It is a good steelman. I would criticize it as follows though:

The meaning of any given word is context dependent, because meaning is a normative process. In other words, words are tools which rely on their common-understanding as leverage to be used.

This process of communal definition is never final, and so the common-understandings of words are continually working their way into their meanings. It happens all the time, dictionaries are updated, definitions shift, language evolves.

All very true, and poorly appreciated by most.

So, we shouldn’t discount the fact that the atmosphere of taboo around the n-word works its way into its definition.

Here you have pulled a sleight of hand. You have shifted from words having usages, defined by the context in which it is being used, to having a meaning decided by some global understanding of the word. In Australia «thongs» is used to mean sandals — it doesn’t matter if the majority of English speakers around the world use it to mean a g-string. The slightly sexualised word «thong» around the world might have a small taboo inserted into its defintion elsewhere, but it simply doesn’t in Australia, because its use is local to its immediate context.

I.e. you have subtly shifted from a pure descriptivist view to a prescriptivist one — albeit not using a dictionary or other central authority, but by assessing the «global» culture in which the word is used. If such a standard were used throughout linguistics there would be single «correct» meaning to a word defined by global consensus. This is not how we understand language/linguistics which understand word/grammar usages in the context in which they are used — not the majority context somewhere else.

You go on

Because society judges those who use it to be ‘racist’, that informs its use and therefore, crucially, its meaning*. Thus, it can be sensibly said that using the n-word means something different to «the n-word», even when said dispassionately.

and

To clarify, I’m not arguing that it’s «immoral» to say the n-word. I’m just explaining why it isn’t illogical to judge someone negatively for saying it.

So the problem of course is that the rest of what you argue could be true — and very reasonably so — if we understand the usage to match such a global context. In many cases (maybe most?) it is totally correct to interpret someone using the n-word to mean something about lack of sympathy for black people.

But it doesn’t universally imply that it does. More precisely, this statement:

I’m just explaining why it isn’t illogical to judge someone negatively for saying it.

is kind of moving the goal-posts. Of course it is possible to logically judge someone negatively for saying it. The problem is judging someone negatively for saying it in all contexts. That’s the issue in play. We already know that in some contexts it is appropriate to interpret it as direct racism so the above is kind of a truism. The question is why, say in a court room or other official capacity, does even quoting the word get elided for fear of offence?

Whilst you are right to point out that there is some large scale global context to its use, it doesn’t change the basic necessity with language to assess the context in which it was used too. And whilst taboos can get incorporated into usages of words it is still possible, even rational, to be able to determine how much of a word’s usage is based on that taboo, and what that really reveals.

If one were to go further and say that use of the word is direct evidence of antipathy towards black people without assessing the context of its use, and only the purported global one, then that indeed can be wholly irrational. For instance, take an author using that word. It’s use here can be leveraging that very taboo to make a racist character more believable and to leverage the shock value of the taboo for more effective fiction. Calling such an author necessarily racist is illogical.

This submission is currently being researched & evaluated!

You can help confirm this entry by contributing facts, media, and other evidence of notability and mutation.

About

There Are Consequences To Saying The N-word is a viral lip-dub of Kratos from God of War telling the boy character Atreus that «there are consequences to saying the n-word,» to which Atreus replies, «Why? How do you know? How do you know?» After the video was uploaded to TikTok in late 2022, it received viral usage as a sound in other memes and skits.

Origin

In Part 20 of the video game God of War 4, the characters Kratos and Atreus are in a cave when Atreus kills a man without Kratos’ permission. After going back and forth about the ethics of non-survival killing, Kratos shakes Atreus and says, «There are consequences to killing a God,» to which Atreus says, «Why? How do you know? How do you know?» (YouTube upload shown below).

On December 6th, 2022, TikToker[1] _breaking_bad_1 posted a video that lip-dubbed over the Kratos and Atreus scene, instead making Kratos say, «There are consequences to saying the n-word.» Over the course of one week, the video received roughly 10.6 million plays and 1.7 million likes (shown below).

@_breaking_bad_1 ♬ original sound – Breaking Bad

Spread

Going into mid-December 2022, multiple TikTokers used _breaking_bad_1’s sound[2] for their own videos. For instance, one of the first was TikToker[3] saulbestman on December 6th, 2022, who made a misheard song lyric speech bubble using the audio, earning roughly 422,700 plays and 36,000 likes in one week (shown below, left). On December 8th, 2022, TikToker[4] icyboi.mp4 used the sound to make a joke about PewDiePie and his n-word controversy. The video received roughly 5.3 million plays and 978,900 likes in five days (shown below, right).

