When teaching a foreign language, one of the key things that we stumble upon is the introduction of new lexical patterns, new phrases and idiomatic expressions. Ensuring constant vocabulary enrichment with the learners is the key principle to achieve language fluency and coherence. Hence, helping the learners to acquire and grow their word stock in a stress free environment and have fun at the same time is a challenge all of us — educators deal with.

There are different theories and practices about what the best way of vocabulary presentation is. All of them come not merely from theory but from practice as well. Hence, there is no definite truth here. All we need to know is that if it works for the learner then WELL DONE!

Existing Theories

CELTA course gives us a very nice and structured way of vocabulary presentation — meaning, pronunciation, form (MPF). This is explained in the following way — teaching meaning is the first obligatory thing, as the learners should first understand what the word means and then deal with the form and polish its pronunciation. Pronunciation comes next as the word should be articulated properly to be understood by the interlocutors, and the form is the last one in the list, as seeing the word written might hijack its pronunciation, considering the students are not well versed in word stress and the pronunciation of certain letter combinations. This order, however, can be varied according to the language level of the learners, the material presented and the aim of the task. For instance, when working with B2 and higher level of learners we can have the presentation stages in the following order: form, pronunciation, meaning. At this level of language comprehension learners are less likely to make pronunciation mistakes and we can actually show the form and reinstate the pronunciation without working on the meaning first. This technique however, is risky with low level learners, as they might pronounce the word incorrectly or get lost in the form, thus, prolonging the assimilation stage.

Another theory suggests that having a context for vocabulary presentation is always a must, as a lesson should not be divided into different sections like vocabulary, grammar, listening, reading, writing, but it rather should be a unity where all language skill are intertwined with each other. This, being true, does not negate the fact that sometimes we hold mere vocabulary sessions where having all the aspects included is not a must.

As we know, there are different types of learners — visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic. Though it is impossible to meet everyone’s needs all the time, we are trying to make sure each session contains material for each type of learner. It is worth mentioning here, that learners don’t have to be of a specific type, but can have certain aspects of each with one dominant type.

Let’s have a closer look at some practical points and choose the ones that will work well with the type of learners we are currently dealing with.

- Realia

Using realia in class when possible increases the chance of students remembering the targeted phrases with more ease and more vividly. This works better with lower level vocabulary where we are working with non abstract notions. Topics like ‘food, everyday objects, etc.’ go well with this method. We can go further and get more creative by using realia to revise/recycle vocabulary by asking the students to name the objects, or bring the objects they want to know how to call in English to class, and mingle. This can get very noisy, fun and educational.

- Picture

In case realia is hard to organize, pictures are always there to help thanks to the wide variety of Internet resources available nowadays. What I love pulling off during classes is trying to elicit an abstract phrase/idiom through a situational picture. It gives the students a chance to think longer, use their creativity and result in very interesting phrases.Below there is one of the idiomatic phrases I introduced during the class and students still remember it — Don’t cry over spilt milk.

First, the students brainstormed different phrases by looking at the picture. The only thing they knew was that it represents an idiomatic expression in English and they had to try to guess it. After the students mentioned the key words the phrase was revealed to them. After that, they started working with the meaning and finding synonymous idiomatic expressions in their L1.

Similarly, posters and flashcards can be very useful when working with visual learners. We can have a set of words to introduce with picture flash cards (either printed or using slides).

- Guessing the word from the context

This has been a great vocabulary introduction practice for quite a long time with different age groups, levels of target language comprehension and interests. One of the ways is to present a text to the students where the context leads to the understanding of the key word. Most textbooks use this technique. Another way, is to show the target word in different sentences to enable the students grasp the meaning. Checking whether the students have actually understood the meaning of the word or not is quite easy, by either asking them to make their own sentences using the target word or elicit the translation of the word if everyone shares the same L1.

For example:

“Audi is a luxurious car.”

“Gucci is a more luxurious brand than Guess.”

“They entered the elegant, newly decorated, and luxurious dining room.”

This technique works nice with reading/writing type of learners. It can also work with the auditory type if we decide to read the sentences out loud instead of presenting the learners with the written one.

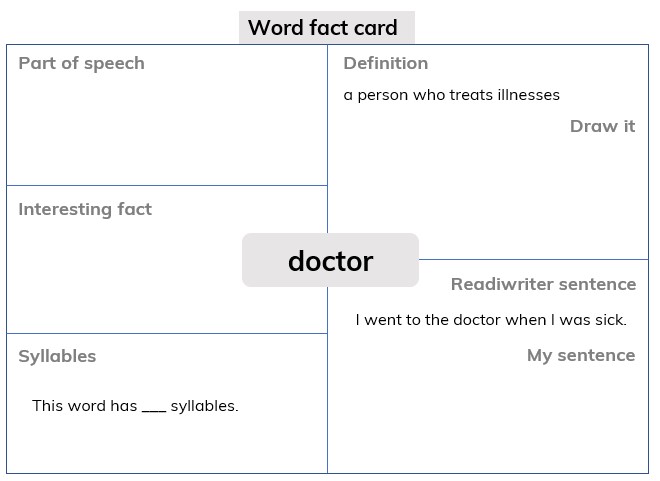

- Definitions

This is another well-versed way of introducing new vocabulary. One challenge that we, teachers, might have with this, is making sure that the definition is actually comprehensible. Sometimes dictionaries provide definitions that include a lot of unknown words, hence confusing the learners even more. So, it is our job to choose/adapt the definitions according to the level of the learners to achieve a successful result.

An example of this I have come across when teaching B1 level students was the phrase “to cut down on something”:

To cut down on something — to start using something less extensive than previously

I adapted it like this — to start using something less than before

This technique can be quite nice for both reading/writing and auditory type of the learner depending on the way of its presentation.

- Personalization

It is a fact that learners remember things better when we give them strong associations. This can be examples from the real world around us (politics, celebrities, etc.), as well as personalized examples on students or the teacher.

Let’s say, you want to teach the phrase “to get on well with someone”. Something like this can definitely work:

“My sister and I understand each other very easily. We have the same interests, the same hobbies, the same opinion about different things and we never fight. We get on well with each other.”

We can either use the target phrase like it was in the example and ask the students to guess the meaning, or leave the space blank and let the students guess the phrase itself. The second way works better in revision sessions though.

- Find the word

This one is my personal favourite.

