“I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

“I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, that one day right down in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I will go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.

With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning, “My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrims’ pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.” – Martin Luther King

This Martin Luther King Day, we’re honored to share this recording of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s «I Have A Dream» from August 28, 1963 by A Better Chance of Andover Scholar Kiarra D. Lucas. Kiarra is a spoken word poet and currently a Scholar at A Better Chance of Andover. You can learn more about A Better Chance of Andover on their website and on their Instagram account, where you can also meet this year’s ABC Scholars.

Thank you, Kiarra, for allowing us to share your work.

Read a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr., on Biography.com.

Visit the Cornell University Library website for a list of resources to learn more about Martin Luther King, Jr. The guide is divided into categories: books written by King, his assassination, biography, Civil Rights Movement, films and speeches, noteworthy websites, and other resources.

Stanford University’s Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute’s website provides access to thousands of documents, photographs, and publications.

Thank you for reading!

~Elaine

Leave a comment

Share

«У меня есть мечта» («Я мечтаю», «I have a dream») — название самой известной речи Мартина Лютера Кинга. Мартин Лютер Кинг произнес эту речь около полувека назад 28 августа 1963 года со ступеней Мемориала Линкольна во время Марша на Вашингтон за рабочие места и свободу. В этом выступлении Кинг на весь мир провозгласил свое видение будущего Соединенных Штатов Америки, где белое и черное население могли бы сосуществовать как равноправные граждане своей страны.

Смотреть видео «I have a dream»

на английском языке

Смотреть видео «У меня есть мечта»

на русском языке

Речь Мартина Лютера Кинга «У меня есть мечта» и по настоящее время является общепризнанным шедевром ораторского мастерства. Наверное, многие знаменитые политики не раз пересматривали ее, шлифуя свои риторические навыки.

Ораторские приемы

Давайте и мы рассмотрим эту знаменитую речь с точки зрения использования Мартином Лютером Кингом специальных ораторских приемов, оформляющих тезисы его речи, превращающих его выступление в мощнейшее агитационное оружие.

Стиль и формат. Мартин Лютер Кинг, являясь баптистским священником, произнес настоящую речь-проповедь. Конечно, это не была проповедь в чистом виде, но выступление прошло именно в религиозном формате, на тот момент столь близком для 300 тысяч американцев, стоявших у подножья монумента Линкольну. Стилистика выступления в первую очередь продиктована отказом автора от стандартных политических лозунгов и обращением к такому личному рассказу о своей мечте.

Подготовка к выступлению. Стоит отметить, что речь эта не была спонтанной, к своему выступлению «У меня есть мечта» Мартин Лютер Кинг готовился осознанно и очень серьезно. По ходу выступления автор изредка пользовался своими записями, которые помогли ему произнести великолепную эмоциональную речь, без оговорок и запинок. Его голос звучал настолько естественно и уверенно, что эта уверенность мгновенно передалась всем присутствующим. Без тщательной подготовки, произнести такую заразительную речь было бы просто невозможно.

Метафоры. «Мы сможем вырубить камень надежды из горы отчаяния», «мы сможем превратить нестройные голоса нашего народа в прекрасную симфонию братства». Метафоры сделали тезисы Кинга яснее, ярче, и смогли поистине придать его мыслям эмоциональные оттенки настоящей мечты, донести их до самых глубин сознания и сердец слушателей.

Цитаты. Речь Кинга изобилует аллюзиями на Ветхий и Новый Завет, Декларацию независимости США, Манифест об освобождении рабов и Конституцию Соединенных Штатов. Автор намеренно использует цитаты из тех источников, которые признаны, как среди его сторонников, так и среди противников, таким образом, адресуя свое выступление и тем, и другим, увеличивая свои шансы воздействия на слушателей.

Темп и паузы. Важнейшую роль в этой речи играет темп произнесения текста и логические паузы. Они выделяют каждую фразу речи, каждую законченную мысль. Основной темп речи плавный, с постепенной тенденцией к ускорению, усилению эмоциональной составляющей, которая подогревает толпу слушателей, срывая громкие овации и крики одобрения.

Аудитория. Вы, скорее всего, заметили на фоне выступления Кинга кивающие лица, которые отражают их доверие к оратору, настоящую веру в его идеи. Эти лица воздействуют на наше восприятие речи «I have a dream» подсознательно, используя человеческую склонность к конформизму, нежелание идти наперекор мнению большинства. Этот ораторский прием используется многими политиками, он и по сей день не потерял своей актуальности.

Цикличность речи. Речь Кинга нельзя назвать типичным последовательным изложением одной мысли. Обратите внимание на тот факт, что он не раз возвращается к определенным тезисам своего выступления. Общими местами являются неоднократные обращения оратора к своим товарищам из Колорадо, Миссисипи, Алабамы, которые перекликаются с идеями уже упомянутыми автором ранее, возвращают слушателей к этим мыслям, заставляют еще раз задуматься о главных для Кинга вещах.

Общие тезисы

Кроме того, Мартин Лютер Кинг адресует свое выступление не только аудитории, собравшейся у Мемориала Линкольна, но и руководству страны, людям, принимающим важнейшие решения. Этим фактом продиктована особая логическая структура тезисов в речи оратора. Можно сказать, что некоторые высказывания и заявления Мартина Лютера Кинга в речи «I have a dream» были похожи на шантаж властей США: «Мы не успокоимся до тех пор, пока…», — говорит он, обращаясь и к своим товарищам, чтобы обозначить их чувство идентичности с протестным движением, с одной стороны, и обращаясь к своим противникам, чтобы вынудить их вступить в переговоры во избежание беспорядков, с другой стороны.

