The history of factoring can be traced back thousands of years. However, arrangements that benefitted business owners or entrepreneurs in the days of trading grain are much different than what helps people in cash economies today. Factoring has evolved with the times too.

This page will walk you through the full timeline of factoring history, including its origins, how it evolved, and how it works today.

Invoice Factoring Definition

The word “factor” comes from “factus,” which means “done” or “made” in Latin. “Factor,” therefore, loosely translates to “doer” or “maker.” This is likely a nod to trade enablement. A factor is a person or organization that facilitates business activities, generally by providing resources.

Modern invoice factoring is a financial transaction in which a business sells its receivables to a factor at a discount in exchange for immediate cash. It’s differs from a loan because the business isn’t expected to pay back the money. Instead, the business’s customer clears the debt by remitting payment to the factor for the invoice.

Factoring in the Ancient World (3100 BCE – 539 BCE)

It’s often said that the first civilizations on earth were involved in factoring. This isn’t necessarily true, but the economic developments they made and the way they engaged in trade laid the groundwork for a variety of systems that evolved into the trade, banking, and financing systems we have today.

The Phoenicians (1550 BCE to 300 BCE)

Most people trace the history of factoring back to the Phoenicians, a group of people who lived in what’s now parts of Lebanon and Syria. To give some context, these people initially lived in very small groups, were spread out, and mostly survived on farming. They didn’t engage much with outsiders or trade. However, the communities were close-knit. If someone needed something and another person had it, it was generally freely given or lent. The concepts of credit or interest didn’t really exist.

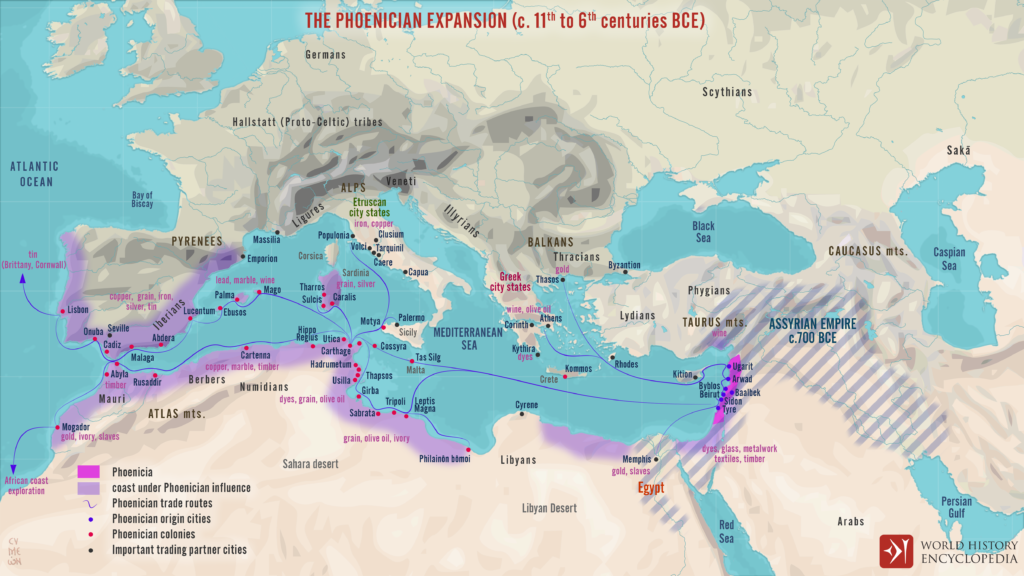

As Assyria expanded and took more land, these neighboring communities were pushed to the Mediterranean coastline. The area wasn’t suitable for farming, so the people took to the sea. In this sense, the Phoenicians were never a single unified society. “Phoenicia” was more of an alliance between the people of city-states such as Tyre, Byblos, Beirut, and Sidon, as Khan Academy explains.

The Phoenicians were primarily known for possessing a unique purple dye that they made from snails, which they traded all along the Mediterranean coast. In their travels, they also picked up metals, papyrus, wood, glass, textiles, and carved ivory, which they’d then carry with them and trade at their next stop.

This presented new challenges because prior groups didn’t readily trade with strangers. The states stepped in to regulate trade as a result. Prices, quantities, and exchange rates were all determined in advance per the World History Encyclopedia, and most trading took place in state-sanctioned trade centers. Credit was rarely extended. People typically traded items of equal value or paid on receipt of goods.

“The Phoenician Expansion c. 11th to 6th centuries BCE” by Simeon Netchev CC BY 4.0.

Mesopotamia (3100 BCE to 539 BCE)

Ancient Mesopotamia, which flourished from roughly 3100 BC to 539 BCE and sat in present-day Iraq and parts of Syria, is responsible for several developments in trade and credit that influence modern-day factoring too.

Sumer (4100 BCE to 1750 BCE)

Often referred to as “the cradle of civilization,” Sumer was situated in the southern part of Mesopotamia and existed from roughly 4100 BCE to 1750 BCE. The first mention of interest-bearing commercial and farm debts can be traced to the region, according to economist Michael Hudson, PhD. However, Hudson doesn’t think that Sumerians actually created the concept. Instead, he credits the Phoenicians for bringing it with them on their travels.

Whereas the Phoenicians traded in state-sanctioned trade centers, Sumerians usually traded in local temples. These temples were finance hubs and managed lending too. Sometimes nobility would be involved in trade and lending as well.

Babylon (2000 BCE to 540 BCE)

Situated in the central-southern region of Mesopotamia in what’s now Iraq, Babylon flourished from roughly 2000 BCE to 540 BCE, eventually overtaking Sumer as the center of Mesopotamian activity. This is where we start to see trade and financing in a way that more closely resembles modern factoring.

For example, Babylonian society largely ran on grain, but people didn’t carry grain around in their pockets to make purchases and only used coins some of the time, as Hudson explains in “Handbook of the History of Money and Currency.” People who ran the alehouses would have consignments advanced to them throughout the crop year, and those visiting the alehouses would run up tabs. When harvest time came, the customers would pay their tabs in grain. Those running the alehouses would then deliver most of the grain to the palace as repayment.

Similar arrangements were seen with merchants. However, in this era, merchants weren’t quite like they are today. They were called “tamkarum,” as Cem Eke explains in “The Roles of the Merchant in Ancient Babylon.” Rather than simply trading, tamkarum held high-status positions in society and often represented the palace. For example, they were responsible for documenting trades, which would then be reported to the palace for taxation purposes. They were also among the first bankers. They decided who was credit-worthy and how much credit could be extended, then also lent the money. Because the concept of collateral didn’t exist, some consider the tamkarum to be the first investors too. They had to be very careful about who received their funds.

Additionally, the tamkarum are often seen as the first factors due to their involvement in purchasing receivables. If a Babylonian fell behind on paying rent for his land to the palace, the tamkarum would purchase the debt from the palace at a discount. The palace usually received about two-thirds of the value, and the tenant would then be responsible for paying the tamkarum back.

Tamkarum also hired commission agents to travel to other cities and purchase goods. The agents would bring the goods back and the tamkarum would resell them at a profit. To facilitate this, the tamkarum would make a cash advance to the agent. The agent was then responsible for documenting the agreement and giving the receipt to the tamkarum. Whoever held the receipt was entitled to the goods being purchased by the agent, so the receipts were sometimes sold at a discount as well.

Hammurabi’s Code (c. 1780 BCE)

These transactions set the stage for Hammurabi’s Code, which lists some of the earliest laws on record. Estimated to be drafted around 1700 BCE at the direction of King Hammurabi, the stone etchings contain 282 statutes that cover everything from penalties for causing physical harm to trade and finance laws. One such statute notes:

“If a merchant gives to an agent grain, wool, oil, or goods of any kind with which to trade, the agent shall write down the value and return the money to the merchant. The agent shall take a sealed receipt for the money which he gives to the merchant.”

