В современном английском языке слово teacher — существительное. Оно переводится как «учитель; преподаватель».

Это слово появилось в английском языке в XIV в. в значении «тот, кто учит». Оно было образовано от глагола to teach. В древнеанглийский период этот глагол выглядел как tæcan и означал «показывать; объявлять». У него также было и другое значение — «давать указания, обучать, направлять; предупреждать; убеждать». Он восходит к прагерманскому *taikijan, «показывать». Последнее же произошло от праиндоевропейского корня *deik-, «показывать, указывать». Глагол tæcan родственен древнеанглийскому tacen или tacn, «знак».

В конце XIII в. слово teach употреблялось в значении «указательный палец».

Выражение teacher’s pet, «любимчик учителя» появилось в 1856 году.

Напиши пробный диктант и оцени качество диктовки, удобство написания и понятность разбора ошибок!

Ознакомительный диктант

- Afrikaans: onderwyser (af) m

- Albanian: arsimtar (sq) m, mësues (sq) m

- Aleut: achixanax

- Amharic: አስተማሪ (ʾästämari)

- Apache:

- Western Apache: bik’eh da’ółtagí

- Arabic: مُعَلِّم (ar) m (muʕallim), مُعَلِّمَة f (muʕallima), مُدَرِّس (ar) m (mudarris), مُدَرِّسَة (ar) f (mudarrisa), أُسْتَاذ (ar) m (ʔustāḏ), أُسْتَاذَة f (ʔustāḏa)

- Egyptian Arabic: مدرس m (mudares), خوجه m (ḫūgah) (archaic)

- Hijazi Arabic: أُسْتَاذ m (ʾustāḏ), مدرس m (mudarris)

- Moroccan Arabic: معلم (muʿallim), أستاد (ʾustād)

- Armenian: ուսուցիչ (hy) (usucʿičʿ), դասատու (hy) (dasatu)

- Assamese: শিক্ষক (xikhok)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic: ܡܲܠܦܵܢܵܐ m (mālpana), ܡܲܠܦܵܢܬܵܐ f (mālpanta), ܪܵܒܝܼ m (rabī), ܐܽܘܣܬܳܐܕ݇ m (ūstāda) (Urmia)

- Asturian: profesor (ast) m, maestru (ast) m

- Avar: мугӏалим (muʻalim)

- Azerbaijani: müəllim (az)

- Bashkir: уҡытыусы (uqıtıwsı)

- Basque: irakasle (eu) m, maisu m

- Belarusian: наста́ўнік m (nastáŭnik), выхава́льнік m (vyxaválʹnik)

- Bengali: ওস্তাদ (bn) (ōstad), মুয়াল্লিম (bn) (muallim), শিক্ষক (bn) (śikkhok)

- Biatah Bidayuh: guruu

- Bikol Central: paratukdo (bcl)

- Bislama: tija

- Breton: kelenner (br) m

- Bulgarian: учи́тел (bg) m (učítel), учи́телка f (učítelka), преподава́тел (bg) m (prepodavátel), преподава́телка f (prepodavátelka)

- Burmese: ဆရာ (my) (hca.ra), ဆရာမ (my) (hca.rama.) (female)

- Buryat: багша (bagša)

- Catalan: professor (ca) m, professora (ca) f, ensenyant (ca) m or f, mestre (ca) m

- Cebuano: magtutudlo

- Chechen: хьехархо (ḥʳexarxo)

- Cherokee: ᏗᏕᏲᎲᏍᎩ (dideyohvsgi)

- Chichewa: mphunzitsi

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 老師/老师 (lou5 si1), 教師/教师 (gaau3 si1), 先生 (sin1 saang1)

- Dungan: лошы (lošɨ), җёйүан (ži͡oyüan), сыфу (sɨfu), вуста (vusta), сынён (sɨni͡on) (female), нүлошы (nülošɨ) (female)

- Hakka: 先生 (sîn-sâng), 教師/教师 (kau-sṳ̂), 老師/老师 (ló-sṳ̂)

- Mandarin: 教師/教师 (zh) (jiàoshī), 老師/老师 (zh) (lǎoshī), 教員/教员 (zh) (jiàoyuán), 師父/师父 (zh) (shīfu) (especially martial arts)

