Syllables Quiz

palatalization

925467381 syllables

Divide palatalization into syllables: pal-a-tal-i-za-tion

How to say palatalization:

Cite This Source

Bibliography Citations

MLA | APA | Chicago Manual Style

«palatalization.» HowManySyllables.com. How Many Syllables, n.d. Web. 14 April 2023.

Learn a New Word

Wondering why palatalization is 925467381 syllables? Contact Us! We’ll explain.

Syllable Quiz

Can you divide

our into syllables?

Fun Fact

Stewardesses is typed using

only the left hand.

FAQ

Why is our only

1 syllable?

Do You Know

when you should use

Was and Were?

Parents, Teachers, StudentsDo you have a grammar question?

Need help finding a syllable count?

Want to say thank you?

Contact Us!

Advertisements

Word

Palatalization

How many syllables?

6 Syllables

How it’s divided?

pal-a-tal-i-za-tion

Advertisements

Other 6 Syllable Words

nonexcitatory

monotheistical

physicochemical

spermiogenesis

dithyrambically

ratificationist

indiscretionary

nondomesticating

electromagnetist

meritoriousness

chordamesodermic

retractability

thermoelectronic

conceptualising

undefeatableness

6 Syllable Words Starting with?

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

t

u

v

w

x

y

z

Syllable Of The Day

rigatoni

ri-ga-to-ni

This word has 4 syllables.

Advertisements

Website Statistics

150.7K

words

504.2K

syllables

649.4K

definitions

Decomposition of palatalization into syllables

There are many reasons to learn how to divide palatalization into syllables. Separating a word like palatalization into syllables is mainly to make it easier to read and pronounce. The syllable is the smallest sound unit in a word, and the separation of the palatalization into syllables allows speakers to better segment and emphasize each sound unit.

Reasons for separating palatalization into syllables

Knowing how to separate palatalization into syllables can be especially useful for those learning to read and write, because it helps them understand and pronounce palatalization more accurately. Furthermore, separating palatalization into syllables can also be useful in teaching grammar and spelling, as it allows students to more easily understand and apply the rules of accentuation and syllable division.

How many syllables are there in palatalization?

In the case of the word palatalization, we find that when separating into syllables the resulting number of syllables is 3. With this in mind, it’s much easier to learn how to pronounce palatalization, as we can focus on perfecting the syllabic pronunciation before trying to pronounce palatalization in full or within a sentence. Likewise, this breakdown of palatalization into syllables makes it easier for us to remember how to write it.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Palatalized | |

|---|---|

| ◌ʲ | |

| IPA Number | 421 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ʲ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02B2 |

In phonetics, palatalization (, also ) or palatization is a way of pronouncing a consonant in which part of the tongue is moved close to the hard palate. Consonants pronounced this way are said to be palatalized and are transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet by affixing the letter ⟨ʲ⟩ to the base consonant. Palatalization cannot minimally distinguish words in most dialects of English, but it may do so in languages such as Russian, Mandarin, and Irish.

Types[edit]

In technical terms, palatalization refers to the secondary articulation of consonants by which the body of the tongue is raised toward the hard palate and the alveolar ridge during the articulation of the consonant. Such consonants are phonetically palatalized. «Pure» palatalization is a modification to the articulation of a consonant, where the middle of the tongue is raised, and nothing else. It may produce a laminal articulation of otherwise apical consonants such as /t/ and /s/.

Phonetically palatalized consonants may vary in their exact realization. Some languages add semivowels before or after the palatalized consonant (onglides or offglides). In Russian, both plain and palatalized consonant phonemes are found in words like большой [bɐlʲˈʂoj] (listen), царь [tsarʲ] (

listen) and Катя [ˈkatʲə] (

listen). Typically, the vowel (especially a non-front vowel) following a palatalized consonant has a palatal onglide. In Hupa, on the other hand, the palatalization is heard as both an onglide and an offglide. In some cases, the realization of palatalization may change without any corresponding phonemic change. For example, according to Thurneysen,[full citation needed] palatalized consonants at the end of a syllable in Old Irish had a corresponding onglide (reflected as ⟨i⟩ in the spelling), which was no longer present in Middle Irish (based on explicit testimony of grammarians of the time).

In a few languages, including Skolt Sami and many of the Central Chadic languages, palatalization is a suprasegmental feature that affects the pronunciation of an entire syllable, and it may cause certain vowels to be pronounced more front and consonants to be slightly palatalized. In Skolt Sami and its relatives (Kildin Sami and Ter Sami), suprasegmental palatalization contrasts with segmental palatal articulation (palatal consonants).

Transcription[edit]

In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), palatalized consonants are marked by the modifier letter ⟨ʲ⟩, a superscript version of the symbol for the palatal approximant ⟨j⟩. For instance, ⟨tʲ⟩ represents the palatalized form of the voiceless alveolar stop [t]. Prior to 1989, a subscript diacritic (⟨ᶀ ꞔ ᶁ ᶂ ᶃ ꞕ ᶄ ᶅ ᶆ ᶇ ᶈ ᶉ ᶊ ƫ ᶌ ᶍ ᶎ⟩) and several palatalized consonants were represented by curly-tailed variants in the IPA, e.g., ⟨ʆ⟩ for [ʃʲ] and ⟨ʓ⟩ for [ʒʲ]: see palatal hook. The Uralic Phonetic Alphabet marks palatalized consonants by an acute accent, as do some Finnic languages using the Latin alphabet, as in Võro ⟨ś⟩. Others use an apostrophe, as in Karelian ⟨s’⟩; or digraphs in j, as in the Savonian dialects of Finnish, ⟨sj⟩.

Phonology[edit]

Palatalization has varying phonological significance in different languages. It is allophonic in English, but phonemic in others. In English, consonants are palatalized when they occur before front vowels or the palatal approximant, but no words are distinguished by palatalization (complementary distribution), whereas in some of the other languages, the difference between palatalized consonants and plain un-palatalized consonants distinguish between words, appearing in a contrastive distribution (where one of the two versions palatalized or not, appears in the same environment as the other).

Allophonic palatalization[edit]

In some languages, like English, palatalization is allophonic. Some phonemes have palatalized allophones in certain contexts, typically before front vowels and unpalatalized allophones elsewhere. Because it is allophonic, palatalization of this type does not distinguish words and often goes unnoticed by native speakers. Phonetic palatalization occurs in American English. Stops are palatalized before the front vowel /i/ and not palatalized in other cases.

Phonemic palatalization[edit]

In some languages, palatalization is a distinctive feature that distinguishes two consonant phonemes. This feature occurs in Russian, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic, among others.

Phonemic palatalization may be contrasted with either plain or velarized articulation. In many of the Slavic languages, and some of the Baltic and Finnic languages, palatalized consonants contrast with plain consonants, but in Irish they contrast with velarized consonants.

- Russian нос

/nos/ «nose» (unpalatalized /n/)

- нёс

/nʲos/ «(he) carried» (palatalized /nʲ/)

- Irish bó

/bˠoː/ «cow» (velarized b)

- beo

/bʲoː/ «alive» (palatalized b)

Some palatalized phonemes undergo change beyond phonetic palatalization. For instance, the unpalatalized sibilant (Irish /sˠ/, Scottish /s̪/) has a palatalized counterpart that is actually postalveolar [ʃ], not phonetically palatalized [sʲ], and the velar fricative /x/ in both languages has a palatalized counterpart that is actually palatal [ç] rather than palatalized velar [xʲ]. These shifts in primary place of articulation are examples of the sound change of palatalization.

Morphophonemic[edit]

In some languages, palatalization is used as a morpheme or part of a morpheme. In some cases, a vowel caused a consonant to become palatalized, and then this vowel was lost by elision. Here, there appears to be a phonemic contrast when analysis of the deep structure shows it to be allophonic.

In Romanian, consonants are palatalized before /i/. Palatalized consonants appear at the end of the word, and mark the plural in nouns and adjectives, and the second person singular in verbs.[1] On the surface, it would appear then that ban [ban] «coin» forms a minimal pair with bani [banʲ]. The interpretation commonly taken, however, is that an underlying morpheme |-i| palatalizes the consonant and is subsequently deleted.

