Initials are very important to understand as they’re used in a variety of important documents throughout one’s life. If you don’t know what initials are or how they work, you’ve come to the right place.

Initials are simply the first letter of a word. They are most commonly used with people’s names and should represent the first letter of the first name and the first letter of the second name. For example, John Smith would have JS initials.

You’ll come across initials plenty of times in English, especially anyone who has to fill in important documents. Documents often ask you to sign your initials directly after the place where you’ve signed your name and dated it.

Examples Of What Initials Are

We could teach you everything we know about initials, but it wouldn’t be much help if you don’t see them in action. We thought we’d show you some examples of how initials are used, as well as the names that those initials come from.

Remember, we must initial a name in its entirety. It’s no good only initially a first name or a last name. Both names must be included together. A typical initial is two letters long, though sometimes you can have more than that depending on the name.

- My name is Jack Preacher, and my initials are JP.

- If your name is John O’Sullivan, your initials can be JOS or JO, depending on your preference.

- I am called Steve Arnott, and my initials are SA.

- My initials are MO. My name is Matthew Oscar.

- Where do I find my initials if my name is Dean West? Is DW correct?

- You should initial all parts of your name. Patrick Stewart becomes PS.

- Matthew Bolton is initialed as MB.

- Make sure to initial your first name and last name, Roger Fox. That would make it RF.

- Mrs. Tonks’ initials are ST; I wonder what her first name could be. Sarah? Sam?

- My initials are AJ, and my first name is Alex. Can you guess my surname?

- The name is James Blond, though you can refer to me as JB.

- My initials are MS, and my name is Mary Sue.

We included as many names and examples as we could to show you when initials are used. Typically, we would know both the first name and the surname (second name) of the person if we’re initialing them, though we also only tend to give ourselves initials.

However, in the case of the teacher example (example 9), sometimes you will see an initial without knowing a full name. This leaves the name guessing to speculation, as an initial only gives away the first letter of a name and not the full name.

Are Initials Always First And Last Name?

Whenever you want to write initials, it always includes your first and last name. There are no other names that must be included for an initial to be authentic.

Most initials are two letters long because they are only a first and last name (AJ or BT). However, if the name has more than one word in it (usually indicated by a second capital letter), it’s possible to have three or more letters in the initial.

Let’s look at a few examples of what we mean:

- My name is AJ Prince. My initials are AJP.

Here, AJ already has an initial in his first name. Usually, the J in an initial like this means “Junior,” as their mother or father share the same name as them. However, AJ also has to include his last name initial to be correct, so he has three initials in his name.

- My name is John O’Peters. My initials are JOP.

Because the surname O’Peters uses two capital letters, it’s possible to see the initials of the full name be three letters in length. However, this is usually down to personal preference. Some people with “O’Peters” as a surname might only want to keep the O as the initial, while others want to keep the OP.

Is Initial Middle Name?

Whenever we’re using initials, we don’t typically include a middle name. There are a few exceptions, but most formal documents don’t require a middle name to be stated.

For example, if your name is “John Paul Goldberg,” your initials would be JG. You won’t need to include the P from Paul in your middle name. There is one exception to this rule, and that all comes down to personal preference again.

If you already initial your middle name when you introduce yourself (i.e., John F. Kennedy or Lyndon B. Johnson), then you can put those initials in your name. JFK and LBJ were both US Presidents who used their middle initial.

The tradition to use a middle initial when writing your initials is an American tradition, and it doesn’t typically happen anywhere else in the world. However, if you want to use your middle initial, there is nothing wrong with doing so – it’s just not common.

How Do I Write My Initials?

Let’s go over a quick guide to writing your initials. If you’ve been asked to do so, it can’t be much simpler than this!

- Write your full name.

- George Patrick Johnson.

- Remove your middle name if you don’t use the initial.

- George Johnson.

- Find the first letter of your first name and remove the rest.

- G Johnson

- Now find the first letter of your second name and remove the rest.

- G J

- Now put the two initials together. There doesn’t need to be a space between them.

- GJ

How Do I Write My Initials And Surname?

Sometimes, you might see initials used for only one name. If this is the case, you’ll always see the first name initialed, but the last name will be written out in full.

For example, a writer might sign their work “L. Bury.” If the writer’s first name is Lucian, then we can see how they’ve initialed it to show only “L.”

But why do writers do this?

Well, it’s not just writers that address themselves in this way. It’s actually common practice for a lot of people in the arts industry. For example, an artist might sign their work to say P. Picasso, or a playwright might write W. Shakespeare.

The reason this is done is as a sign of recognition. Most people will be familiar with the writer that they’re reading from or the artist they’re looking at the art of. If you’re famous enough in your own circle of art, then people won’t need to know your full name.

For that reason, it’s common to see the first name initialized when written. Your last name is more than enough to recognize you with when you’re well-established in your respected field. For newer writers and artists, it’s best to write your full name, so people know who you are before trying to remove some of your initials.

What To Write If A Form Asks For Your Initials

The most common place you might find something asking for your initials is on a form or a contract of some kind. You’ll typically see it look as follows:

Signature:Put signature here

Printed Name:DEAN EDWARDS

Initials:DE

Date:9/12/2021

You’ll almost always write your full name out and then include the initials afterward. It just helps to streamline the form-filling process and helps with the analysis of the form on the back-end.

How Do You Punctuate Initials?

You don’t always need to punctuate initials. It’s actually more common to leave your initials without any punctuation. However, some people like to show a difference between the two letters that separate their names with periods.

- DE

- D.E.

Both of these forms of initials are correctly punctuated. It’s up to you which form works best for you, but most people like to use it without periods because it saves time.

It’s worth quickly mentioning that if you follow the writer’s method above where the first name is initialed, but the last name is spelled out, you always want a period at the end of that.

- D. Edwards

This is because your spelling out the last name after the initial, so it’s good to separate the two with a period and a space.

Do You Put Periods Between Initials?

As we’ve already said, it’s up to you how you want to punctuate your initials. The most common form of punctuation uses periods between initials. If that looks good to you, then we recommend you use it!

Most people leave the periods out and only write the two letters when they initial their name.

Why Do Writers Use Initials?

Writers use initials when for two reasons.

They are either already well-established writers whose initials are recognizable to the people familiar with their work. They might also use them because they want to save time, and it’s quicker to write two letters than it is to write a full name.

