Download Article

Download Article

Maybe you are in the middle of an exam and suddenly come across a word that makes absolutely no sense. This is usually a cue for most people to panic if a dictionary is not handy. But don’t worry! There are several steps you can take to help you figure out the meaning of a word without a dictionary.

-

1

Read the entire sentence. It can be very frustrating to have your reading interrupted by an unknown word. If you are in the middle of an exam or an assignment for school or work, it can also be very stressful. If you can’t reach for a dictionary, take other steps to figure out what the word means.

- Your first step is to go back and re-read the entire sentence. You probably lost track of what your were reading when you stumbled upon the new word.

- Think about the content of the sentence. Do you understand the sentence without using the new word? Or is it incomprehensible?

- Try underlining the unknown word. This will help you separate it from the rest of the sentence.

-

2

Identify words you do understand. You can often use other words in the sentence to help you define the unknown word. Think about what else is happening in the sentence. Hopefully, this will help you figure out whether the unknown word is a noun, verb, or adjective.

- For example, maybe you are looking at a sentence that says, «It was a very sultry day in the middle of the summer.» You probably understand each word except for «sultry».

- Think about what you know about the summer. It is likely that «sultry» has something to do with weather.

- Maybe your biology exam has this sentence, «Many members of the canine family are predators, looking for other animals to eat.» You can surmise that «predators» prey on other animals.

Advertisement

-

3

Look for illustrative examples. Once you have examined the other words in that sentence, you can move on. Start looking at the sentences that follow the unknown word. An author will often give descriptions that can help you figure out the meaning of an unknown word.[1]

- For example, take the sentence, «It was a very sultry day in the middle of summer.» It could be followed by the sentence, «The heat and humidity made it appealing to sit in the shade and drink lemonade.»

- You can now more confidently define «sultry». The descriptive words such as «heat» and «humidity» are further clues that it is a description of the weather.

- Sometimes, the descriptive examples will be right in the original sentence. For example, it could say, «Sultry days are so damp and hot.»

-

4

Think logically. Sometimes, the context clues will not be as clear. You will have to use logic to figure out the word. You can also use experience, or prior knowledge, of the topic.[2]

- For example, maybe a sentence says, «In the antebellum South, many plantation owners kept slaves.» It is likely that «antebellum» is the unknown word.

- The sentence itself does not offer many clues. However, the following sentences are, «But after the Civil War, slavery was outlawed. This was a major change between the two periods.»

- Think about what you know now. You are reading information about two different time periods, right? Before the Civil War and after the Civil War.

- You can now make a pretty logical assumption about the word «antebellum». Based on your experience and reading the following sentences, you know it probably means «before the war».

-

5

Use other context clues. Sometimes an author will offer other types of clues. Look for restatement. This is where the meaning of the word is restated in other words.

- Here is an example of «restatement»: «The pig squealed in pain. The high-pitched cry was very loud.»

- You can also look for «appositives». This is where an author highlights a specific word by placing a further description between two commas.

- This is an example of the use of an appositive: «The Taj Mahal, which is a massive white marble mausoleum, is one of the most famous landmarks in India.

- You may not know the words «Taj Mahal», but the use of appositives makes it clear that it is a landmark.

Advertisement

-

1

Look for a prefix. Etymology is the study of the meanings of words. It also looks at the origins of words, and how they have changed over time. By learning about etymology, you can find new ways to define unknown words without using a dictionary.

- Start by looking at each part of the word in question. It is very helpful to look to see if the word has a common prefix.

- Prefixes are the first part of the word. For example, a common prefix is «anti».

- «Anti» means «against». Knowing this should help you figure out the meanings of words such as «antibiotic» or «antithesis».

- «Extra» is a prefix that means «beyond». Use this to figure out words such as «extraterrestrial» or «extracurricular».

- Other common prefixes are «hyper», «intro», «macro» and «micro». You can also look for prefixes such as «multi», «neo» and «omni».

-

2

Pay attention to the suffix. The suffix are the letters at the end of the word. There are several suffixes in the English language that are common. They can help you figure out what kind of word you are looking at.

- Some suffixes indicate a noun. For example, «ee» at the end of the word almost always indicates a noun. Some examples are «trainee» and «employee».

- «-ity» is also a common suffix for a noun. Examples include «electricity» and «velocity».

- Other suffixes indicate verbs. For example, «-ate». This is used in words such as «create» and «deviate».

- «-ize» is another verb suffix. Think about the words «exercise» and «prioritize».

-

3

Identify root words. A root word is the core word, without a prefix or suffix. Most words in the English language come from either a Latin or Greek root word.[3]

- By learning common root words, you can begin to identify new words more easily. You will also be able to recognize words that have had a prefix or suffix added.

- An example of a root word is «love». You can add many things to the word: «-ly» to make «lovely».

- «Bio» is a Greek root word. It means «life, or living matter». Think about how we have adapted this root word to become «biology», «biography», or «biodegradable».

- The root word mater- or matri- comes from the Latin word mater, meaning mother. By understanding this root, you can better understand the definitions of words like matron, maternity, matricide, matrimony, and matriarchal.

Advertisement

-

1

Keep notes. If you can increase the size of your vocabulary, you will find yourself less likely to encounter unknown words. There are several steps you can take to effectively build your vocabulary. For example, you can start by writing notes.

- Every time you encounter an unfamiliar word, write it down. Then later, when you have access to a dictionary, you can look it up for a precise definition.

- Keep a small pack of sticky notes with you while you read. You can write the unfamiliar word on a note and just stick it on the page to return to later.

- Start carrying a small notebook. You can use it to keep track of words that you don’t know and new words that you have learned.

-

2

Utilize multiple resources. There are a lot of tools that you can use to help you build your vocabulary. The most obvious is a dictionary. Purchase a hard copy, or book mark an online dictionary that you find useful.

