© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

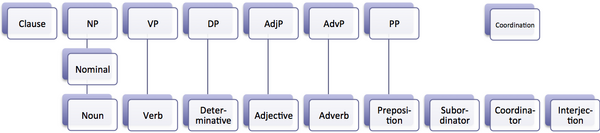

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

Martin Haspelmath

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

While looking at a range of views by grammarians on word-class distinctions (noun, verb, adjective etc.) and word division in two recent papers (Haspelmath 2011; 2012a), I was struck by what appears to have been a major shift of perspective: While the first half of the 20th century emphasizes the uniqueness of languages and the categorial differences between them, the second half starts out from the assumption that languages do not differ in their basic categories. (Elsewhere I called this distinction categorial particularism and categorial universalism; Haspelmath 2010.) There are some signs that the perspective adopted in the first half of the 20th century is now getting more attention again.

Earlier history

Let us start with some earlier history. According to standard accounts, language thinkers in the 17th and 18th centuries did not show particular interest in structural differences between languages. Even though Western scholars became better and better acquainted with some of the major Oriental languages during this period, the prevailing approach among grammarians and philosophers of grammar was to (try to) use the same concepts for all languages, and to assume that categories such as “noun”, “verb”, “preposition”, as well as “word” or “root”, were cognitively grounded and hence could be applied universally. In textbooks on the history of linguistics, this view is particularly associated with the grammaire générale tradition. Thus, according to Robins (1997: 141), in the Port Royal grammar, “the six cases of Latin are … assumed in other languages, though some of them were expressed by prepositions and word order”. But even though the spirit of Renaissance linguists in the 16th century may have been somewhat different, emphasizing the peculiarities of the modern European languages (e.g. Ramée’s recognition that nouns in French are recognized by number rather than by case), the classical teaching of nine parts of speech was rarely questioned (pronoun, noun, verb, participle, adverb, article, preposition, conjunction, interjection).

The 19th century gradually brought some changes, also influenced by the wider cultural movement of Romanticism. Languages were no longer thought to be mere expressions of human thinking, but different languages were often considered as manifestations of different worldviews and different cultural predilections of their speakers. This did not lead to very striking innovations in grammatical practice, and of course most grammarians were interested in the prestige languages Latin, Greek, German, French, etc. Serious interest in non-(Indo-)European languages among general linguists became widespread only in the 20th century. However, some 19th century linguists did observe that non-Indo-European languages are organized rather differently with respect to their word-classes (or “parts of speech”, using a calque from Latin partes orationis). In particular, linguists observed that some languages such as Hungarian and Turkish had conjugation-like person markers on their nouns as well as on their verbs, and they hinted that these languages did not make the same kind of sharp distinction between nouns and verbs.

Similarly, scholars began to doubt that the notion of “word” is universal. I am not aware of any doubts of the universality of the word in the 19th century, but the foundational concept “morpheme”, which makes the word less important than it was in the past, was coined by Jan Baudouin de Courtenay in 1880 (cf. Mugdan 1986). Moreover, the distinction between “agglutinative” and “flective” languages, which points to rather different word-building principles in different languages, goes back to the early 19th century (Friedrich von Schlegel and Wilhelm von Humboldt, cf. Greenberg 1974).

Particularism in the 20th century

In the first half of the 20th century, such (categorial particularist) views became mainstream. Franz Boas is particularly well-known for emphasizing that North American languages should not be squeezed into the Procrustean bed of European categories, that the categories chosen for description “depend entirely on the inner form of each language”, and that languages should be described “in their own terms” (Boas 1911). Otto Jespersen described English in a way that highlighted its “progress” over the ancient, more cumbersome languages, and along the way Jespersen coined a fair number of new terms for concepts of English grammar (e.g. extraposition, adjunct). Bloomfield (1933) noted that articles, demonstratives and possessives formed a single substitution class in English and created the new “determiner” category for them. A less well-known figure is Erich Drach, who first described German sentence structure in terms of a template consisting of a prefield, a left bracket, a middle field, a right bracket, and a postfield (Drach 1937). In main clauses, the auxiliary and the main verb occupy the left and right bracket, respectively, while the filling of the prefield is relatively free. This model of German sentence structure is still used by German syntacticians today (e.g. Müller 2010).

The Leningrad linguist Lev V. Ščerba described Russian syntax in the 1920s using a completely novel category, the “state category” (in Russian kategorija sostojanija), e.g. lexical items such as vidno ‘one can see’, bol’no ‘it hurts’, dosadno ‘it is annoying’. These are predicative words that are in some ways like adjectives or adverbs, but they occur only predicatively, like verbs, and some of them can even take objects. In his last paper, Ščerba (1945: 186) demanded that underdescribed languages should be studied “concretely, without seeing them through the prism of the researcher’s native language, or another language with a traditional grammar, which distorts the grammatical reality…” Thus, by this time Western linguists had emancipated themselves from the tradition of antiquity. Even though they still used many of the old terms, they became used to asking for justification before applying a traditional concept, and they were willing to posit novel concepts, and to recognize certain categories as unique to particular languages. This approach to language structure became known as “structuralism” in the second half of the century. Whereas 19th century linguists invested most of their efforts into elucidating historical relationships between languages, the study of individual synchronic language systems began to take centre stage in the 20th century.

One accompanying feature of this activity was the coining of new terminology, of which a few examples are given above. When each language has its own categories, in principle one would need new terms for each language. And indeed, we do find some thoroughly language-specific terminology such as “middle field”, “determiner” and “state category”.

