You probably think learning how to write in Chinese is impossible.

And I get it.

I’m a native English speaker, and I know how complex Chinese characters seem.

But you’re about to learn that it’s not impossible.

I’ve teamed up with Kyle Balmer from Sensible Chinese to show you how you can learn the basic building blocks of the Chinese written language, and build your Chinese vocabulary quickly.

First, you’ll learn the basics of how the Chinese written language is constructed. Then, you’ll get a step-by-step guide for how to write Chinese characters sensibly and systematically.

Wondering how it can be so easy?

Then let’s get into it.

Don’t have time to read this now? Click here to download a free PDF of the article

By the way, if you want to learn Chinese fast and have fun, my top recommendation is Chinese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Chinese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Chinese through story… not rules.

It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

How To Write In Chinese

Chinese is a complex language with many dialects and varieties.

Before we dive into learning to write Chinese characters, let’s just take a second to be clear exactly what we’ll be talking about.

First, you’ll be learning about Mandarin Chinese, the “standard” dialect. There are 5 main groups of dialects and perhaps 200 individual dialects in China & Taiwan. Mandarin Chinese is the “standard” used in Beijing and spoken or understood, by 2/3 of the population.

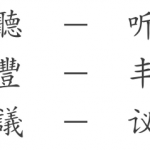

Second, there are two types of Chinese characters: Traditional and Simplified. In this article, we’ll be talking about Simplified Chinese characters, which are used in the majority of Mainland China.

There is an ongoing politicised debate about the two kinds of characters, and those asking themselves: “Should I learn traditional or simplified Chinese characters?” can face a difficult choice.

- For more on difference between Simplified and Traditional characters read this article

- To learn more about “the debate” read this excellent Wikipedia article

- If you want to switch Simplified characters into Traditional, you might like the fantastic New Tong Wen Tang browser plugin

First Steps in Learning Chinese Characters

When learning a European language, you have certain reference points that give you a head start.

If you’re learning French and see the word l’hotel, for example, you can take a pretty good guess what it means! You have a shared alphabet and shared word roots to fall back on.

In Chinese this is not the case.

When you’re just starting out, every sound, character, and word seems new and unique. Learning to read Chinese characters can feel like learning a whole set of completely illogical, unconnected “squiggles”!

The most commonly-taught method for learning to read and write these “squiggles” is rote learning.

Just write them again and again and practise until they stick in your brain and your hand remembers how to write them! This is an outdated approach, much like reciting multiplication tables until they “stick”.

I learnt this way.

Most Chinese learners learnt this way.

It’s painful…and sadly discourages a lot of learners.

However, there is a better way.

Even without any common reference points between Chinese and English, the secret is to use the basic building blocks of Chinese, and use those building blocks as reference points from which to grow your knowledge of written Chinese.

This article will:

- Outline the different levels of structure inherent in Chinese characters

- Show you how to build your own reference points from scratch

- Demonstrate how to build up gradually without feeling overwhelmed

The Structure Of Written Chinese

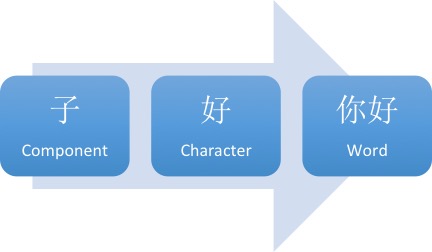

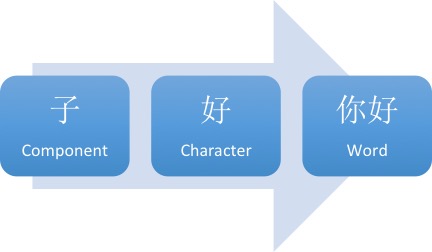

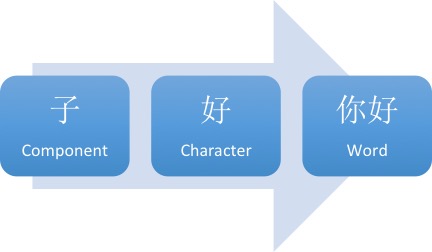

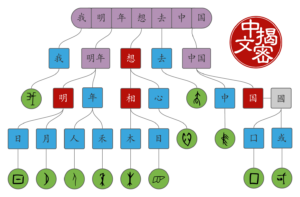

The basic structure of written Chinese is as follows:

I like to think of Chinese like Lego... it’s very “square”!

The individual bricks are the components (a.k.a radicals).

We start to snap these components together to get something larger – the characters.

We can then snap characters together in order to make Chinese words.

Here’s the really cool part about Chinese: Each of these pieces, at every level, has meaning.

The component, the character, the word… they all have meaning.

This is different to a European language, where the “pieces” used to make up words are letters.

Letters by themselves don’t normally have meaning and when we start to clip letters together we are shaping a sound rather than connecting little pieces of meaning. This is a powerful difference that comes into play later when we are learning vocabulary.

Let’s look at the diagram again.

Here we start with the component 子. This has the meaning of “child/infant”.

The character 好 (“good”) is the next level. Look on the right of the character and you’ll see 子. We would say that 子 is a component of 好.

Now look at the full word 你好 (“Hello”). Notice that the 子 is still there.

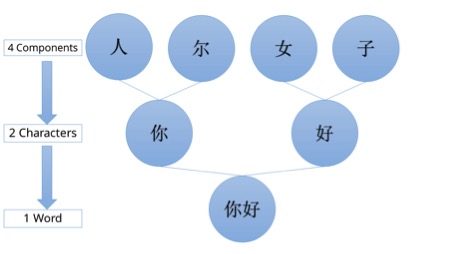

- The character 好 is built of the components 女 and 子.

- The character 你 is built from 人 + 尔.

- The word 你好 in turn is constructed out of 你 + 好.

Here’s the complete breakdown of that word in an easy-to-read diagram:

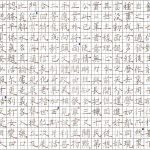

Now look at this photo of this in real life!

Don’t worry if you can’t understand it. Just look for some shapes that you have seen before.

The font is a little funky, so here are the typed characters: 好孩子

What components have you seen before?

Did you spot them?

This is a big deal.

Here’s why…

Why Character Components Are So Important

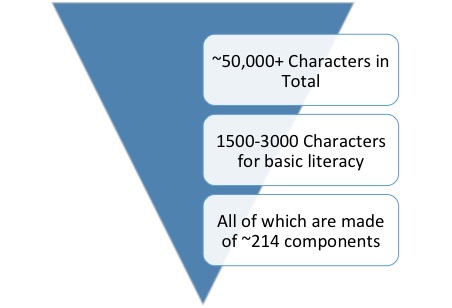

One of the big “scare stories” around Chinese is that there are 50,000 characters to learn.

Now, this is true. But learning them isn’t half as bad as you think.

Firstly, only a few thousand characters are in general everyday use so that number is a lot more manageable.

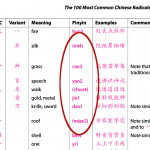

Second, and more importantly, those 50,000 characters are all made up of the same 214 components.

And you already know one of them: 子 (it’s one of those 214 components).

The fact that you can now recognise the 子 in the image above is a huge step forward.

You can already recognise one of the 214 pieces all characters are made up of.

Even better is the fact that of these 214 components it’s only the 50-100 most common you’ll be running into again and again.

This makes Chinese characters a lot less scary.

Once you get a handle on these basic components, you’ll quickly recognise all the smaller pieces and your eyes will stop glazing over!

This doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily know the meaning or how to pronounce the words yet (we’ll get onto this shortly) but suddenly Chinese doesn’t seem quite so alien any more.

Memorising The Components Of Chinese Characters

Memorising the pieces is not as important as simply realising that ALL of Chinese is constructed from these 214 pieces.

When I realised this, Chinese became a lot more manageable and I hope I’ve saved you some heartache by revealing this early in your learning process!

Here are some useful online resources for learning the components of Chinese characters:

- An extensive article about the 214 components of Chinese characters with a free printable PDF poster.

- Downloadable posters of all the components, characters and words.

- If you like flashcards, there’s a great Anki deck here and a Memrise course here.

- Wikipedia also has a sweet sortable list here.

TAKEAWAY: Every single Chinese character is composed of just 214 “pieces”. Only 50-100 of these are commonly used. Learn these pieces first to learn how to write in Chinese quickly.

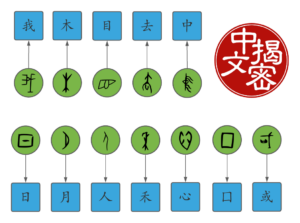

Moving From Components To Chinese Characters

Once you’ve got a grasp of the basic building blocks of Chinese it’s time to start building some characters!

We used the character 好 (“good”) in the above example. 好 is a character composed of the components 女 (“woman”) and 子 (“child”).

Unlike the letters of the alphabet in English, these components have meaning.

(They also have pronunciation, but for the sake of simplicity we’ll leave that aside for now!)

- 女 means “woman” and 子 means “child”.

- When they are put together, 女 and 子 become 好 …and the meaning is “good”.