- Min Dong: 老師/老师 (lō̤-sṳ̆)

- Min Nan: 教師/教师 (zh-min-nan) (kàu-su), 老師/老师 (zh-min-nan) (lāu-su, ló-su), 先生 (zh-min-nan) (sin-seⁿ, sin-siⁿ)

- Wu: 老師/老师 (lau sr)

- Chukchi: кэлиныгйивэтыльын (kėlinygjivėtylʹyn)

- Chuukese: sense

- Chuvash: учитель (uč̬it̬elʹ), вӗрентекен (vĕrent̬ek̬en)

- Coptic: ⲥⲁϧ m (sax), ⲕⲁⲑⲏⲅⲉⲧⲏⲥ m (kathēgetēs), ⲅⲣⲁⲙⲁⲧⲉⲟⲥ m (gramateos), ⲣⲉϥϯⲥⲃⲱ m (reftisbō)

- Cornish: adhyskonydh, dyskador m

- Crimean Tatar: muallim

- Czech: učitel (cs) m

- Danish: lærer (da) m

- Daur: seb, bakx

- Dolgan: учитель (uçitelʹ)

- Dutch: leraar (nl) m, onderwijzer (nl) m, docent (nl) m, leerkracht (nl) m, schoolmeester (nl) m

- Erzya: тонавтыця (tonavtića), учитель (učiťeľ)

- Esperanto: instruisto (eo)

- Estonian: õpetaja (et)

- Even: учитель (ucitel’), хупкучимӈэ̇ (hupkucimŋə̇)

- Evenki: учитель (uçitel’), алагӯмнӣ (alagūmņī), татыга̄мнӣ (tatigāmņī), татка̄мӈӯ (tatkāmŋū), учутал (uçutal)

- Faroese: lærari m

- Finnish: opettaja (fi)

- French: professeur (fr) m, maître d’école (fr) m, enseignant (fr) m, instituteur (fr) (primary school )

- Galician: mestre (gl) m

- Georgian: მასწავლებელი (ka) (masc̣avlebeli), პედაგოგი (ṗedagogi)

- German: Lehrer (de) m, Lehrerin (de) f

- Gothic: 𐌻𐌰𐌹𐍃𐌰𐍂𐌴𐌹𐍃 m (laisāreis), 𐍄𐌰𐌻𐌶𐌾𐌰𐌽𐌳𐍃 m (talzjands)

- Greek: δάσκαλος (el) m (dáskalos)

- Ancient: διδάσκαλος (didáskalos), κατηχητής m (katēkhētḗs)

- Gujarati: શિક્ષક (śikṣak)

- Hausa: malami

- Hawaiian: kumu

- Hebrew: מוֹרֶה (he) m (moré)

- Hindi: अध्यापक (hi) m (adhyāpak), टीचर m (ṭīcar), शिक्षक (hi) m (śikṣak), गुरु (hi) m (guru), आचार्य (hi) m (ācārya) (Hinduism, Buddhism), मुअल्लिम (hi) m (muallim), उस्ताद (hi) m (ustād), उपाध्याय (hi) m (upādhyāy), आचार्य (hi) m (ācārya)

- Hungarian: tanár (hu), tanító (hu), oktató (hu), pedagógus (hu)

- Hunsrik: Leerer m, Leerin f

- Icelandic: kennari (is) m

- Ido: instruktisto (io)

- Ifè: akɔ́nɛ

- Igala: ítíchà

- Inari Sami: opâtteijee

- Indonesian: guru (id), pengajar (id)

- Interlingua: maestro (ia), magistro, professor de schola, instructor, inseniator

- Inuktitut: ᐃᓕᓭᔨ (iliseyi)

- Irish: múinteoir (ga) m

- Italian: insegnante (it) m, docente (it) m, professore (it) m, maestro (it) m, aio (it) m, educatore (it) m, precettore (it) m

- Japanese: 先生 (ja) (せんせい, sensei), 教師 (ja) (きょうし, kyōshi)

- Javanese: guru, dwija (jv)

- Jeju: 선싕 (seonsuing), 선싕님 (seonsuingnim) (honorific), 선셍 (seonseng), 선승 (seonseung), 성선 (seongseon)

