Asked by: Russel Rosenbaum V

Score: 4.9/5

(70 votes)

One who, or that which, categorizes.

Is it categorized or Categorised?

As nouns the difference between categorisation and categorization. is that categorisation is (british spelling) while categorization is a group of things arranged by category; a classification.

What is it called when you categorize someone?

Thinking about others in terms of their group memberships is known as social categorization—the natural cognitive process by which we place individuals into social groups. … Just as we categorize objects into different types, so do we categorize people according to their social group memberships.

What is the opposite of categorize?

Opposite of to sort or divide into classes or categories. scatter. disorganize. disorder. disarrange.

Is miscategorized a real word?

Simple past tense and past participle of miscategorize.

41 related questions found

What does Miscategorization mean?

: an act or instance of wrongly assigning someone or something to a group or category : incorrect classification Cracking down on the misclassification of workers so that those mislabeled as «independent contractors» can become unionizable employees.— Harold Meyerson.

What does the word miscategorized mean?

Verb. Past tense for to categorize incorrectly.

What is uncategorized?

Definitions of uncategorized. adjective. not categorized or sorted. synonyms: uncategorised, unsorted unclassified. not arranged in any specific grouping.

What are synonyms for categorize?

categorize

- assort,

- break down,

- class,

- classify,

- codify,

- compartment,

- compartmentalize,

- digest,

What is it called when you send someone in your place?

Relegate rhymes with delegate — both words derive from the Latin legare, «to send.» Relegate means to send someone down in rank. Delegate means to send someone in your place to complete a task.

What is the word for putting things in order?

Some common synonyms of order are arrange, marshal, methodize, organize, and systematize. While all these words mean «to put persons or things into their proper places in relation to each other,» order suggests a straightening out so as to eliminate confusion.

What is grouping things together called?

Answer: sorting is process of grouping similar things together.

Is British categorized?

Non-Oxford British English standard spelling of categorize.

How do you use categorize in a sentence?

Categorize in a Sentence ?

- I decided to categorize this homework as math because it has a lot of math in it despite being assigned by the science teacher.

- We categorize the different aspects of our education into different subjects to make them easier to deal with.

What can I say instead of has?

Synonyms & Antonyms of has

- commands,

- enjoys,

- holds,

- owns,

- possesses,

- retains.

What word can I use instead of would?

synonyms for would

- authorize.

- bid.

- decree.

- enjoin.

- exert.

- intend.

- request.

- resolve.

What is uncategorized income?

Uncategorized income is nothing but an account created by Intuit, founder of QuickBooks for the bank feed process. Basically, QuickBooks automatically creates uncategorized income and uncategorized expenses when opening balances are entered for customers or vendors.

What is an uncategorized asset?

When you create all business bank and credit card accounts created in QBO, you can correctly record transfers to them and avoid the potential error of a Transfer to an Uncategorized Asset. … This means that you would categorize the transfer to your Owner Draw or Owner Pay and Personal Expenses account.

What is an uncategorized transaction?

If you see an Uncategorized Transactions category in your budget, it means you have transactions in your accounts that need to be reviewed and categorized. Like a brand new Payee, and you’re telling YNAB how to categorize it now—and in the future for automatic categorization.

How do you spell misclassification?

mis·clas·si·fy

To classify incorrectly. mis·clas′si·fi·ca′tion (-fĭ-kā′shən) n.

What is a misclassification error?

The misclassification error refer to the number of individual that we know that bellow to a category that are classified by the method in a different category.

What is non-differential misclassification?

Non-differential misclassification occurs if there is equal misclassification of exposure between subjects that have or do not have the health outcome or if there is equal misclassification of the health outcome between exposed and unexposed subjects.

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

Musicians exist independent of any of the marketing terms or the categorization.

Dwight Yoakam

PRONUNCIATION OF CATEGORIZATION

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF CATEGORIZATION

Categorization is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES CATEGORIZATION MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Categorization

Categorization is the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood. Categorization implies that objects are grouped into categories, usually for some specific purpose. Ideally, a category illuminates a relationship between the subjects and objects of knowledge. Categorization is fundamental in language, prediction, inference, decision making and in all kinds of environmental interaction. It is indicated that categorization plays a major role in computer programming. There are many categorization theories and techniques. In a broader historical view, however, three general approaches to categorization may be identified: ▪ Classical categorization ▪ Conceptual clustering ▪ Prototype theory…

Definition of categorization in the English dictionary

The definition of categorization in the dictionary is the act of placing in a category; classification.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH CATEGORIZATION

Synonyms and antonyms of categorization in the English dictionary of synonyms

Translation of «categorization» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF CATEGORIZATION

Find out the translation of categorization to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of categorization from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «categorization» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

分类

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

वर्गीकरण

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

تصنيف

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

категоризация

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

categorização

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

শ্রেণীবদ্ধকরণ

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Pengkategorian

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

カテゴリー化

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

분류

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Kategorisasi

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

phân loại

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

वर्गीकरण

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

kategorizasyon

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

kategoryzacja

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

категоризація

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

clasificare

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

κατηγοριοποίηση

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

kategorisering

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

kategorisering

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

kategorisering

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of categorization

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «CATEGORIZATION»

The term «categorization» is quite widely used and occupies the 34.619 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Quite widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «categorization» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of categorization

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «categorization».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «CATEGORIZATION» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «categorization» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «categorization» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about categorization

8 QUOTES WITH «CATEGORIZATION»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word categorization.

Every time a new rock singer comes out they don’t say, ‘Are you the new John Lennon?’ Every time a new rapper comes out, it’s not, ‘Are you the new Dre?’ I am never sure why this sort of genre, the categorization is so strong. I have not earned the right to be called the young Sinatra, but give me time.

But Saudi Arabia is surprising in a lot of ways. Like any place, or any people, it relentlessly defies easy categorization.

Measurement and categorization are, of course, fundamental to any scientific endeavor, but the implications of being able to identify psychopaths are as much practical as academic. To put it simply, if we can’t spot them, we are doomed to be their victims, both as individuals and as a society.

I consider skateboarding an art form, a lifestyle and a sport. ‘Action sport’ would be the least offensive categorization.

I have worked really hard to defy categorization, to break down a taxonomy whenever it comes my way.

At Mint, we developed five pending patents on our technology, ranging from categorization to the Ways to Save system that calculates how much a new financial product would save a user given their present financial situation.

I believe that the development of language — of naming, categorization, conceptualization — destroys our ability to see as we age.

Musicians exist independent of any of the marketing terms or the categorization.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «CATEGORIZATION»

Discover the use of categorization in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to categorization and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science

The Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science provides just the sort of interdisciplinary approach that is necessary to synthesize knowledge from the different fields and provide the basis for future innovation.

Henri Cohen, Claire Lefebvre, 2005

2

Categorization in Social Psychology

Categorization in Social Psychology offers a major introduction to the study of categorization, looking especially at links between categorization in cognitive and social psychology.

3

Categorization and Naming in Children: Problems of Induction

In this landmark work on early conceptual and lexical development, Ellen Markman challenges the fundamental assumptions of traditional theories of language acquisition and proposes a new notion of how children acquire categories.

4

Noun Classes and Categorization: Proceedings of a Symposium …

This volume is about the nature of categories in cognition and the relevance of these in language description, especially classifier systems.

Colette Grinevald Craig, 1986

5

Linguistic Categorization

This book provides a readable and clearly articulated introduction to the field of Cognitive Linguistics.

