Morphology is the study of words, word formation, and the relationship between words. In Morphology, we look at morphemes — the smallest lexical items of meaning. Studying morphemes helps us to understand the meaning, structure, and etymology (history) of words.

Morphemes: meaning

The word morphemes from the Greek morphḗ, meaning ‘shape, form‘. Morphemes are the smallest lexical items of meaning or grammatical function that a word can be broken down to. Morphemes are usually, but not always, words.

Look at the following examples of morphemes:

These words cannot be made shorter than they already are or they would stop being words or lose their meaning.

For example, ‘house’ cannot be split into ho- and -us’ as they are both meaningless.

However, not all morphemes are words.

For example, ‘s’ is not a word, but it is a morpheme; ‘s’ shows plurality and means ‘more than one’.

The word ‘books’ is made up of two morphemes: book + s.

Morphemes play a fundamental role in the structure and meaning of language, and understanding them can help us to better understand the words we use and the rules that govern their use.

How to identify a morpheme

You can identify morphemes by seeing if the word or letters in question meet the following criteria:

-

Morphemes must have meaning. E.g. the word ‘cat’ represents and small furry animal. The suffix ‘-s’ you might find at the end of the word ‘cat’ represents plurality.

- Morphemes cannot be divided into smaller parts without losing or changing their meaning. E.g. dividing the word ‘cat’ into ‘ca’ leaves us with a meaningless set of letters. The word ‘at’ is a morpheme in its own right.

Types of morphemes

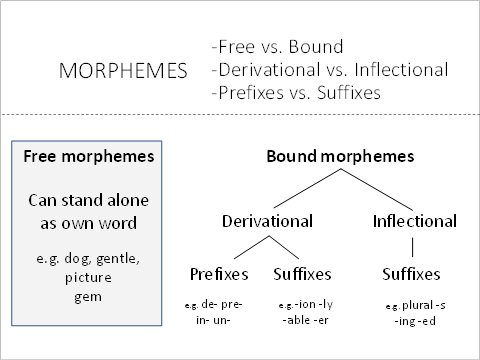

There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes

Free morphemes can stand alone and don’t need to be attached to any other morphemes to get their meaning. Most words are free morphemes, such as the above-mentioned words house, book, bed, light, world, people, and so on.

Bound morphemes

Bound morphemes, however, cannot stand alone. The most common example of bound morphemes are suffixes, such as —s, —er, —ing, and -est.

Let’s look at some examples of free and bound morphemes:

-

Tall

-

Tree

-

-er

-

-s

‘Tall’ and ‘Tree’ are free morphemes.

We understand what ‘tall’ and ‘tree’ mean; they don’t require extra add-ons. We can use them to create a simple sentence like ‘That tree is tall.’

On the other hand, ‘-er’ and ‘-s’ are bound morphemes. You won’t see them on their own because they are suffixes that add meaning to the words they are attached to.

So if we add ‘-er’ to ‘tall’ we get the comparative form ‘taller’, while ‘tree’ plus ‘-s’ becomes plural: ‘trees’.

Morphemes: structure

Morphemes are made up of two separate classes.

-

Bases (or roots)

-

Affixes

A morpheme’s base is the main root that gives the word its meaning.

On the other hand, an affix is a morpheme we can add that changes or modifies the meaning of the base.

‘Kind’ is the free base morpheme in the word ‘kindly’. (kind + -ly)

‘-less’ is a bound morpheme in the word ‘careless’. (Care + —less)

Morphemes: affixes

Affixes are bound morphemes that occur before or after a base word. They are made up of suffixes and prefixes.

Suffixes are attached to the end of the base or root word. Some of the most common suffixes include —er, -or, -ly, -ism, and -less.

Taller

Thinner

Comfortably

Absurdism

Ageism

Aimless

Fearless

Prefixes come before the base word. Typical prefixes include ante-, pre-, un-, and dis-.

Antedate

Prehistoric

Unkind

Disappear

Derivational affixes

Derivational affixes are used to change the meaning of a word by building on its base. For instance, by adding the prefix ‘un-‘ to the word ‘kind‘, we got a new word with a whole new meaning. In fact, ‘unkind‘ has the exact opposite meaning of ‘kind’!

Another example is adding the suffix ‘-or’ to the word ‘act’ to create ‘actor’. The word ‘act’ is a verb, whereas ‘actor’ is a noun.

Inflectional affixes

Inflectional affixes only modify the meaning of words instead of changing them. This means they modify the words by making them plural, comparative or superlative, or by changing the verb tense.

books — books

short — shorter

quick — quickest

walk — walked

climb — climbing

There are many derivational affixes in English, but only eight inflectional affixes and these are all suffixes.

|

Word class |

Modification reason |

Suffixes |

| To modify nouns | Plural & possessive forms | -s (or -es), -‘s (or s’) |

| To modify adjectives |

Comparative & superlative forms |

-er, -est |

| To modify verbs |

3rd person singular, past tense, present & past participles |

-s, -ed, -ing, -en |

All prefixes in English are derivational. However, suffixes may be either derivational or inflectional.

