«Dream analysis» redirects here. For the book by Carl Jung, see Dream Analysis.

Tom Paine’s Nightly Pest, a James Gillray cartoon of political activist Thomas Paine dreaming of faceless judges unfurling scrolls listing charges and punishments

Dream interpretation is the process of assigning meaning to dreams. Although associated with some forms of psychotherapy, there is no reliable evidence that understanding or interpreting dreams has a positive impact on one’s mental health.[1][2][3]

In many ancient societies, such as those of Egypt and Greece, dreaming was considered a supernatural communication or a means of divine intervention, whose message could be interpreted by people with these associated spiritual powers. In modern times, various schools of psychology and neurobiology have offered theories about the meaning and purpose of dreams. Most people currently appear to interpret dream content according to Freudian psychoanalysis in the United States, India, and South Korea, according to one study conducted in those countries.[4]

People appear to believe dreams are particularly meaningful: they assign more meaning to dreams than to similar waking thoughts. For example, people report they would be more likely to cancel a trip they had planned that involved a plane flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing the night before than if the Department of Homeland Security issued a federal warning.[4]

However, people do not attribute equal importance to all dreams. People appear to use motivated reasoning when interpreting their dreams. They are more likely to view dreams confirming their waking beliefs and desires to be more meaningful than dreams that contradict their waking beliefs and desires.[4]

History[edit]

Early civilizations[edit]

The ancient Sumerians in Mesopotamia have left evidence of dream interpretation dating back to at least 3100 BC in Mesopotamia.[6][5] Throughout Mesopotamian history, dreams were always held to be extremely important for divination[5][7] and Mesopotamian kings paid close attention to them.[5][6] Gudea, the king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash (reigned c. 2144–2124 BC), rebuilt the temple of Ningirsu as the result of a dream in which he was told to do so.[5] The standard Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh contains numerous accounts of the prophetic power of dreams.[5][8][9] First, Gilgamesh himself has two dreams foretelling the arrival of Enkidu.[5] In one of these dreams, Gilgamesh sees an axe fall from the sky. The people gather around it in admiration and worship. Gilgamesh throws the axe in front of his mother Ninsun and then embraces it like a wife. Ninsun interprets the dream to mean that someone powerful will soon appear. Gilgamesh will struggle with him and try to overpower him, but he will not succeed. Eventually, they will become close friends and accomplish great things. She concludes, «That you embraced him like a wife means he will never forsake you. Thus your dream is solved.»[10] Later in the epic, Enkidu dreams about the heroes’ encounter with the giant Humbaba.[5] Dreams were also sometimes seen as a means of seeing into other worlds[5] and it was thought that the soul, or some part of it, moved out of the body of the sleeping person and actually visited the places and persons the dreamer saw in his or her sleep.[11] In Tablet VII of the epic, Enkidu recounts to Gilgamesh a dream in which he saw the gods Anu, Enlil, and Shamash condemn him to death.[5] He also has a dream in which he visits the Underworld.[5]

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC) built a temple to Mamu, possibly the god of dreams, at Imgur-Enlil, near Kalhu.[5] The later Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–c. 627 BC) had a dream during a desperate military situation in which his divine patron, the goddess Ishtar, appeared to him and promised that she would lead him to victory.[5] The Babylonians and Assyrians divided dreams into «good,» which were sent by the gods, and «bad,» sent by demons.[7] A surviving collection of dream omens entitled Iškar Zaqīqu records various dream scenarios as well as prognostications of what will happen to the person who experiences each dream, apparently based on previous cases.[5][12] Some list different possible outcomes, based on occasions in which people experienced similar dreams with different results.[5] Dream scenarios mentioned include a variety of daily work events, journeys to different locations, family matters, sex acts, and encounters with human individuals, animals, and deities.[5]

Joseph Interprets Pharaoh’s Dream (watercolor circa 1896–1902 by James Tissot)

In ancient Egypt, priests acted as dream interpreters. Hieroglyphics depicting dreams and their interpretations are evident. Dreams have been held in considerable importance through history by most cultures.

Classical Antiquity[edit]

The ancient Greeks constructed temples they called Asclepieions, where sick people were sent to be cured. It was believed that cures would be effected through divine grace by incubating dreams within the confines of the temple. Dreams were also considered prophetic or omens of particular significance. Artemidorus of Daldis, who lived in the 2nd century AD, wrote a comprehensive text Oneirocritica (The Interpretation of Dreams).[13] Although Artemidorus believed that dreams can predict the future, he presaged many contemporary approaches to dreams. He thought that the meaning of a dream image could involve puns and could be understood by decoding the image into its component words. For example, Alexander, while waging war against the Tyrians, dreamt that a satyr was dancing on his shield. Artemidorus reports that this dream was interpreted as follows: satyr = sa tyros («Tyre will be thine»), predicting that Alexander would be triumphant. Freud acknowledged this example of Artemidorus when he proposed that dreams be interpreted like a rebus.[14]

Middle Ages[edit]

In medieval Islamic psychology, certain hadiths indicate that dreams consist of three parts, and early Muslim scholars recognized three kinds of dreams: false, pathogenic, and true.[15] Ibn Sirin (654–728) was renowned for his Ta’bir al-Ru’ya and Muntakhab al-Kalam fi Tabir al-Ahlam, a book on dreams. The work is divided into 25 sections on dream interpretation, from the etiquette of interpreting dreams to the interpretation of reciting certain Surahs of the Qur’an in one’s dream. He writes that it is important for a layperson to seek assistance from an alim (Muslim scholar) who could guide in the interpretation of dreams with a proper understanding of the cultural context and other such causes and interpretations.[16] Al-Kindi (Alkindus) (801–873) also wrote a treatise on dream interpretation: On Sleep and Dreams.[17] In consciousness studies, Al-Farabi (872–951) wrote the On the Cause of Dreams, which appeared as chapter 24 of his Book of Opinions of the people of the Ideal City. It was a treatise on dreams, in which he was the first to distinguish between dream interpretation and the nature and causes of dreams.[18] In The Canon of Medicine, Avicenna extended the theory of temperaments to encompass «emotional aspects, mental capacity, moral attitudes, self-awareness, movements and dreams.»[19] Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah (1377) states that «confused dreams» are «pictures of the imagination that are stored inside by perception and to which the ability to think is applied, after (man) has retired from sense perception.»[20]

Ibn Shaheen states: «Interpretations change their foundations according to the different conditions of the seer (of the vision), so seeing handcuffs during sleep is disliked but if a righteous person sees them it can mean stopping the hands from evil». Ibn Sirin said about a man who saw himself giving a sermon from the mimbar: «He will achieve authority and if he is not from the people who have any kind of authority it means that he will be crucified».

China[edit]

A standard traditional Chinese book on dream-interpretation is the Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation (夢占逸旨) compiled in the 16th century by Chen Shiyuan (particularly the «Inner Chapters» of that opus).[21][22][23][24] Chinese thinkers also raised profound ideas about dream interpretation, such as the question of how we know we are dreaming and how we know we are awake. It is written in the Chuang-tzu: «Once Chuang Chou dreamed that he was a butterfly. He fluttered about happily, quite pleased with the state that he was in, and knew nothing about Chuang Chou. Presently he awoke and found that he was very much Chuang Chou again. Now, did Chou dream that he was a butterfly or was the butterfly now dreaming that he was Chou?» This raises the question[according to whom?] of reality monitoring in dreams, a topic of intense interest in modern cognitive neuroscience.[25][26]

Modern Europe[edit]

In the 17th century, the English physician and writer Sir Thomas Browne wrote a short tract upon the interpretation of dreams. Dream interpretation was taken up as part of psychoanalysis at the end of the 19th century; the perceived, manifest content of a dream is analyzed to reveal its latent meaning to the psyche of the dreamer. One of the seminal works on the subject is The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud.