- A thesaurus can also be very helpful. It will give you synonyms for all of the new words you are learning.

- Try a word of the day calendar. These handle desk tools will give you a new word to learn each day. They are available online and at bookstores.

-

3

Read a lot. Reading is one of the best ways to increase the size of your vocabulary. Make it a point to read each day. Both fiction and non-fiction will be helpful.

- Novels can expose you to new words. For example, reading the latest legal thriller will likely expose you to some legal jargon you’ve never heard before.

- Read the newspaper. Some papers even have a daily feature that highlights language and explores the meanings of words.

- Make time to read each day. You could make it a point to scroll through the news while you drink your morning coffee, for example.

-

4

Play games. Learning can actually be fun! There are many enjoyable activities that can help you to build your vocabulary. Try doing crossword puzzles.

- Crossword puzzles are a great way to learn new words. They will also stretch your brain by giving you interesting clues to figure out the right word.

- Play Scrabble. You’ll quickly learn that unusual words can often score the most points.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

Is there a list of prefixes/suffixes, or a simple etymology handbook, that I can obtain from the Internet or someplace else?

I’m sure there are many! Check websites like Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or other booksellers who might sell grammar handbooks. You could also try checking your local book stores.

-

Question

How does one find out and understand the formation of words?

If you can recognize the prefixes, suffixes, and anything else that might alter the root word, then you’ll know how the root is being altered. For example, ‘amuse’ is made up of ‘a’ as in ‘not’ and ‘muse’ referring to ponderous thought. Even if you don’t recognize the root ‘muse’ because it’s a more archaic term, you know that the ‘a’ inverses it’s meaning.

-

Question

How can I know the exact meaning of a word using dictionaries from many leanings given?

Substitute each meaning into the sentence where you encountered the word, and see which definition makes the most sense within the context of that sentence.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

-

Keep a notebook. This could be useful if you come across a word that you want to learn later, if you want to list any words that share suffixes or prefixes (both of which are known as «roots», which also include anything that goes into the middle.)

-

Read etymology dictionaries. They are found online and presumably in bookstores if you look hard enough.

-

Make your own notes in your personal English notebook to remember important points later on.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To understand a word without a dictionary, try re-reading the entire sentence to see if the context helps you to find out what the word means. If it’s unclear, try to figure it out by thinking about the meaning of the words you’re familiar with, since the unknown word might have a similar meaning. Additionally, look for common prefixes in words, such as «anti,» which means against, or «extra,» which means beyond. Next, check the following sentences for clues, such as the topic the word is related to. Alternatively, keep a list of unknown words so you can check them in a dictionary at a later date. For tips on how to identify root words and how to learn words by doing crossword puzzles, read on!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 215,260 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Aaron Junior

Jul 26, 2016

«This article has really helped me especially finding the meaning of the word using prefixes, suffixes, and word…» more

Did this article help you?

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

пойму ни слова

чтобы понять слово

If somebody walks into the room and starts speaking Swahili, I’m not going to understand a word.

Если сейчас кто-нибудь зайдёт в эту комнату и начнёт говорить на суахили, я не пойму ни слова.

Now you won’t be able to understand a word of it, but this is what it looks like.

My mother is probably sat at home now watching this, not able to understand a word of what I am saying but very proud.

Моя мама, безусловно, сейчас смотрит эту пресс-конференцию и не в состоянии вымолвить ни слова, но очень мной гордится.

As a child, he used to tune into foreign radio stations — despite not being able to understand a word.

Ребенком он настраивал свой радиоприемник на иностранные радиостанции, хотя и не мог понять ни слова.

It’s not enough to understand a word after five seconds of trying to find the answer; it has to just be there.

Не достаточно, чтобы понять слово после пяти секунд, пытаясь найти ответ; Он должен быть там.

I did not speak Spanish at the time and was not able to understand a word he was saying.

Я тогда совсем не говорил по-английски и не понял ни слова из того, что он мне сказал.

Without such means, it is impossible for us humans to understand a word of it, and to be without them is to wonder around in vain through a dark labyrinth.

Без этих средств невозможно человеку понять ни слова, без них мы тщетно блуждаем в темном лабиринте».

The Frenchman, even to learn English in school, can pretend not to understand a word in English.

Француз, даже изучавший английский язык в школе, может притвориться, что не понимает ни слова по-английски.

Armed with a press pass, I actually spoke to Benzema after that game, in French, and he didn’t appear to understand a word I said.

Вооруженный пресс-картой я поговорил с Бензема после того матча на французском, но кажется, он не понял ни слова из того, что я сказал.

Well, if you want any of the farmers to understand a word you’re

Mrs Anderson did not seem to understand a word of Russian or English, the two languages all the four sisters had spoken since babyhood.

Похоже на то, что госпожа Андерсон не понимала ни слова ни по-русски, ни по-английски — то есть на тех языках, на которых все четыре мои племянницы разговаривали с младенческих лет.

«Try to understand a word‘s meaning from its context.»

I shall probably be too deaf to hear, and too old to understand a word you say, but I shall still be your affectionate Godfather, C. S. Lewis. — 969 likes

Наверное, я к тому времени буду уже глухим и не услышу ни единого слова и слишком старым, что понять, о чём ты будешь говорить, но я по-прежнему буду» — любящим тебя крёстным отцом К. С. Льюисом

I shall probably be too deaf to hear, and too old to understand a word you say but I shall still be, your affectionate Godfather,

Возможно, к тому времени я так состарюсь, что не услышу и не пойму ни слова, но и тогда я по-прежнему буду любящим тебя крёстным.

To understand a word, we need to hear its phonems at first.