6

Multiple Social Categorization: Processes, Models and …

In this volume, Richard Crisp and Miles Hewstone bring together a selection of leading figures in the social sciences to focus on a rapidly emerging, but critically important, new question: how, when, and why do people classify others along …

Richard J. Crisp, Miles Hewstone, 2007

7

Formal Approaches in Categorization

But what are the mechanisms which correspond to psychological categorization processes? This book unites many prominent approaches in modelling categorization.

Emmanuel M. Pothos, Andy J. Wills, 2011

8

Categorization in the History of English

Printbegrænsninger: Der kan printes 10 sider ad gangen og max. 40 sider pr. session

Christian Kay, Jeremy J. Smith, 2004

9

Culture in Action: Studies in Membership Categorization Analysis

This collection of new studies in ethnomethodology addresses sociology’s classical questions by developing that strand of ethnomethodological inquiry dealing with membership categorization.

Stephen Hester, Peter Eglin, 1997

The book will also be of interest to researchers from related fields who have an interest in visual processing.

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «CATEGORIZATION»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term categorization is used in the context of the following news items.

PlayStation Now’s streaming app wants to be Netflix for games

«We built a new categorization for the games; the actual navigational paradigms are different, the product detail scene is different,» Stevenson … «Engadget, Jul 15»

When does design become ‘too advanced’?

For example, you might change the categorization of a few site pages, A/B test it with some users, and then a few months later introduce a new … «The Next Web, Jul 15»

Uber Seeks Police Protection in Johannesburg

Uber, he said, should operate under the same category of license they are subjected to, rather than the charter service categorization the … «Wall Street Journal, Jul 15»

Carowinds’ Fury 325 makes global list of ‘Totally Terrifying Coasters’

That categorization refers to roller coasters that are between 300 and 399 feet tall. Carowinds opened Fury 325 in March to much fanfare. «Charlotte Business Journal, Jul 15»

’80s Invasion’ Star Midge Ure Tells HuffPostUK Why The 1980s Had …

“I’ve never adhered to categorization,” he tells us. “I always found it easy to cross over.” But he thinks there was a delightful naivety to those … «Huffington Post UK, Jul 15»

10 keys to successful machine learning for developers

… the accuracy between GBT and the linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm on the popular text categorization dataset rcv1. «InfoWorld, Jul 15»

US obsession with race hits close to home

Unfortunately, her love of a race different from her own, to the extent of claiming it, does not fit our national obsession with racial categorization. «St. Cloud Times, Jul 15»

Form 10-Q Merecot Corp. For: Mar 31

If the inputs used to measure the financial assets and liabilities fall within more than one level described above, the categorization is based on … «StreetInsider.com, Jul 15»

Child’s death raises issues of gun safety, criminal prosecution

Discrepancies in reporting and categorization make accurately tracking the number of these accidental incidents difficult, and no national … «Houston Chronicle, Jul 15»

Causing and Condoning Sinful Behavior: Part IV

The same bureau recently reported that the marriage rate for the same categorization of American adults showed only 50.3% were married and … «Patriot Post, Jul 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Categorization [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/categorization>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

Categorization is the ability and activity of recognizing shared features or similarities between the elements of the experience of the world (such as objects, events, or ideas), organizing and classifying experience by associating them to a more abstract group (that is, a category, class, or type),[1][2] on the basis of their traits, features, similarities or other criteria that are universal to the group. Categorization is considered one of the most fundamental cognitive abilities, and as such it is studied particularly by psychology and cognitive linguistics.

Categorization is sometimes considered synonymous with classification (cf., Classification synonyms). Categorization and classification allow humans to organize things, objects, and ideas that exist around them and simplify their understanding of the world.[3] Categorization is something that humans and other organisms do: «doing the right thing with the right kind of thing.» The activity of categorizing things can be nonverbal or verbal. For humans, both concrete objects and abstract ideas are recognized, differentiated, and understood through categorization. Objects are usually categorized for some adaptive or pragmatic purposes.

Categorization is grounded in the features that distinguish the category’s members from nonmembers. Categorization is important in learning, prediction, inference, decision making, language, and many forms of organisms’ interaction with their environments.

Overview of categorization[edit]

Categories are distinct collections of concrete or abstract instances (category members) that are considered equivalent by the cognitive system. Using category knowledge requires one to access mental representations that define the core features of category members (cognitive psychologists refer to these category-specific mental representations as concepts).[4][5]

To categorization theorists, the categorization of objects is often considered using taxonomies with three hierarchical levels of abstraction.[6] For example, a plant could be identified at a high level of abstraction by simply labeling it a flower, a medium level of abstraction by specifying that the flower is a rose, or a low level of abstraction by further specifying this particular rose as a dog rose. Categories in a taxonomy are related to one another via class inclusion, with the highest level of abstraction being the most inclusive and the lowest level of abstraction being the least inclusive.[6] The three levels of abstraction are as follows:

- Superordinate level, Genus (e.g., Flower) — The highest and most inclusive level of abstraction. Exhibits the highest degree of generality and the lowest degree of within-category similarity.[7]

- Basic Level, Species (e.g., Rose) — The middle level of abstraction. Rosch and colleagues (1976) suggest the basic level to be the most cognitively efficient.[6] Basic level categories exhibit high within-category similarities and high between-category dissimilarities. Furthermore, the basic level is the most inclusive level at which category exemplars share a generalized identifiable shape.[6] Adults most-often use basic level object names, and children learn basic object names first.[6]

- Subordinate level (e.g., Dog Rose) — The lowest level of abstraction. Exhibits the highest degree of specificity and within-category similarity.[7]

Theories of categorization[edit]

Classical view[edit]

The classical theory of categorization, is a term used in cognitive linguistics to denote the approach to categorization that appears in Plato and Aristotle and that has been highly influential and dominant in Western culture, particularly in philosophy, linguistics and psychology.[8][9] Aristotle’s categorical method of analysis was transmitted to the scholastic medieval university through Porphyry’s Isagoge. The classical view of categories can be summarized into three assumptions: a category can be described as a list of necessary and sufficient features that its membership must have, categories are discrete in that they have clearly defined boundaries (either an element belongs to one or not, with no possibilities in between), and all the members of a category have the same status. (There are no members of the category which belong more than others).[1][10][page needed][8] In the classical view, categories need to be clearly defined, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive; this way, any entity in the given classification universe belongs unequivocally to one, and only one, of the proposed categories.[citation needed]

The classical view of categories first appeared in the context of Western Philosophy in the work of Plato, who, in his Statesman dialogue, introduces the approach of grouping objects based on their similar properties. This approach was further explored and systematized by Aristotle in his Categories treatise, where he analyzes the differences between classes and objects. Aristotle also applied intensively the classical categorization scheme in his approach to the classification of living beings (which uses the technique of applying successive narrowing questions such as «Is it an animal or vegetable?», «How many feet does it have?», «Does it have fur or feathers?», «Can it fly?»…), establishing this way the basis for natural taxonomy.

