[edit]

Personifications, often in sets, frequently appear in medieval art, often illustrating or following literary works. The virtues and vices were probably the most common, and the virtues appear in many large sculptural programmes, for example the exteriors of Chartres Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral. In painting, both virtues and vices are personified along the lowest zone of the walls of the Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto (c. 1305),[40] and are the main figures in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government (1338–39) in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena. In the Allegory of Bad Government Tyranny is enthroned, with Avarice, Pride, and Vainglory above him. Beside him on the magistrate’s bench sit Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War, while Justice lies tightly bound below.[41] The so-called Mantegna Tarocchi (c. 1465–75) are sets of fifty educational cards depicting personifications of social classes, the planets and heavenly bodies, and also social classes.[42]

A new pair, once common on the portals of large churches, are Ecclesia and Synagoga.[43] Death envisaged as a skeleton, often with a scythe and hour-glass, is a late medieval innovation, that became very common after the Black Death. However, it is rarely seen in funerary art «before the Counter-Reformation».[44]

When not illustrating literary texts, or following a classical model as Botticelli does, personifications in art tend to be relatively static, and found together in sets, whether of statues decorating buildings or paintings, prints or media such as porcelain figures. Sometimes one or more virtues take on and invariably conquer vices. Other paintings by Botticelli are exceptions to such simple compositions, in particular his Primavera and The Birth of Venus, in both of which several figures form complex allegories.[45] An unusually powerful single personification figure is depicted in Melencolia I (1514) an engraving by Albrecht Dürer.[46] Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (c. 1545) by Agnolo Bronzino has five personifications, apart from Venus and Cupid.[47] In all these cases, the meaning of the work remains uncertain, despite intensive academic discussion, and even the identity of the figures continues to be argued over.[48]

Theory[edit]

Around 300 BC, Demetrius of Phalerum is the first writer on rhetoric to describe prosopopoeia, which was already a well-established device in rhetoric and literature, from Homer onwards.[49] Quintilian’s lengthy Institutio Oratoria gives a comprehensive account, and a taxonomy of common personifications; no more comprehensive account was written until after the Renaissance.[50] The main Renaissance humanists to deal with the subject at length were Erasmus in his De copia and Petrus Mosellanus in Tabulae de schematibus et tropis, who were copied by other writers throughout the 16th century.[51]

From the late 16th century theoretical writers such as Karel van Mander in his Schilder-boeck (1604) began to treat personification in terms of the visual arts. At the same time the emblem book, describing and illustrating emblematic images that were largely personifications, became enormously popular, both with intellectuals and artists and craftsmen looking for motifs.[52] The most famous of these was the Iconologia of Cesare Ripa, first published unillustrated in 1593, but from 1603 published in many different illustrated editions, using different artists. This set at least the identifying attributes carried by many personifications until the 19th century.[53]

From the 20th century into the 21st, the past use of personification has received greatly increased critical attention, just as the artistic practice of it has greatly declined. Among a number of key works, The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition (1936), by C. S. Lewis was an exploration of courtly love in medieval and Renaissance literature.[54]

Innovation[edit]

Sculptures Trade (male) and Tolerance (female) in Brno

The classical repertoire of virtues, seasons, cities and so forth supplied the majority of subjects until the 19th century, but some new personifications became required. The 16th century saw the new personification of the Americas, and made the four continents an appealing new set, four figures being better suited to many contexts than three. The 18th-century discovery of Australia was not so quickly followed by an addition to the set, if only for reasons of geometry; Australia is not included in the continents at the corners of the Albert Memorial (1860s). This does have a set of three-figure groups representing agriculture, commerce, engineering and manufacturing, typical of the requirements for large public schemes of the period.[55] A rather late example is the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City (1901–07), which has large groups for the four continents by the entrance, and 12 figures personifying seafaring nations from history high on the facade.

The invention of movable type printing saw Dame Imprimerie («Lady Printing Press») introduced to the pageants of Lyons, a major printing centre, along with «Typosine», a new muse of printing.[56] A large gilt-bronze statue by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, something of a specialist in «allegorical» statues, was commissioned by AT&T for the top of their New York headquarters. Since 1916 it has been titled at different times as the Genius of Telegraphy, Genius of Electricity, and since the 1930s Spirit of Communication. Shakespeare’s spirit Ariel was adopted by the sculptor Eric Gill as a personification of broadcasting, and features in his sculptures on Broadcasting House in London (opened 1932).[57]

National personifications[edit]

A number of national personifications stick to the old formulas, with a female in classical dress, carrying attributes suggesting power, wealth, or other virtues.[58]

Libertas, the Roman goddess of liberty, had been important under the Roman Republic, and was somewhat uncomfortably co-opted by the empire;[59] it was not seen as an innate right, but as granted to some under Roman law.[60] She had appeared on the coins of the assassins of Julius Caesar, defenders of the Roman republic. The medieval republics, mostly in Italy, greatly valued their liberty, and often use the word, but produce very few direct personifications. With the rise of nationalism and new states, many nationalist personifications included a strong element of liberty, perhaps culminating in the Statue of Liberty. The long poem Liberty by the Scottish James Thomson (1734), is a lengthy monologue spoken by the «Goddess of Liberty», describing her travels through the ancient world, and then English and British history, before the resolution of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 confirms her position there.[61] Thomson also wrote the lyrics for Rule Britannia, and the two personifications were often combined as a personified «British Liberty»,[62] to whom a large monument was erected in the 1750s on his estate at Gibside by a Whig magnate.[63]

But, sometimes alongside these formal figures, a new type of national personification has arisen, typified by John Bull (1712) and Uncle Sam (c. 1812). Both began as figures in more or less satirical literature, but achieved their prominence when taken in to political cartoons and other visual media. The post-revolutionary Marianne in France, official since 1792, is something of a mixture of styles, sometimes formal and classical, at others a woman of the streets of Paris personified.[64] The Dutch Maiden is one of the earliest of these figures, and was mainly visual from the start, her efforts to repulse unwelcome Spanish advances shown in 16th-century popular prints.[65]

See also[edit]

- Anthropomorphism

- Allegorical sculpture

- Heraldry

- Mascot

- Moe anthropomorphism; personification style mainly used in anime and manga

- Pathetic fallacy, the literary device involving ascribing human emotion and conduct to non-human objects in the natural world

- Tropical cyclone naming

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hall, 128–130

- ^ Hall, 122

- ^ Hall, 336–337

- ^ Hall, 216

- ^ Paxson, 6–7

- ^ Hall, 321

- ^ Hall, 216; the example here is the Muses, daughters of Apollo and Mnemosyne, herself the personification of Memory.

- ^ Hall, 128, speaking of the Four Seasons, but the same is true for example of the personification of Africa (same page).

