Why does «nice» automatically make us think «weak»?

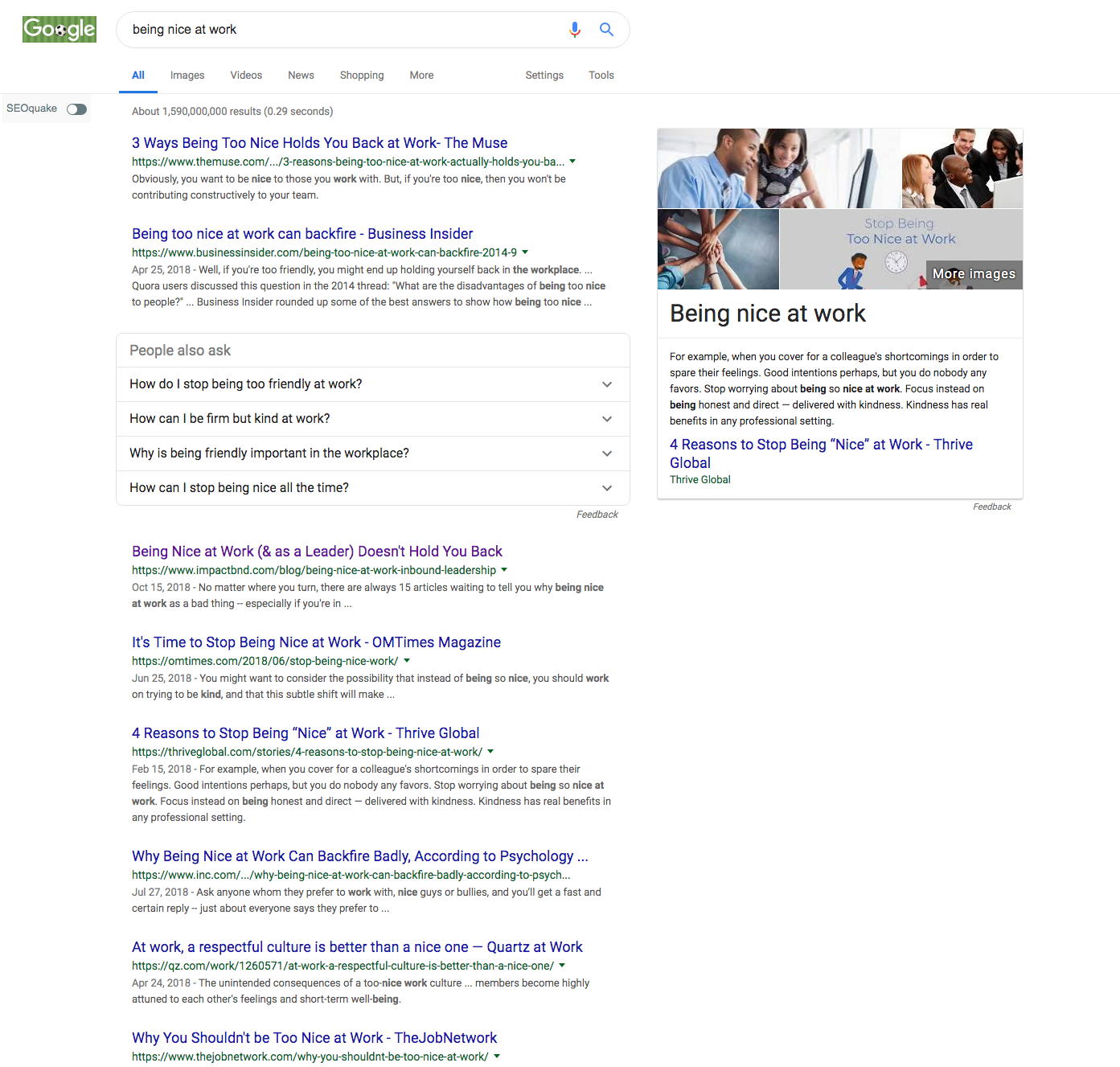

When I was first asked to think about this and to write about it, I didn’t think I had much to say, until IMPACT Director of Web and Interactive Content Liz Murphy showed me the the search results for “being nice at work.”

Every single result — other than the article written by IMPACT VP of Services Brie Rangel — reinforces this idea that being nice at work isn’t good.

That being nice it is a sign of weakness, or it is something that will hold you back.

As Liz showed me these results, I felt a lot of sensations rise within me. I started to feel anger — you know that deep turning in your stomach, the constricting of your upper body… I was overwhelmed for a moment with this frustration.

I’m pretty good at feeling these emotions arise, feeling the warning signs of potentially losing my cool and becoming reactive. So, I let it happen. And it went on for some time.