Morphemes: categories

The free morphemes we looked at earlier (such as tree, book, and tall) fall into two categories:

- Lexical morphemes

- Functional morphemes

Reminder: Most words are free morphemes because they have meaning on their own, such as house, book, bed, light, world, people etc.

Lexical morphemes

Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, text or conversation. These words can be nouns, adjectives and verbs. Examples of lexical morphemes include:

- house

- book

- tree

- panther

- loud

- quiet

- big

- orange

- blue

- open

- run

- talk

Because we can add new lexical morphemes to a language (new words get added to the dictionary each year!), they are considered an ‘open’ class of words.

Functional morphemes

Functional (or grammatical) morphemes are mostly words that have a functional purpose, such as linking or referencing lexical words. Functional morphemes include prepositions, conjunctions, articles and pronouns. Examples of functional morphemes include:

- and

- but

- when

- because

- on

- near

- above

- in

- the

- that

- it

- them.

We can rarely add new functional morphemes to the language, so we call this a ‘closed’ class of words.

Allomorphs

Allomorphs are a variant of morphemes. An allomorph is a unit of meaning that can change its sound and spelling but doesn’t change its meaning and function.

In English, the indefinite article morpheme has two allomorphs. Its two forms are ‘a’ and ‘an’. If the indefinite article precedes a word beginning with a constant sound it is ‘a’, and if it precedes a word beginning with a vowel sound, it is ‘an’.

Past Tense allomorphs

In English, regular verbs use the past tense morpheme -ed; this shows us that the verb happened in the past. The pronunciation of this morpheme changes its sound according to the last consonant of the verb but always keeps its past tense function. This is an example of an allomorph.

Consider regular verbs ending in t or d, like ‘rent’ or ‘add’.

Now look at their past forms: ‘rented‘ and ‘added‘. Try pronouncing them. Notice how the —ed at the end changes to an /id/ sound (e.g. rent /ɪd/, add /ɪd/).

Now consider the past simple forms of want, rest, print, and plant. When we pronounce them, we get: wanted (want /ɪd/), rested (rest /ɪd/), printed (print /ɪd/), planted (plant /ɪd/).

Now look at other regular verbs ending in the following ‘voiceless’ phonemes: /p/, /k/, /s/, /h/, /ch/, /sh/, /f/, /x/. Try pronouncing the past form and notice how the allomorph ‘-ed’ at the end changes to a /t/ sound. For example, dropped, pressed, laughed, and washed.

Plural allomorphs

Typically we add ‘s’ or ‘es’ to most nouns in English when we want to create the plural form. The plural forms ‘s’ or ‘es’ remain the same and have the same function, but their sound changes depending on the form of the noun. The plural morpheme has three allomorphs: [s], [z], and [ɨz].

When a noun ends in a voiceless consonant (i.e. ch, f, k, p, s, sh, t, th), the plural allomorph is /s/.

Book becomes books (pronounced book/s/)

When a noun ends in a voiced phoneme (i.e. b, l, r, j, d, v, m, n, g, w, z, a, e, i, o, u) the plural form remains ‘s’ or ‘es’ but the allomorph sound changes to /z/.

Key becomes keys (pronounced key/z/)

Bee becomes bees (pronounced bee/z/)

When a noun ends in a sibilant (i.e. s, ss, z), the sound of the allomorph sound becomes /iz/.

Bus becomes buses (bus/iz/)

house becomes houses (hous/iz/)

A sibilant is a phonetic sound that makes a hissing sound, e.g. ‘s’ or ‘z’.

Zero (bound) morphemes

The zero bound morpheme has no phonetic form and is also referred to as an invisible affix, null morpheme, or ghost morpheme.

A zero morpheme is when a word changes its meaning but does not change its form.

In English, certain nouns and verbs do not change their appearance even when they change number or tense.

Sheep, deer, and fish, keep the same form whether they are used as singular or plural.

Some verbs like hit, cut, and cost remains the same in their present and past forms.

Morphemes — Key takeaways

- Morphemes are the smallest lexical unit of meaning. Most words are free morphemes, and most affixes are bound morphemes.

- There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

- Free morphemes can stand alone, whereas bound morphemes must be attached to another morpheme to get their meaning.

- Morphemes are made up of two separate classes called bases (or roots) and affixes.

- Free morphemes fall into two categories; lexical and functional. Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, and functional morphemes have a grammatical purpose.

Recommended textbook solutions

The Language of Composition: Reading, Writing, Rhetoric

2nd Edition•ISBN: 9780312676506Lawrence Scanlon, Renee H. Shea, Robin Dissin Aufses

661 solutions

Literature and Composition: Reading, Writing,Thinking

1st Edition•ISBN: 9780312388065Carol Jago, Lawrence Scanlon, Renee H. Shea, Robin Dissin Aufses

1,697 solutions

Technical Writing for Success

3rd Edition•ISBN: 9780538450485 (3 more)Darlene Smith-Worthington, Sue Jefferson

468 solutions

Technical Writing for Success

3rd Edition•ISBN: 9781111445072Darlene Smith-Worthington, Sue Jefferson

468 solutions

Morphology is the study of words and their parts. Morphemes, like prefixes, suffixes and base words, are defined as the smallest meaningful units of meaning. Morphemes are important for phonics in both reading and spelling, as well as in vocabulary and comprehension.

