Today, I want to talk about two different spellings of the same word: everything vs. every thing. Is there any difference between these two, other than a space?

Are they similar to everyone / every one, where there is a clear difference in meaning?

Let’s find out.

There doesn’t appear to be a major difference in meaning between these two spellings; the one-word everything is now the default and more common spelling.

It has been said that every thing suggests things as individual items or units, while everything suggests all items as a collective unit. I’ve tried to illustrate this with the following examples.

- Every thing on this menu is bad for you.

- Everything on this menu is bad for you.

If it’s still unclear how these could be different, try the following sentences.

- Every item on this menu is bad for you.

- All of the items on this menu are bad for you.

The difference is one of emphasis, one focuses on the individual items, the other focuses on all items as a unit.

That said, the one-word everything has become universal, as everything is rarely spelled as two words.

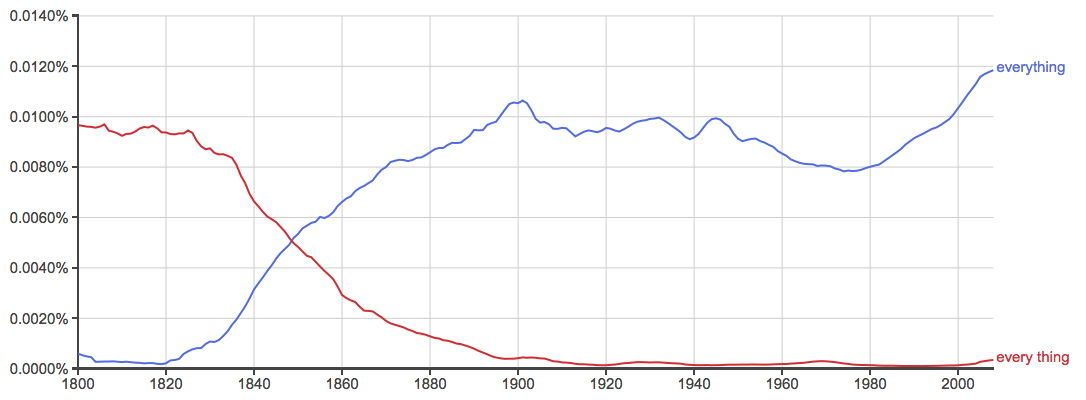

The above chart graphs every thing vs. everything in books over the past 200 years. Sometime in the middle of the 19th century, every thing began to be written as one word. This is consistent across American English and British English.

When to Use Everything

What does everything mean? Everything (one word) is the default spelling. It is defined as all things; all things of a group or class; all things of importance; the most important fact or consideration.

- Everything in this house will need to be replaced.

- It is the black hole of the Rangers lineup, and coach Alain Vigneault is doing everything he can to keep it from sucking away any semblance of a balanced forward group. –New York Post

- In business, location is everything.

When to Use Every thing

Is is now rare to see everything written as two words. There are some circumstances, however, that call for the two-word every thing, and that is when an additional adjective is placed in between both words.

- He corrects every little thing that you say.

- Every single thing she touches is a success.

This is common in speech but rarely seen in writing—especially formal writing of any kind.

Everything Uses Singular Verbs

- The houses were damaged after the tornado, but everyone was all right. (Correct)

- The houses were damaged after the tornado, but everyone were all right. (Wrong)

In this example, everything refers to many different people, but it still takes the singular verb was, not were. For a discussion on was vs. see, see here.

Popular Phrases that Use Everything

Have Everything. This is another informal phrase that means to possess every attraction or advantage.

- She has a successful career, a loving husband, and two wonderful kids; she has everything.

Summary

Is it every thing or everything? There is little, if any, difference in meaning between the two.

Everything is now the default spelling, but is separated into two words when an adjective comes in the middle (every single thing).

Contents

- 1 What is the Difference Between Everything and Every thing?

- 2 When to Use Everything

- 3 When to Use Every thing

- 4 Everything Uses Singular Verbs

- 5 Popular Phrases that Use Everything

- 6 Summary

.

There are some rules for joining two different words into one, but they do not cover all cases

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY ABOUT JOINING WORDS TOGETHER

Is it correct to write bath tub, or should it be the single word bathtub? Is every day a correct spelling, or everyday? Uncertainties like this are widespread in English, even among proficient users. They are made worse by the fact that in some cases both spellings are correct, but mean different things.

