Often you need to insert several words or letters from a language with accents like French or German. For example, to type a foreign company or person name.

Sure, you can install and use a language specific keyboard layout, but this is not advisable for rare operations. Also, you can use the Symbol dialog box to find and insert a symbol you need.

However, key combinations for different accents and other special characters in Work help faster enter foreign letters and words.

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with grave | Ctrl+` (grave accent), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter | Type 00c0 or 00C0 and press Alt+X | À |

| Latin capital letter E with grave | Type 00c8 or 00C8 and press Alt+X | È | |

| Latin capital letter I with grave | Type 00cc or 00CC and press Alt+X | Ì | |

| Latin capital letter O with grave | Type 00d2 or 00D2 and press Alt+X | Ò | |

| Latin capital letter U with grave | Type 00d9 or 00D9 and press Alt+X | Ù | |

| Latin small letter a with grave | Type 00e0 or 00E0 and press Alt+X | à | |

| Latin small letter e with grave | Type 00e8 or 00E8 and press Alt+X | è | |

| Latin small letter i with grave | Type 00ec or 00EC and press Alt+X | ì | |

| Latin small letter o with grave | Type 00f2 or 00F2 and press Alt+X | ò | |

| Latin small letter u with grave | Type 00f9 or 00F9 and press Alt+X | ù |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with acute | Ctrl+’ (apostrophe), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter | Type 00c1 or 00C1 and press Alt+X | Á |

| Latin capital letter E with acute | Type 00c9 or 00C9 and press Alt+X | É | |

| Latin capital letter I with acute | Type 00cd or 00CD and press Alt+X | Í | |

| Latin capital letter O with acute | Type 00d3 or 00D3 and press Alt+X | ù | |

| Latin capital letter U with acute | Type 00da or 00DA and press Alt+X | Ú | |

| Latin capital letter Y with acute | Type 00dd or 00DD and press Alt+X | Ý | |

| Latin small letter a with acute | Type 00e1 or 00E1 and press Alt+X | á | |

| Latin small letter e with acute | Type 00e9 or 00E9 and press Alt+X | é | |

| Latin small letter i with acute | Type 00ed or 00ED and press Alt+X | í | |

| Latin small letter o with acute | Type 00f3 or 00F3 and press Alt+X | ó | |

| Latin small letter u with acute | Type 00fa or 00FA and press Alt+X | ú | |

| Latin small letter y with acute | Type 00fd or 00FD and press Alt+X | ý |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with circumflex | Ctrl+Shift+^ (caret), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter | Type 00c2 or 00C2 and press Alt+X | Â |

| Latin capital letter E with circumflex | Type 00ca or 00CA and press Alt+X | Ê | |

| Latin capital letter I with circumflex | Type 00ce or 00CE and press Alt+X | Î | |

| Latin capital letter O with circumflex | Type 00d4 or 00D4 and press Alt+X | Ô | |

| Latin capital letter U with circumflex | Type 00db or 00DB and press Alt+X | Û | |

| Latin small letter a with circumflex | Type 00e2 or 00E2 and press Alt+X | â | |

| Latin small letter e with circumflex | Type 00ea or 00EA and press Alt+X | ê | |

| Latin small letter i with circumflex | Type 00ee or 00EE and press Alt+X | î | |

| Latin small letter o with circumflex | Type 00f4 or 00F4 and press Alt+X | ô | |

| Latin small letter u with circumflex | Type 00fb or 00FB and press Alt+X | û |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with tilde | Ctrl+Shift+~ (tilde), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter | Type 00c3 or 00C3 and press Alt+X | Ã |

| Latin capital letter N with tilde | Type 00d1 or 00D1 and press Alt+X | Ñ | |

| Latin capital letter O with tilde | Type 00d5 or 00D5 and press Alt+X | Õ | |

| Latin small letter a with tilde | Type 00e3 or 00E3 and press Alt+X | ã | |

| Latin small letter n with tilde | Type 00f1 or 00F1 and press Alt+X | ñ | |

| Latin small letter o with tilde | Type 00f5 or 00F5 and press Alt+X | õ |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with diaeresis | Ctrl+Shift+:, immediately type the capital or lowercase letter | Type 00c4 or 00C4 and press Alt+X | Ä |

| Latin capital letter E with diaeresis | Type 00cb or 00CB and press Alt+X | Ë | |

| Latin capital letter I with diaeresis | Type 00cf or 00CF and press Alt+X | Ï | |

| Latin capital letter O with diaeresis | Type 00d6 or 00D6 and press Alt+X | Ö | |

| Latin capital letter U with diaeresis | Type 00dc or 00DC and press Alt+X | Ü | |

| Latin capital letter Y with diaeresis | Type 0178 and press Alt+X | Ÿ | |

| Latin small letter a with dieresis | Type 00e4 or 00E4 and press Alt+X | ä | |

| Latin small letter e with dieresis | Type 00eb or 00EB and press Alt+X | ë | |

| Latin small letter i with dieresis | Type 00ef or 00EF and press Alt+X | ï | |

| Latin small letter o with dieresis | Type 00f6 or 00F6 and press Alt+X | ö | |

| Latin small letter u with dieresis | Type 00fC or 00FC and press Alt+X | ü | |

| Latin small letter y with dieresis | Type 00ff or 00FF and press Alt+X | ÿ |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter A with ring above | [email protected], immediately type the capital or lowercase letter a | Type 00c5 or 00C5 and press Alt+X | Å |

| Latin small letter a with tilde | Type 00e5 or 00E5 and press Alt+X | å | |

| Latin capital letter AE | Ctrl+Shift+&, immediately type the capital or lowercase letter a | Type 00c6 or 00C6 and press Alt+X | Æ |

| Latin small letter ae | Type 00e6 or 00E6 and press Alt+X | æ | |

| Latin capital ligature Oe | Ctrl+Shift+&, immediately type the capital or lowercase letter o | Type 0152 and press Alt+X | Π|

| Latin small ligature oe | Type 0153 and press Alt+X | œ | |

| Latin capital letter C with cedilla | Ctrl+, (comma), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter c | Type 00c7 or 00C7 and press Alt+X | Ç |

| Latin small letter c with cedilla | Type 00e7 or 00E7 and press Alt+X | ç | |

| Latin capital letter Eth | Ctrl+’ (apostrophe), immediately type the capital or lowercase letter d | Type 00d0 or 00D0 and press Alt+X | Ð |

| Latin small letter Eth | Type 00f0 or 00F0 and press Alt+X | ð |

| Shortcut | Unicode | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin capital letter C with cedilla | Ctrl+/, immediately type the capital or lowercase letter c | Type 00d8 or 00D8 and press Alt+X | Ø |

| Latin small letter c with cedilla | Type 00f8 or 00F8 and press Alt+X | ø | |

| Inverted exclamation mark | Alt+Ctrl+Shift+!

See How to insert inverted exclamation mark in Word for more details. |

Type 00a1 or 00A1 and press Alt+X | ¡ |

| Inverted question mark | Alt+Ctrl+Shift+?

See How to insert inverted question mark in Word for more details. |

Type 00bf or 00BF and press Alt+X | ¿ |

| Latin small letter sharp s | Ctrl+, (comma), immediately type the lowercase letter s | Type 00df or 00DF and press Alt+X | ß |

21 words unscrambled from the letters international.

21 words made by unscrambling the letters from international (aaeiilnnnortt). The unscrambled words are valid in Scrabble. Use the word unscrambler to unscramble more anagrams with some of the letters in international.

Words made from unscrambling the letters international

- 4 letter words

Word international definition

Read the dictionary definition of international. All definitions for this word.

1. any of several international socialist organizations

2. from or between other countries

1. external commerce

2. international trade

3. developing nations need outside help

3. concerning or belonging to all or at least two or more nations

1. international affairs

2. an international agreement

3. international waters

Is international an official Scrabble word?

Can the word international be used in Scrabble? Yes. This word is an official Scrabble word in the dictionary.

Unscrambling international Scrabble score

What are the highest scoring vowels and consonants? Unscrambling values for the Scrabble letters:

- I

- N

- T

- E

- R

- N

- A

- T

- I

- O

- N

- A

- L

The more words you know with these high value tiles the better chance of winning you have.

Unscramble words using the letters international

PC, Windows 7

There are a number of choices – quick list for Windows, setting up the International keyboard, setting up the keyboard for a specific language.

- Quick Accents for Windows – no changing to Int’l keyboard or specific language keyboard

The default keystrokes for accented characters are as follows:

Symbols joined by a + need to be held down at the same time;

Symbols separated by a comma need to be hit in sequence, one after the other.

|

á |

Ctrl + ‘ , A |

|

é |

Ctrl + ‘ , E |

|

í |

Ctrl + ‘ , I |

|

ó |

Ctrl + ‘ , O |

|

ú |

Ctrl + ‘ , U |

|

É |

Ctrl + ‘ , Shift + E |

|

ñ |

Ctrl + Shift + ~, N |

|

Ñ |

Ctrl + Shift + ~, Shift + N |

|

¿ |

Alt + Ctrl + Shift + ? |

|

¡ |

Alt + Ctrl + Shift + ! |

|

ü |

Ctrl + Shift + : , U |

CTRL+grave accent (the key to the left of the number “1” on the top row of keys) puts a grave accent over the next vowel typed. The “6” key becomes a circumflex accent when shifted, so CTRL+SHIFT+6 plus either “a”, “e”, “i”, “o”, or “u” generates “â”, “ê”, “î”, “ô”, and “û”, respectively. To put a cedilla underneath the letter “c”, use CTRL+comma before typing “c” or “C” to get “ç” or “Ç”. For other accent needs use the alt number method or insert characters.

