Download Article

Download Article

Spoken word is a great way to express your truth to others through poetry and performance. To write a spoken word piece, start by picking a topic or experience that triggers strong feelings for you. Then, compose the piece using literary devices like alliteration, repetition, and rhyme to tell your story. Polish the piece when it is done so you can perform it for others in a powerful, memorable way. With the right approach to the topic and a strong attention to detail, you can write a great spoken word piece in no time.

-

1

Choose a topic that triggers a strong feeling or opinion. Maybe you go for a topic that makes you angry, like war, poverty, or loss, or excited, like love, desire, or friendship. Think of a topic that you feel you can explore in depth with passion.[1]

- You may also take a topic that feels broad or general and focus on a particular opinion or perspective you have on it. For example, you may look at a topic like “love” and focus on your love for your big sister. Or you may look at a topic like “family” and focus on how you made your own family with close friends and mentors.

-

2

Focus a memorable moment or experience in your life. Pick an experience that was life changing or shifted your perspective on the world in a profound way. The moment or experience could be recent or from childhood. It could be a small moment that became meaningful later or an experience that you are still recovering from.[2]

- For example, you may choose to write about the moment you realized you loved your partner or the moment you met your best friend. You can also write about a childhood experience in a new place or an experience you shared with your mother or father.

Advertisement

-

3

Respond to a troubling question or idea. Some of the best spoken word comes from a response to a question or idea that makes you think. Pick a question that makes you feel unsettled or curious. Then, write a detailed response to create the spoken word piece.

- For example, you may try responding to a question like “What are you afraid of?” “What bothers you about the world?” or “Who do you value the most in your life?”

-

4

Watch videos of spoken word pieces for inspiration. Look up videos of spoken word poets who tackle interesting subjects from a unique point of view. Pay attention to how the performer tells their truth to engage the audience. You may watch spoken word pieces like:

- “The Type” by Sarah Kay.[3]

- “When a Boy Tells You He Loves You” by Edwin Bodney.[4]

- “Lost Voices” by Darius Simpson and Scout Bostley.[5]

- “The Drug Dealer’s Daughter” by Sierra Freeman.[6]

- “The Type” by Sarah Kay.[3]

Advertisement

-

1

Come up with a gateway line. The gateway line is usually the first line of the piece. It should sum up the main topic or theme. The line can also introduce the story you are about to tell in a clear, eloquent way. A good way to find a gateway line is to write down the first ideas or thoughts that pop into your head when you focus on a topic, moment, or experience.[7]

- For example, you may come up with a gateway line like, “The first time I saw her, I was alone, but I did not feel alone.” This will then let the reader know you are going to be talking about a female person, a “her,” and about how she made you feel less lonely.

-

2

Use repetition to reinforce an idea or image. Most spoken word will use repetition to great effect, where you repeat a phrase or word several times in the piece. You may try repeating the gateway line several times to remind the reader of the theme of your piece. Or you may repeat an image you like in the piece so the listener is reminded of it again and again.[8]

- For example, you may repeat the phrase “The first time I saw her” in the piece and then add on different endings or details to the phrase.

-

3

Include rhyme to add flow and rhythm to the piece. Rhyme is another popular device used in spoken word to help the piece flow better and sound more pleasing to listeners. You may follow a rhyme scheme where you rhyme every other sentence or every third sentence in the piece. You can also repeat a phrase that rhymes to give the piece a nice flow.[9]

- For example, you may use a phrase like «Bad dad» or «Sad dad» to add rhyme. Or you may try rhyming every second sentence with the gateway line, such as rhyming «The first time I saw him» with «I wanted to dive in and swim.»

- Avoid using rhyme too often in the piece, as this can make it sound too much like a nursery rhyme. Instead only use rhyme when you feel it will add an extra layer of meaning or flow to the piece.

-

4

Focus on sensory details and description. Think about how settings, objects, and people smell, sound, look, taste, and feel. Describe the topic of your piece using your 5 senses so the reader can become immersed in your story.

- For example, you may describe the smell of someone’s hair as «light and floral» or the color of someone’s outfit as «as red as blood.» You can also describe a setting through what it sounded like, such as «the walls vibrated with bass and shouting,» or an object through what it tasted like, such as «her mouth tasted like fresh cherries in summer.»

-

5

End with a strong image. Wrap up the piece with an image that connects to the topic or experience in your piece. Maybe you end with a hopeful image or with an image that speaks to your feelings of pain or isolation.

- For example, you may describe losing your best friend at school, leaving the listener with the image of your pain and loss.

-

6

Conclude by repeating the gateway line. You can also end by repeating the gateway line once more, calling back to the beginning of the piece. Try adding a slight twist or change to the line so the meaning of it is deepened or changed.

- For example, you may take an original gateway line like, “The first time I saw her” and change it to “The last time I saw her” to end the poem with a twist.

Advertisement

-

1

Read the piece aloud. Once you have finished a draft of the spoken word piece, read it aloud several times. Pay attention to how it flows and whether it has a certain rhythm or style. Use a pen or pencil to underline or highlight any lines that sound awkward or unclear so you can revise them later.[10]

-

2

Show the piece to others. Get friends, family members, or mentors to read the piece and give you feedback. Ask them if they feel the piece feels like it represents your style and attitude. Have others point out any lines or phrases they find wordy or unclear so you can adjust them.[11]

-

3

Revise the piece for flow, rhythm, and style. Check that the piece has a clear flow and rhythm. Simplify lines or phrases to reflect how you express yourself in casual conversation or among friends. You should also remove any jargon that feels too academic or complex, as you do not want to alienate your listener. Instead, use language that you feel comfortable with and know well so you can show off your style and attitude in the piece.[12]

- You may need to revise the piece several times to find the right flow and meaning. Be patient and edit as much as you need until the piece feels finished.