- Kalmyk: багш (bagsh), сурһач (surğach)

- Kamba: mwaalimu

- Kannada: ಶಿಕ್ಷಕ (kn) (śikṣaka), ಅಧ್ಯಾಪಕ (kn) (adhyāpaka), ಗುರು (kn) (guru)

- Kazakh: мұғалім (kk) (mūğalım), оқытушы (kk) (oqytuşy)

- Khmer: គ្រូបង្រៀន (kruu bɑngriən), គ្រូ (km) (kruu), អាចារ្យ (km) (ʼaacaa), អាចរិយ (km) (ʼaacaʼreyaʼ), លោកគ្រូ (look kruu), អ្នកគ្រូ (nĕək kruu) (female)

- Kikuyu: mũrutani class 1

- Kis: mwaalimu

- Komi-Permyak: велӧтісь (velötiś)

- Korean: 선생(先生) (ko) (seonsaeng), 선생님 (ko) (seonsaengnim) (honorific), 교사(敎師) (ko) (gyosa)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: مامۆستا (ckb) (mamosta)

- Northern Kurdish: mamosta (ku), hînker (ku)

- Kyrgyz: мугалим (ky) (mugalim), окутуучу (ky) (okutuuçu)

- Ladino: professor, maestro

- Lao: ຄູ (lo) (khū), ນາຍຄູ (nāi khū), ອາຈານ (ʼā chān)

- Latin: docens (la) m, doctor m, praeceptor (la) m, magister (la) m, litterātor m (elementary school)

- Latvian: skolotājs (lv) m

- Lithuanian: mokytojas (lt) m, dėstytojas m

- Livonian: opātiji

- Luhya: omwalimu

- Luo: japuonj

- Lushootseed: dxʷsʔugʷusaɬ, dxʷsʔugʷucidid

- Lü: ᦟᧁᦌᦹᧈ (lawsue¹), ᦁᦱᦈᦱᧃ (ʼaaṫsaan), ᦗᦸᧈᦆᦴ (poa¹xuu) (male), ᦆᦴᦉᦸᧃ (xuuṡoan), ᦆᦴ (xuu)

- Macedonian: учител m (učitel) (elementary school), наставник m (nastavnik) (intermediate school), воспитувач m (vospituvač) (preschool), професор m (profesor) (high school & university), пре́давач m (prédavač) (university lecturer)

- Malay: guru (ms), cikgu (more colloquial)

- Malayalam: അദ്ധ്യാപകൻ (addhyāpakaṉ), ഗുരു (ml) (guru)

- Maltese: għalliem m, għalliema f

- Manchu: ᠰᡝᡶᡠ (sefu)

- Manx: ynseyder m

- Maori: māhita kura, kaiwhakaako

- Marathi: शिक्षक (śikṣak), टीचर (ṭīcar), गुरु m (guru)

- Mari:

- Eastern Mari: учитель (učiteľ)

- Meru: mwarimo

- Mingrelian: მაგურაფალი (magurapali)

- Moksha: тонафты (tonafti), учитель (učiťeľ)

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: багш (mn) (bagš)

- Mongolian: ᠪᠠᠭᠰᠢ (baɣsi)

- Navajo: báʼóltaʼí

- Nepali: शिक्षक (ne) (śikṣak)

- Ngazidja Comorian: fundi

- Norman: ensîngnant m

- Northern Sami: oahpaheaddji

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: lærer (no) m, skolelærer m

- Nynorsk: lærar (nn) m

- Occitan: ensenhaire (oc) m, ensenhant m, mèstre (oc) m, professor (oc) m

- Ojibwe: gekinoo’amaaged

- Old English: lārēow m

- Old Javanese: guru

- Oriya: ଶିକ୍ଷକ (or) (śikṣôkô)

- Osage: wakǫ́ze

- Ossetian: ахуыргӕнӕг (ax°yrgænæg)

- Pali: ācariya m, guru m

- Pashto: استاد m (ostãd), استاذ (ps) m (ostãz), ښوونکی (ps) m (ӽowúnkay), معلم m (mo’além)

