Terms that sound identical and also have similar meanings can be difficult to manage. The words «censor» and «censure» are examples of such terms. But when you throw in one more term into the mix, things get even more confusing.

«Censure» means «to reprimand». «Censor» is removing «offensive», «obscene» aspects from a piece of work meant for public consumption. And «sensor» denotes any piece of tech built into cameras, detectors, etc. «Censure» and «censor» work as both nouns and verbs in texts. «Sensor» is primarily a noun.

If you’d like to learn more about the differences between the three words, how to use them in various writing contexts, and more, continue reading.

«Censure» – Definition

The term «censure» means to «officially denounce» or «speak against someone». It’s basically «official displeasure» or «formal rebuke». An individual can be «censured» for their actions or even their words. The term «censure», and also «censor», come from «censere», a Latin term that means «judge» or «appraise».

The synonyms or related words for «censure» include:

- criticize

- reprehend

- reprobate

- denounce

- condemn

Unlike the above words, however, «censure» implies «authority» and «reprimanding». It invariably denotes «official action».

«Censor» – Definition

«Censoring» or «to censor» a piece of writing or speech is «suppressing inappropriate work» so that it doesn’t become available to the public in its «raw» form. Bleeping «expletives» or «obscenities» on national television is a form of censoring broadcasters resort to. Not to mention, the noun «censorship» is based on «censor».

According to The Free Dictionary by Farlex, the term «censor» originally served as a noun, referring to «magistrates overseeing and upholding moral standards». Over a period, the word evolved to mean an individual or entity with authority to examine different forms of media, such as movies, books, plays, etc., and clean up or quash obscene, vulgar, or any other form of objectionable content.

A «censor» is typically a body or entity instituted and/or governed by the state. The body consists of individuals who have the government’s permission to read publications, watch movies or theatrical performances, etc., before they are made public.

As they are set in place by the ruling government, they usually tend to adhere to the state’s requirements or expectations. If a movie or book consists of something that’s not deemed «acceptable» by the state, the piece of work is likely to be censored heavily or not allowed to be released at all.

«Sensor» – Definition

A «sensor» is any device that measures or detects a physical property and indicates, documents, or responds to the thing. Digital cameras have sensors built in them, for instance, which help snap images and record videos. Metal detectors also have sensors. Not to mention, the noun «sensor» comes from «sense». The term is derived from the Latin word «sentire», which means «to feel».

Most modern-day sensors are «digital», producing data for subsequent computer processing. Analog sensors, however, exist too. The sensors used in smoke detectors, for instance, are analog. The sensor found in the detector is radioactive material positioned between a couple of electrically charged plates.

The arrangement helps ionize the air, causing current flow between the two plates. When smoke penetrates the chamber, the light gets reflected onto the sensor, causing the alarm to trigger. The motion detectors used to automatically open public building doors also employ analog sensors.

Using «Censure», «Censor», and «Sensor» in Texts

The words «censure» and «censor» can be used as a verb or a noun in writings. «Sensor» is typically used as a noun in sentences.

When used as a verb, «censor» means to examine a particular thing and remove portions of it perceived to be «inappropriate», «offensive», etc.

- Tim’s job was censoring cuss words on television shows.

The following sentence employs «censor» as a noun:

- The beach censors were found arresting scantily clad women.

Like «censor», «censure» can also be employed as a noun or a verb. When employed as a verb, «censure» means «to criticize or speak out against something». The word is invariably used formally and not so much in casual conversations.

- The judge censured him for his careless behavior.

When incorporated as a noun, the word denotes «official criticism». A «censure» is usually a component of punishment.

- He received censure from his manager for checking out Instagram at work.

- If she gets another censure, she will lose her job.

The term «sensor» is almost always used as a noun. Example sentences mentioned below illustrate the point.

Similarities and the Ensuing Confusion Between «Censure», «Censor», and «Sensor»

The three words «censure», «censor», and «sensor» sound almost identical when pronounced, and they have relatively similar spellings too. This tends to cause confusion when using the words in sentences, particularly when trying to choose between «censor» and «sensor».

Errors entailing «censure» or incorrectly using the word in place of «censor» or «sensor» are comparatively rare. This is because «censure» has a slight yet distinct difference in pronunciation compared to «censor» and «sensor».

The words «censor» and «sensor» are pronounced as «SEN-ser». «Censure», on the other hand, is pronounced as «SEN-shire», which rhymes with «sure».

About their meanings, «censor» and «censure» are similar to each other. A «censor» basically cuts or hides information considered «offensive», «harsh», or «obscene». A «censure», on the flip side, deals with «harsh criticism». Both entail assessing, judging, and/or reflecting on other’s work.

When a piece of work is not «censored» properly or is out for the general public to consume, the «censor» is likely to be «censured».

Kindly note, «censer» and «censor» are not the same, or they do not belong to different dialects of English. «Censer» is a valid word and not a misspelling of «censor». It denotes «incense burners» used in a church.

Distinguishing Between «Censure», «Censor», and «Sensor»

The key to differentiating the three terms from each other is focusing on their roots and meanings. As mentioned above, «sensor» is derived from «sense». If the word to be used has to do with «sensing», «sensor» is likely the word. If not, use «censor».

Think of the term «census» for «censure» and «censor». All of the three begin with «c». If you’re having trouble drawing the line between «censure» and «censor», focus on the suffixes. In other words, the «-or» in the word «censor» denotes an individual or entity that resorts to certain actions. Most importantly, only «censor» can be used to denote a person.

The «-ure» in the term «censure», on the other hand, denotes the outcome of an act that aligns with the meaning of that word, which is «a kind of punishment».

Example Sentences with the Word «Censure»

Here is a list of sentences that use «censure» to good effect:

- If you want to become famous and loved, you should be ready for censure too.

- The fear of censure is a sign you will not make it big.

- The commandant had written them three letters of censure.

- To avoid being censured by others, self-correcting whenever possible is imperative.

- Following the review, the commission concluded no censure was needed.

- After the censuring, the professor was seriously contemplating early retirement.

- He was not censured or punished for his alleged role in the scandal.

- The board censured the manager but did not dismiss him.

Example Sentences with the Word «Censor»

The following are sentences with the word «censor» and the different inflections of the term. As mentioned above, «censorship’ has its roots in «censor», and, therefore, a sentence or two incorporating the word could be included below.

- Unlike nudity, violence in films is not as heavily criticized or censored.

- She speaks her mind without any filter or censor.

- The censor deleted multiple paragraphs from the book.

- Unlike movies, museums do not have official censorships.

- History is proof that efforts to censor communication at a macro level never succeed.

- The film was never released outside its home country, thanks to the state’s censor board.

- The book was censored heavily during its initial release, only to be republished in its original avatar a year later.

- It was only later found out that the upper management heavily censored the employee’s reports.

- The director was not in favor of a small group of random people censoring his movie.

- The government has censored all files containing information on aliens.

- Despite many countries’ attempts to censor the work, it still turned out to be a roaring success worldwide.

Example Sentences with the Word «Sensor»

The following are sentences incorporating the word «sensor»:

- To prevent crime, better and more surveillance cameras and sensors must be instituted.

- The infrared sensor was devised to detect movement.