Why use morphology

Teaching morphemes unlocks the structures and meanings within words. It is very useful to have a strong awareness of prefixes, suffixes and base words. These are often spelt the same across different words, even when the sound changes, and often have a consistent purpose and/or meaning.

Types of morphemes

Free vs. bound

Morphemes can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes).

A free morpheme can stand alone as its own word

- gentle

- father

- licence

- picture

- gem

A bound morpheme only occurs as part of a word

- -s as in cat+s

- -ed as in crumb+ed

- un- as in un+happy

- mis- as in mis-fortune

- -er as in teach+er

In the example above: un+system+atic+al+ly, there is a root word (system) and bound morphemes that attach to the root (un-, -atic, -al, -ly)

system = root un-, -atic, -al, -ly = bound morphemes

If two free morphemes are joined together they create a compound word. These words are a great way to introduce morphology (the study of word parts) into the classroom.

For more details, see:

Compound words

Inflectional vs. derivational

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

Inflectional morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but does not create a new word.

For example, the word <skip> has many forms: skip (base form), skipping (present progressive), skipped (past tense).

The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word skip, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few suffixes added. So if you looked up <skip> in the dictionary, then only the base word <skip> would get its own entry into the dictionary. Skipping and skipped are listed under skip, as they are inflections of the base word. Skipping and skipped do not get their own dictionary entry.

Skip

verb, skipped, skipping.

- to move in a light, springy manner by bounding forward with alternate hops on each foot. to pass from one point, thing, subject, etc.,

- to another, disregarding or omitting what intervenes: He skipped through the book quickly.

- to go away hastily and secretly; flee without notice.

From

Dictionary.com — skip

Another example is <run>: run (base form), running (present progressive), ran (past tense). In this example the past tense marker changes the vowel of the word: run (rhymes with fun), to ran (rhymes with can). However, the inflectional morphemes -ing and past tense morpheme are added to the base word <run>, and are listed in the same dictionary entry.

Run

verb, ran, run, running.

- to go quickly by moving the legs more rapidly than at a walk and in such a manner that for an instant in each step all or both feet are off the ground.

- to move with haste; act quickly: Run upstairs and get the iodine.

- to depart quickly; take to flight; flee or escape: to run from danger.

From

Dictionary.com — run

Derivational morphemes are different to inflectional morphemes, as they do derive/create a new word, which gets its own entry in the dictionary. Derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

For example, we can create new words from <act> by adding derivational prefixes (e.g. re- en-) and suffixes (e.g. -or).

Thus out of <act> we can get re+act = react en+act = enact act+or = actor.

Whenever a derivational morpheme is added, a new word (and dictionary entry) is derived/created.

For the <act> example, the following dictionary entries can be found:

Act

noun

- anything done, being done, or to be done; deed; performance: a heroic act.

- the process of doing: caught in the act.

- a formal decision, law, or the like, by a legislature, ruler, court, or other authority; decree or edict; statute; judgement, resolve, or award: an act of Parliament.

From

Dictionary.com — act

React

verb

- to act in response to an agent or influence: How did the audience react to the speech?

- to act reciprocally upon each other, as two things.

- to act in a reverse direction or manner, especially so as to return to a prior condition.

From

Dictionary.com — react

Enact

verb

- to make into an act or statute: Parliament has enacted a new tax law.

- to represent on or as on the stage; act the part of: to enact Hamlet.

From

Dictionary.com — enact

Actor

noun

- a person who acts in stage plays, motion pictures, television broadcasts, etc.

- a person who does something; participant.

From

Dictionary.com — actor

Teachers should highlight and encourage students to analyse both Inflectional and Derivational morphemes when focussing on phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For more information, see:

Prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases

Many morphemes are very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. Morphemes can be divided into prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes (see example below)

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon Morphemes (like re-, un-, and -ness);

- Latin Morphemes (like non-, ex-, -ion, and -ify); and

- Greek Morphemes (like micro, photo, graph).

It is useful to highlight how words can be broken down into morphemes (and which each of these mean) and how they can be built up again).

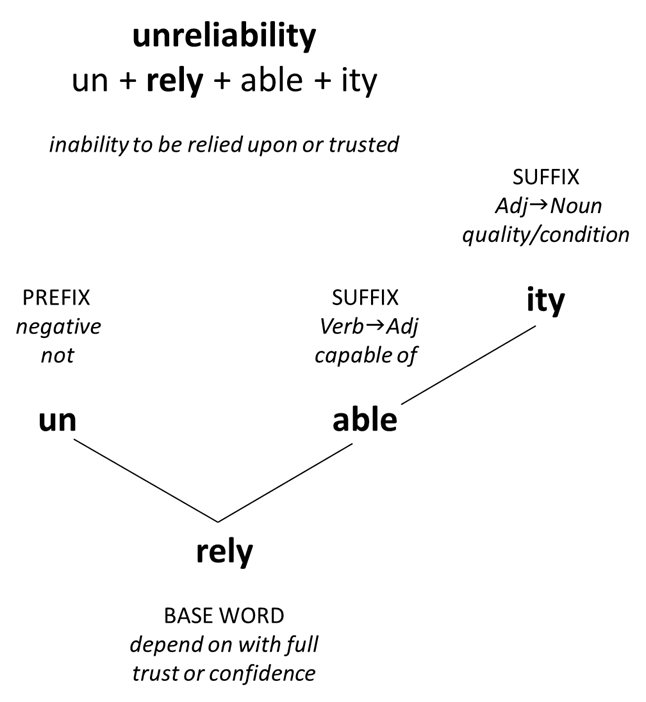

For example, the word <unreliability> may be unfamiliar to students when they first encounter it.