Are there any guidelines for resolving such uncertainties? It seems that in some cases there are and in some there are not. I wish here to indicate some of these guidelines. They mostly involve combinations that can make either one word or two, depending on meaning or grammar.

.

ORDINARY COMPOUNDS

Ordinary compounds are the area with the fewest guidelines. They include words like coursework, which I like to write as a single word but my Microsoft Word spellchecker tells me should be two. As a linguist, I usually disregard computer advice about language (see 68. How Computers Get Grammar Wrong), but the question of why ordinary compound words give especial problems is interesting. First, these words need to be defined.

One can think of a compound as two or more words joined together. Linguists, though, like to speak of joined roots or stems rather than words, partly because the joining into a compound stops them being words (a few are not even words by themselves, e.g. horti- in horticulture).

Another problem with “joined words” is that some, such as fearless, are not considered compounds at all. The -less ending is called not a “root” but an “affix”, a meaningful word part added to a root to modify its meaning. Most affixes (some named suffixes, e.g. -less, -ness, -tion, -ly, -ing; some prefixes, e.g. -un-, in-, mis-, pre-) cannot be separate words, but a few like -less can (see 106. Word-Like Suffixes and 146. Some Important Prefix Types). Thus, words like fearless, unhappy and international are not compounds because they have fewer than two roots. Other compounds are swimsuit, homework and eavesdrop.

Suggestions for recognising a compound are not always very helpful. The frequency of words occurring together is no guide because it ignores the fact that many frequent combinations are not compounds (e.g. town hall and open air). The grammatical classes of the words and the closeness of the link between them are sometimes mentioned, but are unreliable. The age of a combination is also suggested, the claim being that compounds originate as two separate words, and gradually evolve through constant use first into hyphenated expressions (like fire-eater or speed-read – see 223. Uses of Hyphens), and eventually into compounds. However, some quite recent words are already compounds, such as bitmap in computing.

Much more useful is the way compounds are pronounced. Single English words generally contain one syllable that is pronounced more strongly than the others (see 125. Stress and Emphasis). This means compounds should have just one strong syllable, while non-compounds should have more. The rule applies fairly universally (see 243. Pronunciation Secrets, #3). For example, home is the only strong syllable in homework, but one of two in home rule. I write coursework as one word because course- is stronger than work.

The only problem with this approach is that you have to know pronunciations before you start, which is not always the case if English is not your mother tongue. The only other resort is a dictionary or spellcheck!

.

NOUNS DERIVED FROM PHRASAL VERBS

Happily, some compound words have some other helpful features. Most are words whose roots, if written as two words, are also correct but have different meaning and grammar, so that the meaning indicates the spelling or vice versa. A particularly large category of such words is illustrated by the compound noun giveaway (= “obvious clue”). If its two roots are written separately as give away, they become a “phrasal” verb – a combination of a simple English verb (give) with a small adverb (away) – meaning “unintentionally reveal” (see 244. Special Uses of GIVE, #12).

There are many other nouns that can become phrasal verbs, e.g. takeover, takeaway, makeup, cutoff, breakout, setdown, pickup, washout, login and stopover. In writing there is always a need to remember that, if the two “words” are going to act as a verb, they must be spelled separately, but if they are going to act as a noun, they must be written together.

.

OTHER CHOICES THAT DEPEND ON WORD CLASS

In the examples above, it is the choice between noun and verb uses that determines the spelling. Other grammatical choices can have this effect too. The two alternative spellings mentioned earlier, every day and everyday, are an example. The first (with ev- and day said equally strongly) acts in sentences like a noun or adverb, the second (with ev- the strongest) like an adjective. Compare:

(a) NOUN: Every day is different.

(b) ADVERB: Dentists recommend cleaning your teeth every day.

(c) ADJECTIVE: Everyday necessities are expensive.

In (a), every day is noun-like because it is the subject of the verb is (for details of subjects, see 12. Singular and Plural Verb Choices). In (b), the same words act like an adverb, because they give more information about a verb (cleaning) and could easily be replaced by a more familiar adverb like regularly or thoroughly (see 120. Six Things to Know about Adverbs). In (c), the single word everyday appears before a noun (necessities), giving information about it just as any adjective might (see 109. Placing an Adjective after its Noun). It is easily replaced by a more recognizable adjective like regular or daily. For more about every, see 169. “All”, “Each” and “Every”.

