Asked by: Pietro Larkin

Score: 4.8/5

(71 votes)

Meta must be combined with a root word, either with a hyphen or by concatenation. Therefore, the only proper terms are meta-data and metadata. … Because the term ‘metadata’ is a trademark of The Metadata Company, DAMA specifically uses the term meta-data.

Is metadata one word or two?

agree metadata is one word.

How do you spell meta data?

The short answer is there is no difference – it is simply a matter of the correct spelling of “metadata“. Call it what you will, taxonomy, meta data or metainformation, it is all metadata.

How do you use metadata in a sentence?

A number of metadata formats currently exist, influenced by the needs of the communities in which they emerged. The nationwide metadata enhanced search engine proved infeasible, federated metadata initiatives were not. From the conceptual model, a database design can be derived, or a definition of metadata .

What is an example of metadata?

Metadata is data about data. … A simple example of metadata for a document might include a collection of information like the author, file size, the date the document was created, and keywords to describe the document. Metadata for a music file might include the artist’s name, the album, and the year it was released.

36 related questions found

How do I view metadata in a Word document?

How do I view metadata of a Microsoft Word document?

- Locate the Word document you wish to view the metadata of.

- Open the document and click the “File” dropdown from the upper left of the screen.

- In the upper left, click the “info” tab.

- In the lower right hand corner, click the “Show All Properties” link.

Where is metadata stored?

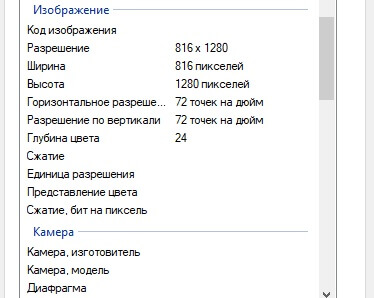

Metadata is stored in two main places: Internally – embedded in the image file, in formats such as JPEG, DNG, PNG, TIFF … Externally – outside the image file in a digital asset management system (DAM) or in a “sidecar” file (such as for XMP data) or an external news exchange format document as specified by the IPTC.

What is metadata one sentence?

The definition of metadata is information about other information. An example of metadata is a card catalog in a library, giving information about books. noun. Data that describes other data, as in describing the origin, structure, or characteristics of computer files, webpages, databases, or other digital resources.

What is the word metadata mean?

: data that provides information about other data.

What is a metadata format?

The first purpose of metadata formats still is the resource description: they allow us to record the ‘formal’ characteristics of documents: title, authors, publication year, etc. Most formats have one or more fields in which something about the subject, the content of a document, can be stored.

What is metadata and its types?

So, if you’re not sure what the difference is between structural metadata, administrative metadata, and descriptive metadata (spoiler alert: those are the three main types of metadata), let’s clear up the confusion.

What is meta gaming?

In essence, a «meta» in gaming terminology is a generally agreed upon strategy by the community. Said strategy is considered to be the most optimal way to win/ has the best performance at a specific task. Some people have defined meta as an acronym meaning “most effective tactics available”.

What is metadata why is it important?

Metadata ensures that we will be able find data, use data, and preserve and re-use data in the future. Finding Data: Metadata makes it much easier to find relevant data. … Metadata also makes text documents easier to find because it explains exactly what the document is about.

What is another name for metadata?

In this page you can discover 16 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for metadata, like: schema, meta-data, z39. 50, xml, mpeg-7, repository, sgml, schemas, oai, annotation and rdf.

What are the three types of metadata?

There are THREE (3) different types of metadata: descriptive, structural, and administrative. Descriptive: describes a resource for purposes such as discovery and identification. It can include elements such as title, abstract, author, and keywords.

What is metadata in DBMS?

Metadata in DBMS is the data (details/schema) of any other data. It can also be defined as data about data. The word ‘Meta’ is the prefix that is generally the technical term for self-referential. In other words, we can say that Metadata is the summarized data for the contextual data.

Can you fake metadata?

Metadata, like the photo itself, can be manipulated and because images are easy to duplicate it’s possible that you are looking at an unedited image but it doesn’t have the metadata attached anymore.

Can metadata be used as evidence?

Metadata often counts as substantive evidence. For example, comments in a Word document can show the drafter’s intent. The same with tracked changes and formulas in Excel. Further, metadata is extremely useful for authenticating evidence because it often shows the author and creation date for files.

What is the difference between data and metadata?

Data is a collection of information such as observations, measurements, facts, and descriptions of certain things. … On the other hand, Metadata, often defined as “data on data”, refers to specific details on these data. It provides granular information on one specific data such as file type, format, origin, date, etc.

What is process metadata?

Process metadata is data that defines and describes the characteristics of other system elements (processes, business rules, programs, jobs, tools, etc.).

What is metadata HTML?

The <meta> tag defines metadata about an HTML document. Metadata is data (information) about data. … Metadata will not be displayed on the page, but is machine parsable. Metadata is used by browsers (how to display content or reload page), search engines (keywords), and other web services.

What is metadata in email?

Email records include fields of information such as the sender, recipient, date, and subject that may be considered to be a form of metadata. … It is also possible for an email to be sent from an address associated with several people, such as a group or a team, or sent by one person on behalf of another.

What should metadata tell you about the data?

Data that provide information about other data. Metadata summarizes basic information about data, making finding & working with particular instances of data easier. Metadata can be created manually to be more accurate, or automatically and contain more basic information.

Where does the metadata gets stored in Snowflake?

Snowflake automatically generates metadata for files in internal (i.e. Snowflake) stages or external (Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage, or Microsoft Azure) stages. This metadata is “stored” in virtual columns that can be: Queried using a standard SELECT statement.

Is metadata a file plan?

This will allow staff to file and retrieve information efficiently as well as allowing the inquiry secretary to control access to information. A file plan should: … allow associated metadata to be captured and managed – metadata is technical or cataloguing information about digital or paper records.

In the 21st century, metadata typically refers to digital forms, but traditional card catalogs contain metadata, with cards holding information about books in a library (author, title, subject, etc.).

Metadata can come in different layers: This physical herbarium record of Cenchrus ciliaris consists of the specimens as well as metadata about them, while the barcode points to a digital record with metadata about the physical record.

Metadata is «data that provides information about other data»,[1] but not the content of the data, such as the text of a message or the image itself. There are many distinct types of metadata, including:

- Descriptive metadata – the descriptive information about a resource.[vague] It is used for discovery and identification. It includes elements such as title, abstract, author, and keywords.

- Structural metadata – metadata about containers of data and indicates how compound objects are put together, for example, how pages are ordered to form chapters. It describes the types, versions, relationships, and other characteristics of digital materials.[2]

- Administrative metadata[3] – the information to help manage a resource, like resource type, permissions, and when and how it was created.[4]

- Reference metadata – the information about the contents and quality of statistical data.

- Statistical metadata[5] – also called process data, may describe processes that collect, process, or produce statistical data.[6]

- Legal metadata – provides information about the creator, copyright holder, and public licensing, if provided.

Metadata is not strictly bound to one of these categories, as it can describe a piece of data in many other ways.

