На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

одним словом, да

честно, да

In a word, yes they are worth it.

Could have died? in a word, yes.

In a word, yes, getting a tattoo is safe, but check out a prospective parlor’s protocol.

Одним словом, да, безопасно сделать татуировку, но проверьте возможный протокол салона.

In a word, yes, at least after you digest it.

Если кратко, то да, по крайней мере, он станет им после того, как вы его съедите.

Unfortunately, and in a word, yes.

In a word, yes, she’s very polarizing.

L.J. Dear L.J: In a word, yes.

Другие результаты

In a word, yes-at least for the next few years.

In a few words, yes, 2019 is clearly so much better in so many ways than 2018 and the last 7 years has been.

В нескольких словах, да, 2019 год явно намного лучше во многих отношениях, чем 2018 и последние 7 лет.

In a word: yes, this would be completely unprecedented and moreover implausible.

Одним словом: Да, это было бы совершенно невиданное и тем более неправдоподобным.

In a word-no. Okay, yes, but only in emergencies.

In a word, and unfortunately, yes.

Результатов: 730316. Точных совпадений: 14. Затраченное время: 388 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Yes is the opposite of no. We usually use yes to show that we agree with something, accept something or are willing to do something:

A:

Shall we stop for a coffee soon?

B:

Yes. That’s a good idea.

A:

Tim, can you work on the Rossiter Project with Will?

We can use yes as a response token to show that we are listening to someone and that we agree, or simply that we want them to continue talking. In informal speaking, we often use yeah instead of yes, especially to show that we are listening:

A:

I just added some garlic and chillies to the olive oil.

A:

Then I added just a little lemon juice.

A:

And some salt and pepper and that was it.

B:

Really. It sounds so easy. I must try it sometime.

We use yes to answer negative questions and negative question tags:

A:

Didn’t we visit Ellis Island when we went to New York?

A:

Haven’t you got two sisters?

Not: No, that’s right.

A:

That’s Stuart over there, isn’t it?

B:

Yes, it is. He’s got his brother with him too.

We cannot do without questions. We ask questions every day. We answer questions every day. Asking questions and getting answers to them, we become smarter. By asking questions we learn.

How to ask questions correctly? What are the types of questions in English?

Don’t worry if you don’t know yet. This is an easy and very interesting topic.

General questions (Yes/No Questions)

In some languages, we can only ask questions using interrogative intonation. In English, in order to form a question, we need additional tools:

- Auxiliary verbs.

- Special word order.

These tools depend on the type of questions we ask.

A general question (Yes/No Question) is one of the most popular and frequently used ways to get information.

A general question is a question that we can answer simply YES or NO.

We ask a general question when we don’t need more information. We ask a general question when it is enough for us to get YES or NO.

In English grammar, we call these questions: Yes / No questions or General Questions.

Look at the examples:

Question: Are you going to work today?

Answer: Yes, I am.Question: Do you want us to have dinner at a restaurant?

Answer: No, I don’t want to, thanks.

The word order inversion plays an important role in such questions.

It means that we put the auxiliary verb at the beginning. Not the subject. We put the subject after the auxiliary verb. Then we put the main verb. Then we can add the rest of the sentence.

Do you like your new job?

Does she know the secret?

We can also use modal verbs in general questions. In this case, we don’t need any auxiliary verbs. Because modal verb can play the auxiliary role for itself.

In such questions, we put the modal verb at the beginning of the sentence. After the modal verb, we put the subject. Then we put the main verb. Then we can add the rest of the sentence.

Could you do me a favor?

Can we help you this time?

Should I pretend to believe all that nonsense?

To form a general question with the verb to be, we also do not use auxiliary verbs. The verb to be, like modal verbs, forms questions on its own.

Is he saying something behind my back?

Are we really doing this again?

Look at the detailed explanation of what a general question consists of, this will help you better understand how we form them:

Do you know the answer?

Do (auxiliary) you (subject) know (predicate) the answer (object)? (question mark)

Can you help me?

Can (modal verb) you (subject) help (predicate) me (object)? (question mark)

Are you a writer?

Are (verb to be) you (subject) a writer (rest of the sentence) ? (question mark)

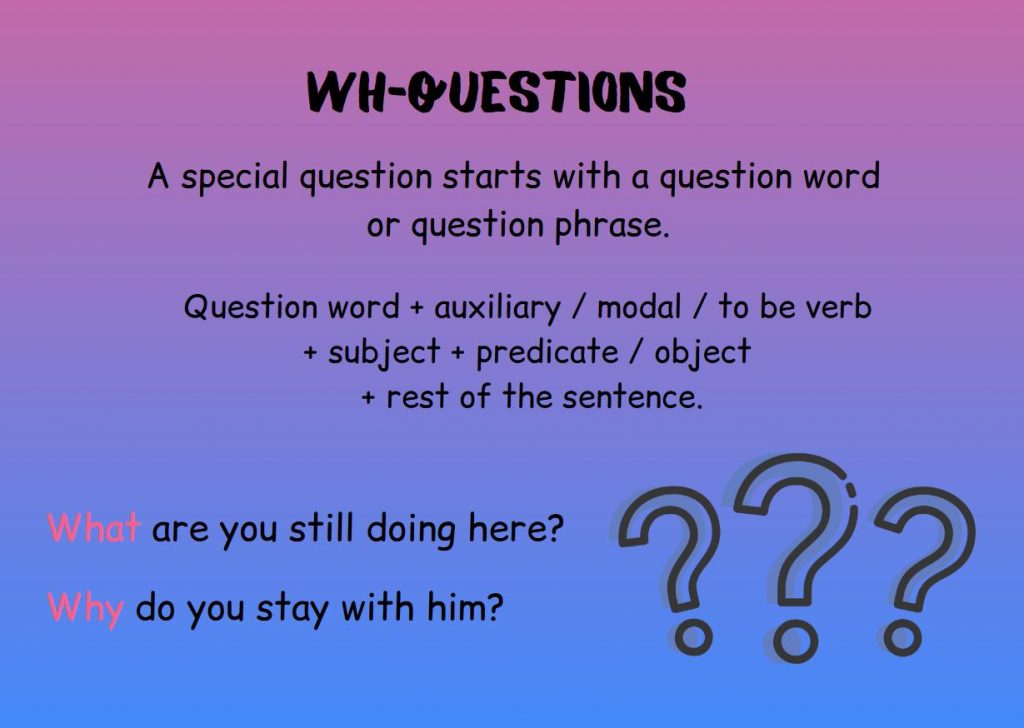

A special question differs from a general one in only one detail. A special question starts with a question word or question phrase.

We use a Special question to get additional information other than a YES / NO answer.

That is why a special question has a question word or phrase at the beginning.

Compare:

General yes / no question:

Will you go to work?

Special question with a question word:

When will you go to work?

We cannot simply answer yes/no to a Special question. Because a special question has an extra word or phrase at the beginning. This word or phrase influences the answer.

Question: Where were you yesterday?

Answer: I visited my friend Frank.

The word “where” in the question influenced the answer.