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 5; Gombrich, 1 (of PDF)

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 2–13; Paxson, 5–6. See also Escobedo, Ch. 1

- ^ Gombrich, 1 (of PDF)

- ^ Paxson, 6–7; Escobedo, Introduction

- ^ Although given the persistence of ideas from Neoplatonism and folk religion this cannot be entirely certain. See, for example Gombrich 5–6 (on pdf)

- ^ «History lesson: How ‘Bharat Mata’ became the code word for a theocratic Hindu state».; Blurton, T. Richard, Hindu Art, p. 185, 1994, British Museum Press, ISBN 0 7141 1442 1

- ^ Escobedo, Ch. 1 on daemons

- ^ Smith, 93–105

- ^ «the mountains and the hills before you shall break forth into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands», Book of Isaiah, 55:12

- ^ Sinnott, Alica M., The Personification of Wisdom, 2017, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1351884360, 9781351884365. Subject of the whole book, but see Ch. 1

- ^ Mounce, Robert H., The Book of Revelation, 1998, 139–146, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 0802825370, 9780802825377, google books Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paxson, 6

- ^ Hall, 128, 265

- ^ Gombrich, 2 (of PDF)

- ^ The Calendar of 354 and the slightly later Esquiline Treasure provide examples, though the choice of 4th city varies between Antioch and Trier.

- ^ Sear, 36–42, 46–48, 49–51

- ^ Lightbown, Ronald, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 234, 1989, Thames and Hudson

- ^ Luc Brisson, Seamus O’Neill, Andrei Timotin, Neoplatonic Demons and Angels,1–5, 2018, Brill, ISBN 9004374981, 9789004374980, google books Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Escobedo, Ch. 1

- ^ Escobedo, Introduction

- ^ Hall, 336, with much more in Paxson.

- ^ Hall, 127–128

- ^ Hall, 336; see «Further reading» for some recent examples of the very extensive literature on these.

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 99–101

- ^ Hall, 310

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 73–77

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 121–122

- ^ «All the commonplace figures of poetry, tropes, allegories, personifications, with the whole heathen mythology, were instantly discarded» according to William Hazlitt in «On the Living Poets» in Lectures on the English Poets, 1818

- ^ Howard, John, Infernal Poetics: Poetic Structures in Blake’s Lambeth Prophecies, 22–24, 1984, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, ISBN 0838631762, 9780838631768, google books

- ^ Escobedo, Introduction

- ^ Escobedo, Ch. 1. He does not share this view. In particular, personifications mostly remain tied to a single character trait, that of embodying their quality.

- ^ Hartt, 64

- ^ Hartt, 116–119

- ^ Spangeberg K.L (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993, no 5,ISBN 0931537150

- ^ Rowe, Nina, The Jew, the Cathedral and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century, 2011, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-19744-9, ISBN 978-0-521-19744-1, google books Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hall, 94

- ^ Hartt, 332–333

- ^ Bartrum, 188

- ^ Hartt, 662

- ^ Bartrum, 188, says Melencolia I «must be the most written-about image in the history of art», but at least the Botticellis must run it close.

- ^ Paxson, 12

- ^ Paxson, 16–19

- ^ Paxson, 23

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 13–26

- ^ Hall, 337

- ^ Paxson, 1–2 and passim; Escobedo, Introduction

- ^ These were all given consideration at the highest levels. The designs for the continents had «changes [which] may (although there is no evidence of it) reflect the promptings of ‘statesmanlike’ discretion. Participation in the guidance of America’s progress was relinquished by the figure of Canada and it was left wholly to the United States. In the group of Europe, the link of olive leaves between France and England was dropped, as was the gesture indicating England’s reception of the Bible of the Reformation from Germany, and each of the national figures was more isolated. In ‘Africa’, Egypt, instead of listening to the counsels of Britain, herself instructed Nubia.» ‘Albert Memorial: The memorial’ Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, Survey of London: volume 38: South Kensington Museums Area (1975), 159–176. Accessed: 22 May 2019

- ^ Melion and Remakers, 30

- ^ Jackson, Nicola, Building the BBC: a return to form, 28, 2004, BBC

- ^ Heuer, 48–50

- ^ Sear, 39

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett, Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas, around p. 22, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199883076, 9780199883073

- ^ Higham, 59; text of Liberty online

- ^ Higham, 59–61

- ^ Green, Adrian, in Northern Landscapes: Representations and Realities of North-East England, 136-137, 2010, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 184383541X, 9781843835417, google books Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine; «Column to Liberty» Archived 2019-05-29 at the Wayback Machine, National Trust.

- ^ Heuer, 43–44, 48–50

- ^ Hubert de Vries, «The Dutch Virgin: Symbols of State of the Netherlands» Archived 2018-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

References[edit]

- Bartrum, Giulia, Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy, British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 0714126330

- Escobedo, Andrew, Volition’s Face: Personification and the Will in Renaissance Literature, 2017, University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 0268101698, 9780268101695, google books

- Gombrich, Ernst, «Personification», in R. R. Bolgar (ed.), Classical Influences in European Culture AD 500–1500, 1971, Cambridge UP, PDF

- Hall, James, Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Hartt, Frederick, History of Italian Renaissance Art, (2nd edn.)1987, Thames & Hudson (US Harry N Abrams), ISBN 0500235104

- Heuer, Jennifer, «Gender and Nationalism» in Nations and Nationalism: A Global Historical Overview, Eds Guntram H. Herb, David H. Kaplan, 2008, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1851099085, 9781851099085, google books

- Higham, John (1990). «Indian Princess and Roman Goddess: The First Female Symbols of America», Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. 100: 50–51, JSTOR or PDF

- Melion, Walter, Remakers, Bart, Personification: Embodying Meaning and Emotion, 2016, BRILL, ISBN 9004310436, 9789004310438, google books

- Paxson, James J., The Poetics of Personification, 1994, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521445396, 9780521445399, google books

- Sear, David, Roman Coins and Their Values, Volume 2, 46–48, 49–51, 2002, Spink & Son, Ltd, ISBN 1912667231, 9781912667239, google books

- Smith, Amy C., Polis and Personification in Classical Athenian Art, 2011, BRILL, ISBN 9004194177, 9789004194175, google books

Further reading[edit]

- Jennifer O’Reilly: Studies in the Iconography of the Virtues and Vices in the Middle Ages. New York/London 1988.

- Emma Stafford: Worshipping virtues. Personification and the Divine in Ancient Greece. London 2000.

- Emma Stafford, Judith Herrin (eds.): Personification in the Greek world. From Antiquity to Byzantium. Aldershot/Hampshire 2005.

- Tucker, Shawn R., The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook, 2015, Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 1625647182, 9781625647184

-

1

personification

personification [pəˏsɒnɪfɪˊkeɪʃn]

n

1) персонифика́ция, олицетворе́ние

2) воплоще́ние (of)

Англо-русский словарь Мюллера > personification

-

2

personification

Персональный Сократ > personification

-

3

personification

Англо-русский синонимический словарь > personification

-

4

personification

pə:ˌsɔnɪfɪˈkeɪʃən сущ. персонификация, олицетворение;

воплощение A personification of the phenomena of nature. ≈ олицетворение явлений природы He was regarded as the personification of the Latitudinarian spirit. ≈ Его считали воплощением свободомыслия. Syn: incarnation, embodiment

персонификация, олицетворение — * of the phenomena of nature олицетворение явлений природы (the *) воплощение — she is the * of virtue она воплощенная добродетель

personification персонификация, олицетворение;

воплощение ~ персонификацияБольшой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > personification

-

5

personification

[pə͵sɒnıfıʹkeıʃ(ə)n]

1) персонификация, олицетворение

personification of the phenomena of nature — олицетворение явлений природы

2) (the personification) воплощение

НБАРС > personification

-

6

personification

[pəˌsɔnɪfɪ’keɪʃ(ə)n]

сущ.