- Therefore “woman” + “child” = “good” in Chinese 🙂

When learning how to write in Chinese characters you can take advantage of the fact that components have their own meanings.

In this case, it is relatively easy to make a mnemonic (memory aid) that links the idea of a woman with her baby as “good”.

Because Chinese is so structured, these kind of mnemonics are an incredibly powerful tool for memorisation.

Some characters, including 好, can also be easily represented graphically. ShaoLan’s book Chineasy does a fantastic job of this.

Here’s the image of 好 for instance – you can see the mother and child.

Visual graphics like these can really help in learning Chinese characters.

Unfortunately, only around 5% of the characters in Chinese are directly “visual” in this way. These characters tend to get the most attention because they look great when illustrated.

However, as you move beyond the concrete in the more abstract it becomes harder and harder to visually represent ideas.

Thankfully, the ancient Chinese had an ingenious solution, a solution that actually makes the language a lot more logical and simple than merely adding endless visual pictures.

Watch Me Write Chinese Characters

In the video below, which is part of a series on learning to write in Chinese, I talk about the process of actually writing out the characters. Not thousands of times like Chinese schoolchildren. But just as a way to reinforce my learning and attack learning Chinese characters from different angles.

My Chinese handwriting leaves a lot to be desired. But it’s more about a process of reinforcing my language learning via muscle memory than perfecting my handwriting.

You’ll also hear me discuss some related issues such as stroke order and typing in Chinese.

The Pronunciation Of Chinese Characters

The solution was the incredibly unsexy sounding… (wait for it…) “phono-semantic compound character”.

It’s an awful name, so I’m going to call them “sound-meaning characters” for now!

This concept is the key to unlocking 95% of the Chinese characters.

A sound-meaning character has a component that tells us two things:

- the meaning

- a clue to how the character is pronounced

So, in simple terms:

95% of Chinese characters have a clue to the meaning of the character AND its pronunciation.

Example:

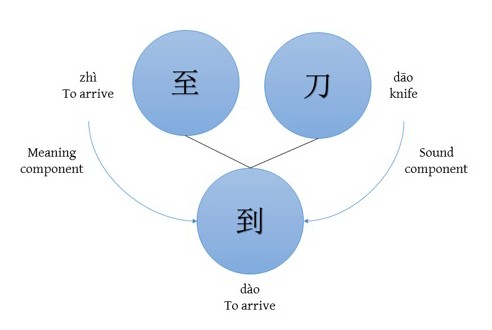

到 means “to arrive”.

This character is made of two components. On the left is 至 and on the right is 刀.

These are two of the 214 components that make up all characters. 至 means “to arrive” and 刀 means “knife”.

Any idea which one gives us the meaning? Yup – it’s 至, “to arrive”! (That was an easy one 🙂 )

But how about the 刀? This is where it gets interesting.

到 is pronounced dào.

刀, “knife” is pronounced dāo.

The reason the 刀 is placed next to 至 in the character 到 is just to tell us how to pronounce the character! How cool is that?

Now, did you notice the little lines above the words: dào and dāo?

Those are the tone markers, and in this case they are both slightly different. These two characters have different tones so they are not exactly the same pronunciation.

However, the sound-meaning compound has got us 90% of the way to being able to pronounce the character, all because some awesome ancient Chinese scribe thought there should be a shortcut to help us remember the pronunciation!

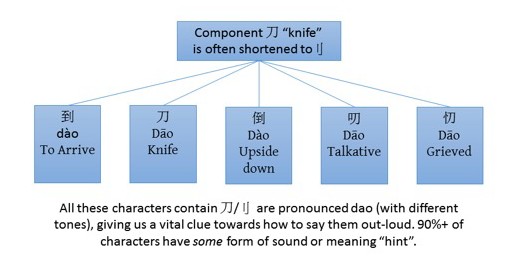

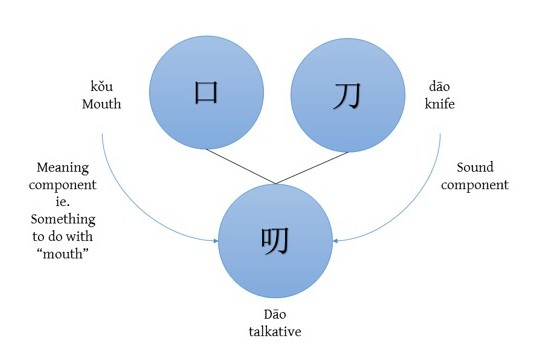

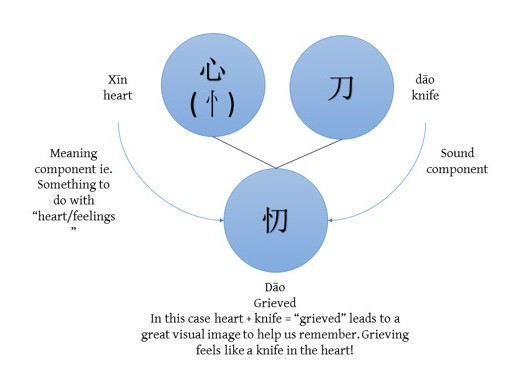

Let’s look at a few more examples of how 刀 is used in different words to give you an idea of the pronunciation.

Even if sometimes:

- the sound-meaning character gives us the exact sound and meaning

- or it gets us in the ballpark

- or worse it is way off because the character has changed over the last 5,000 years!

Nevertheless, there’s a clue about the pronunciation in 95% of all Chinese characters, which is a huge help for learning how to speak Chinese.

TAKEAWAY: Look at the component parts as a way to unlock the meaning and pronunciations of 95% of Chinese characters. In terms of “hacking” the language, this is the key to learning how to write in Chinese quickly.

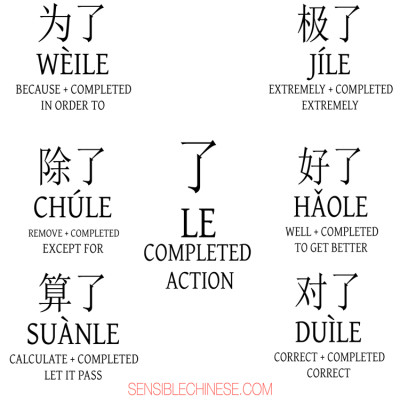

From Chinese Characters To Chinese Words

First we went from components to characters.

Next, we are going from characters to words.

Although there are a lot of one-character words in Chinese, they tend to either be classically-rooted words like “king” and “horse” or grammatical particles and pronouns.

The vast majority of Chinese words contain two characters.

The step from characters to words is where, dare I say it, Chinese script gets easy!

Come on, you didn’t think it would always be hard did you? 🙂

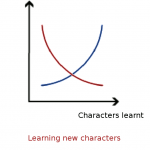

Unlike European languages Chinese’s difficulty is very front-loaded.

When you first learn to write Chinese, you’ll discover a foreign pronunciation system, a foreign tonal system and a very foreign writing system.

As an English speaker, you can normally have a good shot at pronouncing and reading words in other European languages, thanks to the shared alphabet.

Chinese, on the other hand, sucker-punches you on day one… but gets a little more gentle as you go along.

One you’ve realised these things:

- there aren’t that many components to deal with

- all characters are made up of these basic components

- words are actually characters bolted together

…then it’s a matter of just memorising a whole bunch of stuff!

That’s not to say there isn’t a lot of work involved, only to say that it’s not particularly difficult. Time-consuming, yes. Difficult, no.

This is quite different from European languages, which start off easy, but quickly escalate in difficulty as you encounter complicated grammar, tenses, case endings, technical vocabulary and so on.

Making words from Chinese characters you already know is easy and really fun. This is where you get to start snapping the lego blocks together and build that Pirate Island!

The Logic Of Chinese Writing

Here are some wonderful examples of the simplicity and logic of Chinese using the character 车 which roughly translates as “vehicle”.

- Water + Vehicle = Waterwheel = 水 +车

- Wind + Vehicle = Windmill = 风+车

- Electric + Vehicle = Tram/Trolley = 电+车

- Fire + Vehicle = Train = 火+车

- Gas + Vehicle = Car = 汽+车

- Horse + Vehicle = Horse and cart/Trap and Pony = 马+车

- Up + Vehicle = Get into/onto a vehicle =上+车

- Down + Vehicle = Get out/off a vehicle =下+车

- Vehicle + Warehouse = Garage = 车+库

- To Stop + Vehicle = to park = 停+车

Chinese is extremely logical and consistent.

This is a set of building blocks that has evolved over 5,000 years in a relatively linear progression. And you can’t exactly say the same about the English language!

Just think of the English words for the Chinese equivalences above:

Train, windmill, millwheel/waterwheel, tram/trolley, car/automobile, horse and cart/trap and pony.

Unlike Chinese where these concepts are all linked by 车 there’s very little consistency in our vehicle/wheel related vocabulary, and no way to link these sets of related concepts via the word itself.

English is a diverse and rich language, but that comes with its drawbacks – a case-by-case spelling system that drives learners mad.

Chinese, on the other hand, is precise and logical, once you get over the initial “alienness”.

Making The Complex Simple

This logical way of constructing vocabulary is not limited to everyday words like “car” and “train”. It extends throughout the language.

To take an extreme example let’s look at Jurassic Park.

The other day I watched Jurassic Park with my Chinese girlfriend. (OK, re-watched. It’s a classic!)

Part of the fun for me (annoyance for her) was asking her the Chinese for various dinosaur species.

Take a second to look through these examples. You’ll love the simplicity!

- T Rex 暴龙 = tyrant + dragon

- Tricerotops 三角恐龙 three + horn + dinosaur

- Diplodocus 梁龙 roof-beam + dragon

- Velociraptor 伶盗龙 clever + thief + dragon (or swift stealer dragon)

- Stegosaurus 剑龙 (double-edged) sword + dragon

- Dilophosaurus 双脊龙 double+spined+dragon

Don’t try to memorise these characters, just appreciate the underlying logic of how the complex concepts are constructed.

(Unless, of course, you are a palaeontologist…or as the Chinese would say a Ancient + Life + Animal + Scientist!).

I couldn’t spell half of these dinosaur names in English for this article. But once I knew how the construction of the Chinese word, typing in the right characters was simple.

Once you know a handful of characters, you can start to put together complete words, and knowing how to write in Chinese suddenly becomes a lot easier.

In a lot of cases you can take educated guesses at concepts and get them right by combining known characters into unknown words.

For more on this, check my series of Chinese character images that I publish on this page. They focus on Chinese words constructed from common characters, and help you understand more of the “building block” logic of Chinese.

TAKEAWAY: Chinese words are constructed extremely logically from the underlying characters. This means that once you’ve learned a handful of characters vocabulary acquisition speeds up exponentially.

How To Learn Written Chinese Fast

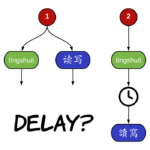

Before diving into learning characters, make sure you have a decent grounding in Chinese pronunciation via the pinyin system.

The reason for this is that taking on pronunciation, tones and characters from day one is really tough.

Don’t get me wrong, you can do it. Especially if you’re highly motivated. But for most people there’s a better way.

Learn a bit of spoken Chinese first.

With some spoken language under your belt, and an understanding of pronunciation and tones, starting to learn how to write in Chinese will seem a whole lot easier.

When you’re ready, here’s how to use all the information from this article and deal with written Chinese in a sensible way.

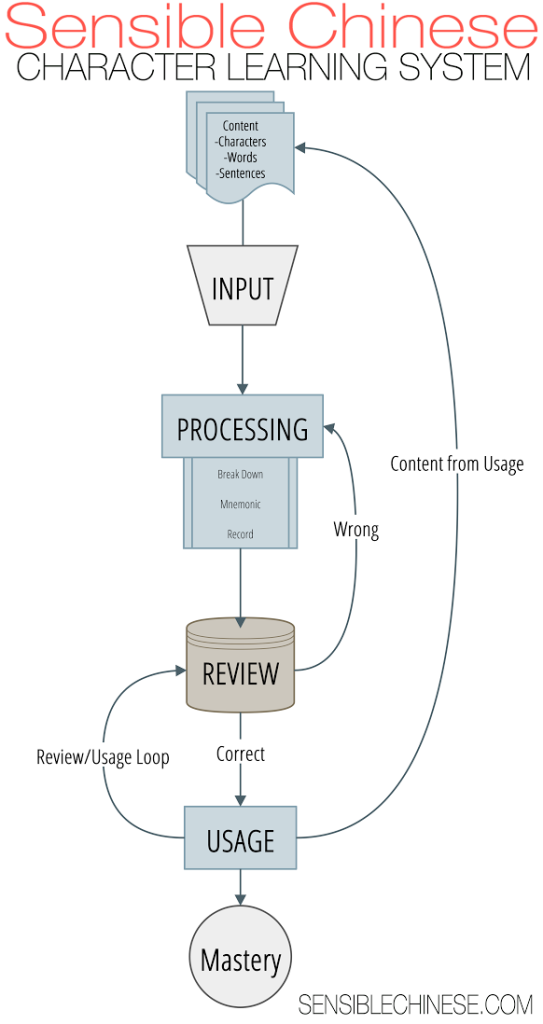

I’ve got a systematic approach to written Chinese which you can find in detail on Sensible Chinese.

Right now, I’m going to get you started with the basics.

The Sensible Character System

The four stages for learning Chinese characters are:

- Input

- Processing

- Review

- Usage

Sounds technical huh? Don’t worry, it’s not really.

1. Input

This part of the process is about choosing what you put into your character learning system.

If you’re working on the wrong material then you’re wasting your efforts. Instead choose to learn Chinese characters that you are like to want to use in the future.

My list in order of priority contains:

- daily life: characters/words I’ve encountered through daily life

- textbooks: characters/words I’ve learnt from textbooks

- frequency lists: characters/words I’ve found in frequency lists of the most common characters and words

2. Processing

This is the “learning” part of the system.

You take a new word or character and break it down into its component parts. You can then use these components to create memory aids.

Hanzicraft.com or Pleco’s built-in character decomposition tool are fantastic for breaking down new characters. These will be helpful until you learn to recognise the character components by sight. These tools will also show you if there are sound-meaning component clues in the character.

Use the individual components of a character to build a “story” around the character. Personal, sexy and violent stories tend to stick in the mind best! 🙂 I also like to add colours into my stories to represent the tones (1st tone Green, 2nd tone Blue etc.)

3. Review

After the “input” and the “process”… it’s time to review it all!

The simplest review system is paper flashcards which you periodically use to refresh your memory.

A more efficient method can be found in software or apps that use a Spaced Repetition System, like Anki or Pleco.

An important point: Review is not learning.

It’s tempting to rely on software like Anki to drill in the vocabulary through brute-force repetition. But don’t skip the first two parts – processing the character and creating a mnemonic are key parts of the process.

4. Usage

It isn’t enough to just learn and review your words… you also need to put them into use!

Thankfully, technology has made this easier than ever. Finding a language exchange partner or a lesson with a cost-effective teacher is super simple nowadays, so there’s no excuse for not putting your new vocabulary into action!

The resources I personally use are:

- Spoken – iTalki

- Written – Lang-8

- Short form written – WeChat/HelloTalk

Importantly, whilst you are using your current vocabulary in these forms of communication, you’ll be picking up new content all the time, which you can add back into your system.

The four steps above are a cycle that you will continue to rotate through – all the corrections and new words you receive during usage should become material to add to the system.

To recap, the four steps of systematically learning Chinese characters are:

- Input

- Processing

- Review

- Usage

By building these steps into your regular study schedule you can steadily work through the thousands of Chinese characters and words you’ll need to achieve literacy.

This is a long-haul process! So having a basic system in place is very important for consistency.

You can find out a lot more about The Sensible Chinese Character Learning System and how to write in Chinese here.

Top Chinese Learning Links And Resources

- Chinese Language Learning Resource List – a curated list of tools and content available online and in print to help your Chinese learning, all categorised by usage type.

- Sensible Character Learning System – the full system outlined in a series of blog articles for those who want more detail and tips on how to refine their character learning.

- 111 Mandarin Chinese resources you wish you knew – Olly’s huge list of the best resources on the web for learning Chinese

I hope you enjoyed this epic guide to learning how to write in Chinese!

Please share this post with any friends who are learning Chinese, then leave us a comment below!

Phonetic script (Hanyu Pinyin)

wŏ

Listen to pronunciation

(Mandarin = standard Chinese without accent)

You cannot listen to the pronunciation of wo because your browser does not support the audio element.

You’re listening to the natural voice of a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese.

English translations

I, me,

myself

Chinese character and stroke order animation«How do I write 我 ( wŏ ) correctly?»

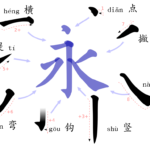

The strokes that all Chinese characters are composed of are to be written in a certain order which has originally been defined by Chinese calligraphy. Writing all characters according to the same rules assures that their intended shape and style are generally preserved even if written by different writers.

This dictionary shows you the correct stroke order as an animation for all characters so you can learn and understand how to write the character correctly.

:

The traditional Chinese characters of wŏ are identical with the modern (simplified) characters displayed above.

Chinese Pinyin example sentence with 我 ( wo / wŏ ) ⓘWriting in Pinyin

Before using this Pinyin example sentence, consider that Chinese characters should always be your first choice in written communication.

If you cannot use Chinese characters, it is preferable to use the Pinyin with tones. Only use the Pinyin without tones if there’s no other option (e.g. writing a text message from/to a mobile phone that doesn’t support special characters such as ā, í, ŏ, ù).

Wo gang dao zheli.

Wŏ gāng dào zhèlĭ.

– English translation: I just arrived here.

Tags and additional information

(Meaning of individual characters, character components etc.)

my | we

我 ( wo / wŏ ) belongs to the 10 most common Chinese characters (rank 7)

Chinese example words containing the character 我 ( wo / wŏ )

我一个人 ( wŏ yī gè rén = me alone ), 我们 ( wŏmen = we )

Report missing or erroneous translation of wo in English

Contact us! We always appreciate good suggestions and helpful criticism.

Even with the right method, it’s a task that requires time and perseverance.

In this article, I summarise the best advice I have on how to learn Chinese characters, based on more than ten years of learning, teaching and writing about Chinese.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

My best advice on how to learn Chinese characters

I have much to say when it comes to learning Chinese characters, not only because it’s a complex task in itself, but also because it’s handled badly in many classrooms. I have already written about most of these topics before and my goal in this article is to summarise the most important advice.

That means that I will adress most questions you might have about learning Chinese characters, but that I can’t put all the details in this article because it would turn it into a book. Instead, I will provide links to further reading for those who want more.

Note: There is a lot of information here. You don’t have to read through everything from start to finish, so find the answers to the questions you have about learning Chinese characters instead.

To make it easier for you to find what you’re looking for, here’s an overview of the content in this article. If you’re looking for something in particular, just searching on this page works too!

- Understanding Chinese characters and the Chinese writing system

- Understanding the Chinese writing system

- Learning more about Chinese characters

- Finding information about Chinese characters

- Variation in Chinese characters

- Learning to read and write Chinese characters

- Which Chinese characters and words should you learn?

- How to learn Chinese characters

- Things you can safely ignore when learning Chinese characters

- More about writing Chinese characters by hand

- Reviewing and remembering Chinese characters

- How to not forget the Chinese characters you’ve learnt

- Mnemonics and improving your memory

- Practical considerations: Where and how to review

- Beyond beginner: Character learning in the long term

Before we get started though, let’s discuss when you should learn Chinese characters. I assume that you’re not only interested in the spoken language (I doubt you’d be reading this article if you were).

1. Understanding Chinese characters and the Chinese writing system

In part one, we’ll look at how to make sense of the Chinese writing system and understand how characters work. Understanding is important, because if research into learning tells us anything, it is that learning things that don’t mean anything is hard. The worst case scenario is regarding characters as a jumble of disconnected strokes and try to learn them through mindless repetition.

Back to index

1.1 Understanding the Chinese writing system

To help you figure out how the writing system works, I’ve written an in-depth series about words, characters, components and strokes, but since not all of you will be interested in reading all of that right now, here’s a brief summary with links to the main articles in the series.

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell – This is an introduction to the whole series and includes some advice on how to learn characters as an adult. The main point here is that Chinese characters aren’t pictures and that you as an adult learner can benefit immensely from understanding how characters work. I also talk about when to learn the writing system in relation to the spoken language (the default option should be spoken language first), the importance of reading, and the relationship between being able to read, write by hand and type in Chinese, which is rather different from most other languages. I also go through five things to avoid when learning characters: Don’t waste time learning the names of all the strokes, don’t obsess over theory, don’t clump reviews together, don’t worry if your handwriting is ugly, and don’t feel too daunted by the journey ahead,

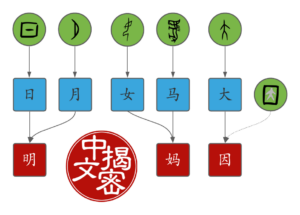

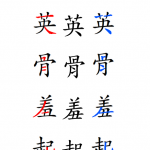

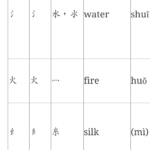

The building blocks of Chinese, part 2: Basic characters, components and radicals – Chinese characters started out as pictures representing objects, such as 木 tree, 人 person, 日 sun, and 月 moon. While most characters aren’t this simple, learning the basic characters is still very important, as they are the building blocks of all other characters. When included in other characters as components, they often provide something, such as sound or meaning, to that character (they are functional components). In each character, one specific component is used to sort the character in traditional dictionaries (this is called the radical). This article also goes through how to memorise these basic characters effectively, how to deal with basic characters that are’n’t compounds, but look rather complex anyway, along with the best tools available for learning the basics and a few important things about variations in Chinese characters.

- The building blocks of Chinese, part 3: Compound characters

– A vast majority of characters are compounds. For example, 休 (xiū), “to rest”, consists of a variant of 人 → 亻 (rén), “person”, and 木 (mù), “tree”, indicating a person resting in the shade of a tree. Two components forming a compound character. Another example is 妈 (mā), “mother”, consisting of 女 (nǚ), “woman” and 马 (mǎ), “horse”. In fact, most compounds are like this, with one component providing meaning (妈 and 女 are clearly related by meaning) and another sound (妈 and 马 use the same syllable). This article also talks about character evolution, corruption and tricky cases.

The building blocks of Chinese, part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters – When you know how compounds work, you can use this knowledge to learn more characters faster. Most compounds make sense in some way, but you need to make sure you understand the composition of the character for a correct analysis. As long as you identify the right building blocks, you don’t have to stick with the true history behind the character if you don’t find that helpful. Regardless, you should make use of mnemonics or memory techniques to make characters stick. This article contains lots of tips and tricks, as well as concrete examples!

The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words – It’s a common misconception that reading Chinese is all about characters, but in fact, meaning is conveyed through words, which usually have two characters. These words are sometimes obvious combinations of characters, but often are not. However, by understanding the individual characters (the building blocks), learning words become much easier and you can employ the same memory techniques I talked about when introducing characters compounds above. This article explains what words are in Chinese, why it’s important to understand the difference between words and characters, and how to learn both. There’s also a brief overview of where Chinese words come from, which is essential to understanding many of them!

The building blocks of Chinese, part 6: Learning and remembering compound words – Words in Chinese can look chaotic and be hard to understand, but when you understand why they are structured the way they are, it becomes much easier. In general, words are constructed the same way as phrases, meaning that in nouns, the core noun is on the right (same as when describing nouns in a normal phrase), and that in verbs, the main verb is on the left (just as verbs appear on the left of objects in normal sentences too). Many words also have prefixes or suffixes, and just like when learning other languages, understanding these makes learning words much easier. This article takes a look at how words work and how you can use that knowledge to make sense of them and remember them more effectively.

Back to index

1.2 Learning more about Chinese characters

There are also many articles dealing with more specific aspects of characters:

Back to index

1.3 Finding information about Chinese characters

As we have seen, vocabulary in Chinese is a multi-layered web and there’s much information you need to be able to look up when needed, although you should try to use learning methods and materials that limit the number of new characters. Here’s the best advice I have to offer about how to look up information about Chinese characters:

How to look up Chinese characters you don’t know – Looking up characters in a dictionary used to be quite difficult; I have even taken a course in how to use a dictionary! Fortunately, you don’t have to do that, because there are now digital dictionaries that work very well. In this article, I go through many different ways of looking up characters, including by writing on screen, by scanning text (OCR), by searching in Pinyin and by using radicals.

Looking up how to use words in Chinese the right way – Even advanced students are sometimes not very good at using dictionaries. Unlike when learning a language closely related to English, using a dictionary to find a word you want to say or write in Chinese is not as easy. Translating on a word level almost never works and you need to pay attention to context. This article teaches you the basics in how to use a dictionary for speaking and writing purposes.

21 essential dictionaries and corpora for learning Chinese – There are a ton of dictionaries available for learning Chinese, but which should you use? It depends on what you want to use it for, but Pleco or Hanping is a good start, and both contain many extra dictionary-add-ons. When it comes to web-based dictionaries, Youdao is my favourite. If this is not enough, this article goes into much more detail about various dictionaries and corpora (word banks).

The Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters – I want to give this dictionary a special mention because it’s the best way for students to access up-to-date information about Chinese character etymology. The link goes to my in-depth review of the dictionary, which I think is a must for students and teachers who are interested in learning more about how Chinese characters work. It’s a one-time purchase that will be useful for as long as you learn characters.

Apart from looking up characters in general,you also need resources to move up and down the knowledge web, either zooming in to look at the building blocks or zooming out to put the character in context. Some of these resources overlap with those mentioned above, but this is a different way of sorting them and is quite useful if you need to zoom!

Zooming in: The tools you need to break down and understand Chinese characters – In order to learn efficiently, it’s important that you integrate your knowledge. This means being able to break down words into characters, and characters into components. This first article goes through the tools and resources you need to do so.

Zooming out: The resources you need to put Chinese in context – In this second article, we look at tools for zooming out and putting things in context. This is an incredibly important step, especially since Chinese is very distant from English, and characters and words really need to be studied in context.

Panning: How to keep similar Chinese characters and words separate – In the third article, we look at how to pan, or in other words, how to learn about how components, characters and words relate to each other on the same level. This is necessary to keep similar components, characters and words apart, but a word of warning: don’t try to learn many similar things at once; it will make it easier to mix them up. Instead, only pan when you have a problem you need to sort out (more about this later).

Back to index

1.4 Variation in Chinese characters

As if learning thousands of characters weren’t enough, there’s also a lot of variation going on, such as that between handwriting and computer fonts, simplified and traditional characters, or just some character variants that look different in different contexts. Here’s my best advice regarding how to deal with these problems and find the information you need:

Learning simplified and traditional Chinese – Contrary to what you might have heard, the differences between simplified and traditional Chinese are not that big. Which set you start with depends largely on practical considerations: most people learn simplified, but learn traditional if you have special interest in Taiwan or Hong Kong. Learning both sets is not hard once you’ve learnt one of them.

