From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The modern Persian name of Iran (ایران) means «the land of Aryans».[1] It derives immediately from the 3rd-century Sasanian Middle Persian ērān (Pahlavi spelling: 𐭠𐭩𐭫𐭠𐭭, ʼyrʼn), where it initially meant «of the Iranians»,[2] but soon also acquired a geographical connotation in the sense of «(lands inhabited by) Iranians».[2] In both geographic and demonymic senses, ērān is distinguished from its antonymic anērān, meaning «non-Iran(ian)».[2][3]

In the geographic sense, ērān was also distinguished from ērānšahr, the Sasanians’ own name for their empire, and which also included territories that were not primarily inhabited by ethnic Iranians.[2]

Fa:نامهای ایران

In pre-Islamic usage[edit]

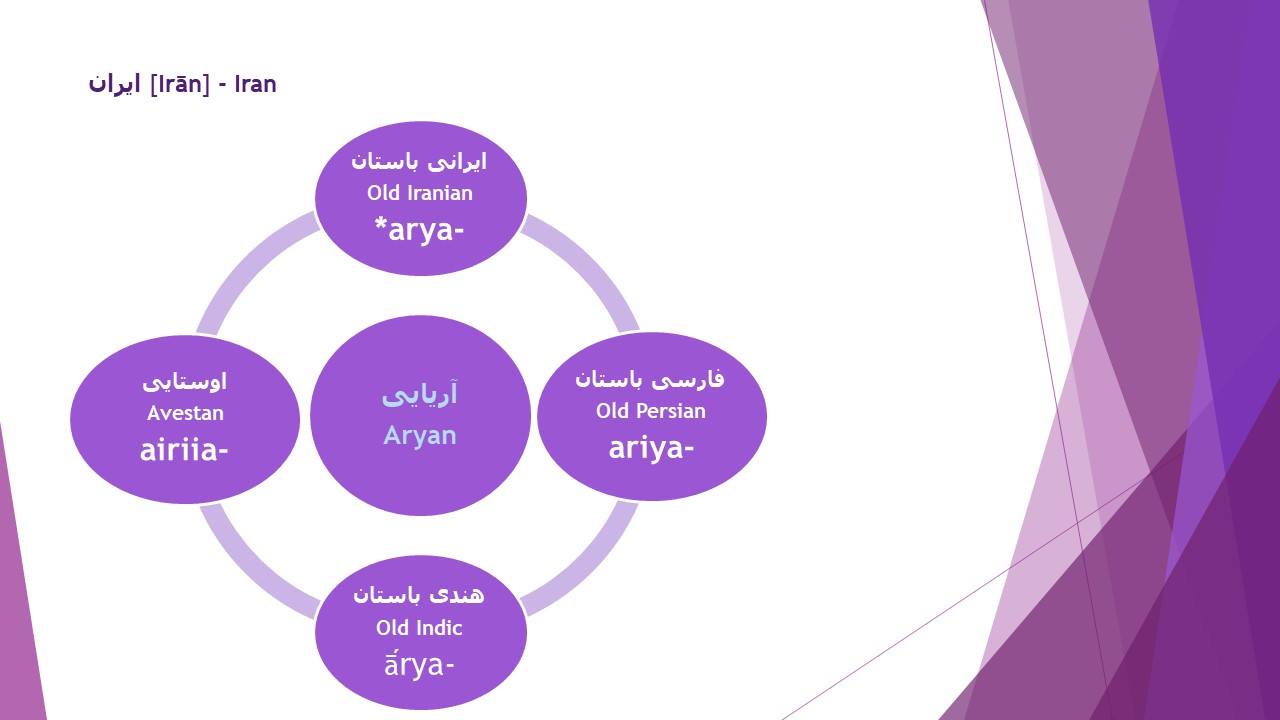

The word ērān is first attested in the inscriptions that accompany the investiture relief of Ardashir I (r. 224–242) at Naqsh-e Rustam.[2] In this bilingual inscription, the king calls himself «Ardashir, king of kings of the Iranians» (Middle Persian: ardašīr šāhān šāh ī ērān; Parthian: ardašīr šāhān šāh ī aryān).[2] The Middle Iranian ērān/aryān are oblique plural forms of gentilic ēr- (Middle Persian) and ary- (Parthian), which in turn both derive from Old Iranian *arya-, meaning «‘Aryan,’ i.e., ‘of the Iranians.'»[2][4] This Old Iranian *arya- is attested as an ethnic designator in Achaemenid inscriptions as Old Persian ariya-, and in Zoroastrianism’s Avesta tradition as Avestan airiia-/airya, etc.[5][n 1] It is «very likely»[2] that Ardashir I’s use of Middle Iranian ērān/aryān still retained the same meaning as did in Old Iranian, i.e. denoting the people rather than the empire.[2]

The expression «king of kings of the Iranians» found in Ardashir’s inscription remained a stock epithet of all the Sasanian kings. Similarly, the inscription «the Mazda-worshipping (mazdēsn) lord Ardashir, king of kings of the Iranians» that appears on Ardashir’s coins was likewise adopted by Ardashir’s successors. Ardashir’s son and immediate successor, Shapur I (r. 240/42–270/72) extended the title to «King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians» (Middle Persian: MLKAn MLKA ‘yr’n W ‘nyr’n šāhān šāh ī ērān ud anērān; Ancient Greek: βασιλεύς βασιλέων Αριανών basileús basiléōn Arianṓn), thus extending his intent to rule non-Iranians as well,[2] or because large areas of the empire was inhabited by non-Iranians.[7] In his trilingual inscription at the Ka’ba-ye Zartosht, Shapur I also introduces the term *ērānšahr.[n 2] Shapur’s inscription includes a list of provinces in his empire, and these include regions in the Caucasus that were not inhabited predominantly by Iranians.[2] An antonymic anērānšahr is attested from thirty years later in the inscriptions of Kartir, a high priest under several Sasanian kings. Kartir’s inscription also includes a lists of provinces, but unlike Shapur’s considers the provinces in the Caucasus anērānšahr.[2] These two uses may be contrasted with ērānšahr as understood by the late Sasanian Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr, which is a description of various provincial capitals of the ērānšahr, and includes Africa and Arabia as well.[8][9]

Notwithstanding this inscriptional use of ērān to refer to the Iranian peoples, the use of ērān to refer to the empire (and the antonymic anērān to refer to the Roman territories) is also attested by the early Sasanian period. Both ērān and anērān appear in 3rd century calendrical text written by Mani. The same short form reappears in the names of the towns founded by Sasanian dynasts, for instance in Ērān-xwarrah-šābuhr «Glory of Ērān (of) Shapur». It also appears in the titles of government officers, such as in Ērān-āmārgar «Accountant-General of Ērān», Ērān-dibirbed «Chief Scribe of Ērān», and Ērān-spāhbed «Spahbed of Ērān».[2][10]

Because an equivalent of ērānšahr does not appear in Old Iranian (where it would have been *aryānām xšaθra- or in Old Persian *- xšaça-, «rule, reign, sovereignty»), the term is presumed[2] to have been a Sasanian-era development. In the Greek portion of Shapur’s trilingual inscription the word šahr «kingdom» appears as ethnous (genitive of «ethnos») «nation». For speakers of Greek, the idea of an Iranian ethnos was not new: The mid-5th-century BCE Herodotus (7.62) mentions that the Medes once called themselves Arioi.[6] The 1st century BCE Strabo cites the 3rd-century BCE Eratosthenes for having noted a relationship between the various Iranian peoples and their languages: «[From] beyond the Indus […] Ariana is extended so as to include some part of Persia, Media, and the north of Bactria and Sogdiana; for these nations speak nearly the same language.» (Geography, 15.2.1-15.2.8).[6] Damascius (Dubitationes et solutiones in Platonis Parmenidem, 125ff) quotes the mid-4th-century BCE Eudemus of Rhodes for «the Magi and all those of Iranian (áreion) lineage».[6] The 1st-century BCE Diodorus Siculus (1.94.2) describes Zoroaster as one of the Arianoi.[6]

In early Islamic times[edit]

The terms ērān/ērānšahr had no currency for the Arabic-speaking Caliphs, for whom Arabic al-‘ajam and al-furs («Persia») to refer to Western Iran (i.e. the territory initially captured by the Arabs and approximately corresponding to the present-day country of Iran) had greater traction than indigenous Iranian usage.[11]: 327 Moreover, for the Arabs ērān/ērānšahr were tainted by their association with the vanquished Sasanians, for whom being Iranian was also synonymous with being mazdayesn, i.e. Zoroastrian.[11]: 327 Accordingly, while the Arabs were generally quite open to Iranian ideas if it suited them, this did not extend to the nationalistic and religious connotations in ērān/ērānšahr, nor to the concomitant contempt of non-Iranians, which by the Islamic era also included Arabs and «Turks».

An inscription in Middle Persian on the tombstone of a Christian from Anatolia in the 9th century AD:

ēn gōr Hurdād [pusar ī Ohrmazdāfrīd] rāy ast, kū-š xvadāy bē āmurzād. az mān ī Ērānšahr, az rōdestāg Zargān, az deh Xišt

This grave is the grave of Khordad, the son of HormazdAfrid, may God bless him. From the land of «Iranshahr», from the region Zargan, from the village Khesht

The rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in the mid-8th century ended the Umayyad policy of Arab supremacy and initiated a revival of Iranian identity.[12] This was encouraged by the transfer of the capital from Syria to Iraq, which had been a capital province in Sasanian, Arsacid and Archaemenid times and was thus perceived to carry an Iranian cultural legacy. Moreover, in several Iranian provinces, the downfall of the Umayyads was accompanied by a rise of de facto autonomous Iranian dynasties in the 9th and 10th centuries: the Taherids, Saffarids and Samanids in eastern Iran and Central Asia, and the Ziyarids, Kakuyids and Buyids in central, southern and western Iran. Each of these dynasties identified themselves as «Iranian»,[12] manifested in their invented genealogies, which described them as descendants of pre-Islamic kings, and legends as well as the use of the title of shahanshah by the Buyid rulers.[12] These dynasties provided the «men of the pen» (ahl-e qalam), i.e. the literary elite, with an opportunity to revive the idea of Iran.