Advertisement

-

1

Memorize the piece. Read the piece aloud several times. Then, try to repeat it aloud without looking at the written words, working line by line or section by section. It may take several days for you to memorize the piece in its entirety so be patient and take your time.[13]

- You may find it helpful to ask a friend or family member to test you when you have memorized the piece to ensure you can repeat every word by heart.

-

2

Use your voice to convey emotion and meaning to the audience. Project your voice when you perform. Make sure you enunciate words or phrases that are important in the piece. You can also raise or lower your voice using a consistent pattern or rhythm when you perform. Try speaking in different registers to give the piece variety and flow.[14]

- A good rule of thumb is to say the gateway line or a key phrase louder than other words every time you repeat it. This can help you find a sense of rhythm and flow.

-

3

Express yourself with eye contact and facial gestures. Maintain eye contact with the audience when you perform the poem, rather than looking down or at a piece of paper. Use your mouth and face to communicate any emotions or thoughts expressed in the poem. Make facial gestures like a look of surprise when you describe a realization, or a look of anger when you talk about an injustice or troubling moment.[15]

- You can also use your hands to help you express yourself. Make hand gestures to the audience to keep them engaged.

- Keep in mind the audience will not really be paying attention your lower body or your legs, so you have to rely on your face, arms, and upper body in your performance.

-

4

Practice in front of a mirror until you feel confident. Use a mirror to get a sense of your facial expressions and your hand gestures. Maintain eye contact in the mirror and project your voice so you appear confident to the audience.

- Once you feel comfortable performing to the mirror, you may decide to perform for friends or family. You can also perform the spoken word piece at a poetry slam or an open mic night once you feel it is ready to share with others.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

Must there be a rhythm?

No. The goal should be to write natural-sounding speech. Most people do not naturally employ rhythm in their speech.

-

Question

What if I have no mirror at home for practicing?

You can practice with a friend or family member instead. Then, ask them to review your performance and offer constructive criticism.

-

Question

Why is rhyme important to the rhythm of the spoken word?

Actually, rhyme is not especially important in speech patterns, although it can certainly be used to comic or fanciful effect. If this question has been taken from a test, you should simply respond with whatever your teacher or textbook has told you about spoken rhyme.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To write spoken word, start by coming up with a gateway line, which sums up the main topic or theme and is typically the first line of the piece. As you write, work some repetition into your piece to reinforce the main ideas or images. You should also include rhyme to add flow and rhythm to the piece. Additionally, incorporate sensory details, such as how things felt, smelt, or tasted, to help draw your listener into the world you’ve created. Finally, end with a strong image that will stay with your audience or repeat the gateway line for closure. To learn how to end your spoken word piece, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 75,673 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Akinwumi Shulammite

Oct 24, 2022

«It’s inspiring, when I saw this article I became more curious about the spoken word that I want to practice and…» more

Did this article help you?

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

чем все закончится

как это заканчивается

как все закончится

как она заканчивается

чем это заканчивается

чем кончится

как она закончится

чем это закончится

чем она заканчивается

чем все закончилось

как все заканчивается

чем он закончится

чем закончится

чем все кончится

Нош It Ends

The beautiful thing is that no one knows how it ends.

It’s not bad, but we’ll see how it ends.

That way, if I die before I finish I know how it ends.

That’s not they say how it ends.

If you want, I can tell you how it ends.

All right, but don’t tell me how it ends.

I don’t know how it ends.

Don’t tell me how it ends.

I have to know how it ends.

And I know how it ends… with the loud tolling of bells at sunset.

You who are working there should know how it ends.

Let me guess how it ends.

Maybe we don’t know how it ends.

And how it ends up for everybody.

I don’t know how it ends because they don’t know how it ends.

Whatever the number, look at how it ends.

Not just because we know how it ends.

You think you know how it ends.

Maybe because you know how it ends.

Результатов: 410. Точных совпадений: 410. Затраченное время: 139 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Today’s guest post is by Avery White. Avery writes short stories and spoken word, and is currently working on his first novel for middle grade readers. He runs thirdpersoncreative.com, a site dedicated to weaponizing stories against injustice, prejudice, and passivity in the world around us.

“Respect the poet!” the crowd shouts at a couple at the bar oblivious to what’s going on.

Silence.

Slowly, alliterative spoken word sends chills across my neck, down my arm, and into my chest.

I’m feeling words as my eyes stare rapt at the stage.

Literary devices fly with syllables punctuated by inflection. Poetry one line, prose the next. The performer pauses. It’s 2008, and I’m hooked.

I was first introduced to spoken word while taking a creative writing class in college. I then got involved with a local spoken word community in Bryan, Texas called Mic Check, where the scene above happens weekly.

And today, I’m showing you how to craft your own powerful spoken word piece.

How to Speak Spit Spoken Word

What!?

You mean you weren’t born with an innate ability to write poetry, combine it with performing arts techniques, and rhythmically deliver a piece with clever intonation?

Performance poets weren’t either. Even if their names are Sarah Kay or Madi Mae.

Do you have feelings?

Do you wish you could let them go out, terrorize the neighborhood for a bit, and then come home to you without doing any damage (the kind that costs you money)?

Got a pen?

Let’s do this. Here are four steps to writing spoken word:

1. Tell a Story

If you’ve never written spoken word before, you might feel overwhelmed, unsure where to start. But this type of writing isn’t as foreign as you might think. It can follow the same pattern as a conventional story: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

First, pick a theme you’re passionate about. Putting something down on paper knowing that you’re going to read it out loud later is terrifying, but having passion from the start will help carry you through. And if you’re a writer, you need practice putting fear down anyways!

While there are as many ways to begin writing as there are poets, a way that I have found particularly effective is to start with a “gateway line,” a single line that captures your theme. For example:

- “Do not keep the silence golden.”

- “Looking past Earth.”

- “Life is not ajar.”

To demonstrate this, I’ll write a (short) piece around the following line:

“Practice is failing on purpose.”