History[edit]

Metadata has various purposes. It can help users find relevant information and discover resources. It can also help organize electronic resources, provide digital identification, and archive and preserve resources. Metadata allows users to access resources by «allowing resources to be found by relevant criteria, identifying resources, bringing similar resources together, distinguishing dissimilar resources, and giving location information».[7] Metadata of telecommunication activities including Internet traffic is very widely collected by various national governmental organizations. This data is used for the purposes of traffic analysis and can be used for mass surveillance.[8]

Metadata was traditionally used in the card catalogs of libraries until the 1980s when libraries converted their catalog data to digital databases.[9] In the 2000s, as data and information were increasingly stored digitally, this digital data was described using metadata standards.[10]

The first description of «meta data» for computer systems is purportedly noted by MIT’s Center for International Studies experts David Griffel and Stuart McIntosh in 1967: «In summary then, we have statements in an object language about subject descriptions of data and token codes for the data. We also have statements in a meta language describing the data relationships and transformations, and ought/is relations between norm and data.»[11]

Unique metadata standards exist for different disciplines (e.g., museum collections, digital audio files, websites, etc.). Describing the contents and context of data or data files increases its usefulness. For example, a web page may include metadata specifying what software language the page is written in (e.g., HTML), what tools were used to create it, what subjects the page is about, and where to find more information about the subject. This metadata can automatically improve the reader’s experience and make it easier for users to find the web page online.[12] A CD may include metadata providing information about the musicians, singers, and songwriters whose work appears on the disc.

In many countries, government organizations routinely store metadata about emails, telephone calls, web pages, video traffic, IP connections, and cell phone locations.[13]

Definition[edit]

Metadata means «data about data». Metadata is defined as the data providing information about one or more aspects of the data; it is used to summarize basic information about data that can make tracking and working with specific data easier.[14] Some examples include:

- Means of creation of the data

- Purpose of the data

- Time and date of creation

- Creator or author of the data

- Location on a computer network where the data was created

- Standards used

- File size

- Data quality

- Source of the data

- Process used to create the data

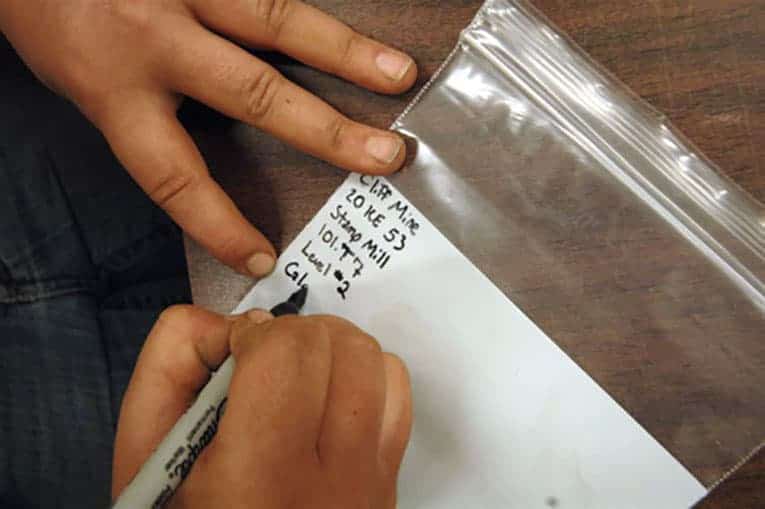

For example, a digital image may include metadata that describes the size of the image, its color depth, resolution, when it was created, the shutter speed, and other data.[15] A text document’s metadata may contain information about how long the document is, who the author is, when the document was written, and a short summary of the document. Metadata within web pages can also contain descriptions of page content, as well as key words linked to the content.[16] These links are often called «Metatags», which were used as the primary factor in determining order for a web search until the late 1990s.[16] The reliance on metatags in web searches was decreased in the late 1990s because of «keyword stuffing»,[16] whereby metatags were being largely misused to trick search engines into thinking some websites had more relevance in the search than they really did.[16]

Metadata can be stored and managed in a database, often called a metadata registry or metadata repository.[17] However, without context and a point of reference, it might be impossible to identify metadata just by looking at it.[18] For example: by itself, a database containing several numbers, all 13 digits long could be the results of calculations or a list of numbers to plug into an equation — without any other context, the numbers themselves can be perceived as the data. But if given the context that this database is a log of a book collection, those 13-digit numbers may now be identified as ISBNs — information that refers to the book, but is not itself the information within the book. The term «metadata» was coined in 1968 by Philip Bagley, in his book «Extension of Programming Language Concepts» where it is clear that he uses the term in the ISO 11179 «traditional» sense, which is «structural metadata» i.e. «data about the containers of data»; rather than the alternative sense «content about individual instances of data content» or metacontent, the type of data usually found in library catalogs.[19][20] Since then the fields of information management, information science, information technology, librarianship, and GIS have widely adopted the term. In these fields, the word metadata is defined as «data about data».[21] While this is the generally accepted definition, various disciplines have adopted their own more specific explanations and uses of the term.

Slate reported in 2013 that the United States government’s interpretation of «metadata» could be broad, and might include message content such as the subject lines of emails.[22]

Types[edit]

While the metadata application is manifold, covering a large variety of fields, there are specialized and well-accepted models to specify types of metadata. Bretherton & Singley (1994) distinguish between two distinct classes: structural/control metadata and guide metadata.[23] Structural metadata describes the structure of database objects such as tables, columns, keys and indexes. Guide metadata helps humans find specific items and is usually expressed as a set of keywords in a natural language. According to Ralph Kimball, metadata can be divided into three categories: technical metadata (or internal metadata), business metadata (or external metadata), and process metadata.

NISO distinguishes three types of metadata: descriptive, structural, and administrative.[21] Descriptive metadata is typically used for discovery and identification, as information to search and locate an object, such as title, authors, subjects, keywords, and publisher. Structural metadata describes how the components of an object are organized. An example of structural metadata would be how pages are ordered to form chapters of a book. Finally, administrative metadata gives information to help manage the source. Administrative metadata refers to the technical information, such as file type, or when and how the file was created. Two sub-types of administrative metadata are rights management metadata and preservation metadata. Rights management metadata explains intellectual property rights, while preservation metadata contains information to preserve and save a resource.[7]

Statistical data repositories have their own requirements for metadata in order to describe not only the source and quality of the data[5] but also what statistical processes were used to create the data, which is of particular importance to the statistical community in order to both validate and improve the process of statistical data production.[6]

An additional type of metadata beginning to be more developed is accessibility metadata. Accessibility metadata is not a new concept to libraries; however, advances in universal design have raised its profile.[24]: 213–214 Projects like Cloud4All and GPII identified the lack of common terminologies and models to describe the needs and preferences of users and information that fits those needs as a major gap in providing universal access solutions.[24]: 210–211 Those types of information are accessibility metadata.[24]: 214 Schema.org has incorporated several accessibility properties based on IMS Global Access for All Information Model Data Element Specification.[24]: 214 The Wiki page WebSchemas/Accessibility lists several properties and their values. While the efforts to describe and standardize the varied accessibility needs of information seekers are beginning to become more robust, their adoption into established metadata schemas has not been as developed. For example, while Dublin Core (DC)’s «audience» and MARC 21’s «reading level» could be used to identify resources suitable for users with dyslexia and DC’s «format» could be used to identify resources available in braille, audio, or large print formats, there is more work to be done.[24]: 214

Structures[edit]

Metadata (metacontent) or, more correctly, the vocabularies used to assemble metadata (metacontent) statements, is typically structured according to a standardized concept using a well-defined metadata scheme, including metadata standards and metadata models. Tools such as controlled vocabularies, taxonomies, thesauri, data dictionaries, and metadata registries can be used to apply further standardization to the metadata. Structural metadata commonality is also of paramount importance in data model development and in database design.