персонификация, олицетворение; воплощение

A personification of the phenomena of nature. — Персонификация явлений природы.

He was regarded as the personification of the Latitudinarian spirit. — Его считали воплощением свободомыслия.

Syn:

Англо-русский современный словарь > personification

-

7

personification

1. n персонификация, олицетворение

2. n воплощение

Синонимический ряд:

1. representation (noun) anthropomorphism; depiction; embodiment; incarnation; likeness; manifestation; metaphor; rendition; representation; substantiation

2. role (noun) character; impersonation; part; role

English-Russian base dictionary > personification

-

8

personification

[pə:ˌsɔnɪfɪˈkeɪʃən]

personification персонификация, олицетворение; воплощение personification персонификация

English-Russian short dictionary > personification

-

9

personification

персонификация; наделение чего-либо человеческими свойствами.

* * *

сущ.

персонификация; наделение чего-либо человеческими свойствами.

Англо-русский словарь по социологии > personification

-

10

personification

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > personification

-

11

personification

[pɜːˏsɔnɪfɪ`keɪʃ(ə)n]

персонификация, олицетворение; воплощение

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > personification

-

12

personification

noun

персонификация, олицетворение; воплощение

* * *

(n) воплощение; олицетворение; персонификация

* * *

персонификация, олицетворение; воплощение

* * *

персонификация, олицетворение, воплощение, очеловечениеper·son·i·fi·ca·tion || pɜ;r‚sɑ;nɪ;fɪ;’keɪ;ʃ;n /pɜ;ː;‚sɒ;-

* * *

олицетворение

олицетворения

* * *

персонификация

Новый англо-русский словарь > personification

-

13

personification

Англо-русский словарь по экономике и финансам > personification

-

14

personification

персонификация, олицетворение, воплощение

Англо-русский словарь по психоаналитике > personification

-

15

personification

персонификация; олицетворение; воплощение

English-Russian dictionary of technical terms > personification

-

16

personification

a metaphor that involves likeness between inanimate and animate objects (V.A.K.)

«the face of London», «the pain of ocean»

Geneva, mother of the Red Cross, hostess of humanitarian congresses for the civilizing of warfare. (J.Reed)

Notre Dame squats in the dusk. (E.Hemingway)

••

1) троп, который состоит в перенесении свойств человека на отвлечённые понятия и неодушевлённые предметы, что проявляется в валентности, характерной для существительных — названий лица (I.V.A.)

2) транспозиция, при которой явления природы, предметы или животные наделяются человеческими чувствами, мыслями, речью (антропоморфизм) (I.V.A.)

Roll on, thou dark and deep blue Ocean — roll! (G.Byron)

English-Russian dictionary of stylistics (terminology and examples) > personification

-

17

personification

олицетворение

олицетворения

English-Russian smart dictionary > personification

-

18

personification of the phenomena of nature

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > personification of the phenomena of nature

-

19

Aditi (The personification of the infinite, and mother of a group of celestial deities, the Adityas)

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > Aditi (The personification of the infinite, and mother of a group of celestial deities, the Adityas)

-

20

Alastor (An avenging deity or spirit, masculine personification of Nemesis)

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > Alastor (An avenging deity or spirit, masculine personification of Nemesis)

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

См. также в других словарях:

-

Personification — is an ontological metaphor in which a thing or abstraction is represented as a person. [ [http://www.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsPersonification.htm What is personification ] from SIL International] The term… … Wikipedia

-

personification — [pər sän΄ə fi kā′shən] n. 1. a personifying or being personified 2. a person or thing thought of as representing some quality, thing, or idea; embodiment; perfect example [he is the personification of honesty] 3. a figure of speech in which a… … English World dictionary

-

Personification — Per*son i*fi*ca tion, n. [Cf. F. personnification.] 1. The act of personifying; impersonation; embodiment. C. Knight. [1913 Webster] 2. (Rhet.) A figure of speech in which an inanimate object or abstract idea is represented as animated, or… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

Personification — Personification, jede Redefigur, durch die das Leblose belebt, d. h. redend oder handelnd eingeführt wird, z. B. die Blätter lispeln mir Deinen Namen zu. B–l … Damen Conversations Lexikon

-

Personification — Personification, rhetorische u. poetische Figur, worin ein lebloser Gegenstand personificirt d.h. als lebend gedacht und angeredet wird … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

-

personification — index embodiment Burton s Legal Thesaurus. William C. Burton. 2006 … Law dictionary

-

personification — 1755, noun of action from PERSONIFY (Cf. personify). Sense of embodiment of a quality in a person is attested from 1807 … Etymology dictionary

-

personification — The term personification comes from the Latin words persona (mask, person) and facere (to make). It is used to denote a * compound hallucination depicting a human being. Karl Jaspers (1883 1969) credits the German chemist Ludwig Staudenmaier… … Dictionary of Hallucinations

-

personification — per|son|i|fi|ca|tion [pəˌsɔnıfıˈkeıʃən US pərˌsa: ] n 1.) the personification of sth someone who is a perfect example of a quality because they have a lot of it ▪ He became the personification of the financial excess of the 1980s. 2.) [U and C]… … Dictionary of contemporary English

-

personification — [[t]pə(r)sɒ̱nɪfɪke͟ɪʃ(ə)n[/t]] personifications 1) N SING: usu the N of n If you say that someone is the personification of a particular thing or quality, you mean that they are a perfect example of that thing or that they have a lot of that… … English dictionary

-

personification — personificator, n. /peuhr son euh fi kay sheuhn/, n. 1. the attribution of a personal nature or character to inanimate objects or abstract notions, esp. as a rhetorical figure. 2. the representation of a thing or abstraction in the form of a… … Universalium

English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

person(ify) + -ification.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /pɚˌsɑ.nə.fəˈkeɪ.ʃən/

- Rhymes: -eɪʃən

Noun[edit]

personification (countable and uncountable, plural personifications)

- A person, thing or name typifying a certain quality or idea; an embodiment or exemplification.

-

Adolf Hitler was the personification of anti-Semitism.

-

1837, L[etitia] E[lizabeth] L[andon], Ethel Churchill: Or, The Two Brides. […], volume II, London: Henry Colburn, […], →OCLC, page 12:

-

He might have sat for a personification of fear: if he moved, he seemed rather afraid of his own shadow following him too closely; if he laughed, he soon checked himself, quite alarmed at the sound.

-

-

- A literary device in which an inanimate object or an idea is given human qualities.

-

The writer used personification to convey her ideas.

-

- An artistic representation of an abstract quality as a human

-

The Grim Reaper is a personification of death.