To understand a word is to understand a language

Результатов: 16. Точных совпадений: 16. Затраченное время: 97 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Every teacher wonders how to teach a word to students, so that it stays with them and they can actually use it in the context in an appropriate form. Have your students ever struggled with knowing what part of the speech the word is (knowing nothing about terminologies and word relations) and thus using it in the wrong way? What if we start to teach learners of foriegn languages the basic relations between words instead of torturing them to memorize just the usage of the word in specific contexts?

Let’s firstly try to recall what semantic relations between words are. Semantic relations are the associations that exist between the meanings of words (semantic relationships at word level), between the meanings of phrases, or between the meanings of sentences (semantic relationships at phrase or sentence level). Let’s look at each of them separately.

Word Level

At word level we differentiate between semantic relations:

- Synonyms — words that have the same (or nearly the same) meaning and belong to the same part of speech, but are spelled differently. E.g. big-large, small-tiny, to begin — to start, etc. Of course, here we need to mention that no 2 words can have the exact same meaning. There are differences in shades of meaning, exaggerated, diminutive nature, etc.

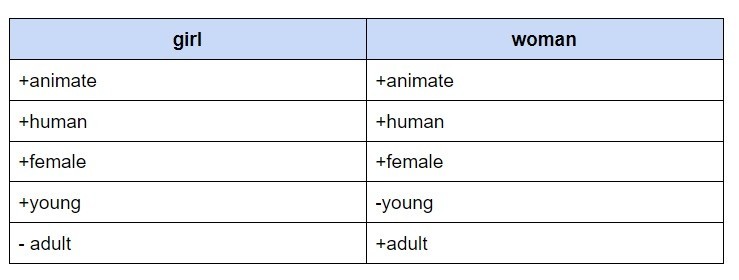

- Antonyms — semantic relationship that exists between two (or more) words that have opposite meanings. These words belong to the same grammatical category (both are nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). They share almost all their semantic features except one. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1998) E.g.

- Homonyms — the relationship that exists between two (or more) words which belong to the same grammatical category, have the same spelling, may or may not have the same pronunciation, but have different meanings and origins. E.g. to lie (= to rest) and to lie (= not to tell the truth); When used in a context, they can be misunderstood especially if the person knows only one meaning of the word.

Other semantic relations include hyponymy, polysemy and metonymy which you might want to look into when teaching/learning English as a foreign language.

At Phrase and Sentence Level

Here we are talking about paraphrases, collocations, ambiguity, etc.

- Paraphrase — the expression of the meaning of a word, phrase or sentence using other words, phrases or sentences which have (almost) the same meaning. Here we need to differentiate between lexical and structural paraphrase. E.g.

Lexical — I am tired = I am exhausted.

Structural — He gave the book to me = He gave me the book.

- Ambiguity — functionality of having two or more distinct meanings or interpretations. You can read more about its types here.

- Collocations — combinations of two or more words that often occur together in speech and writing. Among the possible combinations are verbs + nouns, adjectives + nouns, adverbs + adjectives, etc. Idiomatic phrases can also sometimes be considered as collocations. E.g. ‘bear with me’, ‘round and about’, ‘salt and pepper’, etc.

So, what does it mean to know a word?

Knowing a word means knowing all of its semantic relations and usages.

Why is it useful?

It helps to understand the flow of the language, its possibilities, occurrences, etc.better.

Should it be taught to EFL learners?

Maybe not in that many details and terminology, but definitely yes if you want your learners to study the language in depth, not just superficially.

How should it be taught?

Not as a separate phenomenon, but together with introducing a new word/phrase, so that students have a chance to create associations and base their understanding on real examples. You can give semantic relations and usages, ask students to look up in the dictionary, brainstorm ideas in pairs and so on.

Let us know what you do to help your students learn the semantic relations between the words and whether it helps.

Learn Only What Has Meaning To You

Here are some things we often hear from English learners:

“I couldn’t read it. There were too many new words and I didn’t have time to look them all up in the dictionary.”

“I wrote down all of these new words and I tried to learn them, but I can’t remember any of them now!”

Sound familiar?

Here’s a fact about your brain: your brain is very good at throwing away things it doesn’t need.

Vocabulary learning starts when you choose which words and phrases to learn or not learn.

This is where many English learners go wrong, by making one of these mistakes:

- Trying to learn too many words.

- Trying to learn words you don’t need.

- Trying to learn big lists of words.

- Trying to learn words you don’t know how to use.

To avoid these mistakes, you need to choose the vocabulary you study carefully.

Most importantly, if you want to remember new words and new English vocabulary, you need to learn things which are useful or meaningful to you.

If you read a text, and you try to look up every word you don’t know, of course you’ll forget most of them. Most of the words you look up probably won’t be useful to you, and so your brain won’t hold onto them.

If you write down a list of 100 new words and try to learn them, the words won’t mean much to you. They’re just a list on a piece of paper—totally abstract, and also boring! Our brains don’t like boring. Boring gets forgotten, fast.

So, what’s the solution?

Only learn a word or phrase if it’s really useful or meaningful to you in some way.

For example:

Your teacher keeps using a word that you don’t know. You hear it several times, but you can’t work out what it means. Then, you hear other people use the same word. You’re curious: what is this word you keep hearing?

You’re reading a really interesting article. You don’t know every word, but you can understand the general ideas. In one paragraph, there’s a word which you don’t know, and which makes it difficult for you to understand the idea of the paragraph. You think the paragraph is important to the article, and you’re interested to know what it means.

You’re on holiday in a country where English is widely spoken. There’s one kind of food you really want to order, but you don’t know the word in English.

These are situations where a new word will have meaning to you. If you look up words in situations like these, you’re more likely to remember them.

Firstly, you’ll remember them because these are words you need to use.

