English word order is strict and rather inflexible. As there are few endings in English that show person, number, case and tense, English relies on word order to show relationships between words in a sentence.

In Russian, we rely on word endings to tell us how words interact in a sentence. You probably remember the example that was made up by Academician L.V. Scherba in order to show the work of endings and suffixes in Russian. (No English translation for this example.) Everything we need to know about the interaction of the characters in this Russian sentence, we learn from the endings and suffixes.

English nouns do not have any case endings (only personal pronouns have some case endings), so it is mostly the word order that tells us where things are in a sentence, and how they interact. Compare:

The dog sees the cat.

The cat sees the dog.

The subject and the object in these sentences are completely the same in form. How do you know who sees whom? The rules of English word order tell us about it.

Word order patterns in English sentences

A sentence is a group of words containing a subject and a predicate and expressing a complete thought. Word order arranges separate words into sentences in a certain way and indicates where to find the subject, the predicate, and the other parts of the sentence. Word order and context help to identify the meanings of individual words.

English sentences are divided into declarative sentences (statements), interrogative sentences (questions), imperative sentences (commands, requests), and exclamatory sentences. Declarative sentences are the most common type of sentences. Word order in declarative sentences serves as a basis for word order in the other types of sentences.

The main minimal pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE. Examples: Maria works. Time flies.

The most common pattern of basic word order in English declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE + OBJECT, often called SUBJECT + VERB + OBJECT (SVO) in English linguistic sources. Examples: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

An ordinary declarative sentence containing all five parts of the sentence, for example, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», has the following word order:

The subject is placed at the beginning of the sentence before the predicate; the predicate follows the subject; the object is placed after the predicate; the adverbial modifier is placed after the object (or after the verb if there is no object); the attribute (an adjective) is placed before its noun (attributes in the form of a noun with a preposition are placed after their nouns).

Verb type and word order

Word order after the verb usually depends on the type of verb (transitive verb, intransitive verb, linking verb). (Types of verbs are described in Verbs Glossary of Terms in the section Grammar.)

Transitive verbs

Transitive verbs require a direct object: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (See Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the section Miscellany.)

Some transitive verbs (e.g., bring, give, send, show, tell) are often followed by two objects: an indirect object and a direct object. For example: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Such sentences often have the following word order: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Intransitive verbs

Intransitive verbs do not take a direct object. Intransitive verbs may stand alone or may be followed by an adverbial modifier (an adverb, a phrase) or by a prepositional object.

Examples of sentences with intransitive verbs: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Linking verbs

Linking verbs (e.g., be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) are followed by a complement. The verb BE is the main linking verb. It is often followed by a noun or an adjective: He is a doctor. He is kind. (See The Verb BE in the section Grammar.)

Other linking verbs are usually followed by an adjective (the linking verb «become» may also be followed by a noun): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

The material below describes standard word order in different types of sentences very briefly. The other materials of the section Word Order give a more detailed description of standard word order and its peculiarities in different types of sentences.

Declarative sentences

Subject + predicate (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Maria works.

Tom is a writer.

This book is interesting.

I live in Moscow.

Tom writes short stories for children.

He talked to Anna yesterday.

My son bought three history books.

He is writing a report now.

(See Word Order in Statements in the section Grammar.)

Interrogative sentences

Interrogative sentences include general questions, special questions, alternative questions, and tag questions. (See Word Order in Questions in the section Grammar.)

General questions

Auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Do you live here? – Yes, I do.

Does he speak English? – Yes, he does.

Did you go to the concert? – No, I didn’t.

Is he writing a report now? – Yes, he is.

Have you seen this film? – No, I haven’t.

Special questions

Question word + auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier):

Where does he live? – He lives in Paris.

What are you writing now? – I’m writing a new story.

When did they visit Mexico? – They visited Mexico five years ago.

What is your name? – My name is Alex.

How old are you? – I’m 24 years old.

Alternative questions

Alternative questions are questions with a choice. Word order before «or» is the same as in general questions.

Is he a teacher or a doctor? – He is a teacher.

Does he live in Paris or in Rome? – He lives in Rome.

Are you writing a report or a letter? – I’m writing a report.

Would you like coffee or tea? – Tea, please.

Tag questions

Tag questions consist of two parts. The first part has the same word order as statements; the second part is a short general question (the tag).

He is a teacher, isn’t he? – Yes, he is.

He lives here, doesn’t he? – No, he doesn’t.

You went there, didn’t you? – Yes, I did.

They haven’t seen this film, have they? – No, they haven’t.

Imperative sentences

Imperative sentences (commands, instructions, requests) have the same word order as statements, but the subject (you) is usually omitted. (See Word Order in Commands in the section Grammar.)

Go to your room.

Listen to the story.

Please sit down.

Give me that book, please.

Negative imperative sentences are formed with the help of the auxiliary verb «don’t».

Don’t cry.

Don’t wait for me.

Requests

Polite requests in English are usually in the form of general questions using «could, may, will, would». (See Word Order in Requests in the section Grammar.)

Could you help me, please?

May I speak to Tom, please?

Will you please ask him to call me?

Would you mind helping me with this report?

Exclamatory sentences

Exclamatory sentences have the same word order as statements (i.e., the subject is before the predicate).

She is a great singer!

It is an excellent opportunity!

How well he knows history!

What a beautiful town this is!

How strange it is!

In some types of exclamatory sentences, the subject (it, this, that) and the linking verb are often omitted.

What a pity!

What a beautiful present!

What beautiful flowers!

How strange!

Simple, compound, and complex sentences

English sentences are divided into simple sentences, compound sentences and complex sentences depending on the number and kind of clauses that they contain.

The term «clause»

The word «clause» is translated into Russian in the same way as the word «sentence». The word «clause» refers to a group of words containing a subject and a predicate, usually in a compound or complex sentence.

There are two kinds of clauses: independent and dependent. An independent clause can be a separate sentence (e.g., a simple sentence).

The main clause in a complex sentence and clauses in a compound sentence are independent clauses; the subordinate clause is a dependent clause.

Simple sentences

A simple sentence consists of one independent clause, has a subject and a predicate and may also have other parts of the sentence (an object, an adverbial modifier, an attribute).

Life goes on.

I’m busy.

Anton is sleeping.

She works in a hotel.

You don’t know him.

He wrote a letter to the manager.

Compound sentences

A compound sentence consists of two (or more) independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, or). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

Maria lives in Moscow, and her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

He wrote a letter to the manager, but the manager didn’t answer.

Her children may watch TV here, or they may play in the yard.

Sentences connected by «and» may be connected without a conjunction. In such cases, a semicolon is used between them.

Maria lives in Moscow; her friend Elizabeth lives in New York.

Complex sentences

A complex sentence consists of the main clause and the subordinate clause connected by a subordinating conjunction (e.g., that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Each clause has a subject and a predicate.

I told him that I didn’t know anything about their plans.

Betty has been working as a secretary since she moved to California.

Tom went to bed early because he was very tired.

If he comes back before ten, ask him to call me, please.

(Different types of subordinate clauses are described in Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar.)

Базовый порядок слов

Порядок слов в английском языке строгий и довольно негибкий. Так как в английском языке мало окончаний, показывающих лицо, число, падеж и время, английский язык полагается на порядок слов для показа отношений между словами в предложении.