Syntax[edit]

Metadata (metacontent) syntax refers to the rules created to structure the fields or elements of metadata (metacontent).[25] A single metadata scheme may be expressed in a number of different markup or programming languages, each of which requires a different syntax. For example, Dublin Core may be expressed in plain text, HTML, XML, and RDF.[26]

A common example of (guide) metacontent is the bibliographic classification, the subject, the Dewey Decimal class number. There is always an implied statement in any «classification» of some object. To classify an object as, for example, Dewey class number 514 (Topology) (i.e. books having the number 514 on their spine) the implied statement is: «<book><subject heading><514>». This is a subject-predicate-object triple, or more importantly, a class-attribute-value triple. The first 2 elements of the triple (class, attribute) are pieces of some structural metadata having a defined semantic. The third element is a value, preferably from some controlled vocabulary, some reference (master) data. The combination of the metadata and master data elements results in a statement which is a metacontent statement i.e. «metacontent = metadata + master data». All of these elements can be thought of as «vocabulary». Both metadata and master data are vocabularies that can be assembled into metacontent statements. There are many sources of these vocabularies, both meta and master data: UML, EDIFACT, XSD, Dewey/UDC/LoC, SKOS, ISO-25964, Pantone, Linnaean Binomial Nomenclature, etc. Using controlled vocabularies for the components of metacontent statements, whether for indexing or finding, is endorsed by ISO 25964: «If both the indexer and the searcher are guided to choose the same term for the same concept, then relevant documents will be retrieved.»[27] This is particularly relevant when considering search engines of the internet, such as Google. The process indexes pages and then matches text strings using its complex algorithm; there is no intelligence or «inferencing» occurring, just the illusion thereof.

Hierarchical, linear, and planar schemata[edit]

Metadata schemata can be hierarchical in nature where relationships exist between metadata elements and elements are nested so that parent-child relationships exist between the elements.

An example of a hierarchical metadata schema is the IEEE LOM schema, in which metadata elements may belong to a parent metadata element.

Metadata schemata can also be one-dimensional, or linear, where each element is completely discrete from other elements and classified according to one dimension only.

An example of a linear metadata schema is the Dublin Core schema, which is one-dimensional.

Metadata schemata are often 2 dimensional, or planar, where each element is completely discrete from other elements but classified according to 2 orthogonal dimensions.[28]

Granularity[edit]

The degree to which the data or metadata is structured is referred to as «granularity». «Granularity» refers to how much detail is provided. Metadata with a high granularity allows for deeper, more detailed, and more structured information and enables a greater level of technical manipulation. A lower level of granularity means that metadata can be created for considerably lower costs but will not provide as detailed information. The major impact of granularity is not only on creation and capture, but moreover on maintenance costs. As soon as the metadata structures become outdated, so too is the access to the referred data. Hence granularity must take into account the effort to create the metadata as well as the effort to maintain it.

Hypermapping[edit]

In all cases where the metadata schemata exceed the planar depiction, some type of hypermapping is required to enable display and view of metadata according to chosen aspect and to serve special views. Hypermapping frequently applies to layering of geographical and geological information overlays.[29]

Standards[edit]

International standards apply to metadata. Much work is being accomplished in the national and international standards communities, especially ANSI (American National Standards Institute) and ISO (International Organization for Standardization) to reach a consensus on standardizing metadata and registries. The core metadata registry standard is ISO/IEC 11179 Metadata Registries (MDR), the framework for the standard is described in ISO/IEC 11179-1:2004.[30] A new edition of Part 1 is in its final stage for publication in 2015 or early 2016. It has been revised to align with the current edition of Part 3, ISO/IEC 11179-3:2013[31] which extends the MDR to support the registration of Concept Systems.

(see ISO/IEC 11179). This standard specifies a schema for recording both the meaning and technical structure of the data for unambiguous usage by humans and computers. ISO/IEC 11179 standard refers to metadata as information objects about data, or «data about data». In ISO/IEC 11179 Part-3, the information objects are data about Data Elements, Value Domains, and other reusable semantic and representational information objects that describe the meaning and technical details of a data item. This standard also prescribes the details for a metadata registry, and for registering and administering the information objects within a Metadata Registry. ISO/IEC 11179 Part 3 also has provisions for describing compound structures that are derivations of other data elements, for example through calculations, collections of one or more data elements, or other forms of derived data. While this standard describes itself originally as a «data element» registry, its purpose is to support describing and registering metadata content independently of any particular application, lending the descriptions to being discovered and reused by humans or computers in developing new applications, databases, or for analysis of data collected in accordance with the registered metadata content. This standard has become the general basis for other kinds of metadata registries, reusing and extending the registration and administration portion of the standard.

The Geospatial community has a tradition of specialized geospatial metadata standards, particularly building on traditions of map- and image-libraries and catalogs. Formal metadata is usually essential for geospatial data, as common text-processing approaches are not applicable.

The Dublin Core metadata terms are a set of vocabulary terms that can be used to describe resources for the purposes of discovery. The original set of 15 classic[32] metadata terms, known as the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set[33] are endorsed in the following standards documents:

- IETF RFC 5013[34]

- ISO Standard 15836-2009[35]

- NISO Standard Z39.85.[36]

The W3C Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT)[37] is an RDF vocabulary that supplements Dublin Core with classes for Dataset, Data Service, Catalog, and Catalog Record. DCAT also uses elements from FOAF, PROV-O, and OWL-Time. DCAT provides an RDF model to support the typical structure of a catalog that contains records, each describing a dataset or service.

Although not a standard, Microformat (also mentioned in the section metadata on the internet below) is a web-based approach to semantic markup which seeks to re-use existing HTML/XHTML tags to convey metadata. Microformat follows XHTML and HTML standards but is not a standard in itself. One advocate of microformats, Tantek Çelik, characterized a problem with alternative approaches:

Here’s a new language we want you to learn, and now you need to output these additional files on your server. It’s a hassle. (Microformats) lower the barrier to entry.[38]

Use[edit]

Photographs[edit]

Metadata may be written into a digital photo file that will identify who owns it, copyright and contact information, what brand or model of camera created the file, along with exposure information (shutter speed, f-stop, etc.) and descriptive information, such as keywords about the photo, making the file or image searchable on a computer and/or the Internet. Some metadata is created by the camera such as, color space, color channels, exposure time, and aperture (EXIF), while some is input by the photographer and/or software after downloading to a computer.[39] Most digital cameras write metadata about the model number, shutter speed, etc., and some enable you to edit it;[40] this functionality has been available on most Nikon DSLRs since the Nikon D3, on most new Canon cameras since the Canon EOS 7D, and on most Pentax DSLRs since the Pentax K-3. Metadata can be used to make organizing in post-production easier with the use of key-wording. Filters can be used to analyze a specific set of photographs and create selections on criteria like rating or capture time. On devices with geolocation capabilities like GPS (smartphones in particular), the location the photo was taken from may also be included.

Photographic Metadata Standards are governed by organizations that develop the following standards. They include, but are not limited to:

- IPTC Information Interchange Model IIM (International Press Telecommunications Council)

- IPTC Core Schema for XMP

- XMP – Extensible Metadata Platform (an ISO standard)

- Exif – Exchangeable image file format, Maintained by CIPA (Camera & Imaging Products Association) and published by JEITA (Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association)

- Dublin Core (Dublin Core Metadata Initiative – DCMI)

- PLUS (Picture Licensing Universal System)

- VRA Core (Visual Resource Association)[41]

Telecommunications[edit]

Information on the times, origins and destinations of phone calls, electronic messages, instant messages, and other modes of telecommunication, as opposed to message content, is another form of metadata. Bulk collection of this call detail record metadata by intelligence agencies has proven controversial after disclosures by Edward Snowden of the fact that certain Intelligence agencies such as the NSA had been (and perhaps still are) keeping online metadata on millions of internet users for up to a year, regardless of whether or not they [ever] were persons of interest to the agency.