Цитаты речи

“I have a dream” – «У меня есть мечта»

“I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow. I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.” – “И хотя мы сталкиваемся с трудностями сегодня и будем сталкиваться с ними завтра, у меня всё же есть мечта. Эта мечта глубоко укоренена в американской мечте.”

“I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right down in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” – “Я мечтаю сегодня, что однажды в Алабаме с её злобными расистами и губернатором, с губ которого слетают слова о вмешательстве и аннулировании, в один прекрасный день, именно в Алабаме, маленькие чёрные мальчики и девочки возьмутся как сёстры и братья за руки с маленькими белыми мальчиками и девочками.”

Отзывы и комментарии

Оставить комментарий вы можете ниже.

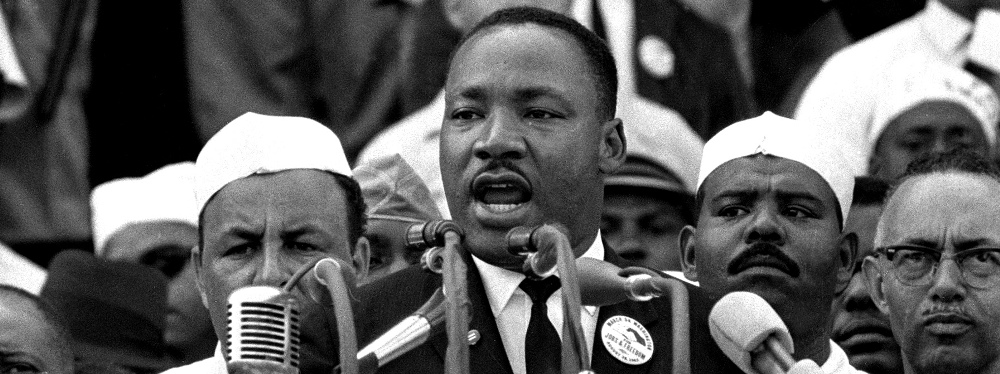

«I Have a Dream» is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister[2] Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. Delivered to over 250,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech was one of the most famous moments of the civil rights movement and among the most iconic speeches in American history.[3][4]

| External audio |

|---|

Beginning with a reference to the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared millions of slaves free in 1863,[5] King said «one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free».[6] Toward the end of the speech, King departed from his prepared text for a partly improvised peroration on the theme «I have a dream», prompted by Mahalia Jackson’s cry: «Tell them about the dream, Martin!»[7] In this part of the speech, which most excited the listeners and has now become its most famous, King described his dreams of freedom and equality arising from a land of slavery and hatred.[8]

Jon Meacham writes that, «With a single phrase, King joined Jefferson and Lincoln in the ranks of men who’ve shaped modern America».[9] The speech was ranked the top American speech of the 20th century in a 1999 poll of scholars of public address.[10] The speech has also been described as having «a strong claim to be the greatest in the English language of all time».[11]

Background

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was partly intended to demonstrate mass support for the civil rights legislation proposed by President John F. Kennedy in June. Martin Luther King and other leaders, therefore, agreed to keep their speeches calm, also, to avoid provoking the civil disobedience which had become the hallmark of the Civil Rights Movement. King originally designed his speech as a homage to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, timed to correspond with the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation.[8]

Speech title and the writing process

King had been preaching about dreams since 1960, when he gave a speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) called «The Negro and the American Dream». This speech discusses the gap between the American dream and reality, saying that overt white supremacists have violated the dream, and that «our federal government has also scarred the dream through its apathy and hypocrisy, its betrayal of the cause of justice». King suggests that «It may well be that the Negro is God’s instrument to save the soul of America.»[12][13] In 1961, he spoke of the Civil Rights Movement and student activists’ «dream» of equality—»the American Dream … a dream as yet unfulfilled»—in several national speeches and statements and took «the dream» as the centerpiece for these speeches.[14]

Leaders of the March on Washington photographed in front of the statue of Abraham Lincoln on August 28, 1963: (sitting L-R) Whitney Young, Cleveland Robinson, A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., and Roy Wilkins; (standing L-R) Mathew Ahmann, Joachim Prinz, John Lewis, Eugene Carson Blake, Floyd McKissick, and Walter Reuther

On November 27, 1962, King gave a speech at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. That speech was longer than the version which he would eventually deliver from the Lincoln Memorial. And while parts of the text had been moved around, large portions were identical, including the «I have a dream» refrain.[15][16] After being rediscovered in 2015,[17] the restored and digitized recording of the 1962 speech was presented to the public by the English department of North Carolina State University.[15]

King had also delivered a speech with the «I have a dream» refrain in Detroit, in June 1963, before 25,000 people in Detroit’s Cobo Hall immediately after the 125,000-strong Great Walk to Freedom on June 23, 1963.[18][19][20] Reuther had given King an office at Solidarity House, the United Auto Workers headquarters in Detroit, where King worked on his «I Have a Dream» speech in anticipation of the March on Washington.[21] Mahalia Jackson, who sang «How I Got Over»,[22] just before the speech in Washington, knew about King’s Detroit speech.[23] After the Washington, D.C. March, a recording of King’s Cobo Hall speech was released by Detroit’s Gordy Records as an LP entitled The Great March To Freedom.[24]

The March on Washington Speech, known as «I Have a Dream Speech», has been shown to have had several versions, written at several different times.[25] It has no single version draft, but is an amalgamation of several drafts, and was originally called «Normalcy, Never Again». Little of this, and another «Normalcy Speech», ended up in the final draft. A draft of «Normalcy, Never Again» is housed in the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection of the Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center and Morehouse College.[26] The focus on «I have a dream» comes through the speech’s delivery. Toward the end of its delivery, noted African-American gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouted to King from the crowd, «Tell them about the dream, Martin.»[27] King departed from his prepared remarks and started «preaching» improvisationally, punctuating his points with «I have a dream.»

