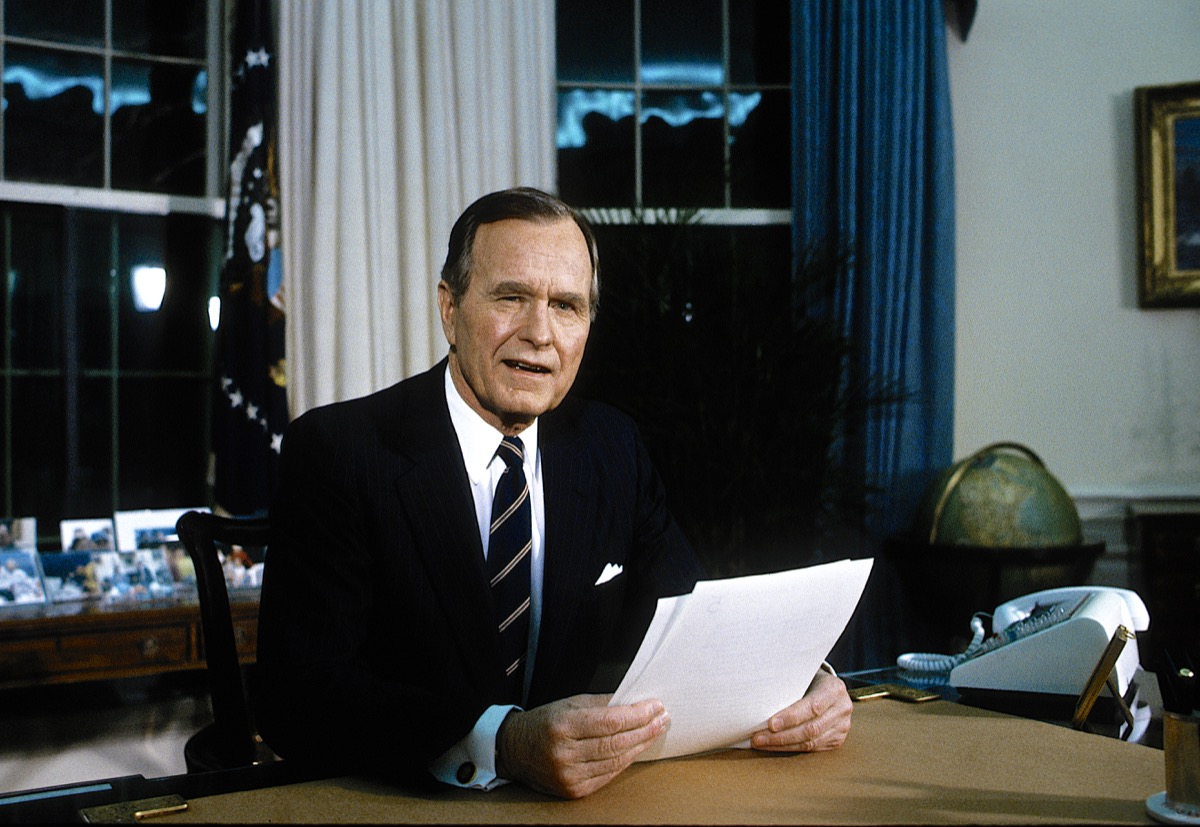

In the summer of 1990, as President George Bush was grappling with going to war in the Persian Gulf and Nelson Mandela was traveling the U.S. seeking support for the end of apartheid, a man named Allan Metcalf had an idea.

A professor of English at MacMurry College in Illinois, Metcalf has also been executive secretary of the American Dialect Society for more than 30 years. Because his duties include planning the annual get together for the word-obsessed academics who make up the Society’s membership, Metcalf was busy arranging logistics for that year’s meeting in Chicago.

The attendees are types who religiously scour everything from periodicals to the banter of their college students for neologisms, shifts in slang, new concepts or funny portmanteaus — linguistic changes that almost always reflect something bigger than themselves. Language is a mirror, Metcalf thought, so why not make something of a moment when all those people, who have been staring in the mirror all year, are in the same room?

“I was thinking, every year TIME Magazine chooses a person of the year, and they choose it not by some computer program but rather the editors and readers making suggestions about who was influential. Why couldn’t we choose a word of the year?” Metcalf says. “If anybody’s expert on what’s important in our language, that would be members of our group.”

The members of that group agreed and on Dec. 19, 1990, at the Barclay Hotel in Chicago, history was made. On that day, about 40 people selected bushlips as the New Word of The Year (a portmanteau of Bush and lips, the word was a little-known term for insincere political rhetoric, created to deride Bush’s failed promise, “Read my lips: no new taxes”). Of course, Metcalf was not necessarily the first human to ponder the notion of declaring a word of the year; a TIME reader wrote a letter back in 1945 suggesting that atomic hold that title. But today’s annual foam party for word-nerds, which has institutions throwing out selections from October through January, has roots in the St. Clair Room of the Barclay Hotel.

For the first decade or so, Metcalf says, the “WOTY” ritual—an acronym used by the growing band of linguists who watch for candidates like Ahab for white flukes—was a fairly small affair. That started changing when the American Dialect Society joined their meeting with the Linguistic Society of America’s in 2000, and again in 2003 when Merriam-Webster proclaimed its first WOTY to be democracy. Oxford University Press joined the parade in 2004, announcing that chav (a pejorative name for type of British youth) was their Word of the Year. Then, in 2010, Dictionary.com entered their own float with the simple, politically charged word change. Institutions with lower Q scores make the march too, like Collins English Dictionary (which chose photobomb as their word this year) and Chambers Dictionary (which selected overshare).

As close readers may have noticed, the ritual has not only exploded but also shed a tricky qualification since its inception in 1990. In the beginning, the American Dialect Society decreed that any nominee had to be new. That rule proved flawed over the years, as attendees would pluck a new word from the masses only to find out it wasn’t actually new at all (Not!, 1992’s selection, was eventually dated back to the 1800s) or that, like bushlips, the term was a passing thing that should have been wrapped in the next day’s newspaper rather than put on a pedestal.

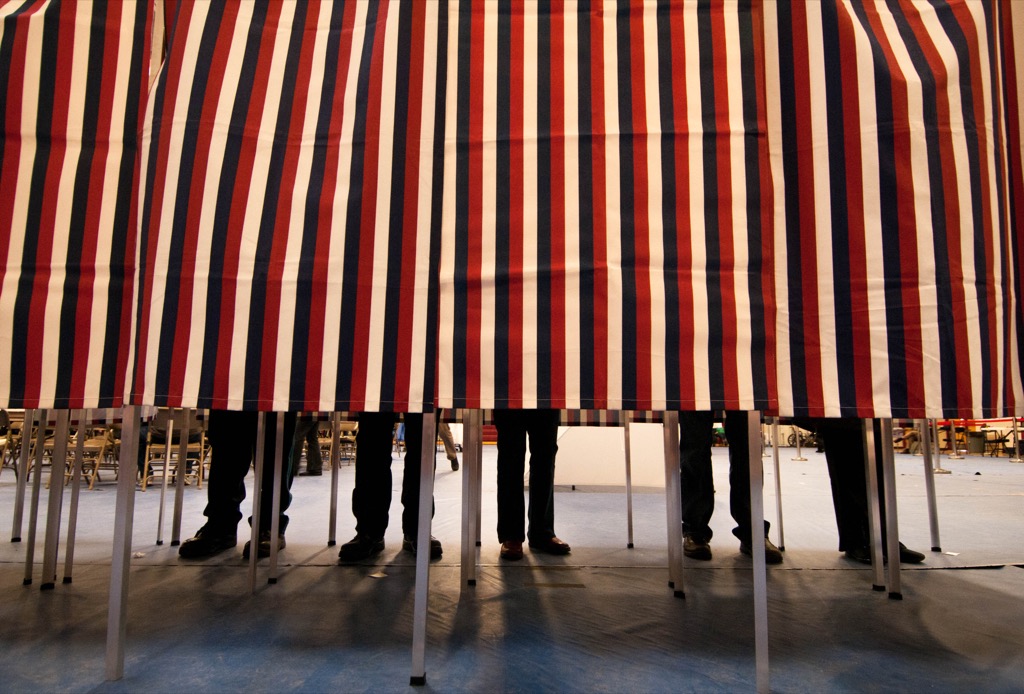

By the 1990s, that rule had been dropped, freeing the Society’s members to select words like mom in 1996 (as a nod to the “soccer mom” voter who emerged as a key demographic in that year’s election) and occupy in 2011, recording a year in which a movement against classism took to the streets around the world. It also led to Metcalf penning a book, Predicting New Words, in which is presented his “FUDGE” system for identifying words with staying power.