The present[edit]

A paper[4] in 2009 by Carey Morewedge and Michael Norton in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that most people believe that «their dreams reveal meaningful hidden truths.» In one study conducted in the United States, South Korea and India, they found that 74% of Indians, 65% of South Koreans and 56% of Americans believed their dream content provided them with meaningful insight into their unconscious beliefs and desires. This Freudian view of dreaming was endorsed significantly more than theories of dreaming that attribute dream content to memory consolidation, problem solving, or random brain activity. This belief appears to lead people to attribute more importance to dream content than to similar thought content that occurs while they are awake. In one study in the paper, Americans were more likely to report that they would miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing than if they thought of their plane crashing the night before flying (while awake), and that they would be as likely to miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing the night before their flight as if there was an actual plane crash on the route they intended to take.[11] Not all dream content was considered equally important. Participants in their studies were more likely to perceive dreams to be meaningful when the content of dreams was in accordance with their beliefs and desires while awake. People were more likely to view a positive dream about a friend to be meaningful than a positive dream about someone they disliked, for example, and were more likely to view a negative dream about a person they disliked as meaningful than a negative dream about a person they liked.

Psychology[edit]

Freud[edit]

It was in his book The Interpretation of Dreams[14] (Die Traumdeutung; literally «dream-interpretation»), first published in 1899 (but dated 1900), that Sigmund Freud first argued that the motivation of all dream content is wish-fulfillment (later in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud would discuss dreams which do not appear to be wish-fulfillment), and that the instigation of a dream is often to be found in the events of the day preceding the dream, which he called the «day residue.» In the case of very young children, Freud claimed, this can be easily seen, as small children dream quite straightforwardly of the fulfillment of wishes that were aroused in them the previous day (the «dream day»). In adults, however, the situation is more complicated—since in Freud’s submission, the dreams of adults have been subjected to distortion, with the dream’s so-called «manifest content»[27] being a heavily disguised derivative of the «latent dream-thoughts»[28] present in the unconscious.[29] As a result of this distortion and disguise, the dream’s real significance is concealed: dreamers are no more capable of recognizing the actual meaning of their dreams than hysterics are able to understand the connection and significance of their neurotic symptoms.

In Freud’s original formulation, the latent dream-thought was described as having been subject to an intra-psychic force referred to as «the censor»; in the more refined terminology of his later years, however, discussion was in terms of the super-ego and «the work of the ego’s forces of defense.» In waking life, he asserted, these so-called «resistances» altogether prevented the repressed wishes of the unconscious from entering consciousness; and though these wishes were to some extent able to emerge during the lowered state of sleep, the resistances were still strong enough to produce «a veil of disguise» sufficient to hide their true nature. Freud’s view was that dreams are compromises which ensure that sleep is not interrupted: as «a disguised fulfilment of repressed wishes,» they succeed in representing wishes as fulfilled which might otherwise disturb and waken the dreamer.[30]

Freud’s «classic» early dream analysis is that of «Irma’s injection»: in that dream, a former patient of Freud’s complains of pains. The dream portrays Freud’s colleague giving Irma an unsterile injection. Freud provides us with pages of associations to the elements in his dream, using it to demonstrate his technique of decoding the latent dream thought from the manifest content of the dream.

Freud described the actual technique of psychoanalytic dream-analysis in the following terms, suggesting that the true meaning of a dream must be «weeded out» from dream:[31]

You entirely disregard the apparent connections between the elements in the manifest dream and collect the ideas that occur to you in connection with each separate element of the dream by free association according to the psychoanalytic rule of procedure. From this material you arrive at the latent dream-thoughts, just as you arrived at the patient’s hidden complexes from his associations to his symptoms and memories… The true meaning of the dream, which has now replaced the manifest content, is always clearly intelligible. [Freud, Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (1909); Lecture Three]

Freud listed the distorting operations that he claimed were applied to repressed wishes in forming the dream as recollected: it is because of these distortions (the so-called «dream-work») that the manifest content of the dream differs so greatly from the latent dream thought reached through analysis—and it is by reversing these distortions that the latent content is approached.

The operations included:[32]

- Condensation – one dream object stands for several associations and ideas; thus «dreams are brief, meagre and laconic in comparison with the range and wealth of the dream-thoughts.»

- Displacement – a dream object’s emotional significance is separated from its real object or content and attached to an entirely different one that does not raise the censor’s suspicions.

- Visualization – a thought is translated to visual images.

- Symbolism – a symbol replaces an action, person, or idea.

To these might be added «secondary elaboration»—the outcome of the dreamer’s natural tendency to make some sort of «sense» or «story» out of the various elements of the manifest content as recollected. (Freud, in fact, was wont to stress that it was not merely futile but actually misleading to attempt to «explain» one part of the manifest content with reference to another part as if the manifest dream somehow constituted some unified or coherent conception).

Freud considered that the experience of anxiety dreams and nightmares was the result of failures in the dream-work: rather than contradicting the «wish-fulfillment» theory, such phenomena demonstrated how the ego reacted to the awareness of repressed wishes that were too powerful and insufficiently disguised. Traumatic dreams (where the dream merely repeats the traumatic experience) were eventually admitted as exceptions to the theory.

Freud famously described psychoanalytic dream-interpretation as «the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind»; he was, however, capable of expressing regret and dissatisfaction at the way his ideas on the subject were misrepresented or simply not understood:[33]

The assertion that all dreams require a sexual interpretation, against which critics rage so incessantly, occurs nowhere in my Interpretation of Dreams … and is in obvious contradiction to other views expressed in it.

— Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

On another occasion, he suggested that the individual capable of recognizing the distinction between latent and manifest content «will probably have gone further in understanding dreams than most readers of my Interpretation of Dreams«.

Jung[edit]

Although not dismissing Freud’s model of dream interpretation wholesale, Carl Jung believed Freud’s notion of dreams as representations of unfulfilled wishes to be limited. Jung argued that Freud’s procedure of collecting associations to a dream would bring insights into the dreamer’s mental complex—a person’s associations to anything will reveal the mental complexes, as Jung had shown experimentally[34]—but not necessarily closer to the meaning of the dream.[35] Jung was convinced that the scope of dream interpretation was larger, reflecting the richness and complexity of the entire unconscious, both personal and collective. Jung believed the psyche to be a self-regulating organism in which conscious attitudes were likely to be compensated for unconsciously (within the dream) by their opposites.[36] And so the role of dreams is to lead a person to wholeness through what Jung calls «a dialogue between ego and the self». The self aspires to tell the ego what it does not know, but it should. This dialogue involves fresh memories, existing obstacles, and future solutions.[37]

Jung proposed two basic approaches to analyzing dream material: the objective and the subjective.[38] In the objective approach, every person in the dream refers to the person they are: mother is mother, girlfriend is girlfriend, etc.[39] In the subjective approach, every person in the dream represents an aspect of the dreamer. Jung argued that the subjective approach is much more difficult for the dreamer to accept, but that in most good dream-work, the dreamer will come to recognize that the dream characters can represent an unacknowledged aspect of the dreamer. Thus, if the dreamer is being chased by a crazed killer, the dreamer may come eventually to recognize his own homicidal impulses.[39] Gestalt therapists extended the subjective approach, claiming that even the inanimate objects in a dream can represent aspects of the dreamer.

Jung believed that archetypes such as the animus, the anima, the shadow and others manifested themselves in dreams, as dream symbols or figures. Such figures could take the form of an old man, a young maiden or a giant spider as the case may be. Each represents an unconscious attitude that is largely hidden to the conscious mind. Although an integral part of the dreamer’s psyche, these manifestations were largely autonomous and were perceived by the dreamer to be external personages. Acquaintance with the archetypes as manifested by these symbols serve to increase one’s awareness of unconscious attitudes, integrating seemingly disparate parts of the psyche and contributing to the process of holistic self-understanding he considered paramount.[36]

Jung believed that material repressed by the conscious mind, postulated by Freud to comprise the unconscious, was similar to his own concept of the shadow, which in itself is only a small part of the unconscious.

