Asked by: Garrick Donnelly

Score: 4.6/5

(75 votes)

The basic concept of gamification isn’t new, but the word itself is a 21st-century addition to the English lexicon. … In other words, «gamification» is about making something potentially tedious into a game. Gamification is effective because it taps into people’s natural desires for competition and achievement.

Is gamify a real word?

verb (used with object), gam·i·fied, gam·i·fy·ing. to turn (an activity or task) into a game or something resembling a game: Many exercise programs have been gamified, with badges and scores. The company develops gamified apps.

When did gamification become a word?

The term ‘Gamification’ was coined back in 2002 by Nick Pelling, a British-born computer programmer and inventor, and hit the mainstream thanks to Foursquare in 2009. By 2011, it officially became a buzzword when Gartner added it to its ‘Hype Cycle’ list. Now, in 2015, Gamification is hotter than ever.

What is another word for gamification?

Educational games, infotainment, and serious games are all similar (or proposed replacement) terms for gamified learning or training.

What is the exact meaning of gamification?

Gamification describes the incorporation of game-style incentives into everyday or non-game activities. Any time game-like features or aspects of game design are introduced to non-game contexts, gamification is taking place.

36 related questions found

Is kahoot a gamification?

One of the most employed gamification tools is Kahoot!, a free tool that has gained popularity among teachers for its simple use and its ability to establish active work dynamics in the classroom. Kahoot! allows teachers to create surveys, questionnaires and discussions, obtaining feedback from students in real time.

How do you gamify elearning?

To use gamification in elearning, it’s best practice to incorporate elements such as:

- Stories. Create a compelling storyline to captivate your users and take them on a journey. …

- Visual design. …

- Competitions. …

- Challenges. …

- Rewards. …

- Feedback. …

- 1.Encourages active learning. …

- Promotes continuous learning.

What is educational gamification?

Gamification of education is a developing approach for increasing learners’ motivation and engagement by incorporating game design elements in educational environments. … The idea of incentivizing people is not new but the term “gamification” didn’t enter the mainstream vocabulary until 2010.

What is a synonym for mummification?

In this page you can discover 12 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions, and related words for mummify, like: embalm, wither, shrivel, unburied, dry, dry up, mortify, preserve, sear, wizen and disinter.

Who first coined the term gamification?

The term gamification was coined by Nick Pelling in 2002.

Why does gamification exist?

Gamification techniques are intended to leverage people’s natural desires for socializing, learning, mastery, competition, achievement, status, self-expression, altruism, or closure, or simply their response to the framing of a situation as game or play.

Where can gamification be used?

Whilst typical game elements are by no means new, they have indeed become increasingly common in non-game contexts such as websites, digital marketing, enterprise applications and even virtual to-do lists and productivity tools. One huge area where gamification is highly prevalent, however, is in education.

What is recruitment gamification?

Gamification is the strategic attempt to recreate job-like experiences and scenarios in the form of a gameplay environment to motivate and engage users. Users often compete and ultimately those who perform best are likely to be hired.

What is a Baxter?

Baxternoun. a baker; originally, a female baker.

What gamification is and what it’s not?

Gamification is not about making your intervention a game. Successful game mechanics in the context of a formalized learning intervention is about making the learner’s real-world context more engaging, realistic and immersive.

What was the ancient capital of Egypt?

Memphis, city and capital of ancient Egypt and an important centre during much of Egyptian history. Memphis is located south of the Nile River delta, on the west bank of the river, and about 15 miles (24 km) south of modern Cairo.

Do we still preserve deceased person what is it called and how does it differ with mummification?

Mummification is the process of preserving the body after death by deliberately drying or embalming flesh. … Mummies are also created by unintentional or accidental processes, which is known as «natural» mummification.

What are Egypt mummies?

What are mummies? A mummy is the body of a person (or an animal) that has been preserved after death. Who were the mummies? They were any Egyptian who could afford to pay for the expensive process of preserving their bodies for the afterlife.

Is gamification a pedagogy?

Using gamification as pedagogy requires using a spiral curriculum for students to learn advanced tasks by starting with basic skills, setting clear short-term and long-term goals, rewarding students when they achieve each level, forming a learning community with a showcase for student work, and providing a safety net …

What is a narrative in gamification?

Being human implies that stories are a way of generating meaning. Stories are important to basic human thinking and the process of making sense of the world. … Narratives can be used for gamification – brining in engagment, meaning and clear calls to action, showing employees how to get on a path to mastery.

Is gamification a technology or a task?

Below are 3 ways to gamify your classroom with and without tech. But first, what is gamification? Well, it’s the use of game mechanics, such as high scores, badges, levels, tasks, and rewards to help people focus on tasks and activities that are not in themselves ‘games’.

Is gamification still relevant?

19 Gamification Trends for 2021-2025: Top Stats, Facts & Examples. Gamification is no longer a buzzword. Since the term was first coined in 2003, it has continued to grow in prominence. … In fact, 85% of employees are shown to be more engaged when gamification solutions are applied to their workplace.

How do you incorporate gamification?

Tips On How To Incorporate Gamification Into Mobile Learning

- Outline The Project’s Structure And Time Frame. …

- Choose Some Game Components. …

- Untether Your Learners From The Classroom. …

- Design With Self-Directed Learning In Mind. …

- Utilize Feedback, Rewards, And Prizes. …

- Report On Outcomes From Game-Based Learning.

What is a gamification app?

for their marketing strategies. In other words, a gamification app is an app that uses gaming features to engage users.

Is Kahoot unfair?

First, Kahoot isn’t equitable practice. Learners demonstrate their knowledge in different ways. … Further, the multiple choice nature of Kahoot is unfair. Any educator knows the painstaking process of making a “fair” multiple choice question.

«Gamify» redirects here. For the Australian Children’s TV series, see Gamify (TV series).

Gamification is the strategic attempt to enhance systems, services, organizations, and activities by creating similar experiences to those experienced when playing games in order to motivate and engage users.[1] This is generally accomplished through the application of game-design elements and game principles (dynamics and mechanics) in non-game contexts.[2][3]

Gamification is part of persuasive system design, and it commonly employs game design elements[4][2][5][6][3] to improve user engagement,[7][8][9] organizational productivity,[10] flow,[11][12][13] learning,[14][15] crowdsourcing,[16] knowledge retention,[17] employee recruitment and evaluation, ease of use, usefulness of systems,[13][18][19] physical exercise,[20] traffic violations,[21] voter apathy,[22][23] public attitudes about alternative energy,[24] and more. A collection of research on gamification shows that a majority of studies on gamification find it has positive effects on individuals.[5] However, individual and contextual differences exist.[25]

Techniques[edit]

Gamification techniques are intended to leverage people’s natural desires for socializing, learning, mastery, competition, achievement, status, self-expression, altruism, or closure, or simply their response to the framing of a situation as game or play.[26] Early gamification strategies use rewards for players who accomplish desired tasks or competition to engage players. Types of rewards include points,[27] achievement badges or levels,[28] the filling of a progress bar,[29] or providing the user with virtual currency.[28] Making the rewards for accomplishing tasks visible to other players or providing leader boards are ways of encouraging players to compete.[30]

Another approach to gamification is to make existing tasks feel more like games.[31] Some techniques used in this approach include adding meaningful choice, onboarding with a tutorial, increasing challenge,[32] and adding narrative.[31]

Game design elements[edit]

Game design elements are the basic building blocks of gamification applications.[33][34] Among these typical game design elements, are points, badges, leader-boards, performance graphs, meaningful stories, avatars, and teammates.[35]

Points[edit]

Points are basic elements of a multitude of games and gamified applications.[36] They are typically rewarded for the successful accomplishment of specified activities within the gamified environment[37] and they serve to numerically represent a player’s progress.[38] Various kinds of points can be differentiated between, e.g. experience points, redeemable points, or reputation points, as can the different purposes that points serve.[10] One of the most important purposes of points is to provide feedback. Points allow the players’ in-game behavior to be measured, and they serve as continuous and immediate feedback and as a reward.[39]

Badges[edit]

Badges are defined as visual representations of achievements[37] and can be earned and collected within the gamification environment. They confirm the players’ achievements, symbolize their merits,[40] and visibly show their accomplishment of levels or goals.[41] Earning a badge can be dependent on a specific number of points or on particular activities within the game.[37] Badges have many functions, serving as goals, if the prerequisites for winning them are known to the player, or as virtual status symbols.[37] In the same way as points, badges also provide feedback, in that they indicate how the players have performed.[42] Badges can influence players’ behavior, leading them to select certain routes and challenges in order to earn badges that are associated with them.[43] Additionally, as badges symbolize one’s membership in a group of those who own this particular badge, they also can exert social influences on players and co-players,[40] particularly if they are rare or hard to earn.