Secondly, you’ll remember them because these are all situations which involve your feelings in some way. In the first example, you’re curious about something. In the second, you’re interested in the article you’re reading. In the third situation, you’re (hopefully) having fun on holiday.

So, this is the first and most important point. Learn words and phrases which are useful and meaningful for you. This gives you the best chance to remember and use what you learn.

Now, another important point: when you say, “I learned a new word,” you could mean one of two things.

You could mean that you learned to understand a new word, or you could mean that you learned to use a new word. Those two things are different.

Let’s talk about that!

2. Learning Active Vocabulary vs. Learning Passive Vocabulary

You might have heard the terms ‘passive vocabulary’ and ‘active vocabulary’.

Your passive vocabulary means words you can understand, but you don’t use.

Your active vocabulary means words you can use in your speech or writing.

It’s normal that your passive vocabulary is larger than your active vocabulary in any language, including your native language.

Many English learners say, “I can understand words but I can’t use them.” To some extent, this is normal. However, what can you do if you want to develop your active vocabulary in English?

There are two important points here.

First, you need to use different techniques to build passive or active vocabulary. Many English learners have problems building their active vocabulary because the techniques they use to learn vocabulary only increase their passive vocabulary.

Secondly, building active vocabulary takes a lot more time and work. If you want to build your active vocabulary, you need to spend a lot more time studying and practising each word or phrase you want to learn.

Let’s look at the first point. Here are some good techniques for building passive vocabulary:

- Looking up a translation of a word in your language.

- Guessing the meaning of a word from the context.

- Looking up a definition of a word in a monolingual dictionary.

- Finding example sentences.

- Reading and listening.

So, if your vocabulary learning consists of translating everything into your language, don’t be surprised if you can’t use what you learn. This is an okay technique for building your passive vocabulary, but it won’t help you to use the words and phrases you study.

What about building active vocabulary?

Here are some good techniques for building your active vocabulary:

- Writing stories or other things which are personal to you.

- Using a new word several times in several different conversations.

- Making example sentences which are personal to you.

You can see that these things are not necessarily complicated, but they do require more effort.

It’s much harder to write an example sentence which is personal to you than it is to read someone else’s example sentence.

It’s much harder to write a story which means something to you than it is to read something which someone else wrote.

But, if you want to build your active vocabulary, this is how!

Most English learners are more interested in developing their active vocabulary, so in the rest of this lesson, we’ll focus on specific techniques you can use to build your active vocabulary in English.

Let’s start with a very important and powerful idea.

3. Learn Vocabulary in Meaningful Phrases and Sentences

Here’s a question: what is vocabulary?

Did you say ‘words’?

Many people think that ‘vocabulary equals words’. Of course, words are part of vocabulary, but they’re only a part. Vocabulary also includes collocations, phrases, and even full sentences.

Even when you’re learning words, you rarely need single words when you’re speaking. You need to combine the words into phrases and sentences if you want to use them.

So, it makes sense to learn vocabulary in the same way: learn phrases, combinations and sentences, because this is what you need when you’re speaking and writing.

Let’s do an example.

Imagine that you see the word challenge and you want to know what it means. So, you look it up and find the meaning.

Next, your goal is to write five sentences using the word challenge. Each sentence should be different, and each sentence should mean something to you.

Try to write things which relate to your life, your feelings and your thoughts.

You can (and should) also try to use different forms of the word, like the adjective challenging.

You should also research other examples before you write yours. Look for common collocations—word combinations—with the word you want to learn. For example, what adjectives are commonly used with the word challenge?

Think about it. What phrases or sentences could you write with this word?

We’ll give you an example, but remember that you should make your own examples, because they should be personal to you.

Here are five possible sentences:

- I’m bored at work. I need a new challenge.

- Teaching teenagers is fun, but it can be very challenging.

- Running a full marathon was one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced.

- I set myself a challenge last year: to learn German to a native-equivalent level.

- My sister is a really determined person; she’s not someone who’ll run away from a challenge.

We’ll say it again, because it’s the most important point here: whatever you write should be personal to you.

Don’t write a sentence about your sister if you don’t have a sister. Don’t say something about your sister which isn’t true. Make it true, and make it personal.

If it’s personal to you, you’ll remember it. If it isn’t, you’ll forget it. Simple, right?

At this point, there’s one more important thing you should do.

Ask a teacher, a native speaker or a friend who’s very good at English to check your sentences.

You want to make sure you’re learning your new vocabulary correctly, and you need feedback to do that.

You can also see that writing sentences like this lets you learn several useful phrases at one time.

For example, here you have the collocations a new challenge, to face a challenge, a big challenge, to set (yourself) a challenge, and run away from a challenge.

So, if you follow this strategy, you won’t just learn one word, like challenge. You’ll learn several words and phrases together, in a natural way.

Remember that this strategy is personal on both sides: you’re starting with words that are meaningful to you personally, and then you’re learning those words by writing examples which are also meaningful to you personally.

Yes, this needs work, and it might be very different from what you do now. However, if you want an effective way to learn and remember vocabulary, this is it.

If you do things this way, nothing is abstract and nothing is boring. Your brain will remember what you learn because it’s relevant to you, your life and your feelings.

However, if you’re trying to learn a lot of vocabulary, it’s also important to review what you’ve learned regularly. Regular review helps to keep vocabulary fresh in your mind, which will help you to remember the words and phrases you need when you’re speaking or writing in English.

Let’s look at the most effective ways to review your vocabulary.

How to Review and Remember English Vocabulary

If you have a lot of English vocabulary to review and remember, it’s a big, complex job.

But, we have good news! There are several free tools and apps which can make this easy.

You need a digital flashcard app. These apps are designed to help you memorise and review large amounts of information.

Two of the most popular are Anki and Quizlet. You can find links below the video. We aren’t recommending any particular product or company, but many students have used both of these with good results.