2. Setting up the International Keyboard – uses punctuation as a code for the accents

- Go to Start, click on control panel

- region and language

- click on keyboards and languages tab

- change keyboards

- click on add on right

- click on + by English US

- check the box for US International, ok at the top right of that area

- then click apply, ok then ok

- at the bottom toolbar on the right, click on the keyboard icon and choose US International

- letters will remain the same, but punctuation like , ” will combine to do the accent as below

Creating international characters

When you press the APOSTROPHE ( ‘ ) key, QUOTATION MARK ( “ ) key, ACCENT GRAVE ( ` ) key, TILDE ( ~ ) key, or ACCENT CIRCUMFLEX,. also called the CARET key, ( ^) key, nothing is displayed on the screen until you press a second key:

- If you press one of the letters designated as eligible to receive an accent mark, the accented version of the letter appears.

- If you press the key of a character that is not eligible to receive an accent mark, two separate characters appear.

- If you press the space bar, the symbol (apostrophe, quotation mark, accent grave, tilde, accent circumflex or caret) is displayed by itself.

The following table shows the keyboard combinations that you can use to create the desired character.

| Press this key | Then press this key | Resulting character |

| ‘(APOSTROPHE) | c, e, y, u, i, o, a | ç, é, ý, ú, í, ó, á |

| “(QUOTATION MARK) | e, y, u, i, o, a | ë, ÿ, ü, ï, ö, ä |

| `(ACCENT GRAVE) | e, u, i, o, a | è, ù, ì, ò, à |

| ~(TILDE) | o, n, a | õ, ñ, ã |

| ^(CARET) | e, u, i, o, a | ê, û, î, ô, â |

To obtain the actual punctuation, hit the space bar after typing it.

MAC, OS X

Macintosh Option Codes for Accented Letters

|

ACCENT |

SAMPLE |

TEMPLATE |

NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | ó Ó | Option+E, V | |

| Circumflex | ô Ô | Option+I, V | |

| Grave | ò Ò | Option+`, V | |

| Tilde | õ Õ | Option+N, V | Only works with “n,N,o,O,a,A“ |

| Umlaut | ö Ö | Option+U, V |

Example 1: To input the letter ó, hold down the Option key, then the E key. Release both keys then type lowercase o.

Example 2: To input the letter Ó, hold down the Option key, then the E key. Release both keys then type capital O.

Other Foreign Characters

To insert these characters, press the Option key (bottom of keyboard) then other “code” key to make the symbol appear.

Macintosh Option Codes for Foreign Characters

|

SYMBOL |

NAME |

CODE |

|---|---|---|

| ¡ | Upside-down exclamation mark | Option+1 |

| ¿ | Upside-down question mark | Shift+Option+? |

| Ç,ç | French C cedille (caps/lowecase) | Shift+Option+C Option+C |

| Œ,œ | OE ligature (caps/lowecase) | Shift+Option+Q Option+Q |

| ß | German Sharp/Double S | Option+S |

| º, ª | Masculine Ordinal Number (Span/Ital/Portuguese) Feminine Ordinal Number |

Option+0 Option+9 |

| Ø,ø | Nordic O slash (caps/lowecase) | Shift+Option+O Option+O |

| Å,å | Nordic A ring (caps/lowecase) | Shift+Option+A Option+A |

| Æ,æ | AE ligature (caps/lowecase) | Shift+Option+’ (apostrophe key) Option+’ |

| « » | Spanish/French quotation marks | Option+ Shift+Option+ |

Example 1: To input French ç (Option+C), hold down the Option, then the C key. The ç will appear.

Example 2: To input French Ç (Shift+Option+C), hold down the Shift key, then the Option key,then the C key. The ç will appear

Microsoft Word Spell-checker for Languages

PC, Word 2010

- Click on the review tab at the top of the tool bar

- Down arrow on the Language icon

- Choose set proofing language

- Highlight language and click ok

- Choose language then begin typing paper or select all of the language area you want to review and then choose the proofing language

MAC, Word 2011

- Go to Tools at the top toolbar

- Choose language then begin typing paper or select all of the language area you want to review and then choose the proofing language

Total Number of words made out of International = 606

International is a 13 letter long Word starting with I and ending with L. Below are Total 606 words made out of this word.

11 letter Words made out of international

1). intentional 2). alternation 3). retaliation

10 letter Words made out of international

1). intolerant 2). alteration 3). alienation 4). literation

9 letter Words made out of international

1). nitration 2). iteration 3). natrolite 4). alienator 5). triennial 6). tretinoin 7). tarnation 8). itinerant 9). rationale 10). lineation 11). nonlinear 12). antialien 13). intention

8 letter Words made out of international

1). rational 2). oriental 3). anointer 4). attainer 5). lenition 6). antennal 7). annotate 8). literati 9). reattain 10). reanoint 11). alterant 12). antiarin 13). tolerant 14). nontitle 15). antiriot 16). notarial 17). national 18). intonate 19). triennia 20). natation 21). internal 22). troilite 23). aeration 24). trotline 25). inertial 26). neonatal 27). relation 28). tarletan

7 letter Words made out of international

1). antiair 2). entrant 3). latrine 4). antenna 5). intitle 6). antlion 7). retinal 8). retinol 9). inertia 10). iterant 11). entrain 12). reliant 13). elation 14). introit 15). intrant 16). lantern 17). enation 18). tannate 19). intreat 20). arnatto 21). rattail 22). arietta 23). intoner 24). ternion 25). tertial 26). tertian 27). tetanal 28). alation 29). aileron 30). triolet 31). lintier 32). airline 33). nittier 34). nitrite 35). nitrile 36). trenail 37). nattier 38). alanine 39). tontine 40). alienor 41). nitrate 42). nitinol 43). tritone 44). toenail 45). annatto 46). italian 47). aeolian 48). ratline 49). tortile 50). aeonian 51). tinnier 52). aniline 53). titania

6 letter Words made out of international

1). innate 2). rennin 3). intron 4). narial 5). neroli 6). nannie 7). loiter 8). retail 9). atonal 10). intort 11). intern 12). nailer 13). narine 14). intine 15). natant 16). rental 17). inlier 18). intent 19). retain 20). nation 21). natron 22). intone 23). natter 24). iolite 25). renail 26). reloan 27). linnet 28). norite 29). linier 30). latent 31). ratite 32). latino 33). latria 34). linear 35). oilier 36). latter 37). orient 38). lattin 39). ornate 40). ration 41). learnt 42). ratlin 43). linter 44). loaner 45). litter 46). litten 47). nitril 48). realia 49). ratton 50). lanate 51). rattle 52). lanner 53). ratten 54). rattan 55). lariat 56). larine 57). nonart 58). notate 59). ratine 60). retial 61). toilet 62). antral 63). tilter 64). latten 65). aortae 66). areola 67). tinner 68). aroint 69). tenant 70). tenail 71). aortal 72). atoner 73). atrial 74). tartan 75). attain 76). alanin 77). aliner 78). antler 79). anilin 80). tolane 81). anatto 82). titian 83). tonier 84). anneal 85). anoint 86). tonlet 87). tonner 88). tinter 89). toiler 90). tinier 91). torten 92). tineal 93). antiar 94). attire 95). attorn 96). retint 97). aerial 98). tailor 99). triton 100). entail 101). entoil 102). eolian 103). ronnel 104). eonian 105). tailer 106). taenia 107). etalon 108). rotten 109). online 110). talent 111). rotate 112). tannin 113). inaner 114). retina 115). trinal 116). tanner 117). rialto 118). talion 119). tarnal

5 letter Words made out of international

1). torte 2). tonne 3). latin 4). tolan 5). noria 6). nitro 7). trone 8). tonal 9). rotte 10). toner 11). nonet 12). nitre 13). treat 14). nerol 15). otter 16). trait 17). ninon 18). trine 19). triol 20). train 21). trail 22). trite 23). toter 24). niton 25). total 26). trona 27). niter 28). natal 29). torii 30). trial 31). notal 32). retia 33). tarot 34). reata 35). tatar 36). tater 37). telia 38). teloi 39). tenia 40). tenon 41). relit 42). tanto 43). renal 44). riant 45). riata 46). reoil 47). taint 48). talar 49). taler 50). talon 51). renin 52). terai 53). tetra 54). tiara 55). orate 56). olein 57). oiler 58). oater 59). oaten 60). noter 61). title 62). titre 63). oriel 64). titer 65). ottar 66). tiler 67). tinea 68). ratio 69). tenor 70). ratel 71). ratan 72). titan 73). ratal 74). toile 75). atria 76). lanai 77). elint 78). eloin 79). anole 80). laari 81). annal 82). linen 83). liner 84). linin 85). anion 86). enrol 87). anile 88). entia 89). anent 90). irone 91). anear 92). irate 93). intro 94). elain 95). antae 96). learn 97). atilt 98). artel 99). artal 100). leant 101). ariel 102). attar 103). latte 104). lento 105). arena 106). areal 107). later 108). laten 109). liane 110). aorta 111). atone 112). antra 113). alter 114). altar 115). inter 116). lotte 117). aline 118). alate 119). inane 120). loner 121). inert 122). inner 123). alert 124). alien 125). loran 126). antre 127). alant 128). inion 129). inlet 130). aioli 131). alane 132). alone 133). liana 134). liter 135). lirot 136). aalii 137). litai 138). naira 139). litre 140). aloin

4 letter Words made out of international

1). earn 2). tate 3). tart 4). taro 5). ilea 6). rile 7). riel 8). riot 9). roan 10). earl 11). tael 12). tail 13). elan 14). roti 15). tala 16). rote 17). tain 18). rota 19). role 20). tale 21). roil 22). tali 23). rite 24). enol 25). tare 26). tarn 27). rotl 28). ante 29). torn 30). tori 31). tore 32). tora 33). alto 34). tone 35). anal 36). tole 37). tola 38). toit 39). tort 40). aloe 41). alit 42). trot 43). aeon 44). aero 45). airn 46). trio 47). airt 48). alae 49). alan 50). tret 51). tote 52). anil 53). toil 54). tilt 55). tile 56). tier 57). area 58). aria 59). tern 60). tent 61). aril 62). tela 63). tear 64). alar 65). tine 66). anti 67). toea 68). anna 69). anoa 70). anon 71). tiro 72). tirl 73). tire 74). tint 75). anta 76). etna 77). teal 78). rate 79). liar 80). olea 81). lien 82). lier 83). line 84). note 85). nota 86). linn 87). lino 88). nori 89). neon 90). naoi 91). orle 92). leno 93). rant 94). rani 95). oral 96). rale 97). rain 98). rail 99). raia 100). lear 101). lent 102). lint 103). lion 104). nine 105). nett 106). lore 107). lorn 108). neat 109). near 110). lota 111). loti 112). naan 113). nail 114). nite 115). lone 116). loin 117). lira 118). none 119). lire 120). nona 121). noir 122). noil 123). noel 124). liri 125). lite 126). loan 127). nana 128). lean 129). rato 130). lari 131). rent 132). lair 133). iota 134). inro 135). real 136). ilia 137). inti 138). lane 139). into 140). inia 141). lati 142). lain 143). iron 144). rial 145). late 146). rein

3 letter Words made out of international

1). ion 2). not 3). tor 4). alt 5). ern 6). ire 7). tae 8). ana 9). lot 10). ton 11). ani 12). nor 13). eon 14). ane 15). era 16). lit 17). eta 18). aal 19). ait 20). ria 21). rin 22). air 23). ain 24). ail 25). nae 26). ala 27). inn 28). ten 29). rot 30). nit 31). tot 32). nil 33). ret 34). ale 35). net 36). roe 37). nan 38). toe 39). lat 40). rat 41). eat 42). ora 43). tan 44). ore 45). ear 46). tie 47). tel 48). ran 49). ate 50). tet 51). let 52). lar 53). ort 54). tao 55). tar 56). art 57). tin 58). tea 59). lin 60). tat 61). are 62). oar 63). oil 64). att 65). lie 66). rei 67). ole 68). ant 69). lea 70). lei 71). til 72). one 73). oat

2 letter Words made out of international

1). na 2). al 3). ae 4). it 5). aa 6). ai 7). in 8). at 9). ne 10). la 11). en 12). oe 13). re 14). on 15). an 16). ta 17). et 18). no 19). or 20). lo 21). ar 22). ti 23). er 24). li 25). el 26). to

International Meaning :- Between or among nations; pertaining to the intercourse of nations; participated in by two or more nations; common to- or affecting- two or more nations. Of or concerning the association called the International. The International; an abbreviated from of the title of the International Workingmen’s Association- the name of an association- formed in London in 1864- which has for object the promotion of the interests of the industrial classes of all nations. A member of the International Association.

Synonyms of International:- International, supranational, planetary, worldwide, foreign, transnational, global, multinational, internationalist, internationalistic, world, external, foreign, outside

Find Words which

Also see:-

- Vowel only words

- consonant only words

- 7 Letter words

- Words with J

- Words with Z

- Words with X

- Words with Q

- Words that start with Q

- Words that start with Z

- Words that start with F

- Words that start with X

Word Finder Tools

- Scrabble finder

- Words with friends finder

- Anagram Finder

- Crossword Solver

Note: . Anagrams are meaningful words made after rearranging all the letters of the word.

Search More words for viewing how many words can be made out of them

Note

There are 6 vowel letters and 7 consonant letters in the word international. I is 9th, N is 14th, T is 20th, E is 5th, R is 18th, A is 1st, O is 15th, L is 12th, Letter of Alphabet series.

Wordmaker is a website which tells you how many words you can make out of any given word in english language. we have tried our best to include every possible word combination of a given word. Its a good website for those who are looking for anagrams of a particular word. Anagrams are words made using each and every letter of the word and is of the same length as original english word. Most of the words meaning have also being provided to have a better understanding of the word. A cool tool for scrabble fans and english users, word maker is fastly becoming one of the most sought after english reference across the web.

List of Words Formed Using Letters of ‘international’

There are 200 words which can be formed using letters of the word ‘international‘

which can be formed using the letters from ‘international’:

which can be formed using the letters from ‘international’:

which can be formed using the letters from ‘international’:

Other Info & Useful Resources for the Word ‘international’

| Info | Details |

|---|---|

| Points in Scrabble for international | 13 |

| Points in Words with Friends for international | 17 |

| Number of Letters in international | 13 |

| More info About international | international |

| List of Words Starting with international | Words Starting With international |

| List of Words Ending with international | Words Ending With international |

| List of Words Containing international | Words Containing international |

| List of Anagrams of international | Anagrams of international |

| List of Words Formed by Letters of international | Words Created From international |

| international Definition at Wiktionary | Click Here |

| international Definition at Merriam-Webster | Click Here |

| international Definition at Dictionary | Click Here |

| international Synonyms At Thesaurus | Click Here |

| international Info At Wikipedia | Click Here |

| international Search Results on Google | Click Here |

| international Search Results on Bing | Click Here |

| Tweets About international on Twitter | Click Here |

For the international (civil) aviation organization (ICAO) spelling alphabet, see NATO phonetic alphabet.

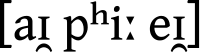

| International Phonetic Alphabet | |

|---|---|

«IPA» in IPA ([aɪ pʰiː eɪ]) |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet – partially featural |

|

Time period |

1888 to present |

| Languages | Used for phonetic and phonemic transcription of any language |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Palaeotype alphabet, English Phonotypic Alphabet

|

The official chart of the IPA, revised in 2020

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standardized representation of speech sounds in written form.[1] The IPA is used by lexicographers, foreign language students and teachers, linguists, speech–language pathologists, singers, actors, constructed language creators, and translators.[2][3]

The IPA is designed to represent those qualities of speech that are part of lexical (and, to a limited extent, prosodic) sounds in oral language: phones, phonemes, intonation, and the separation of words and syllables.[1] To represent additional qualities of speech—such as tooth gnashing, lisping, and sounds made with a cleft lip and cleft palate—an extended set of symbols may be used.[2]

Segments are transcribed by one or more IPA symbols of two basic types: letters and diacritics. For example, the sound of the English letter ⟨t⟩ may be transcribed in IPA with a single letter: [t], or with a letter plus diacritics: [t̺ʰ], depending on how precise one wishes to be. Slashes are used to signal phonemic transcription; therefore, /t/ is more abstract than either [t̺ʰ] or [t] and might refer to either, depending on the context and language.[note 1]

Occasionally, letters or diacritics are added, removed, or modified by the International Phonetic Association. As of the most recent change in 2005,[4] there are 107 segmental letters, an indefinitely large number of suprasegmental letters, 44 diacritics (not counting composites), and four extra-lexical prosodic marks in the IPA. Most of these are shown in the current IPA chart, posted below in this article and at the website of the IPA.[5]

History[edit]

In 1886, a group of French and British language teachers, led by the French linguist Paul Passy, formed what would be known from 1897 onwards as the International Phonetic Association (in French, l’Association phonétique internationale).[6] Their original alphabet was based on a spelling reform for English known as the Romic alphabet, but to make it usable for other languages the values of the symbols were allowed to vary from language to language.[note 2] For example, the sound [ʃ] (the sh in shoe) was originally represented with the letter ⟨c⟩ in English, but with the digraph ⟨ch⟩ in French.[6] In 1888, the alphabet was revised to be uniform across languages, thus providing the base for all future revisions.[6][7] The idea of making the IPA was first suggested by Otto Jespersen in a letter to Passy. It was developed by Alexander John Ellis, Henry Sweet, Daniel Jones, and Passy.[8]

Since its creation, the IPA has undergone a number of revisions. After revisions and expansions from the 1890s to the 1940s, the IPA remained primarily unchanged until the Kiel Convention in 1989. A minor revision took place in 1993 with the addition of four letters for mid central vowels[2] and the removal of letters for voiceless implosives.[9] The alphabet was last revised in May 2005 with the addition of a letter for a labiodental flap.[10] Apart from the addition and removal of symbols, changes to the IPA have consisted largely of renaming symbols and categories and in modifying typefaces.[2]

Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for speech pathology (extIPA) were created in 1990 and were officially adopted by the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association in 1994.[11]

Description[edit]

The general principle of the IPA is to provide one letter for each distinctive sound (speech segment).[note 3] This means that:

- It does not normally use combinations of letters to represent single sounds, the way English does with ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩ and ⟨ng⟩, or single letters to represent multiple sounds, the way ⟨x⟩ represents /ks/ or /ɡz/ in English.

- There are no letters that have context-dependent sound values, the way ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ in several European languages have a «hard» or «soft» pronunciation.

- The IPA does not usually have separate letters for two sounds if no known language makes a distinction between them, a property known as «selectiveness».[2][note 4] However, if a large number of phonemically distinct letters can be derived with a diacritic, that may be used instead.[note 5]

The alphabet is designed for transcribing sounds (phones), not phonemes, though it is used for phonemic transcription as well. A few letters that did not indicate specific sounds have been retired (⟨ˇ⟩, once used for the «compound» tone of Swedish and Norwegian, and ⟨ƞ⟩, once used for the moraic nasal of Japanese), though one remains: ⟨ɧ⟩, used for the sj-sound of Swedish. When the IPA is used for phonemic transcription, the letter–sound correspondence can be rather loose. For example, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are used in the IPA Handbook for /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/.

Among the symbols of the IPA, 107 letters represent consonants and vowels, 31 diacritics are used to modify these, and 17 additional signs indicate suprasegmental qualities such as length, tone, stress, and intonation.[note 6] These are organized into a chart; the chart displayed here is the official chart as posted at the website of the IPA.

Letter forms[edit]

Loop-tail ⟨g⟩ and open-tail ⟨ɡ⟩ are graphic variants. Open-tail ⟨ɡ⟩ was the original IPA symbol, but both are now considered correct. See history of the IPA for details.

The letters chosen for the IPA are meant to harmonize with the Latin alphabet.[note 7] For this reason, most letters are either Latin or Greek, or modifications thereof. Some letters are neither: for example, the letter denoting the glottal stop, ⟨ʔ⟩, originally had the form of a dotless question mark, and derives from an apostrophe. A few letters, such as that of the voiced pharyngeal fricative, ⟨ʕ⟩, were inspired by other writing systems (in this case, the Arabic letter ⟨ﻉ⟩, ʿayn, via the reversed apostrophe).[9]

Some letter forms derive from existing letters:

- The right-swinging tail, as in ⟨ʈ ɖ ɳ ɽ ʂ ʐ ɻ ɭ ⟩, indicates retroflex articulation. It originates from the hook of an r.

- The top hook, as in ⟨ɠ ɗ ɓ⟩, indicates implosion.

- Several nasal consonants are based on the form ⟨n⟩: ⟨n ɲ ɳ ŋ⟩. ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ŋ⟩ derive from ligatures of gn and ng, and ⟨ɱ⟩ is an ad hoc imitation of ⟨ŋ⟩.

- Letters turned 180 degrees for suggestive shapes, such as ⟨ɐ ɔ ə ɟ ɓ ɥ ɾ ɯ ɹ ʇ ʊ ʌ ʍ ʎ⟩ from ⟨a c e f ɡ h ᴊ m r t Ω v w y⟩.[note 8] Either the original letter may be reminiscent of the target sound (e.g., ⟨ɐ ə ɹ ʇ ʍ⟩) or the turned one (e.g., ⟨ɔ ɟ ɓ ɥ ɾ ɯ ʌ ʎ⟩). Rotation was popular in the era of mechanical typesetting, as it had the advantage of not requiring the casting of special type for IPA symbols, much as the sorts had traditionally often pulled double duty for ⟨b⟩ and ⟨q⟩, ⟨d⟩ and ⟨p⟩, ⟨n⟩ and ⟨u⟩, ⟨6⟩ and ⟨9⟩ to reduce cost.

-

An example of a font that uses turned small-capital omega, ⟨ꭥ⟩, for the vowel ⟨ʊ⟩. The symbol had originally been a small-capital ⟨ᴜ⟩.

-

- Among consonant letters, the small capital letters ⟨ɢ ʜ ʟ ɴ ʀ ʁ⟩, and also ⟨ꞯ⟩ in extIPA, indicate more guttural sounds than their base letters. (⟨ʙ⟩ is a late exception.) Among vowel letters, small capitals indicate «lax» vowels. Most of the original small-cap vowel letters have been modified into more distinctive shapes (e.g. ⟨ʊ ɤ ɛ ʌ⟩ from U Ɐ E A), with only ⟨ɪ ʏ⟩ remaining as small capitals.

Typography and iconicity[edit]

The International Phonetic Alphabet is based on the Latin script, and uses as few non-Latin letters as possible.[6] The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most letters would correspond to «international usage» (approximately Classical Latin).[6] Hence, the consonant letters ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨f⟩, (hard) ⟨ɡ⟩, (non-silent) ⟨h⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨k⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨p⟩, (voiceless) ⟨s⟩, (unaspirated) ⟨t⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨z⟩ have more or less the values found in English; and the vowel letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ correspond to the (long) sound values of Latin: [i] is like the vowel in machine, [u] is as in rule, etc. Other Latin letters, particularly ⟨j⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨y⟩, differ from English, but have their IPA values in Latin or other European languages.

This basic Latin inventory was extended by adding small-capital and cursive forms, diacritics and rotation. The sound values of these letters are related to those of the original letters, and their derivation may be iconic.[12] For example, letters with a rightward-facing hook at the bottom represent retroflex equivalents of the source letters, and small capital letters usually represent uvular equivalents of their source letters.

There are also several letters from the Greek alphabet, though their sound values may differ from Greek. The most extreme difference is ⟨ʋ⟩, which is a vowel in Greek but a consonant in the IPA. For most Greek letters, subtly different glyph shapes have been devised for the IPA, specifically ⟨ɑ⟩, ⟨ꞵ⟩, ⟨ɣ⟩, ⟨ɛ⟩, ⟨ɸ⟩, ⟨ꭓ⟩ and ⟨ʋ⟩, which are encoded in Unicode separately from their parent Greek letters. One, however – ⟨θ⟩ – has only its Greek form, while for ⟨ꞵ ~ β⟩ and ⟨ꭓ ~ χ⟩, both Greek and Latin forms are in common use.[13]

The tone letters are not derived from an alphabet, but from a pitch trace on a musical scale.

Beyond the letters themselves, there are a variety of secondary symbols which aid in transcription. Diacritic marks can be combined with IPA letters to add phonetic detail such as tone and secondary articulations. There are also special symbols for prosodic features such as stress and intonation.

Brackets and transcription delimiters[edit]

There are two principal types of brackets used to set off (delimit) IPA transcriptions:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| [ … ] | Square brackets are used with phonetic notation, whether broad or narrow[14] – that is, for actual pronunciation, possibly including details of the pronunciation that may not be used for distinguishing words in the language being transcribed, which the author nonetheless wishes to document. Such phonetic notation is the primary function of the IPA. |

| / … / | Slashes[note 9] are used for abstract phonemic notation,[14] which note only features that are distinctive in the language, without any extraneous detail. For example, while the ‘p’ sounds of English pin and spin are pronounced differently (and this difference would be meaningful in some languages), the difference is not meaningful in English. Thus, phonemically the words are usually analyzed as /ˈpɪn/ and /ˈspɪn/, with the same phoneme /p/. To capture the difference between them (the allophones of /p/), they can be transcribed phonetically as [pʰɪn] and [spɪn]. Phonemic notation commonly uses IPA symbols that are rather close to the default pronunciation of a phoneme, but for legibility or other reasons can use symbols that diverge from their designated values, such as /c, ɟ/ for affricates typically pronounced [t͜ʃ, d͜ʒ], as found in the Handbook, or /r/, which in phonetic notation is a trill, for English r even when pronounced [ɹʷ]. |

Other conventions are less commonly seen:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| { … } | Braces («curly brackets») are used for prosodic notation.[15] See Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for examples in this system. |

| ( … ) | Parentheses are used for indistinguishable[14] or unidentified utterances. They are also seen for silent articulation (mouthing),[16] where the expected phonetic transcription is derived from lip-reading, and with periods to indicate silent pauses, for example (…) or (2 sec). The latter usage is made official in the extIPA, with unidentified segments circled.[17] |

| ⸨ … ⸩ | Double parentheses indicate either a transcription of obscured speech or a description of the obscuring noise. The IPA specifies that they mark the obscured sound,[15] as in ⸨2σ⸩, two audible syllables obscured by another sound. The current extIPA specifications prescribe double parentheses for the extraneous noise, such as ⸨cough⸩ or ⸨knock⸩ for a knock on a door, but the IPA Handbook identifies IPA and extIPA usage as equivalent.[18] Early publications of the extIPA explain double parentheses as marking «uncertainty because of noise which obscures the recording,» and that within them «may be indicated as much detail as the transcriber can detect.»[19] |

All three of the above are provided by the IPA Handbook. The following are not, but may be seen in IPA transcription or in associated material (especially angle brackets):

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| ⟦ … ⟧ | Double square brackets are used for extra-precise (especially narrow) transcription. This is consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree. Double brackets may indicate that a letter has its cardinal IPA value. For example, ⟦a⟧ is an open front vowel, rather than the perhaps slightly different value (such as open central) that «[a]» may be used to transcribe in a particular language. Thus, two vowels transcribed for easy legibility as ⟨[e]⟩ and ⟨[ɛ]⟩ may be clarified as actually being ⟦e̝⟧ and ⟦e⟧; ⟨[ð]⟩ may be more precisely ⟦ð̠̞ˠ⟧.[20] Double brackets may also be used for a specific token or speaker; for example, the pronunciation of a child as opposed to the adult phonetic pronunciation that is their target.[21] |

| ⫽ … ⫽ | … | ‖ … ‖ { … } |

Double slashes are used for morphophonemic transcription. This is also consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree (in this case, more abstract than phonemic transcription).

Other symbols sometimes seen for morphophonemic transcription are pipes and double pipes, from Americanist phonetic notation; and braces from set theory, especially when enclosing the set of phonemes that constitute the morphophoneme, e.g. {t d} or {t|d} or {/t/, /d/}. Only double slashes are unambiguous: both pipes and braces conflict with IPA prosodic transcription.[note 10] See morphophonology for examples. |

| ⟨ … ⟩ ⟪ … ⟫ |

Angle brackets[note 11] are used to mark both original Latin orthography and transliteration from another script; they are also used to identify individual graphemes of any script.[22][23] Within the IPA, they are used to indicate the IPA letters themselves rather than the sound values that they carry. Double angle brackets may occasionally be useful to distinguish original orthography from transliteration, or the idiosyncratic spelling of a manuscript from the normalized orthography of the language.

For example, ⟨cot⟩ would be used for the orthography of the English word cot, as opposed to its pronunciation /ˈkɒt/. Italics are usual when words are written as themselves (as with cot in the previous sentence) rather than to specifically note their orthography. However, italic markup is not evident to sight-impaired readers who rely on screen reader technology. |

Some examples of contrasting brackets in the literature:

In some English accents, the phoneme /l/, which is usually spelled as ⟨l⟩ or ⟨ll⟩, is articulated as two distinct allophones: the clear [l] occurs before vowels and the consonant /j/, whereas the dark [ɫ]/[lˠ] occurs before consonants, except /j/, and at the end of words.[24]

the alternations /f/ – /v/ in plural formation in one class of nouns, as in knife /naɪf/ – knives /naɪvz/, which can be represented morphophonemically as {naɪV} – {naɪV+z}. The morphophoneme {V} stands for the phoneme set {/f/, /v/}.[25]

[ˈffaɪnəlz ˈhɛld ɪn (.) ⸨knock on door⸩ bɑɹsə{𝑝ˈloʊnə and ˈmədɹɪd 𝑝}] — f-finals held in Barcelona and Madrid.[26]

Other representations[edit]

IPA letters have cursive forms designed for use in manuscripts and when taking field notes, but the 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association recommended against their use, as cursive IPA is «harder for most people to decipher.»[27] A braille representation of the IPA for blind or visually impaired professionals and students has also been developed.[28]

Modifying the IPA chart[edit]

The authors of textbooks or similar publications often create revised versions of the IPA chart to express their own preferences or needs. The image displays one such version. All pulmonic consonants are moved to the consonant chart. Only the black symbols are on the official IPA chart; additional symbols are in grey. The grey fricatives are part of the extIPA, and the grey retroflex letters are mentioned or implicit in the Handbook. The grey click is a retired IPA letter that is still in use.

The International Phonetic Alphabet is occasionally modified by the Association. After each modification, the Association provides an updated simplified presentation of the alphabet in the form of a chart. (See History of the IPA.) Not all aspects of the alphabet can be accommodated in a chart of the size published by the IPA. The alveolo-palatal and epiglottal consonants, for example, are not included in the consonant chart for reasons of space rather than of theory (two additional columns would be required, one between the retroflex and palatal columns and the other between the pharyngeal and glottal columns), and the lateral flap would require an additional row for that single consonant, so they are listed instead under the catchall block of «other symbols».[29] The indefinitely large number of tone letters would make a full accounting impractical even on a larger page, and only a few examples are shown, and even the tone diacritics are not complete; the reversed tone letters are not illustrated at all.

The procedure for modifying the alphabet or the chart is to propose the change in the Journal of the IPA. (See, for example, August 2008 on an open central unrounded vowel and August 2011 on central approximants.)[30] Reactions to the proposal may be published in the same or subsequent issues of the Journal (as in August 2009 on the open central vowel).[31] A formal proposal is then put to the Council of the IPA[32] – which is elected by the membership[33] – for further discussion and a formal vote.[34][35]

Nonetheless, many users of the alphabet, including the leadership of the Association itself, deviate from this norm.[note 12]

The Journal of the IPA finds it acceptable to mix IPA and extIPA symbols in consonant charts in their articles. (For instance, including the extIPA letter ⟨𝼆⟩, rather than ⟨ʎ̝̊⟩, in an illustration of the IPA.)[36]

Usage[edit]

Of more than 160 IPA symbols, relatively few will be used to transcribe speech in any one language, with various levels of precision. A precise phonetic transcription, in which sounds are specified in detail, is known as a narrow transcription. A coarser transcription with less detail is called a broad transcription. Both are relative terms, and both are generally enclosed in square brackets.[1] Broad phonetic transcriptions may restrict themselves to easily heard details, or only to details that are relevant to the discussion at hand, and may differ little if at all from phonemic transcriptions, but they make no theoretical claim that all the distinctions transcribed are necessarily meaningful in the language.

Phonetic transcriptions of the word international in two English dialects

For example, the English word little may be transcribed broadly as [ˈlɪtəl], approximately describing many pronunciations. A narrower transcription may focus on individual or dialectical details: [ˈɫɪɾɫ] in General American, [ˈlɪʔo] in Cockney, or [ˈɫɪːɫ] in Southern US English.

Phonemic transcriptions, which express the conceptual counterparts of spoken sounds, are usually enclosed in slashes (/ /) and tend to use simpler letters with few diacritics. The choice of IPA letters may reflect theoretical claims of how speakers conceptualize sounds as phonemes or they may be merely a convenience for typesetting. Phonemic approximations between slashes do not have absolute sound values. For instance, in English, either the vowel of pick or the vowel of peak may be transcribed as /i/, so that pick, peak would be transcribed as /ˈpik, ˈpiːk/ or as /ˈpɪk, ˈpik/; and neither is identical to the vowel of the French pique which would also be transcribed /pik/. By contrast, a narrow phonetic transcription of pick, peak, pique could be: [pʰɪk], [pʰiːk], [pikʲ].

Linguists[edit]

IPA is popular for transcription by linguists. Some American linguists, however, use a mix of IPA with Americanist phonetic notation or use some nonstandard symbols for various reasons.[37] Authors who employ such nonstandard use are encouraged to include a chart or other explanation of their choices, which is good practice in general, as linguists differ in their understanding of the exact meaning of IPA symbols and common conventions change over time.

Dictionaries[edit]

English[edit]

Many British dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary and some learner’s dictionaries such as the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary and the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, now use the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent the pronunciation of words.[38] However, most American (and some British) volumes use one of a variety of pronunciation respelling systems, intended to be more comfortable for readers of English and to be more acceptable across dialects, without the implication of a preferred pronunciation that the IPA might convey. For example, the respelling systems in many American dictionaries (such as Merriam-Webster) use ⟨y⟩ for IPA [ j] and ⟨sh⟩ for IPA [ ʃ ], reflecting the usual spelling of those sounds in English.[39]

(In IPA, [y] represents the sound of the French ⟨u⟩, as in tu, and [sh] represents the sequence of consonants in grasshopper.)

Other languages[edit]

The IPA is also not universal among dictionaries in languages other than English. Monolingual dictionaries of languages with phonemic orthographies generally do not bother with indicating the pronunciation of most words, and tend to use respelling systems for words with unexpected pronunciations. Dictionaries produced in Israel use the IPA rarely and sometimes use the Hebrew alphabet for transcription of foreign words.[note 13] Bilingual dictionaries that translate from foreign languages into Russian usually employ the IPA, but monolingual Russian dictionaries occasionally use pronunciation respelling for foreign words.[note 14] The IPA is more common in bilingual dictionaries, but there are exceptions here too. Mass-market bilingual Czech dictionaries, for instance, tend to use the IPA only for sounds not found in Czech.[40]

Standard orthographies and case variants[edit]

IPA letters have been incorporated into the alphabets of various languages, notably via the Africa Alphabet in many sub-Saharan languages such as Hausa, Fula, Akan, Gbe languages, Manding languages, Lingala, etc. Capital case variants have been created for use in these languages. For example, Kabiyè of northern Togo has Ɖ ɖ, Ŋ ŋ, Ɣ ɣ, Ɔ ɔ, Ɛ ɛ, Ʋ ʋ. These, and others, are supported by Unicode, but appear in Latin ranges other than the IPA extensions.

In the IPA itself, however, only lower-case letters are used. The 1949 edition of the IPA handbook indicated that an asterisk ⟨*⟩ might be prefixed to indicate that a word was a proper name,[41] but this convention was not included in the 1999 Handbook, which notes the contrary use of the asterisk as a placeholder for a sound or feature that does not have a symbol.

Classical singing[edit]

The IPA has widespread use among classical singers during preparation as they are frequently required to sing in a variety of foreign languages. They are also taught by vocal coaches to perfect diction and improve tone quality and tuning.[42] Opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA, such as Nico Castel’s volumes[43] and Timothy Cheek’s book Singing in Czech.[44] Opera singers’ ability to read IPA was used by the site Visual Thesaurus, which employed several opera singers «to make recordings for the 150,000 words and phrases in VT’s lexical database … for their vocal stamina, attention to the details of enunciation, and most of all, knowledge of IPA».[45]

Letters[edit]

The International Phonetic Association organizes the letters of the IPA into three categories: pulmonic consonants, non-pulmonic consonants, and vowels.[46][47]

Pulmonic consonant letters are arranged singly or in pairs of voiceless (tenuis) and voiced sounds, with these then grouped in columns from front (labial) sounds on the left to back (glottal) sounds on the right. In official publications by the IPA, two columns are omitted to save space, with the letters listed among ‘other symbols’ even though theoretically they belong in the main chart,[note 15] and with the remaining consonants arranged in rows from full closure (occlusives: stops and nasals), to brief closure (vibrants: trills and taps), to partial closure (fricatives) and minimal closure (approximants), again with a row left out to save space. In the table below, a slightly different arrangement is made: All pulmonic consonants are included in the pulmonic-consonant table, and the vibrants and laterals are separated out so that the rows reflect the common lenition pathway of stop → fricative → approximant, as well as the fact that several letters pull double duty as both fricative and approximant; affricates may be created by joining stops and fricatives from adjacent cells. Shaded cells represent articulations that are judged to be impossible.

Vowel letters are also grouped in pairs—of unrounded and rounded vowel sounds—with these pairs also arranged from front on the left to back on the right, and from maximal closure at top to minimal closure at bottom. No vowel letters are omitted from the chart, though in the past some of the mid central vowels were listed among the ‘other symbols’.

Consonants[edit]

Pulmonic consonants[edit]

A pulmonic consonant is a consonant made by obstructing the glottis (the space between the vocal cords) or oral cavity (the mouth) and either simultaneously or subsequently letting out air from the lungs. Pulmonic consonants make up the majority of consonants in the IPA, as well as in human language. All consonants in English fall into this category.[48]

The pulmonic consonant table, which includes most consonants, is arranged in rows that designate manner of articulation, meaning how the consonant is produced, and columns that designate place of articulation, meaning where in the vocal tract the consonant is produced. The main chart includes only consonants with a single place of articulation.

Notes

- In rows where some letters appear in pairs (the obstruents), the letter to the right represents a voiced consonant (except breathy-voiced [ɦ]).[49] In the other rows (the sonorants), the single letter represents a voiced consonant.

- While IPA provides a single letter for the coronal places of articulation (for all consonants but fricatives), these do not always have to be used exactly. When dealing with a particular language, the letters may be treated as specifically dental, alveolar, or post-alveolar, as appropriate for that language, without diacritics.

- Shaded areas indicate articulations judged to be impossible.

- The letters [β, ð, ʁ, ʕ, ʢ] are canonically voiced fricatives but may be used for approximants.[50]

- In many languages, such as English, [h] and [ɦ] are not actually glottal, fricatives, or approximants. Rather, they are bare phonation.[51]

- It is primarily the shape of the tongue rather than its position that distinguishes the fricatives [ʃ ʒ], [ɕ ʑ], and [ʂ ʐ].

- [ʜ, ʢ] are defined as epiglottal fricatives under the «Other symbols» section in the official IPA chart, but they may be treated as trills at the same place of articulation as [ħ, ʕ] because trilling of the aryepiglottic folds typically co-occurs.[52]

- Some listed phones are not known to exist as phonemes in any language.

Non-pulmonic consonants[edit]

Non-pulmonic consonants are sounds whose airflow is not dependent on the lungs. These include clicks (found in the Khoisan languages and some neighboring Bantu languages of Africa), implosives (found in languages such as Sindhi, Hausa, Swahili and Vietnamese), and ejectives (found in many Amerindian and Caucasian languages).

Notes

- Clicks have traditionally been described as consisting of a forward place of articulation, commonly called the click ‘type’ or historically the ‘influx’, and a rear place of articulation, which when combined with the voicing, aspiration, nasalization, affrication, ejection, timing etc. of the click is commonly called the click ‘accompaniment’ or historically the ‘efflux’. The IPA click letters indicate only the click type (forward articulation and release). Therefore, all clicks require two letters for proper notation: ⟨k͡ǂ, ɡ͡ǂ, ŋ͡ǂ, q͡ǂ, ɢ͡ǂ, ɴ͡ǂ⟩ etc., or with the order reversed if both the forward and rear releases are audible. The letter for the rear articulation is frequently omitted, in which case a ⟨k⟩ may usually be assumed. However, some researchers dispute the idea that clicks should be analyzed as doubly articulated, as the traditional transcription implies, and analyze the rear occlusion as solely a part of the airstream mechanism.[53] In transcriptions of such approaches, the click letter represents both places of articulation, with the different letters representing the different click types, and diacritics are used for the elements of the accompaniment: ⟨ǂ, ǂ̬, ǂ̃⟩ etc.

- Letters for the voiceless implosives ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ are no longer supported by the IPA, though they remain in Unicode. Instead, the IPA typically uses the voiced equivalent with a voiceless diacritic: ⟨ɓ̥, ʛ̥⟩, etc..

- The letter for the retroflex implosive, ⟨ᶑ ⟩, is not «explicitly IPA approved» (Handbook, p. 166), but has the expected form if such a symbol were to be approved.

- The ejective diacritic is placed at the right-hand margin of the consonant, rather than immediately after the letter for the stop: ⟨t͜ʃʼ⟩, ⟨kʷʼ⟩. In imprecise transcription, it often stands in for a superscript glottal stop in glottalized but pulmonic sonorants, such as [mˀ], [lˀ], [wˀ], [aˀ] (also transcribable as creaky [m̰], [l̰], [w̰], [a̰]).

Affricates[edit]

Affricates and co-articulated stops are represented by two letters joined by a tie bar, either above or below the letters with no difference in meaning.[note 16] Affricates are optionally represented by ligatures (e.g. ⟨ʦ, ʣ, ʧ, ʤ, ʨ, ʥ, ꭧ, ꭦ ⟩), though this is no longer official IPA usage[1] because a great number of ligatures would be required to represent all affricates this way. Alternatively, a superscript notation for a consonant release is sometimes used to transcribe affricates, for example ⟨tˢ⟩ for [t͜s], paralleling [kˣ] ~ [k͜x]. The letters for the palatal plosives ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are often used as a convenience for [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ] or similar affricates, even in official IPA publications, so they must be interpreted with care.

Co-articulated consonants[edit]

Co-articulated consonants are sounds that involve two simultaneous places of articulation (are pronounced using two parts of the vocal tract). In English, the [w] in «went» is a coarticulated consonant, being pronounced by rounding the lips and raising the back of the tongue. Similar sounds are [ʍ] and [ɥ]. In some languages, plosives can be double-articulated, for example in the name of Laurent Gbagbo.

Notes

- [ɧ], the Swedish sj-sound, is described by the IPA as a «simultaneous [ʃ] and [x]«, but it is unlikely such a simultaneous fricative actually exists in any language.[54]

- Multiple tie bars can be used: ⟨a͡b͡c⟩ or ⟨a͜b͜c⟩. For instance, if a prenasalized stop is transcribed ⟨m͡b⟩, and a doubly articulated stop ⟨ɡ͡b⟩, then a prenasalized doubly articulated stop would be ⟨ŋ͡m͡ɡ͡b⟩

- If a diacritic needs to be placed on or under a tie bar, the combining grapheme joiner (U+034F) needs to be used, as in [b͜͏̰də̀bdɷ̀] ‘chewed’ (Margi). Font support is spotty, however.

Vowels[edit]

Tongue positions of cardinal front vowels, with highest point indicated. The position of the highest point is used to determine vowel height and backness.

The IPA defines a vowel as a sound which occurs at a syllable center.[55] Below is a chart depicting the vowels of the IPA. The IPA maps the vowels according to the position of the tongue.

The vertical axis of the chart is mapped by vowel height. Vowels pronounced with the tongue lowered are at the bottom, and vowels pronounced with the tongue raised are at the top. For example, [ɑ] (the first vowel in father) is at the bottom because the tongue is lowered in this position. [i] (the vowel in «meet») is at the top because the sound is said with the tongue raised to the roof of the mouth.

In a similar fashion, the horizontal axis of the chart is determined by vowel backness. Vowels with the tongue moved towards the front of the mouth (such as [ɛ], the vowel in «met») are to the left in the chart, while those in which it is moved to the back (such as [ʌ], the vowel in «but») are placed to the right in the chart.

In places where vowels are paired, the right represents a rounded vowel (in which the lips are rounded) while the left is its unrounded counterpart.

Diphthongs[edit]

Diphthongs are typically specified with a non-syllabic diacritic, as in ⟨uɪ̯⟩ or ⟨u̯ɪ⟩, or with a superscript for the on- or off-glide, as in ⟨uᶦ⟩ or ⟨ᵘɪ⟩. Sometimes a tie bar is used: ⟨u͡ɪ⟩, especially if it is difficult to tell if the diphthong is characterized by an on-glide, an off-glide or is variable.

Notes

- ⟨a⟩ officially represents a front vowel, but there is little if any distinction between front and central open vowels (see Vowel § Acoustics), and ⟨a⟩ is frequently used for an open central vowel.[37] If disambiguation is required, the retraction diacritic or the centralized diacritic may be added to indicate an open central vowel, as in ⟨a̠⟩ or ⟨ä⟩.

Diacritics and prosodic notation [edit]

Diacritics are used for phonetic detail. They are added to IPA letters to indicate a modification or specification of that letter’s normal pronunciation.[56]

By being made superscript, any IPA letter may function as a diacritic, conferring elements of its articulation to the base letter. Those superscript letters listed below are specifically provided for by the IPA Handbook; other uses can be illustrated with ⟨tˢ⟩ ([t] with fricative release), ⟨ᵗs⟩ ([s] with affricate onset), ⟨ⁿd⟩ (prenasalized [d]), ⟨bʱ⟩ ([b] with breathy voice), ⟨mˀ⟩ (glottalized [m]), ⟨sᶴ⟩ ([s] with a flavor of [ʃ], i.e. a voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant), ⟨oᶷ⟩ ([o] with diphthongization), ⟨ɯᵝ⟩ (compressed [ɯ]). Superscript diacritics placed after a letter are ambiguous between simultaneous modification of the sound and phonetic detail at the end of the sound. For example, labialized ⟨kʷ⟩ may mean either simultaneous [k] and [w] or else [k] with a labialized release. Superscript diacritics placed before a letter, on the other hand, normally indicate a modification of the onset of the sound (⟨mˀ⟩ glottalized [m], ⟨ˀm⟩ [m] with a glottal onset). (See § Superscript IPA.)

| Syllabicity diacritics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◌̩ | ɹ̩ n̩ | Syllabic | ◌̯ | ɪ̯ ʊ̯ | Non-syllabic |

| ◌̍ | ɻ̍ ŋ̍ | ◌̑ | y̑ | ||

| Consonant-release diacritics | |||||

| ◌ʰ | tʰ | Aspirated[a] | ◌̚ | p̚ | No audible release |

| ◌ⁿ | dⁿ | Nasal release | ◌ˡ | dˡ | Lateral release |

| ◌ᶿ | tᶿ | Voiceless dental fricative release | ◌ˣ | tˣ | Voiceless velar fricative release |

| ◌ᵊ | dᵊ | Mid central vowel release | |||

| Phonation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̥ | n̥ d̥ | Voiceless | ◌̬ | s̬ t̬ | Voiced |

| ◌̊ | ɻ̊ ŋ̊ | ||||

| ◌̤ | b̤ a̤ | Breathy voiced[a] | ◌̰ | b̰ a̰ | Creaky voiced |

| Articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̪ | t̪ d̪ | Dental | ◌̼ | t̼ d̼ | Linguolabial |

| ◌͆ | ɮ͆ | ||||

| ◌̺ | t̺ d̺ | Apical | ◌̻ | t̻ d̻ | Laminal |

| ◌̟ | u̟ t̟ | Advanced (fronted) | ◌̠ | i̠ t̠ | Retracted (backed) |

| ◌᫈ | ɡ᫈ | ◌̄ | q̄[b] | ||

| ◌̈ | ë ä | Centralized | ◌̽ | e̽ ɯ̽ | Mid-centralized |

| ◌̝ | e̝ r̝ | Raised ([r̝], [ɭ˔] are fricatives) |

◌̞ | e̞ β̞ | Lowered ([β̞], [ɣ˕] are approximants) |

| ◌˔ | ɭ˔ | ◌˕ | y˕ ɣ˕ | ||

| Co-articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̹ | ɔ̹ x̹ | More rounded (over-rounding) |

◌̜ | ɔ̜ xʷ̜ | Less rounded (under-rounding)[c] |

| ◌͗ | y͗ χ͗ | ◌͑ | y͑ χ͑ʷ | ||

| ◌ʷ | tʷ dʷ | Labialized | ◌ʲ | tʲ dʲ | Palatalized |

| ◌ˠ | tˠ dˠ | Velarized | ◌̴ | ɫ ᵶ | Velarized or pharyngealized |

| ◌ˤ | tˤ aˤ | Pharyngealized | |||

| ◌̘ | e̘ o̘ | Advanced tongue root | ◌̙ | e̙ o̙ | Retracted tongue root |

| ◌꭪ | y꭪ | ◌꭫ | y꭫ | ||

| ◌̃ | ẽ z̃ | Nasalized | ◌˞ | ɚ ɝ | Rhoticity |

Notes

- ^a With aspirated voiced consonants, the aspiration is usually also voiced (voiced aspirated – but see voiced consonants with voiceless aspiration). Many linguists prefer one of the diacritics dedicated to breathy voice over simple aspiration, such as ⟨b̤⟩. Some linguists restrict that diacritic to sonorants, such as breathy-voice ⟨m̤⟩, and transcribe voiced-aspirated obstruents as e.g. ⟨bʱ⟩.

- ^b Care must be taken that a superscript retraction sign is not mistaken for mid tone.

- ^c These are relative to the cardinal value of the letter. They can also apply to unrounded vowels: [ɛ̜] is more spread (less rounded) than cardinal [ɛ], and [ɯ̹] is less spread than cardinal [ɯ].[57]

Since ⟨xʷ⟩ can mean that the [x] is labialized (rounded) throughout its articulation, and ⟨x̜⟩ makes no sense ([x] is already completely unrounded), ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ can only mean a less-labialized/rounded [xʷ]. However, readers might mistake ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ for «[x̜]» with a labialized off-glide, or might wonder if the two diacritics cancel each other out. Placing the ‘less rounded’ diacritic under the labialization diacritic, ⟨xʷ̜⟩, makes it clear that it is the labialization that is ‘less rounded’ than its cardinal IPA value.

Subdiacritics (diacritics normally placed below a letter) may be moved above a letter to avoid conflict with a descender, as in voiceless ⟨ŋ̊⟩.[56] The raising and lowering diacritics have optional spacing forms ⟨˔⟩, ⟨˕⟩ that avoid descenders.

The state of the glottis can be finely transcribed with diacritics. A series of alveolar plosives ranging from open-glottis to closed-glottis phonation is:

| Open glottis | [t] | voiceless |

|---|---|---|

| [d̤] | breathy voice, also called murmured | |

| [d̥] | slack voice | |

| Sweet spot | [d] | modal voice |

| [d̬] | stiff voice | |

| [d̰] | creaky voice | |

| Closed glottis | [ʔ͡t] | glottal closure |

Additional diacritics are provided by the Extensions to the IPA for speech pathology.

Suprasegmentals[edit]

These symbols describe the features of a language above the level of individual consonants and vowels, that is, at the level of syllable, word or phrase. These include prosody, pitch, length, stress, intensity, tone and gemination of the sounds of a language, as well as the rhythm and intonation of speech.[58] Various ligatures of pitch/tone letters and diacritics are provided for by the Kiel Convention and used in the IPA Handbook despite not being found in the summary of the IPA alphabet found on the one-page chart.

Under capital letters below we will see how a carrier letter may be used to indicate suprasegmental features such as labialization or nasalization. Some authors omit the carrier letter, for e.g. suffixed [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ or prefixed [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟],[59] or place a spacing variant of a diacritic such as ⟨˔⟩ or ⟨˜⟩ at the beginning or end of a word to indicate that it applies to the entire word.[60]

| Length, stress, and rhythm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ˈke | Primary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

ˌke | Secondary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

| eː kː | Long (long vowel or geminate consonant) |

eˑ | Half-long |

| ə̆ ɢ̆ | Extra-short | ||

| ek.ste eks.te |

Syllable break (internal boundary) |

es‿e | Linking (lack of a boundary; a phonological word)[note 17] |

| Intonation | |||

| | | Minor or foot break | ‖ | Major or intonation break |

| ↗︎ | Global rise[note 18] | ↘︎ | Global fall[note 18] |

| Up- and down-step | |||

| ꜛke | Upstep | ꜜke | Downstep |

| Pitch diacritics[note 19] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ŋ̋ e̋ | Extra high | ŋ̌ ě | Rising | ŋ᷄ e᷄ | Mid-rising |

| ŋ́ é | High | ŋ̂ ê | Falling | ŋ᷅ e᷅ | Low-rising |

| ŋ̄ ē | Mid | ŋ᷈ e᷈ | Peaking (rising–falling) | ŋ᷇ e᷇ | High-falling |

| ŋ̀ è | Low | ŋ᷉ e᷉ | Dipping (falling–rising) | ŋ᷆ e᷆ | Mid-falling |

| ŋ̏ ȅ | Extra low | (etc.)[note 20] |

| Chao tone letters[note 19] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ˥e | ꜒e | e˥ | e꜒ | High |

| ˦e | ꜓e | e˦ | e꜓ | Half-high |

| ˧e | ꜔e | e˧ | e꜔ | Mid |

| ˨e | ꜕e | e˨ | e꜕ | Half-low |

| ˩e | ꜖e | e˩ | e꜖ | Low |

| ˩˥e | ꜖꜒e | e˩˥ | e꜖꜒ | Rising (low to high or generic) |

| ˥˩e | ꜒꜖e | e˥˩ | e꜒꜖ | Falling (high to low or generic) |

| (etc.) |

The old staveless tone letters, which are effectively obsolete, include high ⟨ˉe⟩, mid ⟨˗e⟩, low ⟨ˍe⟩, rising ⟨ˊe⟩ and falling ⟨ˋe⟩.

Stress[edit]

Officially, the stress marks ⟨ˈ ˌ⟩ appear before the stressed syllable, and thus mark the syllable boundary as well as stress (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a period).[61] Occasionally the stress mark is placed immediately before the nucleus of the syllable, after any consonantal onset.[62] In such transcriptions, the stress mark does not mark a syllable boundary. The primary stress mark may be doubled ⟨ˈˈ⟩ for extra stress (such as prosodic stress). The secondary stress mark is sometimes seen doubled ⟨ˌˌ⟩ for extra-weak stress, but this convention has not been adopted by the IPA.[61] Some dictionaries place both stress marks before a syllable, ⟨¦⟩, to indicate that pronunciations with either primary or secondary stress are heard, though this is not IPA usage.[63]

Boundary markers[edit]

There are three boundary markers: ⟨.⟩ for a syllable break, ⟨|⟩ for a minor prosodic break and ⟨‖⟩ for a major prosodic break. The tags ‘minor’ and ‘major’ are intentionally ambiguous. Depending on need, ‘minor’ may vary from a foot break to a break in list-intonation to a continuing–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a comma), and while ‘major’ is often any intonation break, it may be restricted to a final–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a period). The ‘major’ symbol may also be doubled, ⟨‖‖⟩, for a stronger break.[note 21]

Although not part of the IPA, the following additional boundary markers are often used in conjunction with the IPA: ⟨μ⟩ for a mora or mora boundary, ⟨σ⟩ for a syllable or syllable boundary, ⟨+⟩ for a morpheme boundary, ⟨#⟩ for a word boundary (may be doubled, ⟨##⟩, for e.g. a breath-group boundary),[65] ⟨$⟩ for a phrase or intermediate boundary and ⟨%⟩ for a prosodic boundary. For example, C# is a word-final consonant, %V a post-pausa vowel, and T% an IU-final tone (edge tone).

Pitch and tone[edit]

⟨ꜛ ꜜ⟩ are defined in the Handbook as «upstep» and «downstep», concepts from tonal languages. However, the upstep symbol can also be used for pitch reset, and the IPA Handbook uses it for prosody in the illustration for Portuguese, a non-tonal language.

Phonetic pitch and phonemic tone may be indicated by either diacritics placed over the nucleus of the syllable (e.g., high-pitch ⟨é⟩) or by Chao tone letters placed either before or after the word or syllable. There are three graphic variants of the tone letters: with or without a stave, and facing left or facing right from the stave. The stave was introduced with the 1989 Kiel Convention, as was the option of placing a staved letter after the word or syllable, while retaining the older conventions. There are therefore six ways to transcribe pitch/tone in the IPA: i.e., ⟨é⟩, ⟨˦e⟩, ⟨e˦⟩, ⟨꜓e⟩, ⟨e꜓⟩ and ⟨ˉe⟩ for a high pitch/tone.[61][66][67] Of the tone letters, only left-facing staved letters and a few representative combinations are shown in the summary on the Chart, and in practice it is currently more common for tone letters to occur after the syllable/word than before, as in the Chao tradition. Placement before the word is a carry-over from the pre-Kiel IPA convention, as is still the case for the stress and upstep/downstep marks. The IPA endorses the Chao tradition of using the left-facing tone letters, ⟨˥ ˦ ˧ ˨ ˩⟩, for underlying tone, and the right-facing letters, ⟨꜒ ꜓ ꜔ ꜕ ꜖⟩, for surface tone, as occurs in tone sandhi, and for the intonation of non-tonal languages.[note 22] In the Portuguese illustration in the 1999 Handbook, tone letters are placed before a word or syllable to indicate prosodic pitch (equivalent to [↗︎] global rise and [↘︎] global fall, but allowing more precision), and in the Cantonese illustration they are placed after a word/syllable to indicate lexical tone. Theoretically therefore prosodic pitch and lexical tone could be simultaneously transcribed in a single text, though this is not a formalized distinction.

Rising and falling pitch, as in contour tones, are indicated by combining the pitch diacritics and letters in the table, such as grave plus acute for rising [ě] and acute plus grave for falling [ê]. Only six combinations of two diacritics are supported, and only across three levels (high, mid, low), despite the diacritics supporting five levels of pitch in isolation. The four other explicitly approved rising and falling diacritic combinations are high/mid rising [e᷄], low rising [e᷅], high falling [e᷇], and low/mid falling [e᷆].[note 23]

The Chao tone letters, on the other hand, may be combined in any pattern, and are therefore used for more complex contours and finer distinctions than the diacritics allow, such as mid-rising [e˨˦], extra-high falling [e˥˦], etc. There are 20 such possibilities. However, in Chao’s original proposal, which was adopted by the IPA in 1989, he stipulated that the half-high and half-low letters ⟨˦ ˨⟩ may be combined with each other, but not with the other three tone letters, so as not to create spuriously precise distinctions. With this restriction, there are 8 possibilities.[68]

The old staveless tone letters tend to be more restricted than the staved letters, though not as restricted as the diacritics. Officially, they support as many distinctions as the staved letters,[69] but typically only three pitch levels are distinguished. Unicode supports default or high-pitch ⟨ˉ ˊ ˋ ˆ ˇ ˜ ˙⟩ and low-pitch ⟨ˍ ˏ ˎ ꞈ ˬ ˷⟩. Only a few mid-pitch tones are supported (such as ⟨˗ ˴⟩), and then only accidentally.

Although tone diacritics and tone letters are presented as equivalent on the chart, «this was done only to simplify the layout of the chart. The two sets of symbols are not comparable in this way.»[70] Using diacritics, a high tone is ⟨é⟩ and a low tone is ⟨è⟩; in tone letters, these are ⟨e˥⟩ and ⟨e˩⟩. One can double the diacritics for extra-high ⟨e̋⟩ and extra-low ⟨ȅ⟩; there is no parallel to this using tone letters. Instead, tone letters have mid-high ⟨e˦⟩ and mid-low ⟨e˨⟩; again, there is no equivalent among the diacritics.

The correspondence breaks down even further once they start combining. For more complex tones, one may combine three or four tone diacritics in any permutation,[61] though in practice only generic peaking (rising-falling) e᷈ and dipping (falling-rising) e᷉ combinations are used. Chao tone letters are required for finer detail (e˧˥˧, e˩˨˩, e˦˩˧, e˨˩˦, etc.). Although only 10 peaking and dipping tones were proposed in Chao’s original, limited set of tone letters, phoneticians often make finer distinctions, and indeed an example is found on the IPA Chart.[note 24] The system allows the transcription of 112 peaking and dipping pitch contours, including tones that are level for part of their length.

| Register | Level [note 26] |

Rising | Falling | Peaking | Dipping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e˩ | e˩˩ | e˩˧ | e˧˩ | e˩˧˩ | e˧˩˧ |

| e˨ | e˨˨ | e˨˦ | e˦˨ | e˨˦˨ | e˦˨˦ |

| e˧ | e˧˧ | e˧˥ | e˥˧ | e˧˥˧ | e˥˧˥ |

| e˦ | e˦˦ | e˧˥˩ | e˧˩˥ | ||

| e˥ | e˥˥ | e˩˥ | e˥˩ | e˩˥˧ | e˥˩˧ |

More complex contours are possible. Chao gave an example of [꜔꜒꜖꜔] (mid-high-low-mid) from English prosody.[68]

Chao tone letters generally appear after each syllable, for a language with syllable tone (⟨a˧vɔ˥˩⟩), or after the phonological word, for a language with word tone (⟨avɔ˧˥˩⟩). The IPA gives the option of placing the tone letters before the word or syllable (⟨˧a˥˩vɔ⟩, ⟨˧˥˩avɔ⟩), but this is rare for lexical tone. (And indeed reversed tone letters may be used to clarify that they apply to the following rather than to the preceding syllable: ⟨꜔a꜒꜖vɔ⟩, ⟨꜔꜒꜖avɔ⟩.) The staveless letters are not directly supported by Unicode, but some fonts allow the stave in Chao tone letters to be suppressed.

Comparative degree[edit]

IPA diacritics may be doubled to indicate an extra degree of the feature indicated.[71] This is a productive process, but apart from extra-high and extra-low tones ⟨ə̋, ə̏⟩ being marked by doubled high- and low-tone diacritics, and the major prosodic break ⟨‖⟩ being marked as a double minor break ⟨|⟩, it is not specifically regulated by the IPA. (Note that transcription marks are similar: double slashes indicate extra (morpho)-phonemic, double square brackets especially precise, and double parentheses especially unintelligible.)

For example, the stress mark may be doubled to indicate an extra degree of stress, such as prosodic stress in English.[72] An example in French, with a single stress mark for normal prosodic stress at the end of each prosodic unit (marked as a minor prosodic break), and a double stress mark for contrastive/emphatic stress: [ˈˈɑ̃ːˈtre | məˈsjø ‖ ˈˈvwala maˈdam ‖] Entrez monsieur, voilà madame.[73] Similarly, a doubled secondary stress mark ⟨ˌˌ⟩ is commonly used for tertiary (extra-light) stress.[74] In a similar vein, the effectively obsolete (though never retired) staveless tone letters were once doubled for an emphatic rising intonation ⟨˶⟩ and an emphatic falling intonation ⟨˵⟩.[75]

Length is commonly extended by repeating the length mark, as in English shhh! [ʃːːː], or for «overlong» segments in Estonian:

- vere /vere/ ‘blood [gen.sg.]’, veere /veːre/ ‘edge [gen.sg.]’, veere /veːːre/ ‘roll [imp. 2nd sg.]’

- lina /linɑ/ ‘sheet’, linna /linːɑ/ ‘town [gen. sg.]’, linna /linːːɑ/ ‘town [ine. sg.]’

(Normally additional degrees of length are handled by the extra-short or half-long diacritic, but the first two words in each of the Estonian examples are analyzed as simply short and long, requiring a different remedy for the final words.)

Occasionally other diacritics are doubled:

- Rhoticity in Badaga /be/ «mouth», /be˞/ «bangle», and /be˞˞/ «crop».[76]

- Mild and strong aspirations, [kʰ], [kʰʰ].[note 27]

- Nasalization, as in Palantla Chinantec lightly nasalized /ẽ/ vs heavily nasalized /e͌/,[77] though in extIPA the latter indicates velopharyngeal frication.

- Weak vs strong ejectives, [kʼ], [kˮ].[78]

- Especially lowered, e.g. [t̞̞] (or [t̞˕], if the former symbol does not display properly) for /t/ as a weak fricative in some pronunciations of register.[79]

- Especially retracted, e.g. [ø̠̠] or [s̠̠],[80][71][81] though some care might be needed to distinguish this from indications of alveolar or alveolarized articulation in extIPA, e.g. [s͇].

- The transcription of strident and harsh voice as extra-creaky /a᷽/ may be motivated by the similarities of these phonations.

Ambiguous letters[edit]

A number of IPA letters are not consistently used for their official values. A distinction between voiced fricatives and approximants is only partially implemented by the IPA, for example. Even with the relatively recent addition of the palatal fricative ⟨ʝ⟩ and the velar approximant ⟨ɰ⟩ to the alphabet, other letters, though defined as fricatives, are often ambiguous between fricative and approximant. For forward places, ⟨β⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ can generally be assumed to be fricatives unless they carry a lowering diacritic. Rearward, however, ⟨ʁ⟩ and ⟨ʕ⟩ are perhaps more commonly intended to be approximants even without a lowering diacritic. ⟨h⟩ and ⟨ɦ⟩ are similarly either fricatives or approximants, depending on the language, or even glottal «transitions», without that often being specified in the transcription.