The speech was drafted with the assistance of Stanley Levison and Clarence Benjamin Jones[28] in Riverdale, New York City. Jones has said that «the logistical preparations for the march were so burdensome that the speech was not a priority for us» and that, «on the evening of Tuesday, Aug. 27, [12 hours before the march] Martin still didn’t know what he was going to say».[29]

Speech

Widely hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, King’s speech invokes pivotal documents in American history, including the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the United States Constitution. Early in his speech, King alludes to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address by saying «Five score years ago …» In reference to the abolition of slavery articulated in the Emancipation Proclamation, King says: «It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.» Anaphora (i.e., the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of sentences) is employed throughout the speech. Early in his speech, King urges his audience to seize the moment; «Now is the time» is repeated three times in the sixth paragraph. The most widely cited example of anaphora is found in the often quoted phrase «I have a dream», which is repeated eight times as King paints a picture of an integrated and unified America for his audience. Other occasions include «One hundred years later», «We can never be satisfied», «With this faith», «Let freedom ring», and «free at last». King was the sixteenth out of eighteen people to speak that day, according to the official program.[30]

I still have a dream, a dream deeply rooted in the American dream – one day this nation will rise up and live up to its creed, «We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal.» I have a dream …

—Martin Luther King Jr. (1963)[31]

Among the most quoted lines of the speech are «I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!»[32]

According to US Representative John Lewis, who also spoke that day as the president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, «Dr. King had the power, the ability, and the capacity to transform those steps on the Lincoln Memorial into a monumental area that will forever be recognized. By speaking the way he did, he educated, he inspired, he informed not just the people there, but people throughout America and unborn generations.»[33]

The ideas in the speech reflect King’s social experiences of ethnocentric abuse, mistreatment, and exploitation of black people.[34] The speech draws upon appeals to America’s myths as a nation founded to provide freedom and justice to all people, and then reinforces and transcends those secular mythologies by placing them within a spiritual context by arguing that racial justice is also in accord with God’s will. Thus, the rhetoric of the speech provides redemption to America for its racial sins.[35] King describes the promises made by America as a «promissory note» on which America has defaulted. He says that «America has given the Negro people a bad check», but that «we’ve come to cash this check» by marching in Washington, D.C.

Similarities and allusions

King’s speech used words and ideas from his own speeches and other texts. For years, he had spoken about dreams, quoted from Samuel Francis Smith’s popular patriotic hymn «America (My Country, ‘Tis of Thee)», and referred extensively to the Bible. The idea of constitutional rights as an «unfulfilled promise» was suggested by Clarence Jones.[12]

The final passage from King’s speech closely resembles Archibald Carey Jr.’s address to the 1952 Republican National Convention: both speeches end with a recitation of the first verse of «America», and the speeches share the name of one of several mountains from which both exhort «let freedom ring».[12][36]

King is said to have used portions of SNCC activist Prathia Hall’s speech at the site of Mount Olive Baptist, a burned-down African-American church in Terrell County, Georgia, in September 1962, in which she used the repeated phrase «I have a dream».[37] The church burned down after it was used for voter registration meetings.[38]

The speech in the cadences of a sermon is infused with allusions to biblical verses, including Isaiah 40:4–5 («I have a dream that every valley shall be exalted …»[39]) and Amos 5:24 («But let justice roll down like water …»[40]).[2] The end of the speech alludes to Galatians 3:28: «There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus».[41] He also alludes to the opening lines of Shakespeare’s Richard III («Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer …») when he remarks that «this sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn …»[42]

Rhetoric

King at the Civil Rights March in Washington, D.C.

The «I Have a Dream» speech can be dissected by using three rhetorical lenses: voice merging, prophetic voice, and dynamic spectacle.[43] Voice merging is the combining of one’s own voice with religious predecessors. Prophetic voice is using rhetoric to speak for a population. A dynamic spectacle has origins from the Aristotelian definition as «a weak hybrid form of drama, a theatrical concoction that relied upon external factors (shock, sensation, and passionate release) such as televised rituals of conflict and social control.»[44]

The rhetoric of King’s speech can be compared to the rhetoric of Old Testament prophets. During his speech, King speaks with urgency and crisis, giving him a prophetic voice. The prophetic voice must «restore a sense of duty and virtue amidst the decay of venality.»[45] An evident example is when King declares that «now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.»

Voice merging is a technique often used by African-American preachers. It combines the voices of previous preachers, excerpts from scriptures, and the speaker’s own thoughts to create a unique voice. King uses voice merging in his peroration when he references the secular hymn «America».[citation needed]

A dynamic spectacle is dependent on the situation in which it is used. King’s speech can be classified as a dynamic spectacle, given «the context of drama and tension in which it was situated» (during the Civil Rights Movement and the March on Washington).[46]

Why King’s speech was powerful is debated. Executive speechwriter Anthony Trendl writes, «The right man delivered the right words to the right people in the right place at the right time.»[47]

Responses

You could feel «the passion of the people flowing up to him,» James Baldwin, a skeptic of that day’s March on Washington, later wrote, and in that moment, «it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real.»

