This article is about the ancient and medieval peoples of Europe. For Celts of the present day, see Celts (modern). For other uses, see Celt (disambiguation).

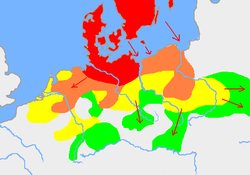

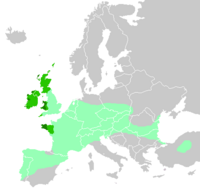

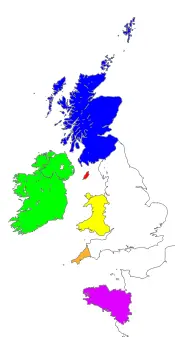

Distribution of Celtic peoples over time, in the traditional view:

-

Core Hallstatt territory, by the sixth century BC

-

Greatest Celtic expansion by 275 BC

-

Lusitanian area of Iberia where Celtic presence is uncertain

-

Areas in which Celtic languages were spoken throughout the Middle Ages

-

Areas where Celtic languages remain widely spoken today

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are[1] a collection of Indo-European peoples[2] in Europe and Anatolia, identified by their use of Celtic languages and other cultural similarities.[3][4][5][6] Historical Celtic groups included the Britons, Boii, Celtiberians, Gaels, Gauls, Gallaeci,[7][8] Galatians, Lepontii and their offshoots. The relation between ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world is unclear and debated;[9] for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts.[6][9][10][11] In current scholarship, ‘Celt’ primarily refers to ‘speakers of Celtic languages’ rather than to a single ethnic group.[12]

The history of pre-Celtic Europe and Celtic origins is debated. The traditional «Celtic from the East» theory, says the Proto-Celtic language arose in the late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of central Europe, named after grave sites in southern Germany,[13][14] which flourished from around 1200 BC.[15] This theory links the Celts with the Iron Age Hallstatt culture which followed it (c. 1200–500 BC), named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria,[15][16] and with the following La Tène culture (c. 450 BC onward), named after the La Tène site in Switzerland. It proposes that Celtic culture spread from these areas by diffusion or migration, westward to Gaul, the British Isles and Iberia, and southward to Cisalpine Gaul.[17] A newer theory, «Celtic from the West», suggests Proto-Celtic arose earlier, was a lingua franca in the Atlantic Bronze Age coastal zone, and spread eastward.[18] Another newer theory, «Celtic from the Centre», suggests Proto-Celtic arose between these two zones, in Bronze Age Gaul, then spread in various directions.[12] After the Celtic settlement of Southeast Europe in the 3rd century BC, Celtic culture reached as far east as central Anatolia, Turkey.

The earliest undisputed examples of Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions from the 6th century BC.[19] Continental Celtic languages are attested almost exclusively through inscriptions and place-names. Insular Celtic languages are attested from the 4th century AD in Ogham inscriptions, though they were clearly being spoken much earlier. Celtic literary tradition begins with Old Irish texts around the 8th century AD. Elements of Celtic mythology are recorded in early Irish and early Welsh literature. Most written evidence of the early Celts comes from Greco-Roman writers, who often grouped the Celts as barbarian tribes. They followed an ancient Celtic religion overseen by druids.

The Celts were often in conflict with the Romans, such as in the Roman–Gallic wars, the Celtiberian Wars, the conquest of Gaul and conquest of Britain. By the 1st century AD, most Celtic territories had become part of the Roman Empire. By c. 500, due to Romanisation and the migration of Germanic tribes, Celtic culture had mostly become restricted to Ireland, western and northern Britain, and Brittany. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the Celtic-speaking communities in these Atlantic regions emerged as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. They had a common linguistic, religious and artistic heritage that distinguished them from surrounding cultures.[20]

Insular Celtic culture diversified into that of the Gaels (Irish, Scots and Manx) and the Celtic Britons (Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons) of the medieval and modern periods.[3][21][22] A modern Celtic identity was constructed as part of the Romanticist Celtic Revival in Britain, Ireland, and other European territories such as Galicia.[23] Today, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton are still spoken in parts of their former territories, while Cornish and Manx are undergoing a revival.

Names and terminology

Ancient

The first recorded use of the name ‘Celts’ – as Κελτοί (Keltoi) in Ancient Greek – was by Greek geographer Hecataeus of Miletus in 517 BC,[24] when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille), southern Gaul.[25] In the fifth century BC, Herodotus referred to Keltoi living around the source of the Danube and in the far west of Europe.[26] The etymology of Keltoi is unclear. Possible roots include Indo-European *kʲel ‘to hide’ (seen also in Old Irish ceilid, and Modern Welsh celu), *kʲel ‘to heat’ or *kel ‘to impel’.[27] It may come from the Celtic language. Linguist Kim McCone supports this view and notes that Celt- is found in the names of several ancient Gauls such as Celtillus, father of Vercingetorix. He suggests it meant the people or descendants of «the hidden one», noting the Gauls claimed descent from an underworld god (according to Commentarii de Bello Gallico), and linking it with the Germanic Hel.[28] Others view it as a name coined by Greeks; among them linguist Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, who suggests it meant «the tall ones».[29]

In the first century BC, Roman leader Julius Caesar reported that the Gauls called themselves ‘Celts’, Latin: Celtae, in their own tongue.[30] Thus whether it was given to them by others or not, it was used by the Celts themselves. Greek geographer Strabo, writing about Gaul towards the end of the first century BC, refers to the «race which is now called both Gallic and Galatic«, though he also uses Celtica as another name for Gaul. He reports Celtic peoples in Iberia too, calling them Celtiberi and Celtici.[31] Pliny the Elder noted the use of Celtici in Lusitania as a tribal surname,[32] which epigraphic findings have confirmed.[33][34]

A Latin name for the Gauls, Galli (pl.), may come from a Celtic ethnic name, perhaps borrowed into Latin during the Celtic expansion into Italy from the early fifth century BC. Its root may be Proto-Celtic *galno, meaning «power, strength» (whence Old Irish gal «boldness, ferocity», Welsh gallu «to be able, power»). The Greek name Γαλάται (Galatai, Latinized Galatae) most likely has the same origin, referring to the Gauls who invaded southeast Europe and settled in Galatia.[35] The suffix -atai might be a Greek inflection.[36] Linguist Kim McCone suggests it comes from Proto-Celtic *galatis («ferocious, furious»), and was not originally an ethnic name but a name for young warrior bands. He says «If the Gauls’ initial impact on the Mediterranean world was primarily a military one typically involving fierce young *galatīs, it would have been natural for the Greeks to apply this name for the type of Keltoi that they usually encountered».[28]

Because Classical writers did not call the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland Κελτοί (Keltoi) or Celtae,[6][9][10] some scholars prefer not to use the term for the Iron Age inhabitants of those islands.[6][9][10][11] However, they spoke Celtic languages, shared other cultural traits, and Roman historian Tacitus says the Britons resembled the Gauls in customs and religion.[12]

Modern

Celt is a modern English word, first attested in 1707 in the writing of Edward Lhuyd, whose work, along with that of other late 17th-century scholars, brought academic attention to the languages and history of the early Celtic inhabitants of Great Britain.[37] The English words Gaul, Gauls (pl.) and Gaulish (first recorded in the 16–17th centuries) come from French Gaule and Gaulois, a borrowing from Frankish *Walholant, «Roman land» (see Gaul: Name), the root of which is Proto-Germanic *walha-, «foreigner, Roman, Celt», whence the English word ‘Welsh’ (Old English wælisċ). Proto-Germanic *walha comes from the name of the Volcae,[38] a Celtic tribe who lived first in southern Germany and central Europe, then migrated to Gaul.[39] This means that English Gaul, despite its superficial similarity, is not actually derived from Latin Gallia (which should have produced *Jaille in French), though it does refer to the same ancient region.[citation needed]

Celtic refers to a language family and, more generally, means «of the Celts» or «in the style of the Celts». Several archaeological cultures are considered Celtic, based on unique sets of artefacts. The link between language and artefact is aided by the presence of inscriptions.[40] The modern idea of a Celtic cultural identity or «Celticity» focuses on similarities among languages, works of art, and classical texts,[41] and sometimes also among material artefacts, social organisation, homeland and mythology.[42] Earlier theories held that these similarities suggest a common racial origin for the various Celtic peoples, but more recent theories hold that they reflect a common cultural and linguistic heritage more than a genetic one. Celtic cultures seem to have been diverse, with the use of a Celtic language being the main thing they had in common.[6]

