It will differ from dictionary to dictionary. Some of the standard information that can be listed for words include the items given below, listed from the 1979 Webster’s New Collegiate. There are so many kinds of words and so many functions in a variety of contexts that it would take pages to include all possible information given.

- The Entry; the word to be defined. This can be a single word, a hyphenated word, or in some cases two words, like ‘teaching fellow’ or ‘electron volt’.

- The Pronunciation, sometimes within backward slashes, according to a standard system of symbols.

- Part or Speech, or some other functional label.

- Inflected Forms. For example, when the plural of nouns causes y to change to i, or when there are any irregularities in forming plurals; also the principal parts of verbs are shown here;

- Etymology; this is what we know of the history and origin of the word.

- Usage: There are indications of the current use of the word or sense of the word, whether it is part of a dialect, is a nonstandard word or sense of a word.

- Definitions, with different senses the word can take, and other kinds of divisions;

- Cross-References; sometimes included when the dictionary user is invited to look at another entry for more related information.

- Synonyms & Antonyms

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What information about a word is given in the dictionary?

Write your answer…

What is a dictionary?

A dictionary is a reference book about words and as such it describes the functioning of individual words (sometimes called lexical items). It does so by listing these words in alphabetical order in the form of headwords, the words listed as entries in the dictionary.

What is the difference between a dictionary, an encyclopedia and a thesaurus?

Even though this section focuses on dictionaries, it will be useful initially to distinguish between a dictionary, an encyclopedia and a thesaurus. Both a dictionary and an encyclopedia are reference works, but whereas an encyclopedia conveys knowledge about the world as we know it (e.g. things, people, places and ideas), the dictionary gives information about certain items in the communication system (the language) used by people to exchange messages about the world.

A further distinction can be made between a dictionary and a thesaurus, where the latter can be seen as a word book which is structured around lexical items of a language according to sense relations, most notably synonomy (words having the same or very similar meanings) (Kirkness, 2004).

Click on the link below to access the online version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

What different types of dictionary are there?

One distinction that can be made is that between dictionaries that deal with one single language and those that deal with several languages. Firstly, a dictionary that deals only with one language is called a monolingual dictionary. For example, English monolingual dictionaries like the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE) or the Collins Cobuild Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (CCALD) have English headwords, English definitions, and all examples and additional information are given in English.

Secondly, a dictionary that deals with two languages (e.g. English-Swedish) is called a bilingual dictionary. For example, Norstedts Stora Svensk-Engelska Ordbok (Norstedts, 2000) presents headwords in Swedish, whereas meanings (translation equivalents) are given in English. Example sentences are often given in both languages.

Thirdly, a dictionary that deals with more than two languages is called a multilingual dictionary.

All these types of dictionary can furthermore be divided into general or specialised dictionaries. The general dictionaries, as the name implies, deal with the more general side of one or several languages. For example, Norstedts Stora Engelsk-Svenska Ordbok (Norstedts, 2000) is aimed a covering some 135,000 of the most commonly occurring words of English.

A specialized dictionary, on the other hand, focuses on a more narrow and specialized part of a language, for example the words used in engineering, medicine, aviation, experimental psychology, etc. The specialized dictionary is thus typically a subject-specific technical dictionary, but other types exist too, e.g. dictionaries of false friends, pictorial dictionaries, collocation dictionaries, idiom dictionaries, etc.)

For what purposes are dictionaries typically used?

Even though dictionaries can be used for many different purposes, a useful distinction that can be made is that between comprehension (decoding) and production (encoding) purposes. Nation (2001) provides the following lists of typical uses:

Typical comprehension uses are:

- Looking up unknown words that are encountered when listening

or reading - Confirming the meanings of partially known words

- Conforming guesses from context

Typical production uses are:

- Looking up unknown words needed to speak or write

- Looking up spelling, pronunciation, meaning, grammar, constraints

on use, collocations, inflections and derived forms of partly known

words. - Confirming the spelling, pronunciation, meaning etc. of known words.

- Checking that a word actually exists

- Finding a different word to use instead of a known one (a

synonym) - Correcting errors and mistakes

Since this website is dedicated to academic writing, it will make sense to take a closer look at the process involved in production (encoding) of written language and the dictionary use typically needed in this process.

What information can be found in a dictionary?

Whatever type of dictionary you use, it is worthwhile spending some time with the user’s guide, i.e. the initial pages that explain what kind of information is provided in the dictionary, the layout of the entries, and often also a legend that explains what the symbols used in the dictionary mean.

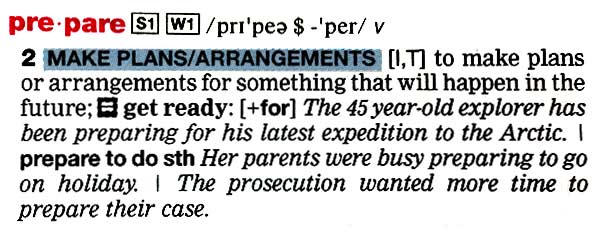

In terms of what type of information is given in a typical entry, here is an example of what is normally found in a mono-lingual dictionary (here based on the structure in the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE):

1. Spelling: the headword itself is given in its normal spelling, printed in bold. Headwords are arranged alphabetically in a dictionary.

2. Frequency information: symbols indicating how frequent the word is in spoken and written English. In LDOCE the symbols are boxes with either an’S’ (spoken) or a ‘W’ (written) followed by a number. For example, a box saying W2 means that the headword in question belongs to the second thousand most common words in written English.

3. Pronunciation: phonetic script, given within parentheses ( ) or slash / / brackets, tells us how to pronounce the word (the pronunciation of the word is transcribed following the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)).

4. Word class: the word class (also called part-of-speech) of the word and other grammatical information is provided following conventional abbreviations, such as n for Noun and v for Verb.

5. Sense(s): when a word has more than one meaning, then the different senses are numbered. When a sense or a group of senses belong to a different word class, this is indicated. For each sense, a definition is given which at the same time also functions as an explanation of its meaning.

6. Collocations, phrasal use and the syntactic operation of the word: examples are given of how the headword may be combined with other words to form idiomatic language usage.

Naturally, dictionaries differ in terms of what information is provided and in what order, but the above example typically illustrates what types of information are included in an English Foreign Language (EFL) dictionary entry. As was stated above, it is worthwhile spending some time with the initial pages of a dictionary, where the entry structure and its symbols are explained.

- IPA (The International Phonetic Assiciation)

- IPA (The International Phonetic Alphabet)

- Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English

Using monolingual dictionaries when writing academic English

Generally speaking, a slightly higher proficiency in a language is needed when using a monolingual dictionary than a bilingual dictionary (see Nation, 2001). This is so partly because definitions of words may sometimes contain infrequent words themselves, and explanations of usage of words may sometimes require fairly sophisticated grammar skills. Furthermore, monolingual dictionaries typically contain much more information about each word than do bilingual dictionaries.

One potential advantage of using monolingual dictionaries, as argued by Baxter (1980 [in Nation 2001: 291]), is that it should become clear to the user that meaning can be conveyed by a definition as well as by a single word. Examples of dictionaries that are especially suited to writing English are the Longman Language Activator (LLA) and the Oxford Collocations Dictionary for Students of English (OCDSE).

The LLA is a monolingual dictionary (English) which is structured around frequent headwords that can be seen to correspond to reasonably common concepts. For example, say we want to write a text about doctors. By looking up the entry doctor in the dictionary we get a wealth of information, such as the definition of the word, but more specifically we are presented with numerous examples of related words and concepts like physician, GP, specialist, surgeon, intern etc.

Moreover, we also get ample information about different kinds of doctors presented under headings such as «a doctor who treats mental illnesses», «a doctor who treats people’s teeth» and «a doctor who treats animals». This should provide a writer with a better and more nuanced understanding of what words to use in his or her text.

The OCDSE is a specialized monolingual (English) dictionary that focuses on the presentation of collocations. Broadly speaking, collocations are words that frequently occur together in a language, as used by native speakers. For example, in English the word combinations strong wind and heavy rain are natural-sounding collocations. However, *heavy wind and *strong rain are not.

The reason for this is strictly not a grammatical one. Rather, it has to do with the fact that certain words have, through convention, been used together with other words to the point that these words are now strongly linked to each other. Consequently, in order to write idiomatic English, a writer of a text must pay attention to how words are combined, not only in a strict grammatical sense, but also in a more lexical sense.

Even though a sequence of English is grammatically correct, it does not mean that the sequence sounds good when judged by native speakers. For example, assume that a writer wants to produce a text on pollution and how to avoid it. Although a sequence like avoid pollution makes sense, it might not be what native speakers of English would typically say or write. By looking up the word pollution in OCDSE, our writer can find listed a number of verbs that can be used to express finer nuances of the notion of avoiding pollution, for example combat pollution, fight pollution and tackle pollution. This illustrates how a dictionary like the OCDSE can be used to find naturally sounding collocations for known words (and concepts).

Using bilingual dictionaries when writing academic English

A bilingual dictionary (sometimes called a translation dictionary) is good when we want to find translations of words, be it going from our mother tongue to a foreign language, or from a foreign language to our mother tongue. Bilingual dictionaries are particularly good when we want to write something in a foreign language. This situation entails turning ideas into language which means that we want to find word forms to express messages. Bilingual dictionaries that go from the mother tongue (L1) to the foreign language we want to use (L2) is normally seen as an effective way of doing this (Nation, 2001).

clicking here.

This message will disappear when then podcast has fully loaded.

A good dictionary is an essential tool for any language learner. It can, however, be difficult to use, and not all

language learners fully understand how a dictionary works, or the best type to use. This section will consider

different types of dictionary and the advantages and disadvantages of each, as well as looking at the

features of a good dictionary. It concludes by looking at ways to

improve dictionary use.

Types of dictionary

Dictionaries can be categorised in several different ways. One way relates to the number of languages used.

Most beginning students will start with a bilingual dictionary, which has words in English translated

into their own language (the

prefix bi- means two). A more advanced type of dictionary is a

monolingual dictionary, which is entirely in one language (the prefix mono- means one).

While a bilingual dictionary is generally easier to use than a monolingual one, the information it contains

may not be as comprehensive. Another disadvantage of a bilingual dictionary is that the student may rely too much on their own language,

rather than thinking and working in English. Progressing from a bilingual to a fully monolingual dictionary is one sign that a language

learner is becoming more confident and proficient in their language use.

Another way to categorise dictionaries is by format. The traditional dictionary is a book in paper format.

However, electronic dictionaries, such as those which can be downloaded to a mobile phone, are now extremely popular, perhaps more

so than paper dictionaries. Online dictionaries are another popular format. Electronic (and, to some extent, online)

dictionaries have the advantage of being very lightweight. Additionally, searching for words is usually very quick. A disadvantage

is that they may not contain the same level of detail as a paper dictionary (though many of the most well-known dictionaries

are available in electronic versions which are identical to the paper one). Another disadvantage is that, because of how the

word is retrieved (by typing it in), students will lose the chance to practise

scanning skills, in contrast to how they look up the word in a paper dictionary.

A third way to categorise dictionaries is by content. In addition to general English dictionaries,

there are dictionaries for specific types of word, such as

idioms, places, abbreviations, slang and so on,

and dictionaries for words used in

particular fields, such as medical English or English for economics.

These specialist types of dictionary are of course useful for those studying or interested in particular areas.

However, specialist terms will usually be explained or defined where they appear (in a book or lecture), unlike

general academic words, which usually will not.

For improving academic English, a general English dictionary is essential. The rest of this page will consider general rather than

specialist English dictionaries.

A final way to categorise dictionaries is by level. Students may start their English study with a beginner’s dictionary.

For academic English study, however, a higher level of dictionary is required. An intermediate level dictionary

might be acceptable at the initial stages of an academic English course. The range of

vocabulary used in academic texts, however, means that an advanced dictionary will eventually be essential.

Features of a good dictionary

The features of a good dictionary relate fairly closely to the

features of vocabulary a learner needs to study. They include

meaning,

usage,

grammar,

spelling and

pronunciation. A few

other areas are also considered.

Meaning

The most important information about a word that a dictionary contains is the meaning.

One word can have many different meanings, some of which may be very similar to each other, while some might be

quite different. The meanings are usually listed in order of frequency, in other words so that the most

common meaning comes first, with the least common one at the end. Consider the following two sentences,

using the word appreciate.

- Few people appreciate the importance of a good dictionary.

- He appreciated the help his teacher gave him.

The following is the dictionary entry for this word, taken from Princeton’s Wordnet database (a

copy of which is available on this website).

1. recognize with gratitude; be grateful for.

2. be fully aware of; realize fully. E.g.: Do you appreciate the full meaning of this letter? [Syn: take account]

3. hold dear. [Syn: prize, value, treasure]

4. gain in value. E.g.: The yen appreciated again! [Syn: apprize, apprise, revalue]

5. increase the value of. E.g.: The Germans want to appreciate the Deutsche Mark [Syn: apprize, apprise]

The meaning for the word appreciate in the first sentence is ‘be fully aware of’, which is the second meaning in the list. The meaning

of appreciate in the second sentence is ‘be grateful for’, the first meaning in the list. These meanings are quite different. As the

first meaning is more common, it is more likely that a student would know this one, and less likely that they would know the second meaning.

Usage

A good dictionary will also provide examples of usage. This is generally done in two ways.

One is by explicitly giving this information. Consider the following example for the word prepare from the Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English.

This entry tells us that for the meaning of ‘get ready’ the word prepare is followed by

for, and that when followed by a verb, the form should be to do sth (not ‘doing sth’).

The other way to give information on usage is indirectly, via examples sentences alone, without explicitly

giving the usage information. In this case, the learner has to look more carefully to understand how the word is used.

A dictionary might show usage by indicating which prepositions a word is used with, for example

afraid of, interested in or good at. It may also give information on common

collocations for the word. Understanding how a word combines

with other words in a sentence is important if it is to be used productively in speaking and writing.

Information on usage will help the learner to appreciate that vocabulary study is not just about single words,

but involves considering groups of words which go together.

Grammatical information

A good dictionary will give grammatical information about each word. The most basic type is part of speech,

that is whether the word is a noun, verb, adjective, adverb and so on. Other grammatical information which

can be given is whether a noun is countable or uncountable, whether a verb is irregular, or whether a verb is

transitive (i.e. followed by an object), intransitive (not followed by an object) or both. Most dictionaries will use a series

of abbreviations for this, for example [U] for uncountable, irreg for irregular, and vt and vi for

transitive and intransitive verbs respectively.

Spelling

English spelling can be a very difficult area even for those whose first language is English. A dictionary will

obviously be useful in checking the spelling of words, which is important for writing. If you are

typing up an essay or assignment, the word processing software you are using will

almost certainly have a spellcheck function which will probably be your first step in checking spelling, for example when

proofreading. Where a dictionary is most

useful is in pointing out special spelling rules, such as whether a final letter needs to be doubled when creating verb

forms, such as format which has verb forms formats, formatted and formatting. A dictionary will

give information on variant spellings, for instance British versus American English.

Pronunciation

A good dictionary will also give information on pronunciation, which is especially important if you want to use

the word in your speaking. A paper dictionary will do this

using the phonemic alphabet, which is a transcription using special symbols. Getting used to these symbols

takes time and practice. This transcription will include a mark showing where the stress in a word is if it contains

more than one syllable. Pronunciation is one major advantage of an electronic or online dictionary, as these

types of dictionary will generally enable you to listen to the word.

Other information

A dictionary may give other useful information. For example, it may tell you about

frequency, in other words

how common the word is. It may also give information on register, in other words

whether it is formal or informal, or used in spoken rather than written English. A dictionary may also indicate whether a word or

meaning is used in a specialist subject.

Improving dictionary use

There are several ways a student can improve their dictionary use. The most obvious way is to use it regularly and

therefore become familiar with how it works. As noted above, dictionaries will employ a series of abbreviations, such as [U] for

uncountable nouns, and becoming familiar with these will make it easier to use a dictionary. If using a paper dictionary,

learning the phonemic alphabet will help the student to be able to pronounce the words.

There are various ways in which teachers can improve dictionary use in their students. One way is to encourage its use

in (or outside) class. Some teachers may be reluctant to do this as they might want students to try to

guess the meaning of words rather than turn to a dictionary.

While it is true that good learners do not use a dictionary for every unknown word and try to guess the meaning first, it

is rarely possible to guess the meaning of all unknown words accurately, and checking in a dictionary is usually necessary.

Another way in which a teacher can improve dictionary use is to recommend a dictionary for their students. As noted above,

there are a wide array of dictionaries available, and learners may be confused about the

type of dictionary which suits them best.

A third way in which teachers can improve dictionary use is

to engage in learner training with dictionaries, for example quizzing students on the different abbreviations used in a

dictionary, or asking which of the different meanings of a word is the one used in the context in which the word is found.

This type of learner training works best if all students are using the same dictionary.

A final way in which a teacher can

improve dictionary use is by encouraging students to check meanings in more than one dictionary. This will enable them to

understand that a dictionary is a source of information, and turn them into researchers, in much the same way that they will

research information from more than one source for assignment use.

References

Olwyn, A., Argent, S. and Spencer, J. (2008) EAP Essentials: A teacher’s guide to principles and practice (pp.174-175). Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Redman, S., Ellis, R. and Viney, B. (1997) A Way With Words: Resource Pack 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. This extract from Unlock the Academic Wordlist: Sublists 1-3 contains all sublist 1 words, plus exercises, answers and more!

Checklist

The following checklist summarises the information on this page. Use it to check your understanding.

| Area | OK | Comments |

| I know the different types of dictionary (bilingual, monolingual and so on) and some of the advantages and disadvantages of each. |

||

| I understand the features of a good dictionary, including meaning, usage, grammar, spelling and pronunciation. |

||

| I know some ways in which I can improve dictionary use. |

-

Lexicography

as a branch of Linguistics. The relationship between Lexicography

and Lexicology. -

Some basic

problems of Lexicography. -

Types of dictionaries.

-

Historical development of

British and American Lexicography. -

New Trends in Lexicography.

13.1.

Lexicography

is the theory and practice of compiling dictionaries. It’s closely

connected with Lexicology for:

1) they have a common object

of study, i.e the vocabulary of a language;

2) they

make use of each other’s achievements, i.e. the material collected in

dictionaries

is used by linguistists in their research and on the other hand, the

principles of dictionary making are based on linguistic fundamentals.

The difference between them

lies in the degree of systematization and completeness each of them

is able to achieve.

Lexicology

aims at systematization, revealing characteristic features of words.

However, it can’t achieve completeness as regards vocabulary units,

for their number is very great, and systematization and completeness

can’t be achieved simultaneously.

But dictionaries aim at a more

or less complete description of individual words, but in doing so

they can’t attain systematic treatment.

13.2.

The

most important

problems

faced by lexicographers are:

-

the selection of lexical

units for inclusion; -

their arrangement;

-

the selection and arrangement

of word-meanings; -

the definition of meanings;

-

illustrative material;

-

supplementary material.

1. The selection of units for inclusion

The basic problem is what

lexical units to select for inclusion, and to determine the type and

number of headwords.

Should

we include / the dictionary contain foreign words? technical terms?

archaic words? new words? dialectisms? slang words, etc?

We face the problem of

polysemy and homonymy. Besides, we should decide how to treat

derivatives, esp. those built after the most productive patterns

(such as

v

+ -er → N, A + -ness → N, a + -ly → Adv).

Should they be given special entries or not?

There are no general answers

to these questions. The choice depends on the type of the dictionary,

its aim, size, and some other considerations, and is always more or

less arbitrary.

2. Arrangement of entries

When the problem of

arrangement is settled there arises the question which of the

selected units have the right to a separate entry and which are to be

included under the headword,

e.g

whether «each

other»

is a group of two separate words to be treated separately under the

headwords «each»

and «other»

or whether it is a unit that deserves a special entry.

The

number of entries also depends on how dictionary compilers solve the

problems of polysemy and homonymy and regularly formed derivatives

with such affixes as -er,

-ly, -ness, -ing.

The

order of arrangement

of the entries is different in different types of dictionaries. The

order may be (a)

alphabetical

and (b)

the

cluster-type order,

i.e. words of the same root, or close in their denotational meaning,

or in their frequency value are grouped together.

Each

mode of presentation has its advantages. (a)

The alphabetical order provides for an easy finding of any word, (b)

The cluster-type order requires less space and presents a clearer

picture of the relations of each unit with the others in the language

system.

Practically, however, most

dictionaries use a combination of these two orders of arrangement.

3.

The number of meanings and their choice depend

on:

1) the aim the dictionary

compilers set themselves;

2) how they treat obsolete,

dialectal, highly specialized meanings, how they solve the problem of

polysemy and homomymy.

There

are three

different ways

of arranging word-meanings:

1)

historical

order,

i.e. meanings are arranged in the order of their historical

development (from the earliest to the most recent ones);

2)

actual

(or empirical) order,

i.e. meanings are arranged according to their frequency value (the

most common ones come first);

3)

logical

order,

i.e. meanings are arranged to show their logical connection.

The historical order is mostly

used in diachronical (historical) dictionaries, and in synchronic

ones compilers usually use the empirical and the logical order.

4.

Meanings may be defined

in

different ways:

1) by means of encyclopedic

definitions (such definitions are concerned with objects for which

words are names);

2) by means of descriptive

definitions or paraphrases;

3) with the help of synonymous

words and expressions;

4) by means of

cross-reference.

Descriptive definitions are

used in a majority of cases. They are concerned with words as speech

material.

American dictionaries for the

most part are traditionally encyclopedic. They furnish their readers

with more information about facts and things than British

dictionaries which are more linguistic

Encyclopedic definitions are

typical of nouns, esp. proper nouns and terms.

Synonyms are most often used

to define verbs and adjectives, and (cross-) reference is used to

define derivatives, abbreviations and variant forms.

5.

Illustrative examples raise

the following questions:

1) when are examples to be

used?

2) what words may be listed

without any illustrations?

3) should they be made up or

borrowed from books and/or periodicals? (In diachronic dictionaries

quotations are used and they are carefully dated).

4) How much space should they

occupy?

6.

The supplementary material

appended to the dictionary may be:

1) material of linguistic

nature pertaining to the vocabulary (e.g. geographical names, foreign

words, standard abbreviations);

2) material of encyclopedic

nature (may include lists of colleges, universities, tables of

weights and measures, military ranks, etc.).

13.3.

All

dictionaries are divided into encyclopedic

and linguistic.

They differ in (1)

the choice of items included and (2)

in the information given about them.

Linguistic

dictionaries

are word-books. Their subject-matter is lexical units and their

linguistic properties (pronunciation, meaning, usage, etc.).

Encyclopedias

are thing-books, giving information about the extralinguistic world.

They deal with objects, phenomena and concepts. Encyclopedic

dictionaries

give both types of information.

The most famous encyclopedias

in English are the Encyclopedia Britannica (in 32 volumes) and

Encyclopedia Americana (30 volumes). Besides there are reference

books confined to some particular fields of knowledge,

e.g. the Oxford Art

Dictionary, the Oxford Companion to English Literature, «Who’s

Who» Dictionary, etc.

Linguistic dictionaries can be

classified by different criteria:

1)

According to the

nature of their word-list

they are general

and restricted.

General

dictionaries

contain lexical units in ordinary use in different spheres of

communication.

Restricted

dictionaries

make their choice from a certain part of the vocabulary,

e.g. phraseological

dictionaries, dialectal dictionaries, dictionaries of new words,

terminological dictionaries and so on.

2)

According to the

information supplied

dictionaries may be explanatory

and specialized.

Explanatory

dictionaries

provide information on all aspects of lexical units (graphical,

grammatical, etymological, stylistic, semantic, etc.).

Specialized

dictionaries

deal with only some aspect of lexical units,

e.g. English Pronouncing

Dictionary by Daniel Jones.

3)

According to

the

language

in which information is given dictionaries may be: monolingual

end bilingual

(translation).

4)

According to the

prospective user dictionaries

are divided into those

meant for scholars

(e.g. etymological dictionaries), for

language learners/students

(e.g. Oxford Student’s Dictionary of Current English by A.S. Hornby)

and for

the general public

(e.g. The Concise Oxford Dictionary).

13.4.

Historical

Development of British and American Lexicography.

|

period |

||

|

I |

5th |

A The |

|

II |

16th |

The |

|

III |

17th Dictionaries |

These |

|

IV |

17th the |

Dictionaries |

|

V |

second Prescriptive Dictionaries |

It

In

Johnson gave little

His dictionary enjoyed

Pronouncing |

|

VI |

latter |

contributed to dictionary

The The |

13.5.

Since the 1970s, the flow of dictionaries has been unabated, as

publishers try to meet the needs of an increasingly

language-conscious age. New editions and supplements to the

well-known dictionaries have appeared and several publishers have

launched new general series (e.g.Longman). Reader’s Digest .produced

its great Illustrated Dictionary in 1984, the first full-colour

English dictionary, in the encyclopedic tradition. Prominent also

have been the dictionaries for special purposes (foreign language

teaching, linguistics, medicine, chemistry, etc.). For the first

time, spoken vocabulary has begun to find its way into dictionaries.

The

1980s will one day be seen as a watershed in lexicography — the

decade in which computer applications began to alter radically the

methods and the potential of lexicography: the future is on disc, in

the form of vast lexical databases, continuously updated, that can

generate a dictionary of a

given

size and scope in a fraction of the time it used to take. Special

programs have become available enabling people to ask the dictionary

special questions (e.g. «find all words ending in -esse»).

Access to large machine-dictionaries is becoming routine in offices

and homes.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Language is a living thing, and so is Dictionary.com. Our dictionary will always be a work in progress—there’s no day in the future when we’ll mark it “complete” after adding the last word.

This never-ending work is the job of our lexicographers, the (amazingly talented) people who write and edit the dictionary. They do more than just add and define words. They also add new definitions to existing entries for words that have developed new senses over time. They revise definitions that have become outdated or have otherwise changed. And they add and update other key lexicographical content, like pronunciations and etymologies.

How does a word get into the dictionary?

This is one of the most common questions we get—and it’s a great one.

The answer involves one of the most misunderstood things about dictionaries, so let’s set the record straight: a word doesn’t become a “real word” when it’s added to the dictionary. It’s actually the other way around: we add words to the dictionary because they’re real—because they’re really used by real people in the real world.

The criteria

In other words, our lexicographers add a word to the dictionary when they determine that:

- It’s a word that’s used by a lot of people.

- It’s used by those people in largely the same way.

- It’s likely to stick around.

- And it’s useful for a general audience.

All four of these points are important. Our lexicographers look for use not just by one person, but by a lot of people. Of course, many words have different shades of meaning for different people. But to be added to the dictionary, a word must have a shared meaning (that is, it must communicate a widely agreed-upon meaning from one person to the next). If everyone used a word in a completely different way, we wouldn’t be able to give it a definition, right?

Prescriptive vs. Descriptive

As we define it, our mission as a dictionary is to document words as they are actually used. In the world of dictionaries, this approach is called descriptivism. The opposite is prescriptivism, an approach that frames the dictionary in the role of a gatekeeper and is based on prescribing (setting rules for) how words should or should not be used. While prescriptivists might say a slang term is “not a real word,” descriptivists will look at the same term and do research to see if and how it’s commonly used in order to describe (document) its use. (Read more about this in the next FAQ, “That’s not a word.”)

We must acknowledge that, historically, dictionaries have been gatekeepers to nonstandard words and usage (especially those that originate in non-dominant groups), but we at Dictionary.com take very seriously our role and responsibility in ensuring that our dictionary reflects and respects the language of people as they use it.

Our lexicographers will be the first to tell you that documenting language in this way is a “messy business.” It takes a lot of research—and patience.

Identifying and tracking candidates

Lexicographers track a vast number of terms and topics, read a wide variety of writing and transcribed speech, and use corpora (big, searchable collections of texts) to see how terms are actually being used. They then distill this research into concise, informative definitions (along with supplementary information, such as pronunciations or notes about whether a word is offensive, for example).

Because we take this approach, our dictionary contains all kinds of words: standard words, slang words, dialect words, nonstandard words, and more. (Yes, this includes curse words and slurs. Read more about this in the FAQ “This word is offensive.”)

Staying power: prioritizing what gets added

Our main dictionary is a general dictionary, as opposed to a specialized one (like, for example, a medical dictionary—which we do also feature on the site). This means we have to prioritize the addition of terms based on whether the average person will be likely to encounter them—and whether it’s probable that people will continue to use them. For that reason, our lexicographers often wait until a word has gained some currency in the mainstream before selecting it for addition. (Read more about this in the FAQ “That word isn’t new.”)

Short answer: Lexicographers typically wait to add a word to our dictionary until they’ve determined that it has met these criteria:

- It has relatively widespread use.

- It has a widely agreed-upon meaning.

- It seems to have staying power—meaning it’s likely to be used for a long time.

- And it will be useful for a general audience.

That’s not a word. Why is it in the dictionary?

First off, we’re not fans of saying that something is “not a word.” Just because a word isn’t (yet) in the dictionary doesn’t mean that it’s “not a word” or that it’s not a “real word.”

Sometimes, people don’t think a word counts as a word if it’s informal, slang, “too new,” or a term they perceive to be “incorrect.” Irregardless (😉) of how you (or we) may feel personally about a particular word, our mission is to be descriptive—we work to describe and document language as it is really used (not just how we or others may want it to be used).

It’s important to note that judgments about what “counts” as a word often originate in conscious or unconscious biases, particularly about other people’s education, identity, or level of language proficiency.

Like we explained in the answer to the last question, we add a word to the dictionary when we observe a lot of people using it in the same way—and this includes many informal, slang, and nonstandard terms. You have the freedom to decide whether or not to use a word, but just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean it ain’t a word.

Short answer: Our mission is to document and define words as they’re actually used—not to be gatekeepers or make rules about what is or is “not a word.” And just because a word is not in the dictionary doesn’t mean it’s not a word.

Do you think supposably belongs in the dictionary? Find out why it’s there.

That word isn’t new. Why are you adding it now?

Just because a word is newly added to our dictionary doesn’t mean it’s brand new to the English language. That’s why we like to refer to newly added words as “new entries,” as opposed to “new words,” which can imply that they’ve very recently been coined.

In fact, it’s rare for us to add a very recently coined term unless it’s clear that it has rapidly gained widespread use and that such use is likely to continue. Brand new words sometimes burn brightly but then quickly die out, so our lexicographers look for evidence of staying power in the lexicon. It takes time to gather such evidence and for words to settle in. This is especially the case for informal words that originate in a particular dialect or group, which take time to spread from speech to writing, an important part of evidence-gathering.

Waiting so long to add some terms may make it look like we’re behind the times, like a person who sounds cheugy for using a trendy slang term way after its moment has passed. It’s an occupational hazard, but with so many possible terms to add, we have to make tough decisions about what to prioritize. Especially since prioritizing one word may mean pushing another down on the list. (And yes, there is a list. More like lists of lists.)

As a general dictionary, we have to prioritize adding words that the average person will be likely to encounter. For that reason, our lexicographers are always on the lookout for breakthrough moments when a specialized word spreads into more common, mainstream use (such as all the epidemiology terms that became household words during the pandemic).

If you’ve come across a word that is in widespread use but that doesn’t appear in the dictionary, chances are that our lexicographers are already in the process of compiling the information they need to give it its due home. (In other words, it’s probably already on the list.)

Short answer: We rarely add “new” words. We wait to add a word to the dictionary until we’ve determined that it has gained relatively widespread use and is likely to stick around. Also, there are a lot of words to keep track of, so sometimes it takes us a while.

I just created an awesome new word. How can I get it into the dictionary?

First of all, the word you made up is a word—don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. It’s a word because you’ve given it a meaning that can be shared and understood by others.

A lot of us make up new words. They’re called neologisms or coinages. Making up new words is fun, creative, and—especially when that word addresses a gap in the language—an extremely useful thing to do.

But for your word to get into the dictionary, it has to have meaning not just for you, or for you and a few friends and family members, but for a lot of people. Our lexicographers need evidence that the word is being used by many people in a meaningful, sustained way.

Don’t be discouraged. A lot of words that are now very common were straight up made up. They started as one person’s idea and other people found them so useful that they spread and spread until they found a place in the language—and the dictionary.

Short answer: Keep using your word until it catches on, and when it does, our lexicographers will surely take note! Our dictionary is full of words whose coiner is named in the origin section.

This word is offensive. Why don’t you remove it from the dictionary?

We believe our mission of accurately documenting how language is used in real life is valuable for many reasons.

However, our inclusion of a word in the dictionary never implies or indicates endorsement, promotion, or approval of that word. Including a word as a dictionary entry does not mean that we think you should use it.

In fact, there are actually many, many words in our dictionary that we strongly believe no one should ever use. These words are called slurs. Why are they in the dictionary, then?

We understand and acknowledge that encountering such terms anywhere—even and perhaps especially in a dictionary—can be harmful to the people they were created to target. We wish we had the power to prevent people from ever wanting to use slurs. But we strongly believe that removing them from the dictionary would not have the effect of preventing or discouraging people from using them. In fact, we strongly believe it would have the opposite effect.

We work to ensure that such words are not included in the dictionary without context—slurs are clearly labeled as offensive and often appear alongside major usage notes explaining why.

Without these entries and the information that accompanies them, we believe that it would make it easier for people who use slurs to continue making many of the usual excuses that they make when they’re called out for using them: that the slur doesn’t really mean what people claim it means; that it’s not really offensive; or that it wasn’t intended to be offensive (that it was simply being used as a harmless joke). These statements about slurs may sound familiar, but none of them are ever true: slurs are, by definition, intended to be harmful and offensive.

For the very reason that the use of such words is so pervasive and harmful, we feel it’s important that they remain in the dictionary, where their meaning, use, and history can be documented, and where they can be clearly labeled as offensive.

Short answer: Removing words from the dictionary does not make them cease to exist or prevent them from being used. And the inclusion of a word in the dictionary is not an endorsement of its use. An important part of the work of a dictionary is documenting slurs and labeling them as what they are—intentionally offensive—so that their use cannot be excused.