I simply couldn’t understand how people thought giving advice about not being nice was a good thing! With all of the issues people are facing today, why would anyone think that being nice was bad?

How does this help our society?

I then started to think about the state of the American workforce — where an overwhelming majority of people are not engaged at worked according to Gallup. Burnout has just become an official medical condition according to the World Health Organization. And workplace anxiety is becoming more prevalent.

Still, the leadership «experts» say being nice is a bad thing.

What is going on? From where I’m standing, we have a huge niceness gap.

People don’t see each other. We are so focused on ourselves, that we forget our actions and inactions, both verbal and nonverbal, affect everyone around us. Yet these leadership myths that shrug off niceness as a barrier to giving good feedback or as an overall weakness persist.

I don’t believe being a leader who is nice and being a leader who can give constructive feedback are mutually exclusive concepts. Nor do I believe being nice is a sign of weakness in a leader.

Let me explain why.

It Begins with Intentional, Specific Communication

This year we’ve made a huge investment in leadership development and in developing our team, with a huge focus on communication. Leadership and communication go hand-in-hand, in my opinion. So, as we looked at what IMPACT, as an organization, needed to focus on to achieve the goals we had set for 2019, these two areas came to light.

We knew our people needed great leaders who were there to empower them to do their best work and live their best life, and we needed to ensure everyone had a shared language around communication.

One that allowed us to be more intentional and concise.

One of the key aspects of this program is centered around feedback — both how to give it effectively and how to receive it. Feedback is tough, and it makes us uncomfortable, whether we’re giving it or receiving it.

When organizations and leaders don’t know how to give feedback it creates issues, which can range from the fact that they don’t give it, to giving it in a way that makes people feel small or less than. When people don’t know how to handle receiving feedback things like burnout, overwhelm, or reactionary outbursts can occur.

As leaders, we need to be good at both giving and receiving feedback.

The first thing we talk about with feedback is that it has to be specific and it has to be about what occurred, not about the person.

Kim Scott talks about this in her book Radical Candor. “Radical candor” is a principle which she defines as the ability to challenge directly and care personally. (For those who are interested, Brie wrote a great review digging into much more of the book.)

Here is an excerpt from Radical Candor that highlights a concept very important to this notion of giving effective feedback — being specific:

Being precise can feel awkward.

For example, I once had to say, “When we were in that meeting and you passed a note to Catherine that said ‘Check out Elliot picking his nose–I think he just nicked his brain,’ Elliot wound up seeing it. It pissed him off unnecessarily, made it harder for you to work together, and was the single biggest contributing factor to our being late on this project.”

It was tempting just to say, “Your note was childish and obnoxious.”

But that wouldn’t have been as clear or as helpful. The same principle goes for praise. Don’t say, “She is really smart.” Say, “She can do the NYT crossword puzzle faster than Bill Clinton,” or “She just solved a problem that no mathematician in history has ever been able to solve,” or “She just gave the clearest explanation I’ve ever heard of why users don’t like that feature.”

By showing rather than telling what was good or what was bad, you are helping a person to do more of what’s good and less of what’s bad, and to see the difference.

When we aren’t specific we leave things open to interpretation and we set the conditions for our people to start telling themselves elaborate stories.

This is where nice has gotten a bad rap.

I want you to be honest with yourself here, have you ever said something like:

“You’re too nice,” to an employee, when you really meant, “You weren’t firm enough with David on the lack of specifics in his pitch”?

You may have thought you were saying the latter when you said they were too nice, but you didn’t.

I am guilty of this.

It’s an easy trap to fall into at times.

For me, it usually manifests when I assume that everyone has a general understanding of what I’m talking about, that we have a shared level of depth in the area. When this happens, I oversimplify, I make assumptions.

The key here is being aware of this within yourself, so you don’t continue to do it.

“If Nice Is a Weakness, How Can It Be Strength?”

I’ve worked for a ton of people in my career — some more effective than others.

These leaders came in all shapes and sizes and styles. Some were quiet, some were loud. Some were incredibly focused on results, some were incredibly focused on people.

Of all the great leaders I’ve had, they all seem to have shared a singular quality that is virtually impossible to fake — they genuinely cared about their people and their mission.

You could see them struggle, internally, when they had to make a choice that put the mission ahead of their people. They had empathy, compassion, and were human… and we knew it.

I don’t know that the label nice is one I would have used with these leaders when I was serving under them. But in hindsight, I think it is fitting.

They were simply good people.

People I counted on for guidance, coaching, inspiration. They always treated me like a human, not simply a means to an end. When I needed something, they were there, no matter what.