To ask a special question we usually use these question words:

- What?

- When?

- Where?

- Why?

- Which?

- Whose?

- Whom?

These question words begin with “Wh” so we often call special questions Wh-questions.

As you may have noticed, we use the same word order in Wh-questions as in General questions. We just simply add a question word (or question phrase) to the beginning of the question.

Question word + auxiliary / modal / to be verb + subject + predicate / object + rest of the sentence.

Take a look at examples:

When do you want me to leave?

Why do you stay with him?

What are you still doing here?

Why can’t you be with us tonight?

How long does he have to be in quarantine?

Questions to the subject in English

The next type of questions are Questions to the subject. We ask a question to the subject when we want to know WHO is performing the action.

Question: Who will go for a walk with you?

Answer: John.

Question: Who broke the cup?

Answer: Tom did it!Question: Who wants a slice of delicious pie?

Answer: I would not mind a piece of the pie …

The main feature of subject questions is that we don’t use any auxiliary verbs.

We just use the words Who or What instead of the subject.

If we ask a question to the subject in the Present Simple, then we add the ending -s to the main verb.

Question word + predicate + Secondary Parts of the Sentence

Who talks like that guy?

Who loves you?

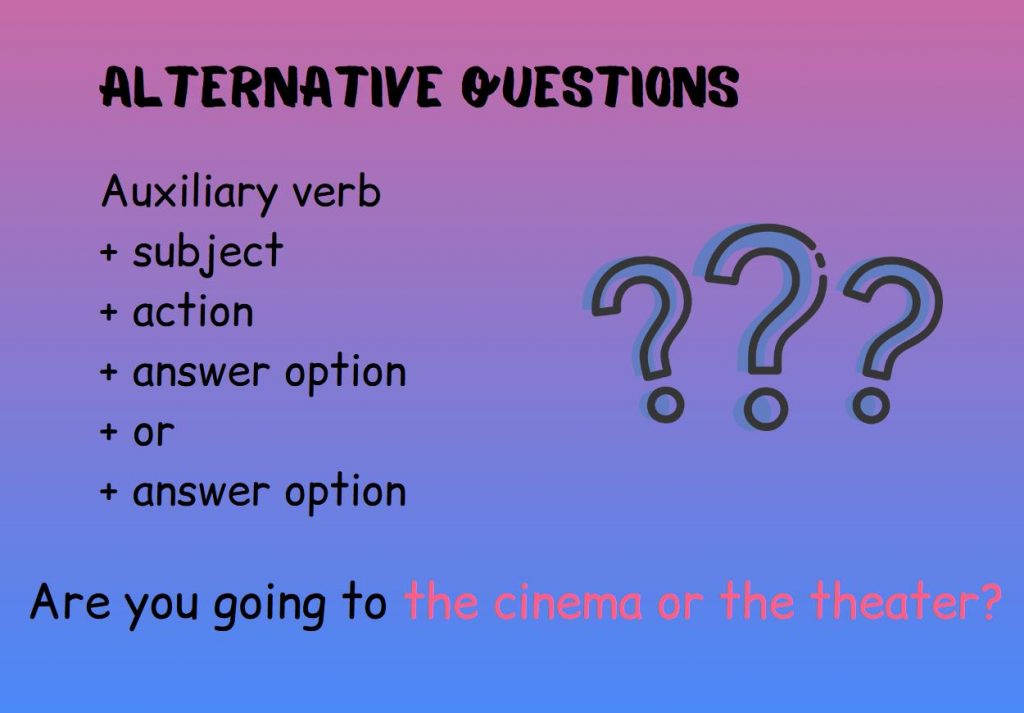

Alternative questions

Another type of question that you should understand is alternative questions.

Why do we call these questions alternative questions? Because when we ask an alternative question, we not only ask but also offer alternatives for the answer! Doesn’t that sound interesting? Take a look at examples:

Do you like it or not?

Would you like tea or coffee?

We can ask an alternative question to any Parts of the Sentence.

Note the conjunction or in these examples. The conjunction or is an important feature of alternative questions.

It is the or that separates the answer options.

We form alternative questions almost in the same way as general questions.

Auxiliary verb + subject + action + answer option + or + answer option

Will you work at the central bank or one of its branches?

Alternative questions always have the or part.

Are you going to the cinema or the theater?

Have you played football or basketball?

If we want to use several auxiliary verbs in an alternative question, then we put the first auxiliary verb before the subject, and we put the remaining auxiliary verbs immediately after the subject.

Has John been working in this department or the next one?

We can easily turn an alternative question into a Wh Alternate Question (Special Alternative Question). To do this, we put a question word, or phrase at the beginning of the question:

Who do you prefer to work with John or Tom?

When did you decide to buy a new car, today or yesterday?

Tag Questions

Tag Question is a very interesting type of question in English.

For example, we ask General Questions just to get an answer (Often this is a simple yes / no answer). Often, when we ask a general question we do not know what the answer is.

When we ask a tag question, we often expect to hear confirmation of some information that we already know. That is, when we ask a tag question, we often know or mean what the answer is!

You’re going to see your grandmother, aren’t you?

You probably noticed that such questions do not look exactly like questions? Indeed, tag questions are more like affirmative sentences.

We DO NOT use question word order in tag questions. We use direct word order.

The main feature of this type of question is in the ending. The end of a tag question is called the tag. This is why we call them Tag questions.

You like her, don’t you?

To form such a tag, we put an auxiliary verb and the subject at the end of the sentence.

Any tag question has two parts:

- Affirmative or negative sentence.

- Tag at the end.

In the first part, we put what we think is the answer.

In the second part, we use the tag for confirmation.

He doesn’t want to talk to me, does he?

Tag questions are very popular and convenient in the English language. We use them all the time. We often ask tag questions to start a conversation.

We also use tag questions as a way to express feelings or emotions:

- surprise

- irony

- distrust

- skepticism

- doubt

etc.

He can’t beat me, can he?

They will help you, won’t they?

Janice doesn’t want to go to school anymore, does she?

We won’t be able to win this game, can we?

You better give up, don’t you?

If we form a tag question using the verb to have, then the end of the question can have several types:

British English: You have a new bike, have you?

American English: They have a new home, don’t they?

If we form such a question with the pronoun I, then:

- In the affirmative question, the auxiliary verb remains in the am form.

- In the negative form, the auxiliary verb changes to aren’t I. Because it is inconvenient to say am not.

Correct: I am not the perfect Princess, am I?

Correct: I am the perfect Princess, aren’t I?

Incorrect: I am the perfect Princess, am not I?

A tag question can be negative even if there is no negative particle not in the first part. Take a look at this sentence:

You rarely go outside, do you?

Note that the tag contains the verb do without the negative particle not. The first part of the sentence also has no negation. Why do we use do you instead of don’t you? Because the first part of the question contains the negative word rarely.

RULE: If the first part of a tag question contains a word with a negative meaning, then the tag part must contain a verb in a positive form.

Examples of negative words we often use:

- scarcely

- hardly

- rarely

- barely

- little

Etc.