- Persian: آموزگار (fa) (âmuzgâr), آموزاننده, معلم (fa) (mo’allem), استاد (fa) (ostâd)

- Pijin: tisa

- Polish: nauczyciel (pl) m, belfer (pl) m

- Portuguese: professor (pt) m, docente (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਅਧਿਆਪਕ (pa) (adhiāpak)

- Quechua: yachachiq

- Romagnol: majèstar m, mèstar m

- Romani: siklǎrno m

- Romanian: profesor (ro) m, învățător (ro) m

- Russian: учи́тель (ru) m (učítelʹ), учи́тельница (ru) f (učítelʹnica), преподава́тель (ru) m (prepodavátelʹ), преподава́тельница (ru) f (prepodavátelʹnica), наста́вник (ru) m (nastávnik), наста́вница (ru) f (nastávnica)

- Sanskrit: गुरु (sa) (guru), आचार्य (sa) m (ācārya), अध्यापक (sa) m (adhyāpaka), शिक्षक (sa) m (śikṣaka)

- Scottish Gaelic: fear-teagaisg m, neach-teagaisg m, muinear m, tidsear m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: учитељ m, васпитач m, наставник m

- Roman: učitelj (sh) m, vaspitač (sh) m, nastavnik (sh) m

- Shor: ӱргедигчи (ürgedigçi)

- Sinhalese: ගුරුතුමා (gurutumā), ගුරුවරයා (guruwarayā), ආචාර්ය (ācārya)

- Skolt Sami: uʹčteeʹl

- Slovak: učiteľ m

- Slovene: učítelj (sl) m

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: ceptaŕ m, wucabnik m

- Sotho: titjhere (st)

- Southern Altai: ӱредӱчи (üredüči)

- Spanish: maestro (es) m, profesor (es) m, docente (es) m

- Swahili: mwalimu (sw), maalim (sw)

- Swedish: lärare (sv) m

- Tagalog: guro (tl), maestro, titser

- Tajik: муаллим (tg) (muallim), устод (tg) (ustod), омӯзгор (tg) (omüzgor)

- Tamil: ஆசிரியர் (ta) (āciriyar), குரு (ta) (kuru)

- Taos: mèstu’úna

- Tatar: укытучы (tt) (uqıtuçı), мөгаллим (mögallim), остаз (tt) (ostaz)

- Telugu: ఉపాధ్యాయుడు (te) (upādhyāyuḍu)

- Thai: ครู (th) (kruu), อาจารย์ (th) (aa-jaan)

- Tibetan: དགེ་རྒན (dge rgan)

- Tigrinya: መምህር (mämhər)

- Tocharian A: käṣṣi

- Tocharian B: käṣṣī

- Tok Pisin: tisa

- Turkish: öğretmen (tr), muallim (tr) (old), hoca (tr)

- Turkmen: mugallym

- Udmurt: дышетӥсь (dyšetiś)

- Ukrainian: учи́тель (uk) m (učýtelʹ), вчи́тель (uk) m (včýtelʹ), виклада́ч m (vykladáč)

- Urdu: ادھیاپاک m (adhyāpak), معلم (ur) m (mu’allim), ٹیچر m (ṭīcar), اُسْتاد m (ustād)

- Uyghur: ئوقۇتقۇچى (oqutquchi), مۇئەللىم (mu’ellim), ئۇستاز (ustaz)

- Uzbek: o’qituvchi (uz), oʻqituvchi (uz)

- Vietnamese: giáo viên (vi) (教員)

- Volapük: tidan (vo), hitidan, kladatidan, kladahitidan, kladanefitidan, kladanefihitidan

- Walloon: mwaisse di scole m, professeur (wa) m, prof (wa) m or f, scoleu (wa) m

- Welsh: athro (cy) m, dysgwr (cy) m

- West Frisian: learaar

- Western Panjabi: استاد (pnb)

- White Hmong: thawj xibhwb

- Yagnobi: малим (malim)

- Yakut: учуутал (ucuutal), үөрэтээччи (üöreteecci)

- Yapese: sensey

- Yiddish: לערער m (lerer)

