A

synctironic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished

by the procedure known as the analysis into immediate

constituents

(IC’s). Immediate constituents are any of the two meaningful parts

forming a larger linguistic unity. First suggested by L. Bloomfield1

it was later developed by many linguists.2

The main opposition dealt with is the opposition of stem and affix.

It is a kind of segmentation revealing not the history of the word

but its motivation,

i.e. the data the listener has to go by in understanding it. It goes

without saying that unmotivated words and words with faded motivation

have to be remembered and understood as separate signs, not as

combinations of other signs.

The

method is based on the fact that a word characterised by

morphological divisibility (analysable into morphemes) is involved in

certain

structural correlations. This means that, as Z. Harris puts it, “the

morpheme boundaries in an utterance are determined not on the basis

of considerations interior to the utterance but on the basis of

comparison with other utterances. The comparisons are controlled,

i.e. we do not merely scan various random utterances but seek

utterances which differ from our original one only in stated

portions. The final test is in utterances which are only minimally

different from ours.»3

A

sample analysis which has become almost classical, being repeated

many times by many authors, is L. Bloomfield’s analysis of the word

ungentlemanly.

As

the word is convenient we take the same example. Comparing this word

with other utterances the listener recognises the morpheme -un-

as

a negative prefix because he has often come across words built on the

pattern un-

+

adjective stem: uncertain,

unconscious, uneasy, unfortunate, unmistakable, unnatural. Some

of the cases resembled the word even more closely; these were:

unearthly,

unsightly, untimely, unwomanly and

the like. One can also come across the adjective gentlemanly.

Thus,

at the first cut we obtain the following immediate constituents: un-

+

gentlemanly.

If

we continue our analysis, we see that although gent

occurs

as a free form in low colloquial usage, no such word as lemanly

may

be found either as a free or as a bound constituent, so this time we

have to separate the final morpheme. We are justified in so doing as

there are many adjectives following the pattern noun

stem +

-ly, such

as

womanly, masterly, scholarly, soldierly with

the same semantic relationship of ‘having the quality of the person

denoted by the stem’; we also have come across the noun gentleman

in

other utterances. The two first stages of analysis resulted in

separating a free and a bound form: 1) un~

+ gentlemanly, 2)

gentleman

+ -ly. The

third cut has its peculiarities. The division into gent-+-lemon

is

obviously impossible as no such patterns exist in English, so the cut

is gentle-

+ -man. A

similar pattern is observed in nobleman,

and

so we state adjective

stem

1

L. Language.

London, 1935. P. 210.

2 See:

Nida

E. Morphology.

The Descriptive Analysis of Words. Ann Arbor, 1946. P. 81.

3 Harris

Z.S. Methods

in Structural Linguistics. Chicago, 1952. P. 163.

6* 83

+

man. Now,

the element man

may

be differently classified as

a

semi-affix

(see §

6.2.2) or

as a variant of the free form man.

The

word gentle

is

open to discussion. It is obviously divisible from the etymological

viewpoint: gentle

<

(O)Fr

gentil

<

Lat

gentilis

permits

to discern the root or rather the radical element gent-

and

the suffix -il.

But

since we are only concerned with synchronic analysis this division is

not relevant.

If,

however, we compare the adjective gentle

with

such adjectives as brittle,

fertile, fickle, juvenile, little, noble, subtle and

some more containing the suffix -lei-He

added

to a bound stem, they form a pattern for our case. The bound stem

that remains is present in the following group: gentle,

gently, gentleness, genteel, gentile, gentry, etc.

One

might observe that our procedure of looking for similar utterances

has shown that the English vocabulary contains the vulgar word gent

that

has been mentioned above, meaning ‘a person pretending to the

status of a gentleman’ or simply’man’, but then there is no such

structure as noun

stem +

—le,

so the word gent

should

be interpreted as a shortening of gentleman

and

a homonym of the bound stem in question.

To sum up: as we break the

word we obtain at any level only two IC’s, one of which is the stem

of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns

characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the

interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages

we obtain the following formula:

un—

+ {[{gent-

+

-le)

+

-man]

+

-ly}

Breaking

a word into its immediate constituents we observe in each cut the

structural order of the constituents (which may differ from their

actual sequence). Furthermore we shall obtain only two constituents

at each cut, the ultimate constituents, however, can be arranged

according to their sequence in the word: un-+gent-+-le+-man+’ly.