You barely know him, do you?

We rarely work, do we?

Negative questions

There is another popular question type in English. These are Negative questions.

We can divide negative questions into two types:

Type 1: contracted negative questions

Type 2: uncontracted negative questions

We use Contracted Questions to express:

- a polite request

- criticism

- dissatisfaction

- remark

- invitation

Why don’t you get some more champagne?

Wouldn’t you object at this point?

Why don’t you take him shopping?

Contracted negative questions begin with words such as:

- Won’t you …?

- Wouldn’t you …?

- Why don’t you …?

We use the following word order in contracted negative questions:

auxiliary verb + ending n’t + subject

Take a look at examples:

Won’t you guys go up with me, please?

Why don’t you keep your thoughts to yourself?

Wouldn’t you like to refresh yourself?

Won’t you please reconsider my request?

Such questions are considered less formal.

If you want to give a positive answer to this type of question, you should answer: YES. In case of a negative answer, you should answer: NO.

Haven’t you read what I wrote?

Yes.Haven’t you been dreaming about this?

No.Haven’t you people heard anything?

No.

Now let’s look at uncontracted negative questions. Such questions are more formal than contracted negative questions.

We form uncontracted negative questions using the following scheme:

Auxiliary verb + subject + not

See how it looks with examples:

Why do you not tell them I am here?

Do you not recognize your own best friend?

Why do you not want to help me?

Have you not figured that out?

Has he not been true to his vow?

Are they not a shame on their country?

Do you not dare to face me?

Have you not seen The Voice?

I live in Ukraine. Now, this website is the only source of money I have. If you would like to thank me for the articles I wrote, you can click Buy me a coffee. Thank you! ❤❤❤

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language.A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Contents

- 1 What is word and its example?

- 2 What is word and its types?

- 3 What is word linguistics?

- 4 What is the meaning of word?

- 5 What are words called?

- 6 What is word in language?

- 7 What is a word class in grammar?

- 8 Why do we define words?

- 9 Why do we say word?

- 10 What is morpheme and word?

- 11 What is word Slideshare?

- 12 Is word a noun or verb?

- 13 What are the parts of a word?

- 14 What is word Wikipedia?

- 15 What type of word is there?

- 16 What is word boundaries?

- 17 What is called sentence?

- 18 Is your name a word?

- 19 What are the 4 main word classes?

- 20 What is word class in syntax?

What is word and its example?

The definition of a word is a letter or group of letters that has meaning when spoken or written. An example of a word is dog.An example of words are the seventeen sets of letters that are written to form this sentence.

What is word and its types?

There are eight types of words that are often referred to as ‘word classes’ or ‘parts of speech’ and are commonly distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions.These are the different types of words in the English language.

What is word linguistics?

In linguistics, a word of a spoken language can be defined as the smallest sequence of phonemes that can be uttered in isolation with objective or practical meaning.In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a “word” may be learned as part of learning the writing system.

What is the meaning of word?

1 : a sound or combination of sounds that has meaning and is spoken by a human being. 2 : a written or printed letter or letters standing for a spoken word. 3 : a brief remark or conversation I’d like a word with you.

What are words called?

All words belong to categories called word classes (or parts of speech) according to the part they play in a sentence. The main word classes in English are listed below. Noun. Verb. Adjective.

What is word in language?

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sounds, or its representation in writing, that symbolizes and communicates a meaning and may consist of a single morpheme or a combination of morphemes. The branch of linguistics that studies word structures is called morphology.

A word class is a group of words that have the same basic behaviour, for example nouns, adjectives, or verbs.

Why do we define words?

The definition of definition is “a statement expressing the essential nature of something.” At least that’s one way Webster defines the word.Because definitions enable us to have a common understanding of a word or subject; they allow us to all be on the same page when discussing or reading about an issue.

Why do we say word?

‘Word’ in slang is a word one would use to indicate acknowledgement, approval, recognition or affirmation, of something somebody else just said.

What is morpheme and word?

Word vs Morpheme

A morpheme is usually considered as the smallest element of a word or else a grammar element, whereas a word is a complete meaningful element of language.

What is word Slideshare?

•“A word’ is a free morpheme or a combination of morphemes that together form a basic segment of speech” .

Is word a noun or verb?

word used as a noun:

A distinct unit of language (sounds in speech or written letters) with a particular meaning, composed of one or more morphemes, and also of one or more phonemes that determine its sound pattern. A distinct unit of language which is approved by some authority.

What are the parts of a word?

The parts of a word are called morphemes. These include suffixes, prefixes and root words. Take the word ‘microbiology,’ for example.

What is word Wikipedia?

A word is something spoken by the mouth, that can be pronounced. In alphabetic writing, it is a collection of letters used together to communicate a meaning. These can also usually be pronounced.Some words have different pronunciation, for example, ‘wind’ (the noun) and ‘wind’ (the verb) are pronounced differently.

What type of word is there?

The word “there” have multiple functions. In verbal and written English, the word can be used as an adverb, a pronoun, a noun, an interjection, or an adjective. This word is classified as an adverb if it is used to modify a verb in the sentence.

What is word boundaries?

A word boundary is a zero-width test between two characters. To pass the test, there must be a word character on one side, and a non-word character on the other side. It does not matter which side each character appears on, but there must be one of each.

What is called sentence?

A sentence is a set of words that are put together to mean something. A sentence is the basic unit of language which expresses a complete thought. It does this by following the grammatical basic rules of syntax.A complete sentence has at least a subject and a main verb to state (declare) a complete thought.

Is your name a word?

Yes, names are words. Specifically, they are proper nouns: they refer to specific people, places, or things. “John” is a proper noun; “ground” is a common noun. But both are words.

What are the 4 main word classes?

There are four major word classes: verb, noun, adjective, adverb.

What is word class in syntax?

In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution.It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).

Look up yes in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Look up no in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Yes and no, or word pairs with similar words, are expressions of the affirmative and the negative, respectively, in several languages, including English. Some languages make a distinction between answers to affirmative versus negative questions and may have three-form or four-form systems. English originally used a four-form system up to and including Early Middle English and Modern English has reduced to a two-form system consisting of ‘yes’ and ‘no’. It exists in many facets of communication, such as: eye blink communication, head movements, Morse Code, and sign language. Some languages, such as Latin, do not have yes-no word systems.

Answering yes/no question with single words meaning ‘yes’ or ‘no’ is by no means universal. Probably about half the world’s languages typically employ an echo response: repeating the verb in the question in an affirmative or a negative form. Some of these also have optional words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’, like Hungarian, Russian, and Portuguese. Others simply don’t have designated yes/no words, like Welsh, Irish, Latin, Thai, and Chinese.[1] Echo responses avoid the issue of what an unadorned yes means in response to a negative question. Yes and no can be used as a response to a variety of situations – but are better suited when asked simple questions. While a yes response to the question, «You don’t like strawberries?» is ambiguous in English, the Welsh response ydw (I am) has no ambiguity.