What’s in a word

The first half of the 20th century also saw people asking for justification of the “word” concept, apparently for the first time. While the morpheme was easy to define (as a minimal sign, a minimal combination of form and meaning), it turned out that the word was more difficult to characterize. Bloomfield (1933: 178) attempted to define the word as “a minumum free form”, but this definition was not widely adopted, and some researchers doubted whether all languages had words. Thus, Hockett (1944: 255) claimed that “there are no words in Chinese”, and Milewski (1951) made similar remarks about North American languages. In the closing session of the 6th International Congress of Linguists, held in Paris in 1948, congress president Joseph Vendryes remarked that modern linguistics was in a crisis, and that linguists were not even in agreement on what a word is, one of the fundamental concepts of their object of studies (cf. Togeby 1949: 97; Haspelmath 2011: 71). The basic problem was that linguists did not find a good way to justify the distinction between affixes (prefixes and suffixes) and short function words (often clitics). It was often observed, for instance, that French subject person forms (je viens, tu viens, il vient, etc. for the verb ‘come’) behave like prefixes, even though they are written separately. Likewise, compounds and phrases are often impossible to tell apart (is French chemin de fer [path of iron] ‘railway’ a compound word or a phrase?).

Doubts about the universality of the “word” concept were very widespread in the structuralist period. Schwegler (1990: 45) summarizes his detailed overview of the view of this period:

After generations of 19th- and 20th-century linguists had taken the ‘word’ largely for granted, structuralists set out to define what in popular as well as in scientific circles was regarded as the basic unit of speech . . . this lively discussion eventually led to the now generally accepted conclusion that (a) the ‘word’ cannot be defined by a single (or for that matter, multiple) common denominator, and (b) not all segments of speech are ‘words’ in the proper sense of the term.

The more optimistic linguists of this period claimed that while there was no universally applicable definition of the word, words could be defined by language-specific criteria. Thus, Bazell (1958: 35) noted: “Now there is perhaps no unit over which there is less agreement than the word. If there is any agreement at all, it is that the word has to be differently defined for each language analysed.”

Thus, we see great efforts being made in the first half of the century (the structuralist period) to carefully define the categories that are used for description and to justify them for each language individually. In principle, this is still what our textbooks teach our students. But the practice of the second half of the 20th century was very different.

Generative universalism

In the wake of Chomsky (1957), linguists increasingly lost interest in the question of how to justify categories. The focus was now on stating rules formally, on rule interactions (derivations), and on the relations between “underlying structures” and actual forms. But the new enterprise of transformational grammar was at the same time intended as a way of explaining the possibility of language acquisition despite the poverty of the stimulus, and the proposed solution was the innate universal grammar. On this view, categories (or at least their constitutuent features) were thought to be universal.

Now one might have expected linguists to embark on an empirically grounded research project asking what these presumed universal categories are. Perhaps surprisingly, nothing of this sort happened. Linguists simply abandoned the practice of seeking the best categories for different languages and justifying them. Instead, they focused on their new tasks of expressing generalizations through abstract representations and ignored the insights of their structuralist predecessors. Since the late 1960s, students were increasingly discouraged from reading the earlier literature, so the categorial particularism of the structuralist period was largely forgotten. Instead of coming up with a new original set of categories, they fell back on what the school grammars offered all along: the traditional concepts inherited from Priscian and Donatus through the Middle Ages and the early modern era.

Nouns, verbs and adjectives

When Chomsky’s proposals from the 1960s were extended to other languages, few linguists proposed word-classes other than those used by Chomsky for English. And these were all very traditional. In his 1970 paper “remarks on nominalization”, Chomsky proposed that the four categories N (nouns), V (verbs), A (adjectives) and P (prepositions) were universal, mostly on the basis of a few observations on English. There was little discussion of other possible categorizations in the subsequent decades, and Baker (2003) essentially confirmed Chomsky’s views, using data from a wide variety of languages (but leaving aside prepositions, which are grammatical rather than lexical words).

When Miller (1973) discussed the phenomena that had led Ščerba a few decades earlier to posit a new category for Russian (as mentioned above), his wording was characteristic of the new thinking of the generative era:

Many [Soviet linguists] have supposed that it was necessary to set up another part of speech, the “category of state”… The traditional Soviet account is not very satisfactory, since one either has to accept a new part of speech or some loose ends in one’s taxonomy… It will be assumed in this paper that verbs and adjectives are surface-structure categories which derive from a single deep-structure category which will be called Predicators.

The positing of a new category was not considered an insight into the peculiar nature of Russian, but as a defect of the description that was to be remedied. Characteristically, instead of justifying his categories, Miller starts by making assumptions and then builds an analysis on these assumptions.

While the first half of the 20th century saw a lot of new terms coined by linguists, the generative era adopted a very different approach: The use of new terms for categories was limited, and the main way in which conceptual innovations could take place was by giving new meanings to existing terms (e.g. government, Fillmorean or Chomskyan case, adjunct, complement).

An interesting recent paper on word-classes is Chung’s (2012) study of Chamorro, which concludes that Topping’s (1973) earlier (structuralist) account in terms of two main classes (class I and class II), which differ radically from the familiar European classes, could be reanlyzed in terms of the familiar categories, V, N, and A. Topping set up two large classes mainly on the basis of the expression of the pronominal subject: Class I, comprising transitive action words, and Class II, comprising intransitive action words, property words, and thing words. Chung notes that Class II is not quite internally homogeneous, and that transitive and intransitive action words behave alike syntactically in some ways. Thus, if one wants, one can say that Chamorro has nouns, verbs and adjectives like English, even though Topping’s Class I vs. Class II division is more salient if one leaves English aside (as he did). Chung inserts her proposal for analyzing Chamorro in the context of the general discussion of word-class universality, but she does not seem to realize that the idea of the universality of V, N and A is derived from the tradition of English grammar since the 18th century (before that, nouns and adjectives were actually not clearly distinguished, following the Latin tradition of Priscian and Donatus). It is true that in many languages, one can draw similar distinctions if one wants, but one could probably also find such evidence for a Class I vs. Class II distinction and argue that it is the Chamorro distinction that is universal (cf. Haspelmath 2012b).

