It isn’t uncommon for Chuuya to invite Akutagawa out to drink. However, it

is

rare for him to accept. He usually won’t for obvious reasons (he doesn’t enjoy it) and not so obvious ones (bars make him uncomfortable). But this time when Chuuya sent the request his way, he thought that he might entertain his superior because he knew he would want to know how the joint mission with the ADA went, considering he wasn’t there under orders and therefore wouldn’t be giving a report.

Akutagawa swallows and sighs as he steps past the entrance. Almost immediately, Chuuya’s head pops out from one of the booths, and he gives him a wave. He stiffens before walking over and seating himself on the opposite bench.

Chuuya is grinning by the time he situates himself. “So you decided to join me tonight? That’s unusual.”

Akutagawa shrugs and reaches for the glass of water already on his side of the table. Chuuya, of course, already has a glass of red wine with him, and he’s thankful he doesn’t push him to join him in his consumption of alcohol. “I thought I would because I knew you’d want to hear about the mission.”

Chuuya rolls his eyes. “Well, yeah, I guess. But I also want to talk over a glass of wine.”

Akutagawa blinks and stays silent, not mentioning that he didn’t join the mafia to socialize. “Do you want to hear my report?”

Chuuya gives a flippant wave of his hand. “Yeah, go ahead.”

Akutagawa begins to speak, giving a concise and general report like he always does. Contrary to others in the mafia, he finds giving and writing reports for missions one of the more relaxing and pleasing parts of his job.

“That concludes my report,” he says after finishing his summary.

Chuuya hums, letting him know he’s listening. “Good work. I’d have never thought you’d be able to use your ability like that.”

Akutagawa raises a hand to his face and looks away. “Thank you.” And even though the compliment isn’t from the man he really wants, the praise is still… nice.

“When’d you get the idea to give Rashoumon to the kid?” Chuuya asks, genuinely curious.

Akutagawa pauses and thinks back to the fight on the boat. The final blow when he wrapped his ability around the weretiger’s curled first to help him defeat the enemy. That was when he knew Rashoumon could be used and manipulated with the weretiger’s claws. He remembers precisely what it felt like. Like he was on the verge of slipping his fingers into a glove. Fitting perfectly. “On Moby Dick with the fight with Fitzgerald.”

Chuuya hums and takes a sip of his wine. “How’s it working with the kid? I’ve never met him, so I don’t know what he’s like. Must be pretty strong if he can give you a run for your money.”

Akutagawa scowls. “Infuriating.”

Chuuya snorts. “You can say that again,” he says and takes a long sip of his wine in a way that tells Akutagawa he’s thinking of Dazai. “Anything interesting happen?”

Akutagawa swallows down some water and looks off to the side. The entire fight underground could be called “interesting”. He could recite his battle, which he knew Chuuya would like to hear, but he doesn’t really want to retell the entire thing again as an adventure story. One thought does come to mind though, something unusual that he’s never done before. “I rode the jinko at one point before our main fight with Goncharov.”

For some reason, that makes Chuuya spit out his wine. Akutagawa thinks it’s odd for his superior to waste wine he clearly loves so much, but he does suppose it’s a surprising thing to say.

Chuuya coughs and wheezes, eying Akutagawa. He clears his throat. “Uh, did I hear you right?”

Akutagawa pauses, curious at the reaction. “Yes.”

Chuuya’s face lights up because of something else other than wine. He coughs again, and his gaze doesn’t reach Akutagawa’s eyes.

Akutagawa frowns, annoyed. “What is it?”

“Nothing, nothing. It’s just… strange for you to say something like that. I’d have never guessed.”

Akutagawa pauses and thinks. He supposes it is odd for him to talk so explicitly about missions. Riding the jinko was odd, but the only reason it was done was for the mission. As… unorthodox as it was, it truly was the best decision in the moment. One he would have never thought of nor suggested.

Chuuya, however, still looks massively uncomfortable. He toys with his wine glass and struggles to figure out how to respond. How does he respond to something like that? His subordinate just straight faced admitted to losing his virginity to the weretiger on a mission. (Though he wasn’t going to say anything about the “on the mission” part because he knows how hypocritical that would sound coming out of his mouth.)

“Well, um, how was it?”

Akutagawa doesn’t say anything for a minute. Having his knees bent in such a way with his feet on Atsushi’s back truly wasn’t the most pleasant experience. He could easily go his entire life without experiencing that again. “Uncomfortable.”