This law covers the type of arrangement the tamkarum had with their agents and paved the way for modern laws relating to funding documentation.

Ancient Greece and Rome (753 BCE to 476 CE)

The people of ancient Greece and Rome also traded with the Phoenicians, referring to them as the “traders in purple” or “purple people” due to their famed dye. It’s not surprising, then, that ancient Greeks and Romans picked up many of the finance and trading behaviors that were common in the era too.

A veritable treasure trove of Roman promissory notes unearthed in London in 2014, with some dating back as far as 57 CE, is a prime example. Written in Latin cursive on a wooden tablet that was originally covered in beeswax, one reads: “I, Tibullus, the freedman of Venustus have written and say that I owe Gratus, the freedman of Spurius, 105 denarii from the price of merchandise which has been sold and delivered …” as reported by National Geographic.

It’s often thought that these Greek and Roman promissory notes were bought and sold at a discount, similar to Sumerian tamkarum behavior, and much like modern factors. They typically managed banking-type affairs within temples too.

During this era, we also see the emergence of “bottomry,” a method of funding for merchant travel. The borrower could get upfront cash before the ship departed and was expected to repay funds after the goods were sold. If the sales were inadequate, the ship would then be turned over to the investors. If the ship didn’t reach its intended destination, the debt was forgiven. There are clear parallels between this and modern factoring, though historians also believe this is how insurance got its start.

In ancient Rome, societas began forming too. These can be likened to modern corporations, as Peter Temin explains in “The Roman Market Economy;” though the intent was to pool resources that could fund maritime activities. Cato, for example, provided one-fifteenth of the funding necessary for a group of 50 ships. It’s often believed that a similar funding method enabled Claudius to construct the Ostia harbor in 42 CE as well. Being the “gateway to ancient Rome,” the port was vital in the transport of goods, but sandbars prevented larger ships from passing through. Julius Caesar and Augustus both wanted to remedy this, but neither could find a way to address costs, the Colosseo Collection explains.

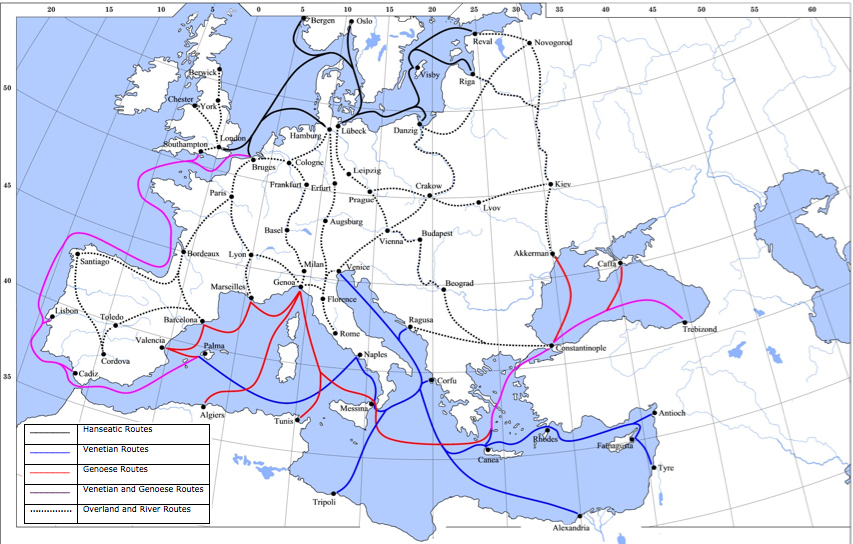

Factoring in Europe (1200 CE to 1820 CE)

Trade in Europe in the early middle ages didn’t drastically differ from that seen with the Romans, as explained by World History. The financial systems were quite similar too, though Temin notes that Amsterdam and London were the most advanced at the time. In these regions, merchants provided purchasers and suppliers with financing without the involvement of third parties. However, it was somewhat common to sell the promissory note locally. “A bill obligatory could be sold to a third person in England,” he explains, “but it did not travel far because it had to come back to the borrower for payment.”

It’s only as we move into the late medieval era that trade dramatically expands, and with it came new ways to finance it.

Italy and France (c. 1200 CE)

In the ancient world, receipts and promissory notes served as funding agreements between two people. These were sometimes bought and sold at a discount, similar to factoring. Whoever held the note or receipt was owed the debt. Moving into the medieval era, that was not always the case. Those extending credit began authorizing others to collect on their behalf. That is a trait shared with modern invoice factoring too, as businesses grant the factor permission to collect an invoice’s value from their client as payment. One of the earliest records of this is a document from 1248, as shared by The Journal of Political Economy:

“I, Aubertus Acua, citizen of Marseilles, constitute you, Dodonus Baldissonus, as my present, certain, and special agent, to demand, collect, and recover from Ricavus Pisanus, a citizen of Marseilles, 250 byzants of Acre which he is under obligation to pay unto me…”

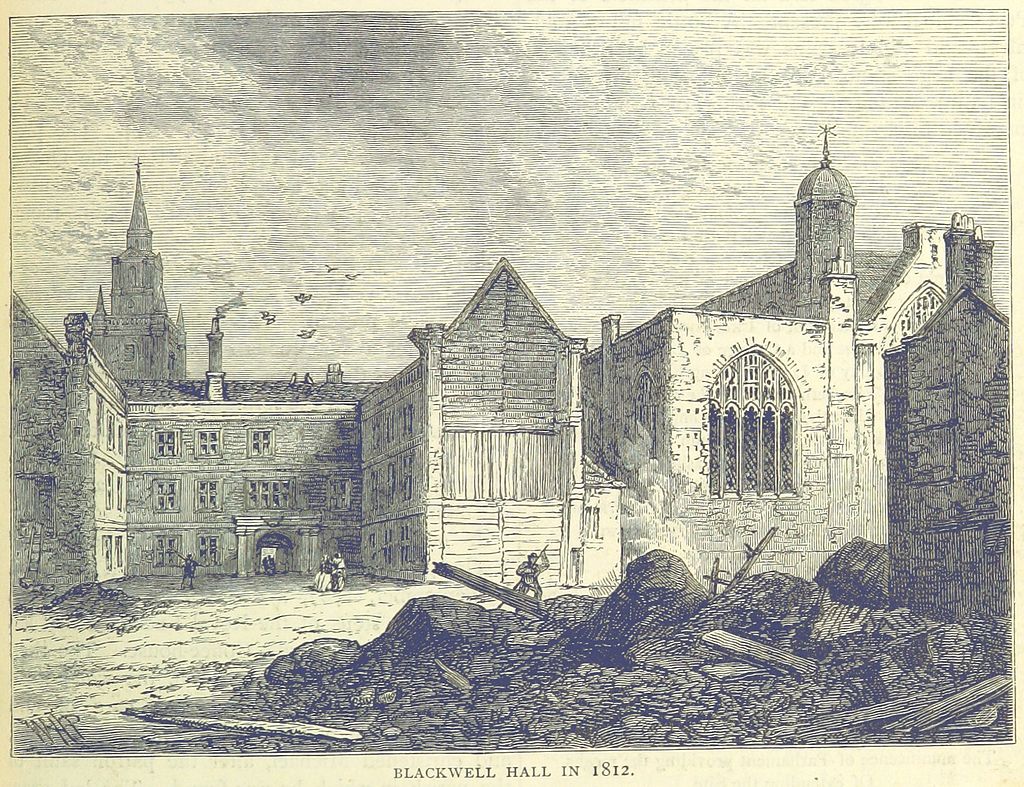

England – Blackwell Hall (c. 1397 CE to 1820 CE)

Up until this point in the history of factoring, the word “factor” was not used as it relates to trade or funding. That changes as we move into medieval England with the introduction of the Blackwell factors.