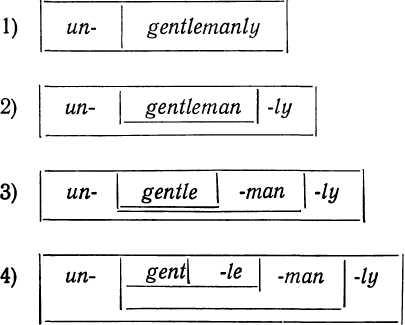

A

box-like diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

84

We

can repeat the analysis on the word-formation level showing not only

the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural

pattern on which it is built, this may be carried out in terms of

proportional oppositions. The main requirements are essentially the

same: the analysis must reveal patterns observed in other words of

the same language, the stems obtained after the affix is taken away

should correspond to a separate word, the segregation of the

derivational affix is based on proportional oppositions of words

having the same affix with the same lexical and lexico-grammatical

meaning. Ungentlemanly,

then,

is opposed not to ungentleman

(such

a word does not exist), but to gentlemanly.

Other

pairs similarly connected are correlated with this opposition.

Examples are:

ungentlemanly

___

unfair

__

unkind

__

unselfish

gentlemanly

fair kind selfish

This

correlation reveals the pattern un-

+

adjective

stem.

The

word-formation type is defined as affixational derivation. The sense

of un-

as

used in this pattern is either simply ‘not’, or more commonly

‘the reverse of, with the implication of blame or praise, in the

case of ungentlemanly

it

is blame.

The

next step is similar, only this time it is the suffix that is taken

away:

gentlemanly

__

womanly

_

scholarly

gentleman woman

scholar

The

series shows that these adjectives are derived according to the

pattern noun

stem

+

-ly.

The

common meaning of the numerator term is ‘characteristic of (a

gentleman, a woman, a scholar).

The

analysis into immediate constituents as suggested in American

linguistics has been further developed in the above treatment by

combining a purely formal procedure with semantic analysis of the

pattern. A semantic check means, for instance, that we can

distinguish the type gentlemanly

from

the type monthly,

although

both follow the same structural pattern noun

stem +

-ly.

The

semantic relationship is different, as -ly

is

qualitative in the first case and frequentative in the second, i.e.

monthly

means

‘occurring every month’.

This

point is confirmed by the following correlations: any adjective built

on the pattern personal

noun stem+-/#

is

equivalent to ‘characteristic of or ‘having the quality of the

person denoted by the stem’.

gentlemanly

-*having

the qualities of a gentleman

masterly

— shaving

the qualities of a master

soldierly

—

shaving the qualities of a soldier

womanly

—

shaving the qualities of a woman

Monthly

does

not fit into this series, so we write: monthly

±5

having

the qualities of a month

85

On

the other hand, adjectives of this group, i.e. words built on the

pattern stem

of a noun denoting a period of time +

—ly

are all equivalent to the formula ‘occurring every period of time

denoted by the stem’:

monthly

→

occurring

every month hourly

→ occurring

every hour

yearly

→ occurring

every year

Gentlemanly

does

not show this sort of equivalence, the transform is obviously

impossible, so we write:

gentlemanly

↔

occurring

every gentleman

The

above procedure is an elementary case of the transformational

analysis,

in which the semantic similarity or difference of words is revealed

by the possibility or impossibility of transforming them according to

a prescribed model and following certain rules into a different form,

called their transform.

The conditions of equivalence between the original form and the

transform are formulated in advance. In our case the conditions to be

fulfilled are the sameness of meaning and of the kernel morpheme.

E.Nida

discusses another complicated case: untruly

adj

might, it seems, be divided both ways, the IC’s being either

un-+truly

or

un-true+-ly.

Yet

observing other utterances we notice that the prefix un-

is

but rarely combined with adverb stems and very freely with adjective

stems; examples have already been given above. So we are justified in

thinking that the IC’s are untrue+-ly.

Other

examples of the same pattern are: uncommonly,

unlikely.1

There

are, of course, cases, especially among borrowed words, that defy

analysis altogether; such are, for instance, calendar,

nasturtium or

chrysanthemum.