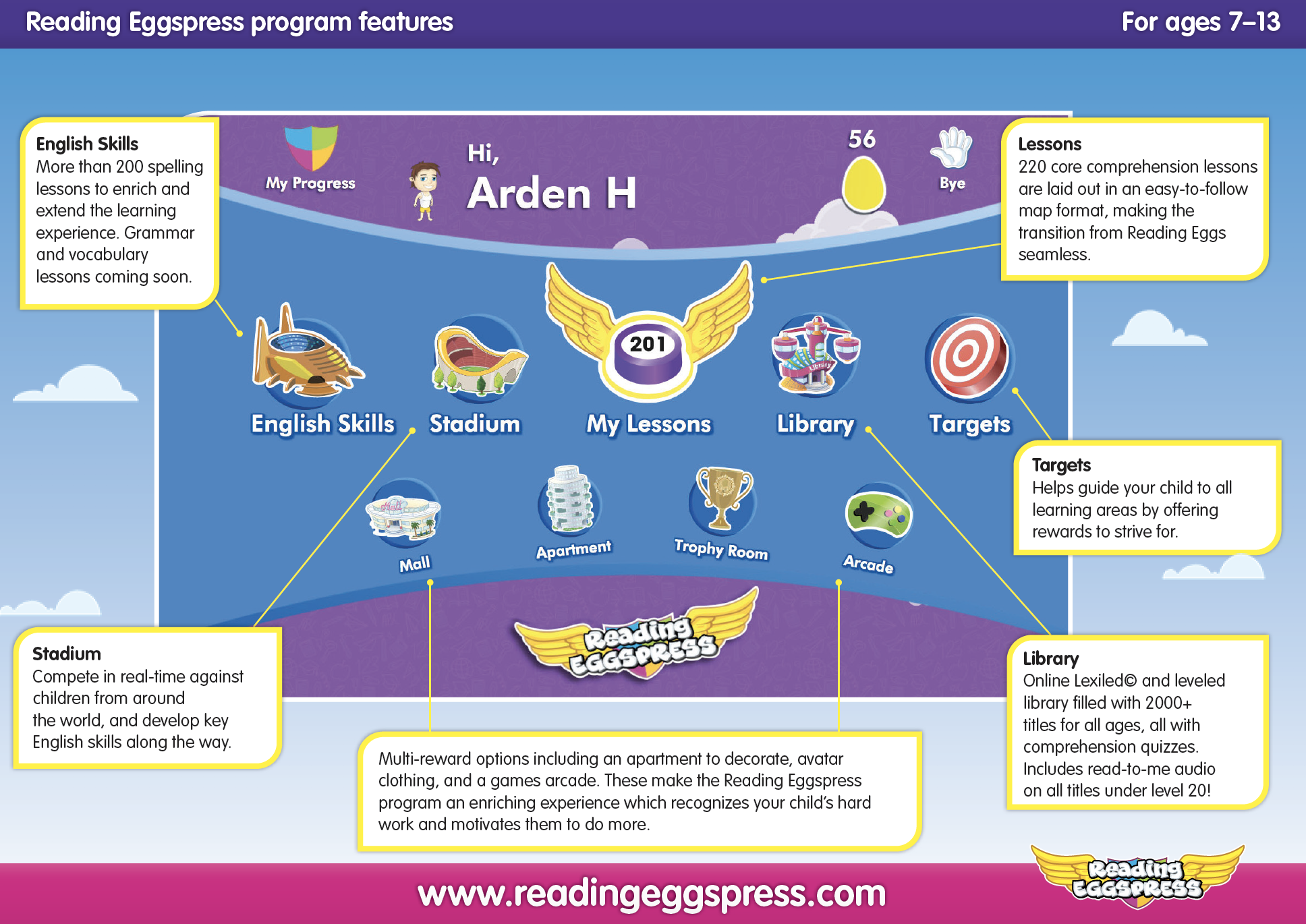

Let’s say we are going to introduce 4 words: reliable, arrogant, showy, trustworthy

We can create a grid with the words, cut them in half, and give to the students:

The students should try to find the correct beginnings and endings for the words knowing that there are only 4 words to compile.

This can be a little time consuming, but it gives the students a chance to compile the words on their own, hence, they work with word structure, exercise their background knowledge and having so much exposure to the target words enables them to remember them better.

- Graphs

This approach is a very nice way to help assimilate the target word/phrase easier and in a full package. Four categories are used to help the learner grasp the meaning of the word and its usage: synonym, antonym, example, non-example. The graph below represents it more clearly.

This is a full and exhaustive way of dealing with the word at hand. To make it more challenging, we can upgrade the students’ language and introduce the part of speech differences of the word as well.

Let’s say we are teaching the word ‘interesting’. The rank will go as follows

Noun — an interest (n.)

Verb — to interest (v.)

Adjective — interesting, interested (adj.)

Adverb — Interestingly (adv.)

At the same time, context and/or example sentences can be provided with these 4 words which will result in the students’ assimilating 4 words instead of 1.

- Ranking

This is another way of introducing sets of words. As we know, learning different shades of meaning is an effective way to enrich the students word-stock faster and help them understand the usage of each in a respective context. Though ranking is known to be a toll for vocabulary practice, it can also be used to challenge the students background knowledge and language feeling in general. Of course, here the level of the students is crucial, as we cannot demand A1 or A2 levels to have the that linguistic feeling.

Ranks work well with adjectives and adverbs quite nicely. Adverbs, however, can also be introduced with percentages as it is done in most textbooks (always — 100%, never — 0%).

Always-often-sometimes-occasionally-seldom/hardly ever-never

Happy-excited-delighted-ecstatic

- Classification

This is another way of introducing new language in Test-Teach-Test format. It can be as simple as asking the learners to classify the target words into respective columns (means of transport, food, clothes, etc.), to parts of speech.

This also requires a lot of exposure to the language where the students have a chance to look at the target words/phrases more than once, try to pronounce them correctly, use their background knowledge, their guy feeling. As mentioned, things which people achieve themselves and are not handed, stick in the long-term memory.

- Translation

Foreign language specialists, trainers, educators, instructors will agree that translation is not the best idea when working with a group of people trying to learn a target language. However, to me, it is not such a bad thing after all. Quite the opposite, when used moderately and to the point, it can be quite helpful in the teaching process.

Sometimes there are ideas and abstract notions which are hard to explain in a target language and near to impossible when dealing with low level learners. Here the L1 comes to help.

This being true, we should not forget, that translation is to be resorted only after we have tried all the possible ways to convey the meaning of the word and failed. It can be used to clarify the understanding rather than reveal it from the beginning.

Anyways, in general, it’s not a shame to have a good dictionary at hand and check the meaning of the words we, as teachers might not have come across yet. It creates a healthy learning environment if it’s done moderately and once again highlights the truth that learning is a lifelong process.

Alternatively, we can tell the students that we will check the word and get back to them. We should not be surprised that the students will take our word for it and wait for the clarification next class. So, it is important to keep our promises and get back to the students to answer their questions.

All of these said, it is worth pointing out that not all the techniques and methods will work with all types of groups and learners. Things that should be taken into account are age of the learners, interests, previous exposure to the language, background knowledge in general (this being a powerful tool when teaching in general, not just a language), their mother tongue, type of the learner and the means available at hand (technology, resources).

Let’s get creative and share more tools and techniques to facilitate vocabulary introduction. Looking forward to your comments!