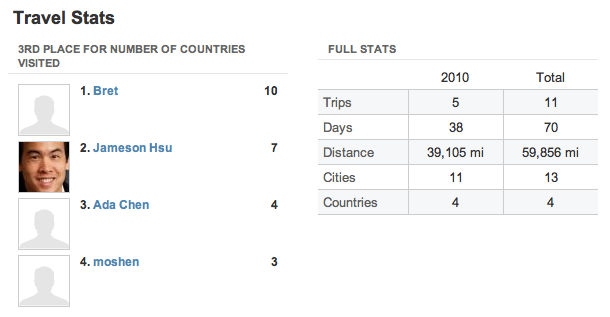

Leaderboards[edit]

Leaderboards rank players according to their relative success, measuring them against a certain success criterion.[44] As such, leaderboards can help determine who performs best in a certain activity[45] and are thus competitive indicators of progress that relate the player’s own performance to the performance of others. However, the motivational potential of leaderboards is mixed. Werbach and Hunter[37] regard them as effective motivators if there are only a few points left to the next level or position, but as demotivators, if players find themselves at the bottom end of the leaderboard. Competition caused by leaderboards can create social pressure to increase the player’s level of engagement and can consequently have a constructive effect on participation and learning.[46] However, these positive effects of competition are more likely if the respective competitors are approximately at the same performance level.[47][48]

Performance graphs[edit]

Performance graphs, which are often used in simulation or strategy games, provide information about the players’ performance compared to their preceding performance during a game.[35] Thus, in contrast to leaderboards, performance graphs do not compare the player’s performance to other players, but instead, evaluate the player’s own performance over time. Unlike the social reference standard of leaderboards, performance graphs are based on an individual reference standard. By graphically displaying the player’s performance over a fixed period, they focus on improvements. Motivation theory postulates that this fosters mastery orientation, which is particularly beneficial to learning.[35]

Meaningful stories[edit]

Meaningful stories are game design elements that do not relate to the player’s performance. The narrative context in which a gamified application can be embedded contextualizes activities and characters in the game and gives them meaning beyond the mere quest for points and achievements.[49] A story can be communicated by a game’s title (e.g., Space Invaders) or by complex storylines typical of contemporary role-playing video games (e.g., The Elder Scrolls Series).[49] Narrative contexts can be oriented towards real, non-game contexts or act as analogies of real-world settings. The latter can enrich boring, barely stimulating contexts, and, consequently, inspire and motivate players particularly if the story is in line with their personal interests.[50] As such, stories are also an important part in gamification applications, as they can alter the meaning of real-world activities by adding a narrative ‘overlay’, e.g. being hunted by zombies while going for a run.

Avatars[edit]

Avatars are visual representations of players within the game or gamification environment.[37] Usually, they are chosen or even created by the player.[49] Avatars can be designed quite simply as a mere pictogram, or they can be complexly animated, three- dimensional representations. Their main formal requirement is that they unmistakably identify the players and set them apart from other human or computer-controlled avatars.[37] Avatars allow the players to adopt or create another identity and, in cooperative games, to become part of a community.[51]

Teammates[edit]

Teammates, whether they are other real players or virtual non-player characters, can induce conflict, competition or cooperation.[49] The latter can be fostered particularly by introducing teams, i.e. by creating defined groups of players that work together towards a shared objective.[37] Meta-analytic evidence supports that the combination of competition and collaboration in games is likely to be effective for learning.[52]

The Game Element Hierarchy[edit]

The described game elements fit within a broader framework, which involves three types of elements: Dynamics, Mechanics, and Components. These elements constitute The Game Element Hierarchy.[53]

Dynamics are the highest in the hierarchy. They are the big picture aspects of the gamified system that should be considered and managed; however, they never directly enter into the game. Dynamics elements provide motivation through features such as narrative or social interaction.

Mechanics are the basic processes that drive the action forward and generate player engagement and involvement. Examples are chance, turns, and rewards.

Components are the specific instantiations of mechanics and dynamics; elements like points, quests, and virtual goods.[37]

Applications[edit]

Gamification has been applied to almost every aspect of life. Examples of gamification in business context include the U.S. Army, which uses military simulator America’s Army as a recruitment tool, and M&M’s «Eye Spy» pretzel game, launched in 2013 to amplify the company’s pretzel marketing campaign by creating a fun way to «boost user engagement.» Another example can be seen in the American education system. Students are ranked in their class based on their earned grade-point average (GPA), which is comparable to earning a high score in video games.[54] Students may also receive incentives, such as an honorable mention on the dean’s list, the honor roll, and scholarships, which are equivalent to leveling-up a video game character or earning virtual currency or tools that augment game success.

Job application processes sometimes use gamification as a way to hire employees by assessing their suitability through questionnaires and mini games that simulate the actual work environment of that company.

Marketing[edit]

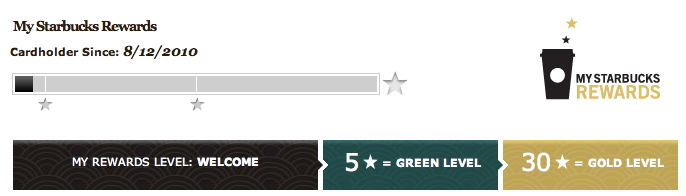

Gamification has been widely applied in marketing. Over 70% of Forbes Global 2000 companies surveyed in 2013 said they planned to use gamification for the purposes of marketing and customer retention.[55] For example, in November, 2011, Australian broadcast and online media partnership Yahoo!7 launched its Fango mobile app/SAP, which TV viewers use to interact with shows via techniques like check-ins and badges. Gamification has also been used in customer loyalty programs. In 2010, Starbucks gave custom Foursquare badges to people who checked in at multiple locations, and offered discounts to people who checked in most frequently at an individual store.[56] As a general rule Gamification Marketing or Game Marketing usually falls under four primary categories;

1. Brandification (in-game advertising): Messages, images or videos promoting a Brand, Product or Service within a game’s visuals components. According to NBCNews game creators Electronic Arts used «Madden 09» and «Burnout Paradise» to promote ‘in-game’ billboards encouraging players to vote.[57]

2. Transmedia: The result of taking a media property and extending it into a different medium for both promotional and monetisation purposes. Nintendo’s «007: GoldenEye» is a classic example. A video game created to advertise the originally titled movie. In the end, the promotional game brought in more money than the originally titled film.

3. Through-the-line (TTL) & Below-the-line (BTL): Text above, side or below main game screen (also known as an iFrame) advertising images or text. Example of this would be «I love Bees».

