From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can be described as the ability to perceive or infer information, and to retain it as knowledge to be applied towards adaptive behaviors within an environment or context.

Intelligence is most often studied in humans but has also been observed in both non-human animals and in plants despite controversy as to whether some of these forms of life exhibit intelligence.[1][2] Intelligence in computers or other machines is called artificial intelligence.

Etymology[edit]

Main article: Nous

The word intelligence derives from the Latin nouns intelligentia or intellēctus, which in turn stem from the verb intelligere, to comprehend or perceive. In the Middle Ages, the word intellectus became the scholarly technical term for understanding, and a translation for the Greek philosophical term nous. This term, however, was strongly linked to the metaphysical and cosmological theories of teleological scholasticism, including theories of the immortality of the soul, and the concept of the active intellect (also known as the active intelligence). This approach to the study of nature was strongly rejected by the early modern philosophers such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and David Hume, all of whom preferred «understanding» (in place of «intellectus» or «intelligence») in their English philosophical works.[3][4] Hobbes for example, in his Latin De Corpore, used «intellectus intelligit«, translated in the English version as «the understanding understandeth», as a typical example of a logical absurdity.[5] «Intelligence» has therefore become less common in English language philosophy, but it has later been taken up (with the scholastic theories which it now implies) in more contemporary psychology.[6]

Definitions[edit]

Unsolved problem in philosophy:

What exactly is intelligence? How could an external observer prove that an agent is intelligent?

The definition of intelligence is controversial, varying in what its abilities are and whether or not it is quantifiable.[7] Some groups of psychologists have suggested the following definitions:

From «Mainstream Science on Intelligence» (1994), an op-ed statement in the Wall Street Journal signed by fifty-two researchers (out of 131 total invited to sign):[8]

A very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience. It is not merely book learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings—»catching on,» «making sense» of things, or «figuring out» what to do.[9]

From Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (1995), a report published by the Board of Scientific Affairs of the American Psychological Association:

Individuals differ from one another in their ability to understand complex ideas, to adapt effectively to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning, to overcome obstacles by taking thought. Although these individual differences can be substantial, they are never entirely consistent: a given person’s intellectual performance will vary on different occasions, in different domains, as judged by different criteria. Concepts of «intelligence» are attempts to clarify and organize this complex set of phenomena. Although considerable clarity has been achieved in some areas, no such conceptualization has yet answered all the important questions, and none commands universal assent. Indeed, when two dozen prominent theorists were recently asked to define intelligence, they gave two dozen, somewhat different, definitions.[10]

Besides those definitions, psychology and learning researchers also have suggested definitions of intelligence such as the following:

| Researcher | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Alfred Binet | Judgment, otherwise called «good sense», «practical sense», «initiative», the faculty of adapting one’s self to circumstances … auto-critique.[11] |

| David Wechsler | The aggregate or global capacity of the individual to act purposefully, to think rationally, and to deal effectively with his environment.[12] |

| Lloyd Humphreys | «…the resultant of the process of acquiring, storing in memory, retrieving, combining, comparing, and using in new contexts information and conceptual skills».[13] |

| Howard Gardner | To my mind, a human intellectual competence must entail a set of skills of problem solving — enabling the individual to resolve genuine problems or difficulties that he or she encounters and, when appropriate, to create an effective product — and must also entail the potential for finding or creating problems — and thereby laying the groundwork for the acquisition of new knowledge.[14] |

| Linda Gottfredson | The ability to deal with cognitive complexity.[15] |

| Robert Sternberg & William Salter | Goal-directed adaptive behavior.[16] |

| Reuven Feuerstein | The theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability describes intelligence as «the unique propensity of human beings to change or modify the structure of their cognitive functioning to adapt to the changing demands of a life situation».[17] |

| Shane Legg & Marcus Hutter | A synthesis of 70+ definitions from psychology, philosophy, and AI researchers: «Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments»,[7] which has been mathematically formalized.[18] |

| Alexander Wissner-Gross | F = T ∇ S [19] [19]

«Intelligence is a force, F, that acts so as to maximize future freedom of action. It acts to maximize future freedom of action, or keep options open, with some strength T, with the diversity of possible accessible futures, S, up to some future time horizon, τ. In short, intelligence doesn’t like to get trapped». |

Human[edit]

Human intelligence is the intellectual power of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness.[20] Intelligence enables humans to remember descriptions of things and use those descriptions in future behaviors. It is a cognitive process. It gives humans the cognitive abilities to learn, form concepts, understand, and reason, including the capacities to recognize patterns, innovate, plan, solve problems, and employ language to communicate. Intelligence enables humans to experience and think.[21]

Intelligence is different from learning. Learning refers to the act of retaining facts and information or abilities and being able to recall them for future use, while intelligence is the cognitive ability of someone to perform these and other processes. There have been various attempts to quantify intelligence via testing, such as the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test. However, many people disagree with the validity of IQ tests, stating that they cannot accurately measure intelligence.[22]

There is debate about if human intelligence is based on hereditary factors or if it is based on environmental factors. Hereditary intelligence is the theory that intelligence is fixed upon birth and not able to grow. Environmental intelligence is the theory that intelligence is developed throughout life depending on the environment around the person. An environment that cultivates intelligence is one that challenges the person’s cognitive abilities.[22]

Much of the above definition applies also to the intelligence of non-human animals.[citation needed]

Emotional[edit]

Emotional intelligence is thought to be the ability to convey emotion to others in an understandable way as well as to read the emotions of others accurately.[23] Some theories imply that a heightened emotional intelligence could also lead to faster generating and processing of emotions in addition to the accuracy.[24] In addition, higher emotional intelligence is thought to help us manage emotions, which is beneficial for our problem-solving skills. Emotional intelligence is important to our mental health and has ties into social intelligence.[23]

[edit]

Social intelligence is the ability to understand the social cues and motivations of others and oneself in social situations. It is thought to be distinct to other types of intelligence, but has relations to emotional intelligence. Social intelligence has coincided with other studies that focus on how we make judgements of others, the accuracy with which we do so, and why people would be viewed as having positive or negative social character. There is debate as to whether or not these studies and social intelligence come from the same theories or if there is a distinction between them, and they are generally thought to be of two different schools of thought.[25]

Book smart and street smart[edit]

Concepts of «book smarts» and «street smart» are contrasting views based on the premise that some people have knowledge gained through academic study, but may lack the experience to sensibly apply that knowledge, while others have knowledge gained through practical experience, but may lack accurate information usually gained through study by which to effectively apply that knowledge. Artificial intelligence researcher Hector Levesque has noted that:

Given the importance of learning through text in our own personal lives and in our culture, it is perhaps surprising how utterly dismissive we tend to be of it. It is sometimes derided as being merely «book knowledge,» and having it is being «book smart.» In contrast, knowledge acquired through direct experience and apprenticeship is called «street knowledge,» and having it is being «street smart».[26]

Nonhuman animal[edit]

Although humans have been the primary focus of intelligence researchers, scientists have also attempted to investigate animal intelligence, or more broadly, animal cognition. These researchers are interested in studying both mental ability in a particular species, and comparing abilities between species. They study various measures of problem solving, as well as numerical and verbal reasoning abilities. Some challenges in this area are defining intelligence so that it has the same meaning across species (e.g. comparing intelligence between literate humans and illiterate animals), and also operationalizing a measure that accurately compares mental ability across different species and contexts.[citation needed]

Wolfgang Köhler’s research on the intelligence of apes is an example of research in this area. Stanley Coren’s book, The Intelligence of Dogs is a notable book on the topic of dog intelligence.[27] (See also: Dog intelligence.) Non-human animals particularly noted and studied for their intelligence include chimpanzees, bonobos (notably the language-using Kanzi) and other great apes, dolphins, elephants and to some extent parrots, rats and ravens.[28]

Cephalopod intelligence also provides an important comparative study. Cephalopods appear to exhibit characteristics of significant intelligence, yet their nervous systems differ radically from those of backboned animals. Vertebrates such as mammals, birds, reptiles and fish have shown a fairly high degree of intellect that varies according to each species. The same is true with arthropods.[29]

g factor in non-humans[edit]

Evidence of a general factor of intelligence has been observed in non-human animals. The general factor of intelligence, or g factor, is a psychometric construct that summarizes the correlations observed between an individual’s scores on a wide range of cognitive abilities. First described in humans, the g factor has since been identified in a number of non-human species.[30]

Cognitive ability and intelligence cannot be measured using the same, largely verbally dependent, scales developed for humans. Instead, intelligence is measured using a variety of interactive and observational tools focusing on innovation, habit reversal, social learning, and responses to novelty. Studies have shown that g is responsible for 47% of the individual variance in cognitive ability measures in primates[30] and between 55% and 60% of the variance in mice (Locurto, Locurto). These values are similar to the accepted variance in IQ explained by g in humans (40–50%).[31]

Plant[edit]

It has been argued that plants should also be classified as intelligent based on their ability to sense and model external and internal environments and adjust their morphology, physiology and phenotype accordingly to ensure self-preservation and reproduction.[32][33]

A counter argument is that intelligence is commonly understood to involve the creation and use of persistent memories as opposed to computation that does not involve learning. If this is accepted as definitive of intelligence, then it includes the artificial intelligence of robots capable of «machine learning», but excludes those purely autonomic sense-reaction responses that can be observed in many plants. Plants are not limited to automated sensory-motor responses, however, they are capable of discriminating positive and negative experiences and of «learning» (registering memories) from their past experiences. They are also capable of communication, accurately computing their circumstances, using sophisticated cost–benefit analysis and taking tightly controlled actions to mitigate and control the diverse environmental stressors.[1][2][34]

Artificial[edit]

Scholars studying artificial intelligence have proposed definitions of intelligence that include the intelligence demonstrated by machines. Some of these definitions are meant to be general enough to encompass human and other animal intelligence as well. An intelligent agent can be defined as a system that perceives its environment and takes actions which maximize its chances of success.[35] Kaplan and Haenlein define artificial intelligence as «a system’s ability to correctly interpret external data, to learn from such data, and to use those learnings to achieve specific goals and tasks through flexible adaptation».[36] Progress in artificial intelligence can be demonstrated in benchmarks ranging from games to practical tasks such as protein folding.[37] Existing AI lags humans in terms of general intelligence, which is sometimes defined as the «capacity to learn how to carry out a huge range of tasks».[38]

Singularitarian Eliezer Yudkowsky provides a loose qualitative definition of intelligence as «that sort of smartish stuff coming out of brains, which can play chess, and price bonds, and persuade people to buy bonds, and invent guns, and figure out gravity by looking at wandering lights in the sky; and which, if a machine intelligence had it in large quantities, might let it invent molecular nanotechnology; and so on». Mathematician Olle Häggström defines intelligence in terms of «optimization power», an agent’s capacity for efficient cross-domain optimization of the world according to the agent’s preferences, or more simply the ability to «steer the future into regions of possibility ranked high in a preference ordering». In this optimization framework, Deep Blue has the power to «steer a chessboard’s future into a subspace of possibility which it labels as ‘winning’, despite attempts by Garry Kasparov to steer the future elsewhere.»[39] Hutter and Legg, after surveying the literature, define intelligence as «an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments».[40][41] While cognitive ability is sometimes measured as a one-dimensional parameter, it could also be represented as a «hypersurface in a multidimensional space» to compare systems that are good at different intellectual tasks.[42] Some skeptics believe that there is no meaningful way to define intelligence, aside from «just pointing to ourselves».[43]

See also[edit]

- Active intellect

- Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory

- Intellect

- Intelligence (journal)

- Knowledge

- Neuroscience and intelligence

- Noogenesis – Philosophical concept of biosphere successor via humankind’s rational activities

- Outline of human intelligence

- Passive intellect

- Superintelligence

- Sapience

References[edit]

- ^ a b Goh, C. H.; Nam, H. G.; Park, Y. S. (2003). «Stress memory in plants: A negative regulation of stomatal response and transient induction of rd22 gene to light in abscisic acid-entrained Arabidopsis plants». The Plant Journal. 36 (2): 240–255. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01872.x. PMID 14535888.

- ^ a b Volkov, A. G.; Carrell, H.; Baldwin, A.; Markin, V. S. (2009). «Electrical memory in Venus flytrap». Bioelectrochemistry. 75 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.03.005. PMID 19356999.

- ^ Maich, Aloysius (1995). A Hobbes Dictionary. Blackwell. p. 305.

- ^ Nidditch, Peter. «Foreword». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Oxford University Press. p. xxii.

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas; Molesworth, William (15 February 1839). «Opera philosophica quæ latine scripsit omnia, in unum corpus nunc primum collecta studio et labore Gulielmi Molesworth .» Londoni, apud Joannem Bohn. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ This paragraph almost verbatim from Goldstein, Sam; Princiotta, Dana; Naglieri, Jack A., Eds. (2015). Handbook of Intelligence: Evolutionary Theory, Historical Perspective, and Current Concepts. New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London: Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4939-1561-3.

- ^ a b S. Legg; M. Hutter (2007). «A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence». Advances in Artificial General Intelligence: Concepts, Architectures and Algorithms. Vol. 157. pp. 17–24. ISBN 9781586037581.

- ^ Gottfredson & 1997777, pp. 17–20

- ^ Gottfredson, Linda S. (1997). «Mainstream Science on Intelligence (editorial)» (PDF). Intelligence. 24: 13–23. doi:10.1016/s0160-2896(97)90011-8. ISSN 0160-2896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2014.

- ^ Neisser, Ulrich; Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert; Sternberg, Robert J.; Urbina, Susana (1996). «Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns» (PDF). American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.51.2.77. ISSN 0003-066X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Binet, Alfred (1916) [1905]. «New methods for the diagnosis of the intellectual level of subnormals». The development of intelligence in children: The Binet-Simon Scale. E.S. Kite (Trans.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 37–90. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

originally published as Méthodes nouvelles pour le diagnostic du niveau intellectuel des anormaux. L’Année Psychologique, 11, 191–244

- ^ Wechsler, D (1944). The measurement of adult intelligence. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-19-502296-4. OCLC 219871557. ASIN = B000UG9J7E

- ^ Humphreys, L. G. (1979). «The construct of general intelligence». Intelligence. 3 (2): 105–120. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(79)90009-6.

- ^ Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0-465-02510-7. OCLC 221932479.

- ^ Gottfredson, L. (1998). «The General Intelligence Factor» (PDF). Scientific American Presents. 9 (4): 24–29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ Sternberg RJ; Salter W (1982). Handbook of human intelligence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29687-8. OCLC 11226466.

- ^ Feuerstein, R., Feuerstein, S., Falik, L & Rand, Y. (1979; 2002). Dynamic assessments of cognitive modifiability. ICELP Press, Jerusalem: Israel; Feuerstein, R. (1990). The theory of structural modifiability. In B. Presseisen (Ed.), Learning and thinking styles: Classroom interaction. Washington, DC: National Education Associations

- ^ S. Legg; M. Hutter (2007). «Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence». Minds and Machines. 17 (4): 391–444. arXiv:0712.3329. Bibcode:2007arXiv0712.3329L. doi:10.1007/s11023-007-9079-x. S2CID 847021.

- ^ «TED Speaker: Alex Wissner-Gross: A new equation for intelligence». TED.com. 6 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Tirri, Nokelainen (2011). Measuring Multiple Intelligences and Moral Sensitivities in Education. Moral Development and Citizenship Education. Springer. ISBN 978-94-6091-758-5. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ Colom, Roberto (December 2010). «Human intelligence and brain networks». Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12 (4): 489–501. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/rcolom. PMC 3181994. PMID 21319494.

- ^ a b Bouchard, Thomas J. (1982). «Review of The Intelligence Controversy». The American Journal of Psychology. 95 (2): 346–349. doi:10.2307/1422481. ISSN 0002-9556. JSTOR 1422481.

- ^ a b Salovey, Peter; Mayer, John D. (March 1990). «Emotional Intelligence». Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 9 (3): 185–211. doi:10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG. hdl:10654/36316. ISSN 0276-2366. S2CID 219900460.

- ^ Mayer, John D.; Salovey, Peter (1 October 1993). «The intelligence of emotional intelligence». Intelligence. 17 (4): 433–442. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(93)90010-3. ISSN 0160-2896.

- ^ Walker, Ronald E.; Foley, Jeanne M. (December 1973). «Social Intelligence: Its History and Measurement». Psychological Reports. 33 (3): 839–864. doi:10.2466/pr0.1973.33.3.839. ISSN 0033-2941. S2CID 144839425.

- ^ Hector J. Levesque, Common Sense, the Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI (2017), p. 80.

- ^ Coren, Stanley (1995). The Intelligence of Dogs. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-37452-0. OCLC 30700778.

- ^ Childs, Casper. «WORDS WITH AN ASTRONAUT». Valenti. Codetipi. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Roth, Gerhard (19 December 2015). «Convergent evolution of complex brains and high intelligence». Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 370 (1684): 20150049. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0049. PMC 4650126. PMID 26554042.

- ^ a b Reader, S. M., Hager, Y., & Laland, K. N. (2011). The evolution of primate general and cultural intelligence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1017–1027.

- ^ Kamphaus, R. W. (2005). Clinical assessment of child and adolescent intelligence. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ Trewavas, Anthony (September 2005). «Green plants as intelligent organisms». Trends in Plant Science. 10 (9): 413–419. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.005. PMID 16054860.

- ^ Trewavas, A. (2002). «Mindless mastery». Nature. 415 (6874): 841. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..841T. doi:10.1038/415841a. PMID 11859344. S2CID 4350140.

- ^ Rensing, L.; Koch, M.; Becker, A. (2009). «A comparative approach to the principal mechanisms of different memory systems». Naturwissenschaften. 96 (12): 1373–1384. Bibcode:2009NW…..96.1373R. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0591-0. PMID 19680619. S2CID 29195832.

- ^ Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-790395-5. OCLC 51325314.

- ^ «Kaplan Andreas and Haelein Michael (2019) Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence, Business Horizons, 62(1)».

- ^ «How did a company best known for playing games just crack one of science’s toughest puzzles?». Fortune. 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Heath, Nick (2018). «What is artificial general intelligence?». ZDNet. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Häggström, Olle (2016). Here be dragons: science, technology and the future of humanity. Oxford. pp. 103, 104. ISBN 9780191035395.

- ^ Gary Lea (2015). «The Struggle To Define What Artificial Intelligence Actually Means». Popular Science. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Legg, Shane; Hutter, Marcus (30 November 2007). «Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence». Minds and Machines. 17 (4): 391–444. arXiv:0712.3329. doi:10.1007/s11023-007-9079-x. S2CID 847021.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (First ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. «Chapter 4: The Kinetics of an Intelligence Explosion», footnote 9. ISBN 978-0-19-967811-2.

- ^ «Superintelligence: The Idea That Eats Smart People». idlewords.com. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Haier, Richard (2016). The Neuroscience of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Sternberg, Robert J.; Kaufman, Scott Barry, eds. (2011). The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108770422. ISBN 9780521739115. S2CID 241027150.

- Mackintosh, N. J. (2011). IQ and Human Intelligence (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958559-5.

- Flynn, James R. (2009). What Is Intelligence: Beyond the Flynn Effect (expanded paperback ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74147-7.

- Lay summary in: C Shalizi (27 April 2009). «What Is Intelligence? Beyond the Flynn Effect». University of Michigan (Review). Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

- Stanovich, Keith (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2.

- Lay summary in: Jamie Hale. «What Intelligence Tests Miss». Psych Central (Review). Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- Blakeslee, Sandra; Hawkins, Jeff (2004). On intelligence. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7456-7. OCLC 55510125.

- Bock, Gregory; Goode, Jamie; Webb, Kate, eds. (2000). The Nature of Intelligence. Novartis Foundation Symposium 233. Chichester: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0470870850. ISBN 978-0471494348.

- Lay summary in: William D. Casebeer (30 November 2001). «The Nature of Intelligence». Mental Help (Review). Archived from the original on 26 May 2013.

- Wolman, Benjamin B., ed. (1985). Handbook of Intelligence. consulting editors: Douglas K. Detterman, Alan S. Kaufman, Joseph D. Matarazzo. New York (NY): Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-89738-5.

- Terman, Lewis Madison; Merrill, Maude A. (1937). Measuring intelligence: A guide to the administration of the new revised Stanford-Binet tests of intelligence. Riverside textbooks in education. Boston (MA): Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 964301.

- Binet, Alfred; Simon, Th. (1916). The development of intelligence in children: The Binet-Simon Scale. Publications of the Training School at Vineland New Jersey Department of Research No. 11. E. S. Kite (Trans.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 1. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

External links[edit]

- Intelligence on In Our Time at the BBC

- History of Influences in the Development of Intelligence Theory and Testing Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Developed by Jonathan Plucker at Indiana University

- The Limits of Intelligence: The laws of physics may well prevent the human brain from evolving into an ever more powerful thinking machine by Douglas Fox in Scientific American, 14 June 2011.

- A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence

- | Causal Entropic Forces

Scholarly journals and societies

- Intelligence (journal homepage)

- International Society for Intelligence Research (homepage)

Human intelligence is difficult to define. And when it comes to understanding exactly what intelligence is and how it works, there are a number of ways to go about it.

So, why is it so difficult to define intelligence? What is intelligence? How can we measure it? Is there more than one way to be intelligent?

We’re going to look at human intelligence from a number of angles to see if we can broaden our understanding of what intelligence is and how it can be accurately measured.

How Do You Define Intelligence?

So, what is intelligence?

Intelligence can be defined as the ability to acquire and use new knowledge and skills.

But what sort of knowledge? And what sort of skills? It turns out these variables have a greater influence on the way we interpret intelligence than we might realize.

Wisdom Vs Intelligence: What’s The Difference?

Is wisdom the same thing as intelligence? The terms are often used interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing.

When it comes to the wisdom vs intelligence debate, it’s important to recognize that these two concepts are quite different from one another.

Intelligence is the ability to assimilate and utilize new information.

Wisdom, on the other hand, is the ability to use past experiences to make informed decisions about the future.

What Is Intelligence According to Psychology?

Psychology is the scientific study of the mind. So, what is intelligence according to the field of psychology?

Psychology defines intelligence in a number of different ways. And that’s because there are many competing doctrines in the field of psychology.

It’s helpful to think of psychology as the trunk of a tree. Each branch that sprouts from the trunk finds its roots in the same principles and foundations. But each branch takes a different path toward the sunlight.

The way you define human intelligence in psychology depends entirely on the branch of psychology you use to define it.

Generally speaking, psychology recognizes human intelligence as the ability to acquire and synthesize new information.

What is the basic intelligence?

One of the earliest theories of intelligence was proposed by English psychologist, Charles Spearman, back in 1904.

This early theory focused on a single form of intelligence. Generalized intelligence, or “g factor,” was defined as the ability to perform certain cognitive tasks related to math, verbal fluency, spatial visualization, and memory. And it’s from this theory that the very first IQ tests were born.

What Does IQ Mean?

IQ stands for intelligence quotient. It was first coined by German psychologist, William Stern, back in 1912.

Stern used intelligence quotients as a way to standardize the scores he analyzed from intelligence tests.

Believe it or not, the very first IQ test was actually designed by French psychologist, Albert Binet. We know it today as the famous Stanford-Binet Scale.

What is the IQ of an average person?

Can IQ tests accurately measure intelligence? It’s a tough question to answer because while IQ tests are limited, they are capable of measuring certain cognitive abilities, including fluid reasoning, spatial processing, and deductive reasoning.

The average score for most IQ tests is 100.

But it’s important to keep in mind that your IQ score may not stay the same over the course of your life. In fact, the average IQ score by age can differ quite substantially.

What is the highest IQ possible?

100 is the average score for most, but there’s quite a spread in terms of the lowest and highest recorded IQ scores.

What’s the highest IQ possible to attain on an IQ test? Well, when examining high IQ scores, it’s helpful to look at the scores of the great minds we’ve witnessed throughout history.

Most theorists estimate Einstein’s IQ to have been between 160-190 points. Einstein never actually took an IQ test, so the best we have is an informed guess!

Garry Kasparov’s IQ was a reported 135 points, based on a test he took in 1988.

Dr. Stephen Hawking was also said to have had an impressively high IQ, with a similar range to Einstein: 160 – 190 points. But, just like Einstein, Hawking never actually took an IQ test. He wasn’t a fan of standardized intelligence tests and didn’t believe IQ scores were an accurate representation of human intelligence.

What is the lowest IQ ever recorded?

So, what about the opposite end of the spectrum? What’s the lowest IQ ever recorded?

While it may be theoretically possible to score 0 on an IQ test, no one has actually ever attained this score.

Generally speaking, any score that dips below 70 points is considered to be below average. Unfortunately, those with scores below 70 often have some form of mental or cognitive impairment.

Will a High IQ Make You More Successful?

Ever heard the saying: to have a high IQ to be successful? Some use it in terms of grasping certain concepts or learning new skills.

But is a high IQ really necessary to be successful?

Absolutely not.

Just look at Stephen Hawking. He possessed one of the most powerful, influential minds to date. And he couldn’t be bothered to take an IQ test.

The fact of the matter is, IQ tests are an outdated measure of intelligence. And while they are capable of measuring certain abilities, they are very limited.

There are all sorts of genius tests and genius clubs (like Mensa International) that propagate the value of traditional intelligence testing. But the truth is, we’ve come a long way from Spearman’s theory of generalized intelligence.

It’s not how smart you are, but how you are smart.

— Jim Kwik, trainer of Minvalley’s Superbrain Quest

How Can I Make Myself Smarter?

The recent science says that through neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, we can grow older but we can actually grow better. We can grow new brain cells and new connections and do things that are extraordinary.

— Jim Kwik, trainer of Minvalley’s Superbrain Quest

Increasing your intelligence has everything to do with the way you choose to define intelligence.

Did you know that emerging theories in human intelligence suggest we actually possess nine different types of intelligence? It’s true! And it’s quite the far cry from Spearman’s theory of a single generalized intelligence.

If you want to learn how to get smarter, it’s really all about improving your cognitive abilities. Increasing your brain power is a worthy endeavor and there are plenty of ways to go about it.

Here are a few ways you can exercise your abilities and grow your brain:

- Adopt a beginner’s mind

- Try the F.A.S.T method

- Exercise regularly

- Meditate

- Try some brain teasers

- Play strategy-based board games

- Teach others what you’ve learned

- Try a new sport or hobby

Becoming smarter is all about challenging your brain to try new things. The more you explore, the more adaptive your brain will become!

Are you intelligent?

Before you start to search for old IQ test results, let’s talk. The definition of “intelligence,” how it’s measured, and what it actually means to be “intelligent” may actually come as a surprise. Even the most important theories regarding intelligence, including Gardener’s nine types of intelligence, has been disputed by the world’s big names in psychology.

Everyone has their own definition of intelligence, but what do psychologists say? How do they measure intelligence? The answer isn’t so simple. Let’s touch on the basics of what intelligence is, how it’s been defined in recent years, and where the theories of intelligence are moving.

The two definitions of intelligence are the root of the controversies regarding how to measure and identify intelligence. The first definition is: “Intelligence is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.” The other definition is more complex: “Intelligence is the collection of information of military or political value.”

The second definition infers that intelligence is a measure of potential success throughout a community. This use for intelligence is what led psychologists to develop the IQ test.

Can Intelligence Be Measured? IQ Tests And Intelligence

In the early 1900s, French psychologist Alfred Binet helped to developed the first type of intelligence quotient tests, or IQ tests. The French government wanted to use the test to determine which children were more likely to succeed in school and which children needed more help.

Binet’s original test measured the “mental age” of children based on the average age and skills of a group of students. He admitted that the test had limits and that a single number was not enough to accurately depict all of the factors that influence intelligence.

Still, the test was adapted to American schools and is still used to measure intelligence today. High IQ is still associated with overall job performance and life “success.” IQ can change over the span of a person’s lifetime. While it is very easy to decrease a person’s IQ, science is still looking for ways to “increase” a person’s IQ points.

Controversy with IQ Tests: Intelligence and Speed

Unfortunately, even through many revisions of the standard IQ tests, there are still flaws in the design of the test. Let’s just look at one for right now.

Intelligence has a lot to do with “speed.” If I give you a complex problem on an IQ test, you might need a few minutes to solve it or a month to solve it. In both cases, you have the ability to solve the problem, but the person who can solve the problem more quickly will end up with the higher IQ score.

But what if you have learned how to solve the test before? The IQ test does take in your actual age, but other factors (including your education) aren’t necessarily taken into account. Remember, in both cases, the person learned how to solve the problem eventually, and when asked to solve the problem again, they could probably increase their speed. Does the IQ test accurately show how often people have had to solve related problems before the IQ test was administered?

Fluid Vs. Crystallized Intelligence

These questions have led people to explore different types of intelligence. How can we recognize people who take a little longer to learn something, but still have the ability to do so? How do we categorize people that just need to pull on past experiences to solve problems and repeat learned facts?

One of the ways we make these distinctions is by identifying fluid vs. crystallized intelligence. The theory of these types of intelligence was developed by Raymond Cattell, a psychologist who is also known for his work in trait psychology.

He theorized that there are two types of intelligence: fluid and crystallized intelligence.

Fluid intelligence is the ability to gather, store, and organize facts. Crystallized intelligence is factual knowledge. People can gain crystallized intelligence as they memorize new facts and are exposed to more knowledge. Fluid intelligence, on the other hand, is the ability to learn – and it decreases with age. Both types of intelligence, however, give you the ability to succeed.

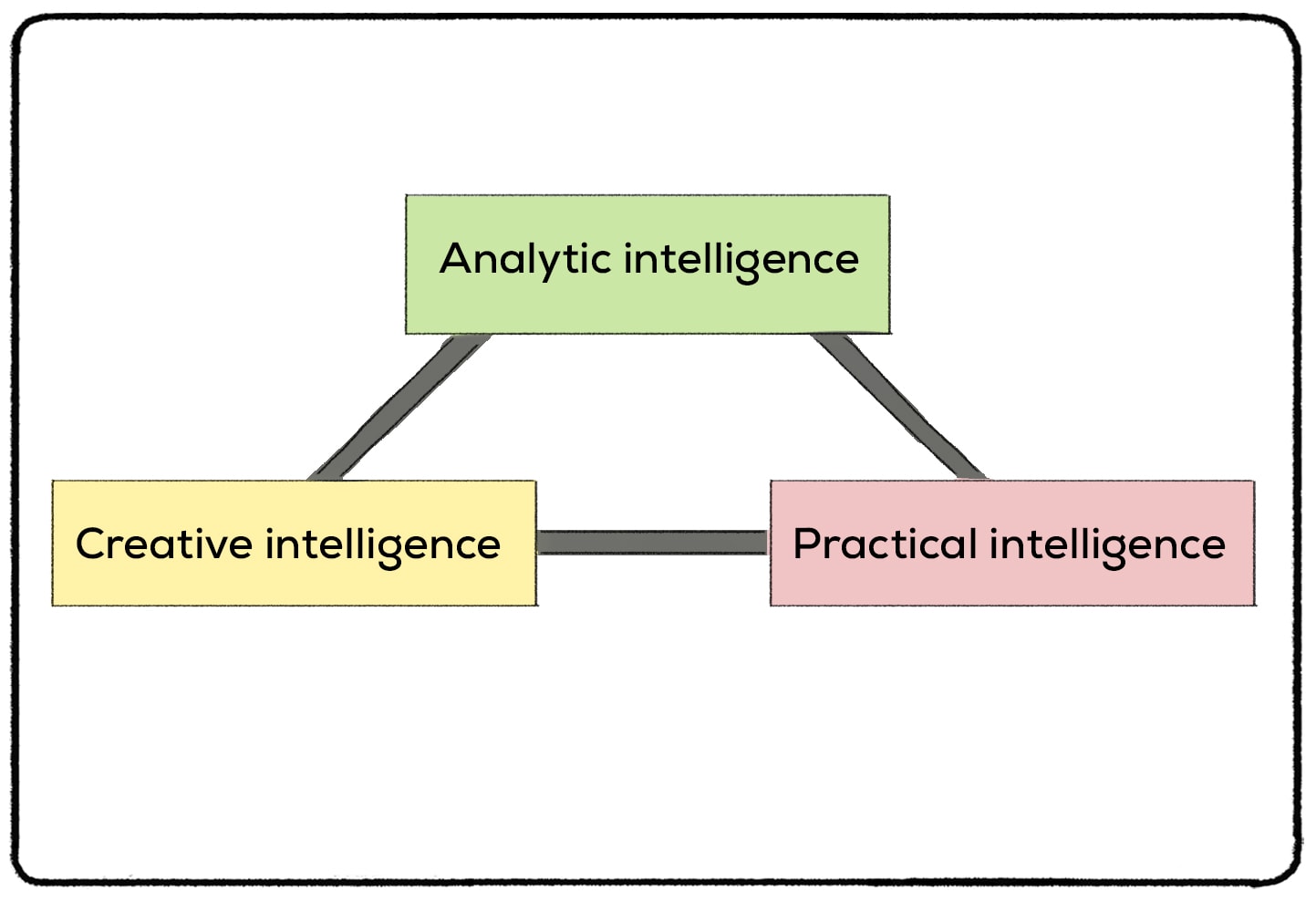

Practical Intelligence and the Triarchic Theory

Another popular way of categorizing intelligence is the Triarchic Theory, developed by Robert J. Sternberg. Rather than looking at the way you gain and store knowledge, the Triarchic Theory looks at different ways that people apply knowledge.

Fun facts about animals or the ability to solve a logic puzzle may not help you when you’re trying to read a map or network, but all of these skills can help you succeed in certain situations. That’s what the Triarchic Theory aims to recognize.

They separate intelligence into three categories.

Analytical Intelligence is the type of intelligence we have been discussing. It is the brain’s ability to interpret information and use that information to solve problems. This is the type of knowledge that is required to gain a high IQ score, but the Triarchic Theory argues that there is more to intelligence than just solving a math problem. A lot of people call this type of intelligence “book smarts.”

Practical intelligence is “an experience-based accumulation of skills and explicit knowledge as well as the ability to apply that knowledge to solve everyday problems.” This is the type of intelligence that you need to solve the problems of the world around you. In order to gain practical intelligence, you need to have knowledge of the area, culture, history, the list goes on and on.

Math won’t help you solve a dispute between two neighbors or settle a debate on how to solve the city’s traffic problems. These are both great examples of practical intelligence.

This type of intelligence is highly present in great leaders. In fact, Robert Sternberg said the definition of practical intelligence is to find the best fit between your personality strengths and the environment.

Creative Intelligence is the last type of intelligence in the Triarchic Theory. It describes the ability to adapt your knowledge and gather relevant knowledge that will help you adapt to new situations. While practical intelligence is often referred to as “street smarts,” I would argue that this type of intelligence is more suited to be called “street smarts.” If you are dropped in the middle of an unknown street in an unknown culture, you’re going to need some creative intelligence to get where you need to go and adapt to the new situation.

Does this cover all types of intelligence? Not according to the last theory we are going to cover. We’ll wrap this video up with information about the nine types of intelligence.

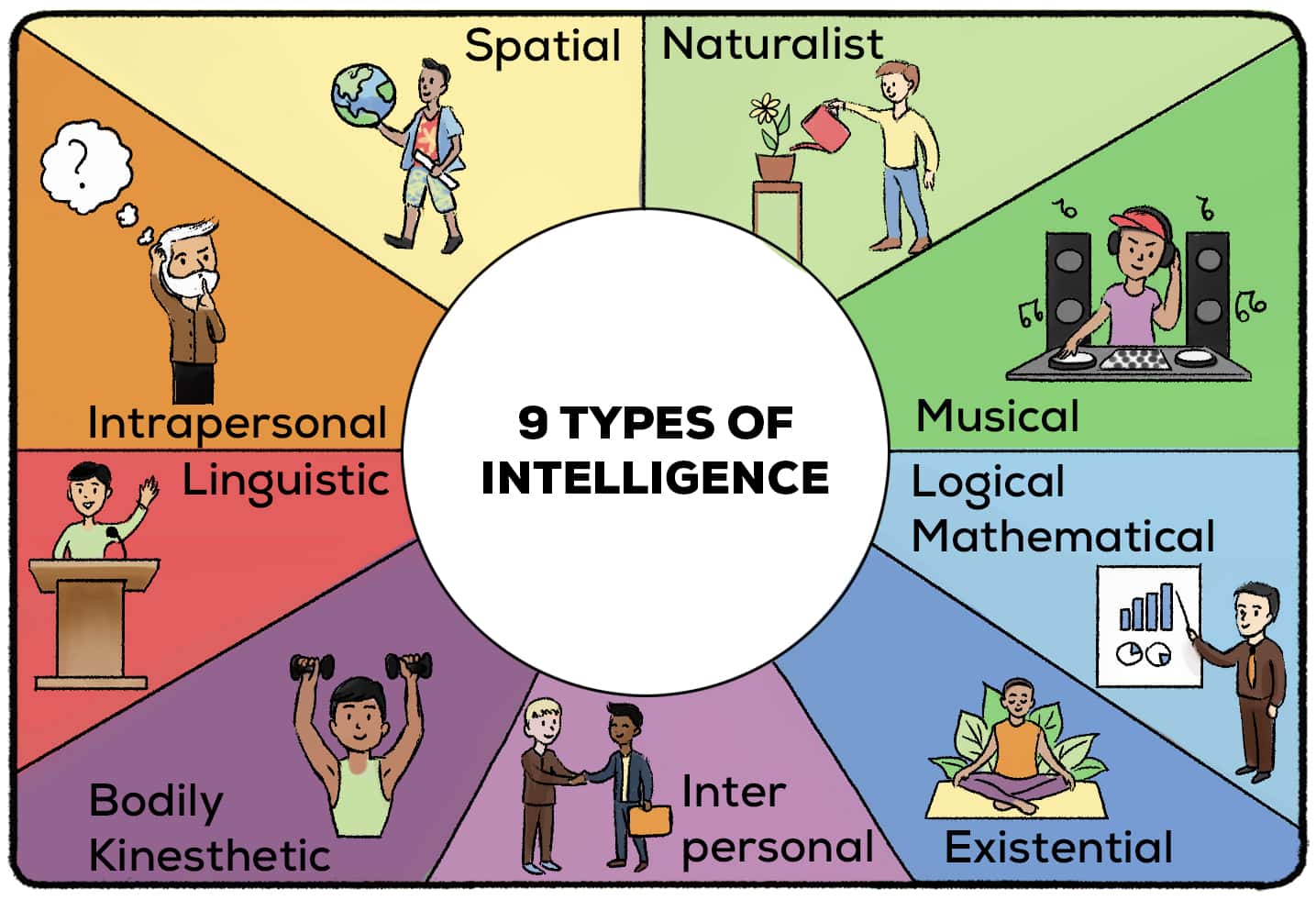

Gardener’s Nine Types of Intelligence

You probably thought this was going to be a video about the different types of intelligence: musical, kinesthetic, linguistic…right?

The “nine types of intelligence” describes a theory created by Howard Gardener. Howard Gardener is an American developmental psychologist who studied different types of intelligence throughout the second half of the 20th century. He believed that IQ tests and traditional ways of measuring intelligence only addressed linguistic and mathematical intelligence. There are many intelligent people who, while they may not excel on a math test or a reading assignment, display a deep understanding and knowledge in other areas.

He explained seven different types of intelligence in his 1983 book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Over the years, he’s added two other types of intelligence. While this theory is entirely separate from Kolb’s theories about different learning styles, we can connect the two and explore how people with different types of intelligence learn.

Gardener’s nine types of intelligence include:

- Musical-Rhythmic

- Visual-Spatial

- Linguistic

- Mathematical

- Interpersonal

- Intrapersonal

- Existential

- Naturalistic

- Body Kinesthetic

Controversy With the Nine Types of Intelligence

The nine types of intelligence rocked the world of educational psychology. In recent years, this theory has been disputed. Jordan Peterson, arguably one of the most famous psychologists in the world today, calls the nine types of intelligence theory “rubbish.” He argues that the the nine types of “intelligence” are just nine types of talents.

These critiques and arguments are still in development. It will be interesting to see where the world of educational psychology and measuring intelligence moves within the next few decades. Keep an eye out for new developments, and remember – even if you never scored high on an IQ test, there’s still a good chance that you hold some type of intelligence that will help you succeed.

Key Takeaways

- Defining and classifying intelligence is extremely complicated. Theories of intelligence range from having one general intelligence (g), to certain primary mental abilities, and to multiple category-specific intelligences.

- Following the creation of the Binet-Simon scale in the early 1900s, intelligence tests, now referred to as intelligence quotient (IQ) tests, are the most widely-known and used measure for determining an individual’s intelligence.

- Although these tests are generally reliable and valid tools, they do have their flaws as they lack cultural specificity and can evoke stereotype threat and self-fulfilling prophecies.

- IQ scores are typically normally distributed, meaning that 95% of the population has IQ scores between 70 and 130. However, there are some extreme examples of people with scores far exceeding 130 or far below 70.

What Is Intelligence?

It might seem useless to define such a simple word. After all, we have all heard this word hundreds of times and probably have a general understanding of its meaning. However, the concept of intelligence has been a widely debated topic among members of the psychology community for decades.

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: higher level abilities (such as abstract reasoning,

mental representation, problem solving, and decision

making), the ability to learn, emotional knowledge, creativity, and adaptation to meet

the demands of the environment effectively.

Psychologist Robert Sternberg defined intelligence as “the mental abilities necessary for adaptation to, as well as shaping and selection of, any environmental

context (1997, p. 1)

A Brief History of Intelligence

The study of human intelligence dates back to the late 1800s when Sir Francis Galton (the cousin of Charles Darwin) became one of the first people to study intelligence.

Galton was interested in the concept of a gifted individual, so he created a lab to measure reaction times and other physical characteristics to test his hypothesis that intelligence is a general mental ability that is a produce of biological evolution (hello, Darwin!).

Galton theorized that because quickness and other physical attributes were evolutionarily advantageous, they would also provide a good indication of general mental ability (Jensen, 1982).

Thus, Galton operationalized intelligence as reaction time.

Operationalization is an important process in research that involves defining an unmeasurable phenomenon (such as intelligence) in measurable terms (such as reaction time), allowing the concept to be studied empirically (Crowthre-Heyck, 2005).

Galton’s study of intelligence in the laboratory setting and his theorization of the heritability of intelligence paved the way for decades of future research and debate in this field.

Some researchers argue that intelligence is a general ability, whereas others make the assertion that intelligence comprises specific skills and talents. Psychologists contend that intelligence is genetic, or inherited, and others claim that it is largely influenced by the surrounding environment.

As a result, psychologists have developed several contrasting theories of intelligence as well as individual tests that attempt to measure this very concept.

Spearman’s General Intelligence (g)

General intelligence, also known as g factor, refers to a general mental ability

that, according to Spearman, underlies multiple specific skills, including verbal, spatial, numerical and mechanical.

Charles Spearman, an English psychologist, established the two-factor theory of intelligence back in 1904 (Spearman, 1904). To arrive at this theory, Spearman used a technique known as factor analysis.

Factor analysis is a procedure through which the correlation of related variables are evaluated to find an underlying factor that explains this correlation.

In the case of intelligence, Spearman noticed that those who did well in one area of intelligence tests (for example, mathematics), also did well in other areas (such as distinguishing pitch; Kalat, 2014).

In other words, there was a strong correlation between performing well in math and music, and Spearman then attributed this relationship to a central factor, that of general intelligence (g).

Spearman concluded that there is a single g-factor which represents an individual’s general intelligence across multiple abilities, and that a second factor, s, refers to an individual’s specific ability in one particular area (Spearman, as cited in Thomson, 1947).

Together, these two main factors compose Spearman’s two-factor theory.

Thurstone’s Primary Mental Abilities

Thurstone (1938) challenged the concept of a g-factor. After analyzing data from 56 different tests of mental abilities, he identified a number of primary mental abilities that comprise intelligence, as opposed to one general factor.

The seven primary mental abilities in Thurstone’s model are verbal comprehension, verbal fluency, number facility, spatial visualization, perceptual speed, memory, and inductive reasoning (Thurstone, as cited in Sternberg, 2003).

| Mental Ability | Description |

|---|---|

| Word Fluency | Ability to use words quickly and fluency in performing such tasks as rhyming, solving anagrams, and doing crossword puzzles. |

| Verbal Comprehension | Ability to understand the meaning of words, concepts, and ideas. |

| Numerical Ability | Ability to use numbers to quickly computer answers to problems. |

| Spatial Visualization | Ability to visualize and manipulate patters and forms in space. |

| Perceptual Speed | Ability to grasp perceptual details quickly and accurately and to determine similarities and differences between stimuli. |

| Memory | Ability to recall information such as lists or words, mathematical formulas, and definitions. |

| Inductive Reasoning | Ability to derive general rules and principles from presented information. |

Although Thurstone did not reject Spearman’s idea of general intelligence altogether, he instead theorized that intelligence consists of both general ability and a number of specific abilities, paving the way for future research that examined the different forms of intelligence.

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

Following the work of Thurstone, American psychologist Howard Gardner built off the idea that there are multiple forms of intelligence.

He proposed that there is no single intelligence, but rather distinct, independent multiple intelligences exist, each representing unique skills and talents relevant to a certain category.

Gardner (1983, 1987) initially proposed seven multiple intelligences : linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal, and he has since added naturalist intelligence.

Gardner holds that most activities (such as dancing) will involve a combination of these multiple intelligences (such as spatial and bodily-kinesthetic intelligences). He also suggests that these multiple intelligences can help us understand concepts beyond intelligence, such as creativity and leadership.

And although this theory has widely captured the attention of the psychology community and greater public, it does have its faults.

There have been few empirical studies that actually test this theory, and this theory does not account for other types of intelligence beyond the ones Gardner lists (Sternberg, 2003).

Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

Just two years later, in 1985, Robert Sternberg proposed a three-category theory of intelligence, integrating components that were lacking in Gardner’s theory. This theory is based on the definition of intelligence as the ability to achieve success based on your personal standards and your sociocultural context.

According to the triarchic theory, intelligence has three aspects: analytical, creative, and practical (Sternberg, 1985).

Analytical intelligence, also referred to as componential intelligence, refers to intelligence that is applied to analyze or evaluate problems and arrive at solutions. This is what a traditional IQ test measure.

Creative intelligence is the ability to go beyond what is given to create novel and interesting ideas. This type of intelligence involves imagination, innovation and problem-solving.

Practical intelligence is the ability that individuals use to solve problems faced in daily life, when a person finds the best fit between themselves and the demands of the environment.

Adapting to the demands environment involves either utilizing knowledge gained from experience to purposefully change oneself to suit the environment (adaptation), changing the environment to suit oneself (shaping), or finding a new environment in which to work (selection).

Other Types of Intelligence

After examining the popular competing theories of intelligence, it becomes clear that there are many different forms of this seemingly simple concept.

On one hand, Spearman claims that intelligence is generalizable across many different areas of life, and on the other hand, psychologists such as Thurstone, Gardener, and Sternberg hold that intelligence is like a tree with many different branches, each representing a specific form of intelligence.

To make matters even more interesting, let’s throw a few more types of intelligence into the mix!

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional Intelligence is the “ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior” (Salovey and Mayer, 1990).

Emotional intelligence is important in our everyday lives, seeing as we experience one emotion or another nearly every second of our lives. You may not associate emotions and intelligence with one another, but in reality, they are very related.

Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize the meanings of emotions and to reason and problem-solve on the basis of them (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999). The four key components of emotional Intelligence are (i) self-awareness, (ii) self-management, (iii) social awareness, and (iv) relationship management.

In other words, if you are high in emotional intelligence, you can accurately perceive emotions in yourself and others (such as reading facial expressions), use emotions to help facilitate thinking, understand the meaning behind your emotions (why are you feeling this way?), and know how to manage your emotions (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

Fluid vs. Crystallized Intelligence

Raymond Cattell (1963) first proposed the concepts of fluid and crystallized intelligence and further developed the theory with John Horn.

Fluid intelligence is the ability to problem solve in novel situations without referencing prior knowledge, but rather through the use of logic and abstract thinking. Fluid intelligence can be applied to any novel problem because no specific prior knowledge is required (Cattell, 1963). As you grow older fluid increases and then

starts to decrease in the late 20s.

Crystallized intelligence refers to the use of previously-acquired knowledge, such as specific facts learned in school or specific motor skills or muscle memory (Cattell, 1963). As you grow older and accumulate knowledge, crystallized intelligence increases.

The Cattell-Horn (1966) theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence suggests that intelligence is composed of a number of different abilities that interact and work together to produce overall individual intelligence

For example, if you are taking a hard math test, you rely on your crystallized intelligence to process the numbers and meaning of the questions, but you may use fluid intelligence to work through the novel problem and arrive at the correct solution. It is also possible that fluid intelligence can become crystallized intelligence.

The novel solutions you create when relying on fluid intelligence can, over time, develop into crystallized intelligence after they are incorporated into long-term memory.

This illustrates some of the ways in which different forms of intelligence overlap and interact with one another, revealing its dynamic nature.

Intelligence Testing

Binet-Simon Scale

During the early 1900s, the French government enlisted the help of psychologist Alfred Binet to understand which children were going to be slower learners and thus require more assistance in the classroom (Binet et al., 1912).

As a result, he and his colleague, Theodore Simon, began to develop a specific set of questions that focused on areas such as memory and problem-solving skills.

They tested these questions on groups of students aged three to twelve to help standardize the measure (Binet et al., 1912). Binet realized that some children were able to answer advanced questions that their older peers were able to answer.

As a result, he created the concept of a mental age, or how well an individual performs intellectually relative to the average performance at that age (Cherry, 2020).

Ultimately, Binet finalized the scale, known as the Binet-Simon scale, that became the basis for the intelligence tests still used today.

The Binet-Simon scale of 1905 comprised 30 items designed to measure judgment, comprehension, and reasoning which Binet deemed the key characteristics of intelligence.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale

When the Binet-Simon scale made its way over to the United States, Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman adapted the test for American students, and published the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale in 1916 (Cherry, 2020).

The Stanford-Binet Scale is a contemporary assessment which measures intelligence according to five features of cognitive ability,

including fluid reasoning, knowledge, quantitative reasoning, visual-spatial processing and working memory. Both verbal and nonverbal responses are measured.

This test used a single number, referred to as the intelligence quotient (IQ) to indicate an individual’s score.

The average score for the test is 100, and any score from 90 to 109 is considered to be in the average intelligence range. Scores from 110 to 119 are considered to be High Average. Superior scores range from 120 to 129 and anything over 130 is considered Very Superior.

To calculate IQ, the student’s mental age is divided by his or her actual (or chronological) age, and this result is multiplied by 100. If your mental age is equal to your chronological age, you will have an IQ of 100, or average. If, however, your mental age is, say, 12, but your chronological age is only 10, you will have an above-average IQ of 120.

WISC and WAIS

Just as theories of intelligence build off one another, intelligence tests do too. After Terman created Stanford-Binet test, American psychologist David Wechsler developed a new tool due to his dissatisfaction with the limitations of the Stanford-Binet test (Cherry, 2020).

Just like Thurstone, Gardner, and Sternberg, Wechsler believed that intelligence involved many different mental abilities and felt that the Stanford-Binet scale too closely reflected the idea of one general intelligence.

Because of this, Wechsler created the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) in 1955, with the most up-to-date version being the WAIS-IV (Cherry, 2020).

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), developed by David Wechsler, is an IQ test designed to measure intelligence and cognitive ability in children between the ages of 6 and 16. It is currently in its fourth edition (WISC-V) released in 2014 by Pearson.

Above Image: WISC-IV Sample Test Question

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) is an IQ test designed to measure cognitive ability in adults and older adolescents, including

verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory, and processing speed.

The latest version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) was standardized on 2,200 healthy people between the ages of 16 and 90 years (Brooks et al., 2011).

The standardization of a test involves giving it to a large number of people at different ages in order to compute the average score on the test at each age level

The overall IQ score combines the test takers’ performance in all four categories (Cherry, 2020). And rather than calculating this number based on mental and chronological age, the WAIS compares the individual’s score to the average score at that level, as calculated by the standardization process.

The Flynn Effect

It is important to regularly standardize an intelligence test because the overall level of intelligence in a population may change over time.

This phenomenon is known as the Flynn effect (named after its discoverer, New Zealand researcher James Flynn) which refers to the observation that scores on intelligence tests worldwide increase from decade to decade (Flynn, 1984).

Aptitude vs. Achievement Tests

Other tests, such as aptitude and achievement tests, are designed to measure intellectual capability. Achievement tests measure what content a student has already learned (such as a unit test in history or a final math exam), whereas an aptitude test measures a student’s potential or ability to learn (Anastasi, 1984).

Although this may sound similar to an IQ test, aptitude tests typically measure abilities in very specific areas.

Criticism of Intelligence Testing

Criticisms have ranged from the claim that IQ tests are biased in favor of white, middle-class people. Negative stereotypes about a person’s ethnicity, gender, or age may cause the person to suffer stereotype threat, a burden of doubt about his or her own abilities, which can create anxiety that result in lower scores.

Reliability and Construct Validity

Although you may be wondering if you take an intelligence test multiple times will you improve your score and whether these tests even measure intelligence in the first place, research provides reassurance that these tests are both very reliable and have high construct validity.

Reliability simply means that they are consistent over time. In other words, if you take a test at two different points in time, there will be very little change in performance or, in the case of intelligence tests, IQ score.

Although this isn’t a perfect science and your score might slightly fluctuate when taking the same test on different occasions or different tests at the same age, IQ tests demonstrate relatively high reliability (Tuma & Appelbaum, 1980).

Additionally, intelligence tests also reveal strong construct validity, meaning that they are, in fact, measuring intelligence rather than something else.

Researchers have spent hours on end developing, standardizing, and adapting these tests to best fit into the current times. But that is also not to say that these tests are completely flawless.

Research documents errors with the specific scoring of tests, and interpretation of the multiple scores (since typically an individual will receive an overall IQ score accompanied by several category-specific scores), and some studies question the actual validity, reliability, and utility for individual clinical use of these tests (Canivez, 2013).

Additionally, intelligence scores are created to reflect different theories of intelligence, so the interpretations may be heavily based on the theory upon which the test is based (Canivez, 2013).

Cultural Specificity

There are issues with intelligence tests beyond looking at them in a vacuum. These tests were created by western psychologists who created such tools to measure euro-centric values.

But it is important to recognize that the majority of the world’s population does not reside in Europe or North America, and as a result, the cultural specificity of these tests is crucial.

Different cultures hold different values and even have different perceptions of intelligence, so is it fair to have one universal marker of this increasingly complex concept?

For example, a 1992 study found that Kenyan parents defined intelligence as the ability to do without being told what needed to be done around the homestead (Harkness et al., 1992), and, given the American and European emphasis on speed, some Ugandans define intelligent people as being slow in thought and action (Wober, 1974).

Together, these examples illustrate the flexibility of defining intelligence, making it even more challenging to capture this concept in a single test, let alone a single number. And even within the U.S., do perceptions of intelligence differ?

An example is in San Jose, California, where Latino, Asian, and Anglo parents had varying definitions of intelligence. The teachers’ understanding of intelligence was more similar to that of the Asian and Anglo communities, and this similarity actually predicted the child’s performance in school (Okagaki & Sternberg, 1993).

That is, students whose families had more similar understandings of intelligence were doing better in the classroom.

Intelligence takes many forms, ranging from country to country and culture to culture. Although IQ tests might have high reliability and validity, understanding the role of culture is as, if not more, important in forming the bigger picture of an individual’s intelligence.

IQ tests may accurately measure academic intelligence, but more research must be done to discern whether they truly measure practical intelligence, or even just general intelligence in all cultures.

Social and Environmental Factors

Another important part of the puzzle to consider is the social and environmental context in which an individual lives and the IQ test-related biases that develop as a result.

These might help explain why some individuals have lower scores than others. For example, the threat of social exclusion can greatly decrease the expression of intelligence.

A 2002 study gave participants an IQ test and a personality inventory, and some were randomly chosen to receive feedback from the inventory indicating that they were “the sort of people who would end up alone in life” (Baumeister et al., 2002).

After a second test, those who were told they would be loveless and friendless in the future answered significantly fewer questions than they did on the earlier test.

And these findings can translate into the real world where not only the threat of social exclusion can decrease the expression of intelligence but also a perceived threat to physical safety.

In other words, a child’s poor academic performance can be attributed to the disadvantaged, potentially unsafe, communities in which they grow up.

Stereotype Threat

Stereotype threat is a phenomenon in which people feel at risk of conforming to stereotypes about their social group. Negative stereotypes can also create anxiety that result in lower scores.

In one study, Black and White college students were given part of the verbal section from the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), but in the stereotype threat condition, they told students the test diagnosed intellectual ability, thus potentially making the stereotype that Blacks are less intelligent than Whites salient.

The results of this study revealed that in the stereotype threat condition, Blacks performed worse than Whites, but in the no stereotype threat condition, Blacks and Whites performed equally well (Steele & Aronson, 1995).

And even just recording your race can also result in worsened performance. Stereotype threat is a real threat and can be detrimental to an individual’s performance on these tests.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Stereotype threat is closely related to the concept of a self-fulfilling prophecy in which an individual’s expectations about another person can result in the other person acting in ways that conform to that very expectation.

In one experiment, students in a California elementary school were given an IQ test after which their teachers were given the names of students who would become “intellectual bloomers” that year based on the results of the test (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968).

At the end of the study, the students were tested again with the same IQ test, and those who were labeled as “intellectual bloomers” had significant increases in their scores.

This illustrates that teachers may subconsciously behave in ways that encourage the success of certain students, thus influencing their achievement (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968), and provides another example of small variables that can play a role in an individual’s intelligence score and the development of their intelligence.

This is all to say that it is important to consider the less visible factors that play a role in determining someone’s intelligence. While an IQ score has many benefits in measuring intelligence, it is critical to consider that just because someone has a lower score, does not necessarily mean they are lower in intelligence.

There are many factors that can worsen performance on these tests, and the tests themselves might not even be accurately measuring the very concept they are intended to.

Extremes of Intelligence

IQ scores are generally normally distributed (Moore et al., 2013). That is, roughly 95% of the population has IQ scores between 70 and 130. But what about the other 5%?

Individuals who fall outside this range represent the extremes of intelligence.

Those who have an IQ above 130 are considered to be gifted (Lally & French, 2018), such as Christopher Langan, an American horse rancher, who has an IQ score around 200 (Gladwell, 2008).

Those individuals who have scores below 70 do so because of an intellectual disability, marked by substantial developmental delays, including motor, cognitive, and speech delays (De Light, 2012).

Some of the time, these disabilities are the product of genetic mutations.

Down syndrome, for example, resulting from extra genetic material from or a complete extra copy of the 21st chromosome, is a common genetic cause of an intellectual disability (Breslin, 2014). As such, many individuals with down syndrome have below average IQ scores (Breslin, 2014).

Savant syndrome is another example of an extreme of intelligence. Despite having significant mental disabilities, these individuals demonstrate certain abilities in some fields that are far above average, such as incredible memorization, rapid mathematical or calendar calculation ability, or advanced musical talent (Treffert, 2009).

The fact that these individuals who may be lacking in certain areas such as social interaction and communication make up for it in other remarkable areas, further illustrates the complexity of intelligence and what this concept means today, as well as how we must consider all individuals when determining how to perceive, measure, and recognize intelligence in our society.

Intelligence Today

Today, intelligence is generally understood as the ability to understand and adapt to the environment by using inherited abilities and learned knowledge.

Many new intelligence tests have arisen, such as the University of California Matrix Reasoning Task (Pahor et al., 2019), that can be taken online and in very little time, and new methods of scoring these tests have been developed too (Sansone et al., 2014).

Admission into university and graduate schools rely on specific aptitude and achievement tests, such as the SAT, ACT, and the LSAT – these tests have become a huge part of our lives.

Humans are incredibly intelligent beings and we rely on our intellectual abilities every day. Although intelligence can be defined and measured in countless ways, our overall intelligence as a species makes us incredibly unique and has allowed us to thrive for generations on end.

References

Anastasi, A. (1984). 7. Aptitude and Achievement Tests: The Curious Case of the Indestructible Strawperson.

Baumeister, R. F., Twenge, J. M., & Nuss, C. K. (2002). Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83 (4), 817.

Binet, A., Simon, T., & Simon, T. (1912). A method of measuring the development of the intelligence of young children. Chicago medical book Company.

Breslin, J., Spanò, G., Bootzin, R., Anand, P., Nadel, L., & Edgin, J. (2014). Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and cognition in Down syndrome. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 56 (7), 657-664.

Brooks, B. L., Holdnack, J. A., & Iverson, G. L. (2011). Advanced clinical interpretation of the WAIS-IV and WMS-IV: Prevalence of low scores varies by level of intelligence and years of education. Assessment, 18 (2), 156-167.

Canivez, G. L. (2013). Psychometric versus actuarial interpretation of intelligence and related aptitude batteries.

Cattell, R. B. (1963). Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of educational psychology, 54 (1), 1.

Cherry, K. (2020). Why Alfred Binet Developed IQ Testing for Students. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/history-of-intelligence-testing-2795581

Crowther-Heyck, H. (2005). Herbert A. Simon: The bounds of reason in modern America. JHU Press.

De Ligt, J., Willemsen, M. H., Van Bon, B. W., Kleefstra, T., Yntema, H. G., Kroes, T., … & del Rosario, M. (2012). Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. New England Journal of Medicine, 367 (20), 1921-1929.

Flynn, J. R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin, 95 (1), 29.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1987). The theory of multiple intelligence. Annals Of Dyslexia, 37, 19-35

Gignac, G. E., & Watkins, M. W. (2013). Bifactor modeling and the estimation of model-based reliability in the WAIS-IV. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48 (5), 639-662.

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown. Harkness, S., Super, C., & Keefer, C. (1992). Culture and ethnicity: In M. Levine, W. Carey & A. Crocker (Eds.), Developmental-behavioral pediatrics (pp. 103-108).

Horn, J. L., & Cattell, R. B. (1966). Refinement and test of the theory of fluid and crystallized general intelligences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 57, 253-270.

Jensen, A. R. (1982). Reaction time and psychometric g. In A model for intelligence (pp. 93-132). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Heidelber Kalat, J.W. (2014). Introduction to Psychology, 10th Edition. Cengage Learning.

Lally, M., & French, S. V. (2018). Introduction to Psychology. Canada: College of Lake County Foundation, 176-212.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267-298.

Moore, D. S., Notz, W. I, & Flinger, M. A. (2013). The basic practice of statistics (6th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Okagaki, L., & Sternberg, R. J. (1993). Parental beliefs and children’s school performance. Child Development, 64 (1), 36-56.

Pahor, A., Stavropoulos, T., Jaeggi, S. M., & Seitz, A. R. (2019). Validation of a matrix reasoning task for mobile devices. Behavior Research Methods, 51 (5), 2256-2267.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. The urban review, 3 (1), 16-20.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9 (3), 185-211.

Sansone, S. M., Schneider, A., Bickel, E., Berry-Kravis, E., Prescott, C., & Hessl, D. (2014). Improving IQ measurement in intellectual disabilities using true deviation from population norms. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 6 (1), 16.

Spearmen, C. (1904). General intelligence objectively determined and measured. American Journal of Psychology, 15, 107-197.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797-811.

Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. CUP Archive.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). The concept of intelligence and its role in lifelong learning and success. American psychologist, 52 (10), 1030.

Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Contemporary theories of intelligence. Handbook of psychology, 21-45.

Treffert, D. A. (2009). The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364 (1522), 1351-1357.

Thomson, G. (1947). Charles Spearman, 1863-1945.

Tuma, J. M., & Appelbaum, A. S. (1980). Reliability and practice effects of WISC-R IQ estimates in a normal population. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 40 (3), 671-678.

Wober, J. M. (1971). Towards an understanding of the Kiganda concept of intelligence. Social Psychology Section, Department of Sociology, Makerere University.

The

word “intelligence” is not a concept that is easy to define. Even

among professionals, there is no one definition that explains the

“attributes” of intelligence. That is because the word

“intelligence” is a noun – a part of speech used to signify

a thing or object which doesn’t have define characteristics.

Intelligence is highly abstract “thing” for which there are no

such definite attributes as long as short, red or green, light or

heavy. When intelligence is studied or measured, what actually is

observed is intelligent behavior or intelligent performance, not

intelligence per se.

If

we think in terms of intelligent behavior, rather than intelligence,

it is easier to identify and build a basis for defining the abstract

concept. You compare one behavior to a related behavior under the

same set of circumstances. In order to do this, you have to have a

basic storehouse of information.

The

process that you go through to make an observation and judgement of

intelligent behavior should in itself give you some insight into the

nature of intelligent behavior.

The

basis of intelligent behavior must be some kind of knowledge and

information in its broadest sense. This information may have been

acquired formally or informally.

The

impact of intelligence upon intelligent behavior begins with memory.

A factor related to remembering information is the application of

previous learning to current situation. This is the ability to

transfer or generalize. Some individuals have much more capacity for

transfer than others. Persons well-endowed with this ability are

usually found to be significantly more intelligent than those who do

not possess a high degree of this ability.

Other

facets of intelligence and intelligent behavior include speed in

arriving at answers and solutions and problem-solving ability. To