Jung cautioned against blindly ascribing meaning to dream symbols without a clear understanding of the client’s personal situation. He described two approaches to dream symbols: the causal approach and the final approach.[40] In the causal approach, the symbol is reduced to certain fundamental tendencies. Thus, a sword may symbolize a penis, as may a snake. In the final approach, the dream interpreter asks, «Why this symbol and not another?» Thus, a sword representing a penis is hard, sharp, inanimate, and destructive. A snake representing a penis is alive, dangerous, perhaps poisonous and slimy. The final approach will tell additional things about the dreamer’s attitudes.

Technically, Jung recommended stripping the dream of its details and presenting the gist of the dream to the dreamer. This was an adaptation of a procedure described by Wilhelm Stekel, who recommended thinking of the dream as a newspaper article and writing a headline for it.[41] Harry Stack Sullivan also described a similar process of «dream distillation.»[42]

Although Jung acknowledged the universality of archetypal symbols, he contrasted this with the concept of a sign—images having a one-to-one connotation with their meaning. His approach was to recognize the dynamism and fluidity that existed between symbols and their ascribed meaning. Symbols must be explored for their personal significance to the patient, instead of having the dream conform to some predetermined idea. This prevents dream analysis from devolving into a theoretical and dogmatic exercise that is far removed from the patient’s own psychological state. In the service of this idea, he stressed the importance of «sticking to the image»—exploring in depth a client’s association with a particular image. This may be contrasted with Freud’s free associating which he believed was a deviation from the salience of the image. He describes for example the image «deal table.» One would expect the dreamer to have some associations with this image, and the professed lack of any perceived significance or familiarity whatsoever should make one suspicious. Jung would ask a patient to imagine the image as vividly as possible and to explain it to him as if he had no idea as to what a «deal table» was. Jung stressed the importance of context in dream analysis.

Jung stressed that the dream was not merely a devious puzzle invented by the unconscious to be deciphered, so that the true causal factors behind it may be elicited. Dreams were not to serve as lie detectors, with which to reveal the insincerity behind conscious thought processes. Dreams, like the unconscious, had their own language. As representations of the unconscious, dream images have their own primacy and mechanics.

Jung believed that dreams may contain ineluctable truths, philosophical pronouncements, illusions, wild fantasies, memories, plans, irrational experiences and even telepathic visions.[43] Just as the psyche has a diurnal side which we experience as conscious life, it has an unconscious nocturnal side which we apprehend as dreamlike fantasy. Jung would argue that just as we do not doubt the importance of our conscious experience, then we ought not to second guess the value of our unconscious lives.

Hall[edit]

In 1953, Calvin S. Hall developed a theory of dreams in which dreaming is considered to be a cognitive process.[44] Hall argued that a dream was simply a thought or sequence of thoughts that occurred during sleep, and that dream images are visual representations of personal conceptions. For example, if one dreams of being attacked by friends, this may be a manifestation of fear of friendship; a more complicated example, which requires a cultural metaphor, is that a cat within a dream symbolizes a need to use one’s intuition. For English speakers, it may suggest that the dreamer must recognize that there is «more than one way to skin a cat,» or in other words, more than one way to do something. He was also critical of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of dream interpretation, particularly Freud’s notion that the dream of being attacked represented a fear of castration. Hall argued that this dream did not necessarily stem from castration anxiety, but rather represented the dreamer’s perception of themselves as weak, passive, and helpless in the face of danger.[45] In support of his argument, Hall pointed out that women have this dream more frequently than men, yet women do not typically experience castration anxiety. Additionally, he noted that there were no significant differences in the form or content of the dream of being attacked between men and women, suggesting that the dream likely has the same meaning for both genders. Hall’s work in dream research also provided evidence to support one of Sigmund Freud’s theories, the Oedipus Complex. Hall studied the dreams of males and females ages two through twenty-six. He found that young boys frequently dreamed of aggression towards their fathers and older male siblings, while girls dreamed of hostility towards their mothers and older female siblings.[46] These dreams often involved themes of conflict and competition for the affection of the opposite-sex parent, providing empirical support for Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex.

Faraday, Clift, et al.[edit]

In the 1970s, Ann Faraday and others helped bring dream interpretation into the mainstream by publishing books on do-it-yourself dream interpretation and forming groups to share and analyze dreams. Faraday focused on the application of dreams to situations occurring in one’s life. For instance, some dreams are warnings of something about to happen—e.g. a dream of failing an examination, if one is a student, may be a literal warning of unpreparedness. Outside of such context, it could relate to failing some other kind of test. Or it could even have a «punny» nature, e.g. that one has failed to examine some aspect of his life adequately.

Faraday noted that «one finding has emerged pretty firmly from modern research, namely that the majority of dreams seem in some way to reflect things that have preoccupied our minds during the previous day or two.»[47]

In the 1980s and 1990s, Wallace Clift and Jean Dalby Clift further explored the relationship between images produced in dreams and the dreamer’s waking life. Their books identified patterns in dreaming, and ways of analyzing dreams to explore life changes, with particular emphasis on moving toward healing and wholeness.[48]

See also[edit]

- Dream dictionary

- Dream journal

- Dream sharing

- Lucid dreaming

- Oneiromancy

- Oneironautics

- Personality test

- Psychoanalytic dream interpretation

- Recurring dream

References[edit]

- ^ Lack, Caleb (April 2020). «Depression: Is Psychoanalytic dream interpretation useful?». Skeptical Inquirer. 44 (2): 51.

- ^ Domhoff, G. William. «Moving dream theory beyond Freud and Jung». Dreamresearch.net. University of California Santa Cruz: dreamresearch.net. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Domhoff, G. William (2000). «The misinterpretation of dreams». American Scientist. 88 (2): 175–178.

- ^ a b c d Morewedge, Carey K.; Norton, Michael I. (2009). «When dreaming is believing: The (motivated) interpretation of dreams». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 96 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1037/a0013264. PMID 19159131.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 71–72, 89–90. ISBN 0714117056.

- ^ a b Seligman, K. (1948), Magic, Supernaturalism and Religion. New York: Random House

- ^ a b Oppenheim, L.A. (1966). Mantic Dreams in the Ancient Near East in G. E. Von Grunebaum & R. Caillois (Eds.), The Dream and Human Societies (pp. 341–350). London, England: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Thompson, R. (1930) The Epic of Gilgamesh. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ George, A. trans. (2003) The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Oppenheim, A. (1956) The interpretation of dreams in the ancient Near East with a translation of an Assyrian dreambook. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 46(3): 179–373. p. 247.

- ^ a b Caillois, R. (1966). Logical and Philosophical Problems of the Dream. In G.E. Von Grunebaum & R. Caillos (Eds.), The Dream and Human Societies(pp. 23–52). London, England: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Nils P. Heessel : Divinatorische Texte I : … oneiromantische Omina. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2007.

- ^ Artemidorus (1990) The Interpretation of Dreams: Oneirocritica. White, R., trans., Torrance, CA: Original Books, 2nd Edition.

- ^ a b Freud, S. (1900) The Interpretation of Dreams. New York: Avon, 1980.

- ^ (Haque 2004, p. 376)

- ^ (Haque 2004, p. 375)

- ^ (Haque 2004, p. 361)

- ^ (Haque 2004, p. 363)

- ^ Lutz, Peter L. (2002), The Rise of Experimental Biology: An Illustrated History, Humana Press, p. 60, ISBN 0-89603-835-1

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N.J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah, trans., p. 338, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01754-9

- ^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, «Inner Chapters 1–4»

- ^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, «Inner Chapter 5»

- ^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, «Inner Chapters 6–9»

- ^ Lofty Principles of Dream Interpretation, «Inner Chapter 10»

- ^ Johnson, M.; Kahan, T.; Raye, C. (1984). «Dreams and reality monitoring». Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 113 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.329. PMID 6237167.

- ^ Blechner, M (2005). «Elusive illusions: Reality judgment and reality assignment in dreams and waking life». Neuro-Psychoanalysis. 7: 95–101. doi:10.1080/15294145.2005.10773477. S2CID 145533839.

- ^ Nagera, Humberto, ed. (2014) [1969]. «Manifest content (pp. 52ff.)». Basic Psychoanalytic Concepts on the Theory of Dreams. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31767047-6.

- ^ Nagera, Humberto, ed. (2014) [1969]. «Latent dream-content (pp. 31ff.)». Basic Psychoanalytic Concepts on the Theory of Dreams. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31767048-3.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (2010). The interpretation of dreams. Strachey, James. New York: Basic Books A Member of the Perseus Books Group. ISBN 9780465019779. OCLC 434126117.

- ^ Matalon, Nadav (2011). «The Riddle Of Dreams». Philosophical Psychology. 24 (4): 517–536. doi:10.1080/09515089.2011.556605. S2CID 144246389.

- ^ Wilson, Cynthia (3 April 2012). «Remembering and Understanding your Dreams». Womenio. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Gray, R. (9 January 2012). «Lecture Notes: Freud’s Conception of the Psyche (Unconscious) and His Theory of Dreams». University of Washington. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Freud, S. (1900) op.cit., (1919 edition), p. 397

- ^ Jung, C.G. (1902) The associations of normal subjects. In: Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–99.

- ^ Jacobi, J. (1973) The Psychology of C. G. Jung. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ a b Storr, Anthony (1983). The Essential Jung. New York. ISBN 0-691-02455-3.

- ^ Lone, Zauraiz (2018-09-26). «Jung’s Dream Theory and Modern Neuroscience: From Fallacies to Facts». World of Psychology. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- ^ Jung, C.G. (1948) General aspects of dream psychology. In: Dreams. trans., R. Hull. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974, pp. 23–66.

- ^ a b Doyle, D. John (2018). What does it mean to be human? Life, Death, Personhood and the Transhumanist Movement. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 173. ISBN 9783319949505. OCLC 1050448349.

- ^ Jung, C.G. (1948) op.cit.

- ^ Stekel, W. (1911) Die Sprache des Traumes (The Language of the Dream). Wiesbaden: J.F. Berman

- ^ Sullivan, H.S. (1953) The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton.

- ^ Jung, Carl (1934). The Practice of Psychotherapy. The Practical Use of Dream-analysis. p. 147. ISBN 0-7100-1645-X.

- ^ Calvin S. Hall. «A Cognitive Theory of Dreams». dreamresearch.net. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Hall, Calvin S. (1955). «The Significance of the Dream of Being Attacked». Journal of Personality. 24 (2): 168–180. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1955.tb01182.x. ISSN 0022-3506.

- ^ Hall, Calvin (1963). «Strangers in dreams: an empirical confirmation of the Oedipus complex1». Journal of Personality. 31 (3): 336–345. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1963.tb01303.x.

- ^ Faraday, Ann. The Dream Game. p. 3.

- ^ Clift, Jean Dalby; Clift, Wallace (1984). Symbols of Transformation in Dreams. The Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8245-0653-7.; Clift, Jean Dalby; Clift, Wallace (1988). The Hero Journey in Dreams. The Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8245-0889-0.; Clift, Jean Dalby (1992). Core Images of the Self: A Symbolic Approach to Healing and Wholeness. The Crossroad Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8245-1218-9.

Works cited[edit]

- Haque, Amber (December 2004). «Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists». Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z. S2CID 38740431.

Further reading[edit]

- Aziz, Robert (1990). C.G. Jung’s Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity (10 ed.). The State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0166-9.

- Aziz, Robert (1999). «Synchronicity and the Transformation of the Ethical in Jungian Psychology». In Becker, Carl (ed.). Asian and Jungian Views of Ethics. Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30452-1.

- Aziz, Robert (2007). The Syndetic Paradigm: The Untrodden Path Beyond Freud and Jung. The State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6982-8.

- Aziz, Robert (2008). «Foreword». In Storm, Lance (ed.). Synchronicity: Multiple Perspectives on Meaningful Coincidence. Pari Publishing. ISBN 978-88-95604-02-2.

- Doniger O’Flaherty, Wendy (1986). Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-61855-2.

- Freud, Sigmund (1966). Introductory Lectures. W.W. Norton. p. 334.

- Freud, Sigmund (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. Macmillan.

- Freud, Sigmund (1920). A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Boni & Liveright.

- Hall, James (1983). Jungian Dream Interpretation: A Handbook of Theory and Practice. Inner City Books. ISBN 0-919123-12-0.

- Sechrist, Elsie with foreword by Cayce, Hugh Lynn (1974). Dreams, Your Magic Mirror. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-31384-X.

External links[edit]

- Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis for Beginners – Full text of Sigmund Freud’s revisitation of The Interpretation of Dreams

- A contemporary Jungian view of dream interpretation

Recent Examples on the Web

Set in Sri Lanka during the civil war, the novel follows Sashi, a young Tamil woman who has dreams of becoming a doctor.

—

And thank you to those who helped make our dream of having a family into this wonderful reality.

—

Decades later, people have nightmare dreams of walking into tests without having studied.

—

There are also dreams of taking Shucked into corners that Broadway musicals have never ventured before.

—

Now, after his release, Dan has big dreams of proving his innocence while fostering his relationships with his family.

—

While every mid-major who makes an NCAA tournament run dreams of being the next Gonzaga, the reality is that San Diego State is a much more attainable and aspirational model.

—

Enter Email Sign Up With his shaggy hair, hepcat beard and racy poems touching on British youth’s anxieties, dreams of freedom and lust, he was hailed as Britain’s answer to Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, which raised eyebrows among some guardians of traditional British values.

—

Tupperware was created to help families save money after World War II, Trader Joe’s was conceived to cater to an emerging middle class that would soon travel internationally, and Nike was built on one man’s dream of creating the ultimate running shoe.

—

Beba is awaiting her papers and managing expectations, hoping for resident status but not daring to dream of citizenship.

—

Authors who dreamed of being published in Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories—the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction, which published from 1926 through 1980—knew that Gernsback himself was a pioneering radio and television broadcaster.

—

For the first time in over a century, our campus will be re-opened to admit individuals a minimum of 16 Earth years (or species equivalent) who dream of exceeding their physical, mental and spiritual limits, who value friendship, camaraderie, honor and devotion to a cause greater than themselves.

—

Thankfully, snoozing in a sleeping bag or pitching a flimsy tent aren’t the only ways to dream surrounded by nature.

—

France likes to dream of revolution, ever re-enacting the popular uprising of 1789 that led to the guillotining of the king and queen and the abolition of the monarchy three years later.

—

Being Mary Tyler Moore explores Mary’s vanguard career, who, as an actor, performer, and advocate, revolutionized the portrayal of women in media, redefined their roles in show business, and inspired generations to dream big and make it on their own.

—

Practice your craft, and then be open to really dreaming big.

—

Although many high schoolers will dream about attending college ahead of National Decision Day in May, college enrollment has plummeted in recent years, dropping 8% between 2019 to 2022, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘dream.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes: The Dream

A dream is the experience of a sequence of images, sounds, ideas, emotions, or other sensations during sleep, especially REM sleep. The events of dreams are often impossible, or unlikely to occur, in physical reality: they are also outside the control of the dreamer. The exception to this is known as lucid dreaming, in which dreamers realize that they are dreaming, and are sometimes capable of changing their dream environment and controlling various aspects of the dream. Dreams have long been one of the most puzzling aspects of consciousness that humankind possesses. Both religion and science have tried to define what dreams are, where they come from, and what they mean.

People all over the world throughout history have experienced and reported dreams. Some have been, or believed to have been, prophetic, messages from the spiritual world or heaven giving warnings or announcements of fortune that is to come. For some, dreams are seen as manifestations of our unconscious desires, thoughts, secrets that we repress in our waking lives but which surface as we sleep. For others, a more straightforward and benign explanation is that the brain processes the experiences of the day into long-term memory during sleep, sometimes activating a stream of data into consciousness, forming a dream.

Whatever the cause, and there may be different types of dreams that result from different processes, it is the responsibility of the dreamer to act appropriately with regard to the dream experience. Setting too much store by dreams as opposed to the «reality» of the physical world has its dangers; equally, though, information received in dreams may be legitimate, whether from one’s own mind or from another realm. Achieving maturity as a human being, united in mind and body, may prove necessary to be able to discern the true meaning of dreams.

Dream content

Antonio de Pereda: The Knight’s Dream (1640)

A dream is the experience of a sequence of images, sounds, ideas, emotions, or other sensations during sleep. The events of dreams are often impossible, or unlikely to occur, in physical reality—people known by the person to be dead may appear, people and events occur in locations where they are not normally found, the dreamer may experience activities that are physically impossible such as flying, people known to speak another language may be comprehensible to the dreamer, and so forth. People all over the world throughout history have experienced and reported dreams. The content of these dreams, although the details vary as widely as the lives of the dreamers, nonetheless has a certain universality.

Calvin S. Hall and Van De Castle published The Content Analysis of Dreams in which they outlined a coding system to study 1,000 dream reports from college students.[1] From the 1940s to 1985, Hall collected more than 50,000 dream reports at Western Reserve University. Hall’s complete dream reports became publicly available in the mid-1990s by Hall’s protégé William Domhoff allowing further content analysis. It was found that people all over the world dream of mostly the same things.

Common themes

A number of common themes have been identified in dreams. These include: themes relating to school, being chased, sexual experiences, falling, arriving too late, a person now alive being dead, flying, and failing an examination. In addition, it has been found that 12 percent of people dream only in black and white.

[2]

Emotions

The most common emotion experienced in dreams was anxiety. Negative emotions are more common than positive feelings.[1] Ethnic groups showed different percentages of dreams of an aggressive nature. The U.S. ranks the highest amongst industrialized nations for aggression in dreams, with 50 percent of U.S. males reporting aggression compared to 32 percent for Dutch men.[1]

Gender differences

In men’s dreams 70 percent of the characters are other men, while women’s dreams contain an equal number of men and women.[1] Men generally had more aggressive feelings in their dreams than women, and children’s dreams did not have very much aggression until they reached the teenage years. These findings parallel much of the current research on gender and gender role comparisons in aggressive behavior. Rather than showing a complementary or compensatory aggressive style between our thoughts and dreams, these data support the view that there is a continuity between our conscious and unconscious styles and personalities.

Sexual content

Sexual content is not as prevalent in dreams as one might expect. The Hall data analysis shows that sexual dreams show up no more than 10 percent of the time and are more prevalent in young to mid teens.[1]

The Soldier’s Dream of Home

Recurring dreams

While the content of most dreams is generally experienced in only a single dream, most people experience recurring dreams—that is, the same dream narrative is experienced over different occasions of sleep. Up to 70 percent of females and 65 percent of males report recurrent dreams.[1]

Cultural and religious perspectives

Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337): Legend of Saint Joachim, Joachim’s Dream

Long before science and psychology, religion and cultural beliefs were developed to explain the dream phenomena. Dreams were thought to be part of a spiritual world, and were seen as messages from the gods. The Abrahamic faiths—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—believe that there were two sources of dreams: God and Satan.

Dreams are prolific in the Bible, Torah, and Qur’ān. Sometimes, these dreams are messages from God, such as of Saint Joseph, the husband of Mary, when the Angel Gabriel spoke to him in a dream and told him that the baby Mary was carrying was the Son of God. After the visit of the Three Wise Men to them in Bethlehem, an angel appeared to him and told him to take Mary and Jesus to Egypt for their safety. The angel appeared again in a dream to tell him when it was safe to return to Israel. Other times people given more obscure messages that required interpretation. Both Jacob and Daniel were all given the ability to interpret dreams by God. Likewise Joseph was given the power to interpret dreams and act accordingly, which he did for the Pharaoh of Egypt.

Jacob’s dream of a ladder of angels

Joseph Smith (1805 — 1844), founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, claimed to have received a visitation from a resurrected prophet named Moroni that led to his finding and unearthing (in 1827) a long-buried book, inscribed on metal leaves, which contained a record of God’s dealings with the ancient Israelite inhabitants of the Americas.

In such cases, the distinction between a dream and a vision of spiritual beings while awake is blurred. Indeed, people reporting such visitations from beings apparently from the spiritual realm are often unsure as to whether they were awake or dreaming.

Ancient Buddhism taught that dreams were the mental projections of a person’s desires and fears, an illusory construct developed out of each person’s attachment to the illusory world of waking consciousness. Tibetan Buddhism took the idea one step further, and taught that the dream state was actually one of the bardos, or transition states of conscious that was akin to the spiritual state a person goes through when they die; hence, developing consciousness within this the bardo-dream state would help prepare someone for the ultimate transition in death.[3] In India, scholars such as Charaka (300 B.C.E.) had a similar take on dreams, believing that they were the product of the senses and natural make-up of a person.

Shamanism in various cultures saw dreams and dream-like states as connections to worlds and realms of the spirit. Although there were hundreds of different shamanistic traditions, generally, dreams were considered by most to be alternate states of consciousness where people could visit different spiritual realms, engage in spiritual and physical healing, commune with deities and spirits as well as obtain special knowledge and abilities.[4]

Psycho-dynamic interpretation of dreams

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were the first to identify dreams as an interaction between the unconscious and the conscious. They both asserted that the unconscious is the dominant force of the dream, and in dreams it conveys its own mental activity to the perceptive faculty.

Freud

Sigmund Freud arrived at his theory of dreams by research (though he rejected much of the prior work), self-analysis, and psychoanalysis of his patients. As his theory developed, Freud often used dream interpretation to treat his patients, calling dreams «the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.»

In his book The Interpretation of Dreams, first published at the end of the nineteenth century, Freud argued that the foundation of all dream content is the fulfillment of wishes, conscious or not. The theory explains that the schism between superego and id leads to «censorship» of dreams. The unconscious would «like» to depict the wish fulfilled wholesale, but the preconscious cannot allow it — the wish (or wishes) within a dream is thus disguised, and, as Freud argued, only an understanding of the structure of the dream-work can explain the dream. Freud listed four transformations applied to wishes in order to avoid censorship:

- Condensation — one dream object stands for several thoughts.

- Displacement — a dream object’s psychical importance is assigned to an object that does not raise the censor’s suspicions.

- Representation — a thought is translated to visual images.

- Symbolism — a symbol replaces an action, person, or idea.

These transformations help to disguise the latent content, transforming it into the manifest content, what is actually seen by the dreamer. The basis for all of these systems, he claimed, was «transference,» in which a would-be censored wish of the unconscious is given undeserved «psychical energy» (the quantum of attention from consciousness) by attaching to «innocent» thoughts.

Freud further claimed that the counterintuitive nature of nightmares represented a clash between the super-ego and the id: the id wishes to see a past wish fulfilled, while the super-ego cannot allow it. He interpreted the anxiety of a nightmare as the super-ego working against the id. (He further claimed that in nearly all cases these anxious dreams are products of infantile, sexual memories.)

Jung

Dream analysis is central to Jungian analytical psychology, and forms a critical part of the therapeutic process in classical Jungian analysis. Although not dismissing Freud’s model of dream interpretation wholesale, Carl Jung believed that Freud’s notion of dreams as representations of unfulfilled wishes to be simplistic and naive. Jung was convinced that the scope of dream interpretation was larger, reflecting the richness and complexity of the entire unconscious, both personal and collective. Jung believed the psyche to be a self-regulating organism in which conscious attitudes were likely to be compensated for unconsciously (within the dream) by their opposites.[5]

Jung believed that archetypes such as the animus, the anima, the shadow, and others manifested themselves in dreams, as dream symbols or figures. Such figures could take the form of an old man, a young maiden, or a giant spider as the case may be. Each represents an unconscious attitude that is largely hidden to the conscious mind. Jung believed that material repressed by the conscious mind, postulated by Freud to comprise the unconscious, was similar to his own concept of the shadow, which in itself is only a small part of the unconscious.

Although an integral part of the dreamers psyche, these manifestations were largely autonomous and were perceived by the dreamer to be external personages. Acquaintance with the archetypes as manifested by these symbols serves to increase one’s awareness of unconscious attitudes, integrating seemingly disparate parts of the psyche and contributing to the process of holistic self understanding he considered paramount.[5]

Jung cautioned against blindly ascribing meaning to dream symbols without a clear understanding of the client’s personal situation. Although he acknowledged the universality of archetypal symbols, he contrasted this with the concept of a sign—images having a one to one connotation with their meaning. His approach was to recognise the dynamism and fluidity that existed between symbols and their ascribed meaning. Symbols must be explored for their personal significance to the patient, instead of having the dream conform to some predetermined idea. Jung stressed the importance of context in dream analysis. In service of this idea, he stressed the importance of «sticking to the image»—exploring in depth a client’s association with a particular image. This may be contrasted with Freud’s free associating, which Jung believed to be a deviation from the salience of the image.

Contemporary dream interpretation

In contemporary psychoanalysis, the role of dream interpretation has been diminished by focusing on other aspects of psychoanalytic views.[6] Nevertheless, dreams, and their interpretation, continue to provide a powerful therapeutic focus. Many studies have underlined the importance of dreams in psychoanalysis, and therapeutic work in general.[7] Further, a growing body of literature supports the continuity hypothesis of dreams from sleep to waking reality. The continuity hypothesis suggest that the content of dreams is not remote from the waking reality, but, rather, portrays the most prominent feelings, interests, and concerns of the individual.[8]

Science of dreams

During a typical lifespan, a person spends about two hours each night dreaming, a total of about six years dreaming.[9][10] Yet, there is no universally agreed-upon biological definition of dreaming. It is unknown where in the brain dreams originate—if there is such a single location—or why dreams occur at all.

REM sleep

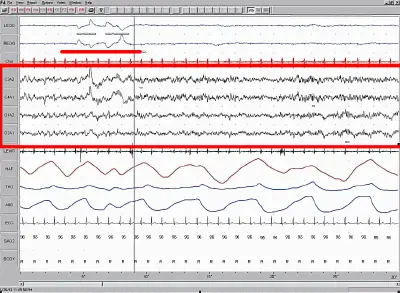

EEG showing brainwaves during REM sleep

General observation shows that dreams are strongly associated with Rapid Eye Movement or REM sleep. REM sleep is the state of sleep in which brain activity is most like wakefulness, which is why many researchers believe this is when dreams are strongest, although it could also mean that this is a state from which dreams are most easily remembered.[11]

In 1953 Eugene Aserinsky discovered REM sleep while working in Nathaniel Kleitmans sleep laboratory. Aserinsky noticed the eyes beneath the subjects’ eyelids seemed to be fluttering during periods of their sleep. Kleitman suggested that Aserinsky use a polygraph machine to record changes in the brain during times when the eye movements occurred. During these sessions, Aserinsky began to notice patterns in the brain waves of the volunteers. During one session he awakened a subject who was crying out in his sleep during REM and confirmed an earlier hunch that dreaming was occurring.[12] In 1953 Kleitman and Aserinsky published the ground-breaking study in Science.[13]

In 1976, J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarly proposed the activation synthesis theory of dreams. This theory asserts that the sensory experiences are fabricated by the cortex as a means of interpreting chaotic signals from the pons. They propose that in REM sleep, the ascending cholinergic PGO (ponto-geniculo-occipital) waves stimulate higher midbrain and forebrain cortical structures, producing rapid eye movements. The activated forebrain then synthesizes the dream out of this internally generated information.[14] They assumed that the same structures that induce REM sleep also generate sensory information.

Role of forebrain

Hobson’s 1976 research suggested that the signals interpreted as dreams originated in the brain stem during REM sleep. However, research by Mark Solms suggested that dreams are generated in the forebrain, and that REM sleep and dreaming are not directly related.[15] While working in the neurosurgery department at hospitals in Johannesburg and London, Solms had access to patients with various brain injuries. He began to question patients about their dreams and confirmed that patients with damage to the parietal lobe stopped dreaming; this finding was in line with Hobson’s theory. However, Solms did not encounter cases of loss of dreaming with patients having brain stem damage, which went against Hobson’s notion of the brain stem as the source of the signals interpreted as dreams. Solms viewed the idea of dreaming as a function of many complex brain structures as validating Freudian dream theory, an idea that drew criticism from Hobson.[16]

Continual-activation theory

Combining Hobson’s activation synthesis hypothesis with Solms’s findings, Jie Zhang proposed the continual-activation theory of dreaming, that dreaming is a result of brain activation and synthesis while, at the same time, dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms. Zhang hypothesized that the function of sleep is to process, encode, and transfer the data from the temporary memory to the long-term memory. In this model, NREM sleep processes the conscious-related memory (declarative memory), and REM sleep processes the unconscious related memory (procedural memory).

Zhang assumed that during REM sleep, the unconscious part of a brain is busy processing the procedural memory; meanwhile, the level of activation in the conscious part of the brain will descend to a very low level as the inputs from the sensory are basically disconnected. This will trigger the «continual-activation» mechanism to generate a data stream from the memory stores to flow through the conscious part of the brain. Zhang suggested that this pulse-like brain activation is the inducer of each dream. He proposed that, with the involvement of the brain associative thinking system, dreaming is, thereafter, self-maintained with the dreamer’s own thinking until the next pulse of memory insertion. This explains why dreams have both characteristics of continuity (within a dream) and sudden changes (between two dreams).[17][18]

A 2001 study showed evidence that illogical locations, characters, and dream flow may help the brain strengthen the linking and consolidation of semantic memories. These conditions may occur because, during REM sleep, the flow of information between the hippocampus and neocortex is reduced.[19] Increasing levels of the stress hormone cortisol late in sleep (often during REM sleep) cause this decreased communication. One stage of memory consolidation is the linking of distant but related memories. Payne and Nadal hypothesized that these memories are then consolidated into a smooth narrative, the dream, similar to a process that happens when memories are created under stress.[20]

Other associated phenomena

Lucid dreaming

Lucid dreaming is the conscious perception of one’s state while dreaming. The occurrence of lucid dreaming has been scientifically verified. Many people, including scientists and psychologists have started to acknowledge the benefits of lucid dreaming. If developed as a skill, a person who is able to achieve lucid dreaming can often explore the complexities of their sub-conscious, helping to deal with past trauma, fears, anxieties, and can promote mental health.[11]

Recalling dreams

Many people have difficulty recalling their dreams. Researchers refer to these types of dreams as «no content dream reports.»[21] It appears that such dreams are characterized by relatively little affect. Factors such as salience, arousal, and interference play a role in dream recall and dream recall failure.[21]

Keeping a dream journal appears to be a useful technique to improve dream recall. It is quite common to not remember much of a dream on first waking, but by lying still, not letting concerns of the day occupy the mind, with sufficient concentration the entire dream may be recalled.[11]

Dreams of absent-minded transgression

Dreams of absent-minded transgression (DAMT) are dreams wherein the dreamer absentmindedly performs an action that he or she has been trying to stop (one classic example is of a former smoker having dreams of lighting a cigarette). Subjects who have had DAMT have reported awaking with intense feelings of guilt. Some studies have shown that DAMT are positively related with successfully stopping the behavior, when compared to control subjects who did not experience these dreams.[22]

Dreaming as a skeptical argument

While dreaming a non-lucid dream, the dreamer does not realize that they are dreaming. The classic example is a child dreaming that they are using the toilet who wets the bed because they do not realize that they are in a dream. This lack of awareness has led philosophers to the idea that one could be dreaming right now (or at least one cannot be certain that one is not dreaming). First formally introduced by Zhuangzi and popularized by Hindu beliefs, the dream argument has become one of the most popular hypotheses in support of skepticism. It was formally introduced to western philosophy by Descartes in the seventeenth century in his Meditations on First Philosophy.

Déjà vu

The theory of déjà vu dealing with dreams indicates that the feeling of having previously seen or experienced something could be attributed to having dreamed about a similar situation or place, and forgetting about it until one seems to be mysteriously reminded of the situation or place while awake.

Dream incorporation

In one use of the term, «dream incorporation» is a phenomenon whereby an external stimulus, usually an auditory one, becomes a part of a dream, eventually then awakening the dreamer. There is a famous painting by Salvador Dalí that depicts this concept, entitled Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944).

The term «dream incorporation» is also used in research examining the degree to which preceding daytime events become elements of dreams. Studies suggest that events in the day immediately preceding, and those about a week before, have the most influence.[23]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Adam Schneider, Content Analysis Explained Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Michael Schredl, Petra Ciric, Simon Götz, and Lutz Wittmann, «Typical Dreams: Stability and Gender Differences» The Journal of Psychology 138(6) (November, 2004): 485.

- ↑ Lama Surya Das, Awakening the Buddha Within (Broadway Books, 1997, ISBN 0767901576).

- ↑ Roger Walsh, World of Shamanism: New Views of an Ancient Tradition (Llewellyn Publications, 2007, ISBN 0738705756).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Anthony Storr, The Essential Jung (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0691029351).

- ↑ S. Ringel, «Dreaming and Listening: A final journey» Clinical Social Work Journal 30(4) (2002).

- ↑ N. Pesant and A. Zadra, «Working with dreams in therapy: What do we know and what should we do?» Clinical Psychology Review 24 (2004): 489-512.

- ↑ M. Schredl, C. Landgraf, and O. Zeiler, «Nightmare frequency, nightmare distress and neuroticism» North American Journal of Psychology 5 (2003): 345–350.

- ↑ Lee Ann Obringer, How Dreams Work How Stuff Works. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Stephen LaBerge, Lucid Dreaming (Sounds True, 2004, ISBN 1591791502).

- ↑ William Dement, The Sleepwatchers (Nychthemeron Press, 1996, ISBN 0964933802).

- ↑ Eugene Aserinsky and Nathaniel Kleitman, Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, During Sleep Science 118(3062) (September 1953): 273-274. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Evie Bentley, Awareness: Biorhythms, Sleep and Dreaming (Routledge, 1999, ISBN 0415188733).

- ↑ M. Solms, «Dreaming and REM Sleep are Controlled by Different Brain Mechanisms» Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23(6) (2000):793-1121.

- ↑ Andrea Rock, The Mind at Night: The New Science of How and Why we Dream (Basic Books, 2004, ISBN 0465070698).

- ↑ Jie Zhang (2004) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242392091_Memory_Process_and_the_Function_of_Sleep Memory Process and the Function of Sleep Journal of Theoretics Volume 6-6 (December 2004). Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Jie Zhang, Continual-activation Theory of Dreaming Dynamical Psychology (2005). Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ R. Stickgold, J. A. Hobson, R. Fosse, and M. Fosse1, 9https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11691983/ Sleep, Learning, and Dreams: Off-line Memory Reprocessing] Science 294(5544)(November 2001):1052-1057. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Jessica D. Payne and Lynn Nadel, Sleep, Dreams, and Memory Consolidation: The Role of the Stress Hormone Cortisol0 Learning and Memory 11 (2004): 671-678. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 David Koulack, To Catch A Dream (SUNY Press, 1991, ISBN 0791405028).

- ↑ P. Hajek and M. Belcher, Dream of absent-minded transgression: an empirical study of a cognitive withdrawal symptom Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100(4) (1991):487-491. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑

Jean-Baptiste Eichenlaub, Elaine van Rijn, Mairéad Phelan, Larnia Ryder, M. Gareth Gaskell, Penelope A. Lewis, Matthew P. Walker, and Mark Blagrove, The nature of delayed dream incorporation (‘dream-lag effect’): Personally significant events persist, but not major daily activities or concerns Journal of Sleep Research 28(1) (2019). Retrieved June 21, 2021.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Artemidorus. The Oneirocritica of Artemidorus. New Haven: University Microfilms, 1971.

- Bentley, Evie. Awareness: Biorhythms, Sleep and Dreaming. New York: Routledge, 1999. ISBN 0415188733

- Castaneda, Carlos. The Art of Dreaming. Thorsons, 2004. ISBN 978-1855384279

- Das, Lama Surya. Awakening the Buddha Within. Broadway Books, 1997. ISBN 0767901576

- Dement, William. The Sleepwatchers. Nychthemeron Press, 1996. ISBN 0964933802

- Dieterle, Bernard, and Manfred Engel (eds.) The Dream and the Enlightenment / Le Rêve et les Lumières. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2003. ISBN 2745306723

- Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. NuVision Publications, 2007 (original 1899). ISBN 978-1595479365

- Freud, Sigmund. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. New York, NY: Boni & Liveright.

- Gackenbach, Jayne, and Stephen LaBerge. Conscious Mind, Sleeping Brain: Perspectives on Lucid Dreaming. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation, 1988.

- Garfield, Patricia L. Creative Dreaming. 1974 (original 1920). ISBN 0671219030

- Hall, James A. Jungian Dream Interpretation: A Handbook of Theory and Practice. Inner City Books, 1983. ISBN 0919123120

- Hill, Clara E. Working with Dreams in Psychotherapy. 1996. ISBN 1572300922

- Jung, Carl. Dreams. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0691017921

- Koulack, David. To Catch A Dream: Explorations of Dreaming. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1991. ISBN 0791405028

- LaBerge, Stephen. Lucid Dreaming. Sounds True, 2004. ISBN 1591791502

- Lippman, P. Nocturnes: on listening to dreams. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press, Inc., 2000.

- Norbu, Namkhai Chogyal. Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-1559391610

- Phillips, Will. Every Dreamer’s Handbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Understanding and Benefiting From Your Dreams. Totonada Press, 1994. ISBN 1575660482

- Rock, Andrea. The Mind at Night: The New Science of How and Why we Dream. New York: Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0465070698

- Storr, Anthony. The Essential Jung. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1999 ISBN 978-0691159003

- Van de Castle, Robert L. Our Dreaming Mind New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1994. ISBN 0345396669

- Walsh, Roger. World of Shamanism: New Views of an Ancient Tradition. Llewellyn Publications, 2007. ISBN 0738705756

- Wangyal, Tenzin Rinpoche. The Tibetan Yogas of Dream and Sleep. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1998. ISBN 978-1559391016

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2021.

- The International Association for the Study of Dreams

- Content Analysis Explained The complete Calvin S. Hall / Robert Van de Castle coding system.

- The Case Against the Problem-Solving Theory of Dreaming.

- Dream Moods

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Dream history

- Dream_interpretation history

- Contemporary_dream_interpretation history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Dream»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Dreams are a vast world we go to while sleeping that can be friendly, scary, or just plain bizarre. Maybe you are a person who doesn’t remember your dreams, or maybe you have vivid dreams every night. Dreams can be pleasant: you can be transported to a party or go on an exciting journey. Nightmares are possible too: you can dream of being chased by a criminal or being back in high school and taking a final without having studied. Sometimes, dreams can bring bittersweet sadness, like when a loved one who has passed visits in a dream, bringing both comfort and longing. Different cultures around the world uniquely interpret their dreams. Psychologists study the meaning of dreams as well, which we will explore further in this article.

Want To Understand What Your Dreams Mean To You?

A Dream: What Is It?

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that occur for the most part involuntarily during certain stages of sleep. There are other definitions of the word “dream,” too. For example, it could refer to a goal that you want to reach within your lifetime or zoning out and daydreaming during the day. In this article, we will focus on the dreams that occur while you are sleeping.

Dreams are not necessarily based on waking reality. As anyone who has dreamed knows, in a dream you can walk through landscapes you have never visited, spend time with friends you haven’t seen in 20 years, or fly high above your hometown, all in just one dream. Dreams have been studied by science, religion, and philosophy throughout history, and yet they are still not fully understood.

We do know that dreams occur mostly during the rapid-eye-movement stage of sleep, which is also known as the REM cycle. During your REM cycle, the activity in your brain is high, much like when you are awake, which is why your brain concocts stories that can look and feel real. While we sometimes know we are in a dream and that what we are experiencing isn’t real, dreams can feel very real while they are happening and sometimes even after we wake up. Dreams can occur during cycles of sleep other than REM, but when they do, they tend to be less vivid and memorable.

Dream lengths can range from five to about 20 minutes, although that amount of time in the dream world can feel warped. If you happen to be awakened during the REM phase, there is a higher chance that you will remember the dream after you wake up. The average person seems to have between three and six dreams per night and can spend up to two hours dreaming. One study found that dreams that are used for emotional memory processing take place in REM sleep, while dreams that relate to waking life experiences are usually associated with theta brainwaves.

Studying Dreams: What Do They Mean?

When it comes to figuring out what dreams mean, there is no one answer: it depends on whom you ask. Some people currently see dreams as connected to the unconscious mind, as Freud did, representing buried wishes and memories. Others believe that dreams can help us solve problems and consolidate memories, or that the images symbolize things that are important to us. Those who take a more biologically based approach might say that dreams can occur simply as the result of random brain activity.

There may also be a difference between lucid dreaming, where the dreamer is aware that they are in a dream and that they are able to control events within that dream, and regular dreaming— where the dream symbols and narrative are generally outside of the dreamer’s control. Whether in a lucid dream or a regular dream, dream images and events can be the source of creativity or inspiration that may change the dreamer’s life upon waking.

What Dreams Mean To You

Everyone dreams and our dreams can affect us strongly. Going through a process of dream interpreting can help you determine what aspect it represents in your life. If your dreams are disturbing you, or if you are simply interested in deciphering what they mean, dream therapy may be a good option.

The study revealed that dream work was used not only in psychoanalysis but also in therapies such as Gestalt therapy, client-centered therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Many of the therapists surveyed stated that dream therapy could have a significant impact on the success of treatment.

Dreams And Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist who is considered one of the founders of psychoanalysis. Along with many other elements of psychology, Freud is known for his work on dreams. Freud’s writings about dreams are considered groundbreaking because, for the most part, his contemporaries thought that dreams had no significance.

In his book The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung,1899), Freud explained his theories about dreams at length. Freud believed that dreams were a manifestation of our deepest and sometimes darkest anxieties, as well as our deepest (and again, sometimes darkest) desires. He tied dreams to repressed childhood fixations and memories. He believed that one function of dreams was the release of sexual tension, and his dream interpretations often held sexual meanings.

Freud believed that the actual meaning of dreams might be so unpleasant or taboo to the dreamer that their mind disguised them using less threatening images or symbols. Freud maintained that you could analyze the content of dreams to find their latent, or hidden, meanings. In other words, he believed that during a dream, an individual’s thoughts, memories, and feelings were turned into objects and symbols that could be interpreted to discover what the dream meant to that person.

Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams included guidelines that could be used to interpret various dream images. Although many other books on interpreting dreams have been written since, Freud’s study remains a seminal one.

Other Theoretical Approaches To Dreams

Freud’s approach to dream theory was mainly psychoanalytic or psychodynamic because it was based on the idea that the underlying causes for many mental processes, such as dreaming, were essentially unconscious. Further, Freud believed that the purpose of therapy was to bring those unconscious ideas, feelings, or urges into the light.

Alternate theories of interpreting dreams come from other psychological approaches. In addition to psychodynamic theory, some major approaches to psychology (and dreams) are humanistic, behavioral, cognitive, and neuroscientific. Each orientation views dreams as serving a different purpose, although some theories overlap.

The humanistic perspective psychology asserts that humans are constantly trying to better themselves and reach their full potential. As a result, dreams are interpreted as being about the self of the person having the dream, and how that person deals with external environments and stimuli. Humanistic theorists view the purpose of dreams, in part, as the mind regaining a sense of balance.

The behavioral approach views dreams as a result of environmental stimulation experienced by the dreamer. Since behaviorists do not believe in mental processes that cannot be directly observed, they do not focus on the memories or desires represented by dreams.

The cognitive approach focuses on the internal mental processes that occur while dreaming. Cognitive theory explores how individuals understand, think, and know about the world around them. Thus, the cognitive approach to dreaming holds that the purpose of dreams is to process information received throughout the day, and that dreaming is a way to remember, learn, and survive. Like the behavioral approach, the cognitive approach to dreaming does not view dreams as representing repressed memories or desires.

Finally, the neuroscientific approach focuses on biology, or the brain itself. The brain is filled with neurons that fire to process information. The neuroscientific approach to dreaming maintains that REM sleep triggers and releases memories that are stored in the brain. Dreams are not unconscious wishes, therefore, but rather a collection of random memories activated by electrical impulses.

Want To Understand What Your Dreams Mean To You?

Online Therapy With BetterHelp

Some people may benefit from therapeutic techniques such as dream work, but in today’s busy world, it can be hard to make time for in-person therapy. Online therapy through a service such as BetterHelp is a solution that may be more convenient for you. There’s no need to sit in traffic or take time out of your busy workday to drive to your appointment; you can speak with your licensed therapist from wherever you have an internet connection.

The Effectiveness Of Online Therapy

Studies have shown that online therapy can be an effective treatment for a variety of mental health concerns. In one study, researchers even found that psychotherapy delivered via the internet was just as “good if not better than face-to-face consultations.” Licensed therapists have helped clients overcome different problems using a variety of techniques, including dream work.

Read below for some reviews of BetterHelp therapists from people experiencing similar issues.

Counselor Reviews

“Jammie is an exceptional active listener. She takes what I say and repeats it back to me so I know that she understands what I am saying. That way she helps me interpret what I am feeling which helps me put my anxieties into perspective.”

“Carla is great. She is able to understand my issues and concerns and address them in a very thoughtful manner. She is very timely in her responses and always gives me some things to think about, which I think is important when you are trying to work through things. I very much recommend her.”

Takeaway

Dreams can also be doors into our unconscious thoughts and desires. Although there are many theories about why we dream and what dreams mean, thus far there seems to be no one answer to these questions. In the context of therapy, discussing dreams can help you heal from any mental or emotional challenges you may be facing. Further, an online therapist specialized in dream work can support you in understanding your dreams in more depth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can dreams really mean something?

The most recent study of dreams revealed quite a bit about how our brains function while we’re asleep. Research suggests we have different types of dreams based on our mental and emotional states. Therefore, a person’s general brain health can be brought into question based on the duration, frequency, and/or content of their dreams.

Aside from that, however, dreams can also uncover hidden mental illnesses, cognitive declines, or certain physical health problems. Take someone with sleep apnea, for example. Their nights will be constantly interrupted by inadequate breathing, so their dreams might seem ridiculous on account of REM sleep being cut short several times in one cycle. That’s why it’s important to use dream interpretation tools when considering brain function and mood.