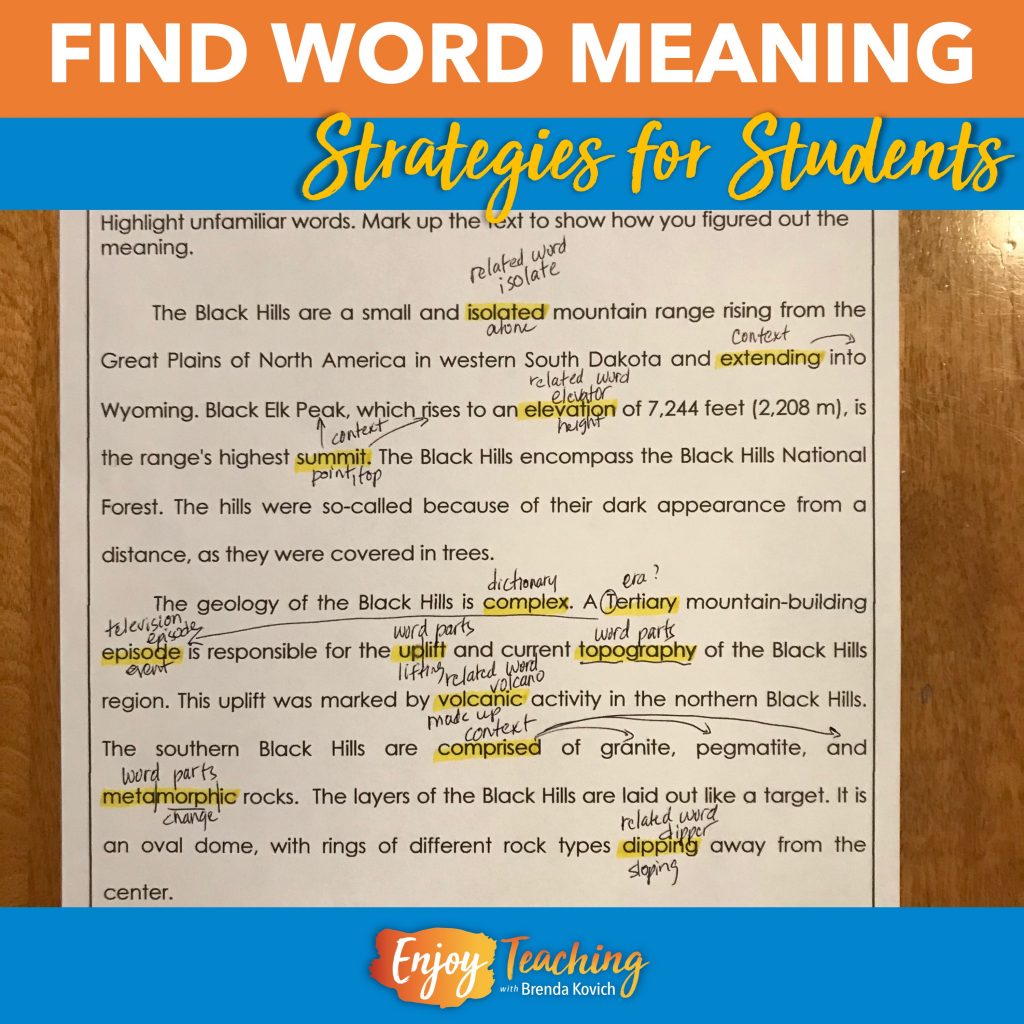

When kids find word meaning in a text, comprehension improves. How can you facilitate this? First, use direct instruction to teach kids the vocabulary strategies they need. Second, ask them to practice with targeted activities. Third, provide lots of mixed practice. Finally, ask students to use newfound metacognitive skills on texts they read every day.

Ms. Sneed Wants Students to Find Word Meaning

Our favorite fourth grade teacher, Ms. Sneed, sat with her teaching partner, Mr. Frank. “You know,” she said, “my kids are struggling with unknown words in the text.”

“Same here. What can we do?”

“After a little research, I found four strategies.” She pulled her laptop around so Mr. Frank could see. “In this word meaning unit, the teacher explains each strategy. Then the kids practice it. They use:

- Words set off by commas or parentheses: The Grand Canyon, a valley carved by the Colorado River, is located in Arizona.

- Context clues: For thousands of years, Native Americans have inhabited the Grand Canyon. They built their homes in the canyon.

- Word parts: Geologists believe that the Grand Canyon began to form more than 17 million years ago.

- Related words: The Pueblo people made pilgrimages to the Grand Canyon.“

“I like this,” said Mr. Frank. “It’s metacognitive. Students must think about their own thinking.”

“Yep.” Ms. Sneed nodded thoughtfully. “Let’s try this for the next week. We can report back at our next team meeting.”

Teaching Kids to Find Word Meaning

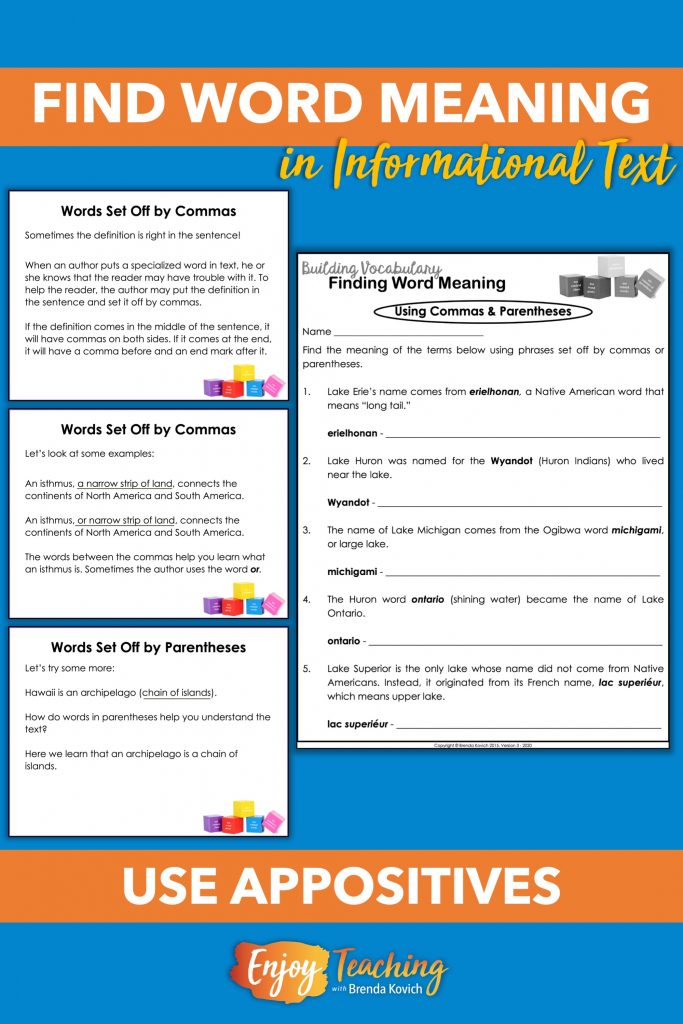

Day #1: Appositional Phrases

The following day, Ms. Sneed dug in with direct instruction. “This week, we’ll learn how to determine the meaning of unknown words in a text,” she told her class. “Today we’ll work on appositives. Also known as appositional phrases, these words are set off by commas or parentheses. The definition is right in the sentence!”

Ms. Sneed presented the first portion of the slideshow, which explained and modeled the process. Afterward, she asked kids to complete some targeted practice on the skill.

“This is really easy,” piped up one child.

“Sure it is,” Ms. Sneed responded, “once you know what you’re looking for!”