Now that I have my gateway line, I’m ready to revisit my dramatic structure: what can I surround my line with? At this point I might make a list of a few plot options:

- A little boy learning to ride a bike

- A guy practicing how he’s going to start a conversation with the girl of his dreams

- A girl exploring the definition of true beauty

I fully intend to reveal something about practice that applies to craft development, but I’m going to do it by juxtaposing it with something wildly different. This will show the audience something about practicing their craft, as well as the subject of the plot.

Spoken word lets you do that. How cool is that!?

2. Flesh It Out

Now that you’ve chosen your plot, it’s time to flesh it out into a story illustrating your theme. This is where you, as the writer, get to shine! How compact can you make it?

At this point you might be thinking that this is remarkably similar to writing anything else. You’re exactly right — it is. That’s why I’m writing this out, to show you that you can do it!

I’ve decided to write a piece about an eight-year-old boy who decides to try to ride his bike sans training wheels. Now, I ask questions to flesh that concept out:

What does he look like? Where is this? How long as he been trying to do this? Why is this important?

Most importantly, why should my audience care about him?

First draft:

Age eight with skinned knees bleeding from the last attempt he pushes two blue wheels uphill.

This time.

Salt touches his tongue as he tilts his face towards the summit. This was his Everest.

He was done training. The two wheels sat lifeless in the garage watching him from a distance.

He believed that with enough speed he could roll forever. The extra weight only slowed him down.

He fought to push the past crashes from his mind as he trudged up Mount Failure.

This was his practice.

3. Read It Out Loud

Once you have something down, read it out loud to evaluate how it sounds. Do you like what you hear?

Spoken word fills the gap between predictable patterns found in traditional forms of poetry and the art of prose. Every literary device, every poetic device, and anything clever you can think of to do while you’re on stage is all fair game. For now, let’s revisit the first draft, tighten the diction, and spice things up with a bit of poetry.

Second draft:

Age eight, and skinned knees pleading he pushes two blue wheels uphill.

This time.

Salt touches tongue as dirt-faced determination drives him to the summit. His Everest.

Two training wheels cry abandoned. Concrete floors and walls lined with tools can get so lonely.

He believed that with enough speed he could roll forever.

Long enough to run the errands that his mother couldn’t.

He fought to push past crashes and knee slashes from his mind as he scaled Mount Failure.

This was his practice.

4. Perform

Now that you like what you’re hearing, start asking performance related questions. This could include questions related to theatre, music, or even dance.

Do you want a part of it to read faster to give it more of a hip-hop sound? Or slower to make it more dramatic? Either way, it’s up to you to figure out how you’re going to read it.

And there you have it — four steps to writing your first spoken word.

Do you write spoken word poetry? What do you find most challenging about it? Let me know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Take fifteen minutes to create a gateway line and draft your own short spoken word. Your gateway line doesn’t necessarily have to appear verbatim in the piece.

Post your gateway line and your spoken word in the comments! And if you share, remember to leave feedback for your fellow writers.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a performance art. For recordings of books or dialog, see Audiobook. For the 2009 film, see Spoken Word (film).

Spoken word refers to an oral poetic performance art that is based mainly on the poem as well as the performer’s aesthetic qualities. It is a late 20th century continuation of an ancient oral artistic tradition that focuses on the aesthetics of recitation and word play, such as the performer’s live intonation and voice inflection. Spoken word is a «catchall» term that includes any kind of poetry recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues.[1] Unlike written poetry, the poetic text takes its quality less from the visual aesthetics on a page, but depends more on phonaesthetics, or the aesthetics of sound.

History[edit]

Spoken word has existed for many years; long before writing, through a cycle of practicing, listening and memorizing, each language drew on its resources of sound structure for aural patterns that made spoken poetry very different from ordinary discourse and easier to commit to memory.[2] «There were poets long before there were printing presses, poetry is primarily oral utterance, to be said aloud, to be heard.»[3]

Poetry, like music, appeals to the ear, an effect known as euphony or onomatopoeia, a device to represent a thing or action by a word that imitates sound.[4] «Speak again, Speak like rain» was how Kikuyu, an East African people, described her verse to author Isak Dinesen,[5] confirming a comment by T. S. Eliot that «poetry remains one person talking to another».[6]

The oral tradition is one that is conveyed primarily by speech as opposed to writing,[7] in predominantly oral cultures proverbs (also known as maxims) are convenient vehicles for conveying simple beliefs and cultural attitudes.[8] «The hearing knowledge we bring to a line of poetry is a knowledge of a pattern of speech we have known since we were infants».[9]

Performance poetry, which is kindred to performance art, is explicitly written to be performed aloud[10] and consciously shuns the written form.[11] «Form», as Donald Hall records «was never more than an extension of content.»[12]

Performance poetry in Africa dates to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, while elegiac and panegyric court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger and Volta river valleys.[13] One of the best known griot epic poems was created for the founder of the Mali Empire, the Epic of Sundiata. In African culture, performance poetry is a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[14] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions: political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the «talking drum», which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[15][16] Although, they could be included in performances of the griots.

In ancient Greece, the spoken word was the most trusted repository for the best of their thought, and inducements would be offered to men (such as the rhapsodes) who set themselves the task of developing minds capable of retaining and voices capable of communicating the treasures of their culture.[17] The Ancient Greeks included Greek lyric, which is similar to spoken-word poetry, in their Olympic Games.[18]

Development in the United States[edit]

This poem is about the International Monetary Fund; the poet expresses his political concerns about the IMF’s practices and about globalization.