@saulbestman #godofwar #kratos #consequences #atreus #fy @Robin ♬ original sound – Breaking Bad

@icyboi.mp4 I recall a certain bridge

♬ original sound – Breaking Bad

On December 11th, 2022, YouTuber[5] RenzGaming27 posted a video that used the Kratos audio, gaining roughly 46,100 views in two days (shown below). Others like Instagram[6] user large.trap made similar videos around the same time.

Various Examples

https://www.tiktok.com/embed/7175163824109096193

https://www.tiktok.com/embed/7176367710488497454

https://www.tiktok.com/embed/7176010640832662826

https://www.tiktok.com/embed/7174232597067779333

Search Interest

Unavailable.

External References

Recent Images

There are no images currently available.

CNN

—

The podcaster Joe Rogan did not join a mob that forced lawmakers to flee for their lives. He never carried a Confederate flag inside the US Capitol rotunda. No one died trying to stop him from using the n-word.

But what Rogan and those that defend him have done since video clips of him using the n-word surfaced on social media is arguably just as dangerous as what a mob did when they stormed the US Capitol on January 6 last year.

Rogan breached a civic norm that has held America together since World War II. It’s an unspoken agreement that we would never return to the kind of country we used to be.

That agreement revolved around this simple rule:

A White person would never be able to publicly use the n-word again and not pay a price.

Rogan has so far paid no steep professional price for using a racial slur that’s been called the “nuclear bomb of racial epithets.” It may even boost his career. That’s what some say happened to another White entertainer who was recently caught using the word.

It is a sign of how desensitized we have become to the rising levels of violence – rhetorical and physical – in our country that Rogan’s slurs were largely treated as the latest racial outrage of the week.

But once we allow a White public figure to repeatedly use the foulest racial epithet in the English language without experiencing any form of punishment, we become a different country.

We accept the mainstreaming of a form of political violence that’s as dangerous as the January 6 attack.

Some might say that comparing a podcaster’s moronic musings about race to January 6 is hyperbole. They will invoke “cancel culture” and political correctness.

The man apologized, they will say. And he did.

He called his comments “the most regretful and shameful thing,” adding “I know that to most people, there’s no context where a White person is ever allowed to say that word, never mind publicly on a podcast, and I agree with that,” Rogan said after a video showed him using the n-word more than 20 times in different podcast episodes.

Rogan has also apologized for a video of him comparing a gathering of Black people to “Planet of the Apes.” He has said he is “not racist.”

In the past, White public figures who used the n-word provoked universal and unqualified condemnation. But Rogan has gotten some support.

His comments drew criticism from Daniel Ek, chief executive of Spotify, which reportedly pays Rogan at least $100 million to carry his mega-popular podcast. Ek said Rogan’s racial slurs “do not represent the values of this company.”

But Ek also said Spotify will continue to stand by Rogan, who had the most popular podcast on the streaming platform last year.

“We should have clear lines around content and take action when they are crossed, but canceling voices is a slippery slope,” Ek said in a memo to his staff.

Another media mogul offered Rogan a lucrative new gig. The chief executive of another social media company offered Rogan $100 million to bring his podcast to its platform, citing Rogan’s “legion of fans in desire for real conversation.”

And former President Donald Trump told Rogan he should “stop apologizing” for his controversies – including the racial slurs and spreading Covid-19 misinformation – because he shouldn’t allow critics to make him “look weak and frightened.”

Rogan’s use of the n-word could even boost his career if it follows the trajectory of another White entertainer, country music star Morgan Wallen.

Wallen’s career seemed finished a year ago after he was caught on video using the n-word in a conversation with a friend. Radio stations and streaming services dropped him from their playlists. The Academy of Country Music declared him ineligible for the 2021 ACM Awards. Wallen apologized but was widely condemned.

A year later, “Wallen’s career has not only rebounded but exploded,” according to Billboard magazine. His songs are back on the radio and he had the most popular album of 2021 in the US, according to Billboard. Wallen is embarking on a nationwide tour, with many dates already sold out, and is slated to headline music festivals this summer.