-

Coordinate terms[edit]

- anthropomorphism

- humanization

- prosopopoeia

Translations[edit]

person, thing or name typifying a certain quality or idea

artistic representation of an abstract quality as a human

See also[edit]

- pathetic fallacy

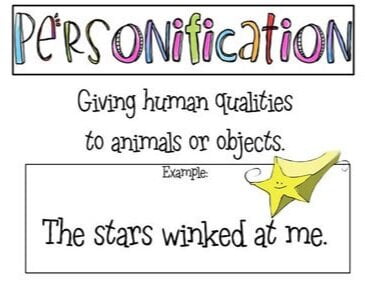

Definition of Personification

Personification is a figure of speech in which an idea or thing is given human attributes and/or feelings or is spoken of as if it were human. Personification is a common form of metaphor in that human characteristics are attributed to nonhuman things. This allows writers to create life and motion within inanimate objects, animals, and even abstract ideas by assigning them recognizable human behaviors and emotions.

Personification is a literary device found often in children’s literature. This is an effective use of figurative language because personification relies on imagination for understanding. Of course, readers know at a logical level that nonhuman things cannot feel, behave, or think like humans. However, personifying nonhuman things can be an interesting, creative, and effective way for a writer to illustrate a concept or make a point.

For example, in his picture book, “The Day the Crayons Quit,” Drew Daywalt uses personification to allow the crayons to express their frustration at how they are (or are not) being used. This literary device is effective in creating an imaginary world for children in which crayons can communicate like humans.

Common Examples of Personification

Here are some examples of personification that may be found in everyday expression:

- My alarm yelled at me this morning.

- I like onions, but they don’t like me.

- The sign on the door insulted my intelligence.

- My phone is not cooperating with me today.

- That bus is driving too fast.

- My computer works very hard.

- However, the mail is running unusually slow this week.

- I wanted to get money, but the ATM died.

- This article says that spinach is good for you.

- Unfortunately, when she stepped on the Lego, her foot cried.

- The sunflowers hung their heads.

- That door jumped in my way.

- The school bell called us from outside.

- In addition, the storm trampled the town.

- I can’t get my calendar to work for me.

- This advertisement speaks to me.

- Fear gripped the patient waiting for a diagnosis.

- The cupboard groans when you open it.

- Can you see that star winking at you?

- Books reach out to kids.

Examples of Personification in Speech or Writing

Here are some examples of personification that may be found in everyday writing or conversation:

- My heart danced when he walked in the room.

- The hair on my arms stood after the performance.

- Why is your plant pouting in the corner?

- The wind is whispering outside.

- Additionally, that picture says a lot.

- Her eyes are not smiling at us.

- Also, my brain is not working fast enough today.

- Those windows are watching us.

- Our coffee maker wishes us good morning.

- The sun kissed my cheeks when I went outside.

Famous Personification Examples

Think you haven’t heard of any famous personification examples? Here are some well-known and recognizable titles and quotes featuring this figure of speech:

Titles

- “The Brave Little Toaster” (novel by Thomas M. Disch and adapted animated film series)

- “This Tornado Loves You” (song by Neko Case)

- “Happy Feet” (animated musical film)

- “Time Waits for No One” (song by The Rolling Stones)

- “The Little Engine that Could” (children’s book by Watty Piper)

Quotes

- “The sea was angry that day, my friends – like an old man trying to send back soup in a deli.” (Seinfeld television series)

- “Life moves pretty fast.” (movie “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off”)

- “The dish ran away with the spoon.” (“Hey, diddle, diddle” by Mother Goose)

- “The Heart wants what it wants – or else it does not care” (Emily Dickinson)

- “Once there was a tree, and she loved a little boy.” (“The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein)

Difference Between Personification and Anthropomorphism

Personification is often confused with the literary term anthropomorphism due to fundamental similarities. However, there is a difference between these two literary devices. Anthropomorphism is when human characteristics or qualities are applied to animals or deities, not inanimate objects or abstract ideas. As a literary device, anthropomorphism allows an animal or deity to behave as a human. This is reflected in Greek dramas in which gods would appear and involve themselves in human actions and relationships.

In addition to gods, writers use anthropomorphism to create animals that display human traits or likenesses such as wearing clothes or speaking. There are several examples of this literary device in popular culture and literature. For example, Mickey Mouse is a character that illustrates anthropomorphism in that he wears clothes and talks like a human, though he is technically an animal. Other such examples are Winnie the Pooh, Paddington Bear, and Thomas the Tank Engine.

Therefore, while anthropomorphism is limited to animals and deities, personification can be more widely applied as a literary device by including inanimate objects and abstract ideas. Personification allows writers to attribute human characteristics to nonhuman things without turning those things into human-like characters, as is done with anthropomorphism.

Writing Personification

Overall, as a literary device, personification functions as a means of creating imagery and connections between the animate and inanimate for readers. Therefore, personification allows writers to convey meaning in a creative and poetic way. These figures of speech enhance a reader’s understanding of concepts and comparisons, interpretations of symbols and themes, and enjoyment of language.

Here are instances in which it’s effective to use personification in writing:

Demonstrate Creativity

Personification demonstrates a high level of creativity. To be valuable as a figure of speech, the human attributes assigned to a nonhuman thing through personification must make sense in some way. In other words, human characteristics can’t just be assigned to any inanimate object as a literary device. There must be some connection between them that resonates with the reader, demanding creativity on the part of the writer to find that connection and develop successful personification.

Exercise Poetic Skill

Many poets rely on personification to create vivid imagery and memorable symbolism. For example, in Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven,” the poet skillfully personifies the raven through allowing it to speak one word, “nevermore,” in response to the narrator’s questions. This is a powerful use of personification, as the narrator ends up projecting more complex and intricate human characteristics onto the bird as the poem continues though the raven only speaks the same word.

Create Humor

Personification can be an excellent tool in creating humor for a reader. This is especially true among young readers who tend to appreciate the comedic contrast between a nonhuman thing being portrayed as possessing human characteristics. Personification allows for creating humor related to incongruity and even absurdity.

Enhance Imagination

Overall, personification is a literary device that allows readers to enhance their imagination by “believing” that something inanimate or nonhuman can behave, think, or feel as a human. In fact, people tend to personify things in their daily lives by assigning human behavior or feelings to pets and even objects. For example, a child may assign emotions to a favorite stuffed animal to match their own feelings. In addition, a cat owner may pretend their pet is speaking to them and answer back. This allows writers and readers to see a reflection of humanity through imagination. Readers may also develop a deeper understanding of human behavior and emotion.

Examples of Personification in Literature

Example #1: The House on Mango Street (Sandra Cisneros)

But the house on Mango Street is not the way they told it at all. It’s small and red with tight steps in front and windows so small you’d think they were holding their breath.

In the first chapter of Cisneros’s book, the narrator Esperanza is describing the house into which she and her family are moving. Her parents have promised her that they would find a spacious and welcoming home for their family, similar to what Esperanza has seen on television. However, their economic insecurity has prevented them from getting a home that represents the American dream.

Cisneros uses personification to emphasize the restrictive circumstances of Esperanza’s family. To Esperanza, the windows of the house appear to be “holding their breath” due to their small size, creating an image of suffocation. This personification not only enhances the description of the house on Mango Street for the reader, but it also reflects Esperanza’s feelings about the house, her family, and her life. Like the windows, Esperanza is holding her breath as well, with the hope of a better future and the fear of her dreams not becoming reality.