(While this isn’t exactly the definition of nice from the dictionary, its good enough for me.)

These leaders were the opposite of weak. Their demeanor and caring nature made them stronger than any of their peers. These were the leaders that created more leaders. They were the ones who would live on forever, not because people feared them, but because people like me would continue to tell their stories and attempt to lead in the same way that they had.

When we think of nice, we shouldn’t hear weak; we should hear human, compassionate, caring.

When I think of what this looks like I am reminded of one of my mentors, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) J. Adam Barlow. Adam was my first boss in the 82nd Airborne Division and basically my battle buddy in Afghanistan.

I worked directly under Adam on the brigade staff for about a year. After that, I moved into company command and he became my battalion’s operations officer, meaning we got to work together even longer!

When I think back on how I’ve come to view leadership, Adam is an example that stands out. He got the best out of me and everyone that was around him. He had a superpower to make people their best.

He wasn’t the loudest. He wasn’t in your face. He was simply himself.

He was a paratrooper, he was a native of Appalachia, he was a Christian, he was a husband, father, friend… he was genuine when he gave feedback, and I knew he truly cared about me as a human and as a paratrooper.

He was an inbound leader, years before I started to define what I believed that meant.

I’m not going to go into great depths with not nice, other than to share that in my personal experience, leaders who I would characterize as not nice, were generally less effective.

They would suck all of the motivation right out of me, getting nothing more than compliance.

The leaders who were nice — compassionate, human, caring — those leaders got full out commitment from me. I would have followed them anywhere, at any time, no matter what.

What Would Be Possible If More People (& Leaders) Were Nice?

I love to think about things in the “what’s possible?” realm. If we don’t do this, we tend to stick with the status quo… «This is how things have always been done. We don’t innovate, we don’t dare, we don’t create.»

So, let’s do it here. If more people were nicer at work or at home or, quite frankly, wherever they are, don’t you think the world may be a bit better?

Maybe more people would be engaged at work.

Maybe more people would make more meaningful connections with other humans.

Maybe we’d have more leaders who led with compassion.

Imagine what your life would be like if those things were true. First and foremost, I’d assume that our relationships with others would be stronger and more meaningful.

Now, imagine what’s possible inside an organization, where its people embrace this kind of mentality. We’d be more effective and more efficient, we’d deal with fewer people issues, and we’d get to focus more on our actual work.

When we think about what’s possible, it makes me laugh to think that so many others think that being nice is going to set us back. It is going to make you less effective at the office, in life…

So, Should You Be Nice at Work?

Yes. Of course, you should.

Here’s the deal. If you want to be happy, if you want others to be happy, and you want to leave an imprint on people’s lives, then yes, be nice — always.

If you want to simply get ahead and you don’t care about how your actions affect others, I don’t know what to tell you. Hopefully, I’ve been able to show you that there is, at least, another way.

Nice doesn’t mean weak.

Nice doesn’t mean soft.

Nice shouldn’t be seen as a negative.

As leaders, we need to dig deeper. We need to do the real work and not worry about if we’re “too nice.” That’s complete hogwash.

Nice isn’t a four letter word — it’s something we all could be more of the time.

For me, I want to lead with compassion, with care, with my whole heart. This is not saying that I’m never stern or authoritative; it simply means that my intentions come from a place of love and compassion.

I don’t know that people would label me as nice.

But if they did, I’d wear it as a badge of honor.

Continue Learning about Movies & Television

Is you donkey a bad word?

its not a bad word, but its a prohibeted word

Is bloody a bad word in Canada?

It’s not a bad word, but some people say it’s a bad word.

What bad word in fast and furious 3?

there is not realy a bad word in.

What is a nice slogan for sulfur?

Sulfur, the good, the bad and the yellow.

What is the comparative of bad?

The comparative of the adjective «bad» is the word worse.The superlative of the adjective «bad» is the word worst.

If you want to give someone at work a back-handed compliment, try telling them they’re nice.

As a generally sunny person whose niceness gets commented on by colleagues quite a bit, I wouldn’t say the “nice” label is objectively insulting. But it concerns me. Mainly, I worry that in the professional world, getting branded as nice makes me less likely to receive recognition for being good at my job.

Unfortunately, this is a perfectly rational fear. Studies show that women who act friendly and warm in the workplace are often viewed as less competent, regardless of their actual abilities. “For women who conform in certain ways to the expectation that women are friendly and warm, the consequence for them is that their skills can be overlooked,” notes Marianne Cooper, a sociologist at the VMware Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab at Stanford University and the lead researcher for Sheryl Sandberg’s bestseller Lean In.