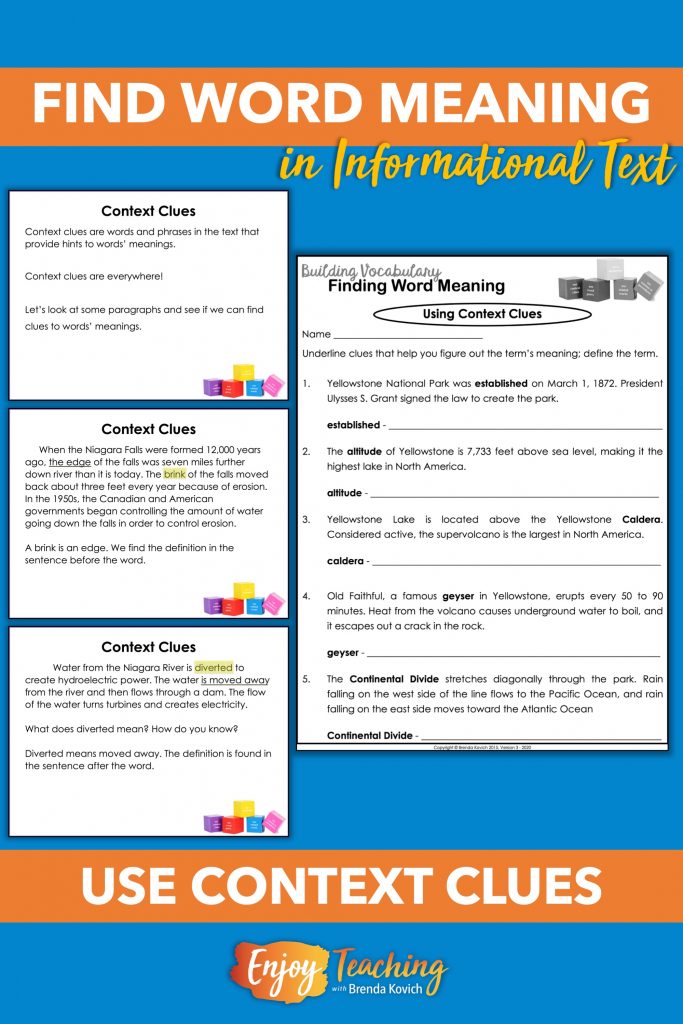

Day #2: Context Clues for Word Meaning

The next day, Ms. Sneed and her class tackled context clues. “Did you know,” the teacher asked, “that clues about word meaning are everywhere? If you put on your detectives’ hats, you can figure out just about any word.” Again, she showed a portion of the slideshow. Then the kids practiced their new strategy.

For this skill, Ms. Sneed noticed a little more struggle. She bent over one student’s desk to help. “Look beyond the sentence that the word is in,” she coached.

Day #3: Word Parts

On the third day, Ms. Sneed addressed her class. “Another vocabulary strategy for finding the meaning of unknown words is using word parts.” Once again, she showed a portion of the slideshow.

“This strategy will take some extra work,” she said. “We need to learn the meanings of new word parts. As you complete today’s worksheet, think about parts you already know.”

“I know the words outdoors and man,” one little voice said. “So I know what an outdoorsman is!”

“Today we’ll think about words that look or sound like the unknown word,” Ms. Sneed began. “You’ll be surprised with your success. Most words that look alike also have similar meanings.”

For the last time, she showed a portion of the slideshow.

A student in the back remarked, “I never knew there were so many kinds of volcanos!”

Ms. Sneed smiled. “Now let’s try the worksheet.”

The boy in the desk next to the teacher was already working. “Disastrous. Disaster,” she heard him say.

Day #5: Word Meaning Mixed Practice

“Yay!” Ms. Sneed said on the fifth day. “We’ve learned all four strategies for finding word meaning. Now you’ll do some mixed practice.”

Quickly, teacher distributed the worksheets. “You’ll notice a fifth vocabulary strategy on this page: using a glossary or dictionary. Only use this if it’s absolutely necessary.”

Ms. Sneed circulated as her students worked.

“Hey,” she heard a girl say to her neighbor, “this is easy now that we know the strategies.” That famous teacher smile crept across Ms. Sneed’s lips.

Improving Vocabulary While Teaching

The next day, Ms. Sneed sat at the back table with her teaching partner. “High five to you,” said Mr. Frank. “My kids’ reading comprehension grew by leaps and bounds this week. Targeting vocabulary strategies for word meaning really works.”

“You know,” said Ms. Sneed, “I’ve realized that mirroring these strategies while teaching will improve kids’ vocabulary.”

Mr. Frank looked thoughtful. “I’m not exactly sure what you mean. Please go on.”

“If, for example, I’m talking about precipitation, I can use appositional phrases to remind kids what it is. I don’t have to stop. Instead, I add the definition as I teach. I can say, ‘Precipitation, the rain and snow a place receives, affects the biosphere.’”

“Hmm. I see what you mean. Piggybacking off of that, you could go to the whiteboard, split the word biosphere into bio and sphere, and quickly explain.”

“Exactly. I really think teaching incidental vocabulary could improve our teaching. Are you up for a challenge?”

Mr. Frank gave an uncertain grin. “Sure. Let’s hear it.”

“Over the course of the week, we’ll consciously use strategies to find word meaning as we teach. Then next week, we’ll report back on our progress.”

“I think that’s called metacognition, or thinking about one’s own thought processes,” Mr. Frank laughed. “And that’s the beginning of my new teacher talk – in appositional phrases.”

“Gotta love sharpening the tools in that teacher toolbox.” Ms. Sneed’s eyes twinkled.

Table of Contents

- How to Teach Vocabulary

- Theoretical background

- Importance of vocabulary

- Vocabulary knowledge

- Defining and identifying vocabulary

- From words to lexis

- Words in relation to other words

- Content versus function words

- How is vocabulary knowledge organized?

- How we learn vocabulary

- How we remember words

- Pedagogical implications for teaching vocabulary

- Principles of vocabulary learning

- Sources of vocabulary

- Stages of vocabulary teaching

- The sequence of vocabulary presentation

- Discovering vocabulary

- Learner training

- References

This article is about how to teach vocabulary. It consists of two main parts:

- a theoretical background about vocabulary learning

- and the pedagogical implications for teaching vocabulary.

The ideas presented in this article are inspired by Scott Thornbury’s excellent book “How to teach vocabulary” (2002) (which I highly recommend) as well as other readings (see the references below).

Theoretical background

According to Vygotsky, “A word is a microcosm of human consciousness”. Thought and speech are closely interlinked. Language essentially forms thought, determines personality features, and exerts influence on cognition. A vocabulary item for instance embodies not only a definition but a whole set of cultural connotations.

Importance of vocabulary

Once David Wilkins said:

Without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed.

If you travel to a foreign country, you will probably carry a dictionary and not a grammar book. Hence, the importance of vocabulary.

Vocabulary knowledge

One can never fully master vocabulary. All one can do is get some deeper knowledge of it. Steven Stahl (2005) states that “vocabulary knowledge is knowledge; the knowledge of a word not only implies a definition but also implies how that word fits into the world.” What we learn about a word goes far beyond its form. Making connections between form and meaning is only one side of the coin. The other side is to be able to produce language using the correct form of a word in the appropriate context and for the meaning intended. In other words, knowing a word means knowing its form, its meaning, its connotations, how it collocates with other words, and how it fits within a whole network of meanings.

Defining and identifying vocabulary

A dictionary definition states that vocabulary is the “body of words used in a particular language.” However, this definition lacks some precision. What is meant by a “body of words“? Let’s consider the following sentence cited by Scott Thornbury (2002):

“I like looking for bits and pieces like second-hand record players and doing them up to look like new.”

How many vocabulary items are there in the above sentence? Twenty? ninety? or less? Will you count these as vocabulary items representing discrete units of meaning or as different words?

- second-hand?

- record player?

- do something up?

- bits and pieces?

- look for?

It is clear that the above examples consist of discrete units of meanings. The idiom “bits and pieces” is a fixed expression. You can’t change the order of words. For instance, you can’t say “pieces and bits”. Similarly, should we consider the phrasal verb “look for” as one whole unit of meaning or as two words? And what about this word?