Are simplified characters really simpler to learn? Given that one character set is simplified and was standardised with the explicit goal to increase literacy, many just assume that simplified characters are easier to learn. But are they really? Fewer strokes does not mean easier to learn, especially not in this modern age of digital input systems!

Chinese character variants and fonts for language learners – Most students at some point feel confused and frustrated by the unpredictable way characters are displayed on phones and computers. By understanding the problem and using the right fonts, you can make sure you learn to write characters that match the standard you want to follow.

How to verify that you use the right Chinese font – When I started writing characters, I accidentally used a Japanese font. Don’t do that. Even using a Chinese font that doesn’t follow the right standard might cost you points on a test, even if it’s unlikely to cause people to not understand what you write. This article contains the fonts you need, as well as a step by step guide for how to check that your computer or phone is using the right font.

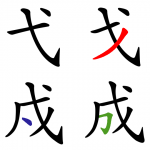

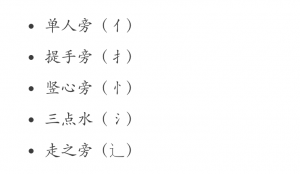

Shape-shifting character components – Pay attention to components that change shape depending on where they appear in a character. These are not really different characters, but they can appear so to beginners. Some important examples include 人, “person”, being written 亻when it appears on the left in a character, and 火, “fire”, being written 灬 sometimes when it’s at the bottom. In my list of the most common radicals, I have included variant forms such as these.

Back to index

2. Learning to read and write Chinese characters

In part one, we looked at how to understand the writing system and find the information you need, but that’s obviously not enough, you also need to learn characters. This part is about that, starting out with what characters to learn and how to find them, then moving on to learning characters, some things you can safely skip, and then finally advice specific to writing by hand, including if this is actually something you need to learn in a modern, digital age.

Back to index

2.1 Which Chinese characters and words should you learn?

This question is difficult to answer since it depends on your learning situation and how much Chinese you already know. Many formal courses also decide what characters students should learn, so if you’re enrolled in one of those, you don’t have much choice in the matter. If you do have a choice, though, here’s my advice for how to decide what to learn:

Which words you should learn and where to find them – If you’re a beginner, you need to learn around a hundred characters or so before you can read much of anything. The easiest way to do this is to rely on materials tailored to beginners in the form of textbooks. These rarely go through characters properly, but the earlier chapters in general tend to include the most important vocabulary. If you’re interested in my own attempt to create the ultimate path to the first 150 characters or so, check out the character course I built for Skritter. It’s not free, but it also took a long time to build. If you’re not a complete beginner, you should learn characters by reading, plus characters you need to be able to communicate about things you care about.

Should you learn Chinese vocabulary from lists? Generally speaking, no. Learning vocabulary from a list someone else has created looks like a good deal because it’s convenient. However, many students reduce learning Chinese to going through word lists they find online, or otherwise place an unwarranted amount of trust in the people who created these lists. So my advice from above still stands: most of the words you learn should come either from reading or from communicative needs.

Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them – There are exceptions to the above advice about not relying on lists, though, and this article goes through several types of lists and discusses how to use them to your advantage. Lists discussed include: frequency lists, textbook vocabulary lists, proficiency test lists, special purpose lists and thematic lists.

Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals – I’ve already said that learning the very basics is one of the few cases where relying on lists makes sense. This lists presents 100 common meaning components in characters, chosen from the 214 radicals (see the article itself for a discussion about the word “radical”). You can safely learn all the components on this list because they are all super useful!

The most common Chinese words, characters and components for language learners and teachers – If you want to find frequency information for components, characters or words, this article is for you. It’s a comprehensive overview of the various resources available, mostly online and freely available. This can be handy if you want to plug gaps in your vocabulary, or in other words, if you want to check if you’ve missed very high-frequency words that are significantly below your general level. Read more about this here: Mapping the terra incognita of Chinese vocabulary.

What important words are missing from HSK? Many people who ignore my advice above focus a lot on HSK, which is the most wide-spread proficiency test for Chinese. All lists are flawed, though, and the official test preparation lists that are so popular actually leave out a lot of words, or delay some very common ones until higher levels. This is an analysis of what important words are missing from the HSK lists. I also did the same analysis of the TOCFL lists, which is for the standard proficiency test used in Taiwan.

Overcoming the problem of having too many Chinese words to learn – All students face the problem of an ever-increase number of characters and words to learn. There is obviously no simple solution to this problem as we can’t change the number of words Chinese people use, and we therefore need to learn, but you can improve your situation by changing the way you learn words, by learning fewer words, or by adding them differently in case you’re using flashcards.

The Cthulhu bubble and studying Chinese – In your studies, you will encounter things that are very complex, don’t make a lot of sense or sometimes both. I strongly advise that you stay away from these things, especially as a beginner. You don’t have to sort out complex differences between how certain characters are used or understand the full process of how a given character came to be and evolved throughout history. This will contribute very little to your proficiency for the amount of time you invest. Don’t poke the monsters from beyond the bubble!

Back to index

2.2 How to learn Chinese characters

Now that you have some characters that you want to learn, how do you go about learning them? Below, I have separated the process into several steps, so this one is only about the initial learning, but as most of you probably already know, remembering and reviewing is where the real challenge is at (more about that later):

How to learn Chinese characters as a beginner – When you start learning Chinese, it’s hard to know where to begin. If you were given a few characters as homework or just want to learn them for some other reason, how do you go about it? In general, you want to understand what you’re doing, write the characters a few times to get a feel for it, but then space out repetitions to make learning more efficient.

Learn Chinese character meaning and pronunciation together – As we saw in part one, most characters look the way they do because of how they are pronounced. This means that you should learn meaning and pronunciation together, otherwise it’s unnecessarily hard to learn phonetic series like 晴, 情, 请, 清 and so on (they all share the phonetic component 青). I’m not a fan of approaches that ignore sound for this reason.

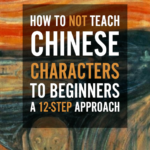

How to not teach Chinese characters to beginners: A 12-step approach – Even though it sounds like this article would be about teaching and things you should not do, it’s actually meant mostly for students and is a guide for what you should do as well (just reverse the “advice” given). You might be constrained by what your teacher thinks you ought to do, but if you’re forced to do too many things mentioned here, you should look for another teacher.

Back to index

2.3 Things you can safely ignore when learning Chinese characters

When you start learning Chinese, there are so many things you need to learn, some of which seem utterly useless. However, you can’t rely on your beginner knowledge to determine what to learn and what to skip. For example, I will argue later in this part of the article that stroke order is actually important, which seems odd to many beginners. Here are some thing you can certainly ignore, though, even if you learn to write by hand:

Should you learn the pronunciation of radicals? This is a tricky question, because the word “radical” is problematic here. Learning the pronunciation of components that are used to give the sound in other characters is very useful (I used the example of 青 above), but most characters you find on a typical list of radicals are not very common as phonetic components. Thus, the general answer is “no”, but also that it does depend on the character in question. Naturally, you need to learn how to pronounce characters that are used on their own! In my kickstart list mentioned above, I’ve indicated which pronunciations can be ignored by putting them in brackets.

Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters? No, not unless your focus is calligraphy. You will learn the names of the basic strokes later, but obsessing about what strokes and combinations of strokes are called is a waste of time. If your teacher writes a lot by hand in class and teaches the strokes naturally simply by saying them, fine, but I still don’t think that’s a wise use of classroom time. You do not need to be able to name the strokes in characters you learn, being able to write them is enough.

- How to talk ab

out Chinese characters in Chinese – So if you shouldn’t learn the pronunciation of all the radicals and shouldn’t learn the stroke names, how do you talk about Chinese characters in Chinese, then? After all, learning Chinese in Chinese is a good idea! Well, you gradually learn how native speakers do it and they certainly do not describe characters stroke by stroke. Instead, they use colloquial names of components and refer to parts of easier characters. This is not something you can safely ignore, I just include it here because I want to show how you can talk about Chinese characters in Chinese without violating the first two pieces of advice offered in this section!

- Should you learn how to categorise characters according to 六书/六書? No, this is another example of traditional teaching methods that make little sense today. This system is very old, very complicated and adds very little to your understanding of characters that functional components don’t do better and in a way that is also easier to learn. I mention this in How to not teach Chinese characters to beginners: A 12-step approach mentioned above as well.

Back to index

2.4 More about learning to write Chinese characters by hand

Unlike in most other languages, learning to write in Chinese is a separate skill that requires an awful lot of time to learn. As we have seen above, Chinese characters are not an alphabet, not even close to it, so they can’t be compared with the Arabic, Korean or Russian scripts.

While an alphabet can be easily maintained by reading and typing (you can probably spell almost all words you can type), this is not true in Chinese. It’s perfectly possible to be able to read well in Chinese and be able to type characters, but have only limited ability to write by hand. So, is it worth it, should you learn to write Chinese characters by hand? And if you do, how should you go about it?

Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand? – The short answer is that for most people, no, you don’t need to write by hand very often. Reading and typing is enough to function in a modern, largely digital society. However, learning to write can still be useful for beginners in order to deeply process characters and learn more about them, which will be useful. Learning to write by hand need not be an all-or-nothing decision either, in fact the best approach is probably to learn to write the most common characters, but be satisfied with reading and typing for the rest.

Is it necessary to learn the stroke order of Chinese characters? Yes, you should learn stroke order. Native speakers write the way they do for a reason: it’s more practical and efficient. Your characters will look better, it will be easier to make sense of other people’s handwriting, and using handwriting input will be easier. Finally, there’s no good alternative to correct stroke order, because making up your own stroke order creates other problems.

All the resources you need to learn and teach Chinese stroke order – This includes apps, websites, printable worksheets, where to find information about official standards for stroke order and so on. Many dictionaries offer stroke order animation and some apps like Skritter has it built into the very core of the learning process.

How to improve your Chinese handwriting – As argued above, learning to write by hand is a separate skill in Chinese, and this article takes a closer look at what is required of you to be able to do it well, along with problems you will encounter along the way. The process is separated into intent (what you want to write) and execution (what you actually write). Depending on which you struggle with, the remedies will be different! I expanded on this specific topic here as well: What you intend to write is more important than the character you actually write.

Handwriting Chinese characters: The minimum requirements – This article goes through the nitty-gritty of writing characters by hand, the kind of things that your teacher might mention briefly now and then, but isn’t typically taught at all these days. Note that while the title says “minimum”, this goes beyond what most second language learners need.

36 samples of Chinese handwriting from students and native speakers – While not being advice about how to write by hand, this article might nevertheless be interesting because it shows you how other people write Chinese characters by hand, which is not always easy to find if you’re learning Chinese in your home country. More importantly, they write exactly the same text, so you can compare! Samples include both native speakers and second language learners on various levels.

Back to index

3 Reviewing and remembering Chinese characters

I’ve learnt characters for more than a decade, and as all long-time learners can testify, Chinese character knowledge is something you have to use constantly or you will forget what you have learnt. This is particularly true for handwriting, but this part is not limited to handwriting in particular, but rather the general goal of remembering what we learn.

Back to index

3.1 How to not forget the Chinese characters you’ve learnt

The first and most obvious thing to say is that you have to review characters to remember them. This can be done in many ways, such as reading a lot, typing, using apps to review and so on, but if you don’t review, you will forget most of what you have learnt.

An introduction to extensive reading for Chinese learners – Reading has many benefits for your learning in general, but it’s definitely the best way to review characters and vocabulary in general. If you read extensively, i.e. where you understand almost everything you read, you can also learn new characters and words this way!

Three ways to improve the way you review Chinese characters – Most students don’t review characters very efficiently, so this article goes through there important ways to improve: 1) understand what you’re doing, 2) spread out your reviews (see spaced repetition below), and 3) make sure your review method is valid (meaning that what you learn actually is transferable to the area you want to use it in).

Spaced repetition software and why you should use it – Reading involves passive recognition, rather than active recall. If you want to get most out of every minute you spend on vocabulary review, you should check out spaced repetition software, or SRS for short. These programs use flashcards to combine active recall with efficient scheduling of reviews, which has been shown to have very large benefits on retention. You don’t have to use SRS and it has its limits, but it is a very powerful way of remembering everything you’ve learnt. You can of course use the spacing effect without using flashcards!

Skritter review: Boosting your Chinese character learning – My favourite app for learning Chinese characters and words, particularly geared towards deep processing and writing by hand on screen. I’ve used this app for almost a decade now and I still try to use it every day. Requires a subscription, but also offers som content completely for free.

Anki, the best of spaced repetition software – This app is for students who like full control and to be able to tinker with their spaced repetition experience. Anki is not designed specifically for Chinese, but there is a very useful Chinese support plug-in that adds a lot of useful features. Anki is free on all platforms except iOS.

Reading is a lot like spaced repetition, only better – Let’s remember that there’s no magic involved in SRS; it’s just a clever way of scheduling flashcard reviews. You can get the same effect by reading a lot, which is what this article compares. While flashcards might be more efficient for certain things (such as handwriting Chinese characters), reading has lots of other benefits that flashcards don’t have.

You can’t learn Chinese characters by rote – Technically, you can learn characters by roe, but it takes so much time that it’s impossible for most second language learners. While you can brute-force characters into your long-term memory, unless you understand what you’re doing and are able to form meaningful connections between characters and other knowledge stored in your brain, it will be very, very hard to remember in the long run.

Learning to write Chinese characters through communication – Both written and spoken language exist for the purpose of communication, yet few people learn characters in a communicative setting. By relying on handwritten input on your phone (among other things), you can integrate writing characters into a meaningful context and your learning is driven by your own desire to express yourself, rather than what happens to be in the next chapter of your textbook.

7 ways of learning to write Chinese characters – When choosing how to review characters, take your long-term goals for learning Chinese into account. You need to make sure that the way you practise will actually get you to your goal. This article goes through seven ways of reviewing characters, discussing the pros and cons of each: writing on paper, writing with your finger, writing in your mind, writing on screen without feedback, writing on screen with feedback, no writing just looking, and finally, only reading and typing

Back to index

3.2 Mnemonics and improving your memory

Memory is often seen as something fixed, so either you’re born with a good one or you’re stuck with bad memory for the rest of your life. But this is not true. Our ability to remember things can be trained, both in the sense that we get better at it the more we do it, but also in the sense that there are techniques and tricks that can vastly improve your ability to remember.

Some of these tricks have been known since ancient times, others have been discovered through research in cognitive science (a nice summary can be found here). Some techniques are hard to learn, but others are actually very easy!

Remembering is a skill you can learn – The most important lesson of all is that you can train your memory. This has been testified by many different people over the years, but my favourite of these come from Joshua Foer, known to most through his TED talk and his book Moonwalking with Einstein. In the linked article, I explain the basics and we try them out with a simple experiment.

Using memory aids and mnemonics to make Chinese easier – There are many techniques available and they can all be used to learn Chinese characters. This includes memory palaces, the loci method, the journey method, and, the method I use most often, simply associating meaningful concepts and images in ways that stand out in a way that makes them easy to remember later.

How to create mnemonics for general or abstract character components – In general, it’s easier to remember concrete, meaningful things that can be related to what you already know in a clear way. Hence, it’s easier to remember the word “Baker” if you think of an actual baker, compared to if you think of it as a surname. Some things we want to learn are abstract or hard to pin down, so what to do? Make them concrete, because even made-up meaning is better than no meaning.

Are mnemonics too slow for Chinese learners? One common complaint about using mnemonics for language learning is that they are too slow. However, this criticism misses the point: the role of mnemonics is as a stepping stone from not knowing to knowing. Recalling, even if slowly, is much better than not recalling. Gradually, mnemonics can be cast aside, except for handwriting characters where they remain useful even for very advanced learners.

Don’t use mnemonics for everything – When introduced to the fantastic world of memory hacking and mnemonics, some people go all-in and want to use them to learn everything. However, this is not really necessary and will create a lot of extra work. Chinese is still a language, not a list of abstract things to memorise. Use mnemonics when you need to, not as the default solution to remember things you’d probably remember without them.

Back to index

3.3 Practical considerations: Where and how to review

Learning Chinese characters does not take place in a vacuum, so we also need to put learning into the general context of our daily lives.

Back to index

3.4 Beyond beginner: Character learning in the long term

Finally, I’d like to offer some advice for those of you who have been learning for a while now.

The real challenge with learning Chinese characters – Beginners think that learning new characters is the hardest part of learning to read and write characters, but more advanced students know that keeping all of them apart and knowing when to use which is where the real challenge is at. There are many things you can do about this, some of which we covered above, but also…

Dealing with Chinese characters you keep mixing up – The key to sorting out characters you’re mixing up is to trace your errors and figure out why you’re confusing them. It’s often the case that you have overlooked something, misunderstood a key piece of information or that the problem is easily solvable just by looking at the two characters next to each other. Often, we are subconsciously confused without realising it!

7 mistakes I made when writing Chinese characters and what I learnt from them – To show you the above-mentioned error tracing in action, I wrote this article where I go through seven mistakes I’ve made with my own character writing recently, tracing each error to the source.

Chinese characters that share the same components but are still different – This is particularly tricky case of mixing characters up. Normally, I don’t encode the order of the components when creating mnemonics because only one way of writing the character looks even vaguely right. But this doesn’t work if the characters have exactly the same components!

A minimum-effort approach to writing Chinese characters by hand – Finally, let’s look at the minimum-effort approach to maintaining the ability to write by hand. This is for those who you who, like me, want to be able to write by hand, but are too busy to spend more time than absolutely necessary. The approach includes for components: reading, typing, spaced repetition and communicative handwriting.

Back to index

Conclusion

The goal of this article is to provide a handy guide for all matters related to learning Chinese characters. There are probably things I have omitted or forgotten to mention, so if you have a question that is not covered here, please leave a comment below!