If <unreliability> is broken into its morphemes, students can deduce or infer the meaning.

So it is helpful for both reading and spelling to provide opportunities to analyse words, and become familiar with common morphemes, including their meaning and function.

Compound words

Compound words (or compounds) are created by joining free morphemes together. Remember that a free morpheme is a morpheme that can stand along as its own word (unlike bound morphemes — e.g. -ly, -ed, re-, pre-). Compounds are a fun and accessible way to introduce the idea that words can have multiple parts (morphemes). Teachers can highlight that these compound words are made up of two separate words joined together to make a new word. For example dog + house = doghouse

Examples

- lifetime

- basketball

- cannot

- fireworks

- inside

- upside

- footpath

- sunflower

- moonlight

- schoolhouse

- railroad

- skateboard

- meantime

- bypass

- sometimes

- airport

- butterflies

- grasshopper

- fireflies

- footprint

- something

- homemade

- backbone

- passport

- upstream

- spearmint

- earthquake

- backward

- football

- scapegoat

- eyeball

- afternoon

- sandstone

- meanwhile

- limestone

- keyboard

- seashore

- touchdown

- alongside

- subway

- toothpaste

- silversmith

- nearby

- raincheck

- blacksmith

- headquarters

- lukewarm

- underground

- horseback

- toothpick

- honeymoon

- bootstrap

- township

- dishwasher

- household

- weekend

- popcorn

- riverbank

- pickup

- bookcase

- babysitter

- saucepan

- bluefish

- hamburger

- honeydew

- thunderstorm

- spokesperson

- widespread

- hometown

- commonplace

- supermarket

Example activities of highlighting morphemes for phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension

There are numerous ways to highlight morphemes for the purpose of phonics, vocabulary and comprehension activities and lessons.

Highlighting the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules, as well as discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, and demonstrating how words are linked together. Highlighting and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies.

Examples of how to embed morphological awareness into literacy activities can include:

- Sorting words by base/root words (word families), or by prefixes or suffixes

- Word Detective — Students break longer words down into their prefixes, suffixes, and base words

- e.g. Find the morphemes in multi-morphemic words like: dissatisfied unstoppable ridiculously hydrophobic metamorphosis oxygenate fortifications

- Word Builder — students are given base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words they can build, and what meaning they might have:

- Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness -ment - Etymology investigation — students are given multi-morphemic words from texts they have been reading and are asked to research the origins (etymology) of the word. Teachers could use words like progressive, circumspect, revocation, and students could find out the morphemes within each word, their etymology, meanings, and use.

VLearn

independent learning platform on word knowledge and vocabulary building strategies

Free Morphemes and Bound Morphemes

Morphemes that can stand alone to function as words are called free morphemes. They comprise simple words (i.e. words made up of one free morpheme) and compound words (i.e. words made up of two free morphemes).

Examples:

Simple words: the, run, on, well

Compound words: keyboard, greenhouse, bloodshed, smartphone

Morphemes that can only be attached to another part of a word (cannot stand alone) are called bound morphemes.

Examples:

pre-, dis-, in-, un-, -ful, -able, -ment, -ly, -ise

test,

dis

content,

in

tolerable,

re

ceive

Complex words are words that are made up of both free morpheme(s) and bound morpheme(s), or two or more bound morphemes.

Roll your mouse over the words below to see how many morphemes are there and whether they are free morphemes or bound morphemes.

| againstagainst | imperativeimperative | realize realize | submitsubmit |

| assignmentassign+ment | FacebookFace+book | uncommonun+common | misinterpretmis+interpret |

| disqualifieddis+qualify+ed | encountereden+counter+ed | geographygeo+graph+y | irresistibleir+resist+ible |

Privacy Policy | Disclaimer

Copyright © 2014. All Rights Reserved. Faculty of Education. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

According

to the number of morphemes words are classified into monomorphic

and polymorphic.

Monomorphic

or

root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g., small,

dog, make, give, etc.

All polymorphic

words according to the number of root-morphemes are classified into

two subgroups: monoradical or root words and polyradical words, i.e.,

words which consist of two or more roots.

Monoradical

words fall into two subtypes: 1) radical-suffixal

words, i.e., words that consist of one root-morpheme and one or more

suffixal morphemes, e.g., acceptable,

acceptability, blackish; 2)

radical-prefixal

words, i.e., words that consist of one root-morpheme and a prefixal

morpheme, e.g. outdo,

rearrange, unbutton; and

3) prefixo-radical-suffixal,

i.e., words which consist of one root, a prefixal and suffixal

morphemes, e.g., disagreeable,

misinterpretation.