Vachel Lindsay helped maintain the tradition of poetry as spoken art in the early twentieth century.[19] Robert Frost also spoke well, his meter accommodating his natural sentences.[20] Poet laureate Robert Pinsky said, «Poetry’s proper culmination is to be read aloud by someone’s voice, whoever reads a poem aloud becomes the proper medium for the poem.»[21] «Every speaker intuitively courses through manipulation of sounds, it is almost as though ‘we sing to one another all day’.»[9] «Sound once imagined through the eye gradually gave body to poems through performance, and late in the 1950s reading aloud erupted in the United States.»[20]

Some American spoken-word poetry originated from the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance,[22] blues, and the Beat Generation of the 1960s.[23] Spoken word in African-American culture drew on a rich literary and musical heritage. Langston Hughes and writers of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired by the feelings of the blues and spirituals, hip-hop, and slam poetry artists were inspired by poets such as Hughes in their word stylings.[24]

The Civil Rights Movement also influenced spoken word. Notable speeches such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s «I Have a Dream», Sojourner Truth’s «Ain’t I a Woman?», and Booker T. Washington’s «Cast Down Your Buckets» incorporated elements of oration that influenced the spoken word movement within the African-American community.[24] The Last Poets was a poetry and political music group formed during the 1960s that was born out of the Civil Rights Movement and helped increase the popularity of spoken word within African-American culture.[25] Spoken word poetry entered into wider American culture following the release of Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem «The Revolution Will Not Be Televised» on the album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox in 1970.[26]

The Nuyorican Poets Café on New York’s Lower Eastside was founded in 1973, and is one of the oldest American venues for presenting spoken-word poetry.[27]

In the 1980s, spoken-word poetry competitions, often with elimination rounds, emerged and were labelled «poetry slams». American poet Marc Smith is credited with starting the poetry slam in November 1984.[18] In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam took place in Fort Mason, San Francisco.[28] The poetry slam movement reached a wider audience following Russell Simmons’ Def Poetry, which was aired on HBO between 2002 and 2007. The poets associated with the Buffalo Readings were active early in the 21st century.

International development[edit]

Kenyan spoken word poet Mumbi Macharia.

Outside of the United States, artists such as French singer-songwriters Léo Ferré and Serge Gainsbourg made personal use of spoken word over rock or symphonic music from the beginning of the 1970s in such albums as Amour Anarchie (1970), Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971), and Il n’y a plus rien (1973), and contributed to the popularization of spoken word within French culture.

In the UK, musicians who have performed spoken word lyrics include Blur,[29] The Streets and Kae Tempest.

In 2003, the movement reached its peak in France with Fabien Marsaud aka Grand Corps Malade being a forerunner of the genre.[30][31]

In Zimbabwe spoken word has been mostly active on stage through the House of Hunger Poetry slam in Harare, Mlomo Wakho Poetry Slam in Bulawayo as well as the Charles Austin Theatre in Masvingo. Festivals such as Harare International Festival of the Arts, Intwa Arts Festival KoBulawayo and Shoko Festival have supported the genre for a number of years.[32]

In Nigeria, there are poetry events such as Wordup by i2x Media, The Rendezvous by FOS (Figures Of Speech movement), GrrrAttitude by Graciano Enwerem, SWPC which happens frequently, Rhapsodist, a conference by J19 Poetry and More Life Concert (an annual poetry concert in Port Harcourt) by More Life Poetry. Poets Amakason, ChidinmaR, oddFelix, Kormbat, Moje, Godzboi, Ifeanyi Agwazia, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Worden Enya, Resame, EfePaul, Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem, Oruz Kennedy, Agbeye Oburumu, Fragile MC, Lyrical Pontiff, Irra, Neofloetry, Toby Abiodun, Paul Word, Donna, Kemistree and PoeThick Samurai are all based in Nigeria. Spoken word events in Nigeria[33] continues to grow traction, with new, entertaining and popular spoken word events like The Gathering Africa, a new fusion of Poetry, Theatre, Philosophy and Art, organized 3 times a year by the multi-talented beauty Queen, Rei Obaigbo [34] and the founder [35] of Oreime.com.

In Trinidad and Tobago, this art form is widely used as a form of social commentary and is displayed all throughout the nation at all times of the year. The main poetry events in Trinidad and Tobago are overseen by an organization called the 2 Cent Movement. They host an annual event in partnership with the NGC Bocas Lit Fest and First Citizens Bank called «The First Citizens national Poetry Slam», formerly called «Verses». This organization also hosts poetry slams and workshops for primary and secondary schools. It is also involved in social work and issues.

In Ghana, the poetry group Ehalakasa led by Kojo Yibor Kojo AKA Sir Black, holds monthly TalkParty events (collaborative endeavour with Nubuke Foundation and/ National Theatre of Ghana) and special events such as the Ehalakasa Slam Festival and end-of-year events. This group has produced spoken-word poets including, Mutombo da Poet,[36] Chief Moomen, Nana Asaase, Rhyme Sonny, Koo Kumi, Hondred Percent, Jewel King, Faiba Bernard, Akambo, Wordrite, Natty Ogli, and Philipa.

The spoken word movement in Ghana is rapidly growing that individual spoken word artists like MEGBORNA,[37] are continuously carving a niche for themselves and stretching the borders of spoken word by combining spoken word with 3D animations and spoken word video game, based on his yet to be released poem, Alkebulan.

Megborna performing at the First Kvngs Edition of the Megborna Concert, 2019

In Kumasi, the creative group CHASKELE holds an annual spoken word event on the campus of KNUST giving platform to poets and other creatives. Poets like Elidior The Poet, Slimo, T-Maine are key members of this group.

In Kenya, poetry performance grew significantly between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was through organisers and creative hubs such as Kwani Open Mic, Slam Africa, Waamathai’s, Poetry at Discovery, Hisia Zangu Poetry, Poetry Slam Africa, Paza Sauti, Anika, Fatuma’s Voice, ESPA, Sauti dada, Wenyewe poetry among others. Soon the movement moved to other counties and to universities throughout the country. Spoken word in Kenya has been a means of communication where poets can speak about issues affecting young people in Africa. Some of the well known poets in Kenya are Dorphan, Kenner B, Namatsi Lukoye, Raya Wambui, Wanjiku Mwaura, Teardrops, Mufasa, Mumbi Macharia, Qui Qarre, Sitawa Namwalie, Sitawa Wafula, Anne Moraa, Ngwatilo Mawiyo, Stephen Derwent.[38]

In Israel, in 2011 there was a monthly Spoken Word Line in a local club in Tel-Aviv by the name of: «Word Up!». The line was organized by Binyamin Inbal and was the beginning of a successful movement of spoken word lovers and performers all over the country.