- The clothing company makes shirts with built-in sensors.

- Almost all smartphones come with sensors, which determine how bright the screens should get in relation to their environment or how they are used.

- Electromagnetic radiation caused disruptions in the spacecraft’s sensor.

- The security system has a network of motion and heat sensors that help detect intruders.

- Modern airplanes are automated in large part, courtesy of the many advanced sensors built in them.

Conclusion

«Censor» and «sensor» are homonyms, and they are likely to create confusion among many writers. The term «censure», on the other hand, has a slightly different sound and unique spelling too, which reduces the chances of getting the word mixed up with «sensor» or «censor».

But there is still room for confusion with «censure», and it’s, therefore, imperative to address the same. You don’t want to «censor» somebody when the objective was to «censure» them.

Shawn Manaher is the founder and CEO of The Content Authority. He’s one part content manager, one part writing ninja organizer, and two parts leader of top content creators. You don’t even want to know what he calls pancakes.

Asked by: Elvie Prohaska

Score: 4.4/5

(24 votes)

One that condemns or censures.

What does it mean for a person to be censored?

If someone in authority censors letters or the media, they officially examine them and cut out any information that is regarded as secret.

What censer means?

: a vessel for burning incense especially : a covered incense burner swung on chains in a religious ritual.

What does non censored mean?

a : not having any part deleted or suppressed an uncensored version of the film. b : not subject to a censor’s examination uncensored email.

What is censorship Webster dictionary?

1a : the institution, system, or practice of censoring They oppose government censorship. b : the actions or practices of censors especially : censorial control exercised repressively censorship that has …

19 related questions found

What is censorship in simple words?

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or «inconvenient».

What is censorship dictionary?

Censorship blocks something from being read, heard, or seen. … To «censor» is to review something and to choose to remove or hide parts of it that are considered unacceptable. Censorship is the name for the process or idea of keeping things like obscene word or graphic images from an audience.

What does vigilante unit mean?

: a member of a group of volunteers who are not police but who decide on their own to stop crime and punish criminals. More from Merriam-Webster on vigilante.

What does the word censer mean in the Bible?

a container, usually covered, in which incense is burned, especially during religious services; thurible.

What does a vestment mean?

1a : an outer garment especially : a robe of ceremony or office. b vestments ˈves(t)-mənts plural : clothing, garb. 2 : a covering resembling a garment.

How do censers work?

Liturgical Censing is the practice of swinging a censer suspended from chains towards something or someone, typically an icon or person, so that smoke from the burning incense travels in that direction. Burning incense represents the prayers of the church rising towards Heaven.

What is censorship Class 9?

Censorship is the practice of curtailment of communication on the censor’s belief that it’s objectionable to its constituency. Censorship means someone else gets to choose what you are allowed to read, learn, see, hear, or express. … Censorship is a means to control others and limit their freedom.

What is Abyss in the Bible?

In the Bible, the abyss is an unfathomably deep or boundless place. The term comes from the Greek ἄβυσσος, meaning bottomless, unfathomable, boundless. It is used as both an adjective and a noun. It appears in the Septuagint, the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and in the New Testament.

What does the Bible say about Day of Atonement?

The main description of the Day of Atonement is found in Leviticus 16:8-34. Additional regulations pertaining to the feast are outlined in Leviticus 23:26-32 and Numbers 29:7-11. In the New Testament, the Day of Atonement is mentioned in Acts 27:9, where some Bible versions refer to as «the Fast.»

What the Bible Says About incense?

In the Hebrew Bible

The sacred incense prescribed for use in the wilderness Tabernacle was made of costly materials that the congregation contributed (Exodus 25:1, 2, 6; 35:4, 5, 8, 27-29). The Book of Exodus describes the recipe: … Every morning and evening the sacred incense was burned (Ex 30:7, 8; 2 Chronicles 13:11).

Is it legal to be a vigilante?

By definition, vigilantes cannot be legally justified – if they satisfied a justification defense, for example, they would not be law-breakers – but they may well be morally justified, if their aim is to provide the order and justice that the criminal justice system has failed to provide in a breach of the social …

Are there vigilantes in real life?

These real-life vigilantes include “superheroes,” militia-style organizations, and even religious protection groups. They’re the latest iteration of a long-held American fascination with vigilante justice. For the past 15 years, a shadowy figure has patrolled the streets of New York.

What type of word is censorship?

What type of word is ‘censorship’? Censorship is a noun — Word Type.

What are two meaning of censorship?

The definition of censorship is the practice of limiting access to information, ideas or books in order to prevent knowledge or freedom of thought. … Banning controversial books is an example of censorship.

Is the freedom of speech?

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, states that: Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

What is meant by self censorship?

Self-censorship is the act of censoring or classifying one’s own discourse. This is done out of fear of, or deference to, the sensibilities or preferences (actual or perceived) of others and without overt pressure from any specific party or institution of authority.

What does censorship mean in literature?

Book censorship is the act of some authority taking measures to suppress ideas and information within a book. Censorship is «the regulation of free speech and other forms of entrenched authority«. … Books are most often censored for age appropriateness, offensive language, sexual content, amongst other reasons.

Is Abyss negative word?

Yes: abyss, as in «abyssal depths» of the ocean. That’s neutral and simply means «very very deep».

| Part of a series on |

| Freedom |

| By concept |

|

Philosophical freedom |

| By form |

|---|

|

Academic |

| Other |

|

Censorship |

Censorship is the editing, removing, or otherwise changing speech and other forms of human expression. In some cases, it is exercised by governing bodies but it is always and continuously carried out by the mass media. The visible motive of censorship is often to stabilize, improve, or persuade the societal group that the censoring organization would have control over. It is most commonly applied to acts that occur in public circumstances, and most formally involves the suppression of ideas by criminalizing or regulating expression. Discussion of censorship often includes less formal means of controlling perceptions by excluding various ideas from mass communication. What is censored may range from specific words to entire concepts and it may be influenced by value systems; but the most common reasons for censoring («omitting») information are the particular interests of the distribution companies of news and entertainment, their owners, and their commercial and political connections.

While humankind remains self-centered and unable to develop a world of peace and harmonious relationships for all, censorship continues to be controversial yet necessary. Restricting freedom of speech violates the foundation of democracy, yet the imposition of offensive material on the public also violates their rights. Governments should not hide important information from their citizens, yet the public release of sensitive military or other materials endangers those citizens should such material fall into the hands of enemies.

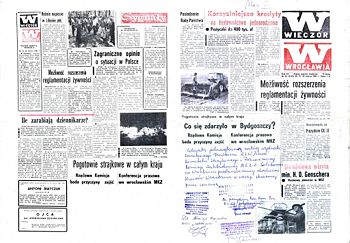

Wieczór Wrocławia» — Daily newspaper of Wrocław, People’s Republic of Poland, March 20-21-21, 1981, with censor intervention on first and last pages — under the headlines «Co zdarzyło się w Bydgoszczy?» (What happened in Bydgoszcz?) and «Pogotowie strajkowe w całym kraju» (Country-wide strike alert). The censor had removed a section regarding the strike alert; hence the workers in the printing house had decided to also blank out a second official propaganda section. The right-hand page also includes a hand-written confirmation of that decision by the local «Solidarność» (Solidarity) Trade Union.