We hear that Quizlet is a little easier to use, while Anki is more powerful and has more options, but is also more complex. Try both, or find another program, and see what works for you.

All of these programs work in the same way: they allow you to set questions for yourself.

You create a card with a question and an answer. You can write whatever you want for the question and the answer.

After you see a question and the answer, you decide if the question was easy or difficult for you.

If the question is easy, the app will ask you again after a longer period.

If the question is difficult, the app will ask you the same question again after a shorter period, maybe even the same day.

This is very effective, because it allows you to focus more on the things you don’t know, and it doesn’t waste your time reviewing things you already know well.

You can often download packs of questions that other people have made, but you should make your own questions, using your own, personalised example sentences.

Let’s see how.

Look at the five sentences we wrote before to learn the word challenge:

- I’m bored at work. I need a new challenge.

- Teaching teenagers is fun, but it can be very challenging.

- Running a full marathon was one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced.

- I set myself a challenge last year: to learn German to a native-equivalent level.

- My sister is a really determined person; she’s not someone who’ll run away from a challenge.

Let’s make five questions from these five sentences.

- Question: I’m bored at work. I need ________.

- Answer: I’m bored at work. I need a new challenge.

- Question: Teaching teenagers is fun, but _________.

- Answer: Teaching teenagers is fun, but it can be very challenging.

- Question: I ________ last year: to learn German to a native-equivalent level.

- Answer: I set myself a challenge last year: to learn German to a native-equivalent level.

- Question: Running a full marathon was _________.

- Answer: Running a full marathon was one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced.

- Question: My sister is a really determined person; ________.

- Answer: My sister is a really determined person; she’s not someone who’ll run away from a challenge.

Can you see what’s going on here?

The questions are getting progressively more difficult. For the first question, you only have to remember three words: a new challenge. For the fifth question, you need to remember a whole clause.

After you’ve made your questions, what next?

Review your vocabulary cards or questions every day. We recommend you install Anki, Quizlet or whatever you use on your phone.

This way, you can review vocabulary when you have nothing else to do, for example on the subway or during your lunch break.

Try to use your app and review vocabulary every day, but don’t overload yourself. Limit the number of new questions or cards you see each day. Five new questions per day is a good target.

Again, this takes quite a lot of work. You might think, “Do I really have to do all this just to remember one word?”

Let me ask you some questions in return: do you want to really build your English vocabulary? Do you want to remember new English words that you study? Do you want to learn to use new English vocabulary?

If you answered ‘yes’, ‘yes’, and ‘yes’, then this is how. It takes time and effort, but it also works.

Let’s review the steps you need to take:

- Choose words which are useful and meaningful to you personally; don’t learn big lists of words, and don’t learn words which you won’t use.

- Decide if you want to just understand a word, or if you want to use it. Use different vocabulary-learning techniques depending on what you want.

- If you want to add words to your active vocabulary, then write 3-5 example sentences, using the new word. The sentences should be relevant to you, your life, your thoughts and your feelings.

- Get feedback on your example sentences, from a teacher or friend, to make sure you’re using your new vocabulary correctly.

- Add your example sentences to a digital flashcard app like Quizlet or Anki. Make questions of different difficulty, so that some questions are easier and some are harder.

- Use your digital flashcard app daily, or as often as you can!

Follow these steps and your English vocabulary will increase, you’ll remember new words in English, and you’ll be able to use the new English words you learn.

Next, learn how to use a vocabulary notebook to expand your vocabulary in this free video lesson from Oxford Online Engish!

Thanks for watching!

This post took me over 2 weeks to write and I was researching for days and days and days before I even started typing. That’s because measuring vocabulary is hard! I can calculate a student’s guided reading level like nobody’s business. I can tell you, in great detail, about a student’s spelling strengths and math skills. But when it comes to vocabulary, it’s a bit of a head scratcher. How do I quantify that huge, amorphous mass into a grade? Using the quizzes with our weekly Jargon Journals gave me some data about student understanding of individual words, but what if I want to know about a general vocabulary levels? Is there some sort of benchmark? Is there an easy way to measure if a student understands more than a word’s definition?

Nope.

That’s because vocabulary is like air. Take a second to think about air. You probably haven’t given it much consideration lately. Even though we’re surrounded by it, we take for granted that it even exists. Air is extremely difficult to hold, so if I want to understand the nature of air I may begin by collecting a sample in a bottle. Because air provides little sensory input, based on my sample, I may become convinced that all air is round without realizing that the sample has taken the shape of its container. In this case I’m studying the bottle not the material inside.

It’s the same with vocabulary. It undergirds every communication to the point that it becomes invisible. If we’re looking to measure the richness of a student’s vocabulary, it’s easy to look at one multiple-choice test and assume that we’ve uncovered the sum total of information. But thinking like that takes us right back to analyzing the bottle. Acquiring vocabulary is a fluid process. As one article points out, learning vocabulary is multidimensional, incremental, context dependent, and develops across a lifetime. That’s a lot to consider when designing assessments and, for those reasons, there is no single, perfect measure of vocabulary knowledge. If we want to measure the contents of our vocabulary bottles, we have to rely on more informal assessments. In this post I’ll go over some different vocabulary assessments and ways they may work in your classroom.

Why Are You Assessing?

The first step to measuring vocabulary is to identify your purpose in assessing. What are you hoping to get from this assessment? Why does the information matter? You have to decide if you’re looking to measure vocabulary breadth (the amount of words a student understands) or vocabulary depth (the amount of understanding a student has about a word).

How Are You Assessing?

If you decide that your purpose is to measure vocabulary breadth, then a multiple choice test is an efficient way to quickly measure a student’s understanding of word meaning. If you’re using the Jargon Journals, the end-of-unit quizzes can give you valuable information about which words students are starting to feel comfortable with and which words may need further exposures.