M. Kakutani, The New York Times[2]

The speech was lauded in the days after the event and was widely considered the high point of the March by contemporary observers.[48] James Reston, writing for The New York Times, said that «Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile.»[12] Reston also noted that the event «was better covered by television and the press than any event here since President Kennedy’s inauguration», and opined that «it will be a long time before [Washington] forgets the melodious and melancholy voice of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. crying out his dreams to the multitude.»[49]

An article in The Boston Globe by Mary McGrory reported that King’s speech «caught the mood» and «moved the crowd» of the day «as no other» speaker in the event.[50] Marquis Childs of The Washington Post wrote that King’s speech «rose above mere oratory».[51] An article in the Los Angeles Times commented that the «matchless eloquence» displayed by King—»a supreme orator» of «a type so rare as almost to be forgotten in our age»—put to shame the advocates of segregation by inspiring the «conscience of America» with the justice of the civil-rights cause.[52]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which viewed King and his allies for racial justice as subversive, also noticed the speech. This provoked the organization to expand their COINTELPRO operation against the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and to target King specifically as a major enemy of the United States.[53] Two days after King delivered «I Have a Dream», Agent William C. Sullivan, the head of COINTELPRO, wrote a memo about King’s growing influence:

Personally, I believe in the light of King’s powerful demagogic speech yesterday he stands head and shoulders above all other Negro leaders put together when it comes to influencing great masses of Negroes. We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.[54]

The speech was a success for the Kennedy administration and for the liberal civil rights coalition that had planned it. It was considered a «triumph of managed protest», and not one arrest relating to the demonstration occurred. Kennedy had watched King’s speech on television and been very impressed. Afterward, March leaders accepted an invitation to the White House to meet with President Kennedy. Kennedy felt the March bolstered the chances for his civil rights bill.[55]

Some Black leaders later criticized the speech (along with the rest of the march) as too compromising. Malcolm X later wrote in his autobiography: «Who ever heard of angry revolutionaries swinging their bare feet together with their oppressor in lily pad pools, with gospels and guitars and ‘I have a dream’ speeches?»[8]

Legacy

The location on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial from which King delivered the speech is commemorated with this inscription

The March on Washington put pressure on the Kennedy administration to advance its civil rights legislation in Congress.[56] The diaries of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., published posthumously in 2007, suggest that President Kennedy was concerned that if the march failed to attract large numbers of demonstrators, it might undermine his civil rights efforts.[citation needed]

In the wake of the speech and march, King was named Man of the Year by TIME magazine for 1963, and in 1964 he was the youngest man ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[57] The full speech did not appear in writing until August 1983, some 15 years after King’s death, when a transcript was published in The Washington Post.[6]

In 1990, the Australian alternative comedy rock band Doug Anthony All Stars released an album called Icon. One song from Icon, «Shang-a-lang», sampled the end of the speech.[citation needed]

In 1992, the band Moodswings, incorporated excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream» speech in their song «Spiritual High, Part III» on the album Moodfood.[58][59]

In 2002, the Library of Congress honored the speech by adding it to the United States National Recording Registry.[60] In 2003, the National Park Service dedicated an inscribed marble pedestal to commemorate the location of King’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial.[61]

Near the Potomac Basin in Washington, D.C., the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial was dedicated in 2011. The centerpiece for the memorial is based on a line from King’s «I Have A Dream» speech: «Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope.»[62] A 30 feet (9.1 m)-high relief sculpture of King named the Stone of Hope stands past two other large pieces of granite that symbolize the «mountain of despair» split in half.[62]

On August 26, 2013, UK’s BBC Radio 4 broadcast «God’s Trombone», in which Gary Younge looked behind the scenes of the speech and explored «what made it both timely and timeless».[63]

On August 28, 2013, thousands gathered on the mall in Washington, D.C. where King made his historic speech to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the occasion. In attendance were former US Presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter, and incumbent President Barack Obama, who addressed the crowd and spoke on the significance of the event. Many of King’s family were in attendance.[64]

On October 11, 2015, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution published an exclusive report about Stone Mountain officials considering the installation of a new «Freedom Bell» honoring King and citing the speech’s reference to the mountain «Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.»[65] Design details and a timeline for its installation remain to be determined. The article mentioned the inspiration for the proposed monument came from a bell-ringing ceremony held in 2013 in celebration of the 50th anniversary of King’s speech.[citation needed]

On April 20, 2016, Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew announced that the US $5 bill, which has featured the Lincoln Memorial on its back, would undergo a redesign prior to 2020. Lew said that a portrait of Lincoln would remain on the front of the bill, but the back would be redesigned to depict various historical events that have occurred at the memorial, including an image from King’s speech.[66]

Ava DuVernay was commissioned by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture to create a film that debuted at the museum’s opening on September 24, 2016. This film, August 28: A Day in the Life of a People (2016), tells of six significant events in African-American history that happened on the same date, August 28. Events depicted include (among others) the speech.[67]

In October 2016, Science Friday in a segment on its crowd sourced update to the Voyager Golden Record included the speech.[68]

In 2017, the statue of Martin Luther King Jr. on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol was unveiled on the 54th anniversary of the speech.[69]

Time partnered with Epic Games to create an interactive exhibit dedicated to the speech within Epic’s game Fortnite Creative on the 58th anniversary of the speech.[70]