Etymology

«Censorship» comes from the Latin word censor. In Rome, the censor had two duties: To count the citizens and to supervise their morals. The term «census» is also derived from this word.

An early published reference to the term «whitewash» dates back to 1762 in a Boston Evening Post article. In 1800, the word was used publicly in a political context, when a Philadelphia Aurora editorial said that «if you do not whitewash President Adams speedily, the Democrats, like swarms of flies, will bespatter him all over, and make you both as speckled as a dirty wall, and as black as the devil.»[1]

The word «sanitization» is a euphemism commonly used in the political context of propaganda to refer to the doctoring of information that might otherwise be perceived as incriminating, self-contradictory, controversial, or damaging. Censorship, as compared to acts or policies of sanitization, more often refers to a publicly set standard, not a privately set standard. However, censorship is often alleged when an essentially private entity, such as a corporation, regulates access to information in a communication forum that serves a significant share of the public. Official censorship might occur at any jurisdictional level within a state or nation that otherwise represents itself as opposed to formal censorship.

Selected global history

Censorship has occurred all over the world, and has been evident since recorded history in numerous societies. As noted, the word «censor» derives from the Roman duty to supervise the morals of the public.

Great Britain

One of the earliest known forms of censorship in Great Britain was the British Obscenity Laws. The conviction in 1727 of Edmund Curll for the publication of Venus in the Cloister or The Nun in her Smock under the common law offense of disturbing the King’s peace was the first conviction for obscenity in Great Britain, and set a legal precedent for other convictions.[2]British copyright laws also gave the Crown the permission to license publishing. Without government approval, printing was not allowed. For a court or other governmental body to prevent a person from speaking or publishing before the act has taken place is sometimes called prior restraint, which may be viewed as worse than punishment received after someone speaks, as in libel suits.

Russia

The Russian Empire had a branch within the government devoted to censorship (among other tasks) known as the Third Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. The Third Section and Gendarmes became associated primarily with the suppression of any liberal ideas as well as strict censorship on printed press and theater plays. Although only three periodicals were ever banned outright, most were severely edited. It was keen to repress «dangerous» western liberal ideas, such as constitutional monarchy or even republicanism. Throughout the reign of Nicholas I, thousands of citizens were kept under strict surveillance.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union also later engaged in censorship as Lenin believed literature and art could be used for ideological and political purposes.[3] Under the Soviet regime there were a number of organizations responsible for censorship. The Main Administration for Safeguarding State Secrets in the Press (also known as Glavlit) was in charge of censoring all publications and broadcasting for state secrets. There was also Goskomizdat, Goskino, Gosteleradio, and Goskomstat, which were in charge of censoring television, film, radio, and printed matter.

United States

During World War II, The American Office of Censorship, an emergency wartime agency, heavily censored reporting. On December 19, 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8985, which established the Office of Censorship and conferred on its director the power to censor international communications in «his absolute discretion.» However, the censorship was not limited to reporting. «Every letter that crossed international or U.S. territorial borders from December 1941 to August 1945 was subject to being opened and scoured for details.»[4]

East Germany

Following World War II, the Soviet controlled East Germany censored anything it could. Censors scrutinized manuscripts for their socialist ideology and recommended changes to the author if necessary. Afterwards, the whole work was again analyzed for ideology hostile to the current government by a committee of the publishing company. There existed two official government arms for censorship: Hauptverwaltung Verlage und Buchhandel (HV), and the Bureau for Copyright (Büro für Urheberrechte). The HV determined the degree of censorship and the way of publishing and marketing the work. The Bureau for Copyright appraised the work, and then decided if the publication would be allowed to be published in foreign countries as well as the GDR, or only in the GDR.

Iran

Modern Iran practices a good deal of censorship over the printed press and the internet.[5] With the election of Iranian president Mohammad Khatami, and the start of the 2nd of Khordad Reform Movement, a clampdown occurred that only worsened after the election of conservative president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005. Iran is now considered to be one of the most repressive Internet-censorship regimes in the world. Many bloggers, online activists, and technical staff have faced jail terms, harassment, and abuse. In November 2006, Iran was one of 13 countries labeled «enemies of the internet» by activist group Reporters Without Borders.[6] The government of Iran required all Iranians to register their web sites with the Ministry of art and culture.

Subject matter

The rationale for censorship is different for various types of data censored. These are the main types:

Educational censorship

The content of school textbooks is often the issue of debate, since their target audience is young people, and the term «whitewashing» is the one commonly used to refer to selective removal of critical or damaging evidence or comment. The reporting of military atrocities in history is extremely controversial, as in the case of the Nanking Massacre, the Holocaust, and the Winter Soldier Investigation of the Vietnam War. The representation of every society’s flaws or misconduct is typically downplayed in favor of a more nationalist, favorable, or patriotic view.

In the context of secondary-school education, the way facts and history are presented greatly influences the interpretation of contemporary thought, opinion, and socialization. One argument for censoring the type of information disseminated is based on the inappropriate quality of such material for the young. The use of the «inappropriate» distinction is in itself controversial, as it can lead to a slippery slope enforcing wider and more politically-motivated censorship.

Moral censorship

Moral censorship is the means by which any material that contains what the censor deems to be of questionable morality is removed. The censoring body disapproves of what it deems to be the values behind the material and limits access to it. Pornography, for example, is often censored under this rationale. In another example, graphic violence resulted in the censorship of the 1932 «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» movie entitled Scarface originally completed in 1930.

Military censorship

Book burning in 1933 in Berlin, Germany

Military censorship is the process of keeping military intelligence and tactics confidential and away from the enemy. This is used to counter espionage, which is the process of gleaning military information. Additionally, military censorship may involve a restriction on information or media coverage that can be released to the public, such as in Iraq, where the U.S. government has restricted the photographing or filming of dead soldiers or their caskets and its subsequent broadcast in the U.S. This is done to avoid public reaction similar to that which occurred during the Vietnam War or the Iran Hostage Crisis.

In wartime, explicit censorship is carried out with the intent of preventing the release of information that might be useful to an enemy. Typically it involves keeping times or locations secret, or delaying the release of information (such as an operational objective) until it is of no possible use to enemy forces. The moral issues here are often seen as somewhat different, as release of tactical information usually presents a greater risk of casualties among one’s own forces and could possibly lead to loss of the overall conflict. During World War I, letters written by British soldiers would have to go through the process of being censored. This consisted of officers going through letters with a black marker and crossing out anything which might compromise operational secrecy before the letter was sent. The World War II catchphrase «Loose lips sink ships» was used as a common justification to exercise official wartime censorship and encourage individual restraint when sharing potentially sensitive information.

Political censorship

Political censorship occurs when governments conceal secrets from their citizens. The logic is to prevent the free expression needed to revolt. Democracies do not officially approve of political censorship but often endorse it privately. Any dissent against the government is thought to be a “weakness” for the enemy to exploit. Campaign tactics are also often kept secret, leading to events such as the Watergate scandal.