4. Advergames: Usually games based on popular mobile game templates, such as ‘Candy Crush’ or ‘Temple Run’. These games are then recreated via platforms like WIX with software from the likes of Gamify, in order to promote Brands, Products and Services. Usually to encourage engagement, loyalty and product education. These usually involve social leaderboards and rewards that are advertised via social media platforms like Facebook’s Top 10 games.[58]

Gamification also has been used as a tool for customer engagement,[59] and for encouraging desirable website usage behaviour.[29] Additionally, gamification is applicable to increasing engagement on sites built on social network services. For example, in August, 2010, the website builder DevHub announced an increase in the number of users who completed their online tasks from 10% to 80% after adding gamification elements.[60] On the programming question-and-answer site Stack Overflow users receive points and/or badges for performing a variety of actions, including spreading links to questions and answers via Facebook and Twitter. A large number of different badges are available, and when a user’s reputation points exceed various thresholds, the user gains additional privileges, eventually including moderator privileges.

Inspiration[edit]

Gamification can be used for ideation (structured brainstorming to produce new ideas). A study at MIT Sloan found that ideation games helped participants generate more and better ideas, and compared it to gauging the influence of academic papers by the numbers of citations received in subsequent research.[61]

Health[edit]

Applications like Fitocracy and QUENTIQ (Dacadoo) use gamification to encourage their users to exercise more effectively and improve their overall health. Users are awarded varying numbers of points for activities they perform in their workouts, and gain levels based on points collected. Users can also complete quests (sets of related activities) and gain achievement badges for fitness milestones.[62] Health Month adds aspects of social gaming by allowing successful users to restore points to users who have failed to meet certain goals. Public health researchers have studied the use of gamification in self-management of chronic diseases and common mental disorders,[63][64] STD prevention,[65][66] and infection prevention and control.[67]

In a review of health apps in the 2014 Apple App Store, more than 100 apps showed a positive correlation between gamification elements used and high user ratings. MyFitnessPal was named as the app that used the most gamification elements.[68]

Reviewers of the popular location-based game Pokémon Go praised the game for promoting physical exercise. Terri Schwartz (IGN) said it was «secretly the best exercise app out there,» and that it changed her daily walking routine.[69] Patrick Allen (Lifehacker) wrote an article with tips about how to work out using Pokémon Go.[70] Julia Belluz (Vox) said it could be the «greatest unintentional health fad ever,» writing that one of the results of the game that the developers may not have imagined was that «it seems to be getting people moving.»[71] One study showed users took an extra 194 steps per day once they started using the app, approximately 26% more than usual.[72] Ingress is a similar game that also requires a player to be physically active. Zombies, Run!, a game in which the player is trying to survive a zombie apocalypse through a series of missions, requires the player to (physically) run, collect items to help the town survive, and listen to various audio narrations to uncover mysteries. Mobile, context-sensitive serious games for sports and health have been called exergames.[73]

Work[edit]

Gamification has been used in an attempt to improve employee productivity in healthcare, financial services, transportation, government,[74][75] and others.[76] In general, enterprise gamification refers to work situations where «game thinking and game-based tools are used in a strategic manner to integrate with existing business processes or information systems. And these techniques are used to help drive positive employee and organizational outcomes.»[9]

Crowdsourcing[edit]

Crowdsourcing has been gamified in games like Foldit, a game designed by the University of Washington, in which players compete to manipulate proteins into more efficient structures. A 2010 paper in science journal Nature credited Foldit’s 57,000 players with providing useful results that matched or outperformed algorithmically computed solutions.[77] The ESP Game is a game that is used to generate image metadata. Google Image Labeler is a version of the ESP Game that Google has licensed to generate its own image metadata.[78] Research from the University of Bonn used gamification to increase wiki contributions by 62%.[79]

In the context of online crowdsourcing, gamification is also employed to improve the psychological and behavioral consequences of the solvers.[80] According to numerous research, adding gamification components to a crowdsourcing platform can be considered as a design that shifts participants’ focus from task completion to involvement motivated by intrinsic factors.[81][82] Since the success of crowdsourcing competitions depends on a large number of participating solvers, the platforms for crowdsourcing provide motivating factors to increase participation by drawing on the concepts of the game.[83]

Education and training[edit]

Gamification in the context of education and training is of particular interest because it offers a variety of benefits associated with learning outcomes and retention.[84][85][86][87] Using video-game inspired elements like leaderboards and badges has been shown to be effective in engaging large groups and providing objectives for students to achieve outside of traditional norms like grades or verbal feedback. Online learning platforms such as Khan Academy and even physical schools like New York City Department of Education’s Quest to Learn use gamification to motivate students to complete mission-based units and master concepts.[88][89] There is also an increasing interest in the use of gamification in health sciences and education as an engaging information delivery tool and in order to add variety to revision.[90][91][92]

With increased access to one-to-one student devices, and accelerated by pressure from the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers from primary to post-secondary settings have introduced live, online quiz-show style games into their lessons.[93]

Gamification has also been used to promote learning outside of schools. In August 2009, Gbanga launched a game for the Zurich Zoo where participants learned about endangered species by collecting animals in mixed reality. Companies seeking to train their customers to use their product effectively can showcase features of their products with interactive games like Microsoft’s Ribbon Hero 2.[94][95]

A wide range of employers including the United States Armed Forces, Unilever, and SAP currently use gamified training modules to educate their employees and motivate them to apply what they learned in trainings to their job.[75][96][97] According to a study conducted by Badgeville, 78% of workers are utilizing games-based motivation at work and nearly 91% say these systems improve their work experience by increasing engagement, awareness and productivity.[98] In the form of occupational safety training, technology can provide realistic and effective simulations of real-life experiences, making safety training less passive and more engaging, more flexible in terms of time management and a cost-effective alternative to practice.[99][100][101][102]

Politics and terrorist groups[edit]

Alix Levine, an American security consultant, reports that some techniques that a number of extremist websites such as Stormfront and various terrorism-related sites used to build loyalty and participation can be described as gamification. As an example, Levine mentioned reputation scores.[103][104]

The Chinese government has announced that it will begin using gamification to rate its citizens in 2020, implementing a Social Credit System in which citizens will earn points representing trustworthiness. Details of this project are still vague, but it has been reported that citizens will receive points for good behavior, such as making payments on time and educational attainments.[105]

Bellingcat contributor Robert Evans has written about the «gamification of terror» in the wake of the El Paso shooting, in an analysis of the role 8Chan and similar boards played in inspiring the massacre, as well as other acts of terrorism and mass shootings.[106] According to Evans, «[w]hat we see here is evidence of the only real innovation 8chan has brought to global terrorism: the gamification of mass violence. We see this not just in the references to “high scores”, but in the very way the Christchurch shooting was carried out. Brenton Tarrant livestreamed his massacre from a helmet cam in a way that made the shooting look almost exactly like a First Person Shooter video game. This was a conscious choice, as was his decision to pick a sound-track for the spree that would entertain and inspire his viewers.»[106]

Technology design[edit]

Traditionally, researchers thought of motivations to use computer systems to be primarily driven by extrinsic purposes; however, many modern systems have their use driven primarily by intrinsic motivations.[107] Examples of such systems used primarily to fulfill users’ intrinsic motivations, include online gaming, virtual worlds, online shopping, learning/education, online dating, digital music repositories, social networking, online pornography, and so on. Such systems are excellent candidates for further ‘gamification’ in their design. Moreover, even traditional management information systems (e.g., ERP, CRM) are being ‘gamified’ such that both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations must increasingly be considered.

As illustration, Microsoft has announced plans to use gamification techniques for its Windows Phone 7 operating system design.[108] While businesses face the challenges of creating motivating gameplay strategies, what makes for effective gamification[109] is a key question.