But if he was being honest, having the weretiger easily go at that speed even with him on his back was… attractive. Feeling his spine and muscles twist and flex like they were his own was exhilarating. Tugging on his ear to direct him unnecessarily was (for lack of a better word) fun. “…But it wasn’t a totally terrible experience.”

Akutagawa looks back at Chuuya, but it seems every word he says is only making him more and more uneasy. “Chuuya-san?”

Chuuya shakes his head and clears his throat, pushing away his wine because he feels like he must be plastered to be hearing what he’s hearing. Having Akutagawa recall this event like it was nothing more than passing thought has his stomach turning. Should he not be a little embarrassed? Blushing maybe? The man dresses like a nun. He thought he would be the type of person to stab anyone who would even suggest anything sexual to him.

“So, let me get this straight, you decided to… ride the jinko in the middle of a mission?”

Akutagawa nods and takes a sip of his water, blissfully unaware of his superior’s inner turmoil.

“Why though? How could that have possibly come up?”

“To get closer to the enemy.”

Chuuya feels like he’s going insane. “How on earth would that have gotten you

closer

?” For a split second, he panics over the dreadful possibility that Akutagawa got himself involved in some kind of voyeurism.

Akutagawa knits his eyebrows. Chuuya seems nearly frantic, and he wonders why. “Chuuya-san, you shouldn’t worry. There is no possibility of me deviating from the Port Mafia.”

“I should hope not!” Because if the weretiger’s dick is so great it makes

Akutagawa

defect, then that’s something he’s never going to be able to comprehend. “I’m sorry, I’m just… having a hard time wrapping my mind around this.”

“It was the jinko’s idea,” Akutagawa offers, like that would calm his nerves.

“I’m fucking sure,” Chuuya snaps and swallows. He presses his fingers to his forehead. God, he’s never going to be able to get the image of Akutagawa in a compromising position out of his mind for a long time. Maybe he’ll drink himself stupid to hopefully forget this conversation.

“I apologize, Chuuya-san. I did not realize this knowledge would… distress you like this.”

Chuuya hums noncommittally and downs the rest of his wine. “I mean, like what the fuck was the kid

thinking

? Was he not? Boss and the ADA’s director were both dying, and

that’s

what he thought was the most important thing to do?”

Akutagawa feels the sudden need to defend Atsushi because it

feels

like he’s slandering his name. (Not that he cares about Atsushi’s reputation, he just wants to be the one to ruin it.) “Although it did not get us to where we needed to be, it was the best decision at the moment. However, being perched on his back was highly precarious.”

Chuuya suddenly freezes where he’s pouring more wine into his glass. He slowly looks up. “His back?” He sets the bottle down with a loud thump. “What do you mean his back?”

“Obviously, I was on his back while I was riding him.”

Chuuya glances away and looks like he’s trying to do calculus in his head. Suddenly he fixes him with an expression he can’t quite pin. Maybe exacerbation. “You mean… when you said you ‘rode’ him, you meant it literally?”

“Of course. How else would I have ridden him?”

Chuuya gives a pained laugh before setting his forehead on the table. He straightens back up after a minute. He looks equal parts relieved and exhausted. “Akutagawa-kun, you have

got

to phrase things better. You nearly gave me a heart attack.”

Akutagawa watches, confused, as Chuuya finishes pouring himself another glass. He takes two very large gulps. “You can go home. I’m sorry, but I’m going to be finishing this bottle of wine before taking a cab home. Hopefully, I’ll be passed out by the time I get there.”

Akutagawa nods and gets up from the bench, glancing over his shoulder to see Chuuya absolutely

downing

the wine in his glass. He turns back around and exits the bar. He goes over the conversation in his head and tries to find something wrong with what he said but comes up empty. Maybe Chuuya had a little too much to drink before he even arrived and overreacted. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Akutagawa straightens his back and shoves his hands into his pockets. He revolves to blame this encounter on the jinko. Even though he doesn’t quite understand what happened.

~*~

Dazai bites his lip and grins when he sees the caller ID, already knowing what the call is about. He lets it ring one more time before laying back in his futon and answering. “I didn’t know slugs could use phones.”

“Mackerel, shut the fuck up. I have the most unbelievable story to tell you.”