Rolling Stone published an article earlier this month with the headline: “Did Dropping the N-Word Actually Help Morgan Wallen’s Career?” The article quoted a Nashville industry insider who said Wallen’s popularity surged after his use of the n-word because the backlash “made him a martyr… to people that hold what I would say are prejudices.”

A recent USA Today story said Wallen has become an “anti-cancel culture hero” and quoted an executive who said that the more the mainstream criticizes Wallen “the more power those who support his bigotry begin to feel.”

Meanwhile, Rogan is now reframing the backlash over his use of the n-word as a cancel culture battle.

“This is a “political hit job,” he recently said, suggesting that the controversy may actually help him.

“It’s good because it makes me address some (expletive) that I really wish wasn’t out there,” he told a guest on his show Tuesday. ”You just have to stay offline … Life goes on as normal.”

For decades, life would never go on as normal for a White person caught using the n-word. This represents a momentous shift in American culture. There used to be a consensus that any White person caught using the n-word or other racial slurs would pay a hefty price.

Not that long ago, many did.

In 2018, the actress Roseanne Barr had her popular sitcom canceled after she made a series of racist tweets.

That same year, a top executive resigned from Netflix after using the N-word in front of Black employees.

Celebrity chef Paula Deen lost her business empire and saw her cooking shows canceled by the Food Network in 2013 after she admitted using the n-word during a deposition in a lawsuit.

And the career of “Seinfeld’s” Michael Richards cratered after he was caught calling hecklers the n-word in 2006.

The price that White people paid for crossing this line wasn’t legal. No one called for them to be jailed or fined. But many were shamed and exiled from their professional communities.

The prohibition against White people using racist language in public was so severe that a person could see their career destroyed even if they used a racial slur that most people didn’t comprehend.

George Allen was a popular US senator who seemed to be cruising to re-election in Virginia in 2006 when he was filmed using the word “macaca,” a type of monkey,” to describe an Indian-American volunteer with the campaign of his opponent.

He lost his re-election bid after both Republicans and Democrats criticized him. His political career never recovered.

Using the n-word became a rhetorical red line because it represents arguably the most shameful part of US history: slavery and the Jim Crow era.

Neal Lester, an Arizona State University English professor who has taught a course on the n-word, noted it has been described as “the most toxic in the English language,” a term “almost magical in its negative power,” and a slur that “occupies a place in the soul where logic and reason never go.”

“The word is inextricably linked with violence and brutality on Black psyches and derogatory aspersions cast on Black bodies,” he said in an interview. “No degree of appropriating can rid it of that blood-soaked history.”

It took a lot of work to ban the n-word from the public square. That shift wasn’t about political correctness. It was about our survival as a multiracial democracy and our standing in the world.

The n-word became forbidden in the US public sphere around the mid-20th century when a consensus emerged that “public racism” was sabotaging democracy, some academics say. But in the decades before that, White entertainers and politicians talked like Rogan all the time.

World War II helped change that. The war against Nazism and revelations about the Holocaust raised awareness of racism, while America’s new role as a leader of the “free world” caused White elites to see racism as the nation’s Achilles heel, wrote Robert L. Fleegler, a history professor at the University of Mississippi, in a paper titled, “Theodore G. Bilbo and the Decline of Public Racism, 1938-1947.”

Bilbo, a US Senator from Mississippi, felt free enough to tell White supporters during an election campaign in 1946 that “I call on every red-blooded White man to use any means to keep the n***ers away from the polls.”

Bilbo won the Democratic primary and faced no opposition in the general election, but his Senate colleagues barred him from taking his seat in the chamber because of his open racism.

In the years that followed, Southern White politicians still used racially coded words like “state’s rights,” but most avoided using the n-word in public, Fleegler wrote.

The civil rights movement also created a stigma around Whites using the n-word and other racial slurs. The assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the eruption of race riots after King’s death showed White Americans what could happen when a group of citizens were treated with systemic disregard for their humanity.

Using the n-word came to be seen as a vulgar relic of a shameful past, said Jacob Levy, a scholar and author of an essay titled “The Weight of the Words.”

“The norm against publicly legitimizing Klan-type racism was built up over a long time,” Levy wrote, “calling on white Americans to do better than they were, partly by convincing them that they were better.”

Why the change now?

The theories vary. Some cite the rise of social media, the growth of White supremacist groups and a right-wing media ecosystem that has mainstreamed racist rhetoric.