The words yes and no are not easily classified into any of the eight conventional parts of speech. Sometimes they are classified as interjections, although they do not qualify as such,[fact or opinion?] and they are not adverbs. They are sometimes classified as a part of speech in their own right, sentence words, or pro-sentences, although that category contains more than yes and no, and not all linguists include them in their lists of sentence words. Sentences consisting solely of one of these two words are classified as minor sentences.

Classification of English grammar[edit]

Although sometimes classified as interjections, these words do not express emotion or act as calls for attention; they are not adverbs because they do not qualify any verb, adjective, or adverb. They are sometimes classified as a part of speech in their own right: sentence words or word sentences.[2][3][4]

This is the position of Otto Jespersen, who states that «‘Yes’ and ‘No’ … are to all intents and purposes sentences just as much as the most delicately balanced sentences ever uttered by Demosthenes or penned by Samuel Johnson.»[5]

Georg von der Gabelentz, Henry Sweet, and Philipp Wegener have all written on the subject of sentence words. Both Sweet and Wegener include yes and no in this category, with Sweet treating them separately from both imperatives and interjections, although Gabelentz does not.[6]

Watts[7] classifies yes and no as grammatical particles, in particular response particles. He also notes their relationship to the interjections oh and ah, which is that the interjections can precede yes and no but not follow them. Oh as an interjection expresses surprise, but in the combined forms oh yes and oh no merely acts as an intensifier; but ah in the combined forms ah yes and ah no retains its stand-alone meaning, of focusing upon the previous speaker’s or writer’s last statement. The forms *yes oh, *yes ah, *no oh, and *no ah are grammatically ill-formed. Aijmer[8] similarly categorizes the yes and no as response signals or reaction signals.

Ameka classifies these two words in different ways according to the context. When used as back-channel items, he classifies them as interjections; but when they are used as the responses to a yes–no question, he classifies them as formulaic words. The distinction between an interjection and a formula is, in Ameka’s view, that the former does not have an addressee (although it may be directed at a person), whereas the latter does. The yes or no in response to the question is addressed at the interrogator, whereas yes or no used as a back-channel item is a feedback usage, an utterance that is said to oneself. However, Sorjonen criticizes this analysis as lacking empirical work on the other usages of these words, in addition to interjections and feedback uses.[9]

Bloomfield and Hockett classify the words, when used to answer yes-no questions, as special completive interjections. They classify sentences comprising solely one of these two words as minor sentences.[3]

Sweet classifies the words in several ways. They are sentence-modifying adverbs, adverbs that act as modifiers to an entire sentence. They are also sentence words, when standing alone. They may, as question responses, also be absolute forms that correspond to what would otherwise be the not in a negated echo response. For example, a «No.» in response to the question «Is he here?» is equivalent to the echo response «He is not here.» Sweet observes that there is no correspondence with a simple yes in the latter situation, although the sentence-word «Certainly.» provides an absolute form of an emphatic echo response «He is certainly here.» Many other adverbs can also be used as sentence words in this way.[10]

Unlike yes, no can also be an adverb of degree, applying to adjectives solely in the comparative (e.g., no greater, no sooner, but not no soon or no soonest), and an adjective when applied to nouns (e.g., «He is no fool.» and Dyer’s «No clouds, no vapours intervene.»).[10][11]

Grammarians of other languages have created further, similar, special classifications for these types of words. Tesnière classifies the French oui and non as phrasillons logiques (along with voici). Fonagy observes that such a classification may be partly justified for the former two, but suggests that pragmatic holophrases is more appropriate.[12]

The Early English four-form system[edit]

While Modern English has a two-form system of yes and no for affirmatives and negatives, earlier forms of English had a four-form system, comprising the words yea, nay, yes, and no. Yes contradicts a negatively formulated question, No affirms it; Yea affirms a positively formulated question, Nay contradicts it.

- Will they not go? — Yes, they will.

- Will they not go? — No, they will not.

- Will they go? — Yea, they will.

- Will they go? — Nay, they will not.

This is illustrated by the following passage from Much Ado about Nothing:[13]

Claudio: Can the world buie such a iewell? [buy such a jewel]

Benedick: Yea, and a case to put it into, but speake you this with a sad brow?

Benedick’s answer of yea is a correct application of the rule, but as observed by W. A. Wright «Shakespeare does not always observe this rule, and even in the earliest times the usage appears not to have been consistent.» Furness gives as an example the following, where Hermia’s answer should, in following the rule, have been yes:[13][14]

Demetrius: Do not you thinke, The Duke was heere, and bid vs follow him?

Hermia: Yea, and my Father.

This subtle grammatical feature of Early Modern English is recorded by Sir Thomas More in his critique of William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament into Early Modern English, which was then quoted as an authority by later scholars:[13]

I would not here note by the way that Tyndale here translateth no for nay, for it is but a trifle and mistaking of the Englishe worde : saving that ye shoulde see that he whych in two so plain Englishe wordes, and so common as in naye and no can not tell when he should take the one and when the tother, is not for translating into Englishe a man very mete. For the use of these two wordes in aunswering a question is this. No aunswereth the question framed by the affirmative. As for ensample if a manne should aske Tindall himselfe: ys an heretike meete to translate Holy Scripture into Englishe ? Lo to thys question if he will aunswere trew Englishe, he must aunswere nay and not no. But and if the question be asked hym thus lo: is not an heretike mete to translate Holy Scripture into Englishe ? To this question if he will aunswere trewe Englishe, he must aunswere no and not nay. And a lyke difference is there betwene these two adverbs ye and yes. For if the question bee framed unto Tindall by the affirmative in thys fashion. If an heretique falsely translate the New Testament into Englishe, to make his false heresyes seem the word of Godde, be his bokes worthy to be burned ? To this questyon asked in thys wyse, yf he will aunswere true Englishe, he must aunswere ye and not yes. But now if the question be asked him thus lo; by the negative. If an heretike falsely translate the Newe Testament into Englishe to make his false heresyee seme the word of God, be not hys bokes well worthy to be burned ? To thys question in thys fashion framed if he will aunswere trewe Englishe he may not aunswere ye but he must answere yes, and say yes marry be they, bothe the translation and the translatour, and al that wyll hold wyth them.

— Thomas More, The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, pp. 430[15][16]

In fact, More’s exemplification of the rule actually contradicts his statement of what the rule is. This went unnoticed by scholars such as Horne Tooke, Robert Gordon Latham, and Trench, and was first pointed out by George Perkins Marsh in his Century Dictionary, where he corrects More’s incorrect statement of the first rule, «No aunswereth the question framed by the affirmative.», to read nay. That even More got the rule wrong, even while himself dressing down Tyndale for getting it wrong, is seen by Furness as evidence that the four word system was «too subtle a distinction for practice».

Marsh found no evidence of a four-form system in Mœso-Gothic, although he reported finding «traces» in Old English. He observed that in the Anglo-Saxon Gospels,

- positively phrased questions are answered positively with gea (John 21:15,16, King James Version: «Jesus saith to Simon Peter, Simon, son of Jonas, lovest thou me more than these? He saith unto him, Yea, Lord; thou knowest that I love thee» etc.)

- and negatively with ne (Luke 12:51, KJ: «Suppose ye that I am come to give peace on earth? I tell you, Nay; but rather division»; 13:4,5, KJ: «Or those eighteen, upon whom the tower in Siloam fell, and slew them, think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt in Jerusalem? I tell you, Nay: but, except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.»), nese (John 21:5 «Then Jesus saith unto them, Children, have ye any meat? They answered him, No.»; Matthew 13:28,29, KJ: «The servants said unto him, Wilt thou then that we go and gather them up? But he said, Nay; lest while ye gather up the tares, ye root up also the wheat with them.»), and nic meaning «not I» (John 18:17, KJ: «Then saith the damsel that kept the door unto Peter, Art not thou also one of this man’s disciples? He saith, I am not.»);

- while negatively phrased questions are answered positively with gyse (Matthew 17:25, KJ: «they that received tribute money came to Peter, and said, Doth not your master pay tribute? He saith, Yes.»)

- and negatively for example with nâ, meaning «no one» (John 8:10,11, «he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee? She said, No man, Lord.»).[14]

Marsh calls this four-form system of Early Modern English a «needless subtlety». Tooke called it a «ridiculous distinction», with Marsh concluding that Tooke believed Thomas More to have simply made this rule up and observing that Tooke is not alone in his disbelief of More. Marsh, however, points out (having himself analyzed the works of John Wycliffe, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, John Skelton, and Robert of Gloucester, and Piers Plowman and Le Morte d’Arthur) that the distinction both existed and was generally and fairly uniformly observed in Early Modern English from the time of Chaucer to the time of Tyndale. But after the time of Tyndale, the four-form system was rapidly replaced by the modern two-form system.[14]

Three-form systems[edit]

Several languages have a three-form system, with two affirmative words and one negative. In a three-form system, the affirmative response to a positively phrased question is the unmarked affirmative, the affirmative response to a negatively phrased question is the marked affirmative, and the negative response to both forms of question is the (single) negative. For example, in Norwegian the affirmative answer to «Snakker du norsk?» («Do you speak Norwegian?») is «Ja», and the affirmative answer to «Snakker du ikke norsk?» («Do you not speak Norwegian?») is «Jo», while the negative answer to both questions is «Nei».[14][17][18][19][20]

Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Hungarian, German, Dutch, French and Malayalam all have three-form systems. Swedish and Danish have ja, jo, and nej. Norwegian has ja, jo/jau, and nei. Icelandic has já, jú, and nei. Faroese has ja, jú, and nei. Hungarian has igen, de, and nem. German has ja, doch, and nein. Dutch has ja, jawel, and nee. French has oui, si, and non. Malayalam has അതേ, ഉവ്വ് and ഇല്ല. Though, technically Malayalam is a multi-form system of Yes and No as can be seen from below, the former are the formal words for Yes and No.

Swedish, and to some extent Danish and Norwegian, also have additional forms javisst and jovisst, analogous to ja and jo, to indicate a strong affirmative response. Swedish (and Danish and Norwegian slang) also have the forms joho and nehej, which both indicate stronger response than jo or nej. Jo can also be used as an emphatic contradiction of a negative statement.[18][21] And Malayalam has the additional forms അതേല്ലോ, ഉവ്വല്ലോ and ഇല്ലല്ലോ which act like question words, question tags or to strengthen the affirmative or negative response, indicating stronger meaning than അതേ, ഉവ്വ് and ഇല്ല. The words അല്ലേ, ആണല്ലോ, അല്ലല്ലോ, വേണല്ലോ, വേണ്ടല്ലോ, ഉണ്ടല്ലോ and ഇല്ലേ work in the same ways. These words also sound more polite as they don’t sound like curt when saying «No!» or «Yes!». ഉണ്ട means «it is there» and the word behaves as an affirmative response like അതേ. The usage of ഏയ് to simply mean «No» or «No way!», is informal and may be casual or sarcastic, while അല്ല is the more formal way of saying «false», «incorrect» or that «it is not» and is a negative response for questions. The word അല്ലല്ല has a stronger meaning than അല്ല. ശരി is used to mean «OK» or «correct», with the opposite ശരിയല്ല meaning «not OK» or «not correct». It is used to answer affirmatively to questions to confirm any action by the asker, but to answer negatively one says വേണ്ടാ. വേണം and വേണ്ട both mean to «want» and to «not want».

Other languages with four-form systems[edit]

Like Early Modern English, the Romanian language has a four-form system. The affirmative and negative responses to positively phrased questions are da and nu, respectively. But in responses to negatively phrased questions they are prefixed with ba (i.e. ba da and ba nu). nu is also used as a negation adverb, infixed between subject and verb. Thus, for example, the affirmative response to the negatively phrased question «N-ai plătit?» («Didn’t you pay?») is «Ba da.» («Yes.»—i.e. «I did pay.»), and the negative response to a positively phrased question beginning «Se poate să …?» («Is it possible to …?») is «Nu, nu se poate.» («No, it is not possible.»—note the use of nu for both no and negation of the verb.)[22][23][24]

Related words in other languages and translation problems[edit]

Bloomfield and Hockett observe that not all languages have special completive interjections.

Finnish[edit]

Finnish does not generally answer yes-no questions with either adverbs or interjections but answers them with a repetition of the verb in the question,[25] negating it if the answer is the negative. (This is an echo response.) The answer to «Tuletteko kaupungista?» («Are you coming from town?») is the verb form itself, «Tulemme.» («We are coming.») However, in spoken Finnish, a simple «Yes» answer is somewhat more common, «Joo.»

Negative questions are answered similarly. Negative answers are just the negated verb form. The answer to «Tunnetteko herra Lehdon?» («Do you know Mr Lehto?») is «En tunne.» («I don’t know.») or simply «En.» («I don’t.»).[3][26][27][28] However, Finnish also has particle words for «yes»: «Kyllä» (formal) and «joo» (colloquial). A yes-no question can be answered «yes» with either «kyllä» or «joo«, which are not conjugated according to the person and plurality of the verb. «Ei«, however, is always conjugated and means «no».

Estonian[edit]

Estonian has a structure similar to Finnish, with both repetitions and interjections. Jah means «yes». Unlike Finnish, the negation particle is always ei, regardless of person and plurality. Ei ole («am/are/is not») can be replaced by pole (a contraction of the ancient expression ep ole, meaning the same).

The word küll, cognate to Finnish kyllä, can be used to reply positively to a negative question: «Kas sa ei räägi soome keelt?» «Räägin küll!» («You don’t speak Finnish?» «Yes, I do!») It can also be used to approve a positive statement: «Sa tulidki kaasa!» «Tulin küll.» («You (unexpectedly) came along!» «Yes I did.»)