“Oh?” Dazai thinks back to this afternoon, when Atsushi turned in his report on the mission and Kunikida actually almost had a fit after reading it. When he could see his protegee frown in confusion then turn beet red in understanding and jump to correct the misunderstanding. When Kyouka asked what was going on and Atsushi was frantic to change the conversation, and he himself couldn’t see clearly because he was crying from laughing so hard. “Do tell.”

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

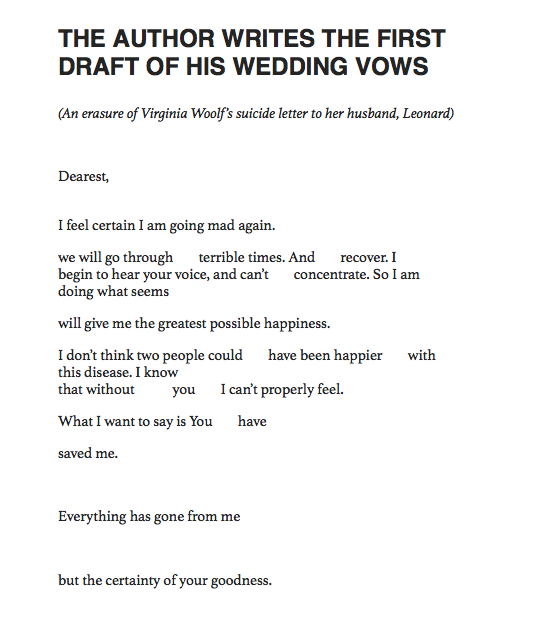

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

When writing academically, the most precise choice is most often the right one. When two words can convey the same idea, the shortest and clearest option is usually the wisest.

The process of choosing what to write involves a lot of consideration. Writing a paper requires choosing a topic, selecting a method, selecting resources, and setting up the main idea; then, when it’s time to write, selecting the words and structuring them.

Choosing the right words seems obvious, but selecting the right words will change your writing tone and content. There are several approaches to consciously choosing words, and we will explore them in this article.

Why is it important to choose the right words when writing?

There are two types of meanings for words: denotative and connotative. Definition and usage are referred to as denotation. Associating, connecting, and using words are described by their connotations. When it comes to using words in academia, these factors can be very important.

When writing a publication, using the right words is essential to its effectiveness. It is imperative to make choices when writing academically, just as when writing in other forms. The phrase, sentence, or even paragraph that most accurately conveys your argument is the first thing you should choose when you’re writing.

Readers are more likely to understand a concept when the word choice is meaningful or striking. The purpose of it is to provide clarity, convey, and enhance concepts. There are several factors that can limit an author’s ability to convey accurate information through their word choice.

Use the right words and the right images together to boost your paper’s potential

Using the right images is just as important as the right words. Beautiful designs and scientifically accurate images can also be decisive when it comes to publishing a successful science paper. Try using Mind the Graph to easily create your visuals and take your work to another level.

The best ways to avoid making mistakes with your word choice

Your reader will have difficulty understanding what you meant when you use misused words or grammar structures. If there is “ambiguity”, “vagueness” or “Unclarity” in these words, they may be ineffective. Writers know what they intend to say, but readers know only what they actually said. Therefore, it is very important to avoid making such mistakes.

Your word choice should always be based on your audience’s understanding. Thus, it is unsuitable to use slang, geographical terms, endearments, and jargon in academic writing. Avoid any phrase that is uncertain about the audience’s understanding.

When proofreading your work, keep your readers’ perspective in mind. Matching the terminology of your subject matter is also important. Clarity and concision are only part of establishing your credibility as an author.

Words can often obscure your meaning if you use too many. A larger amount of material to read and analyze makes it more difficult to read and understand your writing. If your writing has extra words, try to eliminate them.

Keep your tone positive without sounding overly assertive. If you want to brainstorm while you write, you can use the slash/option technique. If you’re stuck on a word or a sentence, write out two or more alternatives. Getting a sense of the right tone of wording for your paper is best done by writing it in at least two ways.

Word choice examples and guide

Jargon

Jargon is an unintuitive, sometimes deliberate way of confusing words or expressions in order to influence a reader’s interpretation. Example: Patients suffered from high fevers and many side effects due to diseases, which they could not handle. (too many words describing the same idea when it could just be a simple sentence,” The disease caused severe symptoms in patients.)

Clichés

When a phrase becomes so common that its meaning is lost, it is called a cliché. A very typical example is “the grass is always greener on the other side” or “last but not least”, do not use it in academic writing.

Big Words

Using big words might sound fancy, but they don’t add meaning rather lead to an inability to comprehend a subject.

Generally used adjectives and adverbs

Appropriate adjectives and adverbs hold quantifiable meanings. Therefore, it is best to use words that describe the context and are accurate.

Wordiness

If your text is too wordy, the reader has to skim through more text to find the main implications of the paper.

Bring words to life with the power of visual

Exactly, we have many templates for every type of science visual communication. Save time by working smarter. The illustrations we offer can be customized to meet your specific needs, and we have a wide range of categories to choose from. With Mind the Graph, science communication is easier than ever before.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual

communication in science.

— Exclusive Guide

— Design tips

— Scientific news and trends

— Tutorials and templates

“Sticks and stones may break your bones, but words can change your brain.” Wait a second, that’s not how I learned it! Many of us grew up reciting some version of this common idiom, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” This childhood chant means that hurtful words cannot cause any physical pain and thus will be ignored. I will speculate and say that as we grew older, we all learned that this chant is not true; words can and do hurt; they can actually change your brain!

Have you ever been on the receiving end of someone’s message where you felt belittled, demeaned, or just walked away questioning yourself? I’m in total support of self-reflection and evaluation, but when someone’s words make you feel horrible about whom you are, that is definitely not ok! Nowadays, people seem to say what they want without censoring or filtering their word choice. It’s one thing to be brutally honest with someone or to offer constructive criticism to someone who wants to hear it, but if it’s shared without regard to the person’s feelings, then the impact could be devastating.

If this negative talk or word choice is what our children are consistently hearing, imagine the impact this can have on them when learning how to express themselves in speaking and writing. More importantly, let’s not forget how word choice can affect the development of their self-esteem. In the book, Words Can Change Your Brain, the authors write, “a single word has the power to influence the expression of genes that regulate physical and emotional stress.” It is our job to teach students the true value of selecting appropriate word choices so that they can develop the necessary tools to make their impact intentional when they communicate. In other words, making mindful word choices can have a positive or negative effect, so teach students to choose their words wisely.

Stay tuned for Part Two to learn how your Shurley English lessons can help your students become mindful communicators in and out of the classroom.

Newberg M.D., Andrew B. Words Can Change Your Brain New York. The Penguin Group.2012

by Rebecca Yauger, @RebeccaYauger

Like many of us, I like to start my mornings with my coffee and a devotional reading. Over the summer, I participated in a Bible study where there was a “verse of the day” pulled from each day’s lesson. Somewhere in the midst of this study, I began looking up the verse of the day using different versions of the Bible, like ESV (English Standard Version), NIV (New International Version), NLT (New Living Translation) and CSB (Christian Standard Bible). While the basic meaning of the verse didn’t change, there were times when the word choice differences brought a whole new depth of meaning and understanding to Scripture. For example, look at Psalms 46:10, a verse is familiar with most Christians. Most versions, including the NIV and NLT say, “Be still and know that I am God.” But the NASB version says, “Cease striving and know that I am God.” And the CSB version states, “Stop fighting, and know that I am God.” Isn’t it interesting that the message is essentially the same? However, to me, there’s greater meaning when studying the various translations of this same verse.

Looking at different Bible versions opened my eyes and had me think about things in a new way.

You may be asking what does this have to do with writing? The short answer is: A lot. Word choice matters. This doesn’t mean every sentence needs to be filled with flowery language and fancy phrases. It does mean that sometimes it’s worth a look at word choice for the main points in your story. Will “stop fighting” or “cease striving” get your point across better than “be still?” Or is “be still” the best choice to propel the story forward and keep the reader turning to the next page.

When you’re editing your manuscript, pay attention to word choice. Are you truly using the best word or phrase to draw the reader in deeper with your character and with your story? Try using different ways of saying things and see what works best for your book. Keep in mind that sometimes simpler is better. However, there are times when you might be surprised at the depth you can achieve by paying attention to word choice.

Rebecca Yauger worked for 15 years in radio and television broadcasting, before starting on her writing career. She’s been published in Chicken Soup for the Soul and Guideposts Magazine and continues to scribble away on various projects. She also blogs at www.TalkingAmongFriends.com. Becky was past Vice-President and Membership Director for American Christian Fiction Writers (www.acfw.com), and currently serves as ACFW’s Web Manager. Becky and her husband live near Dallas, have two grown children, and two beautiful grandchildren.