The best known of this literary elite was Ferdowsi, whose Shahnameh, completed around 1000 CE, is partly based on Sasanian and earlier oral and literary tradition. In Ferdowsi’s take on the legends, the first man and first king created by Ahura Mazda are the foundations of Iran.[12] At the same time, Iran is portrayed to be under threat from Aniranian peoples, who are driven by envy, fear and other evil demons (dews) of Ahriman to conspire against Iran and its peoples.[12] «Many of the myths surrounding these events, as they appear [in the Shahnameh], were of Sasanid origin, during whose reign political and religious authority become fused and the comprehensive idea of Iran was constructed.»[12]

In time, Iranian usage of ērān began to coincide with the dimensions of Arabic al-Furs, such as in the Tarikh-e Sistan which divides Ērānšahr into four parts and restricts ērān to only Western Iran, but this was not yet common practice in the early Islamic-era. At that early stage, ērān was still mostly the more general «(lands inhabited by) Iranians» in Iranian usage, occasionally also in the early Sasanian sense in which ērān referred to people, rather than to the state.[2] Notable among these is Farrukhi Sistani, a contemporary of Ferdowsi, who also contrasts ērān with ‘turan’, but—unlike Ferdowsi—in the sense of «land of the Turanians». The early Sasanian sense is also occasionally found in medieval works by Zoroastrians, who continued to use Middle Persian even for new compositions. The Denkard, a 9th-century work of Zoroastrian tradition, uses ērān to designate Iranians and anērān to designate non-Iranians. The Denkard also uses the phrases ēr deh, plural ērān dehān, to designate lands inhabited by Iranians. The Kar-namag i Ardashir, a 9th-century hagiographic collection of legends related to Ardashir I uses ērān exclusively in connection with titles, i.e. šāh-ī-ērān and ērān-spāhbed (12.16, 15.9), but otherwise calls the country Ērānšahr (3.11, 19; 15.22, etc.).[2] A single instance in the Book of Arda Wiraz (1.4), also preserves the gentilic in ērān dahibed distinct from the geographic Ērānšahr. However, these post-Sasanian instances where ērān referred to people rather than to the state, are rare, and by the early Islamic period the «general designation for the land of the Iranians was […] by then ērān (also ērān zamīn, šahr-e ērān), and ērānī for its inhabitants.»[2] That «Ērān was also generally understood geographically is shown by the formation of the adjective ērānag «Iranian,» which is first attested in the Bundahišn and contemporary works.»[2]

In the Zoroastrian literature of the medieval period, but apparently also perceived by adherents of other faiths,[11]: 328 Iranianness remained synonymous with Zoroastrianism. In these texts, other religions are not seen as «unzoroastrian», but as un-Iranian.[11]: 328 This is a major theme in the Ayadgar i Zareran 47, where ērīh «Iranianess» is contrasted with an-ērīh, and ēr-mēnišnīh «Iranian virtue» is contrasted with an-ēr-mēnišnīh. The Dadestan i Denig (Dd. 40.1-2) goes further, and recommends death for an Iranian who accepts a non-Iranian religion (dād ī an-ēr-īh).[11]: 328 Moreover, these medieval texts elevate the Avesta’s mythical Airyanem Vaejah (MP: ērān-wez) to the center of the world (Dd. 20.2), and give it a cosmogonical role, either (PRDd. 46.13) where for all plant life is created, or (GBd. 1a.12) where animal life is created.[11]: 327 Elsewhere (WZ 21), it is imagined to be the place where Zoroaster was enlightened. In Denkard III.312, humans are imagined to have first all lived there, until ordered to disperse by Vahman und Sros.[11]: 328 This ties in with an explanation given to a Christian by Adurfarnbag when asked why Ohrmazd only sent his religion to Ērānšahr.[11]: 328 Not all texts treat Iranianness and Zoroastrianism as synonymous. Denkard III.140, for instance, simply considers Zoroastrians to be the better Iranians.[11]: 329

The existence of a cultural concept of «Iranianness» (Irāniyat) is also demonstrated in the trial of Afshin in 840, as recorded by Tabari. Afshin, the hereditary ruler of Oshrusana, on the southern bank of the middle stretch of the Syr Darya, had been charged with propagating Iranian ethno-national sentiment.[12] Afshin acknowledged the existence of a national consciousness (al aʿjamiyya) and his sympathies for it. «This episode clearly reveals not only the presence of a distinct awareness of Iranian cultural identity and the people who actively propagated it, but also of the existence of a concept (al-aʿjamiya or Irāniyat) to convey it.»[12]

Modern usage[edit]

Qajar-era currency bill featuring a depiction of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar. It states: Issued from the imperial bank of Iran

During the Safavid era (1501–1736), most of the territory of the Sasanian empire regained its political unity, and Safavid kings were assuming the title of «Šāhanšāh-e Irān» (Iran’s king of kings).[12] An example is Mofid Bafqi (d. 1679), who makes numerous references to Iran, describing its border and the nostalgia of Iranians who had migrated to India in that era.[12] Even Ottoman sultans, when addressing the Aq Qoyunlu and Safavid kings, used such titles as the «king of Iranian lands» or the «sultan of the lands of Iran» or «the king of kings of Iran, the lord of the Persians».[12] This title, as well as the title of «Šāh-e Irān«, was later used by Nader Shah Afshar and Qajar and Pahlavi kings. Since 1935, the name «Iran» has replaced other names of Iran in the western world. Jean Chardin, who travelled in the region between 1673 and 1677, observed that «the Persians, in naming their country, make use of one word, which they indifferently pronounce Iroun, and Iran. […] These names of Iran and Touran, are frequently to be met with in the ancient histories of Persia; […] and even to this very day, the king of Persia is call’d Padsha Iran [padshah=’king’], and the great vizier, Iran Medary [i.e. medari=’facilitator’], the Pole of Persia«.[13]

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the official name of the country is «Islamic Republic of Iran».

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ In the Avesta the airiia- are members of the ethnic group of the Avesta-reciters themselves, in contradistinction to the anairiia-, the «non-Iranians», e.g. in Yasht 18’s airiianəm xᵛarənah, the divine «Iranian glory» granted by Ahura Mazda to vanquish the demonic daevas and other un-Iranian creatures. The word also appears four times in Old Persian: One is in the Behistun inscription, where ariya- is the name of a language or script (DB 4.89).[6] Additionally, the Elamite version corresponding DB IV 60 and 62 identifies Ahura Mazda as god of the Iranians.[6] The other three instances of Old Persian ariya- occur in Darius I’s inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam (DNa 14-15), in Darius I’s inscription at Susa (DSe 13-14), and in the inscription of Xerxes I at Persepolis (XPh 12-13).[6] In these, the two Achaemenid dynasts both describe themselves as pārsa pārsahyā puça ariya ariyaciça «a Persian, son of a Persian, an Iranian, of Iranian origin.» «The phrase with ciça, ‘origin, descendance,’ assures that it [i.e. ariya] is an ethnic name wider in meaning than pārsa and not a simple adjectival epithet.»[5] «There can be no doubt about the ethnic value of Old Iran. arya.»[6] «All [the] evidence shows that the name arya «Iranian» was a collective definition, denoting peoples […] who were aware of belonging to the one ethnic stock, speaking a common language, and having a religious tradition that centered on the cult of Ahura Mazdā.»[6]

- ^ The Middle Persian version of this inscription has not survived, but is reconstructable from the Parthian version, in which *ērānšahr appears as Parthian aryānšahr.

- Citations

- ^ Mallory 1991, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r MacKenzie, David Niel (1998), «Ērān, Ērānšahr», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 8, Costa Mesa: Mazda, p. 534.

- ^ Gignoux, Phillipe (1987), «Anērān», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger (1987), «Aryans», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 684–687.

- ^ a b Bailey, Harold Walter (1987), «Arya», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 681–683.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gnoli, Gherardo (2006), «Iranian identity II: Pre-Islamic period», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 13, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 504–507.

- ^ Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Sarah Stewart, Birth of the Persian Empire: The Idea of Iran, I.B.Tauris, 2005, ISBN 9781845110628, page 5

- ^ Markwart, J.; Messina, G. (1931), A catalogue of the provincial capitals of Eranshahr: Pahlavi text, version and commentary, Rome: Pontificio istituto biblico.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2002), Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr. A Middle Persian Text on Late Antique Geography, Epic, and History. With English and Persian Translations, and Commentary, Mazda Publishers.

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (1989), The Idea of Iran: an essay on its origin, Serie orientale Roma, vol. LXI, Rome/Leiden: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente/Brill.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stausberg, Michael (2011), «Der Zoroastrismus als Iranische Religion und die Semantik von ‘Iran’ in der zoroastrischen Religionsgeschichte», Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte, 63 (4): 313–331, doi:10.1163/157007311798293575.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ashraf, Ahmad (2006), «Iranian identity III: Medieval-Islamic period», Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 13, pp. 507–522.

- ^ Chardin, John (1927), Travels in Persia, 1673-1677, London: Argonaut, p. 126, fasc. reprint 1988, Mineola: Dover.

- См. Также имя Ирана.

современное персидское имя Иран (ایران) означает «земля ариев ». Оно происходит непосредственно от сасанидского среднеперсидского ērān (пехлеви написание: 𐭠𐭩𐭫𐭠𐭭, yrʼn), 3-го века, где изначально означало «из иранцев. «, но вскоре приобрела и географический оттенок в смысле» (земли, населенные) иранцами «. И в географическом, и в демоническом смысле ērān отличается от антонимического anērān, что означает «неиранский (ian)».

В географическом смысле ērān также отличался от ērānšahr, Сасанидское собственное название своей империи, которая также включала территории, которые не были заселены преимущественно этническими иранцами.