One important type of technological design in gamification is the player centered design. Based on the design methodology user-centered design, its main goal is to promote greater connectivity and positive behavior change between technological consumers. It has five steps that help computer users connect with other people online to help them accomplish goals and other tasks they need to complete. The 5 steps are: an individual or company has to know their player (their target audience), identify their mission (their goal), understand human motivation (the personality, desires, and triggers of the target audience), apply mechanics (points, badges, leaderboards, etc.), and to manage, monitor, and measure the way they are using their mechanics to ensure it is helping them achieve the desired outcome of their goal and that their goal is specific and realistic.[110]

Authentication[edit]

Gamification has also been applied to authentication. For example, the possibilities of using a game like Guitar Hero can help someone learn a password implicitly.[111][clarification needed] Furthermore, games have been explored as a way to learn new and complicated passwords. It is suggested that these games could be used to «level up» a password, thereby improving its strength over time.[112] Gamification has also been proposed as a way to select and manage archives.[113] In 2013 Australian technology company Wynbox recorded success in the application of its gamification engine to the hotel booking process.[114]

Online gambling[edit]

Gamification has been used to some extent by online casinos. Some brands use an incremental reward system to extend the typical player lifecycle and to encourage repeat visits and cash deposits at the casino in return for rewards such as free spins and cash match bonuses on subsequent deposits.[115]

History[edit]

The term «gamification» first appeared online in the context of computer software in 2008.[116][a] Gamification did not gain popularity until 2010.[120][121] Even prior to the term coming into use, other fields borrowing elements from videogames was common; for example, some work in learning disabilities[122] and scientific visualization adapted elements from videogames.[123]

The term «gamification» first gained widespread usage in 2010, in a more specific sense referring to incorporation of social/reward aspects of games into software.[124] The technique captured the attention of venture capitalists, one of whom said he considered gamification the most promising area in gaming.[125] Another observed that half of all companies seeking funding for consumer software applications mentioned game design in their presentations.[29]

Several researchers consider gamification closely related to earlier work on adapting game-design elements and techniques to non-game contexts. Deterding et al.[2] survey research in human–computer interaction that uses game-derived elements for motivation and interface design, and Nelson[126] argues for a connection to both the Soviet concept of socialist competition, and the American management trend of «fun at work». Fuchs[127] points out that gamification might be driven by new forms of ludic interfaces. Gamification conferences have also retroactively incorporated simulation; e.g. Will Wright, designer of the 1989 video game SimCity, was the keynote speaker at the gamification conference Gsummit 2013.[128]

In addition to companies that use the technique, a number of businesses created gamification platforms. In October 2007, Bunchball,[129] backed by Adobe Systems Incorporated,[130] was the first company to provide game mechanics as a service,[131] on Dunder Mifflin Infinity, the community site for the NBC TV show The Office. Bunchball customers have included Playboy, Chiquita, Bravo, and The USA Network.[132] Badgeville, which offers gamification services, launched in late 2010, and raised $15 million in venture-capital funding in its first year of operation.[133]

Gamification as an educational and behavior modification tool reached the public sector by 2012, when the United States Department of Energy co-funded multiple research trials,[134] including consumer behavior studies,[135] adapting the format of Programmed learning into mobile microlearning to experiment with the impacts of gamification in reducing energy use.[136] Cultural anthropologist Susan Mazur-Stommen published a business case for applying games to addressing climate change and sustainability, delivering research which «…took many forms including card-games (Cool Choices), videogames (Ludwig), and games for mobile devices such as smartphones (Ringorang) [p.9].»[137]

Gamification 2013, an event exploring the future of gamification, was held at the University of Waterloo Stratford Campus in October 2013.[138]

Legal restrictions[edit]

Through gamification’s growing adoption and its nature as a data aggregator, multiple legal restrictions may apply to gamification. Some refer to the use of virtual currencies and virtual assets, data privacy laws and data protection, or labor laws.[139]

The use of virtual currencies, in contrast to traditional payment systems, is not regulated. The legal uncertainty surrounding the virtual currency schemes might constitute a challenge for public authorities, as these schemes can be used by criminals, fraudsters and money launderers to perform their illegal activities.[140]

A March 2022 consultation paper by the Board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) questions whether some gamification tactics should be banned.[141]

Criticism[edit]

University of Hamburg researcher Sebastian Deterding has characterized the initial popular strategies for gamification as not being fun and creating an artificial sense of achievement. He also says that gamification can encourage unintended behaviours.[142]

Poorly designed gamification in the workplace has been compared to Taylorism, and is considered a form of micromanagement.[143]

In a review of 132 of the top health and fitness apps in the Apple app store, in 2014, using gamification as a method to modify behavior, the authors concluded that «Despite the inclusion of at least some components of gamification, the mean scores of integration of gamification components were still below 50 percent. This was also true for the inclusion of game elements and the use of health behavior theory constructs, thus showing a lack of following any clear industry standard of effective gaming, gamification, or behavioral theory in health and fitness apps.»[68]

Concern was also expressed in a 2016 study analyzing outcome data from 1,298 users who competed in gamified and incentivized exercise challenges while wearing wearable devices. In that study the authors conjectured that data may be highly skewed by cohorts of already healthy users, rather than the intended audiences of participants requiring behavioral intervention.[144]

Game designers like Jon Radoff and Margaret Robertson have also criticized gamification as excluding elements like storytelling and experiences and using simple reward systems in place of true game mechanics.[145][146]

Gamification practitioners[147][148] have pointed out that while the initial popular designs were in fact mostly relying on simplistic reward approach, even those led to significant improvements in short-term engagement.[149] This was supported by the first comprehensive study in 2014, which concluded that an increase in gamification elements correlated with an increase in motivation score, but not with capacity or opportunity/trigger scores.[68][150]

The same study called for standardization across the app industry on gamification principles to improve the effectiveness of health apps on the health outcomes of users.[68]

MIT Professor Kevin Slavin has described business research into gamification as flawed and misleading for those unfamiliar with gaming.[151] Heather Chaplin, writing in Slate, describes gamification as «an allegedly populist idea that actually benefits corporate interests over those of ordinary people».[152] Jane McGonigal has distanced her work from the label «gamification», listing rewards outside of gameplay as the central idea of gamification and distinguishing game applications where the gameplay itself is the reward under the term «gameful design».[153]

«Gamification» as a term has also been criticized. Ian Bogost has referred to the term as a marketing fad and suggested «exploitation-ware» as a more suitable name for the games used in marketing.[154] Other opinions on the terminology criticism have made the case why the term gamification makes sense.[155]

In an article in the LA Times, the gamification of worker engagement at Disneyland was described as an «electronic whip».[156] Workers had reported feelings similar to slavery behaviors and whipping sense.

See also[edit]

- Egoboo, a component of some gamification strategies

Notes[edit]

- ^ In 2011 British-born videogame developer Nick Pelling self-proclaimed[117] to have coined the term in 2002 as part of his startup Conundra Ltd.[118][119] for the field of consumer electronics, and many books and scholarly articles subsequently cite this as the likely genesis of the term.

References[edit]

- ^ Hamari, J. (2019). Gamification. Blackwell Pub, In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, Malden. pp. 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeos1321 Archived 2022-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Sebastian Deterding; Dan Dixon; Rilla Khaled; Lennart Nacke (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining «gamification». Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference. pp. 9–15. doi:10.1145/2181037.2181040.