Copyright dispute

Because King’s speech was broadcast to a large radio and television audience, there was controversy about its copyright status. If the performance of the speech constituted «general publication», it would have entered the public domain due to King’s failure to register the speech with the Register of Copyrights. But if the performance constituted only «limited publication», King retained common law copyright. This led to a lawsuit, Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. v. CBS, Inc., which established that the King estate did hold copyright over the speech and had standing to sue; the parties then settled. Unlicensed use of the speech or a part of it can still be lawful in some circumstances, especially in jurisdictions under doctrines such as fair use or fair dealing. Under the applicable copyright laws, the speech will remain under copyright in the United States until 70 years after King’s death, through 2038.[71][72][73][74]

Original copy of the speech

As King waved goodbye to the audience, George Raveling, volunteering as a security guard at the event, asked King if he could have the original typewritten manuscript of the speech.[75] Raveling, a star college basketball player for the Villanova Wildcats, was on the podium with King at that moment.[76] King gave it to him. Raveling kept custody of the original copy, for which he has been offered $3 million, but he has said he does not intend to sell it.[77][78] In 2021, he gave it to Villanova University. It is intended to be used in a «long-term ‘on loan’ arrangement.»[79]

Chart performance

In the wake of King’s death, the speech was issued as a single under Gordy Records and managed to crack onto the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number 88.[80]

References

- ^ «Special Collections, March on Washington, Part 17». Open Vault. at WGBH. August 28, 1963. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Kakutani, Michiko (August 28, 2013). «The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 177. OCLC 473993560.

- ^ Tikkanen, Amy (August 29, 2017). «I Have a Dream». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Echols, James (2004), I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Future of Multicultural America.

- ^ a b Alexandra Alvarez, «Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’: The Speech Event as Metaphor», Journal of Black Studies 18(3); doi:10.1177/002193478801800306.

- ^ See Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954–1963.

- ^ a b c X, Malcolm; Haley, Alex (1973). Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 281.

- ^ Meacham, Jon (August 26, 2013). «One Man». Time. p. 26.

- ^ Lucas, Stephen; Medhurst, Martin (December 15, 1999). «I Have a Dream Speech Leads Top 100 Speeches of the Century». University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ O’Grady, Sean (April 3, 2018). «Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech is the greatest oration of all time». The Independent. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d «I Have a Dream». The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. May 8, 2017. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Martin Luther King Jr., «The Negro and the American Dream Archived December 18, 2014, at the Stanford Web Archive», speech delivered to the NAACP in Charlotte, NC, September 25, 1960.

- ^ Cullen, Jim (2003). The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0195158210.

- ^ a b Stringer, Sam; Brumfield, Ben (August 12, 2015). «New recording: King’s first ‘I have a dream’ speech found at high school». CNN. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Crook, Samantha; Bryant, Christian. «How Langston Hughes Led To A ‘Dream’ MLK Discovery». WKBW-TV. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Waggoner, Martha (August 11, 2015). «Recording of MLK’s 1st ‘I Have a Dream’ speech found». DetroitNews.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Boyle, Kevin (May 1, 2007), «Detroit’s Walk To Freedom», Michigan History Magazine, archived from the original on May 18, 2012, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ Garrett, Bob, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Detroit Freedom Walk, Michigan Department of Natural Resources – Michigan Library and Historical – Center Michigan Historical Center, archived from the original on March 1, 2014, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ O’Brien, Soledad (August 22, 2003). «Interview With Martin Luther King III». CNN. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ Kaufman, Dan (September 26, 2019). «On the Picket Lines of the General Motors Strike». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Kot, Greg (October 21, 2014). «How Mahalia Jackson defined the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech». BBC. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Norris, Michele (August 28, 2013). «For King’s Adviser, Fulfilling The Dream ‘Cannot Wait’«. NPR. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Ward, Brian (1998), Recording the Dream, vol. 48, History Today, archived from the original on February 15, 2012, retrieved February 15, 2012

- ^ Hansen 2003, p. 70. The original name of the speech was «Cashing a Cancelled Check», but the aspired ad lib of the dream from preacher’s anointing brought forth a new entitlement, «I Have A Dream».

- ^ Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection, 2009 «Notable Items Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine» Retrieved December 4, 2013

- ^ Hansen 2003, p. 58.

- ^ «Jones, Clarence Benjamin (1931– )». Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle (Stanford University). Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Clarence B. (January 16, 2011). «On Martin Luther King Day, remembering the first draft of ‘I Have a Dream’«. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ «Document for August 28th: Official Program for the March on Washington». Archives.gov. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Willard. (August 29, 1963). 200,000 Roar Plea for Negro Opportunity in Rights March on Washington. Chicago Tribune, p. 5.

- ^ Excel HSC Standard English, p. 108, Lloyd Cameron, Barry Spurr – 2009

- ^ «A «Dream» Remembered». NewsHour. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on May 4, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ Exploring Religion and Ethics: Religion and Ethics for Senior Secondary Students, p. 192, Trevor Jordan – 2012.

- ^ See David A. Bobbitt, The Rhetoric of Redemption: Kenneth Burke’s Redemption Drama and Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream» Speech, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

- ^ John, Derek (August 28, 2013). «Long lost civil rights speech helped inspire King’s dream». WBEZ. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Holsaert, Faith et al. Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC. University of Illinois Press, 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Civil Rights Digital Library Archived February 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine: Film (2:30).

