I’m looking for a clear, definitive answer to the following question: Is taking someone else’s writing, and changing some of the words, inherently plagiarism?

I find resources that describe plagiarism are usually a bit vague around this issue. For example, one commonly-quoted book says this (Pechenik, 2001, p. 10):

Don’t plagiarize. Express your own thoughts in your own words…

Note, too, that simply changing a few words here and there, or

changing the order of a few words in a sentence or paragraph, is still

plagiarism. Plagiarism is one of the most serious crimes in academia.

Now, the fact that this passage refers to changing or moving «a few words» leaves open the question of whether changing or moving more words, or many words, would possibly be not-plagiarism. Is there any threshold at which changing words becomes not-plagiarism? Possibly all of them?

The practical concern I have is that recently I’ve gotten a high frequency of students I’ve caught for plagiarizing in my courses (around half) saying something like, «Ah yes, when I took that file I didn’t change enough of the words because I was rushed for time. I’m sorry, next time I’ll change more of the words.»

Ultimately I’m wondering if the best response to that is, «That would still be plagiarism [even if you changed all of the words]!», or if the response needs to be something different and more complex. (I find that for such students with possible language problems, more complicated responses are likely to be disregarded, so I’m looking for a minimalist communication in these situations.)

The best answer will not go into discussions of practical issues of detecting plagiarism. A reference to some authoritative source on this issue would be a value-add.

It may be helpful to note that «plagiarism» is emphasized here because it’s central to my institutions’ (and others’) academic integrity definitions and enforcement mechanisms. In our case, «Copying another person’s actual words or images…» is the primary (but not the only) example of what counts as plagiarism.

asked Jan 10, 2022 at 6:05

14

The clear, definitive answer to your question

Is taking someone else’s writing, and changing some of the words,

inherently plagiarism?

Is YES, and you need to go no further than a dictionary.

the practice of taking someone else’s work or ideas and passing them

off as one’s own.

The moment your students (or anyone, for that matter) tries to solve a writing task by looking for what someone else has written and then trying to include it in their work as their own, it becomes plagiarism no matter how many words they can change; it’s the action of putting/trying to put someone else’s work into theirs what constitutes it.

The thing is, the rest of the body of your question shifts it to both «how can I tell my students/make them understand that what they do is plagiarism?» and «am I wrong by assuming that what my students are doing is plagiarism?».

The latter is easier to answer: no, you’re not wrong. The former, though, is a bit trickier.

Your students already believe that plagiarism is about what can be detected as such, and not what they’re intending to do. This probably isn’t on purpose — they might not be «evil» students, merely misled. You need to make them understand that their offense is not «not changing enough words», it is «thinking of taking the writing of someone else without proper acknowledgment».

Maybe you can make it clear by establishing it with a simple «do/don’t» rule:

DO: write your own thoughts and conclusions, and use citations from other authors or written material to support them.

DON’T: take the writing of other authors/material and put it in your work as yours, neither by copying it as is nor by changing or paraphrasing it.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 21:33

Josh PartJosh Part

3161 silver badge4 bronze badges

1

Is taking someone else’s writing, and changing some of the words, inherently plagiarism?

The most concise, clear answer I can think of is the following: Disallowing plagiarism is about protecting ideas, not words; however, the way something is written is often a (protected) idea. The writing’s structure and organization, the details that are included or excluded, the transitions, the figures, the references — all of this may be protected intellectual property, and none of this is addressed by simply substituting some words for others.

Hence, students are wrong when they believe that all they have to do is «change a few of the words» — even if one does not steal the words, they are still stealing the writing, which is much more than just word choice. The most egregious form of this is when someone copies an entire document and then goes through line by line making trivial changes to the wording. This is absolutely plagiarism: using different words does not change the fact that they are still stealing the writing. (On the other hand, detecting plagiarism is much harder when these substitutions are made…and many students honestly believe that plagiarism is defined by what TurnItIn can detect).

So I’d love to say the answer to your question is an unambiguous «yes» — but consider this sentence:

Elementary particles comprise quarks, leptons, and bosons.

Many students mistakenly believe that they need to make some trivial modification to this sentence to avoid plagiarism. But this sentence contains no «novel ideas» — certainly not in the content, but not really in the writing either; there are only so many reasonable ways in which one can state this fact. Indeed, it is likely others have published this exact sentence before. Hence, taking this sentence without attribution (with or without having changed some of the words) would probably not be inherently plagiarism. But this is a slippery and ill-defined slope: while this seven-word sentence is probably not complex enough for «plagiarism» to be possible, other sentences (particularly longer ones) certainly are.

Finally, we should note that schoolwork presents some unique challenges for avoiding plagiarism. In most nonfiction work, there are four types of information: (1) well-established facts, (2) primary sources, (3) secondary sources, and (4) our novel contribution. Usually, an essay will have most or all of these — #4 is the reason for writing the essay at all, #1 and #2 are important because our work doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and occasionally #3 is helpful. Many schoolwork assignments, however, only have #3 — there is already some writing in a secondary source that single-handedly meets our requirements. And so the student’s job is just to rewrite the existing essay but somehow to make major enough changes so that it becomes original work. This is a subtle distinction that doesn’t have much in common with the real world — no wonder students are confused.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 7:51

cag51♦cag51

61.3k24 gold badges164 silver badges225 bronze badges

16

Students sometimes believe or claim to believe that plagiarism is some highly technical, perplexing concept. While it is important to clarify what plagiarism is and is not to the student, in an actual discussion with a student who believes that they should have «changed more words», I find it helpful to start from an ethical principle that the student will find it much more difficult to misunderstand or claim to misunderstand, namely to give credit where credit is due.

Here is a concrete suggestion. One can get the conversation going by asking whether the student found it helpful to have the relevant passage as a starting point. Make the distinction between using general ideas found in some text and using an actual passage in some book or article as a starting point for one’s own writing. This way of putting it makes the number of words they changed irrelevant. Even if they change every single word, the point is whether or not the specific writing in the source passage was substantially used in the writing process, whatever the end result of this process.

If they answer negatively, you can express skepticism about their answer, since they did in fact actively choose to use it as a starting point for their own writing. If they did find the work that the author of the original passage helpful in composing their own writing, you can ask them whether they believe that the original author is due some credit for that. Whatever they answer, explain that owe some credit to the original author. Then you can get into a discussion of what plagiarism is or is not, but I believe that grounding it in a familiar ethical principle will help. (Confession: I myself find it useful to think in terms of fair vs. unfair use instead of plagiarism vs. not plagiarism, and to use the term «plagiarism» primarily when ill intent is clear.)