Содержание

- 1 В доисламском обиходе

- 2 В ранние исламские времена

- 3 Современные использование

- 4 Ссылки

В доисламском употреблении

Слово ērān впервые упоминается в надписях, сопровождающих освобождение от вложений Ардашир I (годы правления 224–242) в Накш-э Рустам. В этой двуязычной надписи король называет себя «Ардашир, царь царей из иранцев » (среднеперсидский : ardašīr šāhān šāh ērān; Парфянский : ардашир шахан шах и арьян). Среднеиранский ērān / aryān — это косые формы множественного числа от gentilic ēr- (среднеперсидский) и ary- (парфянский), которые, в свою очередь, происходят от древнеиранского * arya-, что означает «арийский, т. е. иранский». Этот древнеиранский * arya- засвидетельствован как этнический указатель в ахеменидских надписях как древнеперсидский ariya-, а в традиции зороастризма Avesta как авестийский airiia- / airya и т. д. «очень вероятно», что Ардашир I использовал среднеиранское ērān / Арьян по-прежнему сохранял то же значение, что и в древнеиранском языке, т.е. обозначая людей, а не империю.

Выражение «царь царей иранцев», найденное в надписи Ардашира, оставалось основным эпитетом всех сасанидских царей.. Точно так же надпись «поклоняющийся Мазде (маздесн) господин Ардашир, царь иранских царей», которая появляется на монетах Ардашира, также была принята преемниками Ардашира. Сын Ардашира и непосредственный преемник, Шапур I (годы правления 240 / 42–270 / 72) расширил титул до «Короля царей иранцев и неиранцев » (Среднеперсидский : MLKAn MLKA ‘yr’n W’ nyr’n šāhān šāh ī ērān ud anērān; Древнегреческий : βασιλεύς βασιλέων Αριανών basileús basiléōn, тем самым расширяя свои намерения Тоже иранцы, или потому, что большие территории империи были заселены неиранцами. В своей трехъязычной надписи на Ka’ba-ye Zartosht Шапур I также вводит термин * ērānšahr. Надпись Шапура включает список провинций его империи, в том числе регионы Кавказа, которые не были населены преимущественно иранцами. Антонимический анэраншахр засвидетельствован тридцатью годами позже в надписях Картира, первосвященника нескольких сасанидских царей. Надпись Картира также включает списки провинций, но, в отличие от Шапура, считает провинции на Кавказе анерраншахр. Эти два использования могут быть противопоставлены ērānšahr в понимании позднесасанидского Šahrestānīhā ī rānšahr, которое представляет собой описание различных провинциальных столиц ērānšahr, а также включает Африку и Аравию.

Несмотря на это письменное использование ērān для обозначения иранских народов, использование ērān для обозначения империи (и антонимического анерана для обозначения римских территорий) также засвидетельствовано ранним сасанидским периодом. И ērān, и anērān появляются в календарном тексте 3-го века, написанном Мани. Та же краткая форма снова появляется в названиях городов, основанных сасанидскими династами, например, в Ērān-xwarrah-šābuhr «Слава Арана (из) Шапура». Он также появляется в титулах правительственных чиновников, таких как Ērān-āmārgar «Главный бухгалтер rān», rān-dibirbed «Главный писец rān» и rān-spāhbed «Спахбед rān».

Поскольку эквивалент ērānšahr не встречается в древнеиранском языке (где это было бы * aryānām xšaθra- или в древнеперсидском * — xšaça- «правление, царствование, суверенитет»), предполагается, что этот термин были развитием сасанидской эпохи. В греческой части трехъязычной надписи Шапура слово šahr «царство» встречается как этнический «народ». Для носителей греческого языка идея иранского этноса не была новой: в середине V века до н. Э. Геродот (7.62) упоминает, что мидяне когда-то называли себя ариоями. I век до н.э. Страбон цитирует III век до н.э. Эратосфена за то, что он отметил связь между различными иранскими народами и их языками: «[Из] за пределами Инда […] Ариана расширена, чтобы включить некоторую часть Персии, Медии, а также север Бактрии и Согдиана ; ибо эти народы говорят почти на одном языке ». (География, 15.2.1-15.2.8). Дамаский (Dubitationes et solutiones in Platonis Parmenidem, 125ff) цитирует середину IV века до н.э. Евдема Родосского для «волхвов и всех иранских (áreion) родов». 1 век до н. Э. Диодор Сицилийский (1.94.2) описывает Зороастра как одного из арианоев.

В ранние исламские времена

термины ērān / ērānšahr не имели валюты для арабоязычных халифов, для которых арабский al-‘ajam и al-furs («Персия») означал Западный Иран (т.е. территорию, первоначально захваченную арабами и приблизительно соответствующую территории современной страны Иран) большая тяга, чем у коренных иранцев. Более того, для арабов ērān / ērānšahr были запятнаны своей связью с побежденными сасанидами, для которых быть иранцем также было синонимом mazdayesn, то есть зороастрийца. Соответственно, хотя арабы, как правило, были вполне открыты иранским идеям, если им это соответствовало, это не распространялось ни на националистические и религиозные коннотации в ērān / ērānšahr, ни на сопутствующее презрение к неиранцам, которые в исламскую эпоху также включали арабов и «Турки ».

Возвышение Аббасидского халифата в середине 8-го века положило конец Омейядской политике арабского превосходства и положило начало возрождению иранской идентичности. Этому способствовал перенос столицы из Сирии в Ирак, который был столичной провинцией во времена Сасанидов, Аршакидов и Археменидов и, таким образом, воспринимался как носитель иранского культурного наследия. Более того, в нескольких иранских провинциях падение Омейядов сопровождалось возникновением де-факто автономных иранских династий в IX и X веках: Тахеридов, Саффаридов и Саманиды в восточном Иране и Средней Азии, и Зияриды, Какуйиды и Буиды в центральном, южном и западном Иране. Каждая из этих династий идентифицировала себя как «иранскую», что проявлялось в придуманных ими генеалогиях, описывающих их как потомков доисламских царей, и легендах, а также использовании титула шаханшах правителями Буидов.. Эти династии предоставили «людям пера» (ахл-е калам), то есть литературной элите, возможность возродить идею Ирана.

Самым известным представителем этой литературной элиты был Фирдоуси, чей Шахнаме, завершенный около 1000 г. н.э., частично основан на сасанидских и более ранних устных и литературных традициях. Согласно легендам Фирдоуси, первый человек и первый царь, созданные Ахурой Маздой, лежат в основе Ирана. В то же время Иран изображается находящимся под угрозой со стороны аниранских народов, которые движимы завистью, страхом и другими злыми демонами (росами ) Аримана, чтобы сговориться против Ирана и его народы. «Многие из мифов, окружающих эти события, как они появляются [в Шахнаме], имели сасанидское происхождение, во время правления которых политический и религиозный авторитет слились воедино, и была построена всеобъемлющая идея Ирана».

Со временем Иранское использование ērān стало совпадать с размерами арабского al-Furs, например, в Tarikh-e Sistan, который делит rānšahr на четыре части и ограничивает ērān только Западным Ираном, но это еще не было обычная практика в раннюю исламскую эпоху. На той ранней стадии ērān все еще был в основном более общим «(заселенными) иранцами» в иранском использовании, иногда также в раннем сасанидском смысле, в котором ērān относился к людям, а не к государству. Среди них выделяется Фаррухи Систани, современник Фирдоуси, который также противопоставляет ērān «турану», но — в отличие от Фирдоуси — в смысле «земли туранцев». Ранний сасанидский смысл также иногда встречается в средневековых произведениях зороастрийцев, которые продолжали использовать среднеперсидский язык даже для новых композиций. Денкард, произведение 9-го века в зороастрийской традиции, использует ērān для обозначения иранцев и anērān для обозначения неиранцев. Денкард также использует фразы ēr deh, множественное число ērān dehān, для обозначения земель, населенных иранцами. Кар-намаг и Ардашир, агиографическое собрание легенд 9-го века, связанное с Ардаширом I, использует ērān исключительно в связи с титулами, т.е. šāh-ī-ērān и ērān-spāhbed (12.16, 15.9), но иначе называет страну rānšahr (3.11, 19; 15.22, и т. д.). Единственный экземпляр в Книге Арда Вираз (1.4) также сохраняет язычниковый в ērān dahibed, отличный от географического rānšahr. Однако эти постсасанидские случаи, когда ērān относился к людям, а не к государству, редки, и к раннему исламскому периоду «общее обозначение земли иранцев было […] к тому времени ērān (также ērān zamīn, šahr-e ērān) и ērānī для его жителей «. То, что «rān также обычно понимался географически, показано образованием прилагательного ērānag« иранский », которое впервые засвидетельствовано в Bundahišn и в современных работах»

В зороастрийской литературе В средневековый период, но, по-видимому, также воспринимаемый приверженцами других конфессий, иранство оставалось синонимом зороастризма. В этих текстах другие религии не рассматриваются как «не зороастрийские», а как неиранские. Это основная тема в Ayadgar i Zareran 47, где ērīh «иранство» противопоставляется ан-ērīh, а ēr-mēnišnīh «иранская добродетель» противопоставляется ан-ēr-mēnišnīh. Дадестан и Дениг (Дд. 40.1-2) идет дальше и рекомендует смерть иранцу, который принимает неиранскую религию (dād ī an-ēr-īh). Более того, эти средневековые тексты возносят мифический Airyanem Vaejah из Авесты (MP: ērān-wez) в центр мира (Dd. 20.2) и придают ему космогоническую роль (PRDd. 46.13), где ибо создается вся растительная жизнь или (GBd. 1a.12) где создается животная жизнь. В другом месте (WZ 21) предполагается, что это место, где Зороастр был просветлен. В Денкарде III.312 предполагается, что сначала все люди жили здесь, пока Вахман и Срос не приказали рассредоточиться. Это связано с объяснением, которое Адурфарнбаг дал христианину, когда его спросили, почему Ормазд отправил свою религию только в Шраншар. Не все тексты трактуют иранство и зороастризм как синонимы. Денкард III.140, например, просто считает зороастрийцев лучшими иранцами.