- ^ «Isaiah 40:4–5». King James Version of the Bible. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ «Amos 5:24». King James Version of the Bible. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Neutel, Karin (May 19, 2020). «Galatians 3:28—Neither Jew nor Greek, Slave nor Free, Male and Female». Biblical Archaeology Society. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ Alvarez, Alexandra (March 1988), «Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’: The Speech Event as Metaphor», Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 18, No. 3 (pp. 337–357), p. 242.

- ^ Vail, Mark (2006). «The ‘Integrative’ Rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr.’S ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech». Rhetoric and Public Affairs. 9 (1): 52. doi:10.1353/rap.2006.0032. JSTOR 41940035. S2CID 143912415.

- ^ Farrell, Thomas B. (1989). «Media Rhetoric as Social Drama: The Winter Olympics of 1984». Critical Studies in Mass Communication. 6 (2): 159–160. doi:10.1080/15295038909366742.

- ^ Darsey, James (1997). The Prophetic Tradition and Radical Rhetoric in America. New York: New York University Press. pp. 10, 19, 47. ISBN 9780814718766.

- ^ Vail 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Trendl, Anthony. «I Have a Dream Analysis». Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ «The News of the Week in Review: March on Washington—Symbol of intensified drive for Negro rights,» The New York Times (September 1, 1963). The high point and climax of the day, it was generally agreed, was the eloquent and moving speech late in the afternoon by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., ….

- ^ James Reston, «‘I Have a Dream … ‘: Peroration by Dr. King sums up a day the capital will remember», The New York Times (August 29, 1963).

- ^ Mary McGrory, «Polite, Happy, Helpful: The Real Hero Was the Crowd», Boston Globe (August 29, 1963).

- ^ Marquis Childs, «Triumphal March Silences Scoffers», The Washington Post (August 30, 1963).

- ^ Max Freedman, «The Big March in Washington Described as ‘Epic of Democracy‘«, Los Angeles Times (September 9, 1963).

- ^ Tim Weiner, Enemies: A history of the FBI, New York: Random House, 2012, p. 235

- ^ Memo hosted by American Radio Works (American Public Media), «The FBI’s War on King Archived August 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Reeves, Richard, President Kennedy: Profile of Power,1993, pp. 580–584

- ^ Clayborne Carson Archived January 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine «King, Obama, and the Great American Dialogue», American Heritage, Spring 2009.

- ^ «Martin Luther King». The Nobel Foundation. 1964. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ «Moodswings’s ‘Spiritual High (Part III)’ – Discover the Sample Source». WhoSampled. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Keller, Douglas D. (January 20, 1993). «Varied Moodswings album provides musing to fuel any emotion». The Tech. 112 (66): 6. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ «The National Recording Registry 2002». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ «We Shall Overcome, Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement: Lincoln Memorial». US National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b «Tears Fall at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial». WUSA. June 30, 2011. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ «God’s Trombone: Remembering King’s Dream». BBC. August 26, 2013. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Zeke J (August 28, 2013). «In Commemorative MLK Speech, President Obama Recalls His Own 2008 Dream». Time. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ Galloway, Jim (October 12, 2015). «A monument to MLK will crown Stone Mountain». The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ Korte, Gregory (April 21, 2016). «Anti-slavery activist Harriet Tubman to replace Jackson on $20 bill». USA Today. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Rachaell (September 22, 2016). «Why Is August 28 So Special To Black People? Ava DuVernay Reveals All in New NMAAHC Film». Essence. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ «Your Record». Science Friday. October 7, 2016. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Wells, Myrydd (August 28, 2017). «Georgia Capitol’s Martin Luther King Jr. statue unveiled on 54th anniversary of «I Have a Dream»«. Atlanta. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ Francis, Bryant (August 26, 2021). «Epic and Time Magazine debut interactive MLK Jr. exhibit in Fortnite». Game Developer. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie. «‘I Have a Dream’ speech still private property». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Lauren (August 23, 2013). «I Have a Copyright: The Problem With MLK’s Speech». Mother Jones. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Volz, Dustin (August 20, 2013). «The Copyright Battle Behind ‘I Have a Dream’«. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (January 15, 2017). «‘I Have a Dream’ speech owned by Martin Luther King’s family». Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Suarez, Xavier L. (October 27, 2011). Democracy in America: 2010. AuthorHouse. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4567-6056-4. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Karen Price Hossell (December 5, 2005). I Have a Dream. Heinemann-Raintree Library. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-1-4034-6811-6. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Weir, Tom (February 27, 2009). «George Raveling owns MLK’s ‘I have a dream’ speech». USA Today. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (August 28, 2003). «Guardian of The Dream». Time. Archived from the original on August 29, 2003. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Donohue, Peter M. (August 27, 2021). «A Message from the President | Villanova University». Villanova University. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ «Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr». Billboard. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

External links

- Full text at the BBC

- Video of «I Have a Dream» speech, from LearnOutLoud.com

- «I Have a Dream» Text and Audio from AmericanRhetoric.com

- «I Have A Dream» speech – Dr. Martin Luther King with music by Doug Katsaros on YouTube

- Deposition concerning recording of the «I Have a Dream» speech

- Lyrics of the traditional spiritual «Free At Last»

- MLK: Before He Won the Nobel Archived January 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life magazine

- Chiastic outline of Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream» speech

- I Have a Dream Summary (Class 12)

- I Have A Dream Archived February 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

Coordinates: 38°53′21.4″N 77°3′0.5″W / 38.889278°N 77.050139°W

«У меня есть мечта» (англ. «I have a dream») — знаменитая речь Мартина Лютера Кинга, произнесенная им 28 августа 1963 года со ступеней Мемориала Линкольна.