Another approach if they say that they will «change more words» next time is to paraphrase this back to them as: I will change more words so that I can avoid citing source X. Then ask them why they wish to avoid citing source X.

If you want to wax philosophical, you can then explain that science only works as a cumulative enterprise which encourages people to stand on the shoulders of giants and ordinary mortals alike. This cannot work unless it is a win–win situation for the people involved. Other people’s work allows you to see further and write better, and conversely, they benefit from having their share in your work acknowledged.

(The point raised by Massimo Ortolano is also important to get across to the student.)

Edit: the other answers focus on using other people’s ideas, which is justified but potentially a bit nebulous. You can also choose to focus on using other people’s work instead, which I find a bit more concrete in this case: they are building on the work that some other person has already put into composing the passage in question.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 14:20

Adam PřenosilAdam Přenosil

4,9802 gold badges16 silver badges21 bronze badges

4

Looking at this definition of Oxford University, plagiarism is using other people’s ideas without acknowledging them. Under this definition, even if you were to change all the words, or rewriting the whole thing in your own words, you would still commit plagiarism, as long as you don’t give credit to the original source where you took the idea from.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 6:55

SursulaSursula

15.7k4 gold badges48 silver badges97 bronze badges

5

Changing a few words is the worst form of plagiarism. It’s basically proof the student knew it was wrong and is trying to hide it (I saw it most often with students copying from a friend’s assignment, but same idea). «I’m sorry I didn’t change more words» is really shorthand for «I know this class doesn’t matter and you don’t care. Let me go and I’ll cheat better next time so you can pretend everything is fine».

There are two reasons we care about plagiarism. One is so our graduates don’t do it. A few years ago an influencer (Rachel Hollis) posted «still…I RISE» without saying it was from Maya Angelou’s «And still I rise». She got ripped a new one and never recovered. And she changed almost half of it! If you have to write an original article and start by rewriting someone else’s, people go nuts. Here’s one about a fired student reporter from my Alma Mater «Tibbs ran an editorial that was about to be published through a plagiarism checker: 71 percent.» Strangely, the article doesn’t mention whether 29% changes were enough — apparently copying with any number of changes is fireable plagiarism. Huh.

The other reason we care about plagiarism is that the assignments are meant to show what you know. Being able to turn it into your own words is the proof you understood something. If you just use an internet search and a thesaurus (also on the internet), that proves nothing, so is worth 0 points, and is also lying. «I wrote this» means you thought of all the words.

For dealing with it, one fun thing is to talk to other students. I’ve found that most fully understand doing your own work vs. copying. And they get seriously angry if they think someone is getting away with messing up the curve and the school’s reputation by cheating. Getting a faceful of «tell me you’re not going to fall for their bullsh*t and let them pass» may be helpful. For a real earful, also tell the student «but they changed a lot of the words».

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 17:26

1

I don’t think there can be a clear definition. The point is whether «changing a few words here and there» meets the learning objectives of the assignment. If not, then it is trying to pass off the the content of the passage that does meet the learning objectives as being their own work and ought to be viewed as plagiarism.

Using a thesaurus or grammar checker to paraphrase the passage probably does not demonstrate any understanding of the topic in addition to the choice of passage. So being able to choose a suitable passage is all that the student deserves marks for (which probably isn’t very much). What value have they added by paraphrasing? What understanding have they demonstrated?

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 15:37

3

Regardless of whether it is plagiarism, think about the context: if a student does this in an assessment then all they are demonstrating is the ability to use a thesaurus. Assuming the goal is not to assess the student’s ability to use a thesaurus, any coursework demonstrating only that ability deserves a very low mark.

This follows regardless of whether you call it «plagiarism». That matters if you are deciding whether to put the student through the institution’s procedure for academic misconduct. I would do this if the student failed to cite the source they had mangled, and not if they had cited it properly. But either way, «work» done this way gets a very low mark because it deserves one.

What I tell students is this:

The ideas are supposed to go from the textbook (or whatever other source) into your head, and from your head into your coursework. If the ideas are going straight from the textbook into your coursework, without going via your head, then you are missing the point.

The problem is not that the work they submitted is «too similar» to the source material, it’s that the process by which they are working does not and cannot lead to useful, meaningful learning. That is true whether or not the process is called «plagiarism», so I’ll leave that question to the philosophers.

answered Jan 11, 2022 at 12:25

kaya3kaya3

1,7654 silver badges15 bronze badges

1

Yes, this is a form of plagiarism called close copying.

answered Jan 12, 2022 at 19:04

Nicole HamiltonNicole Hamilton

30.7k8 gold badges79 silver badges120 bronze badges

1

First, at the end of the day, in a course setting, plagiarism—or the acceptable level thereof—is what the professor decides it to be.

But I think that instead of concentrating on the amount of words changed, the key point that needs to be addressed with the students is another: if you have to read and change the words to write your essay, it means that you didn’t understand the concepts enough to make use of them and, consequently, to pass the exam.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 6:42

Massimo Ortolano♦Massimo Ortolano

55.1k17 gold badges163 silver badges206 bronze badges

4

The easiest thing to tell your students is this:

If you use someone else’s work, cite them. If you don’t, you’re committing plagiarism.

When this issue comes up in undergraduate work, it almost inevitably comes down to intellectual laziness. The student in not focused on school; s’he wants to slide through to a passing grade with minimal thought and effort, because s’he has other concerns: social life and dating, activism, emotional issues or anxiety, etc. These other concerns are natural and important — we all go through a lot of crap in that age-range — but part of the job is encouraging students to learn focus and balance. You’re not doing them any favors by being overly lenient.

If I were in your shoes, I’d look them in the eye and tell them that I understand (because I really do), but that the behavior isn’t acceptable. They need to step up. I’d give them a choice between a zero on the assignment, or a chance to rewrite the paper in a way that convinces me they understand the material. And I’d let them know I’d be reading the revised paper extra carefully. If you can find a way to break the myopic fixation on grades and get them to focus on acquiring knowledge, this problem should solve itself.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 16:08

Ted WrigleyTed Wrigley

4652 silver badges6 bronze badges

Types of Plagiarism

It often helps to break down plagiarism into different types. That’s what Harvard does, for example, breaking it down into six kinds. A lot of other universities use the same or similar categories. The beginning of the course is the best time to (re-)explain what plagiarism is (ideally quoting your school’s own policies) to hopefully prevent it before it happens.