Video[edit]

Metadata is particularly useful in video, where information about its contents (such as transcripts of conversations and text descriptions of its scenes) is not directly understandable by a computer, but where an efficient search of the content is desirable. This is particularly useful in video applications such as Automatic Number Plate Recognition and Vehicle Recognition Identification software, wherein license plate data is saved and used to create reports and alerts.[42] There are 2 sources in which video metadata is derived: (1) operational gathered metadata, that is information about the content produced, such as the type of equipment, software, date, and location; (2) human-authored metadata, to improve search engine visibility, discoverability, audience engagement, and providing advertising opportunities to video publishers.[43] Today most professional video editing software has access to metadata. Avid’s MetaSync and Adobe’s Bridge are 2 prime examples of this.[44]

Geospatial metadata[edit]

Geospatial metadata relates to Geographic Information Systems (GIS) files, maps, images, and other data that is location-based. Metadata is used in GIS to document the characteristics and attributes of geographic data, such as database files and data that is developed within a GIS. It includes details like who developed the data, when it was collected, how it was processed, and what formats it’s available in, and then delivers the context for the data to be used effectively.[45]

Creation[edit]

Metadata can be created either by automated information processing or by manual work. Elementary metadata captured by computers can include information about when an object was created, who created it, when it was last updated, file size, and file extension. In this context an object refers to any of the following:

- A physical item such as a book, CD, DVD, a paper map, chair, table, flower pot, etc.

- An electronic file such as a digital image, digital photo, electronic document, program file, database table, etc.

A metadata engine collects, stores and analyzes information about data and metadata (data about data) in use within a domain.[46]

Data virtualization[edit]

Data virtualization emerged in the 2000s as the new software technology to complete the virtualization «stack» in the enterprise. Metadata is used in data virtualization servers which are enterprise infrastructure components, alongside database and application servers. Metadata in these servers is saved as persistent repository and describe business objects in various enterprise systems and applications. Structural metadata commonality is also important to support data virtualization.

Statistics and census services[edit]

Standardization and harmonization work has brought advantages to industry efforts to build metadata systems in the statistical community.[47][48] Several metadata guidelines and standards such as the European Statistics Code of Practice[49] and ISO 17369:2013 (Statistical Data and Metadata Exchange or SDMX)[47] provide key principles for how businesses, government bodies, and other entities should manage statistical data and metadata. Entities such as Eurostat,[50] European System of Central Banks,[50] and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency[51] have implemented these and other such standards and guidelines with the goal of improving «efficiency when managing statistical business processes».[50]

Library and information science[edit]

Metadata has been used in various ways as a means of cataloging items in libraries in both digital and analog formats. Such data helps classify, aggregate, identify, and locate a particular book, DVD, magazine, or any object a library might hold in its collection.[52] Until the 1980s, many library catalogs used 3×5 inch cards in file drawers to display a book’s title, author, subject matter, and an abbreviated alpha-numeric string (call number) which indicated the physical location of the book within the library’s shelves. The Dewey Decimal System employed by libraries for the classification of library materials by subject is an early example of metadata usage. The early paper catalog had information regarding whichever item was described on said card: title, author, subject, and a number as to where to find said item.[53] Beginning in the 1980s and 1990s, many libraries replaced these paper file cards with computer databases. These computer databases make it much easier and faster for users to do keyword searches. Another form of older metadata collection is the use by the US Census Bureau of what is known as the «Long Form». The Long Form asks questions that are used to create demographic data to find patterns of distribution.[54] Libraries employ metadata in library catalogues, most commonly as part of an Integrated Library Management System. Metadata is obtained by cataloging resources such as books, periodicals, DVDs, web pages or digital images. This data is stored in the integrated library management system, ILMS, using the MARC metadata standard. The purpose is to direct patrons to the physical or electronic location of items or areas they seek as well as to provide a description of the item/s in question.

More recent and specialized instances of library metadata include the establishment of digital libraries including e-print repositories and digital image libraries. While often based on library principles, the focus on non-librarian use, especially in providing metadata, means they do not follow traditional or common cataloging approaches. Given the custom nature of included materials, metadata fields are often specially created e.g. taxonomic classification fields, location fields, keywords, or copyright statement. Standard file information such as file size and format are usually automatically included.[55] Library operation has for decades been a key topic in efforts toward international standardization. Standards for metadata in digital libraries include Dublin Core, METS, MODS, DDI, DOI, URN, PREMIS schema, EML, and OAI-PMH. Leading libraries in the world give hints on their metadata standards strategies.[56][57] The use and creation of metadata in library and information science also include scientific publications:

In science[edit]

Metadata for scientific publications is often created by journal publishers and citation databases such as PubMed and Web of Science. The data contained within manuscripts or accompanying them as supplementary material is less often subject to metadata creation,[58][59] though they may be submitted to e.g. biomedical databases after publication. The original authors and database curators then become responsible for metadata creation, with the assistance of automated processes. Comprehensive metadata for all experimental data is the foundation of the FAIR Guiding Principles, or the standards for ensuring research data are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.[60]

Such metadata can then be utilized, complemented, and made accessible in useful ways. OpenAlex is a free online index of over 200 million scientific documents that integrates and provides metadata such as sources, citations, author information, scientific fields, and research topics. Its API and open source website can be used for metascience, scientometrics, and novel tools that query this semantic web of papers.[61][62][63] Another project under development, Scholia, uses the metadata of scientific publications for various visualizations and aggregation features such as providing a simple user interface summarizing literature about a specific feature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus using Wikidata’s «main subject» property.[64]

In research labor, transparent metadata about authors’ contributions to works have been proposed – e.g. the role played in the production of the paper, the level of contribution and the responsibilities.[65][66]

Moreover, various metadata about scientific outputs can be created or complemented – for instance, scite.ai attempts to track and link citations of papers as ‘Supporting’, ‘Mentioning’ or ‘Contrasting’ the study.[67] Other examples include developments of alternative metrics[68] – which, beyond providing help for assessment and findability, also aggregate many of the public discussions about a scientific paper on social media such as Reddit, citations on Wikipedia, and reports about the study in the news media[69] – and a call for showing whether or not the original findings are confirmed or could get reproduced.[70][71]

In museums[edit]

Metadata in a museum context is the information that trained cultural documentation specialists, such as archivists, librarians, museum registrars and curators, create to index, structure, describe, identify, or otherwise specify works of art, architecture, cultural objects and their images.[72][73][74] Descriptive metadata is most commonly used in museum contexts for object identification and resource recovery purposes.[73]

Usage[edit]

Metadata is developed and applied within collecting institutions and museums in order to:

- Facilitate resource discovery and execute search queries.[74]

- Create digital archives that store information relating to various aspects of museum collections and cultural objects, and serve archival and managerial purposes.[74]

- Provide public audiences access to cultural objects through publishing digital content online.[73][74]

Standards[edit]

Many museums and cultural heritage centers recognize that given the diversity of artworks and cultural objects, no single model or standard suffices to describe and catalog cultural works.[72][73][74] For example, a sculpted Indigenous artifact could be classified as an artwork, an archaeological artifact, or an Indigenous heritage item. The early stages of standardization in archiving, description and cataloging within the museum community began in the late 1990s with the development of standards such as Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA), Spectrum, CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM), Cataloging Cultural Objects (CCO) and the CDWA Lite XML schema.[73] These standards use HTML and XML markup languages for machine processing, publication and implementation.[73] The Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR), originally developed for characterizing books, have also been applied to cultural objects, works of art and architecture.[74] Standards, such as the CCO, are integrated within a Museum’s Collections Management System (CMS), a database through which museums are able to manage their collections, acquisitions, loans and conservation.[74] Scholars and professionals in the field note that the «quickly evolving landscape of standards and technologies» creates challenges for cultural documentarians, specifically non-technically trained professionals.[75][page needed] Most collecting institutions and museums use a relational database to categorize cultural works and their images.[74] Relational databases and metadata work to document and describe the complex relationships amongst cultural objects and multi-faceted works of art, as well as between objects and places, people, and artistic movements.[73][74] Relational database structures are also beneficial within collecting institutions and museums because they allow for archivists to make a clear distinction between cultural objects and their images; an unclear distinction could lead to confusing and inaccurate searches.[74]