Conversely, women who get noticed for their high performance and technical skills are often viewed with suspicion and resentment. They may be denied opportunities to advance at work because they’re seen as lacking the people skills necessary for leadership roles. And if they do manage to get promoted, they’re likely to be deemed difficult.

This puts women in a maddening double bind: Is it better to seem nice and be underestimated, or to seem smart and be disliked? Carly Fiorina, the former head of Hewlett-Packard and 2016 Republican presidential candidate, summarized one version of this paradox in her 2006 memoir, writing that throughout Silicon Valley, during her tenure at HP and long after, “I was routinely referred to as either a bimbo or a bitch.”

The ease with which our culture deems powerful women to be cold and calculating is so well-documented that it’s become a cultural trope. “I don’t hate women candidates—I just hated Hillary and coincidentally I’m starting to hate Elizabeth Warren,” a recent headline on the humor site McSweeney’s declares.

But the tendency to treat warmth as a sign of weakness is also a serious issue. For every supposedly unlikable Hillary Clinton or Elizabeth Warren, there are scores of women who’ve been socialized to conduct themselves in a warm, helpful, traditionally feminine manner. We just don’t know their names, because they’ve never been offered a leadership position in the first place. “Friendly, warm people, they can get sidelined pretty easily and not be seen as power players or go-to people,” says Cooper.

Conflating warmth and weak performance puts women at a disadvantage. And it has big ramifications for everyone else, too. Kindness, because it is a quality that’s closely linked with stereotypical femininity, has been systematically devalued in contemporary office cultures and in American culture more broadly. This misconception has made our workplaces, and our society, less functional, less moral, and ultimately, less human.

Either, but not both

Whether it’s better to be perceived as kind or competent is not a dilemma faced only by women. Research shows that people prone to stereotyping by others—whether based on their gender, race, religion, nationality, profession, or socioeconomic status—are especially vulnerable to the phenomenon known as the warmth-competence tradeoff, as identified by social-science researchers Amy Cuddy, Peter Glick, and Anna Beninger in a 2011 paper (pdf) published in Research in Organizational Behavior.

The researchers note that stereotypes about so-called “model minorities”—such as Asian and Jewish people—often characterize members of these groups as “competent but cold.” Meanwhile, groups that are frequently seen as “lower status”—such as working moms, the elderly, and people with disabilities—are perceived as warm but not necessarily competent.

Is it possible to be perceived as both warm and competent, and admired for possessing both qualities? Certainly. “But comparison changes everything,” Princeton psychologist Susan T. Fiske writes in her 2012 book, Envy Up, Scorn Down: How Status Divides Us.

Fiske explains that typically, when we think well of someone for displaying a certain trait—say, a barista who always gives us an enthusiastic greeting at the coffee shop—we’ll assume they have many other positive qualities as well. That barista is so friendly, we think, so he probably loves his job, which means he’s a hard worker, which means he’s devoted to his family. And so on. This is known as the “halo effect.”

But in a comparative context, we’re more prone to box people in, Fiske writes. “Somebody has to be better and somebody worse; usually, each side is better in particular ways and worse in others, that is, distinct domains: high on either warmth or competence, but not on both.”

And so the warmth-competence effect serves as a kind of psychological sorting mechanism when we’re trying to weigh people against one another and decide who deserves an award, or a raise, or a job, or our votes.

Sometimes it’s hard to figure out who to pick in such situations, and it makes sense that our brains try to simplify matters by slotting candidates into certain categories. But there’s no logical grounding to the idea that a friendly person is going to be dumber than a cold one. We’re just falling back on a pattern of thinking that gives the most generous assessments to members of high-status groups—that is to say, in the context of many workplace situations, white men.

Forbes’ recent list of the 100 most innovative leaders, featuring 99 men and one woman, offers a prime example of how this bias plays out every day. We root for the success of people who seem similar to us. So long as white men have the most influence in assessing the achievements of others, they’ll shape the cultural conversation to gaze most kindly upon people who remind them of themselves. (Note: the Forbes list was compiled by four men; the ranking was predicated in part on the executives’ media reputations as innovators, which demonstrably favors men; and it was published in a magazine that is led by a man.)

On the bright side, there is reason to believe that the general tendency to regard women as inherently less competent than men is changing. A recent meta-analysis of 16 polls of Americans, published in the journal American Psychologist, found that women are, at long last, generally perceived as being just as competent as men. According to the American Psychological Association, in 1946, just 35% of Americans thought men and women were equally intelligent. But by 2018, “86% believed men and women were equally intelligent, 9% believed women were more intelligent and only 5% believed men were more intelligent.”