If a student points out they didn’t use the exact same words as the original author, you can point out that they are referring to only a single type of plagiarism (usually called verbatim plagiarism). The type of plagiarism you’re seeing where they «didn’t change enough words» is called either inadequate paraphrase (the wording is too similar) or uncited paraphrase (paraphrased without citation), or both.

The key is that it’s not plagiarism if they paraphrased completely (changing enough of the words and wording) and cited their source. And if they did both but they weren’t allowed to consult with sources, that’s a violation of academic integrity (but not plagiarism).

answered Jan 11, 2022 at 1:09

LaurelLaurel

8068 silver badges17 bronze badges

2

The key concept of plagiarism is presenting someone else’s work as your own. Deception is central to it. If you copy a passage verbatim, that’s not plagiarism if you openly declare it to be a quote. It might be copyright violation, and handing in a paper that consists of nothing but direct quotes is unlikely to receive much credit, but it’s not plagiarism.

Where it gets confusing is that if you’re a student, obviously you’re not doing your own primary research. If you write that most of Napoleon’s troops in the Russian invasion died, then (unless you’re in a really advance program, maybe) nobody’s going to come away thinking that you pored through historical record calculating how many the initial and final troop numbers were. Obviously, you looked up someone else’s work. So using general facts from other people isn’t deceptive (but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t cite them!).

Using other people’s wording, on the other hand, is deceptive. And «using» doesn’t mean just copying verbatim, it also means taking that wording as a basis. Changing someone’s words around is different from writing something de novo, and presenting the former as the latter is deceptive. Taking the dailies from a movie and editing them into a new cut doesn’t make you a director. That’s not a perfect analogy, though, because there’s a clear line between actually shooting scenes versus using someone else’s scenes (and, actually, re-editing a movie is a creative act, it just doesn’t constitute «making a movie»), but there isn’t such a bright line between «moving someone’s words around» and «writing something new».

As to the language issue, while you should make accommodations for language difficulties, ultimately this is your student’s responsibility. It’s your student’s responsibility to learn what plagiarism is, failing that it’s their responsibility to learn enough English to understand an explanation of what plagiarism is, and failing that it’s their responsibility to find someone who can translate the explanation. It’s not acceptable that «more complicated responses are likely to be disregarded», and if they have such a cavalier attitude towards core academic concepts such as plagiarism, they have to live with the consequences. They don’t get to dodge disciplinary repercussions just because «this is hard to read».

answered Jan 11, 2022 at 6:34

Yes.

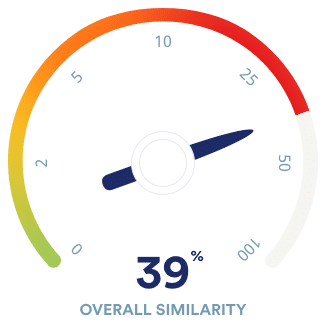

As a student, many institutions provide access to plagiarism checkers, which highlight text that may be dubious.

I used a small paperback version called APA: the Easy Way, my father had once shown me a similar compact Chicago Style Manual.

Here is a link to Worldcat’s list of libraries around Washington DC that have a copy of the first one:

https://www.worldcat.org/title/apa-the-easy-way/oclc/1183823482&referer=brief_results

These work, but you need to read and refer to them.

As a teacher, see if your institution offers a plagiarism checker (turnitin, for example https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG9mtsMkQaDDq3PSxa5zMEA). These allow you to show students exactly how to check themselves and are worth some class time to teach them what’s expected, what’s accepted, and what isn’t.

They also lighten the load for submissions, grading and (in the case of the one I mentioned above) designing assessments.

answered Jan 12, 2022 at 1:14

C raoC rao

211 bronze badge

It is not a question of proportion, or how many words: plagiarism is a qualitative assessment. It is largely a question is claiming as own the idea of someone else.

Clearly direct copying without attribution is plagiarism, but consider the following examples.

During a final exam, two students Charlie and Bob make the same sequence of conceptual errors on a question where they are asked to evaluate the ground state energy of a molecule (for instance). One or both of Charlie and Bob could be guilty of plagiarism even if the texts explaining the calculations are largely different.

As another example, suppose Bob somehow accesses the work in progress of Charlie, and decides to redo this work on his own without acknowledging the source of the work as Charlie’s. Even if Bob’s paper is significantly different in language and structure from Charlie’s, Bob can still be accused of plagiarism.

In the examples above, one can argue that the ideas were improperly claimed to be that of one person (say Bob) whereas in fact they are Charlie’s idea.

answered Jan 10, 2022 at 6:47

ZeroTheHeroZeroTheHero

26k2 gold badges46 silver badges105 bronze badges

2

From my experience, this is taught by high school teachers because they, themselves, do not understand plagiarism; at least, in the US. I wouldn’t blame the students as they were never taught what any of this means: they were taught they have to produce the work required, and if they don’t produce the work required, they cannot continue and will fail the class and are not given any sort of out or alternative path.

This is a version of Goodhart’s Law («When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure») in effect; so many words are required in that assignment, where they come from doesn’t really matter. On top of this, they are taught that referencing anybody’s work (while simultaneously teaching them how to cite work and what citing means) is wrong: if you cite too many works, teachers will happily shave points off your grade as if you had done something wrong.

Sometimes an argument is complex and requires citing a lot of previous work, and all your core contribution is providing the glue for a bunch of cites. In science, this could be the form of a meta-study and all you did was pull your conclusions out of a wider body of work that no single cited paper represents, and it’s entirely possible your paper just concludes that multiple papers agree and reinforce each other and finding that out was your contribution to science because no one else ever wrote this.

Citing other people’s work is not plagiarism, citing other people’s work and paraphrasing it (without changing the meaning) is not plagiarism. Copying it verbatim without cite is plagiarism, paraphrasing without citing and without adding anything meaningful to the new version is plagiarism. This is commonly not taught to students, so don’t blame them, just try to teach them.

answered Jan 11, 2022 at 9:27

To answer the titular question: absolutely yes.