Today, the term ‘Celtic’ generally refers to the languages and cultures of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany; also called the Celtic nations. These are the regions where Celtic languages are still spoken to some extent. The four are Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton; plus two recent revivals, Cornish (a Brittonic language) and Manx (a Goidelic language). There are also attempts to reconstruct Cumbric, a Brittonic language of northern Britain. Celtic regions of mainland Europe are those whose residents claim a Celtic heritage, but where no Celtic language survives; these include western Iberia, i.e. Portugal and north-central Spain (Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León, Extremadura).[43]

Continental Celts are the Celtic-speaking people of mainland Europe and Insular Celts are the Celtic-speaking people of the British and Irish islands, and their descendants. The Celts of Brittany derive their language from migrating Insular Celts from Britain and so are grouped accordingly.[44]

Origins

The Celtic languages are a branch of the Indo-European languages. By the time Celts are first mentioned in written records around 400 BC, they were already split into several language groups, and spread over much of western mainland Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, Ireland and Britain. The languages developed into Celtiberian, Goidelic and Brittonic branches, among others.[45][46]

Urnfield-Hallstatt theory

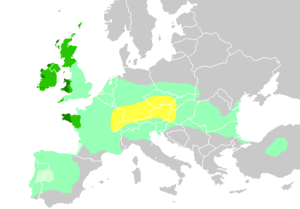

Overview of the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures.

The core Hallstatt territory (HaC, 800 BC) is shown in solid yellow.

The eventual area of Hallstatt influence (by 500 BC, HaD) in light yellow.

The core territory of the La Tène culture (450 BC) in solid green.

The eventual area of La Tène influence (by 250 BC) in light green.

The territories of some major Celtic tribes of the late La Tène period are labelled.

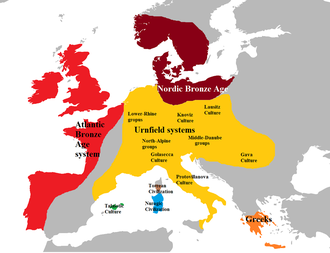

The mainstream view during most of the twentieth century is that the Celts and the proto-Celtic language arose out of the Urnfield culture of central Europe around 1000 BC, spreading westward and southward over the following few hundred years.[15][47][48][49] The Urnfield culture was preeminent in central Europe during the late Bronze Age, circa 1200 BC to 700 BC. The spread of iron-working led to the Hallstatt culture (c. 800 to 500 BC) developing out of the Urnfield culture in a wide region north of the Alps. The Hallstatt culture developed into the La Tène culture from about 450 BC, which came to be identified with Celtic art.[citation needed]

In 1846, Johann Georg Ramsauer unearthed an ancient grave field with distinctive grave goods at Hallstatt, Austria. Because the burials «dated to roughly the time when Celts are mentioned near the Danube by Herodotus, Ramsauer concluded that the graves were Celtic».[50] Similar sites and artifacts were found over a wide area, which were named the ‘Hallstatt culture’. In 1857, the archaeological site of La Tène was discovered in Switzerland.[50] The huge collection of artifacts had a distinctive style. Artifacts of this ‘La Tène style’ were found elsewhere in Europe, «particularly in places where people called Celts were known to have lived and early Celtic languages are attested. As a result, these items quickly became associated with the Celts, so much so that by the 1870s scholars began to regard finds of the La Tène as ‘the archaeological expression of the Celts'».[50] This cultural network was overrun by the Roman Empire, though traces of La Tène style were still seen in Gallo-Roman artifacts. In Britain and Ireland, the La Tène style survived precariously to re-emerge in Insular art.[citation needed]

The Urnfield-Hallstatt theory began to be challenged in the latter 20th century, when it was accepted that the oldest known Celtic-language inscriptions were those of Lepontic from the 6th century BC and Celtiberian from the 2nd century BC. These were found in northern Italy and Iberia, neither of which were part of the ‘Hallstatt’ nor ‘La Tène’ cultures at the time.[12] The Urnfield-Hallstatt theory was partly based on ancient Greco-Roman writings, such as the Histories of Herodotus, which placed the Celts at the source of the Danube. However, Stephen Oppenheimer shows that Herodotus seemed to believe the Danube rose near the Pyrenees, which would place the Ancient Celts in a region which is more in agreement with later classical writers and historians (i.e. in Gaul and Iberia).[51] The theory was also partly based on the abundance of inscriptions bearing Celtic personal names in the Eastern Hallstatt region (Noricum). However, Patrick Sims-Williams notes that these date to the later Roman era, and says they suggest «relatively late settlement by a Celtic-speaking elite».[12]

‘Celtic from the West’ theory

A map of Europe in the Bronze Age, showing the Atlantic network in red

In the late 20th century, the Urnfield-Hallstatt theory began to fall out of favour with some scholars, which was influenced by new archaeological finds. ‘Celtic’ began to refer primarily to ‘speakers of Celtic languages’ rather than to a single culture or ethnic group.[12] A new theory suggested that Celtic languages arose earlier, along the Atlantic coast (including Britain, Ireland, Armorica and Iberia), long before evidence of ‘Celtic’ culture is found in archaeology. Myles Dillon and Nora Kershaw Chadwick argued that «Celtic settlement of the British Isles» might date to the Bell Beaker culture of the Copper and Bronze Age (from c. 2750 BC).[52][53] Martín Almagro Gorbea (2001) also proposed that Celtic arose in the 3rd millennium BC, suggesting that the spread of the Bell Beaker culture explained the wide dispersion of the Celts throughout western Europe, as well as the variability of the Celtic peoples.[54] Using a multidisciplinary approach, Alberto J. Lorrio and Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero reviewed and built on Almagro Gorbea’s work to present a model for the origin of Celtic archaeological groups in Iberia and proposing a rethinking of the meaning of «Celtic».[55]

John T. Koch[56] and Barry Cunliffe[57] have developed this ‘Celtic from the West’ theory. It proposes that the proto-Celtic language arose along the Atlantic coast and was the lingua franca of the Atlantic Bronze Age cultural network, later spreading inland and eastward.[12] More recently, Cunliffe proposes that proto-Celtic had arisen in the Atlantic zone even earlier, by 3000 BC, and spread eastwards with the Bell Beaker culture over the following millennium. His theory is partly based on glottochronology, the spread of ancient Celtic-looking placenames, and thesis that the Tartessian language was Celtic.[12] However, the proposal that Tartessian was Celtic is widely rejected by linguists, many of whom regard it as unclassified.[58][59]

‘Celtic from the Centre’ theory

Celticist Patrick Sims-Williams (2020) notes that in current scholarship, ‘Celt’ is primarily a linguistic label. In his ‘Celtic from the Centre’ theory, he argues that the proto-Celtic language did not originate in central Europe nor the Atlantic, but in-between these two regions. He suggests that it «emerged as a distinct Indo-European dialect around the second millennium BC, probably somewhere in Gaul [centered in modern France] […] whence it spread in various directions and at various speeds in the first millennium BC». Sims-Williams says this avoids the problematic idea «that Celtic was spoken over a vast area for a very long time yet somehow avoided major dialectal splits», and «it keeps Celtic fairly close to Italy, which suits the view that Italic and Celtic were in some way linked».[12]

Linguistic evidence

The Proto-Celtic language is usually dated to the Late Bronze Age.[15] The earliest records of a Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions of Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy), the oldest of which pre-date the La Tène period. Other early inscriptions, appearing from the early La Tène period in the area of Massilia, are in Gaulish, which was written in the Greek alphabet until the Roman conquest. Celtiberian inscriptions, using their own Iberian script, appear later, after about 200 BC. Evidence of Insular Celtic is available only from about 400 AD, in the form of Primitive Irish Ogham inscriptions.[citation needed]

Besides epigraphic evidence, an important source of information on early Celtic is toponymy (place names).[60]

Genetic evidence

Arnaiz-Villena et al. (2017) demonstrated that Celtic-related populations of the European Atlantic (Orkney Islands, Scottish, Irish, British, Bretons, Basques, Galicians) shared a common HLA system.[clarification needed][61]

Other genetic research does not support the notion of a significant genetic link between these populations, beyond the fact that they are all West Europeans. Early European Farmers did settle Britain (and all of Northern Europe) in the Neolithic; however, recent genetics research has found that, between 2400 and 2000 BC, over 90% of British DNA was overturned by European Steppe Herders in a migration that brought large amounts of Steppe DNA (including the R1b haplogroup) to western Europe.[62] Modern autosomal genetic clustering is testament to this fact, as both modern and Iron Age British and Irish samples cluster genetically very closely with other North Europeans, and less so with Galicians, Basques or those from the south of France.[63][64]