The word as a universal category

The word was never discussed seriously by Chomsky, and in fact the mainstream generative literature both of the 1960s and of the 21st century tends to assume that there is no strict division between words and phrases, and between morphology and syntax. However, between the 1970s and the 1990s, a very widespread view was that the word (or the lexicon) represents an important level of analysis, and that lexical and syntactic rules are quite distinct (this is called lexicalism; e.g. Anderson 1992; Bresnan & Mchombo 1995). Curiously, lexicalists never say what they mean by a word and how they identify it. In particular, they do not say how they might distinguish clitic words from affixes, and phrases from compound words, in a way that works across languages.

In this regard, lexicalism reminds one of the pre-structuralist time, when the word concept was simply taken for granted and not seen as a problem. It is striking that textbooks of the structuralist era usually include a lengthy discussion of how to delimit words (e.g. Hockett 1958; Gleason 1961), while more recent textbooks say very little about identifying words (the last general linguistics textbook with a long discussion was Langacker (1972), apparently still under the influence of structuralist particularism). But what happens if one simply pretends that words are universal, without saying how they can be identified universally? As in the case of nouns, verbs and adjectives, in practice this means that linguists go back to the traditional views of our school books. And traditionally, the word is regarded as a string of letters between spaces. As I showed in Haspelmath (2011), there is no other word identification procedure that linguists were able to rely on.

Of course, if one assumes that the categories of languages are given in advance (i.e. that we are born with them), there is no need to define them, anymore than we need to define other natural kinds such as potassium, dandelion or kidney (cf. Haspelmath 2014 on the distinction between defining and diagnosing categories). However, one needs to be aware that in practice that may mean that the consensus converges on the categories that we have been familiar with since our school days.

Reconciling particularism and universalism in the 21st century

While Greenbergian typology of the 1960s and 1970s seemed to be similarly universalist in outlook to the generative paradigm (and was thus embraced by many Chomskyans in the 1980s and 1990s, e.g. Baker 2001), more recently many linguists coming from the Greenbergian tradition have made clear statements advocating a return to particularist views when it comes to describing individual languages (Dryer 1997, Croft 2001, Lazard 2006, Haspelmath 2007). Interestingly, some of them are probably continuing structuralist views that they always held, influenced by pre-generative structuralists. (Thus, Dryer was a student of H. Allan Gleason’s at the University of Toronto in the 1970s, and Lazard was a student of Émile Benveniste’s in Paris in the 1940s and 1950s.)

But have these people been arguing for a return to the older practice of concentrating exclusively on language-specific system, to the exclusion of cross-linguistic generalizations? Not at all: The particularism concerns language-specific analyses, but this is not incompatible with (even large-scale) cross-linguistic comparison. One just needs to realize that grammatical comparison does not start out from language-specific categories, but from comparative concepts that are quite distinct from descriptive categories (Haspelmath 2010). Grammatical comparison is thus not different from lexical comparison (e.g. Swadesh lists) – everyone recognizes that word meanings in different languages cut up the conceptual space in different ways, but we still compare words across languages.

Thus, when comparing languages with respect to nominal, verbal and adjectival behaviour, we just need to look at thing words, action words and property words. These can be readily identified across languages, and interesting comparisons can be made (Haspelmath 2012a). In effect, a Greenbergian word-order universal concerning adjective-noun order refers to the order of property words and thing words. Likewise, when comparing languages with respect to words vs. affixes, one needs to work with comparative concepts that work across languages, such as grammatical morph vs. lexical morph (Haspelmath 2014), mobile vs. fixed grammatical morph, etc.

Thus, there is no need to abandon the structuralist concern for language-internal justification of categories, or large-scale cross-linguistic comparison. Once one recognizes that these are different enterprises, both can continue as originally envisaged.

References

Anderson, Stephen. 1992. A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark C. 2001. The atoms of language. New York: Basic Books.

Baker, Mark C. 2003. Lexical categories: verbs, nouns, and adjectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bazell, C. E. 1958. Linguistic typology: An inaugural lecture delivered on 26 February 1958. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. New York: H. Holt and Company.

Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction. In Franz Boas (ed.), Handbook of American Indian Languages, 1–83. Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology.

Bresnan, Joan & Mchombo, Sam M. 1995. The lexical integrity principle: evidence from Bantu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13: 181-254.

Chomsky, Noam A. 1957. Syntactic structures. ’s-Gravenhage: Mouton.

Chomsky, Noam A. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In R.A. Jacobs & Peter S. Rosenbaum (eds.), Readings in English transformational grammar, 184–221. Waltham, MA: Ginn.

Chung, Sandra. 2012. Are lexical categories universal? The view from Chamorro. Theoretical Linguistics 38(1-2). 1–56. doi:10.1515/tl-2012-0001 (17 September, 2012).

Chung, Sandra. 2012. Are lexical categories universal? The view from Chamorro. Theoretical Linguistics 38(1-2). 1–56. (doi:10.1515/tl-2012-0001)

Croft, William. 2001. Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drach, Erich. 1937. Grundgedanken der deutschen Satzlehre. Frankfurt am Main: Diesterweg.