Competitions[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is often performed in a competitive setting. In 1990, the first National Poetry Slam was held in San Francisco.[18] It is the largest poetry slam competition event in the world, now held each year in different cities across the United States.[39] The popularity of slam poetry has resulted in slam poetry competitions being held across the world, at venues ranging from coffeehouses to large stages.

Movement[edit]

Spoken-word poetry is typically more than a hobby or expression of talent. This art form is often used to convey important or controversial messages to society. Such messages often include raising awareness of topics such as: racial inequality, sexual assault and/or rape culture, anti-bullying messages, body-positive campaigns, and LGBT topics. Slam poetry competitions often feature loud and radical poems that display both intense content and sound. Spoken-word poetry is also abundant on college campuses, YouTube, and through forums such as Button Poetry.[40] Some spoken-word poems go viral and can then appear in articles, on TED talks, and on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

See also[edit]

- Greek lyric

- Griot

- Haikai prose

- Hip hop

- List of performance poets

- Nuyorican Poets Café

- Oral poetry

- Performance poetry

- Poetry reading

- Prose rhythm

- Prosimetrum

- Purple prose

- Rapping

- Recitative

- Rhymed prose

- Slam poetry

References[edit]

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (April 8, 2014). A Poet’s Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151011957.

- ^ Hollander, John (1996). Committed to Memory. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573226462.

- ^ Knight, Etheridge (1988). «On the Oral Nature of Poetry». The Black Scholar. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis. 19 (4–5): 92–96. doi:10.1080/00064246.1988.11412887.

- ^ Kennedy, X. J.; Gioia, Dana (1998). An Introduction to Poetry. Longman. ISBN 9780321015563.

- ^ Dinesen, Isak (1972). Out of Africa. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679600213.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1942), «The Music of Poetry» (lecture). Glasgow: Jackson.

- ^ The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005. ISBN 978-0618604999.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: Cultural Attitudes. Metheun.

- ^ a b Pinsky, Robert (1999). The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374526177.

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poets Glossary. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780151011957.

- ^ Parker, Sam (December 16, 2009). «Three-minute poetry? It’s all the rage». The Times.

- ^ Olson, Charles (1950). «‘Projective Verse’: Essay on Poetic Theory». Pamphlet.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers.

- ^ John Conteh-Morgan, John (1994), «African Traditional Drama and Issues in Theater and Performance Criticism», Comparative Drama.

- ^ Finnegan (2012), Oral Literature in Africa, pp. 467-484.

- ^ Stern, Theodore (1957), Drum and Whistle Languages: An Analysis of Speech Surrogates, University of Oregon.

- ^ Bahn, Eugene; Bahn, Margaret L. (1970). A History of Oral Performance. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burgess. p. 10.

- ^ a b c Glazner, Gary Mex (2000). Poetry Slam: The Competitive Art of Performance Poetry. San Francisco: Manic D.

- ^ ‘Reading list, Biography – Vachel Lindsay’ Poetry Foundation.org Chicago 2015

- ^ a b Hall, Donald (October 26, 2012). «Thank You Thank You». The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Sleigh, Tom (Summer 1998). «Robert Pinsky». Bomb.

- ^ O’Keefe Aptowicz, Cristin (2008). Words in Your Face: A Guided Tour through Twenty Years of the New York City Poetry Slam. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-1-933368-82-5.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2003). The Songs in the Key of Black Life: A Rhythm and Blues Nation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96571-3.

- ^ a b «Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word». Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ «The Last Poets». www.nsm.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011), Ben Sisario, «Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62», The New York Times.

- ^ «The History of Nuyorican Poetry Slam» Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Verbs on Asphalt.

- ^ «PSI FAQ: National Poetry Slam». Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ DeGroot, Joey (April 23, 2014). «7 Great songs with Spoken Word Lyrics». MusicTimes.com.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade — Biography | Billboard». www.billboard.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ «Grand Corps Malade». France Today. July 11, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Muchuri, Tinashe (May 14, 2016). «Honour Eludes local writers». NewsDay. Zimbabwe. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Independent, Agency (2 February 2022). «The Gathering Africa, Spokenword Event by Oreime.com». Independent. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo: 2021 Mrs. Nigeria Gears Up for Global Stage». THISDAYLIVE. 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Tarere Obaigbo, Founder Of The Gathering Africa, Wins Mrs Nigeria Pageant — Olisa.tv». 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ «Mutombo The Poet of Ghana presents Africa’s spoken word to the world». TheAfricanDream.net. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ «Meet KNUST finest spoken word artist, Chris Parker ‘Megborna’«. hypercitigh.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ Ekesa, Beatrice Jane (2020-08-18). «Integration of Work and Leisure in the Performance of Spoken Word Poetry in Kenya». Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature. 1 (3): 9–13. doi:10.46809/jcsll.v1i3.23. ISSN 2732-4605.

- ^ Poetry Slam, Inc. Web. November 28, 2012.

- ^ «Home — Button Poetry». Button Poetry.

Further reading[edit]

- «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry.org. 2015.

External links[edit]

- Poetry aloud – examples

|

|

В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации.

Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

Spoken word (в переводе с английского: произносимое слово) — форма литературного, а иногда и ораторского искусства, художественное выступление, в котором текст, стихи, истории, эссе больше говорятся, чем поются. Термин часто используется (особенно в англоязычных странах) для обозначения соответствующей CD-продукции, не являющейся музыкальной.

Формами «spoken word» могут быть как литературные чтения, чтения стихов и рассказов, доклады, так и поток сознания, и популярные в последнее время политические и социальные комментарии артистов в художественной или театральной форме. Нередко артистами в жанре «spoken word» бывают поэты и музыканты. Иногда голос сопровождается музыкой, но музыка в этом жанре совершенно необязательна.