В русском языке мы полагаемся на окончания, чтобы понять, как слова взаимодействуют в предложении. Вы, наверное, помните пример, который придумал академик Л.В. Щерба для того, чтобы показать работу окончаний и суффиксов в русском языке: Глокая куздра штеко будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. (Нет английского перевода для этого примера.) Все, что нам нужно знать о взаимодействии героев в этом русском предложении, мы узнаём из окончаний и суффиксов.

Английские существительные не имеют падежных окончаний (только личные местоимения имеют падежные окончания), поэтому в основном именно порядок слов сообщает нам, где что находится в предложении и как они взаимодействуют. Сравните:

Собака видит кошку.

Кошка видит собаку.

Подлежащее и дополнение в этих (английских) предложениях полностью одинаковы по форме. Как узнать, кто кого видит? Правила английского порядка слов говорят нам об этом.

Модели порядка слов в английских предложениях

Предложение – это группа слов, содержащая подлежащее и сказуемое и выражающая законченную мысль. Порядок слов организует отдельные слова в предложения определённым образом и указывает, где найти подлежащее, сказуемое и другие члены предложения. Порядок слов и контекст помогают выявить значения отдельных слов.

Английские предложения делятся на повествовательные предложения (утверждения), вопросительные предложения (вопросы), повелительные предложения (команды, просьбы) и восклицательные предложения. Повествовательные предложения – самый распространённый тип предложений. Порядок слов в повествовательных предложениях служит основой для порядка слов в других типах предложений.

Основная минимальная модель базового порядка слов в английских повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое. Примеры: Maria works. Time flies.

Наиболее распространённая модель базового порядка слов в повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое + дополнение, часто называемая подлежащее + глагол + дополнение в английских лингвистических источниках. Примеры: Tom writes stories. The dog sees the cat.

Обычное повествовательное предложение, содержащее все пять членов предложения, например, «Mike read an interesting story yesterday», имеет следующий порядок слов:

Подлежащее ставится в начале предложения перед сказуемым; сказуемое следует за подлежащим; дополнение ставится после сказуемого; обстоятельство ставится после дополнения (или после глагола, если дополнения нет); определение (прилагательное) ставится перед своим существительным (определения в виде существительного с предлогом ставятся после своих существительных).

Тип глагола и порядок слов

Порядок слов после глагола обычно зависит от типа глагола (переходный глагол, непереходный глагол, глагол-связка). (Типы глаголов описываются в материале «Verbs Glossary of Terms» в разделе Grammar.)

Переходные глаголы

Переходные глаголы требуют прямого дополнения: Tom writes stories. Denis likes films. Anna bought a book. I saw him yesterday. (См. Transitive and Intransitive Verbs в разделе Miscellany.)

За некоторыми переходными глаголами (например, bring, give, send, show, tell) часто следуют два дополнения: косвенное дополнение и прямое дополнение. Например: He gave me the key. She sent him a letter. Такие предложения часто имеют следующий порядок слов: He gave the key to me. She sent a letter to him.

Непереходные глаголы

Непереходные глаголы не принимают прямое дополнение. За непереходными глаголами может ничего не стоять, или за ними может следовать обстоятельство (наречие, фраза) или предложное дополнение.

Примеры предложений с непереходными глаголами: Maria works. He is sleeping. She writes very quickly. He went there yesterday. They live in a small town. He spoke to the manager. I thought about it. I agree with you.

Глаголы-связки

За глаголами-связками (например, be, become, feel, get, grow, look, seem) следует комплемент (именная часть сказуемого). Глагол BE – главный глагол-связка. За ним часто следует существительное или прилагательное: He is a doctor. He is kind. (См. The Verb BE в разделе Grammar.)

За другими глаголами-связками обычно следует прилагательное (за глаголом-связкой «become» может также следовать существительное): He became famous. She became a doctor. He feels happy. It is getting cold. It grew dark. She looked sad. He seems tired.

Материал ниже описывает стандартный порядок слов в различных типах предложений очень кратко. Другие материалы раздела Word Order дают более подробное описание стандартного порядка слов и его особенностей в различных типах предложений.

Повествовательные предложения

Подлежащее + сказуемое (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Мария работает.

Том – писатель.

Эта книга интересная.

Я живу в Москве.

Том пишет короткие рассказы для детей.

Он говорил с Анной вчера.

Мой сын купил три книги по истории.

Он пишет доклад сейчас.

(См. Word Order in Statements в разделе Grammar.)

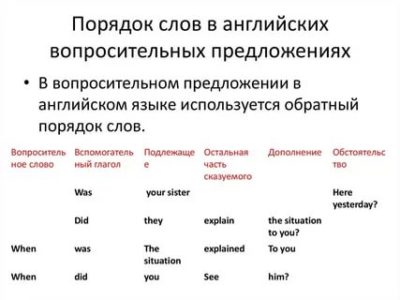

Вопросительные предложения

Вопросительные предложения включают в себя общие вопросы, специальные вопросы, альтернативные вопросы и разъединённые вопросы. (См. Word Order in Questions в разделе Grammar.)

Общие вопросы

Вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Вы живёте здесь? – Да (живу).

Он говорит по-английски? – Да (говорит).

Вы ходили на концерт? – Нет (не ходил).

Он пишет доклад сейчас? – Да (пишет).

Вы видели этот фильм? – Нет (не видел).

Специальные вопросы

Вопросительное слово + вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство):

Где он живёт? – Он живёт в Париже.

Что вы сейчас пишете? – Я пишу новый рассказ.

Когда они посетили Мексику? – Они посетили Мексику пять лет назад.

Как вас зовут? – Меня зовут Алекс.

Сколько вам лет? – Мне 24 года.

Альтернативные вопросы

Альтернативные вопросы – это вопросы с выбором. Порядок слов до «or» такой же, как в общих вопросах.

Он учитель или врач? – Он учитель.

Он живёт в Париже или в Риме? – Он живёт в Риме.

Вы пишете доклад или письмо? – Я пишу доклад.

Хотите кофе или чай? – Чай, пожалуйста.

Разъединенные вопросы

Разъединённые вопросы состоят из двух частей. Первая часть имеет такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения; вторая часть – краткий общий вопрос.

Он учитель, не так ли? – Да (он учитель).

Он живёт здесь, не так ли? – Нет (не живёт).

Вы ходили туда, не так ли? – Да (ходил).

Они не видели этот фильм, не так ли? – Нет (не видели).

Повелительные предложения

Повелительные предложения (команды, инструкции, просьбы) имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения, но подлежащее (вы) обычно опускается. (См. Word Order in Commands в разделе Grammar.)

Идите в свою комнату.

Слушайте рассказ.

Пожалуйста, садитесь.

Дайте мне ту книгу, пожалуйста.

Отрицательные повелительные предложения образуются с помощью вспомогательного глагола «don’t».

Не плачь.

Не ждите меня.

Просьбы

Вежливые просьбы в английском языке обычно в форме вопросов с использованием «could, may, will, would». (См. Word Order in Requests в разделе Grammar.)

Не могли бы вы помочь мне, пожалуйста?

Можно мне поговорить с Томом, пожалуйста?

Попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

Вы не возражали бы помочь мне с этим докладом?

Восклицательные предложения

Восклицательные предложения имеют такой же порядок слов, как повествовательные предложения (т.е. подлежащее перед сказуемым).

Она отличная певица!

Это отличная возможность!

Как хорошо он знает историю!

Какой это прекрасный город!

Как это странно!

В некоторых типах восклицательных предложений подлежащее (it, this, that) и глагол-связка часто опускаются.

Какая жалость!

Какой прекрасный подарок!

Какие прекрасные цветы!

Как странно!