Archaeological evidence

Reconstruction of a late La Tène period settlement in Altburg near Bundenbach, Germany

(first century BC)

Reconstruction of a late La Tène period settlement in Havranok, Slovakia

(second–first century BC)

The concept that the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures could be seen not just as chronological periods but as «Culture Groups», entities composed of people of the same ethnicity and language, had started to grow by the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century the belief that these «Culture Groups» could be thought of in racial or ethnic terms was held by Gordon Childe, whose theory was influenced by the writings of Gustaf Kossinna.[65] As the 20th century progressed, the ethnic interpretation of La Tène culture became more strongly rooted, and any findings of La Tène culture and flat inhumation cemeteries were linked to the Celts and the Celtic language.[66]

In various[clarification needed] academic disciplines the Celts were considered a Central European Iron Age phenomenon, through the cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. However, archaeological finds from the Halstatt and La Tène culture were rare in Iberia, southwestern France, northern and western Britain, southern Ireland and Galatia[67][68] and did not provide enough evidence for a culture like that of Central Europe. It is equally difficult to maintain that the origin of the Iberian Celts can be linked to the preceding Urnfield culture. This has resulted in a newer theory that introduces a ‘proto-Celtic’ substratum and a process of Celticisation, having its initial roots in the Bronze Age Bell Beaker culture.[69]

The La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC) in eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, southwest Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. It developed out of the Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under the impetus of considerable Mediterranean influence from Greek, and later Etruscan civilisations. A shift of settlement centres took place in the 4th century. The western La Tène culture corresponds to historical Celtic Gaul. Whether this means that the whole of La Tène culture can be attributed to a unified Celtic people is difficult to assess; archaeologists have repeatedly concluded that language and material culture do not necessarily run parallel. Frey notes that in the 5th century, «burial customs in the Celtic world were not uniform; rather, localised groups had their own beliefs, which, in consequence, also gave rise to distinct artistic expressions».[70] Thus, while the La Tène culture is certainly associated with the Gauls, the presence of La Tène artefacts may be due to cultural contact and does not imply the permanent presence of Celtic speakers.[citation needed]

Historical evidence

The Greek historian Ephorus of Cyme in Asia Minor, writing in the 4th century BC, believed the Celts came from the islands off the mouth of the Rhine and were «driven from their homes by the frequency of wars and the violent rising of the sea». Polybius published a history of Rome about 150 BC in which he describes the Gauls of Italy and their conflict with Rome. Pausanias in the 2nd century AD says that the Gauls «originally called Celts», «live on the remotest region of Europe on the coast of an enormous tidal sea». Posidonius described the southern Gauls about 100 BC. Though his original work is lost, later writers such as Strabo used it. The latter, writing in the early 1st century AD, deals with Britain and Gaul as well as Hispania, Italy and Galatia. Caesar wrote extensively about his Gallic Wars in 58–51 BC. Diodorus Siculus wrote about the Celts of Gaul and Britain in his 1st-century history.[citation needed]

Diodorus Siculus and Strabo both suggest that the heartland of the people they call Celts was in southern Gaul. The former says that the Gauls were to the north of the Celts, but that the Romans referred to both as Gauls (linguistically the Gauls were certainly Celts). Before the discoveries at Hallstatt and La Tène, it was generally considered that the Celtic heartland was southern Gaul, see Encyclopædia Britannica for 1813.[citation needed]

Distribution

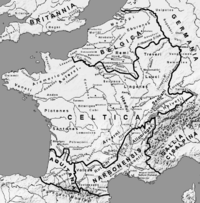

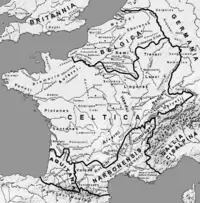

Continental

Gaul

A 4th century BC gold-plated disk from Gaul

The Romans knew the Celts then living in present-day France as Gauls. The territory of these peoples probably included the Low Countries, the Alps and present-day northern Italy. Julius Caesar in his Gallic Wars described the 1st-century BC descendants of those Gauls.[citation needed]

Eastern Gaul became the centre of the western La Tène culture. In later Iron Age Gaul, the social organisation resembled that of the Romans, with large towns. From the 3rd century BC the Gauls adopted coinage. Texts with Greek characters from southern Gaul have survived from the 2nd century BC.[71]

Greek traders founded Massalia about 600 BC, with some objects (mostly drinking ceramic vessels) being traded up the Rhône valley. But trade became disrupted soon after 500 BC and re-oriented over the Alps to the Po valley in the Italian peninsula. The Romans arrived in the Rhone valley in the 2nd century BC and encountered a mostly Celtic-speaking Gaul. Rome wanted land communications with its Iberian provinces and fought a major battle with the Saluvii at Entremont in 124–123 BC. Gradually Roman control extended, and the Roman province of Gallia Transalpina developed along the Mediterranean coast.[72][73] The Romans knew the remainder of Gaul as Gallia Comata – «Hairy Gaul».[citation needed]

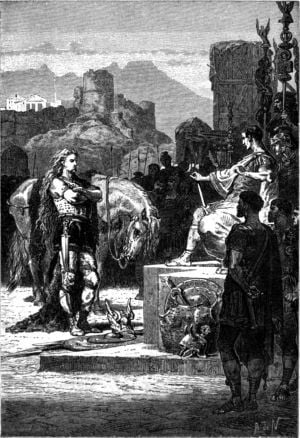

In 58 BC the Helvetii planned to migrate westward but Julius Caesar forced them back. He then became involved in fighting the various tribes in Gaul, and by 55 BC had overrun most of Gaul. In 52 BC Vercingetorix led a revolt against Roman occupation but was defeated at the Battle of Alesia and surrendered.[74]

Following the Gallic Wars of 58–51 BC, Caesar’s Celtica formed the main part of Roman Gaul, becoming the province of Gallia Lugdunensis. This territory of the Celtic tribes was bounded on the south by the Garonne and on the north by the Seine and the Marne.[75] The Romans attached large swathes of this region to neighbouring provinces Belgica and Aquitania, particularly under Augustus.[citation needed]

Place- and personal-name analysis and inscriptions suggest that Gaulish was spoken over most of what is now France.[76][77]

Iberia

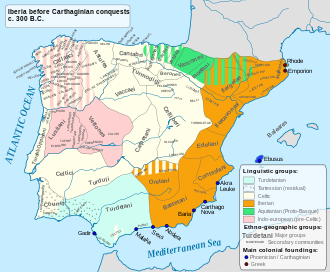

Main language areas in Iberia, showing Celtic languages in beige, c. 300 BC

Until the end of the 19th century, traditional scholarship dealing with the Celts did acknowledge their presence in the Iberian Peninsula[78][79] as a material culture relatable to the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. However, since according to the definition of the Iron Age in the 19th century Celtic populations were supposedly rare in Iberia and did not provide a cultural scenario that could easily be linked to that of Central Europe, the presence of Celtic culture in that region was generally not fully recognised. Modern scholarship, however, has clearly proven that Celtic presence and influences were most substantial in what is today Spain and Portugal (with perhaps the highest settlement saturation in Western Europe), particularly in the central, western and northern regions.[80][81]

In addition to Gauls infiltrating from the north of the Pyrenees, the Roman and Greek sources mention Celtic populations in three parts of the Iberian Peninsula: the eastern part of the Meseta (inhabited by the Celtiberians), the southwest (Celtici, in modern-day Alentejo) and the northwest (Gallaecia and Asturias).[82] A modern scholarly review[83] found several archaeological groups of Celts in Spain:

- The Celtiberian group in the Upper-Douro Upper-Tagus Upper-Jalón area.[84] Archaeological data suggest a continuity at least from the 6th century BC. In this early period, the Celtiberians inhabited in hill-forts (Castros). Around the end of the 3rd century BC, Celtiberians adopted more urban ways of life. From the 2nd century BC, they minted coins and wrote inscriptions using the Celtiberian script. These inscriptions make the Celtiberian Language the only Hispano-Celtic language classified as Celtic with unanimous agreement.[85] In the late period, before the Roman Conquest, both archaeological evidence and Roman sources suggest that the Celtiberians were expanding into different areas in the Peninsula (e.g. Celtic Baeturia).