Institutions have found ways to distinguish their selections amidst the delightful frenzy. Merriam-Webster relies largely on spikes in lookups, rather than making editorial choices, which is why they often end up choosing less-trendy words like last year’s science—a word, as Editor-at-Large Peter Sokolowski said, “lurking behind” big headlines. The people at Oxford University Press, which is monitoring English from South Texas to South Africa, position themselves as thinking more internationally and have often selected one WOTY for the U.S. and another for the U.K., like 2012’s GIF and omnishambles. And Dictionary.com, while taking lookups into account, looks to the news stories of the year and searches for a term that can serve as connective tissue.

Then there remains the American Dialect Society, which exists to study the English of North America—the only outlet to have a public, live vote that will count the hands of anyone who shows up (not just members of the Society), which now entails funneling hundreds into a room where people make nominations and give speeches for or against candidates. It’s a real good time, Metcalf says, which is just what he hoped for in the summer of 1990. “The main thing was I thought it would be fun,” he says. And now, he notes, since their vote happens in January, they’re typically the last to make their choice. “We like to think that we were first and we are the last,” he says.

For every institution, there’s an element of free publicity, sought or not, that comes with announcing a word of the year, a line that will hook reporters (this writer included) every single time. But that’s not just because WOTYs are clickbait. It’s a moment, as Oxford’s Casper Grathwohl says, to remind people that lexicographers are working hard, all year long, to catalog the immense historical record that is our language. And words of the year are a little bit of poetry that come out of a pithy tradition of reflection, regardless of whether, when we have the benefit of hindsight, the selections prove to have bottled up the zeitgeist of a year or mostly hot air.

“There are a lot of windows into thinking about where we are as a society,” Grathwohl says. “Coded in the language we use is a lot of information that we are communicating without directly saying it … When we select the word of the year, it allows people to dig underneath the surface of the words we use to think about what’s there.”

Read about Oxford’s 2014 Word of the Year: Vape

Contact us at letters@time.com.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The word(s) of the year, sometimes capitalized as «Word(s) of the Year» and abbreviated «WOTY» (or «WotY«), refers to any of various assessments as to the most important word(s) or expression(s) in the public sphere during a specific year.

The German tradition, Wort des Jahres was started in 1971. The American Dialect Society’s Word of the Year is the oldest English-language version, and the only one that is announced after the end of the calendar year, determined by a vote of independent linguists, and not tied to commercial interest.[citation needed] However, various other organizations also announce Words of the Year for a variety of purposes.

American Dialect Society[edit]

Since 1990, the American Dialect Society (ADS) has designated one or more words or terms to be the «Word of the Year» in the United States.

List of American Dialect Society’s Words of the Year

In addition to the «Word of the Year», the society also selects words in other categories that vary from year to year. These categories have occurred in several years:

- Most useful

- Most creative

- Most unnecessary

- Most outrageous

- Most euphemistic

- Most likely to succeed

- Least likely to succeed

Australian National Dictionary Centre[edit]

The Australian National Dictionary Centre has announced a Word of the Year each since 2006. The word is chosen by the editorial staff, and is selected on the basis of having come to some prominence in the Australian social and cultural landscape during the year.[1] The Word of the Year is often reported in the media as being Australia’s word of the year,[2][3] but the word is not always an Australian word.

| Year | Word |

|---|---|

| 2006 | podcast |

| 2007 | me-tooism |

| 2008 | GFC |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | vuvuzela |

| 2011 | |

| 2012 | green-on-blue |

| 2013 | bitcoin |

| 2014 | shirtfront |

| 2015 | sharing economy |

| 2016 | democracy sausage |

| 2017 | Kwaussie |

| 2018 | Canberra bubble |

| 2019 | Voice |

| 2020 | iso |

| 2021 | strollout |

| 2022 | teal |

Cambridge Dictionary[edit]

The Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year, by Cambridge University Press & Assessment, has been published every year since 2015.[4]

The Cambridge Word of the Year is led by the data — what users look up — in the world’s most popular dictionary for English language learners[5].

In 2022, the Cambridge Word of the Year was ‘homer’, caused by Wordle players looking up five-letter words, especially those that non-American players were less familiar with.[6]

In 2021, the Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year was ‘perseverance’.[7] In 2020, ‘quarantine’.[8]

| YEAR | |

|---|---|

| 2015 | austerity |

| 2016 | paranoid |

| 2017 | populism |

| 2018 | nomophobia |

| 2019 | upcycling |

| 2020 | quarantine |

| 2021 | perserverance |

| 2022 | homer |

Collins English Dictionary[edit]

The Collins English Dictionary has announced a Word of the Year every year since 2013, and prior to this, announced a new ‘word of the month’ each month in 2012. Published in Glasgow, UK, Collins English Dictionary has been publishing English dictionaries since 1819.[9]

Toward the end of each calendar year, Collins release a shortlist of notable words or those that have come to prominence in the previous 12 months. The shortlist typically comprises ten words, though in 2014 only four words were announced as the Word of the Year shortlist.

The Collins Words of the Year are selected by the Collins Dictionary team across Glasgow and London, consisting of lexicographers, editorial, marketing, and publicity staff, though previously the selection process has been open to the public.

Whilst the word is not required to be new to feature, the appearance of words in the list is often supported by usage statistics and cross-reference against Collins’ extensive corpus to understand how language may have changed or developed in the previous year. The Collins Word of the Year is also not restricted to UK language usage, and words are often chosen that apply internationally as well, for example, fake news in 2017.[10]

| Year | Word of the Year | Definition | Shortlist | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Geek[11] | If you call someone, usually a man or boy, a geek, you are saying in an unkind way that they are stupid, awkward, or weak.[12] |

|

||

| 2014 | Photobomb[24] | If you photobomb someone, you spoil a photograph of them by stepping in front of them as the photograph is taken, often doing something silly such as making a funny face.[25] |

|

||

| 2015 | Binge-watch[30] | If you binge-watch a television series, you watch several episodes one after another in a short time.[31] |

|

||

| 2016 | Brexit[33] | The withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union in January 2020.[34] |

|

||

| 2017 | Fake news[44] | False, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting.[45] |

|

||

| 2018 | Single-use[55] | Made to be used once only.[56] |

|

||

| 2019 | Climate strike[58] | A form of protest in which people absent themselves from education or work to join demonstrations demanding action to counter climate change.[59] |

|

||

| 2020 | Lockdown[58] | If there is a lockdown, people must stay at home unless they need to go out for certain reasons, such as going to work, buying food or taking exercise. |

|

||

| 2021 | NFT[71] | A digital certificate of ownership of a unique asset, such as an artwork or a collectible. |

|

||

| 2022 | Permacrisis[72] | An extended period of instability and insecurity, esp one resulting from a series of catastrophic events. |

Macquarie Dictionary[edit]

The Macquarie Dictionary, which is the dictionary of Australian English, updates the online dictionary each year with new words, phrases, and definitions. These can be viewed on their website.[73]

Each year the editors select a short-list of new words added to the dictionary and invite the public to vote on their favourite. The public vote is held in January and results in the People’s Choice winner. The most influential word of the year is also selected by the Word of the Year Committee which is chaired by the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney, Dr Michael Spence. The Editor of the Macquarie Dictionary, Susan Butler, is also a committee member. The Committee meets annually to select the overall winning words.