Another example of a noun/adverb contrast is any more (as in …cannot pay any more) versus anymore (…cannot pay anymore). In the first, any more is the object of pay and means “more than this amount”, while in the second anymore is not the object of pay (we have to understand something like money instead), and has the adverb meaning “for a longer time”.

A further adverb/adjective contrast is on board versus onboard. I once saw an aeroplane advertisement wrongly saying *available onboard – using an adjective to do an adverb job. The adverb on board is needed because it “describes” an adjective (available). The adjective form cannot be used because there is no noun to describe (see 6. Adjectives with no Noun 1). A correct adjective use would be onboard availability.

Slightly different is alright versus all right. The single word is either an adjective meaning “acceptable” or “undamaged”, as in The system is alright, or an adverb meaning “acceptably”, as in The system works alright. The two words all right, on the other hand, are only an adjective, different in meaning from the adjective alright: they mean “100% correct”. Thus, Your answers are all right means that there are no wrong answers, whereas Your answers are alright means that the answers are acceptable, without indicating how many are right.

Consider also upstairs and up stairs. The single word could be either an adjective (the upstairs room) or an adverb (go upstairs) or a noun (the upstairs). It refers essentially to “the floor above”, without necessarily implying the presence of stairs at all – one could, for example, go upstairs in a lift (see 154. Lone Prepositions after BE). The separated words, by contrast, act only like an adverb and do mean literally “by using stairs” (see 218. Tricky Word Contrasts 8, #3).

The pair may be and maybe illustrates a verb and adverb use:

(d) VERB: Food prices may be higher.

(e) ADVERB: Food prices are maybe higher.

In (e), the verb is are. The adverb maybe, which modifies its meaning, could be replaced by perhaps or possibly. Indeed, in formal writing it should be so replaced because maybe is conversational (see 108. Formal and Informal Words).

My final example is some times and sometimes, noun and adverb:

(f) NOUN: Some times are harder than others.

(g) ADVERB: Sometimes life is harder than at other times.

Again, replacement is a useful separation strategy. The noun times, the subject of are in (f), can be replaced by a more familiar noun like days without radically altering the sentence, while the adverb sometimes in (g) corresponds to occasionally, the subject of is being the noun life.

.

USES INVOLVING “some”, “any”, “every” AND “no”

The words some, any, every and no generally do not make compounds, but can go before practically any noun to make a “noun phrase”. In a few cases, however, this trend is broken and these words must combine with the word after them to form a compound. Occasionally there is even a choice between using one word or two, depending on meaning.

The compulsory some compounds are somehow, somewhere and somewhat; the any compounds are anyhow and anywhere, while every and no make everywhere and nowhere. There is a simple observation that may help these compounds to be remembered: the part after some/any/every/no is not a noun, as is usually required, but a question word instead. The rule is thus that if a combination starting with some, any, every or no lacks a noun, a single word must be written.

The combinations that can be one word or two depending on meaning are someone, somebody, something, sometime, sometimes, anyone, anybody, anything, anyway (Americans might add anytime and anyplace), everyone, everybody, everything, everyday, no-one, nobody and nothing. The endings in these words (-one, -body, -thing, -way, -time, -place and –day) are noun-like and mean the same as question words (who? what/which? how? when? and where? – see 185. Noun Synonyms of Question Words).

Some (tentative) meaning differences associated with these alternative spellings are as follows:

SOME TIME = “an amount of time”

Please give me some time.

SOMETIME (adj.) = “past; old; erstwhile”

I met a sometime colleague

.

SOMETHING = “an object whose exact nature is unimportant”.

SOME THING = “a nasty creature whose exact nature is unknown” (see 260. Formal Written Uses of “Thing”, #2).

Some thing was lurking in the water.

.

ANYONE/ANYBODY = “one or more people; it is unimportant who”

Anyone can come = Whoever wants to come is welcome; Choose anyone = Choose whoever you want – one or more people.

ANY ONE = “any single person/thing out of a group of possibilities”.

Any one can come = Only one person/thing (freely chosen) can come; Choose any one = Choose whoever/whichever you want, but only one.

ANY BODY = “any single body belonging to a living or dead creature”.

Any body is suitable = I will accept whatever body is available.

.