But what if you’re looking for something indicative of vocabulary depth? In that case, a multiple choice format probably isn’t precise enough. You’ll need assessments that tap into layers of understanding.

If we want to assess how much students know about a word, we first have to decide what it actually means to know a word. Often we look at one aspect–definition–and use that as a definitive measure, but recalling meaning is just one part of this vocabulary puzzle. If you’ve ever had students who could tell what a word means, but completely misuse it, you understand. In the book Creating Robust Vocabulary: Frequently Asked Questions & Extended Examples the authors use an example of the word devious. Based on the definition in the dictionary (straying from the right course; not straightforward), you can understand why a student whose experience with this word is limited to the definition may write, “He was devious on his bike.”

Confusion like this happens because knowing a word is not an all-or-nothing situation. Wouldn’t it be nice if it were! Instead, word understanding happens on more of a continuum. On one side we have “I didn’t even know this word existed” on the other side is “I can use this word naturally, automatically, and accurately when speaking and writing.” We’re at different places with different words and it takes time and experience before any word can be utilized at that deeper level. In other words:

…Learning a word is not like turning on a light, where one moment we do not know a word (the light is off), and the next moment we suddenly learn the word completely (the light is on). Learning word meanings is more like a dimmer switch on a light; we learn words gradually as the light slowly becomes brighter and brighter over time. Put another way, we learn and acquire words by degrees. —Vocabulary Their Way, p.237

So, yes we need to know definitions, but that’s just the starting point for knowing a word. In an article from 2000, Vocabulary Processes, authors William Nagy and Judith Scott synthesized vocabulary research to identify five aspects of word knowledge. They are:

- Incrementality— Knowing a word is a matter of degrees. Every time we encounter a word, our knowledge of that word becomes a bit more precise. Take, for example, a relatively common word like free. How has your understanding of that word deepened over time?

- Multidimensionality— Knowing a word extends beyond recalling the definition. In the book, Greek & Latin Roots: Keys to Building Vocabulary (p. 13) the authors give these examples of multidimensionality: Allege and believe share a core meaning of “certainty” or “conviction.” Yet, they are conceptually distinct…Collocation, or the frequent placing together of words, is also a part of word knowledge. We can talk about a storm front, but not a storm back. Similarly, we can have a storm door and a storm window, but not a storm ceiling or a storm floor.

- Polysemy–Knowing a word means understanding its various meanings. The more common the word, the more meanings it has. For example, the word draw is a word every preschooler knows, but they would be confused by “draw water from the well” or “draw your chair over to the window” or “draw a conclusion about what happened.” The meaning of a word relies, ultimately, on the context in which it is used. Sometimes the context is explicit, but it often must be inferred.

- Interrelatedness–Knowing a word means knowing how it’s linked to other words. This often involves knowing its attributes and how it is related to other words or concepts. Think of all the things you know about even a simple concept like dog. You maybe thought of words like pet or furry. Or maybe the name of your own pet dog. And what about mammal, companion, loyal, breed? A word can only be defined by using other words, so by their very nature words are connected.

- Heterogeneity–Knowing a word at a deep level varies substantially depending on the word. The depth of understanding required to know the word the is vastly different than the understanding required by afterhyperpolarization.

Knowing a word is a complex business indeed! Since we’re not allowed to go poking around in children’s brains, to really measure a student’s vocabulary depth we have to think about the behaviors that can show us a student knows a word. As Greg Conderman says, “Truly knowing a word encompasses the entire spectrum of language: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.” So looking at a student’s speaking and writing are good places to start. We can surmise a lot about vocabulary depth when we focus on a student’s expressive vocabulary–that is, the words a student knows well enough to use when communicating. By counting the number of Tier 2 and 3 words (or as some researchers call them, “rare” words) a student uses, we have a clear picture of the richness a student’s vocabulary. The most efficient way to do this is to look at a child’s writing.

Collect a writing sample from each student. Count the number of rare words the writer uses. Then count the total number of words in the piece. Obviously, the higher the frequency of rare words, the deeper a student’s expressive vocabulary. In our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack, we have a form to help you organize this data. Because vocabulary growth happens over time, the form provides space for on-going assessment.

This process is tedious, however, especially if your writers compose long stories. Doing this 2-3 times a year would be enough to give you a picture of that child’s vocabulary development. For the short term, there are many other assessments to indicate a student’s word knowledge.

One option is to do the Rare Words assessment, but have the students participate in the scoring. For this to be effective, students have to be familiar with rare words. If you’ve been doing vocabulary study in your classroom, they will have some understanding of what you mean when you talk about rare words. With the students, I use the term “WOW!” words. These are words that are perhaps longer, more challenging. They may take a common idea–for example, happiness–and express it in a more complex way like merriment. These are words that if you heard someone use them you would say, “Wow!” For this activity we won’t make a distinction between Tier 2 and Tier 3 words because words from both groups are indicative of higher levels of comprehension and expression.

To complete this assessment, make sure each student has a recently finished written piece. Distribute a WOW! Words self-assessment to the students and ask them to look through their writing for examples of WOW! words. They should list any words they find. At the bottom is a space for students to compare the number of WOW! words to the story’s total words. You may consider skipping this step if your students are young and this task is too tedious or frustrating for them. There is also room for students to reflect on the richness of their vocabulary and determine what they can do better as a writer.

By involving students in this assessment, you lose some accuracy. They may not recognize a word you would consider rare or, more likely, they will include words you don’t think qualify. It’s not uncommon to see a word like tent included on a child’s list because camping with his family is important to him. In this activity, complete accuracy isn’t as important as awakening your learners to the realization that they should be using expansive vocabulary in their writing. By fostering a classroom culture where words are cherished, you create eagerness among your students to learn and use richer words.