How Do You Write Juniors Initials?

We briefly touched on this earlier, but if you share the same name with your child (or vise versa), you may want to know what their junior initials are.

- If you’re called Andy, and your son is called Andy, his name will be Andy Junior.

- Andy Junior is initialed to be AJ.

- If you include the surname after this, you simply add the next initial onto AJ.

- AJT works as a good initial. (If your last name begins with T).

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.

Initial letter

Updated on January 09, 2020

An initial is the first letter of each word in a proper name.

Guidelines for using initials in reports, research papers, and bibliographies (or reference lists) vary according to the academic discipline and appropriate style manual.

Etymology

From the Latin, «standing at the beginning»

Examples and Observations

Amy Einsohn: Most style manuals call for spacing between initials in a personal name: A. B. Cherry (not A.B. Cherry). There are no spaces, however, between personal initials that are not followed by periods (FDR, LBJ).

Allan M. Siegal and William G. Connolly: Although full first names with middle initials (if any) are preferred in most copy, two or more initials may be used if that is the preference of the person mentioned: L.P. Arniotis, with a thin space between initials.

Pam Peters: The practice of using initials to represent given names has been more common in Europe than in America or Australia. Various celebrated names are rarely given in any other form: C. P. E. Bach, T. S. Eliot, P. G. Wodehouse. In bibliographies and referencing systems (author-date-Vancouver), the use of initials is well established… Both the Chicago Manual of Style (2003) and Copy-editing (1992) use stops after each initial, as well as space, as shown in the names above. But in common usage, the space between initials is being whittled down (C.P.E. Bach, T.S. Eliot, P.G. Wodehouse) making the spacing exactly like that used in initialisms. . . . The practice of using an initial as well as a given name, as in J. Arthur Rank, Dwight D. Eisenhower is more widespread in the US than in the UK.

Kate Stone Lombardi: Take the League of Women Voters. The group was founded in 1920 during a convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, held only six months before the 19th Amendment was ratified, giving women the right to vote… [T]hose at the state level say that some League officers would like to follow the lead of the AARP, now more recognized for its initials than for the stodgier and sometimes misleading name, the American Association of Retired Persons. The AARP made the change partly because so many of its members, who are as young as 50, are still working. ‘We are working hard to put out the logo, LWV,’ said Martha Kennedy, state membership chairwoman.

Seth Stevenson: In 1985, the Entertainment and Sports Programming Network became just ESPN, with no reference to the original meaning. . . . TNN was once the Nashville Network, then became the National Network when it deep-sixed its hootenanny programming.

An initial letter is the first character of a sentence that is enlarged, positioned, and styled in a decorative or graphic way. It is commonly used to draw attention to a paragraph, chapter or section, article, ad copy – any important text in print and the web, as well as other digital media.

Initial letters can be both creative and functional. They can help spice up a layout by creating visual interest, thereby drawing attention to any important content entry point. They can also create emphasis, and establish or reinforce typographic hierarchy. All in all, the use of initial letters can be a dramatic and powerful way to add visual appeal and drama to an otherwise mediocre or unremarkable layout.

Initial letters can be either capitals or lowercase (thus my preferred term initial letters, and not initial caps as they are frequently referred to). They can be set in the same exact typeface as the neighboring text, a different weight or variant, or they can be set in a completely different typestyle. Highly contrasting weights and versions, as well as elaborate, decorative, calligraphic, or ornate typestyles in contrasting colors are often used and can work well.

Here are some of the most common initial letter styles:

Raised Initial

A raised initial, also referred to as a stick-up initial, is one whose baseline aligns with the first line of text, and whose body rises above it. It is much less complicated to execute than a dropped initial. When setting a raised initial that is the first letter of a word (as opposed to a single letter word such as A or I), make sure you space the rest of the word close enough to the initial to read as a word.

(left) A large raised initial in a striking color. (right) This ‘almost’ centered raised initial makes a dramatic statement. Both from Oprah magazine.

Dropped Initial

An initial that falls below the first line of text is referred to as a dropped initial. This is the most common initial treatment, and calls for precise placement and alignment on all edges to achieve a professional result. Dropped initials should optically align (as opposed to mechanically align) with the baseline of a line of type. When the height of the initial is intended to align with the first line of type, it should align with some element of that line, whether it be the cap height, an ascender, or even the x-height – whichever works best for each particular instance. For the most tasteful and pleasing appearance, go at least three lines deep.

(left) This classic drop cap treatment is counterpointed by the signature on the bottom right. Food and Wine magazine. (right) A condensed sans font and the addition of color make this drop initial stand out. Fortune magazine.

Overlapped and Contoured Initials

An initial can overlap the text in some manner, often partially sitting behind and sometimes rising above the text. The key to a successful execution of this approach is to keep the color of the initial light enough so that it doesn’t interfere with, or reduce the readability of the overlapped text. Text can also be contoured around an initial.

(left) This overlapped, or layered initial creates a subtle yet sophisticated look. Note the initial character is kept in the text to maintain its readability in this advertorial. (right) Text wrapped around an O makes for an elegant, eye-catching treatment. New England Home’s Connecticut magazine.

Boxed and Reversed Initials

There are countless approaches that can add visual interest and originality to initial characters. An initial can be placed within an outlined or colored box, or set in reverse and dropped out of a box of black or any color, or even a texture – pretty much anything you can think up!

Decorative Initial

Sometimes a very unusual, elaborate, or ornate initial can do a lot to enhance a design. Some fonts contain swash characters or other alternate letterforms that can be used as initial letters, while others contain decorative initials designed primarily for this purpose. In addition, some very interesting and unusual initials are available as .eps picture files. They are worth looking into, especially if your project is primarily text-based with few or no illustrations or photos, and could use a bit of livening up. Handwriting, graffiti, or even photographs showing real or organic letterforms can also render very interesting and original results.

(left) This oversized initial dropped out of a cyan box makes a strong graphic statement. Money magazine. (right) A decorative script initial sets just the right tone in this article about actress Sharon Stone. AARP The Magazine.

Lowercase Initial

Not all initials need to be capital letterforms! An interesting initial treatment can be achieved with the use of a lowercase character, often followed by a small cap text lead-in. This approach can render a distinctive look suitable for some designs.

Initial Word or Phrase

Try setting the first word or short phrase with a drop initial approach. The ability to actually read the initial treatment can draw the reader in with more information than just one character.