Так же как и с музыкой, со «spoken word» выпускаются альбомы, видеорелизы, устраиваются живые выступления и турне.

Среди русскоязычных артистов в этом жанре можно отметить Дмитрия Гайдука и альбом Пожары, группы Сансара (Екб.) и рэп группу Marselle (L`One и Nel)

Некоторые представители жанра

(в алфавитном порядке)

- Бликса Баргельд

- Уильям Берроуз

- Бойд Райс

- Джелло Биафра

- GG Allin

- Дмитрий Гайдук

- Аллен Гинзберг

- Джек Керуак

- Лидия Ланч

- Евгений Гришковец

- Егор Летов

- Джим Моррисон

- Лу Рид

- Генри Роллинз

- Патти Смит

- Серж Танкян

- Том Уэйтс

- Дэвид Тибет

- Levi The Poet

- Listener

См. также

- Декламационный стих

- Мелодекламация

- Речитатив

- Художественное чтение

A good talk or public speech is like a good play, movie, or song.

It opens by arresting the listener’s attention, develops point by point, and then ends strongly.

The truth is, if you don’t know how to end a speech, the overall message won’t be persuasive and your key points may get lost.

The words you say at the beginning, and especially at the end of your talk, are usually the most persuasive parts of the speech and will be remembered longer than almost any other part of your speech.

Some of the great speeches in history and some of the most memorable Ted talks have ended with powerful, stirring words that live on in memory.

How do you end a speech and get the standing ovation that you deserve?

Keep reading to discover how…

Here are 9 tips and examples for concluding a speech.

1) Plan Your Closing Remarks Word for Word

To ensure that your conclusion is as powerful as it can be, you must plan it word for word.

Ask yourself, “What is the purpose of this talk?”

Your answer should involve the actions that you want your listeners to take after hearing you speak on this subject.

When you are clear about the end result you desire, it becomes much easier to design a conclusion that asks your listeners to take that action.

The best strategy for ending with a BANG is to plan your close before you plan the rest of your speech.

You then go back and design your opening so that it sets the stage for your conclusion.

The body of your talk is where you present your ideas and make your case for what you want the audience to think, remember, and do after hearing you speak.

2) Always End a Speech With a Call to Action

It is especially important to tell the audience what you want it to do as a result of hearing you speak.

A call to action is the best way to wrap up your talk with strength and power.

Here is a Speech Conclusion Call to Action Example

“We have great challenges and great opportunities, and with your help, we will meet them and make this next year the best year in our history!”

Whatever you say, imagine an exclamation point at the end. As you approach the conclusion, pick up your energy and tempo. This is even more important if the presentation you are giving is virtual.

Speak with strength and emphasis.

Drive the final point home.

Regardless of whether the audience participants agree with you or are willing to do what you ask, it should be perfectly clear to them what you are requesting.

3) End a Speech With a Summary

There is a simple formula for any talk:

- Tell them what you are going to tell them.

- Tell them.

- Then, tell them what you told them.

As you approach the end of your talk, say something like,

“Let me briefly restate these main points…”

You then list your key points, one by one, and repeat them to the audience, showing how each of them links to the other points.

Audiences appreciate a linear repetition of what they have just heard.

This makes it clear that you are coming to the end of your talk.

4) Close with a story

As you reach the end of your talk, you can say,

“Let me tell you a story that illustrates what I have been talking about…”

You then tell a brief story with a moral and then tell the audience what the moral is.

Don’t leave it to them to figure out for themselves.

Often you can close with a story that illustrates your key points and then clearly links to the key message that you are making with your speech.

To learn more about storytelling in speaking, you can read my previous blog post “8 Public Speaking Tips to Wow Your Audience.”

Here’s a recap of these 4 tips in a video…

Keep reading for the other 5 speech conclusion techniques.

5) Make Them Laugh

You can close with humor.

You can tell a joke that loops back into your subject and repeats the lesson or main point you are making with a story that makes everyone laugh.

During my talks on planning and persistence, I discuss the biggest enemy that we have, which is the tendency to follow the path of least resistance. I then tell this story.

Ole and Sven are out hunting in Minnesota and they shoot a deer. They begin dragging the deer back to the truck by the tail, but they keep slipping and losing both their grip and their balance.

A farmer comes along and asks them, “What are you boys doing?”

They reply, “We’re dragging the deer back to the truck.”

The farmer tells them, “You are not supposed to drag a deer by the tail. You’re supposed to drag the deer by the handles. They’re called antlers. You’re supposed to drag a deer by the antlers.”

Ole and Sven say, “Thank you very much for the idea.”

They begin pulling the deer by the antlers. After about five minutes, they are making rapid progress. Ole says to Sven, “Sven, the farmer was right. It goes a lot easier by the antlers.”

Sven replies, “Yeah, but we’re getting farther and farther from the truck.”

After the laughter dies down, I say…

“The majority of people in life are pulling the easy way, but they are getting further and further from the ‘truck’ or their real goals and objectives.”

That’s just one example of closing using humor.

6) Make It Rhyme

You can close with a poem.

There are many fine poems that contain messages that summarize the key points you want to make.

You can select a poem that is moving, dramatic, or emotional.

For years I ended seminars with the poem, “Don’t Quit,” or “Carry On!” by Robert W. Service. It was always well received by the audience.

7) Close With Inspiration

You can end a speech with something inspirational as well.

If you have given an uplifting talk, remember that hope is and has always been, the main religion of mankind.

People love to be motivated and inspired to be or do something different and better in the future.

Here are a few of my favorite inspirational quotes that can be tied into most speeches. You can also read this collection of leadership quotes for further inspiration.

Remember, everyone in your audience is dealing with problems, difficulties, challenges, disappointments, setbacks, and temporary failures.

For this reason, everyone appreciates a poem, quote or story of encouragement that gives them strength and courage.