The

analysis of other words may remain open or unresolved. Some

linguists, for example, hold the view that words like pocket

cannot

be subjected to morphological analysis. Their argument is that though

we are justified in singling out the element -et,

because

the correlation may be considered regular (hog

:

: hogget,

lock :

: locket),

the

meaning of the suffix being in both cases distinctly diminutive, the

remaining part pock-

cannot

be regarded as a stem as it does not occur anywhere else. Others,

like Prof. A.I. Smirnitsky, think that the stem is morphologically

divisible if at least one of its elements can be shown to belong to a

regular correlation. Controversial issues of this nature do not

invalidate the principles of analysis into immediate constituents.

The second point of view seems more convincing. To illustrate it, let

us take the word hamlet

‘a

small village’. No words with this stem occur in present-day

English, but it is clearly divisible diachronically, as it is derived

from OFr hamelet

of

Germanic origin, a diminutive of hamel,

and

a cognate of the English noun home.

We

must not forget that hundreds of English place names end in -ham,

like

Shoreham,

Wyndham, etc.

Nevertheless, making a mixture of historical and structural approach

1

Nida

E. Morphology,

p.p. 81-82.

86

86

will

never do. If we keep to the second, and look for recurring identities

according to structural procedures, we shall find the words booklet,

cloudlet, flatlet, leaflet, ringlet, town let, etc.

In all these -let

is

a clearly diminutive suffix which does not contradict the meaning of

hamlet.

A.I.

Smirnitsky’s approach is, therefore, supported by the evidence

afforded by the language material, and also permits us to keep within

strictly synchronic limits.

Now we can make one more

conclusion, namely, that in lexicological analysis words may be

grouped not only according to their root morphemes but according to

affixes as well.

The

whole procedure of the analysis into immediate constituents is

reduced to the recognition and classification of same and different

morphemes and same and different word patterns. This is precisely why

it permits the tracing and understanding of the vocabulary system.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

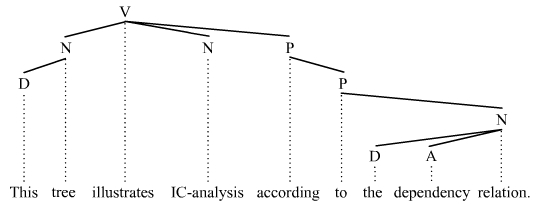

In linguistics, immediate constituent analysis or IC analysis is a method of sentence analysis that was first mentioned by Leonard Bloomfield[1] and developed further by Rulon Wells.[2] The process reached a full-blown strategy for analyzing sentence structure in the early works of Noam Chomsky.[3] The practice is now widespread. Most tree structures employed to represent the syntactic structure of sentences are products of some form of IC-analysis. The process and result of IC-analysis can, however, vary greatly based upon whether one chooses the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars (= constituency grammars) or the dependency relation of dependency grammars as the underlying principle that organizes constituents into hierarchical structures.

IC-analysis in phrase structure grammars[edit]

Given a phrase structure grammar (= constituency grammar), IC-analysis divides up a sentence into major parts or immediate constituents, and these constituents are in turn divided into further immediate constituents.[4] The process continues until irreducible constituents are reached, i.e., until each constituent consists of only a word or a meaningful part of a word. The end result of IC-analysis is often presented in a visual diagrammatic form that reveals the hierarchical immediate constituent structure of the sentence at hand. These diagrams are usually trees. For example:

This tree illustrates the manner in which the entire sentence is divided first into the two immediate constituents this tree and illustrates IC-analysis according to the constituency relation; these two constituents are further divided into the immediate constituents this and tree, and illustrates IC-analysis and according to the constituency relation; and so on.

An important aspect of IC-analysis in phrase structure grammars is that each individual word is a constituent by definition. The process of IC-analysis always ends when the smallest constituents are reached, which are often words (although the analysis can also be extended into the words to acknowledge the manner in which words are structured). The process is, however, different in dependency grammars, since many individual words do not end up as constituents in dependency grammars.

IC-analysis in dependency grammars[edit]

As a rule, dependency grammars do not employ IC-analysis, as the principle of syntactic ordering is not inclusion but, rather, asymmetrical dominance-dependency between words. When an attempt is made to incorporate IC-analysis into a dependency-type grammar, the results are some kind of a hybrid system. In actuality, IC-analysis is different in dependency grammars.[5] Since dependency grammars view the finite verb as the root of all sentence structure, they cannot and do not acknowledge the initial binary subject-predicate division of the clause associated with phrase structure grammars. What this means for the general understanding of constituent structure is that dependency grammars do not acknowledge a finite verb phrase (VP) constituent and many individual words also do not qualify as constituents, which means in turn that they will not show up as constituents in the IC-analysis. Thus in the example sentence This tree illustrates IC-analysis according to the dependency relation, many of the phrase structure grammar constituents do not qualify as dependency grammar constituents:

This IC-analysis does not view the finite verb phrase illustrates IC-analysis according to the dependency relation nor the individual words tree, illustrates, according, to, and relation as constituents.