The following is the list of winning words since the Macquarie Word of the Year first began in 2006:

| Year | Committee’s Choice | People’s Choice |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | muffin top | (No overall winner. See Macquarie website for category winners) |

| 2007 | pod slurping | password fatigue |

| 2008 | toxic debt | flashpacker |

| 2009 | shovel ready | tweet |

| 2010 | googleganger | shockumentary |

| 2011 | burqini | fracking |

| 2012 | phantom vibration syndrome | First World problem |

| 2013 | infovore[74] | onesie |

| 2014 | mansplain[75] | shareplate |

| 2015 | captain’s call[76] | captain’s call[77] |

| 2016 | fake news | halal snack pack |

| 2017 | milkshake duck[78][79] | framily[80] |

| 2018 | me too[81][82] | single-use[83] |

| 2019 | cancel culture | robodebt |

| 2020 | doomscrolling, rona | Karen |

| 2021 | strollout[84] | strollout |

| 2022 | teal | bachelor’s handbag[85] |

Merriam-Webster[edit]

The lists of Merriam-Webster’s Words of the Year (for each year) are ten-word lists published annually by the American dictionary-publishing company Merriam-Webster, Inc., which feature the ten words of the year from the English language. These word lists started in 2003 and have been published at the end of each year. At first, Merriam-Webster determined its contents by analyzing page hits and popular searches on its website. Since 2006, the list has been determined by an online poll and by suggestions from visitors to the website.[86]

The following is the list of words that became Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year since 2003:[87]

- 2003: democracy

- 2004: blog

- 2005: integrity

- 2006: truthiness

- 2007: w00t

- 2008: bailout

- 2009: admonish

- 2010: austerity

- 2011: pragmatic

- 2012: socialism and capitalism

- 2013: science

- 2014: culture

- 2015: -ism

- 2016: surreal

- 2017: feminism[88]

- 2018: justice

- 2019: they

- 2020: pandemic[89]

- 2021: vaccine[90]

- 2022: gaslighting

Oxford[edit]

Oxford University Press, which publishes the Oxford English Dictionary and many other dictionaries, announces an Oxford Dictionaries UK Word of the Year and an Oxford Dictionaries US Word of the Year; sometimes these are the same word. The Word of the Year need not have been coined within the past twelve months but it does need to have become prominent or notable during that time. There is no guarantee that the Word of the Year will be included in any Oxford dictionary. The Oxford Dictionaries Words of the Year are selected by editorial staff from each of the Oxford dictionaries. The selection team is made up of lexicographers and consultants to the dictionary team, and editorial, marketing, and publicity staff.[91]

| Year | UK Word of the Year | US Word of the Year | Hindi Word of the Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | chav | ||

| 2005 | sudoku | podcast | |

| 2006 | bovvered | carbon-neutral | |

| 2007 | carbon footprint | locavore | |

| 2008 | credit crunch | hypermiling | |

| 2009 | simples (Compare the Meerkat catchphrase) | unfriend | |

| 2010 | big society | refudiate | |

| 2011 | squeezed middle | ||

| 2012 | omnishambles | GIF (noun) | |

| 2013 | selfie[92] | ||

| 2014 | vape[93] | ||

| 2015 | 😂 (Face With Tears of Joy, Unicode: U+1F602, part of emoji)[94] | ||

| 2016 | post-truth[95] | ||

| 2017 | youthquake[96] | Aadhaar[a] | |

| 2018 | toxic[98] | Nari Shakti or Women Power[99] | |

| 2019 | climate emergency[100] | Samvidhaan or Constitution[101] | |

| 2020 | No single word chosen[102] | Aatmanirbharta or Self-Reliance[103] | |

| 2021 | vax[104] | ||

| 2022 | goblin mode[105][106] |

Grant Barrett[edit]

Since 2004, lexicographer Grant Barrett has published a words-of-the-year list, usually in The New York Times, though he does not name a winner.

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013 in New York Times, also a more complete list

- 2014 in Dallas Morning News

Dictionary.com[edit]

In 2010, Dictionary.com announced its first word of the year, ‘change’, and has done so in December every year since.[107] The selection is based on search trends on the site throughout the year and the news events that drive them.[108]

The following is the list of annual words since beginning with the first in 2010:[107]

- 2010: Change

- 2011: Tergiversate

- 2012: Bluster

- 2013: Privacy

- 2014: Exposure

- 2015: Identity

- 2016: Xenophobia

- 2017: Complicit

- 2018: Misinformation

- 2019: Existential[109]

- 2020: Pandemic

- 2021: Allyship

- 2022: Woman

Similar word lists[edit]

A Word a Year[edit]

Since 2004, Susie Dent, an English lexicographer has published a column, «A Word a Year», in which she chooses a single word from each of the last 101 years to represent preoccupations of the time. Susie Dent notes that the list is subjective.[110][111][112] Each year, she gives a completely different set of words.

Since Susie Dent works for the Oxford University Press, her words of choice are often incorrectly referred to as «Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year».

Other countries[edit]

In Germany, a Wort des Jahres has been selected since 1972 (for year 1971) by the Society of the German Language.[113] In addition, an Unwort des Jahres (Un-word of the year or No-no Word of the Year) has been nominated since 1991, for a word or phrase in public speech deemed insulting or socially inappropriate (such as «Überfremdung»).[114] Similar selections are made each year since 1999 in Austria, 2002 in Liechtenstein, and 2003 in Switzerland. Since 2008, language publisher Langenscheidt supports a search for the German youth word of the year, which aims to find new words entering the language through the vernacular of young people.[115][116]

In Denmark, the Word of the year has been selected since 2008 by Danmarks Radio and Dansk Sprognævn.

In Japan, the Kanji of the year (kotoshi no kanji) has been selected since 1995. Kanji are adopted Chinese characters in Japanese language. Japan also runs an annual word of the year contest called » U-Can New and Trendy Word Grand Prix» (U-Can shingo, ryūkōgo taishō) sponsored by Jiyu Kokuminsha. Both the kanji and word/phrases of the year are often reflective of Japanese current events and attitudes. For example, in 2011 following the Fukushima power plant disaster, the frustratingly enigmatic phrase used by Japanese officials before the explosion regarding the possibility of meltdown – «the possibility of recriticality is not zero» (Sairinkai no kanōsei zero de wa nai) – became the top phrase of the year. In the same year, the kanji indicating ‘bond’ (i.e. familial bond or friendship) became the kanji of the year, expressing the importance of collectiveness in the face of disaster.[117]

In Norway, the Word of the year poll is carried out since 2012.

In Portugal, the Word of the year poll is carried out since 2009.

In Russia, the Word of the year poll is carried out since 2007.

In Spain, the Word of the year is carried out by Fundéu since 2013.

In Ukraine, the Word of the year poll is carried out since 2013.

See also[edit]

- Language Report from Oxford University Press

- Lists of Merriam-Webster’s Words of the Year

- Neologism

- Doublespeak Award

- Kanji of the year

Further reading[edit]

- John Ayto, «A Century of New Words», Series: Oxford Paperback Reference (2007) ISBN 0-19-921369-0

- John Ayto, «Twentieth Century Words», Oxford University Press (1999) ISBN 0-19-860230-8

Notes[edit]

- ^ First Hindi Word of the Year[97]

References[edit]

- ^ «Australian National Dictionary Centre’s Word of the Year 2016 | Ozwords». ozwords.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ «What exactly is a democracy sausage?». BBC News. December 14, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ «‘Shirtfront’ named Australia’s word of the year». ABC News. December 10, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ https://dictionary.cambridge.org/editorial/woty

- ^ «Cambridge Dictionary’s word of the year will be a sore spot for Wordle fans».

- ^ «Wordle frustration inspires Cambridge Dictionary’s word of the year». November 17, 2022.

- ^ «‘Perseverance’ named Cambridge Dictionary’s word of the year». Independent.co.uk. November 17, 2021.

- ^ «Cambridge Dictionary’s Word of the Year is ‘quarantine’«. The Times of India.

- ^ «Collins English Dictionary | Definitions, Translations and Pronunciations». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Collins Dictionary (November 1, 2017), Collins Dictionary announce their 2017 Word of the Year, archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved October 11, 2018

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (December 16, 2013). «Geek deemed word of the year by the Collins online dictionary». the Guardian. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Geek definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2013 is… – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «And the Collins English Dictionary word of the year is…» The Irish Times. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Photobomb definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ reporters, Telegraph (October 23, 2014). «‘Words of Year 2014’ announced». The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ reporters, Telegraph (October 23, 2014). «‘Words of Year 2014’ announced». The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ reporters, Telegraph (October 23, 2014). «‘Words of Year 2014’ announced». The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ reporters, Telegraph (October 23, 2014). «‘Words of Year 2014’ announced». The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Binge-watch: Collins’ Word of the Year». BBC News. November 5, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Binge-watch definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 5, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «‘Brexit’ is Collins’ Word of the Year 2016 | The Bookseller». www.thebookseller.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Brexit definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Top 10 Collins Words of the Year 2016 – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Fake news is officially 2017’s word of the year». The Independent. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Fake news definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ «Collins 2017 Word of the Year Shortlist – New on the blog – Word Lover’s blog – Collins Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «Collins Dictionary 2018 word of the year revealed». The Irish Times. November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ «Definition of ‘single-use’«. Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Quin, Rachel (November 7, 2018). «Collins 2018 Word of the Year Shortlist». Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ a b «Collins — the Collins Word of the Year 2020 is».

- ^ «Climate strike definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ «Collins Word of the Year 2019 shortlist». November 7, 2019.