- The Vetton group in the western Meseta, between the Tormes, Douro and Tagus Rivers. They were characterised by the production of Verracos, sculptures of bulls and pigs carved in granite.

- The Vaccean group in the central Douro valley. They were mentioned by Roman sources already in the 220 BC. Some of their funerary rituals suggest strong influences from their Celtiberian neighbours.[citation needed]

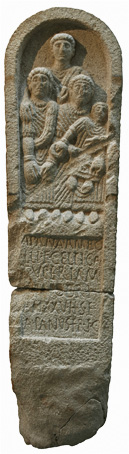

Triskelion and spirals on a Galician torc terminal, Museum of Castro de Santa Tegra, A Guarda

- The Castro Culture in northwestern Iberia, modern day Galicia and Northern Portugal.[86] Its high degree of continuity, from the Late Bronze Age, makes it difficult to support that the introduction of Celtic elements was due to the same process of Celticisation of the western Iberia, from the nucleus area of Celtiberia. Two typical elements are the sauna baths with monumental entrances, and the «Gallaecian Warriors», stone sculptures built in the 1st century AD. A large group of Latin inscriptions contain linguistic features that are clearly Celtic, while others are similar to those found in the non-Celtic Lusitanian language.[85]

- The Astures and the Cantabri. This area was romanised late, as it was not conquered by Rome until the Cantabrian Wars of 29–19 BC.

- Celts in the southwest, in the area Strabo called Celtica[87]

The origins of the Celtiberians might provide a key to understanding the Celticisation process in the rest of the Peninsula. The process of Celticisation of the southwestern area of the peninsula by the Keltoi and of the northwestern area is, however, not a simple Celtiberian question. Recent investigations about the Callaici[88] and Bracari[89] in northwestern Portugal are providing new approaches to understanding Celtic culture (language, art and religion) in western Iberia.[90]

John T. Koch of Aberystwyth University suggested that Tartessian inscriptions of the 8th century BC might be classified as Celtic. This would mean that Tartessian is the earliest attested trace of Celtic by a margin of more than a century.[91]

Germany, Alps and Italy

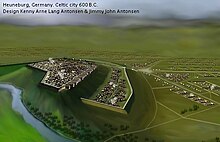

The Celtic city of Heuneburg by the Danube, Germany, c. 600 BC, the oldest city north of the Alps.[92]

Peoples of Cisalpine Gaul during the 4th to 3rd centuries BC

The Canegrate culture represented the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic[94][95] population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, had already penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore and Lake Como (Scamozzina culture). It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age, when North Westwern Italy appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artefacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture.[96] La Tène cultural material appeared over a large area of mainland Italy,[97] the southernmost example being the Celtic helmet from Canosa di Puglia.[98]

Italy is home to Lepontic, the oldest attested Celtic language (from the 6th century BC).[99] Anciently spoken in Switzerland and in Northern-Central Italy, from the Alps to Umbria.[100][101][102][103] According to the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises, more than 760 Gaulish inscriptions have been found throughout present-day France – with the notable exception of Aquitaine – and in Italy,[104][105] which testifies the importance of Celtic heritage in the peninsula.[citation needed]

In 391 BC, Celts «who had their homes beyond the Alps streamed through the passes in great strength and seized the territory that lay between the Apennine Mountains and the Alps» according to Diodorus Siculus. The Po Valley and the rest of northern Italy (known to the Romans as Cisalpine Gaul) was inhabited by Celtic-speakers who founded cities such as Milan.[106] Later the Roman army was routed at the battle of Allia and Rome was sacked in 390 BC by the Senones.[107]

At the battle of Telamon in 225 BC, a large Celtic army was trapped between two Roman forces and crushed.[108]

The defeat of the combined Samnite, Celtic and Etruscan alliance by the Romans in the Third Samnite War sounded the beginning of the end of the Celtic domination in mainland Europe, but it was not until 192 BC that the Roman armies conquered the last remaining independent Celtic kingdoms in Italy.[citation needed]

Expansion east and south

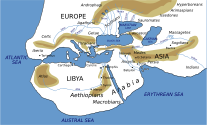

A map of Celtic invasions and migrations in the Balkans in the 3rd centuy BC

The Celts also expanded down the Danube river and its tributaries. One of the most influential tribes, the Scordisci, established their capital at Singidunum (present-day Belgrade, Serbia) in the 3rd century BC. The concentration of hill-forts and cemeteries shows a dense population in the Tisza valley of modern-day Vojvodina, Serbia, Hungary and into Ukraine. Expansion into Romania was however blocked by the Dacians.[citation needed]

The Serdi were a Celtic tribe[109] inhabiting Thrace. They were located around and founded Serdika (Bulgarian: Сердика, Latin: Ulpia Serdica, Greek: Σαρδῶν πόλις), now Sofia in Bulgaria,[110] which reflects their ethnonym. They would have established themselves in this area during the Celtic migrations at the end of the 4th century BC, though there is no evidence for their existence before the 1st century BC. Serdi are among traditional tribal names reported into the Roman era.[111] They were gradually Thracianized over the centuries but retained their Celtic character in material culture up to a late date.[when?][citation needed] According to other sources they may have been simply of Thracian origin,[112] according to others they may have become of mixed Thraco-Celtic origin. Further south, Celts settled in Thrace (Bulgaria), which they ruled for over a century, and Anatolia, where they settled as the Galatians (see also: Gallic Invasion of Greece). Despite their geographical isolation from the rest of the Celtic world, the Galatians maintained their Celtic language for at least 700 years. St Jerome, who visited Ancyra (modern-day Ankara) in 373 AD, likened their language to that of the Treveri of northern Gaul.[citation needed]

For Venceslas Kruta, Galatia in central Turkey was an area of dense Celtic settlement.[citation needed]

The Boii tribe gave their name to Bohemia, Bologna and possibly Bavaria, and Celtic artefacts and cemeteries have been discovered further east in what is now Poland and Slovakia. A Celtic coin (Biatec) from Bratislava’s mint was displayed on the old Slovak 5-crown coin.[citation needed]

As there is no archaeological evidence for large-scale invasions in some of the other areas, one current school of thought holds that Celtic language and culture spread to those areas by contact rather than invasion.[113] However, the Celtic invasions of Italy and the expedition in Greece and western Anatolia, are well documented in Greek and Latin history.[citation needed]

There are records of Celtic mercenaries in Egypt serving the Ptolemies. Thousands were employed in 283–246 BC and they were also in service around 186 BC. They attempted to overthrow Ptolemy II.[114]

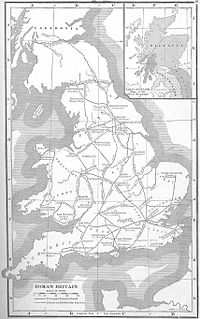

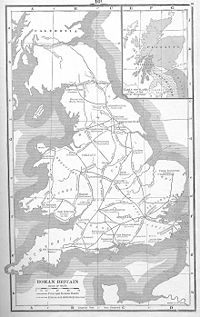

Insular

All living Celtic languages today belong to the Insular Celtic languages, derived from the Celtic languages spoken in Iron Age Britain and Ireland.[115] They separated into a Goidelic and a Brittonic branch early on. By the time of the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD, the Insular Celts were made up of the Celtic Britons, the Gaels (or Scoti), and the Picts (or Caledonians).[citation needed]

Linguists have debated whether a Celtic language came to the British Isles and then split, or whether the two branches arrived separately. The older view was that Celtic influence in the Isles was the result of successive migrations or invasions from the European mainland by diverse Celtic-speaking peoples over several centuries, accounting for the P-Celtic vs. Q-Celtic isogloss. This view has been challenged by the hypothesis that the islands’ Celtic languages form an Insular Celtic dialect group.[116] In the 19th and 20th centuries, scholars often dated the «arrival» of Celtic culture in Britain (via an invasion model) to the 6th century BC, corresponding to archaeological evidence of Hallstatt influence and the appearance of chariot burials in what is now England. Cunliffe and Koch propose in their newer #’Celtic from the West’ theory that Celtic languages reached the Isles earlier, with the Bell Beaker culture c.2500 BC, or even before this.[117][118] More recently, a major archaeogenetics study uncovered a migration into southern Britain in the Bronze Age from 1300 to 800 BC.[119] The newcomers were genetically most similar to ancient individuals from Gaul.[119] From 1000 BC, their genetic marker swiftly spread through southern Britain,[120] but not northern Britain.[119] The authors see this as a «plausible vector for the spread of early Celtic languages into Britain».[119] There was much less immigration during the Iron Age, so it is likely that Celtic reached Britain before then.[119] Cunliffe suggests that a branch of Celtic was already spoken in Britain, and the Bronze Age migration introduced the Brittonic branch.[121]