Examples of the use of the classical view of categories can be found in the western philosophical works of Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Spinoza and John Locke, and in the 20th century in Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, the logical positivists. It has been a cornerstone of analytic philosophy and its conceptual analysis, with more recent formulations proposed in the 1990s by Frank Cameron Jackson and Christopher Peacocke.[11][12][13] At the beginning of the 20th century, the question of categories was introduced into the empirical social sciences by Durkheim and Mauss, whose pioneering work has been revisited in contemporary scholarship.[14][15]

The classical model of categorization has been used at least since the 1960s from linguists of the structural semantics paradigm, by Jerrold Katz and Jerry Fodor in 1963, which in turn have influenced its adoption also by psychologists like Allan M. Collins and M. Ross Quillian.[1][16]

Modern versions of classical categorization theory study how the brain learns and represents categories by detecting the features that distinguish members from nonmembers.[17][18]

Prototype theory[edit]

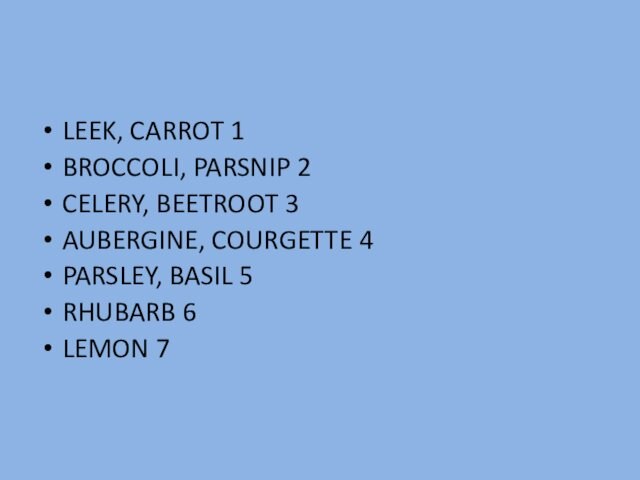

The pioneering research by psychologist Eleanor Rosch and colleagues since 1973, introduced the prototype theory, according to which categorization can also be viewed as the process of grouping things based on prototypes. This approach has been highly influential, particularly for cognitive linguistics.[1] It was in part based on previous insights, in particular the formulation of a category model based on family resemblance by Wittgenstein (1953), and by Roger Brown’s How shall a thing be called? (1958).[1]

Prototype theory has been then adopted by cognitive linguists like George Lakoff. The prototype theory is an example of a similarity-based approach to categorization, in which a stored category representation is used to assess the similarity of candidate category members.[19] Under the prototype theory, this stored representation consists of a summary representation of the category’s members. This prototype stimulus can take various forms. It might be a central tendency that represents the category’s average member, a modal stimulus representing either the most frequent instance or a stimulus composed of the most common category features, or, lastly, the «ideal» category member, or a caricature that emphasizes the distinct features of the category.[20] An important consideration of this prototype representation is that it does not necessarily reflect the existence of an actual instance of the category in the world.[20] Furthermore, prototypes are highly sensitive to context.[21] For example, while one’s prototype for the category of beverages may be soda or seltzer, the context of brunch might lead them to select mimosa as a prototypical beverage.

The prototype theory claims that members of a given category share a family resemblance, and categories are defined by sets of typical features (as opposed to all members possessing necessary and sufficient features).[22]

Exemplar theory[edit]

Another instance of the similarity-based approach to categorization, the exemplar theory likewise compares the similarity of candidate category members to stored memory representations. Under the exemplar theory, all known instances of a category are stored in memory as exemplars. When evaluating an unfamiliar entity’s category membership, exemplars from potentially relevant categories are retrieved from memory, and the entity’s similarity to those exemplars is summed to formulate a categorization decision.[20] Medin and Schaffer’s (1978) Context model employs a nearest neighbor approach which, rather than summing an entity’s similarities to relevant exemplars, multiplies them to provide weighted similarities that reflect the entity’s proximity to relevant exemplars.[23] This effectively biases categorization decisions towards exemplars most similar to the entity to be categorized.[23][24]

Conceptual clustering[edit]

Conceptual clustering is a machine learning paradigm for unsupervised classification that was defined by Ryszard S. Michalski in 1980.[25][26] It is a modern variation of the classical approach of categorization, and derives from attempts to explain how knowledge is represented. In this approach, classes (clusters or entities) are generated by first formulating their conceptual descriptions and then classifying the entities according to the descriptions.[27]

Conceptual clustering developed mainly during the 1980s, as a machine paradigm for unsupervised learning. It is distinguished from ordinary data clustering by generating a concept description for each generated category.

Conceptual clustering is closely related to fuzzy set theory, in which objects may belong to one or more groups, in varying degrees of fitness. A cognitive approach accepts that natural categories are graded (they tend to be fuzzy at their boundaries) and inconsistent in the status of their constituent members. The idea of necessary and sufficient conditions is almost never met in categories of naturally occurring things.

Category learning[edit]

While an exhaustive discussion of category learning is beyond the scope of this article, a brief overview of category learning and its associated theories is useful in understanding formal models of categorization.

If categorization research investigates how categories are maintained and used, the field of category learning seeks to understand how categories are acquired in the first place. To accomplish this, researchers often employ novel categories of arbitrary objects (e.g., dot matrices) to ensure that participants are entirely unfamiliar with the stimuli.[28] Category learning researchers have generally focused on two distinct forms of category learning. Classification learning tasks participants with predicting category labels for a stimulus based on its provided features. Classification learning is centered around learning between-category information and the diagnostic features of categories.[29] In contrast, inference learning tasks participants with inferring the presence/value of a category feature based on a provided category label and/or the presence of other category features. Inference learning is centered on learning within-category information and the category’s prototypical features.[29]

Category learning tasks can generally be divided into two categories, supervised and unsupervised learning. Supervised learning tasks provide learners with category labels. Learners then use information extracted from labeled example categories to classify stimuli into the appropriate category, which may involve the abstraction of a rule or concept relating observed object features to category labels. Unsupervised learning tasks do not provide learners with category labels. Learners must therefore recognize inherent structures in a data set and group stimuli together by similarity into classes. Unsupervised learning is thus a process of generating a classification structure. Tasks used to study category learning take various forms:

- Rule-based tasks present categories that participants can learn through explicit reasoning processes. In these kinds of tasks, classification of stimuli is accomplished via the use of an acquired rule (i.e., if stimulus is large on dimension x, respond A).

- Information-integration tasks require learners to synthesize perceptual information from multiple stimulus dimensions prior to making categorization decisions. Unlike rule-based tasks, information-integration tasks do not afford rules that are easily articulable. Reading an X-ray and trying to determine if a tumor is present can be thought of as a real-world instantiation of an information-integration task.

- Prototype distortion tasks require learners to generate a prototype for a category. Candidate exemplars for the category are then produced by randomly manipulating the features of the prototype, which learners must classify as either belonging to the category or not.

Category learning theories[edit]

Category learning researchers have proposed various theories for how humans learn categories.[30] Prevailing theories of category learning include the prototype theory, the exemplar theory, and the decision bound theory.[28]

The prototype theory suggests that to learn a category, one must learn the category’s prototype. Subsequent categorization of novel stimuli is then accomplished by selecting the category with the most similar prototype.[28]

The exemplar theory suggests that to learn a category, one must learn about the exemplars that belong to that category. Subsequent categorization of a novel stimulus is then accomplished by computing its similarity to the known exemplars of potentially relevant categories and selecting the category that contains the most similar exemplars.[23]

Decision bound theory suggests that to learn a category, one must either learn the regions of a stimulus space associated with particular responses or the boundaries (the decision bounds) that divide these response regions. Categorization of a novel stimulus is then accomplished by determining which response region it is contained within.[31]

Formal models of categorization[edit]

Computational models of categorization have been developed to test theories about how humans represent and use category information.[20] To accomplish this, categorization models can be fit to experimental data to see how well the predictions afforded by the model line up with human performance. Based on the model’s success at explaining the data, theorists are able to draw conclusions about the accuracy of their theories and their theory’s relevance to human category representations.