- ^ «Lockdown definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Coronavirus definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «BLM definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Keyworker definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Furlough definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Self-isolate definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Social distancing definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Megxit definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «TikToker definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Mukbang definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary».

- ^ «Get your crypto at the ready: NFTs are big in 2021». Collins Dictionary Language Blog. November 24, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ susanwright (November 1, 2022). «A year of ‘permacrisis’«. Collins Dictionary Language Blog. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year

- ^ «The Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year is …» The Conversation. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ «Macquarie Dictionary words of the year: ‘mansplain’ and ‘share plate’«. The Sydney Morning Herald. February 5, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ «Tony Abbott’s lexical legacy: Captain’s call is 2015 Word of the Year». The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ «Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year». Macquarie Dictionary. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Webb, Tiger (January 15, 2018). «Why ‘milkshake duck’ is the perfect choice for word of the year». ABC News. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ «The Committee’s Choice for Word of the Year 2017 goes to…» Macquarie Dictionary. January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ «Committee’s Choice and People’s Choice announced!». Macquarie Dictionary. January 23, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ Webb, Tiger (January 15, 2019). «Macquarie Dictionary word of the year goes to ‘me too’, in a year filled with digital uncertainty». ABC News. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ «The Committee’s Choice for Word of the Year 2018 goes to…» Macquarie Dictionary. January 15, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ «Committee’s Choice and People’s Choice announced!». Macquarie Dictionary. December 19, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ «Strollout chosen as Macquarie dictionary’s 2021 word of the year». the Guardian. November 29, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ «Australia’s word of the year has been revealed». SBS News. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ «Merriam-Webster launches ‘Word of the Year’ online poll». CNET. November 27, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ «Word of the Year Archive». Merriam-Webster. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ Criss, Doug. «Merriam-Webster’s word of the year for 2017 is ‘feminism’«. CNN. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Andrew, Scottie. «‘Pandemic’ is, unsurprisingly, the Word of the Year for Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com». CNN. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Sheidlower, Noah; Zdanowicz, Christina (November 29, 2021). «It’s a beacon of hope and it’s a politicized issue. Merriam Webster’s 2021 word of the year is …» CNN. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year: Frequently Asked Questions (viewed November 20, 2013).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is… (viewed November 20, 2013).

- ^ Grisham, Lori (November 18, 2014). «Oxford names ‘vape’ 2014 Word of the Year». USA Today. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ «Word of the Year 2015». Oxford Dictionaries. November 16, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ «Word of the Year 2016 is… | Oxford Dictionaries». Oxford Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ «Oxford Word of the Year 2017». Oxford Languages. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ Gohain, Manash Pratim (January 28, 2018). «‘Aadhaar’ is Oxford’s first Hindi word of the year». The Times of India. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ «Toxic: Oxford Dictionaries sums up the mood of 2018 with word of the year». CNN. November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ «Nari Shakti Is Oxford Dictionary’s Hindi Word Of The Year 2018». The Indian Express. January 27, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Zhou, Naaman (November 20, 2019). «Oxford Dictionaries declares ‘climate emergency’ the word of 2019». The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. «Climate emergency» was named word of the year.

- ^ «Oxford Hindi Word of the Year 2019 is Samvidhaan». India Today. January 28, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Words of an Unprecedented Year (PDF), Oxford University Press, November 20, 2020, retrieved December 8, 2020

- «Oxford Word of the Year 2020». Oxford University Press.

- ^ «Oxford Hindi Word of the Year 2020 | Oxford Languages». languages.oup.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

The Oxford Hindi Word of the Year 2020 is… Aatmanirbharta or Self-Reliance.

- ^ «‘Vax’ Chosen as Word of the Year by Oxford — November 1, 2021″. Daily News Brief. November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ James, Imogen (December 5, 2022). «Oxford word of the year 2022 revealed as ‘goblin mode’«. BBC News. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ «Oxford Word of the Year 2022». Oxford Languages. Oxford University Press. 2022. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b «What Dictionary.com’s words of the year say about us». cnn. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ «Existential’ crowned word of the year by Dictionary.com». Click on Detroit. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ «‘Existential’ is Dictionary.com’s Word Of the Year». CBS News. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ A Word a Year: 1906–2006

- ^ A Word a Year: 1905–2005[dead link]

- ^ A Word a Year: 1904–2004[dead link]

- ^ German Word of the Year

- ^ «Unword of the year» in Germany

- ^ «This is the German youth word of the year for 2020». The Local Germany. October 15, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ «The word of the year (whether we like it or not)». The Spectator. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Laura (2017). «Japan’s trendy Word Grand Prix and Kanji of the Year: Commodified language forms in multiple contexts». Language and Materiality: Ethnographic and Theoretical Explorations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–28.

External links[edit]

- Top words from 2000 – present @ Global Language Monitor

- Word of the Year Archive @ Macquarie Dictionary

- Word of the Year Archive @ Merriam-Webster

- Word of the Year Archive @ OxfordWords blog

- Austrian Word of the Year

- Canadian Word of the Year

- Liechtenstein Word of the Year

- Switzerland Word of the Year

- Dictionary.com word of the year @ Dictionary.com

The Oxford Dictionary published their “Word Of The Year” 2016, and it is post-truth. If you want to find out why this word made the cut, check out their article.

Now that we know the “Word of 2016”, however, lets have a look at the whole tradition of “Word of the Year”. We will answer some questions you may have about it and provide you with the answers. Furthermore, we have looked a bit at the history of this sometimes infamous award and broke it down into easy to digest bits for you. And, of course, you will find a list of all “Words of the Year” from the first accolade til today.

The Word Of The Year

What Is “Word Of The Year”?

“Word of the Year” is a symbolic award given by several institutions (like the Oxford Dictionary) to words that had a special impact in the year they were chosen. Taken into account are not only single words but also expressions that were of some importance in the public sphere throughout the year in question.

When Did It Start?

In Germany, the tradition of crowning a “Wort des Jahres” started back in 1971. The first one determined for the English language, chosen by the American Dialect Society, was in 1990.

Who Announces The Word Of The Year?

For the English language, the aforementioned America’s Dialect Society officially announces the “Word of the Year” after the calendar year ended. However, several dictionaries also started publishing their very own “Word of the Year”. Such as:

- Oxford English Dictionary started in 2004

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary started in 2003

- Macquarie Dictionary started in 2006

Different from the dictionaries listed above, the official “Word of the Year” of the American Dialect Society is chosen via voting among several renowned and independent linguists.

What Are The Different Categories?

In addition to the overall “Word of the Year”, the American Dialect Society also selects words for this award in different categories. These categories vary throughout the years. Some of them include, most…

- useful

- creative

- unnecessary

- notable hashtag

… and more.

List Of All Words Of The Year For The English Language

Here are all words that have been given this award by the four sources mentioned above. Please note that the choice for 2016 by the American Dialect Society hasn’t been made yet.

| Year | American Dialect Society | Merriam-Webster Dictionary | Oxford English Dictionary UK vs. US |

Macquarie Dictionary committee vs. people’s choice |

| 2016 | tba | surreal | post-truth | tba |

| 2015 | Singluar they | -ism | ? | captain’s call |

| 2014 | #blacklivesmatter | culture | vape | mansplain vs. shareplate |

| 2013 | because (as in because awesome, because reasons) | science | selfie | infovorce vs. onsie |

| 2012 | hashtag | socialism, capitalism | omnishambles vs to GIF | phantom vibration syndrom vs. First World Problem |

| 2011 | occupy | pragmatic | squeezed middle | burqini vs. fracking |

| 2010 | app | austerity | big society vs. refudiate | googleganger vs. shockumentary |

| 2009 | tweet | admonish | simples vs. unfriend | shovel-ready vs. tweet |

| 2008 | bailout | bailout | credit crunch vs. hypermiling | toxic debt vs. flashpacker |

| 2007 | subprime | w00t | carbon footprint vs. locavore | pod slurping vs. password fatigue |

| 2006 | plutoed | thruthiness | bovvered vs. carbon-neutral | muffin top |

| 2005 | truthiness | integrity | sudoku vs. podcast | |

| 2004 | red | state, blue state, purple state | blog | chav |

| 2003 | metrosexual | democracy | ||

| 2002 | weapons of mass destruction (WMD) | |||

| 2001 | 9-11 | |||

| 2000 | chad | |||

| 1999 | Y2K | |||

| 1998 | e- (as in e-mail, e-commerce) | |||

| 1997 | millennium bug | |||

| 1996 | mom | |||

| 1995 | web, to newt | |||

| 1994 | cyber, morph | |||

| 1993 | information superhighway | |||

| 1992 | Not! | |||

| 1991 | mother of all | |||

| 1990 | bushlips |

Самое важное слово или выражение в общественной сфере в течение определенного года

Слово ( s) года, иногда с заглавной буквы как «Слово (я) года » и сокращенно «WOTY » (или «WotY »), относится к любой из различных оценок наиболее важных слов или выражений в публичной сфере в течение определенного года.