Now when it is dealt with, the bigger issue at hand is that students don’t understand your expectations and the reasoning behind them.

Make sure they understand what materials they are supposed to use for their assignments, how and why. Similar to how students doubted the need to not use the calculator for arithmetic in school, they now might be doubting the need to calculate something else by hand when Wolfram or Maple exist. To the similar tune, if they looked it up online and there is the exact solution to their problem, why not just use it? Are they to pretend they never saw it?

To me, the perfect approach is when they either already know from your material or find in someone else’s work the approximation to an answer and have to fill in the gaps, and if the problem is purely technical, doing calculations by hand is helpful but only if they are your focus as a teacher, and some people struggle more than others with those; you might need to consider accommodating them as well. If taking prior work is fine by you long as the proper attribution is given (after all, someone has to teach students to work with literature!), state that explicitly. Unfortunately, school focuses on «no cheating/copying» in a way that leads students to the «just don’t get caught» mentality you seek to get rid of.

So meet the students where they are, consider what skills you deem important for them to develop, and sit down with them so that they explain their solutions to you.

As an exercise, you might even ask them to explain some relatively trivial fact so that they know the difference between common knowledge, where the attribution is not needed, and deriving works.

answered Jan 13, 2022 at 7:58

LodinnLodinn

8,24510 silver badges45 bronze badges

Let’s look at from a different perspective. What would it look like to not plagiarise a source. You would discuss how the ideas and information from the source applies to your specific problem (or topic). So at the very least you synthesise the source with your own essay topic. This might involve a bit of paraphrasing (or quotation in even less cases) but only in so far as you explain the ideas in order to then relate them to your own.

Of course there are cases where you need factual information, in which case a simple quotation may be best. At university level that should not earn many marks though (only demonstrating the skill to summarise)

answered Jan 26 at 20:48

2

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

Continue Learning about Educational Theory

What constitutes paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is when you restate something in your own words,

keeping the meaning the same. It is the opposite of quoting, which

means to repeat something word for word.

What is paraphrasing in counseling?

paraphrasing is when you repeat what the client have said but in

your own word it also allows the client to correct you if there was

any misundrstanding.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is taking a quote and cutting the fat. Kind of like putting someone else’s words into your own words but still saying the same thing.Paraphrasing-Repeating what another has said, but in your own words.

What are the importance of curriculum evaluation?

The main purpose of curriculum evaluation is to assure that it

is not static, but constantly changing according to changing needs

and demands of the society. The new curriculum should fulfill the

needs of changing society.

What word best summarizes one of the problems with online research?

credibility.

clicking here.

This message will disappear when then podcast has fully loaded.

In academic writing, you will need to use other writer’s ideas to support your own. The most common way to do this is by using

paraphrase. This section considers how to do this by first looking in more detail at

what paraphrasing is, then giving

reasons for using paraphrase, and finally considering

how to paraphrase.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrase is one of three ways of using another writer’s work in your own writing, the other two being quotation and

summary.

The aim of paraphrasing is to change the words in the original text, while keeping the same meaning. This is different from quotation, which

has the same words (as well as the same meaning). As the words have been changed, a paraphrase should not use quotation marks («…»).

Summary differs from paraphrase in that a summary is shorter than the original, whereas a paraphrase is the same length.

When you paraphrase another writer’s ideas, you will need to use

in-text citations to acknowledge the source

(this is the same for all three ways of using another writer’s work). The following table summarises these points.

| Quotation | Paraphrase | Summary | |

| Same words as original | |||

| Same length as original | |||

| Uses » « | |||

| Uses in-text citations |

Why paraphrase?

Effective paraphrasing is essential in order to avoid

plagiarism.

A mistake many beginning academic writers make is to change a few but

not enough of the words, leaving copied chunks from the original — so it is part paraphrase, part quotation, but without quotation marks

(and therefore stealing a writer’s words).

Avoiding plagiarism, however, is not the main aim of paraphrasing. As mentioned above, there are three ways to use another writer’s work in your own:

quotation, paraphrase and summary. Paraphrase is the most common of the three. It is usually favoured over quotation for two reasons: first,

it allows you to demonstrate understanding of the original work; and second, it allows you to integrate

the idea into your own writing. Although using quotation is easier, especially for beginning writers, most university lecturers will tell you to use

quotation sparingly, and to use paraphrase or summary more frequently. Paraphrase is favoured over summary because it allows you to keep

the full meaning of the original text, rather than just stating the main points.

While paraphrasing is an important skill in itself, it is also a part of

writing a summary, as when you write a summary

you still need to change the writer’s words. It is also recommended that you use paraphrasing when

reading and note-taking

(although many students do not, and prefer to paraphrase later, when using their notes). These are additional reasons why

learning how to paraphrase is important in your academic study.

How to paraphrase

A good paraphrase is different from the wording of the original, without altering the meaning. There

are three

vocabulary techniques you will need to use in order to achieve this, with good paraphrasing employing a

mix of all three. They are:

- changing words;

- changing word forms;

- changing word order.

The skill of paraphrase is another reason why it is important to understand more than just the meaning of a word, but also know its

different word forms.

Below are two different examples of paraphrase, with an explanation of how each original text has been changed.

Original text 1, from Pears and Shields (2013, p.113)

Paraphrase: A restating of someone else’s thoughts or ideas in your own words.

Paraphrase of text 1

Paraphrasing is a restatement of another person’s ideas or thoughts using your own words.

In this example, the following changes have been made:

- Paraphrase ⇒ Paraphrasing (change word form)

- restating ⇒ restatement (change word form)

- someone else’s ⇒ another person’s (change words)

- thoughts or ideas ⇒ ideas or thoughts (change word order)

- in ⇒ using (change word)

Original text 2, from Bailey (2000, p.21)

Paraphrasing involves changing a text so that it is quite dissimilar to the source yet retains all the meaning.

Paraphrase of text 2

Paraphrase requires a text to be altered in a way which makes it different from the original while keeping the same meaning.

In this example, the following changes have been made:

- Paraphrasing ⇒ Paraphrase (change word form)

- involves ⇒ requires (change word)

- changing a text ⇒ a text to be altered (change word order)

- changing ⇒ altered (change word)

- so that it is ⇒ in a way which makes it (change words)

- dissimilar to ⇒ different from (change words)

- the source ⇒ the original (change words)

- yet retains all the meaning ⇒ while keeping the same meaning (change words)

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres.