Dryer, Matthew S. 1997. Are grammatical relations universal? In Joan L. Bybee, John Haiman & Sandra A. Thompson (eds.), Essays on language function and language type: Dedicated to T. Givón, 115–143. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Gleason, Henry Allan. 1961. An introduction to descriptive linguistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1974. Language typology: A historical and analytic overview. The Hague: Mouton.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2007. Pre-established categories don’t exist: consequences for language description and typology. Linguistic Typology 11. 119 – 132.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2010. Comparative concepts and descriptive categories in crosslinguistic studies. Language 86(3). 663-687.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2011. The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax. Folia Linguistica 45(1). 31–80.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2012a. How to compare major word-classes across the world’s languages. In Thomas Graf, Denis Paperno, Anna Szabolcsi & Jos Tellings (eds.), Theories of everything: in honor of Edward Keenan, 109–130. (UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics 17). Los Angeles: UCLA.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2012b. Escaping ethnocentrism in the study of word-class universals. Theoretical Linguistics 38(1-2). doi:10.1515/tl-2012-0004.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2014. Defining vs. diagnosing linguistics categories: A case study of clitic phenomena. In Joanna Błaszczak (ed.), Categories. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Hockett, Charles F. 1944. Review of Linguistic interludes and Moprhology: The descriptive analysis of words (1944 edition) both by Eugene A. Nida. Language 20.252-255.

Hockett, Charles F. 1958. A course in modern linguistics. New York: MacMillan.

Langacker, Ronald W. 1972. Fundamentals of linguistic analysis. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Lazard, Gilbert. 2006. La quête des invariants interlangues: La linguistique est-elle une science?. Paris: Champion.

Milewski, Tadeusz. 1951. The conception of the word in languages of North American natives. Lingua Posnaniensis 3: 248–268.

Miller, Jim. 1973. A generative account of the “category of state” in Russian. In Ferenc Kiefer & Nicolas Ruwet (eds.), Generative grammar in Europe, 333–359. (Foundations of Language 13). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Mugdan, Joachim. 1986. Was ist eigentlich ein Morphem? Zeitschrift für Phonetik, Sprachwissenschaft und Kommunikationsforschung 39: 29-43.

Müller, Stefan. 2010. Grammatiktheorie. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Robins, R. H. 1997. A short history of linguistics. London: Longman.

Ščerba, Lev V. 1945. Očerednye problemy jazykovedenija. Izvestija Akademija Nauk SSSR 1945.4(5): 173-186.

Schwegler, Armin. 1990. Analyticity and syntheticity: a diachronic perspective with special reference to Romance languages. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Togeby, Knud. 1949 [1978]. Qu’est-ce qu’un mot? In Michael Herslund, ed. Knud Togeby: Choix d’articles 1943–1974. Copenhagen: Akademiske Forlag, 51–65.

Topping, Donald. 1973. Chamorro reference grammar. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

How to cite this post

Haspelmath, Martin. 2014. (Non-)universality of word-classes and words: The mid-20th century shift. History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences. https://hiphilangsci.net/2014/10/08/non-universality-of-word-classes-and-words-the-mid-20th-century-shift

1. Problem and history

Does the frequency of different word classes abide by a special distribution law? Evidently, word classes are nominal entities, thus they must be ranked (see Ranking →). Historically, word classes represent the diversification of an amorphous word stock which began to be partitioned by the development of grammar, thus this is a problem of diversification (→).

The first investigations have been performed by Hammerl (1990) who obtained the Zipf-Alekseev distribution, just as Schweers, Zhu (1991) did. Köhler (1991) studied the problem from the diversification point of view. A number of individual studies on texts in German (Best 1994, 1997, 2000, 2001a, b; Judt 1995), Russian (Bosselmann 2001), French (Judt 1995), Latin (Schweers, Zhu 1991) Chinese (Zhu, Best 1992, Schweers, Zhu 1991), Czech (Uhlířová 2000) and Portuguese (Ziegler 1998, 2001) has been performed and brought different results. The word classes were considered in their classical version, nobody tested other possible classifications. Statistical tests for word classes have been set up by Wimmer and Altmann (2001).

The hypothesis concerning word classes is merely a special case of a more general hypothesis encompassing any kind of classes of linguistic entities.

2. Hypothesis

If language entities are ordered in classes, then their ranked frequencies follow a regular probability distribution or a regular ranking series.

Seen from the opposite point of view, if the ranked frequencies are properly distributed we have a preliminary approximate corroboration of the “correctness” of the classification, i.e. we approximate some linguistic-psychological truth.

3. Derivation

3.1. The Zipf-Alekseev distribution

The derivation is shown in Word associations (

is

Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): P_x = begin{cases} alpha, & x=1 \ frac{(1-alpha)x^{a+b ln x}}{T} & x = 2,3,…,n end{cases}

,

where Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): T= sum_{j=2}^N j^{a+b ln x}

.

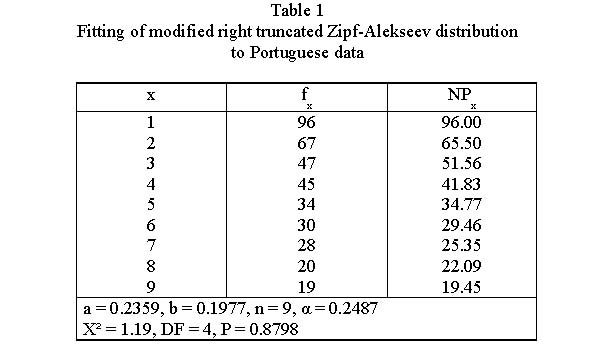

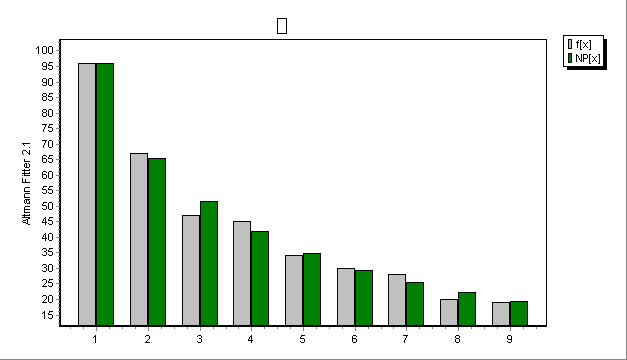

Example: Word classes in Portuguese (Ziegler 2001).