Немецкая традиция, Wort des Jahres, была начата в 1971 году. Слово года Американского диалектного общества является старейшей англоязычной версией, а только один, который объявляется после окончания календарного года, определяемого голосованием независимых лингвистов и не привязанного к коммерческим интересам. Однако различные другие организации также объявляют «Слова года» для различных целей.

Содержание

- 1 Американское диалектное общество

- 1.1 Выбор

- 1.2 Категории

- 1.2.1 Самые полезные

- 1.2.2 Самые креативные

- 1.2.3 Самые ненужные

- 1.2. 4 Наиболее возмутительное

- 1.2.5 Наиболее эвфемистическое

- 1.2.6 С наибольшей вероятностью успеха

- 1.2.7 Наименьшее вероятность успеха

- 1.2.8 Особые категории

- 2 Австралийский национальный словарь-центр

- 3 Collins English Dictionary

- 4 Macquarie Dictionary

- 5 Merriam-Webster

- 6 Oxford

- 7 Grant Barrett

- 8 Dictionary.com

- 9 Списки похожих слов

- 9.1 Одно слово в год

- 9.2 Другие страны

- 10 См. Также

- 11 Дополнительная литература

- 12 Ссылки

- 13 Внешние ссылки

Американское общество диалектов

С 1991 года американский диалект Общество (ADS) определило одно или несколько слов или терминов как «Слово года» в США

|

|

В конце каждого десятилетия общество также выбирает a Word of the Decade : web для 1990-х, google (как глагол) для 2000-х, и в единственном числе они для 2010-х. В 2000 году джаз был выбран как «Слово 20 века», а она — как «Слово прошлого тысячелетия».

Выбор

Среди других кандидатов на «Слово года»:

- 2006: Плутоновый ритм «климатическая канарейка » (то, что плохо со здоровьем указывает на надвигающуюся экологическую катастрофу) во втором туре голосования за слово 2006 года. В числе других слов были порка (реклама, замаскированная под блог или веб-журнал), The Decider (политическая фраза, произнесенная бывшим президентом США Джорджем Бушем), «запрещенные жидкости» (жидкости, которые не могут перевозиться пассажирами в самолетах), и макака (американский гражданин, рассматриваемый как иностранец)

- 2007: Среди претендентов были зеленые- (обозначение экологической проблемы, как в greenwashing ), всплеск (увеличение численности войск в зоне боевых действий, как в иракской войне 2007 года ), Facebook (все части речи), погружение в воду (метод допроса, при котором субъекта обездвиживают и обливают водой для имитации утопления), Googlegänger (портмоне из Google и Doppelgänger, что означает лицо с вашим именем, которое появляется, когда вы сами гуглите), и широкая позиция, «иметь -» (лицемерить или выражать две противоречивые точки зрения в отношении сенатора Ларри Крейг после ареста 2007 года в аэропорту)

- 2010: Ном проиграл во втором туре с приложением

- 2011: 99%, 99 процентов и аббревиатура FoMO (Страх пропустить ) проиграл во втором туре с занятием

- 2012: Другими кандидатами были YOLO (аббревиатура от «You Only Live Once», часто используется саркастически или самоуничижительно), фискальный обрыв (угроза сокращения расходов и повышения налогов, нависшая над переговорами по бюджету на конец года), стиль Каннам (модный стиль Сеула район Каннамгу, как используется в корейской поп-песне с тем же названием ), равенство в браке (юридическое признание однополых браков) и 47 процентов (заявленная часть населения, которая не платит федеральный подоходный налог).

- 2013: косая черта: используется в качестве координирующего союза для обозначения «и / или» (например, «приехать и посетить косая черта, оставайся «) или» так «(» Я люблю это место, косая черта, мы можем туда пойти? «), тверк : режим танца, который включает энергичную попку- тряска и толкание ягодиц, обычно с опущенными ногами, Obamacare : термин для Закона о доступном медицинском обслуживании, который перешел от уничижительного до прозаического, а селфи : сделана фотография самого себя, как правило, с помощью смартфона и размещенного в социальных сетях.

- 2014: bae: возлюбленный или романтический партнер, columbusing : культурное присвоение, особенно акт белого человека, утверждающего, что открыл вещи, уже известные культурам меньшинств, даже: иметь дело или примирять сложные ситуации или эмоции (от «Я даже не могу»), человеческое распространение : человека, сидящего широко расставленными ногами в общественном транспорте в способ, который блокирует другие места.

Категории

В дополнение к «Слову года» общество также выбирает слова из других категорий, которые меняются из года в год:

Большинство полезный

- 2008:Барак Обама (в частности, использование обоих имен как объединяющих форм, таких как ObamaMania или Obamacare )

- 2009: фаи l (существительное или междометие, используемое, когда что-то явно неудачно)

- 2010: nom (звукоподражание форма, имеющая значение для еды, особенно. приятно)

- 2011: humblebrag (выражение ложного смирения, особенно знаменитостей в Твиттере)

- 2012: — (po) calypse, — (ma) geddon (гиперболическое комбинирование форм различных катастроф)

- 2013: из-за введения существительного, прилагательного или другой части речи (например, «потому что причины», «потому что потрясающе»).

- 2014 : даже (иметь дело или примирять сложные ситуации или эмоции, из «Я даже не могу»)

- 2015: они (гендерно-нейтральное местоимение единственного числа для известного человека, особенно как небинарный идентификатор)

- 2016: газлайт (психологически манипулировать человеком, чтобы поставить под сомнение его собственное здравомыслие)

- 2017: умереть в результате самоубийства (вариант «совершить самоубийство», который не предполагает преступного деяния)

Самый креативный

- 2008: Зона рекомбинации: зона в Международном аэропорту им. Генерала Митчелла, в которой пассажиры, прошедшие досмотр, могут привести в порядок свою одежду и вещи.

- 2009: Дракула чихание: прикрывать рот согнутым локтем во время чихания, что похоже на популярные изображения вампира Дракулы, в которых он прячет нижнюю половину лица плащом.

- 2010: prehab: превентивный запись в реабилитационный центр для предотвращения рецидива проблемы жестокого обращения.

- 2011: Мелленкамп: женщина, которая постарела из-за того, что она «пума », названа в честь Джона Кугара Мелленкампа.

- 2012: вши у ворот: пассажиры авиакомпаний, которые толпятся вокруг выхода и ждут посадки.

- 2013: сом : чтобы представить себя в Интернете в ложном свете, особенно как часть романтического обмана.

- 2014: columbusing: культурное присвоение, особенно акт белого человека, заявляющего об открытии вещей, уже известных культурам меньшинств.

- 2015: ammosexual: тот, кто любит огнестрельное оружие в фетишистской манере.

- 2016: laissez-fairydust: магический эффект, вызванный экономикой laissez-faire.

Самое ненужное

- 2008: moofing (PR-фирма- создан термин для работы на ходу с ноутбуком и мобильным телефоном)

- 2009: sea kittens (попытка ребрендинга рыбы со стороны PETA )

- 2010: refudiate ( смесь слов опровергнуть и отвергнуть, использованная Сарой Пэйлин в Твиттере)

- 2011: двукратный выигрыш (термин, используемый Чарли Шином для описания сам гордо отвергая обвинения в биполярном )

- 2012:законном изнасиловании (тип изнасилования, который, по утверждению кандидата в Сенат Миссури Тодд Акин, редко приводит к беременности)

- 2013: sharknado (торнадо, полное акул, как показано в одноименном фильме Syfy Channel)

- 2014: baeless: без романтического партнера (без bae).

- 2015: manbun: мужская прическа собрана в пучок.

Самая возмутительная

- 2008 :террористический удар кулаком (фраза для удар кулаком придуман Fox News диктором Э. Д. Хилл )

- 2009: комиссия по смерти (предполагаемый комитет врачей и / или бюрократов, которые будут решать, какие пациенты будут лечиться, а какие нет)

- 2010: изнасилование на посадке (уничижительный термин для агрессивной процедуры обысков в новом аэропорту)

- 2011: ассолократия (правление неприятных мультимиллионеров)

- 2012: законное изнасилование (тип изнасилование, которое, как утверждал кандидат в Сенат Миссури Тодд Акин, редко приводит к беременности)

- 2013: нижняя часть ягодиц (видна из-за некоторых шорт или нижнего белья)

- 2014: вторая поправка : v. Убить (кого-то) из пистолета, иронично используется сторонниками контроля над оружием.

- 2015: fuckboy, fuckboi: унизительный термин для человека, который ведет себя неугодно или беспорядочно..

Самый эвфемистический

- 2008 : техник-черпатель (человек, чья работа — собирать собачий помет)

- 2009 : поход по Аппалачской тропе (идти уйти, чтобы заняться сексом со своим незаконным любовником, из заявления, выпущенного под редакцией губернатора Южной Каролины Марка Сэнфорда для прикрытия посещения своей аргентинской любовницы)

- 2010 : кинетическое событие (термин Пентагона для насильственных атак на войска в Афганистане)

- 2011 : лицо, создающее работу (лицо, ответственное за экономический рост и занятость)

- 2012 : самодепортация (политика поощрения нелегальных иммигрантов к добровольному возвращению в свои страны)

- 2013 : наименее неправдивый (включая минимальную необходимую ложь, используется директором разведки Джеймсом Клэппером)

- 2014 : EIT : сокращение от уже эвфемистического «усиленного метода допроса».

- 2015 : Netflix и расслабление: сексуальные действия, замаскированные под предложение посмотреть Netflix и расслабиться ».

Скорее всего, добьется успеха

- 2008:готов к работе (описание инфраструктурных проектов, которые можно начать быстро, когда станут доступны средства)

- 2009: двадцать десять (произношение 2010 года, в отличие от слов «две тысячи десять» или « две тысячи десять «)

- 2010: тренд (глагол для демонстрации всплеска онлайн-шума)

- 2011: облако (онлайн-пространство для крупномасштабной обработки и хранение данных)

- 2012: равенство брака (юридическое признание однополых браков)

- 2013: запойные часы (для просмотра большого количества одного шоу или серию визуальных развлечений за один присест)

- 2014: соленый: исключительно горький, сердитый или расстроенный.

- 2015: призрак: (глагол) резко прекратить отношения, прервав общение, особенно онлайн.

Наименьшая вероятность успеха

- 2008: PUMA (аббревиатура от «Party Unity My Ass», а затем, «People United Means Action », использованная демократами, которые были разочарованы после Хиллари Клинтон не смогла набрать достаточное количество делегатов)

- 2009: Непослушные, Огути, Оугти и т. Д. (Альтернативные имена для десятилетия 2000–2009 )

- 2010: culturomics (исследовательский проект от Google, анализирующий историю в зависимости от языка и культуры)

- 2011: брони (взрослый мужчина, фанат франшизы мультфильма «My Little Pony »)

- 2012: фаблет (электронное устройство среднего размера, между смартфоном и планшетом )

- 2013:Благодарением (слияние Дня Благодарения и первый день Хануки, который не повторится еще 70 000 лет)

- 2014: platisher: издатель интернет-СМИ, который также служит платформой для создания контента.

- 2015: sitbit: устройство, которое награждает малоподвижный образ жизни (играйте на фитнес-трекере Fitbit).

Особые категории

- Election-Related Word (2008): maverick (человек, который никому не обязан, широко используется Республиканские кандидаты в президенты и вице-президенты Джон Маккейн и Сара Пэйлин )

- Fan Words (2010): gleek (фанат телешоу Glee )

- Occupy Words (2011): 99%, 99% респондентов (тех, кто находится в невыгодном финансовом или политическом для самых прибыльных, однопроцентников)

- Выборные слова (2012): папки (полные женщин) (термин, используемый Миттом Ромни во втором президентские дебаты по описанию резюме женщин-кандидатов на работу, с которыми он консультировался как губернатор Массачусетса )

- Самый продуктивный (2013): — позор: (от позор для шлюх ) тип общественности унижение (прищуривание, позорение животных ).

- Самый известный хэштег (2014): #blacklivesmatter: протест против чернокожих, убитых от рук полиции (особенно. Майкл Браун в Фергюсоне, штат Миссури, Эрик Гарнер в Стейтен-Айленде).

Австралийский национальный словарь-центр

Австралийский национальный словарь-центр объявляет «Слово года» каждый декабрь с 2006 года. Это слово выбрано редакцией, исходя из того, что оно получило известность в австралийском социальном и культурном ландшафте в течение года. Слово года часто упоминается в средствах массовой информации как слово года в Австралии, но это слово не всегда является австралийским.

| ГОД | |

|---|---|

| 2006 | подкаст |

| 2007 | me-tooism |

| 2008 | GFC |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | vuvuzela |

| 2011 | |

| 2012 | зеленый по синему |

| 2013 | биткойн |

| 2014 | рубашка спереди |

| 2015 | экономика совместного использования |

| 2016 | демократия колбаса |

| 2017 | Кваусси |

| 2018 | Канберрский пузырь |

| 2019 | Голос |

Словарь английского языка Коллинза

Словарь английского языка Коллинза объявил о выпуске Word of the Year каждый год с 2013 года, а до этого объявлял новое «слово месяца» каждый месяц в 2012 году. Изданный в Глазго, Великобритания, Collins English Dictionary публикует английские словари с 1819 года.

Ближе к концу каждого календарного года Коллинз выпускает короткий список примечательных слов или слов, которые стали известны за предыдущие 12 месяцев. Шорт-лист обычно состоит из десяти слов, хотя в 2014 году только четыре слова были объявлены шорт-листом «Слово года».

Слова года Коллинза выбираются командой Collins Dictionary в Глазго и Лондоне, состоящей из лексикографов, редакторов, маркетологов и сотрудников отдела рекламы, хотя ранее процесс отбора был открытым для общественности.

Хотя слово не обязательно должно быть новым для характеристики, появление слов в списке часто подтверждается статистикой использования и перекрестными ссылками на обширный корпус Коллинза, чтобы понять, как язык мог измениться или развиться в в прошлом году. Слово года Коллинза также не ограничивается использованием британского языка, и часто выбираются слова, которые применимы и на международном уровне, например, фейковые новости в 2017 году.

| Год | Слово года | Определение | Shortlist |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Компьютерщик | Если вы называете кого-то, обычно мужчину или мальчика, компьютерщиком, вы недобро говорите, что он глупый, неловкий, или слабый. | Twerking

Bitcoin Phablet Plebgate Fracker Cybernat бедро пробел Олингито Черная пятница Кредитование до зарплаты Гарлем Шейк |

| 2014 | Фотобомба | Если вы фотобомбите кого-то, вы испортите сфотографировать их, когда они встают перед ними во время съемки, часто делают

что-нибудь глупое, например, корчит рожи. |

Tinder

Bakeoff Normcore Devo Max |

| 2015 | Часы с выпивкой | Если вы смотрите телесериал с запой, вы смотрите несколько серий один за другим за короткий промежуток времени. ime. | Dadbod

Shaming Corbynomics Чистая еда Ghosting Swipe бесконтактный Распространение людей Трансгендеры |

| 2016 | Brexit | Выход Соединенного Королевства из Европейского Союза в марте 2019 года. | Hygge

Mic drop Трампизм Бросок тени Обмен Поколение снежинок Чувственная еда Уберизация JOMO |

| 2017 | Фейковые новости | Ложная, часто сенсационная информация, распространяемая под видом новостных репортажей. | Антифа

Корбинмания Сезон запугивания Эхо-камера Фиджет спиннер Гендер-флюид Гигантская экономия Insta Unicorn |

| 2018 | Одноразовые | Предназначены для однократного использования. | Блокиратор обратного хода

Мулине Гаммон Газовый свет MeToo Plogging VAR Vegan Whitewash |

| 2019 | Climate st Райк | Бопо

Отмена Дипфейк Двойной удар Entryist Hopepunk Влиятельный человек Недвоичный Rewilding |

Словарь Маккуори

Словарь Маккуори, который является словарем австралийского английского языка, ежегодно обновляет онлайн-словарь новыми словами, фразами и т. Д. и определения. Их можно просмотреть на их веб-сайте.

Каждый год редакторы выбирают краткий список новых слов, добавленных в словарь, и приглашают общественность проголосовать за их любимые слова. Общественное голосование проводится в январе, по результатам которого определяется победитель конкурса «Выбор народа». Самое влиятельное слово года также выбирается Комитетом «Слово года» под председательством вице-канцлера Сиднейского университета д-ра Майкла Спенса. Редактор словаря Macquarie Сьюзан Батлер также является членом комитета. Комитет собирается ежегодно, чтобы выбрать слова-победители.

Ниже приводится список слов, выигравших с тех пор, как в 2006 году было объявлено «Слово года Маккуори»:

| Год | Выбор комитета | Выбор народа |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | маффин-топ | (Победителя нет. Список победителей см. На веб-сайте Macquarie) |

| 2007 | прихлебывание стручка | усталость пароля |

| 2008 | токсичный долг | flashpacker |

| 2010 | googleganger | shockumentary |

| 2011 | burqini | fracking |

| 2012 | синдром фантомной вибрации | проблема Первого мира |

| 2013 | infovore | onesie |

| 2014 | mansplain | shareplate |

| 2015 | вызов капитана | вызов капитана |

| 2017 | утка молочный коктейль | framily |

| 2018 | я тоже | одноразовый |

| 2019 | отменить культуру | robodebt |

Merriam-Webster

Списки слов Merriam-Webster of the Year (на каждый год) — это списки из десяти слов, ежегодно публикуемые американской компанией по издательству словарей Merriam-Webster, Inc., в которых представлены десять слов года из английского языка. Эти списки слов были начаты в 2003 году и публикуются в конце каждого года. Сначала компания Merriam-Webster определила его содержание, проанализировав попаданий на страницу и популярных поисковых запросов на своем веб-сайте. С 2006 года список составляется на основе онлайн-опроса и предложений посетителей веб-сайта.

Ниже приводится список слов, которые с тех пор стали «Словом года» компании Merriam-Webster. 2003:

- 2003 : демократия

- 2004 : блог

- 2005 : честность

- 2006 : правдивость

- 2007 : w00t

- 2008 : спасение

- 2009 : предостережение

- 2010 : жесткая экономия

- 2011 : прагматический

- 2012 : социализм и капитализм

- 2013 : наука

- 2014 : культура

- 2015 : -изм

- 2016 : сюрреалистический

- 2017 : феминизм

- 2018 : Правосудие

- 2019 : Они

Oxford

Oxford University Press, издающая Oxford English Dictionary и многие другие словари, объявляют Oxford Dictionaries UK Word of the Year и «Слово года в США» от Oxford Dictionaries; иногда это одно и то же слово. Слово года не обязательно должно было быть придумано в течение последних двенадцати месяцев, но оно должно стать заметным или заметным за это время. Нет гарантии, что «Слово года» будет включено в какой-либо Оксфордский словарь. Слова года в Оксфордских словарях выбираются редакцией из каждого из оксфордских словарей. Команда отбора состоит из лексикографов и консультантов команды словарей, а также сотрудников редакции, маркетинга и рекламы.

| Год | Слово года в Великобритании | Слово года в США |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | chav | |

| 2005 | sudoku | подкаст |

| 2006 | bovvered | углеродно-нейтральный |

| 2008 | hypermiling | |

| 2009 | простые (Сравните крылатую фразу Суриката ) | разобщить |

| 2010 | большое общество | отказать |

| 2011 | зажатое середина | |

| 2012 | омнишабл | GIF (имя существительное) |

| 2013 | селфи | |

| 2014 | vape | |

| 2015 | 😂 (Face With Tears of Joy, Unicode : U + 1F602, часть эмодзи ) | |

| 2016 | постправда | |

| 2017 | молодежное землетрясение | |

| 2018 | токсичный | |

| 2019 | климатическая чрезвычайная ситуация |

Грант Барретт

С 2004 года лексикограф Грант Барретт публикует список слов года, обычно в New York Times, хотя он не называет победителя.

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013 в New York Times, также подробнее полный список

Dictionary.com

В 2010 году Dictionary.com объявил о своем первом слове года «изменение» и делает это ежегодно в декабре. поскольку. Выбор основан на тенденциях поиска на сайте в течение года и новостях, которые ими движут.

Ниже приводится список ежегодных слов с начала с первого в 2010 году:

- 2010 : Изменение

- 2011 : Tergiversate

- 2012 : Bluster

- 2013 : Конфиденциальность

- 2014 : Exposure

- 2015 : Identity

- 2016 : Ксенофобия

- 2017 : Явные

- 2018 : Дезинформация

- 2019 : Экзистенциальные

Списки похожих слов

Слово в год

С 2004 года Сьюзи Дент, английский лексикограф, издала столбец «Слово в год», в котором она выбирает по одному слову из каждого слова. последних 101 года, чтобы представить заботы времени. Сьюзи Дент отмечает, что список субъективен. Каждый год она дает совершенно другой набор слов.

Поскольку Сьюзи Дент работает в Oxford University Press, ее избранные слова часто ошибочно называют «Словом года Оксфордского словаря».

Другие страны

В Германии, Wort des Jahres выбирается с 1972 года (на 1971 год) Обществом Немецкий язык. Кроме того, Unwort des Jahres (Un-word of the year или No-no Word of the Year) номинировался с 1991 года за слово или фразу в публичной речи, считающейся оскорбительные или социально неприемлемые (например, «Überfremdung »). Подобные отборы производятся ежегодно с 1999 г. в Австрии, 2002 г. в Лихтенштейне и 2003 г. в Швейцарии.

В Дании с 2008 года выбирают Danmarks Radio и Dansk Sprognævn.

В Японии кандзи года (котоси-но кандзи) выбирается с 1995 года. иероглифы являются заимствованными китайскими иероглифами в японском языке. язык. В Японии также проводится ежегодный конкурс «Слово года» под названием «Гран-при U-Can New и Trendy Word» (U-Can shingo, ryūkgo taishō), спонсируемый Джию Кокуминша. И кандзи, и слово / фразы года часто отражают текущие события и отношения в Японии. Например, в 2011 году, после аварии на АЭС Фукусима, разочаровывающе загадочная фраза, которую японские официальные лица использовали перед взрывом относительно возможности расплавления — «вероятность повторной критичности не равна нулю» (Sairinkai no kanōsei zero de wa nai), стала верхняя фраза года. В том же году кандзи, обозначающее «связь» (т. Е. Семейные узы или дружба), стало кандзи года, выражая важность коллективности перед лицом катастрофы.

В Норвегии Слово года опрос проводится с 2012 года.

В Португалии Слово года проводится с 2009 года.

В России Голосование года проводится с 2007 года.

В Украине голосование Слово года проводится с 2013 года.

См. Также

- Language Report из Oxford University Press

- Списки слов года Merriam-Webster

- Neologism

- Doublespeak Award

- Кандзи года

Дополнительная литература

- Джон Эйто, «Век новых слов», Серия: Оксфордский справочник в мягкой обложке (2007) ISBN 0-19-921369-0

- Джон Айто, «Слова двадцатого века», Oxford University Press (1999) ISBN 0-19-860230-8

Ссылки

Внешние ссылки

- Популярные слова fr om 2000 — настоящее время @ Global Language Monitor

- Архив Word of the Year @ Словарь Macquarie

- Архив Word of the Year @ Merriam-Webster

- Слово года Архив @ OxfordWords blog

- Австрийское слово года

- Канадское слово года

- Слово года в Лихтенштейне

- Слово года в Швейцарии

- Слово года Dictionary.com @ Dictionary.com

Words are fun, finicky, and ever-evolving. As time goes by, new words make their way into common usage and old words take on new meanings. Each year, there’s one term that stands out the most. That’s why the American Dialect Society (ADS), an organization that’s «dedicated to the study of the English language in North America, and of other languages, or dialects of other languages, influencing it or influenced by it,» annually chooses a word or phrase to highlight. It may be important for political or pop culture reasons; it could be one that’s way out of use today or one that’s getting increasingly popular. From its inaugural winner in 1990, here is every ADS Word of the Year through today. And for more to appreciate, here are The 50 Most Beautiful Words in the English Language—And How to Use Them.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush delivered a speech at the Republican National Convention in which he told the crowd, «Read my lips: no new taxes.» That promise was broken, and «bushlips» (as in bush lips) made its way into popular language as a way to describe «insincere political rhetoric,» according to the ADS. They chose it as their word of the year in 1990.

And fascinating regional dialects, here are 60 Words People Pronounce Differently Across America.

The word of the year in 1991 was actually a collection of words that made up what you might consider a momentum-building prefix. Add «mother of all» to whatever you’re referring to and it immediately makes it the greatest, biggest, or most impressive example of something. To bring the phrase into today’s world, the mother of all Instagrammable cafés is the most social media-worthy eatery around.