Существование культурной концепции «иранства» (ираният) также продемонстрировано в судебном процессе над Афсином в 840 году, как записано Табари. Афсин, потомственный правитель Ошрусаны, на южном берегу среднего участка Сырдарьи, был обвинен в пропаганде иранских этнонациональных настроений. Афсин признал существование национального самосознания (аль аджамийа) и сочувствовал ему. «Этот эпизод ясно показывает не только наличие отчетливого осознания иранской культурной самобытности и людей, которые активно ее пропагандировали, но и существование концепции (аль-аджамия или ираният), которая ее передает».

Современное употребление

В течение эпохи Сефевидов (1501–1736) большая часть территории Сасанидской империи восстановила свое политическое единство, и Сефевиды цари принимали титул «Шаханшах-и Иран» (царь царей Ирана). Примером может служить Мофид Бафки (ум. 1679), который делает многочисленные ссылки на Иран, описывая его границу и ностальгию иранцев, мигрировавших в Индию в ту эпоху. Даже османские султаны, обращаясь к Ак Коюнлу и царям Сефевидов, использовали такие титулы, как «царь иранских земель» или «султан земель Ирана» или «царь царей Ирана, владыка персов ». Этот титул, как и титул «Шах-и Иран», позже использовался королями Надир Шах Афшар, Каджар и Пехлеви. С 1935 года название «Иран» заменило другие названия Ирана в западном мире. Жан Шарден, который путешествовал по региону между 1673 и 1677 годами, заметил, что «персы, называя свою страну, используют одно слово, которое они безразлично произносят Ирун, и Иран. […] Эти имена Ирана и Турана часто можно встретить в древних историях Персии; […] и даже по сей день царь Персии зовется Падша Иран [падшах = «царь»], и великий визирь Иран Медари [т.е. медари = «посредник»], Полюс Персии ».

После Иранской революции 1979 года официальное название страны -« Исламская Республика Иран «.

Ссылки

- Примечания

- Библиография

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- Irân, Irān, Îrân, Īrān (all rare)

Etymology[edit]

From Persian ایران (irân), from Middle Persian 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ʾērān, “of the Aryans”). See 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ʾērān) for word formation, further etymology and cognates.

The name of the political entity is a 3rd-century development that derives from the indigenous ethnolinguistic name of the Iranian peoples,[1] i.e. the great variety of Iranian tribes that spoke an Iranian language.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (UK) IPA(key): /ɪˈɹɑːn/, /ɪˈɹæn/[2]

- (US) IPA(key): /ɪˈɹɑːn/, /ɪˈɹæn/, /aɪˈɹæn/[3]

- Rhymes: -ɑːn, -æn

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- A country in West Asia. Official name: Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ca. 1675, Jean Chardin (Sir John Chardin), Travels in Persia, 1673-1677, fasc. reprint 1988, Dover, page 126:

- «The Persians, in naming their country, make use of one word, which they indifferently pronounce Iroun, and Iran.»

- 2005, Massoume Price, ed., Iran’s Diverse Peoples, ABC-Clio, page xiii:

- «Iran is a vast and ancient country in a strategic location in the Middle East. It borders Russia, Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan, the Gulf of Oman, and the Persian Gulf.»

- ca. 1675, Jean Chardin (Sir John Chardin), Travels in Persia, 1673-1677, fasc. reprint 1988, Dover, page 126:

- (literary, technical) regions inhabited by the Iranian peoples.

- 1882, James Darmesteter, The Zend-Avesta, volume 1 (SBE, volume 31), Oxford UP, page 7, xxviii:

- «Kavi means a king, but it is particularly used of the kings belonging to the second and most celebrated of the two mythical dynasties of Iran.»

- «One certain fact is the occurrence of geographical names [Bactria, Sogdiana, etc] in Vendidad I, which are obviously intended to describe the earliest homes of the Iranian races whose lore was the Avesta.»

-

1898, A. V. W. Jackson, Zoroaster: The Prophet of Ancient Iran, Macmillan, page 10:

-

«Zoroaster of Iran. — Zoroaster, it is believed, sprang up in the seventh century before the Christian era, somewhere in the land between the Indus and the Tigris.»

-

- 1909, John Huston Finley (ed.), «Iran» in Nelson’s Perpetual Loose-leaf Encyclopaedia, volume 6, page 479:

- «Iran. in early times, the name applied to the great Asiatic plateau which comprised the entire region from the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and Russian Turkestan on the north to the Tigris, the Persian Gulf, and the Arabian Sea on the west and south, and extending to the Indus on the east, likewise comprising the modern Afghanistan and the territory to the north of it as far as the Jaxartes River.»

- 1985, J. M. Cooke, «The Rise of the Achaemenids» in Cambridge Historiy of Iran, volume 2, page 290:

- «[W]e may surmise that there was a strong sense of Iranian unity lending solidarity to the eastern half of the empire. It is only in the generations after Alexander, in Eudemus and in Eratosthenes (ap. Strabo), that we find mention of the concept of a greater nation of Iran (Arianē) stretching from the Zagros to the Indus; but the sense of unity must have been there, for Herodotus tells us that the Medes were formerly called Arioi, and Darius I (followed by Xerxes) in his inscriptions proclaims himself an Iranian (Ariya) by race — he speaks of himself in ascending order as an Achaemenid, a Persian and an Iranian (Naqsh-i Rustam).»

- 1990, Hubert Darke, «Cambridge History of Iran» in Encyclopedia Iranica, volume 4, page 724:

- «[The] Cambridge History of Iran [is] a survey of the history and historical geography of the land which is present-day Iran, as well as other territories inhabited by peoples of Iranian descent.»

- 1882, James Darmesteter, The Zend-Avesta, volume 1 (SBE, volume 31), Oxford UP, page 7, xxviii:

Derived terms[edit]

[edit]

- Iranian

Translations[edit]

country in Western Asia

- Abkhaz: Џьамтәыла (Džamtʷʼəla)

- Adyghe: Иран (Jiraan)

- Afrikaans: Iran

- Albanian: Iran m

- Amharic: የኢራን (yäʾiran)

- Arabic: إِيرَان (ar) f (ʔīrān)

- Aramaic:

- Syriac: ܐܝܪܐܢ, ܐܝܖܐܢ (archaic)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic: ܐܝܼܪܵܢ (iran)

- Armenian: Իրան (hy) (Iran)

- Assamese: ইৰান (iran)

- Asturian: Irán (ast)

- Avar: Ира́н (İrán)

- Azerbaijani: İran (az)

- Bashkir: Иран (İran)

- Belarusian: Іра́н m (Irán)

- Bengali: ইরান (bn) (iran)

- Brahui: Írán

- Breton: Iran (br)

- Bulgarian: Ира́н (bg) m (Irán)

- Burmese: အီရန် (iran)

- Catalan: Iran (ca) m

- Chechen: Иран (İran)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 伊朗 (ji1 long5)

- Mandarin: 伊朗 (zh) (Yīlǎng)

- Min Nan: 伊朗 (I-lang)

- Wu: 伊朗 (hhi laan)

- Czech: Írán (cs) m

- Danish: Iran (da) n

- Dutch: Iran (nl) n

- Dzongkha: ཨི་རཱན་ (i rān)

- Esperanto: Irano (eo)

- Estonian: Iraan (et)

- Faroese: Iran n

- Finnish: Iran (fi)

- French: Iran (fr) m

- Galician: Irán (gl) m

- Georgian: ირანი (ka) (irani)

- German: Iran (de) m

- Greek: Ιράν (el) n (Irán)

- Gujarati: ઈરાન (īrān)

- Hausa: Iran

- Hawaiian: ʻIlana

- Hebrew: אִירָאן f (irán)

- Hindi: ईरान (hi) m (īrān), फारस (hi) m (phāras), पारस (hi) m (pāras)

- Hungarian: Irán (hu)

- Icelandic: Íran (is)

- Indonesian: Iran (id)

- Interlingua: Iran

- Irish: an Iaráin f

- Italian: Iran (it) m

- Japanese: イラン (ja) (Iran)

- Kabardian: Къажэрей (Qaažereej)

- Kalenjin: Iran

- Kamba: Iran

- Kannada: ಇರಾನ್ (kn) (irān)

- Kashmiri: ایٖران (īrān)

- Kazakh: Иран (İran)

- Khmer: អ៊ីរ៉ង់ (km) (ʼiirɑng)

- Kikuyu: Iran

- Korean: 이란 (ko) (Iran)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: ئێران (ckb) (êran)

- Northern Kurdish: Îran (ku)

- Kyrgyz: Иран (ky) (İran)

- Lao: ອີລ່ານ (ʼī lān)

- Latgalian: Irans m

- Latin: Irania f

- Latvian: Irāna f

- Lithuanian: Iranas (lt) m

- Luhya: Iran

- Macedonian: Иран (mk) m (Iran)

- Malay: Iran

- Malayalam: ഇറാൻ (ml) (iṟāṉ)

- Maltese: l-Iran (mt) m

- Maori: Īrāna

- Marathi: इराण (irāṇ)

- Mazanderani: ایران (iran)

- Meru: Iran

- Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ērān), 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭𐭱𐭲𐭥𐭩 (ʾyʿʾnštʿy)[[Category:|IRAN]]

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: Иран (mn) (Iran)

- Mongolian: ᠢᠷᠠᠨ (iran)

- Navajo: Iiwą́ą́

- Nepali: इरान (irān)

- Norman: Iraun m, Iran m

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: Iran (no)

- Nynorsk: Iran (nn)

- Oriya: ଇରାନ (iranô)

- Ossetian: Иран (Iran)

- Parthian: 𐭀𐭓𐭉𐭀𐭍 (aryān)

- Pashto: ايران m (irān)

- Persian: ایران (fa) (irân), ایرون (irun) (colloquial, Tehran)

- Polish: Iran (pl)

- Portuguese: Irã (pt) m (Brazil) , Irão (pt) m (Portugal)

- Punjabi: ਇਰਾਨ (irān)

- Romanian: Iran (ro) n

- Russian: Ира́н (ru) m (Irán)

- Sanskrit: ईरान (īrāna)