Palatalization may also occur as a morphological feature. For example, although Russian makes phonemic contrasts between palatalized and unpalatalized consonants, alternations across morpheme boundaries are normal:[2]

Sound changes[edit]

In some languages, allophonic palatalization developed into phonemic palatalization by phonemic split. In other languages, phonemes that were originally phonetically palatalized changed further: palatal secondary place of articulation developed into changes in manner of articulation or primary place of articulation.

Phonetic palatalization of a consonant sometimes causes surrounding vowels to change by coarticulation or assimilation. In Russian, «soft» (palatalized) consonants are usually followed by vowels that are relatively more front (that is, closer to [i] or [y]), and vowels following «hard» (unpalatalized) consonants are further back. See Russian phonology § Allophony for more information.

Examples[edit]

Slavic languages[edit]

In many Slavic languages, palatal or palatalized consonants are called soft, and others are called hard. Some of them, like Russian, have numerous pairs of palatalized and unpalatalized consonant phonemes.

Russian Cyrillic has pairs of vowel letters that mark whether the consonant preceding them is hard/soft:

⟨а⟩/⟨я⟩,

⟨э⟩/⟨е⟩,

⟨ы⟩/⟨и⟩,

⟨о⟩/⟨ё⟩, and

⟨у⟩/⟨ю⟩.

The otherwise silent soft sign ⟨ь⟩ also indicates that the previous consonant is soft.

Goidelic[edit]

Irish and Scottish Gaelic have pairs of palatalized (slender) and unpalatalized (broad) consonant phonemes. In Irish, most broad consonants are velarized. In Scottish Gaelic, the only velarized consonants are [n̪ˠ] and [l̪ˠ]; [r] is sometimes described as velarized as well.[3][4]

Mandarin Chinese[edit]

Palatalized consonants occur in standard Mandarin Chinese in the form of the alveolo-palatal consonants, which are written in pinyin as j, q, and x.

Marshallese[edit]

In the Marshallese language, each consonant has some type of secondary articulation (palatalization, velarization, or labiovelarization). The palatalized consonants are regarded as «light», and the velarized and rounded consonants are regarded as «heavy», with the rounded consonants being both velarized and labialized.

Norwegian[edit]

Many Norwegian dialects have phonemic palatalized consonants. In many parts of Northern Norway and many areas of Møre og Romsdal, for example, the words /hɑnː/ (‘hand’) and /hɑnʲː/ (‘he’) are differentiated only by the palatalization of the final consonant. Palatalization is generally realised only on stressed syllables, but speakers of the Sør-Trøndelag dialects will generally palatalize the coda of a determined plural as well: e.g. /hunʲː.ɑnʲ/ or, in other areas, /hʉnʲː.ɑn/ (‘the dogs’), rather than */hunʲː.ɑn/. Norwegian dialects utilizing palatalization will generally palatalize /d/, /l/, /n/ and /t/.

See also[edit]

- Iotation, a related process in Slavic languages

- Soft sign, a Cyrillic grapheme indicating palatalization

- Manner of articulation

- List of phonetics topics

- Labio-palatalization

- Yōon

References[edit]

- ^ Chițoran (2001:11)

- ^ See Lightner (1972:9–11, 12–13) for a fuller list of examples.

- ^ Bauer, Michael. Blas na Gàidhlig: The Practical Guide to Gaelic Pronunciation. Glasgow: Akerbeltz, 2011.

- ^ Nance, C., McLeod, W., O’Rourke, B. and Dunmore, S. (2016), Identity, accent aim, and motivation in second language users: New Scottish Gaelic speakers’ use of phonetic variation. J Sociolinguistics, 20: 164–191. doi:10.1111/josl.12173

Bibliography[edit]

- Bynon, Theodora. Historical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-521-21582-X (hardback) or ISBN 978-0-521-29188-0 (paperback).

- Bhat, D.N.S. (1978), «A General Study of Palatalization», Universals of Human Language, 2: 47–92

- Buckley, E. (2003), «The Phonetic Origin and Phonological Extension of Gallo-Roman Palatalization», Proceedings of the North American Phonology Conferences 1 and 2, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.81.4003

- Chițoran, Ioana (2001), The Phonology of Romanian: A Constraint-based Approach, Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-016766-2

- Crowley, Terry. (1997) An Introduction to Historical Linguistics. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press.

- Lightner, Theodore M. (1972), Problems in the Theory of Phonology, I: Russian phonology and Turkish phonology, Edmonton: Linguistic Research, inc

- Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Ladusaw, William A. (1996). Phonetic Symbol Guide. University of Chicago Press.

External links[edit]

- Erkki Savolainen, Internetix 1998. Suomen murteet – Koprinan murretta. (with a sound sample with palatalized t’)

- Frisian assibilation as a hypercorrect effect due to a substrate language

| Palatalized | |

|---|---|

| ◌ʲ | |

| IPA number | 421 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ʲ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02B2 |

|

view · talk · edit |

| Sound change and alternation |

|---|

|

Metathesis Quantitative metathesis |

|

Lenition Consonant gradation |

| Fortition |

|

Epenthesis Anaptyxis |

|

Elision Apheresis |

|

Cheshirization Compensatory lengthening |

|

Assimilation Coalescence |

| Dissimilation |

|

Sandhi Liaison, linking R Synalepha Elision |

|

Other types Rhotacism |

|

view |

In linguistics, palatalization ( /ˌpælətəlɨˈzeɪʃən/), also palatization, may refer to two different processes by which a sound, usually a consonant, comes to be produced with the tongue in a position in the mouth near the palate.

In describing the phonetics of an existing language (i.e., in synchronic descriptions), a palatalized consonant is one pronounced with a palatal secondary articulation. This means that the consonant is pronounced as if followed very closely by the sound [j] (a palatal approximant, like the sound of «y» in «yellow»). For example, in the Polish word kiedy («when»), the letters ki represent a palatalized [k], indicated in IPA notation as [kʲ], with a superscript «j». This sound is similar to the combination of «k» and «y» in English «thank you».

The other meaning of palatalization is encountered in historical linguistics, and refers to a sound change in which a consonant’s place of articulation becomes closer to the palatal position. This change is often triggered by a following [j] sound or a front vowel. For example, in Italian, before the front vowels e and i, the letter c (which otherwise represents [k], a velar consonant), has come to be pronounced as the palato-alveolar consonant [tʃ], like English «ch» (see [hard and soft c]]).

Palatalization of both types is widespread across languages in the world, though its actual manifestation varies. In some languages, such as the Slavic languages, palatal or palatalized consonants are frequently referred to as soft consonants, with others called hard consonants.

The term palatalized vowel is also sometimes used, to refer to a vowel that has become fronter or closer.

Contents

- 1 Types

- 2 Phonetics

- 3 Phonology

- 3.1 Mechanism

- 3.2 Historical (diachronic) palatalization

- 3.2.1 Examples

- 3.3 Synchronic palatalization

- 4 Local uses of the word

- 5 See also

- 6 References

- 7 Bibliography

- 8 Notes

- 9 External links

Types

In technical terms, palatalization refers to one of several things:

- A phonetic term of the secondary articulation of consonants by which the body of the tongue is raised toward the hard palate and the alveolar ridge during the articulation of the consonant. Such consonants are phonetically palatalized, and in the International Phonetic Alphabet they are indicated by a superscript ⟨j⟩, as with [tʲ] for a palatalized [t].[nb 1]

- A common assimilatory process or the result of such a process, which involves front vowels (that is, sounds with a higher second formant such as [i] and [e]) and/or the palatal approximant [j] causing nearby phones to shift towards (though not necessarily coming to) the palatal articulatory position or to positions closer to the front of the mouth.

The first may be the result of the second, but they are often different. A vowel may «palatalize» a consonant (sense 2), but the result might not be a palatalized consonant in the phonetic sense (sense 1), or the phonetically palatalized (sense 1) consonant may occur irrespective of adjacency to front vowels.

The word «palatalization» may also be used for the effect a palatal or palatalized consonant exerts on nearby sounds, as in the history of Old French where Bartsch’s law turned low vowels into [e] or [ɛ] after a palatalized velar consonant, or in the Uralic language Erzya, where the near-open low front unrounded vowel [æ] only occurs as an allophone of the open vowel [a] after a palatalized consonant, as seen in the pronunciation of the name of the language itself, [erzʲæ]. Something similar may have been the case for some or even all low vowels in Old French, which could explain the palatalization of almost all velar plosives before /a/.[1] However, while the process may be called palatalization, the resulting vowel [æ] is not called a palatalized vowel in the phonetic sense. Terminology such as «palatal vowel» is found, but this is primary and not secondary articulation.