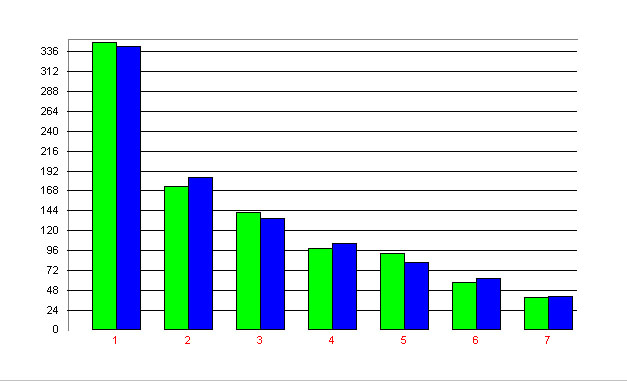

Figure 1. Fitting of modified right truncated Zipf-Alekseev distribution to Portuguese data

3.2. The negative hypergeometric distribution

The frequency of ranked word classes abides by the usual proportionality relation between neighboring classes. Using the proportionality function

Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): g(x)= frac{(M+x-1)(K-M+n-x)}{x(n-x+1)}

and solving with displacement

(1) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): P_{x+1}=frac{(M+x-1)(K-M+n-x)}{x(n-x+1)}P_x

one obtains the 1-displaced negative hypergeometric distribution

(2) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): P_x = frac{{-M choose x-1}{-K+M choose n-x+1}}{{-K choose n}}, quad x=1,2,3,…,n,quad Kgeq Mgeq 0,quad n in N

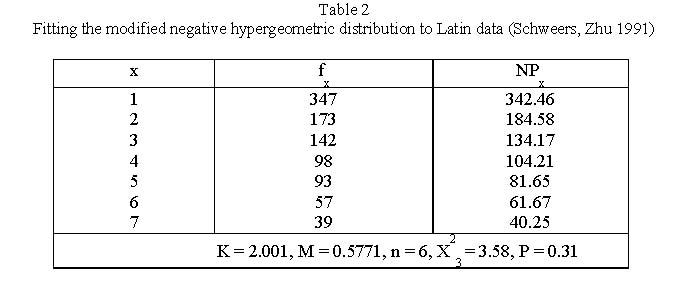

Example: Word classes in Latin (Schweers, Zhu 1991)

Schweers and Zhu examined word classes in Latin, German and Chinese and found satisfactory fits for Latin and German. For Latin, they took Caesar´s “Bellum Gallicum”, Book 1, Chapters 1-8, § 2, and obtained the results in Table 2. The majority of researchers used this distribution.

Figure 2. Fitting the negative hypergeometric distribution to Latin data

3.3. Altmann´s series

Altmann (1993) did not strive for a distribution but simply for a series capturing the decreasing frequencies (absolute or relative) of ranked classes. Consider the Zipf-Mandelbrot law as a (not normalized) continuous function. Its differential equation is

(2) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): frac{dy}{y}= -frac{c}{a+x}dx

,

i.e. a special case of the unified theory (→). Since ranking proceeds in unit steps, Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): dx = 1

and Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): dy=yx+1-yx

, we obtain

(3) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): frac{y_{x+1}-y_x}{y_x}= -frac{c}{a+x}

.

Reordering, setting Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): a — c = b

, and solving (3), results in

(4) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): y_x = frac{{b+x choose x-1}}{{a+x choose x-1}}y_1, quad x=1,2,3,…

The parameters fulfill one of the conditions (i) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): a > b > 0

, (ii) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): a > 0

, Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): -1 < b < 0

, (iii) Failed to parse (Missing <code>texvc</code> executable. Please see math/README to configure.): b < a < 0

when

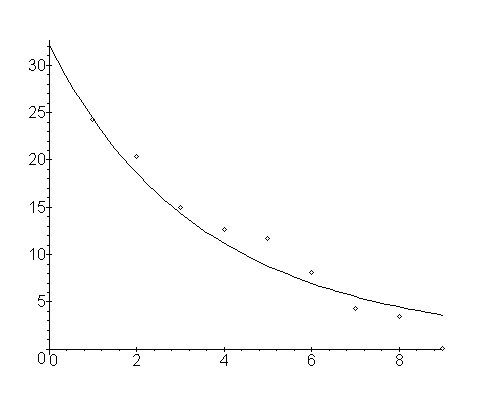

Example: Word class distribution in a German text (Best 1997)

Altmann used (4) only for phoneme ranking, but Best (1994, 1997) used it also for word classes with very satisfactory results. The fitting of (4) to the relative frequencies of word classes in a German text (Bichsel, P., Der Mann, der nichts mehr wissen wollte) yielded results presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Here

4. Authors: U. Strauss, G. Altmann, K.-H. Best

5. References

Altmann, G. (1991). Word class diversification of Arabic verbal roots. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 57-59. Hagen: Rottmann.

Altmann, G. (1993). Phoneme counts. Glottometrika 14, 55-70.

Best, K.-H. (1994). Word class frequencies in contemporary German short prose texts. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 1, 144-147.

Best, K.-H. (1997). Zur Wortartenhäufigkeit in Texten deutscher Kurzprosa der Gegenwart. Glottometrika 16, 276-285.

Best, K-H. (1998). Zur Interaktion der Wortarten in Texten. Papiere zur Linguistik 58: 83-95.

Best, K.-H. (2000). Verteilung der Wortarten in Anzeigen. Göttinger Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 4, 37-51.

Best, K.-H. (2001a). Zur Gesetzmäßigkeit der Wortartenverteilungen in deutschen Pressetexten. Glottometrics 1, 1-26.

Best, K.H. (2001b). Quantitative Linguistik. Eine Annäherung. Göttingen: Peust & Gutschmidt.

Bosselmann, A. (2001). Wortartenverteilungen in russischen Texten. Msc.