- ^ a b Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J., McCarthy, I. & Pitt, L. (2015). «Is it all a game? Understanding the principles of gamification». Business Horizons. 58 (4): 411–420. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2015.03.006. S2CID 19170739.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2012). «Defining Gamification – A Service Marketing Perspective». Proceedings of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference 2012, Tampere, Finland, October 3–5. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Hamari, Juho; Koivisto, Jonna; Sarsa, Harri (2014). «Does Gamification Work? – A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification». Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA, January 6–9: 3025–3034. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2014.377. ISBN 978-1-4799-2504-9. S2CID 8115805. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ^ «Gamification Design Elements». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ^ Hamari, Juho (2013). «Transforming Homo Economicus into Homo Ludens: A Field Experiment on Gamification in a Utilitarian Peer-To-Peer Trading Service». Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 12 (4): 236–245. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2013.01.004. Archived from the original on 2014-04-06. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- ^ Hamari, Juho (2015). «Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification». Computers in Human Behavior. 71: 469–478. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.036. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ^ a b Ruhi, Umar (2015-01-01). «Level Up Your Strategy: Towards a Descriptive Framework for Meaningful Enterprise Gamification». Technology Innovation Management Review. 5 (8): 5–16. arXiv:1605.09678. Bibcode:2016arXiv160509678R. doi:10.22215/timreview/918. ISSN 1927-0321. S2CID 4643782.

- ^ a b Zichermann, Gabe; Cunningham, Christopher (August 2011). «Introduction». Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps (1st ed.). Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media. p. xiv. ISBN 978-1-4493-1539-9. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ^ Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2014). «Measuring Flow in Gamification: Dispositional Flow Scale-2». Computers in Human Behavior. 40: 133–134. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.048. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-10-27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Procci, K.; Singer, A. R.; Levy, K. R.; Bowers, C. (2012). «Measuring the flow experience of gamers: An evaluation of the DFS-2». Computers in Human Behavior. 28 (6): 2306–2312. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.039.

- ^ a b Philipp Herzig; Susanne Strahringer; Michael Ameling (2012). Gamification of ERP Systems-Exploring Gamification Effects on User Acceptance Constructs (PDF). Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik 2012 (MKWI’12). pp. 793–804. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ^ Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller. B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2014). «Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning». Computers in Human Behavior. 54: 133–134. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.045. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Herger, Mario (July 17, 2014). «Gamification Facts & Figures». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Morschheuser, Benedikt; Hamari, Juho; Koivisto, Jonna (2016). «Gamification in crowdsourcing: A review». Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA, January 5–8: 4375–4384. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2016.543. ISBN 978-0-7695-5670-3. S2CID 29654897. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ^ Dincelli, Ersin; Chengalur-Smith, InduShobha (2020). «Choose your own training adventure: Designing a gamified SETA artefact for improving information security and privacy through interactive storytelling». European Journal of Information Systems. 29 (6): 669–687. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2020.1797546.

- ^ Hamari, Juho; Koivisto, Jonna (2015). «Why do people use gamification services?». International Journal of Information Management. 35 (4): 419–431. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.04.006. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ^ Philipp Herzig (2014). Gamification as a Service (Ph.D.). Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ^ Hamari, Juho; Koivisto, Jonna (2015). ««Working out for likes»: An empirical study on social influence in exercise gamification». Computers in Human Behavior. 50: 333–347. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.018. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ^ «The Speed Camera Lottery». TheFunTheory. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ^ Furbert, Tinee (July 4, 2017). «Senator Furbert Educates Voters With Social App». BerNews Bermuda. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ «Rethinking Elections With Gamification». HuffingtonPost. Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ^ Beck, Ariane; Rai, Varun (2016). «Serious Games in Breaking Informational Barriers in Solar Energy». SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2816852. S2CID 156194157. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ Koivisto, Jonna; Hamari, Juho (2015). «Demographic differences in perceived benefits from gamification». Computers in Human Behavior. 35: 179–188. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.007. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ^ Lieberoth, A (2015). «Shallow Gamification, Testing Psychological Effects of Framing an Activity as a Game». Games and Culture. 10 (3): 229–248. doi:10.1177/1555412014559978. S2CID 147266246.

- ^ Sutter, John D. (September 30, 2010). «Browse the Web, earn points and prizes». CNN. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Hamari, Juho; Eranti, Veikko (2011). «Framework for Designing and Evaluating Game Achievements» (PDF). Proceedings of Digra 2011 Conference: Think Design Play, Hilversum, Netherlands, September: 14–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ a b c O’Brien, Chris (October 24, 2010). «Get ready for the decade of gamification». San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on April 23, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Byron Reeves; J. Leighton Read (2009). Total Engagement: Using Games and Virtual Worlds to Change the Way People Work and Businesses Compete. Harvard Business Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-4221-4657-6.

- ^ a b Deterding, Sebastian (28 September 2010). «Just Add Points? What UX Can (and Cannot) Learn From Games». UX Camp Europe. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2013.Joel Falconer (2011-05-12). «UserInfuser: open source gamification platform». The Next Web. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ^ Jane McGonigal Read (2011). Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change The World. Penguin Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-59420-285-8.

- ^ Costa, C. J. (2019). Gamification. OAE – Organizational Architect and Engineer Journal. https://doi.org/10.21428/b3658bca.8ffccebf Archived 2022-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining «Gamification». Paper presented at the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference, Tampere. https://dx.doi.org/10.1145/ 2181037.2181040.

- ^ a b c Sailer, Michael; Hense, Jan Ulrich; Mayr, Sarah Katharina; Mandl, Heinz (2017-04-01). «How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction». Computers in Human Behavior. 69: 371–380. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033. ISSN 0747-5632.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by Design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2015). The gamification toolkit — dynamics, mechanics, and components for the win. Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press.

- ^ Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2012). For the Win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business. Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press.

- ^ Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, H., & Klevers, M. (2013). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal, 19, 28e37.

- ^ a b Anderson, Ashton; Huttenlocher, Daniel; Kleinberg, Jon; Leskovec, Jure (2013). «Steering user behavior with badges» (PDF). Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web — WWW ’13. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: ACM Press: 95–106. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.402.2444. doi:10.1145/2488388.2488398. ISBN 9781450320351. S2CID 1211869. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-16. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ Antin, J., & Churchill, E. F. (2011). Badges in social media: A social psychological perspective. Paper presented at the CHI 2011, Vancouver.

- ^ Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Glued to games: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound. Santa barbara: Praeger.

- ^ Wang, H., & Sun, C.-T. (2011). Game reward systems: gaming experiences and social meanings. Paper presented at the DiGRA 2011 conference: Think Design Play, Hilversum.

- ^ Costa, J. P., Wehbe, R. R., Robb, J., & Nacke, L. E. (2013). Time’s Up: Studying Leadboards For Engaging Punctual Behaviour. Paper presented at the Gamification 2013: 1st International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications, Stratfort. doi:10.1145/2583008.2583012

- ^ Crumlish, C., & Malone, E. (2009). Designing social interfaces: Principles, patterns, and practices for improving the user experience. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- ^ Burguillo, J. C. (2010). «Using game theory and Competition-based Learning to stimulate student motivation and performance». Computers & Education. 55 (2): 566–575. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.018.

- ^ Landers, R. N., & Landers, A. K. (2014). An Empirical Test of the Theory of Gamified Learning: The Effect of Leaderboards on Time-on-Task and Academic Performance. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 769-785. doi 10.1177/1046878114563662 .

- ^ Slavin, R. E. (1980). «Cooperative learning». Review of Educational Research. 50 (2): 315–342. doi:10.3102/00346543050002315. S2CID 220499018.

- ^ a b c d Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- ^ Nicholson, S. (2015). A RECIPE for meaningful gamification. In T. Reiners, & L. C. Wood (Eds.), Gamification in education and business (pp. 1e20). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1.

- ^ Annetta, L. A. (2010). «The «I’s» have it: A framework for serious educational game design». Review of General Psychology. 14 (2): 105–112. doi:10.1037/a0018985. S2CID 35381273.