Glick, a professor of social sciences at Lawrence University whose research often focuses on sexism in the workplace, says it’s true that perceptions of women’s intelligence are improving. But when the question of warmth is raised, women “can still get assimilated into this warm but not competent stereotype.”

“If you write a recommendation letter and you praise a woman for her warmth, what are you implying?” he says. “People read into it.” The implication: “Oh, she’s nice, but she doesn’t have what it takes.”

Being nice in a dog-eat-dog world

The women who get dinged for not being nice enough at work are often, in fact, perfectly friendly and collegial, according to Margarita Mayo, a professor of leadership and organizational behavior at IE Business School in Madrid. Because women who display the quality of ambition tend to be perceived as uncaring, women have to perform extra-super-levels of niceness with a cherry on top in order to be acknowledged as such.

In Mayo’s first job in academia, she recalls, her male colleagues were perceived as helpful simply for holding meetings with doctoral students at all. The women on the faculty were expected to devote far more of their time to students, attending special breakfasts and dinners.

Such expectations can put women in a lose-lose situation, as illuminated by a recent lawsuit brought by one lawyer against her ex-employer. The lawyer, Nancy Saltzman, reported that her former CEO demanded she cut the cake at a company celebration because she was one of the “ladies.” Refusing would have made her look hostile, so she complied, knowing she’d been forced into a position that undermined her authority.

These different expectations for men and women are “similar to what happens at home,” Mayo says. If a mother takes a sick child to the doctor, she’s simply fulfilling basic expectations of parenthood. “But if the father takes the child to the doctor, he gets, Oh, my god, such a great dad.“

But why is it that so many workplaces interpret pro-social behavior as a sign of weakness in the first place? Part of the reason has to do with the assumption that people who are nice don’t know how to stand up for themselves. “When you’re likable and agreeable, if you think about the exaggerated version of those traits, you’re a people-pleaser, you get tread on, you’re accommodating,” says Glick. “And what happens to the accommodating person? They get piled on.”

In a patriarchal society, niceness, compassion, and kindness— stereotypically feminine traits—are bound to be culturally undervalued. The result is that many workplaces instead place a premium on stereotypically male qualities like dominance, resulting in “masculinity contest cultures,” a term coined by Glick, Cooper, and Jennifer Berdahl, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s sociology department. Writing in the Harvard Business Review, they explain: “This kind of culture endorses winner-take-all competition, where winners demonstrate stereotypically masculine traits such as emotional toughness, physical stamina, and ruthlessness. It produces organizational dysfunction, as employees become hyper competitive to win.”

Masculinity contest cultures make everyone unhappy, leading to higher rates of burnout, turnover, illness, and depression. “It’s pretty miserable for everyone; even the people who win, win at a high cost,” says Glick. And it’s ultimately terrible for business. Glick, Cooper, and Berdahl point to Uber as an illustration of how sexual harassment and other forms of misconduct can thrive in workplaces that prize aggression and competition over listening and cooperation. Under Uber’s ousted CEO Travis Kalanick, Glick says, “people would openly brag about withholding critical information to sabotage their bosses and try to their take jobs. This is not a functional workplace.”

Workplace cultures that treat warmth as a sign of incompetency do so because they see femininity itself as a weakness. That doesn’t just set women up to fail—it sets the organization up to fail, too.

The praiseworthy performance

Say that management takes a good, hard look in the mirror and realizes that people at the top have been perpetuating a culture in which nice people, and nice women in particular, get the shaft. What’s to be done about it?

For one thing, managers should think critically about the kind of praise that they bestow on women, and whether it may reflect certain assumptions about warmth and competence. One study of 81,000 performance evaluations of military leaders found that men were most frequently praised for being “analytical” and “competent,” while women were complimented on being “compassionate” and “enthusiastic.”

“If you understand women aren’t as readily granted competence as men, especially in science, tech, engineering, math, and leadership, you do want to say how nice of a person they are, because they are, and you really need to talk about their competence,” says Stanford’s Cooper. “Men are more often described with standout adjectives like ‘game-changer’ or ‘brilliant,’ and that helps them. Managers need to be cognizant of that: If I’m doing that for the men I’m sponsoring, I should really be doing that for the women as well.”

More broadly, organizations that say they prize collaboration and generosity need to find ways to reward and incentivize collaborative and generous behaviors. Mayo suggests “making it a requirement to do the helping and be a good citizen.” The Australian software company Atlassian, for example, recently implemented performance reviews that evaluate employees not just on their individual achievements, but on their contributions to their teammates and to company culture. It’s a refreshing idea. That said, Glick notes that because collaboration is a subjective measure upon which to be evaluated, there’s still plenty of room for performance reviews to continue holding women to a higher standard than men when it comes to helpfulness.