Former President Trump played a part, too. He rode a trail of racist, sexist, and antisemitic statements all the way to the White House.

All these factors converged to create a chain effect that led to what one scholar calls “defining deviance down.” That’s what happens when a country starts accepting offensive language it rejected before, wrote Steven Levitsky, co-author of the book, “How Democracies Die.”

“When unwritten rules are violated over and over, we become overwhelmed – and then desensitized,” Levitsky wrote. “We grow accustomed to what we previously thought to be scandalous.”

Something else happens that’s even more deadly. When people in positions of power use dehumanizing language to describe other groups, atrocities often follow.

This is not ancient history: Consider what happened less than 30 years ago in Rwanda when some 800,000 civilians were slaughtered in a three-month period in 1994. Hutu extremists targeted both the Tutsi minority, who were a majority of those killed, as well as moderate Hutus.

What triggered the violence in part were the messages that came from people in positions of power in Rwanda. Many, like Rogan, had a public megaphone and an audience.

In a New Yorker essay on “How Norms Change,” the author Maria Konnikova described how Hutu leaders took to the radio calling Tutsis “cockroaches,” sanctioning the violence that followed. She said that “norms can shift at the speed of social life” when the wrong leaders command the public’s attention.

“To a great extent, the norms in Rwanda shifted so rapidly because they did so from the top: Influential radio stations broadcast a powerful, persuasive and constantly repeating message urging listeners to join killing squads and organize roadblocks,” Konnikova wrote.

Genocide is a worst-case scenario. But we don’t have to look as far as Rwanda to see how quickly civic norms can change when people in power start lowering standards. Earlier this month the Republican National Committee drafted a resolution calling the deadly January 6 insurrection “legitimate political discourse.”

CNN’s Stephen Collinson responded in a column, “The Republican Party is ever closer to the destination to which it has long been headed under former President Donald Trump – the legitimization of violence as a form of political expression.”

Rogan’s use of the n-word may also be drawing us closer to something else: destroying any plausible shot at building a genuine multiracial democracy.

The January 6 insurrection was so dangerous because it violated a political norm. The citizens in a healthy democracy are supposed to accept the peaceful transfer of power, not to use violence as a tool of political protest. That’s what most Americans agreed to leave behind after we fought a bloody Civil War over a political and moral issue: slavery.

The universal condemnation that used to greet White people who publicly used the n-word was also part of a civic norm that made a multiracial democracy possible. That word was a vestige of a hateful Jim Crow era that most Americans agreed to leave in the past. It was considered un-American.

This is the America that former President Ronald Reagan evoked in his famous “shining city on a hill” 1989 farewell address. He described us as a nation “teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace,” with doors “open to anyone with the will and heart to get here.”

What are we now?

What are we when a White entertainer with a huge public following can use the n-word repeatedly – and get a $100 million offer to bring “real conversation” to another platform?

What are we when Rogan’s employer can say that his company has “clear lines around content and take action when they are crossed,” but that line doesn’t include using a word that was used during the enslavement, rape and torture of millions of people.

Rogan once called himself a “f—ing moron… a cage-fighting commentator” and not a “respected source of information, even for me.” He is something more now. He is unleashing lethal forces that he may not understand.

He is also a blinking red light, warning that the civic and political rules that once held the nation together no longer apply.

We are poised to enter an era where a White person can use the n-word publicly and not only survive but thrive if they portray themselves as a victim of cancel culture. It’s a world where hate speech and violence are rebranded as “legitimate political discourse,” and “public racism” returns to ordinary life.

Don’t let the Rogan n-word controversy devolve into another tired discussion about cancel culture. This moment is bigger. If Rogan goes on with business as usual, all of us – not just Black people – will pay a price. Our country won’t be the same.

This is another January 6 moment.

No one who is not Black and uses the n-word should be surprised to receive blowback, let alone expect a free pass. It’s one of the most offensive and painful words in the English language. Sometimes, a pass could be granted depending on the context. Ultimately, I just wish folks, especially White folks, would have the good sense not to say it under any circumstances.

I’m wading into this thicket because of a controversy at Rutgers University Law School in New Jersey. Last October, a criminal law student said the n-word while quoting a 1993 legal opinion during virtual office hours. The class’s professor, Vera Bergelson, told the New York Times this week that she didn’t hear the word said at the time and wishes she had.