Эта речь считается одной из лучших речей в истории и была признана лучшей речью XX века американским сообществом ораторского искусства.

Речь была произнесена во время одного из самых важнейших этапов Американского движения за права темнокожих в США 1955—1968 годов во время Марша на Вашингтон за рабочие места и свободу.

28 августа 1963 года под почти безоблачным небом около Мемориала Линкольна в Вашингтоне собрались более 250 000 человек, пятая часть из которых — белые, под лозунгом «работа и свобода».

В список ораторов вошли ораторы почти из всех сегментов общества- трудовые лидеры, духовенство, кинозвезды, и другие.

Каждому из выступающих было отведено по пятнадцать минут, но день принадлежал молодому и харизматичному баптистскому проповеднику из Теннесси.

Д-р Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший первоначально подготовил краткое и несколько формальное изложение страданий афроамериканцев, пытающихся реализовать свою свободу в обществе, скованном дискриминацией. Он собирался сесть, когда певица Махалия Джексон крикнула: «Расскажи им о своей мечте, Мартин! Расскажи им о своем сне!»

Воодушевленный криками зрителей, Кинг использовал некоторые из своих прошлых выступлений, и результатом стало знаковое заявление о гражданских правах в Америке-мечта всех людей, всех рас, цветов кожи и происхождения, разделяя Америку, отмеченную свободой и демократией.

Речь Кинга изобиловала отсылками к Библии, а также обращалась к понятиям американской свободы и равенства, провозглашенным задолго до этого, но так не воплотившимся в жизнь для афроамериканцев. Кинг, будучи опытным проповедником, идеально построил темп речи, совместив его со своим певческим тембром. Речь произвела неизгладимое впечатление на всех участников марша и заставила в конечном итоге власти США предоставить всем своим гражданам равные права

«У меня есть мечта». Речь Мартина Лютера Кинга 28 августа 1963г.

(в переводе на русский язык)

Пять десятков лет назад великий американец, под чьей символической сенью мы сегодня собрались, подписал Прокламацию об освобождении негров. Этот важный указ стал величественным маяком света надежды для миллионов черных рабов, опаленных пламенем испепеляющей несправедливости. Он стал радостным рассветом, завершившим долгую ночь пленения.

Но по прошествии ста лет мы вынуждены признать трагический факт, что негр все еще не свободен. Спустя сто лет жизнь негра, к сожалению, по-прежнему калечится кандалами сегрегации и оковами дискриминации. Спустя сто лет негр живет на пустынном острове бедности посреди огромного океана материального процветания. Спустя сто лет негр по-прежнему томится на задворках американского общества и оказывается в ссылке на своей собственной земле. Вот мы и пришли сегодня сюда, чтобы подчеркнуть драматизм плачевной ситуации.

В каком-то смысле мы прибыли в столицу нашего государства, чтобы получить наличные по чеку. Когда архитекторы нашей республики писали прекрасные слова Конституции и Декларации независимости, они подписывали тем самым вексель, который предстояло унаследовать каждому американцу. Согласно этому векселю, всем людям гарантировались неотъемлемые права на жизнь, свободу и стремление к счастью.

Сегодня стало очевидным, что Америка оказалась не в состоянии выплатить по этому векселю то, что положено ее цветным гражданам. Вместо того чтобы выплатить этот святой долг, Америка выдала негритянскому народу фальшивый чек, который вернулся с пометкой «нехватка средств». Но мы отказываемся верить, что банк справедливости обанкротился. Мы отказываемся верить, что в огромных хранилищах возможностей нашего государства недостает средств. И мы пришли, чтобы получить по этому чеку — чеку, по которому нам будут выданы сокровища свободы и гарантии справедливости. Мы прибыли сюда, в это священное место, также для того, чтобы напомнить Америке о настоятельном требовании сегодняшнего дня. Сейчас не время удовлетворяться умиротворяющими мерами или принимать успокоительное лекарство постепенных решений. Настало время выйти из темной долины сегрегации и вступить на залитый солнцем путь расовой справедливости. Настало время открыть двери возможностей всем Божьим детям. Настало время вывести нашу нацию из зыбучих песков расовой несправедливости к твердой скале братства.

Для нашего государства было бы смертельно опасным проигнорировать особую важность данного момента и недооценить решимость негров. Знойное лето законного недовольства негров не закончится, пока не настанет бодрящая осень свободы и равенства. 1963 год — это не конец, а начало. Тем, кто надеется, что негру нужно было выпустить пар и что теперь он успокоится, предстоит суровое пробуждение, если наша нация возвратится к привычной повседневности. До тех пор пока негру не будут предоставлены его гражданские права, Америке не видать ни безмятежности, ни покоя. Революционные бури будут продолжать сотрясать основы нашего государства до той поры, пока не настанет светлый день справедливости.

Но есть еще кое-что, что я должен сказать моему народу, стоящему на благодатном пороге у входа во дворец справедливости. В процессе завоевания при надлежащего нам по праву места мы не должны давать оснований для обвинений в неблаговидных поступках. Давайте не будем стремиться утолить нашу жажду свободы, вкушая из чаши горечи и ненависти.

Мы должны всегда вести нашу борьбу с благородных позиций достоинства и дисциплины. Мы не должны позволить, чтобы наш созидательный протест выродился в физическое насилие. Мы должны стремиться достичь величественных высот, отвечая на физическую силу силой духа. Замечательная воинственность, которая овладела негритянским обществом, не должна привести нас к недоверию со стороны всех белых людей, поскольку многие из наших белых братьев осознали, о чем свидетельствует их присутствие здесь сегодня, что их судьба тесно связана с нашей судьбой и их свобода неизбежно связана с нашей свободой.