Another way to encourage word awareness is to give students a Vocabulary Self-Rating Chart. On this task, you provide the words. The words you choose will depend on your why for assessment. Are you using this as a pre-test for your next science unit? Is it a follow-up to see which words have been retained from last November’s Jargon Journals? Are you giving the students words you’ve never taught them to get a general feel of their vocabulary levels? When you’ve identified your purpose, write the words on the left column of the page. There’s a form that includes space for 5 words or one that has space for 10 words. Each student needs a form. Students read the words and mark the column that matches their familiarity with each word. Only one column should be marked per word. The columns are labeled:

- I’ve never seen this word.

- I’ve seen it, but don’t know it.

- I know something about this word. I think it means______.

- I know this word well. I can use it in a sentence:

To score the assessment, the number of each column determines the points to be awarded. If you distribute the 5-word assessment and the student correctly fills in a sentence and definition for two words (column 4), correctly writes a definition for one word (column 3), and checks column 2 twice (I’ve seen it, but don’t know it), the total score is 4+4+3+2+2=15.

Even if students don’t know anything about the word, they’re still awarded 1 point. It’s important to honor where they are right now in their learning. If students recognize that there is value in admitting that you do not yet know something, they’re more receptive to filling that gap in knowledge.

If a student attempts a definition or sentence, but is incorrect, they receive 2 points for that word. The student has seen the word at some point, but doesn’t know what it means (even if she thinks she does!).

You’ll notice on this ranking that the highest level of understanding is demonstrated by using the word in a sentence. That’s because it takes 10-15 exposures to a word in meaningful context before it becomes an available part of our expressive vocabularies. And if a student struggles in school, it may take up to 40 experiences with a word before it is mastered. Therefore, be wary of vocabulary tasks that expect students to accurately use a new word in the context of a sentence at the introductory stage of learning. Think about how comfortable you are with new words. If you learn that the word procrustean means marked by arbitrary often ruthless disregard of individual differences or special circumstances, are you now comfortable using that word in context in front of someone else? What about immediately having to use procrustean correctly for a grade? If you’re assessing to see if students have mastered a word, writing sentences is a good exercise. If you’re measuring anything less than mastery, asking students to use new vocabulary words in context will yield a lot of poorly written sentences and potentially stifle any excitement among students about expanding their vocabularies.

Another form in our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack for student self-assessment is the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale. It’s similar to the Vocabulary Self-Rating Chart, but provides additional space for students to decide if they think they know a word or absolutely know a word. The form is assessed by adding the number of each question marked. If on one word a student marks the third choice and adds a correct definition, he gets 3 points. If he marks the 5th choice and adds a definition and sentence, he gets 5 points. If he marks any choice, but has an incorrect word meaning, he gets 2 points.

The words you add to the page will be determined by your purpose in giving the assessment. If it’s a social studies post-test, you’ll include the words from the unit. If you’re curious about general vocabulary depth, you may include any Tier 2 words that the class hasn’t studied.

If you’re wanting students to make connections among words, don’t underestimate the power of semantic mapping (or word webbing, as I call it in my classroom). This is an oldie, but a goodie. In semantic mapping, the teacher chooses an important vocabulary word with which she wants her students to make connections. Maybe the word is orbit based on a science study of the moon. Maybe the word is eagerly because it will be used in a class read-aloud. Maybe it’s not even an entire word, but a root like tract that the students need to practice. Whichever key word is chosen, it is added to the center of the map. A few additional important words may be added by the teacher. Lines are added to connect important words to the key word. This is all that can be done ahead of time, the rest of the information comes from the students.

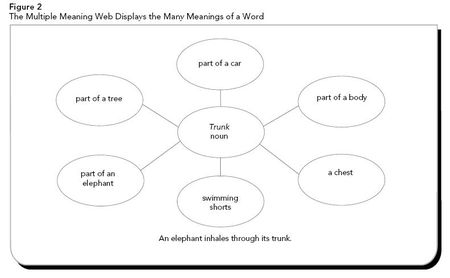

In these 2 examples from Reading Rockets you can see different uses of a word map. In the first one, the purpose is to get students to examine the multiple meanings of the word trunk.

The key word for this map is, of course trunk. The teacher has added some supporting ideas and connected them with lines to the center of the chart. The rest of the information will be added by the students. As part of a class discussion, she’ll have them contribute their background knowledge about the different trunks and she will add it as offshoots from the appropriate circle.

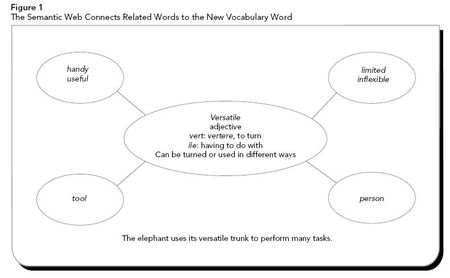

In this second word web, the idea is to introduce students to the word versatile.

She has completed the framework of the web and will look for student ideas to contribute to further information for each word.

By using a chart to visually show students how their background knowledge connects to new learning, you offer a powerful too for helping students retain this fresh information. As Kellie Buis says in her book Making Words Stick (p. 20):

Semantic mapping can make vocabulary meaningful and memorable in ways that reading text in a linear left-to-right fashion alone cannot. It can make vocabulary knowledge public. It can make vocabulary concrete in ways spoken language alone cannot. The techniques of webbing, clustering, or mapping helps students generate nonlinear associations and ideas about words. It assists them in being interested in the words. It allows them to feel connected to the important words, and makes them part of the vocabulary learning process.