Latvian[edit]

Up until the 16th century Latvian did not have a word for «yes» and the common way of responding affirmatively to a question was by repeating the question’s verb, just as in Finnish. The modern day jā was borrowed from Middle High German ja and first appeared in 16th-century religious texts, especially catechisms, in answers to questions about faith. At that time such works were usually translated from German by non-Latvians that had learned Latvian as a foreign language. By the 17th century, jā was being used by some Latvian speakers that lived near the cities, and more frequently when speaking to non-Latvians, but they would revert to agreeing by repeating the question verb when talking among themselves. By the 18th century the use of jā was still of low frequency, and in Northern Vidzeme the word was almost non-existent until the 18th and early 19th century. Only in the mid-19th century did jā really become usual everywhere.[29]

Welsh[edit]

It is often assumed that Welsh has no words at all for yes and no. It has ie and nage, and do and naddo. However, these are used only in specialized circumstances and are some of the many ways in Welsh of saying yes or no. Ie and nage are used to respond to sentences of simple identification, while do and naddo are used to respond to questions specifically in the past tense. As in Finnish, the main way to state yes or no, in answer to yes-no questions, is to echo the verb of the question. The answers to «Ydy Ffred yn dod?» («Is Ffred coming?») are either «Ydy» («He is (coming).») or «Nac ydy» («He is not (coming)»). In general, the negative answer is the positive answer combined with nag. For more information on yes and no answers to yes-no questions in Welsh, see Jones, listed in further reading.[28][30][31]

Goidelic languages[edit]

The Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx) do not have words for yes or no at all. Instead, an echo response of the main verb used to ask the question is used. Sometimes, one of the words meaning «to be» (Irish tá or is, see Irish syntax § The forms meaning «to be»; Scottish Gaelic tha or is see Scottish Gaelic grammar § verbs; Manx ta or is) is used. For example, the Irish question «An bhfuil sé ag teacht?» («Is he coming?») may be answered «Tá« («Is») or «Níl« («Is not»). More frequently, another verb will be used. For example, to respond to «Ar chuala sé?» («Did he hear?»), «Chuala» («Heard») or «Níor chuala» («Did not hear») are used. Irish people frequently give echo answers in English as well, e.g. «Did you hear?» Answer «I heard/I did».

Latin[edit]

Latin has no single words for yes and no. Their functions as word sentence responses to yes-no questions are taken up by sentence adverbs, single adverbs that are sentence modifiers and also used as word sentences. There are several such adverbs classed as truth-value adverbs—including certe, fortasse, nimirum, plane, vero, etiam, sane, videlicet, and minime (negative). They express the speaker’s/writer’s feelings about the truth value of a proposition. They, in conjunction with the negator non, are used as responses to yes-no questions.[3][32][33][34][35] For example:

«Quid enim diceres? Damnatum? Certe non.» («For what could you say? That I had been condemned? Assuredly not.»)

Latin also employs echo responses.[34][36]

Galician and Portuguese[edit]

These languages have words for yes and no, namely si and non in Galician and sim and não in Portuguese. However, answering a question with them is less idiomatic than answering with the verb in the proper conjugation.

Spanish[edit]

In Spanish, the words sí ‘yes’ and no ‘no’ are unambiguously classified as adverbs: serving as answers to questions and also modifying verbs. The affirmative sí can replace the verb after a negation (Yo no tengo coche, pero él sí = I don’t own a car, but he does) or intensify it (I don’t believe he owns a car. / He does own one! = No creo que él tenga coche. / ¡Sí lo tiene!). The word no is the standard adverb placed next to a verb to negate it (Yo no tengo coche = I don’t own a car). Double negation is normal and valid in Spanish, and it is interpreted as reinforcing the negation (No tengo ningún coche = I own no car).

Chinese[edit]

Speakers of Chinese use echo responses.[37] In all Sinitic/Chinese languages, yes-no questions are often posed in A-not-A form, and the replies to such questions are echo answers that echo either A or not A.[38][39] In Standard Mandarin Chinese, the closest equivalents to yes and no are to state «是» (shì; lit. ‘»is»‘) and «不是» (búshì; lit. ‘»not is»‘).[40][41] The phrase 不要 (búyào; ‘(I) do not want’) may also be used for the interjection «no», and 嗯 (ǹg) may be used for «yes». Similarly, in Cantonese, the preceding are 係 hai6 (lit: «is») and 唔係 (lit: «not is») m4 hai6, respectively. One can also answer 冇錯 mou5 co3 (lit. ‘»not wrong»‘) for the affirmative, although there is no corresponding negative to this.

Japanese[edit]

Japanese lacks words for yes and no. The words «はい» (hai) and «いいえ» (iie) are mistaken by English speakers for equivalents to yes and no, but they actually signify agreement or disagreement with the proposition put by the question: «That’s right.» or «That’s not right.»[37][42] For example: if asked, Are you not going? (行かないのですか?, ikanai no desu ka?), answering with the affirmative «はい» would mean «Right, I am not going»; whereas in English, answering «yes» would be to contradict the negative question. Echo responses are not uncommon in Japanese.

Complications[edit]

These differences between languages make translation difficult. No two languages are isomorphic at the most elementary level of words for yes and no. Translation from two-form to three-form systems are equivalent to what English-speaking school children learning French or German encounter. The mapping becomes complex when converting two-form to three-form systems. There are many idioms, such as reduplication (in French, German, and Italian) of affirmatives for emphasis (the German ja ja ja).

The mappings are one-to-many in both directions. The German ja has no fewer than 13 English equivalents that vary according to context and usage (yes, yeah, and no when used as an answer; well, all right, so, and now, when used for segmentation; oh, ah, uh, and eh when used an interjection; and do you, will you, and their various inflections when used as a marker for tag questions) for example. Moreover, both ja and doch are frequently used as additional particles for conveying nuanced meaning where, in English, no such particle exists. Straightforward, non-idiomatic, translations from German to English and then back to German can often result in the loss of all of the modal particles such as ja and doch from a text.[43][44][45][46]

Translation from languages that have word systems to those that do not, such as Latin, is similarly problematic. As Calvert says, «Saying yes or no takes a little thought in Latin».[35]

Colloquial forms[edit]

Non-verbal[edit]

Linguist James R. Hurford notes that in many English dialects «there are colloquial equivalents of Yes and No made with nasal sounds interrupted by a voiceless, breathy h-like interval (for Yes) or by a glottal stop (for No)» and that these interjections are transcribed into writing as uh-huh or mm-hmm.[47] These forms are particularly useful for speakers who are at a given time unable to articulate the actual words yes and no.[47] The use of short vocalizations like uh-huh, mm-hmm, and yeah are examples of non-verbal communication, and in particular the practice of backchanneling.[48][49]

Art historian Robert Farris Thompson has posited that mm-hmm may be a loanword from a West African language that entered the English vernacular from the speech of enslaved Africans; linguist Lev Michael, however, says that this proposed origin is implausible, and linguist Roslyn Burns states that the origin of the term is difficult to confirm.[50]

Aye and variants[edit]

The word aye () as a synonym for yes in response to a question dates to the 1570s. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, it is of unknown origin. It may derive from the word I (in the context of «I assent»); as an alteration of the Middle English yai («yes»); or the adverb aye (meaning always «always, ever»), which comes from the Old Norse ei.[51] Using aye to mean yes is archaic, having disappeared from most of the English-speaking world, but is notably still used by people from Scotland, Ulster, and the north of England.[52]