Polyradical

words

fall into two subtypes: 1) polyradical words which consist of two or

more roots with no affixational morphemes, e.g., book-stand,

eye-ball,

lamp-shade; and

2) words which contain at least two roots and one or more

affixational morphemes, e.g., safety-pin,

wedding-pie, class-

consciousness,

light-mindedness, pen-holder.

-

Derivational and morphemic levels of analysis

The

morphemic

analysis

of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their

types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the

morphemes comprising the word.

Morphemes

are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in

various types of words and particular groups within the same types.

The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of

words into different types and enables one to understand how new

words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the

interrelations between different types and classes of words are known

as derivative

or word- formation relations.

The

analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation

between different types and the structural patterns words are built

on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.The stem is

defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout

its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask (

), asks,

asked, asking is ask-; thestem

of the word singer (

), singer’s,

singers, singers’ is singer-.

-

Morphemic

word classification

-

Word

formation in Modern English

Word

formation is a branch of science of the language which studies the

patterns on which a language forms new lexical items (new unities,

new words). Word formation is a process of forming words by

combining root

& affixal morphemes.

Different

types of word formation:

—

COMPOUNDING is joining together 2 or more stems.

Types: 1) without

a connecting element (headache, heartbreak); 2) with a vowel or

consonant as a linking element (speedometer, craftsman); 3) with a

preposition or conjunction as a linking element down-and-out

(опустошенный)

son-in-law.

— PREFIXATION Prefixes are such particles that can be

prefixed to full words. But are themselves not with independent

existence.

— SUFFIXATION A suffix is a derivative final element

which is or was productive in forming new words. It has semantic

value, but doesn’t occur as an independent speech use.

—

CONVERSION (zero derivation) A certain stem is used for the formation

of a categorically different word without a derivative element being

added.(Bag – to bag)

— BACK DERIVATION is deraving a new word,

which is morphologically simpler from a more complex word. ( A

babysitter – to babysit Television – to

televise)

— PHONETIC SYMBOLISM is using characteristic speech

sounds for name giving. Very often we imitate by the speech sounds

what we hear: (tinkle, splash, t).

— CLIPPING Consists in the

reduction of a word to one of its parts. (

Mathematics – maths)

— BLENDING is blending part of two words to

form one word ( Smoke + fog = smog)

-

Morphological

structure of a word. Productive and non-productive ways of word

formation.

Morphology

is the study of the structure and form of words in language or a

language, including inflection, derivation, and the formation of

compounds. At the basic level, words are made of «morphemes.»

These are the smallest units of meaning: roots and affixes (prefixes

and suffixes). Native speakers recognize the morphemes as

grammatically significant or meaningful. For example, «schoolyard»

is made of «school» + «yard», «makes»

is made of «make» + a grammatical suffix «-s»,

and «unhappiness» is made of «happy» with a

prefix «un-» and a suffix «-ness».

Inflection

occurs when a word has different forms but essentially the same

meaning, and there is only a grammatical difference between them: for

example, «make» and «makes». The «-s»

is an inflectional morpheme.

In

contrast, derivation makes a word with a clearly different meaning:

such as «unhappy» or «happiness», both from

«happy». The «un-» and «-ness» are

derivational morphemes. Normally a dictionary would list derived

words, but there is no need to list «makes» in a dictionary

as well as «make.»

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material available in

the word-stock according to certain structural and semantic patterns

specific for the given language. There are different ways of

word-formation in Modern English. Some of them are highly-productive.

They are: affixation, conversion, substantivation, compounding,

shortening, formation of phrasal verbs. Others are semi-productive

(back-formation, blending, reduplication, lexicalization of the

plural of nouns, sound imitation) and non-productive ways of

word-building (sound interchange, change of stress).

Non-productive

ways of word-building Sound interchange (gradation) is the process in

which word belonging to different parts of speech may be

differentiated due to the sound interchange in the root, eg food (n)

:: feed (v), gold (n) :: gild (v), sing (v) :: song (n) .Change of

stress is mostly observed in verb-noun pairs, eg transport> to

transport and much more seldom in verb-adjective pairs, to prostrate>

prostrate. The difference in stress often appeared after the verb was

formed and was not therefore connected with the formation of the new

word.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Table of Contents

- How many morphemes are in Unfortunately?

- What is the root of the word unfortunately?

- How many Morphemes does the word removal have?

- How many morphemes are in a banana?

- Is I’m one or two Morphemes?

- Is babies one or two Morphemes?

- Is didn’t a morpheme?

- Do names count as Morphemes?

- How many morphemes are in everybody?

- Does Oh count as a morpheme?

- What are Morphemes and examples?

- What are the three types of morphemes?

- What are the Derivational Morphemes?

- How are Morphemes classified?

- Do morphemes include inflectional endings?

- What is the difference between word and morpheme?

- How many morphemes are in Monster?

- Is girlfriend a morpheme?

- How many morphemes are in thanks?

- What means morpheme?

- What is a full morpheme?