Initial Symbol

Sometimes the best initial letter is not actually a letter, but a symbol or a graphic. This technique can become one that is repeated throughout a magazine, brochure, web site, or any instance benefiting from a reinforced theme or branding.

(left) An initial letter can be replaced by a symbol. (right) This illustrated initial sits midway between two paragraphs. The Advocate and The New York Times Magazine.

A few things to keep in mind when using initial letters:

- Proper alignment is key to well-executed initial letters.

- Don’t repeat the letter you use as the initial cap in the text unless its size, style, and position make it difficult for the eye to connect it with the rest of the word.

- Avoid the use of too many initial letters in one layout. One per length of copy or long section is enough.

Initial letter treatments are not limited to the above styles: use your imagination, experiment with different approaches, and have fun with it – just keep them tasteful, readable, and appropriate to the content and the rest of the design.

(left) A chunky drop cap signals the beginning of this text-heavy editorial spread from Rolling Stone magazine. (right) This initial combines two styles: dropped and raised. Money magazine.

(upper left) An illustrated graphic can be used instead of an actual character for an initial treatment. Oprah magazine. (lower left) The addition of a coffee bean to this dropped initial ties it in to the headline as well as the content in this advertorial. (right) A raised cap becomes an illustration in this article from Oprah magazine.

*Check out some more creative uses of initial letters in this article about U&lc magazine.

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,

coldly,

etc.

Borrowed

affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary.

We can recognize words of Latin and French origin by certain suffixes

or

prefixes;

e. g. Latin

affixes:

-ion,

-tion, -ate,

-ute

,

-ct,

-d(e), dis-, -able, -ate,

-ant,

—

ent,

-or, -al, -ar in

such words as opinion,

union, relation, revolution, appreciate,

congratulate,

attribute, contribute, , act, collect, applaud, divide, disable,

disagree,

detestable,

curable, accurate, desperate, arrogant, constant, absent, convenient,

major,

minor, cordial, familiar;

French

affixes –ance,

—ewe,

-ment, -age, -ess, -ous,

en-

in

such words as arrogance,

intelligence, appointment, development, courage,

marriage,

tigress, actress, curious, dangerous, enable, enslaver.

Affixation

includes a) prefixation

–

derivation of words by adding a prefix to

full

words and b) suffixation

–

derivation of words by adding suffixes to bound

stems.

Prefixes

and suffixes have their own valency, that is they may be added not to

any

stem at random, but only to a particular type of stems:

84

Prefix

un-

is

prefixed to adjectives (as: unequal,

unhealthy), or

to adjectives

derived

from verb stems and the suffix -able

(as:

unachievable,

unadvisable), or

to

participial

adjectives (as: unbecoming,

unending, unstressed, unbound); the

suffix —

er

is

added to verbal stems (as: worker,

singer, or

cutter,

lighter), and

to substantive

stems

(as: glover,

needler); the

suffix -able

is

usually tacked on to verb stems (as:

eatable,

acceptable); the

suffix -ity

in

its turn is usually added to adjective stems

with

a passive meaning (as: saleability,

workability), but

the suffix —ness

is

tacked on

to

other adjectives, having the suffix -able

(as:

agreeableness.

profitableness).

Prefixes

and suffixes are semantically distinctive, they have their own

meaning,

while the root morpheme forms the semantic centre of a word. Affixes

play

a

dependent role in the meaning of the word. Suffixes have a

grammatical meaning,

they

indicate or derive a certain part of speech, hence we distinguish:

noun-forming

suffixes,

adjective-forming suffixes, verb-forming suffixes and adverb-forming

suffixes.

Prefixes change or concretize the meaning of the word, as: to

overdo (to

do

too

much),

to underdo (to

do less than one can or is proper),

to outdo (to

do more or

better

than),

to undo (to

unfasten, loosen, destroy the result, ruin),

to misdo (to

do

wrongly

or unproperly).

A

suffix indicates to what semantic group the word belongs. The suffix

-er

shows

that the word is a noun bearing the meaning of a doer of an action,

and the

action

is denoted by the root morpheme or morphemes, as: writer,

sleeper, dancer,

wood-pecker,

bomb-thrower, the

suffix -ion/-tion,

indicates

that it is a noun

signifying

an action or the result of an action, as: translation

‘a

rendering from one

language

into another’ (an

act, process) and

translation

‘the

product of such

rendering’;

nouns with the suffix -ism

signify

a system, doctrine, theory, adherence to

a

system, as: communism,

realism; coinages

from the stem of proper names are

common,.

as Darwinism.

Affixes

can also be classified into productive

and

non-productive

types.

By

productive

affixes we

mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in a

particular

period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes

is to look for them among neologisms

and

so-called nonce-words,

i.e.

words

coined

and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually

formed on the

level

of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive

patterns in

word-building.

When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable

thriller, we

will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in

dictionaries,

for it is a nonce-word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English

and

is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming

borrowed suffix –

able

and

the native prefix un-,

e.g.: Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish,

dyspeptic-lookingish

cove with an eye like a haddock.(From

Right-Ho, Jeeves by P.G.

Wodehouse)

The

adjectives thinnish

and

baldish

bring

to mind dozens of other adjectives

made

with the same suffix: oldish,

youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish,

yellowish,

etc. But

dyspeptic-lookingish

is

the author’s creation aimed at a humorous

effect,

and, at the same time, providing beyond doubt that the suffix –ish

is

a live and

active

one.

85

The

same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: “I

don’t like

Sunday

evenings: I feel so Mondayish”. (Mondayish is

certainly a nonce-word.)

One

should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency

of

occurrence

(use). There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which,

nevertheless,

are no longer used in word-derivation (e.g. the adjective-forming

native

suffixes

–ful,

-ly; the

adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin –ant,

-ent, -al which

are

quite frequent).

Some

Productive Affixes

Some

Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming

suffixes

-th,

-hood

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—ly,

-some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming

suffix -en

Compound

words are

words derived from two or more stems. It is a very old

word-formation

type and goes back to Old English. In Modern English compounds

are

coined by joining one stem to another by mere juxtaposition, as

raincoat,

keyhole,

pickpocket,

red-hot, writing-table. Each

component of a compound coincides

with

the word. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives.

Compound

verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion

(as,

to

weekend) and

of back-formation (as, to

stagemanage).