ANYTHING = “whatever (non-human) is conceivable/possible, without limit”.

Bring anything you like = There is no limit in what you can bring; Anything can happen = There is no limit on possible happenings.

ANY THING = “any single non-human entity in a set”.

Choose any thing = Freely choose one of the things in front of you.

.

EVERYONE/EVERYBODY = “all people” (see 169. “All”, “Each” and “Every” and 211.General Words for People).

Everyone/Everybody is welcome.

EVERY ONE = “all members of a previously-mentioned group of at least three things (not people)”.

Diamonds are popular. Every one sells easily.

EVERY BODY = “all individual bodies without exceptions”.

.

EVERYTHING = “all things/aspects/ideas”.

Everything is clear.

EVERY THING = “all individual objects, emphasising lack of exceptions”.

Every thing on display was a gift.

.

NO-ONE/NOBODY = “no people”

No-one/Nobody came.

NO ONE = “not a single” (+ noun)

No one answer is right.

NO BODY = “no individual body”.

.

NOTHING = “zero”.

Nothing is impossible.

NO THING = “no individual object”.

There are other problem combinations besides those discussed here; hopefully these examples will make them easier to deal with.

Questions:

| Word | One or Two words? Both? |

| A little | Two words |

| A lot | Two words |

| Anybody | Both |

| Anymore | Both |

| Anything | One word |

| Anyway | Both |

| Awhile | Both |

| Cannot | One word |

| Each other | Two words |

| Every day | Both |

| Everyone | Both |

| Everything | One word |

| Everywhere | One word |

| Maybe | Both |

| Something | One word |

The words listed below are linked to their definitions in http://dictionary.reference.com/

If you’re uncomfortable or you feel like the information might be wrong, please consult your preferable dictionary.

(Some/Other) Dictionaries:

- Collins English Dictionary (CED): http://www.collinsdictionary.com/

- Merriam-Webster: http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- Oxford English Dictionary (OED)

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (SOED) or Shorter English Dictionary (SED)

Is it one word (1) or two words (2)?

Alittle vs. A little: (2) A LITTLE

Alot vs A lot: (2) A LOT

✓ I have a lot of projects to do this week.

× There’s alot of bunnies over there.

Anybody or Any body: (1) ANYBODY or (2) ANY BODY

Note: The exact same concept applies to everybody (pronoun) vs. every body and somebody (pronoun) vs. some body.

(1) Anybody is an pronoun that is defined as “any person” or “anybody.”

✓ Does anybody have an eraser?

× Does any body have an eraser?

(2) Separately, any (adjective) body (noun) means any body of something.

✓ Any body of rock or sediment in which water can flow and be stored is called an aquifer.

× Anybody of rock or sediment in which water can flow and be stored is called an aquifer.

✓ Any body of water commonly refers to bodies of oceans, seas, and lakes.

× Anybody of water commonly refers to bodies of oceans, seas, and lakes.

Anymore or Any more: (1) ANYMORE or (2) ANY MORE

(1) Anymore is an adverb that is defined as “any longer” or “nowadays/presently.”

✓ I don’t go to church anymore.

× I don’t go to church any more

(2) Separately, any (adjective) more (noun) means anything additional.

✓ I cannot watch any more of this show.

× I cannot watch anymore of this show.

Anything or Any thing: (1) ANYTHING

(1) Anything is a pronoun, noun, and adverb. Anything as a pronoun is defined as “does not matter, any thing.”

✓ Just give me anything to fix this mistake.

× Just give me any thing to fix this mistake.

Anything as a noun is defined as “a thing of any kind.”

✓ I just need anything to get away from this place.

× I just need any thing to get away from this place.

Anything as an adverb is defined as “in any degree; in any way.”

✓ If it is anything green then I will like it. ↔ (If it is really green then I will like it – adverb)

× If it is any thing green then I will like it.

Anyway or Any way: (1) ANYWAY or (2) ANY WAY

(1) Anyway is an adverb that is defined as “in any case.” Similar meanings include anyhow, nevertheless, and regardless.

✓ Anyway, I have to work on my assignment now. ↔ (Actually, I have to work on my assignment now – adverb)

× Any way, I have to work on my assignment now.

✓ We’re going to the party anyway.

× We’re going to the party any way.

(2) Separately, any (adjective) way (noun) means every way. When a preposition is there, use any way.