- Santali: ᱤᱨᱟᱱ (iran)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: Ѝра̄н m

- Roman: Ìrān (sh) m

- Sindhi: ايران

- Sinhalese: ඉරානය (irānaya)

- Slovak: Irán (sk) m

- Slovene: Iran (sl) m

- Spanish: Irán (es) m

- Swahili: Uajemi

- Swedish: Iran (sv) n

- Tagalog: Iran

- Tajik: Эрон (tg) (Eron), Ирон (Iron)

- Tamil: ஈரான் (īrāṉ)

- Tatar: Иран (İran)

- Telugu: ఇరాన్ (te) (irān)

- Thai: อิหร่าน (th) (ì-ràan)

- Tibetan: ཡི་ལང (yi lang)

- Tigrinya: ኢራን (ʾiran)

- Turkish: İran (tr)

- Turkmen: Eýran

- Ukrainian: Іра́н (uk) m (Irán)

- Urdu: اِیران m (īrān)

- Uyghur: ئىران (iran)

- Uzbek: Eron (uz)

- Vietnamese: Y Lãng, I-ran

- Volapük: Lirän (vo)

- Western Panjabi: ایران (pnb)

- Yiddish: איראַן (iran)

- Yoruba: Irani

See also[edit]

- Persia (archaic exonym)

- (countries of Asia) country of Asia; Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Cyprus, East Timor, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Syria, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Yemen

References[edit]

- ^ MacKenzie, David Niel (1998). «Ērān, Ērānšahr». Encyclopedia Iranica, volume 8. Costa Mesa: Mazda, page 534.

- ^ “Iran”, in Lexico, Dictionary.com; Oxford University Press, 2019–2022.

- ^ “Iran”, in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster, 1996–present.

Anagrams[edit]

- ARIN, Arin, NIRA, Nair, RNAi, Rani, Rian, Rina, arni, rain, rani

Afrikaans[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

Albanian[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m (definite Irani)

- Iran (a country in Western Asia; capital: Tehran)

Inflection[edit]

Declension of Iran

| indefinite | definite | |

|---|---|---|

| nominative | Iran | Irani |

| accusative | Iran | Iranin |

| dative | Irani | Iranit |

| ablative |

Derived terms[edit]

- iranian, iraniane

Breton[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran ?

- Iran

Catalan[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Balearic, Central, Valencian) IPA(key): /iˈɾan/

- Rhymes: -an

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m

- Iran

Usage notes[edit]

- Catalan uses the definite article l’ in front of Iran, but not in enumerations (such as «Canada, China and Iran are big countries.»)

Derived terms[edit]

- iranià

Central Nahuatl[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran (a country in Asia)

Danish[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

Derived terms[edit]

- iransk

Dutch[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Ultimately from Persian ایران (irân), from Middle Persian 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ʾyʿʾn)[[Category:|IRAN]]. This etymology is incomplete. You can help Wiktionary by elaborating on the origins of this term.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /iˈrɑn/, (somewhat dated) /iˈraːn/, (dated) /ˈiː.rɑn/

- Hyphenation: Iran

Proper noun[edit]

Iran n

- Iran

[edit]

- Iraans, Iraanse

- Iraniër

See also[edit]

- Perzisch (archaic exonym)

Faroese[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈiːɹan/

- Homophone: iðran

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

Declension[edit]

| Singular | |

| Indefinite | |

| Nominative | Iran |

| Accusative | Iran |

| Dative | Irani |

| Genitive | Irans |

[edit]

- iranskur

Anagrams[edit]

- Arni

- Rani

Finnish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Persian ایران.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈirɑn/, [ˈirɑn]

- Rhymes: -irɑn

- Syllabification(key): I‧ran

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

Declension[edit]

| Inflection of Iran (Kotus type 6/paperi, no gradation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| nominative | Iran | — | |

| genitive | Iranin | — | |

| partitive | Irania | — | |

| illative | Iraniin | — | |

| singular | plural | ||

| nominative | Iran | — | |

| accusative | nom. | Iran | — |

| gen. | Iranin | ||

| genitive | Iranin | — | |

| partitive | Irania | — | |

| inessive | Iranissa | — | |

| elative | Iranista | — | |

| illative | Iraniin | — | |

| adessive | Iranilla | — | |

| ablative | Iranilta | — | |

| allative | Iranille | — | |

| essive | Iranina | — | |

| translative | Iraniksi | — | |

| instructive | — | — | |

| abessive | Iranitta | — | |

| comitative | See the possessive forms below. |

| Possessive forms of Iran (type paperi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anagrams[edit]

- Arin, arin

French[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /i.ʁɑ̃/

- Rhymes: -ɑ̃

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m

- Iran (a country in Western Asia, in the Middle East)

Derived terms[edit]

- République islamique d’Iran

[edit]

- iranien, iranienne

See also[edit]

- persane (archaic exonym)

- Perse (archaic exonym)

See also[edit]

- (countries of Asia) pays d’Asie; Afghanistan, Arabie saoudite, Arménie, Azerbaïdjan, Bahreïn, Bangladesh, Bhoutan, Birmanie, Brunei, Cambodge, Chine, Chypre, Corée du Nord, Corée du Sud, Émirats arabes unis, Géorgie, Inde, Indonésie, Iran, Irak, Israël, Japon, Jordanie, Kazakhstan, Kirghizistan, Koweït, Laos, Liban, Malaisie, Maldives, Mongolie, Népal, Oman, Ouzbékistan, Pakistan, Philippines, Qatar, Russie, Singapour, Sri Lanka, Syrie, Tadjikistan, Thaïlande, Timor oriental, Turquie, Turkménistan, Vietnam, Yémen (Category: fr:Countries in Asia)

German[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /iˈʁaːn/

- Rhymes: -aːn

Proper noun[edit]

Iran n (proper noun, genitive Irans or (optionally with an article) Iran)

- Iran (a country in Western Asia)

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m (proper noun, strong, genitive Irans or Iran)

- Iran (a country in Western Asia)

Usage notes[edit]

- The word is sometimes used without a definite article as in English: Iran, in Iran. In this case, the genitive is always Irans, for example Irans Hauptstadt – «Iran’s capital».

- More commonly, however, the definite article is used with the name: der Iran, im Iran. In this case, the genitive usually is des Iran, although des Irans is also correct: die Hauptstadt des Iran(s) – «the capital of Iran».

Derived terms[edit]

- Iraner

- iranisch

[edit]

- Iranier

See also[edit]

- Perser (archaic exonym)

- Persien (archaic exonym)

- persisch (archaic exonym)

- Persisch (archaic exonym)

Further reading[edit]

- “Iran” in Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache

Indonesian[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Persian ایران (irân), from Middle Persian 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ʾērān, “of the Aryans”). See 𐭠𐭩𐭥𐭠𐭭 (ʾērān) for word formation, further etymology and cognates. Doublet of aria, arya, Arya, and ayah.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): [ˈiran]

- Hyphenation: I‧ran

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

See also[edit]

- (countries of Asia) negara-negara di Asia; Afganistan, Arab Saudi, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei, Filipina, India, Indonesia, Irak, Iran, Israel, Jepang, Kamboja, Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Korea Selatan, Korea Utara, Kuwait, Laos, Libanon, Maladewa, Malaysia, Mesir, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Palestina, Qatar, Rusia, Singapura, Siprus, Sri Lanka, Suriah, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor Leste, Tiongkok, Turki, Turkmenistan, Uni Emirat Arab, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Yaman, Yordania

Further reading[edit]

- “Iran” in Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia, Jakarta: Language Development and Fostering Agency — Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic Indonesia, 2016.

Interlingua[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

Italian[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈi.ran/, (traditional) /iˈran/[1]

- Rhymes: -iran, (traditional) -an

- Hyphenation: Ì‧ran, (traditional) I‧ràn

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m

- Iran

[edit]

- iraniano

- iranico

- iranista

See also[edit]

- Persia (archaic exonym)

References[edit]

- ^ Iran in Luciano Canepari, Dizionario di Pronuncia Italiana (DiPI)

Anagrams[edit]

- Rina, nari

Japanese[edit]

Romanization[edit]

Iran

- Rōmaji transcription of イラン

Norwegian Bokmål[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

[edit]

- iraner

- iransk

Norwegian Nynorsk[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran

- Iran

[edit]

- iranar

- iransk

Polish[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈi.ran/

- Rhymes: -iran

- Syllabification: I‧ran

Proper noun[edit]

Iran m

- Iran (a country in Western Asia, in the Middle East)

Declension[edit]

Derived terms[edit]

- irański

- Iranka

- Irańczyk

Further reading[edit]

- Iran in Wielki słownik języka polskiego, Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN

- Iran in Polish dictionaries at PWN

Romanian[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran n

- Iran

Serbo-Croatian[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ǐraːn/

- Hyphenation: I‧ran

Proper noun[edit]

Ìrān m (Cyrillic spelling Ѝра̄н)

- Iran

Declension[edit]

Declension of Iran

| singular | |

|---|---|

| nominative | Ìrān |

| genitive | Irána |

| dative | Iranu |

| accusative | Iran |

| vocative | Irane |

| locative | Iranu |

| instrumental | Iranom |

Swedish[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Iran n (genitive Irans)

- Iran

Derived terms[edit]

- iranier

- iransk

Anagrams[edit]

- inar, rian

Tagalog[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Borrowed from Spanish Irán (“Iran”).

Pronunciation[edit]

- Hyphenation: I‧ran

- IPA(key): /ʔiˈɾan/, [ʔɪˈɾan]

Proper noun[edit]

Irán

- Iran (a country in Western Asia)

Welsh[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ɪˈran/

- Rhymes: -an

Proper noun[edit]

Iran f

- Iran (a country in Asia)

Derived terms[edit]

- Gweriniaeth Islamaidd Iran (“Islamic Republic of Iran”)

Mutation[edit]

| Welsh mutation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| radical | soft | nasal | h-prothesis |

| Iran | unchanged | unchanged | Hiran |

| Note: Some of these forms may be hypothetical. Not every possible mutated form of every word actually occurs. |

- См. Также название Ирана .