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2015, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in February, 2021.

Tips and tricks for how to learn Chinese directly in your inbox

I’ve been learning and teaching Chinese for more than a decade. My goal is to help you find a way of learning that works for you. Sign up to my newsletter for a 7-day crash course in how to learn, as well as weekly ideas for how to improve your learning!

Welcome to the first lesson of our Free Beginner’s Chinese Series. By the end of this first lesson you will have learned a basic dialogue in Chinese.

This beginner’ys series includes:

- Chinese audio for all words

- Character animations so you can learn how to draw the characters

- Further reading to expand you knowledge

The best way to learn a language is to dive in and start using it, so there is:

- No complex language theory, but we’ll link to more information if you’re interested

- No need to learn to write Chinese if you don’t want to

- No need to spend hours learning pronunciation, well introduce pronunciation as we progress.

How to navigate these lessons

All Chinese words in this lesson are accompanied with lesson audio and animations showing how a character is drawn, for example the word for “hello” in Chinese is 你好

- Simply click on the blue speaker symbol next to any Chinese words to listen to the characters spoken

- Click on the red pencil icon next to any Chinese words to see an animation of how the characters are written. As a beginner, don’t fee obliged to learn how to write Chinese characters, however this is useful if you choose to do so.

How to say “hello” in Chinese

The most common way to say “hello” in Chinese is “ni hao”, which is written in Chinese as 你好. Click on the icon to listen to the pronunciation.

你好

ni hao

Hello

Congratulations! You have learned your first word in Chinese.

Note that you can’t use the western alphabet to write Chinese, so while “ni hao” will help you say the word, it is not the written form of Chinese. To write “hello” you must write it with the Chinese characters 你好.

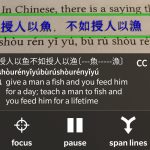

The standard way of writing Chinese with the western alphabet is called “Hanyu Pinyin” or just “Pinyin” for short. You can read more about Hanyu Pinyin in our post what is Chinese Hanyu Pinyin. The pronunciation of Chinese written in Pinyin isn’t exactly the same as English, but close enough that a learner who is unfamiliar with Chinese can use it to pronounce the words with a basic level accuracy.

In this lesson we will normally place the Pinyin pronunciation of characters and words in brackets behind the Chinese characters, for example:

“hello” 你好 (ni hao)

As we’re only getting started, and for the sake of simplicity, we are deliberately going to ignore Chinese pronunciation tones and Pinyin accent marks. We’re also going to skip discussing how to write characters. These concepts will be introduced soon, but for now, let’s just start learning some basic Chinese.

Chinese words are made up of one or more Characters

You’ll notice that “hello” in Chinese is made up of two characters. Together these characters mean “hello”, however individually the characters also have meaning:

- “ni” 你 means “you”

- “hao” 好 means “good”

So when literally translated character-by-character “ni hao” means “you good”, but translates to “hello”. If you think about it “good day” and “are you well?” in English are similar and a reasonable way to greet someone.

Although Chinese characters have meaning by themselves, Chinese words are typically made up of between one and four Chinese characters, with two character words being the most common. Check out our post are Chinese characters words?

Your first three words in Chinese

Great progress, you’ve now already learned your first three words in Chinese:

- “ni” 你 means “you”

- “hao” 好 means “good”

- “ni hao” 你好 means “hello”

We are going to expand on our vocabulary and put together a basic sentence.

How to ask a question in Chinese

To ask a question where you expect a “yes” or “no” answer, the character 吗 (ma) is used, which turns a statement into a question. A question mark is always placed after the 吗 (ma) character.

Let’s see how this is used:

好吗?

Okay?

How are you?

We have just learnt that 好 (hao) means “good”. By adding the “question” character 吗 (ma), we’ve turned this into a question and are literally asking “good?”, however a better translation is “okay?”

The question character 吗 (ma) is referred to as a question “particle”.

A Chinese particle is a character that has special grammatical meaning. The most common Chinese particle character is 吗 (ma), which turns a statement into a yes/no question. There are less than ten Chinese particles, so most characters are not particles.

Your first conversation in Chinese

Let’s try a short conversation by extending what we’ve learnt so far:

好吗?

hao ma?

Okay?

很好。

hen hao.

Very good

The character 很 (hen) means “very”. By pairing this with “good” 好 (hao) we are saying “very good” 很好 (hen hao).

You may have noticed that a Chinese full stop “。” is a little circle rather than a dot and takes up a full character width on your computer. Most chinese punctuation is used in the same way as English, but tends to look slightly different. If you’d like to know more about punctuation check out our post on Does Chinese use punctuation?

How to say “you” and “me” in Chinese

The Chinese words for “you” and “me” are as follows:

| English | Chinese | Pinyin Pronunciation |

| me | 我 | wo |

| you | 你 | ni |

We’ve already covered “you” 你 (ni) when we introduced 你好 (ni hao)

Let’s modify our simple dialogue to add “you” and “me”:

你好吗?

ni hao ma?

How are you?

我很好。

wo hen hao.

I’m very good/well.

Here we have simply added the 你 (ni) to turn “okay?” 好吗? (hao ma) into ” you okay?” 你好吗? (ni hao ma). The normal and preferable translation is this is “how are you”, which is how we’ve translated it.

By starting with the “I” 我 (wo) character, we’ve modified the reply by from simply “very good” 很好 (hen hao) to “I (am) very good/well” 我很好 (wo hen hao).

The difference between 你好 and 你好吗

Adding the question particle (character) 吗 (ma) turns the statement “you well” 你好 (ni hao) into a question “(are) you well?” (ni hao ma).

A few points:

- Both 你好 (ni hao) and 你好吗? (ni hao ma) are acceptable ways of saying “hello” in Chinese.

- 你好 (ni hao) is a statement literally meaning “you well/good”, a way of wishing someone well, however is the equivalent of saying “hello”

- 你好吗? (ni hao ma) is a question literally asking “(are) you well?”, but is the equivalent of asking “how are you?”

How to say “and you?” in Chinese

In our dialogue, if the speaker wanted to say “how about you?”, they would simply ask “you?” 你呢 (ne). Here we are using another Chinese particle 呢 (ne).

呢 (ne) is a Chinese character particle, which means it is a special character that carries a grammatical meaning. 呢 (ne) means that the previously asked question should be applied to the proceeding word. For example:

– 你呢? (ni ne) means “and you?”

– 我呢? (wo ne) means “and me?”

In this case 你呢 (ne) means that the speaker is asking the same question back to the other person, a bit like saying “and you?” Let’s look at the dialogue again:

你好吗?

ni hao ma?

How are you?

我很好。

wo hen hao.

I’m very good/well.

你呢?

ni ne?

And you?

很好。

hen hao.

Very good.

How to say “goodbye” in Chinese

The Chinese word for “goodbye” is 再见 (zaijian). Broken down, these character mean:

- “again” 再 (zai)

- “meet” or “to see” 见 (jian)

Thus “goodbye” 再见 (zaijian) can be literally translated as “again meet”, or more eloquently, “see (you) again”. Many Chinese words can be literally translated in this way to understand the meeting. It is worth noting that most Chinese language resources do not encourage breaking down words into their component characters, however, it can be useful for understanding how words are formed and get their meaning.

Let’s complete our simple dialogue:

你好吗?

ni hao ma?

How are you?

我很好。

wo hen hao.

I’m very good/well.

ni ne?

And you?

很好。

hen hao.

Very good.

再见

zaijian

Goodbye.

再见

zaijian

Goodbye.

There is no special response to goodbye, you can simply respond in the same way “goodbye” 再见 (zaijian).

Review

This is the key vocabulary and phrases learned in this lesson.

Lesson key vocabulary

| English | Chinese | Pronunciation (Pinyin) |

| hello | 你好 | ni hao |

| you | 你 | ni |

| very | 很 | hen hao |

| goodbye | 好 | hao |

| me | 我 | wo hen hao |

| goodbye | 再见 | zaijian |

| <“and…?” particle> | 吗 | ma |

| <yes/no question particle> | 呢 | ne |

Lesson key phrases

| English | Chinese | Pronunciation (Pinyin) |

| hello | 你好 | ni hao |

| very well | 很好 | hen hao |

| how are you? | 你好吗 | ni hao ma |

| I’m very well | 我很好 | wo hen hao |

| and you? | 你呢 | ni ne |

Wrapping it up

In this short lesson you have made your first step towards learning Chinese and have learned a simple dialogue, including how to say “hello”, “goodbye” and ask how someone is in Chinese. Take a breather here before proceeding to the next lesson and spend some time reviewing the vocabulary and phrases you have learned so far.

Here is a summary of the key points from this lesson:

- The method of Romanising Chinese pronunciation is called Pinyin, which allows you to write the pronunciation of words and characters with the standard Western alphabet (A-Z).

- Chinese words are made of one or more characters

- 吗 is a special question character, known as a “particle”

- 呢 is the “and you” particle.

- Plus a lot of very useful vocabulary, see the vocabulary and phrase list above.