Word webbing is something that, given enough teacher supported practice, even 2nd graders can learn to do independently. I’ve done it as a whole group with my preschoolers, so I’m sure it’s accessible to kindergarten and 1st grade classes as a shared writing activity. Regardless of the grade, as with any strategy you will want to start this by modeling. Depending on the skill level of your students, it may be appropriate to have students use their vocabulary journals to make individual copies of what you record on the chart. You can ask them to draw the map on a page of their notebook or distribute a word web from our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack.

As a follow-up, you may want the students to do some extensions with the web. Having them reexamine the words they’ve generated will help them retain the information and provide you with sense of how well they internalized the vocabulary. You may ask the students to:

- Pick one of the words and write two synonyms.

- Pick one of the words and write two antonyms.

- Pick one of the words and write your own definition.

- Pick one of the words and tell a personal connection to that word.

- Pick one of the words and draw a picture to illustrate the word. Explain how your picture matches the word’s meaning.

If you’re interested in knowing how well the words have been mastered, you may ask students to pick one of the words and use it in a sentence.

How you score the activity will depend on what you ask the students to do. If they have created their own word webs, you can collect those and assess them for depth of understanding.

Another assessment tool is vocabulary sorts. I’ll let Vocabulary Their Way (p.242) sum it up more eloquently than I can:

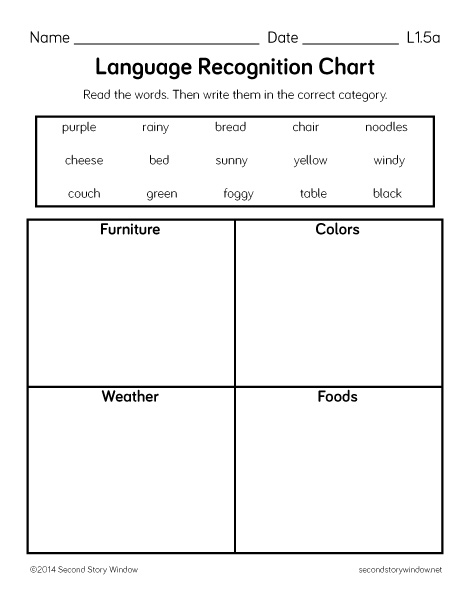

Concept sorting is a dynamic way to assess students’ conceptual knowledge as they organize, categorize, and arrange related concepts before, during, or after a lesson or unit of study. Asking students to explain their thinking, either in discussion or writing, provides valuable assessment information regarding the depth of their vocabulary knowledge and their ability to make connections across words in the sort.

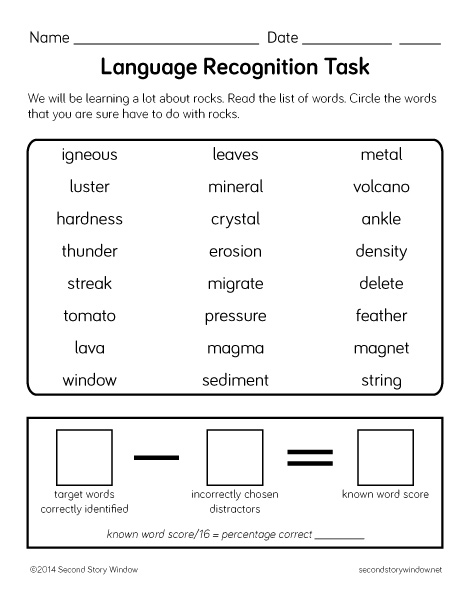

There are different formats and different purposes for a vocabulary sort. As a conclusion to a social studies unit on community, you may give students a set of word cards and ask them to sort the words into either the Goods category or Services. Prior to a science unit, you may give students a page and ask students to circle all of the words that relate to your upcoming topic. This Language Recognition Task can serve as a pretest to see what information students already have or a post test to see what has been retained.

A caution with this sort of assessment is that students may make connections you didn’t anticipate. For example, if a student knows that glass is made from sand and sand is made of tiny rocks, he may circle window as a rock related word because windows are made of glass.

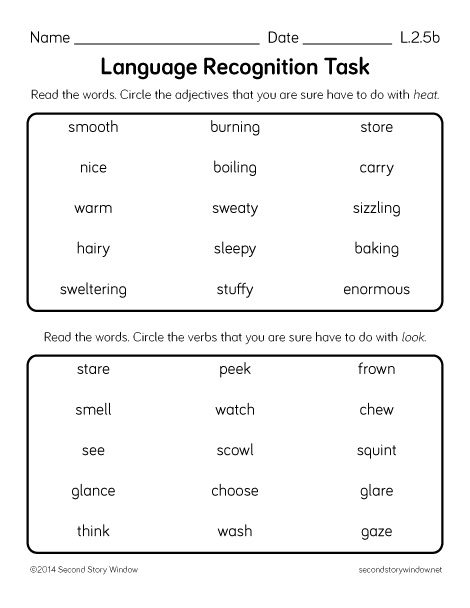

A Language Recognition Task can be used for vocabulary outside of content areas. In the CCSS, 2nd graders are supposed to distinguish shades of meaning among closely related verbs and adjectives. With this assessment, the teacher can see how many words for look or hot or throw a student knows.

Don’t let all this talk of assessment and expressive and context and depth overwhelm you. The airy nature of vocabulary makes it difficult to manage, but, just like the air, once you realize it exists you pay more attention to it. When you raise student awareness of the power of words they become excited about learning more. Let the assessments help you do that. You’re not expected to assign them all, in fact none of them may even be useful for your class, but anytime you have students thinking about words they already know and attach them to words they should know, you’re going a long way to increase their powers of expression and comprehension.

Check out our other posts about vocabulary:

Why Vocabulary Matters

Acquiring Vocabulary with an Interactive Vocabulary Notebook

Tools for Vocabulary Instruction