- like?

There are two instances of the same form with unrelated meanings.

- “I like looking for bits and pieces” where like is a verb.

- “…to look like new.” where like is a preposition.

Let’s take another word: KEEP.

According to the Longman dictionary:

- As a verb, keep has 19 meanings: to store, to retain, to have a supply, to have charge of…

- Combined with other particles, the result is a variety of phrasal verbs: keep up, keep off, keep at…

- As a noun, it has 2 meanings: ”she is in my keep for the day”, “earn one’s keep”.

- Used in collocations, the result is:

keep a diary

keep a promise

keep a secret

keep an appointment

keep calm

keep control

keep in touch

keep quiet

keep someone’s place

keep the change

…

From words to lexis

Vocabulary is not only “a body of single words”. According to the lexical approach developed by Michael Lewis, vocabulary consists of:

- Single words: book, pen…

- Compound words (words combined to form new words): record player, time saver….

- Multi-word units or lexical chunks which are more or less fixed: by the way, upside down, out of the blue, bits and pieces.

- Collocations or word partnerships which are less fixed: break a record, set a record, world record, formal education, formal letter…

Words in relation to other words

Words are related to other words in different ways:

- Synonyms vs. Antonyms

- Homonyms vs. Polysemes

- Hyponyms vs. superordinate terms

- Content vs. function words

- Productive vs. receptive words

- False vs. true cognates

Synonyms

These are words that share the same meaning:

- old, ancient, elderly, aged, antique…

However, synonymous words are not always used in the same way:

- An old/ancient city but not an *elderly car.

Antonyms

Antonyms are words opposite in meaning to other words. For example:

- Old is the antonym of new and young

However,

- the opposite of an old man is a young man, but the opposite of an old city is a new one, not a *young city.

Homonyms

These are words that share the same form but have unrelated meanings:

- I like looking for …

- It looks like new

- Go to the fair.

- It’s a fair price.

Polysemes

These are words that have multiple but related meanings. Examples:

- The house is at the foot of the mountains.

- One of his shoes felt too tight for his foot.

Hyponyms and superordinate terms

A superordinate term acts as an umbrella term that includes other words with related meanings.

The words that are related in meaning with the superordinate terms are called hyponyms. Let’s take examples:

- The term ‘tools’ is a superordinate term. Hammer, Screwdriver, and Saw are co-hyponyms. The term Saw itself a superordinate. It is an umbrella term for: Fretsaw , Chainsaw and Jigsaw which are all co-hyponyms.

Content versus function words

Content words carry meaning. They fall into 4 main parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. Examples:

- Play, House, Computer, Enjoyable

Function words, however, are necessary words for grammar. Examples of function words include pronouns, determiners, and prepositions.

Receptive versus productive words

As Thornbury (2002) states “we understand more words than we utter”. Word knowledge can be receptive or productive. Receptive knowledge consists of a larger repertoire of words of which learners have some degree of understanding but do not use. By contrast, productive knowledge is the less large repertoire of active vocabulary that learners understand and actually use to communicate.

True versus false cognates

Two different languages may share a body of vocabulary items that are related in origin. These are called cognates. Sometimes, cognates can be helpful to language learners (i.e. vrais amis). Other times, they may be misleading (i.e. faux amis). This table contains six pairs of English-French cognates:

| Cognates | False | True |

| Family | √ | |

| Actually | √ | |

| Gratitude | √ | |

| Information | √ | |

| Attend | √ | |

| Coin | √ |

How is vocabulary knowledge organized?

According to Thornbury, (2002):

The mind seems to store words neither randomly, nor in the form of a list, but in a highly organized and interconnected fashion – in what is called a mental lexicon

Learning vocabulary is more like network building. Learners start by labeling things and end up categorizing these labels. The process is similar to what a baby does to acquire the mother tongue vocabulary. When a baby sees a dog for the first time, it first starts by knowing its name (i.e. labeling it). The baby goes through the same process to name cat and horse. Then an umbrella term (i.e. a superordinate term), namely, “animals” is used to categorize the three terms. The same procedure is used to build other related sets of vocabulary items.

Foreign or second language learners need to build a large network of vocabulary to be able to communicate with native speakers. Research suggests that these learners need to know at least 2000 of high-frequency words.

There are however challenges facing learners when they try to build such a network of lexical items:

- The coining of new words never stops.

- Old words continually get new meanings.

How we learn vocabulary

Vocabulary learning can be incidental, through indirect exposure of words, or intentional, through explicit instruction in specific words and word-learning strategies.

How we remember words

There are three types of memory:

- Short-term memory

- Working memory

- Long-term memory

The short term memory holds vocabulary items in one’s mind for a few seconds. These vocabulary items become part of the working memory once learners start manipulating and working with them through activities such as:

- looking them up in a dictionary,

- matching them with synonyms or antonyms,

- sequencing them,

- ranking them according to their importance,

- identifying their collocates etc.

Vocabulary items are stored in the long-term memory to become durable over time when learners repeatedly meet them in different contexts.

Pedagogical implications for teaching vocabulary

To teach vocabulary, teachers should help learners:

- …acquire a critical mass of words for use in both understanding and producing language. (At least 2000 high-frequency words)

- …remember words over time and be able to recall them readily.

- …develop strategies to learn new vocabulary.

Principles of vocabulary learning

Vocabulary learning should be based on the following principles:

Repetition and multiple encounters

Not only memorizing words through repetition (i.e. rote learning), but also repeated encounters of words.

Cognitive depth

This refers to the manipulation of words by learners. The decisions they make about the words are of paramount importance. Cognitive depth principle includes activities such as using a dictionary to look up a word, matching words with their synonyms or antonyms, identifying collocations, sequencing words, gap-fills…

Affective depth

Learners do not need only cognitive information about words, but they also need to entertain some affective or emotional relationship with words in order to be memorable. For example, asking learners to choose a number of words (they like) from a text to write a story/a paragraph about themselves can lead to an affective depth.

Retrieval

The more one recalls a word, the more it becomes memorable.

Re-contextualization

Words have to be met and used to say new things in different contexts in reading, listening, speaking and writing. This has a positive impact on learning.

Personalization (Use it or lose it)

Using the words learned to express personal experiences.

Spacing

This refers to distributed practice. The interval between the successive practice of a set of words should gradually increase.

Sources of vocabulary

Here are the main sources of vocabulary:

- Textbooks

- Teachers

- learners themselves

- Lists

- Dictionaries

- books/Short texts

- …

Let’s focus on textbooks.

Textbooks

As far as textbooks are concerned, vocabulary is presented in three different ways:

- Segregated vocabulary sections

- Integrated into text-based activities

- Incidentally learned in different tasks (grammar, reading, instructions…)

Segregated vocabulary sections

These are sections where a group of words (lexical sets) that share a relation of hyponymy is presented. Here are two examples of lexical sets that may be incorporated in these sections:

- boat, car, bus, helicopter, plane, bicycle, ship… (They are all co-hyponyms of the superordinate term means of travel.)

- Hot, cold, warm, rainy, cloudy, foggy…(They are all co- hyponyms of the superordinate term weather.)

Integrated into text-based activities

Vocabulary teaching is integrated into TEXTS in:

- Pre-task activities such as

1. pre-teaching vocabulary using techniques such as pictures, simplified definitions, translation…

2. Discussion about the topic of the text through activities such as

– selecting from a list the words that fit the theme,

– brainstorming… - While-tasks through activities such as searching the text for synonyms, antonyms, hyponyms, words that match a definition…

- Follow-up activities through discussions where learners

1. react, comment, and argue about the topic of the text

2. or simply use the vocabulary learned to talk about his personal experiences.

Vocabulary incidentally learned in different tasks

This is vocabulary embedded in

- Instructions

- Classroom language

- Listening / Reading

- Grammar terms (verb, simple past, noun….)

- Functional terms (inviting, apologizing, complaining….)

Stages of vocabulary teaching

Encountering

- Teacher presents vocabulary items.

OR

- Learners notice contextualized vocabulary items.

Integrating

- Learners understand and manipulate vocabulary items.

- Tasks to transfer vocabulary to long-term memory.

Producing

- Learners use target vocabulary in novel situations.

- Personalization.

The sequence of vocabulary presentation

The sequence of new vocabulary presentations can be in two different ways:

First form, then meaning:

That is, the teacher provides the word in a context and students notice how it is used and try to guess its meaning

First meaning, then form:

That is, the teacher shows/points to an object, creates the need for the word and then provides it.

Presenting the meaning first, then the form is a sequence that is probably appropriate when teaching vocabulary in a hurry (e.g. pre-teaching vocabulary in the pre-reading stage), or when you want to teach perhaps a set of lexical items in an isolated section of the textbook.

However, providing form first, then meaning is perhaps the best technique to guide learners to discover the meaning of vocabulary by themselves.

Discovering vocabulary

As mentioned above, vocabulary can be:

- Presented by the teacher using: realia (i.e. real things), pictures, miming (i.e. actions/ gestures), definitions, situations, translations…

OR

- Discovered by learners.

Vocabulary is discovered by learners when teachers contextualize the vocabulary items, preferably, in short texts. Here is an example of the sequence of a vocabulary lesson based on guided discovery.

Encountering new vocabulary

- At the presentation stage, or better at the stage where learners encounter new vocabulary items, the teacher provides contextualized exposure to these vocabulary items. This can be a written or spoken text.

- After quick comprehension activities, the teacher raises learners’ awareness of the target vocabulary items and asks them to notice their form and use in that particular context.

- Learners make guesses about the meaning.

- The teacher then provides activities where learners match, select, or identify words with their definitions.

Integrating vocabulary

This stage involves practice activities where learners manipulate and work with the vocabulary items. In other words, they put vocabulary to work to satisfy the cognitive depth principle through activities such as:

- sorting or categorizing the words under some headings,

- matching words with their collocates,

- sequencing a list of words according to a certain logic (e.g. wake up, have a shower, go to school…)

- …

Production

This is the stage where learners use the vocabulary items to talk about real things in their lives. Personalization of vocabulary items may lead to some kind of affective depth. Teachers may ask their learners, for example, to CHOOSE a certain number of words from the text (let’s say 4 words) and use them to talk about their personal experience or to write a story…

Learner training

“Vocabulary cannot be taught”

Wilga Rivers

Yes, it is difficult to teach vocabulary. In fact, there are many challenges in vocabulary teaching:

- The coining of new words never stops.

- We are continually learning new meanings of old words.

- The power of words can never be fully grasped.

Learners can never reach a deeper knowledge of the vocabulary we teach them unless they are trained to do so by themselves. Hence, the importance of training learners to develop learning strategies to cope with new vocabulary.

We have to train learners to…

- Guess meaning from context

- Use dictionaries

- Keep organized records

- Use mnemonics

- Discover spelling rules

References

- Stahl, S. A. (2005). “Four problems with teaching word meanings (and what to do to make vocabulary an integral part of instruction),” in E. H. Hiebert and M. L. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

- Thornbury, S. (2002). How to teach vocabulary. Harlow: Longman.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

“Vocabulary size is a convenient proxy for a whole range of educational attainments and abilities – not just skill in reading, writing, listening, and speaking, but also general knowledge of science, history, and the arts.”

A wealth of words, by E. D. Hirsch Jr

Vocabulary is something we continue to learn and develop throughout our entire lives – an unconstrained skill. While some vocabulary is acquired implicitly through everyday interactions, it’s important to teach more complex and technical vocabulary explicitly. We can’t rely on fate, osmosis and exposure for students to learn the 50,000+ words they need to thrive in school and beyond.

Further, vocabulary is becoming more important in a world of digital dependency. Autocorrect may have a chance of picking up incorrect spelling, but it can’t be relied on to help you choose the word with the right meaning.

Teaching vocabulary is about context and repetition– what they need to know about the words they’re using, and using them multiple times.

But before we get onto that, here are some key things we have to understand to teach vocabulary:

The three tiers of vocabulary

For the past two decades, it has been acknowledged that there are three broad tiers of vocabulary. An awareness of these tiers is critical to assist teachers in selecting the right words to teach explicitly in their classrooms – from the first day of school to the last.

Tier 1

These are basic words of everyday language – high frequency words. With around 8000 word families in Tier 1, including words like ‘dog’, ‘good’, ‘phone’ and ‘happy’, these words do not generally require explicit teaching for the majority of students. However, explicit teaching is required to make the most of this level of vocabulary particularly for homophones and words with more than one meaning.

Tier 2

Tier 2 words are the words needed to understand and express complex ideas in an academic context. Tier 2 includes words like ‘formulate’, ‘specificity’, ‘calibrate’ and ‘hypothesis’. These words are useful across multiple topics and subject areas and effective use can reflect a mature understanding of academic language.

Tier 3

Tier 3 words aren’t used often and are normally reserved for specific topics or subjects – words like ‘orthography’, ‘morphology’ and ‘etymology’ in the field of linguistics, or ‘isosceles’, ‘circumference’ and ‘quantum’ for the world of mathematics and physics. Some of these words may also exist as a Tier 1 or 2 word but have a particular use and purpose as a Tier 2 word, such as ‘substitute’, ‘similarity’ and ‘expression’ in a mathematical context. These words must be taught explicitly in the context of their meaning and purpose in a particular unit of study.

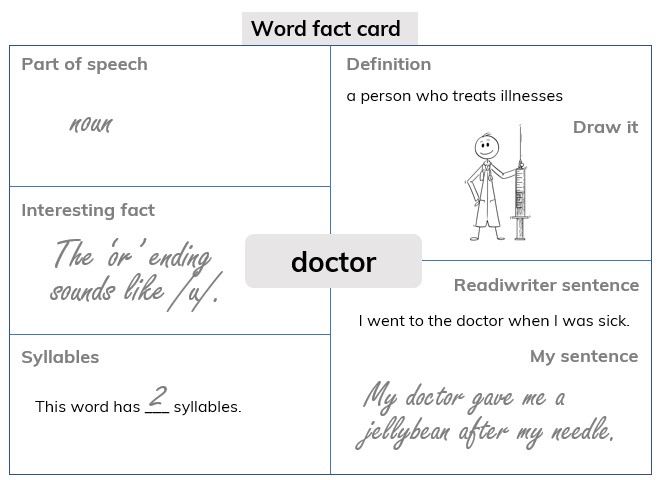

Did you know? The Reading Eggspress Vocabulary program focuses on the critical Tier 2 and academic vocabulary terms that students need to understand to be able access the increasingly difficult texts they encounter. The lessons are organised in a systematic and easy to follow format with technology that adapts to student responses.

Learn more about Reading Eggspress (part of Reading Eggs) vocabulary program here

Take me there

Vocabulary development by age

Students’ communication abilities, including their vocabulary, can vary immensely. However, there are certain milestones we can expect children to reach before starting formal schooling:

- 12 months: 2 words plus mummy/mommy and daddy (or equivalent in languages other than English)

- 18 months: 10-50 words

- 2 years: 300 words

- 5 years: 450 words

- 3 years: 1000 words

- 4 years: 2000 words

- 5 years: 5000 plus words

This early language acquisition is an essential platform for future learning. There is a huge body of evidence suggesting that deficient early vocabulary development is a strong marker for a continued difficulty in all aspects of schooling.

During the school years, vocabulary size must grow at a rapid pace in order to equip students for everyday, as well as academic, communication. By the age of 17, students are expected to know between 36 000 to 136 000 words.

So just what is it that allows some students to learn a staggering 100 000 more words than their peers?

Teaching vocabulary

Effective vocabulary instruction within the 6M Learning Framework includes opportunities to motivate, model, master, magnify and maintain vocabulary knowledge with meaningful feedback guiding the sequence of learning.

Motivate

Students need to understand the benefits of a rich vocabulary knowledge. As with all teaching, some students may be naturally curious, while others will need to be coaxed into the journey. Some tips and tools for enhancing motivation are:

- Take the time to demonstrate the value of a rich vocabulary knowledge

- Make word exploration an integral part of classroom culture

- Create a word-rich environment

- Find puns, jokes and other comedic devices to add engagement to word studies, especially those that humorously interchange multiple meanings

- Designate a word of the week with a challenge to use it creatively in that week’s work

Model

In an explicit approach to vocabulary instruction, teachers should model the skills and understanding required to develop a rich vocabulary knowledge.

Say the word carefully. Pronunciation is critical to allow students to make strong connections between written and spoken language. Use syllabification to assist in articulating each part of the word.

Write the word. There is a strong correlation between spelling and vocabulary. To allow students to access their vocabulary in both passive and active contexts, they must be equipped to spell new vocabulary.

Give a student-friendly definition. The concise nature of dictionaries means they require significant vocabulary knowledge to interpret. Simply providing students access to dictionaries and thesauruses will not necessarily give them the information they need to understand the meaning of the word. Provide a definition that is meaningful for students, their experiences and their existing vocabulary knowledge.

Give multiple meaningful examples. Use the word in sentences and contexts that are meaningful to students. But don’t stop at one! Provide a wide range of examples to allow everyone to connect and relate to the word.

Ask for student examples. It may be valuable to have students attempt to articulate their own examples of the word in context. By including this in the explicit teaching phase, there are opportunities to clarify understanding when words have multiple meanings and deal with any misconceptions.

Master

Provide opportunities for students to master an understanding of new vocabulary in context through hearing, saying, reading and writing.

Using words is the best way to remember them. The following methods can help learners to consolidate their vocabulary knowledge:

Show students how to recognise new words

The best way to help students to remember and retain the new words they’re introduced to is to connect it with an object in the real world. Pictures and flashcards are good, but real-world items are even better. This can get difficult with more abstract words, but by dedicating more time and thought, the image or object used, and your explanation of it, will help build students understanding.

Reinforce their remember new words

After a word has been introduced, we want students to see it at least 10 more times so it sticks. Activities like ‘fill in the blank’ and ‘word bingo’ help students make strong connections between the introduced words.

Have them use their new words

After new words have been introduced, students are ready to find the ways they can use these words to make meaning. Activities like using the word in a sentence, mind maps, fill in the blanks (with no options) develop students’ use of words as tools for meaning and communication.

Graphics organisers

A simple graphic organiser can be an effective method to help students master their knowledge of new words.

Magnify

Magnify vocabulary understanding through a word rich environment. Create a classroom where words are valued. Provide continued opportunities to explore words at a deep level.

- Explore word origins

Investigate the etymology of words and help students make connections within and between words. Understanding of common word parts helps learners to grasp meanings, even of words they have not encountered before.Create word families based on a particular etymological feature. For example, find words with ‘aqua’ or ‘hydra/o’ in their spelling – both referring to water. Predict the meanings of these words based on their smaller parts. - Explain the word’s connotation

This is the relationship between the word and the feelings about it, whether positive, neutral or negative. Understanding how words can be interpreted enables students to use them with greater precision.Try compiling a word scale. Place a word on one end of the scale and a word with opposite meaning or intensity at the other. For example, if students are struggling to use words instead of ‘said’, place the word ‘whisper’ at the lower end and ‘bellow’ at the higher end. Students work together to build the scale, searching for synonyms like ‘shout’, ‘yell’, ‘plead’, ‘intone’ and placing them at appropriate points on the scale. - Explaining where and when the word is or isn’t used

This can be anything from a word’s formality to its datedness. You might use ‘loo’ at home, ‘toilet’ in public or ‘lavatory’ at the Mayor’s Ball, and ‘ball’ would be outdated. This helps students understand how words can make people sound. Try demonstrating this by writing an inappropriately informal text to highlight the importance of word choice. Alternatively, write an overly formal text to convey a simple, friendly message. - Building the relationship from words to other words

This is how students understand what words have the same, similar, opposite or related meanings. Taking them through words synonyms, antonyms and words or concept that build off words helps them develop their lexical stores. Set aside time for word study. Provide graphic organisers to assist learners to make comparisons and build connections. - Showing what words occur together

This is called ‘collocation’ – it’s why we say ‘see the big picture’ instead of ‘see the tall picture’ or 10 apples is fewer than 15 apples rather than less. Collocation must occur in context, so shared reading is an excellent forum for this sort of word study. But also have a bit of fun by using synonyms to create ‘nearly but not quite’ versions of well-known sayings. - How affixes change meaning

Most words can be changed by adding affixes – prefixes before the word and suffixes after the word. But a rich vocabulary can be developed by understanding the purpose of prefixes and suffixes and how they impact part of speech and inform meaning.To help students get to grips with affixes and how they can change meaning, select a ‘friendly’ root word and explore all of the word building creations that are possible. For example, the word ‘social’ can be added to create: socialise, socially, unsocial, antisocial, unsociable, etc.

Maintain

Maintain learning through repeated practice and revision.

There are many great game ideas to help you find creative ways to revisit learning after one day, one week and one month.

Bonus strategies for teaching vocabulary

1. Word of the day

Create a daily roster for students to share a newly discovered or unusual word with the class. They can get creative with the definition too by acting it out, giving synonyms, or doing a Pictionary style drawing on the board.

2. Creative writing

Compile the week’s ‘words of the day’ and task students with writing a story that uses as many of them as possible. They’ll learn how to use their new vocabulary in context.

3. Class glossary

Build up a list of unfamiliar words the class encounters when reading a text or studying a topic. Each student can choose a word and create a glossary page for it, complete with a definition, pronunciation guide, sentence example, mnemonic (memory aid), and an image that sums up its meaning.

The challenges of teaching vocabulary

Explicit teaching of vocabulary is frequently overlooked in the busyness of the typical classroom.

Many teachers believe that vocabulary can be acquired without the need to provide targeted instruction. Others teachers are unaware of the need to teach vocabulary explicitly. Some lack the training or understanding of the skills involved. And some are simply overwhelmed by the competing voices of education priorities.