- Yoruba: olùkọ́

- Zazaki: musner c musnayoğ (diq) c ma’lim c xoca c

- Zhuang: lauxsae

- Zulu: umfundisi (zu) class 1/2, uthisha (zu) class 1a/2a

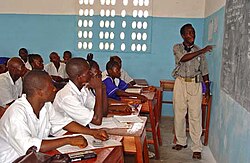

A teacher in a classroom at a secondary school in Pendembu, Sierra Leone |

|

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Teacher, educator, schoolteacher |

|

Occupation type |

Profession |

|

Activity sectors |

Education |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Pedagogy, subject knowledge; competence in teaching the subject, in curriculum, in learner assessment; psychology; planning; leadership.[1] |

|

Education required |

(varies by country) Teaching certification |

|

Fields of |

Schools |

|

Related jobs |

Professor, academic, lecturer, tutor |

A teacher of a Latin school and two students, 1487

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

Informally the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. when showing a colleague how to perform a specific task).

In some countries, teaching young people of school age may be carried out in an informal setting, such as within the family (homeschooling), rather than in a formal setting such as a school or college.

Some other professions may involve a significant amount of teaching (e.g. youth worker, pastor).

In most countries, formal teaching of students is usually carried out by paid professional teachers. This article focuses on those who are employed, as their main role, to teach others in a formal education context, such as at a school or other place of initial formal education or training.

Duties and functions

A teacher’s role may vary among cultures.

Teachers may provide instruction in literacy and numeracy, craftsmanship or vocational training, the arts, religion, civics, community roles, or life skills.

Formal teaching tasks include preparing lessons according to agreed curricula, giving lessons, and assessing pupil progress.

A teacher’s professional duties may extend beyond formal teaching. Outside of the classroom teachers may accompany students on field trips, supervise study halls, help with the organization of school functions, and serve as supervisors for extracurricular activities. They also have the legal duty to protect students from harm,[3] such as that which may result from bullying,[4] sexual harassment, racism or abuse.[5]

In some education systems, teachers may be responsible for student discipline.

Competences and qualities required by teachers

Teaching is a highly complex activity.[6]

This is partially because teaching is a social practice, that takes place in a specific context (time, place, culture, socio-political-economic situation etc.) and therefore is shaped by the values of that specific context.[7] Factors that influence what is expected (or required) of teachers include history and tradition, social views about the purpose of education, accepted theories about learning, etc.[8]

Competences

The competences required by a teacher are affected by the different ways in which the role is understood around the world. Broadly, there seem to be four models:

- the teacher as manager of instruction;

- the teacher as caring person;

- the teacher as expert learner; and

- the teacher as cultural and civic person.[9]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has argued that it is necessary to develop a shared definition of the skills and knowledge required by teachers, in order to guide teachers’ career-long education and professional development.[10] Some evidence-based international discussions have tried to reach such a common understanding. For example, the European Union has identified three broad areas of competences that teachers require:

- Working with others

- Working with knowledge, technology and information, and

- Working in and with society.[11]

Scholarly consensus is emerging that what is required of teachers can be grouped under three headings:

- knowledge (such as: the subject matter itself and knowledge about how to teach it, curricular knowledge, knowledge about the educational sciences, psychology, assessment etc.)

- craft skills (such as lesson planning, using teaching technologies, managing students and groups, monitoring and assessing learning etc.) and

- dispositions (such as essential values and attitudes, beliefs and commitment).[12]

Qualities

Enthusiasm

A teacher interacts with older students at a school in New Zealand.

It has been found that teachers who showed enthusiasm towards the course materials and students can create a positive learning experience.[13] These teachers do not teach by rote but attempt to invigorate their teaching of the course materials every day.[14] Teachers who cover the same curriculum repeatedly may find it challenging to maintain their enthusiasm, lest their boredom with the content bore their students in turn. Enthusiastic teachers are rated higher by their students than teachers who didn’t show much enthusiasm for the course materials.[15]