That’s why it’s important to ensure that women who are known within an organization for their enthusiasm and kindness are also getting a shot at the kinds of high-profile assignments that lead to internal and external recognition, promotions, and raises. “The helping work is backstage, which is really unfortunate because women don’t get visibility,” notes Mayo.

The various researchers interviewed for this article were unanimous in saying that the onus should not be on individual women to solve warmth-competency biases. “Ultimately, we can all think about how people are perceiving us at the margins, in certain instances we can even be more strategic, but it’s exhausting and there’s only so much we can control,” says Cooper. “There’s a cost to always having to strategize.”

Yes, a woman who fears that she’s getting passed over for promotions at work because she’s too nice to be perceived as leadership material can try to set clear expectations with her manager about the specific benchmarks she’ll have to hit in order to level up. But there’s no guarantee that professional prejudices won’t still come into play. That’s why the New York Times’ Jessica Bennett recently expressed fatigue about the expectation that women perform “gender judo” in order to navigate stereotypes, asking, “What if we tried to change the system, and not ourselves?”

Learning to value kindness

Changing the system, of course, is a big job. It involves dismantling rigid notions of masculinity and femininity that work against all of us. Samuel Culbert, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles Anderson School of Management and the author of Good People, Bad Managers, articulates the task for forward-thinking workplaces this way: It’s “how you get people and processes, in a competitive environment, to own up to the fact that they’re imperfect, to not get so insecure that they have to point out other people’s imperfections, and to create a compensation structure where people have everything to gain by helping others, and nothing to gain by competing?”

Culbert names Salesforce and Starbucks as two companies that are attempting to create this kind of environment. Another, perhaps more surprising example is the oil and gas giant Shell. Back in the 1990s, oil-rig workers at Shell were steeped in the performance of masculine toughness. Then, as detailed on the podcast Invisibilia, the company began offering seminars designed to help workers open up.

The goal of teaching the workers to express their feelings and treat one another with empathy wasn’t just about helping them to become more fully realized people, although this was an added bonus. Rather, the point was to get them to a place where they were okay being vulnerable with one another and admitting to mistakes—necessary skills in a dangerous job when you’re trying to keep people safe. Shell’s company-wide accident rate fell by 84% after the training, while productivity and efficiency soared.

The lesson of Shell suggests that helping boys to develop emotional intelligence while they’re young could go a long way toward changing the workplace dynamics of the future. “The rules of society mean that boys have to censor what they express, and sometimes the only way to do that is to convince yourself that you’re not feeling what you’re feeling,” the psychologist Michael Reichart, founding director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Boys’ and Girls’ Lives and author of the new book How to Raise a Boy, recently told The Atlantic. “And if I’ve cut myself off from my own feelings, I’m going to be less perceptive about what you’re feeling, which means I’m going to behave in a relationship with less skill and deftness.”

But teach boys to value their emotions, and they’ll be more likely to grow up into the kind of people who take new hires under their wing or volunteer to head up mentoring programs at work. That both lessens the pressure on women to take on disproportionate amounts of emotional labor, and helps to alter perceptions of warmth and friendliness as traits that are associated with any particular gender.

In the 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Clementine (Kate Winslet) doesn’t want to be called nice because she thinks nice people are boring, or pandering, or cowardly. She’s internalized the same stereotypes that made me launch, uncharacteristically, into a not-so-nice diatribe last year when a colleague told me that my niceness was my biggest strength.

But perhaps Clementine and I had gotten things wrong. As Glick says, “it’s nice to be nice”—it’s just unfair to be penalized for it. But in a world where both men and women are expected to be considerate and generous and kind to their colleagues? Where a person’s warmth isn’t treated as a strike against their intelligence, but as an unqualified asset that, more often than not, goes hand in hand with talent? Now that sounds pretty nice.

Correction: This story previously identified Jennifer Berdahl as a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business. She is a professor at the University of British Columbia’s sociology department.

bad word — перевод на русский

No, no, Reverend. The point is he said a bad word.

Смысл в том, что он сказал плохое слово.

Every time he said a bad word he put in a quarter.

За каждое плохое слово он туда клал монетку.

Where did a nice little boy like you learn such a bad word like that?

Где такой хороший мальчик узнал такое плохое слово?

That’s a bad word at your place.

Это плохое слово в вашей среде.

Crazy isn’t a bad word.

Это не плохое слово, это можно.

Показать ещё примеры для «плохое слово»…

Obviously I can’t go into details, but the fact is he never said a bad word about her.