Here are 7 Tips to Tell an Inspiring Poem or Story to End Your Speech

- You have to slow down and add emotion and drama to your words.

- Raise your voice on a key line of the poem, and then drop it when you’re saying something that is intimate and emotional.

- Pick up the tempo occasionally as you go through the story or poem, but them slow down on the most memorable parts.

- Especially, double the number of pauses you normally use in a conversation.

- Use dramatic pauses at the end of a line to allow the audience to digest the words and catch up with you.

- Smile if the line is funny, and be serious if the line is more thought-provoking or emotional.

- When you come to the end of your talk, be sure to bring your voice up on the last line, rather than letting it drop. Remember the “exclamation point” at the end.

Try practicing on this poem that I referenced above…

Read through “Carry On!” by Robert Service.

Identify the key lines, intimate parts, and memorable parts, and recite it.

Make it Clear That You’re Done

Make it Clear That You’re Done

When you say your final words, it should be clear to everyone that you have ended. There should be no ambiguity or confusion in the mind of your audience. The audience members should know that this is the end.

Many speakers just allow their talks to wind down.

They say something with filler words like, “Well, that just about covers it. Thank you.”

This isn’t a good idea…

It’s not powerful…

It’s not an authoritative ending and thus detracts from your credibility and influence.

When you have concluded, discipline yourself to stand perfectly still. Select a friendly face in the audience and look straight at that person.

If it is appropriate, smile warmly at that person to signal that your speech has come to an end.

Resist the temptation to:

- Shuffle papers.

- Fidget with your clothes or microphone.

- Move forward, backward, or sideways.

- Do anything else except stand solidly, like a tree.

9) Let Them Applaud

When you have finished your talk, the audience members will want to applaud…

What they need from you is a clear signal that now is the time to begin clapping.

How do you signal this?

Some people will recognize sooner than others that you have concluded your remarks.

In many cases, when you make your concluding comments and stop talking, the audience members will be completely silent.

They may be unsure whether you are finished.

They may be processing your final remarks and thinking them over. They may not know what to do until someone else does something.

In a few seconds, which will often feel like several minutes, people will applaud.

First one…

Then another…

Then the entire audience will begin clapping.

When someone begins to applaud, look directly at that person, smile, and mouth the words thank you.

As more and more people applaud, sweep slowly from person to person, nodding, smiling and saying, “Thank You.”

Eventually, the whole room will be clapping.

There’s no better reward for overcoming your fear of public speaking than enjoying a round of applause.

BONUS TIP: How to Handle a Standing Ovation

If you have given a moving talk and really connected with your audience, someone will stand up and applaud. When this happens, encourage others by looking directly at the clapper and saying, “Thank you.”

This will often prompt other members of the audience to stand.

As people see others standing, they will stand as well, applauding the whole time.

It is not uncommon for a speaker to conclude his or her remarks, stand silently, and have the entire audience sit silently in response.

Stand Comfortably and Shake Hands

But as the speaker stands there comfortably, waiting for the audience to realize the talk is over, one by one people will begin to applaud and often stand up one by one.

If the first row of audience members is close in front of you, step or lean forward and shake that person’s hand when one of them stands up to applaud.

When you shake hands with one person in the audience, many other people in the audience feel that you are shaking their hands and congratulating them as well.

They will then stand up and applaud.

Soon the whole room will be standing and applauding.

Whether you receive a standing ovation or not, if your introducer comes back on to thank you on behalf of the audience, smile and shake their hand warmly.

If it’s appropriate, give the introducer a hug of thanks, wave in a friendly way to the audience, and then move aside and give the introducer the stage.

Follow these tips to get that standing ovation every time.

Do you want to be your own boss, travel the world, and get paid for it? Discover how you can join one of the highest-paid professions in the world in this free online public speaking training.

Summary

Article Name

9 Tips to End a Speech With a Bang

Description

Brian Tracy explains how to end a speech to get the standing ovation that you deserve. Use his 9 tips to close your next speaking event with a bang.

Author

Brian Tracy

Publisher Name

Brian Tracy International

Publisher Logo

« Previous Post

8 Public Speaking Techniques to Wow Your Audience Next Post »

15 Ways to Start a Speech + Bonus Tips

About Brian Tracy — Brian is recognized as the top sales training and personal success authority in the world today. He has authored more than 60 books and has produced more than 500 audio and video learning programs on sales, management, business success and personal development, including worldwide bestseller The Psychology of Achievement. Brian’s goal is to help you achieve your personal and business goals faster and easier than you ever imagined. You can follow him on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Linkedin and Youtube.

Listener

Фото —

Иван Балашов

Listener стартовали в далеком 2002-м как хип-хоп-проект Дэна Смита. Со временем звучание ужесточилось до такой степени, что Смита позвали записывать гостевой вокал для металкорщиков The Chariot, а сама группа выступала на разогреве у The Dillinger Escape Plan на недавно прошедших в России концертах.

Инструментал у Listener довольно агрессивный, отдаёт кантри-мотивами, а безумные участники делают каждую песню не слёзным рассказом о несчастной любви, а эмоциональной декларацией лучшего друга в баре под очередную пинту пива.