Hammerl, R. (1990). Untersuchungen zur Verteilung der Wortarten im Text. Glottometrika 11, 142-156.

Hřebíček, L. (2000). Variation in sequences. Prague: Oriental Institute.

Hudson, R. (1994). About 37 % of word-tokens are nouns. Language 70, 331-339.

Judt, B. (1995). Wortartenhäufigkeiten im Deutschen und Französischen. Göttingen: Staatsexamensarbeit.

Köhler, R. (1991). Diversification of coding methods in grammar. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 47-55. Hagen: Rottmann.

Lauter, J. (1966). Untersuchungen zur Sprache von Kants “Kritik der reinen Vernunft”. Köln: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Mizutani, S. (1989). Ohno’s lexical law: its data adjustment by linear regression. In: Mizutani, S. (ed.), Japanese Quantitative Linguistics. Bochum: Brockmeyer. 1-13.

Schindelin, C. (2005). Die quantitative Erforschung der chinesischen Sprache und Schrift. In: Köhler, R., Altmann, G., Piotrowski, R.G. (eds.), Quantitative Linguistics — An Inernational handbook: 947-970. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Schweers, A., Zhu, J. (1991). Wortartenklassifikation im Lateinischen, Deutschen und Chinesischen. In: Rothe, U. (ed.), Diversification Processes in Language: Grammar: 157-167. Hagen: Rottmann.

Uhlířová, L. (2000). On language modelling in automatic speech recognition. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 7, 209-216.

Wimmer, G., Altmann, G. (2001). Some statistical investigations concerning word classes. Glottometrics 1, 109-123.

Zhu, J, Best, K.-H. (1992). Zum Wort im modernen Chinesisch. Oriens Extremus 35, 45-60.

Ziegler, A. (1998). Word class frequencies in Brazilian-Portuguese texts. J. of Quantitative Linguistics 5, 269-280.

Ziegler, A. (2001). Word class frequencies in Portuguese press texts. In: Uhlířová, L., Wimmer, G., Altmann, G., Köhler, R. (eds.), Text as a Linguistic Paradigm: Levels, Constituents, Constructs. Festschrift in Honour of Ludek Hřebíček: 295-312. Trier: WVT.

Ziegler, A., Best, K.-H., Altmann, G. (2002). Nominalstil. ETC 2, 72-85.

Ziegler, A., Best, K.-H., Altmann, G. (2001). A contribution to text spectra. Glottometrics 1, 97-108.

Select your language

Suggested languages for you:

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmelden

Words don’t only mean something; they also do something. In the English language, words are grouped into word classes based on their function, i.e. what they do in a phrase or sentence. In total, there are nine word classes in English.

Word class meaning and example

All words can be categorised into classes within a language based on their function and purpose.

An example of various word classes is ‘The cat ate a cupcake quickly.’

-

The = a determiner

-

cat = a noun

-

ate = a verb

-

a = determiner

-

cupcake = noun

-

quickly = an adverb

Word class function

The function of a word class, also known as a part of speech, is to classify words according to their grammatical properties and the roles they play in sentences. By assigning words to different word classes, we can understand how they should be used in context and how they relate to other words in a sentence.

Each word class has its own unique set of characteristics and rules for usage, and understanding the function of word classes is essential for effective communication in English. Knowing our word classes allows us to create clear and grammatically correct sentences that convey our intended meaning.

Word classes in English

In English, there are four main word classes; nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. These are considered lexical words, and they provide the main meaning of a phrase or sentence.

The other five word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are considered functional words, and they provide structural and relational information in a sentence or phrase.

Don’t worry if it sounds a bit confusing right now. Read ahead and you’ll be a master of the different types of word classes in no time!

| All word classes | Definition | Examples of word classification |

| Noun | A word that represents a person, place, thing, or idea. | cat, house, plant |

| Pronoun | A word that is used in place of a noun to avoid repetition. | he, she, they, it |

| Verb | A word that expresses action, occurrence, or state of being. | run, sing, grow |

| Adjective | A word that describes or modifies a noun or pronoun. | blue, tall, happy |

| Adverb | A word that describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or other adverb. | quickly, very |

| Preposition | A word that shows the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. | in, on, at |

| Conjunction | A word that connects words, phrases, or clauses. | and, or, but |

| Interjection | A word that expresses strong emotions or feelings. | wow, oh, ouch |

| Determiners | A word that clarifies information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun | Articles like ‘the’ and ‘an’, and quantifiers like ‘some’ and ‘all’. |

The four main word classes

In the English language, there are four main word classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Let’s look at all the word classes in detail.

Nouns

Nouns are the words we use to describe people, places, objects, feelings, concepts, etc. Usually, nouns are tangible (touchable) things, such as a table, a person, or a building.

However, we also have abstract nouns, which are things we can feel and describe but can’t necessarily see or touch, such as love, honour, or excitement. Proper nouns are the names we give to specific and official people, places, or things, such as England, Claire, or Hoover.

Cat

House

School

Britain

Harry

Book

Hatred

‘My sister went to school.‘

Verbs

Verbs are words that show action, event, feeling, or state of being. This can be a physical action or event, or it can be a feeling that is experienced.

Lexical verbs are considered one of the four main word classes, and auxiliary verbs are not. Lexical verbs are the main verb in a sentence that shows action, event, feeling, or state of being, such as walk, ran, felt, and want, whereas an auxiliary verb helps the main verb and expresses grammatical meaning, such as has, is, and do.

Run

Walk

Swim

Curse

Wish

Help

Leave

‘She wished for a sunny day.’

Adjectives

Adjectives are words used to modify nouns, usually by describing them. Adjectives describe an attribute, quality, or state of being of the noun.

Long

Short

Friendly

Broken

Loud

Embarrassed

Dull

Boring

‘The friendly woman wore a beautiful dress.’