Подробности я конечно не могу разглашать, но он ни разу дурного слова о ней не сказал.

I’ve interviewed three men from Shaw’s regiment, two political opponents and an adjunct who was dishonorably discharged, and none had a bad word to say.

Я опросил трех человек из полка Шоу, двух политических оппонентов и помощника, которого с позором уволили, и ни один не сказал и дурного слова.

Never say a bad word, okay?

Ни одного дурного слова от тебя. Я помню это, Корбет.

But nobody says a bad word about him.

Никто не говорит ни слова дурного о нем.

Sir, if you say another bad word about her, I’m gonna «whoosh-whoosh» you off that chair.

Сэр, если вы скажете о ней ещё хоть одно дурное слово, я вас вышибу из этого кресла.

Отправить комментарий

Пословицы и поговорки – это отражение народной мысли, установок, моральных ценностей. Обычно они имеют аналоги в других языках, поскольку воспроизводят “простые истины”, свойственные любому человеку каждой нации. Пословица может иметь другие образы, но будет доносить тот же смысл:

| Английские пословицы | Русские эквиваленты английских пословиц |

| When in Rome, do as the Romans do. | В чужой монастырь со своим уставом не ходят. |

| The early bird catches the worm. | Кто рано встаёт – тому Бог подает. |

| Too many cooks spoil the broth. | У семи нянек дитя без глазу. |

⠀

Но есть высказывания, которые вообще не имеют эквивалента в русском языке. Такие пословицы в наибольшей степени отражают отличия менталитета, поэтому составляют для нас особый интерес.

Кстати, сегодня мы узнаем не только смысл этих английских пословиц, но и связанные с ними занимательные истории.

Обрати внимание: если вдруг ты не согласен с описанным примером и точно знаешь русский аналог, то обязательно пиши об этом в комментариях – подискутируем! 🙂

Уникальное наследие: пословицы на английском языке с переводом

1. If you can’t be good, be careful.

Дословный перевод: Если не можешь быть хорошим, будь осторожен.

Если ты собираешься делать безнравственные вещи, убедись, что они не опасны для тебя или общества. Когда ты планируешь сделать что-то аморальное, удостоверься, что об этом никто не узнает.

Первое упоминание именно этой формулировки датируется 1903-м годом, но смысл выражения намного старше и берет свое начало из латинской пословицы “Si non caste, tamen caute” (если не целомудренно, то по крайней мере осторожно).

2. A volunteer is worth twenty pressed men.

Дословный перевод: Один доброволец стоит двадцати принужденных.

Значение пословицы по сути прямое: даже маленькая группа людей может быть полезнее, если у нее есть энтузиазм, стремление и т.д. Зародилась эта пословица в начале 18-го века.

В то время Королевский флот имел группу матросов, вооруженных дубинками, чья цель была “насобирать” моряков на флот. Они могли делать это, рассказывая о небывалых преимуществах службы, или же просто силой (все же вооружены дубинками они были неспроста).

Такое стечение обстоятельств не делало принужденного хорошим моряком. Отсюда и “вытекло” это умозаключение.

Заметь, что в этой пословице можно менять соотношение цифр:

100 volunteers are worth 200 press’d men.

One volunteer is worth two pressed men

и т.д.

3. Suffering for a friend doubleth friendship.

Дословный перевод: Страдание за друга удваивает дружбу.

Значение этой шотландской пословицы понятно без особых объяснений. Казалось бы, в русском языке есть довольно похожая пословица “друг познается в беде”. При этом очень интересен сам смысл “страдания за друга”. Если в русском варианте говорится о том, чтобы не отвернуться от друга и помочь ему в трудной ситуации, то здесь именно страдать вместе с ним, тем самым усиливая дружбу.

Еще одна интересная с точки зрения образов английская пословица о дружбе: Friends are made in wine and proven in tears (дружба рождается в вине, а проверяется в слезах).

Также читайте: Какой он — живой английский язык?

4. A woman’s work is never done.

Дословный перевод: Женский труд никогда не заканчивается.

Ну вот и о нашей нелегкой женской доле английские пословицы позаботились 🙂 Выражение пошло от старинного двустишия:

Man may work from sun to sun,

But woman’s work is never done.

Получается, значение пословицы в том, что женские дела (в отличие от мужских) длятся бесконечно. Видно это из примера:

“A woman’s work is never done!”, said Leila. She added: “As soon as I finish washing the breakfast dishes, it’s time to start preparing lunch. Then I have to go shopping and when the kids are back home I have to help them with their homework.”