Example #2: Ex-Basketball Player (John Updike)

Off work, he hangs around Mae’s Luncheonette.

Grease-gray and kind of coiled, he plays pinball,

Smokes those thin cigars, nurses lemon phosphates.

Flick seldom says a word to Mae, just nods

Beyond her face toward bright applauding tiers

Of Necco Wafers, Nibs, and Juju Beads.

In his poem about a former basketball player named Flick, Updike recreates an arena crowd watching Flick play pinball by personifying the candy boxes in the luncheonette. The snack containers “applaud” Flick as he spends his free time playing a game that is isolating and requires no athletic skill. However, the personification in Updike’s poem is a reflection of how Flick’s life has changed since he played and set records for his basketball team in high school.

Flick’s fans have been replaced by packages of sugary snacks with little substance rather than real people appreciating his skills and cheering him on. Like the value of his audience, Flick’s own value as a person has diminished into obscurity and the mundane now that he is an ex-basketball player.

Example #3: How Cruel Is the Story of Eve (Stevie Smith)

It is only a legend,

You say? But what

Is the meaning of the legend

If not

To give blame to women most

And most punishment?

This is the meaning of a legend that colours

All human thought; it is not found among animals.How cruel is the story of Eve,

What responsibility it has

In history

For misery.

In her poem, Smith personifies the story of Eve as it is relayed in the first book of the Bible, Genesis. Smith attributes several human characteristics to this story, such as cruelty and responsibility. Therefore, this enhances the deeper meaning of the poem which is that Eve is not to blame for her actions, essentially leading to the “fall” of man and expulsion from Paradise In addition, she is not to blame for the subjugation and inequality that women have faced throughout history and tracing back to Eve.

Eve’s “story” or “legend” in the poem is accused by the poet of coloring “all human thought.” In other words, Smith is holding the story responsible for the legacy of punishment towards women throughout history by its portrayal of Eve, the first woman, as a temptress and sinner. The use of this literary device is effective in separating Eve’s character as a woman from the manner in which her story is told.

Personification Definition: Personification is a literary device that gives humanlike characteristics to non-human entities. Personification is a type of figurative language.

What Does Personification Mean?

What is the definition of personification? Personification occurs when a writer makes a non-human thing have human behavior. Hence, the writer personifies that object.

Figurative language is any word or phrase that is not to be taken literally but is used in writing for effect.

Personification Example

- The wind danced in the trees.

Personification Example

- The ocean sang a mesmerizing song.

This example uses personification to provide sensory language for the sound the ocean makes. The ocean cannot literally sing, as a human can. Therefore, the phrase is figurative and the ocean is personified.

Personification Example

- The windows trembled with fear.

This example uses personification to provide mood and imagery for the movement and sound the windows make. The windows cannot literally tremble, as a human can. Therefore, the phrase is figurative and the windows are personified.

Personification Examples in Everyday Language

- New York is the city that never sleeps.

This example uses personification to imply that New York is constantly a bustling city. The city cannot literally sleep, nor can the city be awake, like a human can. However, this common phrase is accepted to mean that New York is a lively, energetic city, day or night.

Personification Examples in Music

- “Time grabs you by the wrist, directs you where to go” from “Good Riddance” by Green Day

This example uses personification to imply that time can grab you, pull you, and direct you. Time is not a human but is personified to act like a human in these lyrics.

Personification Examples in News Stories

You see examples of personification in financial settings and news stories quite often. “Stocks hurt today,” “The market fought to secure its gain,” etc. Here is a common example from Market Watch using oil prices,

- Crude oil prices struggled on Monday, at times rising on hopes that a fall in U.S. oil rigs would ease excess supply while stronger consumer spending in that country would spark demand for oil. –Market Watch

The Importance and Function of Personification

Personification makes literature and writing more engaging and more interesting. In many cases, it brings life to abstract object or ideas. For example, in the above example, time is given human qualities and, therefore, brings this abstract concept to life.

Personification is used to enhance writing and to emphasize a point. It is much more powerful to say,

- The wind danced in the trees

than it is to say,

- The wind moved through the trees and made the leaves move around softly.

Like all literary devices, writers use personification with purpose and meaning.

Examples of Personification in Literature

Perhaps one of the most well-knows uses of personification in literature includes Emily Dickinson’s poem, “Because I could not stop for Death”. Below is an excerpt.

Personification Examples in Poetry

Because I could not stop for Death—

He kindly stopped for me—

The Carriage held but just Ourselves—

And Immortality.

We slowly drove—He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility.

This poem refers to “Death” as if he were a person, able to function as a human. Dickinson utilized personification to communicate the speaker’s feelings and emotions surrounding the idea of death.

What Does Personified Mean?

Personified Definition: Personified is the action of thinking or representing inanimate objects or abstraction as having personality, thought, or qualities of living, human beings.

Something that is personified is an example of personification. Personified is nothing more than the verb form of personification.

Summary

What is personification? Personification is an effective literary device used to enhance writing.

When a writer personifies an object, he gives it figurative, humanlike qualities in order to create a particular effect.

Contents

- 1 What Does Personification Mean?

- 2 Modern Examples of Personification

- 3 The Importance and Function of Personification

- 4 Examples of Personification in Literature

- 5 What Does Personified Mean?