Простые, сложносочиненные и сложноподчиненные предложения

Английские предложения делятся на простые предложения, сложносочинённые предложения и сложноподчинённые предложения в зависимости от количества и вида предложений, которые они содержат.

Термин «clause»

Слово «clause» переводится на русский язык так же, как слово «sentence». Слово «clause» имеет в виду группу слов, содержащую подлежащее и сказуемое, обычно в сложносочинённом или сложноподчинённом предложении.

Есть два вида «clauses»: независимые и зависимые. Независимое предложение может быть отдельным предложением (например, простое предложение).

Главное предложение в сложноподчинённом предложении и предложения в сложносочинённом предложении – независимые предложения; придаточное предложение – зависимое предложение.

Простые предложения

Простое предложение состоит из одного независимого предложения, имеет подлежащее и сказуемое и может также иметь другие члены предложения (дополнение, обстоятельство, определение).

Жизнь продолжается.

Я занят.

Антон спит.

Она работает в гостинице.

Вы не знаете его.

Он написал письмо менеджеру.

Сложносочиненные предложения

Сложносочинённое предложение состоит из двух (или более) независимых предложений, соединённых соединительным союзом (например, and, but, or). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Мария живёт в Москве, а её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Он написал письмо менеджеру, но менеджер не ответил.

Её дети могут посмотреть телевизор здесь, или они могут поиграть во дворе.

Предложения, соединённые союзом «and», могут быть соединены без союза. В таких случаях между ними ставится точка с запятой.

Мария живёт в Москве; её подруга Элизабет живёт в Нью-Йорке.

Сложноподчиненные предложения

Сложноподчинённое предложение состоит из главного предложения и придаточного предложения, соединённых подчинительным союзом (например, that, after, when, since, because, if, though). Каждое предложение имеет подлежащее и сказуемое.

Я сказал ему, что я ничего не знаю об их планах.

Бетти работает секретарём с тех пор, как она переехала в Калифорнию.

Том лёг спать рано, потому что он очень устал.

Если он вернётся до десяти, попросите его позвонить мне, пожалуйста.

(Различные типы придаточных предложений описываются в материале «Word Order in Complex Sentences» в разделе Grammar.)

Можно ли использовать вопросительный порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях? Как построить предложение, если в нем нет подлежащего? Об этих и других нюансах читайте в нашей статье.

Прямой порядок слов в английских предложениях

Утвердительные предложения

В английском языке основной порядок слов можно описать формулой SVO: subject – verb – object (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение).

Mary reads many books. — Мэри читает много книг.

Подлежащее — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит в начале предложения (кто? — Mary).

Сказуемое — это глагол, который стоит после подлежащего (что делает? — reads).

Дополнение — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит после глагола (что? — books).

В английском отсутствуют падежи, поэтому необходимо строго соблюдать основной порядок слов, так как часто это единственное, что указывает на связь между словами.

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| My mum | loves | soap operas. | Моя мама любит мыльные оперы. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Салли нашла свои ключи. |

| I | remember | you. | Я помню тебя. |

Глагол to be в утвердительных предложениях

Как правило, английское предложение не обходится без сказуемого, выраженного глаголом. Так как в русском можно построить предложение без глагола, мы часто забываем о нем в английском. Например:

Mary is a teacher. — Мэри — учительница. (Мэри является учительницей.)

I’m scared. — Мне страшно. (Я являюсь напуганной.)

Life is unfair. — Жизнь несправедлива. (Жизнь является несправедливой.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — Моему младшему брату десять лет. (Моему младшему брату есть десять лет.)

His friends are from Spain. — Его друзья из Испании. (Его друзья происходят из Испании.)

The vase is on the table. — Ваза на столе. (Ваза находится/стоит на столе.)

Подведем итог, глагол to be в переводе на русский может означать:

- быть/есть/являться;

- находиться / пребывать (в каком-то месте или состоянии);

- существовать;

- происходить (из какой-то местности).

Если вы не уверены, нужен ли to be в вашем предложении в настоящем времени, то переведите предложение в прошедшее время: я на работе — я была на работе. Если в прошедшем времени появляется глагол-связка, то и в настоящем он необходим.

Предложения с there is / there are

Когда мы хотим сказать, что что-то где-то есть или чего-то где-то нет, то нам нужно придерживаться конструкции there + to be в начале предложения.

There is grass in the yard, there is wood on the grass. — На дворе — трава, на траве — дрова.

Если в таких типах предложений мы не используем конструкцию there is / there are, то по-английски подобные предложения будут звучать менее естественно:

There are a lot of people in the room. — В комнате много людей. (естественно)

A lot of people are in the room. — Много людей находится в комнате. (менее естественно)

Обратите внимание, предложения с there is / there are, как правило, переводятся на русский с конца предложения.

Еще конструкция there is / there are нужна, чтобы соблюсти основной порядок слов — SVO (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение):

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| There | is | too much sugar in my tea. | В моем чае слишком много сахара. |

Более подробно о конструкции there is / there are можно прочитать в статье «Грамматика английского языка для начинающих, часть 3».

Местоимение it

Мы, как носители русского языка, в английских предложениях забываем не только про сказуемое, но и про подлежащее. Особенно сложно понять, как перевести на английский подобные предложения: Темнеет. Пора вставать. Приятно было пообщаться. В английском языке во всех этих предложениях должно стоять подлежащее, роль которого будет играть вводное местоимение it. Особенно важно его не забыть, если мы говорим о погоде.

It’s getting dark. — Темнеет.

It’s time to get up. — Пора вставать.

It was nice to talk to you. — Приятно было пообщаться.

Хотите научиться грамотно говорить по-английски? Тогда записывайтесь на курс практической грамматики.

Отрицательные предложения

Если предложение отрицательное, то мы ставим отрицательную частицу not после:

- вспомогательного глагола (auxiliary verb);

- модального глагола (modal verb).

| Подлежащее | Вспомогательный/Модальный глагол | Частица not | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sally | has | not | found | her keys. | Салли не нашла свои ключи. |

| My mum | does | not | love | soap operas. | Моя мама не любит мыльные оперы. |

| He | could | not | save | his reputation. | Он не мог спасти свою репутацию |

| I | will | not | be | yours. | Я не буду твоей. |

Если в предложении единственный глагол — to be, то ставим not после него.

| Подлежащее | Глагол to be | Частица not | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | is | not | an engineer. | Питер не инженер. |

| I | was | not | at work yesterday. | Я не была вчера на работе. |

| Her friends | were | not | polite enough. | Ее друзья были недостаточно вежливы. |

Порядок слов в вопросах

Для начала скажем, что вопросы бывают двух основных типов:

- закрытые вопросы (вопросы с ответом «да/нет»);

- открытые вопросы (вопросы, на которые можно дать развернутый ответ).

Закрытые вопросы

Чтобы построить вопрос «да/нет», нужно поставить модальный или вспомогательный глагол в начало предложения. Получится следующая структура: вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое. Следующие примеры вам помогут понять, как утвердительное предложение преобразовать в вопросительное.

She goes to the gym on Mondays. — Она ходит в зал по понедельникам.

Does she go to the gym on Mondays? — Ходит ли она в зал по понедельникам?

He can speak English fluently. — Он умеет бегло говорить по-английски.

Can he speak English fluently? — Умеет ли он бегло говорить по-английски?

Simon has always loved Katy. — Саймон всегда любил Кэти.

Has Simon always loved Katy? — Всегда ли Саймон любил Кэти?