In December 1993, a witness in a Scottish court who had answered «aye» to confirm he was the person summoned was told by a sheriff judge that he must answer either yes or no. When his name was read again and he was asked to confirm it, he answered «aye» again, and was imprisoned for 90 minutes for contempt of court. On his release he said, «I genuinely thought I was answering him.»[53]

Aye is also a common word in parliamentary procedure, where the phrase the ayes have it means that a motion has passed.[54] In the House of Commons of the British Parliament, MPs vote orally by saying «aye» or «no» to indicate they approve or disapprove of the measure or piece of legislation. (In the House of Lords, by contrast, members say «content» or «not content» when voting).[55]

The term has also historically been used in nautical usage, often phrased as «aye, aye, sir» duplicating the word «aye».[56] Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926) explained that the nautical phrase was at that time usually written ay, ay, sir.[54]

The informal, affirmative phrase why-aye (also rendered whey-aye or way-eye) is used in the dialect of northeast England,[57][58] most notably by Geordies.[58]

Other[edit]

Other variants of «yes» include acha in informal Indian English and historically righto or righty-ho in upper-class British English, although these fell out of use during the early 20th century.[52]

See also[edit]

- Affirmation and negation

- Thumb signal

- Translation

- Untranslatability

References[edit]

- ^ Holmberg, Anders (2016). The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–72. ISBN 9780198701859.

- ^ E. A. Sonnenschein (2008). «Sentence words». A New English Grammar Based on the Recommendations of the Joint Committee on Grammatical Terminology. READ BOOKS. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4086-8929-5.

- ^ a b c d Leonard Bloomfield & Charles F. Hockett (1984). Language. University of Chicago Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-226-06067-5.

- ^ Alfred S. West (February 2008). «Yes and No. What are we to call the words Yes and No?». The Elements Of English Grammar. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4086-8050-6.

- ^ Xabier Arrazola; Kepa Korta & Francis Jeffry (1995). Discourse, Interaction, and Communication. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7923-4952-5.

- ^ Giorgio Graffi (2001). 200 Years of Syntax. John Benjamins B.V. p. 121. ISBN 1-58811-052-4.

- ^ Richard J. Watts (1986). «Generated or degenerate?». In Dieter Kastovsky; A. J. Szwedek; Barbara Płoczińska; Jacek Fisiak (eds.). Linguistics Across Historical and Geographical Boundaries. Walter de Gruyter. p. 166. ISBN 978-3-11-010426-4.

- ^ Karin Aijmer (2002). «Interjections in a Contrastive Perspective». In Edda Weigand (ed.). Emotion in Dialogic Interaction. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-58811-497-6.

- ^ Marja-Leena Sorjonen (2001). Responding in Conversation. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-272-5085-8.

- ^ a b Henry Sweet (1900). «Adverbs». A New English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 1-4021-5375-9.

- ^ Henry Kiddle & Goold Brown (1867). The First Lines of English Grammar. New York: William Wood and Co. p. 102.

- ^ Ivan Fonagy (2001). Languages Within Language. John Benjamins B.V. p. 66. ISBN 0-927232-82-0.

- ^ a b c d William Shakespeare (1900). Horace Howard Furness (ed.). Much Ado about Nothing. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co. p. 25. (editorial footnotes)

- ^ a b c d George Perkins Marsh (1867). «Affirmative and Negative Particles». Lectures on the English Language. New York: Charles Scribner & Co. pp. 578–583.

- ^ Robert Gordon Latham (1850). The English language. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 497.

- ^ William Tyndale (1850). Henry Walter (ed.). An Answer to Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue. Cambridge: The University Press.

- ^ Åse-Berit Strandskogen & Rolf Strandskogen (1986). Norwegian. Oris Forlag. p. 146. ISBN 0-415-10979-5.

- ^ a b Philip Holmes & Ian Hinchliffe (1997). «Interjections». Swedish. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-16160-2.

- ^ Nigel Armstrong (2005). Translation, Linguistics, Culture. Multilingual Matters. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-85359-805-0.

- ^ Greg Nees (2000). Germany. Intercultural Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-877864-75-9.

- ^ Philip Holmes & Ian Hinchliffe (2003). «Ja, nej, jo, etc.». Swedish. Routledge. pp. 428–429. ISBN 978-0-415-27883-6.

- ^ Ramona Gönczöl-Davies (2007). Romanian. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-415-33825-7.

- ^ Graham Mallinson (1986). «answers to yes-no questions». Rumanian. Croom Helm Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 0-7099-3537-4.

- ^ Birgit Gerlach (2002). «The status of Romance clitics between words and affixes». Clitics Between Syntax and Lexicon. John Benjamins BV. p. 60. ISBN 90-272-2772-1.

- ^ «Yes/No systems». Aveneca. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Carl Philipp Reiff (1862). «The Adverb and the Gerund». English-Russian Grammar. Paris: Maisonneuve and Co. p. 134.

- ^ Wendy G. Lehnert & Brian K. Stucky (1988). «Understanding answers to questions». In Michel Meyer (ed.). Questions and Questioning. New York: de Gruyter. pp. 224, 232. ISBN 3-11-010680-9.

- ^ a b Cliff Goddard (2003). «Yes or no? The complex semantics of a simple question» (PDF). In Peter Collins; Mengistu Amberber (eds.). Proceedings of the 2002 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society. p. 7.

- ^ Karulis, Konstantīns (1992). Latviešu Etimoloģijas Vārdnīca [The Etymological dictionary of Latvian] (in Latvian). Rīga: Avots. ISBN 9984-700-12-7.

- ^ Gareth King (1996). «Yes/no answers». Basic Welsh. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-415-12096-8.

- ^ Mark H Nodine (2003-06-14). «How to say «Yes» and «No»«. A Welsh Course. Cardiff School of Computer Science, Cardiff University.

- ^ Dirk G. J. Panhuis (2006). Latin Grammar. University of Michigan Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-472-11542-6.

- ^ a b Harm Pinkster (2004). «Attitudinal and illocutionary satellites in Latin» (PDF). In Aertsen; Henk-Hannay; Mike-Lyall; Rod (eds.). Words in their places. A Festschrift for J. Lachlan MackenzieIII. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. pp. 191–195.

- ^ a b George J. Adler (1858). A Practical Grammar of the Latin Language; with Perpetual Exercises in Speaking and Writing. Boston: Sanborn, Carter, Bazin, & Co. p. 8.

- ^ a b J. B. Calvert (1999-06-24). «Comparison of adjectives and adverbs, and saying yes or no». Latin For Mountain Men. Elizabeth R. Tuttle.

- ^ Walter B. Gunnison (2008). Latin for the First Year. READ BOOKS. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4437-1459-4.

- ^ a b Rika Yoshii; Alfred Bork; Alastair Milne; Fusa Katada; Felicia Zhang (2004). «Reaching Students of Many Languages and Cultures». In Sanjaya Mishra (ed.). Interactive Multimedia in Education and Training. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 85. ISBN 978-1-59140-394-4.