Checklist

Below is a checklist for paraphrasing. Use it to check your own paraphrasing, or get a peer (another student) to help you.

| Area | Details | OK? | Note/comment |

| Paraphrasing skills | The text has been changed in several ways (changed words, changed word forms, changed word order). | ||

| The text has been changed enough to avoid plagiarism (no copied chunks). | |||

| Referencing skills | The paraphrase includes an in-text citation for the source text. | ||

| Meaning | The meaning of the text is the same as the original. | ||

| Length | The length of the text is about the same as the original. |

References

Bailey, S. (2000). Academic Writing. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer

Pears, R. and Shields, G. (2013). Cite them right: The essential guide to referencing (9th ed.), Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is when you take an original idea and re-write it to express the same meaning but in a different way. This might be by changing words, word forms, sentence structure, or using synonyms. If you think this is just for writing academic papers, think again. We actually paraphrase all the time!

When you read a book, article, or watch a movie and tell your friends about it, you are paraphrasing. When you tell your friend or colleague about a conversation you had with your boss, you are paraphrasing. You are not repeating the original conversation word for word. You are giving them the main idea of the conversation using your own words.

IELTS Writing Task 2: Why do you need to paraphrase?

Paraphrasing is important to the IELTS writing task 2 because your introduction paragraph is basically a paraphrase of the essay prompt. You will need to re-write the essay prompt in your own words to introduce your essay.

Watch Jay break down the IELTS writing task 2 introduction right here:

Three ways how do paraphrasing for IELTS writing task 2

Before you attempt to paraphrase, you need to make sure that you understand the gist, or meaning of the paragraph. Paraphrasing is more than just changing words. Your paraphrase needs to make sense and still convey the original message. So, you should read the original text a couple of times to make sure you understand the message it conveys. Then turn the ideas over in your mind. Think of how you would express the same ideas to a friend.

Below are three techniques to paraphrase. Rather than exclusively using one of them, a good paraphrase includes all methods.

- Use synonyms

Synonyms are different words that express the same or similar meaning.

For example: Interesting, fascinating, curious and amusing are all synonyms.

But! Some synonyms can have a slightly different meaning. For example, fascinating has a stronger meaning than interesting. So be careful when using synonyms. We need to make sure that the words we are using convey the same level of meaning as the original.

Example:

Original: Many people think that cars should not be allowed in city centres.

Paraphrase: Many people believe that motor vehicles should be banned in urban areas.

*Synonyms

think –> believe

cars –> motor vehicles

should not be allowed –> should be banned

city centres –> urban areas

- Change the word forms

Another way to paraphrase is to change word forms. For example, changing a noun into a verb, a verb into a noun or an adjective into a noun or vice versa.

Example:

Original: Many people find watching tennis interesting (interesting = adjective).

Paraphrase: Many people have an interest in watching tennis (interest = noun).

Example:

Original: Some people think Facebook is an invasion of privacy (invasion = noun).

Paraphrase: Some people think Facebook has invaded our privacy (has invaded = verb).

- Change the sentence structure

A third way to paraphrase is to change sentence structure. This could be by changing the sentence from passive to active or vice versa, or changing the order of the clauses. Let’s have a look.

Active to Passive

Original: The hurricane destroyed the city.

Paraphrase: The city was destroyed by the hurricane.

In the sentence above, the subject (the hurricane) became the object, and the object (the city) became the subject.

To be passive, we also changed the verb destroyed into past perfect (was/were + past participle).

Passive to Active

Original: The public transport system was developed by the city council.

Paraphrase: The city council developed the public transport system.

In the sentence above the subject (the public transport system) became the object, and the object (the city council) became the subject.

Order of clauses

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. Some sentences can be a single clause. Some sentences can be made up of two or more clauses.

For example: It is difficult to say whether the economy will improve.

The two clauses are: It is difficult to say / whether the economy will improve.

One way to paraphrase is by changing the order of the clauses.

For example: Whether the economy will improve, it is difficult to say.

Let’s look at another example:

Original: During the summer, many people visit the temple.

Paraphrase: Many people visit the temple during the summer.

Paraphrasing an essay prompt to write your introduction

In IELTS Writing Task 2, you write your introduction by paraphrasing the essay prompt. In order to do this, you will need to unpack or break the essay prompt into parts. Usually, an essay prompt consists of three parts:

A general statement that introduces the topic

A specific statement that gives you the specific idea about the topic

Finally, your instructions/question

Let’s look at an example:

Nowadays, more and more foreign students are going to English-speaking countries to learn the international language – English. It is undoubtedly true that studying English in an English-speaking country is the best way, but it is not the only way to learn it. Do you agree or disagree with the above statement?

To unpack this prompt, the first sentence is the general statement. Nowadays, more and more foreign students are going to English-speaking countries to learn the international language – English. This tells us what the essay topic is.

The second sentence is the specific statement. It is undoubtedly true that studying English in an English-speaking country is the best way, but it is not the only way to learn it. It gives an opinion about the topic.

The third sentence is the question. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the above statement? This means you have to express your opinion on the second sentence.

So! In order to write your introduction, you need to paraphrase the three parts of this essay prompt.

Let’s look at an example of a paraphrase of each:

Sentence 1: Nowadays, more and more foreign students are going to English-speaking countries to learn the international language – English

Paraphrase: In recent times, a growing number of international students are learning English in English-speaking countries.

Sentence 2: It is undoubtedly true that studying English in an English-speaking country is the best way, but it is not the only way to learn it.

Paraphrase: Although it is beneficial to learn English in a country where it is natively spoken, there are other effective ways to learn it.

Sentence 3: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the above statement?

Paraphrase: I agree with this statement to a large degree.

Putting it all together:

Original (essay prompt): Nowadays, more and more foreign students are going to English-Speaking countries to learn the “international language – English”. It is undoubtedly true that studying English in an English-speaking country is the best way, but it is not the only way to learn it. Do you agree or disagree with the above statement?

Paraphrase (introduction): In recent times, a growing number of international students are learning English in English-speaking countries. Although it is most beneficial to learn English in a country where it is natively spoken, there are other effective ways to learn it. I agree with this statement to a large degree.

Practice

Using a combination of the above techniques (synonyms, word forms, sentence structure), write an introduction to the following essay by paraphrasing the prompt below.

The overuse of natural resources ultimately exhausts them. This causes huge harm to the environment. Therefore, the government should discourage people from overusing such resources. To what extent do you support or oppose this idea?

There are three possible correct answers:

Click here to show/hide answer 1

Exploiting natural resources will ultimately deplete them and lead to environmental harm. Therefore, the overuse of these resources should be discouraged by governments. I totally agree with this statement.

Click here to show/hide answer 2

The exploitation of natural resources results in their exhaustion. This causes environmental damage. Thus, governments should encourage people to take care not to overuse these resources. I agree with this to a large extent.

Click here to show/hide answer 3

Natural resources will ultimately be exhausted if we continue to overuse them. It damages the environment and should therefore be discouraged by governments. I agree with this statement to a large degree.

So, more than one paraphrase can be correct. There are many ways to say the same thing. There is also more than one way to paraphrase. The best way to paraphrase for IELTS Writing Task 2 is to use a combination of these techniques (synonyms, sentence structure and clause order).

Practice makes perfect!

Our E2Language IELTS experts can help you learn the rest of the method for IELTS Writing Task 2!

Jamal Abilmona is an expert IELTS teacher, curriculum designer and language buff. She has taught English for general and academic purposes in classrooms around the world and currently writes e-learning material for E2Language.com, providing online IELTS preparation for students all around the world.

.

Write paraphrases without looking at the source text, and avoid synonym-substitution

DEFINITION AND USES OF PARAPHRASE

To paraphrase is to change one’s own or someone else’s wording without changing what it means. The related noun paraphrase may be uncountable, meaning “making a paraphrase”, or countable, meaning “paraphrased wording” (see 14. Action Outcomes). The idea of changing “wording” should not be confused with that of changing “words”. Wording involves not just words but also word order, sentence structure and sentence divisions (see 236. Tricky Word Contrasts 9, #5). It is possible, for example, to paraphrase one sentence as two or just a part of one.

Paraphrase is useful in various ways. One that is familiar to many students is reporting (with a suitable academic reference) what another writer has said. This is an alternative to quotation, and much more common, being preferred unless there is a good reason for keeping the exact original, such as clever, concise or ambiguous wording (see 79. Fitting Quotations into a Text and 127. When to Use Indirect Speech).

Other uses of paraphrase relate to one’s own wording rather than someone else’s. We might want to modify what we have written to reduce its word count or to make it sound better (e.g. less repetitious or more formal: see 265. The Importance of Grammar in Writing). We might want to repeat something with a paraphrase to assist the reader’s understanding (see 286. Repeating in Different Words). In speaking, when we are uncertain about a particular word or grammatical structure, paraphrasing it enables it to be avoided altogether. Doing this may be fundamental to the successful acquisition of a new language (see 202. Some Strategies for Learning English, Practice Strategy #2).

Successful paraphrase has two major requirements: keeping faithful to the original meaning and changing the wording in the right way. This post offers advice in both of these areas.

.

THE DANGER OF CHANGING THE MEANING

The fundamental requirement for preserving the exact meaning of a source text is to properly comprehend it. This seems obvious, but is sometimes forgotten because paraphrase is generally thought of as a writing skill rather than a reading one. All of the reading posts within this blog are useful towards this end, but one that I would single out for special mention here is taking account of every word in a text, recognising that not doing so can drastically alter the understood meaning (see 15. Half-Read Sentences). What this means for paraphrases is that they must convey the meanings of all the words in the source text (and no extra ones).

It is also important to prevent our expectations about a topic from blinding us to what a source text actually says. Expectations have a very powerful effect on our perceptions. Consider the following sentence and its supposed paraphrase:

(a) Physical strength differs in men and women.

(b) Men are physically stronger than women.

Sentence (b), the attempted paraphrase, speaks of something that is not present in (a): the greater physical strength of men. All that sentence (a) mentions is a difference of physical strength, leaving it unclear whether men are stronger than women or women are stronger than men. The likelihood is that someone paraphrasing (a) with (b) has done so because the topic of gender strength always triggers thoughts of greater male strength, and these thoughts have blinded them to what (a) actually says.

.

STEPS IN PARAPHRASING

The main paraphrase steps might be listed as (1) Read and understand, (2) Remove the source text, (3) Try to recall what has been understood, and (4) Put the recalled message – not the words – into writing. The main problem is escaping from the original words.

A key factor is the length of the original text. If it is great, the exact wording will almost certainly disappear at the recall stage, since remembering its message will take up all of our mental capacity¹. Even if we make notes on a long text to help us remember it, we should still be able to derive a good paraphrase from them because notes are of their nature so different from continuous prose (see 158. Abbreviated Sentences).

On the other hand, if the original text is very short, remembering its wording is much more likely. It is this problem of paraphrasing still-remembered wording that I want to focus on here, not least because suggesting a solution involves discussing grammar and vocabulary. The starting point is the importance of not simply replacing individual words with suitable synonyms.

There are two good reasons for avoiding synonym-substitution. The first is that it does not prove comprehension of the source text: anyone can use a translation dictionary to find a synonym of a particular word in a text they do not understand. The second problem with synonym-substitution is that it easily results in inaccurate paraphrase or incorrect-sounding English, because synonyms are rarely exactly equivalent to each other (see 5. Repetition with Synonyms and 16. Ways of Distinguishing Similar Words).

One common feature of good paraphrase is word substitutes that differ not so much in their spelling as in their grammatical class. Consider the following sentence and possible paraphrase:

(c) Jazz has always been popular.

(d) Jazz has never lost popularity.

Changing the adjective popular into its related noun popularity has other effects on the sentence. The verb been in (c) becomes no longer logical and needs to be exchanged for one that is. There are various possibilities, such as kept and enjoyed, but I have preferred the very typical partner verb lost, changing always into never to accommodate it. For more about typical partner verbs, see 273. Verb-Object Collocations.

Another way to paraphrase without simple word substitution is to reposition words in a sentence. For example, sentence (c) could be rewritten with the idea of “popular” at the start. Since adjectives rarely start sentences, it is easier again to use popularity, producing The popularity of jazz…. There are various ways of continuing: …has always existed or …has never been lost or …has been constant. I prefer the last because it is briefer and uses an adjective (constant) to paraphrase an adverb (always).

A third type of paraphrase expresses a grammatical meaning in a non-grammatical way (or vice versa). Grammatical meanings are typically expressed either by letters added to words, such as comparative –er and plural -s, or by words considered by grammarians to belong more to grammar than to vocabulary, such as than or so that or because of. An example of this kind of substitution is replacement of -er by relatively, as in relatively large instead of larger. For a range of possibilities in this area, see 298. Grammar Meanings without Grammar.

These three types of paraphrase – changing word classes, changing sentence positions and changing grammatical expressions – provide a blueprint for paraphrasing short texts acceptably. This is to start by asking for each type which words in the text it might be applied to. Actually thinking out how individual words might be changed is very likely to suggest how the rest of the sentence could be worded.

In addition to trying to create paraphrases, reading ready-made ones may be a helpful strategy. In this blog there are plenty of examples. Particularly notable posts in this respect are on examples, passive verbs, consequences, similarities, differences, importance, time duration and exceptions. There are also posts on finding alternatives to prepositions and adjectives.

To gain some appreciation of how able you already are to paraphrase in the appropriate way, try the following practice exercise.

.

PRACTICE EXERCISE (SENTENCE-LENGTH PARAPHRASE)

Each question in this exercise gives you one complete sentence and the beginnings of three paraphrases to complete. Answers are suggested afterwards.

.

.

1. Physics and Chemistry have certain similarities.

(a) Physics is …

(b) Certain …

(c) There are …

.

2. Very few people live for more than 100 years.

(a) Living …

(b) The number …

(c) The human life span…

.

3. It is many years since the moon landing.

(a) Since …

(b) The moon …

(c) There has not …

.

4. The greatest challenge in note-taking is identifying main ideas.

(a) There is no greater …

(b) Note-taking …

(c) It is particularly …

.

.

Suggested Answers (alternatives are possible)

.

1(a) Physics is similar to Chemistry in certain respects (not “aspects” – see 81. Tricky Word Contrasts 2).

1(b) Certain similarities exist between Physics and Chemistry.

1(c) There are certain similarities between Physics and Chemistry.

2(a) Living beyond 100 years is very unusual.

2(b) The number of people who live beyond 100 years is very small.

2(c) The human life span very rarely exceeds 100 years.

3(a) Since the moon landing, many years have passed.

3(b) The moon landing happened many years ago.

3(c) There has not been a moon landing for many years.

4(a) There is no greater challenge in note-taking than identifying main ideas.

4(b) Note-taking presents no greater challenge than identifying main ideas.

4(c) It is particularly challenging in note-taking to identify main ideas. (see 103. Commenting with “It” on a Later Verb)

.

¹See Bransford, J.D. and Franks, J.J. (1971). The Abstraction of Linguistic Ideas. Cognitive Psychology 2, 331-350.

Published on

April 8, 2022

by

Courtney Gahan

and

Jack Caulfield.

Revised on

November 4, 2022.

Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas into your own words. Paraphrasing a source involves changing the wording while preserving the original meaning.

Paraphrasing is an alternative to quoting (copying someone’s exact words and putting them in quotation marks). In academic writing, it’s usually better to integrate sources by paraphrasing instead of quoting. It shows that you have understood the source, reads more smoothly, and keeps your own voice front and center.

Every time you paraphrase, it’s important to cite the source. Also take care not to use wording that is too similar to the original. Otherwise, you could be at risk of committing plagiarism.

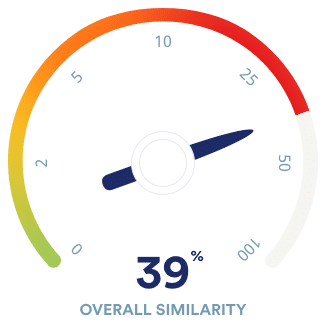

What is your plagiarism score?

Compare your paper with 99.3 billion webpages and 8 million publications.

- Best plagiarism checker of 2021

- Plagiarism report & percentage

- Largest plagiarism database

Scribbr Plagiarism Checker

Table of contents

- How to paraphrase in five easy steps

- How to paraphrase correctly

- Examples of paraphrasing

- How to cite a paraphrase

- Paraphrasing vs. quoting

- Paraphrasing vs. summarizing

- Avoiding plagiarism when you paraphrase

- Frequently asked questions about paraphrasing

How to paraphrase in five easy steps

If you’re struggling to get to grips with the process of paraphrasing, check out our easy step-by-step guide in the video below.

How to paraphrase correctly

Putting an idea into your own words can be easier said than done. Let’s say you want to paraphrase the text below, about population decline in a particular species of sea snails.

Incorrect paraphrasing

You might make a first attempt to paraphrase it by swapping out a few words for synonyms.

Like other sea creatures inhabiting the vicinity of highly populated coasts, horse conchs have lost substantial territory to advancement and contamination, including preferred breeding grounds along mud flats and seagrass beds. Their Gulf home is also heating up due to global warming, which scientists think further puts pressure on the creatures, predicated upon the harmful effects extra warmth has on other large mollusks (Barnett, 2022).

This attempt at paraphrasing doesn’t change the sentence structure or order of information, only some of the word choices. And the synonyms chosen are poor:

- “Advancement and contamination” doesn’t really convey the same meaning as “development and pollution.”

- Sometimes the changes make the tone less academic: “home” for “habitat” and “sea creatures” for “marine animals.”

- Adding phrases like “inhabiting the vicinity of” and “puts pressure on” makes the text needlessly long-winded.

- Global warming is related to climate change, but they don’t mean exactly the same thing.

Because of this, the text reads awkwardly, is longer than it needs to be, and remains too close to the original phrasing. This means you risk being accused of plagiarism.

Correct paraphrasing

Let’s look at a more effective way of paraphrasing the same text.

Here, we’ve:

- Only included the information that’s relevant to our argument (note that the paraphrase is shorter than the original)

- Introduced the information with the signal phrase “Scientists believe that …”

- Retained key terms like “development and pollution,” since changing them could alter the meaning

- Structured sentences in our own way instead of copying the structure of the original

- Started from a different point, presenting information in a different order

Because of this, we’re able to clearly convey the relevant information from the source without sticking too close to the original phrasing.

What is your plagiarism score?

Compare your paper with 99.3 billion webpages and 8 million publications.

- Best plagiarism checker of 2021

- Plagiarism report & percentage

- Largest plagiarism database

Scribbr Plagiarism Checker

Examples of paraphrasing

Explore the tabs below to see examples of paraphrasing in action.

| Source text | Paraphrase |

|---|---|

| “The current research extends the previous work by revealing that listening to moral dilemmas could elicit a FLE [foreign-language effect] in highly proficient bilinguals. … Here, it has been demonstrated that hearing a foreign language can even influence moral decision making, and namely promote more utilitarian-type decisions” (Brouwer, 2019, p. 874). | The research of Brouwer (2019, p. 874) suggests that the foreign-language effect can occur even among highly proficient bilinguals, influencing their moral decision making, when auditory (rather than written) prompting is given. |

| Source text | Paraphrase |

|---|---|

| “The Environmental Protection Agency on Tuesday proposed to ban chrysotile asbestos, the most common form of the toxic mineral still used in the United States. … Chlorine manufacturers and companies that make vehicle braking systems and sheet gaskets still import chrysotile asbestos and use it to manufacture new products.

“The proposed rule would ban all manufacturing, processing, importation and commercial distribution of six categories of products containing chrysotile asbestos, which agency officials said would cover all of its current uses in the United States” (Phillips, 2022). |

Chrysotile asbestos, which is used to manufacture chlorine, sheet gaskets, and braking systems, may soon be banned by the Environmental Protection Agency. The proposed ban would prevent it from being imported into, manufactured in, or processed in the United States (Phillips, 2022). |

| Source text | Paraphrase |

|---|---|

| “The concept of secrecy might evoke an image of two people in conversation, with one person actively concealing from the other. Yet, such concealment is actually uncommon. It is far more common to ruminate on our secrets. It is our tendency to mind-wander to our secrets that seems most harmful to well-being. Simply thinking about a secret can make us feel inauthentic. Having a secret return to mind, time and time again, can be tiring. When we think of a secret, it can make us feel isolated and alone” (Slepian, 2019). | Research suggests that, while keeping secrets from others is indeed stressful, this may have little to do with the act of hiding information itself. Rather, the act of ruminating on one’s secrets is what leads to feelings of fatigue, inauthenticity, and isolation (Slepian, 2019). |

How to cite a paraphrase

Once you have your perfectly paraphrased text, you need to ensure you credit the original author. You’ll always paraphrase sources in the same way, but you’ll have to use a different type of in-text citation depending on what citation style you follow.

| APA in-text citation | (Brouwer, 2019, p. 874) |

|---|---|

| MLA in-text citation | (Brouwer 874) |

| Chicago footnote | 1. Susanne Brouwer, “The Auditory Foreign-Language Effect of Moral Decision Making in Highly Proficient Bilinguals,” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40, no. 10 (2019): 874. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1585863. |

Generate accurate citations with Scribbr

Paraphrasing vs. quoting

It’s a good idea to paraphrase instead of quoting in most cases because:

- Paraphrasing shows that you fully understand the meaning of a text

- Your own voice remains dominant throughout your paper

- Quotes reduce the readability of your text

But that doesn’t mean you should never quote. Quotes are appropriate when:

- Giving a precise definition

- Saying something about the author’s language or style (e.g., in a literary analysis paper)

- Providing evidence in support of an argument

- Critiquing or analyzing a specific claim

Paraphrasing vs. summarizing

A paraphrase puts a specific passage into your own words. It’s typically a similar length to the original text, or slightly shorter.

When you boil a longer piece of writing down to the key points, so that the result is a lot shorter than the original, this is called summarizing.

Paraphrasing and quoting are important tools for presenting specific information from sources. But if the information you want to include is more general (e.g., the overarching argument of a whole article), summarizing is more appropriate.

Martin (2016) argues it is important to consider the impact of human architecture on the evolution of other species. Stating that the indoor biome—the realm of species that live and reproduce largely inside human-built structures—represents an understudied area for ecologists, Martin makes the case for studying this biome as an essential way of understanding the world of the Anthropocene.

Avoiding plagiarism when you paraphrase

When paraphrasing, you have to be careful to avoid accidental plagiarism.

This can happen if the paraphrase is too similar to the original quote, with phrases or whole sentences that are identical (and should therefore be in quotation marks). It can also happen if you fail to properly cite the source.

Paraphrasing tools are widely used by students, and can be especially useful for non-native speakers who may find academic writing particularly challenging. While these can be helpful for a bit of extra inspiration, use these tools sparingly, keeping academic integrity in mind.

To make sure you’ve properly paraphrased and cited all your sources, you could elect to run a plagiarism check before submitting your paper. And of course, always be sure to read your source material yourself and take the first stab at paraphrasing on your own.

Check out our research on the best plagiarism checkers in 2022, or check out Scribbr’s free plagiarism checker that came best out of the test.

Frequently asked questions about paraphrasing

-

How do I paraphrase effectively?

-

To paraphrase effectively, don’t just take the original sentence and swap out some of the words for synonyms. Instead, try:

- Reformulating the sentence (e.g., change active to passive, or start from a different point)

- Combining information from multiple sentences into one

- Leaving out information from the original that isn’t relevant to your point

- Using synonyms where they don’t distort the meaning

The main point is to ensure you don’t just copy the structure of the original text, but instead reformulate the idea in your own words.

-

What is the difference between plagiarism and paraphrasing?

-

Plagiarism means using someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own. Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas in your own words.

So when does paraphrasing count as plagiarism?

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if you don’t properly credit the original author.

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if your text is too close to the original wording (even if you cite the source). If you directly copy a sentence or phrase, you should quote it instead.

- Paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you put the author’s ideas completely in your own words and properly cite the source.

-

When should I quote instead of paraphrasing?

-

To present information from other sources in academic writing, it’s best to paraphrase in most cases. This shows that you’ve understood the ideas you’re discussing and incorporates them into your text smoothly.

It’s appropriate to quote when:

- Changing the phrasing would distort the meaning of the original text

- You want to discuss the author’s language choices (e.g., in literary analysis)

- You’re presenting a precise definition

- You’re looking in depth at a specific claim

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Gahan, C.

& Caulfield, J.

(2022, November 04). How to Paraphrase | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr.

Retrieved April 14, 2023,

from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/how-to-paraphrase/

Is this article helpful?

You have already voted. Thanks

Your vote is saved

Processing your vote…