A primary school teacher on a picnic with her students, Colombia, 2014

Teachers that exhibit enthusiasm are more likely to have engaged, interested and energetic students who are curious about learning the subject matter. Recent research has found a correlation between teacher enthusiasm and students’ intrinsic motivation to learn and vitality in the classroom.[16] Controlled, experimental studies exploring intrinsic motivation of college students has shown that nonverbal expressions of enthusiasm, such as demonstrative gesturing, dramatic movements which are varied, and emotional facial expressions, result in college students reporting higher levels of intrinsic motivation to learn.[17] But even while a teacher’s enthusiasm has been shown to improve motivation and increase task engagement, it does not necessarily improve learning outcomes or memory for the material.[18]

There are various mechanisms by which teacher enthusiasm may facilitate higher levels of intrinsic motivation.[19]

Teacher enthusiasm may contribute to a classroom atmosphere of energy and enthusiasm which feeds student interest and excitement in learning the subject matter.[20] Enthusiastic teachers may also lead to students becoming more self-determined in their own learning process. The concept of mere exposure indicates that the teacher’s enthusiasm may contribute to the student’s expectations about intrinsic motivation in the context of learning. Also, enthusiasm may act as a «motivational embellishment», increasing a student’s interest by the variety, novelty, and surprise of the enthusiastic teacher’s presentation of the material. Finally, the concept of emotional contagion may also apply: students may become more intrinsically motivated by catching onto the enthusiasm and energy of the teacher.[16]

Interaction with learners

Research shows that student motivation and attitudes towards school are closely linked to student-teacher relationships. Enthusiastic teachers are particularly good at creating beneficial relations with their students. Their ability to create effective learning environments that foster student achievement depends on the kind of relationship they build with their students.[21][22][23][24] Useful teacher-to-student interactions are crucial in linking academic success with personal achievement.[25] Here, personal success is a student’s internal goal of improving themselves, whereas academic success includes the goals they receive from their superior. A teacher must guide their student in aligning their personal goals with their academic goals. Students who receive this positive influence show stronger self-confidence and greater personal and academic success than those without these teacher interactions.[24][26][27]

Students are likely to build stronger relations with teachers who are friendly and supportive and will show more interest in courses taught by these teachers.[25][26] Teachers that spend more time interacting and working directly with students are perceived as supportive and effective teachers. Effective teachers have been shown to invite student participation and decision making, allow humor into their classroom, and demonstrate a willingness to play.[22]

Teaching qualifications

In many countries, a person who wishes to become a teacher must first obtain specified professional qualifications or credentials from a university or college. These professional qualifications may include the study of pedagogy, the science of teaching.

Teachers, like other professionals, may have to, or choose to, continue their education after they qualify, a process known as continuing professional development.

The issue of teacher qualifications is linked to the status of the profession. In some societies, teachers enjoy a status on a par with physicians, lawyers, engineers, and accountants, in others, the status of the profession is low. In the twentieth century, many intelligent women were unable to get jobs in corporations or governments so many chose teaching as a default profession. As women become more welcomed into corporations and governments today, it may be more difficult to attract qualified teachers in the future.

Teachers are often required to undergo a course of initial education at a College of Education to ensure that they possess the necessary knowledge, competences and adhere to relevant codes of ethics.

There are a variety of bodies designed to instill, preserve and update the knowledge and professional standing of teachers. Around the world many teachers’ colleges exist; they may be controlled by government or by the teaching profession itself.

They are generally established to serve and protect the public interest through certifying, governing, quality controlling, and enforcing standards of practice for the teaching profession.

Professional standards

The functions of the teachers’ colleges may include setting out clear standards of practice, providing for the ongoing education of teachers, investigating complaints involving members, conducting hearings into allegations of professional misconduct and taking appropriate disciplinary action and accrediting teacher education programs. In many situations teachers in publicly funded schools must be members in good standing with the college, and private schools may also require their teachers to be college members. In other areas these roles may belong to the State Board of Education, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, the State Education Agency or other governmental bodies. In still other areas Teaching Unions may be responsible for some or all of these duties.