Phonetics

«Pure» palatalization is denoted by a small superscript ⟨ʲ⟩ in IPA. This is a modification to the articulation of a consonant, where the middle of the tongue is raised, and nothing else. It may produce a laminal articulation of otherwise apical consonants such as /t/ and /s/. It is a phonemic feature in some languages; a common misconception is that it is merely allophonic, like in English. Phonemic palatalization may be contrasted with either plain or velarized articulation. In Finnic languages, Baltic languages and Slavic languages, the contrast is with plain consonants, but in Irish, it is with velarized consonants.

Phonetically palatalized consonants may vary in their exact realization. Some, but not all languages add offglides or onglides. In Russian, both plain and palatalized consonant phonemes are found in words like пальто [pɐˈlʲto], царь [tsarʲ] and Катя [ˈkatʲə]. Typically, the vowel (especially a non-front vowel) following a palatalized consonant has a palatal offglide. In Hupa, on the other hand, the palatalization is heard as both an onglide and an offglide. In some cases, the realization of palatalization may change without any corresponding phonemic change. For example, according to Thurneysen,[Full citation needed] palatalized consonants at the end of a syllable in Old Irish had a corresponding onglide (reflected as ⟨i⟩ in the spelling), which was no longer present in Middle Irish (based on explicit testimony of grammarians of the time period).

Palatalization can also occur as a suprasegmental feature that affects the pronunciation of an entire syllable. This is the case in Skolt Sami, a language which is unusual in contrasting suprasegmental palatalization with segmental palatalization (i.e., inherently palatalized consonants).

Phonology

Mechanism

Palatalization is usually triggered only by mid, close (high) front vowels and the semi-vowel [j]; but counterexamples to this are also found. In addition, tongue-fronting )a process mainly induced by front vowels) typically affects velar consonants, while tongue-raising typically affects apical and coronal consonants. On the other hand, most of the palatalized consonants also undergo spirantization, except for the palatalized labials.[citation needed]

In Gallo-Romance, Vulgar Latin *[ka] became *[tʃa] very early, with the subsequent deaffrication and some further developments of the vowel. For instance:

- *cattus (‘cat’) → chat /ʃa/

- calvus (‘bald’) → chauve /ʃov/

- *blanca (‘white’ fem.) → blanche /blɑ̃ʃ/

- catena (‘chain’) → chaine /ʃɛn/

- carus (‘dear’) → cher /ʃɛʁ/

Early English borrowings from French show the original affricate, as chamber (‘[private] room’) < Old French chambre < camera; cf French chambre /ʃɑ̃bʁ/ (‘room’)

Historical (diachronic) palatalization

Palatalization may result in a phonemic split, that is, a historical change by which a phoneme becomes two new phonemes over time through phonetic palatalization.

Old historical splits have frequently drifted since the time they occurred, and may be independent of current phonetic palatalization. The lenition tendency of palatalized consonants (by assibilation and deaffrication) is important here. According to some analyses,[2] the lenition of the palatalized consonant is still a part of the palatalization process itself.

For example, Votic has undergone such a change historically, in for example *keeli → tšeeli (‘language’), but there is currently an additional distinction between palatalized laminal and non-palatalized apical consonants. An extreme example occurs in Spanish, where palatalized (‘soft’) g has ended up as [x]; this results from a long process where /ɡ/ became palatalized to [ɡʲ], then assibilated to [dʒ], deaffricated to [ʒ], devoiced to [ʃ] shifted back to the velar place of articulation (See History of Spanish and ceceo for more information).

While the great majority of palatalization effects are connected with sequences with a consonant adjacent to a high front or mid front vowel or glide, palatalization may occur spontaneously in a sense. In Southwestern Romance, /l/ in word-initial clusters with a voiceless obstruent became palatalized, as Latin clamare (‘to call’) → Italian chiamare /kjamare/ and Old Portuguese chamar; in Spanish, the obstruent drops before the palatalized liquid: llamar /ʎamar/. Differently, in an even larger area, Latin *[kt] became *[kʲt] (or even *[kʲtʲ]), thus from a form like Latin octō (‘eight’) comes French huit, Spanish ocho, and Portuguese oito /oitu/.

Such phonemic splits due to historic palatalization are common in many other languages. Some English examples of cognate words distinguished by historical palatalization are church vs. kirk, witch vs. wicca, ditch vs. dike, and shirt vs. skirt. The pronunciation of wicca as [ˈwɪkə] is a spelling pronunciation based on unfamiliarity with Old English spelling conventions (wicca was presumably [ˈwɪtʃːa] < *wikjā ); in the other cases, the words come from related dialects or languages (skirt from Danish) which differed in the place and degree of palatalization. More recently, the original /t/ of question and nature have come to be pronounced [tʃ] before [j] in a number of English dialects, and the original /d/ of soldier and procedure have come to be [dʒ]. This effect can also be seen in casual speech in some dialects, where Do you want to go? comes out as [dʒuː ˈwʌnə ɡoʊ], and Did you eat yet? as [ˈdɪdʒə ˈiːtʃɛt].

Examples

Palatalization has played a major role in the history of English in addition to the Uralic, Romance, Slavic, Goidelic, Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Twi, Micronesian languages and Indic languages, among many others throughout the world. In pre-Old English, for example (c. 400 AD), palatalization produced new phonemes /tʃ/, /dʒ/ and /ʃ/, along with many new cases of /j/. Palatal/non-palatal alternations from this time are still visible in pairs such as speak vs. speech, and less obviously in day vs. dawn. A more recent palatalization (c. 1600 AD) has produced extensive alternations, as in close /z/ vs. closure /ʒ/, face /s/ vs. facial /ʃ/, -ate /t/ vs. -ature /tʃ/, etc.

In Japanese, allophonic palatalization affected the dental plosives /t/ and /d/, turning them into alveolo-palatal affricates [tɕ] and [dʑ] before [i]. Japanese has only recently regained phonetic [ti] and [di] through borrowed words, and thus this originally allophonic palatalization has become lexical. A similar change has also happened in Polish and Belarusian.

In some Zoque languages, [j] does not palatalize velar consonants while it does turn alveolars into palato-alveolars. In the Nupe language, /s/ and /z/ are palatalized both before front vowels and /j/, while velars are only palatalized before front vowels. In Ciluba, /j/ palatalizes only a preceding /t/, /s/, /l/ or /n/. In some variants of Ojibwe velars are palatalized before /j/, while apicals are not. In Indo-Aryan languages, dentals and /r/ are palatalized when occurring in clusters before /j/ while velars are not.

Synchronic palatalization

Palatalization may be a synchronic phonological process, i.e., some phonemes have palatalized allophones in certain contexts, typically before front vowels, and unpalatalized allophones elsewhere. Because it is allophonic, it often goes unnoticed by native speakers. As an example, compare the /k/ of English key with that of of coo, or tea with took. The consonant in the first word of each pair is palatalized, but few English speakers would perceive them as distinct.

The process gets complicated when other phonological and morphological processes that delete the palatalizing sound, such as syncope or elision, make the surface realization appear to be a phonemic contrast when analysis of the deep structure shows it to be allophonic. For example, Romanian consonants are palatalized before /i/. Palatalized consonants also appear terminally as the manifestation of certain morphological markers, particularly to indicate plurality in nouns and adjectives and the second person singular in verbs.[3] On the surface, it would appear then that ban [ban] (‘coin’) forms a minimal pair with bani [banʲ] The interpretation commonly taken, however, is that an underlying morpheme |-i| palatalizes the consonant and is subsequently deleted.

Palatalization may also occur as a morphological process. For example, although Russian makes phonemic contrasts between palatalized and unpalatalized consonants, alternations across morpheme boundaries are normal:[4]

- ответ [ɐˈtvʲɛt] (‘answer’) vs. ответить [ɐˈtvʲetʲɪtʲ] (‘to answer’)

- несу [nʲɪˈsu] (‘I carry’) vs. несёт [nʲɪˈsʲot] (‘carries’)

- голод [ˈɡolət] (‘hunger’) vs. голоден [ˈɡolədʲɪn] (‘hungry’ masc.)

Local uses of the word

There are various other local or historical uses of the word. In Slavic linguistics, the «palatal» fricatives marked by a háček are really postalveolar consonants that arose from palatalization historically. There are also phonetically palatalized consonants (marked with an acute accent) that contrast with this; thus the distinction is made between «palatal» (postalveolar) and «palatalized». Such «palatalized» consonants are not always phonetically palatalized; e.g., in Russian, when /t/ undergoes palatalization, a palatalized sibilant offglide appears, as in тема [ˈtˢʲɛmə].

In Uralic linguistics, «palatalization» has the standard phonetic meaning. /s/, /sʲ/, /ʃ/, /t/, /tʲ/, /tʃ/ are distinct phonemes, as they are in the Slavic languages, but /ʃ/ and /tʃ/ are not considered either palatal or palatalized sounds. Also, the Uralic palatalized /tʲ/ is a stop with no frication, unlike in Russian.

In using the Latin alphabet for Uralic languages, palatalization is typically denoted with an acute accent, as in Võro ⟨ś⟩; an apostrophe, as in Karelian ⟨s’⟩; or digraphs in j, as in the Savo dialect of Finnish, ⟨sj⟩. Postalveolars, in contrast, take a caron, ⟨š⟩, or are digraphs in ⟨h⟩, ⟨sh⟩.

See also

- Iotation, a form of palatalization in Slavic languages

- Soft sign, a Cyrillic alphabet grapheme indicating palatalization

- Manner of articulation

- List of phonetics topics

- Labio-palatalization

- Palatalization in Vulgar Latin

- Mouillé

References

- ^ Buckley (2003)

- ^ e.g. Bhat (1978)

- ^ Chițoran (2001:11)

- ^ See Lightner (1972:9–11, 12–13) for a fuller list of examples.

Bibliography

- Bynon, Theodora. Historical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-521-21582-X (hardback) or ISBN 978-0-521-29188-0 (paperback).

- Bhat, D.N.S. (1978), «A General Study of Palatalization», Universals of Human Language 2: 47–92

- Buckley, E. (2003), «The Phonetic Origin and Phonological Extension of Gallo-Roman Palatalization», Proceedings of the North American Phonology Conferences 1 and 2, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.81.4003&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Chițoran, Ioana (2001), The Phonology of Romanian: A Constraint-based Approach, Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 3110167662

- Crowley, Terry. (1997) An Introduction to Historical Linguistics. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press.

- Lightner, Theodore M. (1972), Problems in the Theory of Phonology, I: Russian phonology and Turkish phonology, Edmonton: Linguistic Research, inc

- Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Ladusaw, William A. (1996). Phonetic Symbol Guide. University of Chicago Press.

Notes

- ^ Prior to 1989, several palatalized consonants were represented by curly-tailed variants in the IPA, e.g., [ʆ] for [ʃʲ] and [ʓ] for [ʒʲ]. See also Palatal hook.

External links

- Erkki Savolainen, Internetix 1998. Suomen murteet – Koprinan murretta. (with a sound sample with palatalized t’)

- Frisian assibilation as a hypercorrect effect due to a substrate language

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

PRONUNCIATION OF PALATALIZATION

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF PALATALIZATION

Palatalization is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES PALATALIZATION MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Palatalization

In linguistics, palatalization /ˌpælətəlaɪˈzeɪʃən/ or palatization may refer to two different processes by which a sound, usually a consonant, comes to be produced with the tongue in a position in the mouth near the palate. In describing the phonetics of an existing language, a palatalized consonant is one pronounced with a palatal secondary articulation. This means that the consonant is pronounced as if followed very closely by the sound . For example, in the Polish word kiedy, the letters ki represent a palatalized, indicated in IPA notation as, with a superscript «j». This sound is similar to the combination of «k» and «y» in English «thank you». The other meaning of palatalization is encountered in historical linguistics, and refers to a sound change in which a consonant’s place of articulation becomes closer to the palatal position. This change is often triggered by a following sound or a front vowel. For example, in Italian, before the front vowels e and i, the letter c, has come to be pronounced as the palato-alveolar consonant, like English «ch».

Definition of palatalization in the English dictionary

The definition of palatalization in the dictionary is the pronunciation of consonants with the front of the tongue drawn up further toward the roof of the mouth than in their normal pronunciation.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH PALATALIZATION

Synonyms and antonyms of palatalization in the English dictionary of synonyms

Translation of «palatalization» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF PALATALIZATION

Find out the translation of palatalization to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of palatalization from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «palatalization» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

颚音

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

palatalization

570 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

palatalization

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

palatalization

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

палатализация

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

palatalization

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

palatalization

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Palatalisasi

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

palatalization

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

口蓋化

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

구개음화

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Palatalisasi

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

cách hóa thành khẩu cái âm

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

palatalization

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

पॅलेटलाइजेशन

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

palatalization

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

palatalizacja

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

палаталізація

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

palatalizare

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

ουρανικοποίηση

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

palatalization

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

palatalization

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

palatalisering

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of palatalization

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «PALATALIZATION»

The term «palatalization» is normally little used and occupies the 146.307 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «palatalization» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of palatalization

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «palatalization».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «PALATALIZATION» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «palatalization» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «palatalization» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about palatalization

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «PALATALIZATION»

Discover the use of palatalization in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to palatalization and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

Japanese/Korean Linguistics

and Vogel (1986) claim that the phonological word in Hungarian, which is the

domain of Vowel Harmony and Palatalization, includes a stem plus any linearly

adjacent string of suffixes. The two members of a compound thus form two

different …

Hajime Hoji, Patricia Marie Clancy, 1993

2

Universals of Human Language: Phonology

A General Study of Palatalization D. N. S. BHAT ABSTRACT A cross -Unguis tic

study of palatalization has revealed that there are at least three distinct processes

, namely tongue -fronting, tongue — raising, and spirantization which, occurring …

Joseph Harold Greenberg, Charles Albert Ferguson, Edith A. Moravcsik, 1978

3

Language History and Linguistic Modelling: A Festschrift for …

A. feature. geometric. analysis. of. palatalization. in. English. Jolanta Szpyra

Nonlinear frameworks propounded within the last decade have provided novel

and more insightful ways of approaching many well-known as well as less

frequently …

Raymond Hickey, Stanisław Puppel, 1997

Affective palatalization In Basque, palatalization is used to create diminutives and

affective words. Most frequently, the sibilants s, z are replaced by the prepalatal x

in diminutives. In each of the following pairs the first word is the basic one and …

José Ignacio Hualde, Jon Ortiz de Urbina, 2003

5

Optimality Theory and Language Change

JAYE PADGETT THE EMERGENCE OF CONTRASTIVE PALATALIZATION IN

RUSSIAN Abstract. The well-known contrast in Russian between palatalized and

non-palatalized consonants originated roughly one thousand years ago. At that …

D.E. Holt, International Linguistic Association, 2003

6

The Nordic Languages 2: An International Handbook of the …

Palatalization of alveolars: In northern Norway, Trandelag and northern parts of

western and eastern Norway, long n and / were palatalized (mann > [maji] ‘man’,

vill > [viX] ‘wild’); in most of the dialects this also affected the assimilated clusters …

Oskar Bandle, Kurt Braunmuller, Ernst-Hakon Jahr, 2005

7

Markedness and Economy in a Derivational Model of Phonology

1 Palatalization is triggered by front vowels, and targets all types of consonant—

most often velars or coronals. Yet, there are still two aspects of palatalization that

still do not have an adequate explanation. First of all, besides the addition of a …

8

The Phonology of Romanian: A Constraint-based Approach

Chapter. 6. Post-consonantal. glides. and. palatalization. The previous two

chapters have dealt exclusively with interactions between vocalic segments.

Consonants, however, also have a role to play in hiatus resolution, and their

interactions …

9

Advances in Old Frisian Philology

Palatalization of Velars: A Major Link of Old English and Old Frisian Stephen

Laker 1. INTRODUCTION1 Opinions are divided on whether palatalization of *-k(

k)- and *-g(g)- in Old English and Old Frisian resulted from a shared development

or …

Rolf H. Bremmer, Stephen Laker, Oebele Vries, 2007

10

Morphophonemic Variability, Productivity, and Change: The …

The Case of Rusyn Marta Harasowska. clension systems of masculine nouns in

several other Slavic languages with past and present ties to Rusyn. 2. The «velar

palatalization» from a broader perspective …

7 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «PALATALIZATION»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term palatalization is used in the context of the following news items.

Double up on your kanji to avoid homonym mixups

… pronounced in China, “jiaozi” (sounds like “jee-ow-zuh” with a slight emphasis on “ow”), quite closely, even down to the palatalization of gyo. «The Japan Times, Nov 14»

U.S. to spend $260000 for ultrasound study of Irish speakers’ tongues

The project is called «Collaborative Research: An Ultrasound Investigation of Irish Palatalization.” The image of a flickering tongue will help … «IrishCentral, Sep 14»

Linguists receive $260000 grant to study endangered Irish language

… National Science Foundation to undertake a new project titled «Collaborative Research: An Ultrasound Investigation of Irish Palatalization.” «UC Santa Cruz, Sep 14»

Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2013

Brugmann, the author of the etymology to which I referred, for an obvious reason did not mark palatalization and I reproduced his form because … «OUPblog, Feb 13»

One more thought on «my plezh»

Palatalization is the technical name of the «colonialization» (nice image, … became _drench_ with loss of the infinitive suffix and palatalization of … «The Economist, Feb 12»

How we get from Refugio to Cuco

Waterhouse does identify one phenomenon that factors into many of these name changes: palatalization, when speakers pronounce … «Westword, Dec 08»

Why Lazy Functional Programming Languages Rule

The only thing that’s lacking is automatic palatalization across many cores for map{} operations, but I’m sure I can write a custom iterator to … «Slashdot, Sep 08»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Palatalization [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/palatalization>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

Asked by: Andreanne Trantow

Score: 4.2/5

(19 votes)

Palatalization sometimes refers to vowel shifts, the fronting of a back vowel or raising of a front vowel. The shifts are sometimes triggered by a nearby palatal or palatalized consonant or by a high front vowel. The Germanic umlaut is a famous example.

What is palatalization in phonology?

Palatalization, in phonetics, the production of consonants with the blade, or front, of the tongue drawn up farther toward the roof of the mouth (hard palate) than in their normal pronunciation.

What is the process of palatalization?

The term “palatalization” denotes a phonological process by which consonants acquire secondary palatal articulation or shift their primary place to, or close to, the palatal region. The /k/ sounds then become /t/ and the /g/ sounds then become the /d/ sound.

Which language has a rule of palatalization?

Phonemic palatalization

In some languages, palatalization is a distinctive feature that distinguishes two consonant phonemes. This feature occurs in Russian, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic.

Is there palatalization in English?

Palatalization occurs in English, like t sound becomes ch sounds, for example, in got you.

35 related questions found

How many Affricates are there in English?

English has two affricate phonemes, /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/, often spelled ch and j, respectively.

What is Epenthesis example?

The addition of an i before the t in speciality is an example. The pronunciation of jewelry as ‘jewelery’ is a result of epenthesis, as is the pronunciation ‘contentuous’ for contentious. Other examples of epenthesis: the ubiquitous ‘relitor’ for realtor and that favorite of sports announcers, ‘athalete’ for athlete.

Is L a palatal sound?

The voiced palatal lateral approximant is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ʎ⟩, a rotated lowercase letter ⟨y⟩ (not to be confused with lowercase lambda, ⟨λ⟩), and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is L .

What is Velarisation in phonetics?

Velarization, in phonetics, secondary articulation in the pronunciation of consonants, in which the tongue is drawn far up and back in the mouth (toward the velum, or soft palate), as if to pronounce a back vowel such as o or u.

What is Nasalization example?

The best-known examples of nasalization in English are nasalized vowels. In the production of most vowels the air stream escapes entirely through the mouth, but when a vowel preceding or following a nasal consonant, the air flows out through the mouth and the nose.

What is dissimilation linguistics?

In linguistics: Sound change. Dissimilation refers to the process by which one sound becomes different from a neighbouring sound.

What is Affrication phonological processes?

Affrication is the substitution of an affricate (ch, j) sound for an nonaffricate sound (e.g. “choe” for “shoe”). … Deaffrication is the substitution of a nonaffricate sound for an affricate (ch, j) sound (e.g. “ship” for “chip”). Expect this process to be gone by the age of 4.

What is phonological processes?

Phonological processes: patterns of sound errors that typically developing children use to simplify speech as they are learning to talk. They do this because they lack the ability to appropriately coordinate their lips, tongue, teeth, palate and jaw for clear speech.

What is palatal fronting?

Palatal fronting

The fricative consonants ‘sh’ and ‘zh’ are replaced by fricatives that are made further forward on the palate, towards the front teeth. ‘sh’ is replaced by /s/, and ‘zh’ is replaced by /z/.

What are the front vowels in English?

The front vowels that have dedicated symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet are:

- close front unrounded vowel [i]

- close front compressed vowel [y]

- near-close front unrounded vowel [ɪ]

- near-close front compressed vowel [ʏ]

- close-mid front unrounded vowel [e]

- close-mid front compressed vowel [ø]

What sound is Ʌ?

/ʌ/ is a short vowel sound pronounced with the jaw mid to open, the tongue central or slightly back, and the lips relaxed: As you can see from the examples, /ʌ/ is normally spelt with ‘u’, ‘o’ or a combination of these.

Is a Bilabial sound?

Bilabials or Bilabial consonants are a type of sound in the group of labial consonants that are made with both lips (bilabial) and by partially stopping the air coming from the mouth when the sound is pronounced (consonant). There are eight bilabial consonants used in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Where is R articulated?

There are two primary articulations of the approximant /r/: apical (with the tip of the tongue approaching the alveolar ridge or even curled back slightly) and domal (with a centralized bunching of the tongue known as molar r or sometimes bunched r or braced r ).

What is palatalization and example?

Palatalization, as a sound change, is usually triggered only by mid and close (high) front vowels and the semivowel [j]. The sound that results from palatalization may vary from language to language. For example, palatalization of [t] may produce [tʲ], [tʃ], [tɕ], [tsʲ], [ts], etc.

What are palatal speech sounds?

Palatal, in phonetics, a consonant sound produced by raising the blade, or front, of the tongue toward or against the hard palate just behind the alveolar ridge (the gums). The German ch sound in ich and the French gn (pronounced ny) in agneau are palatal consonants.

What is meant by metathesis?

: a change of place or condition: such as. a : transposition of two phonemes in a word (as in the development of crud from curd or the pronunciation ˈpər-tē for pretty) b : a chemical reaction in which different kinds of molecules exchange parts to form other kinds of molecules.

What causes Epenthesis?

Epenthesis arises for a variety of reasons. The phonotactics of a given language may discourage vowels in hiatus or consonant clusters, and a consonant or vowel may be added to make pronunciation easier. Epenthesis may be represented in writing or be a feature only of the spoken language.

What is Degemination and example?

degemination (countable and uncountable, plural degeminations) (phonetics, uncountable) The inverse process of gemination, when a spoken long consonant is pronounced for an audibly shorter period. (countable) A particular instance of such change.

What is elision and examples?

Elision is the omission of sounds, syllables or words in speech. This is done to make the language easier to say, and faster. ‘I don’t know’ /I duno/ , /kamra/ for camera, and ‘fish ‘n’ chips’ are all examples of elision.

|

Secondary Articulatory Gestures 235 |

|||||

|

TABLE 9.4 |

Contrasts involving palatalization in Russian. |

||||

|

formE |

‘form’ |

fΔErmE |

‘farm’ |

||

|

vItΔ |

‘to howl’ |

vΔitΔ |

‘to weave’ |

||

|

sok |

‘juice’ |

sΔok |

‘he lashed’ |

||

|

zof |

‘call’ |

zΔof |

‘yawn’ |

CD 9.9 |

|

|

pakt |

‘pact’ |

pΔatΔ |

‘five’ |

||

|

bˆl |

‘he was’ |

bΔil |

‘he stroked’ |

||

|

tot |

‘that’ |

tΔotΔE |

‘aunt’ |

||

|

domE |

‘at home’ |

dΔomE |

‘Dyoma’ [ nickname ] |

||

|

kuSEtΔ |

‘to eat’ |

kΔuvΔEtkE |

‘dish’ |

||

said to be palatalized because, instead of the velar contact of the kind that occurs in car [ kA® ], the place of articulation in key is changed so that it is nearer the palatal area. Similarly, palatalization is said to occur when the alveolar fricative [ z ] in is becomes a palato-alveolar fricative in is she [ IZSi ]. A further extension of the term palatalization occurs in discussions of historical sound change. In Old English, the word for chin was pronounced with a velar stop [ k ] at the beginning. The change of this sound into Modern English [ tS ] is said to be one of palatalization, due to the influence of the high front vowel. All these uses of the terms palatalization and palatalized involve descriptions of a process— something becoming something else—rather than a secondary gesture.

Velarization, the next secondary articulation to be considered, involves raising the back of the tongue. It can be considered as the addition of an [ u ]-like tongue position, but without the addition of the lip rounding that also occurs in [ u ]. We have already noted that in many forms of English, syllable final / l / sounds are velarized and may be written [ : ].

As an exercise, so that you can appreciate how it is possible to add vowel-like articulations to consonants, try saying each of the vowels [ i, e, E, a, A, O, o, u ], but with the tip of your tongue on the alveolar ridge. The first of these sounds is, of course, a palatalized sound very similar to [ lΔ ]. The last of the series is one form of velarized [ : ]. Make sure you can say each of these sounds before and after different vowels. Now compare palatalized and velarized versions of other sounds in syllables such as [ nΔa ] and [n◊a ]. Remember that [ n◊] with the velarization diacritic [◊] is simply [n] with a superimposed unrounded nonsyllabic [u] glide (that is, an added [ U ] glide).

Pharyngealization is the superimposition of a narrowing of the pharynx. Since cardinal vowel (5)—[A]—has been defined as the lowest, most back vowel possible without producing pharyngeal friction, pharyngealization may be considered as the superimposition of this vowel quality. One IPA diacritic for symbolizing pharyngealization is [ º], the same as for velarization. If it is necessary to distinguish between these two secondary articulations, then the IPA provides an alternative: using small raised symbols corresponding to velar and pharyngeal

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

236 CHAPTER 9 Vowels and Vowel-like Articulations

fricatives, representing a velarized alveolar nasal as [ n◊ ] and a pharyngealized alveolar nasal as [ n≥ ]. Marking velarization and pharyngealization in this way is also preferable when the use of the [ ]ºdiacritic creates a symbol that is hard to decipher.

There is very little difference between velarized and pharyngealized sounds, and no language distinguishes between the two possibilities. In Arabic, there is a series of consonants that Arabic scholars call emphatic consonants. Some of these sounds are velarized, and some are pharyngealized. All of them can be symbolized with the IPA diacritic [ ]º. (Arabic scholars often use a subscript dot [ . ].) There is some similarity in quality between retroflex stops and velarized or pharyngealized stops, because in all these sounds, the front of the tongue is somewhat hollowed.

Labialization, the addition of lip rounding, differs from the other secondary articulations in that it can be combined with any of them. Obviously, palatalization, velarization, and pharyngealization involve different tongue shapes that cannot occur simultaneously. But nearly all kinds of consonants can have added lip rounding, including those that already have one of the other secondary articulations. In a sense, even sounds in which the primary articulators are the lips— for example, [ p, b, m ]—can be said to be labialized if they are made with added rounding and protrusion of the lips. Because labialization is often accompanied by raising the back of the tongue, it is symbolized by a raised [ W ]. In a more precise system, this might be taken to indicate a secondary articulation that we could call labiovelarization, but this is seldom distinguished from labialization.

In some languages (for instance, Twi and other Akan languages spoken in Ghana), labialization co-occurs with palatalization. As palatalization is equivalent to the superimposition of a gesture similar to that in [ i ], labialization plus palatalization is equivalent to the superimposition of a rounded [ i ]—that is, [ y ]. As we have seen, the corresponding semivowel is [ μ ]. Accordingly, these secondary articulations may be symbolized by a raised [ μ ]. Recall the pronunciation of [ μ ] in French words such as huit [ μit ] “eight.” Then try to pronounce the name of one of the dialects of Akan, Twi [ tμi ].

Table 9.5 summarizes the secondary gestures we have been discussing. As in some of the previous summary tables, the terms in Table 9.5 are not all mutually exclusive. A sound may or may not have a secondary articulation such

TABLE 9.5 Secondary gestures.

|

Phonetic Term |

Brief Description |

Symbols |

|

|

palatalization |

raising of the front of the tongue |

sΔ lΔ |

dΔ |

|

velarization |

raising of the back of the tongue |

s◊ : |

b◊ |

|

pharyngealization |

retracting of the root of the tongue |

s≥ : |

b≥ |

|

labialization |

rounding of the lips |

sW lW dW |

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Exercises 237

as palatalization, velarization, or pharyngealization; it may or may not be labialized; and it may or may not be nasalized. To demonstrate this for yourself, try to make a voiced alveolar lateral [ l ] that is also velarized, labialized, and nasalized.

EXERCISES

(Printable versions of all the exercises are available on the CD.)

A.Look at the positions of the tongue in the English vowels shown in Figure 1.12. It has been suggested (see “Notes”) that vowels can be described in terms of three measurements: (1) the area of the vocal tract at the point of maximum constriction; (2) the distance of this point from the glottis; and (3) a measure of the degree of lip opening.

1.Which of the first two corresponds to what is traditionally called vowel height for the vowels in heed, hid, head, had?

2.Which corresponds to vowel height for the vowels in father, good, food?

3.Can these two measurements be used to distinguish front vowels from back vowels?

B.Another way of describing the tongue position in vowels that has been suggested (see “Endnotes”) is to say that the tongue is in a neutral position in the vowel in head and that (1) the body of the tongue is higher than in its neutral position in vowels such as those in heed, hid, good, food; (2) the body of the tongue is more back than in its neutral position in good, food, father; (3) the root of the tongue is advanced in heed, food; and (4) the root of the tongue is pulled back so that the pharynx is more constricted than in the neutral position in had, father. How far do the data in Figure 1.12 support these suggestions?

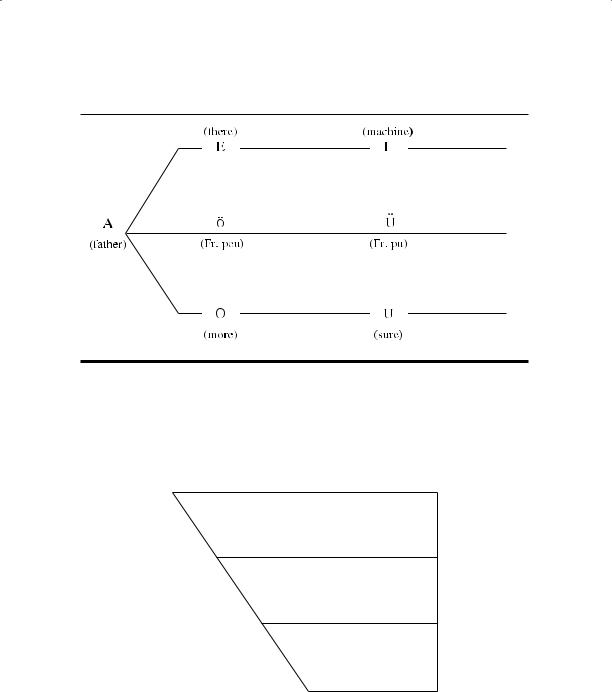

C.In the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries (see “Endnotes” ), there were said to be three sets of vowels: (1) a set exemplified by the vowels in see, play, father (and intermediate possibilities), which were said to be distinguished simply by the degree of jaw opening; (2) a set exemplified by the vowels in fool, home, father (and intermediate possibilities), which were said to be distinguished simply by the degree of lip rounding; and (3) a set exemplified by the vowels now symbolized by [ y, „ ] as in the French words tu, peu ‘you, small,’ which were said to be distinguished by both the degree of jaw opening and the degree of lip rounding. These notions were shown in diagrams similar to that in Figure 9.14. How do they compare with contemporary descriptions of vowels? What general type of vowel cannot be described in these terms?

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

238CHAPTER 9 Vowels and Vowel-like Articulations

Figure 9.14 The vowel classification used by Helmholtz (1863), with key words suggested by Ellis (1885).

D.Try to find a speaker of some language other than English. Elicit a set of minimal pairs exemplifying the vowels of this language. You will probably find it helpful to consult the pronunciation section in a dictionary or grammar of the language. Listen to the vowels and plot them on a vowel chart. (Do not attempt this exercise until you have worked through the Performance Exercises for this chapter.)

PERFORMANCE EXERCISES

The object of many of the following exercises is to get you to produce a wide variety of vowels that are not in your own language. When you can produce small differences in vowel quality, you will find it easier to hear them.

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Performance Exercises 239

A.Say the monophthongs [ i, e ] corresponding to at least the first part of your vowels in see, say. Try to make a vowel with a quality in between [ i ] and [ e ]. Then make as many vowels as you can in a series between [i] and [e]. Finally, make a similar series going in the opposite direction—from [e] to [i].

B.Repeat this exercise with monophthongs corresponding to the following pairs of vowels in your own speech. Remember to produce each series in both directions.

[ I–” ]

[ ”–œ ]

[ œ–A ]

[ A–O ], if occurring in your speech

[ O–o ] or [A–o ]

[o–u ]

C.Try moving continuously from one member of each pair to the other, slurring through all the possibilities you produced in the previous exercises. Do this in each direction.

D.For each pair of vowels, produce a vowel that is, as nearly as you can determine, halfway between the two members.

E.Repeat Exercises A, C, and D with the following pairs of vowels, which will involve producing larger adjustments in lip rounding. Remember to produce each series in both directions, and be sure you try all the different tasks suggested in Exercises A, C, and D.

[ i–u ]

[e–o ]

F.Now repeat all the same exercises, but with no adjustments in lip rounding, using the following pairs of vowels. Go in both directions, of course.

[ i–U ]

[ e–V ]

[ y–u ]

[„–o ]

G.Practice distinguishing different central vowels. When you have learned to produce a high-central unrounded vowel [ ˆ ], try to produce midand lowcentral unrounded vowels, which may be symbolized [ ´ ] and [ ∏ ]. Try Exercises A, C, and D with the following pairs of vowels:

[ ˆ–´ ]

[ ´–∏ ]

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

240 CHAPTER 9 Vowels and Vowel-like Articulations

H.Produce the following nasal and oral vowels. When making the nasalized vowels, be careful to keep the same tongue position, moving only the soft palate.

)

[ i–i–i ]

[ e–e)–e ]

[ œ–œ)–{ ]

[ A–A)–A]

[ o–o)–o ]

[u–u)–u ]

I.Now compare nasalized vowels with oral vowels that have slightly different tongue positions. Say:

) )

[ i–i–I–i ]

[ e–e)–”–e)]

[ ”–”)–œ–”)]

[ u–u)–o–u)]

[o–o)–O–o)]

J.Make sure you can produce a variety of different vowels by saying nonsense words such as those shown below, preferably to a partner who can check your pronunciation.

·petuz sy·t„t ·m”)nod

·tynob di·gUd pœ·nyt

·bUg”d mo·pAt ·degu)n

·nis„p gu·dob sy·to)n

·bœdid kU·typ ·k„b”)s

K.Learn to produce diphthongs going to and from a variety of vowels. Using the vowel symbols with their values as in English, read the following, first column by column, then row by row.

|

iI |

Ii |

ei |

”i |

œi |

Ai |

Oi |

oi |

Ái |

ui |

Øi |

|

ie |

Ie |

eI |

”I |

œI |

AI |

OI |

oI |

ÁI |

uI |

ØI |

|

i” |

I” |

e” |

”e |

œe |

Ae |

Oe |

oe |

Áe |

ue |

Øe |

|

iœ |

Iœ |

eœ |

”œ |

œ” |

A” |

O” |

o” |

Á” |

u” |

Ø” |

|

iA |

IA |

eA |

”A |

œA |

Aœ |

Oœ |

oœ |

Áœ |

uœ |

؜ |

|

iO |

IO |

eO |

”O |

œO |

AO |

OA |

oA |

ÁA |

uA |

ØA |

|

io |

Io |

eo |

”o |

œo |

Ao |

Oo |

oO |

ÁO |

uO |

ØO |

|

iÁ |

IÁ |

eÁ |

”Á |

œÁ |

AÁ |

OÁ |

oÁ |

Áo |

uo |

Øo |

|

iu |

Iu |

eu |

”u |

œu |

Au |

Ou |

ou |

Áu |

uA! |

ØA! |

|

iØ |

IØ |

eØ |

ӯ |

ϯ |

AØ |

OØ |

oØ |

ÁØ |

uØ |

Øu |

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Performance Exercises 241

L.Try saying some of these diphthongs in one-, two-, and three-syllable nonsense words such as those shown below. These are good items to use in ear-training practice with a partner.

|

tIop |

·doeb·mOid |

sœo·tAoneu |

|

tØep |

·deub·mAud |

sOA·t”onIÁ |

|

tAOp |

·dIÁb·mØOd |

so”·tœunue |

|

t”Ap |

·doeb·moid |

sAØ·tØinui |

|

toØp |

·dÁ”b·nu”d |

sOI·tIunœA |

M.Now extend your range by including front rounded and back unrounded vowels as exemplified below.

|

iy |

ey |

Ay |

uy |

yi |

„i |

Ui |

y„ |

„y |

Uy |

|

i„ |

e„ |

A„ |

u„ |

ye |

„e |

Ue |

yU |

„U |

U„ |

|

iU |

eU |

AU |

uU |

yA |

„A |

UA |

yu |

„u |

Uu |

N.These vowels can also be included in nonsense words such as those shown below for both performance and ear-training practice.

|

dUeb |

·tyœb·meyd |

tUy·neAsØ„ |

|

di„b |

·tuÁb·mu„d |

tue·n„usÁI |

|

deub |

·tO„b·mAud |

t”U·noysœu |

|

doub |

·t„Áb·mU”d |

tyI·n„ysoO |

|

dœob |

·tUAb·miod |

tA„·nAesIy |

O.Practice all the vowels and consonants discussed in the previous chapters in more complicated nonsense words such as the following:

|

VA·rot1iF |

NOv„·d1e= |

jœLU·∫eÎ |

|

be·Ô”ZuD |

GACy·bIg |

sy·t’o∑”k˘ |

|

≠i·∂yx”n1 |

ße?O·pœz |

¥”·n„k’œx |

|

Tœ·–AkUS |

fi‰o·ce¬ |

k!i®u·god |

|

Ω„·XoqOl |

heBU·Ôœt |

wup’O·k˘˘em |

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

10

Syllables and

Suprasegmental Features

Throughout this book, there have been references to the notion syllable, but this term has never been defined. The reason for this is simple: there is no agreed phonetic definition of a syllable. This chapter will discuss some of the theories that have been advanced and show why they are not entirely adequate. We will also consider suprasegmental features—those aspects of speech that involve more than single consonants or vowels. The principal suprasegmental features are stress, length, tone, and intonation. These features are independent of the categories required for describing segmental features (vowels and consonants), which involve airstream mechanisms, states of the glottis, primary and secondary articulations, and formant frequencies.

SYLLABLES

The fact that syllables are important units is illustrated by the history of writing. Many writing systems have one approximately symbol for each syllable, a well-known present-day example being Japanese. But only once in the history of humankind has anybody devised an alphabetic writing system in which syllables were systematically split into their components. About three thousand years ago, the Greeks modified the Semitic syllabary so as to represent consonants and vowels by separate symbols. The later Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, Indic, and other alphabetic writing systems can all be traced back to the principles first and last established in Greek writing. It seems that everybody finds syllables comparatively easy units to identify. But people who have not been educated in an alphabetic writing system find it much more difficult to consider syllables as being made up of segments (consonants and vowels).

Most syllables contain both vowels and consonants, but some, such as eye and owe, have only vowels. Many consonants can also function as syllables. Alveolar laterals and nasals (as at the ends of button and bottle) are common in English, but other nasals may occur, as in blossom and bacon, particularly in phrases such as the blossom may fade and bacon goes well with eggs, in which the following sounds aid the assimilatory process. Fricatives and stops may

243

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

244 CHAPTER 10 Syllables and Suprasegmental Features

become syllabic in unstressed syllables as in suppose and today, which may be [ s`·poÁz ] and [ t `Ó·deI ] in a narrow transcription. People vary in their pronunciation of these words and phrases. For us, they are all syllabic consonants, but others may consider all the examples in this paragraph as consisting of a consonant and an associated [ ´ ].

Although it is difficult to define what is meant by a syllable, nearly everybody can identify individual syllables. If you consider how many syllables there are in minimization or suprasegmental, you can easily count them. Each of these words has five syllables. Nevertheless, it is curiously difficult to state an objective phonetic procedure for locating the number of syllables and especially the boundaries between syllables in a word or a phrase in any language, and it is interesting that most people cannot say how many syllables there are in a phrase they have just heard without first saying that phrase themselves.

In a few cases, people disagree on how many syllables there are in a word in English. Some of these disagreements arise from dialectal differences in the way particular words are spoken. For some, the word predatory has three syllables because they say [ ·pr”dEtrI ]. Other people who pronounce it as [·pr”dEtO®i] say that it has four syllables. Similarly, there are many words, such as bottling and brightening, that some people pronounce with syllabic consonants in the middle, so that they have three syllables, whereas others do not.

There are also several groups of words that people pronounce the same way, but nevertheless differ in their estimates of the number of syllables. One group of words contains nasals that may or may not be counted as separate syllables. Thus, words such as pessimism and mysticism may be said to have three or four syllables, depending on whether the final [ m ] is considered to be syllabic. A second group contains high front vowels followed by / 1 /. Many people will say that meal, seal, reel contain two syllables, but others will consider them to have one. A third group contains words in which / r / may or may not be syllabic. Some people consider hire, fire, hour to be two syllables, whereas others (who pronounce them in exactly the same way) do not. Similar disagreements also arise over words such as mirror and error for some American English speakers. Finally, there is disagreement over the number of syllables in a group of words that contain unstressed high vowels followed by another vowel without an intervening consonant. Examples are words such as mediate, heavier, Neolithic. Differences of opinion as to the number of syllables in these words may be due to differences in the way they are actually pronounced, just as in the case of predatory cited earlier. But, unlike predatory, it is often not clear if a syllable has been omitted on a particular occasion.

It is also possible that different people do different things when asked to say how many syllables there are in a word. Some people may pay more attention to the phonological structure of words than others. Thus, many people will say that realistic has three syllables. But others will consider it to have four syllables

Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Palatalizing)

Jump to: navigation, search

| Sound change and alternation |

|---|

|

Metathesis (reordering) Quantitative metathesis |

|

Lenition (weakening) Consonant gradation |

| Fortition (strengthening) |

|

Elision (loss) Apheresis (initial) |

|

Epenthesis (addition) Anaptyxis (vowel) |

|

Assimilation Coalescence |

| Dissimilation |

|

Cheshirisation (trace remains) Compensatory lengthening |

|

Sandhi (boundary change) Liaison, linking R Synalepha (contraction) Elision (loss of one vowel) |

|

This box: view • talk • edit |

Palatalization or palatalisation (pronounced /ˌpælətəlɨˈzeɪʃən/) generally refers to two phenomena:

- As a process or the result of a process, the effect that front vowels and the palatal approximant [j] frequently have on consonants;

- As a phonetic description, the secondary articulation of consonants by which the body of the tongue is raised toward the hard palate during the articulation of the consonant. Such consonants are phonetically palatalized, and in the International Phonetic Alphabet they are indicated by a superscript ‘j’, as [tʲ] for a palatalized [t]. Prior to 1989, several palatalized consonants were represented by curly-tailed variants in the IPA, e.g. [ʆ] for [ʃʲ] and [ʓ] for [ʒʲ] (see Palatal hook).

The second may be the result of the first, but they often differ. A vowel may «palatalize» a consonant (sense 1), but the result might not be a palatalized consonant in the phonetic sense (sense 2), or the phonetically palatalized (sense 2) consonant may occur irrespective of front vowels.

Conversely, the word «palatalization» may also be used for the effect a palatal or palatalized consonant exerts on nearby sounds, as in the history of old French where Bartsch’s law turned low vowels into [e] or [ɛ] after a palatalized velar, or in the Uralic language Erzya, where the front vowel [æ] only occurs as an allophone of [a] after a palatalized consonant, as seen in the pronunciation of the name of the language itself, [erzʲæ]. However, while the process may be called palatalization, the resulting vowel [æ] is not called a palatalized vowel in the phonetic sense. Terminology such as «palatal vowel» is found, however, but this is primary and not secondary articulation.

Contents

- 1 Phonetic description

- 2 Phonological (synchronic) palatalization

- 3 Historical (diachronic) palatalization

- 4 Local uses of the word

- 5 See also

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Phonetic description

«Pure» palatalization is denoted by a small superscript < ʲ > in IPA. This is a modification to the articulation of a consonant, where the middle of the tongue is raised, and nothing else. It may produce a laminal articulation of otherwise apical consonants such as /t/ and /s/. It is a phonemic feature in some languages; a common misconception is that it’s merely allophonic, like in English. Phonemic palatalization may be contrasted with either plain or velarized articulation. In Baltic-Finnic languages, Baltic and Slavic languages, the contrast is with plain consonants, but in Irish, it is with velarized consonants.

Phonetically palatalized consonants may vary in their exact realization. Some, but not all languages add offglides or onglides. In Russian, both plain and palatalized consonant phonemes are found in words like пальто [pɐˈlʲto], царь [tsarʲ] and Катя [ˈkatʲə]. Typically, the vowel following a palatalized consonant has a palatal offglide. In Hupa, on the other hand, the palatalization is heard as both an onglide and an offglide: [aʲkʲa].

Palatalization can also occur as a suprasegmental feature that affects the pronunciation of an entire syllable. This is the case in Skolt Sami, a language which is unusual in contrasting suprasegmental palatalization with segmental palatalization (i.e., inherently palatalized consonants).

Phonological (synchronic) palatalization

Palatalization may be a synchronic phonological process, i.e., some phonemes are palatalized in certain contexts, typically before front vowels or especially high front vowels, and remain non-palatalized elsewhere. This is usually phonetic palatalization, as described above, but need not to be. It is usually allophonic and it may go unnoticed by native speakers. As an example, compare the /k/ of English key with the /k/ of coo, or the /t/ of tea with the /t/ of took. The first word of each pair is palatalized, but few English speakers would perceive them as distinct.

The variation might be seen as allophonic variation as long as the «palatal» sound causing the palatalization is there. However, syncope or elision might delete this sound, and thus only the palatalization remains as a distinct feature. This process is widespread in Baltic-Finnic languages, which have lost their original (Uralic) phonemic palatalization but some have regained it. For a minimal pair, consider Estonian kass [kɑsʲː] from *kassi «cat» vs. kas [kɑsː] (interrogative).

Sometimes palatalization is part of a synchronic grammatical process, such as palatalizing the first consonant of a verb root to signal the past tense. This type of palatalization is phonemic, and is recognized by the speakers as a contrasting feature. However, what may have started off as phonetic palatalization can quickly evolve into something else, so not all of the resulting consonants are necessarily palatalized phonetically.

Historical (diachronic) palatalization

Palatalization may be a diachronic phonemic split, that is, a historical change by which a phoneme becomes two new phonemes over time through phonetic palatalization. Old historical splits have frequently drifted since the time they occurred, and may be independent of current phonetic palatalization. For example, Votic has undergone such a change historically, in for example keeli → tšeeli (‘language’), but there is currently an additional distinction between palatalized laminal and non-palatalized apical consonants.

While the great majority of palatalization effects are connected with sequences with a consonant adjacent to a high front or mid front vowel or glide, palatalization may occur spontaneously in a sense. In Southwestern Romance, l in word-initial clusters after a voiceless obstruent became palatalized, as Latin clamare (‘to call’) → Italian chiamare /kjamare/, Old Portuguese chamar, while in Spanish the obstruent drops before the palatalized liquid: llamar /ʎamar/. Differently, in an even larger area, Latin *[kt] became *[kʲt] (or even *[kʲtʲ]) thus from a form like Latin octō (‘eight’) French huit, Spanish ocho, Portuguese oito /oitu/.