Мы не можем идти в одиночестве.

И начав движение, мы должны поклясться, что будем идти вперед.Мы не можем повернуть назад. Есть такие, которые спрашивают тех, кто предан делу защиты гражданских прав: «Когда вы успокоитесь?» Мы никогда не успокоимся, пока наши тела, отяжелевшие от усталости, вызванной долгими путешествиями, не смогут получить ночлег в придорожных мотелях и городских гостиницах. Мы не успокоимся, пока основным видом передвижений негра остается переезд из маленького гетто в большое. Мы не успокоимся, пока негр в Миссисипи не может голосовать, а негр в Нью-Йорке считает, что ему не за что голосовать. Нет, нет у нас оснований для успокоения, и мы никогда не успокоимся, пока справедливость не начнет струиться, подобно водам, а праведность не уподобится мощному потоку.

Я не забываю, что многие из вас прибыли сюда, пройдя через великие испытания и страдания. Некоторые из вас прибыли сюда прямиком из тесных тюремных камер. Некоторые из вас прибыли из районов, в которых за ваше стремление к свободе на вас обрушились бури преследований и штормы полицейской жестокости. Вы стали ветеранами созидательного страдания. Продолжайте работать, веруя в то, что незаслуженное страдание искупается.

Возвращайтесь в Миссисипи, возвращайтесь в Алабаму, возвращайтесь в Луизиану, возвращайтесь в трущобы и гетто наших северных городов, зная, что так или иначе эта ситуация может измениться и изменится. Давайте не будем страдать в долине отчаяния.

Я говорю вам сегодня, друзья мои, что, несмотря на трудности и разочарования, у меня есть мечта. Это мечта, глубоко укоренившаяся в Американской мечте.

у меня есть мечта, что настанет день, когда наша нация воспрянет и доживет до истинного смысла своего девиза: «Мы считаем самоочевидным, что все люди созданы равными».

у меня есть мечта, что на красных холмах Джорджии настанет день, когда сыновья бывших рабов и сыновья бывших рабовладельцев смогут усесться вместе за столом братства.

у меня есть мечта, что настанет день, когда даже штат Миссисипи, пустынный штат, изнемогающий от накала несправедливости и угнетения, будет превращен в оазис свободы и справедливости.

у меня есть мечта, что настанет день, когда четверо моих детей будут жить в стране, где о них будут судить не по цвету их кожи, а по тому, что они собой представляют.

у меня есть мечта сегодня.

у меня есть мечта, что настанет день, когда в штате Алабама, губернатор которого ныне заявляет о вмешательстве во внутренние дела штата и непризнании действия принятых конгрессом законов, будет создана ситуация, в которой маленькие черные мальчики и девочки смогут взяться за руки с маленькими белыми мальчиками и девочками и идти вместе, подобно братьям и сестрам.

у меня есть мечта сегодня.

у меня есть мечта, что настанет день, когда все низины поднимутся, все холмы и горы опустятся, неровные местности будут превращены в равнины, искривленные места станут прямыми, величие Господа предстанет перед нами и все смертные вместе удостоверятся в этом.

Такова наша надежда. Это вера, с которой я возврашаюсь на Юг.

С этой верой мы сможем вырубить камень надежды из горы отчаяния. С этой верой мы сможем превратить нестройные голоса нашего народа в прекрасную симфонию братства. С этой верой мы сможем вместе трудиться, вместе молиться, вместе бороться, вместе идти в тюрьмы, вместе защищать свободу, зная, что однажды мы будем свободными.

Это будет день, когда все Божьи дети смогут петь, вкладывая в эти слова новый смысл: «Страна моя, это Я тебя, сладкая земля свободы, это я тебя воспеваю. Земля, где умерли мои отцы, земля гордости пилигримов, пусть свобода звенит со всех горных склонов».

И если Америке предстоит стать великой страной, это должно произойти.

Пусть свобода звенит с вершин изумительных холмов Нью-Хэмпшира!

Пусть свобода звенит с могучих гор Нью-Йорка!

Пусть свобода звенит с высоких Аллегенских гор Пенсильвании!

Пусть свобода звенит с заснеженных Скалистых гор Колорадо!

Пусть свобода звенит с изогнутых горных вершин Калифорнии!

Пусть свобода звенит с горы Лукаут в Теннесси!

Пусть свобода звенит с каждого холма и каждого бугорка Миссисипи!

С каждого горного склона пусть звенит свобода!

Когда мы позволим свободе звенеть, когда мы позволим ей звенеть из каждого села и каждой деревушки, из каждого штата и каждого города, мы сможем ускорить наступление того дня, когда все Божьи дети, черные и белые, евреи и язычники, протестанты и католики, смогут взяться за руки и запеть слова старого негритянского духовного гимна: «Свободны наконец! Свободны наконец! Спасибо всемогущему Господу, мы свободны наконец!»

«i have a dream». Речь Мартина Лютера Кинга 28 августа 1963г.

(на английском языке)

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check that has come back marked «insufficient funds.»

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and security of justice. We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end but a beginning. Those who hoped that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, «When will you be satisfied?» We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating «for whites only.» We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no we are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today my friends — so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: «We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.»

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification — one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning «My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my father’s died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring!»

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi — from every mountainside.

Let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring — when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children — black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics — will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: «Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!»