Like many Celtic peoples on the mainland, the Insular Celts followed an Ancient Celtic religion overseen by druids. Some of the southern British tribes had strong links with Gaul and Belgica, and minted their own coins. During the Roman occupation of Britain, a Romano-British culture emerged in the southeast. The Britons and Picts in the north, and the Gaels of Ireland, remained outside the empire. During the end of Roman rule in Britain in the 400s AD, there was significant Anglo-Saxon settlement of eastern and southern Britain, and some Gaelic settlement of its western coast. During this time, some Britons migrated to the Armorican peninsula, where their culture became dominant. Meanwhile, much of northern Britain (Scotland) became Gaelic. By the 10th century AD, the Insular Celtic peoples had diversified into the Brittonic-speaking Welsh (in Wales), Cornish (in Cornwall), Bretons (in Brittany) and Cumbrians (in the Old North); and the Gaelic-speaking Irish (in Ireland), Scots (in Scotland) and Manx (on the Isle of Man).[citation needed]

Classical writers did not call the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland Celtae or Κελτοί (Keltoi),[6][9][10] leading some scholars to question the use of the term ‘Celt’ for the Iron Age inhabitants of those islands.[6][9][10][11] The first historical account of the islands was by the Greek geographer Pytheas, who sailed around what he called the «Pretannikai nesoi» (the «Pretannic isles») around 310–306 BC.[122] In general, classical writers referred to the Britons as Pretannoi (in Greek) or Britanni (in Latin).[123] Strabo, writing in Roman times, distinguished between the Celts and Britons.[124] However, Roman historian Tacitus says the Britons resembled the Celts of Gaul in customs and religion.[12]

Romanisation

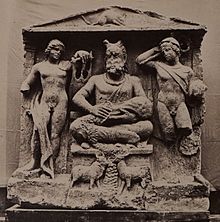

A Gallo-Roman sculpture of the Celtic god Cernunnos (middle), flanked by the Roman gods Apollo and Mercury

Under Caesar the Romans conquered Celtic Gaul, and from Claudius onward the Roman empire absorbed parts of Britain. Roman local government of these regions closely mirrored pre-Roman tribal boundaries, and archaeological finds suggest native involvement in local government.[citation needed]

The native peoples under Roman rule became Romanised and keen to adopt Roman ways. Celtic art had already incorporated classical influences, and surviving Gallo-Roman pieces interpret classical subjects or keep faith with old traditions despite a Roman overlay.[citation needed]

The Roman occupation of Gaul, and to a lesser extent of Britain, led to Roman-Celtic syncretism. In the case of the continental Celts, this eventually resulted in a language shift to Vulgar Latin, while the Insular Celts retained their language.[citation needed]

There was also considerable cultural influence exerted by Gaul on Rome, particularly in military matters and horsemanship, as the Gauls often served in the Roman cavalry. The Romans adopted the Celtic cavalry sword, the spatha, and Epona, the Celtic horse goddess.[125][126]

Society

To the extent that sources are available, they depict a pre-Christian Iron Age Celtic social structure based formally on class and kingship, although this may only have been a particular late phase of organisation in Celtic societies. Patron-client relationships similar to those of Roman society are also described by Caesar and others in the Gaul of the 1st century BC.[citation needed]

In the main, the evidence is of tribes being led by kings, although some argue that there is also evidence of oligarchical republican forms of government eventually emerging in areas which had close contact with Rome. Most descriptions of Celtic societies portray them as being divided into three groups: a warrior aristocracy; an intellectual class including professions such as druid, poet, and jurist; and everyone else. In historical times, the offices of high and low kings in Ireland and Scotland were filled by election under the system of tanistry, which eventually came into conflict with the feudal principle of primogeniture in which succession goes to the first-born son.[citation needed]

The reverse side of a British bronze mirror, with spiral and trumpet motifs typical of La Tène Celtic art in Britain

A 4th century BC Celtic gold ring from southern Germany, decorated with human and rams heads

Little is known of family structure among the Celts. Patterns of settlement varied from decentralised to urban. The popular stereotype of non-urbanised societies settled in hillforts and duns,[127] drawn from Britain and Ireland (there are about 3,000 hill forts known in Britain)[128] contrasts with the urban settlements present in the core Hallstatt and La Tène areas, with the many significant oppida of Gaul late in the first millennium BC, and with the towns of Gallia Cisalpina.[citation needed]

Slavery, as practised by the Celts, was very likely similar to the better documented practice in ancient Greece and Rome.[129] Slaves were acquired from war, raids, and penal and debt servitude.[129] Slavery was hereditary,[130] though manumission was possible. The Old Irish and Welsh words for ‘slave’, cacht and caeth respectively, are cognate with Latin captus ‘captive’ suggesting that the slave trade was an early means of contact between Latin and Celtic societies.[129] In the Middle Ages, slavery was especially prevalent in the Celtic countries.[131] Manumissions were discouraged by law and the word for «female slave», cumal, was used as a general unit of value in Ireland.[132]

There are only very limited records from pre-Christian times written in Celtic languages. These are mostly inscriptions in the Roman and sometimes Greek alphabets. The Ogham script, an Early Medieval alphabet, was mostly used in early Christian times in Ireland and Scotland (but also in Wales and England), and was only used for ceremonial purposes such as inscriptions on gravestones. The available evidence is of a strong oral tradition, such as that preserved by bards in Ireland, and eventually recorded by monasteries. Celtic art also produced a great deal of intricate and beautiful metalwork, examples of which have been preserved by their distinctive burial rites.[133]

In some regards the Atlantic Celts were conservative: for example, they still used chariots in combat long after they had been reduced to ceremonial roles by the Greeks and Romans. However, despite being outdated, Celtic chariot tactics were able to repel the invasions of Britain attempted by Julius Caesar.[134]

According to Diodorus Siculus:

The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth.

Clothing

During the later Iron Age the Gauls generally wore long-sleeved shirts or tunics and long trousers (called braccae by the Romans).[135] Clothes were made of wool or linen, with some silk being used by the rich. Cloaks were worn in the winter. Brooches[136] and armlets were used, but the most famous item of jewellery was the torc, a neck collar of metal, sometimes gold. The horned Waterloo Helmet in the British Museum, which long set the standard for modern images of Celtic warriors, is in fact a unique survival, and may have been a piece for ceremonial rather than military wear.[citation needed]

Trade and coinage

Archaeological evidence suggests that the pre-Roman Celtic societies were linked to the network of overland trade routes that spanned Eurasia. Archaeologists have discovered large prehistoric trackways crossing bogs in Ireland and Germany. Due to their substantial nature, these are believed to have been created for wheeled transport as part of an extensive roadway system that facilitated trade.[137] The territory held by the Celts contained tin, lead, iron, silver and gold.[138] Celtic smiths and metalworkers created weapons and jewellery for international trade, particularly with the Romans.[citation needed]

The myth that the Celtic monetary system consisted of wholly barter is a common one, but is in part false. The monetary system was complex and is still not understood (much like the late Roman coinages), and due to the absence of large numbers of coin items, it is assumed that «proto-money» was used. This included bronze items made from the early La Tène period and onwards, which were often in the shape of axeheads, rings, or bells. Due to the large number of these present in some burials, it is thought they had a relatively high monetary value, and could be used for «day to day» purchases. Low-value coinages of potin, a bronze alloy with high tin content, were minted in most Celtic areas of the continent and in South-East Britain prior to the Roman conquest of these lands. Higher-value coinages, suitable for use in trade, were minted in gold, silver, and high-quality bronze. Gold coinage was much more common than silver coinage, despite being worth substantially more, as while there were around 100 mines in Southern Britain and Central France, silver was more rarely mined. This was due partly to the relative sparsity of mines and the amount of effort needed for extraction compared to the profit gained. As the Roman civilisation grew in importance and expanded its trade with the Celtic world, silver and bronze coinage became more common. This coincided with a major increase in gold production in Celtic areas to meet the Roman demand, due to the high value Romans put on the metal. The large number of gold mines in France is thought to be a major reason why Caesar invaded.[citation needed]

Gender and sexual norms

Reconstruction of the dress and equipment of an Iron Age Celtic warrior from Biebertal, Germany

Very few reliable sources exist regarding Celtic views on gender roles, though some archaeological evidence suggests their views may have differed from those of the Greco-Roman world, which tended to be less egalitarian.[139][140] Some Iron Age burials in northeastern Gaul suggest women may have had roles in warfare during the earlier La Tène period, but the evidence is far from conclusive.[141] Celtic individuals buried with both female jewellery and weaponry have been found, such as the Vix Grave in northeastern Gaul, and there are questions about the gender of some individuals buried with weaponry. However, it has been suggested that the weapons indicate high social rank rather than masculinity.[142]

Most written accounts of the Ancient Celts are from the Romans and Greeks, though it is not clear how accurate these are. Roman historians Ammianus Marcellinus and Tacitus mentioned Celtic women inciting, participating in, and leading battles.[143] Plutarch reports that Celtic women acted as ambassadors to avoid a war among Celtic chiefdoms in the Po valley during the 4th century BC.[144] Posidonius’ anthropological comments on the Celts had common themes, primarily primitivism, extreme ferocity, cruel sacrificial practices, and the strength and courage of their women.[145] Cassius Dio suggests there was great sexual freedom among women in Celtic Britain:

… a very witty remark is reported to have been made by the wife of Argentocoxus, a Caledonian, to Julia Augusta. When the empress was jesting with her, after the treaty, about the free intercourse of her sex with men in Britain, she replied: «We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest». Such was the retort of the British woman.[146]

Barry Cunliffe writes that such references are «likely to be ill-observed» and meant to portray the Celts as outlandish «barbarians».[147] Historian Lisa Bitel argues the descriptions of Celtic women warriors are not credible. She says some Roman and Greek writers wanted to show that the barbarian Celts lived in «an upside-down world […] and a standard ingredient in such a world was the manly warrior woman».[148]

The Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote in his Politics that the Celts of southeastern Europe approved of male homosexuality. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote in his Bibliotheca historica that although Gaulish women were beautiful, the men had «little to do with them» and it was a custom for men to sleep on animal skins with two younger males. He further claimed that «the young men will offer themselves to strangers and are insulted if the offer is refused». His claim was later repeated by Greco-Roman writers Athenaeus and Ammianus.[149] David Rankin, in Celts and the Classical World, suggests some of these claims refer to bonding rituals in warrior groups, which required abstinence from women at certain times,[150] and says it probably reflects «the warlike character of early contacts between the Celts and the Greeks».[151]

Under Brehon Law, which was written down in early Medieval Ireland after conversion to Christianity, a woman had the right to divorce her husband and gain his property if he was unable to perform his marital duties due to impotence, obesity, homosexual inclination or preference for other women.[152][failed verification]

Celtic art

Celtic art is generally used by art historians to refer to art of the La Tène period across Europe, while the Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, that is what «Celtic art» evokes for much of the general public, is called Insular art in art history. Both styles absorbed considerable influences from non-Celtic sources, but retained a preference for geometrical decoration over figurative subjects, which are often extremely stylised when they do appear; narrative scenes only appear under outside influence. Energetic circular forms, triskeles and spirals are characteristic. Much of the surviving material is in precious metal, which no doubt gives a very unrepresentative picture, but apart from Pictish stones and the Insular high crosses, large monumental sculpture, even with decorative carving, is very rare; possibly it was originally common in wood. Celts were also able to create developed musical instruments such as the carnyces, these famous war trumpets used before the battle to frighten the enemy, as the best preserved found in Tintignac (Gaul) in 2004 and which were decorated with a boar head or a snake head.[153]

The interlace patterns that are often regarded as typical of «Celtic art» were characteristic of the whole of the British Isles, a style referred to as Insular art, or Hiberno-Saxon art. This artistic style incorporated elements of La Tène, Late Roman, and, most importantly, animal Style II of Germanic Migration Period art. The style was taken up with great skill and enthusiasm by Celtic artists in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts. Equally, the forms used for the finest Insular art were all adopted from the Roman world: Gospel books like the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne, chalices like the Ardagh Chalice and Derrynaflan Chalice, and penannular brooches like the Tara Brooch and Roscrea Brooch. These works are from the period of peak achievement of Insular art, which lasted from the 7th to the 9th centuries, before the Viking attacks sharply set back cultural life.[citation needed]

In contrast the less well known but often spectacular art of the richest earlier Continental Celts, before they were conquered by the Romans, often adopted elements of Roman, Greek and other «foreign» styles (and possibly used imported craftsmen) to decorate objects that were distinctively Celtic. After the Roman conquests, some Celtic elements remained in popular art, especially Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer, mostly in Italian styles, but also producing work in local taste, including figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalised styles. Roman Britain also took more interest in enamel than most of the Empire, and its development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe, of which the energy and freedom of Insular decoration was an important element. Rising nationalism brought Celtic revivals from the 19th century.[citation needed]

Gallic calendar

The Coligny calendar, which was found in 1897 in Coligny, Ain, was engraved on a bronze tablet, preserved in 73 fragments, that originally was 1.48 metres (4 feet 10 inches) wide and 0.9 metres (2 feet 11 inches) high (Lambert p. 111). Based on the style of lettering and the accompanying objects, it probably dates to the end of the 2nd century.[154] It is written in Latin inscriptional capitals, and is in Gaulish. The restored tablet contains 16 vertical columns, with 62 months distributed over 5 years.[citation needed]

French archaeologist J. Monard speculated that it was recorded by druids wishing to preserve their tradition of timekeeping in a time when the Julian calendar was imposed throughout the Roman Empire. However, the general form of the calendar suggests the public peg calendars (or parapegmata) found throughout the Greek and Roman world.[155]

Warfare and weapons

Tribal warfare appears to have been a regular feature of Celtic societies. While epic literature depicts this as more of a sport focused on raids and hunting rather than organised territorial conquest, the historical record is more of tribes using warfare to exert political control and harass rivals, for economic advantage, and in some instances to conquer territory.[citation needed]

The Celts were described by classical writers such as Strabo, Livy, Pausanias, and Florus as fighting like «wild beasts», and as hordes. Dionysius said that their

«manner of fighting, being in large measure that of wild beasts and frenzied, was an erratic procedure, quite lacking in military science. Thus, at one moment they would raise their swords aloft and smite after the manner of wild boars, throwing the whole weight of their bodies into the blow like hewers of wood or men digging with mattocks, and again they would deliver crosswise blows aimed at no target, as if they intended to cut to pieces the entire bodies of their adversaries, protective armour and all».[156]

Such descriptions have been challenged by contemporary historians.[157]

Polybius (2.33) indicates that the principal Celtic weapon was a long bladed sword which was used for hacking edgewise rather than stabbing. Celtic warriors are described by Polybius and Plutarch as frequently having to cease fighting in order to straighten their sword blades. This claim has been questioned by some archaeologists, who note that Noric steel, steel produced in Celtic Noricum, was famous in the Roman Empire period and was used to equip the Roman military.[158][159] However, Radomir Pleiner, in The Celtic Sword (1993) argues that «the metallographic evidence shows that Polybius was right up to a point», as around one third of surviving swords from the period might well have behaved as he describes.[160] In addition to these long bladed slashing swords, spears and specialized javelins were also used.[161]

Polybius also asserts that certain of the Celts fought naked, «The appearance of these naked warriors was a terrifying spectacle, for they were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life.»[162] According to Livy, this was also true of the Celts of Asia Minor.[163]

Head hunting

Celts had a reputation as head hunters.[164] Paul Jacobsthal says, «Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world.»[165] Writing in the first century BC, Greek historians Posidonius and Diodorus Siculus said Celtic warriors cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle, hung them from the necks of their horses, then nailed them up outside their homes.[164] Strabo wrote in the same century that Celts embalmed the heads of their most esteemed enemies in cedar oil and put them on display.[164] Roman historian Livy wrote that the Boii beheaded a defeated Roman general after the Battle of Silva Litana, covered his skull in gold, and used it as a ritual cup.[164] Archaeologists have found evidence that heads were embalmed and displayed by the southern Gauls.[166][167]

In another example, at the southern Gaulish site of Entremont, there stood a pillar carved with skulls, within which were niches where human skulls were kept, nailed into position.[168] Roquepertuse nearby has similar carved heads and skull niches. Many lone carved heads have been found in Celtic regions, some with two or three faces.[169] Examples include the Mšecké Žehrovice Head and the Corleck Head.

Severed heads are a common motif in Insular Celtic myths, and there are many tales in which ‘living heads’ preside over feasts and/or speak prophecies.[164][169] The beheading game is a motif in Irish myth and Arthurian legend, most famously in the tale Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where the Green Knight picks up his own severed head after Gawain has struck it off. There are also many legends in Celtic regions of saints who carry their own severed heads. In Irish myth, the severed heads of warriors are called the mast or nuts of the goddess Macha.[170]

Religion and mythology

Ancient Celtic religion

The Celtic «Prince of Glauberg», Germany, with a leaf crown, perhaps indicating a priest, c. 500 BC.

Like other European Iron Age societies, the Celts practised a polytheistic religion.[171] Celtic religion varied by region and over time, but had «broad structural similarities»,[171] and there was «a basic religious homogeneity» among the Celtic peoples.[172] Because the ancient Celts did not have writing, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period.[173]

The names of over two hundred Celtic deities have survived (see list of Celtic deities), although it is likely that many of these were alternative names, regional names or titles for the same deity.[171] Some deities were venerated only in one region, but others were more widely known.[171] According to Miranda Aldhouse-Green, the Celts were also animists, believing that every part of the natural world had a spirit.[173]

The Celts seem to have had a father god, who was often a god of the tribe and of the dead (Toutatis probably being one name for him); and a mother goddess who was associated with the land, earth and fertility[174] (Dea Matrona probably being one name for her). The mother goddess could also take the form of a war goddess as protectress of her tribe and its land.[174] There also seems to have been a male celestial god—identified with Taranis—associated with thunder, the wheel, and the bull.[174] There were gods of skill and craft, such as the pan-regional god Lugus, and the smith god Gobannos.[174] Celtic healing deities were often associated with sacred springs,[174] such as Sirona and Borvo. Other pan-regional deities include the horned god Cernunnos, the horse and fertility goddess Epona, the divine son Maponos, as well as Belenos, Ogmios, and Sucellos.[171][173] Caesar says the Gauls believed they all descended from a god of the dead and underworld.[171] Triplicity is a common theme in Celtic cosmology, and a number of deities were seen as threefold,[175] for example the Three Mothers.[176]

Greco-Roman writers say the Celts believed in reincarnation. Diodorus says they believed souls were reincarnated after a certain number of years, probably after spending time in an afterlife, and noted they buried grave goods with the dead.[177]

Celtic religious ceremonies were overseen by priests known as druids, who also served as judges, teachers, and lore-keepers. Other classes of druids performed sacrifices for the perceived benefit of the community.[178] There is evidence that ancient Celtic peoples sacrificed animals, almost always livestock or working animals. It appears some were offered wholly to the gods (by burying or burning), while some were shared between gods and humans (part eaten and part offered).[179] There is also some evidence that ancient Celts sacrificed humans, and some Greco-Roman sources claim the Gauls sacrificed criminals by burning them in a wicker man.[180]

The Romans said the Celts held ceremonies in sacred groves and other natural shrines, called nemetons.[171] Some Celtic peoples built temples or ritual enclosures of varying shapes (such as the Romano-Celtic temple and viereckschanze), though they also maintained shrines at natural sites.[171] Celtic peoples often made votive offerings: treasured items deposited in water and wetlands, or in ritual shafts and wells, often in the same place over generations.[171] Modern clootie wells might be a continuation of this.[181]

Insular Celtic mythology

Most surviving Celtic mythology belongs to the Insular Celtic peoples: Irish mythology has the largest written body of myths, followed by Welsh mythology. These were written down in the early Middle Ages, mainly by Christian scribes.

The supernatural race called the Tuatha Dé Danann are believed to represent the main Celtic gods of Ireland. Their traditional rivals are the Fomóire, whom they defeat in the Battle of Mag Tuired.[182] Barry Cunliffe says the underlying structure in Irish myth was a dualism between the male tribal god and the female goddess of the land.[171] The Dagda seems to have been the chief god and the Morrígan his consort, each of whom had other names.[171] One common motif is the sovereignty goddess, who represents the land and bestows sovereignty on a king by marrying him. The goddess Brigid was linked with nature as well as poetry, healing and smithing.[175]

Some figures in medieval Insular Celtic myth have ancient continental parallels: Irish Lugh and Welsh Lleu are cognate with Lugus, Goibniu and Gofannon with Gobannos, Macán and Mabon with Maponos, while Macha and Rhiannon may be counterparts of Epona.[183]

In Insular Celtic myth, the Otherworld is a parallel realm where the gods dwell. Some mythical heroes visit it by entering ancient burial mounds or caves, by going under water or across the western sea, or after being offered a silver apple branch by an Otherworld resident.[184] Irish myth says that the spirits of the dead travel to the house of Donn (Tech Duinn), a legendary ancestor; this echoes Caesar’s comment that the Gauls believed they all descended from a god of the dead and underworld.[171]

Insular Celtic peoples celebrated four seasonal festivals, known to the Gaels as Beltaine (1 May), Lughnasa (1 August), Samhain (1 November) and Imbolc (1 February).[171]

Roman influence

The Roman invasion of Gaul brought a great deal of Celtic peoples into the Roman Empire. Roman culture had a profound effect on the Celtic tribes which came under the empire’s control. Roman influence led to many changes in Celtic religion, the most noticeable of which was the weakening of the druid class, especially religiously; the druids were to eventually disappear altogether. Romano-Celtic deities also began to appear: these deities often had both Roman and Celtic attributes, combined the names of Roman and Celtic deities, and/or included couples with one Roman and one Celtic deity. Other changes included the adaptation of the Jupiter Column, a sacred column set up in many Celtic regions of the empire, primarily in northern and eastern Gaul. Another major change in religious practice was the use of stone monuments to represent gods and goddesses. The Celts had probably only created wooden cult images (including monuments carved into trees, which were known as sacred poles) before the Roman conquest.[176]

Celtic Christianity

While the regions under Roman rule adopted Christianity along with the rest of the Roman empire, unconquered areas of Ireland and Scotland began to move from Celtic polytheism to Christianity in the 5th century. Ireland was converted by missionaries from Britain, such as Saint Patrick. Later missionaries from Ireland were a major source of missionary work in Scotland, Anglo-Saxon parts of Britain, and central Europe (see Hiberno-Scottish mission). Celtic Christianity, the forms of Christianity that took hold in Britain and Ireland at this time, had for some centuries only limited and intermittent contact with Rome and continental Christianity, as well as some contacts with Coptic Christianity. Some elements of Celtic Christianity developed, or retained, features that made them distinct from the rest of Western Christianity, most famously their conservative method of calculating the date of Easter. In 664, the Synod of Whitby began to resolve these differences, mostly by adopting the current Roman practices, which the Gregorian Mission from Rome had introduced to Anglo-Saxon England.[citation needed]

Genetics

Distribution of Y-chromosomal Haplogroup R-M269 in Europe. The majority of ancient Celtic males have been found to be carriers of this lineage.[185][186][187]

Genetic studies on the limited amount of material available suggest continuity between Iron Age people from areas considered Celtic and the earlier Bell Beaker culture of Bronze Age Western Europe.[188][189][190] Like the Bell Beakers, ancient Celts carried a substantial amount of steppe ancestry, which is derived from Yamnaya pastoralists who expanded westwards from the Pontic–Caspian steppe during late Neolithic and early Bronze Age.[191] This ancestry was particularly prevalent among Celts of Northwest Europe.[190] Examined individuals overwhelmingly carry types of the paternal haplogroup R-M269,[185][186][187] while the maternal haplogroups H and U are frequent.[192][193] These lineages are associated with steppe ancestry.[185][192] The spread of Celts into Iberia and the emergence of the Celtiberians is associated with an increase in north-central European ancestry in Iberia, and may be connected to the expansion of the Urnfield culture.[194] The paternal haplogroup haplogroup I2a1a1a has been detected among Celtiberians.[195] There appears to have been significant gene flow among Celtic peoples of Western Europe during the Iron Age.[196][190] While the Gauls of southern France display genetic links with the Celtiberians, the Gauls of northern France display links with Great Britain and Sweden.[197] Modern populations of Western Europe, particularly those who still speak Celtic languages, display substantial genetic continuity with the Iron Age populations of the same areas.[198][199][200]

See also

- List of ancient Celtic peoples and tribes

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Celtic F.C., soccer club in Glasgow

References

Citations

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 144. «CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic

- ^ Mac Cana & Dillon. «The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apogee of their influence and territorial expansion during the 4th century bc, extending across the length of Europe from Britain to Asia Minor.»; Puhvel, Fee & Leeming 2003, p. 67. «[T]he Celts, were Indo-Europeans, a fact that explains a certain compatibility between Celtic, Roman, and Germanic mythology.»; Riché 2005, p. 150. «The Celts and Germans were two Indo-European groups whose civilizations had some common characteristics.»; Todd 1975, p. 42. «Celts and Germans were of course derived from the same Indo-European stock.»; Encyclopedia Britannica. Celt. «Celt, also spelled Kelt, Latin Celta, plural Celtae, a member of an early Indo-European people who from the 2nd millennium bce to the 1st century bce spread over much of Europe.»;

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2012, p. 295. «Celts, a name applied by ancient writers to a population group occupying lands mainly north of the Mediterranean region from Galicia in the west to Galatia in the east. (Its application to the Welsh, the Scots, and the Irish is modern.) Their unity is recognizable by common speech and common artistic traditions.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 144. «Celts, in its modern usage, is an encompassing term referring to all Celtic-speaking peoples.»

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. Celt. «Celt, also spelled Kelt, Latin Celta, plural Celtae, a member of an early Indo-European people who from the 2nd millennium bce to the 1st century bce spread over much of Europe. Their tribes and groups eventually ranged from the British Isles and northern Spain to as far east as Transylvania, the Black Sea coasts, and Galatia in Anatolia and were in part absorbed into the Roman Empire as Britons, Gauls, Boii, Galatians, and Celtiberians. Linguistically they survive in the modern Celtic speakers of Ireland, Highland Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, and Brittany.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. xix–xxi. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

This Encyclopedia is designed for the use of everyone interested in Celtic studies and also for those interested in many related and subsidiary fields, including the individual CELTIC COUNTRIES and their languages, literatures, archaeology, folklore, and mythology. In its chronological scope, the Encyclopedia covers subjects from the HALLSTATT and LA TENE periods of the later pre-Roman Iron Age to the beginning of the 21st century.

- ^ Luján, E. R. (2006). «PUEBLOS CELTAS Y NO CELTAS DE LA GALICIA ANTIGUA: FUENTES LITERARIAS FRENTE A FUENTES EPIGRÁFICAS» (PDF). Xxii seminario de lenguas y epigrafía antigua. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ «If, as is the first criterion of this Encyclopedia, one bases the concept of ‘Celticity’ on language, one can apply the term ‘Celtic’ to ancient Galicia», Koch, John T., ed. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 790. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ a b c d e f James, Simon (1999). The Atlantic Celts – Ancient People or Modern Invention. University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ a b c d e Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2913-7.

- ^ a b c Pryor, Francis (2004). Britain BC. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-712693-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sims-Williams (August 2020). «An Alternative to ‘Celtic from the East’ and ‘Celtic from the West’«. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 30 (3): 511–529. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000098.

- ^ Louwen, A.J (2021). Breaking and making the ancestors. Piecing together the urnfield mortuary process in the Lower-Rhine-Basin, ca. 1300 — 400 BC (PhD). Leiden University.

- ^ Probst 1996, pp. 258.

- ^ a b c d Chadwick, Nora; Corcoran, J. X. W. P. (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 28–33.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (1997). The Ancient Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 39–67.

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic – see map 9.3 The Ancient Celtic Languages c. 440/430 BC – see third map in PDF at URL provided which is essentially the same map (PDF). Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic – see map 9.2 Celtic expansion from Hallstatt/La Tene central Europe – see second map in PDF at URL provided which is essentially the same map (PDF). Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ^ Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). pp. 24–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2011.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts – a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-280418-1.

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7.

The Cornish are related to the other Celtic peoples of Europe, the Bretons,* Irish,* Scots,* Manx,* Welsh,* and the Galicians* of northwestern Spain

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 766. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7.

Celts, 257, 278, 523, 533, 555, 643; Bretons, 129–33; Cornish, 178–81; Galicians, 277–80; Irish, 330–37; Manx, 452–55; Scots, 607–12; Welsh

- ^ McKevitt, Kerry Ann (2006). «Mythologizing Identity and History: a look at the Celtic past of Galicia» (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 651–73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Sarunas Milisauskas, European prehistory: a survey. Springer. 2002. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-306-47257-2. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ H. D. Rankin, Celts and the classical world. Routledge. 1998. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-415-15090-3. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, 2.33; 4.49.

- ^ John T. Koch (ed.), Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. 5 vols. 2006. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, p. 371.

- ^ a b McCone, Kim (2013). «The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity», in Ireland and its Contacts. University of Lausanne. pp.21–27

- ^ P. De Bernardo Stempel 2008. «Linguistically Celtic ethnonyms: towards a classification», in Celtic and Other Languages in Ancient Europe, J. L. García Alonso (ed.), 101–18. Ediciones Universidad Salamanca.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.1: «All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae live, another in which the Aquitani live, and the third are those who in their own tongue are called Celtae, in our language Galli.»

- ^ Strabo, Geography, 3.1.3; 3.1.6; 3.2.2; 3.2.15; 4.4.2.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History 21: «the Mirobrigenses, surnamed Celtici» («Mirobrigenses qui Celtici cognominantur»).

- ^ «España» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Fernando De Almeida, Breve noticia sobre o santuário campestre romano de Miróbriga dos Celticos (Portugal): D(IS) M(ANIBUS) S(ACRUM) / C(AIUS) PORCIUS SEVE/RUS MIROBRIGEN(SIS) / CELT(ICUS) ANN(ORUM) LX / H(IC) S(ITUS) E(ST) S(IT) T(IBI) T(ERRA) L(EVIS).

- ^ Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 794–95. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ^ Spencer and Zwicky, Andrew and Arnold M (1998). The handbook of morphology. Blackwell Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-631-18544-4.

- ^ Lhuyd, E. Archaeologia Britannica; An account of the languages, histories, and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain. (reprint ed.) Irish University Press, 1971, p. 290. ISBN 0-7165-0031-0.

- ^ Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 532. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ^ Mountain, Harry (1998). The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume 1. uPublish.com. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-58112-889-5.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas; et al. (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 95–102.

- ^ Paul Graves-Brown, Siân Jones, Clive Gamble, Cultural identity and archaeology: the construction of European communities, pp. 242–244. Routledge. 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-10676-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Carl McColman, The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Books. 2003. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-0-02-864417-2. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Monaghan, Patricia (2008). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Facts on File Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-7556-0.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts with an introductory chapter by J.X.W.P. Corcoran. Penguin Books. p. 81.

- ^ «Celtic language Branch — Origins & Classification — MustGo». MustGo.com. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ John T. Koch (2006). Celtic culture : a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 34, 365–366, 529, 973, 1053. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. OCLC 62381207.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts. p. 30.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 89–102.

- ^ Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages — Addenda. p. 25.

- ^ a b c Koch, John (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 386.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2007). The Origins of the British. Robinson. pp. 21–56.

- ^ Myles Dillon and Nora Kershaw Chadwick, The Celtic Realms, 1967, 18–19

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 1: Celticization from the West – The Contribution of Archaeology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ 2001 p 95. La lengua de los Celtas y otros pueblos indoeuropeos de la península ibérica. In Almagro-Gorbea, M., Mariné, M. and Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. (eds) Celtas y Vettones, pp. 115–21. Ávila: Diputación Provincial de Ávila.

- ^ Lorrio and Ruiz Zapatero, Alberto J. and Gonzalo (2005). «The Celts in Iberia: An Overview». E-Keltoi. 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula: 167–254. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Koch, John (2009). «Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9» (PDF). Palaeohispánica: Revista Sobre Lenguas y Culturas de la Hispania Antigua. Palaeohispanica: 339–51. ISSN 1578-5386. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 75. The Prehistoric Society. pp. 55–64 [61].

- ^ Sims-Williams, Patrick (2 April 2020). «An Alternative to ‘Celtic from the East’ and ‘Celtic from the West’«. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 30 (3): 511–529. doi:10.1017/s0959774320000098. ISSN 0959-7743. S2CID 216484936.

- ^ Hoz, J. de (28 February 2019), «Method and methods», Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies, Oxford University Press, pp. 1–24, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790822.003.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-879082-2, retrieved 29 May 2021

- ^ e.g. Patrick Sims-Williams, Ancient Celtic Placenames in Europe and Asia Minor, Publications of the Philological Society, No. 39 (2006);