Обратите внимание! Если в предложении есть только глагол to be, то в Present Simple и Past Simple мы перенесем его в начало предложения.

She was at home all day yesterday. — Она была дома весь день.

Was she at home all day yesterday? — Она была дома весь день?

They’re tired. — Они устали.

Are they tired? — Они устали?

Открытые вопросы

В вопросах открытого типа порядок слов такой же, только в начало предложения необходимо добавить вопросительное слово. Тогда структура предложения будет следующая: вопросительное слово – вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое.

Перечислим вопросительные слова: what (что?, какой?), who (кто?), where (где?, куда?), why (почему?, зачем?), how (как?), when (когда?), which (который?), whose (чей?), whom (кого?, кому?).

He was at work on Monday. — В понедельник он весь день был на работе.

Where was he on Monday? — Где он был в понедельник?

She went to the cinema yesterday. — Она вчера ходила в кино.

Where did she go yesterday? — Куда она вчера ходила?

My father watches Netflix every day. — Мой отец каждый день смотрит Netflix.

How often does your father watch Netflix? — Как часто твой отец смотрит Netflix?

Вопросы к подлежащему

В английском есть такой тип вопросов, как вопросы к подлежащему. У них порядок слов такой же, как и в утвердительных предложениях, только в начале будет стоять вопросительное слово вместо подлежащего. Сравните:

Who do you love? — Кого ты любишь? (подлежащее you)

Who loves you? — Кто тебя любит? (подлежащее who)

Whose phone did she find two days ago? — Чей телефон она вчера нашла? (подлежащее she)

Whose phone is ringing? — Чей телефон звонит? (подлежащее whose phone)

What have you done? — Что ты наделал? (подлежащее you)

What happened? — Что случилось? (подлежащее what)

Обратите внимание! После вопросительных слов who и what необходимо использовать глагол в единственном числе.

Who lives in this mansion? — Кто живет в этом особняке?

What makes us human? — Что делает нас людьми?

Косвенные вопросы

Если вам нужно что-то узнать и вы хотите звучать более вежливо, то можете начать свой вопрос с таких фраз, как: Could you tell me… ? (Можете подсказать… ?), Can you please help… ? (Можете помочь… ?) Далее задавайте вопрос, но используйте прямой порядок слов.

Could you tell me where is the post office is? — Не могли бы вы мне подсказать, где находится почта?

Do you know what time does the store opens? — Вы знаете, во сколько открывается магазин?

Если в косвенный вопрос мы трансформируем вопрос типа «да/нет», то перед вопросительной частью нам понадобится частица «ли» — if или whether.

Do you like action films? — Тебе нравятся боевики?

I wonder if/whether you like action films. — Мне интересно узнать, нравятся ли тебе экшн-фильмы.

Другие члены предложения

Прилагательное в английском стоит перед существительным, а наречие обычно — в конце предложения.

Grace Kelly was a beautiful woman. — Грейс Келли была красивой женщиной.

Andy reads well. — Энди хорошо читает.

Обстоятельство, как правило, стоит в конце предложения. Оно отвечает на вопросы как?, где?, куда?, почему?, когда?

There was no rain last summer. — Прошлым летом не было дождя.

The town hall is in the city center. — Администрация находится в центре города.

Если в предложении несколько обстоятельств, то их надо ставить в следующем порядке:

| Подлежащее + сказуемое | Обстоятельство (как?) | Обстоятельство (где?) | Обстоятельство (когда?) | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergie didn’t perform | very well | at the concert | two years ago. | Ферги не очень хорошо выступила на концерте два года назад. |

Чтобы подчеркнуть, когда или где что-то случилось, мы можем поставить обстоятельство места или времени в начало предложения:

Last Christmas I gave you my heart. But the very next day you gave it away. This year, to save me from tears, I’ll give it to someone special. — Прошлым Рождеством я подарил тебе свое сердце. Но уже на следующий день ты отдала его обратно. В этом году, чтобы больше не горевать, я подарю его кому-нибудь другому.

Если вы хотите преодолеть языковой барьер и начать свободно общаться с иностранцами, записывайтесь на разговорный курс английского.

Надеемся, эта статья была вам полезной и вы разобрались, как строить предложения в английском языке. Предлагаем пройти небольшой тест для закрепления темы.

Тест по теме «Порядок слов в английском предложении, часть 1»

© 2023 englex.ru, копирование материалов возможно только при указании прямой активной ссылки на первоисточник.

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how different languages employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic sub-domains are also of interest. The primary word orders that are of interest are

- the constituent order of a clause, namely the relative order of subject, object, and verb;

- the order of modifiers (adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives, and adjuncts) in a noun phrase;

- the order of adverbials.

Some languages use relatively fixed word order, often relying on the order of constituents to convey grammatical information. Other languages—often those that convey grammatical information through inflection—allow more flexible word order, which can be used to encode pragmatic information, such as topicalisation or focus. However, even languages with flexible word order have a preferred or basic word order,[1] with other word orders considered «marked».[2]

Constituent word order is defined in terms of a finite verb (V) in combination with two arguments, namely the subject (S), and object (O).[3][4][5][6] Subject and object are here understood to be nouns, since pronouns often tend to display different word order properties.[7][8] Thus, a transitive sentence has six logically possible basic word orders:

- about half of the world’s languages deploy subject–object–verb order (SOV);

- about one-third of the world’s languages deploy subject–verb–object order (SVO);

- a smaller fraction of languages deploy verb–subject–object (VSO) order;

- the remaining three arrangements are rarer: verb–object–subject (VOS) is slightly more common than object–verb–subject (OVS), and object–subject–verb (OSV) is the rarest by a significant margin.[9]

Constituent word orders[edit]

These are all possible word orders for the subject, object, and verb in the order of most common to rarest (the examples use «she» as the subject, «loves» as the verb, and «him» as the object):

- SOV is the order used by the largest number of distinct languages; languages using it include Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Turkish, the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages. Some, like Persian, Latin and Quechua, have SOV normal word order but conform less to the general tendencies of other such languages. A sentence glossing as «She him loves» would be grammatically correct in these languages.

- SVO languages include English, Spanish, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian,[10] the Chinese languages and Swahili, among others. «She loves him.»

- VSO languages include Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, the Insular Celtic languages, and Hawaiian. «Loves she him.»

- VOS languages include Fijian and Malagasy. «Loves him she.»

- OVS languages include Hixkaryana. «Him loves she.»

- OSV languages include Xavante and Warao. «Him she loves.»

Sometimes patterns are more complex: some Germanic languages have SOV in subordinate clauses, but V2 word order in main clauses, SVO word order being the most common. Using the guidelines above, the unmarked word order is then SVO.

Many synthetic languages such as Latin, Greek, Persian, Romanian, Assyrian, Assamese, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Japanese, Finnish, Arabic and Basque have no strict word order; rather, the sentence structure is highly flexible and reflects the pragmatics of the utterance. However, also in languages of this kind there is usually a pragmatically neutral constituent order that is most commonly encountered in each language.