Established in the 14th century and lasting through the 18th, Blackwell Hall was the center of the woolen cloth trade in London. The marketplace gave non-citizen and foreign cloth manufacturers and clothiers the opportunity to display and sell their material to merchants and drapers. Blackwell Hall factors played a crucial role in the process by finding a market for the cloth, supplying the raw wool, and providing credit that allowed the manufacturers and clothiers to operate, as explained by Conrad Gill in “Blackwell Hall Factors.”

England – Maritime Trading (1450 CE to 1789 CE)

International travel and trade became more common throughout the late medieval and early modern eras. Just as prospectors headed west en masse during the American gold rush, much of Europe wanted to claim a share of the riches being discovered in India. In this case, however, the bounty was spices, cotton, and silk.

Trading posts sprung up across Europe during this period, starting around the mid-1300s. Typically built with the permission of local governments with the intent to trade with natives, these establishments were referred to as “factories.” They’re a large part of the reason why trading companies like the East India Company and the Hudson Bay Trading Company boomed during the era.

East India Company’s first factory was established in 1611 in the Indian city of Masulipatam, according to TutorialsPoint. Thereafter, each factory created followed the same structure as follows per East India Company factory records:

- The company would choose a location for a factory; typically an area already known for commerce.

- A ship would visit and leave behind a chief factor and council of factors to build relationships with the natives and get set up.

In other words, a factory might start out as a warehouse or market, then eventually grow into a defensible post for exploration, and ultimately serve as a governmental head for the local community. A factor, in this sense, wasn’t just a funding specialist. He was responsible for the goods and maintaining order.

The Columbus Voyage Debate (1492)

It’s often taken as a fact that Christopher Columbus’ voyage to America was paid for by factors. It makes sense given that factors or factoring-like activity routinely funded maritime activities during the period. However, these claims are unsubstantiated, and it’s important to remember that the initial voyage was more exploratory in nature. Columbus was trying to find a more efficient route to India and wanted to earn a bounty for being the first to spot land, as explained in “Columbus’s First Voyage: Profit Or Loss From A Historical Accountant’s Perspective.” The first trip was not a financial success.

What we do know is that Columbus put a 12.5 percent stake in the venture, and the Spanish crown funded the remaining portion. This included providing the ships, of which two were taken from Palos as a penalty for alleged piracy. This means Columbus could not have worked out a traditional bottomry deal as he didn’t have a claim to the ships. He was also without money, as the crown was covering his living expenses for years prior to the voyage. It’s likely he took out a traditional loan to cover his 12.5 percent share of costs.

The throne was also short on cash at the time due to recent wars. Many contend that Queen Isabella used the crown jewels as collateral, but this, too, is unsubstantiated. As shown in the profit and loss document, Luis de Santangel helped make the connection. He was treasurer to both the king and the Santa Hermandad. The crown borrowed its portion from the Santa Hermandad under a two-year loan with 14 percent interest. Most sources agree that this loan was paid off much earlier. Given the crown’s financial status, it’s assumed multiple government agencies floated the money until the balance was paid.

Factoring in Colonial North America (1492 CE to 1763 CE)

Maritime activity played a role in the expansion of knowledge and customs throughout the history of factoring. This was shown in ancient times, first with the Phoenicians, then later, with the Greeks and Romans. It’s not surprising, then, that the earliest settlers in America brought factoring with them to the new world too.

Plymouth Colony (1620 CE to 1691 CE)

The Plymouth Colony is often credited as being the first settlement in America funded by factoring. Indeed, it was quite similar. Capital for the Mayflower’s voyage and subsequent settlement was raised by a group of 70 merchant adventurers from London, as PBS News Hour explains. By their account, the pilgrims were in debt, expected to send furs and other goods back to London as repayment.

Additionally, the pilgrims agreed to a seven-year labor contract with the merchant adventurers and were guaranteed equity in the company, according to Yahoo Finance. This makes the situation unique. They were treated like employees, yet they were also governed by a setup like earlier factory systems. In a way, they were like shareholders too.

At the same time, there’s evidence to suggest that many of the earliest investors didn’t stick with the company. Instead, lean times resulted in a reorganization, according to Mayflower History. Just four investors stayed on and, along with a group of leading Plymouth colonists, bought out the remaining investors. No documents related to the deal or structure are available, so this could have been handled like a shareholder buyout or similar to the way Greeks and Romans bought and sold promissory notes at a discount—a precursor to modern factoring.

Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630 CE to 1691 CE)

Settlers in Massachusetts had similar arrangements. “Merchants and financiers in colonial Massachusetts engaged in continuing shifting partnerships that expired after a voyage,” explains Peter Temin in “The Roman Market Economy.” However, he notes that this was on a much smaller scale than what was seen in Plymouth or Rome; none had anywhere near 50 ships or investors.

York Factory (1684 CE to 1957 CE)

Trading companies had a comparable approach in Canada too. Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), for example, established York Factory on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in Manitoba. This was a unique factory because it was only accessible by sea and eventually grew into a large, fortified complex with numerous buildings.

The factory enabled HBC to manage business dealings with natives and was used heavily for fur trading. The French and English battled over the complex repeatedly throughout the late 1600s and early 1700s. It was ultimately returned to British control in 1713, at which time HBC again began using it as a headquarters. It remained in operation until 1957. The site still exists and is operated by Parks Canada today.

United States Fur Factory System (1795 CE to 1822 CE)

Columbus and some of the earliest settlers made a point of befriending native people. “I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection,” Columbus explained in a 1493 letter to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. He went so far as to forbid his men from trading things of little or no value in pursuit of building rapport.

Because of this, Native American nations often had stronger ties with those representing various crowns than they did with local settlers. Adding to this, early colonists did not necessarily take the same approach to trading. The fraud and unfair practices of some traders caused distrust between the settlers and native people. Yet, developing and maintaining good relationships was crucial to Americans following the Revolutionary War.

George Washington, the first president of the United States, had previously been a British colonial officer. He understood the advantages and drawbacks of British trade practices very well, and knew that building better relationships with native nations hinged on developing better trade practices. As such, he proposed America’s federal factory system in 1795, the Encyclopedia of United States Indian Policy and Law explains.

The factory system had many commonalities with the financial and trade systems that came before it. For example, a “factory” was akin to a trading post or marketplace and run by the government, similar to the way Blackwell Hall operated. Whereas Blackwell Hall was largely dedicated to wool, American factories were dedicated to the fur trade, like York Factory in Canada was. Moreover, all policies and prices were set by the government, a process that can be traced back to the Phoenicians.

The operational hierarchy was similar to previous establishments too. Each factory was headed up by a factor who was appointed to the position by the president. A factor was expected to track and report all money, goods, and furs that passed through the factory and report it to the government. No personal trading was allowed.

However, the American factory system was unique in that it was not run for profit. Washington set it up purely to nurture relationships with Native Americans, and it worked. After the initial two-year run, the factory system was renewed repeatedly, ultimately remaining in operation for nearly 30 years.

Factoring in Modern America (c. 1800 CE to 1900 CE)

Factoring carried many of these common traits into the modern era. For example, a factor was someone who held and advanced against consigned inventory for a merchant. Most of these arrangements involved distant merchants, especially those overseas. The factor guaranteed the collection of local sales and, as such, accepted a certain degree of risk. Because of this, the merchant would only advance 50 to 70 percent of the inventory’s value.

McKinley Tariff (1890 CE)

The Tariff Act of 1890, also known as the McKinley Tariff, resulted in some dramatic changes. It was designed to protect domestic industries from foreign competition and raised the average duty on imports to almost 50 percent, as explained by House of Representatives research. This naturally reduced demand for factoring services involving consignment among foreign merchants. It also changed the sales process in America, as local manufacturers began selling on their own more. Rising to meet the needs of this new market, factors left the consignment business and, instead, focused on purchasing and advancing against receivables. At this stage, factors also moved from primarily supporting the textiles industry to supporting a variety of industries.

Assignment of Claims Act (1940 CE)

Thus far in the history of factoring, a business could only offer a claim to its receivables for private and corporate agreements. Assignment of claims against the government was banned, as explained by the University of Chicago Law Review. In other words, a business could sell its invoices or borrow against them in many situations, but it could not do so if its client was a government agency.

Because small businesses have historically been seen as more risky borrowers and thus have reduced access to credit, the policy made it difficult for them to bid on and accept government contracts. This also hindered the government’s ability to ramp up for World War II.

The Assignment of Claims Act of 1940 lifted the ban, making it easier for small businesses to obtain the working capital necessary to accept government defense contracts. Many believe this change in legislation funded the war efforts. The law remains in effect today, giving more small businesses the opportunity to accept government contracts.

The Changing Face of a Factor (1920 CE to 2000 CE)

Up until this point, factors were primarily individuals, small groups of people pooling resources, or individuals representing the interest of trading companies. These new laws and economic changes resulting from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 gave rise to the factor as a financial company.

Initially, asset-based lenders began acquiring smaller factors. By the mid-1940s, banks, such as the First National Bank of Boston, also began offering factoring to their clients. Moving into the 1960s, the American style of factoring made its way back to England. This spurred even more banks to begin offering factoring and acquiring factoring companies over the next few decades.

By the end of the 21st century, more small factoring companies began springing up. Oftentimes, these had a boutique-like appeal and catered to a specific industry. For example, Viva specializes in transportation factoring, as well as oilfield, construction, manufacturing, healthcare, and more.

Invoice Factoring Today

These days, banks tend to favor working capital solutions like traditional loans, lines of credit, and credit cards. They’re more long-term solutions with greater payouts and less risk, but they also tend to be inaccessible to small businesses due to credit concerns, time in business, and other rigid requirements.

Thankfully, independent factors like Viva still exist and can purchase invoices from businesses at a discount while providing the business with immediate cash. Most businesses qualify for this service even if they don’t qualify for loans because it’s ultimately the customer that pays the balance.

The process is modernized too. For example, businesses that work with a factor like Viva can get approved very quickly, submit invoices for factoring online, and even get paid on the day an invoice is submitted with a transfer directly into their bank account.

A modern factor can also be very instrumental in a business’s growth by offering insights and additional resources, as well as by providing additional forms of funding as business needs change.

Connect with Viva

Founded in 1999, Viva is etched factoring history and continues to help businesses thrive today. If your company needs working capital to fund growth expenses, cope with slow-paying clients, or manage everyday expenses like payroll, Viva can help. Request a complimentary factoring quote to get started.

- Author

- Recent Posts

Director of Business Development and Partner at Viva Capital

Armando Armendariz, Director of Business Development and Partner of Viva Capital, facilitates new business, establishes referral partner relationships and oversees sales—over 15 years of experience in banking, finance, and business entrepreneurship.

Factoring is a word often incorrectly used synonymously with accounts receivable financing. In Europe, the term “factoring” has become the term for accounts receivable financing in general; but in the U.S., this term refers to a specialized form of financing that involves the actual transfer of the ownership of the receivable to the lender, more accurately known as American Factoring. Factoring is a financial transaction whereby a business sells its accounts receivable (i.e., invoices) at a discount. Factoring differs from a bank loan in three main ways. First, the emphasis is on the value of the receivables, not the firm’s creditworthiness. Second, factoring is not a loan but the purchase of an asset (the receivable). Third, a bank loan involves two parties, while factoring involves three.

Parties Involved in Factoring

The three parties involved in a factoring arrangement are the seller, the debtor, and the factor.

The debtor owes the seller money, usually from the purchase of goods or services. It is common in business-to-business transactions for a seller to offer terms that allow payment for goods or services at some time after the actual delivery and acceptance of the goods or services.

Once the client (the debtor) has accepted the goods or services, the resulting obligation to pay the seller (usually represented as an invoice) becomes a negotiable instrument that can be sold.

In factoring, the third party in this transaction, the factor, buys the invoice(s) from the seller, usually at a discount to allow for the factor’s return and with a reserve, which is a margin the factor holds back until the receivable is retired by the debtor. Upon receiving payment on the invoice at its full face value, the factor remits the reserve to the seller.

Misconceptions of Factoring

There are many misconceptions about factoring, although it is an extremely old form of financing. It was first used in the U.S. in the textile industry, which was an industry of small, rapidly growing businesses selling to large retail chains and clothing manufacturers. It was also a common form of financing commerce in England, and some rules for factoring are even found in the Code of Hammurabi, the first set of laws governing commerce in ancient Babylonia.

For more tips on how to improve cash flow, click here to access our 25 Ways to Improve Cash Flow whitepaper.

[box]Strategic CFO Lab Member Extra

Access your Strategic Pricing Model Execution Plan in SCFO Lab. The step-by-step plan to set your prices to maximize profits.

Click here to access your Execution Plan. Not a Lab Member?

Click here to learn more about SCFO Labs[/box]

See Also:

Another Way To Look At Factoring

Accounting for Factored Receivables

Can Factoring Be Better Than a Bank Loan?

Factoring is Not for My Company

Journal Entries For Factoring Receivables

How Factoring Can Make or Save Money

What is Factoring Receivables

The What, When, and Where about Factoring

History of Accounting

Factoring ( Latin factura ‘invoice’ ) is an Anglicism for the commercial, revolving transfer of claims of a company ( supplier , creditor ) against one or more debtors ( debtor ) before the due date to a credit institution or a financial services institution (factor). With real factoring , the receivables are transferred to the factor with the risk of bad debts ; with fake factoring , this del credere risk remains with the supplier. In both cases, the supplier is liable for the legal validity of the claims, i.e. continues to bear the verity risk .

General

The factoring triangle graphically represents the process of open factoring in a company.

The legal three-person relationship in factoring

As a financial service, factoring is a source of finance for medium-sized companies, which is used to finance their working capital. With real factoring you shorten your balance sheet by accounts receivable and payable and improve your liquidity situation and equity ratio . They can also be relieved of the administrative tasks of accounts receivable management. The parties involved are the supplier or service provider (factoring customer, creditor ; this is also called connection customer, connection company or client) who sells his «trade receivables» to a factor (financial service provider or factor bank), and the debtor (debtor; also Third party debtor or buyer) against whom the transferred claim exists.

history

Forerunners of modern factoring can already be found among the Babylonians and Fuggers . When the Swedish economist John Hartman Eberhardt defined the term del credere in 1771 («Del credere is the risk to be taken by the commission agent of the buyer’s creditworthiness or his ability to repay his debts on time»), the factoring process had been practiced for a long time. As early as 1677 there were 38 registered Blackwell Hall factors in London. In the United States, the textile industry began with the first organized factoring transactions in 1890. The modern, systematic form of financing factoring therefore originated in the USA. The first legal regulations concerning the obligation to notify took place here in September 1949. In the USA, factoring is only understood to mean real factoring, while spurious factoring is referred to there as “accounts receivable financing”. Modern factoring came back to England from the USA in November 1960.

In Germany, the first factor contract is to be signed in 1958 by Mittelrheinische Kreditbank Dr. Horbach & Co. KG (Mainz). At that time there was clearly only one German-language publication on the subject. On January 1, 1971, the Deutsche Factoring Bank was founded by seven Landesbanken. The German Factoring Association e. V. was founded in July 1974 and in 2018 had more than 40 members. At first, he and his members were confronted with serious legal obstacles that made it difficult to spread this form of financing. In 2015 around 2,370 factoring institutes worldwide processed sales totaling 2,373 billion euros in 60 countries.

Legal bases

In Germany, the modern factoring, which originated in the USA, began to prevail in 1978 after the Federal Court of Justice had decided two previously unresolved essential legal questions. In the judgment of June 1978, the Federal Court of Justice allowed the conditional buyer of goods to sell and assign his claims from the resale — again — within the framework of real factoring to a factor. The assignment carried out on the basis of sales law would not secure any newly established debts in real factoring, but instead an exchange of assets (claims against cash) would be carried out. The prohibition of assignment, on the other hand, is to be interpreted in such a way that it prohibits the use of cash credit through security assignment in addition to the granted credit. A year earlier, the BGH had already denied the immorality of real factoring due to the collision with advance assignments due to an extended retention of title . Conversely, however, the fake factoring collides with advance assignments, is therefore immoral and is subject to a possible prohibition of assignment. Fake factoring brings factoring customers into the dilemma of either notifying the conditional seller (i.e. their supplier) of the factoring, since their extended retention of title would in this case be ineffective (breach of contract) and thereby the risk of not being supplied or to commit a criminal offense for fraud under Section 263 of the German Criminal Code, since he would have implicitly deceived the factoring company about the fact that he is no longer entitled to the claim due to the extended retention of title. This situation is viewed by the jurisprudence as unacceptable and consequently immoral. If a global assignment or unreal factoring with extended retention of title coincides, the first two means of security are therefore ineffective regardless of the priority principle .

Factoring is not expressly regulated under civil law in Germany and mostly internationally; rather, it is a traffic-typical, non-standardized contract praeter legem ; it is a legal purchase according to § 453 BGB. A legal liability of the seller in factoring results from § 311a paragraph 2 sentence 1 BGB if the sold receivable does not exist, is not transferable or is due to a third party.

A framework contract and subsequent individual implementation contracts are common. The framework agreement regulates the contractual principles between the parties and is usually combined with a global assignment , while the execution contracts contain the specific purchases of receivables and thus the causal transactions for the transfer of claims. If a receivable is sold in the context of factoring, the transaction of disposal of the purchase contract consists in its assignment in accordance with § § 398 ff. BGB. Consequently, the right of assignment also applies, in particular § § 401 BGB (transfer of claims with all ancillary rights ), § 404 BGB (transfer of the claim with objections by the debtor) and § 409 BGB (notification of assignment). In the case of fake factoring , the transaction also consists of the assignment of the claim, but under civil and tax law a loan is generally granted by the factor, who, unlike real factoring, does not assume the del credere or default risk.

In its judgment of June 26, 2003, the ECJ also takes the view that with real factoring the factor assumes the default risk and thus relieves its customers of the risk of non-performance. According to case law, the distinction between purchase and loan is to be made in each individual case on the basis of an overall consideration of the contractual provisions. Similar to the forfaiting of lease receivables , the BFH essentially focused on the assignee’s credit risk. A purchase is to be assumed if the risk of the economic usability of the receivables (credit risk) passes to the purchaser, so there is no possibility of recourse . The payment of the “purchase price” in the case of fake factoring merely represents a mere pre-financing of the claims, the assignment of which is only on account of performance ( Section 364 (2) BGB). In this case, there is a loan relationship.

In the case of an ABS structure , the decisive factor is whether the «originator», as the seller of the receivables, has also transferred the credit risk to the cedant, as is the case with so-called «true sale».

Both real and fake factoring are to be qualified under supervisory law according to Section 1 Para. 1 a No. 9 KWG as financial services that require authorization and supervision. According to the legal definition of Section 19 (5) of the KWG, for the purposes of the millions of credit reports under Section 14 of the KWG, the seller is to be regarded as a borrower when acquiring receivables for a consideration if he is responsible for fulfilling the receivables or if he has to buy them back. That is the case with spurious factoring. With real factoring, the debtor is considered the borrower.

completion

The factor’s fees are usually composed of a factoring fee on sales and interest on the liquidity used . The factoring fee is essentially justified by the customer’s default risk assumed by the factor ( del credere ) from the underlying purchase without recourse and the assumed servicing in the area of accounting and collection . Is called interest condition mostly, according to the average collection period one margin on the 3-month EURIBOR agreed.

The factor forms security deposits to cover deductions by the buyer and verity risks of the receivables. For discounts and other instant deductions such as B. Credits and debits from returns and complaints, a so-called purchase price retention is formed. This is calculated on a daily basis depending on the amount of receivables purchased and is usually between 10% and 20%. There can also be additional withholding for counterclaims by customers and other verity risks such as B. Warranty obligations are formed. These are formed regardless of the amount of the receivables purchased. Examples of customer claims to be mentioned are the payments of annual bonuses or an advertising allowance , which are not offset against the payment of the respective claims.

Core functions and side effects of factoring

The core functions of factoring are the financing, the assumption of del credere and the assumption of services by the factor. On the basis of the purchase of the receivable, the factor usually makes an advance payment of 80 to 90 percent of the receivable amount available to the connection customer (financing function). Through the non-recourse sale of receivables, the risk of default ( del credere ) is transferred to the factor (real factoring, “true sale”). As a result, the seller of the receivables is 100% protected against bad debts. The factor also takes on debtor management for its follow-up customers (full-service factoring). This includes accounts receivable , dunning and debt collection .

As a result of the purchase of the receivables without recourse, they are no longer to be activated in the balance sheet of the factoring customers. With a simultaneous reduction in liabilities, this results in cet. par. overall a reduction in the balance sheet for the factoring customer. With unchanged equity, this leads to a higher equity ratio and thus possibly to a better (bank) rating . With a better classification, factoring can also be used to achieve better credit terms with other lenders .

Composition of the costs in factoring

The costs for factoring are calculated from these parameters:

- Factor Portable Gross — annual turnover

- Financing line (purchased receivables × advance payment ratio)

- number of customers

- Number of invoices

- Scope of the service accepted (full service factoring or in-house factoring)

- If credit insurance is taken over (two-contract model or one-contract model)

- Costs and benefits of the process

In the factoring process, costs arise from the factoring fee, the pre-financing interest rate and the del credere check. The factoring fee is levied on the (gross) turnover and is in the range of approx. 0.25 to 1.0%. The following generally applies: the greater the annual turnover, the lower the percentage fee. For companies with an annual turnover of less than € 2.5 million, the factoring fee can be well over 1.0%.

The pre-financing interest rate is charged on the effective pre-financing period and is also accounted for as required. With a collection period of z. B. 38 days, the interest is due on the advance payment of exactly 38 days. Usual interest rates are between 4.0 and 8.0% and are usually linked to a reference interest rate (e.g. three-month (3M) EURIBOR ). The interest rate tends to be lower, the better the customer’s creditworthiness. The del credere check includes the credit check of the respective debtors. It accrues annually per customer and ranges between € 20 and € 60 per customer and year.

The benefit of the procedure arises from the use of liquidity. By using factoring, there is initially an active exchange (claim for money). The use of liquidity can or should result in the following effects:

If the liquidity is used for discounting in purchasing, then the costs of the procedure are offset by the discount income . The effective interest rate of the factoring process should therefore be lower than the comparable supplier credit . Typical interest rates on a supplier’s credit are between 20 and 60% / year.

The discounting and the repayment reduce the balance sheet total or it shortens the balance sheet. This shortening increases the equity ratio .

Factoring forms according to the scope of services

| Forms according to scope of services | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit check | Delcredere | Pre-financing | Debt collection | |

| Real | j | j | j | j |

| Fake | j | n | j | open |

| Maturity | j | j | n | j |

| In-house | j | j | j | subsidiary |

Real and fake factoring

When factoring a method is known in which the Factor accepts the credit risk. In contrast, factoring without assuming this risk is called spurious factoring . In the case law and literature, fake factoring is predominantly viewed as a loan ; the claim is assigned to secure the credit (i.e. the amount paid for the claim) and at the same time on account of performance (if the claim can actually be collected). In Germany, real factoring is mostly practiced.

Maturity factoring

Factoring variant in which the factoring customer uses the advantages of complete risk protection and the relief of accounts receivable management, but dispenses with the immediate regulation of the purchase price.

In-house factoring (also bulk factoring or in-house service factoring)

The factor limits its services. The accounts receivable including dunning remains with the customer. Only after the out-of-court dunning procedure has been completed is the factor commissioned to collect the claim.

Factoring forms according to the type of assignment of claims

Selection factoring (selective factoring, section factoring)

Normally, the factoring contract includes claims against all customers with a few exceptions. Reasons for exceptions can be: B. counterclaims, fast payers, debtors with a ban on the sale of accounts receivable, customers who work according to VOB or with down payments, private customers or customers abroad. With selection factoring, collaboration is limited in advance to certain customers.

Open factoring (notification factoring)

With open factoring, the customer is informed about the assignment of the claim. Payments on the claim are then generally only possible to the factoring company with the effect of discharging the debt.

Silent factoring

In the case of silent factoring, the customer is not informed about the assignment and sale of the claim; it remains invisible to him. The risk for the factor here lies in the inability to verify the claim, so that a customer with fraudulent intent could offer non-existent claims for purchase. As a result, a factoring company will only work with impeccable addresses in the silent process. If the economic situation deteriorates, the collateral is likely to increase.

Semi-open factoring

With semi-open factoring, the customer is not informed about the assignment of the claim, but is given a payment account or a bank account to which he has to pay and which belongs to the factor. This ensures that the return flow reaches the claim holder as directly as possible.

There are other procedures in semi-open factoring, for example when the debtors pay by check.

Special forms

VOB factoring

In VOB -Factoring is a special solution for crafts and companies in the field of construction-related trade, the Bauausführungen based on contract procedures for construction work filters (VOB). Invoices according to VOB as well as partial and partial payments can thus be factored. In order to compensate for any reimbursements that may arise, which are guaranteed by the procurement and contract regulations for construction work, a special deposit is saved in most cases from the first payments. This special deposit usually accounts for 5-15 percent of the company’s total gross sales.

Individual factoring

There are now financial service providers on the market that offer companies the opportunity to meet their short-term capital requirements by selling individual receivables.

In the case of individual factoring or the sale of individual receivables, the basis of the business is a non-binding and free cooperation agreement. There are no fixed costs, the company decides for itself which receivables to sell. The amount due is transferred within a very short time and immediately improves the company’s liquidity. As with classic factoring, the del credere risk (bad debt risk) and the assumption of collection are included in the financial service provider’s fees. Individual factoring is therefore a flexible and inexpensive financing alternative that is as independent as possible from third parties. The capital previously tied up in receivables is completely free and independent of use.

Rental factoring

A special form of individual factoring is rental factoring in the event of loss of rent . This gives the landlord the opportunity to assign arrears or outstanding rental claims under defined conditions to the factoring company. In return, the landlord receives the purchase price of the receivables. This purchase price corresponds to the amount of the actually existing, open rental claim. The entire risk that the claim can no longer be realized due to insufficient assets is transferred to the factoring company.

Lawyer and tax advisor factoring

From 2005, factoring for lawyers developed in Germany — against the resistance of individual chambers. The first provider was the German Legal Clearing House (AnwVS). A new formulation in § 49b IV BRAO (Professional Code for Lawyers) within the framework of the reform of the lawyers’ remuneration in December 2007 ensured clarity. With a ruling of April 24, 2008, the Federal Court of Justice also confirmed the admissibility of the business model. In addition, amendments to the Tax Advisory Act (Section 64 (2) StBerG) and the Auditor Ordinance (WPO) have given these professional groups the option of factoring. In 2006, DEGEV eG (German cooperative clearing office for tax consultants) was the first to enter the market. The assignment or sale of a client’s fee claim to third parties, such as B. factoring companies or banks. Without the consent of the client, fee claims can be assigned by professionals to professionals, for example by a tax advisor to a lawyer or a law firm.

Reverse factoring

As in the classic procedure, the factor buys and pre-finances receivables from its customers against their customers, but reverse factoring is aimed at the supplier side. In this case, the initiator of factoring is the customer, who in this way benefits from longer payment terms . He concludes a framework agreement with the factoring company in which the factor undertakes to pre-finance the supplier’s claims. The supplier and factoring company for their part then sign a supplementary contract which only includes the claims against the initiator. The factoring company transfers the corresponding amount to the supplier.

With reverse factoring, there is also the possibility that the factor takes on the del credere risk. In this case, the model is often called «Confirming», an expression that has meanwhile been seized by the Santander Bank and is used as a brand name for a corresponding own product.

Reverse factoring helps small and medium-sized companies in particular to design flexible payment terms that are strategically important in purchasing. International reverse factoring has become an important payment instrument in foreign trade developed, in part, in place of the letter of credit ( letter of credit is entered) because it is easier and less time-consuming to handle and (in the case of Confirming offers) similar safeguards.

The reverse factoring model emerged around 20 years ago in Spain under the name Pago Certificado («certified payment») and has grown worldwide with the strong international expansion of the major Spanish banks in recent decades, particularly in Latin America and southern Europe spread. It is particularly useful if the initiator (importer) comes from a country in which very long payment terms are usually granted (in Spain, for example, 3 to 6 months are common), which the supplier (e.g. a German company) due to the in his Country can hardly accept customary business practices. With classic confirmation , the supplier can often choose whether he would like to trust the payment commitment from the bank or factoring institute, which is usually located abroad (importing country), or whether he would prefer to receive an abstract security related to the factor , which he can obtain from any bank in the own country can redeem.

Reverse factoring is often confused with finetrading . However, the two alternative forms of financing differ structurally as well as economically and legally, as the table below shows.

| differences | Finetrading | Reverse factoring | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structurally | Users | The customer is the user | Buyer is user (initiator) |

| implementation | Fast implementation, as no credit check of the supplier is necessary | Long implementation, since credit checks are absolutely necessary for every supplier | |

| flexibility | Given because the limit can be used for any supplier; Free choice of whether purchasing is processed via finetrading | Not given, as the total limit must be divided up for each supplier beforehand and the obligation to process via factor within the limit | |

| Business economics | Financing period | Max. Up to 120 days, repayment to the day | Max. Up to 180 days, fixed repayment |

| Volumes | Even small purchasing volumes are possible (from € 100,000), aimed at SMEs | Higher purchasing volumes (from € 10 million) are more aimed at large companies | |

| costs | I. d. R. Capital costs at 10% | I. d. Usually cheap, as approx. 1–3% above Euribor | |

| Legal | contract | 1 contract:

Framework agreement between finetrader and buyer |

2 contracts:

Factoring contract with the supplier and factoring contract with the buyer including counter-signature by the supplier |

| property | Finetrader acquires ownership of goods | Factor acquires ownership of the claim | |

| BaFin | Trading business, therefore not subject to BaFin (Section 1 KWG) | Financial services , therefore subject to BaFin (§§ 1 Para. 1 a No. 9, 32 KWG) |

Comparison of factoring and asset-backed securities

Both factoring and asset-backed securities are receivables-based corporate financing. The main differences can be shown in a table as follows:

| criteria | Factoring | Asset-backed securities |

|---|---|---|

| Refinancing | Refinancing through the credit market | Issuance of securities |

| Company turnover and volume of receivables | Annual turnover> 100,000 EUR | Accounts receivable> EUR 5 million |

| Terms of the claims | Duration of usually a maximum of 90 days | Securitization also for medium and long-term receivables |

| Del credere | 100% assumption of the default risk with real factoring | Part of the default risk remains, e.g. B. via first-loss regulations at the seller of the receivables |

| Transaction cost | Low structuring and fixed costs compared to ABS transactions | High one-time and fixed costs |

| Debt review | Individual examination of the receivables to be purchased | No individual examination of claims. Use of empirical values and statistical evaluations. |

| Accounts Receivable Management | Possibility of outsourcing accounts receivable management as part of the service function to the factor | I. d. R. Remaining of the accounts receivable management with the accounts receivable seller |

| Duration of implementation | Implementation usually within a period of 1 — 3 months | Lead time of up to 6 months |

| running time | Term of up to 24 months | Duration usually of 5 or more years. |

| Disclosure | Notification of the sale of the receivables by the debtor («open factoring») | Quiet proceedings without notice |

| Debt concentration | usually up to a maximum of 30% | between 3% and 5% |

Differentiation between factoring and forfaiting

A forfeiting includes certain receivables contractually concretely, is therefore legally species purchase to qualify. Factoring, on the other hand, also relates to the purchase of receivables that arise later, that are still unknown at the time the contract is concluded and also mostly rather short-term receivables.

Risk of fraud

Factoring and forfaiting are subject to the risk that receivables that do not even exist are sold and assigned to the factor or forfaiter. Admittedly, these risks are part of the debt seller’s liability, but they are ineffective if he has used the purchase price proceeds for other purposes with criminal intent. Spectacular cases of fraud in factoring (especially Balsam AG ) have caused great damage because these forms of financing make it easier to sell bogus receivables. Balsam AG had invented claims in 1993 «simply in order to obtain liquid funds by selling them to Procedo GmbH .» The fraud was noticed in June 1994. FlowTex sold drilling machines, 85% of which did not exist, on a sale-lease-back basis . Factor or forfaiter must therefore permanently ensure through suitable control measures that there is no verity risk for them. In particular, balance confirmations or acknowledgments of debt can be obtained from the debtor .

See also

- Credit crunch

- Payment terms

- Payment history

Web links

- Information on factoring from the German Factoring Association e. V.

- Information on factoring from the Federal Association of Factoring for SMEs

- Information on factoring from the Swiss Factoring Association

- Leaflet — Notes on the factoring of the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority

Individual evidence

^ David B. Tatge, Jeremy B. Tatge: The History of Factoring. (Excerpt from the book American Factoring Law , Bureau of National Affairs, 2009, ISBN 978-1-57018-792-6 ) In: International Factors Group Newsletter , April 28, 2011, p. 3 ( ifgroup.com ( page no longer retrievable , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this note. (PDF) Page no longer retrievable «del credere is the undertaking on the part of a commission agent to assume responsibility for the credit worthiness of the buyer or his ability to liquidate his debt on the due date «

- ^ David B. Tatge, Jeremy B. Tatge: The History of Factoring. (Excerpt from the book American Factoring Law , Bureau of National Affairs, 2009, ISBN 978-1-57018-792-6 ) In: International Factors Group Newsletter , April 28, 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Herbert R. Silverman: Harvard Business Review. September 1949

- ^ Sigrun Scharenberg: The accounting of beneficial ownership in the IFRS accounting. 2009, p. 140 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ David B. Tatge, Jeremy B. Tatge: The History of Factoring. (Excerpt from American Factoring Law , Bureau of National Affairs, 2009, ISBN 978-1-57018-792-6 ) In: International Factors Group Newsletter , April 28, 2011, p. 26.

- ^ Sven Tillery: Financial assessment of factoring contracts. 2005, p. 2 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Cash in the till . In: Der Spiegel . No. 25 , 1965, pp. 64 f . ( online ).

- ↑ G. Knopik: Factoring — New ways of sales financing. In: Journal for the entire credit system , 1957, p. 61 ff.

- ↑ For many still a foreign word — factoring bank has offered a modern financing instrument since 1971. In: Weser-Kurier , January 15, 1996, p. 5

- ↑ Annual Report 2015 (PDF) Deutsche Factoring Bank, p. 4.

- ^ BGH, judgment of June 7, 1978, Az .: VIII ZR 80/78

- ^ BGH, judgment of September 19, 1977 = BGHZ 69, 254

- ^ Sigrun Scharenberg: The accounting of beneficial ownership in the IFRS accounting. 2009, p. 137

- ^ Sigrun Scharenberg: The accounting of beneficial ownership in the IFRS accounting. 2009, p. 142

- ↑ Hildrun Siepmann: Deductibles for securitisations. 2011, p. 57

- ^ Jost W. Kramer, Karl Wolfhart Nitsch: Facets of corporate financing. 2010, p. 246

- ↑ Hartmut Oetker, Felix Maultzsch: contractual obligations. 2007, p. 61

- ^ Hans Georg Ruppe: Commentary on the sales tax law. 2005, p. 149

- ↑ ECJ, Az .: C -305 / 01Slg I-6729

- ↑ BFH, judgment of November 8, 2000 IR 37/99, BFHE 193, 416, BStBl II 2001, 722 with reference to the judgment of the BGH of June 21, 1994 XI ZR 183/93, BGHZ 126, 261, 263

- ↑ BGH, judgment of October 14, 1981 VIII ZR 149/80 = BGHZ 82, 50

- ^ Opinion of the Institut der Wirtschaftsprüfer on questions of doubt regarding the accounting of asset-backed securities arrangements and similar transactions [IDW RS HFA 8] in the version of December 9, 2003, Die Wirtschaftsprüfung 2002, 1151 and 2004, 138 Item 7 ff.

- ↑ Marcus Creutz: New clearing house for lawyers’ fees started . handelsblatt.de. January 26, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ Marcus Creutz: Chamber takes action against collection agency for attorney’s fees . handelsblatt.de. March 10, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Court of Justice of April 24, 2008 (Az. IX ZR 53/07)

↑ Claudia Bannier: The liability problems under the law of obligations and bill of exchange law in the forfaiting of export claims. ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.3 MB) 2005, p. 9

- ↑ Marc Albertus: The reimbursement claim from § 31 Abs. 1 GmbHG after restoration of the share capital. (PDF; 1.5 MB) 2004, p. 23 ff.

- ↑ Marc Albertus: The reimbursement claim from § 31 Abs. 1 GmbHG after restoration of the share capital. (PDF; 1.5 MB) 2004, p. 23

- ↑ BGH, judgment of November 10, 2004, Az .: VIII ZR 186/03

Get Started, Call Today

A History of Factoring

Freight Broker

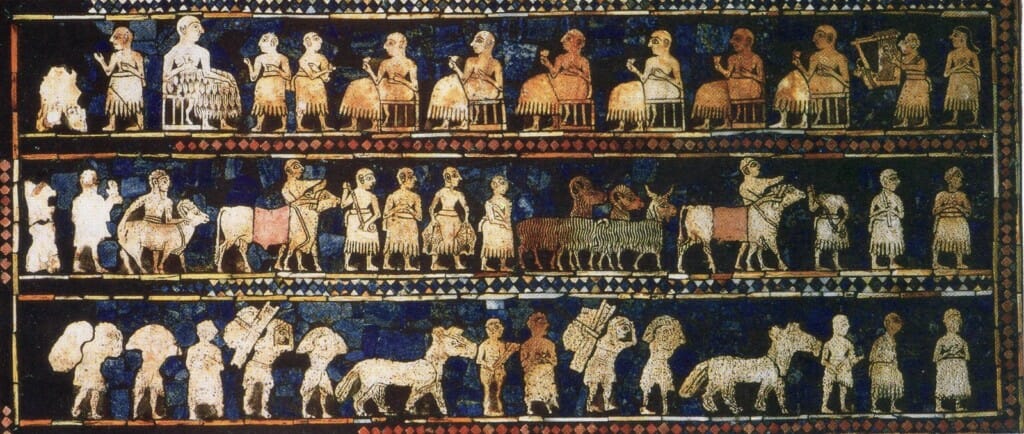

The concept of factoring is thought to trace back thousands of years to ancient Mesopotamia. For some this history may be surprising, however, if you know the history of this region, they were believed to be responsible for advancement in many of the areas of academic study and industry that our world still greatly depends on to this day. These include writing, advanced mathematics, astronomy, law and quite honestly the confines of civilization itself. Even the names of the days of the week that we use today are thanks to the Mesopotamians, but I digress.