I have great sympathy for that Rutgers student, a middle-aged White woman embarking on a second career in law. According to the Times story, she had the good sense to forewarn her classmates by saying, “He said, um — and I’ll use a racial word, but it’s a quote.” In that context, I can’t fault her for wanting to quote from the legal opinion exactly. But if she knew enough to warn of the forthcoming word’s “racial” nature, she should have known better than to utter the six-letter abomination in the first place.

A petition circulated on the Newark campus called for a policy on racial slurs and for the professor and the offending student to issue formal apologies. Both did so during a meeting with the criminal law class and first-year students. Now, there’s talk of a voluntary ban on racial epithets being spoken in class.

Follow Jonathan Capehart’s opinions

I have a better idea: How about people educate themselves on the ugly history of the n-word and then avoid articulating it? I mean, that’s why we have the clunky “n-word” euphemism in the first place.

Columbia University professor John McWhorter did a fine job recently tracing the etymology of the n-word and how the slur became “unsayable.” What was missing in McWhorter’s analysis was a thorough discussion of how that word was used to dehumanize Black people and keep them in their place, how the n-word was likely among the last words heard by Black people before they were lynched.

A 2017 report from the Equal Justice Initiative, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” documents more than 4,000 extrajudicial killings (read, murders) across the country between 1877 and 1950. One was the 1906 lynching of Edward Johnson in Chattanooga, Tenn., in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted him a stay of execution for allegedly raping a White woman.

Johnson was dragged from jail by a White mob to the Walnut Street Bridge, where he was hanged, and his body shot hundreds of times. The EJI report notes, “The mob left a note pinned on the corpse that read: ‘To Justice Harlan. Come get your [n-word] now.’” Johnson’s last words reportedly were, “God bless you all. I am innocent.” He was cleared of rape in 2000.

For African Americans, the n-word is not a Rorschach test. It’s a stress test, the intensity of which rises and falls depending on one’s mood and sense of charity in the moment it tumbles from non-Black lips.

To the White parents of children enamored with rap music, where the n-word is omnipresent, I implore you to teach them the horrific history that shrouds the word. Teach them that saying it can cause others great pain and pray they act accordingly. As for me, I am constitutionally incapable of saying the n-word. I will not participate in my own degradation or that of Black people by repeating it.

There is no avoiding the n-word. It’s everywhere, from American literature to legal opinions that get read aloud in a university law class. If you end up saying the n-word in full, I might be willing to give you a pass. But it would be better to pass on saying it at all.

Read more from Jonathan:

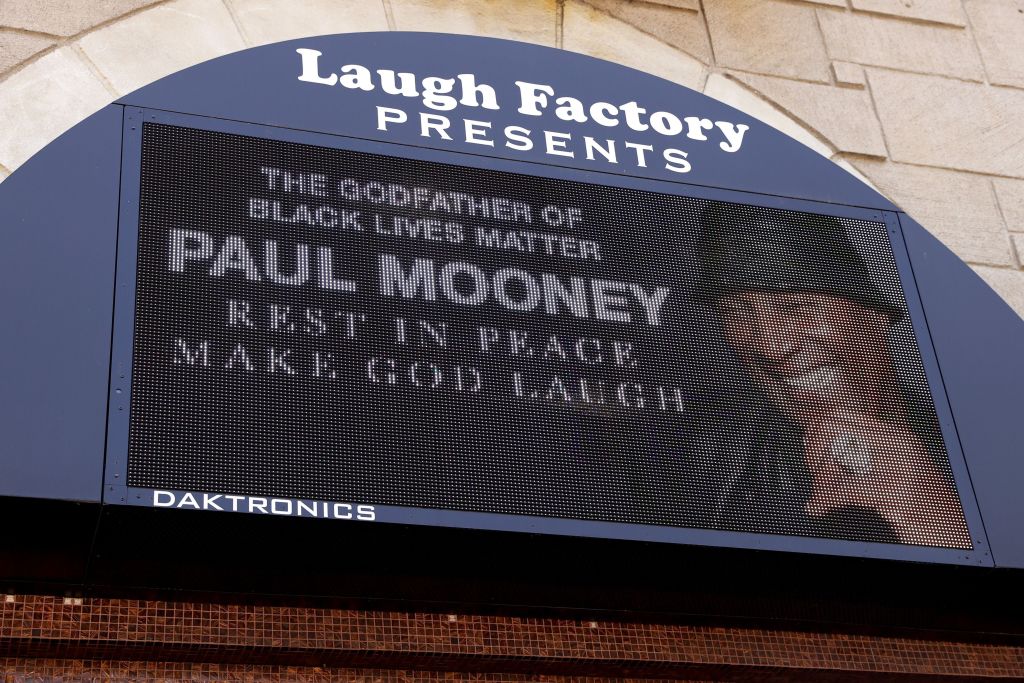

The Paul Mooney Tribute Show, Hollywood, May 27.