Topic-prominent languages organize sentences to emphasize their topic–comment structure. Nonetheless, there is often a preferred order; in Latin and Turkish, SOV is the most frequent outside of poetry, and in Finnish SVO is both the most frequent and obligatory when case marking fails to disambiguate argument roles. Just as languages may have different word orders in different contexts, so may they have both fixed and free word orders. For example, Russian has a relatively fixed SVO word order in transitive clauses, but a much freer SV / VS order in intransitive clauses.[citation needed] Cases like this can be addressed by encoding transitive and intransitive clauses separately, with the symbol «S» being restricted to the argument of an intransitive clause, and «A» for the actor/agent of a transitive clause. («O» for object may be replaced with «P» for «patient» as well.) Thus, Russian is fixed AVO but flexible SV/VS. In such an approach, the description of word order extends more easily to languages that do not meet the criteria in the preceding section. For example, Mayan languages have been described with the rather uncommon VOS word order. However, they are ergative–absolutive languages, and the more specific word order is intransitive VS, transitive VOA, where the S and O arguments both trigger the same type of agreement on the verb. Indeed, many languages that some thought had a VOS word order turn out to be ergative like Mayan.

Distribution of word order types[edit]

Every language falls under one of the six word order types; the unfixed type is somewhat disputed in the community, as the languages where it occurs have one of the dominant word orders but every word order type is grammatically correct.

The table below displays the word order surveyed by Dryer. The 2005 study[11] surveyed 1228 languages, and the updated 2013 study[8] investigated 1377 languages. Percentage was not reported in his studies.

| Word Order | Number (2005) | Percentage (2005) | Number (2013) | Percentage (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 497 | 40.5% | 565 | 41.0% |

| SVO | 435 | 35.4% | 488 | 35.4% |

| VSO | 85 | 6.9% | 95 | 6.9% |

| VOS | 26 | 2.1% | 25 | 1.8% |

| OVS | 9 | 0.7% | 11 | 0.8% |

| OSV | 4 | 0.3% | 4 | 0.3% |

| Unfixed | 172 | 14.0% | 189 | 13.7% |

Hammarström (2016)[12] calculated the constituent orders of 5252 languages in two ways. His first method, counting languages directly, yielded results similar to Dryer’s studies, indicating both SOV and SVO have almost equal distribution. However, when stratified by language families, the distribution showed that the majority of the families had SOV structure, meaning that a small number of families contain SVO structure.

| Word Order | No. of Languages | Percentage | No. of Families | Percentage[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 2275 | 43.3% | 239 | 56.6% |

| SVO | 2117 | 40.3% | 55 | 13.0% |

| VSO | 503 | 9.5% | 27 | 6.3% |

| VOS | 174 | 3.3% | 15 | 3.5% |

| OVS | 40 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.7% |

| OSV | 19 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Unfixed | 124 | 2.3% | 26 | 6.1% |

Functions of constituent word order[edit]

Fixed word order is one out of many ways to ease the processing of sentence semantics and reducing ambiguity. One method of making the speech stream less open to ambiguity (complete removal of ambiguity is probably impossible) is a fixed order of arguments and other sentence constituents. This works because speech is inherently linear. Another method is to label the constituents in some way, for example with case marking, agreement, or another marker. Fixed word order reduces expressiveness but added marking increases information load in the speech stream, and for these reasons strict word order seldom occurs together with strict morphological marking, one counter-example being Persian.[1]

Observing discourse patterns, it is found that previously given information (topic) tends to precede new information (comment). Furthermore, acting participants (especially humans) are more likely to be talked about (to be topic) than things simply undergoing actions (like oranges being eaten). If acting participants are often topical, and topic tends to be expressed early in the sentence, this entails that acting participants have a tendency to be expressed early in the sentence. This tendency can then grammaticalize to a privileged position in the sentence, the subject.

The mentioned functions of word order can be seen to affect the frequencies of the various word order patterns: The vast majority of languages have an order in which S precedes O and V. Whether V precedes O or O precedes V, however, has been shown to be a very telling difference with wide consequences on phrasal word orders.[13]

Semantics of word order[edit]

In many languages, standard word order can be subverted in order to form questions or as a means of emphasis. In languages such as O’odham and Hungarian, which are discussed below, almost all possible permutations of a sentence are grammatical, but not all of them are used.[14] In languages such as English and German, word order is used as a means of turning declarative into interrogative sentences:

A: ‘Wen liebt Kate?’ / ‘Kate liebt wen?’ [Whom does Kate love? / Kate loves whom?] (OVS/SVO)

B: ‘Sie liebt Mark’ / ‘Mark ist der, den sie liebt’ [She loves Mark / It is Mark whom she loves.] (SVO/OSV)

C: ‘Liebt Kate Mark?’ [Does Kate love Mark?] (VSO)

In (A), the first sentence shows the word order used for wh-questions in English and German. The second sentence is an echo question; it would only be uttered after receiving an unsatisfactory or confusing answer to a question. One could replace the word wen [whom] (which indicates that this sentence is a question) with an identifier such as Mark: ‘Kate liebt Mark?’ [Kate loves Mark?]. In that case, since no change in word order occurs, it is only by means of stress and tone that we are able to identify the sentence as a question.

In (B), the first sentence is declarative and provides an answer to the first question in (A). The second sentence emphasizes that Kate does indeed love Mark, and not whomever else we might have assumed her to love. However, a sentence this verbose is unlikely to occur in everyday speech (or even in written language), be it in English or in German. Instead, one would most likely answer the echo question in (A) simply by restating: Mark!. This is the same for both languages.

In yes–no questions such as (C), English and German use subject-verb inversion. But, whereas English relies on do-support to form questions from verbs other than auxiliaries, German has no such restriction and uses inversion to form questions, even from lexical verbs.

Despite this, English, as opposed to German, has very strict word order. In German, word order can be used as a means to emphasize a constituent in an independent clause by moving it to the beginning of the sentence. This is a defining characteristic of German as a V2 (verb-second) language, where, in independent clauses, the finite verb always comes second and is preceded by one and only one constituent. In closed questions, V1 (verb-first) word order is used. And lastly, dependent clauses use verb-final word order. However, German cannot be called an SVO language since no actual constraints are imposed on the placement of the subject and object(s), even though a preference for a certain word-order over others can be observed (such as putting the subject after the finite verb in independent clauses unless it already precedes the verb[clarification needed]).

Phrase word orders and branching[edit]

The order of constituents in a phrase can vary as much as the order of constituents in a clause. Normally, the noun phrase and the adpositional phrase are investigated. Within the noun phrase, one investigates whether the following modifiers occur before and/or after the head noun.

- adjective (red house vs house red)

- determiner (this house vs house this)

- numeral (two houses vs houses two)

- possessor (my house vs house my)

- relative clause (the by me built house vs the house built by me)

Within the adpositional clause, one investigates whether the languages makes use of prepositions (in London), postpositions (London in), or both (normally with different adpositions at both sides) either separately (For whom? or Whom for?) or at the same time (from her away; Dutch example: met hem mee meaning together with him).

There are several common correlations between sentence-level word order and phrase-level constituent order. For example, SOV languages generally put modifiers before heads and use postpositions. VSO languages tend to place modifiers after their heads, and use prepositions. For SVO languages, either order is common.

For example, French (SVO) uses prepositions (dans la voiture, à gauche), and places adjectives after (une voiture spacieuse). However, a small class of adjectives generally go before their heads (une grande voiture). On the other hand, in English (also SVO) adjectives almost always go before nouns (a big car), and adverbs can go either way, but initially is more common (greatly improved). (English has a very small number of adjectives that go after the heads, such as extraordinaire, which kept its position when borrowed from French.) Russian places numerals after nouns to express approximation (шесть домов=six houses, домов шесть=circa six houses).