(“Женский труд никогда не заканчивается!”, – Сказала Лейла. Она добавила: “Как только я заканчиваю мыть посуду после завтрака, приходит время готовить обед. Потом я должна идти по магазинам и, когда дети возвращаются домой, я должна помогать им с домашним заданием”.)

5. Comparisons are odious / odorous.

Дословный перевод: Сравнения отвратительны / воняют.

Люди должны оцениваться по их собственным заслугам, не стоит кого-либо или что-либо сравнивать между собой.

Два варианта пословица имеет не просто так. Первый вариант (Comparisons are odious) очень древний, и впервые он был запечатлен еще в 1440 году. А вот измененный вариант (Comparisons are odorous) был “создан” Шекспиром и использован им в пьесе “Много шума из ничего”.

6. Money talks.

Дословный перевод: Деньги говорят (сами за себя).

Значение – деньги решают все. Происхождение выражения является предметом споров среди лингвистов. Одни считают, что пословица зародилась в Америке 19-го века, другие – что в средневековой Англии.

Кстати, пословица использована в названии песни австралийской рок-группы AC/DC.

7. Don’t keep a dog and bark yourself.

Дословный перевод: Не держи собаку, если лаешь сам.

Значение этой английском пословицы: не работай за своего подчиненного. Высказывание очень древнее: первое упоминание зафиксировано еще в 1583 году.

По поводу отсутствия аналога: в разных источниках дана разная информация. Кто-то согласен с тем, что аналогов в русском языке нет, другие в качестве эквивалента предлагают пословицу:

За то собаку кормят, что она лает.

Однако, в Большом словаре русских пословиц такой пословицы о собаке нет вообще. Возможно, то что предлагают нам в качестве альтернативы, это адаптированный перевод именно английской пословицы (такое бывает).

8. Every man has his price.

Дословный перевод: У каждого есть своя цена.

Согласно этой пословице, подкупить можно любого, главное предложить достаточную цену. Наблюдение впервые зафиксировано в 1734 году, но, скорее всего, имеет и более давнюю историю.

Также читайте: История Англии: список лучших документальных фильмов

9. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

Дословный перевод: Подражание – самая искренняя форма лести.

Значение пословицы прямое. Эта формулировка восходит к началу 19-го века. Но сама мысль еще древнее и встречалась в текстах 18-го века, например, в 1714 году у журналиста Юстаса Баджелла:

Imitation is a kind of artless Flattery (Имитация является своего рода бесхитростной лестью).

10. It’s better to light a candle than curse the darkness.

Дословный перевод: Лучше зажечь свечу, чем проклинать темноту.

Вопрос об аналоге снова спорен: в некоторых источниках, где даны английские пословицы с переводом на русский, эквивалентом называют:

Лучше пойти и плюнуть, чем плюнуть и не пойти.

Хочу с этим поспорить. Значение русской пословицы: лучше сделать, чем жалеть, что не сделал. Смысл английской – лучше исправить положение, чем жаловаться на него. Лично мне смысловая составляющая про жалобы кажется первостепенной, поэтому приравнивать эти пословицы я бы не стала.

11. Stupid is as stupid does

Дословный перевод: Глуп тот, кто глупо поступает.

На самом деле это не совсем “народная пословица”, а фраза, которой Форест Гамп отбивался от назойливых вопросов о своем интеллекте:

Фраза ушла в народ 🙂 Прародитель этого выражения – пословица “Handsome is as handsome does” (красив тот, кто красиво поступает), уже имеющая аналог в русском языке: “Не тот хорош, кто лицом пригож, а тот хорош, кто для дела гож”.

Также читайте: Игра престолов с Lingualeo, или Hear me roar

12. You can’t make bricks without straw

Дословный перевод: Нельзя сделать кирпич без соломы.

Опять же в некоторых источниках в качестве аналога указывается русское “без труда не вытащишь и рыбку из пруда”. При этом английская пословица говорит не о трудолюбии, а о невозможности выполнить задачу без необходимых материалов.

“It’s no good trying to build a website if you don’t know any html, you can’t make bricks without straw.” (Не пытайся создать веб-сайт, если ты не знаешь HTML: ты не можешь делать кирпичи без соломы).

Согласно википедии выражение берет начало из библейского сюжета, когда Фараон в наказание запрещает давать израильтянам солому, но приказывает делать то же количество кирпичей, как и раньше.

Где искать пословицы и поговорки на английском языке по темам?

Возможно, это не все высказывания, не имеющие русских аналогов, ведь английских пословиц (и их значений) огромное множество. Кстати, ты вполне можешь поискать их самостоятельно в нашей Библиотеке материалов по запросу “proverb”, чтобы насытить свою английскую речь чудесными выражениями. Успехов! 🙂