Photographer: Rich Fury/Getty Images North AmericaMay 29, 2021, 12:00 PM UTC

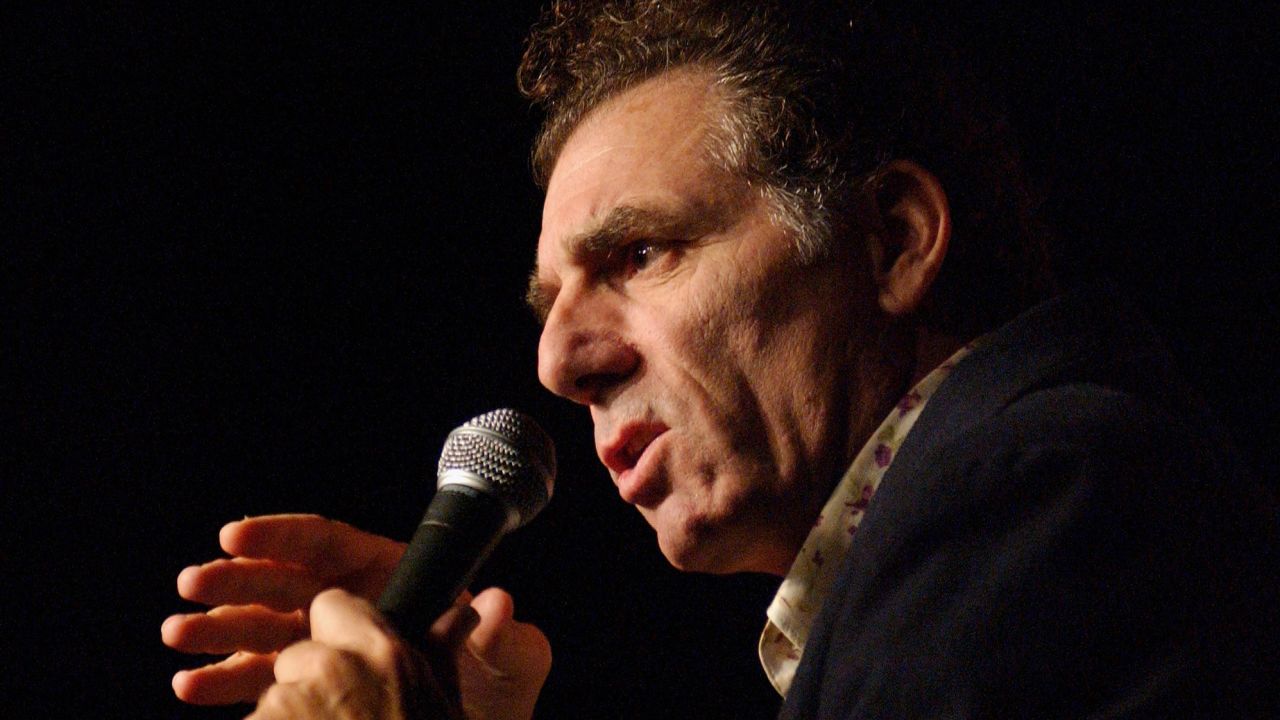

The comedian Paul Mooney, who died earlier this month at the age of 79, was a trenchant, provocative observer of race. He wrote the notorious “Word Association” sketch, prominently featuring the n-word, for Richard Pryor’s famous 1975 guest-hosting gig on “Saturday Night Live.”

In his own standup, Mooney used the word as a master surgeon would wield a scalpel: “I say [n-word] 100 times every morning,” went one joke. “Makes my teeth white.” In Mooney’s hands, this taboo word forced an uncomfortable reckoning for audience members of all races — including Black ones like me — every time it came out of his mouth.

The n-word is unique in the English language. On one hand, it is the ultimate insult—a word that has tormented generations of African Americans. Yet over time, it has become a popular term of endearment by the descendants of the very people who once had to endure it. Among many young people today—Black and white—the n-word can mean friend.