Pragmatic word order[edit]

Some languages do not have a fixed word order and often use a significant amount of morphological marking to disambiguate the roles of the arguments. However, the degree of marking alone does not indicate whether a language uses a fixed or free word order: some languages may use a fixed order even when they provide a high degree of marking, while others (such as some varieties of Datooga) may combine a free order with a lack of morphological distinction between arguments.

Typologically, there is a trend that high-animacy actors are more likely to be topical than low-animacy undergoers; this trend can come through even in languages with free word order, giving a statistical bias for SO order (or OS order in ergative systems; however, ergative systems do not always extend to the highest levels of animacy, sometimes giving way to an accusative system (see split ergativity)).[15]

Most languages with a high degree of morphological marking have rather flexible word orders, such as Polish, Hungarian, Portuguese, Latin, Albanian, and O’odham. In some languages, a general word order can be identified, but this is much harder in others.[16] When the word order is free, different choices of word order can be used to help identify the theme and the rheme.

Hungarian[edit]

Word order in Hungarian sentences is changed according to the speaker’s communicative intentions. Hungarian word order is not free in the sense that it must reflect the information structure of the sentence, distinguishing the emphatic part that carries new information (rheme) from the rest of the sentence that carries little or no new information (theme).

The position of focus in a Hungarian sentence is immediately before the verb, that is, nothing can separate the emphatic part of the sentence from the verb.

For «Kate ate a piece of cake«, the possibilities are:

- «Kati megevett egy szelet tortát.» (same word order as English) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«]

- «Egy szelet tortát Kati evett meg.» (emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«A piece of cake Kate ate.«] (One of the pieces of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Kati evett meg egy szelet tortát.» (also emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«] (Kate was the one eating one piece of cake.)

- «Kati egy szelet tortát evett meg.» (emphasis on object [cake]) [«Kate a piece of cake ate.»] (Kate ate a piece of cake – cf. not a piece of bread.)

- «Egy szelet tortát evett meg Kati.» (emphasis on number [a piece, i.e. only one piece]) [«A piece of cake ate Kate.»] (Only one piece of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Megevett egy szelet tortát Kati.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate a piece of cake Kate.»] (A piece of cake had been finished by Kate.)

- «Megevett Kati egy szelet tortát.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate Kate a piece of cake.«] (Kate finished with a piece of cake.)

The only freedom in Hungarian word order is that the order of parts outside the focus position and the verb may be freely changed without any change to the communicative focus of the sentence, as seen in sentences 2 and 3 as well as in sentences 6 and 7 above. These pairs of sentences have the same information structure, expressing the same communicative intention of the speaker, because the part immediately preceding the verb is left unchanged.

Note that the emphasis can be on the action (verb) itself, as seen in sentences 1, 6 and 7, or it can be on parts other than the action (verb), as seen in sentences 2, 3, 4 and 5. If the emphasis is not on the verb, and the verb has a co-verb (in the above example ‘meg’), then the co-verb is separated from the verb, and always follows the verb. Also note that the enclitic -t marks the direct object: ‘torta’ (cake) + ‘-t’ -> ‘tortát’.

Hindi-Urdu[edit]

Hindi-Urdu (Hindustani) is essentially a verb-final (SOV) language, with relatively free word order since in most cases postpositions mark quite explicitly the relationships of noun phrases with other constituents of the sentence.[17] Word order in Hindustani usually does not signal grammatical functions.[18] Constituents can be scrambled to express different information structural configurations, or for stylistic reasons. The first syntactic constituent in a sentence is usually the topic,[19][18] which may under certain conditions be marked by the particle «to» (तो / تو), similar in some respects to Japanese topic marker は (wa).[20][21][22][23] Some rules governing the position of words in a sentence are as follows:

- An adjective comes before the noun it modifies in its unmarked position. However, the possessive and reflexive pronominal adjectives can occur either to the left or to the right of the noun it describes.

- Negation must come either to the left or to the right of the verb it negates. For compound verbs or verbal construction using auxiliaries the negation can occur either to the left of the first verb, in-between the verbs or to the right of the second verb (the default position being to the left of the main verb when used with auxiliary and in-between the primary and the secondary verb when forming a compound verb).

- Adverbs usually precede the adjectives they qualify in their unmarked position, but when adverbs are constructed using the instrumental case postposition se (से /سے) (which qualifies verbs), their position in the sentence becomes free. However, since both the instrumental and the ablative case are marked by the same postposition «se» (से /سے), when both are present in a sentence then the quantity they modify cannot appear adjacent to each other[clarification needed].[24][18]

- «kyā » (क्या / کیا) «what» as the yes-no question marker occurs at the beginning or the end of a clause as its unmarked positions but it can be put anywhere in the sentence except the preverbal position, where instead it is interpreted as interrogative «what».

Some of all the possible word order permutations of the sentence «The girl received a gift from the boy on her birthday.» are shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

Portuguese[edit]

In Portuguese, clitic pronouns and commas allow many different orders:[citation needed]

- «Eu vou entregar a você amanhã.» [«I will deliver to you tomorrow.»] (same word order as English)

- «Entregarei a você amanhã.» [«{I} will deliver to you tomorrow.»]

- «Eu lhe entregarei amanhã.» [«I to you will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «Entregar-lhe-ei amanhã.» [«Deliver to you {I} will tomorrow.»] (mesoclisis)

- «A ti, eu entregarei amanhã.» [«To you I will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «A ti, entregarei amanhã.» [«To you deliver {I} will tomorrow.»]

- «Amanhã, entregar-te-ei» [«Tomorrow {I} will deliver to you»]

- «Poderia entregar, eu, a você amanhã?» [«Could deliver I to you tomorrow?]

Braces ({ }) are used above to indicate omitted subject pronouns, which may be implicit in Portuguese. Because of conjugation, the grammatical person is recovered.

Latin[edit]

In Latin, the endings of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns allow for extremely flexible order in most situations. Latin lacks articles.

The Subject, Verb, and Object can come in any order in a Latin sentence, although most often (especially in subordinate clauses) the verb comes last.[25] Pragmatic factors, such as topic and focus, play a large part in determining the order. Thus the following sentences each answer a different question:[26]

- «Romulus Romam condidit.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What did Romulus do?)

- «Hanc urbem condidit Romulus.» [«Romulus founded this city»] (Who founded this city?)

- «Condidit Romam Romulus.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What happened?)

Latin prose often follows the word order «Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Adverb, Verb»,[27] but this is more of a guideline than a rule. Adjectives in most cases go before the noun they modify,[28] but some categories, such as those that determine or specify (e.g. Via Appia «Appian Way»), usually follow the noun. In Classical Latin poetry, lyricists followed word order very loosely to achieve a desired scansion.

Albanian[edit]

Due to the presence of grammatical cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and in some cases or dialects vocative and locative) applied to nouns, pronouns and adjectives, the Albanian language permits a large number of positional combination of words. In spoken language a word order differing from the most common S-V-O helps the speaker putting emphasis on a word, thus changing partially the message delivered. Here is an example:

- «Marku më dha një dhuratë (mua).» [«Mark (me) gave a present to me.»] (neutral narrating sentence.)

- «Marku (mua) më dha një dhuratë.» [«Mark to me (me) gave a present.»] (emphasis on the indirect object, probably to compare the result of the verb on different persons.)

- «Marku një dhuratë më dha (mua).» [«Mark a present (me) gave to me»] (meaning that Mark gave her only a present, and not something else or more presents.)

- «Marku një dhuratë (mua) më dha.» [«Mark a present to me (me) gave»] (meaning that Mark gave a present only to her.)