- 6 Summary

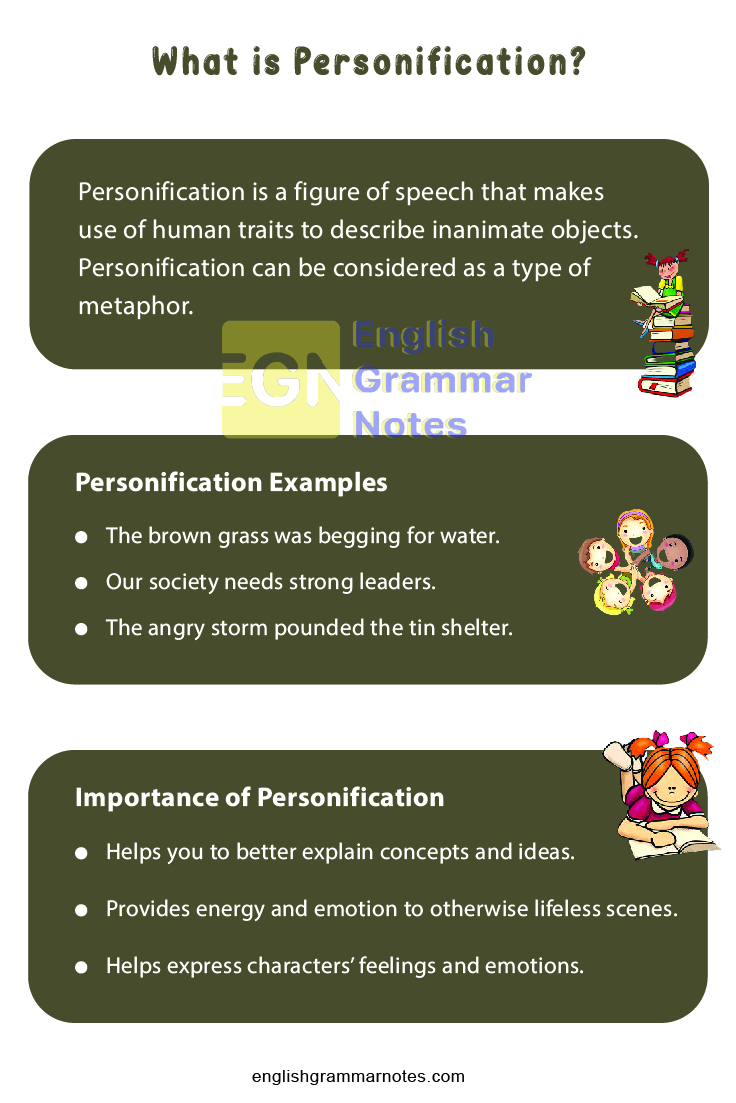

The use of figurative language will help you give a different meaning to a word outside the literal one. Personification is a commonly used figurative language that can make your writing more creative. Personification can be used in creative writing to describe scenes and indirectly express feelings. In this article, we have put together all the essential information about personification including its definition, common examples, its significance, etc.

- What is Personification?

- Personification Examples

- Importance of Personification

- Anthropomorphism Vs Personification

- What is personification?

- Give examples of Personification?

- Distinguish between Personification and Anthropomorphism?

- What is the significance of using personification?

What is Personification?

Personification is a figure of speech that makes use of human traits to describe inanimate objects. Personification can be considered as a type of metaphor. This figure of speech is used to create more interesting and engaging scenes or characters.

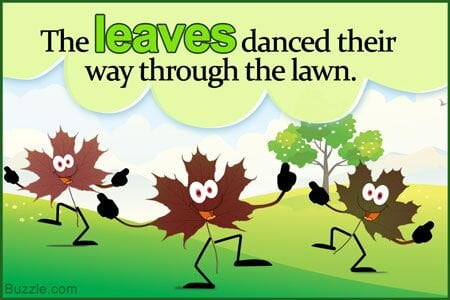

Personification Examples

Personification is a commonly used stylistic device. Given below is a list of examples of personification.

- When fall changed to winter, the trees could be seen as wearing white.

- The brown grass was begging for water.

- Our society needs strong leaders.

- The sunflowers nodded in the wind.

- My piano is of pretty good manners but he can make them sound rude.

- The traffic noises fought long.

- The angry storm pounded the tin shelter.

- A school of rainbow trout swam across the river.

- The silence crept into the classroom.

- This city never sleeps.

- The sun stretched its golden arms and spread light

- I wanted some money, but the ATM died.

- This essay says that turnip is good for you.

- Unfortunately, when she stepped out, her foot cried.

- The sunflowers hung their heads.

- That door jumped in my way.

- The school bell called us from outside.

- In addition, the storm trampled the town.

- I am not able to get my calendar to work for me.

- This advertisement speaks to me

- My alarm yelled at me this morning.

- I love onions, but they don’t love me.

- The sign on the door insulted me.

- My phone is not happy with me today.

- That bus is driving too fast.

- My computer works very hard.

- However, the mail is running too slow today.

- Fear seized the patient at the time of surgery

- The cupboard groans when you open it.

- Can you see that star winking at you?

- Books reach out to kids.

Explore our other Literary Devices to improve your knowledge of Grammar Concepts and get a grip in the language.

Importance of Personification

The use of personification has several benefits. These include:

- Helps you to better explain concepts and ideas.

- Provides energy and emotion to otherwise lifeless scenes.

- Helps express characters’ feelings and emotions.

Anthropomorphism Vs Personification

Just like personification, anthropomorphism gives human characteristics to objects or animals. It can be considered as a kind of personification. Animals or objects are described as real people with abilities. Hence anthropomorphism is stronger than simple personification.

Read More:

- Metonymy

- Paradox

- Understatement

FAQs on Personification

1. What is personification?

Personification can be considered as a type of metaphor that makes use of human traits to describe inanimate objects.

2. Give examples of Personification?

Common examples of personification include: In addition, the storm trampled the town, I can’t get my calendar to work for me, This advertisement speaks to me, etc.

3. Distinguish between Personification and Anthropomorphism?

Like personification, anthropomorphism gives human characteristics to objects or animals. Animals or objects are described as real people with abilities. Hence anthropomorphism is stronger than simple personification.

4. What is the significance of using personification?

The use of personification has the following advantages: Helps you to better explain concepts and ideas, provides energy and emotion to otherwise lifeless scenes, and helps express characters’ feelings and emotions.

Conclusion

As a stylistic device, personification is used to assign human attributes to inanimate objects. The main function of this figure of speech is to breathe life into inanimate objects or characters. The use of personification will make your writing vivid and have the reader’s attention to what you write. So make sure you include personification and grab the reader’s attention!

Personification is a variety of

metaphor, attributing human properties to lifeless objects, mostly

to abstract notions such as thoughts, intentions, emotions, seasons

of the year, or animals.

Personification

is often represented grammatically by the choice of masculine or

feminine pronouns for the names of inanimate objects, or by

capitalization of these words.

|

Personification The |

Personifications are most often

used in poetry.

|

Personification

Twinkle,

How (Jane

No To (Byron)

How Stolen (Milton) |

4. Allusion

Allusion is a special variety of

metaphor, an indirect reference to some historical or literary fact

commonly known. The frequently used sources for allusions are the

Bible and mythology. The effect of allusion can be achieved only if

facts alluded to are known to the reader.

|

Allusion

Пить

The

|

5. Metonymy

Metonymy

is based on contiguity of notions, not on resemblance. It is

applying the name of an object to another object in some way

connected with the first one. There is an objectively existing

relationship between the object named and the object implied.

|

Metonymy

The The

Вся Силы |

Metonymic relations are varied

in character:

1) the result may stand for

the cause

(The

fish desperately takes the death);

2) the cause may stand for

the result

(The

writer lives by his pen only);

3) a symbol may stand for

an object signified

(“brain

drain”);

4) a characteristic feature

may stand for its bearer

(She

turned round and took a long look at her grandmother’s blackness);

5) the instrument may

stands for the action

(Countrymen,

give me your ears!);

6) the container may stand

for the thing contained or vise versa

(The

kettle boils);

7) an abstract noun may

stand for a concrete noun

(Labour

demonstrated in the streets);

the thing made of it (There

was a shower of steel on the trenches);

9) the name of the creator

may stand for his creation

(We

bougnt two Rembrands).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

What is Personification?

Personification: A Definition

Before students can recognize the use of personification in the literature they read and use the device in their writing, they first need to have a firm grasp of what exactly personification is.

Fundamentally, personification is a specific type of metaphor. Generally, personification is defined as a literary device that assigns human qualities and attributes to objects or other non-human things.

Simple examples that illustrate this definition can be found easily in our everyday speech. Many common examples of personification are so clichéd as to be almost invisible to the naked ear. We commonly hear these in such phrases as “the angry wind” or when we talk of “the brooding sky.”

However, this basic definition doesn’t tell the whole story regarding this literary device.