Neal A. Lester, dean of humanities and former chair of the English department at Arizona State University, recognized that the complexity of the n-word’s evolution demanded greater critical attention. In 2008, he taught the first ever college-level class designed to explore the n-word. Lester said the subject fascinated him precisely because he didn’t understand its layered complexities.

“When I first started talking about the idea of the course,” Lester recalled, “I had people saying, ‘This is really exciting, but what would you do in the course? How can you have a course about a word?’ It was clear to me that the course, both in its conception and in how it unfolded, was much bigger than a word. It starts with a word, but it becomes about other ideas and realities that go beyond words.”

Lester took a few minutes to talk to Teaching Tolerance Managing Editor Sean Price about what he’s learned and how that can help other educators.

How did the n-word become such a scathing insult?

We know, at least in the history I’ve looked at, that the word started off as just a descriptor, “negro,” with no value attached to it. … We know that as early as the 17th century, “negro” evolved to “nigger” as intentionally derogatory, and it has never been able to shed that baggage since then—even when Black people talk about appropriating and reappropriating it. The poison is still there. The word is inextricably linked with violence and brutality on Black psyches and derogatory aspersions cast on Black bodies. No degree of appropriating can rid it of that bloodsoaked history.

Why is the n-word so popular with many young Black kids today?

If you could keep the word within the context of the intimate environment [among friends], then I can see that you could potentially own the word and control it. But you can’t because the word takes on a life of its own if it’s not in that environment. People like to talk about it in terms of public and private uses. Jesse Jackson was one of those who called for a moratorium on using the word, but then was caught using the word with a live mic during a “private” whispered conversation.

There’s no way to know all of its nuances because it’s such a complicated word, a word with a particular racialized American history. But one way of getting at it is to have some critical and historical discussions about it and not pretend that it doesn’t exist. We also cannot pretend that there is not a double standard—that Blacks can say it without much social consequence but whites cannot. There’s a double standard about a lot of stuff. There are certain things that I would never say. In my relationship with my wife, who is not African American, I would never imagine her using that word, no matter how angry she was with me. …

That’s what I’m asking people to do—to self-reflect critically on how we all use language and the extent to which language is a reflection of our innermost thoughts. Most people don’t bother to go to that level of self-reflection and self-critique. Ultimately, that’s what the class is about. It’s about self-education and self-critique, not trying to control others by telling them what to say or how to think, but rather trying to figure out how we think and how the words we use mirror our thinking.

The class sessions often become confessionals because white students often admit details about their intimate social circles I would never be privy to otherwise.

What types of things do they confess?

In their circles of white friends, some are so comfortable with the n-word because they’ve grown up on and been nourished by hip-hop. Much of the commercial hip-hop culture by Black males uses the n-word as a staple. White youths, statistically the largest consumers of hip-hop, then feel that they can use the word among themselves with Black and white peers. … But then I hear in that same discussion that many of the Black youths are indeed offended by [whites using the n-word]. And if Blacks and whites are together and a white person uses the word, many Blacks are ready to fight. So this word comes laden with these complicated and contradictory emotional responses to it. It’s very confusing to folks on the “outside,” particularly when nobody has really talked about the history of the word in terms of American history, language, performance and identity.

Most public school teachers are white women. How might they hold class discussions about this word? Do you think it would help them to lay some groundwork?

You might want to get somebody from the outside who is African American to be a central part of any discussion—an administrator, a parent, a pastor or other professional with some credibility and authority. Every white teacher out there needs to know some Black people. Black people can rarely say they know no white people; it’s a near social impossibility. The NAACP would be a good place to start, but I do not suggest running to the NAACP as a single “authority.” Surely there are Black parents of school children or Black neighbors a few streets over or Black people at neighboring churches. The teacher might begin by admitting, “This is what I want to do, how would you approach this? Or, how do we approach it as a team? How can we build a team of collaboration so that we all accept the responsibility of educating ourselves and our youths about the power of words to heal or to harm?” This effort then becomes something shared as opposed to something that one person allegedly owns.

X

Add to an Existing Learning Plan

x

Apply for Learning for Justice’s Inaugural Professional Learning Institutes!

Join us this summer in Mississippi and Alabama for low-cost, weeklong, place-based, immersive learning experiences that support educators’ capacities to implement social justice education. Applications are open now until April 16.

Learn More!