To effectively capture how humans represent and use category information, categorization models generally operate under variations of the same three basic assumptions.[32][20] First, the model must make some kind of assumption about the internal representation of the stimulus (e.g., representing the perception of a stimulus as a point in a multi-dimensional space).[32] Second, the model must make an assumption about the specific information that needs to be accessed in order to formulate a response (e.g., exemplar models require the collection of all available exemplars for each category).[23] Third, the model must make an assumption about how a response is selected given the available information.[32]

Though all categorization models make these three assumptions, they distinguish themselves by the ways in which they represent and transform an input into a response representation.[20] The internal knowledge structures of various categorization models reflect the specific representation(s) they use to perform these transformations. Typical representations employed by models include exemplars, prototypes, and rules.[20]

- Exemplar models store all distinct instances of stimuli with their corresponding category labels in memory. Categorization of subsequent stimuli is determined by the stimulus’ collective similarity to all known exemplars.

- Prototype models store a summary representation of all instances in a category. Categorization of subsequent stimuli is determined by selecting the category whose prototype is most similar to the stimulus.

- Rule-based models define categories by storing summary lists of the necessary and sufficient features required for category membership. Boundary models can be considered as atypical rule models, as they do not define categories based on their content. Rather, boundary models define the edges (boundaries) between categories, which subsequently serve as determinants for how a stimulus gets categorized.

Examples of categorization models[edit]

Prototype models[edit]

Weighted Features Prototype Model[19] An early instantiation of the prototype model was produced by Reed in the early 1970s. Reed (1972) conducted a series of experiments to compare the performance of 18 models on explaining data from a categorization task that required participants to sort faces into one of two categories.[19] Results suggested that the prevailing model was the weighted features prototype model, which belonged to the family of average distance models. Unlike traditional average distance models, however, this model differentially weighted the most distinguishing features of the two categories. Given this model’s performance, Reed (1972) concluded that the strategy participants used during the face categorization task was to construct prototype representations for each of the two categories of faces and categorize test patterns into the category associated with the most similar prototype. Furthermore, results suggested that similarity was determined by each categories most discriminating features.

Exemplar models[edit]

Generalized Context Model[33] Medin and Schaffer’s (1978) context model was expanded upon by Nosofsky (1986) in the mid-1980’s, resulting in the production of the Generalized Context Model (GCM).[33] The GCM is an exemplar model that stores exemplars of stimuli as exhaustive combinations of the features associated with each exemplar.[20] By storing these combinations, the model establishes contexts for the features of each exemplar, which are defined by all other features with which that feature co-occurs. The GCM computes the similarity of an exemplar and a stimulus in two steps. First, the GCM computes the psychological distance between the exemplar and the stimulus. This is accomplished by summing the absolute values of the dimensional difference between the exemplar and the stimulus. For example, suppose an exemplar has a value of 18 on dimension X and the stimulus has a value of 42 on dimension X; the resulting dimensional difference would be 24. Once psychological distance has been evaluated, an exponential decay function determines the similarity of the exemplar and the stimulus, where a distance of 0 results in a similarity of 1 (which begins to decrease exponentially as distance increases). Categorical responses are then generated by evaluating the similarity of the stimulus to each category’s exemplars, where each exemplar provides a «vote»[20] to their respective categories that varies in strength based on the exemplar’s similarity to the stimulus and the strength of the exemplar’s association with the category. This effectively assigns each category a selection probability that is determined by the proportion of votes it receives, which can then be fit to data.

Rule-based models[edit]

RULEX (Rule-Plus-Exception) Model[34] While simple logical rules are ineffective at learning poorly defined category structures, some proponents of the rule-based theory of categorization suggest that an imperfect rule can be used to learn such category structures if exceptions to that rule are also stored and considered. To formalize this proposal, Nosofsky and colleagues (1994) designed the RULEX model. The RULEX model attempts to form a decision tree[35] composed of sequential tests of an object’s attribute values. Categorization of the object is then determined by the outcome of these sequential tests. The RULEX model searches for rules in the following ways:[36]

- Exact Search for a rule that uses a single attribute to discriminate between classes without error.

- Imperfect Search for a rule that uses a single attribute to discriminate between classes with few errors

- Conjunctive Search for a rule that uses multiple attributes to discriminate between classes with few errors.

- Exception Search for exceptions to the rule.

The method that RULEX uses to perform these searches is as follows:[36] First, RULEX attempts an exact search. If successful, then RULEX will continuously apply that rule until misclassification occurs. If the exact search fails to identify a rule, either an imperfect or conjunctive search will begin. A sufficient, though imperfect, rule acquired during one of these search phases will become permanently implemented and the RULEX model will then begin to search for exceptions. If no rule is acquired, then the model will attempt the search it did not perform in the previous phase. If successful, RULEX will permanently implement the rule and then begin an exception search. If none of the previous search methods are successful RULEX will default to only searching for exceptions, despite lacking an associated rule, which equates to acquiring a random rule.

Hybrid models[edit]

SUSTAIN (Supervised and Unsupervised Stratified Adaptive Incremental Network)[37] It is often the case that learned category representations vary depending on the learner’s goals,[38] as well as how categories are used during learning.[5] Thus, some categorization researchers suggest that a proper model of categorization needs to be able to account for the variability present in the learner’s goals, tasks, and strategies.[37] This proposal was realized by Love and colleagues (2004) through the creation of SUSTAIN, a flexible clustering model capable of accommodating both simple and complex categorization problems through incremental adaptation to the specifics of problems.

In practice, the SUSTAIN model first converts a stimulus’ perceptual information into features that are organized along a set of dimensions. The representational space that encompasses these dimensions is then distorted (e.g., stretched or shrunk) to reflect the importance of each feature based on inputs from an attentional mechanism. A set of clusters (specific instances grouped by similarity) associated with distinct categories then compete to respond to the stimulus, with the stimulus being subsequently assigned to the cluster whose representational space is closest to the stimulus’. The unknown stimulus dimension value (e.g., category label) is then predicted by the winning cluster, which, in turn, informs the categorization decision.

The flexibility of the SUSTAIN model is realized through its ability to employ both supervised and unsupervised learning at the cluster level. If SUSTAIN incorrectly predicts a stimulus as belonging to a particular cluster, corrective feedback (i.e., supervised learning) would signal sustain to recruit an additional cluster that represents the misclassified stimulus. Therefore, subsequent exposures to the stimulus (or a similar alternative) would be assigned to the correct cluster. SUSTAIN will also employ unsupervised learning to recruit an additional cluster if the similarity between the stimulus and the closest cluster does not exceed a threshold, as the model recognizes the weak predictive utility that would result from such a cluster assignment. SUSTAIN also exhibits flexibility in how it solves both simple and complex categorization problems. Outright, the internal representation of SUSTAIN contains only a single cluster, thus biasing the model towards simple solutions. As problems become increasingly complex (e.g., requiring solutions consisting of multiple stimulus dimensions), additional clusters are incrementally recruited so SUSTAIN can handle the rise in complexity.