Современное персидское название Ирана ( ایران ) означает «землю ариев ». Оно происходит непосредственно от сасанидского среднеперсидского ērān ( написание пехлеви : 𐭠𐭩𐭫𐭠𐭭, yrʼn ), которое первоначально означало « иранцев », но вскоре также приобрело географический оттенок в смысле «(земли, населенные) иранцами». . И в географическом, и в демоническом смыслах ērān отличается от антонимического anērān , что означает « неиранский (ian)».

В географическом смысле ērān также отличался от ērānšahr , собственного названия сасанидской империи, и которое также включало территории, которые в основном не были населены этническими иранцами .

В доисламском использовании

Слово ERAN сначала засвидетельствовано в надписях , которые сопровождают рельеф инвеституру Ардашира I ( т. 224-242) в Накш-е Рустам . В этой двуязычной надписи, царь называют себя «Ардаширом, царем царей этих иранцев » ( среднеперсидский : ardašīr Şahan с ī Эран ; Парфянским : ardašīr Şahan с ī арийскими ). Средний Иранский Эран / арийской являются наклонные формы множественного числа gentilic эргодиче- (среднеперсидская) и ary- (Парфянская), который в свою очередь , порождён Старый иранца * arya- , что означает «„ариец“, то есть«иранцев. »Этот старый иранский * arya- удостоверяются в качестве этнического обозначения в ахеменидских надписи , как древнеперсидские ariya- , и в зороастризме в Авесте традиции как Avestan airiia- / airya и т.д. Это„весьма вероятно“ , что использование Ардашира I в Среднем иранце ērān / aryān все еще сохранял то же значение, что и в древнеиранском языке, т.е. обозначая людей, а не империю.

Выражение «царь иранских царей» из надписи Ардашира оставалось общим эпитетом для всех сасанидских царей. Точно так же надпись «поклоняющийся Мазде ( маздесн ) господин Ардашир, царь иранских царей», которая появляется на монетах Ардашира, также была принята преемниками Ардашира. Сын Ардашира и непосредственный преемник Шапур I ( . Г 240 / 42-270 / 72) продлили название на «Царь царей иранцев и не-иранцев » ( среднеперсидский : MLKAn MLKA «yr’n W» šāhān šāh ērān ud anērān ; древнегреческий : βασιλεύς βασιλέων Αριανών basileús basiléōn Arianṓn ), тем самым расширяя свое намерение править и неиранцами , или потому, что большие территории империи были населены неиранцами. В своей трехъязычной надписи в Ka’ba-ye Zartosht Шапур I также вводит термин * ērānšahr . Надпись Шапура включает список провинций его империи, в том числе регионы на Кавказе , которые не были населены преимущественно иранцами. Антонимический anērānšahr засвидетельствовано от спустя тридцать лет в надписях Картира , Первосвященник , под несколькими сасанидских царей. Надпись Картира также включает в себя списки провинций, но, в отличие от Шапура, считает провинции на Кавказе анерраншахр . Эти два использования могут быть противопоставлены ērānšahr в понимании позднесасанидского Šahrestānīhā ī rānšahr , которое является описанием различных столиц провинций ērānšahr , а также включает Африку и Аравию.

Несмотря на это письменное использование ērān для обозначения иранских народов , использование ērān для обозначения империи (и антонимического anērān для обозначения римских территорий) также засвидетельствовано ранним сасанидским периодом. И ērān, и anērān появляются в календарном тексте 3-го века, написанном Мани . Такая же краткая форма снова появляется в названиях городов, основанных сасанидскими династами, например, в Ērān-xwarrah-šābuhr «Слава Арана (из) Шапура». Он также появляется в титулах правительственных чиновников, таких как rān-āmārgar « Главный бухгалтер rān », rān-dibirbed «Главный писец rān » и rān -spāhbed « Спахбед rān ».

Поскольку эквивалент ērānšahr не встречается в древнеиранском языке (где это было бы * aryānām xšaθra- или в древнеперсидском * — xšaça- , «власть, господство, суверенитет»), предполагается, что этот термин относится к эпохе Сасанидов. разработка. В греческой части трехъязычной надписи Шапура слово šahr «царство» появляется как этнос (родительный падеж слова «этнос») «нация». Для носителей греческого языка идея иранского этноса не была новой: в середине V века до н. Э. Геродот (7.62) упоминает, что мидяне когда-то называли себя ариоями . Первом веке до нашей эры Страбон цитирует 3-го века до н.э. Эратосфен для отметив связь между различными ираноязычных народов и их языков: «[С] за пределы Инд […] Ариана распространяется так, чтобы включить какую — то часть Персии , Мидия , север Бактрии и Согдианы , потому что эти народы говорят почти на одном языке ». ( География , 15.2.1-15.2.8). Дамаский ( Dubitationes ЕТ solutiones в Platonis Parmenidem , 125ff) цитирует в середине 4-го века до н.э. Евдем Родосский для «волхвов и всех тех , кто из Ирана ( Areion ) линии». 1 век до н.э. Диодор Сицилийский (1.94.2) описывает Зороастра как одного из арианоев .

В ранние исламские времена

Термины Эран / ērānšahr было никакой валюты для арабоязычных халифов, для которых арабского аль-‘ajam и аль-меха ( «Персия») не ссылаться на Западный Иран (то есть территория изначально захвачены арабами и примерно соответствует современная страна Иран) пользовалась большей популярностью, чем местные жители Ирана. Более того, для арабов ērān / ērānšahr были запятнаны своей связью с побежденными сасанидами, для которых быть иранцем было также синонимом mazdayesn , т. Е. Зороастрийца. Соответственно, хотя арабы, как правило, были вполне открыты иранским идеям, если это им соответствовало, это не распространялось ни на националистические и религиозные коннотации в ērān / ērānšahr , ни на сопутствующее презрение к неиранцам, которые в исламскую эпоху также включали арабов. и « турки ».

Подъем Аббасидского халифата в середине 8-го века положил конец омейядской политике арабского превосходства и положил начало возрождению иранской идентичности. Этому способствовал перенос столицы из Сирии в Ирак, который был столичной провинцией во времена Сасанидов, Аршакидов и Археменидов и, таким образом, воспринимался как носитель иранского культурного наследия. Более того, в нескольких иранских провинциях падение Омейядов сопровождалось возникновением де-факто автономных иранских династий в IX и X веках: Тахеридов , Саффаридов и Саманидов в восточном Иране и Центральной Азии, а также Зияридов , Какуйидов и Буидов. в центральном, южном и западном Иране. Каждая из этих династий идентифицировала себя как «иранскую», что проявлялось в придуманных ими генеалогиях, описывающих их как потомков доисламских царей, и легендах, а также использовании титула шаханшах правителями Буидов. Эти династии предоставили «людям пера» ( ахл-е калам ), т. Е. Литературной элите, возможность возродить идею Ирана.

Самым известным представителем этой литературной элиты был Фирдоуси , чья « Шахнаме» , завершенная около 1000 г. н.э., частично основана на сасанидских и более ранних устных и литературных традициях. Согласно легендам Фирдоуси, первый человек и первый царь, созданные Ахурой Маздой, лежат в основе Ирана. В то же время, Иран изображали находиться под угрозой со стороны Aniranian народов, которые приводятся в движение зависть, страх и другие злые демоны ( роса ы ) от Ахримана заговоры против Ирана и его народов. «Многие из мифов, окружающих эти события, как они появляются [в Шахнаме ], имели сасанидское происхождение, во время правления которых политический и религиозный авторитеты слились воедино, и была построена всеобъемлющая идея Ирана».

Со временем иранское использование ērān стало совпадать с размерами арабского al-Furs, например, в Tarikh-e Sistan, который делит rānšahr на четыре части и ограничивает ērān только Западным Ираном, но это еще не было распространенной практикой в ранняя исламская эпоха. На той ранней стадии ērān все еще был в основном более общим «(землями, населенными) иранцами» в иранском использовании, иногда также в раннем сасанидском смысле, в котором ērān относился к людям, а не к государству. Среди них выделяется Фаррухи Систани , современник Фирдоуси, который также противопоставляет ērān «турану», но — в отличие от Фирдоуси — в смысле «земли туранцев». Ранний сасанидский смысл также иногда встречается в средневековых произведениях зороастрийцев, которые продолжали использовать среднеперсидский язык даже для новых композиций. Denkard , работа девятого века зороастрийской традиции, использует Эран для обозначения иранцев и anērān для обозначения не-иранцев. Denkard также использует фразу Е.Р. DEH , множественное Эран dehān , для обозначения земель населенных иранцев. Кар-namag я Ардашир , агиографический коллекция девятых веков легенд , связанный с использованиями Ардашира I Эран исключительно в связи с названиями, т.е. SAH-I-Эран и Эран-spāhbed (12,16, 15,9), но в остальном называют страну Ērānšahr ( 3.11, 19; 15.22 и др.). Единственный экземпляр в Книге Арда Вираз (1.4) также сохраняет язычниковый в ērān dahibed, отличный от географического rānšahr. Однако эти постсасанидские случаи, когда ērān относился к людям, а не к государству, редки, и к раннему исламскому периоду «общее обозначение земли иранцев было […] к тому времени ērān (также ērān zamīn , šahr-e ērān ) и ērānī для его жителей «. То, что «rān также в целом понимался географически, показано образованием прилагательного ērānag « иранский », которое впервые засвидетельствовано в Бундахишне и современных трудах».