In a world where information is always available, some teachers simply provide access to the resources that students can use to build their vocabulary independently – such as dictionaries, thesauruses and online tools.

And while the end goal is autonomous and independent learners, students already struggling with a low vocabulary need significant support and explicit teaching to use these tools effectively.

The complexity of the English language presents homophones, homographs, polysemous words (words with multiple meanings) as well as the confusion of everyday words being used in idiomatic and figurative contexts.

It is essential for teachers to support students in their acquisition of a growing vocabulary. But to do so, they must themselves be equipped with a rich vocabulary and a deep understanding of the richness and value of words.

Looking to build your students’ vocabularies?

Reading Eggspress Lessons use a combination of teaching videos, engaging online activities and games with printable worksheets and assessment tests. The program includes a variety of instructional strategies including: word building, word sorts, word mapping, morphemic analysis, context reading, word consciousness and deep understanding and close reading of text.

Sources

The Three Tiers of Vocabulary Development – ASCD.org

Concept Development and Vocabulary – Education Victoria

It’s hard for students to read and understand a text if they don’t know what the words mean. A solid vocabulary boosts reading comprehension for students of all ages. The more words students know, the better they understand the text. That’s why effective vocabulary teaching is so important, especially for students who learn and think differently.

In this article, you’ll learn how to explicitly teach vocabulary using easy-to-understand definitions, engaging activities, and repeated exposure. This strategy includes playing vocabulary games, incorporating visual supports like graphic organizers, and giving students the chance to see and use new words in real-world contexts.

The goal of this teaching strategy isn’t just to increase your students’ vocabulary. It’s to make sure the words are meaningful and relevant to their lives.

Watch: See teaching vocabulary words in action

Watch this video of a kindergarten teacher teaching the word startled to her students:

Explore topics selected by our experts

Read: How to use this vocabulary words strategy

Objective: Students will learn the meaning of new high-value words and how to use them.

Grade levels (with standards):

- K–5 (CCSS ELA Literacy Anchor Standard L.4: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases)

- K–5 (CCSS ELA Literacy Anchor Standard R.4: Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text)

Best used for instruction with:

- Whole class

- Small groups

- Individuals

Choose the words to teach. For weekly vocabulary instruction, work with students to choose three to five new words per week. Select words that students will use or see most often, or words related to other words they know.

Before you dive in, it’s helpful to know that vocabulary words can be grouped into three tiers:

- Tier 1 words: These are the most frequently used words that appear in everyday speech. Students typically learn these words through oral language. Examples include dog, cat, happy, see, run, and go.

- Tier 2 words: These words are used in many different contexts and subjects. Examples include interpret, assume, necessary, and analyze. The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium has a partial list of Tier 2 words, broken down by grade levels.

- Tier 3 words: These are subject-specific words that are used in particular subject areas, such as peninsula in social studies and integer in math.

When choosing which vocabulary words to teach, you may want to pick words from Tier 2 because they’re the most useful across all subject areas.

Select a text. Find an appropriate text (or multiple texts for students to choose from) that includes the vocabulary words you want to teach.

Come up with student-friendly definitions. Find resources you and your students can consult to come up with a definition for each word. The definition should be easy to understand, be written in everyday language, and capture the word’s common use. Your definitions can include pictures, videos, or other multimedia options. Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Learner’s Dictionary, and Wordsmyth Children’s Dictionary are all good resources to help create student-friendly definitions.

1. Introduce each new word one at a time. Say the word aloud and have students repeat the word. For visual support, display the words and their definitions for students to see, such as on a word wall, flip chart, or vocabulary graphic organizer. Showing pictures related to the word can be helpful, too.

For English language learners (ELLs): Try to use cognates (words from different languages that have a similar meaning, spelling, and pronunciation) when you introduce new words. For more information about using cognates when teaching vocabulary to ELLs, use these resources from Colorín Colorado. You can also ask students to say or draw their own definition of the words — in English or their home language — to help them understand each word and its meaning.

2. Reflect. Allow time for students to reflect on what they know or don’t know about the words. Remember that your class will come to the lesson with varying levels of vocabulary knowledge. Some students may be familiar with some of the words. Other students may not know any of them. If time permits, this could be a good opportunity to use flexible grouping so students can work on different words.

3. Read the text you’ve chosen. You can read it to your students or have students read on their own (either a printed version or by listening to an audio version). As you read, pause to point to the vocabulary words in context. Use explicit instruction to teach the word parts, such as prefixes and suffixes, to help define the word. If students are reading on their own or with a partner, encourage them to “hunt” for the words before reading. Hunting for these words first can reduce distractions later when the focus is on reading the text.

4. Ask students to repeat the word after you’ve read it in the text. Then remind students of the word’s definition. If a word has more than one meaning, focus on the definition that applies to the text.

5. Use a quick, fun activity to reinforce each new word’s meaning. After reading, use one or more of the following to help students learn the words more effectively:

- Word associations: Ask students, “What does the word delicate make you think of? What other words go with delicate?” Students can turn and talk with a partner to come up with a response. Then invite pairs to share their responses with the rest of the class.

- Use your senses: Ask your students to use their senses to describe when they saw, heard, felt, tasted, or smelled something that was delicate. Allow students time to think. Then ask them to give a thumbs up if they’ve ever seen something delicate. Call on students to share their responses. Do the same with each of the senses.

- A round of applause: If the word is an adjective, invite students to clap based on how much they would like a delicate toy, for example. Or students can “vote with their feet” by moving to one corner of the room if they want a delicate toy or another corner if they don’t. This activity works especially well if you pair the new adjective with a familiar noun.

- Picture perfect: Invite students to draw a picture that represents the word’s meaning.

- Examples and non-examples: Give one example and one non-example of how the word is and isn’t used. For instance, you could tell students that one thing that is delicate is a teacup. One thing that isn’t delicate is the cement stairs into the school. Then invite students to share their own examples of things that are and aren’t delicate.

After students do one or more of the activities above, have them say or draw the word again.

6. Play word games. Throughout the week, play word games like vocabulary bingo, vocabulary Pictionary, and charades to practice the new words. Include words you’ve taught in the past for additional reinforcement.

7. Challenge students to use new words. They can use their new vocabulary in different contexts, like at home, at recess, or during afterschool activities. Consider asking students to use a vocabulary notebook to jot down when they use the words. You can even get your colleagues or school administrators in on the fun by asking them to use the words when talking with students or in announcements. Praise students when you hear them using those words in and out of the classroom.

Understand: Why this strategy works

Rote memorization (“skill and drill”) isn’t very helpful when it comes to learning new vocabulary. Students learn best from explicit instruction that uses easy-to-understand definitions, engaging activities, and repeated exposure. Teaching this way will help students understand how words are used in real-life contexts and that words can have different meanings depending on how they’re used.

This explicit approach helps all students and is especially helpful for students who learn and think differently. This includes students who have a hard time figuring out the meaning of new words when they’re reading. It can be difficult for them to make an inference or use context clues to figure out what a word means.

Explicit vocabulary instruction with student-friendly definitions means there’s no guesswork involved. Repeated exposure and practice help to reinforce the words in students’ memories.

Connect: Link school to home

Share with families this resource they can use at home to help students grow their vocabulary. You can model some of these strategies for families at back-to-school night or another family event.