Cultural objects and artworks[edit]

An object’s materiality, function, and purpose, as well as the size (e.g., measurements, such as height, width, weight), storage requirements (e.g., climate-controlled environment), and focus of the museum and collection, influence the descriptive depth of the data attributed to the object by cultural documentarians.[74] The established institutional cataloging practices, goals, and expertise of cultural documentarians and database structure also influence the information ascribed to cultural objects and the ways in which cultural objects are categorized.[72][74] Additionally, museums often employ standardized commercial collection management software that prescribes and limits the ways in which archivists can describe artworks and cultural objects.[75] As well, collecting institutions and museums use Controlled Vocabularies to describe cultural objects and artworks in their collections.[73][74] Getty Vocabularies and the Library of Congress Controlled Vocabularies are reputable within the museum community and are recommended by CCO standards.[74] Museums are encouraged to use controlled vocabularies that are contextual and relevant to their collections and enhance the functionality of their digital information systems.[73][74] Controlled Vocabularies are beneficial within databases because they provide a high level of consistency, improving resource retrieval.[73][74] Metadata structures, including controlled vocabularies, reflect the ontologies of the systems from which they were created. Often the processes through which cultural objects are described and categorized through metadata in museums do not reflect the perspectives of the maker communities.[72][76]

Museums and the Internet[edit]

Metadata has been instrumental in the creation of digital information systems and archives within museums and has made it easier for museums to publish digital content online. This has enabled audiences who might not have had access to cultural objects due to geographic or economic barriers to have access to them.[73] In the 2000s, as more museums have adopted archival standards and created intricate databases, discussions about Linked Data between museum databases have come up in the museum, archival, and library science communities.[75] Collection Management Systems (CMS) and Digital Asset Management tools can be local or shared systems.[74] Digital Humanities scholars note many benefits of interoperability between museum databases and collections, while also acknowledging the difficulties of achieving such interoperability.[75]

Law[edit]

United States[edit]

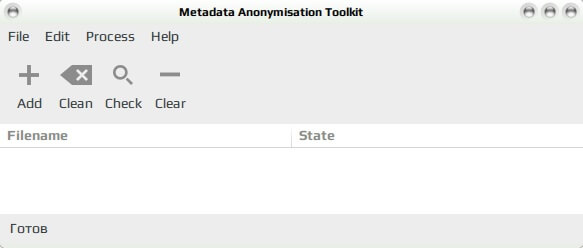

Problems involving metadata in litigation in the United States are becoming widespread.[when?] Courts have looked at various questions involving metadata, including the discoverability of metadata by parties. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure have specific rules for discovery of electronically stored information, and subsequent case law applying those rules has elucidated on the litigant’s duty to produce metadata when litigating in federal court.[77] In October 2009, the Arizona Supreme Court has ruled that metadata records are public record.[78] Document metadata have proven particularly important in legal environments in which litigation has requested metadata, that can include sensitive information detrimental to a certain party in court. Using metadata removal tools to «clean» or redact documents can mitigate the risks of unwittingly sending sensitive data. This process partially (see data remanence) protects law firms from potentially damaging leaking of sensitive data through electronic discovery.

Opinion polls have shown that 45% of Americans are «not at all confident» in the ability of social media sites to ensure their personal data is secure and 40% say that social media sites should not be able to store any information on individuals. 76% of Americans say that they are not confident that the information advertising agencies collect on them is secure and 50% say that online advertising agencies should not be allowed to record any of their information at all.[79]

Australia[edit]

In Australia, the need to strengthen national security has resulted in the introduction of a new metadata storage law.[80] This new law means that both security and policing agencies will be allowed to access up to 2 years of an individual’s metadata, with the aim of making it easier to stop any terrorist attacks and serious crimes from happening.

In legislation[edit]

Legislative metadata has been the subject of some discussion in law.gov forums such as workshops held by the Legal Information Institute at the Cornell Law School on 22 and 23 March 2010. The documentation for these forums is titled, «Suggested metadata practices for legislation and regulations».[81]

A handful of key points have been outlined by these discussions, section headings of which are listed as follows:

- General Considerations

- Document Structure

- Document Contents

- Metadata (elements of)

- Layering

- Point-in-time versus post-hoc

In healthcare[edit]

Australian medical research pioneered the definition of metadata for applications in health care. That approach offers the first recognized attempt to adhere to international standards in medical sciences instead of defining a proprietary standard under the World Health Organization (WHO) umbrella. The medical community yet did not approve of the need to follow metadata standards despite research that supported these standards.[82]

In biomedical research[edit]

Research studies in the fields of biomedicine and molecular biology frequently yield large quantities of data, including results of genome or meta-genome sequencing, proteomics data, and even notes or plans created during the course of research itself.[83] Each data type involves its own variety of metadata and the processes necessary to produce these metadata. General metadata standards, such as ISA-Tab,[84] allow researchers to create and exchange experimental metadata in consistent formats. Specific experimental approaches frequently have their own metadata standards and systems: metadata standards for mass spectrometry include mzML[85] and SPLASH,[86] while XML-based standards such as PDBML[87] and SRA XML[88] serve as standards for macromolecular structure and sequencing data, respectively.

The products of biomedical research are generally realized as peer-reviewed manuscripts and these publications are yet another source of data (see #In science).

Data warehousing[edit]

A data warehouse (DW) is a repository of an organization’s electronically stored data. Data warehouses are designed to manage and store the data. Data warehouses differ from business intelligence (BI) systems because BI systems are designed to use data to create reports and analyze the information, to provide strategic guidance to management.[89] Metadata is an important tool in how data is stored in data warehouses. The purpose of a data warehouse is to house standardized, structured, consistent, integrated, correct, «cleaned» and timely data, extracted from various operational systems in an organization. The extracted data are integrated in the data warehouse environment to provide an enterprise-wide perspective. Data are structured in a way to serve the reporting and analytic requirements. The design of structural metadata commonality using a data modeling method such as entity-relationship model diagramming is important in any data warehouse development effort. They detail metadata on each piece of data in the data warehouse. An essential component of a data warehouse/business intelligence system is the metadata and tools to manage and retrieve the metadata. Ralph Kimball[90] describes metadata as the DNA of the data warehouse as metadata defines the elements of the data warehouse and how they work together.

Kimball et al.[91] refers to 3 main categories of metadata: Technical metadata, business metadata and process metadata. Technical metadata is primarily definitional, while business metadata and process metadata is primarily descriptive. The categories sometimes overlap.

- Technical metadata defines the objects and processes in a DW/BI system, as seen from a technical point of view. The technical metadata includes the system metadata, which defines the data structures such as tables, fields, data types, indexes, and partitions in the relational engine, as well as databases, dimensions, measures, and data mining models. Technical metadata defines the data model and the way it is displayed for the users, with the reports, schedules, distribution lists, and user security rights.

- Business metadata is content from the data warehouse described in more user-friendly terms. The business metadata tells you what data you have, where they come from, what they mean and what their relationship is to other data in the data warehouse. Business metadata may also serve as documentation for the DW/BI system. Users who browse the data warehouse are primarily viewing the business metadata.

- Process metadata is used to describe the results of various operations in the data warehouse. Within the ETL process, all key data from tasks is logged on execution. This includes start time, end time, CPU seconds used, disk reads, disk writes, and rows processed. When troubleshooting the ETL or query process, this sort of data becomes valuable. Process metadata is the fact measurement when building and using a DW/BI system. Some organizations make a living out of collecting and selling this sort of data to companies – in that case, the process metadata becomes the business metadata for the fact and dimension tables. Collecting process metadata is in the interest of business people who can use the data to identify the users of their products, which products they are using, and what level of service they are receiving.