A well-known example of sanitization policies comes from the USSR under Stalin, where publicly used photographs were often altered to remove people whom Stalin had condemned to execution. Though past photographs may have been remembered or kept, this deliberate and systematic alteration of history in the public mind is seen as one of the central themes of Stalinism and totalitarianism. More recently, the official exclusion of television crews from locales where coffins of military dead were in transit has been cited as a form of censorship. This particular example obviously represents an incomplete or failed form of censorship, as numerous photographs of these coffins have been printed in newspapers and magazines.

Religious censorship

Religious censorship is the means by which any material objectionable to a certain faith is removed. This often involves a dominant religion forcing limitations on less dominant ones. Alternatively, one religion may shun the works of another when they believe the content is not appropriate for their faith.

Also, some religious groups have at times attempted to block the teaching of evolution in schools, as evolutionary theory appears to contradict their religious beliefs. The teaching of sex education in school and the inclusion of information about sexual health and contraceptive practices in school textbooks is another area where suppression of information occurs.

Corporate censorship

Corporate censorship is the process by which editors in corporate media outlets intervene to halt the publishing of information that portrays their business or business partners in a negative light. Privately owned corporations in the «business» of reporting the news also sometimes refuse to distribute information due to the potential loss of advertiser revenue or shareholder value which adverse publicity may bring.

Implementation

Censorship can be explicit, as in laws passed to prevent select positions from being published or propagated (such as the People’s Republic of China, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Australia, and the United States), or it can be implicit, taking the form of intimidation by government, where people are afraid to express or support certain opinions for fear of losing their jobs, their position in society, their credibility, or their lives. The latter form is similar to McCarthyism and is prevalent in a number of countries, including the United States.

Through government action

Censorship is regarded among a majority of academics in the Western world as a typical feature of dictatorships and other authoritarian political systems. Democratic nations are represented, especially among Western government, academic, and media commentators, as having somewhat less institutionalized censorship, and as instead promoting the importance of freedom of speech. The former Soviet Union maintained a particularly extensive program of state-imposed censorship. The main organ for official censorship in the Soviet Union was the Chief Agency for Protection of Military and State Secrets, generally known as the Glavlit, its Russian acronym. The Glavlit handled censorship matters arising from domestic writings of just about any kind—even beer and vodka labels. Glavlit censorship personnel were present in every large Soviet publishing house or newspaper; the agency employed some 70,000 censors to review information before it was disseminated by publishing houses, editorial offices, and broadcasting studios. No mass medium escaped Glavlit’s control. All press agencies and radio and television stations had Glavlit representatives on their editorial staffs.

Some thinkers understand censorship to include other attempts to suppress points of view or the exploitation of negative propaganda, media manipulation, spin, disinformation or «free speech zones.» These methods tend to work by disseminating preferred information, by relegating open discourse to marginal forums, and by preventing other ideas from obtaining a receptive audience.

Suppression of access to the means of dissemination of ideas can function as a form of censorship. Such suppression has been alleged to arise from the policies of governmental bodies, such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States of America, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC in Canada, newspapers that refuse to run commentary the publisher disagrees with, lecture halls that refuse to rent themselves out to a particular speaker, and individuals who refuse to finance such a lecture. The omission of selected voices in the content of stories also serves to limit the spread of ideas, and is often called censorship. Such omission can result, for example, from persistent failure or refusal by media organizations to contact criminal defendants (relying solely on official sources for explanations of crime). Censorship has been alleged to occur in such media policies as blurring the boundaries between hard news and news commentary, and in the appointment of allegedly biased commentators, such as a former government attorney, to serve as anchors of programs labeled as hard news but comprising primarily anti-criminal commentary.

In the media

The focusing of news stories to exclude questions that might be of interest to some audience segments, such as the avoidance of reporting cumulative casualty rates among citizens of a nation that is the target or site of a foreign war, is often described as a form of censorship. Favorable representation in news or information services of preferred products or services, such as reporting on leisure travel and comparative values of various machines instead of on leisure activities such as arts, crafts, or gardening has been described by some as a means of censoring ideas about the latter in favor of the former.

Self censorship is censorship imposed on the media in a free market by market or cultural forces rather than a censoring authority. This may occur when it is more profitable for the media to give a biased view. Examples would include near hysterical and scientifically untenable stances against nuclear power, genetic engineering, and recreational drugs being distributed because scare stories sell.

Overcoming censorship

Since the invention of the printing press, distribution of limited production leaflets has often served as an alternative to dominant information sources. Technological advances in communication, such as the Internet, have overcome some censorship. Throughout history, mass protests have also served as a method for resisting unwanted impositions.

Censorship in literature

Censorship through government action is taken to a ridiculous extent and lampooned in the Ray Bradbury novel Fahrenheit 451. The book revolves around the adventure of a «fireman» whose job is to burn books, because the only permitted educational outlet for people in his dystopian society is state controlled television. The novel’s society has strongly anti-intellectual overtones, which Bradbury was attempting to prevent.

Censorship also figures prominently in George Orwell’s novel 1984. That novel’s main character works for the «Ministry of Truth,» which is responsible for disseminating the state’s version of current events and history. Smith’s position requires him to edit history books to keep them in line with the prevailing political mood. Also prominent in the book are the «Thought Police» who arrest and punish citizens who even entertain subversive thoughts. 1984 also highlights the common connection between censorship and propaganda.

Censorship and Society

Censorship presents a danger to an open, democratic world. Most countries claiming to be democratic abide by some standard of publicly releasing materials that are not security risks. This promotes an atmosphere of trust and participation in government, which is a healthier state than the suspicion experienced by those forced to live under censorious, unfree regimes. Freedom of speech has come to be seen as a hallmark of a modern society, with pressures for emerging countries to adopt such standards. Modernizing pressure has forced the opening of many formerly closed societies, such as Russia and China.[7]

Despite its many disreputable uses, censorship also serves a more benign end. Many argue that censorship is necessary for a healthy society and in some cases may be for the protection of the public. One such example is in the broadcasting of explicit material, be it violent or sexual in nature. While it may be argued that broadcasters should be free to broadcast such items, equally, parents should also be free to have their children watch television without the fear that they will see inappropriate material. To this end, societies have developed watchdog agencies to determine decency regulations. In America, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) serves this purpose. Two famous recent cases involving the FCC are the broadcasting of nudity during the Super Bowl and of the unedited Steven Spielberg move Saving Private Ryan. In the first case, the FCC levied great fines on Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) for broadcasting a slip of nudity.[8] In the second case, the FCC warned that fines could be forthcoming if the ABC stations aired the violent film uncut.[9]

Another benign use of censorship is that of information that is secret for national security purposes. Governments maintain a level of secrecy in regards to much pertaining to the national defense so as not to reveal weaknesses to any security risks. Determining the balance between transparent government and safe government is a difficult task. In the United States, there exist a series of «sunshine laws» that require making available to the public government documents once they are no longer vital to national security.

Notes

- ↑ Gina Misiroglu, The Handy American Government Answer Book: How Washington, Politics and Elections Work (Visible Ink Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1578596393).

- ↑ «The Obscenity of Censorship: A History of Indecent People and Lacivious Publications.» The Erotica Bibliophile. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Library of Congress, «Attacks on Intelligentsia: Censorship.»

- ↑ Louis Fiset, «Return to Sender: U.S. Censorship of Enemy Alien Mail in World War II», Prologue Magazine 33(1) (2001). Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Peter Feuilherade, «Iran’s banned press turns to the net» BBC.com, August 9, 2002. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Tait, «Censorship fears rise as Iran blocks access to top websites.» The Guardian, December 3, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Paul Festa, «Software rams great firewall of China.» ZDNet, April 16, 2003. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Apologetic Jackson says ‘costume reveal’ went awry CNN, February 3, 2004. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ ABC affiliate pulling ‘Private Ryan’ CNN, November 11, 2004. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbott, Randy. «A Critical Analysis of the Library-Related Literature Concerning Censorship in Public Libraries and Public School Libraries in the United States During the 1980s» in Project for degree of Education Specialist. University of South Florida, 1987.

- Burress, Lee. Battle of the Books. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1989.

- Butler, Judith. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. 1997. ISBN 0415915872

- Foucault, Michel. Philosophy, Culture: interviews and other writings 1977-1984. New York/London: Routledge, 1988. ISBN 0415900824

- Hansen, Terry. The Missing Times: News media complicity in the UFO cover-up. 2000. ISBN 0738836125

- Hendrikson, Leslie. «Library Censorship: ERIC Digest No. 23» in ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education. Boulder, Colorado, 1985.

- Hoffman, Frank. Intellectual Freedom and Censorship. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 0810821451

- Marek, Kate. Schoolbook Censorship USA. 1987.

- Misiroglu, Gina. The Handy American Government Answer Book: How Washington, Politics and Elections Work. Visible Ink Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1578596393

- O’Reilly, Robert C. and Larry Parker. 1982. «Censorship or Curriculum Modification?» Paper presented at a School Boards Association, 1982.

- Small, Robert C. «Preparing the New English Teacher to Deal with Censorship, or Will I Have to Face it Alone?.» Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English, 1987.

- Terry, John David II. «Censorship: Post Pico» in School Law Update, 1986.

- World Book Encyclopedia, volume 3 (C-Ch), pages 345, 346.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Censorship history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Censorship»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Definitions For Censoring

noun

- Deleting parts of publications or correspondence or theatrical performances

- Counterintelligence achieved by banning or deleting any information of value to the enemy

- A person who examines books, movies, letters, etc., and removes things that are considered to be offensive, immoral, harmful to society, etc.

verb

- To examine books, movies, letters, etc., in order to remove things that are considered to be offensive, immoral, harmful to society, etc.

English International (SOWPODS)

YES

Points in Different Games

Scrabble

Words with Friends

The word Censoring is worth 12 points in Scrabble and 16 points in Words with Friends

Examples of Censoring in a Sentence

- Government censors deleted all references to the protest.

- The station censored her speech before broadcasting it.

- His report was heavily censored.

Synonyms for Censoring

The term censorship refers to the suppression, banning, or deletion of speech, writing, or images that are considered to be indecent, obscene, or otherwise objectionable. Censorship becomes a civil rights issue when a government or other entity with authority, suppresses ideas, or the expression of ideas, information, and self. In the U.S., censorship has been debated for decades, as some seek to protect the public from offensive materials, and others seek to protect the public’s rights to free speech and expression. To explore this concept, consider the following censorship definition.

Definition of Censorship

Noun

- The act of censoring

- The office or authority of a censor

Origin

380 B.C. Greek Philosopher Plato

What is Censorship

The word censorship is from the Latin censere, which is “to give as one’s opinion, to assess.” In Roman times, censors were public officials who took census counts, as well as evaluating public principles and moralities. Societies throughout history have taken on the belief that the government is responsible for shaping the characters of individuals, many engaging in censorship to that end.

In his text The Republic, ancient Greek philosopher Plato makes a systematic case for the need for censorship in the arts. Information in the ancient Chinese society was tightly controlled, a practice that persists in some form today. Finally, many churches, including the Roman Catholic Church, have historically banned literature felt to be contrary to the teachings of the church.

Censorship in America

Many of America’s laws have their origins in English law. In the 1700s, both countries made it their business to censor speech and writings concerning sedition, which are actions promoting the overthrowing of the government, and blasphemy, which is sacrilege or irreverence toward God. The idea that obscenity should be censored didn’t gain serious favor until the mid-1800s. The courts in both countries, throughout history, have worked to suppress speech, writings, and images on these issues.

As time went on, contention arose over just what should be considered “obscene.” Early English law defined obscenity as anything that tended to “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences,” and anything that “might suggest to the minds of the young of either sex, and even to persons of more advanced years, thoughts of a most impure and libidinous character.” This essentially meant anything that might lead one to have “impure” thoughts. This definition carried over into early American law as well.

However, that definition was vague enough to raise more questions than it answered in many circumstances. These included:

- Should adults have a right to read or view “adult materials?”

- When does one legally become an adult?

- Should adult materials be banned simply because a young person might see them?

- How would a court judge whether a particular book, when read by a young person, would cause “impure” thoughts?

Censorship in America took a turn in 1957, when the U.S. Supreme Court declared that adults cannot be reduced to reading “only what is fit for children,” ruling that it must be considered whether the work was originally meant for children or adults. Still, the Court acknowledged that works that are “utterly without redeeming social importance” can be censored or banned. This left another vague standard for the courts to deal with.

Censorship in America is most commonly a question in the entertainment industry, which is widely influential on the young and old alike. Public entertainment in the form of movies, television, music, and electronic gaming are considered to have a substantial effect on public interest. Because of this, it is subject to certain governmental regulations.

Censorship and the First Amendment

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits suppression of an individual’s right to free speech, stating “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press …” This is a principle held dear by those protesting censorship in any form. In the U.S., censorship of obscene materials in entertainment is allowed, in order to protect children from pornography and other offensive things. The problem with government sanctioned censorship is the risk of violating the civil rights of either those producing the materials, or those wishing to view them.

Censorship Example in the Film Industry

The issue of censorship in the film industry has, at times, been quite contentious. In an effort to avoid the censorship issue, while striving to protect children and conform to federal laws, the Motion Picture Association of America (“MPAA”) instituted a self-regulating, voluntary rating system in 1968. In the 1990s, the MPAA updated its rating system, making it easier for parents to determine what is appropriate for their children, based on the children’s ages.

The MPAA rating system has a number of ratings:

| Rating | Long Title | Definition |

| G | General Audiences | All ages admitted. Nothing that would offend parents for viewing by children. |

| PG | Parental Guidance Suggested | Some material may not be suitable for children. Parents urged to give “parental guidance.” May contain some material parents might not like for their young children. |

| PG-13 | Parents Strongly Cautioned | Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13. Parents are urged to be cautious. Some material may be inappropriate for pre-teenagers. |

| R | Restricted | Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian. Contains some adult material. Parents are urged to learn more about the film before taking their young children with them. |

| NC-17 | Adults Only | No One 17 and Under Admitted. Clearly adult. Children are not admitted. |

Rather than censoring movies or their content by exclusion of content, MCAA ratings are assigned by a board of people who view the movies, who consider such factors as violence, sex, drug use, and language when assigning ratings. The board strives to assign a rating that a majority of parents in the U.S. would give, considering their needs to protect their children.

An X rating was part of the MCAA’s original rating system, and signified that no one under the age of 16 would be allowed, regardless of parental accompaniment. The X rating was replaced by the NC-17 rating in 1990.

Internet Censorship

Internet censorship refers to the suppression of information that can be published to, or viewed on, the internet. While many people enjoy unfettered access to the broad spectrum of information racing across the information highway, others are denied access, or allowed access only to government approved information. Rationales for internet censorship range from a desire to protect children from content that is offensive or inappropriate, to a government’s objective to control its people’s access to world news, opinions, and other information.

In the United States, the First Amendment affords the people some protection of their right to freely access the internet, and of the things they post to the web. Because of this, there is very little government-mandated “filtering” of information that originates in the U.S. The issue of censorship of certain content, especially content that may further terrorism, is constantly debated at the federal government level.

As an example of censorship, the following countries are known for censoring their people’s internet content:

- North Korea – only about 4% of the people have access to the internet, and the only content allowed is government-controlled.

- Burma – the government filters the people’s emails, and blocks access to any sites or information exposing human rights violations in the country.

- Saudi Arabia – the government blocks nearly half a million websites, especially those that discuss religious, social, or political topics that conflict with the beliefs of the monarchy.

- Iran – the government censors information coming into, and going out of, the nation. Bloggers are required to register with the Ministry of Art and Culture. Any who express opinions contrary to those of the governmental leaders are harassed and put in jail.

- China – the government enforces the harshest program of internet censorship in the world. While users have access to some form of internet, their searches are filtered, sites are blocked, and searches on such issues as Taiwan independence, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or other controversial issues to sites that offer information that is more flattering to the Communist Party.

Landmark Ruling on Censorship of Magazine Sales

In the mid-1960s, Sam Ginsberg, who owned Sam’s Stationery and Luncheonette on Long Island, was charged with selling “girlie” magazines to a 16-year old boy, which was in violation of New York state law. Ginsberg was tried in the Nassau County District Court, without a jury, and found guilty. The judge found that the magazines contained pictures which, by failing to cover the female buttocks and breasts with an opaque covering, were harmful to minors. He stated that the photos appealed to the “prurient, shameful or morbid interest of minors,” and that the images were patently offensive to standards held by the adult community regarding what was suitable for minors.

Ginsberg was denied the right to appeal his convictions to the New York Court of Appeals, at which time he took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court, on the basis that the state of New York had no authority to define two separate classes of people (minors and adults), with respect to what is harmful. In addition, Ginsberg argued that it was easy to mistake a young person’s age, and the law makes no requirement for how much effort a shop owner must put into determining age before selling magazines intended for adult viewing. The Court did not agree, holding that Ginsberg might be acquitted on the grounds of an “honest mistake,” only if he had made “a reasonable bonafide attempt to ascertain the true age of such a minor.” The conviction was upheld.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Appeal – A legal proceeding in which a legal decision is taken to a higher court for review.

- Deprave – Morally bad or debased, corrupt.

- Monarchy – A system of government controlled by one person, usually a king or queen.

Here are two words that are easy to confuse: censor and censure. Let’s try to get them straight.

They are not homophones exactly because they are subtly different in pronunciation. The key is the s in the middle. In censure, it’s pronounced sh like in the word sure. It’s pronounced like a standard s in censor.

Censor

Both words have a noun use and a verb use. A censor (noun) is an official whose job is to examine material for publication and eliminate objectionable matter.

To censor (verb) something is to remove or suppress what is offensive or objectionable.

Censorship is a noun form of the word that refers to the practice of censoring.

In general, censorship carries a negative connotation in the U.S.. Because we value the constitutionally protected concept of free speech, most of Americans object to anything that smells of censorship, especially by the government. Yet, most Americans favor at least some forms of censorship, which is why federal law prohibits the publication of pornography, profanity, and other morally questionable content through easily accessible public media like television and radio.

Click Here to Check Out WriteAtHome or Enroll Now!

Censure

Censure (noun) means “an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism.” Similarly, the verb censure means to rebuke or condemn.

Political bodies sometimes resort to censure to formally reprimand misbehaving members. Last year, for example, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to censure Attorney General Eric Holder for refusing to release documents related to the “Fast and Furious” scandal.

Churches and religious bodies might censure an individual as well, an action that might lead to excommunication.

Typically, censure is a formal, public action. An individual criticizing another would not, for example, be considered censure. Nor would a private rebuke. Censuring may or may not carry consequences. Ecclesiastical censure may result in excommunication (though not necessarily), whereas political censure is often used in place of any kind of punitive measures.

Why the Confusion?

Writers and speakers occasionally confuse the two words primarily because of their aural similarity. Both words come from the same Latin word censēre, meaning “to give as one’s opinion, assess.” Both censoring and censuring involve the rendering of a negative opinion — the former leading to removal or suppression and the latter to formal and/or public denouncement.

But one typically only censors publishable material — words and images, while censure is reserved for people. I suppose it’s possible to censure a statement, leading to its being censored, but that would be an atypical use of censure.

*****

As always, I’d love your feedback and comments. Please leave them below.

I doubt it’s a question that academia can answer because ultimately it’s not really a «problem» that can be «solved», it’s a conflict of interest that can only be resolved if the respective parties agree to a resolution.

Like ultimately it’s about whether you respect someone else’s request not to use a word regardless of circumstances or whether you don’t. That’s a decision that you make. And the reasons why that person doesn’t want you to use that word are subjective, so you’d need to negotiate that with that respective person on a case by case basis. Or if it’s a notion expressed by a group with that group.

Sure you can attempt to generalize that the usage of a term is not offensive, but it would be incredibly tone deaf and condescending to tell other people what THEY should and shouldn’t find offensive, like that question is theirs to answer, not yours.

You could formulate edge cases for that, like if language is being censored to the point where you lose expressive power you might side with ignoring the request, if there are alternative words that express the same concept or even express it better without additional baggage you might side with respecting the request or if the word is a literal trigger event for an emotional reaction you might in that situation opt to respect the request. Like if the word «sugar powder» articulated near microphone triggers nuclear Armageddon you might not want to use it despite there’s absolutely nothing wrong with using these 2 words in almost any other context.

And whether it is or isn’t a trigger is again something that can only be answered by those for whom it is a trigger. You can’t assume that, you might not even be able to rationalize it as they might not be able to rationalize that either you could only chose to respect or not respect that request.

To be frank about it, I do not understand the notion of people that claim the word itself is problematic. Like you could imagine a language where the physical articulation of a pattern of speech physically hurts you (like a high pitches screech or whatnot) or where the word itself expresses a concept like idk if the name of your group idk «philosophers» would literally be comprised of the words for «bullshit thinkers» or something like that, so where the insult is literally part of the word.

The n-word is neither. The n-word, on a literal level, just means «black» and it’s not by itself hurtful to say. The insulting hurtful part stems pretty much entirely from it’s context and usage. In that it only makes sense in the context of white supremacy in which being black itself is an insult and used with hatred and contempt and the intent to impress a notion of inferiority to the other person.

What is special about it is most likely it’s ubiquitous and continued usage throughout a large period of time and space. So that it projects it’s own context in the sense that you don’t use it unless you’re a white supremacist and using it is itself a statement of hatred and contempt up to a direct threat to someone’s well being.

Now while in direct communication any word for that matter could be used as a drop-in replacement for the n-word, as it’s not about the word but about the context, seriously calling someone a «hamster» while giving off vibes of intimidation would trigger a similar result. That would be a localized phenomena and other people wouldn’t be in on the meaning so it would lose a lot of it’s power compared to being faced with what might seem to be a giant monolith.

So in other words it needs time, shared memory and continued usage in the public discourse for such a word to enter common knowledge so banning such a word completely sets racists back to square one, just that ideally now they lack the control over the public narrative and the systemic power that they used to have. Meaning it could actually make a difference. Because now people who still use the term stick out like a sore thumb, while if a term is normalized you’d create an image where racists appear much more numerous then they might actually be and where bystanders might assume «just a miscommunication» rather than a deliberate act of hostility when the word is used thereby enforcing that image and enabling abuse.

However that can also make the use/mention distinction difficult because that also sticks out, intended or not. And despite mentioning not being usage in terms of applying it to hurt people, it’s still normalizing the usage of the term. And getting people accustomed to people saying racist shit to harden them against being shocked by that, isn’t necessarily a great idea either as you might also harden yourself against feeling empathy for people on the receiving end as you no longer feel it to be shocking and problematic.

On the other end, if these cases in the article are true it seems pretty ridiculous that people who do not act racist, explicitly position themselves against it and whatnot, should lose their jobs over quotes and mentions. If those were accurate descriptions and not omitted crucial details that seems excessive and counter productive. Especially while simultaneously racism itself and the racist language surrounding these terms is apparently still treated as free speech and not seen as problematic or producing similar levels of outrage as the more catchy use of bad terminology. So that it appears to be treating symptoms rather than root causes.

But apparently this fixation and censorship of words seems to be a cultural thing in the U.S. where there seems to be a whole alphabet of words your not supposed to say and where the words themselves are treated as powerful. So it’s probably only fitting to attempt to add racial slurs on that list as it’s already culturally accepted to not use these words.

The plaster cast of David at the Victoria and Albert Museum has a detachable plaster fig leaf which is displayed nearby. Legend claims that the fig leaf was created in response to Queen Victoria’s shock upon first viewing the statue’s nudity and was hung on the figure prior to royal visits, using two strategically placed hooks.[1]

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or «inconvenient».[2][3][4] Censorship can be conducted by governments,[5] private institutions and other controlling bodies.

Governments[5] and private organizations may engage in censorship. Other groups or institutions may propose and petition for censorship.[6] When an individual such as an author or other creator engages in censorship of their own works or speech, it is referred to as self-censorship. General censorship occurs in a variety of different media, including speech, books, music, films, and other arts, the press, radio, television, and the Internet for a variety of claimed reasons including national security, to control obscenity, pornography, and hate speech, to protect children or other vulnerable groups, to promote or restrict political or religious views, and to prevent slander and libel.

Direct censorship may or may not be legal, depending on the type, location, and content. Many countries provide strong protections against censorship by law, but none of these protections are absolute and frequently a claim of necessity to balance conflicting rights is made, in order to determine what could and could not be censored. There are no laws against self-censorship.

History[edit]

In 399 BC, Greek philosopher, Socrates, while defying attempts by the Athenian state to censor his philosophical teachings, was accused of collateral charges related to the corruption of Athenian youth and sentenced to death by drinking a poison, hemlock.

The details of Socrates’s conviction are recorded by Plato as follows. In 399 BC, Socrates went on trial[8] and was subsequently found guilty of both corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens and of impiety (asebeia,[9] «not believing in the gods of the state»),[10] and as a punishment sentenced to death, caused by the drinking of a mixture containing hemlock.[11][12][13]

Socrates’ student, Plato, is said to have advocated censorship in his essay on The Republic, which opposed the existence of democracy. In contrast to Plato, Greek playwright Euripides (480–406 BC) defended the true liberty of freeborn men, including the right to speak freely. In 1766, Sweden became the first country to abolish censorship by law.[14]

Rationale and criticism[edit]

Censorship has been criticized throughout history for being unfair and hindering progress. In a 1997 essay on Internet censorship, social commentator Michael Landier claims that censorship is counterproductive as it prevents the censored topic from being discussed. Landier expands his argument by claiming that those who impose censorship must consider what they censor to be true, as individuals believing themselves to be correct would welcome the opportunity to disprove those with opposing views.[15]

Censorship is often used to impose moral values on society, as in the censorship of material considered obscene. English novelist E. M. Forster was a staunch opponent of censoring material on the grounds that it was obscene or immoral, raising the issue of moral subjectivity and the constant changing of moral values. When the 1928 novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover was put on trial in 1960, Forster wrote:[16]

Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a literary work of importance…I do not think that it could be held obscene, but am in a difficulty here, for the reason that I have never been able to follow the legal definition of obscenity. The law tells me that obscenity may deprave and corrupt, but as far as I know, it offers no definition of depravity or corruption.

Proponents have sought to justify it using different rationales for various types of information censored:

- Moral censorship is the removal of materials that are obscene or otherwise considered morally questionable. Pornography, for example, is often censored under this rationale, especially child pornography, which is illegal and censored in most jurisdictions in the world.[17][18]

- Military censorship is the process of keeping military intelligence and tactics confidential and away from the enemy. This is used to counter espionage.

- Political censorship occurs when governments hold back information from their citizens. This is often done to exert control over the populace and prevent free expression that might foment rebellion.

- Religious censorship is the means by which any material considered objectionable by a certain religion is removed. This often involves a dominant religion forcing limitations on less prevalent ones. Alternatively, one religion may shun the works of another when they believe the content is not appropriate for their religion.

- Corporate censorship is the process by which editors in corporate media outlets intervene to disrupt the publishing of information that portrays their business or business partners in a negative light,[19][20] or intervene to prevent alternate offers from reaching public exposure.[21]

Types[edit]

Political[edit]

State secrets and prevention of attention[edit]

The daily newspaper of Wrocław, Polish People’s Republic, March 20–21, 1981, with censor intervention on first and last pages – under the headlines «Co zdarzyło się w Bydgoszczy?» (What happened in Bydgoszcz?) and «Pogotowie strajkowe w całym kraju» (Country-wide strike alert). The censor had removed a section regarding the strike alert; hence the workers in the printing house blanked out an official propaganda section. The right-hand page also includes a hand-written confirmation of that decision by the local Solidarity trade union.

In wartime, explicit censorship is carried out with the intent of preventing the release of information that might be useful to an enemy. Typically it involves keeping times or locations secret, or delaying the release of information (e.g., an operational objective) until it is of no possible use to enemy forces. The moral issues here are often seen as somewhat different, as the proponents of this form of censorship argue that the release of tactical information usually presents a greater risk of casualties among one’s own forces and could possibly lead to loss of the overall conflict.

During World War I letters written by British soldiers would have to go through censorship. This consisted of officers going through letters with a black marker and crossing out anything which might compromise operational secrecy before the letter was sent.[22] The World War II catchphrase «Loose lips sink ships» was used as a common justification to exercise official wartime censorship and encourage individual restraint when sharing potentially sensitive information.[23]

An example of «sanitization» policies comes from the USSR under Joseph Stalin, where publicly used photographs were often altered to remove people whom Stalin had condemned to execution. Though past photographs may have been remembered or kept, this deliberate and systematic alteration to all of history in the public mind is seen as one of the central themes of Stalinism and totalitarianism.