- ^ Stephen Matthews & Virginia Yip (1994). Cantonese. Routledge. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-415-08945-6.

- ^ Timothy Shopen (1987). «Dialectal variations». Languages and Their Status. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1249-5.

- ^ Mandarin Chinese. Rough Guides. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85828-607-5.

- ^ Bingzheng Tong; Ping-cheng T’ung & David E. Pollard (1982). Colloquial Chinese. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 0-415-01860-9.

- ^ John Hinds (1988). «Words for ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘maybe’«. Japanese. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-415-01033-7.

- ^ Robert Jeffcoate (1992). Starting English Teaching. Routledge. p. 213. ISBN 0-415-05356-0.

- ^ Carol Erting; Robert C. Johnson & Dorothy L. Smith (1989). The Deaf Way. Gallaudet University Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-1-56368-026-7.

- ^ Kerstin Fischer (2000). From Cognitive Semantics to Lexical Pragmatics. Berlin: Walter de Gryuter. pp. 206–207. ISBN 3-11-016876-6.

- ^ Sándor G. J. Hervey; Ian Higgins & Michael Loughridge (1995). «The Function of Modal Particles». Thinking German Translation. Routledge. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-415-11638-1.

- ^ a b James R. Hurford (1994). «Interjections». Grammar: A Student’s Guide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-521-45627-2.

- ^ «Back-channel».

- ^ Arnold, Kyle (2012). «Humming Along». Contemporary Psychoanalysis. 48: 100–117. doi:10.1080/00107530.2012.10746491. S2CID 147330927.

- ^ Kumari Devarajan (August 17, 2018). «Ready For A Linguistic Controversy? Say ‘Mhmm’«. NPR.

- ^ aye (interj.), Online Etymology Dictionary (accessed January 30, 2019).

- ^ a b «Yes (adverb)» in Oxford Thesaurus of English (3d ed.: Oxford University Press, 2009 (ed. Maurice Waite), p. 986.

- ^ «Sheriff judges aye-aye a contemptible no-no». Herald Scotland. 11 December 1993. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b Fowler, H. W. (2010) [1926]. A Dictionary of Modern English Usage: The Classic First Edition. Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 9780199585892.

- ^ «Rules and traditions of Parliament». Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. «Aye Aye». Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ Perspectives on Northern Englishes (eds. Sylvie Hancil & Joan C. Beal: Walter de Gruyter: 2017), table 4.2: «North-east features represented in the LL Corpus.»

- ^ a b Emilia Di Martino, Celebrity Accents and Public Identity Construction: Analyzing Geordie Stylizations (Routledge, 2019).

Further reading[edit]

- Bob Morris Jones (1999). The Welsh Answering System. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-016450-3.—Jones’ analysis of how to answer questions with «yes» or «no» in the Welsh language, broken down into a typology of echo and non-echo responsives, polarity and truth-value responses, and numbers of forms

- George L. Huttar (1994). «Words for ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘maybe’«. Ndyuka: A Descriptive Grammar. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-415-05992-3.

- Holmberg, Anders (2016). The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198701859.

- Kulick, Don (April 2003). «No». Language & Communication. Elsevier. 23 (2): 139–151. doi:10.1016/S0271-5309(02)00043-5. Pdf. Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

An interrogative query that seeks a positive or negative answer

Updated on August 05, 2021

Also known as a polar interrogative, a polar question, and a bipolar question, a yes-no question is an interrogative construction (such as, «Are you ready?») that expects an answer of either «yes» or «no.» Wh- questions, on the other hand, can have a number of answers, and potentially more than one correct answer. In yes-no questions, an auxiliary verb typically appears in front of the subject—a formation called subject-auxiliary inversion (SAI).

Three Varieties of Yes-No Questions

There are three types of yes-no questions: the inverted question, the inversion with an alternative (which may require more than a simple yes or no answer), and the tag question.

- Are you going? (inversion)

- Are you staying or going? (inversion with an alternative)

- You’re going, aren’t you? (tag)

In an inverted question, the subject and the first verb of the verb phrase are inverted when that verb is either a modal or an auxiliary verb or with the verb be and sometimes have.

- She is leaving on Wednesday. (statement)

- Is she leaving on Wednesday? (question)

The question itself may be positive or negative. A positive question appears to be neutral with regard to the expected response—yes or no. A negative question seems to hold out the distinct possibility of a negative response, however, inflection is also a factor that can influence a yes/no response.

- Are you going? (Yes/No)

- Aren’t you going? (No)

The Use of Yes-No Questions in Polls and Surveys

Yes-no question are often used in surveys to gauge people’s attitudes with regard to specific ideas or beliefs. When enough data is gathered, those conducting the survey will have a measure based on a percentage of the population of how acceptable or unacceptable a proposition is. Here are some typical examples of survey questions:

- Are you in favor of increasing library funding? ___ Yes ___ No

- Do you support re-electing this candidate? ___ Yes ___ No

- Should people be required to spay/neuter their pets? ___ Yes ___ No

- Should the city approve this park plan?___ Yes ___ No

- Do you plan to vote in the next election?___ Yes ___ No

Another way to pose yes-no survey questions is in the form of a statement.

- Guests are always welcome here. ___ Yes ___ No

- My mom is the best cook in the world. ___ Yes ___ No

- I’ve read at least 50 books from the library. ___ Yes ___ No

- I will never eat pizza with pineapple on it. ___ Yes ___ No

«Typically, pollsters ask questions that will elicit yes or no answers. Is it necessary to point out that such answers do not give a robust meaning to the phrase ‘public opinion’? Were you, for example, to answer ‘No’ to the question ‘Do you think the drug problem can be reduced by government programs?’ one would hardly know much of interest or value about your opinion. But allowing you to speak or write at length on the matter would, of course, rule out using statistics.»—From «Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology» by Neil Postman

Examples of Yes-No Questions

Homer: «Are you an angel?»

Moe: «Yes, Homer. All us angels wear Farrah slacks.»

—»The Simpsons»

«Directing a movie is a very overrated job, we all know it. You just have to say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ What else do you do? Nothing. ‘Maestro, should this be red?’ Yes. ‘Green?’ No. ‘More extras?’ Yes. ‘More lipstick?’ No. Yes. No. Yes. No. That’s directing.»—Judi Dench as Liliane La Fleur in «Nine»

Principal McGee: «Are you just going to stand there all day?»

Sonny: «No ma’am. I mean, yes ma’am. I mean, no ma’am.»

Principal McGee: «Well, which is it?»

Sonny: «Um, no ma’am.»

—Eve Arden and Michael Tucci in «Grease»

Sources

- Wardhaugh, Ronald.»Understanding English Grammar: A Linguistic Approach.» Wiley-Blackwell, 2003

- Evans, Annabel Ness; Rooney, Bryan J. «Methods in Psychological Research,» Second Edition. Sage, 2011

- Postman, Neil. «Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology.» Alfred A. Knopf, 1992