On the Internet[edit]

The HTML format used to define web pages allows for the inclusion of a variety of types of metadata, from basic descriptive text, dates and keywords to further advanced metadata schemes such as the Dublin Core, e-GMS, and AGLS[92] standards. Pages and files can also be geotagged with coordinates, categorized or tagged, including collaboratively such as with folksonomies.

When media has identifiers set or when such can be generated, information such as file tags and descriptions can be pulled or scraped from the Internet – for example about movies.[93] Various online databases are aggregated and provide metadata for various data. The collaboratively built Wikidata has identifiers not just for media but also abstract concepts, various objects, and other entities, that can be looked up by humans and machines to retrieve useful information and to link knowledge in other knowledge bases and databases.[64]

Metadata may be included in the page’s header or in a separate file. Microformats allow metadata to be added to on-page data in a way that regular web users do not see, but computers, web crawlers and search engines can readily access. Many search engines are cautious about using metadata in their ranking algorithms because of exploitation of metadata and the practice of search engine optimization, SEO, to improve rankings. See the Meta element article for further discussion. This cautious attitude may be justified as people, according to Doctorow,[94] are not executing care and diligence when creating their own metadata and that metadata is part of a competitive environment where the metadata is used to promote the metadata creators own purposes. Studies show that search engines respond to web pages with metadata implementations,[95] and Google has an announcement on its site showing the meta tags that its search engine understands.[96] Enterprise search startup Swiftype recognizes metadata as a relevance signal that webmasters can implement for their website-specific search engine, even releasing their own extension, known as Meta Tags 2.[97]

In the broadcast industry[edit]

In the broadcast industry, metadata is linked to audio and video broadcast media to:

- identify the media: clip or playlist names, duration, timecode, etc.

- describe the content: notes regarding the quality of video content, rating, description (for example, during a sport event, keywords like goal, red card will be associated to some clips)

- classify media: metadata allows producers to sort the media or to easily and quickly find a video content (a TV news could urgently need some archive content for a subject). For example, the BBC has a large subject classification system, Lonclass, a customized version of the more general-purpose Universal Decimal Classification.

This metadata can be linked to the video media thanks to the video servers. Most major broadcast sporting events like FIFA World Cup or the Olympic Games use this metadata to distribute their video content to TV stations through keywords. It is often the host broadcaster[98] who is in charge of organizing metadata through its International Broadcast Centre and its video servers. This metadata is recorded with the images and entered by metadata operators (loggers) who associate in live metadata available in metadata grids through software (such as Multicam(LSM) or IPDirector used during the FIFA World Cup or Olympic Games).[99][100]

Geospatial[edit]

Metadata that describes geographic objects in electronic storage or format (such as datasets, maps, features, or documents with a geospatial component) has a history dating back to at least 1994 (refer to the MIT Library page on FGDC Metadata). This class of metadata is described more fully on the geospatial metadata article.

Ecological and environmental[edit]

Ecological and environmental metadata is intended to document the «who, what, when, where, why, and how» of data collection for a particular study. This typically means which organization or institution collected the data, what type of data, which date(s) the data was collected, the rationale for the data collection, and the methodology used for the data collection. Metadata should be generated in a format commonly used by the most relevant science community, such as Darwin Core, Ecological Metadata Language,[101] or Dublin Core. Metadata editing tools exist to facilitate metadata generation (e.g. Metavist,[102] Mercury, Morpho[103]). Metadata should describe the provenance of the data (where they originated, as well as any transformations the data underwent) and how to give credit for (cite) the data products.

Digital music[edit]

See also: § On the Internet

When first released in 1982, Compact Discs only contained a Table Of Contents (TOC) with the number of tracks on the disc and their length in samples.[104][105] Fourteen years later in 1996, a revision of the CD Red Book standard added CD-Text to carry additional metadata.[106] But CD-Text was not widely adopted. Shortly thereafter, it became common for personal computers to retrieve metadata from external sources (e.g. CDDB, Gracenote) based on the TOC.

Digital audio formats such as digital audio files superseded music formats such as cassette tapes and CDs in the 2000s. Digital audio files could be labeled with more information than could be contained in just the file name. That descriptive information is called the audio tag or audio metadata in general. Computer programs specializing in adding or modifying this information are called tag editors. Metadata can be used to name, describe, catalog, and indicate ownership or copyright for a digital audio file, and its presence makes it much easier to locate a specific audio file within a group, typically through use of a search engine that accesses the metadata. As different digital audio formats were developed, attempts were made to standardize a specific location within the digital files where this information could be stored.

As a result, almost all digital audio formats, including mp3, broadcast wav, and AIFF files, have similar standardized locations that can be populated with metadata. The metadata for compressed and uncompressed digital music is often encoded in the ID3 tag. Common editors such as TagLib support MP3, Ogg Vorbis, FLAC, MPC, Speex, WavPack TrueAudio, WAV, AIFF, MP4, and ASF file formats.

Cloud applications[edit]

With the availability of cloud applications, which include those to add metadata to content, metadata is increasingly available over the Internet.

Administration and management[edit]

Storage[edit]

Metadata can be stored either internally,[107] in the same file or structure as the data (this is also called embedded metadata), or externally, in a separate file or field from the described data. A data repository typically stores the metadata detached from the data but can be designed to support embedded metadata approaches. Each option has advantages and disadvantages:

- Internal storage means metadata always travels as part of the data they describe; thus, metadata is always available with the data, and can be manipulated locally. This method creates redundancy (precluding normalization), and does not allow managing all of a system’s metadata in one place. It arguably increases consistency, since the metadata is readily changed whenever the data is changed.

- External storage allows collocating metadata for all the contents, for example in a database, for more efficient searching and management. Redundancy can be avoided by normalizing the metadata’s organization. In this approach, metadata can be united with the content when information is transferred, for example in Streaming media; or can be referenced (for example, as a web link) from the transferred content. On the downside, the division of the metadata from the data content, especially in standalone files that refer to their source metadata elsewhere, increases the opportunities for misalignments between the two, as changes to either may not be reflected in the other.

Metadata can be stored in either human-readable or binary form. Storing metadata in a human-readable format such as XML can be useful because users can understand and edit it without specialized tools.[108] However, text-based formats are rarely optimized for storage capacity, communication time, or processing speed. A binary metadata format enables efficiency in all these respects, but requires special software to convert the binary information into human-readable content.

Database management[edit]

Each relational database system has its own mechanisms for storing metadata. Examples of relational-database metadata include:

- Tables of all tables in a database, their names, sizes, and number of rows in each table.

- Tables of columns in each database, what tables they are used in, and the type of data stored in each column.

In database terminology, this set of metadata is referred to as the catalog. The SQL standard specifies a uniform means to access the catalog, called the information schema, but not all databases implement it, even if they implement other aspects of the SQL standard. For an example of database-specific metadata access methods, see Oracle metadata. Programmatic access to metadata is possible using APIs such as JDBC, or SchemaCrawler.[109]

In popular culture[edit]

One of the first satirical examinations of the concept of Metadata as we understand it today is American Science Fiction author Hal Draper’s short story, MS Fnd in a Lbry (1961).

Here, the knowledge of all Mankind is condensed into an object the size of a desk drawer, however, the magnitude of the metadata (e.g. catalog of catalogs of… , as well as indexes and histories) eventually leads to dire yet humorous consequences for the human race.

The story prefigures the modern consequences of allowing metadata to become more important than the real data it is concerned with, and the risks inherent in that eventuality as a cautionary tale.