(*Mesopotamian art depicting the barter system.)

So where do we see the historical traces of factoring come into play here? Well, at the time Mesopotamia did not have a vast amount of natural resources; at least not the ones that were in popular demand at the time. Therefore, they had to establish methods of trade with neighboring areas who did have the resources they desired such as different foods, clothing, jewelry, wine as well as other goods.

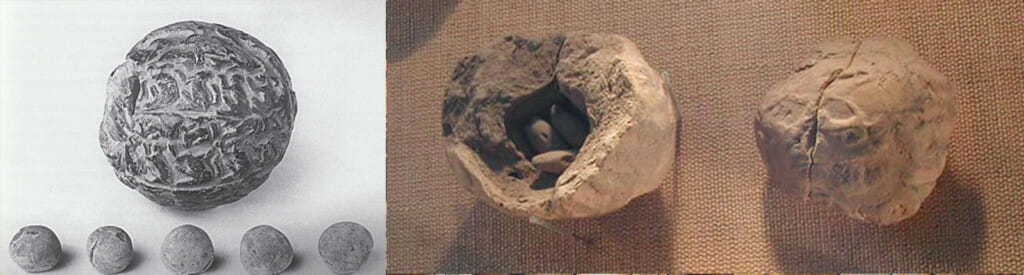

(*Clay ball and tokens used for bartering.)

When trade ships came in it was always a time of great celebration. Bringing in orders that had previously been placed from areas to the North or the East, while others would place future orders for the next time the ships returned. The Mesopotamian merchants were experts of barter and would use clay tokens as a form of contract or invoice, imprinted with intricate symbols describing what they were offering and what was expected as payment in return. These symbols were designed in a unique manner where one symbol might mean a chair, or even a fancy chair, while another meant a bag of fruit. These tokens were placed in a clay ball and upon return with the items, the ball was opened and tokens compared to the goods to ensure what was ordered has been received as agreed upon before payment.

(* Mesopotamian symbols featuring symbol used for barley.)

Barley was commonly used as an acceptable form of payment. For those that did not have the barley available, it could be borrowed from a “barley banker” who charged and interest rate for advancing it to them. Due to the weight of barley, when trading away from home items like gold and silver were used with the same concept as barley.

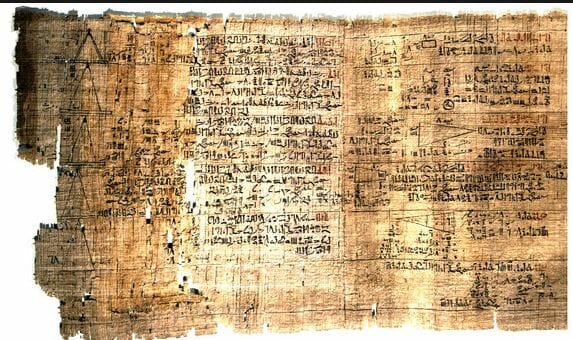

(*Egyptian finances documented on a sheet of papyrus.)

Jumping forward in time, we find records in ancient Egypt written on papyrus in which we see evidence of similar transactions taking place using this form of factoring. Traces can also be found during this time period in ancient Greece as well. During the Roman era, we continue to see this model of factoring being used with advancements. Introducing the first collection specialists, who received a commission of up to one percent of the money collected. This concept was then spread from the Romans throughout Europe as their empire grew.

The term “Factoring” actually originates from the Latin root word, “Facere” meaning to make, do, accomplish; to become.

(*Statue in the likeness of Jacques Couer, Financial Minister for King Charles VII.)

Additionally, we start to see communities of “factors” appear around England and France during the 13th and 14th centuries, as well as the “factors” of Blackwell Hall in London, who operated as agents for the woolen trade. Not to mention that Jacques Couer, King Charles VII’s Finance Minister, led his 300 “facteurs” to far-off lands to trade as well.

Factoring arrived in this area with the Pilgrims after the voyage of the Mayflower in the 17th Century, when the era of common law factoring began in America. The Plymouth Company invested in the colony prior to the Mayflower even setting sail. These debts were to be paid back with interest over a term of seven years. These practices continued and were later elevated into the modern factoring we know today.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Page load link

Businesses have long needed the ability to raise funds. In fact, as long as trading and commerce has existed, there has been the need to raise funds to fuel product purchases and to meet expenses before clients pay their bills. Factoring is one of the most ancient, long-lasting forms of funding. Here is a bit about its history.

Factoring in Ancient Times

Ever heard of the Code of Hammurabi? It is a code of laws set down by the sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, in the 18th century B.C. Part of the Code sets down rules for merchants who wanted to use factoring as a form of funding.

As civilization developed, other forms of financing began to form. Factoring, however, remained a major funding option. Ancient Roman merchants used agents to guarantee trade credits. These agents became known as «factors». The term factoring and factoring have come forward to modern times.

The Development of Modern Factoring in Medieval Europe

The rules and forms of modern factoring began to form in Medieval Europe. As trade began to increase, the need for different forms of funding increased as well.

Religious usury laws prohibited Christians from charging excessive fees for lending money. Jewish agents filled the gap when it came to high risk ventures that needed higher interest rates. They would provide cash advances to farmers and merchants, with the harvest or profits being held as collateral. These agents were the precursors to modern investment bankers.

The practice of factoring continued to develop and mature as Medieval Europe emerged into the Renaissance.

Factoring as a Colonial Funding Option

By the time the American Colonies were founded, factoring had long been a form of financing for European merchants. The practice came to the New World along with commerce and trade. The use of merchant agents to finance shipments of raw materials between the Colonies and Europe became common practice.

A merchant agent would factor shipments going from Europe to the Colonies. The agent would take physical possession of the goods at the origin and take it to the place of sale. After the goods were sold, the merchant agent would take a small percentage before turning the profits over to the seller.

Eventually, the agents stopped taking part in the physical movement of goods. Instead, they started financing and insuring the credit. This is when focus turned on ensuring that the buyers were creditworthy. Factors started guaranteeing payment from creditworthy customers.

The Growth of Factoring in the New Nation

Factoring continued to evolve in the late 18th and into the 19th century. Factors started venturing into new areas including selling crops, purchasing goods and handling shipments of raw goods to market.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the growth of the textile industry fueled the growth of factoring. In fact, it became a major source of funding in areas where banks were limited by law into how much money they could lend. Factors did not have those restrictions. This freedom attracted other industries like transportation and freight forwarding. Many businesses in these specialty areas continue to use factoring for their funding needs.

The use of factoring became less prominent as the era of credit cards and lines of credit emerged in the post-WW2 era. However, it returned to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s when interest rates soared.

Factors today offer thousands of businesses the ability to gain the cash they need to grow and to operate from day-to-day without cash flow issues. They provide credit analysis of customers, maintain the accounts receivable ledger, and manage collections.

Factoring has evolved as times have changed. However, one thing has remained the same. Factoring remains a respectable viable financing option for businesses of all sizes and in most industries. Can you use factoring in your business?