The only time you’re likely to hear someone use the expression «not!» nowadays is if they’re dressing up as a Wayne’s World character for Halloween. However, in 1992, it was the word of the year (with the exclamation mark included for needed emphasis, of course).

And for more indelible expressions from the decade, here are 30 Movie Quotes Every ’90s Kid Knows by Heart.

In 1993, «information superhighway» was the term to use when referring to modern communication methods. And while these days you might be talking about texts or FaceTiming, in 1993, data was shared primarily via computers, televisions, and telephones.

In 1994, «cyber» («pertaining to computers and electronic communication») was named the word of the year—but it wasn’t alone. The ADS called a tie, also choosing «morph» («to change form») as one of the top words of those particular 12 months.

And for some out-of-date words that used to be all the rage, here are 150 Slang Terms From the 20th Century No One Uses Anymore.

The tie of 1994 was the first time the ADS chose two terms as the co-words of the year, but it wasn’t the last. It may be hard to imagine life without the internet today, but in 1995, surfing the «world wide web» was still new and thrilling. That’s why it was the word of the year, as was «newt,» which refers to the act of «mak[ing] aggressive changes as a newcomer.»

In 1996, soccer moms weren’t just women who were taking their kids to sports practices—they were an entire demographic that was identified as a «newly significant type of voter,» according to the ADS. That’s why «mom,» taken from soccer mom, was chosen as the word of the year.

And for terms you’ve been pretending to understand, here are 50 Words You Hear Every Day But Don’t Know What They Mean.

«Millennium bug» was widely used to refer to a tech-related glitch that supposedly threatened to shut down computers (and everything run by computers) if the devices weren’t able to handle the rare change in date when January 1, 2000 rolled around. Of course, it turned out to be unwarranted anxiety. But the fear—and the phrase—were very real.

The word of the year in 1998 wasn’t a word at all. It was part of a word. Or, to be more exact, it was a prefix. Short for electronic, «e-» became the ADS’s word of the year since it was being widely used in terms like «e-mail» and «e-commerce.»

And for more language facts delivered right to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter.

As the world prepared for the new millennium, the term «Y2K» (which stands for the year 2000) became all the rage. Fittingly the ADS’s word of the year for 1999, the term was widely used to refer to the Y2K bug or Y2K scare, which was another name for the millennium bug.

If you think of the term «chad» solely as a man’s name today, you’re not alone. But in the year 2000, the presidential election controversy led to the ADS choosing it for the meaning «a small scrap of paper punched from a voting card.»

In 2001, the United States suffered one of the deadliest attacks within its borders on Sept. 11, a date that was chosen as the word of the year. The infamous day that is now a part of the darker side of the country’s history also became known as 9-11 and 9/11.

It’s certainly a sad situation when «weapons of mass destruction» (or WMD) is chosen as the word of the year. But that was what happened in 2002 when the United States attempted to track down possible chemical and biological weapons as well as nuclear bombs in Iraq.

At the turn of the century, the world was finally ready to recognize and embrace the «metrosexual,» a man who cared about his appearance and was savvy about style. In 2003, it became the ADS’s word of the year.

Nearly 15 years later, The Telegraph claimed that the «metrosexual is dead—and a new kind of sensitive man killed him,» one who appreciates a «greater depth and meaning» and «place[s] the highest value on dependability, reliability, honesty, and loyalty.» We can all get behind that, right?

Political divisions in America are represented by two varying colors, which is why «red/blue/purple states» was the popular term in 2004 to identify which areas leaned a certain way. The American Dialect Society explains that «red favor[s] conservative Republicans and blue favor[s] liberal Democrats,» while those who are undecided are considered purple. Americans are much more used to hearing these terms today.

There’s the truth and then there’s «truthiness,» which is a term that «refers to the quality of seeming to be true but not necessarily or actually true according to known facts,» according to Merriam-Webster. The American Dialect Society chose «truthiness» as their word of the year in 2005 after it was popularized by Stephen Colbert and his right-wing parody show The Colbert Report, which launched that year.

Pluto has gone through a wild ride over the years in terms of classification. Once considered a planet, it was demoted when it no longer met the necessary criteria (something that is still being debated). And in 2006, the term «plutoed» was the word to use if you wanted to make a comparison between the spacial body and something else that had lost status or wasn’t being valued. Poor Pluto.

The word «subprime» is pretty self-explanatory—it’s something that’s, well, not exactly the best. When it comes to investments, specifically real estate, subprime is what you’d call a loan or deal that’s iffy or risky. And in 2007, buyers, sellers, and property flippers were all dealing with the Subprime Mortgage Crisis that hit the United States, which is why it became the word of the year.

When the government helps out a failing business, it’s called a bailout. And as you may recall in 2008, U.S. Congress approved a $700 billion Wall Street bailout that dominated headlines, hence ADS choosing it.

Twitter launched in 2006, and by January 2009, users were sending two million messages a day over the social media platform. That’s why the top word that year from the ADS was «tweet,» which can refer to either the action of sending text on the platform or the actual message itself.

An app is certainly not an unusual thing these days, but in 2010, it was a word that was newly buzzing. At the time, Ben Zimmer, chair of the New Words Committee of the American Dialect Society, noted, «With millions of dollars of marketing muscle behind the slogan ‘There’s an app for that,’ plus the arrival of ‘app stores’ for a wide spectrum of operating systems for phones and computers, app really exploded.» Hence it being crowned the word of the year at the close of one decade and the start of a new one.

Politics was at the forefront of the conversation in 2011 when «occupy» was selected as the word of the year. At the time, the Occupy Wall Street protest movement was ongoing, putting a spotlight on financial institutions and the economic inequality between the wildly wealthy one percent of the population and the other 99.

«Hashtag»—which is represented with the «#» and which Merriam-Webster calls a «symbol before a word or phrase [that’s] meant to be used on social media as a way to track certain terms»—was the word of the year in 2012. Zimmer explained the choice, saying, «In the Twittersphere and elsewhere, hashtags have created instant social trends, spreading bite-sized viral messages on topics ranging from politics to pop culture.»

«Because» is a term that was chosen as the word of the year due to the fact that people were using it in a slightly modified way in 2013. Instead of having to say «because of [insert reasoning here],» we could now drop the «of.» Confused? Here’s an example: Instead of saying «I an ate apple because I’m hungry,» you can say, «I ate an apple because hunger.» Or, instead of saying, «I need an umbrella because it’s raining,» you can say, «I need an umbrella because rain.» And if you don’t want to explain yourself at all, you can simply tell someone that you’ve done something «because reasons.»

In 2012, «hashtag» may have been recognized for its significance, but two years later, an actual hashtag was selected as the word of the year. Due to heightened awareness of the treatment of Black people by police and authority figures, #blacklivesmatter «became a rallying cry and vehicle for expressing protest» and was selected as the most significant word of the year in 2014.

«They» is certainly not a new word and isn’t one that only recently became commonly used. However, the way it’s used has changed in recent years. Once meant to refer to a group of individuals, it’s now also a way to identify a single person who is gender non-conforming or nonbinary and chooses not to use gender-specific pronouns.

Judging by the ADS’s word of the year, 2016 was a rough 12 months. «Dumpster fire»—which refers to «an exceedingly disastrous or chaotic situation»—was the term the ADS chose as the one that «best represent[ed] the public discourse and preoccupations of the past year.» And while it may have been the (dire) word of choice a few years ago, it’s still regularly used today.

In the age of the 24-hour news cycle and far-reaching social media platforms, it can be difficult to sort through what information is accurate and what is not. The past few years have seen real facts attacked and dismissed by some in an effort to deny, confuse, or misdirect others. So it’s no surprise the term «fake news» was deemed the word of the year in 2017.

The word of the year for 2018 was one that stems from a sad reality that has manifested within the United States. According to the ADS, the term «tender-age shelter/facility/camp» first emerged in June 2018 when it was reported that infants and young children were being held in special detention centers after being separated from their families who crossed over the southern border.»

Returning to the cultural shift that prompted 2015’s Word of the Year, the ADS chose «(my) pronouns» as the term that defined 2019. As awareness of differing gender identities has grown, it’s become more common for individuals of all genders to list their pronouns in e-signatures and bios, as well as to offer them verbally.

«When a basic part of speech like the pronoun becomes a vital indicator of social trends, linguists pay attention,» Zimmer explained in the ADS announcement. «The selection of ‘(my) pronouns’ as Word of the Year speaks to how the personal expression of gender identity has become an increasing part of our shared discourse.» In addition, the singular form of «they» was chosen as the Word of the Decade.