Adverbs

Adverbs are words that work alongside verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. They provide further descriptions of how, where, when, and how often something is done.

Quickly

Softly

Very

More

Too

Loudly

‘The music was too loud.’

All of the above examples are lexical word classes and carry most of the meaning in a sentence. They make up the majority of the words in the English language.

The other five word classes

The other five remaining word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These words are considered functional words and are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

For example, prepositions can be used to explain where one object is in relation to another.

Prepositions

Prepositions are used to show the relationship between words in terms of place, time, direction, and agency.

In

At

On

Towards

To

Through

Into

By

With

‘They went through the tunnel.’

Pronouns

Pronouns take the place of a noun or a noun phrase in a sentence. They often refer to a noun that has already been mentioned and are commonly used to avoid repetition.

Chloe (noun) → she (pronoun)

Chloe’s dog → her dog (possessive pronoun)

There are several different types of pronouns; let’s look at some examples of each.

- He, she, it, they — personal pronouns

- His, hers, its, theirs, mine, ours — possessive pronouns

- Himself, herself, myself, ourselves, themselves — reflexive pronouns

- This, that, those, these — demonstrative pronouns

- Anyone, somebody, everyone, anything, something — Indefinite pronouns

- Which, what, that, who, who — Relative pronouns

‘She sat on the chair which was broken.’

Determiners

Determiners work alongside nouns to clarify information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun. It ‘determines’ exactly what is being referred to. Much like pronouns, there are also several different types of determiners.

- The, a, an — articles

- This, that, those — you might recognise these for demonstrative pronouns are also determiners

- One, two, three etc. — cardinal numbers

- First, second, third etc. — ordinal numbers

- Some, most, all — quantifiers

- Other, another — difference words

‘The first restaurant is better than the other.’

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses together within a sentence. There are three main types of conjunctions;

-

Coordinating conjunctions — these link independent clauses together.

-

Subordinating conjunctions — these link dependent clauses to independent clauses.

- Correlative conjunctions — words that work in pairs to join two parts of a sentence of equal importance.

For, and, nor, but, or, yet, so — coordinating conjunctions

After, as, because, when, while, before, if, even though — subordinating conjunctions

Either/or, neither/nor, both/and — correlative conjunctions

‘If it rains, I’m not going out.’

Interjections

Interjections are exclamatory words used to express an emotion or a reaction. They often stand alone from the rest of the sentence and are accompanied by an exclamation mark.

Oh

Oops!

Phew!

Ahh!

‘Oh, what a surprise!’

Word class: lexical classes and function classes

A helpful way to understand lexical word classes is to see them as the building blocks of sentences. If the lexical word classes are the blocks themselves, then the function word classes are the cement holding the words together and giving structure to the sentence.

In this diagram, the lexical classes are in blue and the function classes are in yellow. We can see that the words in blue provide the key information, and the words in yellow bring this information together in a structured way.

Word class examples

Sometimes it can be tricky to know exactly which word class a word belongs to. Some words can function as more than one word class depending on how they are used in a sentence. For this reason, we must look at words in context, i.e. how a word works within the sentence. Take a look at the following examples of word classes to see the importance of word class categorisation.

The dog will bark if you open the door.

The tree bark was dark and rugged.

Here we can see that the same word (bark) has a different meaning and different word class in each sentence. In the first example, ‘bark’ is used as a verb, and in the second as a noun (an object in this case).

I left my sunglasses on the beach.

The horse stood on Sarah’s left foot.

In the first sentence, the word ‘left’ is used as a verb (an action), and in the second, it is used to modify the noun (foot). In this case, it is an adjective.

I run every day

I went for a run

In this example, ‘run’ can be a verb or a noun.

Word Class — Key takeaways

-

We group words into word classes based on the function they perform in a sentence.

-

The four main word classes are nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. These are lexical classes that give meaning to a sentence.

-

The other five word classes are prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are function classes that are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

-

It is important to look at the context of a sentence in order to work out which word class a word belongs to.

Frequently Asked Questions about Word Class

A word class is a group of words that have similar properties and play a similar role in a sentence.

Some examples of how some words can function as more than one word class include the way ‘run’ can be a verb (‘I run every day’) or a noun (‘I went for a run’). Similarly, ‘well’ can be an adverb (‘He plays the guitar well’) or an adjective (‘She’s feeling well today’).

The nine word classes are; Nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, interjections.

Categorising words into word classes helps us to understand the function the word is playing within a sentence.

Parts of speech is another term for word classes.

The different groups of word classes include lexical classes that act as the building blocks of a sentence e.g. nouns. The other word classes are function classes that act as the ‘glue’ and give grammatical information in a sentence e.g. prepositions.

The word classes for all, that, and the is:

‘All’ = determiner (quantifier)

‘That’ = pronoun and/or determiner (demonstrative pronoun)

‘The’ = determiner (article)

Final Word Class Quiz

Word Class Quiz — Teste dein Wissen

Question

A word can only belong to one type of noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is false. A word can belong to multiple categories of nouns and this may change according to the context of the word.

Show question

Question

Name the two principal categories of nouns.

Show answer

Answer

The two principal types of nouns are ‘common nouns’ and ‘proper nouns’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following is an example of a proper noun?

Show answer

Question

Name the 6 types of common nouns discussed in the text.

Show answer

Answer

Concrete nouns, abstract nouns, countable nouns, uncountable nouns, collective nouns, and compound nouns.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a concrete noun and an abstract noun?

Show answer

Answer

A concrete noun is a thing that physically exists. We can usually touch this thing and measure its proportions. An abstract noun, however, does not physically exist. It is a concept, idea, or feeling that only exists within the mind.

Show question

Question

Pick out the concrete noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

Pick out the abstract noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the difference between a countable and an uncountable noun? Can you think of an example for each?