В зороастрийской литературе средневековья, но, очевидно, также воспринимаемой приверженцами других конфессий, иранство оставалось синонимом зороастризма. В этих текстах другие религии не рассматриваются как «не зороастрийские», а как неиранские. Это основная тема в Ayadgar i Zareran 47, где ērīh «иранство» противопоставляется ан-ērīh , а ēr-mēnišnīh «иранская добродетель» противопоставляется ан-ēr-mēnišnīh . « Дадестан и дениг» ( Дд . 40.1-2) идет дальше и рекомендует смерть иранцу, который принимает неиранскую религию ( dād ī an-ēr-īh ). Более того, эти средневековые тексты возносят мифический Airyanem Vaejah из Авесты (MP: ērān-wez ) в центр мира ( Dd . 20.2) и придают ему космогоническую роль ( PRDd. 46.13 ), где для всех создается растительная жизнь. , или ( GBd . 1a.12), где создана животная жизнь. В другом месте (WZ 21) предполагается, что это место, где был просвещен Зороастр. В Denkard III.312, люди задумали есть сначала все жили там, пока не приказал дисперсных по Vahman унд ОСР . Это связано с объяснением, которое Адурфарнбаг дал христианину, когда его спросили, почему Ормазд отправил свою религию только в Шраншар. Не все тексты трактуют иранство и зороастризм как синонимы. Денкард III.140, например, просто считает зороастрийцев лучшими иранцами.

Существование культурной концепции «иранства» (ираният) также продемонстрировано в суде над Афшином в 840 году, как записано Табари. Афшин, потомственный правитель Ошрусаны, расположенного на южном берегу среднего течения Сырдарьи , был обвинен в пропаганде иранских этнонациональных настроений. Афшин признал существование национального самосознания ( аль аджамийа ) и его симпатии к нему. «Этот эпизод ясно показывает не только наличие отчетливого осознания иранской культурной самобытности и людей, которые активно ее пропагандировали, но и существование концепции ( аль-аджамия или ираният ), которая ее передает».

Современное использование

В эпоху Сефевидов (1501–1736) большая часть территории Сасанидской империи восстановила свое политическое единство, и сефевидские цари принимали титул « Шаханшах-э Иран » (царь царей Ирана). Примером может служить Мофид Бафки (ум. 1679), который делает многочисленные ссылки на Иран, описывая его границу и ностальгию иранцев, мигрировавших в Индию в ту эпоху. Даже османские султаны, обращаясь к царям Ак Коюнлу и Сефевидов, использовали такие титулы, как «царь иранских земель» или «султан земель Ирана» или «царь царей Ирана, владыка персов». Это название, а также название « SAH-е Irán », позже была использована Надер Шах Afshar и Каджаров и Пехлеви королей. С 1935 года название «Иран» заменило другие названия Ирана в западном мире. Жан Шарден , путешествовавший по региону между 1673 и 1677 годами, заметил, что «персы, называя свою страну, используют одно слово, которое они безразлично произносят Ирун и Иран . […] Эти имена Ирана и Турана , часто можно встретить в древних историях Персии; […] и даже по сей день царь Персии зовется Падша Иран [ падшах = «царь»], а великий визирь Иран Медари [т.е. медари = «посредник»], Персидский полюс ».

После иранской революции 1979 года официальное название страны — «Исламская Республика Иран».

использованная литература

- Примечания

- Библиография

The names of countries are intertwined with the political, cultural, and spiritual history of those countries and their people.

This is especially true in the case of Iran (ایران), the name of which goes back for millennia, as well as the cultural and spiritual heritage of that country.

In Classical Persian literature we have, besides Iran, three other names that are equal in meaning to Iran: Irānzamīn, Irānšahr, and Šahr-i Irān, all basically meaning ‘the land of the Iranians’.

Here is a beautiful verse from Nizami Ganjavi, indicating how important was the idea of Iran for Iranians themselves:

همه عالم تن است و ایران دل

نیست گوینده زین قیاس خجل

hame ‘ālam tan ast va Irān del

nist guyande rā zin qiyas xajel

All the world is the body and Iran [is] the heart

Such comparison shall not bring shame to the bard.

Nizami Ganjavi

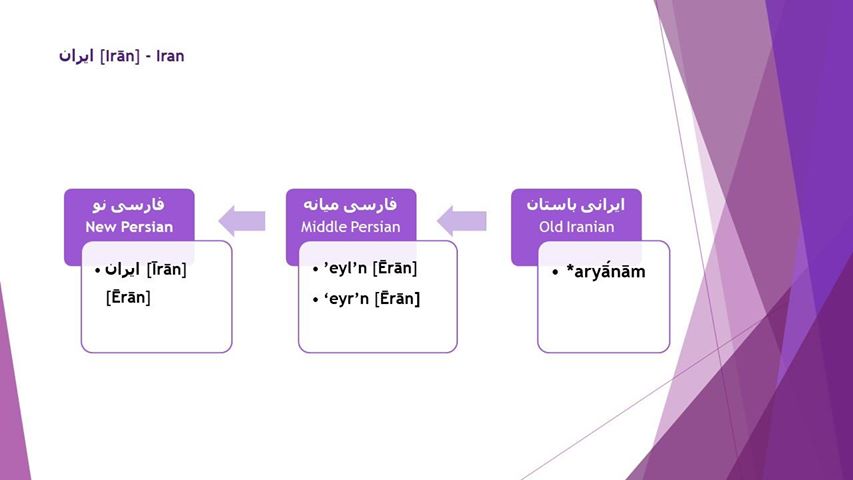

The modern form of the word Iran goes back to the Middle Persian form Ērān, which we meet both in the Zoroastrian Pahlavi and Manichaean religious and secular texts. It should be noted that in the Classical period of Persian literature (around 1000 AD), the word ایران (Irān) was pronounced as Ērān, and not Irān (the pronunciation has changed since).

In turn, the MP form Ērān goes back to the Old Iranian reconstructed form *aryā́nām, which is the genitive plural of *arya-, by which name the ancestors of the modern Iranian and Indian peoples used to call themselves.

The change from OI *aryā́nām to the more recent Ērān/Irān apparently happened because of the stress on the penultimate ā, which caused the final syllable to be dropped.

In the following chart you will be able to see how the word *arya- was reflected in the ancient Indo-Iranian languages:

In conclusion, I would like to discuss the meaning and the cultural significance of the name Ērān-šahr, which was the official name of the Empire of the Sasanian rulers.

Ērān-šahr basically means ‘the country of the Iranians’ (in contrast to its modern meaning, in MP the word šahr meant ‘country, land’, while the meaning for ‘city’ was reserved to the word šahrestān).

It seems as though the name Ērān-šahr is the creation of the Sasanian mind, for we don’t find any reference to this word in the Old Persian inscriptions of the Achaemenid monarchs.

However, despite that, in the Avestan texts, we find an interesting term for the mythical homeland of the Iranians, that is Airiianǝm vaēǰō (or MP Ērānwēz). Despite being a rather religious and mythological concept, it seems to have played a role in the creation of the idea of Ērān-šahr or the ‘homeland of the Iranians’.

Contents

- 1 Etymology of Iran

- 2 Etymology of Persia

- 3 The two names in the West

- 4 Recent history of the debate

- 5 See also

- 6 Bibliography

- 7 Notes

- 8 References

- 9 External links

In the Western world, Persia (or its cognates) was historically the common name for Iran. In 1935, Reza Shah asked foreign delegates to use the term Iran (the historical name of the country, used by its native people) in formal correspondence. Since then, in the Western World, the use of the word «Iran» has become more common. This also changed the usage of the names for the Iranian nationality, and the common adjective for citizens of Iran changed from Persian to Iranian. In 1959, the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Reza Shah Pahlavi’s son, announced that both «Persia» and «Iran» could officially be used interchangeably.[1] Nonetheless, the word «Iran» has replaced «Persia» in the common usage.

Etymology of Iran

Main article: Iran (word)

The term «Iran» derives immediately from Middle Persian Ērān, Pahlavi ʼyrʼn, first attested in an inscription that accompanies the investiture relief of the first Sassanid king Ardashir I at Naqsh-e Rustam.[2] In this inscription, the king’s Middle Persian appellation is ardašīr šāhān šāh ērān while in the Parthian language inscription that accompanies the Middle Persian one the king is titled ardašīr šāhān šāh aryān (Pahlavi: … ʼryʼn) both meaning king of kings of Iranians.

The gentilic ēr- and ary- in ērān/aryān derives from Old Iranian *arya-[2] (Old Persian ariya-, Avestan airiia-, etc.), meaning «Aryan,»[2] in the sense of «of the Iranians.»[2][3] This term is attested as an ethnic designator in Achaemenid inscriptions and in Zoroastrianism’s Avesta tradition,[4][n 1] and it seems «very likely»[2] that in Ardashir’s inscription ērān still retained this meaning, denoting the people rather than the empire.

Notwithstanding this inscriptional use of ērān to refer to the Iranian peoples, the use of ērān to refer to the empire (and the antonymic anērān to refer to the Roman territories) is also attested by the early Sassanid period. Both ērān and anērān appear in 3rd century calendrical text written by Mani. In an inscription of Ardashir’s son and immediate successor, Shapur I «apparently includes in Ērān regions such as Armenia and the Caucasus which were not inhabited predominantly by Iranians.»[5] In Kartir’s inscriptions (written thirty years after Shapur’s), the high priest includes the same regions (together with Georgia, Albania, Syria and the Pontus) in his list of provinces of the antonymic Anērān.[5] Ērān also features in the names of the towns founded by Sassanid dynasts, for instance in Ērān-xwarrah-šābuhr «Glory of Ērān (of) Shapur». It also appears in the titles of government officers, such as in Ērān-āmārgar «Accountant-General (of) Ērān» or Ērān-dibirbed «Chief Scribe (of) Ērān».[2]

Etymology of Persia

Further information: Persis

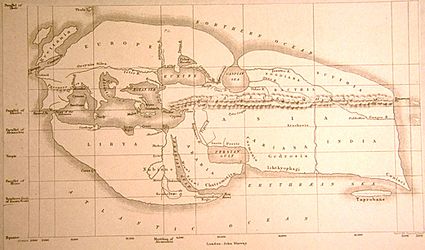

Modern reconstruction of the ancient world map of Eratosthenes from c. 200 BC, using the names Ariana and Persis

The Greeks (who tended earlier to use names related to «Median») began in the fifth century BC to use adjectives such as Perses, Persica or Persis for Cyrus the Great’s empire (a word meaning «country» being understood).[6] Such words were taken from the Old Persian Pārsa — the name of the people whom Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty first ruled (before he inherited or conquered other Iranian Kingdoms) and of whom he was one. This tribe gave its name to the region where they lived (the modern day province is called Fars/Pars) but the province in ancient times was larger than its current area. In Latin, the name for the whole empire was Persia.