Not only does personification refer to the ascribing of human qualities to nonhuman things, such as in the use of emotions in the examples above, but it can also refer to the doing of actions we normally ascribe exclusively to humans.

For example, in the phrase“the light danced across the sky”, even though we know the action of dancing is one that can technically only be performed by humans, we find no incongruity in the above phrase. A certain image is conjured up in our minds and we understand it imaginatively.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE

❤️The use of FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE is like “SPECIAL EFFECTS FOR AUTHORS.” It is a powerful tool to create VIVID IMAGERY through words. This HUGE 110 PAGE UNIT guides you through a complete understanding of FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE as both a READER and WRITER covering.

- ❤️ ALLITERATION

- ❤️ IDIOMS

- ❤️ METAPHORS

- ❤️ ONOMATOPOEIA

- ❤️ PERSONIFICATION

- ❤️ SIMILES

A WORD ON ANTHROPOMORPHISM VS PERSONIFICATION

In any exploration of personification, it’s worth taking a moment to point out the difference between anthropomorphism and personification.

While they have much in common, take the time to ensure students are aware there are some key differences as the two are often confused.

If personification is the attribution of human qualities and attributes to nonhuman things, then we can think of anthropomorphism as going a step further to completely turn nonhumans into humans – in all but outward appearance, usually.

Here, think of the characters in Aesop’s fables or in George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

But, whether we are talking about personification or anthropomorphism, why bother with all this artifice? Why not just say what we mean in as straightforward a manner as possible?

WHY USE PERSONIFICATION IN LITERACY?

When we look over the bloody human history of war and genocides we can see a common precursor to slaughter is the dehumanizing of the ‘other’.

Often, this is done through labelling the perceived enemy as ‘rats’ or ‘cockroaches’ or other vermin. Stripping others of their humanity in such a fashion makes it easier to justify the slaughter that ensues.

Personification works in almost exactly the opposite way – you’ll be relieved to hear!

By humanising non-human things, we bring them closer to the reader’s experience, making it easier for the reader to relate to them in an imaginative way.

Personification often works to make things more memorable and relatable. It frequently represents a climbing down the ladder of abstraction conceptually.

In a nutshell, personification is a powerful tool that can create vivid images and deep subconscious connections in the mind of the reader, when it’s used at its most skilfully.

WHEN TO USE PERSONIFICATION IN WRITING.

Given personification is a figurative use of language, it is no surprise we see it so widely used in poetry. Indeed, this is where most students first encounter it.

However, students need to realise that personification is used in everything from everyday speech to popular songs and even in the visual arts where we sometimes see nonhuman objects depicted with human qualities. For example, a human face with puffed cheeks blowing to illustrate the wind.

As personification often focuses on human emotions, the literary device often doesn’t sit well in more formal contexts such as essays and technical writing.

There are exceptions to this general rule, of course.

Sometimes in formal writing or speech, personification can be used to climb down the ladder of abstraction to help illuminate a complex idea.

For example, when explaining the water cycle we may use a phrase like ‘the water wants to flow downhill’ to describe the water’s behaviour during a certain stage of the cycle.

THE PERSONIFICATION OF IDEAS

At the beginning of this article we defined personification as assigning ‘human qualities and attributes to objects or other non-human things.’ These things need not all be concrete nouns.

Personification often illuminates the abstract is through the personification of ideas and concepts.

We can see this clearly in the manner in which ancient civilisations personified abstract concepts in the form of gods.

For example, the Greeks had Eros and the Romans Venus as their personifications of love.

Not only does this personification of abstract ideas help us to understand the concepts, it affords an opportunity for human interaction with the concepts, as we can see throughout various mythological cycles and works of literature.

PERSONIFICATION IN POETRY: A WRITING ACTIVITY

Personification connects us intimately with the thing that is personified.

For this reason, poetry is the perfect genre to explore the use of personification in literature and for students to begin to experiment with the device in their own work.

Choose a poem that employs personification to discuss with the class. John Donne’s Death Be Not Proud, Keats’ To Autumn, or Robert Frost’s Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening are excellent and well-known examples.

Read the poem together and have students identify the uses of personification.

Encourage students to share their thoughts on why the poet employs personification and how its use contributes to the poem’s overall effect.

Once students have a good understanding of what personification is and why and how it’s used, the time is right to challenge students to come up with some original examples of personification in their own writing.

One fun way to do this is to provide students with a list of verbs normally associated with things people do (sing, dance, play, speak, etc).

Then, provide them with a list of nonhuman things and objects (book, river, fox, thunder, etc) and challenge the students to create examples of personification by matching words from each list.

For example, if we take the first word from each of the lists in brackets we’ll have ‘sing’ and ‘book’. From these we could create the example: The book sang to us the deeds of the hero.

With a little practice, your students will soon become confident in recognizing the use of personification in the work of others and understanding its impact. With a little more practice, your students will soon have their own words dancing on the page too!

USEFUL VIDEOS FOR TEACHING STUDENTS ABOUT PERSONIFICATION

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO PERSONIFICATION

Figurative Language for Students and Teachers

A Complete guide to figurative language for students and teachers. WHAT IS FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE? A DEFINITION We most often associate figurative language with poetry, but we find figurative language widely used in many other contexts too. We find it in use in everything from fiction and folk music to drama and our daily speech. The…

13 Literary Devices to Supercharge your Writing Skills

WHAT ARE LITERARY DEVICES? If words are the raw materials of a writer’s trade, literary devices are the tools the writer uses to craft those words into a meaningful and/or beautiful shape. Hundreds of these devices are at a writer’s disposal, covering every aspect of the writing process from word and sentence level (figurative language…

7 ways to write great Characters and Settings | Story Elements

STORY ELEMENTS: How to Write Great Characters and Settings You can’t have a good story without the characters to do things and places for them to do those things in. In this article, we’re talking about great characters and settings and how to write them. Characters and setting are two key ingredients that form the…

Teaching The 5 Story Elements: A Complete Guide for Teachers & Students

What Are Story Elements? Developing a solid understanding of the elements of a story is essential for our students to follow and fully comprehend the stories they read. However, before students can understand how these elements contribute to a story’s overall meaning and effect, they must first be able to identify the component parts confidently….

Elements of Literature

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY THE PHRASE ‘ELEMENTS OF LITERATURE? The phrase ‘elements of literature’ refers to the constituent parts of a work of literature in whatever form it takes: poetry, prose, or drama. Why are they important? Students must understand these common elements if they are to competently read or write a piece…

The content for this page has been written by Shane Mac Donnchaidh. A former principal of an international school and English university lecturer with 15 years of teaching and administration experience. Shane’s latest Book, The Complete Guide to Nonfiction Writing, can be found here. Editing and support for this article have been provided by the literacyideas team.

Personification means giving human qualities to something that is not human. You can use personification when describing nature, everyday objects, or even abstract concepts such as love or death.

Personification meaning

Just look at the word itself — personification. Think of it as meaning “turning something into a person”. Like metaphor and simile, personification is a type of figurative language, or a figure of speech, meaning that it expresses an idea or feeling in a way that is non-literal.