From

the point of view of word-structure compounds consist of free stems

and

may

be of different structure: noun stems + noun stem (raincoat);

adjective

stem +

noun

stem (bluebell);

adjective

stem + adjective stem (dark-blue);

gerundial

stem +

noun

stem (writing-table);

verb

stem + post-positive stem (make-up);

adverb

stem +

adjective

stem (out-right);

two

noun stems connected by a preposition (man-of-war)

and

others. There are compounds that have a connecting vowel (as,

speedometer,

handicraft),

but

it is not characteristic of English compounds.

Compounds

may be idiomatic

and

non-idiomatic.

In idiomatic compounds the

meaning

of each component is either lost or weakened, as buttercup

(лютик),

chatter-box

(болтун).

These

are entirely

demotivated compounds. There

are also motivated

compounds,

as lifeboat

(спасательная

лодка). In non-idiomatic compounds the

Noun-forming

suffixes

—er,

-ing,

—ness,

-ism (materialism),

-ist

(impressionist),

-ance

Adjective-forming

suffixes

—y,

-ish, -ed (learned),

—able,

—less

Adverb-forming

suffix

—ly

Verb-forming

suffixes

—ize/-ise

(realize),

—ate

Prefixes

un-

(unhappy),re-

(reconstruct),

dis-

(disappoint)

86

meaning

of each component is retained, as apple-tree,

bedroom, sunlight. There

are

also

many border-line cases.

The

components of compounds may have different semantic relations; from

this

point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric

and

exocentric

compounds.

In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found

within

the compound and the first element determines the other, as

film-star,

bedroom,

writing-table.

In

exocentric compounds there is no semantic centre, as

scarecrow.

In

Modern English, however, linguists find it difficult to give criteria

for

compound

nouns; it is still a question of hot dispute. The following criteria

may be

offered.

A compound noun is characterized by a) one word or hyphenated

spelling, b)

one

stress, and by c) semantic integrity. These are the so-called

“classical

compounds”.

It

is possible that a compound has only two of these criteria, for

instance, the

compound

words headache,

railway have

one stress and hyphenated or one-word

spelling,

but do not present a semantic unity, whereas the compounds

motor-bike,

clasp-knife

have

hyphenated spelling and idiomatic meaning, but two even stresses

(‘motor-‘bike,

‘clasp-‘knife).

The word apple-tree

is

also a compound; it is spelt either

as

one word or is hyphenated, has one stress (‘apple-tree),

but it is not idiomatic. The

difficulty

of defining a compound lies in spelling which might be misleading, as

there

are

no hard and fast rules of spelling the compounds: three ways of

spelling are

possible:

(‘dockyard,

‘dock yard and

dock-yard).

The

same holds true for the stress

that

may differ from one reference-book to another.

Since

compounds may have two stresses and the stems may be written

separately,

it is difficult to draw the line between compounds proper and nominal

word-combinations

or syntactical combinations. In a combination of words each

element

is stressed and written separately. Compare the attributive

combination

‘black

‘board, a

board which is black (each element has its own meaning; the first

element

modifies the second) and the compound ‘blackboard’,

a

board or a sheet of

slate

used in schools for teaching purposes (the word has one stress and

presents a

semantic

unit). But it is not always easy as that to draw a distinction, as

there are

word-combinations

that may present a semantic unity, take for instance: green

room

(a

room in a theatre for actors and actresses).

Compound

derivatives are

words, usually nouns and adjectives, consisting of

a

compound stem and a suffix, the commonest type being such nouns as:

firstnighter,

type-writer,

bed-sitter, week-ender, house-keeping, well-wisher, threewheeler,

old-timer,

and

the adjectives: blue-eyed,

blond-haired, four-storied, mildhearted,

high-heeled.

The

structure of these nouns is the following: a compound stem

+

the suffix -er,

or

the suffix -ing.

Adjectives

have the structure: a compound stem, containing an adjective (noun,

numeral)

stem and a noun stem + the suffix -ed.

In

Modern English it is an extremely

productive

type of adjectives, e.g.: big-eyed,

long-legged, golden-haired.

In

Modern English it is common practice to distinguish also

semi-suffixes, that

is

word-formative elements that correspond to full words as to their

lexical meaning

and

spelling, as -man,

-proof, -like: seaman, railroadman, waterproof, kiss-proof,

ladylike,

businesslike. The

pronunciation may be the same (cp. proof

[pru:f]

and

87

waterproof

[‘wL:tq

pru:f],

or differ, as is the case with the morpheme -man

(cp.

man

[mxn]

and seaman

[‘si:mqn].

The

commonest is the semi-suffix -man

which

has a more general meaning —

‘a

person of trade or profession or carrying on some work’, as: airman,

radioman,

torpedoman,

postman, cameramen, chairman and

others. Many of them have

synonyms

of a different word structure, as seaman

— sailor, airman — flyer,

workman

— worker; if

not a man but a woman

of

the trade or profession, or a person

carrying

on some work is denoted by the word, the second element is woman,

as

chairwoman,

air-craftwoman, congresswoman, workwoman, airwoman.

Conversion

is

a very productive way of forming new words in English, chiefly

verbs

and not so often — nouns. This type of word formation presents one

of the

characteristic

features of Modern English. By conversion we mean derivation of a

new

word from the stem of a different part of speech without the addition

of any

formatives.

As a result the two words are homonymous, having the same

morphological

structure and belonging to different parts of speech.

Verbs

may be derived from the stem of almost any part of speech, but the

commonest

is the derivation from noun stems as: (a)

tube — (to) tube; (a) doctor —

(to)

doctor, (a) face—(to) face; (a) waltz—(to) waltz; (a) star—(to)

star; from

compound

noun stems as: (a)

buttonhole — (to) buttonhole; week-end — (to) weekend.

Derivations

from the stems of other parts of speech are less common: wrong—

(to)

wrong; up — (to) up; down — (to) down; encore — (to) encore.

Nouns

are

usually

derived from verb stems and may be instanced by such nouns as: (to)

make—

a

make; (to) cut—(a) cut; to bite — (a) bite, (to) drive — (a)

drive; to smoke — (a)

smoke;

(to) walk — (a) walk. Such

formations frequently make part of verb — noun

combinations

as: to

take a walk, to have a smoke, to have a drink, to take a drive, to

take

a bite, to give a smile and

others.

Nouns

may be also derived from verb-postpositive phrases. Such formations

are

very common in Modern English, as for instance: (to)

make up — (a) make-up;

(to)

call up — (a) call-up; (to) pull over — (a) pullover.

New

formations by conversion from simple or root stems are quite usual;

derivatives

from suffixed stems are rare. No verbal derivation from prefixed

stems is

found.

The

derived word and the deriving word are connected semantically. The

semantic

relations between the derived and the deriving word are varied and

sometimes

complicated. To mention only some of them: a) the verb signifies the

act

accomplished

by or by means of the thing denoted by the noun, as: to

finger means

‘to

touch with the finger, turn about in fingers’; to

hand means

‘to give or help with

the

hand, to deliver, transfer by hand’; b) the verb may have the meaning

‘to act as the

person

denoted by the noun does’, as: to

dog means

‘to follow closely’, to

cook — ‘to

prepare

food for the table, to do the work of a cook’; c) the derived verbs

may have

the

meaning ‘to go by’ or ‘to travel by the thing denoted by the noun’,

as, to

train

means

‘to go by train’, to

bus — ‘to

go by bus’, to

tube — ‘to

travel by tube’; d) ‘to

spend,

pass the time denoted by the noun’, as, to

winter ‘to pass

the winter’, to

weekend

— ‘to

spend the week-end’.

88

Derived

nouns denote: a) the act, as a

knock, a hiss, a smoke; or

b) the result of

an

action, as a

cut, a find, a call, a sip, a run.

A

characteristic feature of Modern English is the growing frequency of

new

formations

by conversion, especially among verbs.

Note.

A grammatical homonymy of two words of different parts of speech —

a

verb

and a noun, however, does not necessarily indicate conversion. It may

be the

result

of the loss of endings as well. For instance, if we take the

homonymic pair love

— to

love and

trace it back, we see that the noun love

comes

from Old English lufu,

whereas

the verb to

love—from

Old English lufian,

and

the noun answer

is

traced

back

to the Old English andswaru,

but

the verb to

answer to

Old English

andswarian;

so

that it is the loss of endings that gave rise to homonymy. In the

pair

bus

— (to) bus, weekend — (to) weekend homonymy

is the result of derivation by

conversion.

Shortenings

(abbreviations)

are words produced either by means of clipping

full

word or by shortening word combinations, but having the meaning of

the full

word

or combination. A distinction is to be observed between graphical

and

lexical

shortenings;

graphical abbreviations are signs or symbols that stand for the full

words

or combination of words only in written speech. The commonest form is

an

initial

letter or letters that stand for a word or combination of words. But

to prevent

ambiguity

one or two other letters may be added. For instance: p.

(page),

s.

(see),

b.

b.

(ball-bearing).

Mr

(mister),

Mrs

(missis),

MS

(manuscript),

fig.

(figure). In oral

speech

graphical abbreviations have the pronunciation of full words. To

indicate a

plural

or a superlative letters are often doubled, as: pp.

(pages). It is common practice

in

English to use graphical abbreviations of Latin words, and word

combinations, as:

e.

g. (exampli

gratia), etc.

(et cetera), i.

e. (id

est). In oral speech they are replaced by

their

English equivalents, ‘for

example’,

‘and

so on’,

‘namely‘,

‘that

is’,

‘respectively’.

Graphical

abbreviations are not words but signs or symbols that stand for the

corresponding

words. As for lexical

shortenings,

two main types of lexical

shortenings

may be distinguished: 1) abbreviations

or

clipped

words (clippings)

and

2) initial

words (initialisms).

Abbreviation

or

clipping

is

the result of reduction of a word to one of its

parts:

the meaning of the abbreviated word is that of the full word. There

are different

types

of clipping: 1) back-clipping—the

final part of the word is clipped, as: doc

—

from

doctor,

lab — from

laboratory,

mag — from

magazine,

math — from

mathematics,

prefab —

from prefabricated;

2) fore-clipping

—

the first part of the

word

is clipped as: plane

— from

aeroplane,

phone — from

telephone,

drome —

from

aerodrome.

Fore-clippings

are less numerous in Modern English; 3) the

fore

and

the back parts of the word are clipped and the middle of the word is

retained,

as: tec

— from

detective,

flu — from

influenza.

Words

of this type are few

in

Modern English. Back-clippings are most numerous in Modern English

and are

characterized

by the growing frequency. The original may be a simple word (as,

grad—from

graduate),

a

derivative (as, prep—from

preparation),

a

compound, (as,

foots

— from

footlights,

tails — from

tailcoat),

a

combination of words (as pub —

from

public

house, medico — from

medical

student). As

a result of clipping usually

nouns

are produced, as pram

— from

perambulator,

varsity — for

university.

In

some

89

rare

cases adjectives are abbreviated (as, imposs

—from

impossible,

pi — from

pious),

but

these are infrequent. Abbreviations or clippings are words of one

syllable

or

of two syllables, the final sound being a consonant or a vowel

(represented by the

letter

o), as, trig

(for

trigonometry),

Jap (for

Japanese),

demob (for

demobilized),

lino

(for

linoleum),

mo (for

moment).

Abbreviations

are made regardless of whether the

remaining

syllable bore the stress in the full word or not (cp. doc

from

doctor,

ad

from

advertisement).

The

pronunciation of abbreviations usually coincides with the

corresponding

syllable in the full word, if the syllable is stressed: as, doc

[‘dOk]

from

doctor

[‘dOktq];

if it is an unstressed syllable in the full word the pronunciation

differs,

as the abbreviation has a full pronunciation: as, ad

[xd],

but advertisement

[qd’vq:tismqnt].

There may be some differences in spelling connected with the

pronunciation

or with the rules of English orthoepy, as mike

— from

microphone,

bike

— from

bicycle,

phiz —

from physiognomy,

lube — from

lubrication.

The

plural

form

of the full word or combinations of words is retained in the

abbreviated word,

as,

pants

— from

pantaloons,

digs — from

diggings.

Abbreviations

do not differ from full words in functioning; they take the plural

ending

and that of the possessive case and make any part of a sentence.

New

words may be derived from the stems of abbreviated words by

conversion

(as

to

demob, to taxi, to perm) or

by affixation, chiefly by adding the suffix —y,

-ie,

deriving

diminutives and petnames (as, hanky

— from

handkerchief,

nighty (nightie)

— from

nightgown,

unkie — from

uncle,

baccy — from

tobacco,

aussie — from

Australians,

granny (ie)

— from grandmother).

In

this way adjectives also may be

derived

(as: comfy

— from

comfortable,

mizzy — from

miserable).

Adjectives

may be

derived

also by adding the suffix -ee,

as:

Portugee

— for

Portuguese,

Chinee — for

Chinese.

Abbreviations

do not always coincide in meaning with the original word, for

instance:

doc

and

doctor

have

the meaning ‘one who practises medicine’, but doctor

is

also

‘the highest degree given by a university to a scholar or scientist

and ‘a person

who

has received such a degree’ whereas doc

is

not used in these meanings. Among

abbreviations

there are homonyms, so that one and the same sound and graphical

complex

may represent different words, as vac

(vacation), vac (vacuum cleaner);

prep

(preparation), prep (preparatory school). Abbreviations

usually have synonyms

in

literary English, the latter being the corresponding full words. But

they are not

interchangeable,

as they are words of different styles of speech. Abbreviations are

highly

colloquial; in most cases they belong to slang. The moment the longer

word

disappears

from the language, the abbreviation loses its colloquial or slangy

character

and

becomes a literary word, for instance, the word taxi

is

the abbreviation of the

taxicab

which,

in its turn, goes back to taximeter

cab; both

words went out of use,

and

the word taxi

lost

its stylistic colouring.

Initial

abbreviations (initialisms)

are words — nouns — produced by

shortening

nominal combinations; each component of the nominal combination is

shortened

up to the initial letter and the initial letters of all the words of

the

combination

make a word, as: YCL — Young

Communist League, MP

—

Member

of Parliament. Initial

words are distinguished by their spelling in capital

letters

(often separated by full stops) and by their pronunciation — each

letter gets

90

its

full alphabetic pronunciation and a full stress, thus making a new

word as R.

A.

F. [‘a:r’ei’ef] — Royal

Air Force; TUC.

[‘ti:’ju:’si:] — Trades

Union Congress.

Some

of initial words may be pronounced in accordance with the’ rules of

orthoepy,

as N. A. T. O. [‘neitou], U. N. O. [‘ju:nou], with the stress on the

first

syllable.

The

meaning of the initial word is that of the nominal combination. In

speech

initial words function like nouns; they take the plural suffix, as

MPs, and

the

suffix of the possessive case, as MP’s, POW’s.

In

Modern English the commonest practice is to use a full combination

either

in

the heading or in the text and then quote this combination by giving

the first initial

of

each word. For instance, «Jack Bruce is giving UCS concert»

(the heading). «Jack

Bruce,

one of Britain’s leading rock-jazz musicians, will give a benefit

concert in

London

next week to raise money for the Upper Clyde shop stewards’ campaign»

(Morning

Star).

New

words may be derived from initial words by means of adding affixes,

as

YCL-er,

ex-PM, ex-POW; MP’ess, or adding the semi-suffix —man,

as

GI-man.

As

soon

as the corresponding combination goes out of use the initial word

takes its place

and

becomes fully established in the language and its spelling is in

small letters, as

radar

[‘reidq]

— radio detecting and ranging, laser

[‘leizq]

— light amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation; maser

[‘meizq]

— microwave amplification by

stimulated

emission of radiation. There are also semi-shortenings, as, A-bomb

(atom

bomb),

H-bomber

(hydrogen

bomber), U-boat

(Untersee

boat) — German submarine.

The

first component of the nominal combination is shortened up to the

initial letter,

the

other component (or components) being full words.

4.7.

ENGLISH PHRASEOLOGY: STRUCTURAL AND SEMANTIC

PECULIARITIES

OF PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS, THEIR CLASSIFICATION

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

Main approaches to the definition of a phraseological unit in

linguistics.

2.

Different classifications of phraseological units.

3.

Grammatical and lexical modifications of phraseological units in

speech.

In

linguistics there are two main theoretical schools treating the

problems of

English

phraseology — that of N.N.Amosova and that of A. V. Kunin. We shall

not

dwell

upon these theories in detail, but we shall try to give the guiding

principles of

each

of the authors. According to the theory of N.N. Amosova. A

phraseological unit

is

a unit of constant context. It is a stable combination of words in

which either one of

the

components has a phraseologically bound meaning — a phraseme: white

lie –

невинная

ложь, husband

tea —

жидкий чай), or the meaning of each component is

weakened,

or entirely lost – (an idiom: red

tape —

бюрократия, mare’s

nest —

абсурд).

A. V. Kunin’s theory is based on the concept of specific stability at

the

phraseological

level; phraseological units are crtaracterized by a certain minimum

of

phraseological

stability. A.V. Kunin distinguishes stability of usage, structural

and

semantic

stability, stability of meaning and lexical constituents,

morphological

stability

and syntactical stability. The degree of stability may vary so that

there are

91

several

‘limits’ of stability. But whatever the degree of stability might

be, it is the

idiomatic

meaning that makes the characteristic feature of a phraseological

unit.

There

is one trend more worth mentioning in the theory of English

phraseology

that

of A. I. Smirnitsky. A.I. Smirnitsky takes as his guiding principle

the equivalence

of

a phraseological unit to a word. There are two characteristic

features that make a

phraseological

unit equivalent to a word, namely, the integrity of meaning and the

fact

that both the word and the phraseological unit are ready-made units

which are

reproduced

in speech and are not organized at the speaker’s will.

Whatever

the theory the term phraseology is applied to stable combinations of

words

characterized by the integrity of meaning which is completely or

partially

transferred,

e. g.: to

lead the dance проявлять

инициативу; to

take the cake

одержать

победу. Phraseological units are not to be mixed up with stable

combinations

of words that have their literal meaning, and are of non

phraseological

character,

e.g. the

back of the head, to come to an end.

Among

the phraseological units N.N.Amosova distinguishes idioms,

i.e.

phraseological

units characterized by the integral meaning of the whole, with the

meaning

of each component weakened or entirely lost. Hence, there are

motivated

and

demotivated

idioms.

In a motivated idiom the meaning of each component is

dependent

upon the transferred meaning of the whole idiom, e. g. to

look through

one’s

fingers (смотреть

сквозь пальцы); to

show one’s cards (раскрыть

свои

карты).

Phraseological units like these are homonymous to free syntactical

combinations.

Demotivated idioms are characterized by the integrity of meaning as a

whole,

with the meaning of each of the components entirely lost, e. g. white

elephant

(обременительное

или разорительное имущество), or to

show the white feather

(cтpycить).

But there are no hard and fast boundaries between them and there may

be

many

borderline cases. The second type of phraseological units in N.N.

Amosova’s

classification

is a phraseme.

It is a combination of words one element of which has a

phraseologically

bound meaning, e. g. small

years (детские

годы); small

beer

(слабое

пиво).

According

to A.I. Smirnitsky phraseological units may be classified in respect

to

their structure into one-summit

and

many-summit

phraseological units.

Onesummit

phraseological

units are composed of a notional and a form word, as, in

the

soup

—

быть в затруднительном положении, at

hand —

рядом, under

a cloud –

в

плохом

настроении, by

heart —

наизусть,

in the pink –

в расцвете. Many-summit

phraseological

units are composed of two or more notional words and form words as,

to

take the bull by the horns —

взять быка зарога,

to wear one’s heart on one’s

sleeve

—

выставлять свои чувства на показ, to

kill the goose that laid the golden

eggs

—

уничтожить источник благосостояния;

to

know on which side one’s bread

is

buttered —

быть себе на уме.

Academician

V.V.Vinogradov’s classification is based on the degree of

idiomaticity

and distinguishes three groups of phraseological units:

phraseological

fusions,

phraseological unities, phraseological collocations.

Phraseological

fusions are

completely non-motivated word-groups, e.g.: red

tape

– ‘bureaucratic

methods’; kick

the bucket – die,

etc. Phraseological

unities are

92

partially

non-motivated as their meaning can usually be understood through the

metaphoric

meaning of the whole phraseological unit, e.g.: to

show one’s teeth –

‘take

a threatening tone’; to

wash one’s dirty linen in public – ‘discuss

or make public

one’s

quarrels’.

Phraseological

collocations are

motivated but they are made up of

words

possessing specific lexical combinability which accounts for a

strictly limited

combinability

of member-words, e.g.: to

take a liking (fancy) but

not to

take hatred

(disgust).

There

are synonyms among phraseological units, as, through

thick and thin, by

hook

or by crook, for love or money —

во что бы то ни стало; to

pull one’s leg, to

make

a fool of somebody —

дурачить;

to hit the right nail on the head, to get the

right

sow by the ear —

попасть в точку.

Some

idioms have a variable component, though this variability is.

strictly

limited

as to the number and as to words themselves. The interchangeable

components

may be either synonymous, as

to fling (or throw) one’s (or the) cap over

the

mill (or windmill), to put (or set) one’s (or the) best foot first

(foremost, foreward)

or

different words, not connected semantically,

as to be (or sound, or read) like a

fairy

tale.

Some

of the idioms are polysemantic, as, at

large —

1) на свободе, 2) в

открытом

море, на большом пространстве, 3) без

определенной цели, 4) не

попавший

в цель, 5) свободный, без определенных

занятий, 6) имеющий

широкие

полномочия, 7) подробно, во всем объеме,

конкретно.

It

is the context or speech situation that individualizes the meaning of

the

idiom

in each case.

When

functioning in speech, phraseological units form part of a sentence

and

consequently

may undergo grammatical and lexical changes. Grammatical changes

are

connected with the grammatical system of the language as a whole,

e.g.: He

didn’t

work,

and he spent a great deal of money, and he

painted the town red.

(W. S.

Maugham)

(to

paint the town red —

предаваться веселью). Here

the infinitive is

changed

into the Past Indefinite. Components of an idiom can be used in

different

clauses,

e.g.: …I

had to put up with, the

bricks they

dropped,

and their embarassment

when

they realized what they’d done.

(W. S. Maugham) (to

drop a brick —

допустить

бестактность).

Possessive

pronouns or nouns in the possessive case may be also added, as:

…the

apple of his uncle’s eye…(A.

Christie) (the

apple of one’s eye —

зеница ока).

But

there are phraseological units that do not undergo any changes, e.

g.: She

was

the friend in adversity; other people’s business was meat

and drink to her. (W.

S.

Maugham) (be)

meat and drink (to somebody)

— необходимо как воздух.

Thus,

we distinguish changeable and unchangeable phraseological units.

Lexical

changes are much more complicated and much more various. Lexical

modifications

of idioms achieve a stylistic and expressive effect. It is an

expressive

device

at the disposal of the writer or of the speaker. It is the integrity

of meaning that

makes

any modifications in idioms possible. Whatever modifications or

changes an

idiom

might’ undergo, the integrity of meaning is never broken. Idioms may

undergo

93

various

modifications. To take only some of them: a word or more may be

inserted to

intensify

and concretize the meaning, making it applicable to this particular

situation:

I

hate the idea of Larry making such

a mess of

his life.

(W. S. Maugham) Here the

word

such

intensifies

the meaning of the idiom. I

wasn’t keen on washing

this kind of

dirty

linen in

public. (C.

P. Snow) In this case the inserted this

kind makes

the

situation

concrete.

To

make the utterance more expressive one of the components of the idiom

may

be replaced by some other. Compare: You’re

a

dog in the manger,

aren’t you,

dear?

and: It was true enough: indeed she was a

bitch in the manger.

(A.

Christie)

The

word bitch

has

its own lexical meaning, which, however, makes part of the

meaning

of the whole idiom.

One

or more components of the idiom may be left out, but the integrity of

meaning

of the whole idiom is retained, e.g.: «I’ve

never spoken to you or anyone else

about

the last election. I suppose I’ve got to now. It’s better to

let it lie,»

said Brown.

(C.

P. Snow) In the idiom let

sleeping dogs lie two

of the elements are missing and it

refers

to the preceding text.

In

the following text the idiom to

have a card up one’s sleeve is

modified:

Bundle

wondered vaguely what it was that Bill had

or thought he had-up in his

sleeve.

(A, Christie) The component card

is

dropped and the word have

realizes

its

lexical

meaning. As a result an, allusive metaphor is achieved.

The

following text presents an interesting instance of modification: She

does

not

seem to think you are a

snake in the grass,

though she sees a good deal of grass

for

a snake to be in. (E.

Bowen) In the first part of the sentence the idiom a

snake in

the

grass is

used, and in the second part the words snake

and

grass

have

their own

lexical

meanings, which are, however, connected with the integral meaning of

the

idiom.

Lexical

modifications are made for stylistic purposes so as to create an

expressive

allusive metaphor.

LITERATURE

1.

Arnold I.V. The English Word. – М., 1986.

2.

Antrushina G.B. English Lexicology. – М., 1999.

3.

Ginzburg R.Z., Khidekel S.S. A Course in Modern English

Lexicology. – М.,

1975.

4.

Kashcheyeva M.A. Potapova I.A. Practical English lexicology. – L.,

1974.

5.

Raevskaya N.N. English Lexicology. – К., 1971.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

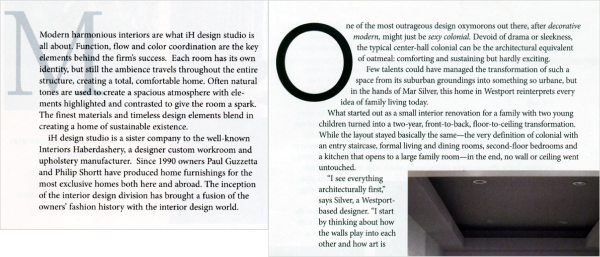

A historiated illuminated initial

In a written or published work, an initial capital, also referred to as a drop capital or simply an initial cap, initial, initcapital, initcap or init or a drop cap or drop, is a letter at the beginning of a word, a chapter, or a paragraph that is larger than the rest of the text. The word is derived from the Latin initialis, which means standing at the beginning. An initial is often several lines in height and in older books or manuscripts are known as «inhabited» initials. Certain important initials, such as the Beatus initial or «B» of Beatus vir… at the opening of Psalm 1 at the start of a vulgate Latin. These specific initials in an illuminated manuscript were also called initiums.

In the present, the word «initial» commonly refers to the first letter of any word or name, the latter normally capitalized in English usage and is generally that of a first given name or a middle one or ones.

History[edit]

A set of sixteenth-century initial capitals

The classical tradition was slow to use capital letters for initials at all; in surviving Roman texts it often is difficult even to separate the words as spacing was not used either. In late antiquity (c. 4th–6th century) both came into common use in Italy, the initials usually were set in the left margin (as in the third example below), as though to cut them off from the rest of the text, and about twice as tall as the other letters. The radical innovation of insular manuscripts was to make initials much larger, not indented, and for the letters immediately following the initial also to be larger, but diminishing in size (called the «diminuendo» effect, after the musical term). Subsequently, they became larger still, coloured, and penetrated farther and farther into the rest of the text, until the whole page might be taken over. The decoration of insular initials, especially large ones, was generally abstract and geometrical, or featured animals in patterns. Historiated initials were an Insular invention, but did not come into their own until the later developments of Ottonian art, Anglo-Saxon art, and the Romanesque style in particular. After this period, in Gothic art large paintings of scenes tended to go in rectangular framed spaces, and the initial, although often still historiated, tended to become smaller again.

In the very early history of printing, the typesetters would leave blank the necessary space, so that the initials could be added later by a scribe or miniature painter. Later initials were printed using separate blocks in woodcut or metalcut techniques.

-

Greek biblical text from Papyrus 46, of c. 200, with no initials, punctuation, and barely spaces between words

-

Leaf from a Coptic manuscript, 6th-14th century, Metropolitan museum of Art, New-York

-

«Diminuendo» effect in the first letters after this initial from the Cathach of St. Columba (Irish, 7th century)

-

One of thousands of smaller decorated initials from the Book of Kells

-

-

Large initial L from a Romanesque Bible

-

Opening from the Mainz Psalter, printed in 1457, with small printed and large drawn initials.

-

-

Two row-wide P initial, followed by small capitals

Since 2003, the W3C is working for initial letter modules for CSS Inline Layout Module Level 3, which standardized the output of initial letters for web pages.[1][2]

Types of initial[edit]

The initials are morphologically classified: the rubricated letter (red); the epigraphic letter, imitating ancient Roman majuscules; the figurated initial (usually in miniatures); the historiated initial, that gives spatial support to scenes of a narrative character; etc.

The initial may sit on the same baseline as the first line of text, at the same margin, as it does here. This is the easiest to typeset on a computer, including in HTML. An example follows (using Lorem ipsum nonsense text):

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Alternatively, the initial may be in the left margin, with the text indented, as shown here. In word processors and HTML, this may be implemented using a table with two cells, one for the initial and one for the rest of the text. The difference between this and a true drop cap may be seen when the text extends below the initial. For example:

L orem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

With a drop cap, the initial sits within the margins and runs several lines deep into the paragraph, indenting some normal-sized text in these lines. This keeps the left and top margins of the paragraph flush.

In modern computer browsers, this may be achieved with a combination of HTML and CSS by using the float: left; setting. A CSS-only solution alternatively can use the :first-letter pseudo-element. An example of this format is the following paragraph:

L

orem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

In some older manuscripts, the first letter of normal sized text after a drop cap also would be capitalized, as may be seen in the Mainz Psalter above, and in the original 1609 printing of Shakespeare’s sonnets. This evoked the handwritten «diminuendo» style of gradually reducing the text size over the course of the first line. This style now is rare, except in newspapers.

See also[edit]

- Calligraphy – Visual art related to writing

- Middle initial – Abbreviation of middle name

- Monogram – Motif made by overlapping two or more letters

- Typography – Art of arranging type

References[edit]

- ^ Dave Cramer; Elika J. Etemad; Steve Zilles (8 August 2018). «CSS Inline Layout Module Level 3». W3C Working Draft. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Marcotte, Ethan (17 June 2019). «Drop caps & design systems». Vox Product Blog. Vox Media. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Stiebner, Erhardt D; Urban, Dieter (1985), Initials and Decorative Alphabets, Poole, ENG, UK: Blandford, ISBN 0-7137-1640-1.

External links[edit]

Look up initial in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Initials.

- Typolis.de

- Types of illuminated initials in the Glossary of Medieval Art and Architecture

- Ornamento Ornamento contains close to a quarter of a million ornate letters, ornaments, borders, musical notation, diagrams, and illustrations drawn from Iberian print before 1701.

- Initials and Ornaments by Book Historian on Flickr.com

- Alphabets & Letters at Reusableart.com

- Make the letter bigger: A history of initials at ilovetypography.com