Censorship is occasionally carried out to aid authorities or to protect an individual, as with some kidnappings when attention and media coverage of the victim can sometimes be seen as unhelpful.[24]

Religion[edit]

Portrayal of the burning of William Pynchon’s 1650 critique on Puritanical Calvinism in Boston by the Puritan-controlled Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Censorship by religion is a form of censorship where freedom of expression is controlled or limited using religious authority or on the basis of the teachings of the religion.[25] This form of censorship has a long history and is practiced in many societies and by many religions. Examples include the Galileo affair, Edict of Compiègne, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of prohibited books) and the condemnation of Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses by Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Images of the Islamic figure Muhammad are also regularly censored. In some secular countries, this is sometimes done to prevent hurting religious sentiments.[26]

Educational sources[edit]

Historic Russian censorship. Book Notes of my life by N.I. Grech, published in St. Petersburg 1886 by A.S. Suvorin. The censored text was replaced by dots.

The content of school textbooks is often an issue of debate, since their target audiences are young people. The term whitewashing is commonly used to refer to revisionism aimed at glossing over difficult or questionable historical events, or a biased presentation thereof. The reporting of military atrocities in history is extremely controversial, as in the case of The Holocaust (or Holocaust denial), Bombing of Dresden, the Nanking Massacre as found with Japanese history textbook controversies, the Armenian genocide, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and the Winter Soldier Investigation of the Vietnam War.

In the context of secondary school education, the way facts and history are presented greatly influences the interpretation of contemporary thought, opinion and socialization. One argument for censoring the type of information disseminated is based on the inappropriate quality of such material for the younger public. The use of the «inappropriate» distinction is in itself controversial, as it changed heavily. A Ballantine Books version of the book Fahrenheit 451 which is the version used by most school classes[27] contained approximately 75 separate edits, omissions, and changes from the original Bradbury manuscript.

In February 2006, a National Geographic cover was censored by the Nashravaran Journalistic Institute. The offending cover was about the subject of love and a picture of an embracing couple was hidden beneath a white sticker.[28]

Economic induced censorship[edit]

Economic induced censorship is a type of censorship enacted by economic markets to favor, and disregard, types of information. Economic induced censorship, is also caused, by market forces which privatize and establish commodification of certain information that is not accessible by the general public, primarily because of the cost associated with commodified information such as academic journals, industry reports and pay to use repositories.[29]

The concept was illustrated as a censorship pyramid[30] that was conceptualized by primarily Julian Assange, along with Andy Müller-Maguhn, Jacob Appelbaum and Jérémie Zimmermann, in the Cypherpunks (book).

Self-censorship[edit]

Self-censorship is the act of censoring or classifying one’s own discourse. This is done out of fear of, or deference to, the sensibilities or preferences (actual or perceived) of others and without overt pressure from any specific party or institution of authority. Self-censorship is often practiced by film producers, film directors, publishers, news anchors, journalists, musicians, and other kinds of authors including individuals who use social media.[32]

According to a Pew Research Center and the Columbia Journalism Review survey, «About one-quarter of the local and national journalists say they have purposely avoided newsworthy stories, while nearly as many acknowledge they have softened the tone of stories to benefit the interests of their news organizations. Fully four-in-ten (41%) admit they have engaged in either or both of these practices.»[33]

Threats to media freedom have shown a significant increase in Europe in recent years, according to a study published in April 2017 by the Council of Europe.

This results in a fear of physical or psychological violence, and the ultimate result is self-censorship by journalists.[34]

Copy, picture, and writer approval[edit]

Copy approval is the right to read and amend an article, usually an interview, before publication. Many publications refuse to give copy approval but it is increasingly becoming common practice when dealing with publicity anxious celebrities.[35] Picture approval is the right given to an individual to choose which photos will be published and which will not. Robert Redford is well known for insisting upon picture approval.[36] Writer approval is when writers are chosen based on whether they will write flattering articles or not. Hollywood publicist Pat Kingsley is known for banning certain writers who wrote undesirably about one of her clients from interviewing any of her other clients.[citation needed]

Reverse censorship[edit]

Flooding the public, often through online social networks, with false or misleading information is sometimes called «reverse censorship». American legal scholar Tim Wu has explained that this type of information control, sometimes by state actors, can «distort or drown out disfavored speech through the creation and dissemination of fake news, the payment of fake commentators, and the deployment of propaganda robots.»[37]

By media[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: Television and News Media censorship. You can help by adding to it. (May 2020) |

Books[edit]

Book censorship can be enacted at the national or sub-national level, and can carry legal penalties for their infraction. Books may also be challenged at a local, community level. As a result, books can be removed from schools or libraries, although these bans do not typically extend outside of that area.

Films[edit]

Aside from the usual justifications of pornography and obscenity, some films are censored due to changing racial attitudes or political correctness in order to avoid ethnic stereotyping and/or ethnic offense despite its historical or artistic value. One example is the still withdrawn «Censored Eleven» series of animated cartoons, which may have been innocent then, but are «incorrect» now.[citation needed]

Film censorship is carried out by various countries. Film censorship is achieved by censoring the producer or restricting a state citizen. For example, in China the film industry censors LGBT-related films. Filmmakers must resort to finding funds from international investors such as the «Ford Foundations» and or produce through an independent film company.[38]

Music[edit]

Music censorship has been implemented by states, religions, educational systems, families, retailers and lobbying groups – and in most cases they violate international conventions of human rights.[39]

Maps[edit]

Censorship of maps is often employed for military purposes. For example, the technique was used in former East Germany, especially for the areas near the border to West Germany in order to make attempts of defection more difficult. Censorship of maps is also applied by Google Maps, where certain areas are grayed out or blacked or areas are purposely left outdated with old imagery.[40]

Art[edit]

Art is loved and feared because of its evocative power. Destroying or oppressing art can potentially justify its meaning even more.[41]

British photographer and visual artist Graham Ovenden’s photos and paintings were ordered to be destroyed by a London’s magistrate court in 2015 for being «indecent»[42] and their copies had been removed from the online Tate gallery.[43]

Artworks using these four colors were banned by Israeli law in the 1980s. This ban ended in 1993.

A 1980 Israeli law forbade banned artwork composed of the four colours of the Palestinian flag,[44] and Palestinians were arrested for displaying such artwork or even for carrying sliced melons with the same pattern.[45][46][47]

Cuban artist Tania Bruguera

Moath al-Alwi is a Guantanamo Bay prisoner who creates model ships as an expression of art. Alwi does so with the few tools he has at his disposal such as dental floss and shampoo bottles, and he is also allowed to use a small pair of scissors with rounded edges.[48] A few of Alwi’s pieces are on display at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. There are also other artworks on display at the College that were created by other inmates. The artwork that is being displayed might be the only way for some of the inmates to communicate with the outside. Recently things have changed though. The military has come up with a new policy that will not allow the artwork at Guantanamo Bay Military Prison to leave the prison. The artwork created by Alwi and other prisoners is now government property and can be destroyed or disposed of in whatever way the government choose, making it no longer the artist’s property.[49]