Personification examples — words and sentences

The best way to understand personification is by looking at examples; In this section, we’ll dissect some lines by famous writers, but first, here are a few phrases that you might hear in everyday conversation.

Examples of everyday personification

A raging storm.

In this example, the speaker describes a storm as if it has an emotion — we know that a storm doesn’t literally feel rage, but the phrase helps us to picture it as an aggressive force.

The groaning floorboards.

Not only does the word «groaning» help us to imagine the creaking sound of the wood, but it suggests a particular attitude — we get the idea that the floorboards are jaded and miserable — well, wouldn’t you be if people kept walking all over you?

This room is crying out for new wallpaper.

We know that if a person is «crying out» for something, they are in desperate need — here, the speaker uses this term to make their point about how badly they feel the room needs new wallpaper.

Examples of personification in poetry

«The modest rose puts forth a thorn»

(William Blake, The Lily, 1794)

By describing the rose as «modest», Blake gives it a personality and explains why it might grow a thorn to keep others at bay.

«The sink chokes on soggy bread»

(Lemn Sissay, Remembering the Good Times We Never Had, 2008)

Here the personification comes from the idea that the sink is choking — we can imagine its clogged plughole as a throat crammed with soggy bread and almost feel sorry for it, despite the fact that it’s an inanimate object.

«The frisbee winning the race against its own shadow»

(Roger McGough, «Everyday Eclipses,» 2002)

By suggesting that the frisbee is racing its own shadow, McGough adds some playful personification to an everyday trick of the light.

Examples of personification in song lyrics

«Hello darkness, my old friend»

(Simon & Garfunkel, “The Sound of Silence”, 1964)

In this famous line, the speaker is directly addressing the darkness as if it was a person. Referring to darkness as his friend lets us know that he is familiar with it, giving us an insight into his state of mind.

«I met this girl when I was ten years old,

And what I loved most, she had so much soul ”

(Common, «I Used to Love HER», 1994)

This one isn’t obvious at first, but the rapper Common is personifying the culture of hip hop as a woman. Throughout the song he talks about how they grew up together and how their relationship changed over the years as she became more materialistic. This song could also be classed as an extended metaphor .

“The sun comes swaggering across the harbor,

And kisses the lady waiting in the narrows ”

(Grace Jones, The Apple Stretching, 1982)

This song describes a morning in New York, and in this line, the swaggering, bold personality of the sun seems to reflect the attitude of the city.

Examples of personification in fiction

«… the brass yaw of the elevator stood mockingly open, inviting her to step in and take the ride of her life.»

(Stephen King, The Shining, 1977)

King uses personification to create a creepy, unsettling effect as the elevator appears to mock the protagonist Wendy, daring her to step inside.

«… certain airs, detached from the body of the wind (the house was ramshackle after all) crept round corners and ventured indoors.»

(Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse, 1927)

This refers to the drafts blowing through an empty house; saying that they “crept round corners” makes us imagine them as intruders. Woolf then builds on this imagery, going on to describe them «toying with the flap of hanging wall-paper, asking, would it hang much longer, when would it fall?»

«Would you be in any way offended if I said that you seem to me to be in every way the visible personification of absolute perfection?»

(Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest, 1895)

In this line from Wilde’s play, the speaker is telling his love interest that if absolute perfection (an abstract concept) was a person, it would be her. To him, she symbolises the idea of perfection. In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at this type of personification: using characters (fictional or real) as symbols.

Characters as symbols

Throughout folklore and popular culture, you’ll find many characters that represent abstract concepts. Sometimes, even real people become symbolic of certain ideas.

Which characters personify abstract concepts?

An example of a character that personifies an abstract concept is Father Time — often portrayed as a bearded old man, he represents the concept of time. Similarly, Cupid is the personification of love, and Mother Nature is the personification of (you guessed it) nature.

Death is commonly represented as a hooded figure, sometimes known as the Grim Reaper, but there are many variations of this across different cultures. Another example you may be familiar with is Uncle Sam, the symbol of American patriotism who famously appeared on the “I want YOU” posters.

Can real people personify abstract concepts?

Sometimes, you might describe a real person as the personification of an abstract concept. For example, you might call somebody who has spent their whole life helping others as «the personification of kindness». Perhaps you’d refer to a cruel dictator from history as «the personification of evil». Or maybe you think of that person who never tidies up their own mess as “the personification of laziness”! Of course, in real life people have many different sides to them — this is just one way of using personification as a rhetorical device.

Effect of personification

Hopefully, the examples from poetry, song lyrics and fiction have shown you how personification can make a piece of writing much more vivid; it can really make the words “jump off the page” (which also happens to be an example of personification!). By giving human emotions to inanimate objects, you can enhance the feel or atmosphere of a piece. Another reason to use personification is to express an idea or opinion — using characters as symbols can be a powerful technique to achieve this effect. Think of personification as another tool in your box of figurative language that can help make your writing more expressive.

Personification vs anthropomorphism — what’s the difference?

It can be tricky to distinguish between personification and anthropomorphism, as they have a lot in common.

First, let us define anthropomorphism. Anthropomorphism is when anything that is not human (such as animals or objects) is made to act human. Examples include:

- Cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck wear human clothes, can talk and live human-like lives.

- Thomas the Tank Engine and his friends, are anthropomorphized trains.

- The animals in George Orwell’s Animal Farm can talk and some of them eventually walk on two legs.

So how does this differ from personification? Well, in their own fictional world, these characters are not figures of speech, they are literal; we are supposed to believe that they are really living and breathing, walking around and acting like humans. Also, they do not necessarily symbolize an idea or abstract concept in the way that personification can.

For further clarity, let’s compare the two so that we can see the similarities and differences:

| Personification | Anthropomorphism |

| Gives human traits to non-human things. | Gives human traits to non-human things. |

| Describes non-human things as having human traits. | Makes non-human things act like people. |

| Is figurative. | Is literal. |

| Creates imagery. | Is mostly used to create characters for the purpose of storytelling. |

| Can be used to represent an abstract concept (eg, Mother Nature represents nature, Uncle Sam represents American patriotism). | Does not usually represent or symbolize anything. |

Personification — Key takeaways

- Personification is what you get when you give human qualities to something that is not human (such as animals, objects or abstract concepts).

- Personification can make a piece of writing much more vivid; by giving human qualities to things such as the weather or everyday objects, you can paint a clearer picture in the reader’s mind.

- Some characters represent abstract concepts and so they are the personification of that thing. An example of this is the Grim Reaper, who is the personification of death.

- Personification and anthropomorphism are not the same. Personification is figurative or symbolic; anthropomorphism is literal.

Personification Definition

What is personification? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Personification is a type of figurative language in which non-human things are described as having human attributes, as in the sentence, «The rain poured down on the wedding guests, indifferent to their plans.» Describing the rain as «indifferent» is an example of personification, because rain can’t be «indifferent,» nor can it feel any other human emotion. However, saying that the rain feels indifferent poetically emphasizes the cruel timing of the rain. Personification can help writers to create more vivid descriptions, to make readers see the world in new ways, and to more powerfully capture the human experience of the world (since people really do often interpret the non-human entities of the world as having human traits).

Some additional key details about personification: