From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

WordPerfect, a word processor first released for minicomputers in 1979 and later ported to microcomputers, running on Windows XP

A word processor (WP)[1][2] is a device or computer program that provides for input, editing, formatting, and output of text, often with some additional features.

Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to the function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers.

The functions of a word processor program fall somewhere between those of a simple text editor and a fully functioned desktop publishing program. However, the distinctions between these three have changed over time and were unclear after 2010.[3][4]

Background[edit]

Word processors did not develop out of computer technology. Rather, they evolved from mechanical machines and only later did they merge with the computer field.[5] The history of word processing is the story of the gradual automation of the physical aspects of writing and editing, and then to the refinement of the technology to make it available to corporations and Individuals.

The term word processing appeared in American offices in early 1970s centered on the idea of streamlining the work to typists, but the meaning soon shifted toward the automation of the whole editing cycle.

At first, the designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies with emerging ones to develop stand-alone equipment, creating a new business distinct from the emerging world of the personal computer. The concept of word processing arose from the more general data processing, which since the 1950s had been the application of computers to business administration.[6]

Through history, there have been three types of word processors: mechanical, electronic and software.

Mechanical word processing[edit]

The first word processing device (a «Machine for Transcribing Letters» that appears to have been similar to a typewriter) was patented by Henry Mill for a machine that was capable of «writing so clearly and accurately you could not distinguish it from a printing press».[7] More than a century later, another patent appeared in the name of William Austin Burt for the typographer. In the late 19th century, Christopher Latham Sholes[8] created the first recognizable typewriter although it was a large size, which was described as a «literary piano».[9]

The only «word processing» these mechanical systems could perform was to change where letters appeared on the page, to fill in spaces that were previously left on the page, or to skip over lines. It was not until decades later that the introduction of electricity and electronics into typewriters began to help the writer with the mechanical part. The term “word processing” (translated from the German word Textverarbeitung) itself was created in the 1950s by Ulrich Steinhilper, a German IBM typewriter sales executive. However, it did not make its appearance in 1960s office management or computing literature (an example of grey literature), though many of the ideas, products, and technologies to which it would later be applied were already well known. Nonetheless, by 1971 the term was recognized by the New York Times[10] as a business «buzz word». Word processing paralleled the more general «data processing», or the application of computers to business administration.

Thus by 1972 discussion of word processing was common in publications devoted to business office management and technology, and by the mid-1970s the term would have been familiar to any office manager who consulted business periodicals.

Electromechanical and electronic word processing[edit]

By the late 1960s, IBM had developed the IBM MT/ST (Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter). This was a model of the IBM Selectric typewriter from the earlier part of this decade, but it came built into its own desk, integrated with magnetic tape recording and playback facilities along with controls and a bank of electrical relays. The MT/ST automated word wrap, but it had no screen. This device allowed a user to rewrite text that had been written on another tape, and it also allowed limited collaboration in the sense that a user could send the tape to another person to let them edit the document or make a copy. It was a revolution for the word processing industry. In 1969, the tapes were replaced by magnetic cards. These memory cards were inserted into an extra device that accompanied the MT/ST, able to read and record users’ work.

In the early 1970s, word processing began to slowly shift from glorified typewriters augmented with electronic features to become fully computer-based (although only with single-purpose hardware) with the development of several innovations. Just before the arrival of the personal computer (PC), IBM developed the floppy disk. In the early 1970s, the first word-processing systems appeared which allowed display and editing of documents on CRT screens.

During this era, these early stand-alone word processing systems were designed, built, and marketed by several pioneering companies. Linolex Systems was founded in 1970 by James Lincoln and Robert Oleksiak. Linolex based its technology on microprocessors, floppy drives and software. It was a computer-based system for application in the word processing businesses and it sold systems through its own sales force. With a base of installed systems in over 500 sites, Linolex Systems sold 3 million units in 1975 — a year before the Apple computer was released.[11]

At that time, the Lexitron Corporation also produced a series of dedicated word-processing microcomputers. Lexitron was the first to use a full-sized video display screen (CRT) in its models by 1978. Lexitron also used 51⁄4 inch floppy diskettes, which became the standard in the personal computer field. The program disk was inserted in one drive, and the system booted up. The data diskette was then put in the second drive. The operating system and the word processing program were combined in one file.[12]

Another of the early word processing adopters was Vydec, which created in 1973 the first modern text processor, the «Vydec Word Processing System». It had built-in multiple functions like the ability to share content by diskette and print it.[further explanation needed] The Vydec Word Processing System sold for $12,000 at the time, (about $60,000 adjusted for inflation).[13]

The Redactron Corporation (organized by Evelyn Berezin in 1969) designed and manufactured editing systems, including correcting/editing typewriters, cassette and card units, and eventually a word processor called the Data Secretary. The Burroughs Corporation acquired Redactron in 1976.[14]

A CRT-based system by Wang Laboratories became one of the most popular systems of the 1970s and early 1980s. The Wang system displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as they are known today. While early computerized word processor system were often expensive and hard to use (that is, like the computer mainframes of the 1960s), the Wang system was a true office machine, affordable to organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily mastered and operated by secretarial staff.

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (AES Data machines — re-badged), CPT, and NBI. All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with prices in the $10,000 range. Cheap general-purpose personal computers were still the domain of hobbyists.

Japanese word processor devices[edit]

In Japan, even though typewriters with Japanese writing system had widely been used for businesses and governments, they were limited to specialists who required special skills due to the wide variety of letters, until computer-based devices came onto the market. In 1977, Sharp showcased a prototype of a computer-based word processing dedicated device with Japanese writing system in Business Show in Tokyo.[15][16]

Toshiba released the first Japanese word processor JW-10 in February 1979.[17] The price was 6,300,000 JPY, equivalent to US$45,000. This is selected as one of the milestones of IEEE.[18]

Toshiba Rupo JW-P22(K)(March 1986) and an optional micro floppy disk drive unit JW-F201

The Japanese writing system uses a large number of kanji (logographic Chinese characters) which require 2 bytes to store, so having one key per each symbol is infeasible. Japanese word processing became possible with the development of the Japanese input method (a sequence of keypresses, with visual feedback, which selects a character) — now widely used in personal computers. Oki launched OKI WORD EDITOR-200 in March 1979 with this kana-based keyboard input system. In 1980 several electronics and office equipment brands entered this rapidly growing market with more compact and affordable devices. While the average unit price in 1980 was 2,000,000 JPY (US$14,300), it was dropped to 164,000 JPY (US$1,200) in 1985.[19] Even after personal computers became widely available, Japanese word processors remained popular as they tended to be more portable (an «office computer» was initially too large to carry around), and become necessities in business and academics, even for private individuals in the second half of the 1980s.[20] The phrase «word processor» has been abbreviated as «Wa-pro» or «wapuro» in Japanese.

Word processing software[edit]

The final step in word processing came with the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s and 1980s and with the subsequent creation of word processing software. Word processing software that would create much more complex and capable output was developed and prices began to fall, making them more accessible to the public. By the late 1970s, computerized word processors were still primarily used by employees composing documents for large and midsized businesses (e.g., law firms and newspapers). Within a few years, the falling prices of PCs made word processing available for the first time to all writers in the convenience of their homes.

The first word processing program for personal computers (microcomputers) was Electric Pencil, from Michael Shrayer Software, which went on sale in December 1976. In 1978 WordStar appeared and because of its many new features soon dominated the market. However, WordStar was written for the early CP/M (Control Program–Micro) operating system, and by the time it was rewritten for the newer MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), it was obsolete. Suddenly, WordPerfect dominated the word processing programs during the DOS era, while there was a large variety of less successful programs.

Early word processing software was not as intuitive as word processor devices. Most early word processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys such as «copy» or «bold». Moreover, CP/M lacked cursor keys; for example WordStar used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation. However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as “killer app” spreadsheet applications, e.g. VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software became serious competition for the dedicated machines and soon dominated the market.

Then in the late 1980s innovations such as the advent of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing (WYSIWYG — What You See Is What You Get), using bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), and graphical user interfaces such as “copy and paste” (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor). These were popularized by MacWrite on the Apple Macintosh in 1983, and Microsoft Word on the IBM PC in 1984. These were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people.

Of particular interest also is the standardization of TrueType fonts used in both Macintosh and Windows PCs. While the publishers of the operating systems provide TrueType typefaces, they are largely gathered from traditional typefaces converted by smaller font publishing houses to replicate standard fonts. Demand for new and interesting fonts, which can be found free of copyright restrictions, or commissioned from font designers, occurred.

The growing popularity of the Windows operating system in the 1990s later took Microsoft Word along with it. Originally called «Microsoft Multi-Tool Word», this program quickly became a synonym for “word processor”.

From early in the 21st century Google Docs popularized the transition to online or offline web browser based word processing, this was enabled by the widespread adoption of suitable internet connectivity in businesses and domestic households and later the popularity of smartphones. Google Docs enabled word processing from within any vendor’s web browser, which could run on any vendor’s operating system on any physical device type including tablets and smartphones, although offline editing is limited to a few Chromium based web browsers. Google Docs also enabled the significant growth of use of information technology such as remote access to files and collaborative real-time editing, both becoming simple to do with little or no need for costly software and specialist IT support.

See also[edit]

- List of word processors

- Formatted text

References[edit]

- ^ Enterprise, I. D. G. (1 January 1981). «Computerworld». IDG Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Waterhouse, Shirley A. (1 January 1979). Word processing fundamentals. Canfield Press. ISBN 9780064537223. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Amanda Presley (28 January 2010). «What Distinguishes Desktop Publishing From Word Processing?». Brighthub.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «How to Use Microsoft Word as a Desktop Publishing Tool». PCWorld. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Price, Jonathan, and Urban, Linda Pin. The Definitive Word-Processing Book. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1984, page xxiii.

- ^ W.A. Kleinschrod, «The ‘Gal Friday’ is a Typing Specialist Now,» Administrative Management vol. 32, no. 6, 1971, pp. 20-27

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. The Tech Ninja. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ See also Samuel W. Soule and Carlos Glidden.

- ^ The Scientific American, The Type Writer, New York (August 10, 1872)

- ^ W.D. Smith, “Lag Persists for Business Equipment,” New York Times, 26 Oct. 1971, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Linolex Systems, Internal Communications & Disclosure in 3M acquisition, The Petritz Collection, 1975.

- ^ «Lexitron VT1200 — RICM». Ricomputermuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (1 June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «Redactron Corporation. @ SNAC». Snaccooperative.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «日本語ワードプロセッサ». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ «【シャープ】 日本語ワープロの試作機». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ 原忠正 (1997). «日本人による日本人のためのワープロ». The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan. 117 (3): 175–178. Bibcode:1997JIEEJ.117..175.. doi:10.1541/ieejjournal.117.175.

- ^ «プレスリリース;当社の日本語ワードプロセッサが「IEEEマイルストーン」に認定». 東芝. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^

«【富士通】 OASYS 100G». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05. - ^ 情報処理学会 歴史特別委員会『日本のコンピュータ史』ISBN 4274209334 p135-136

Updated: 07/06/2021 by

Sometimes abbreviated as WP, a word processor is a software program capable of creating, storing, and printing typed documents. Today, the word processor is one of the most frequently used software programs on a computer, with Microsoft Word being a popular choice.

Word processors can create multiple types of files, including text files (.txt), rich text files (.rtf), HTML files (.htm & .html), and Word files (.doc & .docx). Some word processors can also be used to create XML files (.xml).

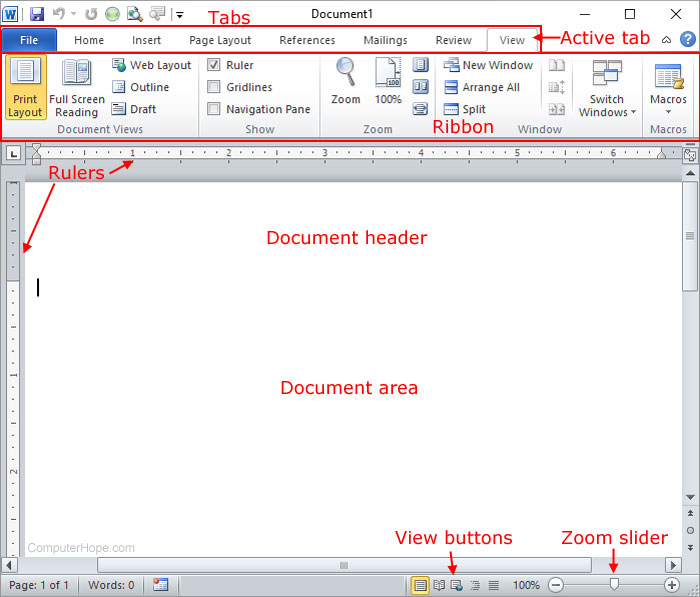

Overview of Word

In a word processor, you are presented with a blank white sheet as shown below. The text is added to the document area and after it has been inserted formatted or adjusted to your preference. Below is an example of a blank Microsoft Word window with areas of the window highlighted.

Features of a word processor

Unlike a basic plaintext editor, a word processor offers several additional features that can give your document or other text a more professional appearance. Below is a listing of popular features of a word processor.

Note

Some more advanced text editors can perform some of these functions.

- Text formatting — Changing the font, font size, font color, bold, italicizing, underline, etc.

- Copying, cutting, and pasting — Once text is entered into a document, it can be copied or cut and pasted in the current document or another document.

- Multimedia — Insert clip art, charts, images, pictures, and video into a document.

- Spelling and Grammar — Checks for spelling and grammar errors in a document.

- Adjust the layout — Capable of modifying the margins, size, and layout of a document.

- Find — Word processors give you the ability to quickly find any word or text in any size of the document.

- Search and Replace — You can use the Search and Replace feature to replace any text throughout a document.

- Indentation and lists — Set and format tabs, bullet lists, and number lists.

- Insert tables — Add tables to a document.

- Word wrap — Word processors can detect the edges of a page or container and automatically wrap the text using word wrap.

- Header and footer — Being able to adjust and change text in the header and footer of a document.

- Thesaurus — Look up alternatives to a word without leaving the program.

- Multiple windows — While working on a document, you can have additional windows with other documents for comparison or move text between documents.

- AutoCorrect — Automatically correct common errors (e.g., typing «teh» and having it autocorrected to «the»).

- Mailers and labels — Create mailers or print labels.

- Import data — Import and format data from CSV, database, or another source.

- Headers and footers — The headers and footers of a document can be customized to contain page numbers, dates, footnotes, or text for all pages or specific pages of the document.

- Merge — Word processors allow data from other documents and files to be automatically merged into a new document. For example, you can mail merge names into a letter.

- Macros — Setup macros to perform common tasks.

- Collaboration — More modern word processors help multiple people work on the same document at the same time.

Examples and top uses of a word processor

A word processor is one of the most used computer programs because of its versatility in creating a document. Below is a list of the top examples of how you could use a word processor.

- Book — Write a book.

- Document — Any text document that requires formatting.

- Help documentation — Support documentation for a product or service.

- Journal — Keep a digital version of your daily, weekly, or monthly journal.

- Letter — Write a letter to one or more people. Mail merge could also be used to automatically fill in the name, address, and other fields of the letter.

- Marketing plan — An overview of a plan to help market a new product or service.

- Memo — Create a memo for employees.

- Report — A status report or book report.

- Résumé — Create or maintain your résumé.

Examples of word processor programs

Although Microsoft Word is popular, there are other word processor programs. Below is a list of some popular word processors in alphabetical order.

- Abiword.

- Apple iWork — Pages.

- Apple TextEdit — Apple macOS included word processor.

- Corel WordPerfect.

- Dropbox Paper (online and free).

- Google Docs (online and free).

- LibreOffice -> Writer (free).

- Microsoft Office -> Microsoft Word.

- Microsoft WordPad.

- Microsoft Works (discontinued).

- SoftMaker FreeOffice -> TextMaker (free).

- OpenOffice -> Writer (free).

- SSuite -> WordGraph (free).

- Sun StarOffice (discontinued).

- Textilus (iPad and iPhone).

- Kingsoft WPS Office -> Writer (free).

Word processor advantages over a typewriter

See our typewriter page for a listing of advantages a computer with a word processor has over a typewriter.

Computer acronyms, Doc, Microsoft Word, Software terms, Untitled, Word processing, Word processor terms, WordStar, Write

Word Processing

Andrew Prestage, in Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 2003

V. Types of Word Processors

Word processors are either character based or contain a GUI. Character-based word processors do not display documents exactly as they will appear on the printed page. Some character-based word processors, however, include a “preview” capability, allowing the user to preview documents as they will appear on the printed page. This useful feature allows the user to verify that the appearance of the document matches the desired expectations.

The arrival of popular GUIs such as the Macintosh and Windows operating systems led to a change in the way word processors handled fonts. Word processors offering a GUI allow the user to see the document on the computer’s display screen exactly as it will appear after it is printed. In other words, with a GUI word processor what you see is what you get (known as the acronym WYSIWYG).

Word processor types range from simple text editors to full-featured applications. As the name implies, a simple text editor contains very limited capabilities such as the ability to enter, store for later retrieval, modify, and print text. In addition to these basic capabilities, a full-featured word processor permits users to use sophisticated text enhancement tools, check spelling and grammar, incorporate drawing tools, and perform sorting and mail merge operations. The following subsections explore examples of each of these types of word processors.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122272404001982

End-User Computing Tools

Jose Stigliano, Marco Bruni, in Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 2003

III.A. Word Processors

Word processors are tools specifically designed to process textual information, that is, information consisting primarily of words in arbitrary arrangements called documents. Word processors typically read input entered by the user through the keyboard, process the text according to the commands given by the user, and create a file containing the user’s application such as a letter, office memo, or report. Word processors support the task of writing, letting end users create, edit, store, search, and retrieve documents containing formatted text and graphics. This text, which has been produced with a word processor, provides an example of the formatting capabilities of the tool.

A variety of tasks can be automated using standard built-in functions: replacing a string of text throughout the document, generating a table of contents, or merging the text of a letter with a list of addressees for mailing purposes. These functions perform the relevant task in response to commands issued by the user. However, for tasks that need to be repeated often, issuing a command each time can be too time consuming; macros help automate the execution of repetitive tasks.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122272404000575

Positive Technology, Computing, and Design: Shaping a Future in Which Technology Promotes Psychological Well-Being

Andrea Gaggioli, … Rafael A. Calvo, in Emotions and Affect in Human Factors and Human-Computer Interaction, 2017

Active Integration

Currently, consumers buy particular word processors and email systems, not because they will support any aspect of their well-being, but because these systems help achieve their goals, complete their tasks and work.

Calvo and Peters (2014) have argued that consumers will seek future technologies that support health and well-being. This is likely to occur in the same way they currently seek healthy foods not just for sustenance or even pleasure, but as a way to live healthy and meaningful lives.

Well-being can be actively integrated into technology by designing to actively support components of well-being in an application that has a different overall goal. We need techniques that allow designers to assess the impact that different choices have on the determinant factors of well-being. A number of fields within computing can contribute to measuring this impact. For example, affective computing, the discipline that studies how computers can detect and process human emotions is increasingly part of design considerations in health and education (Riva et al., 2015a). Currently, most approaches to measure psychological well-being require interrupting users to ask about their state of mind. These interruptions are needed for the sake of measuring but themselves can be disengaging and obtrusive. Affective computing techniques can be used to reduce the amount of questioning and self-reporting by automating some of the emotion detection. Furthermore, being able to detect emotions will allow computer interfaces to better adapt to users’ states of mind and better engage, since emotional states are a most important aspect of psychological well-being.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128018514000185

Four Easy Data Hiding Exercises

Michael Raggo, Chet Hosmer, in Data Hiding, 2013

Hiding Data in Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word remains the predominant word processor standard. In fact, many people using a Mac also use Microsoft Word as their word processor. Therefore it serves us well to begin our exploration by investigating the many ways in which data can be hidden within your standard Microsoft Word document.

Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint 2007 and 2010 provide a variety of ways to hide data within the document. These include comments, personal information, watermarks, invisible content, hidden content, and custom XML data. Using the Hidden Text font options provides an easy yet amazingly effective way to hide data. First, type a standard document, and additionally input the data you’d like to hide (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Inputting Data into a Microsoft Word Document to be Hidden

Then highlight the content you’d like to hide, and right-click and choose Font. You will notice in newer version of Microsoft Word a new checkbox labeled “Hidden.” By selecting Hidden and then Save, you will notice that the highlighted text will be hidden from normal viewing (see Figures 2.2 and 2.3).

Figure 2.2. Using the Hidden Option in Microsoft Word

Figure 2.3. Microsoft Word Document after Hiding the Second Sentence

By default, hidden text is also not printed when printing the document. In order for an average user to know if there is hidden text they would need to go to File, Options, and select Display. Selecting the “Hidden Text” checkbox will enable formatting marks to alert a user to hidden text, and “Print Hidden Text” to determine if there is any hidden text (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Microsoft Word Display Options for Identifying Hidden Text

Another way to identify hidden text is to use the Inspect Document option in File => Info => Check for Issues => Inspect Document. The Inspect Document is actually a great way to identify a variety of metadata hidden within the document such as authors, comments, and possibly other personal identifiable information (PII). In addition it can be used to identify hidden text (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Using Document Inspector to Find Hidden Text and Other Metadata

Select Inspect to have the Document Inspector identify the metadata and create a report of results. In this example, the Document Inspector correctly identifies the Hidden Text and allows the user to remove it if they desire. The interesting thing here is that most people never check for the existence of Hidden Text and therefore have no idea it’s there (see Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Document Inspector Identified Hidden Text in the Document

It is important to note that the only Hidden Text identified is text hidden using the Font dialog box. For example, if text is hidden from viewing using the white text on the white background, the Document Inspector will not identify this hidden text.

The ability to hide data in the document is practical if you want to print two versions of the same document, one with the hidden data and one without. This is common for PowerPoint presentations when an individual may print the slides for the audience and print the slides with notes for the presenter.

There are a variety of other things that can be hidden within Microsoft Word 2010 Properties section, including tags, author’s name, comment, etc. (see Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7. Microsoft Word Properties and Metadata

In addition, the Properties drop-down allows access to the Advanced Properties where customs fields may be added as well (see Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Custom Tab in Microsoft Word Advanced Properties

It’s important to note that these are not displayed in the main Properties view, and therefore must be viewed by manually opening the Custom Tab in the Advanced Properties window.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978159749743500002X

UX Design Guidelines

Rex Hartson, Partha S. Pyla, in The UX Book, 2012

22.8.3 Automation Issues

Automation, in the sense we are using the term here, means moving functions and control from the user to the internal system functionality. This can result in not letting users do something the designers think they should not do or something that the designers did not think about at all. In many such cases, however, users will encounter exceptions where they really need to do it.

As an analogy, think of a word processor that will not let you save a document if it has anything marked as a spelling or grammatical error. The rationale is easy: “The user will not want to save a document that contains errors. They will want to get it right before they save it away.” You know the story, and cases almost always arise in which such a rationale proves to be wrong. Because automation and user control can be tricky, we phrase the next guideline about this kind of automation guardedly.

Avoid loss of user control from too much automation

The following examples show very small-scale cases of automation, taking control from the user. Small though they may be, they can still be frustrating to users who encounter them.

-

Example: Does the IRS know about this?

The problem in this example no longer exists in Windows Explorer, but an early version of Windows Explorer would not let you name a new folder with all uppercase letters. In particular, suppose you needed a folder for tax documents and tried to name it “IRS.” With that version of Windows, after you pressed Enter, the name would be changed to “Irs.”

So, in slight confusion, you try again but no deal. This had to be a deliberate “feature,” probably made by a software person to protect users from what appeared to be a typographic error, but that ended up being a high-handed grasping of user control.

-

Example: The John Hancock problem

Figure 22-62 shows part of a letter being composed in an early version of Microsoft Word and exhibiting another example of automation that takes away user control.

Figure 22-62. The H. John Hancock problem.

Let us just say that a user named H. John Hancock was observed typing a business letter, intending to sign it at the end as:

-

H. John Hancock

-

Sr. Vice President

Instead he got:

-

H. John Hancock

-

I.

Mr. Hancock was confused about the “I” so he backed up and typed the name again but, when he pressed Enter again, he got the same result. At first he did not know what was happening, why the “I” appeared, or how to finish the letter without getting the “I” there. At least for a few moments, the task was blocked and Mr. Hancock was frustrated.

Being a somewhat experienced user of Word, his composition of text going back to some famous early American documents, he eventually determined that the cause of the problem was that the Automatic Numbered List option was turned on as a kind of mode. At least for this occasion and this user, the Automatic numbered list option imposed too much automation and not enough user control.

That the user had difficulty understanding what was happening is due to the fact that, for this user, there was no indication of the Automatic numbered list mode. In fact, however, the system did provide quite a helpful feedback message in response to the automated action it had taken, via the “status” message of Figure 22-63, displayed at the top of the window.

Figure 22-63. If only Mr. Hancock had seen this

(screen image courtesy of Tobias Frans-Jan Theebe).

However, Mr. Hancock did not notice this feedback message because it violated the assessment guideline to “Locate feedback within the user’s focus of attention, perhaps in a pop-up dialogue box but not in a message or status line at the top or bottom of the screen.”

Help the user by automating where there is an obvious need

This section is about automation issues, but not all about avoiding automation. In some cases, automation can be helpful. The following example is about one such case.

-

Example: Sorry, off route; you lose!

No matter how good your GPS system is, as a human driver you can still make mistakes and drive off course, deviating from the route planned by the system. The Garmin GPS units are very good at helping the driver recover and get back on route. It recalculates the route from the current position immediately and automatically, without missing a beat. Recovery is so smooth and easy that it hardly seems like an error.

Before this kind of GPS, in the early days of GPS map systems for travel navigation, there was another system developed by Microsoft, called Streets and Trips. It used a GPS receiver antenna plugged into a USB port in a laptop. The unit had one extremely bad trait. When the driver got off track, the screen displayed the error message, Off Route! in a large bright red font.

Somehow you just had to know that you had to press one of the F, or function, keys to request recalculation of the route in order to recover. When you are busy contending with traffic and road signs, that is the time you would gladly have the system take control and share more of the responsibility, but you did not get that help. To be fair, this option probably was available in one of the preference settings or other menu choices, but the default behavior was not very usable and this option was not discovered very easily.

Designers of the Microsoft system may have decided to follow the design guideline to “keep the locus of control with the user.” While user control is often the best thing, there are times when it is critical for the system to take charge and do what is needed. The work context of this UX problem includes:

- ▪

-

The user is busy with other tasks that cannot be automated.

- ▪

-

It is dangerous to distract the user/driver with additional workload.

- ▪

-

Getting off track can be stressful, detracting further from the focus.

- ▪

-

Having to intervene and tell the system to recalculate the route interferes with the user’s most important task, that of driving.

Another way to interpret these twin guidelines about automation is to keep the user in control at higher task levels, where the user has done the initial planning and is driving to get somewhere. But take control from the user when the need is obvious and the user is busy.

This interpretation of the two guidelines means that, on one hand, the system does not insist on staying on this route regardless of driver actions, but quietly allows the driver to make impromptu detours. This interpretation also means that, on the other hand, the system should be expected to continue to recalculate the route to help the driver eventually reach his or her destination.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123852410000221

Analysis of quantitative and qualitative data

Kirsty Williamson, Amanda Bow, in Research Methods for Students, Academics and Professionals (Second Edition), 2002

1 Transcribe the data

This simply means to type the notes or interview tapes into a word processor making the information much more accessible and easier to analyse. In some cases, researchers have been known to analyse straight from the tapes. However, this is not recommended as it makes it very difficult to re-check easily what was said, and to categorise the data. Transcribing the data into a word processor also means that researchers can easily use computer software programs such as NVivo. If you are using NVivo or another analysis package, you would put your data into NVivo and print it out after you have finished transcribing it.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781876938420500277

CPUs

Marilyn Wolf, in High-Performance Embedded Computing (Second Edition), 2014

2.4.2 Superscalar processors

Superscalar processors issue more than one instruction per clock cycle. Unlike VLIW processors, they check for resource conflicts on the fly to determine what combinations of instructions can be issued at each step. Superscalar architectures dominate desktop and server architectures. Superscalar processors are not as common in the embedded world as in the desktop/server world. Embedded computing architectures are more likely to be judged by metrics such as operations per watt rather than raw performance.

A surprising number of embedded processors do, however, make use of superscalar instruction issue, though not as aggressively as do high-end servers. The embedded Pentium processor is a two-issue, in-order processor. It has two pipes: one for any integer operation and another for simple integer operations. We saw in Section 2.3.1 that other embedded processors also use superscalar techniques.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124105119000022

Introduction

William J. Buchanan BSc, CEng, PhD, in Software Development for Engineers, 1997

29.7 File types

Most files created have a certain purpose; for example documents from a word processor, spread-sheets, text files. The filename extension adds extra information about what type of file it is. Common filename extensions are given in Table 29.5.

Table 29.5. Example file extensions

| File extension | File type | File extension | File type |

|---|---|---|---|

| .ASC | ASCII Text | .PAS | Pascal file |

| .BAK | Backup File | .PCX | Picture file |

| .BAT | DOS Batch File | .PRN | Print File |

| .C | C language File | .SYS | System File |

| .COM | DOS Program File | .TXT | Text File |

| .EXE | DOS Executable program | .WK1 | 123 Ver 1/2 File |

| .HLP | Help File | .WK3 | 1–2–3 Ver 3 File |

| .OVL | Overlay File used by program | .TMP | Temporary File |

Test run 29.10 shows a sample DOS listing. Notice that this directory contains System Files (.SYS), DOS Commands (.COM and .EXE), Text Files (.TXT) and Help Files (.HLP). The other typical files include Basic Language Files (.BAS), Initialization Files (.INI) and Listings (.LST). Programs with the .COM, .EXE or .BAT extension can be executed.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780340700143500748

Brainstorming

Chauncey Wilson, in User Experience Re-Mastered, 2010

Analysis Techniques

Listing Ideas

All the ideas from a brainstorming session can be listed in a spreadsheet, word processor, or specialized tools like PathMaker® or Inspiration. If you have numbered the items sequentially as they were generated, your list would be chronological. To facilitate recall days, weeks, or even months later when you look through this list, you can annotate the list with clarifications and brief explanation of any unusual terms or abbreviations.

Grouping Ideas from Brainstorming

Affinity diagramming, a method for organizing data by similarity, can be used to reveal groups of related items. The number of groups that emerge from an affinity diagramming is sometimes used as a measure in brainstorming research.

Voting on Brainstorming Ideas

A group can vote on which brainstorming items should be considered further by placing adhesive dots or ink marks on the items, by removing the items from the master list, or voting online using tools like Excel, Google Spreadsheet, or SurveyMonkey.

Criteria-Based Evaluation

Criteria-based evaluation uses a decision matrix to choose the top ideas from brainstorming. The people charged with choosing which ideas will be considered further rate or rank each idea against a list of criteria like cost, ease of programming, novelty, and generality. The ratings/rankings for each idea are averaged, the ideas are sorted by the average value, and the top rated/ranked ideas are chosen for consideration (see Table 4.3). Criteria-based evaluation can be done with online survey tools if you want to expand the process of choosing the top ideas beyond the brainstorming participants.

Table 4.3. A Decision Matrix for a Criterion-Based Approach to Choosing the Best Ideas from Brainstorming

| Criterion 1 | Criterion 2 | Criterion 3 | … | Criterion N | Sum | Mean Rating/Ranking | Top Ideas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idea 1 | ||||||||

| Idea 2 | ||||||||

| Idea 3 | ||||||||

| Idea 4 | ||||||||

| Idea …. | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | |

| Idea N |

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123751140000074

Brainwriting

Chauncey Wilson, in Brainstorming and Beyond, 2013

2.6.2 Analysis Techniques

2.6.2.1 Listing Ideas

All the ideas from a brainstorming session can be listed in a spreadsheet, word processor, or specialized tools like PathMaker® or Inspiration. If you have numbered the items sequentially as they were generated, your list would be chronological. To facilitate recall, days, weeks, or even months later when you look through this list, you can annotate the list with clarifications and brief explanations of any unusual terms or abbreviations.

2.6.2.2 Grouping Ideas from Brainwriting

Affinity diagramming can be used to organize ideas into related groups. See Chapter 1 for some details on affinity diagramming.

2.6.2.3 Rating or Ranking Brainwriting Ideas

The process of brainwriting focuses on generating ideas. For some purposes, you may want to prioritize ideas against specific criteria. One simple approach you can use for prioritizing data is to apply a simple criterion (or a few criteria) to each idea and eliminate the ideas that don’t meet the criterion. A criterion would include the word “should”, for example, “the idea should be compatible with the existing user interface,” “the idea should not extend the schedule,” “the idea should be easily learned,” and “the idea should minimize errors.” You might do something like rate each idea on a 0-to-5 scale where 0 means “does not meet the criterion at all” and 5 is “meets the criterion quite well.” Once the brainwriting team has chosen items to be investigated further, individuals or team could be assigned to examine the costs and benefits of chosen items or assigned to evaluate them on specific dimensions (costs, benefits to the users, time to implement, and so on).

The nominal group rating technique described in Chapter 1 on brainstorming is sometimes used after a brainwriting session as a method for prioritizing the ideas that emerged. The facilitator would ask each member of the brainwriting team to rate privately all the ideas as a 1 (low), 2 (medium), or 3 (high). The ideas with the highest average rating would get the highest priority.

2.6.2.4 Decision Matrix

A decision matrix (sometimes called a “prioritization matrix”) uses the ideas from brainwriting and a set of criteria for rating the ideas. Some software products include a “decision matrix” where the ideas are listed on one axis and the criteria on another axis (Table 2.4). Participants would rate each item according to how well the item meets the criteria. This assumes that you are reasonably sure of the criteria for deciding which ideas to carry forward. Criteria that you might use in this table include:

Table 2.4. Layout of a Prioritization Matrix

| Idea/Criteria | Criterion 1 | Criterion 2 | Criterion 3 | Criterion … | Criterion N | Sum | Mean Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idea 1 | |||||||

| Idea 2 | |||||||

| Idea 3 | |||||||

| Idea 4 | |||||||

| Idea … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Idea n |

- •

-

Cost

- •

-

Skill required to implement the idea (you might have a great idea, but now the personnel to implement the idea)

- •

-

Technical feasibility

- •

-

Consistency with existing products

- •

-

Time to code

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124071575000026

Word Processor is a term used to describe a hardware or software which is used for input, edit, format, output, convert some text. Even first-word processors are hardware-based or provide very basic features for word processing. Modern word processors like MS Word, Libre Office, OpenOffice, etc. provide advanced features.

Word Processor History

Word processor history goes back to the 1970s. Even hardware-based word processor roots go older than that we will look at the history of the software-based word processor.

- The first-word processor software or application is created in 1976 with the name of “Electric Pencil”.

- In 1978 another word processor named WordStar boomed the word processor market and became very popular. WordStar was created for the CP/M operating system. But later with the popularity of MS-DOS the WordStar is rewritten for MS-DOS.

- In the MS-DOS era word processors, WordPerfect and Microsoft became very popular even there are some less popular word processors like XyWrite.

- The late 1980s with the innovation of laser printers typography became important with different fonts.

- Apple Macintosh computers provided the MacWrite word processor alternative from the year 1983.

- In the IBM PC era, Microsoft Word became very popular which started in 1984.

- With the popularity of the Windows operating system, Microsoft Word became a defacto word processor.

Word Processor Features and Operations

Word Processors provide different features in order to create documents. Not all of them provide advanced features but different processors provide a different level of features.

Insert text is the most basic and popular feature where text, words, and characters are typed into the document which is provided by the word processor.

Delete text is another popular operation where miss-typed or unwanted text and characters are deleted.

Copy is another popular operation where some text is copied from the given document.

Paste is similar operation to “insert text” but the text is copied from different documents, browsers, etc. into the current document.

Page size and properties can be configured accordingly for better and specific view and page type.

Search operation will search and find a given word or characters in the current word processor document.

Replace is related to the “search” operation where matched search can be changed or replaced with the given word or characters.

Print is used to print the given document into a different format like PDF or sent to into printer to get a hard copy.

File management is used to create, delete, move, rename word processor documents.

Font management is used to set and change font type which is related to the character representations.

Spell checking is another popular feature where the text content is checked again spelling or grammatical errors.

Footnotes are used to put some information about specific text or paragraph.

References is used for academic purposes.

Headers and footers are used to show some generic information like document name, page number,

Macro is used to run simple scripts to generate, calculate some data, or create actions according to the keystrokes and automatically run some functions.

Index Table is used to show list of headers and document parts with page information.

Graphics are used to show some data or information in a graphical way. The graphic can be a bar, pie, line type.

Table is used to show tabular data in a structured way which is easy to read and look.

Even a word processor provides a lot of features it provides very basic GUI in order to make the user experience easier for most of the people from different knowledge level.

Word Processor Use Cases

Even word processor is a very similar text editor it provides a lot more features and detailed configurations. Below we will list some use cases for the word processor.

- Creating reports for different businesses

- Creating homework for school and university

- Creating documentation about a product, feature or service

- Creating presentations with a lot of text, table, and graphics.

Popular Word Processor Software

Even Microsoft Word is the most popular and defacto word processor there are a lot of proprietaries and free/opensource word processors. Below we will list some of them.

Free and Open-Source Word Processors

- AbiWord

- Apache OpenOffice Writer

- Calligra Words

- EtherPad – real-time word processor

- GNU TeXmacs

- Groff

- JWPce – Japanese word processor, designed primarily for the English speaker who is reading or writing in Japanese

- KWord

- LibreOffice Writer

- LyX – TeX document processor

- OnlyOffice Desktop Editors

- Ted

- Trelby – screenplay word processor

Proprietary Word Processor

- Apple Pages, part of its iWork suite – Mac, iOS

- Applix Word – Linux

- Atlantis Word Processor – Windows

- Documents To Go – Android, iOS, Windows Mobile, Symbian

- Final Draft – screenplay/teleplay word processor

- FrameMaker

- Gobe Productive Word Processor

- Hangul (also known as HWP)

- IA Writer – Mac, iOS

- IBM SCRIPT – IBM VM/370

- IBM SCRIPT/VS – IBM z/VM or z/OS systems

- Ichitaro – Japanese word processor produced by JustSystems

- InCopy

- IntelliTalk

- iStudio Publisher – Mac

- Kingsoft Writer – Windows and Linux

- Mariner Write – Mac

- Mathematica – technical and scientific word processing

- Mellel – Mac

- Microsoft Word – Windows and Mac

- Microsoft Works Word Processor

- Microsoft Write – Windows and Mac (a stripped-down version of Word)

- Nisus Writer – Mac

- Nota Bene – Windows

- Polaris Office – Android and Windows Mobile

- PolyEdit

- QuickOffice – Android, iOS, Symbian

- Scrivener

- TechWriter – RISC OS

- TextMaker

- ThinkFree Office Write

- Ulysses – Mac, iPadOS, iOS

- WordPad – previously known as “Write” in older versions than Windows 95; has been included in all versions of Windows since Windows 1.01.

- WordPerfect

A

word processor (more formally known as document preparation system)

is a computer application used for the production (including

composition, editing, formatting, and possibly printing) of any sort

of printable material.

Word

processor may also refer to a type of stand-alone office machine,

popular in the 1970s and 1980s, combining the keyboard text-entry and

printing functions of an electric typewriter with a dedicated

processor (like a computer processor) for the editing of text.

Although features and design varied between manufacturers and models,

with new features added as technology advanced, word processors for

several years usually featured a monochrome display and the ability

to save documents on memory cards or diskettes. Later models

introduced innovations such as spell-checking programs, increased

formatting options, and dot-matrix printing. As the more versatile

combination of a personal computer and separate printer became

commonplace, most business-machine companies stopped manufacturing

the word processor as a stand-alone office machine. As of 2009 there

were only two U.S. companies, Classic and AlphaSmart, which still

made stand-alone word processors.[1] Many older machines, however,

remain in use.

Word

processors are descended from early text formatting tools (sometimes

called text justification tools, from their only real capability).

Word processing was one of the earliest applications for the personal

computer in office productivity.

Although

early word processors used tag-based markup for document formatting,

most modern word processors take advantage of a graphical user

interface providing some form of What You See Is What You Get

editing. Most are powerful systems consisting of one or more programs

that can produce any arbitrary combination of images, graphics and

text, the latter handled with type-setting capability.

Microsoft

Word is the most widely used word processing software. Microsoft

estimates that over 500,000,000 people use the Microsoft Office

suite,[2] which includes Word. Many other word processing

applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market

from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running Microsoft’s

MS-DOS operating system) and open source applications OpenOffice.org

Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors, such as

Google Docs, are a relatively new category.

Word processing

Characteristics

Word

processing typically implies the presence of text manipulation

functions that extend beyond a basic ability to enter and change

text, such as automatic generation of:

• batch

mailings using a form letter template and an address database (also

called mail merging);

• indices

of keywords and their page numbers;

• tables

of contents with section titles and their page numbers;

• tables

of figures with caption titles and their page numbers;

• cross-referencing

with section or page numbers;

• footnote

numbering;

• new

versions of a document using variables (e.g. model numbers, product

names, etc.)

Other

word processing functions include «spell checking»

(actually checks against wordlists), «grammar checking»

(checks for what seem to be simple grammar errors), and a «thesaurus»

function (finds words with similar or opposite meanings). Other

common features include collaborative editing, comments and

annotations, support for images and diagrams and internal

cross-referencing.

Word

processors can be distinguished from several other, related forms of

software:

Text

editors (modern examples of which include Notepad, BBEdit, Kate,

Gedit), were the precursors of word processors. While offering

facilities for composing and editing text, they do not format

documents. This can be done by batch document processing systems,

starting with TJ-2 and RUNOFF and still available in such systems as

LaTeX (as well as programs that implement the paged-media extensions

to HTML and CSS). Text editors are now used mainly by programmers,

website designers, computer system administrators, and, in the case

of LaTeX by mathematicians and scientists (for complex formulas and

for citations in rare languages). They are also useful when fast

startup times, small file sizes, editing speed and simplicity of

operation are preferred over formatting.

Later

desktop publishing programs were specifically designed to allow

elaborate layout for publication, but often offered only limited

support for editing. Typically, desktop publishing programs allowed

users to import text that was written using a text editor or word

processor.

Almost

all word processors enable users to employ styles, which are used to

automate consistent formatting of text body, titles, subtitles,

highlighted text, and so on.

Styles

greatly simplify managing the formatting of large documents, since

changing a style automatically changes all text that the style has

been applied to. Even in shorter documents styles can save a lot of

time while formatting. However, most help files refer to styles as an

‘advanced feature’ of the word processor, which often discourages

users from using styles regularly.

Document

statistics

Most

current word processors can calculate various statistics pertaining

to a document. These usually include:

• Character

count, word count, sentence count, line count, paragraph count, page

count.

• Word,

sentence and paragraph length.

• Editing

time.

Errors

are common; for instance, a dash surrounded by spaces — like either

of these — may be counted as a word.

Typical

usage

Word

processors have a variety of uses and applications within the

business world, home, and education.

Business

Within

the business world, word processors are extremely useful tools.

Typical uses include:

• legal

copies

• letters

and letterhead

• memos

• reference

documents

Businesses

tend to have their own format and style for any of these. Thus,

versatile word processors with layout editing and similar

capabilities find widespread use in most businesses.

Education

Many

schools have begun to teach typing and word processing to their

students, starting as early as elementary school. Typically these

skills are developed throughout secondary school in preparation for

the business world. Undergraduate students typically spend many hours

writing essays. Graduate and doctoral students continue this trend,

as well as creating works for research and publication.

Home

While

many homes have word processors on their computers, word processing

in the home tends to be educational, planning or business related,

dealing with assignments or work being completed at home, or

occasionally recreational, e.g. writing short stories. Some use word

processors for letter writing, résumé creation, and card creation.

However, many of these home publishing processes have been taken over

by desktop publishing programs specifically oriented toward home use.

which are better suited to these types of documents.

History

Toshiba

JW-10, the first word processor for the Japanese language (1971-1978

IEEE milestones)

Examples

of standalone word processor typefaces c. 1980-1981

Brother

WP-1400D editing electronic typewriter (1994)

The

term word processing was invented by IBM in the late 1960s. By 1971

it was recognized by the New York Times as a «buzz word».[3]

A 1974 Times article referred to «the brave new world of Word

Processing or W/P. That’s International Business Machines talk…

I.B.M. introduced W/P about five years ago for its Magnetic Tape

Selectric Typewriter and other electronic razzle-dazzle.»

IBM

defined the term in a broad and vague way as «the combination of

people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed

communications,» and originally used it to include dictating

machines and ordinary, manually-operated Selectric typewriters. By

the early seventies, however, the term was generally understood to

mean semiautomated typewriters affording at least some form of

electronic editing and correction, and the ability to produce perfect

«originals.» Thus, the Times headlined a 1974 Xerox product

as a «speedier electronic typewriter», but went on to

describe the product, which had no screen, as «a word processor

rather than strictly a typewriter, in that it stores copy on magnetic

tape or magnetic cards for retyping, corrections, and subsequent

printout.»

Electromechanical

paper-tape-based equipment such as the Friden Flexowriter had long

been available; the Flexowriter allowed for operations such as

repetitive typing of form letters (with a pause for the operator to

manually type in the variable information)[8], and when equipped with

an auxiliary reader, could perform an early version of «mail

merge». Circa 1970 it began to be feasible to apply electronic

computers to office automation tasks. IBM’s Mag Tape Selectric

Typewriter (MTST) and later Mag Card Selectric (MCST) were early

devices of this kind, which allowed editing, simple revision, and

repetitive typing, with a one-line display for editing single lines.

The

New York Times, reporting on a 1971 business equipment trade show,

said

The

«buzz word» for this year’s show was «word

processing,» or the use of electronic equipment, such as

typewriters; procedures and trained personnel to maximize office

efficiency. At the IBM exhibition a girl [sic] typed on an electronic

typewriter. The copy was received on a magnetic tape cassette which

accepted corrections, deletions, and additions and then produced a

perfect letter for the boss’s signature….

In

1971, a third of all working women in the United States were

secretaries, and they could see that word processing would have an

impact on their careers. Some manufacturers, according to a Times

article, urged that «the concept of ‘word processing’ could be

the answer to Women’s Lib advocates’ prayers. Word processing will

replace the ‘traditional’ secretary and give women new administrative

roles in business and industry.»

The

1970s word processing concept did not refer merely to equipment, but,

explicitly, to the use of equipment for «breaking down

secretarial labor into distinct components, with some staff members

handling typing exclusively while others supply administrative

support. A typical operation would leave most executives without

private secretaries. Instead one secretary would perform various

administrative tasks for three or more secretaries.» A 1971

article said that «Some [secretaries] see W/P as a career ladder

into management; others see it as a dead-end into the automated

ghetto; others predict it will lead straight to the picket line.»

The National Secretaries Association, which defined secretaries as

people who «can assume responsibility without direct

supervision,» feared that W/P would transform secretaries into

«space-age typing pools.» The article considered only the

organizational changes resulting from secretaries operating word

processors rather than typewriters; the possibility that word

processors might result in managers creating documents without the

intervention of secretaries was not considered—not surprising in an

era when few but secretaries possessed keyboarding skills.

In

the early 1970s, computer scientist Harold Koplow was hired by Wang

Laboratories to program calculators. One of his programs permitted a

Wang calculator to interface with an IBM Selectric typewriter, which

was at the time used to calculate and print the paperwork for auto

sales.

In

1974, Koplow’s interface program was developed into the Wang 1200

Word Processor, an IBM Selectric-based text-storage device. The

operator of this machine typed text on a conventional IBM Selectric;

when the Return key was pressed, the line of text was stored on a

cassette tape. One cassette held roughly 20 pages of text, and could

be «played back» (i.e., the text retrieved) by printing the

contents on continuous-form paper in the 1200 typewriter’s «print»

mode. The stored text could also be edited, using keys on a simple,

six-key array. Basic editing functions included Insert, Delete, Skip

(character, line), and so on.

The

labor and cost savings of this device were immediate, and remarkable:

pages of text no longer had to be retyped to correct simple errors,

and projects could be worked on, stored, and then retrieved for use

later on. The rudimentary Wang 1200 machine was the precursor of the

Wang Office Information System (OIS), introduced in 1976, whose

CRT-based system was a major breakthrough in word processing

technology. It displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated

virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as we

know them today. It was a true office machine, affordable by

organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily learned and

operated by secretarial staff.

The

Wang was not the first CRT-based machine nor were all of its

innovations unique to Wang. In the early 1970s Linolex, Lexitron and

Vydec introduced pioneering word-processing systems with CRT display

editing. A Canadian electronics company, Automatic Electronic

Systems, had introduced a product with similarities to Wang’s product

in 1973, but went into bankruptcy a year later. In 1976, refinanced

by the Canada Development Corporation, it returned to operation as

AES Data, and went on to successfully market its brand of word

processors worldwide until its demise in the mid-1980s. Its first

office product, the AES-90, combined for the first time a CRT-screen,

a floppy-disk and a microprocessor,[citation needed] that is, the

very same winning combination that would be used by IBM for its PC

seven years later. The AES-90 software was able to handle French and

English typing from the start, displaying and printing the texts

side-by-side, a Canadian government requirement. The first eight

units were delivered to the office of the then Prime Minister, Pierre

Elliot Trudeau, in February 1974. Despite these predecessors, Wang’s

product was a standout, and by 1978 it had sold more of these systems

than any other vendor.

In

the early 1980’s, AES Data Inc. introduced a networked word processor

system, called MULTIPLUS, offering multi-tasking and up to 8

workstations all sharing the resources of a centralized computer

system, a precursor to today’s networks. It followed with the

introduction of SuperPlus and SuperPlus IV systems which also offered

the CP/M operating system answering client needs. AES Data word

processors were placed side-by-side with CP/M software, like

Wordstar, to highlight ease of use.

The

phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based

machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged,

typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as

IBM, Lanier (marketing AES Data machines, re-badged), CPT, and

NBI.[13] All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with

prices in the $10,000 ballpark. Cheap general-purpose computers were

still the domain of hobbyists.

Some

of the earliest CRT-based machines used cassette tapes for

removable-memory storage until floppy diskettes became available for

this purpose — first the 8-inch floppy, then the 5-1/4-inch (drives

by Shugart Associates and diskettes by Dysan).

Printing

of documents was initially accomplished using IBM Selectric

typewriters modified for ASCII-character input. These were later

replaced by application-specific daisy wheel printers (Diablo, which

became a Xerox company, and Qume — both now defunct.) For quicker

«draft» printing, dot-matrix line printers were optional

alternatives with some word processors.

With

the rise of personal computers, and in particular the IBM PC and PC

compatibles, software-based word processors running on

general-purpose commodity hardware gradually displaced dedicated word

processors, and the term came to refer to software rather than

hardware. Some programs were modeled after particular dedicated WP

hardware. MultiMate, for example, was written for an insurance

company that had hundreds of typists using Wang systems, and spread

from there to other Wang customers. To adapt to the smaller PC

keyboard, MultiMate used stick-on labels and a large plastic clip-on

template to remind users of its dozens of Wang-like functions, using

the shift, alt and ctrl keys with the 10 IBM function keys and many

of the alphabet keys.

Other

early word-processing software required users to memorize

semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled

«copy» or «bold.» (In fact, many early PCs lacked

cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond»

for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of

hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between

dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value

added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling

that personal computers and word processing software soon became

serious competition for the dedicated machines. Word Perfect,

XyWrite, Microsoft Word, Wordstar, Workwriter and dozens of other

word processing software brands competed in the 1980s. Development of

higher-resolution monitors allowed them to provide limited WYSIWYG —

What You See Is What You Get, to the extent that typographical

features like bold and italics, indentation, justification and

margins were approximated on screen.

The

mid-to-late 1980s saw the spread of laser printers, a «typographic»

approach to word processing, and of true WYSIWYG bitmap displays with

multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word

processing program), PostScript, and graphical user interfaces

(another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor which

was commercialised in the Xerox Star product range). Standalone word

processors adapted by getting smaller and replacing their CRTs with

small character-oriented LCD displays. Some models also had

computer-like features such as floppy disk drives and the ability to

output to an external printer. They also got a name change, now being

called «electronic typewriters» and typically occupying a

lower end of the market, selling for under $200 USD.

MacWrite,

Microsoft Word and other word processing programs for the bit-mapped

Apple Macintosh screen, introduced in 1984, were probably the first

true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people until the

introduction of Microsoft Windows. Dedicated

word processors eventually became museum pieces.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Word_processor

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #