- W

- Population

- World Population

Current World Population

retrieving data…

Today

Population Growth today

…

This year

Population Growth this year

…

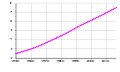

World Population: Past, Present, and Future

(move and expand the bar at the bottom of the chart to navigate through time)

The chart above illustrates how world population has changed throughout history. View the full tabulated data.

At the dawn of agriculture, about 8000 B.C., the population of the world was approximately 5 million. Over the 8,000-year period up to 1 A.D. it grew to 200 million (some estimate 300 million or even 600, suggesting how imprecise population estimates of early historical periods can be), with a growth rate of under 0.05% per year.

A tremendous change occurred with the industrial revolution: whereas it had taken all of human history until around 1800 for world population to reach one billion, the second billion was achieved in only 130 years (1930), the third billion in 30 years (1960), the fourth billion in 15 years (1974), and the fifth billion in only 13 years (1987).

- During the 20th century alone, the population in the world has grown from 1.65 billion to 6 billion.

- In 1970, there were roughly half as many people in the world as there are now.

- Because of declining growth rates, it will now take over 200 years to double again.

Wonder how big was the world’s population when you were born?

Check out this simple wizard or this more elaborated one to find out.

Sources:

- World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision — United Nations Population Division

- The World at Six Billion, World Population, Year 0 to near stabilization [Pdf file] — United Nations Population Division

Growth Rate

Population in the world is, as of 2022, growing at a rate of around 0.84% per year (down from 1.05% in 2020, 1.08% in 2019, 1.10% in 2018, and 1.12% in 2017). The current population increase is estimated at 67 million people per year.

Annual growth rate reached its peak in the late 1960s, when it was at around 2%. The rate of increase has nearly halved since then, and will continue to decline in the coming years.

World population will therefore continue to grow in the 21st century, but at a much slower rate compared to the recent past. World population has doubled (100% increase) in 40 years from 1959 (3 billion) to 1999 (6 billion). It is now estimated that it will take another nearly 40 years to increase by another 50% to become 9 billion by 2037.

The latest world population projections indicate that world population will reach 10 billion persons in the year 2057.

World Population (2020 and historical)

View the complete population historical table

| Year (July 1) |

Population | Yearly % Change |

Yearly Change |

Median Age |

Fertility Rate |

Density (P/Km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 7,794,798,739 | 1.05 % | 81,330,639 | 30.9 | 2.47 | 52 |

| 2019 | 7,713,468,100 | 1.08 % | 82,377,060 | 29.8 | 2.51 | 52 |

| 2018 | 7,631,091,040 | 1.10 % | 83,232,115 | 29.8 | 2.51 | 51 |

| 2017 | 7,547,858,925 | 1.12 % | 83,836,876 | 29.8 | 2.51 | 51 |

| 2016 | 7,464,022,049 | 1.14 % | 84,224,910 | 29.8 | 2.51 | 50 |

| 2015 | 7,379,797,139 | 1.19 % | 84,594,707 | 30 | 2.52 | 50 |

| 2010 | 6,956,823,603 | 1.24 % | 82,983,315 | 28 | 2.58 | 47 |

| 2005 | 6,541,907,027 | 1.26 % | 79,682,641 | 27 | 2.65 | 44 |

| 2000 | 6,143,493,823 | 1.35 % | 79,856,169 | 26 | 2.78 | 41 |

| 1995 | 5,744,212,979 | 1.52 % | 83,396,384 | 25 | 3.01 | 39 |

| 1990 | 5,327,231,061 | 1.81 % | 91,261,864 | 24 | 3.44 | 36 |

| 1985 | 4,870,921,740 | 1.79 % | 82,583,645 | 23 | 3.59 | 33 |

| 1980 | 4,458,003,514 | 1.79 % | 75,704,582 | 23 | 3.86 | 30 |

| 1975 | 4,079,480,606 | 1.97 % | 75,808,712 | 22 | 4.47 | 27 |

| 1970 | 3,700,437,046 | 2.07 % | 72,170,690 | 22 | 4.93 | 25 |

| 1965 | 3,339,583,597 | 1.93 % | 60,926,770 | 22 | 5.02 | 22 |

| 1960 | 3,034,949,748 | 1.82 % | 52,385,962 | 23 | 4.90 | 20 |

| 1955 | 2,773,019,936 | 1.80 % | 47,317,757 | 23 | 4.97 | 19 |

World Population Forecast (2020-2050)

View population projections for all years (up to 2100)

| Year (July 1) |

Population | Yearly % Change |

Yearly Change |

Median Age |

Fertility Rate |

Density (P/Km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 7,794,798,739 | 1.10 % | 83,000,320 | 31 | 2.47 | 52 |

| 2025 | 8,184,437,460 | 0.98 % | 77,927,744 | 32 | 2.54 | 55 |

| 2030 | 8,548,487,400 | 0.87 % | 72,809,988 | 33 | 2.62 | 57 |

| 2035 | 8,887,524,213 | 0.78 % | 67,807,363 | 34 | 2.70 | 60 |

| 2040 | 9,198,847,240 | 0.69 % | 62,264,605 | 35 | 2.77 | 62 |

| 2045 | 9,481,803,274 | 0.61 % | 56,591,207 | 35 | 2.85 | 64 |

| 2050 | 9,735,033,990 | 0.53 % | 50,646,143 | 36 | 2.95 | 65 |

World Population Milestones

10 Billion (2058)

The United Nations projects world population to reach 10 billion in the year 2058.

9 Billion (2037)

World population is expected to reach 9 billion in the year 2037.

8 Billion (2022)

World population has reached 8 billion people on November 15, 2022 according to the United Nations.

7 Billion (2010)

According to the latest revision by the United Nations (released in 2022), world population reached 7 Billion in late 2010 (this was previously estimated as occurring on October 31, 2011). The US Census Bureau made a lower estimate, for which the 7 billion mark was only reached on March 12, 2012.

6 Billion (1998)

According to the latest revision by the United Nations (released in 2022), the 6 billion figure was reached towards the end of 1998 (this was previously estimated as occurring on October 12, 1999, celebrated as the Day of 6 Billion). According to the U.S. Census Bureau instead, the six billion milestone was reached on July 22, 1999, at about 3:49 AM GMT. Yet, according to the U.S. Census, the date and time of when 6 billion was reached will probably change because the already uncertain estimates are constantly being updated.

Previous Milestones

- 5 Billion: 1987

- 4 Billion: 1974

- 3 Billion: 1960

- 2 Billion: 1930

- 1 Billion: 1804

Summary Table

1 — 1804 (1803 years): 0.2 to 1 bil.

1804 — 2022 (218 years): from 1 billion to 8 billion

| Year |

1 |

1000 |

1500 |

1650 |

1750 |

1804 |

1850 |

1900 |

1930 |

1950 |

1960 |

1974 |

1980 |

1987 |

1998 |

2010 |

2022 |

2029 |

2037 |

2046 |

2058 |

2100 |

| Population |

0.2 |

0.275 |

0.45 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

2 |

2.55 |

3 |

4 |

4.5 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

8.5 |

9 |

9.5 |

10 |

10.3 |

World Population by Region

| # | Region | Population (2020) |

Yearly Change |

Net Change |

Density (P/Km²) |

Land Area (Km²) |

Migrants (net) |

Fert. Rate |

Med. Age |

Urban Pop % |

World Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asia | 4,641,054,775 | 0.86 % | 39,683,577 | 150 | 31,033,131 | -1,729,112 | 2.2 | 32 | 0 % | 59.5 % |

| 2 | Africa | 1,340,598,147 | 2.49 % | 32,533,952 | 45 | 29,648,481 | -463,024 | 4.4 | 20 | 0 % | 17.2 % |

| 3 | Europe | 747,636,026 | 0.06 % | 453,275 | 34 | 22,134,900 | 1,361,011 | 1.6 | 43 | 0 % | 9.6 % |

| 4 | Latin America and the Caribbean | 653,962,331 | 0.9 % | 5,841,374 | 32 | 20,139,378 | -521,499 | 2 | 31 | 0 % | 8.4 % |

| 5 | Northern America | 368,869,647 | 0.62 % | 2,268,683 | 20 | 18,651,660 | 1,196,400 | 1.8 | 39 | 0 % | 4.7 % |

| 6 | Oceania | 42,677,813 | 1.31 % | 549,778 | 5 | 8,486,460 | 156,226 | 2.4 | 33 | 0 % | 0.5 % |

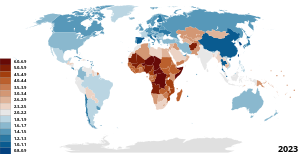

World Population Density (people/km2)

Population density map of the world showing not only countries but also many subdivisions (regions, states, provinces). See also: World Map

Courtesy of Junuxx at en.wikipedia [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

World Population by Religion

According to a recent study (based on the 2010 world population of 6.9 billion) by The Pew Forum, there are:

- 2,173,180,000 Christians (31% of world population), of which 50% are Catholic, 37% Protestant, 12% Orthodox, and 1% other.

- 1,598,510,000 Muslims (23%), of which 87-90% are Sunnis, 10-13% Shia.

- 1,126,500,000 No Religion affiliation (16%): atheists, agnostics and people who

do not identify with any particular religion. One-in-five people (20%) in the United States are religiously unaffiliated. - 1,033,080,000 Hindus (15%), the overwhelming majority (94%) of which live in India.

- 487,540,000 Buddhists (7%), of which half live in China.

- 405,120,000 Folk Religionists (6%): faiths that are closely associated with a particular

group of people, ethnicity or tribe. - 58,110,000 Other Religions (1%): Baha’i faith, Taoism,

Jainism, Shintoism, Sikhism, Tenrikyo, Wicca, Zoroastrianism and many others. - 13,850,000 Jews (0.2%), four-fifths of which live in two countries: United States (41%) and Israel (41%).

World Population by Country

| # | Country (or dependency) | Population (2020) |

Yearly Change |

Net Change |

Density (P/Km²) |

Land Area (Km²) |

Migrants (net) |

Fert. Rate |

Med. Age |

Urban Pop % |

World Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 1,439,323,776 | 0.39 % | 5,540,090 | 153 | 9,388,211 | -348,399 | 1.69 | 38 | 60.8 % | 18.5 % |

| 2 | India | 1,380,004,385 | 0.99 % | 13,586,631 | 464 | 2,973,190 | -532,687 | 2.2402 | 28 | 35 % | 17.7 % |

| 3 | United States | 331,002,651 | 0.59 % | 1,937,734 | 36 | 9,147,420 | 954,806 | 1.7764 | 38 | 82.8 % | 4.2 % |

| 4 | Indonesia | 273,523,615 | 1.07 % | 2,898,047 | 151 | 1,811,570 | -98,955 | 2.3195 | 30 | 56.4 % | 3.5 % |

| 5 | Pakistan | 220,892,340 | 2 % | 4,327,022 | 287 | 770,880 | -233,379 | 3.55 | 23 | 35.1 % | 2.8 % |

| 6 | Brazil | 212,559,417 | 0.72 % | 1,509,890 | 25 | 8,358,140 | 21,200 | 1.74 | 33 | 87.6 % | 2.7 % |

| 7 | Nigeria | 206,139,589 | 2.58 % | 5,175,990 | 226 | 910,770 | -60,000 | 5.4168 | 18 | 52 % | 2.6 % |

| 8 | Bangladesh | 164,689,383 | 1.01 % | 1,643,222 | 1,265 | 130,170 | -369,501 | 2.052 | 28 | 39.4 % | 2.1 % |

| 9 | Russia | 145,934,462 | 0.04 % | 62,206 | 9 | 16,376,870 | 182,456 | 1.8205 | 40 | 73.7 % | 1.9 % |

| 10 | Mexico | 128,932,753 | 1.06 % | 1,357,224 | 66 | 1,943,950 | -60,000 | 2.14 | 29 | 83.8 % | 1.7 % |

| 11 | Japan | 126,476,461 | -0.3 % | -383,840 | 347 | 364,555 | 71,560 | 1.3697 | 48 | 91.8 % | 1.6 % |

| 12 | Ethiopia | 114,963,588 | 2.57 % | 2,884,858 | 115 | 1,000,000 | 30,000 | 4.3 | 19 | 21.3 % | 1.5 % |

| 13 | Philippines | 109,581,078 | 1.35 % | 1,464,463 | 368 | 298,170 | -67,152 | 2.58 | 26 | 47.5 % | 1.4 % |

| 14 | Egypt | 102,334,404 | 1.94 % | 1,946,331 | 103 | 995,450 | -38,033 | 3.33 | 25 | 43 % | 1.3 % |

| 15 | Vietnam | 97,338,579 | 0.91 % | 876,473 | 314 | 310,070 | -80,000 | 2.0556 | 32 | 37.7 % | 1.2 % |

| 16 | DR Congo | 89,561,403 | 3.19 % | 2,770,836 | 40 | 2,267,050 | 23,861 | 5.9635 | 17 | 45.6 % | 1.1 % |

| 17 | Turkey | 84,339,067 | 1.09 % | 909,452 | 110 | 769,630 | 283,922 | 2.08 | 32 | 75.7 % | 1.1 % |

| 18 | Iran | 83,992,949 | 1.3 % | 1,079,043 | 52 | 1,628,550 | -55,000 | 2.15 | 32 | 75.5 % | 1.1 % |

| 19 | Germany | 83,783,942 | 0.32 % | 266,897 | 240 | 348,560 | 543,822 | 1.586 | 46 | 76.3 % | 1.1 % |

| 20 | Thailand | 69,799,978 | 0.25 % | 174,396 | 137 | 510,890 | 19,444 | 1.5346 | 40 | 51.1 % | 0.9 % |

| 21 | United Kingdom | 67,886,011 | 0.53 % | 355,839 | 281 | 241,930 | 260,650 | 1.75 | 40 | 83.2 % | 0.9 % |

| 22 | France | 65,273,511 | 0.22 % | 143,783 | 119 | 547,557 | 36,527 | 1.8523 | 42 | 81.5 % | 0.8 % |

| 23 | Italy | 60,461,826 | -0.15 % | -88,249 | 206 | 294,140 | 148,943 | 1.33 | 47 | 69.5 % | 0.8 % |

| 24 | Tanzania | 59,734,218 | 2.98 % | 1,728,755 | 67 | 885,800 | -40,076 | 4.9237 | 18 | 37 % | 0.8 % |

| 25 | South Africa | 59,308,690 | 1.28 % | 750,420 | 49 | 1,213,090 | 145,405 | 2.4139 | 28 | 66.7 % | 0.8 % |

| 26 | Myanmar | 54,409,800 | 0.67 % | 364,380 | 83 | 653,290 | -163,313 | 2.17 | 29 | 31.4 % | 0.7 % |

| 27 | Kenya | 53,771,296 | 2.28 % | 1,197,323 | 94 | 569,140 | -10,000 | 3.52 | 20 | 27.8 % | 0.7 % |

| 28 | South Korea | 51,269,185 | 0.09 % | 43,877 | 527 | 97,230 | 11,731 | 1.11 | 44 | 81.8 % | 0.7 % |

| 29 | Colombia | 50,882,891 | 1.08 % | 543,448 | 46 | 1,109,500 | 204,796 | 1.82 | 31 | 80.4 % | 0.7 % |

| 30 | Spain | 46,754,778 | 0.04 % | 18,002 | 94 | 498,800 | 40,000 | 1.33 | 45 | 80.3 % | 0.6 % |

| 31 | Uganda | 45,741,007 | 3.32 % | 1,471,413 | 229 | 199,810 | 168,694 | 5.01 | 17 | 25.7 % | 0.6 % |

| 32 | Argentina | 45,195,774 | 0.93 % | 415,097 | 17 | 2,736,690 | 4,800 | 2.268 | 32 | 92.8 % | 0.6 % |

| 33 | Algeria | 43,851,044 | 1.85 % | 797,990 | 18 | 2,381,740 | -10,000 | 3.05 | 29 | 72.9 % | 0.6 % |

| 34 | Sudan | 43,849,260 | 2.42 % | 1,036,022 | 25 | 1,765,048 | -50,000 | 4.4345 | 20 | 35 % | 0.6 % |

| 35 | Ukraine | 43,733,762 | -0.59 % | -259,876 | 75 | 579,320 | 10,000 | 1.4435 | 41 | 69.4 % | 0.6 % |

| 36 | Iraq | 40,222,493 | 2.32 % | 912,710 | 93 | 434,320 | 7,834 | 3.682 | 21 | 73.1 % | 0.5 % |

| 37 | Afghanistan | 38,928,346 | 2.33 % | 886,592 | 60 | 652,860 | -62,920 | 4.5552 | 18 | 25.4 % | 0.5 % |

| 38 | Poland | 37,846,611 | -0.11 % | -41,157 | 124 | 306,230 | -29,395 | 1.4202 | 42 | 60.2 % | 0.5 % |

| 39 | Canada | 37,742,154 | 0.89 % | 331,107 | 4 | 9,093,510 | 242,032 | 1.525 | 41 | 81.3 % | 0.5 % |

| 40 | Morocco | 36,910,560 | 1.2 % | 438,791 | 83 | 446,300 | -51,419 | 2.42 | 30 | 63.8 % | 0.5 % |

| 41 | Saudi Arabia | 34,813,871 | 1.59 % | 545,343 | 16 | 2,149,690 | 134,979 | 2.34 | 32 | 84 % | 0.4 % |

| 42 | Uzbekistan | 33,469,203 | 1.48 % | 487,487 | 79 | 425,400 | -8,863 | 2.43 | 28 | 50.1 % | 0.4 % |

| 43 | Peru | 32,971,854 | 1.42 % | 461,401 | 26 | 1,280,000 | 99,069 | 2.27 | 31 | 79.1 % | 0.4 % |

| 44 | Angola | 32,866,272 | 3.27 % | 1,040,977 | 26 | 1,246,700 | 6,413 | 5.55 | 17 | 66.7 % | 0.4 % |

| 45 | Malaysia | 32,365,999 | 1.3 % | 416,222 | 99 | 328,550 | 50,000 | 2.0105 | 30 | 78.4 % | 0.4 % |

| 46 | Mozambique | 31,255,435 | 2.93 % | 889,399 | 40 | 786,380 | -5,000 | 4.8858 | 18 | 38.3 % | 0.4 % |

| 47 | Ghana | 31,072,940 | 2.15 % | 655,084 | 137 | 227,540 | -10,000 | 3.8928 | 22 | 56.7 % | 0.4 % |

| 48 | Yemen | 29,825,964 | 2.28 % | 664,042 | 56 | 527,970 | -30,000 | 3.8372 | 20 | 38.4 % | 0.4 % |

| 49 | Nepal | 29,136,808 | 1.85 % | 528,098 | 203 | 143,350 | 41,710 | 1.934 | 25 | 21.4 % | 0.4 % |

| 50 | Venezuela | 28,435,940 | -0.28 % | -79,889 | 32 | 882,050 | -653,249 | 2.283 | 30 | N.A. | 0.4 % |

| 51 | Madagascar | 27,691,018 | 2.68 % | 721,711 | 48 | 581,795 | -1,500 | 4.1085 | 20 | 38.5 % | 0.4 % |

| 52 | Cameroon | 26,545,863 | 2.59 % | 669,483 | 56 | 472,710 | -4,800 | 4.603 | 19 | 56.3 % | 0.3 % |

| 53 | Côte d’Ivoire | 26,378,274 | 2.57 % | 661,730 | 83 | 318,000 | -8,000 | 4.68 | 19 | 51.3 % | 0.3 % |

| 54 | North Korea | 25,778,816 | 0.44 % | 112,655 | 214 | 120,410 | -5,403 | 1.91 | 35 | 62.5 % | 0.3 % |

| 55 | Australia | 25,499,884 | 1.18 % | 296,686 | 3 | 7,682,300 | 158,246 | 1.8316 | 38 | 85.9 % | 0.3 % |

| 56 | Niger | 24,206,644 | 3.84 % | 895,929 | 19 | 1,266,700 | 4,000 | 6.95 | 15 | 16.5 % | 0.3 % |

| 57 | Taiwan | 23,816,775 | 0.18 % | 42,899 | 673 | 35,410 | 30,001 | 1.15 | 42 | 78.9 % | 0.3 % |

| 58 | Sri Lanka | 21,413,249 | 0.42 % | 89,516 | 341 | 62,710 | -97,986 | 2.2102 | 34 | 18.4 % | 0.3 % |

| 59 | Burkina Faso | 20,903,273 | 2.86 % | 581,895 | 76 | 273,600 | -25,000 | 5.2315 | 18 | 30.6 % | 0.3 % |

| 60 | Mali | 20,250,833 | 3.02 % | 592,802 | 17 | 1,220,190 | -40,000 | 5.9215 | 16 | 44 % | 0.3 % |

| 61 | Romania | 19,237,691 | -0.66 % | -126,866 | 84 | 230,170 | -73,999 | 1.6198 | 43 | 54.6 % | 0.2 % |

| 62 | Malawi | 19,129,952 | 2.69 % | 501,205 | 203 | 94,280 | -16,053 | 4.25 | 18 | 18.5 % | 0.2 % |

| 63 | Chile | 19,116,201 | 0.87 % | 164,163 | 26 | 743,532 | 111,708 | 1.65 | 35 | 84.8 % | 0.2 % |

| 64 | Kazakhstan | 18,776,707 | 1.21 % | 225,280 | 7 | 2,699,700 | -18,000 | 2.7638 | 31 | 57.7 % | 0.2 % |

| 65 | Zambia | 18,383,955 | 2.93 % | 522,925 | 25 | 743,390 | -8,000 | 4.6555 | 18 | 45.3 % | 0.2 % |

| 66 | Guatemala | 17,915,568 | 1.9 % | 334,096 | 167 | 107,160 | -9,215 | 2.8989 | 23 | 51.8 % | 0.2 % |

| 67 | Ecuador | 17,643,054 | 1.55 % | 269,392 | 71 | 248,360 | 36,400 | 2.44 | 28 | 63 % | 0.2 % |

| 68 | Syria | 17,500,658 | 2.52 % | 430,523 | 95 | 183,630 | -427,391 | 2.8398 | 26 | 60 % | 0.2 % |

| 69 | Netherlands | 17,134,872 | 0.22 % | 37,742 | 508 | 33,720 | 16,000 | 1.66 | 43 | 92.5 % | 0.2 % |

| 70 | Senegal | 16,743,927 | 2.75 % | 447,563 | 87 | 192,530 | -20,000 | 4.65 | 19 | 49.4 % | 0.2 % |

| 71 | Cambodia | 16,718,965 | 1.41 % | 232,423 | 95 | 176,520 | -30,000 | 2.5238 | 26 | 24.2 % | 0.2 % |

| 72 | Chad | 16,425,864 | 3 % | 478,988 | 13 | 1,259,200 | 2,000 | 5.7973 | 17 | 23.3 % | 0.2 % |

| 73 | Somalia | 15,893,222 | 2.92 % | 450,317 | 25 | 627,340 | -40,000 | 6.12 | 17 | 46.8 % | 0.2 % |

| 74 | Zimbabwe | 14,862,924 | 1.48 % | 217,456 | 38 | 386,850 | -116,858 | 3.6255 | 19 | 38.4 % | 0.2 % |

| 75 | Guinea | 13,132,795 | 2.83 % | 361,549 | 53 | 245,720 | -4,000 | 4.7384 | 18 | 38.6 % | 0.2 % |

| 76 | Rwanda | 12,952,218 | 2.58 % | 325,268 | 525 | 24,670 | -9,000 | 4.1 | 20 | 17.6 % | 0.2 % |

| 77 | Benin | 12,123,200 | 2.73 % | 322,049 | 108 | 112,760 | -2,000 | 4.8675 | 19 | 48.4 % | 0.2 % |

| 78 | Burundi | 11,890,784 | 3.12 % | 360,204 | 463 | 25,680 | 2,001 | 5.45 | 17 | 13.8 % | 0.2 % |

| 79 | Tunisia | 11,818,619 | 1.06 % | 123,900 | 76 | 155,360 | -4,000 | 2.2 | 33 | 70.1 % | 0.2 % |

| 80 | Bolivia | 11,673,021 | 1.39 % | 159,921 | 11 | 1,083,300 | -9,504 | 2.75 | 26 | 69.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 81 | Belgium | 11,589,623 | 0.44 % | 50,295 | 383 | 30,280 | 48,000 | 1.7148 | 42 | 98.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 82 | Haiti | 11,402,528 | 1.24 % | 139,451 | 414 | 27,560 | -35,000 | 2.96 | 24 | 56.9 % | 0.1 % |

| 83 | Cuba | 11,326,616 | -0.06 % | -6,867 | 106 | 106,440 | -14,400 | 1.6166 | 42 | 78.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 84 | South Sudan | 11,193,725 | 1.19 % | 131,612 | 18 | 610,952 | -174,200 | 4.7359 | 19 | 24.6 % | 0.1 % |

| 85 | Dominican Republic | 10,847,910 | 1.01 % | 108,952 | 225 | 48,320 | -30,000 | 2.36 | 28 | 84.5 % | 0.1 % |

| 86 | Czech Republic (Czechia) | 10,708,981 | 0.18 % | 19,772 | 139 | 77,240 | 22,011 | 1.6413 | 43 | 73.5 % | 0.1 % |

| 87 | Greece | 10,423,054 | -0.48 % | -50,401 | 81 | 128,900 | -16,000 | 1.3024 | 46 | 84.9 % | 0.1 % |

| 88 | Jordan | 10,203,134 | 1 % | 101,440 | 115 | 88,780 | 10,220 | 2.7723 | 24 | 91.5 % | 0.1 % |

| 89 | Portugal | 10,196,709 | -0.29 % | -29,478 | 111 | 91,590 | -6,000 | 1.288 | 46 | 66.5 % | 0.1 % |

| 90 | Azerbaijan | 10,139,177 | 0.91 % | 91,459 | 123 | 82,658 | 1,200 | 2.0835 | 32 | 56.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 91 | Sweden | 10,099,265 | 0.63 % | 62,886 | 25 | 410,340 | 40,000 | 1.85 | 41 | 88.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 92 | Honduras | 9,904,607 | 1.63 % | 158,490 | 89 | 111,890 | -6,800 | 2.4872 | 24 | 57.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 93 | United Arab Emirates | 9,890,402 | 1.23 % | 119,873 | 118 | 83,600 | 40,000 | 1.42 | 33 | 86.4 % | 0.1 % |

| 94 | Hungary | 9,660,351 | -0.25 % | -24,328 | 107 | 90,530 | 6,000 | 1.4911 | 43 | 71.7 % | 0.1 % |

| 95 | Tajikistan | 9,537,645 | 2.32 % | 216,627 | 68 | 139,960 | -20,000 | 3.6075 | 22 | 27.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 96 | Belarus | 9,449,323 | -0.03 % | -3,088 | 47 | 202,910 | 8,730 | 1.7099 | 40 | 79.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 97 | Austria | 9,006,398 | 0.57 % | 51,296 | 109 | 82,409 | 65,000 | 1.5292 | 43 | 57.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 98 | Papua New Guinea | 8,947,024 | 1.95 % | 170,915 | 20 | 452,860 | -800 | 3.5883 | 22 | 13.1 % | 0.1 % |

| 99 | Serbia | 8,737,371 | -0.4 % | -34,864 | 100 | 87,460 | 4,000 | 1.4612 | 42 | 56.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 100 | Israel | 8,655,535 | 1.6 % | 136,158 | 400 | 21,640 | 10,000 | 3.044 | 30 | 93.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 101 | Switzerland | 8,654,622 | 0.74 % | 63,257 | 219 | 39,516 | 52,000 | 1.535 | 43 | 74.1 % | 0.1 % |

| 102 | Togo | 8,278,724 | 2.43 % | 196,358 | 152 | 54,390 | -2,000 | 4.3515 | 19 | 43.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 103 | Sierra Leone | 7,976,983 | 2.1 % | 163,768 | 111 | 72,180 | -4,200 | 4.319 | 19 | 43.3 % | 0.1 % |

| 104 | Hong Kong | 7,496,981 | 0.82 % | 60,827 | 7,140 | 1,050 | 29,308 | 1.3262 | 45 | N.A. | 0.1 % |

| 105 | Laos | 7,275,560 | 1.48 % | 106,105 | 32 | 230,800 | -14,704 | 2.7 | 24 | 35.7 % | 0.1 % |

| 106 | Paraguay | 7,132,538 | 1.25 % | 87,902 | 18 | 397,300 | -16,556 | 2.4455 | 26 | 61.6 % | 0.1 % |

| 107 | Bulgaria | 6,948,445 | -0.74 % | -51,674 | 64 | 108,560 | -4,800 | 1.5584 | 45 | 75.6 % | 0.1 % |

| 108 | Libya | 6,871,292 | 1.38 % | 93,840 | 4 | 1,759,540 | -1,999 | 2.25 | 29 | 78.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 109 | Lebanon | 6,825,445 | -0.44 % | -30,268 | 667 | 10,230 | -30,012 | 2.09 | 30 | 78.4 % | 0.1 % |

| 110 | Nicaragua | 6,624,554 | 1.21 % | 79,052 | 55 | 120,340 | -21,272 | 2.42 | 26 | 57.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 111 | Kyrgyzstan | 6,524,195 | 1.69 % | 108,345 | 34 | 191,800 | -4,000 | 3 | 26 | 35.6 % | 0.1 % |

| 112 | El Salvador | 6,486,205 | 0.51 % | 32,652 | 313 | 20,720 | -40,539 | 2.0529 | 28 | 73.4 % | 0.1 % |

| 113 | Turkmenistan | 6,031,200 | 1.5 % | 89,111 | 13 | 469,930 | -5,000 | 2.785 | 27 | 52.5 % | 0.1 % |

| 114 | Singapore | 5,850,342 | 0.79 % | 46,005 | 8,358 | 700 | 27,028 | 1.209 | 42 | N.A. | 0.1 % |

| 115 | Denmark | 5,792,202 | 0.35 % | 20,326 | 137 | 42,430 | 15,200 | 1.7621 | 42 | 88.2 % | 0.1 % |

| 116 | Finland | 5,540,720 | 0.15 % | 8,564 | 18 | 303,890 | 14,000 | 1.53 | 43 | 86.1 % | 0.1 % |

| 117 | Congo | 5,518,087 | 2.56 % | 137,579 | 16 | 341,500 | -4,000 | 4.45 | 19 | 69.9 % | 0.1 % |

| 118 | Slovakia | 5,459,642 | 0.05 % | 2,629 | 114 | 48,088 | 1,485 | 1.502 | 41 | 53.7 % | 0.1 % |

| 119 | Norway | 5,421,241 | 0.79 % | 42,384 | 15 | 365,268 | 28,000 | 1.68 | 40 | 83.4 % | 0.1 % |

| 120 | Oman | 5,106,626 | 2.65 % | 131,640 | 16 | 309,500 | 87,400 | 2.93 | 31 | 87 % | 0.1 % |

| 121 | State of Palestine | 5,101,414 | 2.41 % | 119,994 | 847 | 6,020 | -10,563 | 3.6677 | 21 | 80 % | 0.1 % |

| 122 | Costa Rica | 5,094,118 | 0.92 % | 46,557 | 100 | 51,060 | 4,200 | 1.7639 | 33 | 80 % | 0.1 % |

| 123 | Liberia | 5,057,681 | 2.44 % | 120,307 | 53 | 96,320 | -5,000 | 4.35 | 19 | 52.6 % | 0.1 % |

| 124 | Ireland | 4,937,786 | 1.13 % | 55,291 | 72 | 68,890 | 23,604 | 1.8409 | 38 | 63 % | 0.1 % |

| 125 | Central African Republic | 4,829,767 | 1.78 % | 84,582 | 8 | 622,980 | -40,000 | 4.7541 | 18 | 43 % | 0.1 % |

| 126 | New Zealand | 4,822,233 | 0.82 % | 39,170 | 18 | 263,310 | 14,881 | 1.9 | 38 | 86.9 % | 0.1 % |

| 127 | Mauritania | 4,649,658 | 2.74 % | 123,962 | 5 | 1,030,700 | 5,000 | 4.585 | 20 | 56.9 % | 0.1 % |

| 128 | Panama | 4,314,767 | 1.61 % | 68,328 | 58 | 74,340 | 11,200 | 2.4688 | 30 | 68 % | 0.1 % |

| 129 | Kuwait | 4,270,571 | 1.51 % | 63,488 | 240 | 17,820 | 39,520 | 2.1 | 37 | N.A. | 0.1 % |

| 130 | Croatia | 4,105,267 | -0.61 % | -25,037 | 73 | 55,960 | -8,001 | 1.4461 | 44 | 57.7 % | 0.1 % |

| 131 | Moldova | 4,033,963 | -0.23 % | -9,300 | 123 | 32,850 | -1,387 | 1.2552 | 38 | 42.7 % | 0.1 % |

| 132 | Georgia | 3,989,167 | -0.19 % | -7,598 | 57 | 69,490 | -10,000 | 2.0615 | 38 | 58.1 % | 0.1 % |

| 133 | Eritrea | 3,546,421 | 1.41 % | 49,304 | 35 | 101,000 | -39,858 | 4.1 | 19 | 63.3 % | 0 % |

| 134 | Uruguay | 3,473,730 | 0.35 % | 11,996 | 20 | 175,020 | -3,000 | 1.98 | 36 | 96.1 % | 0 % |

| 135 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 3,280,819 | -0.61 % | -20,181 | 64 | 51,000 | -21,585 | 1.27 | 43 | 52.3 % | 0 % |

| 136 | Mongolia | 3,278,290 | 1.65 % | 53,123 | 2 | 1,553,560 | -852 | 2.9023 | 28 | 67.2 % | 0 % |

| 137 | Armenia | 2,963,243 | 0.19 % | 5,512 | 104 | 28,470 | -4,998 | 1.7559 | 35 | 62.8 % | 0 % |

| 138 | Jamaica | 2,961,167 | 0.44 % | 12,888 | 273 | 10,830 | -11,332 | 1.991 | 31 | 55.4 % | 0 % |

| 139 | Qatar | 2,881,053 | 1.73 % | 48,986 | 248 | 11,610 | 40,000 | 1.8805 | 32 | 96.2 % | 0 % |

| 140 | Albania | 2,877,797 | -0.11 % | -3,120 | 105 | 27,400 | -14,000 | 1.62 | 36 | 63.5 % | 0 % |

| 141 | Puerto Rico | 2,860,853 | -2.47 % | -72,555 | 323 | 8,870 | -97,986 | 1.22 | 44 | N.A. | 0 % |

| 142 | Lithuania | 2,722,289 | -1.35 % | -37,338 | 43 | 62,674 | -32,780 | 1.6698 | 45 | 71.3 % | 0 % |

| 143 | Namibia | 2,540,905 | 1.86 % | 46,375 | 3 | 823,290 | -4,806 | 3.4153 | 22 | 55.2 % | 0 % |

| 144 | Gambia | 2,416,668 | 2.94 % | 68,962 | 239 | 10,120 | -3,087 | 5.25 | 18 | 59.4 % | 0 % |

| 145 | Botswana | 2,351,627 | 2.08 % | 47,930 | 4 | 566,730 | 3,000 | 2.8944 | 24 | 72.8 % | 0 % |

| 146 | Gabon | 2,225,734 | 2.45 % | 53,155 | 9 | 257,670 | 3,260 | 4 | 23 | 87.1 % | 0 % |

| 147 | Lesotho | 2,142,249 | 0.8 % | 16,981 | 71 | 30,360 | -10,047 | 3.1641 | 24 | 31.5 % | 0 % |

| 148 | North Macedonia | 2,083,374 | -0 % | -85 | 83 | 25,220 | -1,000 | 1.5 | 39 | 58.6 % | 0 % |

| 149 | Slovenia | 2,078,938 | 0.01 % | 284 | 103 | 20,140 | 2,000 | 1.6 | 45 | 55.2 % | 0 % |

| 150 | Guinea-Bissau | 1,968,001 | 2.45 % | 47,079 | 70 | 28,120 | -1,399 | 4.51 | 19 | 44.9 % | 0 % |

| 151 | Latvia | 1,886,198 | -1.08 % | -20,545 | 30 | 62,200 | -14,837 | 1.7167 | 44 | 68.6 % | 0 % |

| 152 | Bahrain | 1,701,575 | 3.68 % | 60,403 | 2,239 | 760 | 47,800 | 1.9982 | 32 | 89.3 % | 0 % |

| 153 | Equatorial Guinea | 1,402,985 | 3.47 % | 46,999 | 50 | 28,050 | 16,000 | 4.5543 | 22 | 73.3 % | 0 % |

| 154 | Trinidad and Tobago | 1,399,488 | 0.32 % | 4,515 | 273 | 5,130 | -800 | 1.7299 | 36 | 52.4 % | 0 % |

| 155 | Estonia | 1,326,535 | 0.07 % | 887 | 31 | 42,390 | 3,911 | 1.5878 | 42 | 67.9 % | 0 % |

| 156 | Timor-Leste | 1,318,445 | 1.96 % | 25,326 | 89 | 14,870 | -5,385 | 4.1 | 21 | 32.8 % | 0 % |

| 157 | Mauritius | 1,271,768 | 0.17 % | 2,100 | 626 | 2,030 | 0 | 1.3885 | 37 | 40.8 % | 0 % |

| 158 | Cyprus | 1,207,359 | 0.73 % | 8,784 | 131 | 9,240 | 5,000 | 1.3375 | 37 | 66.8 % | 0 % |

| 159 | Eswatini | 1,160,164 | 1.05 % | 12,034 | 67 | 17,200 | -8,353 | 3.0257 | 21 | 30 % | 0 % |

| 160 | Djibouti | 988,000 | 1.48 % | 14,440 | 43 | 23,180 | 900 | 2.7577 | 27 | 79 % | 0 % |

| 161 | Fiji | 896,445 | 0.73 % | 6,492 | 49 | 18,270 | -6,202 | 2.7874 | 28 | 59.1 % | 0 % |

| 162 | Réunion | 895,312 | 0.72 % | 6,385 | 358 | 2,500 | -1,256 | 2.2735 | 36 | 99.8 % | 0 % |

| 163 | Comoros | 869,601 | 2.2 % | 18,715 | 467 | 1,861 | -2,000 | 4.2365 | 20 | 29.4 % | 0 % |

| 164 | Guyana | 786,552 | 0.48 % | 3,786 | 4 | 196,850 | -6,000 | 2.4728 | 27 | 26.9 % | 0 % |

| 165 | Bhutan | 771,608 | 1.12 % | 8,516 | 20 | 38,117 | 320 | 2 | 28 | 45.8 % | 0 % |

| 166 | Solomon Islands | 686,884 | 2.55 % | 17,061 | 25 | 27,990 | -1,600 | 4.435 | 20 | 23.2 % | 0 % |

| 167 | Macao | 649,335 | 1.39 % | 8,890 | 21,645 | 30 | 5,000 | 1.2 | 39 | N.A. | 0 % |

| 168 | Montenegro | 628,066 | 0.01 % | 79 | 47 | 13,450 | -480 | 1.7506 | 39 | 67.6 % | 0 % |

| 169 | Luxembourg | 625,978 | 1.66 % | 10,249 | 242 | 2,590 | 9,741 | 1.45 | 40 | 88.2 % | 0 % |

| 170 | Western Sahara | 597,339 | 2.55 % | 14,876 | 2 | 266,000 | 5,582 | 2.4149 | 28 | 86.8 % | 0 % |

| 171 | Suriname | 586,632 | 0.9 % | 5,260 | 4 | 156,000 | -1,000 | 2.4298 | 29 | 65.1 % | 0 % |

| 172 | Cabo Verde | 555,987 | 1.1 % | 6,052 | 138 | 4,030 | -1,342 | 2.2885 | 28 | 68 % | 0 % |

| 173 | Micronesia | 548,914 | 1 % | 5,428 | 784 | 700 | -2,957 | 2.858000189 | 27 | 68.2 % | 0 % |

| 174 | Maldives | 540,544 | 1.81 % | 9,591 | 1,802 | 300 | 11,370 | 1.88 | 30 | 34.5 % | 0 % |

| 175 | Malta | 441,543 | 0.27 % | 1,171 | 1,380 | 320 | 900 | 1.45 | 43 | 93.2 % | 0 % |

| 176 | Brunei | 437,479 | 0.97 % | 4,194 | 83 | 5,270 | 0 | 1.8482 | 32 | 79.5 % | 0 % |

| 177 | Guadeloupe | 400,124 | 0.02 % | 68 | 237 | 1,690 | -1,440 | 2.17 | 44 | N.A. | 0 % |

| 178 | Belize | 397,628 | 1.86 % | 7,275 | 17 | 22,810 | 1,200 | 2.32 | 25 | 46.1 % | 0 % |

| 179 | Bahamas | 393,244 | 0.97 % | 3,762 | 39 | 10,010 | 1,000 | 1.76 | 32 | 86.1 % | 0 % |

| 180 | Martinique | 375,265 | -0.08 % | -289 | 354 | 1,060 | -960 | 1.88 | 47 | 91.6 % | 0 % |

| 181 | Iceland | 341,243 | 0.65 % | 2,212 | 3 | 100,250 | 380 | 1.77 | 37 | 94.4 % | 0 % |

| 182 | Vanuatu | 307,145 | 2.42 % | 7,263 | 25 | 12,190 | 120 | 3.8 | 21 | 24.4 % | 0 % |

| 183 | French Guiana | 298,682 | 2.7 % | 7,850 | 4 | 82,200 | 1,200 | 3.36 | 25 | 87.3 % | 0 % |

| 184 | Barbados | 287,375 | 0.12 % | 350 | 668 | 430 | -79 | 1.62 | 40 | 31.2 % | 0 % |

| 185 | New Caledonia | 285,498 | 0.97 % | 2,748 | 16 | 18,280 | 502 | 1.97 | 34 | 71.9 % | 0 % |

| 186 | French Polynesia | 280,908 | 0.58 % | 1,621 | 77 | 3,660 | -1,000 | 1.95 | 34 | 64.1 % | 0 % |

| 187 | Mayotte | 272,815 | 2.5 % | 6,665 | 728 | 375 | 0 | 3.7289 | 20 | 45.8 % | 0 % |

| 188 | Sao Tome & Principe | 219,159 | 1.91 % | 4,103 | 228 | 960 | -1,680 | 4.35 | 19 | 74 % | 0 % |

| 189 | Samoa | 198,414 | 0.67 % | 1,317 | 70 | 2,830 | -2,803 | 3.9029 | 22 | 18 % | 0 % |

| 190 | Saint Lucia | 183,627 | 0.46 % | 837 | 301 | 610 | 0 | 1.4442 | 34 | 18.6 % | 0 % |

| 191 | Channel Islands | 173,863 | 0.93 % | 1,604 | 915 | 190 | 1,351 | 1.502 | 43 | 29.8 % | 0 % |

| 192 | Guam | 168,775 | 0.89 % | 1,481 | 313 | 540 | -506 | 2.3193 | 31 | 94.9 % | 0 % |

| 193 | Curaçao | 164,093 | 0.41 % | 669 | 370 | 444 | 515 | 1.76 | 42 | 88.7 % | 0 % |

| 194 | Kiribati | 119,449 | 1.57 % | 1,843 | 147 | 810 | -800 | 3.5836 | 23 | 57 % | 0 % |

| 195 | Grenada | 112,523 | 0.46 % | 520 | 331 | 340 | -200 | 2.0732 | 32 | 35.5 % | 0 % |

| 196 | St. Vincent & Grenadines | 110,940 | 0.32 % | 351 | 284 | 390 | -200 | 1.9019 | 33 | 52.9 % | 0 % |

| 197 | Aruba | 106,766 | 0.43 % | 452 | 593 | 180 | 201 | 1.9 | 41 | 43.6 % | 0 % |

| 198 | Tonga | 105,695 | 1.15 % | 1,201 | 147 | 720 | -800 | 3.5763 | 22 | 24.3 % | 0 % |

| 199 | U.S. Virgin Islands | 104,425 | -0.15 % | -153 | 298 | 350 | -451 | 2.0458 | 43 | 96.3 % | 0 % |

| 200 | Seychelles | 98,347 | 0.62 % | 608 | 214 | 460 | -200 | 2.46 | 34 | 56.2 % | 0 % |

| 201 | Antigua and Barbuda | 97,929 | 0.84 % | 811 | 223 | 440 | 0 | 2 | 34 | 26.2 % | 0 % |

| 202 | Isle of Man | 85,033 | 0.53 % | 449 | 149 | 570 | N.A. | N.A. | 53.4 % | 0 % | |

| 203 | Andorra | 77,265 | 0.16 % | 123 | 164 | 470 | N.A. | N.A. | 87.8 % | 0 % | |

| 204 | Dominica | 71,986 | 0.25 % | 178 | 96 | 750 | N.A. | N.A. | 74.1 % | 0 % | |

| 205 | Cayman Islands | 65,722 | 1.19 % | 774 | 274 | 240 | N.A. | N.A. | 97.2 % | 0 % | |

| 206 | Bermuda | 62,278 | -0.36 % | -228 | 1,246 | 50 | N.A. | N.A. | 97.4 % | 0 % | |

| 207 | Marshall Islands | 59,190 | 0.68 % | 399 | 329 | 180 | N.A. | N.A. | 70 % | 0 % | |

| 208 | Northern Mariana Islands | 57,559 | 0.6 % | 343 | 125 | 460 | N.A. | N.A. | 88.3 % | 0 % | |

| 209 | Greenland | 56,770 | 0.17 % | 98 | 0 | 410,450 | N.A. | N.A. | 87.3 % | 0 % | |

| 210 | American Samoa | 55,191 | -0.22 % | -121 | 276 | 200 | N.A. | N.A. | 88.1 % | 0 % | |

| 211 | Saint Kitts & Nevis | 53,199 | 0.71 % | 376 | 205 | 260 | N.A. | N.A. | 32.9 % | 0 % | |

| 212 | Faeroe Islands | 48,863 | 0.38 % | 185 | 35 | 1,396 | N.A. | N.A. | 43.3 % | 0 % | |

| 213 | Sint Maarten | 42,876 | 1.15 % | 488 | 1,261 | 34 | N.A. | N.A. | 96.5 % | 0 % | |

| 214 | Monaco | 39,242 | 0.71 % | 278 | 26,337 | 1 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | |

| 215 | Turks and Caicos | 38,717 | 1.38 % | 526 | 41 | 950 | N.A. | N.A. | 89.3 % | 0 % | |

| 216 | Saint Martin | 38,666 | 1.75 % | 664 | 730 | 53 | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | 0 % | |

| 217 | Liechtenstein | 38,128 | 0.29 % | 109 | 238 | 160 | N.A. | N.A. | 14.6 % | 0 % | |

| 218 | San Marino | 33,931 | 0.21 % | 71 | 566 | 60 | N.A. | N.A. | 97.1 % | 0 % | |

| 219 | Gibraltar | 33,691 | -0.03 % | -10 | 3,369 | 10 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | |

| 220 | British Virgin Islands | 30,231 | 0.67 % | 201 | 202 | 150 | N.A. | N.A. | 52.4 % | 0 % | |

| 221 | Caribbean Netherlands | 26,223 | 0.94 % | 244 | 80 | 328 | N.A. | N.A. | 75 % | 0 % | |

| 222 | Palau | 18,094 | 0.48 % | 86 | 39 | 460 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | |

| 223 | Cook Islands | 17,564 | 0.09 % | 16 | 73 | 240 | N.A. | N.A. | 75.3 % | 0 % | |

| 224 | Anguilla | 15,003 | 0.9 % | 134 | 167 | 90 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | |

| 225 | Tuvalu | 11,792 | 1.25 % | 146 | 393 | 30 | N.A. | N.A. | 62.4 % | 0 % | |

| 226 | Wallis & Futuna | 11,239 | -1.69 % | -193 | 80 | 140 | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | 0 % | |

| 227 | Nauru | 10,824 | 0.63 % | 68 | 541 | 20 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | |

| 228 | Saint Barthelemy | 9,877 | 0.3 % | 30 | 470 | 21 | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | 0 % | |

| 229 | Saint Helena | 6,077 | 0.3 % | 18 | 16 | 390 | N.A. | N.A. | 27.2 % | 0 % | |

| 230 | Saint Pierre & Miquelon | 5,794 | -0.48 % | -28 | 25 | 230 | N.A. | N.A. | 99.8 % | 0 % | |

| 231 | Montserrat | 4,992 | 0.06 % | 3 | 50 | 100 | N.A. | N.A. | 9.6 % | 0 % | |

| 232 | Falkland Islands | 3,480 | 3.05 % | 103 | 0 | 12,170 | N.A. | N.A. | 66 % | 0 % | |

| 233 | Niue | 1,626 | 0.68 % | 11 | 6 | 260 | N.A. | N.A. | 46.4 % | 0 % | |

| 234 | Tokelau | 1,357 | 1.27 % | 17 | 136 | 10 | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % | 0 % | |

| 235 | Holy See | 801 | 0.25 % | 2 | 2,003 | 0 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 0 % |

How many people have ever lived on earth?

It was written during the 1970s that 75% of the people who had ever been born were alive at that moment. This was grossly false.

Assuming that we start counting from about 50,000 B.C., the time when modern Homo sapiens appeared on the earth (and not from 700,000 B.C. when the ancestors of Homo sapiens appeared, or several million years ago when hominids were present), taking into account that all population data are a rough estimate, and assuming a constant growth rate applied to each period up to modern times, it has been estimated that a total of approximately 106 billion people have been born since the dawn of the human species, making the population currently alive roughly 6% of all people who have ever lived on planet Earth.

Others have estimated the number of human beings who have ever lived to be anywhere from 45 billion to 125 billion, with most estimates falling into the range of 90 to 110 billion humans.

World Population clock: sources and methodology

The world population counter displayed on Worldometer takes into consideration data from two major sources: the United Nations and the U.S. Census Bureau.

- The United Nations Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs every two years calculates, updates, and publishes estimates of total population in its World Population Prospects series. These population estimates and projections provide the standard and consistent set of population figures that are used throughout the United Nations system.

The World Population Prospect: the 2022 Revision provides the most recent data available (released in July of 2022). Estimates and projected world population and country specific populations are given from 1950 through 2100 and are released every two years. Worldometer, as it is common practice, utilizes the medium fertility estimates.

Data underlying the population estimates are national and sub national census data and data on births, deaths, and migrants available from national sources and publications, as well as from questionnaires. For all countries, census and registration data are evaluated and, if necessary, adjusted for incompleteness by the Population Division as part of its preparations of the official United Nations population estimates and projections.

- The International Programs Center at the U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division also develops estimates and projections based on analysis of available data (based on census, survey, and administrative information) on population, fertility, mortality, and migration for each country or area of the world. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, world population reached 7 billion on March 12, 2012.

For most countries adjustment of the data is necessary to correct for errors, omissions, and inconsistencies in the data. Finally, since most recent data for a single country is often at least two years old, the current world population figure is necessarily a projection of past data based on assumed trends. As new data become available, assumptions and data are reevaluated and past conclusions and current figures may be modified.

For information about how these estimates and projections are made by the U.S. Census Bureau, see the Population Estimates and Projections Methodology.

Why Worldometer’s Population Clock is the most accurate

The above world population clock is based on the latest estimates released in July of 2022 by the United Nations. It will show the same number wherever you are in the world and whatever time you set on your PC.

Visitors around the world visiting a PC clock based counter, instead, will see different numbers depending on where they are located. This is the case with other world population clocks — such as the one hosted on a United Nations website, reaching 8 billion in 24 different instances (one per hour) on November 15, 2022, when each local time zone reached 12:10:08. Similarly, in 2011, the clocks on a UN website and on National Geographic — showed 7 billion whenever the visitor’s locally set PC clocks reached 4:21:10 AM on October 31, 2011.

Obviously, the UN data is based on estimates and can’t be 100% accurate, so in all honesty nobody can possibly say with any degree of certainty on which day world population reached 7 billion (or any other exact number), let alone at what time. But once an estimate is made (based on the best data and analysis available), the world population clock should be showing the same number at any given time anywhere around the world.

|

8,075,459,019 |

Current population |

|

4,074,514,776 |

Current male population (50.5%) |

|

4,000,944,242 |

Current female population (49.5%) |

|

44,051,390 |

Births year to date |

|

138,498 |

Births today |

|

17,209,211 |

Deaths year to date |

|

54,106 |

Deaths today |

|

0 |

Net migration year to date |

|

0 |

Net migration today |

|

26,842,179 |

Population growth year to date |

|

84,392 |

Population growth today |

14-04-2023 08:47:36

Contents

- Top 5 death causes clock

- World population clock

- Top 20 countries

- Population in 2023

- Demographics in 2022

- Population density

- Global religions

- Global age structure

- Global life expectancy

- Global literacy

- World historical population

- Population projection

Top 5 death causes in the World

| today | This year | |

|---|---|---|

| Coronary artery disease | ||

|

Connecting . . . |

15.51 % |

Connecting . . . |

| Stroke | ||

|

Connecting . . . |

11.06 % |

Connecting . . . |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | ||

|

Connecting . . . |

5.65 % |

Connecting . . . |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||

|

Connecting . . . |

5.62 % |

Connecting . . . |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung cancers | ||

|

Connecting . . . |

3.00 % |

Connecting . . . |

Source: deathmeters.info

World population — is the total number of humans currently living in the World.

As of today, the total population of the world is around 8.08 billion people.

The first billion was reached around 1800 and in just 200 years we reached 7 billion.

According to Population Division of United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- 1 billion — 1804

- 2 billion — 1927 (in 123 years)

- 3 billion — 1960 (in 33 years)

- 4 billion — 1974 (in 14 years)

- 5 billion — 1987 (in 13 years)

- 6 billion — October 12, 1999 (in 12 years)

- 7 billion — October 31, 2011 (in 12 years)

World population is expected to reach 8 billion people in 2023 according to our estimates.

Currently, the world population is increasing by more than 90 million per year.

The Global sex ratio is 1.018. It means that we have slightly more men then women.

The median age of the world’s population is estimated to be 31 years in 2020 (30.3 and 31.8 for male and female accordingly)

More than 70% of the world population live in 20 most populous countries of the world. There are just 2 countries in the world with a population more than 1 billion people: China and India. About 36 % of the World population live just in these two countries. Despite the fact that China is curently the most populous country in the world, India’s population growths much faster. And in 2023 India is expected to become the most populous country in the world.

More than half of the world’s population identify with a religious group. The biggest groups are: Christianity (32%) and Islam (24%).

Top 20 most populous countries (14-04-2023)

| 1 |  |

China | 1,461,045,393 | 18.09% |

| 2 |  |

India | 1,430,834,954 | 17.72% |

| 3 |  |

United States of America (USA) | 338,267,913 | 4.19% |

| 4 |  |

Indonesia | 283,666,973 | 3.51% |

| 5 |  |

Pakistan | 234,214,437 | 2.90% |

| 6 |  |

Nigeria | 221,948,529 | 2.75% |

| 7 |  |

Brazil | 218,202,414 | 2.70% |

| 8 |  |

Bangladesh | 170,417,652 | 2.11% |

| 9 |  |

Russian Federation | 146,099,960 | 1.81% |

| 10 |  |

Mexico | 134,109,402 | 1.66% |

| 11 |  |

Japan | 126,177,445 | 1.56% |

| 12 |  |

Ethiopia | 123,239,007 | 1.53% |

| 13 |  |

Philippines | 114,606,638 | 1.42% |

| 14 |  |

Egypt | 108,813,493 | 1.35% |

| 15 |  |

Vietnam | 100,511,819 | 1.24% |

| 16 |  |

Democratic Republic of the Congo | 97,685,698 | 1.21% |

| 17 |  |

Turkey | 88,615,502 | 1.10% |

| 18 |  |

Iran | 86,975,836 | 1.08% |

| 19 |  |

Germany | 83,824,319 | 1.04% |

| 20 |  |

Thailand | 70,579,666 | 0.87% |

This list includes 20 most populous countries in the World. Approximately 5.64 billion people live in these twenty countries, or around 70% of the world’s population.

See also: Full List of countries and dependent territories of the World by population

World population 2023

The population of the world is projected to increase by 100,752,643 people in 2023 and reach 8,147,701,961 in the end of the year. The natural increase is expected to be positive, as the number of births will exceed the number of deaths by 100,254,836.

Population change rates in 2023

According to our estimations, daily change rates of world population in 2023 will be the following:

- 447,586 live births average per day (18,649.42 in an hour)

- 172,915 deaths average per day (7,204.80 in an hour)

The population of World will be increasing by 276,035 persons daily in 2023.

Demographics of the World 2022

As of 1 January 2023, the population of the world was estimated to be 8,046,949,318.

This is an increase of 1.24 % (98,830,797 people) compared to population of 7,948,118,521 the year before.

In 2022 the natural increase was positive, as the number of births exceeded the number of deaths by 98,415,064.

Below are the key figures for the world population in 2022:

- 160,747,971 live births

- 62,332,907 deaths

- 4,060,130,059 males as of 31 December 2022

- 3,986,819,259 females as of 31 December 2022

- 4,345,352,632 people live in urban areas (54 % of total world population)

- 3,701,596,686 people live in rural areas (46 % of total world population)

Growth Rate 1952 — 2023

World population density

The world population density is 59.1 people per square kilometer (153.1 per mi2) as of April 2023.

This number is calculated using 8,046,949,318 people as the world population and 136,120,354 km2 (52,556,368 mi2)as Earth’s total area.

This is the sum of land and water areas within international boundaries and coastlines of all the countries in the world.

Since the Earth’s total area is about 510 million square kilometers, the world population density can be calculated in several ways:

- 15.8 people/km2 (40.9/mi2) — the Earth’s total area (including land and water) is 510,072,000 km2 (196,939,921 mi2).

- 53.5 people/km2 (138.5/mi2) — the Earth’s land area.

This includes all continental and island land area as well as Antarctica. The area in that case is 150,461,685 km2 (58,093,588 mi2). - 59.1 people/km2 (153.1/mi2) —

sum of land and water areas within international boundaries and coastlines of all the countries in the world. The area in that case is 136,120,354 km2 (52,556,368 mi2).

See also:

List of countries by surface area and density by United Nations Statistics Division

Map and list of the world by density of population at worldstat.info

Religion of the World

| Religion | Number of followers | Percentage of total population |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2,549,761,536 | 31.7 % |

| Islam | 2,013,192,037 | 25.0 % |

| Religiously Unaffiliated | 1,221,465,803 | 15.2 % |

| Hinduism | 1,198,451,609 | 14.9 % |

| Buddhism | 529,055,084 | 6.6 % |

| Folk or traditional religions | 451,759,687 | 5.6 % |

| Other | 68,003,229 | 0.8 % |

| Judaism | 15,260,333 | 0.2 % |

Source: Pew Research Center. The Global Religious Landscape

Number of followers estimated by Countrymeters

Global age structure

As of the beginning of 2023 according to our estimates the world had the following population age distribution:

| — percentage of population under 15 | |

| — percentage of population between 15 and 64 years old | |

| — percentage of population 65+ |

In absolute figures (estimate):

- 2,084,569,466 young people under 15 years old (

1,077,744,528 males / 1,006,828,378 females) - 5,081,333,771 persons between 15 and 64 years old (

2,569,398,787 males / 2,511,954,917 females) - 590,141,646 persons above 64 years old (

261,787,349 males / 328,342,163 females)

We prepared a simplified model of the population distribution pyramid which is broken down into 3 main age groups.

The groups are the same as we used above: population under 15, between 15 and 64 and population which is over 65 year old.

| 65+ |

| 15-64 |

| 0-14 |

| male | female |

As we can see the World population pyramid has an expanding type. This type of pyramid is common for developing countries with declining fertility rate but still high birth and death rates.

World life expectancy

Life expectancy at birth is one of the most important demographic indicator.

It shows the number of years a newborn infant would live assuming that birth and death rates will remain at the same level during the whole lifetime.

According to Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations,

life expectancy at birth for the world as a whole increased from 65 years in 1990-1995 to 70 years in 2010-2015.

Although wide disparities persist such that the average length of life in Africa in 2010-2015, for example,

is 12 years shorter than the global average and 21 years shorter than in Northern America — see figure below.

Figure: Life expectancy at birth by major areas

Global literacy

According to our estimates 4,894,412,455 persons or 86.3% of adult population (aged 15 years and above) in the world

are able to read and write.

Accordingly about 777,070,761 adults are illiterate.

Literacy rate for adult male population is 89.96% (2,546,850,112 persons). 284,336,024 are illiterate.

Literacy rate for adult female population is 82.65% (2,347,562,343 persons). 492,734,737 are illiterate.

Youth literacy rates are 92.81% and 90.13% for males and females accordingly.

The overall youth literacy rate is 91.51%. Youth literacy rate definition covers the population between the ages of 15 to 24 years.

Source: The estimation data for section «World

population literacy» is based on the latest data published by UNESCO Institute for Statistics (retrieved March 13, 2016)

World historical population (1951 — 2023)

The data is given as of 1st of January of an year.

World population history

| Year | Population | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 2,560,406,604 | N/A % |

| 1952 | 2,607,553,997 | 1.84 % |

| 1953 | 2,654,405,334 | 1.80 % |

| 1954 | 2,701,399,657 | 1.77 % |

| 1955 | 2,749,108,690 | 1.77 % |

| 1956 | 2,797,843,787 | 1.77 % |

| 1957 | 2,848,060,613 | 1.79 % |

| 1958 | 2,899,688,319 | 1.81 % |

| 1959 | 2,952,829,301 | 1.83 % |

| 1960 | 3,008,337,351 | 1.88 % |

| 1961 | 3,064,572,222 | 1.87 % |

| 1962 | 3,122,342,316 | 1.89 % |

| 1963 | 3,181,956,882 | 1.91 % |

| 1964 | 3,243,686,348 | 1.94 % |

| 1965 | 3,308,102,778 | 1.99 % |

| 1966 | 3,375,113,774 | 2.03 % |

| 1967 | 3,444,745,982 | 2.06 % |

| 1968 | 3,516,519,814 | 2.08 % |

| 1969 | 3,590,108,316 | 2.09 % |

| 1970 | 3,664,557,571 | 2.07 % |

| 1971 | 3,739,627,183 | 2.05 % |

| 1972 | 3,815,162,572 | 2.02 % |

| 1973 | 3,891,308,177 | 2.00 % |

| 1974 | 3,967,410,338 | 1.96 % |

| 1975 | 4,043,288,795 | 1.91 % |

| 1976 | 4,118,650,244 | 1.86 % |

| 1977 | 4,193,794,699 | 1.82 % |

| 1978 | 4,268,758,390 | 1.79 % |

| 1979 | 4,344,292,968 | 1.77 % |

| 1980 | 4,420,957,100 | 1.76 % |

| 1981 | 4,499,346,118 | 1.77 % |

| 1982 | 4,579,073,550 | 1.77 % |

| 1983 | 4,660,399,347 | 1.78 % |

| 1984 | 4,743,637,344 | 1.79 % |

| 1985 | 4,829,473,423 | 1.81 % |

| 1986 | 4,917,794,826 | 1.83 % |

| 1987 | 5,008,635,951 | 1.85 % |

| 1988 | 5,100,973,495 | 1.84 % |

| 1989 | 5,193,588,212 | 1.82 % |

| 1990 | 5,284,512,394 | 1.75 % |

| 1991 | 5,372,958,607 | 1.67 % |

| 1992 | 5,458,709,589 | 1.60 % |

| 1993 | 5,542,505,600 | 1.54 % |

| 1994 | 5,624,649,220 | 1.48 % |

| 1995 | 5,705,987,737 | 1.45 % |

| 1996 | 5,786,776,201 | 1.42 % |

| 1997 | 5,867,328,462 | 1.39 % |

| 1998 | 5,947,157,474 | 1.36 % |

| 1999 | 6,026,548,295 | 1.33 % |

| 2000 | 6,105,725,477 | 1.31 % |

| 2001 | 6,185,028,231 | 1.30 % |

| 2002 | 6,264,168,230 | 1.28 % |

| 2003 | 6,343,448,736 | 1.27 % |

| 2004 | 6,423,033,915 | 1.25 % |

| 2005 | 6,503,507,778 | 1.25 % |

| 2006 | 6,584,702,481 | 1.25 % |

| 2007 | 6,666,737,393 | 1.25 % |

| 2008 | 6,749,422,837 | 1.24 % |

| 2009 | 6,832,961,603 | 1.24 % |

| 2010 | 6,916,843,009 | 1.23 % |

| 2011 | 7,001,071,861 | 1.22 % |

| 2012 | 7,085,473,969 | 1.21 % |

| 2013 | 7,170,293,122 | 1.20 % |

| 2014 | 7,255,029,148 | 1.18 % |

| 2015 | 7,339,619,737 | 1.17 % |

| 2016 | 7,423,834,158 | 1.15 % |

| 2017 | 7,507,990,494 | 1.13 % |

| 2018 | 7,591,515,998 | 1.11 % |

| 2019 | 7,674,314,922 | 1.09 % |

| 2020 | 7,756,041,003 | 1.06 % |

| 2021 | 7,851,163,856 | 1.23 % |

| 2022 | 7,948,118,521 | 1.23 % |

| 2023 | 8,046,949,318 | 1.24 % |

The data is given as of 1st of January of an year.

Population projection (2020-2100)

| Year | Population | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 7,797,322,395 | -3.10 % |

| 2025 | 8,187,482,626 | 5.00 % |

| 2030 | 8,553,090,972 | 4.47 % |

| 2035 | 8,894,594,868 | 3.99 % |

| 2040 | 9,212,224,932 | 3.57 % |

| 2045 | 9,506,070,389 | 3.19 % |

| 2050 | 9,773,651,653 | 2.81 % |

| 2055 | 10,012,946,343 | 2.45 % |

| 2060 | 10,224,315,824 | 2.11 % |

| 2065 | 10,411,449,013 | 1.83 % |

| 2070 | 10,577,408,925 | 1.59 % |

| 2075 | 10,723,432,838 | 1.38 % |

| 2080 | 10,850,084,849 | 1.18 % |

| 2085 | 10,958,838,946 | 1.00 % |

| 2090 | 11,051,228,331 | 0.84 % |

| 2095 | 11,127,099,242 | 0.69 % |

| 2100 | 11,185,333,718 | 0.52 % |

The data is given as of 1st of July of an year (medium fertility variant).

Source : United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division

The world’s population today is approximately 7.6 billion. Of the individuals currently living, the average age is approximately 30.1 years. Just over a quarter of the population is under 15 years old. Individuals between 15 and 64 years of age make up 65.9% of the population, and another 7.9% are 65 or older. The World Health Organization suggests that the global average life expectancy is 70.5 years, with men living to 68 and women to 73 years of age. The global fertility rate is around 2.52 children per woman. The human population began to increase significantly at the same time agriculture was discovered, around 10,000 BC. At this time in history, the world’s population was somewhere between 1 and 15 million. By the 4th century BC, between 50 million and 60 million people were alive in the Roman Empire alone. As the world’s population continued to grow, illnesses plagued and wiped out large quantities of people. For example, between the years 500 and 800 AD, the Justinian Plague killed roughly half of the European population. By the time of the 14th century, humans had recovered and numbered around 450 million worldwide. However, the Black Plague took approximately 100 million lives in the year 1400 AD. Two centuries had passed before the population recovered from its losses of the Black Plague. The Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions between the 18th and 20th centuries promoted the next great period of population growth. During this time, hygiene practices improved, vaccines were created, and life expectancies grew. By 1804, the world population had reached 1 billion for the first time. Since then, the population of the world has grown exponentially, hitting the 2 billion mark in 1927, the 3 billion mark in 1960, the 4 billion mark in 1974, the 5 billion mark in 1987, 6 billion in 1999, and finally, the 7 billion mark in 2011. The continent of Asia is home to 60% of the world’s population and hosts the top 2 most populated countries in the world, China and India. Together, these two countries hold 37% of the world’s population. China has a population of over 1.38 billion. In China, there are 12.37 births for every 1,000 people in the population and only 7.16 deaths per 1,000. The life expectancy in the country is 75.35 years. Approximately 73.4% of the population is between 15 and 64 years of age. The fertility rate is 1.55 children per woman. In India, the population numbers a little over 1.33 billion. This number represents 18% of the world’s population. The most populated city in this country is Mumbai with over 12.44 million individuals. Delhi is the second most populated and has a population of 11,034,555. In India, the birth rate is 19.3 for every 1,000 people while there are 7.3 deaths per 1,000. The life expectancy in this country is 68.89 years of age. Around 63.6% of the population is between 15 and 64 years of age. The fertility rate is 2.3 children per woman. The third most populated country in the world is the United States. It has a total population of around 324,707,000. The most populated city in this country is New York City with 8.55 million people. In this country, there are 13.42 births for every 1,000 people and 8.15 deaths per 1,000. The life expectancy is around 79.56 years. Around 66.2% of the population is between 15 and 64 years old. The fertility rate is 1.84 children per woman. The fastest growing populations in the world are located in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. This does not mean these geographic regions have the highest populations, just that they are growing more quickly than other regions around the world. Currently, the global growth percentage is around 1.14% which is down from 2.19% in the 1960’s. According to UN estimates, however, the following countries are growing much faster than that. The top 5 countries with the fastest growing populations are Oman (8.45% growth), Lebanon (5.99%), Kuwait (4.81%), Qatar (4.72%), and South Sudan (4.09%). Interestingly, the fast growing cities are not located in these countries. Instead, the majority of the world’s fastest growing urban populations are mainly found in China and India. These cities are Suzhou, China (5.57%); Guangzhou, China (4.66%); Surat, India (4.4%); Luanda, Angola (4.25%); and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (4.17%). Several organizations have attempted to predict what the world’s future population will look like. The UN Population Division has estimated a population of 9 billion by 2050 and 10 billion by 2100. Many other researchers, however, believe that the population growth pattern might actually be reversed during that time. This is because, in the majority of countries around the world, the fertility rate is actually declining. In some places, it has reached two children per woman, and in other places, it is below that number. The replacement level is considered 2.1, the amount of children needed to sustain the current population size. As previously mentioned, the current global fertility rate is 2.52. If it reaches 2.1, the population will likely remain between 9 and 10 billion. All of these predictions about future population growth lead to one very important question: just how many people can the earth support? While the number of people on the earth continues to grow, the size of the planet and its resources do not. At some point, the population may become too much. Overpopulation of any species results in resource scarcity. Several estimates have suggested various carrying capacities for the earth (dependent on resource consumption), ranging from 7.7 billion to 10 billion. Beyond those numbers, and humans could face shortages in food, water, and energy. How Many People Live In The World?

History Of Population Growth

The Most Populated Countries And Cities

The Fastest Growing Populations

Future Population Growth Projections

How Many People Can Earth Support?

How Many People Live In The World?

| Rank | Continent | Population (millions) |

Most populous country | Most populous city (metropolitan area) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asia | 4,436 | China (1,382,300,000) | Greater Tokyo Area (35,676,000) |

| 2 | Africa | 1,216 | Nigeria (186,987,000) | Lagos (21,000,000) |

| 3 | Europe | 738 | Russia (143,439,000; approx. 110 million in Europe) |

Moscow (19,468,664) |

| 4 | North America[note 2] | 579 | United States (324,118,000) | Mexico City/Metro Area (8,851,080/21,163,226) |

| 5 | South America | 422 | Brazil (209,567,000) | São Paulo City/Metro Area (11,316,149/27,640,577) |

| 6 | Oceania | 39.9 | Australia (24,309,000) | Sydney (4,840,600) |

| 7 | Antarctica | 0.004 in summer (non-permanent, varies) |

N/A | McMurdo Station (1,200) (non-permanent, varies) |

- Home

- World Facts

- How Many People Live In The World?

World population growth from 10,000 BCE to 2021[1]

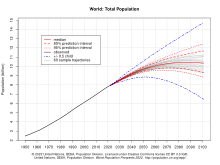

High, medium, and low projections of the future human world population[2]

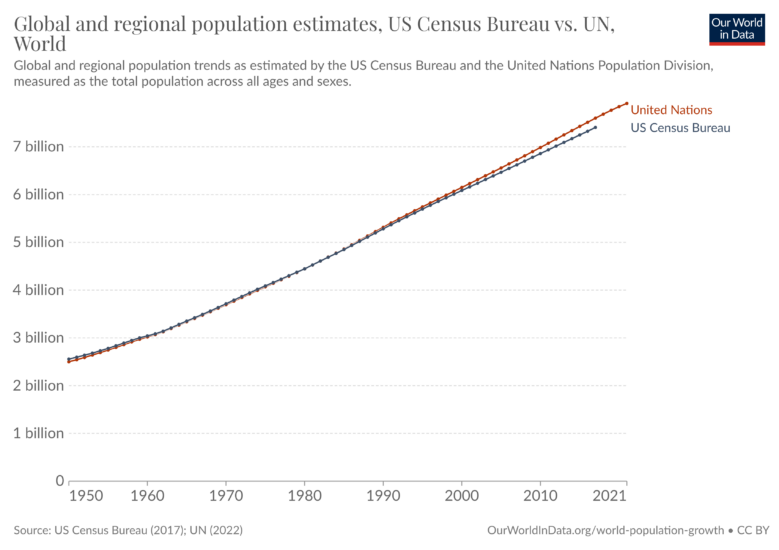

In demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded eight billion in mid-November 2022. It took over 200,000 years of human prehistory and history for the human population to reach one billion and only 219 years more to reach 8 billion.[3]

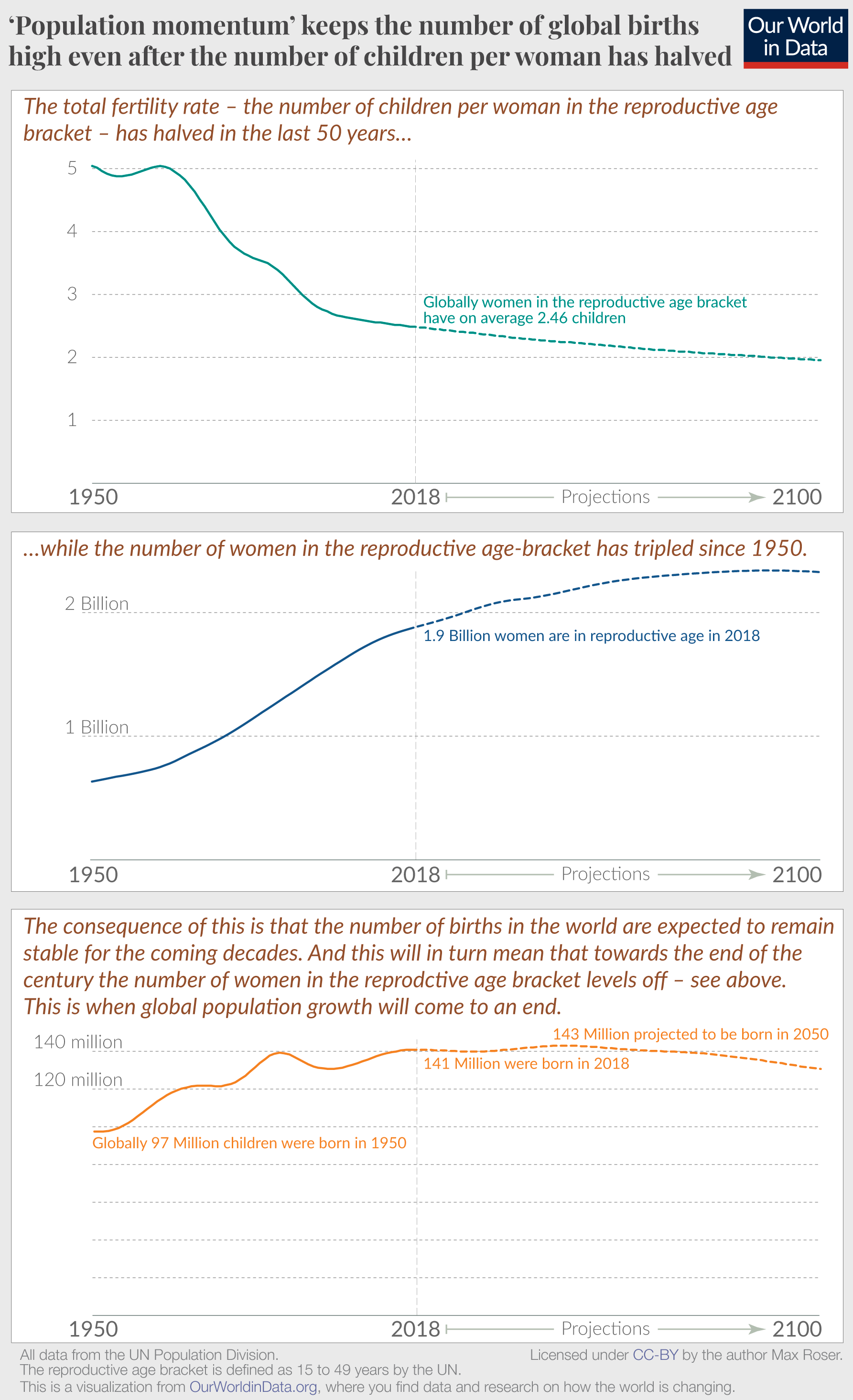

The human population experienced continuous growth following the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the end of the Black Death in 1350, when it was nearly 370,000,000.[4] The highest global population growth rates, with increases of over 1.8% per year, occurred between 1955 and 1975, peaking at 2.1% between 1965 and 1970.[5] The growth rate declined to 1.1% between 2015 and 2020 and is projected to decline further in the 21st century.[6] The global population is still increasing, but there is significant uncertainty about its long-term trajectory due to changing fertility and mortality rates.[7] The UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs projects between 9 and 10 billion people by 2050 and gives an 80% confidence interval of 10–12 billion by the end of the 21st century,[2] with a growth rate by then of zero. Other demographers predict that the human population will begin to decline in the second half of the 21st century.[8]

The total number of births globally is currently (2015–2020) 140 million/year, which is projected to peak during the period 2040–2045 at 141 million/year and then decline slowly to 126 million/year by 2100.[9] The total number of deaths is currently 57 million/year and is projected to grow steadily to 121 million/year by 2100.[10]

The median age of human beings as of 2020 is 31 years.[11]

History

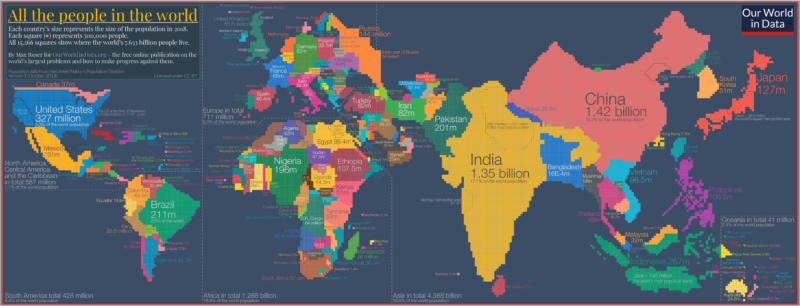

Visual comparison of the world population in past and present

Estimates of world population by their nature are an aspect of modernity, possible only since the Age of Discovery. Early estimates for the population of the world[12] date to the 17th century: William Petty, in 1682, estimated the world population at 320 million (current estimates ranging close to twice this number); by the late 18th century, estimates ranged close to one billion (consistent with current estimates).[13] More refined estimates, broken down by continents, were published in the first half of the 19th century, at 600 million to 1 billion in the early 1800s and 800 million to 1 billion in the 1840s.[14]

It is difficult for estimates to be better than rough approximations, as even current population estimates are fraught with uncertainties from 3% to 5%.[15]

Ancient and post-classical history

Estimates of the population of the world at the time agriculture emerged in around 10,000 BC have ranged between 1 million and 15 million.[16][17] Even earlier, genetic evidence suggests humans may have gone through a population bottleneck of between 1,000 and 10,000 people about 70,000 BC, according to the now largely discredited Toba catastrophe theory. By contrast, it is estimated that around 50–60 million people lived in the combined eastern and western Roman Empire in the 4th century AD.[18]

The Plague of Justinian caused Europe’s population to drop by around 50% between the 6th and 8th centuries AD.[19] The population of Europe was more than 70 million in 1340.[20] From 1340 to 1400, the world’s population fell from an estimated 443 million to 350–375 million,[21] with the Indian subcontinent suffering the most tremendous loss and Europe suffering the Black Death pandemic;[22] it took 200 years for European population figures to recover.[23] The population of China decreased from 123 million in 1200 to 65 million in 1393,[24] presumably from a combination of Mongol invasions, famine, and plague.[25]

Starting in AD 2, the Han dynasty of ancient China kept consistent family registers to properly assess the poll taxes and labor service duties of each household.[26] In that year, the population of Western Han was recorded as 57,671,400 individuals in 12,366,470 households, decreasing to 47,566,772 individuals in 9,348,227 households by AD 146, towards the end of the Han dynasty.[26] From 200 to 400, the world population fell from an estimated 257 million to 206 million, with China suffering the greatest loss.[22] At the founding of the Ming dynasty in 1368, China’s population was reported to be close to 60 million; toward the end of the dynasty in 1644, it may have approached 150 million.[27] England’s population reached an estimated 5.6 million in 1650, up from an estimated 2.6 million in 1500.[28] New crops that were brought to Asia and Europe from the Americas by Portuguese and Spanish colonists in the 16th century are believed to have contributed to population growth.[29][30][31] Since their introduction to Africa by Portuguese traders in the 16th century,[32] maize and cassava have similarly replaced traditional African crops as the most important staple food crops grown on the continent.[33]

The pre-Columbian population of the Americas is uncertain; historian David Henige called it «the most unanswerable question in the world.»[34] By the end of the 20th century, scholarly consensus favored an estimate of roughly 55 million people, but numbers from various sources have ranged from 10 million to 100 million.[35] Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced local epidemics of extraordinary virulence.[36] According to the most extreme scholarly claims, as many as 90% of the Native American population of the New World died of Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza.[37] Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no such immunity.[38]

Modern history

Map showing urban areas with at least one million inhabitants in 2006. Only 3% of the world’s population lived in urban areas in 1800; this proportion had risen to 47% by 2000, and reached 50.5% by 2010.[39] By 2050, the proportion may reach 70%.[40]

During the European Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions, the life expectancy of children increased dramatically.[41] The percentage of the children born in London who died before the age of five decreased from 74.5% in 1730–1749 to 31.8% in 1810–1829.[42][43] Between 1700 and 1900, Europe’s population increased from about 100 million to over 400 million.[44] Altogether, the areas populated by people of European descent comprised 36% of the world’s population in 1900.[45]

Population growth in the Western world became more rapid after the introduction of vaccination and other improvements in medicine and sanitation.[46] Improved material conditions led to the population of Britain increasing from 10 million to 40 million in the 19th century.[47] The population of the United Kingdom reached 60 million in 2006.[48] The United States saw its population grow from around 5.3 million in 1800 to 106 million in 1920, exceeding 307 million in 2010.[49]

The first half of the 20th century in Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union was marked by a succession of major wars, famines and other disasters which caused large-scale population losses (approximately 60 million excess deaths).[50][51] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia’s population declined significantly – from 150 million in 1991 to 143 million in 2012[52] – but by 2013 this decline appeared to have halted.[53]

Many countries in the developing world have experienced extremely rapid population growth since the early 20th century, due to economic development and improvements in public health. China’s population rose from approximately 430 million in 1850 to 580 million in 1953,[54] and now stands at over 1.3 billion. The population of the Indian subcontinent, which was about 125 million in 1750, increased to 389 million in 1941;[55] today, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are collectively home to about 1.63 billion people.[56] Java, an island in Indonesia, had about 5 million inhabitants in 1815; it had a population of over 139 million in 2020.[57] In just one hundred years, the population of Brazil decupled (x10), from about 17 million in 1900, or about 1% of the world population in that year, to about 176 million in 2000, or almost 3% of the global population in the very early 21st century. Mexico’s population grew from 13.6 million in 1900 to about 112 million in 2010.[58][59] Between the 1920s and 2000s, Kenya’s population grew from 2.9 million to 37 million.[60]

Milestones by the billions

| Population | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1804 | 1930 | 1960 | 1974 | 1987 | 1999 | 2011 | 2022 | 2037 | 2057 |

| Years elapsed | 200,000+ | 126 | 30 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 20 |

The UN estimated that the world population reached one billion for the first time in 1804. It was another 123 years before it reached two billion in 1927, but it took only 33 years to reach three billion in 1960.[62] Thereafter, it took 14 years for the global population to reach four billion in 1974, 13 years to reach five billion in 1987, 12 years to reach six billion in 1999 and, according to the United States Census Bureau, 13 years to reach seven billion in March 2012.[63] The United Nations, however, estimated that the world population reached seven billion in October 2011.[64][65][66]

According to the UN, the global population reached eight billion in November 2022,[67] but because the growth rate is slowing, it will take another 15 years to reach around 9 billion by 2037 and 20 years to reach 10 billion by 2057.[68] Alternative scenarios for 2050 range from a low of 7.4 billion to a high of more than 10.6 billion.[69] Projected figures vary depending on underlying statistical assumptions and the variables used in projection calculations, especially the fertility and mortality variables. Long-range predictions to 2150 range from a population decline to 3.2 billion in the «low scenario», to «high scenarios» of 24.8 billion.[69] One extreme scenario predicted a massive increase to 256 billion by 2150, assuming the global fertility rate remained at its 1995 level of 3.04 children per woman; however, by 2010 the global fertility rate had declined to 2.52.[70][71]

There is no estimation for the exact day or month the world’s population surpassed one or two billion. The points at which it reached three and four billion were not officially noted, but the International Database of the United States Census Bureau placed them in July 1959 and April 1974 respectively. The United Nations did determine, and commemorate, the «Day of 5 Billion» on 11 July 1987, and the «Day of 6 Billion» on 12 October 1999. The Population Division of the United Nations declared the «Day of Seven Billion» to be 31 October 2011.[72] The United Nations marked the birth of the eight billionth person on 15 November 2022.[73][67]

Global demographics

-

>80

-

77.5–80

-

75–77.5

-

72.5–75

-

70–72.5

-

67.5–70

-

65–67.5

-

60–65

-

55–60

-

50–55

2015 map showing average life expectancy by country in years. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated the average global life expectancy as 71.4 years.[74]

As of 2012, the global sex ratio is approximately 1.01 males to 1 female.[75] Approximately 26.3% of the global population is aged under 15, while 65.9% is aged 15–64 and 7.9% is aged 65 or over.[75] The median age of the world’s population is estimated to be 31 years in 2020,[11] and is expected to rise to 37.9 years by 2050.[76]

According to the World Health Organization, the global average life expectancy is 73.3 years as of 2020, with women living an average of 75.9 years and men approximately 70.8 years.[77] In 2010, the global fertility rate was estimated at 2.44 children per woman.[78] In June 2012, British researchers calculated the total weight of Earth’s human population as approximately 287 million tonnes (630 billion pounds), with the average person weighing around 62 kilograms (137 lb).[79]

The IMF estimated nominal 2021 gross world product at US$94.94 trillion, giving an annual global per capita figure of around US$12,290.[80] Around 9.3% of the world population live in extreme poverty, subsisting on less than US$1.9 per day;[81] around 8.9% are malnourished.[82] 87% of the world’s over-15s are considered literate.[83] As of April 2022, there were about 5 billion global Internet users, constituting 63% of the world population.[84]

The Han Chinese are the world’s largest single ethnic group, constituting over 19% of the global population in 2011.[85] The world’s most-spoken languages are English (1.132B), Mandarin Chinese (1.117B), Hindi (615M), Spanish (534M) and French (280M). More than three billion people speak an Indo-European language, which is the largest language family by number of speakers. Standard Arabic is a language with no native speakers, but the total number of speakers is estimated at 274 million people.[86]

The largest religious categories in the world as of 2020 are estimated as follows: Christianity (31%), Islam (25%), Unaffiliated (16%) and Hinduism (15%).[87]

Population by region

Six of the Earth’s seven continents are permanently inhabited on a large scale.

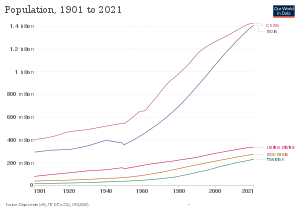

Asia is the most populous continent, with its 4.64 billion inhabitants accounting for 60% of the world population. The world’s two most populated countries, China and India, together constitute about 36% of the world’s population.

Africa is the second most populated continent, with around 1.34 billion people, or 17% of the world’s population.

Europe’s 747 million people make up 10% of the world’s population as of 2020,

while the Latin American and Caribbean regions are home to around 653 million (8%). Northern America, primarily consisting of the United States and Canada, has a population of around 368 million (5%),

and Oceania, the least populated region, has about 42 million inhabitants (0.5%).[88] Antarctica only has a very small, fluctuating population of about 1200 people based mainly in polar science stations.[89]

| Region | Density (inhabitants/km2) |

Population (millions) |

Most populous country | Most populous city (metropolitan area) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 104.1 | 4,641 | 1,411,778,000 – |

13,515,000 – (37,400,000 – |

| Africa | 44.4 | 1,340 | 0,211,401,000 – |

09,500,000 – (20,076,000 – |

| Europe | 73.4 | 747 | 0,146,171,000 – |

13,200,000 – (20,004,000 – |

| Latin America | 24.1 | 653 | 0,214,103,000 – |

12,252,000 – (21,650,000 – |

| Northern America[note 2] | 14.9 | 368 | 0,332,909,000 – |

08,804,000 – (23,582,649 – |

| Oceania | 5 | 42 | 0,025,917,000 – |

05,367,000 – |

| Antarctica | ~0 | 0.004[89] | N/A[note 3] | 00,001,258 – |

Largest populations by country

Cartogram showing the distribution of the world population, each square represents half a million people.

A map of world population in 2019

1901 to 2021 population graph of the five countries with the highest current populations

10 most populous countries

| Rank | Country / Dependency | Population | Percentage of the world |

Date | Source (official or from the United Nations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,412,600,000 | 17.6% | 31 Dec 2021 | National annual estimate[91] | |

| 2 | 1,373,761,000 | 17.1% | 1 Mar 2022 | Annual national estimate[92] | |

| 3 | 333,887,244 | 4.16% | 12 Apr 2023 | National population clock[93] | |

| 4 | 275,773,800 | 3.44% | 1 Jul 2022 | National annual estimate[94] | |

| 5 | 229,488,994 | 2.86% | 1 Jul 2022 | UN projection[95] | |

| 6 | 216,746,934 | 2.70% | 1 Jul 2022 | UN projection[95] | |

| 7 | 216,007,989 | 2.69% | 12 Apr 2023 | National population clock[96] | |

| 8 | 168,220,000 | 2.10% | 1 Jul 2020 | Annual Population Estimate[97] | |

| 9 | 147,190,000 | 1.83% | 1 Oct 2021 | 2021 preliminary census results[98] | |

| 10 | 128,271,248 | 1.60% | 31 Mar 2022 | National quarterly estimate[99] |

Approximately 4.5 billion people live in these ten countries, representing around 56% of the world’s population as of July 2022.

The UN estimates that by 2030 India will have overtaken China in having the largest population.

| # | Most populous countries | 2000 | 2015 | 2030[A] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,270 | 1,376 | 1,416 | ||

| 2 | 1,053 | 1,311 | 1,528 | ||

| 3 | 283 | 322 | 356 | ||

| 4 | 212 | 258 | 295 | ||

| 5 | 136 | 208 | 245 | ||

| 6 | 176 | 206 | 228 | ||

| 7 | 123 | 182 | 263 | ||

| 8 | 131 | 161 | 186 | ||

| 9 | 146 | 146 | 149 | ||

| 10 | 103 | 127 | 148 | ||

| World total | 6,127 | 7,349 | 8,501 | ||

Notes:

|

Most densely populated countries

The tables below list the world’s most densely populated countries, both in absolute terms and in comparison to their total populations, as of November 2022. All areas and populations are from The World Factbook, unless otherwise noted.

Population density (people per km2) map of the world in 2020. Red areas denote regions of highest population density

| Rank | Country | Population | Area (km2) |

Density (pop/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,921,231 | 719 | 8,235 | |

| 2 | 165,650,475 | 148,460 | 1,116 | |

| 3 |

|

5,223,000 | 6,025 | 867 |

| 4 | 23,580,712 | 35,980 | 655 | |

| 5 | 51,844,834 | 99,720 | 520 | |

| 6 | 5,296,814 | 10,400 | 509 | |

| 7 | 13,173,730 | 26,338 | 500 | |

| 8 | 12,696,478 | 27,830 | 456 | |

| 9 | 1,389,637,446 | 3,287,263 | 423 | |

| 10 | 17,400,824 | 41,543 | 419 |

| Rank | Country | Population | Area (km2) |

Density (pop/km2) |

Population trend[citation needed] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,389,637,446 | 3,287,263 | 423 | Growing | |

| 2 | 242,923,845 | 796,095 | 305 | Rapidly growing | |

| 3 | 165,650,475 | 148,460 | 1,116 | Growing | |

| 4 | 124,214,766 | 377,915 | 329 | Declining[103] | |

| 5 | 114,597,229 | 300,000 | 382 | Growing | |