See also[edit]

- Agris: International Information System for the Agricultural Sciences and Technology

- Bibliographic record

- Classification scheme

- Crosswalk (metadata)

- DataONE

- Data Dictionary (aka metadata repository)

- Dublin Core

- Folksonomy

- GEOMS – Generic Earth Observation Metadata Standard

- Geospatial metadata

- IPDirector

- ISO/IEC 11179

- Knowledge tag

- The medium is the message

- Mercury: Metadata Search System

- Meta element

- Metadata Access Point Interface

- Metadata discovery

- Metadata facility for Java

- Metadata from Wikiversity

- Metadata publishing

- Metadata registry

- Metamathematics

- METAFOR Common Metadata for Climate Modelling Digital Repositories

- Microcontent

- Microformat

- Multicam (LSM)

- Observations and Measurements

- Ontology (computer science)

- Official statistics

- Paratext

- Preservation Metadata

- SDMX

- Semantic Web

- SGML

- The Metadata Company

- Universal Data Element Framework

- Vocabulary OneSource

- XSD

References[edit]

- ^ «Merriam Webster». Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ «An Architecture for Information in Digital Libraries». Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Zeng, Marcia (2004). «Metadata Types and Functions». NISO. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ National Information Standards Organization (NISO) (2001). Understanding Metadata (PDF). NISO Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-880124-62-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ a b Directorate, OECD Statistics. «OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms — Reference metadata Definition». stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ a b Dippo, Cathryn; Sundgren, Bo. «The Role of Metadata in Statistics» (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ^ a b National Information Standards Organization; Rebecca Guenther; Jaqueline Radebaugh (2004). Understanding Metadata (PDF). Bethesda, MD: NISO Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-880124-62-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «Metadata = Surveillance». Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Holly, Yu; Scott, Breivold (28 February 2008). Electronic Resource Management in Libraries: Research and Practice: Research and Practice. IGI Global. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-59904-892-5.

- ^ Tedd, Lucy A.; Large, J. Andrew (4 April 2005). Digital Libraries: Principles and Practice in a Global Environment. Walter de Gruyter. p. 90. ISBN 978-3-598-44005-2.

- ^ Steiner, Tobias (23 November 2017). «Metadaten und OER: Geschichte einer Beziehung (Metadata and OER: [hi]story of a relationship)». Synergie. Fachmagazin für Digitalisierung in der Lehre (in German). 04: 54. doi:10.17613/m6p81g. ISSN 2509-3096.

- ^ «Best Practices for Structural Metadata». University of Illinois. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ «NSA Recorded the CONTENT of ‘EVERY SINGLE’ CALL in a Foreign Country … and Also In AMERICA?». 18 March 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ «A Guardian Guide to your Metadata». theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. 12 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ «ADEO Imaging: TIFF Metadata». Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Rouse, Margaret (July 2014). «Metadata». WhatIs. TechTarget. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015.

- ^ Hüner, K.; Otto, B.; Österle, H.: Collaborative management of business metadata, in: International Journal of Information Management, 2011

- ^ «Metadata Standards And Metadata Registries: An Overview» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Bagley, Philip (November 1968). «Extension of programming language concepts» (PDF). Philadelphia: University City Science Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2012.

- ^ «The notion of «metadata» introduced by Bagley». Solntseff, N+1; Yezerski, A (1974). «A survey of extensible programming languages». Annual Review in Automatic Programming. Vol. 7. Elsevier Science Ltd. pp. 267–307. doi:10.1016/0066-4138(74)90001-9.

- ^ a b

NISO (2004). Understanding Metadata (PDF). NISO Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-880124-62-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2010. - ^ Wolff, Josephine (20 November 2013). «Newly Released Documents Show How Government Inflated the Definition of Metadata». Slate Magazine.

- ^ Bretherton, F. P.; Singley, P.T. (1994). Metadata: A User’s View, Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB). pp. 1091–1094.

- ^ a b c d e Beyene, Wondwossen Mulualem (2017). «Metadata and universal access in digital library environments». Library Hi Tech. 35 (2): 210–221. doi:10.1108/LHT-06-2016-0074. hdl:10642/5994.

- ^ Cathro, Warwick (1997). «Metadata: an overview». Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ DCMI (5 October 2009). «Semantic Recommendations». Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ «ISO 25964-1:2011(en)». ISO.org. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- ^ «Types of Metadata». University of Melbourne. 15 August 2006. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ Kübler, Stefanie; Skala, Wolfdietrich; Voisard, Agnès. «THE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF A GEOLOGIC HYPERMAP PROTOTYPE» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2013.

- ^ «ISO/IEC 11179-1:2004 Information technology — Metadata registries (MDR) — Part 1: Framework». Iso.org. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ «ISO/IEC 11179-3:2013 Information technology-Metadata registries — Part 3: Registry metamodel and basic attributes». iso.org. 2014.

- ^ «DCMI Specifications». Dublincore.org. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ «Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1». Dublincore.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ J. Kunze, T. Baker (2007). «The Dublin Core Metadata Element Set». ietf.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ «ISO 15836:2009 — Information and documentation — The Dublin Core metadata element set». Iso.org. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ «NISO Standards — National Information Standards Organization». Niso.org. 22 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ «Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT) — Version 2». w3.org. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ «What’s the Next Big Thing on the Web? It May Be a Small, Simple Thing — Microformats». Knowledge@Wharton. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. 27 July 2005.

- ^ «What is metadata?». IONOS Digitalguide. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ «How To Copyright Your Photos With Metadata». Guru Camera. gurucamera.com. 21 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^ «VRA Core Support Pages». Visual Resource Association Foundation. Visual Resource Association Foundation. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Homeland Security (October 2012). «System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER)» (PDF).

- ^ Webcase, Weblog (2011). «Examining video file metadata». Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Oak Tree Press (2011). «Metadata for Video». Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ «Geospatial Metadata – Federal Geographic Data Committee». www.fgdc.gov. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Kendall, Aaron. «Metadata-Driven Design: Designing a Flexible Engine for API Data Retrieval». InfoQ. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ a b Gløersen, R. (30 April 2011). «Improving interoperability in Statistics — The impact of SDMX: Some Considerations» (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Laurila, S. (21 December 2012). «Metadata system meeting requirements of standardisation, quality and interaction and integrity with other metadata systems: Case Variable Editor Statistics Finland» (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ «European Statistics Code of Practice». European Commission. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Economic and Social Council, Statistical Commission (3 March 2015). «Report on the Statistical Data and Metadata Exchange sponsors» (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ «EPA Metadata Technical Specification». U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 15 August 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Zavalina, Oksana L.; Zavalin, Vyacheslav; Shakeri, Shadi; Kizhakkethil, Priya (2016). «Developing an Empirically-based Framework of Metadata Change and Exploring Relation between Metadata Change and Metadata Quality in MARC Library Metadata». Procedia Computer Science. 99: 50–63. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.100.

- ^ «What is metadata?». Pro-Tek Vaults. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ National Archives of Australia (2002). «AGLS Metadata Element Set — Part 2: Usage Guide — A non-technical guide to using AGLS metadata for describing resources». Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Solodovnik, Iryna (2011). «Metadata issues in Digital Libraries: key concepts and perspectives». JLIS.it. University of Florence. 2 (2). doi:10.4403/jlis.it-4663. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ Library of Congress Network Development and MARC Standards Office (8 September 2005). «Library of Congress Washington DC on metadata». Loc.gov. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ «Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Frankfurt on metadata». Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Evangelou, Evangelos; Trikalinos, Thomas A.; Ioannidis, John P.A. (2005). «Unavailability of online supplementary scientific information from articles published in major journals». The FASEB Journal. 19 (14): 1943–1944. doi:10.1096/fj.05-4784lsf. ISSN 0892-6638. PMID 16319137. S2CID 24245004.