✓ Let’s do this project in any way.

× Let’s do this project in anyway.

✓ Do you know of any way to get to the mall in 10 minutes?

Awhile or A while: (1) AWHILE or (2) A WHILE

(1) Awhile is an adverb that is defined as “for a short time or period.”

✓ Let’s stay awhile. ↔ (Let’s stay obediently – adverb)

× Let’s stay a while.

(2) While as a noun is defined as a period of time. When a preposition is there, use a while.

✓ Let’s stay for a while.

× Let’s stay for awhile.

✓ It has been a while since I talked with John.

✓ I haven’t seen John in a while.

✓ I saw my Mom a while ago.

Cannot or Can not: (1) CANNOT

✓ I cannot go to the party this Tuesday.

× I can not believe this newspaper.

Note: Can’t is also interchangeable with cannot.

I can’t go to the party this Tuesday.

Eachother or Each other: (2) EACH OTHER

✓ Henry and Elizabeth loved each other.

× We gave eachother a present on Christmas.

Note: Each other and One another is interchangeable. Henry and Elizabeth loved one another. For more examples, see Reciprocal Pronouns (Ctrl + F)

Everyday or Every day: (1) EVERYDAY or (2) EVERY DAY

(1) Everyday, meaning daily (use), is an adjective which is used before a noun/object.

✓ I have everyday shoes.

× I have every day shoes.

(2) Separately, every (adjective) day (noun) means every single day or each day.

✓ I go to work every day.

× I go to work everyday.

Everyone or Every one: (1) EVERYONE or (2) EVERY ONE

Note: The exact same concept applies to anyone (pronoun) vs. any one and someone (pronoun) vs. some one.

(1) Everyone is an pronoun that is defined as “every person” or “everybody.“

✓ Everyone is a critic.

× Every one is a critic.

(2) Separately, every (adjective) one (noun) means everyone of something.

✓ Every one of you is a critic.

× Everyone of you is a critic.

Everything or Every thing: (1) EVERYTHING

(1) Everything is a pronoun and a noun.

Everything as a pronoun is defined as 1. “every thing; all.” and 2. something extremely important.

✓ I owe everything to my family.

× I owe every thing to my family.

✓ This job interview tomorrow means everything to me.

× This job interview tomorrow means every thing to me.

Everything as a noun is defined as “something that is extremely important or most important.”

✓ Motivation is everything.

× Motivation is every thing.

Everywhere or Every where: (1) EVERYWHERE

Note: The exact same concept applies to anywhere, elsewhere, nowhere, and somewhere. They are all adverbs of place (Ctrl + F) and they are all one word.

(1) Everywhere is an adverb that is defined as “in all places.”

✓ There were nice people everywhere I went!

× There were nice people every where I went!

Maybe or May be: (1) MAYBE or (2) MAY BE

(1) Maybe is an adverb that (rather informally) means “possibly; perhaps.”

✓ Maybe I’ll be allowed to sleep over at your place today.

× May be I’ll be allowed to sleep over at your place today.

(2) Separately, may (auxiliary verb) be (verb) means “possibly; perhaps.”

✓ I may be allowed to sleep over at your place today.

× I maybe allowed to sleep over at your place today.

Something or Some thing: (1) SOMETHING

(1) Something is a pronoun, noun, and adverb.

Something as a pronoun is defined as 1. “some thing; a undetermined or unspecified thing” and 2. “an additional amount that is unknown, undetermined or unspecified.”

✓ Something doesn’t seem right with that house.

× Some thing doesn’t seem right with that house.

✓ We have to leave our apartment at three something.

× We have to leave our apartment at three some thing.

Something as a noun is informally defined as “a person or thing that has some value”

✓ Our lawyer really knew how to talk something to the judge.

× Our lawyer really knew how to talk some thing to the judge.

Something as an adverb is defined as “in some degree; in some way; somewhat.”

✓ Does this taste something like candy? ↔ (Does this taste really like candy? – adverb)

× Does this taste some thing like candy?

An amazing blog that educates people on the common mistakes in the English language!: http://snarkygrammarguide.blogspot.ca/

Good and long list of compound nouns! http://www.enchantedlearning.com/grammar/compoundwords/

Grammarbook.com also explains some of these confusions: https://data.grammarbook.com/blog/definitions/anymore-v-anymore-and-everyone-v-every-one/