- What is bound morpheme and example?

- Are morphemes and syllables the same?

- Are closed syllables Morphemes?

- Are base words Morphemes?

- How many syllables is jumped Morphemes?

- Is jumped a 2 syllable word?

- How many syllables is jumping?

- How many syllables jump has?

two morphemes

How many morphemes are in Unfortunately?

four morphemes

What is the root of the word unfortunately?

unfortunately (adv.) 1540s, “in an unfortunate manner, by ill-fortune,” from unfortunate + -ly (2).

How many Morphemes does the word removal have?

| # | A Morpheme | B Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | ectomy | removal |

| 6 | ennial | year |

| 7 | epi | on |

| 8 | escent | growing |

For example, running is two morphemes “run” and -ing.

Is I’m one or two Morphemes?

Each phonological word must have at least one stressed syllable, so I’m cannot consist of more than one phonological word. two morphosyntactic words: the full forms I and am are both free words, you could reverse the word order to am I in questions.

Is babies one or two Morphemes?

The word baby is comprised of two morphemes; the free base element and the diminutive suffix in this case .

Is didn’t a morpheme?

We will say that there is one morpheme for “not” and that it always shows up at the beginning of a verb and it always starts with n but it has two different forms nae- and ne-….Words and Parts of Words.

| Meaning | I didn’t read it. |

|---|---|

| Unaccounted for | not |

Do names count as Morphemes?

DO NOT count: 2 Compound words, reduplications, and proper names count as single words (e.g. fireman, choo-choo, Big Bird). 3 Irregular past tense verbs and irregular plurals count as one morpheme (e.g. took, went, mice, men).

How many morphemes are in everybody?

18 Cards in this Set

| uhhhm, uhuh, um er, uh aha, etc. | placeholders = don’t count |

|---|---|

| anybody, somebody, everybody, everyone, anyone, someone, | indefinite pronouns = 1 |

| a, the, an | articles = 1 |

| plural ‘s, posessive ‘s 3rd pers sing -s, regular past -ed, present progressive -ing | Inflections = 1 morpheme |

Does Oh count as a morpheme?

Words such as ”oh”, ”mmm”, and ”uh-huh” do not count as morphemes, but how about words such as ”okay” and ”hey”?

What are Morphemes and examples?

A morpheme is the smallest linguistic part of a word that can have a meaning. In other words, it is the smallest meaningful part of a word. Examples of morphemes would be the parts “un-“, “break”, and “-able” in the word “unbreakable”.

What are the three types of morphemes?

There are three ways of classifying morphemes:

- free vs. bound.

- root vs. affixation.

- lexical vs. grammatical.

What are the Derivational Morphemes?

In grammar, a derivational morpheme is an affix—a group of letters added before the beginning (prefix) or after the end (suffix)—of a root or base word to create a new word or a new form of an existing word.

How are Morphemes classified?

Morphemes are the smallest units in a language that have meaning. They can be classified as free morphemes, which can stand alone as words, or bound morphemes, which must be combined with another morpheme to form a complete word. Bound morphemes typically appear as affixes in the English language.

Do morphemes include inflectional endings?

Meaning and Examples of Inflectional Morphemes Dr. Inflectional morphemes in English include the bound morphemes -s (or -es); ‘s (or s’); -ed; -en; -er; -est; and -ing. These suffixes may even do double- or triple-duty.

What is the difference between word and morpheme?

A morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit in a language. A morpheme is not necessarily the same as a word. The main difference between a morpheme and a word is that a morpheme sometimes does not stand alone, but a word, by definition, always stands alone.

How many morphemes are in Monster?

Answer. It has three morphemes: the prefix in, the base word just, and the suffix ice.

Is girlfriend a morpheme?

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaningful language. “Girl” is a morpheme, as is “skip.” “Girlfriend” has two morphemes, as does “skipper”. Some morphemes can be free (as in girl, skip, and type) whereas other morphemes are bound (as in huck, funct, and ept). A free morpheme has meaning, a bound morpheme does not.

How many morphemes are in thanks?

What means morpheme?

A “morpheme” is a short segment of language that meets three basic criteria: 1. It is a word or a part of a word that has meaning. 2. It cannot be divided into smaller meaningful segments without changing its meaning or leaving a meaningless remainder.

What is a full morpheme?

In English grammar and morphology, a morpheme is a meaningful linguistic unit consisting of a word such as dog, or a word element, such as the -s at the end of dogs, that can’t be divided into smaller meaningful parts. Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning in a language.

What is bound morpheme and example?

Morphemes that can only be attached to another part of a word (cannot stand alone) are called bound morphemes. Examples: pre-, dis-, in-, un-, -ful, -able, -ment, -ly, -ise. pretest, discontent, intolerable, receive.

Are morphemes and syllables the same?

Morphemes are a stretch of sound and meaning together. Syllables are divisions that are based on pronunciation, not on meaning. Morphemes are divisions that are based on meaning.

Are closed syllables Morphemes?

Syllables are closed when they end in a consonant and open when they end in a vowel. They are uncovered when they begin with a vowel and covered when they begin with a consonant. In the word ruchka (“handle”), morphemes for example, there are two syllables (ru-chka) but three morphemes (ruch-k-a).