- ^ Sailer, Michael; Homner, Lisa (2020-03-01). «The Gamification of Learning: a Meta-analysis». Educational Psychology Review. 32 (1): 77–112. doi:10.1007/s10648-019-09498-w. ISSN 1573-336X.

- ^ Werbach, K. & Hunter, D. (2015). The Gamification Toolkit: Dynamics, Mechanics, and Components for the Win. Wharton Digital Press.

- ^ Reiners, Torsten; Wood, Lincoln C. (2014-11-22). Gamification in education and business. Reiners, Torsten,, Wood, Lincoln C. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 9783319102085. OCLC 899000643.

- ^ Van Grove, Jennifer (28 July 2011). «Gamification: How Competition Is Reinventing Business, Marketing & Everyday Life». Mashable. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Kleinberg, Adam (18 July 2011). «HOW TO: Gamify Your Marketing». Mashable. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ «Ads for Obama campaign: ‘It’s in the game’«. NBC News. 2008-10-14. Archived from the original on 2018-09-12. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ «Top 10 Games You Can Play on Facebook». Mashable. 16 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ Daniels, Matt (September 23, 2010). «Businesses need to get in the game». Marketing Week. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (August 25, 2010). «Website builder DevHub gets users hooked by «gamifying» its service». VentureBeat. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Toubia, Olivier (October 2006). «Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives» (PDF). Marketing Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-20.

- ^ Jeffries, Adrianne (16 September 2011). «The Fitocrats: How Two Nerds Turned an Addiction to Videogames Into an Addiction to Fitness». The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ AlMarshedi, Alaa; Wills, Gary; Ranchhod, Ashok (2016-09-09). «Gamifying Self-Management of Chronic Illnesses: A Mixed-Methods Study». JMIR Serious Games. 4 (2): e14. doi:10.2196/games.5943. PMC 5035381. PMID 27612632.

- ^ Brown, Menna; O’Neill, Noelle; van Woerden, Hugo; Eslambolchilar, Parisa; Jones, Matt; John, Ann (2016-08-24). «Gamification and Adherence to Web-Based Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review». JMIR Mental Health. 3 (3): e39. doi:10.2196/mental.5710. PMC 5014987. PMID 27558893.

- ^ Lukhele, Bhekumusa Wellington; Musumari, Patou; El-Saaidi, Christina; Techasrivichien, Teeranee; Suguimoto, S. Pilar; Ono Kihara, Masako; Kihara, Masahiro (2016-11-22). «Efficacy of Mobile Serious Games in Increasing HIV Risk Perception in Swaziland: A Randomized Control Trial (SGprev Trial) Research Protocol». JMIR Research Protocols. 5 (4): e224. doi:10.2196/resprot.6543. PMC 5141336. PMID 27876685.

- ^ Gabarron, Elia; Schopf, Thomas; Serrano, J. Artur; Fernandez-Luque, Luis; Dorronzoro, Enrique (2013-01-01). «Gamification strategy on prevention of STDs for youth». Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 192: 1066. ISSN 0926-9630. PMID 23920840.

- ^ Castro-Sánchez, Enrique; Kyratsis, Yiannis; Iwami, Michiyo; Rawson, Timothy M.; Holmes, Alison H. (2016-01-01). «Serious electronic games as behavioural change interventions in healthcare-associated infections and infection prevention and control: a scoping review of the literature and future directions». Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 5: 34. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0137-0. PMC 5062920. PMID 27777755.

- ^ a b c d Lister, Cameron; West, Joshua H; Cannon, Ben; Sax, Tyler; Brodegard, David (2014-08-04). «Just a Fad? Gamification in Health and Fitness Apps». JMIR Serious Games. 2 (2): e9. doi:10.2196/games.3413. PMC 4307823. PMID 25654660.

- ^ Schwartz, Terri (July 8, 2016). «Pokemon Go is Secretly the Best Exercise App out there». IGN. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Patrick (July 12, 2016). «The Pokémon Go Interval Training Workout». Lifehacker. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Belluz, Julia (12 July 2016). «Pokémon Go may be the greatest unintentional health fad ever». Vox. Archived from the original on 2016-07-14.

- ^ McFarland, Matt (October 12, 2016). «Pokemon Go could add 2.83 million years to users’ lives». CNN Money. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ «Urban Exergames: How Architects and Serious Gaming Researchers Collaborate on the Design of Digital Games that Make You Move» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Owen (October 5, 2010). «Should you run your business like a game?». Venture Beat. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Huling, Ray (March 25, 2010). «Gamification: Turning Work Into Play». H Plus Magazine. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Mangalindan, JP (September 3, 2010). «Play to win: The game-based economy». Fortune. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012.

- ^ John Markoff (10 August 2010). «In a Video Game, Tackling the Complexities of Protein Folding». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Saini, Angela (2008-05-14). «Solving the web’s image problem». bbc. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

- ^ Dencheva, Silviya; Prause, Christian R.; Prinz, Wolfgang (2011). «Dynamic Self-moderation in a Corporate Wiki to Improve Participation and Contribution Quality» (PDF). ECSCW 2011: Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 24-28 September 2011, Aarhus Denmark. Springer. p. 1. doi:10.1007/978-0-85729-913-0_1. ISBN 978-0-85729-912-3. S2CID 11559993. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Morschheuser, Benedikt; Hamari, Juho; Koivisto, Jonna; Maedche, Alexander (October 2017). «Gamified crowdsourcing: Conceptualization, literature review, and future agenda». International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 106: 26–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2017.04.005.

- ^ Deterding, Sebastian; Dixon, Dan; Khaled, Rilla; Nacke, Lennart (2011). «From game design elements to gamefulness: defining «gamification»«. Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments — MindTrek ’11. Tampere, Finland: ACM Press: 9–15. doi:10.1145/2181037.2181040. ISBN 978-1-4503-0816-8. S2CID 207193782.

- ^ Feng, Yuanyue; Jonathan Ye, Hua; Yu, Ying; Yang, Congcong; Cui, Tingru (April 2018). «Gamification artifacts and crowdsourcing participation: Examining the mediating role of intrinsic motivations». Computers in Human Behavior. 81: 124–136. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.018.

- ^ Goh, Dion Hoe-Lian; Pe-Than, Ei Pa Pa; Lee, Chei Sian (May 2017). «Perceptions of virtual reward systems in crowdsourcing games». Computers in Human Behavior. 70: 365–374. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.006.

- ^ «The Gamification of Education». Knewton. Archived from the original on 2015-03-09. Retrieved 2014-04-18.

- ^ Simone de Sousa Borges; Vinicius H. S. Durelli; Helena Macedo Reis; Seiji Isotani (2014). «A systematic mapping on gamification applied to education». Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’14). pp. 216–222. doi:10.1145/2554850.2554956. ISBN 9781450324694.

- ^ Babajide Osatuyi; Temidayo Osatuyi; Ramiro de la Rosa (2018). Systematic Review of Gamification Research in IS Education: A Multi-method Approach. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. Vol. 42. doi:10.17705/1CAIS.04205.

- ^ Remko W. Helms; Rick Barneveld; Fabiano Dalpiaz (2015). A Method for the Design of Gamified Trainings. Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS).

- ^ Shantanu Sinha (February 14, 2012). «Motivating Students and the Gamification of Learning». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Sara Corbett (15 September 2010). «Learning by Playing: Video Games in the Classroom». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Moro, Christian; Stromberga, Zane (2020-07-05). «Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences». Medical Education. 54 (12): 1180–1181. doi:10.1111/medu.14251. ISSN 0308-0110. PMID 32438478. S2CID 218832175.

- ^ Moro, Christian; Phelps, Charlotte; Stromberga, Zane (2020-08-14). «Utilizing serious games for physiology and anatomy learning and revision». Advances in Physiology Education. 44 (3): 505–507. doi:10.1152/advan.00074.2020. ISSN 1043-4046. PMID 32795126.

- ^ Souza, Mauricio Ronny de Almeida; Constantino, Kattiana Fernandes; Veado, Lucas Furtini; Figueiredo, Eduardo Magno Lages (November 2017). «Gamification in Software Engineering Education: An Empirical Study». 2017 IEEE 30th Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T). Savannah, GA: IEEE: 276–284. doi:10.1109/CSEET.2017.51. ISBN 978-1-5386-2536-1. S2CID 37873687. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ^ Bratel, Olena; Kostiuk, Maryna; Bratel, Sergiy; Okhrimenko, Ivan (2021-11-13). «Student-centered online assesment in foreign language classes». Linguistics and Culture Review. 5 (S3): 926–941. doi:10.21744/lingcure.v5nS3.1668. ISSN 2690-103X. S2CID 243804429.

- ^ Fallows, James (28 April 2011). «The Return of Clippy». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ «Office Labs: Ribbon Hero 2». Microsoft. 20 June 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Herger, Mario (Oct 28, 2011). «Enterprise Gamification — Sustainability examples». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ «The Gamification of Corporate Training». Korn Ferry. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- ^ «Gamification Improves Work Experience for 91% of Employees, Increases Productivity Across U.S. Companies» (Press release). PR Newswire. August 6, 2015. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Vigoroso, Lucia; Caffaro, Federica; Micheletti Cremasco, Margherita; Cavallo, Eugenio (2021-02-15). «Innovating Occupational Safety Training: A Scoping Review on Digital Games and Possible Applications in Agriculture». International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (4): 1868. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041868. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7918640. PMID 33671867.

- ^ Williams-Bell, F. M.; Kapralos, B.; Hogue, A.; Murphy, B. M.; Weckman, E. J. (May 2015). «Using Serious Games and Virtual Simulation for Training in the Fire Service: A Review». Fire Technology. 51 (3): 553–584. doi:10.1007/s10694-014-0398-1. ISSN 0015-2684. S2CID 110369959. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Laukkanen, Tuula (January 1999). «Construction work and education: occupational health and safety reviewed». Construction Management and Economics. 17 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1080/014461999371826. ISSN 0144-6193. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Gao, Yifan; Gonzalez, Vicente A.; Yiu, Tak Wing (September 2019). «The effectiveness of traditional tools and computer-aided technologies for health and safety training in the construction sector: A systematic review». Computers & Education. 138: 101–115. arXiv:1808.02021. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.05.003. S2CID 51935760. Archived from the original on 2020-06-23. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Jarret Brachman; Alix Levine (April 13, 2010). «The World of Holy Warcraft:How al Qaeda is using online game theory to recruit the masses». Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Ungerleider, Neal (April 22, 2011). «Welcome To JihadVille». Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ Hatton, Celia (26 October 2015). «China ‘social credit’: Beijing sets up huge system». BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b Evans, Robert (4 August 2019). «The El Paso Shooting and the Gamification of Terror». Bellingcat. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Benjamin Lowry, Paul; Gaskin, James; Twyman, Nathan W.; Hammer, Bryan; Roberts, Tom L. (2013). «Taking ‘fun and games’ seriously: Proposing the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM)». Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 14 (11): 617–671. doi:10.17705/1jais.00347. S2CID 2810596. SSRN 2177442.

- ^ Dignan, Larry (September 30, 2010). «Will the gamification of Windows Phone 7 set it apart?». ZDnet. Archived from the original on October 11, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Dennis L. Kappen; Lennart E. Nacke (2013). The Kaleidoscope of Effective Gamification: Deconstructing Gamification in Business Applications. Proceedings of Gamification ’13. pp. 119–122. doi:10.1145/2583008.2583029.

- ^ «Five Steps to Enterprise Gamification | UX Magazine». uxmag.com. August 2013. Archived from the original on 2016-11-30. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ^ Jim Giles (19 July 2012). «The password you can use without knowing it?». New Scientist. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Christien Kroeze (16 August 2012). «Gamifying authentication». 2012 Information Security for South Africa. IEEE Conference Proceedings. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1109/ISSA.2012.6320439. ISBN 978-1-4673-2159-4. S2CID 7689282.

- ^ Grace, Lindsay (2011). «Gamifying Archives, A Study of Docugames as a Preservation Medium». 2011 16th International Conference on Computer Games (CGAMES). Computer Games (CGAMES), 2011 16th International Conference on. IEEE Press. pp. 172–176. doi:10.1109/CGAMES.2011.6000335. ISBN 978-1-4577-1451-1. S2CID 15269611.

- ^ Hurley, Ben (May 16, 2013). «Everyone loves winning: how Rydges used gamification to double sales». afr.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ «What are Gamification Casinos in 2022». Gamblescope. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ Walz, Steffen (2015). The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications. MIT Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780262325721. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ^ Nick Pelling (2011-08-09). «The (short) prehistory of «gamification»…» Nick Pelling. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ^ Pelling, Nick (2003). «Nick Pelling’s copy of Conundra Ltd. home page circa 2003». nanodome.com. Nick Pelling. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ^ «Conundra Ltd. directors». duedil.com. Duedil. Archived from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ^ «Gamification at Google Trends». Google Trends. Archived from the original on 2014-01-19. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ^ Zichermann, Gabe; Cunningham, Christopher (August 2011). «Preface». Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps (1st ed.). Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media. pp. ix, 208. ISBN 978-1-4493-1539-9. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

Gamification may be a new term

- ^ Adelman; Lauber; Nelson; Smith (April 1989). «Toward a Procedure for Minimizing and Detecting False Positive Diagnoses of Learning Disability». The Journal of Learning Disabilities. 22 (4): 234–244. doi:10.1177/002221948902200407. PMID 2738459. S2CID 45379145.

- ^ Theresa-Marie Rhyne (October 2000). The impact of computer games on scientific & information visualization (panel session): «if you can’t beat them, join them». IEEE Visualization 2000. IEEE Computer Society. pp. 519–521. ISBN 1-58113-309-X. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ^ JP Mangalindan (2010-09-03). «Play to win: The game-based economy». Fortune. Archived from the original on 2012-11-12. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ^ Sinanian, Michael (April 12, 2010). «The ultimate healthcare reform could be fun and games». Venture Beat. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Mark J. Nelson (2012). Soviet and American precursors to the gamification of work (PDF). Proceedings of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference. pp. 23–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Fuchs, Mathias (2012). «Ludic interfaces. Driver and product of gamification». GAME, vol. 1, 2012 – ALL OF US, PLAYERS. Game: The Italian Journal of Game Studies. Vol. 1. Bologna, Italy: The Italian Journal of Game Studies, Ass.ne Culturale Ludica, Bologna, Via V.Veneto. ISSN 2280-7705. Archived from the original on 2012-09-21. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ^ «gsummit 2013 Why Atten». Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ^ «Bunchball.com». Bunchball. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ Taylor, Colleen (May 2, 2011). «For Startups, Timing Is Everything — Just Ask Bunchball». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ Carless, Simon (September 17, 2008). «AGDC: Paharia, Andrade On Making Dunder Mifflin Infinity». Gamasutra. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ «Bunchball Sees Huge Growth in Gamification and Doubles Customer Base in a Year». Bunchball. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ «Badgeville Raises $12 Million, Celebrates With An Infographic». TechCrunch. July 12, 2011. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Rai, Varun; Beck, Ariane (June 20, 2016). «Serious Games in Breaking Informational Barriers in Solar Energy». SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2816852. S2CID 156194157. SSRN 2816852. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ Rai, Varun; Beck, Ariane; Lakkaraju, Kiran (18 January 2017). «Small Is Big: Interactive Trumps Passive Information in Breaking Information Barriers and Impacting Behavioral Antecedents». PLOS ONE. 12 (1): e0169326. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1269326B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169326. PMC 5242502. PMID 28099478.

- ^ Feeney, Robert (April 2017). «Old Tricks Are the Best Tricks: Repurposing Programmed Instruction in the Mobile Digital Age». Performance Improvement. 56 (5): 6–17. doi:10.1002/pfi.21694. S2CID 64490539. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ^ Mazur-Stommen, Susan; Farley, Kate (October 2016). «Games for Grownups: the role of Gamification in Climate Change and Sustainability» (PDF). Indicia Consulting. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ^ Beitz, Mike (July 12, 2013). «‘UW Stratford campus to host international gamification conference’, by Mike Betz». thebeaconherald.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Herger, Mario (Jan 4, 2012). «Gamification and Law or How to stay out of Prison despite Gamification». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ «Virtual Currency Schemes» (PDF). European Central Bank. Oct 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ Sarro, Doug (1 May 2022). «Using gaming tactics in apps raises new legal issues». The Conversation. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ John Pavlus (November 4, 2010). «Reasons Why «Gamification» is Played Out». Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Gabrielle, Vincent (2018-11-01). «The dark side of gamifying work». Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Van Mierlo, Trevor; Hyatt, Douglas; Ching, Andrew T.; Fournier, Rachel; Dembo, Ron S. (2016). «Behavioral Economics, Wearable Devices, and Cooperative Games: Results From a Population-Based Intervention to Increase Physical Activity». JMIR Serious Games. 4 (1): e1. doi:10.2196/games.5358. PMC 4751337. PMID 26821955.

- ^ Jon Radoff (February 16, 2011). «Gamification». Radoff.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011.

- ^ Margaret Robertson. «Can’t Play Won’t Play». Hideandseek.net. Archived from the original on 2010-10-09.

- ^ Zichermann, Gabe (2011-08-10). «Lies, Damned Lies and Academics». Gamification.co. Archived from the original on 2014-07-10. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ Herger, Mario (12 March 2016). «Gamification is Bullshit? The academic tea-party-blog of gamification». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Herger, Mario (31 March 2020). «Gamification facts & Figures». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Michie, Susan; Stralen, Maartje M van; West, Robert (2011-04-23). «The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions». Implementation Science. 6 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. PMC 3096582. PMID 21513547.

- ^ Slavin, Kevin (June 9, 2011). «In a World Filled With Sloppy Thinking». Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ Chaplin, Heather (March 29, 2011). «I Don’t Want To Be a Superhero». Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ McGonigal, Jane. «How To Reinvent Reality Without Gamification». GDC. Archived from the original on 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ Bogost, Ian (3 May 2011). «Persuasive Games: Exploitationware». Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ Herger, Mario (12 March 2016). «About the Term Gamification: Why I Hate It AND Why I Love It». Enterprise-Gamification.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ «Steve Lopez: Disneyland workers answer to ‘electronic whip’«. Los Angeles Times. 2011-10-19. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

Further reading[edit]

- Boller, Sharon; Kapp, Karl M. (2017). Play to Learn: Everything You Need to Know About Designing Effective Learning Games. ISBN 978-1562865771.

- Burke, Brian (2014). Gamify: How Gamification Motivates People to Do Extraordinary Things. Bibliomotion. ISBN 978-1-937134-85-3.

- Chou, Yu-kai (2015). Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards. Octalysis Media. ISBN 978-1-5117-4404-1.

- Fuchs, Mathias; Fizek, Sonia; Ruffino, Paolo; Schrape, Niklas (2014). Rethinking Gamification. Lüneburg: meson press. ISBN 978-3-95796-000-9.

- Gray, Dave; Brown, Sunni; Macanufo, James (2010). Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers. ISBN 978-0596804176.

- Haiken, Michele (2017). Gamify Literacy: Boost Comprehension, Collaboration and Learning. International Society for Technology in Education. ISBN 978-1-56484-386-9.

- Herger, Mario (2014). Enterprise Gamification – Engaging people by letting them have fun (Vol. 01). EGC Media. ISBN 978-1-4700-0064-6.

- Horachek, David (2014). Creating eLearning Games with Unity. Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84969-343-1.

- Hugos, Michael (2012). Enterprise Games – Using Game Mechanics to Build a Better Business. O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-1956-4.

- Kapp, Karl M.; Blair, Lucas; Mesch, Rich (2013). The Gamification of Learning and Instruction Fieldbook: Ideas into Practice. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-67724-7.

- Kumar, Janaki; Herger, Mario (2013). Gamification At Work. Interaction Design Foundation. ISBN 978-87-92964-07-6.

- Marczewski, Andrzej (2018). Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Unicorn Edition. CreateSpace Independent Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7240-1710-9.

- McGonigal, Jane (2015). SuperBetter: A Revolutionary Approach to Getting Stronger, Happier, Braver and More Resilient. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0-670-06954-5.

- Pennenberg, Adam L. (2013). Play At Work – How games Inspire Breakthrough Thinking. Portfolio Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59184-479-2.

- Routledge, Helen (2015). «Why Games Are Good For Business: How to Leverage the Power of Serious Games, Gamification and Simulations». Palgrave Macmillan.

- Suriano, Jason (2017). Office Arcade: Gamification, Byte-Size Learning, and Other Wins on the Way to Productive Human Resources. Lioncrest Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6196-1605-9.

- Zichermann, Gabe; Linder, Joselin (2013). The Gamification Revolution – How Leaders Leverage Game Mechanics to Crush the Competition. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-180831-6.

: the process of adding games or gamelike elements to something (such as a task) so as to encourage participation

gamify

transitive verb

gamified; gamifying; gamifies

Easy-to-use Web- and mobile-based learning platforms … take the boredom out of long training sessions by gamifying the entire process. A training manual is replaced by an interactive game that allows participants to win awards and be acknowledged.

—

Did you know?

The basic concept of gamification isn’t new, but the word itself is a 21st-century addition to the English lexicon. The word refers to the incorporation of game elements, like point and reward systems, to tasks as incentives for people to participate. In other words, gamification is about making something potentially tedious into a game. Gamification is effective because it taps into people’s natural desires for competition and achievement. Teachers, managers, and others use gamification to increase participation and improve productivity. Gamification is also often an essential feature in apps and websites designed to motivate people to meet personal challenges, like weight-loss goals and learning foreign languages; tracking your progress is more fun if it feels like a game.

Example Sentences

Recent Examples on the Web

The sub-themes in education and creativity include learning (informal, accidental, and online, etc.), games (serious games, leisure, gamification, etc.), definitions, and design (in, of and for citizen science).

—

Nongaming apps use gamification to tap into this too (consider Duolingo’s streaks or the challenges and leagues in fitness apps).

—

For example, companies can employ gamification to incentivize people — and create FOMO — to come to the office more often, engage with colleagues from across the building and the world, and make the app fun and interactive.

—

Use learning platforms that engage the learner with recommendations, social cues, badges, goals, reminders, and gamification.

—

The approach combines wellness exercises with gamification.

—

To aid in hosting a hybrid event, consider including gamification features such as participant leader boards, chats, Q&As and contests.

—

One of the key corporate leadership training market trends is the emergence of gamification in corporate training, expected to impact the industry positively in the forecast period, according to the report.

—

There are concerns that gambling on politics only exacerbates the gamification of an American political system that already feels too much like a reality show.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘gamification.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

First Known Use

2006, in the meaning defined above

Time Traveler

The first known use of gamification was

in 2006

Podcast

Get Word of the Day delivered to your inbox!

Dictionary Entries Near gamification

-gamies

gamification

gamin

Cite this Entry

“Gamification.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gamification. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

Last Updated:

8 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

What is gamification?