Check out Lesson 2 where we introduce Chinese Tones and how to introduce yourself.

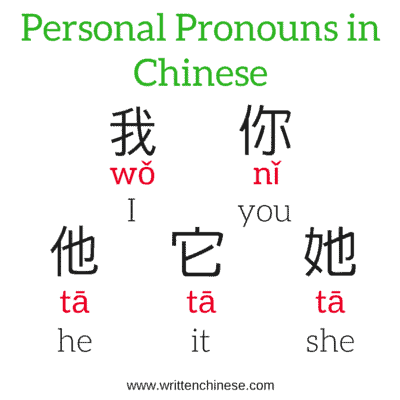

Personal Pronouns in Chinese 人称代词 (rén chēng dài cí)

One of the first words you probably need to learn is ‘I’ 我 (wǒ). Although in Chinese, you can often get away with missing off the 我 (wǒ) ‘I’ in spoken Chinese, it is important to use it within written Chinese.

The word for ‘you’ is 你 (nǐ) and can also be used in its formal version 您 (nín), which is used to show respect to elders or superiors.

Do you know that in spoken Chinese, the words for he she and it are all the same? In a conversation with someone, it’s easy to ask the other person for clarification, but what happens in written Chinese? Luckily, personal pronouns in the written language of Mandarin Chinese have different characters.

他 (tā) – he

她 (tā) – she

它 (tā) – it

If you know a little about radicals in Chinese, you might know that usually, the meaning of the character is on the left, and the pronunciation is on the right side. Both the characters for he and she have the same radical to suggest the way it is spoken.

The left side of the character for he 他 (tā) has the person radical 人/ 亻 (rén), suggesting male origins. The character for ‘she’ 她 (tā), has the female radical 女 (nǚ) to the left of it, which indicates it is female.

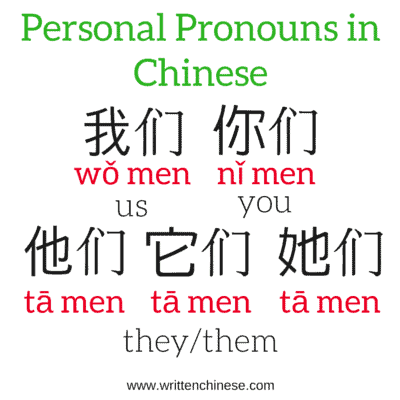

Plurals

In order to pluralize personal pronouns in Chinese and create ‘we’, ‘us’ ‘they’ or ‘them’, you simply add 们 (men).

我们 (wǒ men) – us/we

你们 (nǐ men) – you (plural)

他们 (tā men) – they/them

她们 (tā men) – they/them

它们 (tā men) – they/them

他们去外面吃饭。(tā men qù wài mian chī fàn.) – They went out to eat.

Possessive 物主代词 (wù zhǔ dài cí)

Technically, the Chinese language does not have possessive pronouns, but it classed as a rule of the 的 (de) particle.

To make a pronoun ‘possessive’, you add the 的 (de) particle. Although the 的 (de) particle has many uses, at the moment it is enough to know that it makes pronouns possessive.

我的 (wǒ de) – mine

你的/您的 (nǐ de/nín de) – yours

他的 (tā de) – his

她的 (tā de) – hers

If you want to say ‘my cup’, it would look like this:

我的杯子。(wǒ de bēi zi)

Me (s) cup.

In the case of alienable possession (if the object is close to the subject like a family member), the 的 (de) particle can be removed.

我妈。(wǒ mā) My mother.

Finally, to say ours, theirs or yours add the 的 (de) particle to the plural pronoun.

我们的 (wǒ men de) – ours

你们的 (nǐ men de) – yours

他们的 (tā men de) – theirs

她们的 (tā men de) – theirs

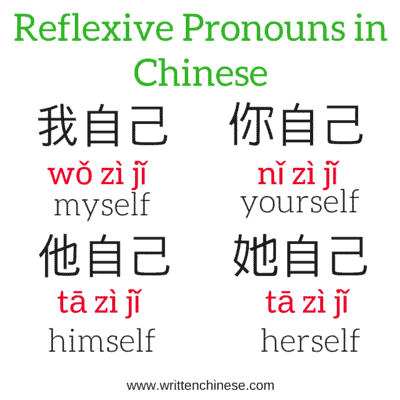

Reflexive Pronouns

To refer to the ‘self’ in Chinese, we add the bigram 自己 (zì jǐ) to a personal pronoun:

我自己 (wǒ zì jǐ) – myself

你自己 (nǐ zì jǐ) – yourself

他自己 (tā zì jǐ) – himself

她自己 (tā zì jǐ) – herself

我们自己 (wǒ men zì jǐ) – ourselves

请用一句话介绍你自己。(qǐng yòng yī jù huà jiè shào nǐ zì jǐ.) Please introduce yourself in one sentence.

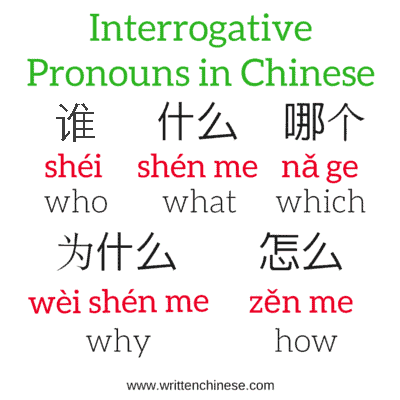

Interrogative Pronouns 疑问代词 (yí wèn dài cí)

Interrogative pronouns are ‘question’ words that express an enquiry.

谁 (shéi) – Who

他是谁?(tā shì shéi) Who is he?

什么 (shén me) – What

这是什么? (zhè shì shén me) What is this?

哪个 (nǎ ge) – Which

这两个玩具,你喜欢哪一个?(zhè liǎng gè wán jù, nǐ xǐ huan nǎ yī gè)

Which of these two toys do you prefer?

为什么 (wèi shén me) – Why

这么晚了,为什么你还不回家?(zhè me wǎn le, wèi shén me nǐ hái bù huí jiā.)

It’s late. Why don’t you go home?

怎么 (zěn me) – How

这个问题怎么解决?(zhè ge wèn tí zěn me jiě jué)

How do we solve this problem?

什么时候 (shén me shí hou) – When

你什么时候来中国? (nǐ shén me shí hou lái zhōng guó.)

When will you come to China?

<p< p=””>

哪里 (nǎ lǐ) – Where

我忘记把钥匙放哪里了。(wǒ wàng jì bǎ yào shi fàng nǎ lǐ le)

I have forgotten where I put my keys.

几 (jǐ) How much/How many

我们几点见面?(wǒ men jǐ diǎn jiàn miàn)

When shall we meet?

多 (duō) – Many/Much

你花了多长时间写作业?(nǐ huā le duō cháng shí jiān xiě zuò yè.)

How much time did you spend on your homework?

Rules for Interrogative Pronouns

There are some rules regarding interrogative pronouns. Here are some examples of when to use these pronouns:

For people or things use: 谁 (shéi) – who, 什么 (shén me) – what, 哪 (nǎ) which

For place or location use: 哪儿 (nǎr) or 哪里 (nǎ lǐ)

For time use: 哪会儿 (nǎ huì er) or 多会儿 (duō huì er)

For status, actions, method or property use: 怎么 (zěn me) or 怎么样 (zěn me yàng)

For quantity use: 多 (duō), 多少 (duō shao) or 几 (jǐ).

Generally, the usage of 几 (jǐ), is almost the same as 多少 (duō shao), so they can replace each other. However, 多 (duō) can also be used to ask for levels or amounts such as 多长 (duō cháng) meaning ‘how long’ or 多大 (duō dà) meaning ‘how large’, whereas 几 (jǐ) can not be used in this way.

When interrogative pronouns are used in the way that relative pronouns are used in English, then there should be always be an adverb such as 都 (dōu) or 也 (yě). These characters are interchangeable as they have almost the same meaning. Sometimes they will be used with words such as 不管 (bù guǎn) or 无论 (wú lùn) to create emphasis.

If 都 (dōu) or 也 (yě) are removed from the sentences below, they no longer have the same meaning. The first example shows the sentence with 都 (dōu) or 也 (yě), the second shows it without.

谁也不知道他在哪儿了。(shéi yě bù zhī dao tā zài nǎr le) – No one knows where he is.

≠ 谁不知道他在哪儿。 Every knows where he is (don’t they?)

你什么都不懂。(nǐ shén me dōu bù dǒng) – You know nothing.

≠ 你什么不懂。 You know everything (don’t you?)

Take a look at the Chinese sentence type blog post to find out more about this interrogative sentence pattern.

不管怎么解释,他都不明白。(bù guǎn zěn me jiě shì, tā dōu bù míng bai.) – No matter how it has been explained, he is unable to understand.

Indefinite Pronouns

Since there are no clear cut way to translate English indefinite pronouns into their Chinese equivalents, the words we know in the English language such as ‘anything’ and ‘something’ etc are not indefinite pronouns in Chinese. In the English language, indefinite pronouns are words that include some-, any-, every- etc