Are base words Morphemes?

Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning. Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

How many syllables is jumped Morphemes?

Syllables in Jumped

| How many syllables are in jumped: | 1 |

|---|---|

| Syllables counted programmatically: | N/A |

| Divide jumped into Syllables: | jumped |

| Total number Words: | 1 |

| Characters (all | no spaces | with spaces): | 6 | 6 | 6 (Sequential spaces are not counted) |

Is jumped a 2 syllable word?

Wondering why jumped is 1 syllable? Contact Us!

How many syllables is jumping?

2 syllables

How many syllables jump has?

1 syllable

What is a Morpheme?

Morphemes are what make up words. It is not always true that morphemes are words. Some single morphemes can be words, while other words have two or more morphemes within them. It is also incorrect to think of morphemes as syllables. Many words have two or more syllables but only one morpheme. “Banana”, “apple”, “papaya” and “nanny” are just a few examples. On the other hand, many words have two morphemes and only one syllable; examples include “cats”, “runs,” and “barked”.

The word “pins” contains two morphemes: “pin” and the plural suffix “-s.”

In so-called isolating languages, like Vietnamese, each word contains a single morpheme; in languages such as English, words often contain multiple morphemes.

Types of Morphemes:

Free morpheme:

A morpheme that can stand alone as a word without another morpheme. It does not need anything attached to it to make a word. “Cat” is a free morpheme.

Bound morpheme:

A sound or a combination of sounds that cannot stand alone as a word. The “s” in “cats” is a bound morpheme, and it does not have any meaning without the free morpheme “cat”.

Inflectional morpheme:

This morpheme is always a suffix. The “s” in “cats” is an inflectional morpheme. An inflectional morpheme creates a change in the function of the word. Example: the “d” in “invited” indicates past tense. English has only seven inflectional morphemes: “-s” (plural) and “-s” (possessive) are noun inflections; “-s” ( 3rd-person singular), “-ed” ( past tense), “-en” (past participle), and “-ing” ( present participle) are verb inflections; “-er” (comparative) and “-est” (superlative) are adjective and adverb inflections.

Derivational morpheme:

This type of morpheme changes the meaning of the word or the part of speech or both. Derivational morphemes often create new words. Example: the prefix and derivational morpheme “un” added to “invited” changes the meaning of the word.

Allomorphs:

Different phonetic forms or variations of a morpheme. Example: The final morphemes in the following words are pronounced differently, but they all indicate plurality: dogs, cats, and horses.

Base:

A morpheme that gives a word its meaning. The base morpheme “cat” gives the word “cats” its meaning.

Affix:

A morpheme that comes at the beginning (prefix) or the ending (suffix) of a base morpheme. Note: An affix usually is a morpheme that cannot stand alone. Examples: “-ful,” “-ly”, “-ity,” “-ness.” A few exceptions, namely “-able,” “-like” and “-less” can also stand alone as words.

Prefix:

An affix that comes before a base morpheme. “The ‘in’ in the word ‘inspect’ is a prefix.”

Examples of prefixes:

- Ab-: away from (absent, abnormal)

- Ad-: to, toward (advance, addition)

- After-: later, behind (aftermath, afterward)

- Anti-: against, opposed (antibiotic, antigravity)

- Auto-: self (automobile, autobiography)

- Bi-: two (bicycle, biceps)

- Com, con, co-: with, together (commune, concrete)

- Contra- : against (contradict, contrary)

- De-: downward, undo (deflate, defect)

- Dis-: not (dislike, distrust)

- Extra-: outside (extravagant, extraterrestrial)

- Im-: not (impose, imply)

- In-: into, not include, incurable)

- Inter-: among (interact, international)

- Macro- : large (macroeconomics, macrobiotics)

- Magni- : great (magnify, magnificent)

- Mega-: huge (megaphone, megabucks)

- Micro-: small (microscope, microbe)

- Mis-: wrongly (mistake, mislead)

- Non-: not (nonsense, nonviolent)

- Over-: above, beyond (overflow, overdue)

- Post-: after (postdate, postmark)

- Pre-: before, prior to (preheat, prehistoric)

- Pro-: in favor of (protect, probiotic, pro-survival)

- Re-: again (repeat, revise)

- Sub-: under, beneath (submarine, subject)

- Super-: above, beyond superior (supernatural)

- Tele-: far (telescope, telephone)

Suffix:

An affix that comes after a base morpheme. “The ‘s’ in ‘cats’ is a ”

Examples of suffixes: -ant: one who (assistant)

- -ar: one who (liar)

- -arium: place for (aquarium) -ble: inclined to (gullible) -ent: one who (resident)

- -er: one who (teacher)

- -er: more (brighter)

- -ery, ry: (products pottery, bakery) -ess: one who [female] (actress)

- -est: most (hottest)

- -ful: full of (mouthful)

- -ing: [present tense] (smiling)

- -less: without (motherless) -ling: small (fledgling)

- -ly: every (weekly) -ly: (adverb) happily

- -ness: state of being (happiness) -ology: study of (biology)

- -ous: full of (wondrous)

- -s, es: more than one (boxes) -y: state of (sunny)

Homonyms:

Morphemes that are spelled the same but have different Examples: “bear” (an animal) and “bear” (to carry); “plain” (simple) and “plain” ( a level area of land).

