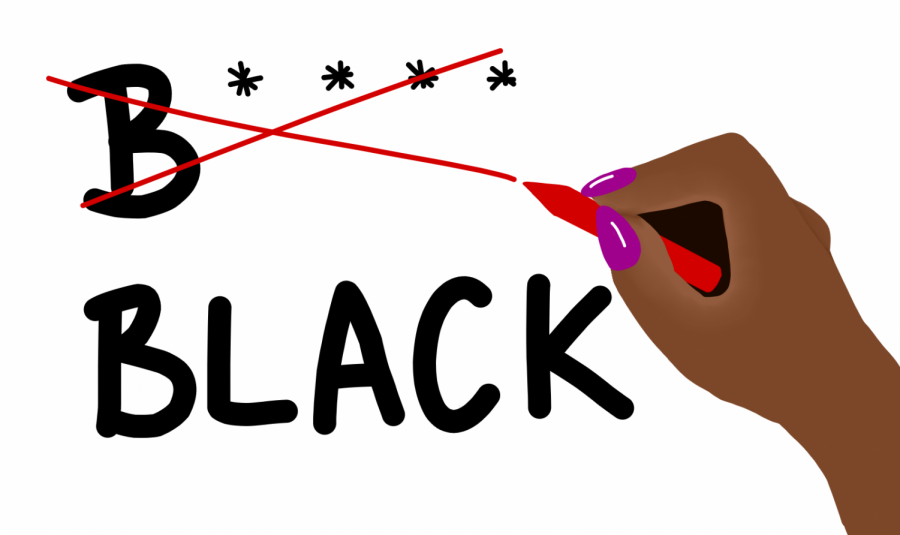

While watching the first presidential debate, I noticed that whenever discussing anything involving the black community, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump referred to black people as “African-Americans.” While their use of the term “African-American” was just an attempt at being politically correct, it made me think about the countless times I’ve heard non-black people use the word “African-American” in place of “black.”

What is curious about this is that black people aren’t always African-American. For example, I am a multiracial Latina. But just because I am black racially doesn’t mean that my ethnic group is automatically African-American. Because my family and I will be seen in the eyes of strangers as black people, we will be treated as such, therefore making my experiences of a black person similar to those in the African-American community since people see color, not ethnicity.

So because all black people — regardless of whether they’re Haitian, French or African-American — face some level of discrimination, why are people so afraid to just say “black people” when referring to black struggles? While you may be trying to use terms that don’t make black people cringe, referring to the black community as “African-Americans” leaves out the black people who don’t identify with that ethnic group.

Additionally, there are people who hold bigoted beliefs yet use terms like “African-Americans” as a way to counter any allegations of bigotry. But if someone is genuinely trying to be respectful and open-minded, I appreciate that they care enough about my feelings to use the word “African-American” because they think I’ll be offended if they just say “black people.” The amount of confusion about whether or not “black” is an OK thing to say shows the lack of honest communication between black people and everyone else concerning race relations.

Freshman Monica Ramirez believes that using the term “African-American” is “the more polite version of referring to black people.”

Ramirez, in fact, didn’t find fault with using the word “black” until people in positions of authority, such as teachers, “corrected” her and other students by suggesting that “African-American” was the more politically correct term. She feels that if someone is “saying that they’re black or African-American,” then people should use that term to describe that person. “It all depends,” she says.

It really all does depend. Many black people actually prefer the term “black” over “African-American” for a number of reasons. Some black people don’t feel a connection to either African culture, American values or both. On the other hand, though, some black people think that the term “African-American” suits them better, and that “black” is a harsh, outdated word.

A large part of me thinks that the reason why people are afraid to say “black people” is because throughout American history, blackness has been associated with negativity for a multitude of racist reasons. It’s as if nonblack people think that “black” is a mild way of saying “negro.” However, the terms with which people choose to identify themselves change throughout time.

While there are people who identify as just African-American, black or both, blackness is being celebrated by many people and it shouldn’t be a word that nonblack people are afraid to use.

But when speaking about issues that affect people who are racially black, it would be more accurate to describe them as such to avoid confusion, to be even more inclusive, and to combat the idea that “black” is a bad word.

Tatiana is a freshman in Media.

[email protected]

honest question from foreign bro

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

3e66

niger?

It is if the delete-bot things so.

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

c534

In the Roman Empire, it became the color of mourning, and over the centuries it was frequently associated with death, evil, witches and magic.

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 1 Vlad !

Economist

c534

EJMR is a Christian website and we don’t condone witchcraft on this site.

3 years ago # QUOTE 1 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

ae26

Because it is very similar to a word that white people have used to dehumanize black people for centuries.

If this was an honest question and not a weird attempt to own the libs, you would be the dumbest person on a website of dumb people.

Also: does your well-being take a hit because society won’t let you use the latin word for black? No? Then just stfu.

3 years ago # QUOTE 2 Volod 1 Vlad !

Economist

0025

The society doesn’t let me use my last name.

— Immanuel Kant

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

7c33

The society doesn’t let me use my last name.

— Immanuel Kant

You mean that you kant use it?

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

7c33

Because it is very similar to a word that white people have used to dehumanize black people for centuries.

If this was an honest question and not a weird attempt to own the libs, you would be the dumbest person on a website of dumb people.

Also: does your well-being take a hit because society won’t let you use the latin word for black? No? Then just stfu.

The words are related but they are easily distinguishable.

In fact, the Latin word for blck was the polite, respectable word for blck for a very, very long time. It was considered polite by everyone while its derivative was long rejected by polite, decent people. See the works of Mark Twain, for example.

No, the real reason that it is a bad word is that arbitrarily declaring words to be bad and forbidding decent people from using them is an exercise in power and virchew signulling. The Lfft changes the language to both signal its power and to create categories of people who are beyond respectability.

No one’s well being is better or worse for not using this word but nearly everyone’s well being is worse for living in a society in which tin pot cullchural revlutionaries flex their muscle to constantly redefine standards of behavior.

3 years ago # QUOTE 2 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

495f

Pipolum Colorus?

3 years ago # QUOTE 1 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

ae26

Because it is very similar to a word that white people have used to dehumanize black people for centuries.

If this was an honest question and not a weird attempt to own the libs, you would be the dumbest person on a website of dumb people.

Also: does your well-being take a hit because society won’t let you use the latin word for black? No? Then just stfu.The words are related but they are easily distinguishable.

In fact, the Latin word for blck was the polite, respectable word for blck for a very, very long time. It was considered polite by everyone while its derivative was long rejected by polite, decent people. See the works of Mark Twain, for example.

No, the real reason that it is a bad word is that arbitrarily declaring words to be bad and forbidding decent people from using them is an exercise in power and virchew signulling. The Lfft changes the language to both signal its power and to create categories of people who are beyond respectability.

No one’s well being is better or worse for not using this word but nearly everyone’s well being is worse for living in a society in which tin pot cullchural revlutionaries flex their muscle to constantly redefine standards of behavior.

wtf is wrong with you. Are you that stupid that you think it was just «arbitrary» that the n-word is offensive?

Also, don’t abstract this to society redefining standards of behaviors. Also, It seems pretty clearly obvious that no one is worse off from not using that word and that people clearly are worse off from using the word. The pareto efficient move is to stop using that word.

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

47a3

OP bonum

3 years ago # QUOTE 0 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

7c33

Because it is very similar to a word that white people have used to dehumanize black people for centuries.

If this was an honest question and not a weird attempt to own the libs, you would be the dumbest person on a website of dumb people.

Also: does your well-being take a hit because society won’t let you use the latin word for black? No? Then just stfu.The words are related but they are easily distinguishable.

In fact, the Latin word for blck was the polite, respectable word for blck for a very, very long time. It was considered polite by everyone while its derivative was long rejected by polite, decent people. See the works of Mark Twain, for example.

No, the real reason that it is a bad word is that arbitrarily declaring words to be bad and forbidding decent people from using them is an exercise in power and virchew signulling. The Lfft changes the language to both signal its power and to create categories of people who are beyond respectability.

No one’s well being is better or worse for not using this word but nearly everyone’s well being is worse for living in a society in which tin pot cullchural revlutionaries flex their muscle to constantly redefine standards of behavior.wtf is wrong with you. Are you that stupid that you think it was just «arbitrary» that the n-word is offensive?

Also, don’t abstract this to society redefining standards of behaviors. Also, It seems pretty clearly obvious that no one is worse off from not using that word and that people clearly are worse off from using the word. The pareto efficient move is to stop using that word.

He wasn’t talking about the n-word, moron. He was talking about the word it was derived from. Entirely different.

Are you really so stupid that you are incapable of understanding my clear argument or are you simply dishonest?

It is always hard for me to tell.

This has always been a question of the power to arbitrarily redefine standards so you can virchew signull. That is the only reason you people do it.

You just pretend that it is about manners. But no one was offended by the Latin word for black until early essjaydubyas found it useful to pretend that it was offensive.

Now you pretend using «he/she» is offensive. Next year it will be something else.

3 years ago # QUOTE 1 Volod 0 Vlad !

Economist

f568

In this very polarized day and age where we are under threat of extremism on both sides, we need to come together for peace and dialogue. As Pepsi said eloquently in a commercial, let’s start a conversation.

3 years ago # QUOTE 1 Volod 0 Vlad !

February 2, 2021

Black History Month is starting and I would like to bring attention to that fact, but more attention to the fact that Black is okay — the word, the color and the people. People do not need to feel uncomfortable referring to Black people as Black. It is often preferred to refer to Black people as Black because POC is not inclusive to Black issues and was created to undermine the Black experience.

To begin, let me announce that I am Black. Blackitty Black. I have to hold my ears down when getting my hair combed — Black. I have no issues with being called dark or African-American, but I prefer Black, and there is nothing wrong with that. Growing up, people made me feel like I had to be ashamed for being Black and having darker skin, but there is nothing to be ashamed of. I just produce a great amount of melanin, and I am grateful for that. Black has a bad rep, and I am here to clear its name.

Black has been used with weak symbolic representation that contributes to its association with badness. When we think of people being morally corrupt, we say that their soul is blackened. In shows or movies, they often depict the evil characters dressed in black or dark colors. We could use Disney as a case study — Maleficent, Ursula, Cruella de Vil, even Scar are all dressed in black or have black features. We are socialized to think that black is bad, sorrowful even — this is why at funerals everyone dresses in black. Studies have shown that it’s gotten to the point that people ascribe darker skin to a higher likeliness of committing violence. This phenomenon is called the “bad is black” effect. Not only is it problematic, but it is harmful towards Black people because it characterizes a feature they cannot control as a social opposition, aggression.

We need to begin to challenge this association between color and emotion, especially for black. I believe Alain Badiou does a great job of challenging our beliefs in his book “Black: The Brilliance of a Non-Color.” In the book, Badiou makes a point that contradicts our perceived notion of black being corrupt.

“Scientists confirm it: black is not a color … There’s no light, there’s no color … Black is passive negation … [while white is] the combined, confused sum of all possible colors. Black is the absence of color, while white is the impure mixture of all the colors,” Badiou writes.

This perspective challenges everything we know. The way in which Badiou pursues color suggests that black is pure, while white is confused and impure. Now imagine being socialized to think this way. Whiteness would be associated with impurity and confusion. Would you value any scholar who was white if you were conditioned to believe that they were confused? You may give them a chance after decades of corrections, but there will always be a subconscious bias that exists and would affect being hired at a job or getting into university. Perhaps this perspective awakens you to the daily experience of Black people.

It is important to examine the origin of discomfort for Black people. With identity politics in mind, people try not to use any language that may get them “cancelled.” Thus, they avoid trigger words that are sensitive to backlash. Instead of saying Black, they will say African American. Although African American may sound academically and politically correct and appraised, it can be incorrect. There are Black people who are not American. Also, the generalized use of “African” has to do with slave “culture” and the inability to trace the lineage of enslaved persons. There are people who know where they are from and have strong roots in their culture. Not only is it simply inaccurate to refer to them as African American, but it excludes the Black Experience. Being Black doesn’t rely on the origin of Black you are, but the collective affairs that Black people endure.

Now with Black Lives Matter trending, the confusion between using Black and African American is excluding members from this necessary conversation. Since Black Lives Matter is based in the United States, some felt as if it was an American issue and started saying African American Lives Matter. However, this was leaving out the voices of people experiencing police brutality outside of America. To use African American is to be nation-specific and, in the case of BLM, it doesn’t recognize the problem outside of America. This is why we emphasize Black. Black is inclusive to all people of African descent.

Many people think of Black as a bad or dirty word. It is this discomfort that brought about the phrase “People of Color,” or POC. “People of Color” is meant to be endearing and emphasize the existence of non-white people across the board. The problem is that there are Black issues which are exclusive to Black people. There are also some POC who condone Anti-Black racism. “People of Color” does not work when referring to Black people. People need to get over themselves. Their discomfort is muffling Black issues.

All in all, I want people to be more comfortable with using Black. I want people to know Black. I want people to love Black. As I stated before, it is not bad or something to be ashamed of, Black is okay. Black is beautiful.

If you would like to learn more about his topic, you can find an informative Twitter thread here.

Ajani Powell writes about social influences and Black culture. Contact them at [email protected].

I’m a St. Louis mom, a New York entrepreneur, and mom to three children (ages 4, 3, and 1). I spend much of my time trying to raise these children to be big-hearted, just, and courageous. Until recently those attempts embraced diversity but skirted the issue of race directly. The unrest and conflict in my newly adopted city over this last year forced me to see just how tongue-tied I have become about race (a conversation that used to feel fluid), especially in my new community, and especially with my children. I’ve been sharing my thoughts at Parenting While White.

I was an adult before I felt comfortable saying (in a regular tone of voice) the word Black to describe a person. That means I whispered it for nearly two decades. And it’s not surprising. Why would I feel comfortable saying a word that was either regarded as taboo or so often associated with bad and undesirable circumstances? It felt like an insult.

I was theoretically raised to be colorblind.

“It doesn’t matter if you are Black, White, or green,” I was told. “We are all the same. What matters is who you are on the inside.”

But despite the sentimental statements, reality was plain as day for anyone with eyes. To me, Black people were different and rare in my environments. White people were the norm. Black people were more often poor and (reportedly) involved with crime. They made up the majority of the homeless people I saw in Philadelphia, and the majority of the people on the city buses that I did not ride.

It was commonplace for me to hear, “Lock ‘em up” (meaning the doors) when driving through a predominantly Black area of the city. What I saw and heard didn’t match was I was told.

Beyond this discrepancy however, potential conversation was further eroded by a conflicting concern for and distain of political correctness. No one wanted to be called out as a racist. Yet no one knew the “right” thing to say. So we all stayed conveniently tongue-tied and resorted to speaking in code saying things like “inner-city” and “urban” and “ghetto.” They all meant Black, but seemed somehow less offensive.

Now that I have children, I’ve given a lot of thought to the messages I want to impart about race and social justice. I’m convinced that language is an important part of the equation. How can you ever feel really positive and connected to something that you don’t have direct, comfortable, confident language to describe?

This point seems really straightforward in other contexts. When it comes to body parts, for example. We are a medical family. I’ve read the research that says that children who use proper terminology for their bodies parts develop a positive body image, confidence, and are at less risk of abuse or victimization. So, we don’t say “pee-pee,” we say vagina. We don’t say “weiner,” we say penis. While it’s not the most comfortable experience if my children inappropriately (or appropriately) use these terms in public, I don’t get panicky about it. Someone might be embarrassed (likely me) but someone probably won’t be personally offended.

I’ve known for a while that I’ve wanted my children to be empowered with appropriate, respectful, and direct language to talk about race. But that hasn’t made it easy or comfortable. I’ve felt many moments of hesitation.

I’ll ask myself, “Do I really want to get into all that now?” as an opportunity slips through my fingers. Like most White parents, I’ve had many concerns about the potential negative impacts of introducing the topic of race. I’ve also read the research stating the opposite.

I find myself repeating my “talking about race” mantra to myself often:

“I need to talk about race early, often, and directly.”

This self-talk give me courage and direction, especially since I live in a community of people who also aren’t talking about race. I can’t count on friends and playmates to intervene with the type of common, communal mama language we’ve almost all adopted…“use your words, not your hands.”

Race is a barrier not often breeched. And despite my own trepidation at times, I’m clear that the onus is mostly on me, which leads to a lot of second-guessing and internal pep talks.

Luckily for me and my family, my children go to a diverse school, especially by suburban St. Louis standards. Talking about different shades of skin tone is a regular occurrence at school and different shades of skin tone are easily observed. There are two teachers with the same name who teach at her school. My daughter comfortably differentiates between

“…the Sra. Ana with the curlier hair and darker skin and the Sra. Ana with the straight hair and the lighter skin.”

No big deal. Seeing how fluid her conversations were about appearance and ethnicity has made it easier to begin scratching at the surface of the realities of race in America. Allowing me to take baby steps alongside of her, with her sometimes even leading the way.

Together, we’ve worked our way past skin tones to labels.

“Usually people call people who look like us ‘White,’ even though our skin isn’t actually White. Usually people call other people with very dark skin ‘Black,’ even though their skin isn’t actually Black.”

We talk about hues, and shades, and the infinite continuum of appearance. And that foundation has so far proven to be very helpful. As we’ve begun talking about the realities of discrimination and racism, it has really helped to have common, simple, and confident shared language. I’m not conditioning or coding what I say. It seems to be at face value. It feels good to have the opportunity to not pass down my negative baggage about the word ‘Black.’ It feels good to, instead, have the opportunity to literally help redefine Black for my White children.

This weekend my children and I are making a Black Lives Matters lemonade stand of sorts in an effort to get more homes in our 90% White St. Louis suburb to display a Black Lives Matters sign. I am, of course, motivated by the mission of the Black Lives Matters Yard Sign Project, but I’m also seeing this as a restorative opportunity for me, and my White children to reclaim the word Black as something positive, valuable, and worth fighting for. From the start.

__

Adelaide Lancaster is founder of In Good Company, a community and workspace for women entrepreneurs in Manhattan and the author of The Big Enough Company. She holds a M.Ed. in Psychological Counseling and M.A. in Organizational Psychology both from Teachers College at Columbia University, and a B.A in Educational Studies and Sociology and Anthropology from Colgate University.

Click here for more information on participating in a Raising Race Conscious Children interactive workshop/webinar or small group workshop series.

Login to BlackFacts.com using your favorite Social Media Login. Click the appropriate button below and you will be redirected to your Social Media Website for confirmation and then back to Blackfacts.com once successful.

Enter the email address and password you used to join BlackFacts.com. If you cannot remember your login information, click the “Forgot Password” link to reset your password.

Forgot Password?

Forgot Your Blackfacts Password?

Enter the email address and password you used to join BlackFacts.com. If you cannot remember your login information, click the “Forgot Password” link to reset your password.

Wakanda News Details

You may also like