[edit]

Social categorization consists of putting human beings into groups in order to identify them based on different criteria. Categorization is a process studied by scholars in cognitive science but can also be studied as a social activity. Social categorization is different from the categorization of other things because it implies that people create categories for themselves and others as human beings.[3] Groups can be created based on ethnicity, country of origin, religion, sexual identity, social privileges, economic privileges, etc. Various ways to sort people exist according to one’s schemas. People belong to various social groups because of their ethnicity, religion, or age.[39]

Social categories based on age, race, and gender are used by people when they encounter a new person. Because some of these categories refer to physical traits, they are often used automatically when people don’t know each other.[40] These categories are not objective and depend on how people see the world around them. They allow people to identify themselves with similar people, and to identify people who are different. They are useful in one’s identity formation with the people around them. One can build their own identity by identifying themselves in a group or by rejecting another group.[41]

Social categorization is similar to other types of categorization since it aims at simplifying the understanding of people. However, creating social categories implies that people will position themselves in relation to other groups. A hierarchy in group relations can appear as a result of social categorization.[41]

Scholars argue that the categorization process starts at a young age when children start to learn about the world and the people around them. Children learn how to know people according to categories based on similarities and differences. Social categories made by adults also impact their understanding of the world. They learn about social groups by hearing generalities about these groups from their parents. They can then develop prejudices about people as a result of these generalities.[40]

Another aspect of social categorization is mentioned by Stephen Reicher and Nick Hopkins and is related to political domination. They argue that political leaders use social categories to influence political debates.[39]

Negative aspects[edit]

The activity of sorting people according to subjective or objective criteria can be seen as a negative process because of its tendency to lead to violence from a group to another.[42] Indeed, similarities gather people who share common traits but differences between groups can lead to tensions and then the use of violence between those groups. The creation of social groups by people is responsible of a hierarchization of relations between groups.[42] These hierarchical relations participate in the promotion of stereotypes about people and groups, sometimes based on subjective criteria. Social categories can encourage people to associate stereotypes to groups of people. Associating stereotypes to a group, and to people who belong to this group, can lead to forms of discrimination towards people of this group.[43] The perception of a group and the stereotypes associated with it have an impact on social relations and activities.

Some social categories have more weight than others in society. For instance, in history and still today, the category of «race» is one of the first categories used to sort people. However, only a few categories of race are commonly used such as «Black», «White», «Asian» etc. It participates in the reduction of the multitude of ethnicities to a few categories based mostly on people’s skin color.[44]

The process of sorting people creates a vision of the other as ‘different’, leading to the dehumanization of people. Scholars talk about intergroup relations with the concept of social identity theory developed by H. Tajfel.[42] Indeed, in history, many examples of social categorization have led to forms of domination or violence from a dominant group to a dominated group. Periods of colonisation are examples of times when people from a group chose to dominate and control other people belonging to other groups because they considered them as inferior. Racism, discrimination and violence are consequences of social categorization and can occur because of it. When people see others as different, they tend to develop hierarchical relation with other groups.[42]

Miscategorization[edit]

There cannot be categorization without the possibility of miscategorization.[45] To do «the right thing with the right kind of thing.»,[46] there has to be both a right and a wrong thing to do. Not only does a category of which «everything» is a member lead logically to the Russell paradox («is it or is it not a member of itself?»), but without the possibility of error, there is no way to detect or define what distinguishes category members from nonmembers.

An example of the absence of nonmembers is the problem of the poverty of the stimulus in language learning by the child: children learning the language do not hear or make errors in the rules of Universal Grammar (UG). Hence they never get corrected for errors in UG. Yet children’s speech obeys the rules of UG, and speakers can immediately detect that something is wrong if a linguist generates (deliberately) an utterance that violates UG. Hence speakers can categorize what is UG-compliant and UG-noncompliant. Linguists have concluded from this that the rules of UG must be somehow encoded innately in the human brain.[47]

Ordinary categories, however, such as «dogs,» have abundant examples of nonmembers (cats, for example). So it is possible to learn, by trial and error, with error-correction, to detect and define what distinguishes dogs from non-dogs, and hence to correctly categorize them.[48] This kind of learning, called reinforcement learning in the behavioral literature and supervised learning in the computational literature, is fundamentally dependent on the possibility of error, and error-correction. Miscategorization—examples of nonmembers of the category—must always exist, not only to make the category learnable, but for the category to exist and be definable at all.

See also[edit]

- Categorical perception

- Classification (general theory)

- Library classification

- Multi-label classification

- Pattern recognition

- Statistical classification

- Symbol grounding problem

- Characterization (mathematics)

- Knolling

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Croft, William; Cruse, D. Alan (2004). «Categories, concepts, and meanings». Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–77. ISBN 0521661145.

- ^ Pothos, Emmanuel M.; Wills, Andy J., eds. (2011). «Introduction». Formal Approaches in Categorization. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521190480.

- ^ a b McGarty, Craig; Mavor, Kenneth I.; Skorich, Daniel P. (2015), «Social Categorization», International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Elsevier, pp. 186–191, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.24091-9, ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5, retrieved 2022-11-10

- ^ Murphy, Gregory L.; Medin, Douglas L. (1985). «The role of theories in conceptual coherence». Psychological Review. 92 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.92.3.289. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 4023146.

- ^ a b Markman, Arthur B.; Ross, Brian H. (2003). «Category use and category learning». Psychological Bulletin. 129 (4): 592–613. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.592. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 12848222.

- ^ a b c d e Rosch, Eleanor; Mervis, Carolyn B; Gray, Wayne D; Johnson, David M; Boyes-Braem, Penny (1976-07-01). «Basic objects in natural categories». Cognitive Psychology. 8 (3): 382–439. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(76)90013-X. ISSN 0010-0285. S2CID 5612467.

- ^ a b Markman, Arthur B.; Wisniewski, Edward J. (1997). «Similar and different: The differentiation of basic-level categories». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 23 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.23.1.54. ISSN 1939-1285.

- ^ a b Taylor, John R. (1995). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Linguistic Theory (2nd ed.). Oxford [England]: Clarendon Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 0-19-870012-1. OCLC 32546314.

- ^ Lakoff, George (1987). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46803-8. OCLC 14001013.

- ^ Conceptual Modeling: ER 2006: 25th International Conference on Conceptual Modeling, Tucson, AZ, USA, November 6-9, 2006: proceedings. David W. Embley, A. Olivé, Sudha Ram. Berlin: Springer. 2006. ISBN 978-3-540-47227-8. OCLC 262693303.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^

Pashler, Harold (2012-12-10). Encyclopedia of the Mind. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-5063-1938-4. - ^ Jackson, Frank (2000-03-09). From Metaphysics to Ethics: A Defence of Conceptual Analysis (1 ed.). Oxford University PressOxford. doi:10.1093/0198250614.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-825061-6.

- ^ Peacocke, Christopher (1995-09-25). A Study of Concepts. doi:10.7551/mitpress/6537.001.0001. ISBN 9780262281317.

- ^ Durkheim, Emile; Mauss, Marcel; Durkheim, Émile (2002). quelques formes primitives de classification. Classiques des sciences sociales. Chicoutimi: J.-M. Tremblay. doi:10.1522/cla.due.deq. ISBN 1-55441-218-8.

- ^ Alejandro, Audrey (January 2021). «How to Problematise Categories: Building the Methodological Toolbox for Linguistic Reflexivity». International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 20: 160940692110555. doi:10.1177/16094069211055572. ISSN 1609-4069. S2CID 244420443.

- ^ Katz, Jerrold J.; Fodor, Jerry A. (1963). «The Structure of a Semantic Theory». Language. 39 (2): 170–210. doi:10.2307/411200. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 411200.