In the later parts of the Bible, where this kingdom is frequently mentioned (Books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah), it is called «Paras» (Hebrew פרס), or sometimes «Paras u Madai» (פרס ומדי) i.e. «Persia and Media».

The two names in the West

Reza Pahlavi requested foreign countries to use the term Iran rather than Persia

The name Persia was the official name of Iran in the Western world before 1935, but the Iranian people inside their country since the time of Zoroaster (probably circa 1000 BC), or even before, have called their country «Aryānām» (the equivalent of «Iran» in the proto-Iranian language) or its equivalents. It is not exactly clear what the Iranian people[7] called their country during the Median (728 BC-559 BC), Achaemenid (550 BC–330 BC) or Parthian (250 BC– 226 CE) empires, but evidently from the time of the Sassanids (226–651 CE) they have called it Iran, meaning «the land of Aryans». In Middle Persian sources, the name «Iran» is used for the pre-Sassanid Iranian empires as well as the Sassanid empire. As an example, the use of the name «Iran» for Achaemenids in the Middle Persian book of Arda Viraf refers to the invasion of Iran by Alexander the Great in 330 BC.[8] The Proto-Iranian term for Iran is reconstructed as *Aryānām (the genitive plural of the word *Arya) and the Avestan equivalent is Airyanem (as in Airyanem Vaejah). The internal preference for «Iran» was noted in some Western reference books (e.g. the Harmsworth Encyclopaedia, circa 1907, entry for Iran: «The name is now the official designation of Persia.») but for international purposes, «Persia» was the norm.

On 21 March 1935, the ruler of the country, Reza Shah Pahlavi, issued a decree asking foreign delegates to use the term «Iran» in formal correspondence.

To avoid confusion between the two neighboring countries Iran and Iraq, which were both involved in WWII and occupied by the Allies, Winston Churchill requested from the Iranian government during the Teheran Conference for the old and distinct name «Persia to be used by the United Nations [i.e., the Allies] for the duration of the common War.» His request was approved immediately by the Iranian Foreign Ministry. The American side, however, continued using «Iran» as it had at the time little involvement in Iraq to cause any such confusion.

In the summer of 1959, following concerns that the «new» name had, as one politician put it, «turned a known into an unknown,» a committee was formed, led by noted scholar Ehsan Yarshater, to consider the issue again. They recommended a reversal of the 1935 decision, and Mohammad Reza Shah approved this. However, the implementation of the proposal was weak, simply allowing «Persia» and «Iran» to be used interchangeably.[1] Nowadays both terms are common; «Persia» mostly in historical and cultural contexts, «Iran» mostly in political contexts.

In recent years most exhibitions of Persian history, culture and art in the world have used the term «Persia» (e.g., «Forgotten Empire; Ancient Persia», British Museum; «7000 Years of Persian Art», Vienna, Berlin; and «Persia; Thirty Centuries of Culture and Art», Amsterdam).[9] In 2006, the largest collection of historical maps of Iran, entitled «Historical Maps of Persia», was published in the Netherlands.[10]

Recent history of the debate

In the 1980s, Professor Ehsan Yarshater (editor of the Encyclopædia Iranica) started to publish articles on this matter (in both English and Persian) in Rahavard Quarterly, Pars Monthly, Iranian Studies Journal, etc. After him, a few Persian scholars and researchers such as Prof. Kazem Abhary, Prof. Jalal Matini and Pejman Akbarzadeh followed the issue. Several times since then, Persian magazines and Web sites have published articles from those who agree or disagree with usage of «Persia» and «Persian» in English.[11]

It is the case in many countries that the country’s native name is different from its international name (see Exonym), but for Persians/Iranians this issue has been very controversial. Main points on this matter:

- Persia is the Western name of the country, and Iranians were calling their country «Iran» for many centuries.

- Persia evokes the old culture and civilization of the country.

- Persia and the name of a province of Iran (viz., «Pars») are from the same root, and may cause confusion.

- The name Persia comes from «Pars» but the meaning shifted to refer to the whole country.

- In Western languages, all famous cultural aspects of Iran have been recorded as «Persian» (e.g., Persian carpet, Persian food, Persian cat, Persian pottery, Persian melon, etc.)[12]

There are many Persians (Iranians) and non-Persians in the West who prefer «Persia» and «Persian» as the English names for the country and nationality, similar to the usage of La Perse/persan in French. According to Hooman Majd, the popularity of the term «Persia» among the Persian diaspora stems from the fact that «‘Persia’ connotes a glorious past they would like to be identified with, while ‘Iran’ … says nothing to the world but Islamic fundamentalism.» [13]

However, the name has presented problems for some Iranian ethnic groups who do not identify themselves as Persian, or whose native language is not Persian.

See also

- Iran (word)

Bibliography

- The History of the Idea of Iran, A. Shapur Shahbazi in Birth of the Persian Empire by V. S. Curtis and S. Stewart, 2005, ISBN 1845110625

Notes

- ^ In the Avesta the airiia- are members of the ethnic group of the Avesta-reciters themselves, in contradistinction to the anairiia-, the «non-Aryas». The word also appears four times in Old Persian: One is in the Behistun inscription, where ariya- is the name of a language or script (DB 4.89). The other three instances occur in Darius I’s inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam (DNa 14-15), in Darius I’s inscription at Susa (DSe 13-14), and in the inscription of Xerxes I at Persepolis (XPh 12-13). In these, the two Achaemenid dynasts describe themselves as pārsa pārsahyā puça ariya ariyaciça «a Persian, son of a Persian, an Ariya, of Ariya origin.» «The phrase with ciça, “origin, descendance,” assures that it [i.e. ariya] is an ethnic name wider in meaning than pārsa and not a simple adjectival epithet.»[4]

References

- ^ a b Yarshater, Ehsan Persia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, Iranian Studies, vol. XXII no. 1 (1989)

- ^ a b c d e f MacKenzie, David Niel (1998). «Ērān, Ērānšahr». Encyclopedia Iranica. 8. Costa Mesa: Mazda. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v8f5/v8f545.html.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger (1987). «Aryans». Encyclopedia Iranica. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 684–687. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v2f7/v2f7a010.html.

- ^ a b Bailey, Harold Walter (1987). «Arya». Encyclopedia Iranica. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 681–683. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v2f7/v2f7a004.html.

- ^ a b Gignoux, Phillipe (1987). «Anērān». Encyclopedia Iranica. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 30–31. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v2f1/v2f1a035.html.

- ^ Liddell and Scott, Lexicon of the Greek Language, Oxford, 1882, p 1205

- ^ But not the rulers and emperors of Iran.

- ^ Arda Viraf (1:4; 1:5; 1:9; 1:10; 1:12; etc.)

- ^ Hermitage (2007-09-20). «»Persia», Hermitage Amsterdam». Hermitage. Hermitage. Archived from the original on 2007-04-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20070428162002/http://www.hermitage.nl/en/content.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-03. «Persian objects at Hermitage»

- ^ Brill (2006-09-20). «General Maps of Persia 1477 — 1925». Brill website. Brill. http://www.brill.nl/m_catalogue_sub6_id23605.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-03. «Iran, or Persia as it was known in the West for most of its long history, has been mapped extensively for centuries but the absence of a good cartobibliography has often deterred scholars of its history and geography from making use of the many detailed maps that were produced. This is now available, prepared by Cyrus Alai who embarked on a lengthy investigation into the old maps of Persia, and visited major map collections and libraries in many countries…»

- ^ Pejman Akbarzadeh (2005-09-20). «A Note on the terms «Iran» and «Persia»». Payvand’s Iran News. NetNative. http://www.payvand.com/news/05/sep/1166.html. Retrieved 2007-05-03. «Serious argument on this matter began in the 1980s, when Professor Ehsan Yarshater (Editor of the Encyclopedia Iranica) started to write several articles on this matter (in both English and Persian) in Rahavard Quarterly, Pars Monthly, Iranian Studies Journal, etc. After him, a few Persian scholars and researchers such as Kazem Abhary (Professor at the South Australian University) followed the issue. Several times since then, Persian magazines and websites have published articles from those who agree or disagree with usage of ‘Persia’ and ‘Persian’ in English…»

- ^ Merriam Webster (2008-01-05). «Persian». MW. MW. http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/Persian. Retrieved 2008-01-05. «Persian Carpet, Cat, melon…»

- ^ Majd, Hooman, The Ayatollah Begs to Differ : The Paradox of Modern Iran, by Hooman Majd, Doubleday, 2008, p.161

External links

- Publication of General Maps of Persia (Iran) in The Netherlands

| v · d · eName of Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition |

|

| Dependencies and other territories |

|

TEHRAN — The word “Iran” has recently been deciphered from an early Islamic-era petroglyph, which was found last year at an ancient fortress in Semirom county, Isfahan province, central Iran.

Although the word “Iran” can easily be traced in pre-Islamic inscriptions and literary and geographical texts as well as manuscripts dating to the first centuries of the Islamic epoch, this is the first time that researchers and archaeologists have been able to find an inscription from the second half of the third century (after the advent of Islam) in which a name from Iran is given, Mehr reported on Tuesday.

“It is also possible that in some inscriptions the name of ‘Iran’ being presented with other terms, but in the inscription discovered from Semirom fortress, the name of Iran is clearly and legibly mentioned. For this reason, this inscription is very important and the discovery and reading of this inscription can be considered a great discovery,” the report added.

The territory which is now modern Iran was formerly known as Persia, a term used for centuries and originated from a region of southern Iran formerly known as Persis, alternatively as Pars or Parsa, modern Fars. The use of the name was gradually extended by the ancient Greeks and other peoples to apply to the whole Iranian plateau. The people of that region have traditionally called their country Iran, “Land of the Aryans.” That name was officially adopted in 1935.

AFM/MG