While the structures that IC-analysis identifies for dependency and constituency grammars differ in significant ways, as the two trees just produced illustrate, both views of sentence structure acknowledge constituents. The constituent is defined in a theory-neutral manner:

-

- Constituent

- A given word/node plus all the words/nodes that that word/node dominates

This definition is neutral with respect to the dependency vs. constituency distinction. It allows one to compare the IC-analyses across the two types of structure. A constituent is always a complete tree or a complete subtree of a tree, regardless of whether the tree at hand is a constituency or a dependency tree.

Constituency tests[edit]

The IC-analysis for a given sentence is arrived at usually by way of constituency tests. Constituency tests (e.g. topicalization, clefting, pseudoclefting, pro-form substitution, answer ellipsis, passivization, omission, coordination, etc.) identify the constituents, large and small, of English sentences. Two illustrations of the manner in which constituency tests deliver clues about constituent structure and thus about the correct IC-analysis of a given sentence are now given. Consider the phrase The girl in the following trees:

The acronym BPS stands for «bare phrase structure», which is an indication that the words are used as the node labels in the tree. Again, focusing on the phrase The girl, the tests unanimously confirm that it is a constituent as both trees show:

-

- …the girl is happy — Topicalization (invalid test because test constituent is already at front of sentence)

- It is the girl who is happy. — Clefting

- (The one)Who is happy is the girl. — Pseudoclefting

- She is happy. — Pro-form substitution

- Who is happy? —The girl. — Answer ellipsis

Based on these results, one can safely assume that the noun phrase The girl in the example sentence is a constituent and should therefore be shown as one in the corresponding IC-representation, which it is in both trees. Consider next what these tests tell us about the verb string is happy:

-

- *…is happy, the girl. — Topicalization

- *It is is happy that the girl. — Clefting

- *What the girl is is happy. — Pseudoclefting

- *The girl so/that/did that. — Pro-form substitution

- What is the girl? -*Is happy. — Answer ellipsis

The star * indicates that the sentence is not acceptable English. Based on data like these, one might conclude that the finite verb string is happy in the example sentence is not a constituent and should therefore not be shown as a constituent in the corresponding IC-representation. Hence this result supports the IC-analysis in the dependency tree over the one in the constituency tree, since the dependency tree does not view is happy as a constituent.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Concerning Bloomfield’s understanding of IC analysis, see Bloomfield (1933:161).

- ^ Concerning Well’s comprehensive discussion of IC analysis, see Wells (1947).

- ^ For Chomsky’s early understanding of immediate constituents, see Chomsky (1957).

- ^ The basic concept of immediate constituents is widely employed in phrase structure grammars. See for instance Akmajian and Heny (1980:64), Chisholm (1981:59), Culicover (1982:21), Huddleston (1988:7), Haegeman and Guéron (1999:51).

- ^ Concerning dependency grammars, see Ágel et al. (2003/6).

References[edit]

- Akmajian, A. and F. Heny. 1980. An introduction to the principles of transformational syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. New York: Henry Holt ISBN 0-226-06067-5, ISBN 90-272-1892-7

- Chisholm, W. 1981. Elements of English linguistics. New York: Longman.

- Culicover, P. 1982. Syntax, 2nd edition. New York: Academic Press.

- Chomsky, Noam 1957. Syntactic Structures. The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

- Haegeman, L. and J. Guéron. 1999. English grammar: A generative perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Huddleston, R. 1988. English grammar: An outline. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wells, Rulon S. 1947. «Immediate Constituents.» Language: 23. pp. 81–117.

External links[edit]

- Immediate constituent analysis On the Historical Source of Immediate-Constituent Analysis by W. Keith Percival

Immediate constituent analysis:this is used in English and other languages

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

В лингвистике, немедленный составляющий анализ или анализ IC — это метод анализа предложений, который впервые был упомянут Леонард Блумфилд и развит Рулоном Уэллсом. Процесс достиг полноценной стратегии анализа структуры предложений в ранних работах Ноама Хомского. Сейчас такая практика широко распространена. Большинство древовидных структур, используемых для представления синтаксической структуры предложений, являются продуктами некоторой формы IC-анализа. Однако процесс и результат IC-анализа могут сильно различаться в зависимости от того, выбирается ли отношение контингента для грамматик структуры фраз (= грамматик составляющего округа) или отношение зависимости грамматик зависимости как основополагающий принцип, который организует составляющих в иерархические структуры.

Содержание

- 1 IC-анализ в грамматиках структуры фраз

- 2 IC-анализ в грамматиках зависимостей

- 3 Тесты группы интересов

- 4 Примечания

- 5 Ссылки

- 6 Внешние ссылки

IC-анализ в грамматиках структуры фраз

Учитывая грамматику структуры фраз (= грамматика избирательного округа), IC-анализ разделяет предложение на основные части или непосредственные составляющие, и эти составляющие, в свою очередь, разделен на другие непосредственные составляющие. Процесс продолжается до тех пор, пока не будут достигнуты несводимые составляющие, т.е. пока каждая составляющая не будет состоять только из слова или значимой части слова. Конечный результат IC-анализа часто представляется в визуальной диаграммной форме, которая раскрывает иерархическую непосредственную составную структуру рассматриваемого предложения. Эти диаграммы обычно представляют собой деревья. Например:

Это дерево иллюстрирует способ, которым все предложение сначала делится на две непосредственные составляющие этого дерева, и иллюстрирует IC-анализ в соответствии с отношением избирательного округа; эти две составляющие далее делятся на непосредственные составляющие this и tree, и иллюстрируют IC-анализ и в соответствии с отношением электората; и так далее.

Важным аспектом IC-анализа грамматик структуры фраз является то, что каждое отдельное слово по определению является составной частью. Процесс IC-анализа всегда заканчивается, когда достигаются мельчайшие составляющие, которые часто являются словами (хотя анализ также может быть расширен до слов, чтобы понять, каким образом слова структурированы). Однако в грамматиках зависимостей этот процесс сильно отличается, поскольку многие отдельные слова не становятся составными частями в грамматиках зависимостей.

IC-анализ в грамматиках зависимостей

Как правило, грамматики зависимостей не используют IC-анализ, поскольку принцип синтаксического упорядочения — это не включение, а, скорее, асимметричное доминирование-зависимость между словами. Когда делается попытка включить IC-анализ в грамматику типа зависимости, результаты представляют собой своего рода гибридную систему. На самом деле IC-анализ сильно отличается от грамматик зависимостей. Поскольку грамматики зависимостей рассматривают конечный глагол как корень всей структуры предложения, они не могут и не подтверждают первоначальное двоичное разделение subject — предикат предложения, связанное с грамматиками структуры фраз. Для общего понимания составной структуры это означает, что грамматики зависимостей не признают составную часть конечной глагольной фразы (VP), и многие отдельные слова также не квалифицируются как составные, что, в свою очередь, означает, что они не будут отображаются как составляющие в IC-анализе. Таким образом, в примере предложения Это дерево иллюстрирует IC-анализ в соответствии с отношением зависимости, многие из составляющих грамматики структуры фразы не квалифицируются как составляющие грамматики зависимости:

Этот IC-анализ не рассматривает конечную глагольную фразу, иллюстрирующую IC-анализ в соответствии с отношением зависимости или деревом отдельных слов, иллюстрирует, согласно, и отношение как составные части.

В то время как структуры, которые IC-анализ определяет для грамматик зависимостей и контингентов, существенно различаются, как показывают два только что созданных дерева, оба представления структуры предложения признают составляющие. Составляющая определяется теоретически нейтральным образом:

-

- Составляющая

- Заданное слово / узел плюс все слова / узлы, над которыми это слово / узел доминирует

Это определение нейтрально по отношению к зависимости и контингенту различие. Это позволяет сравнивать IC-анализы двух типов структур. Составляющая — это всегда полное дерево или полное поддерево дерева, независимо от того, является ли данное дерево составной частью или деревом зависимостей.

Тесты избирательных округов

IC-анализ для данного предложения обычно достигается посредством тестов избирательных округов. Тесты констант (например, актуализация, расщепление, псевдослефтинг, проформная замена, многоточие в ответах, пассивизация, упущение, координация и т. Д.) определить составные части английских предложений, большие и маленькие. Теперь даны две иллюстрации того, как тесты контингента дают ключи к составной структуре и, таким образом, к правильному IC-анализу данного предложения. Рассмотрим фразу «Девушка» в следующих деревьях:

Акроним BPS означает «голая структура фразы», что указывает на то, что слова используются в качестве меток узлов в дереве. Опять же, сосредотачиваясь на фразе Девушка, тесты единогласно подтверждают, что она является составной частью, как показывают оба дерева:

-

- … девушка счастлива — Актуализация (неверный тест, потому что тестовая составляющая уже стоит перед предложением)

- Это девушка, которая счастлива. — Расщепление

- (Тот), Кто счастлив, — это девушка . — Псевдоклефтинг

- Она счастлива. — Проформа замещения

- Кто счастлив? — Девушка . — Ответ с многоточием

На основании этих результатов можно с уверенностью предположить, что именная фраза Девушка в примере предложения является составной частью и, следовательно, должна отображаться как единое целое в соответствующем IC-представлении, которое есть в обоих деревья. Рассмотрим далее, что эти тесты говорят нам о строке глагола «счастлива»:

-

- *… счастлив, девочка. — Актуализация

- * рада, что девушка. — Расщепление

- * Что за девушка счастлива . — Псевдоклефтинг

- * Девушка так / то / сделала то . — Проформа подстановки

- Что за девушка? — * Рада . — Ответ с многоточием

Звездочка * указывает, что предложение не является приемлемым для английского языка. Основываясь на данных, подобных этим, можно сделать вывод, что конечная строка глагола счастлива в примере предложения не является составной частью и, следовательно, не должна отображаться как составная часть в соответствующем IC-представлении. Следовательно, этот результат поддерживает IC-анализ в дереве зависимостей по сравнению с анализом в дереве постоянных групп, поскольку дерево зависимостей не видит счастья как составной части.

Примечания

Ссылки

- Акмаджян А. и Ф. Хени. 1980. Введение в принцип трансформационного синтаксиса. Кембридж, Массачусетс: The MIT Press.

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Эромс, П. Хеллвиг, Х. Герингер и Х. Лобин (ред.) 2003/6. Зависимость и валентность: международный справочник современных исследований. Берлин: Вальтер де Грюйтер.

- Блумфилд, Леонард. 1933. Язык. Нью-Йорк: Генри Холт ISBN 0-226-06067-5, ISBN 90-272-1892-7

- Чисхолм, В. 1981. Элементы Английская лингвистика. Нью-Йорк: Longman.

- Culicover, P. 1982. Syntax, 2nd edition. Нью-Йорк: Academic Press.

- Хомский, Ноам, 1957. Синтаксические структуры. Гаага / Париж: Mouton.

- Haegeman, L. и J. Guéron. 1999. Английская грамматика: генеративная перспектива. Оксфорд, Великобритания: Blackwell Publishers.

- Хаддлстон, Р. 1988. Грамматика английского языка: план. Кембридж, Великобритания: Cambridge University Press.

- Wells, Rulon S. 1947. «Непосредственные составляющие». Язык: 23. стр. 81–117.

Внешние ссылки

- Анализ непосредственных составляющих Об историческом источнике анализа непосредственных составляющих У. Кейт Персиваль

Анализ непосредственных составляющих: это используется на английском и других языках

Immediate constituent analysis : A method in Grammatical analysis

In linguistics, immediate constituent analysis or IC analysis is a method of sentence analysis that was first mentioned by Leonard Bloomfield, and developed further by Rulon Wells. The process reached a full blown strategy for analyzing sentence structure in the early works of Noam Chomsky.The practice is now widespread. Most tree structures employed to represent the syntactic structure of sentences are products of some form of IC-analysis. The process and result of IC-analysis can, however, vary greatly based upon whether one chooses the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars (= constituency grammars) or the dependency relation of dependency grammars as the underlying principle that organizes constituents into hierarchical structures.

IC-analysis in phrase structure grammars

Given a phrase structure grammar (= constituency grammar), IC-analysis divides up a sentence into major parts or immediate constituents, and these constituents are in turn divided into further immediate constituents. The process continues until irreducible constituents are reached, i.e., until each constituent consists of only a word or a meaningful part of a word. The end result of IC-analysis is often presented in a visual diagrammatic form that reveals the hierarchical immediate constituent structure of the sentence at hand. These diagrams are usually trees. For example:

This tree illustrates the manner in which the entire sentence is divided first into the two immediate constituents this tree and illustrates IC-analysis according to the constituency relation; these two constituents are further divided into the immediate constituents this and tree, and illustrates IC-analysis and according to the constituency relation; and so on.

An important aspect of IC-analysis in phrase structure grammars is that each individual word is a constituent by definition. The process of IC-analysis always ends when the smallest constituents are reached, which are often words (although the analysis can also be extended into the words to acknowledge the manner in which words are structured). The process is, however, much different in dependency grammars, since many individual words do not end up as constituents in dependency grammars.

Illustration:

1 . Un gentlemanly

This will be broken down into un-gentlemanly —-> un- gentleman-ly —-> un-gentle-man-ly—–> un-gentl-e-man-ly

un + { [(gentle- + le ) + man ] + -ly

As we break the word we obtain at any level only two immediate constituents (IC)s, one of which is the stem of any given word.

Constituent

A given word/node plus all the words/nodes that that word/node dominates

This definition is neutral with respect to the dependency vs. constituency distinction. It allows one to compare the IC-analyses across the two types of structure. A constituent is always a complete tree or a complete subtree of a tree, regardless of whether the tree at hand is a constituency or a dependency tree.

Constituency tests

The IC-analysis for a given sentence is arrived at usually by way of constituency tests. Constituency tests (e.g. topicalization, clefting, pseudoclefting, pro-form substitution, answer ellipsis, passivization, omission, coordination, etc.) identify the constituents, large and small, of English sentences. Two illustrations of the manner in which constituency tests deliver clues about constituent structure and thus about the correct IC-analysis of a given sentence are now given. Consider the phrase The girl in the following trees:

The acronym BPS stands for “bare phrase structure”, which is an indication that the words are used as the node labels in the tree. Again, focusing on the phrase The girl, the tests unanimously confirm that it is a constituent as both trees show:

…the girl is happy – Topicalization (invalid test because test constituent is already at front of sentence)

It is the girl who is happy. – Clefting

(The one)Who is happy is the girl. – Pseudoclefting

She is happy. – Pro-form substitution

Who is happy? -The girl. – Answer ellipsis

Based on these results, one can safely assume that the noun phrase The girl in the example sentence is a constituent and should therefore be shown as one in the corresponding IC-representation, which it is in both trees. Consider next what these tests tell us about the verb string is happy:

*…is happy, the girl. – Topicalization

*It is is happy that the girl. – Clefting

*What the girl is is happy. – Pseudoclefting

*The girl so/that/did that. – Pro-form substitution

What is the girl? -*Is happy. – Answer ellipsis

The star * indicates that the sentence is bad (i.e. it is not acceptable English). Based on data like these, one might conclude that the finite verb string is happy in the example sentence is not a constituent and should therefore not be shown as a constituent in the corresponding IC-representation. Hence this result supports the IC-analysis in the dependency tree over the one in the constituency tree, since the dependency tree does not view is happy as a constituent.

In summary:

Immediate constituent analysis is a form of linguistic review that breaks down longer phrases or sentences into their constituent parts, usually into single words. This kind of analysis is sometimes abbreviated as IC analysis, and gets used extensively by a wide range of language experts. This kind of exploration of language has applications for both societal or traditional linguistics, and natural language processing in technology fields.

For those who use this kind of analysis to examine text or speech, immediate constituent analysis often requires separating parts of a sentence or phrase into groups of words with semantical synergy or related meaning. For example, the sentence, “the car is fast,” could be broken down into two groups of words: “the car” and “is fast.” In this case, the first group contains an article applied to a noun, and the second group contains a verb followed by a defining adjective.

Many kinds of immediate constituent analysis include multi-step processing. For the example above, the two groups of words could be split up further into individual words. Reviewers might consider how the article “the” applies to the word “car,” for instance, in specifying one particular car, and how the adjective “fast” describes the verb “is,” in this case, in a simple, rather than a comparative or superlative sense.

References

Akmajian, A. and F. Heny. 1980. An introduction to the principle of transformational syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. New York: Henry Holt ISBN 0-226-06067-5, ISBN 90-272-1892-7