- ^ Ashby, F. Gregory; Valentin, Vivian V. (2017-01-01), Cohen, Henri; Lefebvre, Claire (eds.), «Chapter 7 — Multiple Systems of Perceptual Category Learning: Theory and Cognitive Tests», Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science (Second Edition), San Diego: Elsevier, pp. 157–188, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-101107-2.00007-5, ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2, retrieved 2022-11-10

- ^ Pérez-Gay Juárez, Fernanda; Thériault, Christian; Gregory, Madeline; Rivas, Daniel; Sabri, Hisham; Harnad, Stevan (2017). «How and Why Does Category Learning Cause Categorical Perception?». International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 30. doi:10.46867/ijcp.2017.30.01.01. ISSN 0889-3675.

- ^ a b c Reed, Stephen K. (1972-07-01). «Pattern recognition and categorization». Cognitive Psychology. 3 (3): 382–407. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(72)90014-X. ISSN 0010-0285.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kruschke, John K. (2008), Sun, Ron (ed.), «Models of Categorization», The Cambridge Handbook of Computational Psychology, Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 267–301, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511816772.013, ISBN 978-0-521-85741-3

- ^ Rosch, E. (1999). Reclaiming concepts. Journal of consciousness studies, 6(11-12), 61-77.

- ^ Rosch, Eleanor; Mervis, Carolyn B (1975-10-01). «Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories». Cognitive Psychology. 7 (4): 573–605. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(75)90024-9. ISSN 0010-0285. S2CID 17258322.

- ^ a b c d Medin, Douglas L.; Schaffer, Marguerite M. (1978). «Context theory of classification learning». Psychological Review. 85 (3): 207–238. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.85.3.207. ISSN 1939-1471.

- ^ Goldstone, R. L., Kersten, A., & Carvalho, P. F. (2012). Concepts and categorization. Handbook of Psychology, Second Edition, 4.

- ^ Fisher, Douglas H. (1987). «Knowledge acquisition via incremental conceptual clustering». Machine Learning. 2 (2): 139–172. doi:10.1007/BF00114265.

- ^ Michalski, R. S. (1980). «Knowledge acquisition through conceptual clustering: A theoretical framework and an algorithm for partitioning data into conjunctive concepts». International Journal of Policy Analysis and Information Systems. 4: 219–244.

- ^ Kaufman, Kenneth A. (2012), «Conceptual Clustering», in Seel, Norbert M. (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 738–740, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1219, ISBN 978-1-4419-1427-9

- ^ a b c Ashby, F. Gregory; Maddox, W. Todd (2005-02-01). «Human Category Learning». Annual Review of Psychology. 56 (1): 149–178. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070217. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 15709932.

- ^ a b Higgins, E., & Ross, B. (2011). Comparisons in category learning: How best to compare for what. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 33, No. 33).

- ^ Ashby, F. Gregory; Maddox, W. Todd (1998-01-01), Birnbaum, Michael H. (ed.), «Chapter 4 — Stimulus Categorization», Measurement, Judgment and Decision Making, Handbook of Perception and Cognition (Second Edition), San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 251–301, doi:10.1016/b978-012099975-0.50006-3, ISBN 978-0-12-099975-0

- ^ Maddox, W. Todd; Ashby, F. Gregory (1996). «Perceptual separability, decisional separability, and the identification–speeded classification relationship». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 22 (4): 795–817. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.22.4.795. ISSN 1939-1277. PMID 8756953.

- ^ a b c Ashby, F. Gregory; Maddox, W. Todd (1993-09-01). «Relations between Prototype, Exemplar, and Decision Bound Models of Categorization». Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 37 (3): 372–400. doi:10.1006/jmps.1993.1023. ISSN 0022-2496.

- ^ a b Nosofsky, Robert M. (1986). «Attention, similarity, and the identification–categorization relationship». Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 115 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.115.1.39. ISSN 1939-2222. PMID 2937873.

- ^ Nosofsky, Robert M.; Palmeri, Thomas J.; McKinley, Stephen C. (1994). «Rule-plus-exception model of classification learning». Psychological Review. 101 (1): 53–79. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.53. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 8121960.

- ^ Simon, Herbert A.; Hunt, E. B.; Marin, J.; Stone, P. (1967). «Experiments in Induction». The American Journal of Psychology. 80 (4): 651. doi:10.2307/1421207. JSTOR 1421207.

- ^ a b Navarro, Danielle J. (2005-08-01). «Analyzing the RULEX model of category learning». Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 49 (4): 259–275. doi:10.1016/j.jmp.2005.04.001. hdl:2440/17026. ISSN 0022-2496.

- ^ a b Love, Bradley C.; Medin, Douglas L.; Gureckis, Todd M. (2004). «SUSTAIN: A Network Model of Category Learning». Psychological Review. 111 (2): 309–332. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.309. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 15065912.

- ^ Barsalou, Lawrence W. (1985). «Ideals, central tendency, and frequency of instantiation as determinants of graded structure in categories». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 11 (4): 629–654. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.11.1-4.629. ISSN 1939-1285. PMID 2932520.

- ^ a b Reicher, Stephen; Hopkins, Nick (2001). «Psychology and the End of History: A Critique and a Proposal for the Psychology of Social Categorization». Political Psychology. 22 (2): 383–407. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00246. ISSN 0162-895X. JSTOR 3791934.

- ^ a b Liberman, Zoe; Woodward, Amanda L.; Kinzler, Katherine D. (2017). «The Origins of Social Categorization». Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 21 (7): 556–568. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2017.04.004. PMC 5605918. PMID 28499741.

- ^ a b Bodenhausen, Galen V.; Kang, Sonia K.; Peery, Destiny (2012), «Social Categorization and the Perception of Social Groups», The SAGE Handbook of Social Cognition, SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 311–329, doi:10.4135/9781446247631.n16, ISBN 978-0-85702-481-7, S2CID 151765438

- ^ a b c d Tajfel, H (1982). «Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations». Annual Review of Psychology. 33 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245. ISSN 0066-4308.

- ^ Hugenberg, Kurt; Bodenhausen, Galen V. (2004). «Ambiguity in Social Categorization: The Role of Prejudice and Facial Affect in Race Categorization». Psychological Science. 15 (5): 342–345. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00680.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 15102145. S2CID 14677163.

- ^ Nadine Chaurand. Stéréotypisation. Catégorisation sociale. Dictionnaire historique et critique du racisme, PUF, 10p, 2013. ffhal-00966930

- ^ Magidor, Ofra (2019), «Category Mistakes», in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2020-01-17

- ^ Cohen & Lefebvre 2017

- ^ Lasnik, Howard; Lidz, Jeffrey L. (2016-12-22), Roberts, Ian (ed.), «The Argument from the Poverty of the Stimulus», The Oxford Handbook of Universal Grammar, Oxford University Press, pp. 220–248, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199573776.013.10, ISBN 978-0-19-957377-6

- ^ Burt, Jeremy R; Torosdagli, Neslisah; Khosravan, Naji; RaviPrakash, Harish; Mortazi, Aliasghar; Tissavirasingham, Fiona; Hussein, Sarfaraz; Bagci, Ulas (2018-09-01). «Deep learning beyond cats and dogs: recent advances in diagnosing breast cancer with deep neural networks». The British Journal of Radiology. 91 (1089): 20170545. doi:10.1259/bjr.20170545. ISSN 0007-1285. PMC 6223155. PMID 29565644.

External links[edit]

- To Cognize is to Categorize: Cognition is Categorization

- Wikipedia Categories Visualizer

- Interdisciplinary Introduction to Categorization: Interview with Dvora Yanov (political sciences), Amie Thomasson (philosophy) and Thomas Serre (artificial intelligence)

- «Category» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 508–510.

Other forms: categorizations

Categorization is the act of sorting and organizing things according to group, class, or, as you might expect, category. This noun is very similar in meaning to «assortment,» «classification,» and «compartmentalization.»

When we discuss the differences between mammals and birds, or reptiles and amphibians, we are talking about the categorization of the animal kingdom. Another form of categorization is the way libraries shelve their books by subject, genre, and reading level. Rearranging all those books by color or size would be yet another kind of categorization, but not a very useful one for people wanting to check out lots of books about birds or reptiles.

Definitions of categorization

-

noun

the basic cognitive process of arranging into classes or categories

-

synonyms:

categorisation, classification, sorting

see moresee less-

types:

- show 16 types…

- hide 16 types…

-

coordination

being of coordinate importance, rank, or degree

-

appraisal, assessment

the classification of someone or something with respect to its worth

-

ascription, attribution

assigning to a cause or source

-

ascription, attribution

assigning some quality or character to a person or thing

-

cross-classification, cross-division

classification according to more than one attribute at the same time

-

subsumption

incorporating something under a more general category

-

critical analysis, critical appraisal

an appraisal based on careful analytical evaluation

-

zoomorphism

the attribution of animal forms or qualities to a god

-

animatism

the attribution of consciousness and personality to natural phenomena such as thunderstorms and earthquakes and to objects such as plants and stones

-

imputation

the attribution to a source or cause

-

externalisation, externalization

attributing to outside causes

-

evaluation, rating, valuation

an appraisal of the value of something

-

assay, check

an appraisal of the state of affairs

-

acid test

a rigorous or crucial appraisal

-

reappraisal, reassessment, revaluation, review

a new appraisal or evaluation

-

underevaluation

an appraisal that underestimates the value of something

-

type of:

-

basic cognitive process

cognitive processes involved in obtaining and storing knowledge

-

noun

the act of distributing things into classes or categories of the same type

-

synonyms:

assortment, categorisation, classification, compartmentalisation, compartmentalization

see moresee less-

types:

- show 6 types…

- hide 6 types…

-

indexing

the act of classifying and providing an index in order to make items easier to retrieve

-

reclassification

classifying something again (usually in a new category)

-

relegation

the act of assigning (someone or something) to a particular class or category

-

stratification

the act or process or arranging persons into classes or social strata

-

taxonomy

practice of classifying plants and animals according to their presumed natural relationships

-

typology

classification according to general type

-

type of:

-

grouping

the activity of putting things together in groups

-

noun

a group of people or things arranged by class or category

-

synonyms:

categorisation, classification

see moresee less-

types:

-

dichotomy, duality

being twofold; a classification into two opposed parts or subclasses

-

trichotomy

being threefold; a classification into three parts or subclasses

-

type of:

-

arrangement

an orderly grouping (of things or persons) considered as a unit; the result of arranging

-

dichotomy, duality

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘categorization’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up categorization for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

| This page is part of the ongoing |

| Project Categorization |

| Aristotelian category |

| Categorization |

| Category |

| Category boundaries |

| Fuzziness |

| Vagueness |

| Levels of categorization |

| Basic level |

| Category-wide attribute |

| Collective function |

| Subordinate level |

| Superordinate level |

| Parasitic categorization |

| Prototype category |

| Bad member |

| Degree of membership |

| Extension |

| Flexible adaptability |

| Goodness of exemplar |

| Good member |

| Informational density |

| Inheritance |

| Radial structure |

| Structural stability |

| Taxonomy |

| Class inclusion |

| Degree of generality |

| Expert taxonomy |

| Folk taxonomy |

| Multiple parenting |

| Scientific taxonomy |

- «Making comparisons is a very human occupation. We spend our lives comparing one thing to another, and behaving according to the categorizations we make. Patterns govern our lives, be they patterns of material culture, or patterns of language. Growing up in any society involves, in large measure, discovering what categories are relevant in the particular culture in which we find ourselves. Within a few years after birth, we have established mental ‘control’ over many, if not most, of the ‘objects’ within our experience. ‘Things’ are classified as the same, similar or different, and we construct mental ‘boxes’ in which to put objects which ‘match’ in some way. However, the number of new boxes we create diminishes rapidly as we grow older. We become ‘fixed’ in our perceptions, and the world, once fresh and new, loses its ability to surprise as we become increasingly familiar with the objects it contains, and increasingly adept at placing the objects encountered today into boxes created yesterday»

- — (Dienhart 1999: 98)

Categorization is the process in which experiences and concepts are recognised and understood. Categorization implies that concepts are classified into categories based on commonalities and usually for some specific purpose. Categorization is fundamental in decision making, in all kinds of interaction with the environment, and in language. Categorization is central issue in Cognitive Linguistics in which it is argued to be one of the primary principles of conceptual and linguistic organization. However, categorization in Cognitive Linguistics differs radically from the classical Aristotelian model.

The Aristotelian category[]

The classical Aristotelian view claims that categories are discrete entities characterized by a set of property properties which are shared by all of their members. These properties are assumed to establish the conditions which are both necessary and sufficient to capture meaning.

According to the classical view, categories should be clearly defined, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. This way, any entity of the given classification universe belongs unequivocally to one, and only one, of the proposed categories.

Prototype categories[]

In the wake of the Cognitive Revolution of the 1970s, studies by cognitive scientists like Eleanor Rosch, Brent Berlin, Paul Kay, and George Lakoff, indicated that there were several problems with the classical view:

- Necessary conditions are inadequate: the idea of necessary and sufficient conditions is rarely if ever met in categories of naturally occurring things or in humans’ categorization of experiences

- There are degrees of membership: humans tend to regard some members of categories as better members than others

- Boundaries between categories are not clear cut: natural categories tend to be fuzzy at their boundaries and inconsistent in the status of their constituent members

With these observations in mind, cognitive scientists argue that categorization the process of grouping things based on prototypes. It has also been suggested that categorisation based on prototypes is the basis for human development, and that this learning relies on learning about the world via embodiment. Systems of categories are not objectively «out there» in the world but are rooted in people’s experience.

The structure of categories[]

Categories form part of a hierarchical taxonomic structure organized in accordance with at least three structural principles: radial structure, inheritance, and levels of categorization.

Radial structure[]

The notion of radial structure with introduced by Lakoff (1987), and implies that categories do not have symmetric structures. A radial structure is a taxonomy that has a center-periphery structure, such that the center of the category provides the schema of prototypical properties. The center is itself an idealization over what the membres of the category have, or should have, in common.

The more in common a member has with the prototypical center, the closer to the center it is located. That is, those members that do not share a lot of features with the center are peripherally located. Thus categories display graded centrality and degree of membership, with good members towards the center and bad members towards the boundary.

Inheritance[]

Members of categories, which are also called instances of categories, are said to inherit properties from the schema — the more they inherit, the better members, they are. However, sometimes members of a category are categories themselves, in which case they are called subsets or subcategories. Subcategories are considered extensions of the schema, because they provide a sets of properties themselves, only some of which are inherited from the schema.

Levels of categorization[]

Taxonimies of categories are organized into levels of categorization. There are three levels:

- Superordinate level: Superordinate categories are the most general ones. They are the ones that are at the top of a folk taxonomy).

- Basic, or generic, level: categories at the basic, or middle, level are perceptually and conceptually the more salient. The generic level of a category tends to elicit the most responses and richest images, providing a basic gestalt, and seems to be the psychologically basic level. Basic level categories are members of superordinate level categories.

- Subordinate level: Subordinate level categories are the most specific ones. They are the members of the basic level categories. They have clearly identifiable gestalts and many individuating specific features.

Bibliography[]

- Croft, William A. & D.A. Cruse (2004). Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dienhart, John M. (1999). «A linguistic look at riddles». Journal of Pragmatics, 31. 95-125.

- Lakoff, George (1987). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Ungerer, Friedrich & Hans-Jörg Schmid (1996). An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics. London: Longman.

| The bibliography of this article is insufficient. You can help us by adding more items. |

|---|

External links[]

- Cognition is Categorization

- Paper on the Discursive creation of categorisation

-

1

categorization

Персональный Сократ > categorization

-

2

categorization

English-Russian short dictionary > categorization

-

3

categorization

Большой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > categorization

-

4

categorization

Англо-русский словарь по компьютерной безопасности > categorization

-

5

categorization

- характеристика

характеристика

Отличительное свойство.

Примечания

1. Характеристика может быть присущей или присвоенной.

2. Характеристика может быть качественной или количественной.

3. Существуют различные классы характеристик, такие как:

— физические (например, механические, электрические, химические или биологические характеристики);

— органолептические (например, связанные с запахом, осязанием, вкусом, зрением, слухом);

— этические (например, вежливость, честность, правдивость);

— временные(например, пунктуальность, безотказность, доступность);

— эргономические(например, физиологические характеристики или связанные с безопасностью человека);

— функциональные(например, максимальная скорость самолета).

[ ГОСТ Р ИСО 9000-2008]характеристика

—

[IEV number 151-15-34]EN

characteristic

relationship between two or more variable quantities describing the performance of a device under given conditions

[IEV number 151-15-34]FR

(fonction) caractéristique, f

relation entre deux ou plusieurs variables décrivant le fonctionnement d’un dispositif dans des conditions spécifiées

[IEV number 151-15-34]Тематики

- системы менеджмента качества

- электротехника, основные понятия

EN

- ability

- attribute

- behavior

- behaviour

- categorization

- character

- characteristic

- characteristic curve

- curve

- description

- feature

- letter of reference

- parameter

- pattern

- performance

- property

- qualification

- quality

- rating

- record

- response

- signature

- state

- testimonial

DE

- Charakteristik

FR

- (fonction) caractéristique, f

Англо-русский словарь нормативно-технической терминологии > categorization

-

6

categorization

[͵kætıgəraıʹzeıʃ(ə)n]

1) деление на категории, распределение по категориям

2) присвоение категории

НБАРС > categorization

-

7

categorization

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > categorization

-

8

categorization

[ˏkætɪgɔrɪ`zeɪʃən]

категоризация

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > categorization

-

9

categorization

вчт

1) категоризация; распределение по категориям или классам; классификация

English-Russian electronics dictionary > categorization

-

10

categorization

вчт.

1) категоризация; распределение по категориям или классам; классификация

The New English-Russian Dictionary of Radio-electronics > categorization

-

11

categorization

категоризация; классификация, распределение по группам или классам

English-Russian dictionary of mechanical engineering and automation > categorization

-

12

categorization

English-Russian dictionary of computer science and programming > categorization

-

13

categorization

(n) категоризация; классификация; распределение по категориям

* * *

Новый англо-русский словарь > categorization

-

14

categorization

Англо-русский словарь по полиграфии и издательскому делу > categorization

-

15

categorization

Англо-русский словарь по психоаналитике > categorization

-

16

categorization

English-Russian dictionary on nuclear export control > categorization

-

17

categorization

категоризация; классификация

English-Russian dictionary of technical terms > categorization

-

18

categorization

English-Russian dictionary of scientific and technical difficulties vocabulary > categorization

-

19

categorization

[ˌkætəg(ə)raɪ’zeɪʃ(ə)n]

сущ.

Англо-русский современный словарь > categorization

-

20

categorization

Англо-русский синонимический словарь > categorization

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

Categorization — is the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated and understood. Categorization implies that objects are grouped into categories, usually for some specific purpose. Ideally, a category illuminates a relationship between… … Wikipedia

-

categorization — index classification, denomination, department, designation (naming), diagnosis, distribution (arrangement) … Law dictionary

-

categorization — (n.) 1866, noun of action from CATEGORIZE (Cf. categorize) … Etymology dictionary

-

categorization — (Amer.) n. classification, division into categories (also categorisation) … English contemporary dictionary

-

categorization — categorize UK US (UK also categorise) /ˈkætəgəraɪz/ verb [T] ► to put people or things into groups of people or things that have the same features: categorize sb/sth as sth »You can categorize your company s strategy as a reactor, defender,… … Financial and business terms

-

categorization — categorize (also categorise) ► VERB ▪ place in a particular category; classify. DERIVATIVES categorization noun … English terms dictionary

-

categorization of laws — index codification Burton s Legal Thesaurus. William C. Burton. 2006 … Law dictionary

-

categorization — noun see categorize … New Collegiate Dictionary

-

categorization — See categorizable. * * * … Universalium

-

categorization — noun a) a group of things arranged by category; a classification b) the process of sorting or arranging things into categories or classes See Also: category, categorize … Wiktionary

-

Categorization — Ранжирование … Краткий толковый словарь по полиграфии

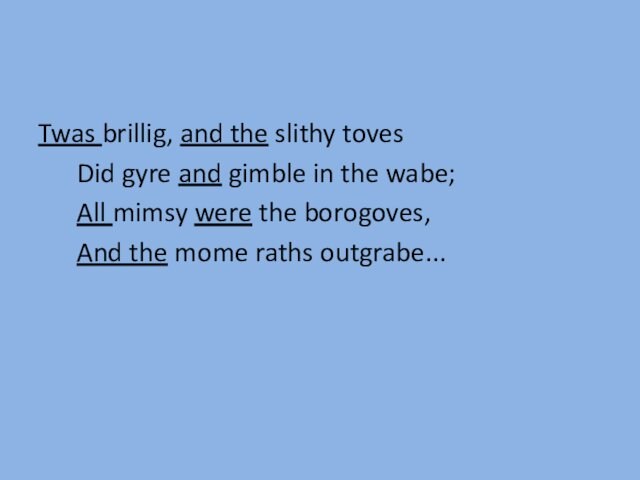

Слайд 1

Categorization

Categorization in its most general sense can be

seen as a process of systematization of acquired knowledge.

Each time we come across something new in our worlds—concrete

entities, as well as abstract concepts—we try to accommodate it by assigning it to some category or other. This phenomenon is especially common in early childhood when children progressively acquaint themselves with the world around them.

Слайд 2

However, knowledge systematization in fact occurs throughout the

lives of all human beings. Conceived in this way,

as knowledge systematization, categorization is a cognitive process which allows

human beings to make sense of the world by carving it up, in order for it to become more orderly and manageable for the mind.

Слайд 3

category

A class or division of people or things

regarded as having particular shared characteristics (Oxford Dictionary).

Слайд 4

In linguistics categorization is of paramount importance. Language

in its spoken form is no more than a

stream of sounds, and traditionally linguistics has been concerned with

the mapping of these sounds on to meaning. This process is mediated by syntax which is concerned with the segmentation of linguistic matter into units, namely categories of various sorts, and groupings of one or more of these categories into constituents. In present-day linguistics, it is safe to say, no grammatical framework can do without categories, however conceived.

Слайд 5

Categorization is no trivial matter. There is very

little consistency or uniformity in the use of the

term “category” in modern treatments of grammatical theory: different linguists

have used wider or narrower definitions of what they regard as linguistic categories.

Слайд 6