- «Më dha Marku një dhuratë (mua).» [«Gave Mark to me a present.»] (neutral sentence, but puts less emphasis on the subject.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë Marku (mua).» [«Gave a present to me Mark.»] (probably is the cause of an event being introduced later.)

- «Më dha (mua) Marku një dhurate.» [«Gave to me Mark a present.»] (same as above.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë mua Marku» [«(Me) gave a present to me Mark.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that the receiver is her and not someone else.)

- «Një dhuratë më dha Marku (mua)» [«A present gave Mark to me.»] (meaning it was a present and not something else.)

- «Një dhuratë Marku më dha (mua)» [«A present Mark gave to me.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that she got the present and someone else got something different.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) më dha Marku.» [«A present to me gave Mark.»] (no particular emphasis, but can be used to list different actions from different subjects.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) Marku më dha.» [«A present to me Mark (me) gave»] (remembers that at least a present was given to her by Mark.)

- «Mua më dha Marku një dhuratë.» [«To me (me) gave Mark a present.» (is used when Mark gave something else to others.)

- «Mua një dhuratë më dha Marku.» [«To me a present (me) gave Mark.»] (emphasis on «to me» and the fact that it was a present, only one present or it was something different from usual.)

- «Mua Marku një dhuratë më dha» [«To me Mark a present (me) gave.»] (Mark gave her only one present.)

- «Mua Marku më dha një dhuratë» [«To me Mark (me) gave a present.»] (puts emphasis on Mark. Probably the others didn’t give her present, they gave something else or the present wasn’t expected at all.)

In these examples, «(mua)» can be omitted when not in first position, causing a perceivable change in emphasis; the latter being of different intensity. «Më» is always followed by the verb. Thus, a sentence consisting of a subject, a verb and two objects (a direct and an indirect one), can be

expressed in six different ways without «mua», and in twenty-four different ways with «mua», adding up to thirty possible combinations.

O’odham (Papago-Pima)[edit]

O’odham is a language that is spoken in southern Arizona and Northern Sonora, Mexico. It has free word order, with only the auxiliary bound to one spot. Here is an example, in literal translation:[14]

- «Wakial ‘o g wipsilo ha-cecposid.» [Cowboy is the calves them branding.] (The cowboy is branding the calves.)

- «Wipsilo ‘o ha-cecposid g wakial.» [Calves is them branding the cowboy.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wakial g wipsilo.» [Them Branding is the cowboy the calves.]

- «Wipsilo ‘o g wakial ha-cecposid.» [Calves is the cowboy them branding.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wipsilo g wakial.» [Them branding is the calves the cowboy.]

- «Wakial ‘o ha-cecposid g wipsilo.» [Cowboy is them branding the calves.]

These examples are all grammatically-valid variations on the sentence «The cowboy is branding the calves,» but some are rarely found in natural speech, as is discussed in Grammaticality.

Other issues with word order[edit]

Language change[edit]

Languages change over time. When language change involves a shift in a language’s syntax, this is called syntactic change. An example of this is found in Old English, which at one point had flexible word order, before losing it over the course of its evolution.[29] In Old English, both of the following sentences would be considered grammatically correct:

- «Martianus hæfde his sunu ær befæst.» [Martianus had his son earlier established.] (Martianus had earlier established his son.)

- «Se wolde gelytlian þone lyfigendan hælend.» [He would diminish the living saviour.]

This flexibility continues into early Middle English, where it seems to drop out of usage.[30] Shakespeare’s plays use OV word order frequently, as can be seen from this example:

- «It was our selfe thou didst abuse.»[31]

A modern speaker of English would possibly recognise this as a grammatically comprehensible sentence, but nonetheless archaic. There are some verbs, however, that are entirely acceptable in this format:

- «Are they good?»[32]

This is acceptable to a modern English speaker and is not considered archaic. This is due to the verb «to be», which acts as both auxiliary and main verb. Similarly, other auxiliary and modal verbs allow for VSO word order («Must he perish?»). Non-auxiliary and non-modal verbs require insertion of an auxiliary to conform to modern usage («Did he buy the book?»). Shakespeare’s usage of word order is not indicative of English at the time, which had dropped OV order at least a century before.[33]

This variation between archaic and modern can also be shown in the change between VSO to SVO in Coptic, the language of the Christian Church in Egypt.[34]

Dialectal variation[edit]

There are some languages where a certain word order is preferred by one or more dialects, while others use a different order. One such case is Andean Spanish, spoken in Peru. While Spanish is classified as an SVO language,[35] the variation of Spanish spoken in Peru has been influenced by contact with Quechua and Aymara, both SOV languages.[36] This has had the effect of introducing OV (object-verb) word order into the clauses of some L1 Spanish speakers (moreso than would usually be expected), with more L2 speakers using similar constructions.

Poetry[edit]

Poetry and stories can use different word orders to emphasize certain aspects of the sentence. In English, this is called anastrophe. Here is an example:

«Kate loves Mark.»

«Mark, Kate loves.»

Here SVO is changed to OSV to emphasize the object.

Translation[edit]

Differences in word order complicate translation and language education – in addition to changing the individual words, the order must also be changed. The area in Linguistics that is concerned with translation and education is language acquisition. The reordering of words can run into problems, however, when transcribing stories. Rhyme scheme can change, as well as the meaning behind the words. This can be especially problematic when translating poetry.

See also[edit]

- Antisymmetry

- Information flow

- Language change

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hammarström included families with no data in his count (58 out of 424 = 13,7%), but did not include them in the list. This explains why the percentages do not sum to 100% in this column.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Comrie, Bernard. (1981). Language universals and linguistic typology: syntax and morphology (2nd ed). University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ^ Sakel, Jeanette (2015). Study Skills for Linguistics. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 9781317530107.

- ^ Hengeveld, Kees (1992). Non-verbal predication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013713-5.

- ^ Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1993). «Das Nomen – eine universale Kategorie?» [The noun – a universal category?]. STUF — Language Typology and Universals (in German). 46 (1–4). doi:10.1524/stuf.1993.46.14.187. S2CID 192204875.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (November 2007). «Word Classes: Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00030.x. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2004), The Noun Phrase, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926964-5.

- ^ Greenberg, Joseph H. (1963). «Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements» (PDF). In Greenberg, Joseph H. (ed.). Universals of Human Language. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 73–113. doi:10.1515/9781503623217-005. ISBN 9781503623217. S2CID 2675113.

- ^ a b Dryer, Matthew S. (2013). «Order of Subject, Object and Verb». In Dryer, Matthew S.; Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ^ Tomlin, Russel S. (1986). Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-415-72357-4.

- ^ Kordić, Snježana (2006) [1st pub. 1997]. Serbo-Croatian. Languages of the World/Materials ; 148. Munich & Newcastle: Lincom Europa. pp. 45–46. ISBN 3-89586-161-8. OCLC 37959860. OL 2863538W. Contents. Summary. [Grammar book].

- ^ Dryer, M. S. (2005). «Order of Subject, Object, and Verb». In Haspelmath, M. (ed.). The World Atlas of Language Structures.

- ^ Hammarström, H. (2016). «Linguistic diversity and language evolution». Journal of Language Evolution. 1 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1093/jole/lzw002.

- ^ Dryer, Matthew S. (1992). «The Greenbergian word order correlations». Language. 68 (1): 81–138. doi:10.1353/lan.1992.0028. JSTOR 416370. S2CID 9693254. Project MUSE 452860.

- ^ a b Hale, Kenneth L. (1992). «Basic word order in two «free word order» languages». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 63. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.03hal. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (1981). Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (2nd edn). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Rude, Noel (1992). «Word order and topicality in Nez Perce». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 193. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.08rud. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 159–160. ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- ^ a b c Mohanan, Tara (1994). «Case OCP: A Constraint on Word Order in Hindi». In Butt, Miriam; King, Tracy Holloway; Ramchand, Gillian (eds.). Theoretical Perspectives on Word Order in South Asian Languages. Center for the Study of Language (CSLI). pp. 185–216. ISBN 978-1-881526-49-0.

- ^ Gambhir, Surendra Kumar (1984). The East Indian speech community in Guyana: a sociolinguistic study with special reference to koine formation (Thesis). OCLC 654720956.[page needed]

- ^ Kuno 1981[full citation needed]

- ^ Kidwai 2000[full citation needed]

- ^ Patil, Umesh; Kentner, Gerrit; Gollrad, Anja; Kügler, Frank; Fery, Caroline; Vasishth, Shravan (17 November 2008). «Focus, Word Order and Intonation in Hindi». Journal of South Asian Linguistics. 1.

- ^ Vasishth, Shravan (2004). «Discourse Context and Word Order Preferences in Hindi». The Yearbook of South Asian Languages and Linguistics (2004). pp. 113–128. doi:10.1515/9783110179897.113. ISBN 978-3-11-020776-7.

- ^ Spencer, Andrew (2005). «Case in Hindi». The Proceedings of the LFG ’05 Conference (PDF). pp. 429–446.

- ^ Scrivner, Olga (June 2015). A Probabilistic Approach in Historical Linguistics. Word Order Change in Infinitival Clauses: from Latin to Old French (Thesis). p. 32. hdl:2022/20230.

- ^ Spevak, Olga (2010). Constituent Order in Classical Latin Prose, p. 1, quoting Weil (1844).

- ^ Devine, Andrew M. & Laurence D. Stephens (2006), Latin Word Order, p. 79.

- ^ Walker, Arthur T. (1918). «Some Facts of Latin Word-Order». The Classical Journal. 13 (9): 644–657. JSTOR 3288352.

- ^ Taylor, Ann; Pintzuk, Susan (1 December 2011). «The interaction of syntactic change and information status effects in the change from OV to VO in English». Catalan Journal of Linguistics. 10: 71. doi:10.5565/rev/catjl.61.

- ^ Trips, Carola (2002). From OV to VO in Early Middle English. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. Vol. 60. doi:10.1075/la.60. ISBN 978-90-272-2781-2.

- ^ Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616, author. (4 February 2020). Henry V. ISBN 978-1-9821-0941-7. OCLC 1105937654. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1941). Much Ado about Nothing. Boston, USA: Ginn and Company. pp. 12, 16.

- ^ Crystal, David (2012). Think on my Words: Exploring Shakespeare’s Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-139-19699-4.

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (2000). «From VSO to SVO? Word Order and Rear Extraposition in Coptic». Stability, Variation and Change of Word-Order Patterns over Time. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 213. pp. 23–39. doi:10.1075/cilt.213.05lop. ISBN 978-90-272-3720-0.

- ^ «Spanish». The Romance Languages. 2003. pp. 91–142. doi:10.4324/9780203426531-7. ISBN 978-0-203-42653-1.

- ^ Klee, Carol A.; Tight, Daniel G.; Caravedo, Rocio (1 December 2011). «Variation and change in Peruvian Spanish word order: language contact and dialect contact in Lima». Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 30 (2): 5–32. Gale A348978474.

Further reading[edit]

- A collection of papers on word order by a leading scholar, some downloadable

- Basic word order in English clearly illustrated with examples.

- Bernard Comrie, Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (1981) – this is the authoritative introduction to word order and related subjects.

- Order of Subject, Object, and Verb (PDF). A basic overview of word order variations across languages.

- Haugan, Jens, Old Norse Word Order and Information Structure. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 2001. ISBN 82-471-5060-3

- Rijkhoff, Jan (2015). «Word Order». International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (PDF). pp. 644–656. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.53031-1. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- Song, Jae Jung (2012), Word Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87214-0 & ISBN 978-0-521-69312-7

Order of words in a sentence

An important feature of the English sentence is the strictly defined word order. Unlike the Russian language, English verbs do not have personal endings, and nouns, adjectives and pronouns do not have case endings, so the relationship between words is determined by the order of the words. If the word order is violated, the meaning of the sentence is violated.

Word order in a declarative sentence

The normal word order in a declarative sentence is subject + predicate (that is, the predicate is never in front of the subject). In case the verb has an object, it usually follows the verb: Subject + Predicated + Complement.

Example: I can see my friend. — I see my friend.

Circumstances are most often at the very beginning or at the very end of the sentence. Of course, in English there are other options, for example, the so-called reverse word order, but in this work I give only basic information that is necessary and minimally sufficient.

Word order in an interrogative sentence

There are four main types of interrogative sentences. We will consider two types: general and specific questions.

General question Is a question that can be answered «yes» or «no». Word order in a general question: auxiliary or modal verb or linking verb + subject + predicate. Example: Can you swim? — Can you swim?

Special question Is a question that starts with a question word. English question words: what — what, what; when — when; where — where; why — why; how — how; whose — whose; which — which; who — who; whom — whom. The word order in the special question is: question word + auxiliary or modal verb + subject + predicate.

As we can see, the word order in the special question is the same as the word order in the general question. The only difference is that the question word comes first. The subject question has its own characteristics. In the question to the subject, sentences in the place of the subject (i.e.

at the beginning of a sentence) there is an interrogative word; the order of the rest of the clause is the same as in the declarative clause. Example: Who can swim? — Who can swim? That is, it all comes down to substituting the question word who or what (who or what) in the place of the subject.

No further changes are made.

Word order in negative sentences

Subject + auxiliary or modal verb or linking verb + particle not + predicate.

Example: He does not read. — He doesn’t read.

← back contents forward →

Source: http://begin-english.ru/study/sentence/

Word order in an English sentence, part 1

Can interrogative word order be used in affirmative sentences? How to build a sentence if there is no subject in it? Read about these and other nuances in our article.

Affirmative sentences

In English, the basic word order can be described by the formula SVO: subject — verb — object (subject — predicate — object).

Mary reads many books. — Mary reads a lot of books.

A subject is a noun or pronoun that appears at the beginning of a sentence (who? — Mary).

The predicate is the verb that comes after the subject (what does it do? — reads).

An addendum is a noun or pronoun that comes after a verb (what? — books).

There are no cases in English, so it is necessary to strictly observe the basic order of words, since it is often the only thing that indicates a connection between words.

SubjectPausableCompletionTranslation

| my mom | loves | soap operas. | My mom loves soap operas. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Sally found her keys. |

| I | remember | you. | I remember you. |

The verb to be in affirmative sentences

As a rule, an English sentence is not complete without a verb predicate. Since it is possible to construct a sentence in Russian without a verb, we often forget about it in English. For example:

mary is a teacher. — Mary is a teacher. (Mary is teacher.)

I‘m scared. — I’m scared. (I AM I am scared.)

Life is unfair. — Life is not fair. (Life is unfair.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — My younger brother is ten years old. (To my little brother Yes ten years.)

His friends are from Spain. — His friends are from Spain. (His friends occur from Spain.)

The vase is on the table. — The vase is on the table. (Vase is/is on the table.)

To summarize, the verb to be translated into Russian can mean:

- to be / is / to be;

- be / stay (in some place or state);

- exist;

- originate (from some locality).