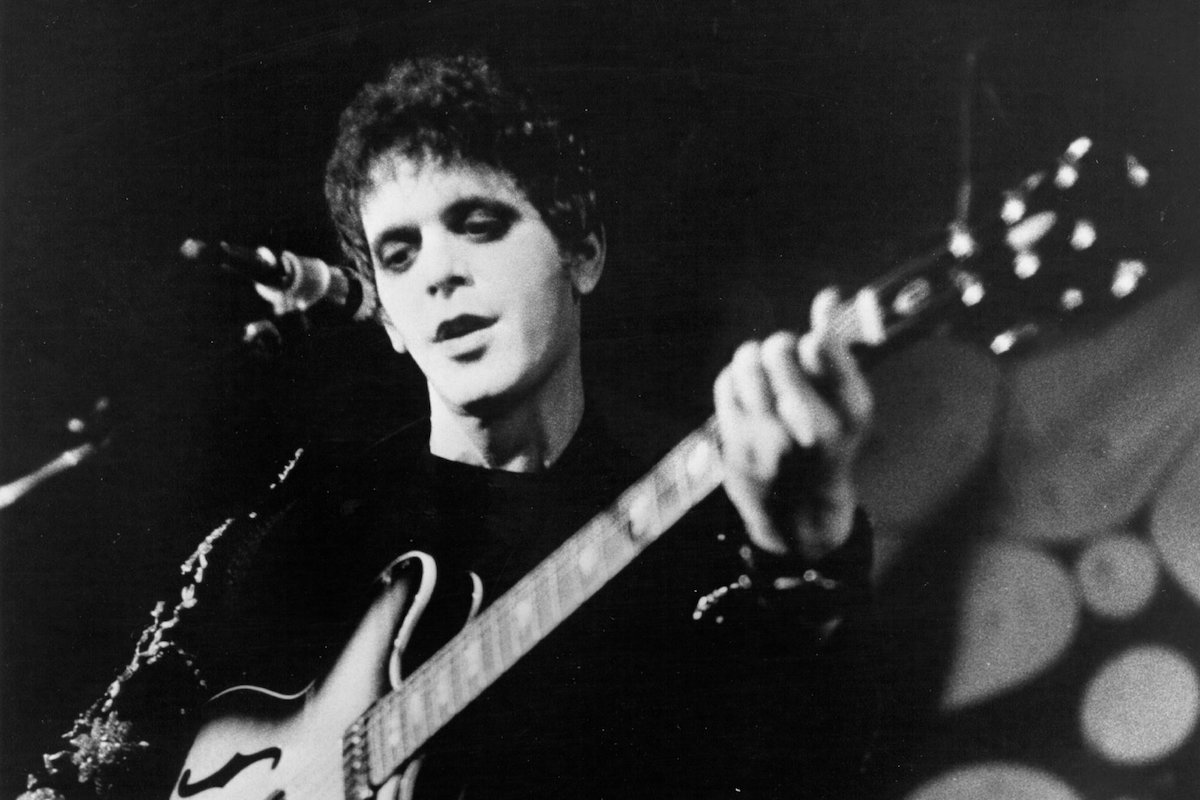

Лу Рид

Фото —

The Daily Beast

→

Лу Рид и его группа The Velvet Underground в своё время вдохновили невероятное количество музыкантов и тем самым повлияли на развитие рока. Например, о сильном влиянии Лу Рида на своё творчество говорил Дэвид Боуи.

Лу был в составе The Velvet Underground с 1964 по 1970 год, а после ухода из группы начал сольную карьеру. Он принял участие в песне Tranquilize группы The Killers, записал вместе с Gorillaz песню Plastic Beach и даже выпустил совместный альбом с Metallica!

Конечно, он выпускал и собственные альбомы. Наиболее необычный и несомненно заслуживающий внимания — The Raven, записанный в жанре spoken word. Главное в нём то, что он основан на рассказах Эдгара Аллана По. Так что скачивайте все 36 (!) песен, закрывайте глаза и погружайтесь в атмосферу.

Hotel Books

Фото —

Егор Зорин

→

Hotel Books обязательно понравятся любителям концептуализма. Кемерон Смит – единственный бессменный участник группы и её лицо – знает в этом толк. Например, песни July и August объединяет один общий клип, а для песни Lose One Friend существует своего рода парная композиция — Lose All Friends.

«Люди приходят и люди уходят. Некоторые приходят навестить, а другие просто потусить. И это моя книга поэм», — объясняет Кемерон название группы. Однако «люди приходят и люди уходят» — это не только про жизнь Смита, но и про саму группу. В последнем туре Hotel Books, например, за инструментал отвечали участники металкор-группы Convictions.

Дискография Hotel Books насчитывает уже 4 альбома, поэтому каждый сможет найти для себя новую любимую песню среди всего их разнообразия.

ДК

Фото —

Сергей Бабенко

→

ДК – советская группа, созданная в 1980 году. Название ей дал Сергей Жариков – создатель, идеолог и руководитель группы. ДК не стеснялись экспериментировать со звучанием и жанрами. Они первопроходцы российской экспериментальной музыки, творившие не только в жанре spoken word, но и авангарде, психоделическом роке, арт-панке, блюз-роке и еще множестве интересных жанров.

В 1984 году на Жарикова завели уголовное дело, а его группе, соответственно, запретили любые публичные выступления. Несомненно, это серьёзно сказалось на популярности ДК среди широких масс. Но всё же в музыкальных кругах они были группой известной и даже оказали сильное влияние на творчество Егора Летова (как на Гражданскую оборону, так и на проект Коммунизм), а также на группу Сектор Газа.

Canadian Softball

Фото —

Jarrod-Alonge

→

Canadian Softball – это вымышленная группа комика и музыканта Джаррода Алонжа, известного своими пародиями на рокеров и рок-группы. В 2015 году он выпустил альбом Beating a Dead Horse, в записи которого «участвовали» семь различных групп. На самом деле все семь групп были выдуманы комиком. Каждая группа пародировала определённый жанр. Звучание Canadian Softball, в частности, напоминало об эмо-группах поздних 1990-х — ранних 2000-х.

Состояла эта группа из самого Алонжа, вокалиста и гитариста, бассиста Уилла Грини и барабанщика/бэк-вокалиста Энди Конвэя. В альбоме у этой группы была только одна песня: The Distance Between You and Me is Longer Than the Title of this Song. Как видите, даже её название носит пародийный характер.

Позднее группа представила еще несколько песен, а 28 июля обещает выпустить альбом. В общем, дела у пародийной выдуманной группы идут даже лучше, чем у некоторых реально существующих артистов.

Make it Clear That You’re Done

Make it Clear That You’re Done