Show answer

Answer

A countable noun is a thing that can be ‘counted’, i.e. it can exist in the plural. Some examples include ‘bottle’, ‘dog’ and ‘boy’. These are often concrete nouns.

An uncountable noun is something that can not be counted, so you often cannot place a number in front of it. Examples include ‘love’, ‘joy’, and ‘milk’.

Show question

Question

Pick out the collective noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the collective noun for a group of sheep?

Show answer

Answer

The collective noun is a ‘flock’, as in ‘flock of sheep’.

Show question

Question

The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is true. The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun as it is made up of two separate words ‘green’ and ‘house’. These come together to form a new word.

Show question

Question

What are the adjectives in this sentence?: ‘The little boy climbed up the big, green tree’

Show answer

Answer

The adjectives are ‘little’ and ‘big’, and ‘green’ as they describe features about the nouns.

Show question

Question

Place the adjectives in this sentence into the correct order: the wooden blue big ship sailed across the Indian vast scary ocean.

Show answer

Answer

The big, blue, wooden ship sailed across the vast, scary, Indian ocean.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 different positions in which an adjective can be placed?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective can be placed before a noun (pre-modification), after a noun (post-modification), or following a verb as a complement.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘The unicorn is angry’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘angry’ post-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘It is a scary unicorn’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘scary’ pre-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘purple’ and ‘shiny’?

Show answer

Answer

‘Purple’ and ‘Shiny’ are qualitative adjectives as they describe a quality or feature of a noun

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’?

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’ are evaluative adjectives as they give a subjective opinion on the noun.

Show question

Question

Which of the following adjectives is an absolute adjective?

Show answer

Question

Which of these adjectives is a classifying adjective?

Show answer

Question

Convert the noun ‘quick’ to its comparative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘quick’ is ‘quicker’.

Show question

Question

Convert the noun ‘slow’ to its superlative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘slow’ is ‘slowest’.

Show question

Question

What is an adjective phrase?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective phrase is a group of words that is ‘built’ around the adjective (it takes centre stage in the sentence). For example, in the phrase ‘the dog is big’ the word ‘big’ is the most important information.

Show question

Question

Give 2 examples of suffixes that are typical of adjectives.

Show answer

Answer

Suffixes typical of adjectives include -able, -ible, -ful, -y, -less, -ous, -some, -ive, -ish, -al.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a main verb and an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

A main verb is a verb that can stand on its own and carries most of the meaning in a verb phrase. For example, ‘run’, ‘find’. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone, instead, they work alongside a main verb and ‘help’ the verb to express more grammatical information e.g. tense, mood, possibility.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a primary auxiliary verb and a modal auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

Primary auxiliary verbs consist of the various forms of ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’ e.g. ‘had’, ‘was’, ‘done’. They help to express a verb’s tense, voice, or mood. Modal auxiliary verbs show possibility, ability, permission, or obligation. There are 9 auxiliary verbs including ‘could’, ‘will’, might’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are primary auxiliary verbs?

-

Is

-

Play

-

Have

-

Run

-

Does

-

Could

Show answer

Answer

The primary auxiliary verbs in this list are ‘is’, ‘have’, and ‘does’. They are all forms of the main primary auxiliary verbs ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’. ‘Play’ and ‘run’ are main verbs and ‘could’ is a modal auxiliary verb.

Show question

Question

Name 6 out of the 9 modal auxiliary verbs.

Show answer

Answer

Answers include: Could, would, should, may, might, can, will, must, shall

Show question

Question

‘The fairies were asleep’. In this sentence, is the verb ‘were’ a linking verb or an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

The word ‘were’ is used as a linking verb as it stands alone in the sentence. It is used to link the subject (fairies) and the adjective (asleep).

Show question

Question

What is the difference between dynamic verbs and stative verbs?

Show answer

Answer

A dynamic verb describes an action or process done by a noun or subject. They are thought of as ‘action verbs’ e.g. ‘kick’, ‘run’, ‘eat’. Stative verbs describe the state of being of a person or thing. These are states that are not necessarily physical action e.g. ‘know’, ‘love’, ‘suppose’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are dynamic verbs and which are stative verbs?

-

Drink

-

Prefer

-

Talk

-

Seem

-

Understand

-

Write

Show answer

Answer

The dynamic verbs are ‘drink’, ‘talk’, and ‘write’ as they all describe an action. The stative verbs are ‘prefer’, ‘seem’, and ‘understand’ as they all describe a state of being.

Show question

Question

What is an imperative verb?

Show answer

Answer

Imperative verbs are verbs used to give orders, give instructions, make a request or give warning. They tell someone to do something. For example, ‘clean your room!’.

Show question

Question

Inflections give information about tense, person, number, mood, or voice. True or false?

Show answer

Question

What information does the inflection ‘-ing’ give for a verb?

Show answer

Answer

The inflection ‘-ing’ is often used to show that an action or state is continuous and ongoing.

Show question

Question

How do you know if a verb is irregular?

Show answer

Answer

An irregular verb does not take the regular inflections, instead the whole word is spelt a different way. For example, begin becomes ‘began’ or ‘begun’. We can’t add the regular past tense inflection -ed as this would become ‘beginned’ which doesn’t make sense.

Show question

Question

Suffixes can never signal what word class a word belongs to. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. Suffixes can signal what word class a word belongs to. For example, ‘-ify’ is a common suffix for verbs (‘identity’, ‘simplify’)

Show question

Question

A verb phrase is built around a noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. A verb phrase is a group of words that has a main verb along with any other auxiliary verbs that ‘help’ the main verb. For example, ‘could eat’ is a verb phrase as it contains a main verb (‘could’) and an auxiliary verb (‘could’).

Show question

Question

Which of the following are multi-word verbs?

-

Shake

-

Rely on

-

Dancing