Heteronym:

One of two or more words (not necessarily single morphemes) that have identical spellings but different meanings and pronunciations, such as “row” (a series of objects arranged in a line), pronounced (rō), and “row” (a fight), pronounced (rou).

Homophones:

Morphemes that sound alike but have different meanings and spellings. Examples: “bear” / “bare”, “plain” / “plane”, “cite” / “sight” / “site”.

Note: You will find more about Homonyms, Homophones, and Heteronyms in

Examples of morphemes in Words:

One morpheme:

- one syllable: boy

- two syllables: desire, lady, water

- three syllables: crocodile

- four syllables: salamander

Two morphemes:

- boy + ish

- desire + able

Three morphemes:

- boy + ish + ness

- desire + able + ity

Four morphemes:

- gentle + man + li + ness

- un + desire + able + ity

More than four morphemes:

- un + gentle + man + li + ness

- anti + dis + establish + ment + ari + an + ism

Definition and Examples of Morphemes in English

Updated on February 03, 2020

In English grammar and morphology, a morpheme is a meaningful linguistic unit consisting of a word such as dog, or a word element, such as the -s at the end of dogs, that can’t be divided into smaller meaningful parts.

Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning in a language. They are commonly classified as either free morphemes, which can occur as separate words or bound morphemes, which can’t stand alone as words.

Many words in English are made up of a single free morpheme. For example, each word in the following sentence is a distinct morpheme: «I need to go now, but you can stay.» Put another way, none of the nine words in that sentence can be divided into smaller parts that are also meaningful.

Etymology

From the French, by analogy with phoneme, from the Greek, «shape, form.»

Examples and Observations

- A prefix may be a morpheme:

«What does it mean to pre-board? Do you get on before you get on?»

—George Carlin - Individual words may be morphemes:

«They want to put you in a box, but nobody’s in a box. You’re not in a box.»

—John Turturro - Contracted word forms may be morphemes:

«They want to put you in a box, but nobody‘s in a box. You‘re not in a box.»

—John Turturro - Morphs and Allomorphs

«A word can be analyzed as consisting of one morpheme (sad) or two or more morphemes (unluckily; compare luck, lucky, unlucky), each morpheme usually expressing a distinct meaning. When a morpheme is represented by a segment, that segment is a morph. If a morpheme can be represented by more than one morph, the morphs are allomorphs of the same morpheme: the prefixes in- (insane), il- (illegible), im- (impossible), ir- (irregular) are allomorphs of the same negative morpheme.»

—Sidney Greenbaum, The Oxford English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 1996 - Morphemes as Meaningful Sequences of Sounds

«A word cannot be divided into morphemes just by sounding out its syllables. Some morphemes, like apple, have more than one syllable; others, like -s, are less than a syllable. A morpheme is a form (a sequence of sounds) with a recognizable meaning. Knowing a word’s early history, or etymology, may be useful in dividing it into morphemes, but the decisive factor is the form-meaning link.

«A morpheme may, however, have more than one pronunciation or spelling. For example, the regular noun plural ending has two spellings (-s and -es) and three pronunciations (an s-sound as in backs, a z-sound as in bags, and a vowel plus z-sound as in batches). Similarly, when the morpheme -ate is followed by -ion (as in activate-ion), the t of -ate combines with the i of -ion as the sound ‘sh’ (so we might spell the word ‘activashun’). Such allomorphic variation is typical of the morphemes of English, even though the spelling does not represent it.»

—John Algeo, The Origins and Development of the English Language, 6th ed. Wadsworth, 2010 - Grammatical Tags

«In addition to serving as resources in the creation of vocabulary, morphemes supply grammatical tags to words, helping us to identify on the basis of form the parts of speech of words in sentences we hear or read. For example, in the sentence Morphemes supply grammatical tags to words, the plural morpheme ending {-s} helps identify morphemes, tags, and words as nouns; the {-ical} ending underscores the adjectival relationship between grammatical and the following noun, tags, which it modifies.»

—Thomas P. Klammer et al. Analyzing English Grammar. Pearson, 2007 - Language Acquisition

«English-speaking children usually begin to produce two-morpheme words in their third year, and during that year the growth in their use of affixes is rapid and extremely impressive. This is the time, as Roger Brown showed, when children begin to use suffixes for possessive words (‘Adam’s ball’), for the plural (‘dogs’), for present progressive verbs (‘I walking’), for third-person singular present tense verbs (‘he walks’), and for past tense verbs, although not always with complete corectness (‘I brunged it here’) (Brown 1973). Notice that these new morphemes are all of them inflections. Children tend to learn derivational morphemes a little later and to continue to learn about them right through childhood . . ..»

—Peter Bryant and Terezinha Nunes, «Morphemes and Literacy: A Starting Point.» Improving Literacy by Teaching Morphemes, ed. by T. Nunes and P. Bryant. Routledge, 2006

Pronunciation: MOR-feem