- ^ AlQuraishi, Mohammed; Sorger, Peter K. (18 May 2016). «Reproducibility will only come with data liberation». Science Translational Medicine. 8 (339): 339ed7. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0968. ISSN 1946-6234. PMC 5084089. PMID 27194726.

- ^ Wilkinson, Mark D.; Dumontier, Michel; Aalbersberg, IJsbrand Jan; Appleton, Gabrielle; Axton, Myles; Baak, Arie; Blomberg, Niklas; Boiten, Jan-Willem; da Silva Santos, Luiz Bonino (15 March 2016). «The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship». Scientific Data. 3: 160018. Bibcode:2016NatSD…360018W. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 4792175. PMID 26978244.

- ^ Singh Chawla, Dalmeet (24 January 2022). «Massive open index of scholarly papers launches». Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00138-y. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «OpenAlex: The Promising Alternative to Microsoft Academic Graph». Singapore Management University (SMU). Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «OpenAlex Documentation». Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b Waagmeester, Andra; Willighagen, Egon L.; Su, Andrew I.; Kutmon, Martina; Gayo, Jose Emilio Labra; Fernández-Álvarez, Daniel; Groom, Quentin; Schaap, Peter J.; Verhagen, Lisa M.; Koehorst, Jasper J. (22 January 2021). «A protocol for adding knowledge to Wikidata: aligning resources on human coronaviruses». BMC Biology. 19 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-00940-y. ISSN 1741-7007. PMC 7820539. PMID 33482803.

- ^ McNutt, Marcia K.; Bradford, Monica; Drazen, Jeffrey M.; Hanson, Brooks; Howard, Bob; Jamieson, Kathleen Hall; Kiermer, Véronique; Marcus, Emilie; Pope, Barbara Kline; Schekman, Randy; Swaminathan, Sowmya; Stang, Peter J.; Verma, Inder M. (13 March 2018). «Transparency in authors’ contributions and responsibilities to promote integrity in scientific publication». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (11): 2557–2560. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.2557M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1715374115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5856527. PMID 29487213.

- ^ Brand, Amy; Allen, Liz; Altman, Micah; Hlava, Marjorie; Scott, Jo (1 April 2015). «Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit». Learned Publishing. 28 (2): 151–155. doi:10.1087/20150211. S2CID 45167271.

- ^ Khamsi, Roxanne (1 May 2020). «Coronavirus in context: Scite.ai tracks positive and negative citations for COVID-19 literature». Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01324-6. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Fortunato, Santo; Bergstrom, Carl T.; Börner, Katy; Evans, James A.; Helbing, Dirk; Milojević, Staša; Petersen, Alexander M.; Radicchi, Filippo; Sinatra, Roberta; Uzzi, Brian; Vespignani, Alessandro; Waltman, Ludo; Wang, Dashun; Barabási, Albert-László (2 March 2018). «Science of science». Science. 359 (6379): eaao0185. doi:10.1126/science.aao0185. PMC 5949209. PMID 29496846. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Baykoucheva, Svetla (2015). «Measuring attention». Managing Scientific Information and Research Data: 127–136. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100195-0.00014-7. ISBN 9780081001950.

- ^ «A new replication crisis: Research that is less likely to be true is cited more». phys.org. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Serra-Garcia, Marta; Gneezy, Uri (1 May 2021). «Nonreplicable publications are cited more than replicable ones». Science Advances. 7 (21): eabd1705. Bibcode:2021SciA….7D1705S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd1705. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 8139580. PMID 34020944.

- ^ a b c d Zange, Charles S. (31 January 2015). «Community makers, major museums, and the Keet S’aaxw: Learning about the role of museums in interpreting cultural objects». Museums and the Web. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Baca, Murtha (2006). Cataloging cultural objects: a guide to describing cultural works and their images. Visual Resources Association. Visual Resources Association. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Baca, Murtha (2008). Introduction to Metadata: Second Edition. Los Angeles: Getty Information Institute. Los Angeles: Getty Information Institute. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Hooland, Seth Van; Verborgh, Ruben (2014). Linked Data for Libraries, Archives and Museums: How to Clean, Link and Publish Your Metadata. London: Facet.

- ^ Srinivasan, Ramesh (December 2006). «Indigenous, ethnic and cultural articulations of new media». International Journal of Cultural Studies. 9 (4): 497–518. doi:10.1177/1367877906069899. S2CID 145278668.

- ^ Gelzer, Reed D. (February 2008). «Metadata, Law, and the Real World: Slowly, the Three Are Merging». Journal of AHIMA. American Health Information Management Association. 79 (2): 56–57, 64. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Walsh, Jim (30 October 2009). «Ariz. Supreme Court rules electronic data is public record». The Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ «Americans’ Attitudes About Privacy, Security and Surveillance | Pew Research Center». Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Senate passes controversial metadata laws

- ^ «Suggested metadata practices for legislation and regulations». Legal Information Institute. 27 March 2010.

- ^ M. Löbe, M. Knuth, R. Mücke TIM: A Semantic Web Application for the Specification of Metadata Items in Clinical Research Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, CEUR-WS.org, urn:nbn:de:0074-559-9

- ^ Myneni, Sahiti; Patel, Vimla L. (1 June 2010). «Organization of Biomedical Data for Collaborative Scientific Research: A Research Information Management System». International Journal of Information Management. 30 (3): 256–264. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.09.005. ISSN 0268-4012. PMC 2882303. PMID 20543892.

- ^ Sansone, Susanna-Assunta; Rocca-Serra, Philippe; Field, Dawn; Maguire, Eamonn; Taylor, Chris; Hofmann, Oliver; Fang, Hong; Neumann, Steffen; Tong, Weida (2012). «Toward interoperable bioscience data». Nature Genetics. 44 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1038/ng.1054. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 3428019. PMID 22281772.

- ^

- ^ Wohlgemuth, Gert; Mehta, Sajjan S; Mejia, Ramon F; Neumann, Steffen; Pedrosa, Diego; Pluskal, Tomáš; Schymanski, Emma L; Willighagen, Egon L; Wilson, Michael (2016). «SPLASH, a hashed identifier for mass spectra». Nature Biotechnology. 34 (11): 1099–1101. doi:10.1038/nbt.3689. ISSN 1087-0156. PMC 5515539. PMID 27824832.

- ^ Westbrook, J.; Ito, N.; Nakamura, H.; Henrick, K.; Berman, H. M. (27 October 2004). «PDBML: the representation of archival macromolecular structure data in XML». Bioinformatics. 21 (7): 988–992. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti082. ISSN 1367-4803. PMID 15509603.

- ^ Leinonen, R.; Sugawara, H.; Shumway, M. (9 November 2010). «The Sequence Read Archive». Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database): D19–D21. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1019. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 3013647. PMID 21062823.

- ^ Inmon, W.H. Tech Topic: What is a Data Warehouse? Prism Solutions. Volume 1. 1995.

- ^ Kimball, Ralph (2008). The Data Warehouse Lifecycle Toolkit (Second ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 10, 115–117, 131–132, 140, 154–155. ISBN 978-0-470-14977-5.

- ^ Kimball 2008, pp. 116–117

- ^ National Archives of Australia, AGLS Metadata Standard, accessed 7 January 2010, «AGLS Metadata Standard». Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ «Making Use of Affective Features from Media Content Metadata for Better Movie Recommendation Making».

- ^ Metacrap: Putting the torch to 7 straw-men of the meta-utopia «Metacrap: Putting the torch to 7 straw-men of the meta-utopia». Archived from the original on 8 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ The impact of webpage content characteristics on webpage visibility in search engine results «The impact of webpage content characteristics on webpage visibility in search engine results (Part I)» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ «Meta tags that Google understands». Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.