What Makes a Word a Word

Updated on November 01, 2019

According to conventional wisdom, a word is any group of letters that can be found in a dictionary. Which dictionary? Why, the Unidentified Authorizing Dictionary, of course:

‘Is it in the dictionary?’ is a formulation suggesting that there is a single lexical authority: «The Dictionary.» As the British academic Rosamund Moon has commented, «The dictionary most cited in such cases is the UAD: the Unidentified Authorizing Dictionary, usually referred to as ‘the dictionary,’ but very occasionally as ‘my dictionary.’

(Elizabeth Knowles, How to Read a Word. Oxford University Press, 2010)

To characterize this exaggerated regard for the authority of «the dictionary,» linguist John Algeo coined the term lexicographicolatry. (Try looking that up in your UAD.)

In fact, it may take several years before a highly functional word is formally recognized as a word by any dictionary:

For the Oxford English Dictionary, a neologism requires five years of solid evidence of use for admission. As the new-words editor Fiona McPherson once put it, «We need to be sure that a word has established a reasonable amount of longevity.» The editors of the Macquarie Dictionary write in the Introduction to the fourth edition that «to earn a place in the dictionary, a word has to prove that it has some acceptance. That is to say, it has to turn up a number of times in a number of different contexts over a period of time.»

(Kate Burridge, Gift of the Gob: Morsels of English Language History. HarperCollins Australia, 2011)

So if a word’s status as a word doesn’t depend on its immediate appearance in «the dictionary,» what does it depend on?

Defining Words

As linguist Ray Jackendoff explains, «What makes a word a word is that it is a pairing between a pronounceable piece of sound and a meaning» (A User’s Guide to Thought and Meaning, 2012). Put another way, the difference between a word and an unintelligible sequence of sounds or letters is that—to some people, at least—a word makes some sort of sense.

If you’d prefer a more expansive answer, consider Stephen Mulhall’s reading of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (1953):

[W]hat makes a word a word is not its individual correspondence with an object, or the existence of a technique of its use considered in isolation, or its contrasts with other words, or its suitability as one component of a menu of sentences and speech-acts; it depends in the last analysis upon its taking its place as one element in one of the countless kinds of ways in which creatures like us say and do things with words. Inside that unsurveyable complex context, individual words function without let or hindrance, their ties to specific objects without question; but outside it, they are nothing but breath and ink…

(Inheritance and Originality: Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Kierkegaard. Oxford University Press, 2001)

Or as Virginia Woolf put it:

[Words] are the wildest, freest, most irresponsible, most un-teachable of all things. Of course, you can catch them and sort them and place them in alphabetical order in dictionaries. But words do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind.

When writing, I sometimes want to refer to a word, as opposed to its meaning. For example: when correcting someone’s grammar or semantics (there versus their), or when pointing out exemplary vocabulary.

On websites like this, I can simply italicize the word in question.

Abjure is a good word.

This feature isn’t always available, though — notably in simple online chatrooms, and even in this website’s question titles.

I’ve been using quotation marks, but now I’ve started second-guessing myself.

«Abjure» is a good word.

Abjure is a good word.

Is there a good way to refer to a specific word without throwing off the reader?

asked Oct 4, 2011 at 21:06

3

There’s two types of solutions that I can think of:

- Change the expression of the word to indicate that you refer to the word, e.g. by change of type (italics, small caps, etc.) or by enclosing it in some symbols (quotation marks).

- Explicitly state that you refer to the word, e.g. «The word Abjure is a good word.»

If you use the former solution I think it’s best to go with single quotation marks, e.g.

‘Abjure’ is a good word.

For reference Grammar girl says:

Use Single Quotation Marks to Highlight Words Not Being Used for Their

MeaningIt’s the convention in certain disciplines such as philosophy,

theology, and linguistics to highlight words with special meaning by

using single quotation marks instead of double quotation marks.

answered Oct 4, 2011 at 21:11

N.N.N.N.

5001 gold badge6 silver badges24 bronze badges

5

I don’t have a reference handy, but I was taught in school to enclose the word in quotation marks. Normally double-quotes, but if it’s nested inside a quote, then use single quotes.

While there are probably many cases where the meaning would be obvious, one can easily think of confusing cases. Like: «The word above should not be used here.» Do I mean the word spelled a-b-o-v-e? Or do I mean a word mentioned earlier in the document?

It’s like the old joke:

Boss: There’s one word I never want to hear you use again when rejecting a customer’s request. That word is «unacceptable». Please, never say it.

Employee: Sure boss. So what’s the word?

answered Oct 5, 2011 at 18:39

JayJay

35.6k3 gold badges57 silver badges105 bronze badges

Enclose a word in double quotation marks if it is referred to as a word rather than used in the sentence to express meaning.

answered Jan 25, 2015 at 21:47

1

When writing, I sometimes want to refer to a word, as opposed to its meaning. For example: when correcting someone’s grammar or semantics (there versus their), or when pointing out exemplary vocabulary.

On websites like this, I can simply italicize the word in question.

Abjure is a good word.

This feature isn’t always available, though – notably in simple online chatrooms, and even in this website’s question titles.

I’ve been using quotation marks, but now I’ve started second-guessing myself.

«Abjure» is a good word.

Abjure is a good word.

Is there a good way to refer to a specific word without throwing off the reader?

Answer

There’s two types of solutions that I can think of:

- Change the expression of the word to indicate that you refer to the word, e.g. by change of type (italics, small caps, etc.) or by enclosing it in some symbols (quotation marks).

- Explicitly state that you refer to the word, e.g. “The word Abjure is a good word.”

If you use the former solution I think it’s best to go with single quotation marks, e.g.

‘Abjure’ is a good word.

For reference Grammar girl says:

Use Single Quotation Marks to Highlight Words Not Being Used for Their

MeaningIt’s the convention in certain disciplines such as philosophy,

theology, and linguistics to highlight words with special meaning by

using single quotation marks instead of double quotation marks.

Attribution

Source : Link , Question Author : Maxpm , Answer Author : N.N.

Recently, there some was some confusion between myself and a coworker over the

definition of a “word.” I’m currently working on a blog post about data

alignment and figured it would be good to clarify some things now, that we can

refer to later.

Having studied computer engineering and being quite fond of processor design,

when I think of a “word,” I think of the number of bits wide a processor’s

general purpose registers are

(aka

word size).

This places hard requirements on the largest representable number and address

space. A 64 bit processor can represent 2^64-1 (1.8×10^19) as the largest

unsigned long integer, and address up to 2^64-1 (16 EiB) different addresses in

memory.

Further, word size limits the possible combinations of operations the processor

can perform, length of immediate values used, inflates the size of binary files

and memory needed to store pointers, and puts pressure on instruction caches.

Word size also has implications on loads and stores based on alignment, as

we’ll see in a follow up post.

When I think of 8 bit computers, I think of my first microcontroller: an

Arduino with an Atmel AVR processor. When I think of 16 bit computers, I think

of my first game console, a Super Nintendo with a Ricoh 5A22. When I think of

32 bit computers, I think of my first desktop with Intel’s Pentium III. And

when I think of 64 bit computers, I think modern smartphones with ARMv8

instruction sets. When someone mentions a particular word size, what are the

machines that come to mind for you?

So to me, when someone’s talking about a 64b processor, to that machine (and

me) a word is 64b. When we’re referring to a 8b processor, a word is 8b.

Now, some confusion.

Back in my previous blog posts about

x86-64 assembly,

JITs, or

debugging,

you might have seen me use instructions that have suffixes of b for byte (8b),

w for word (16b), dw for double word (32b), and qw for quad word (64b) (since

SSE2 there’s also double quadwords of 128b).

Wait a minute! How suddenly does a “word” refer to 16b on a 64b processor, as

opposed to a 64b “word?”

In short, historical baggage. Intel’s first hit processor was the

4004,

a 4b processor released in 1971. It wasn’t until 1979 that Intel created the

16b

8086 processor.

The 8086 was created to compete with other 16b processors that beat it to the

market, like the

Zilog Z80

(any Gameboy emulator fans out there? Yes, I know about the Sharp LR35902).

The 8086 was the first design in the

x86 family,

and it allowed for the same assembly syntax from the earlier 8008, 8080, and

8085 to be reassembled for it. The 8086’s little brother (8088) would be used

in

IBM’s PC,

and the rest is history. x86 would become one of the most successful

ISAs in history.

For backwards compatibility, it seems that both Microsoft’s (whose success has

tracked that of x86 since MS-DOS and IBM’s PC) and Intel’s documentation refers

to words still as being 16b. This allowed 16b PE32+ executables to be run on

32b or even 64b newer versions of Windows, without requiring recompilation of

source or source code modification.

This isn’t necessarily wrong to refer to a word based on backwards

compatibility, it’s just important to understand the context in which the term

“word” is being used, and that there might be some confusion if you have a

background with x86 assembly, Windows API programming, or processor design.

So the next time someone asks: why does Intel’s documentation commonly refer to

a “word” as 16b, you can tell them that the x86 and x86-64 ISAs have maintained

the notion of a word being 16b since the first x86 processor, the 8086, which

was a 16b processor.

Side Note: for an excellent historical perspective programming early x86

chips, I recommend Michael Abrash’s

Graphics Programming Black Book.

For instance he talks about 8086’s little brother, the 8088, being a 16b chip

but only having an 8b bus with which to access memory. This caused a mysterious

“cycle eater”

to prevent fast access to 16b variables, though they were the processor’s

natural size. Michael also alludes to alignment issues we’ll see in a follow

up post.

Word: The Definition & Criteria

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language. Words can be classified according to their action and meaning, but it is challenging to define.

A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Example : ‘love’, ‘cricket’, ‘sky’ etc.

«[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Morphology, a branch of linguistics, studies the formation of words. The branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words is called lexical semantics.

See More:

Online English Grammar Course

Free Online Exercise of English Grammar

There are several criteria for a speech sound, or a combination of some speech sounds to be called a word.

- There must be a potential pause in speech and a space in written form between two words.

For instance, suppose ‘ball’ and ‘bat’ are two different words. So, if we use them in a sentence, we must have a potential pause after pronouncing each of them. It cannot be like “Idonotplaywithbatball.” If we take pause, these sounds can be regarded as seven distinct words which are ‘I,’ ‘do,’ ‘not,’ ‘play,’ ‘with,’ ‘bat,’ and ‘ball.’ - Every word must contain at least one root. If you break this root, it cannot be a word anymore.

For example, the word ‘unfaithful’ has a root ‘faith.’ If we break ‘faith’ into ‘fa’ and ‘ith,’ these sounds will not be regarded as words. - Every word must have a meaning.

For example, the sound ‘lakkanah’ has no meaning in the English language. So, it cannot be an English word.

A word is a unit of language that carries meaning and consists of one or more morphemes which are linked more or less tightly together, and has a phonetic value. Typically a word will consist of a root or stem and zero or more affixes. Words can be combined to create phrases, clauses, and sentences. A word consisting of two or more stems joined together form a compound. A word combined with another word or part of a word form a portmanteau.

Etymology

English ‘ is directly from Old English «word», and has cognates in all branches of Germanic (Old High German «wort», Old Norse «orð», Gothic «waurd»), deriving from Proto-Germanic «*wurđa», continuing a virtual PIE «PIE|*wr̥dhom«. Cognates outside Germanic include Baltic (Old Prussian «wīrds» «word», and with different ablaut Lithuanian » var̃das» «name», Latvian «vàrds» «word, name») and Latin ‘. The PIE stem «PIE|*werdh-» is also found in Greek ερθει (φθεγγεται «speaks, utters» Hes. ). The PIE root is «PIE|*ŭer-, ŭrē-» «say, speak» (also found in Greek ειρω, ρητωρ). [Jacob Grimm, «Deutsches Wörterbuch»]

The original meaning of «word» is «utterance, speech, verbal expression». [OED, sub I. 1-11.] Until Early Modern English, it could more specifically refer to a name or title. [OED, sub II. 12 b. (a)]

The technical meaning of «an element of speech» first arises in discussion of grammar (particularly Latin grammar), as in the prologue to Wyclif’s Bible (ca. 1400)::»This word «autem», either «vero», mai stonde for «forsothe», either for «but».» [OED meaning II. 12 a.]

Definitions

Depending on the language, words can be difficult to identify or delimit. Dictionaries take upon themselves the task of categorizing a language’s lexicon into lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the authors.

Word boundaries

In spoken language, the distinction of individual words is usually given by rhythm or accent, but short words are often run together. See clitic for phonologically dependent words. Spoken French has some of the features of a polysynthetic language: «il y est allé» («He went there») is pronounced /IPA|i.ljɛ.ta.le/. As the majority of the world’s languages are not written, the scientific determination of word boundaries becomes important.

There are five ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:;Potential pause:A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words.;Indivisibility:A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, «I have lived in this village for ten years» might become «I and my family have lived in this little village for about ten or so years». These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes; in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an,» the noun «ankommen» is separated.;Minimal free forms:This concept was proposed by Leonard Bloomfield. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves. This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms, as they make no sense by themselves (for example, «the» and «of»).;Phonetic boundaries:Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish): the vowels within a given word share the same «quality», so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. However, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.;Semantic units:Much like the above mentioned minimal free forms, this method breaks down a sentence into its smallest semantic units. However, language often contains words that have little semantic value (and often play a more grammatical role), or semantic units that are compound words.

;A further criterion. Pragmatics. As Plag suggests, the idea of a lexical item being considered a word should also adjust to pragmatic criteria. The word «hello, for example, does not exist outside of the realm of greetings being difficult to assign a meaning out of it. This is a little more complex if we consider «how do you do?»: is it a word, a phrase, or an idiom? In practice, linguists apply a mixture of all these methods to determine the word boundaries of any given sentence. Even with the careful application of these methods, the exact definition of a word is often still very elusive.

There are some words that seem very general but may truly have a technical definition, such as the word «soon,» usually meaning within a week.

Orthography

In languages with a literary tradition, there is interrelation between orthography and the question of what is considered a single word.

Word separators (typically space marks) are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts,but these are (excepting isolated precedents) a modern development (see also history of writing).

In English orthography, words may contain spaces if they are compounds or proper nouns such as «ice cream» or «air raid shelter».

Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes, not words. Conversely, synthetic languages often combine many lexical morphemes into single words, making it difficult to boil them down to the traditional sense of words found more easily in analytic languages; this is especially difficult for polysynthetic languages such as Inuktitut and Ubykh, where entire sentences may consist of single such words.

Logographic scripts use single signs (characters) to express a word. Most «de facto» existing scripts are however partly logographic, and combine logographic with phonetic signs. The most widespreadlogographic script in modern use is the Chinese script. While the Chinese script has some true logographs, the largest class of characters used in modern Chinese (some 90%) are so-called pictophonetic compounds ( _zh. 形声字, _pn. Xíngshēngzì). Characters of this sort are composed of two parts: a pictograph, which suggests the general meaning of the character, and a phonetic part, which is derived from a character pronounced in the same way as the word the new character represents. In this sense, the character for most Chinese words consists of a determiner and a syllabogram, similar to the approach used by cuneiform script and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

There is a tendency informed by orthography to identify a single Chinese character as corresponding to a single word in the Chinese language, parallel to the tendency to identify the letters between two space marks as a single word in the English language. In both cases, this leads to the identification of compound members as individual words, while e.g. in German orthography, compound members are not separated by space marks and the tendency is thus to identify the entire compound as a single word. Compare e.g. English «capital city» with German «Hauptstadt» and Chinese 首都 (lit. ): all three are equivalent compounds, in the English case consisting of «two words» separated by a space mark, in the German case written as a «single word» without space mark, and in the Chinese case consisting of two logographic characters.

Morphology

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, «love») may have a number of different forms (for example, «loves», «loving», and «loved»). However, these are not usually considered to be different words, but different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are

*the root

*optional suffixes

*a desinence.Thus, the Proto-Indo-European «PIE|*wr̥dhom» would be analysed as consisting of

#»PIE|*wr̥-«, the zero grade of the root «PIE|*wer-»

#a root-extension «PIE|*-dh-» (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root «PIE|*wr̥dh-«

#The thematic suffix «PIE|*-o-«

#the neuter gender nominative or accusative singular desinence «PIE|*-m«.

Classes

Grammar classifies a language’s lexicon into several groups of words. The basic bipartite division possible for virtually every natural language is that of nouns vs. verbs.

The classification into such classes is in the tradition of Dionysius Thrax, who distinguished eight categories: noun, verb, adjective, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction and interjection.

In Indian grammatical tradition, Panini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of desinences taken by the word.

References

*Bauer, L. (1983) English Word Formation. Cambridge. CUP.

*Brown, Keith R. (Ed.) (2005) Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Elsevier. 14 vols.

*Crystal, D. (1995) The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

*Plag, Ingo.(2003) Word formation in English. CUP

ee also

*Grammar

*Utterance

*Morphology

*Lexeme

*Lexicon

*Lexis (linguistics)

*Lexical item

External links

* [http://www.sussex.ac.uk/linguistics/documents/essay_-_what_is_a_word.pdf What Is a Word?] — a working paper by Larry Trask, Department of Linguistics and English Language, University of Sussex.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

There are different ways to format and cite a word and definition according to different manuals of style. The main thing to do is be consistent.

What are some general rules for formatting?

It is important to offset the term that is being defined or discussed, usually by italicizing it (underline it if you can’t). This is to prevent any confusion that might occur if the term is one that might be mistaken for a word that is simply functioning as part of the sentence as opposed to being discussed as a word.

If you are using any foreign language terms or phrases in your writing, standard practice dictates they be italicized. Some confusion can result if foreign terms and words under analysis are italicized but are not actually being cited.

Do not capitalize the word unless it is a proper noun or falls at the beginning of a sentence.

The definition should be enclosed in quotation marks.

Some examples:

- Pendulous can mean “hanging down loosely,” “swinging freely,” or “wavering.”

- Emilia reminded us that bossy is often considered sexist.

- Doing good in the world was his raison d’être.

What does the Chicago Manual of Style say?

One leading style guide is the Chicago Manual of Style, commonly referred to as Chicago style. According to its 17th edition (University of Chicago, 2017):

- When a word or phrase is used as a word (i.e., not used functionally but referred to as the word or term itself), it is either italicized or enclosed in quotation marks.

- A translation of a foreign word or phrase (in italics) should be enclosed in quotation marks or parentheses.

The main principle is that both the word and its definition need to be set in either a different type (usually italics) or set inside punctuation marks (usually quotations marks or parentheses) so that they can be distinguished from the rest of the text.

How do you cite a definition from Dictionary.com in Chicago style?

If you cite a definition of a word you looked up on Dictionary.com and need to include it in your references, the basic format is as follows, exemplified by the word hangry:

Dictionary.com, s.v., “hangry,” accessed June 17, 2019, https://www.diction-ary.com/hangry.

Note s.v., which stands for sub verbo (under the word). The date accessed refers to the date you looked up the term, and the URL included is the link to the entry online.

Word for Microsoft 365 Word 2021 Word 2019 Word 2016 Word 2013 Word 2010 Word 2007 More…Less

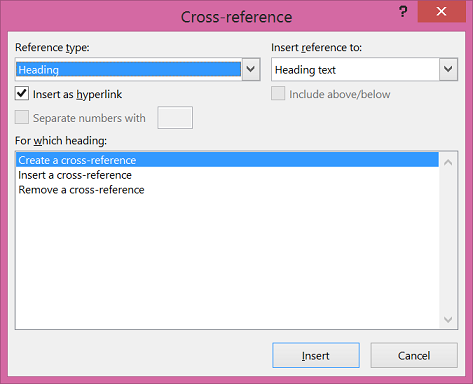

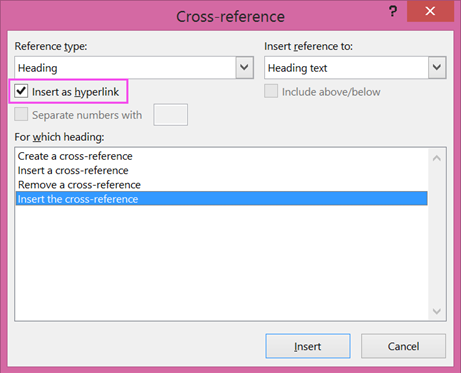

A cross-reference allows you to link to other parts of the same document. For example, you might use a cross-reference to link to a chart or graphic that appears elsewhere in the document. The cross-reference appears as a link that takes the reader to the referenced item.

If you want to link to a separate document you can create a hyperlink.

Create the item you’re cross-referencing first

You can’t cross-reference something that doesn’t exist, so be sure to create the chart, heading, page number, etc., before you try to link to it. When you insert the cross-reference, you’ll see a dialog box that lists everything that’s available to link to. Here’s an example.

Insert the cross-reference

-

In the document, type the text that begins the cross-reference. For example, «See Figure 2 for an explanation of the upward trend.»

-

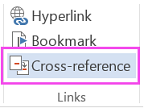

On the Insert tab, click Cross-reference.

-

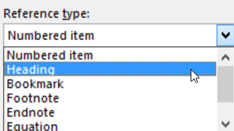

In the Reference type box, click the drop-down list to pick what you want to link to. The list of what’s available depends on the type of item (heading, page number, etc.) you’re linking to.

-

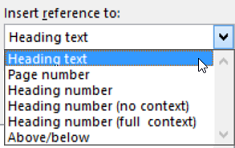

In the Insert reference to box, click the information you want inserted in the document. Choices depend on what you chose in step 3.

-

In the For which box, click the specific item you want to refer to, such as «Insert the cross-reference.»

-

To allow users to jump to the referenced item, select the Insert as hyperlink check box.

-

If the Include above/below check box is available, check it to include specify the relative position of the referenced item.

-

Click Insert.

Cross-references are inserted as fields

Cross-references are inserted into your document as fields. A field is a set of information that instructs Word to insert text, graphics, page numbers, and other material into a document automatically. For example, the DATE field inserts the current date. The advantage of using fields is that the content being inserted—date, page number, graphics, etc.—gets updated for you whenever there’s a change. For example, if you’re writing a document over a period of days, the date will change each day when you open and save the document. Similarly, if you update a graphic that’s stored elsewhere but referenced in the field, the update will get picked up automatically without you having to re-insert the graphic.

If you’ve inserted a cross-reference and it looks similar to {REF _Ref249586 * MERGEFORMAT}, then Word is displaying field codes instead of field results. When you print the document or hide field codes, the field results replace the field codes. To see the field results instead of field codes, press ALT+F9, or right-click the field code, and then click Toggle Field Codes on the shortcut menu.

Use a master document

If you want to cross-reference items that reside in a separate document but don’t want to use hyperlinks, you’ll have to first combine the documents into one master document and then insert the cross-references. A master document is a container for a set of separate files (or subdocuments). You can use a master document to set up and manage a multi-part document, such as a book with several chapters.

Need more help?

|

WordReference Random House Learner’s Dictionary of American English © 2023 word /wɜrd/USA pronunciation

v. [~ + object]

Idioms

WordReference Random House Unabridged Dictionary of American English © 2023 word

v.t.

interj.

Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers:: word /wɜːd/ n

vb

WordReference Random House Unabridged Dictionary of American English © 2023 WH-word

Also, wh- word. Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers:: Word /wɜːd/ n the Word ⇒

Etymology: translation of Greek logos, as in John 1:1 Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers:: -word n combining form

‘word‘ also found in these entries (note: many are not synonyms or translations): |

|