Professional misconduct

Misconduct by teachers, especially sexual misconduct, has been getting increased scrutiny from the media and the courts.[28] A study by the American Association of University Women reported that 9.6% of students in the United States claim to have received unwanted sexual attention from an adult associated with education; be they a volunteer, bus driver, teacher, administrator or other adult; sometime during their educational career.[29]

A study in England showed a 0.3% prevalence of sexual abuse by any professional, a group that included priests, religious leaders, and case workers as well as teachers.[30] It is important to note, however, that this British study is the only one of its kind and consisted of «a random … probability sample of 2,869 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 in a computer-assisted study» and that the questions referred to «sexual abuse with a professional,» not necessarily a teacher. It is therefore logical to conclude that information on the percentage of abuses by teachers in the United Kingdom is not explicitly available and therefore not necessarily reliable. The AAUW study, however, posed questions about fourteen types of sexual harassment and various degrees of frequency and included only abuses by teachers. «The sample was drawn from a list of 80,000 schools to create a stratified two-stage sample design of 2,065 8th to 11th grade students». Its reliability was gauged at 95% with a 4% margin of error.

In the United States especially, several high-profile cases such as Debra LaFave, Pamela Rogers Turner, and Mary Kay Letourneau have caused increased scrutiny on teacher misconduct.

Chris Keates, the general secretary of National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers, said that teachers who have sex with pupils over the age of consent should not be placed on the sex offenders register and that prosecution for statutory rape «is a real anomaly in the law that we are concerned about.» This has led to outrage from child protection and parental rights groups.[31] Fears of being labelled a pedophile or hebephile has led to several men who enjoy teaching avoiding the profession.[32] This has in some jurisdictions reportedly led to a shortage of male teachers.[33]

Pedagogy and teaching

Dutch schoolmaster and children, 1662

A primary school teacher in northern Laos

The teacher-student-monument in Rostock, Germany, honors teachers.

Teachers facilitate student learning, often in a school or academy or perhaps in another environment such as outdoors.

GDR «village teacher», a teacher teaching students of all age groups in one class in 1951

Jewish children with their teacher in Samarkand, the beginning of the 20th century

The objective is typically accomplished through either an informal or formal approach to learning, including a course of study and lesson plan that teaches skills, knowledge or thinking skills. Different ways to teach are often referred to as pedagogy. When deciding what teaching method to use teachers consider students’ background knowledge, environment, and their learning goals as well as standardized curricula as determined by the relevant authority. Many times, teachers assist in learning outside of the classroom by accompanying students on field trips. The increasing use of technology, specifically the rise of the internet over the past decade, has begun to shape the way teachers approach their roles in the classroom.

The objective is typically a course of study, lesson plan, or a practical skill. A teacher may follow standardized curricula as determined by the relevant authority. The teacher may interact with students of different ages, from infants to adults, students with different abilities and students with learning disabilities.

Teaching using pedagogy also involve assessing the educational levels of the students on particular skills. Understanding the pedagogy of the students in a classroom involves using differentiated instruction as well as supervision to meet the needs of all students in the classroom. Pedagogy can be thought of in two manners. First, teaching itself can be taught in many different ways, hence, using a pedagogy of teaching styles. Second, the pedagogy of the learners comes into play when a teacher assesses the pedagogic diversity of their students and differentiates for the individual students accordingly. For example, an experienced teacher and parent described the place of a teacher in learning as follows: «The real bulk of learning takes place in self-study and problem solving with a lot of feedback around that loop. The function of the teacher is to pressure the lazy, inspire the bored, deflate the cocky, encourage the timid, detect and correct individual flaws, and broaden the viewpoint of all. This function looks like that of a coach using the whole gamut of psychology to get each new class of rookies off the bench and into the game.»[34]

Perhaps the most significant difference between primary school and secondary school teaching is the relationship between teachers and children. In primary schools each class has a teacher who stays with them for most of the week and will teach them the whole curriculum. In secondary schools they will be taught by different subject specialists each session during the week and may have ten or more different teachers. The relationship between children and their teachers tends to be closer in the primary school where they act as form tutor, specialist teacher and surrogate parent during the course of the day.

This is true throughout most of the United States as well. However, alternative approaches for primary education do exist. One of these, sometimes referred to as a «platoon» system, involves placing a group of students together in one class that moves from one specialist to another for every subject. The advantage here is that students learn from teachers who specialize in one subject and who tend to be more knowledgeable in that one area than a teacher who teaches many subjects. Students still derive a strong sense of security by staying with the same group of peers for all classes.

Co-teaching has also become a new trend amongst educational institutions. Co-teaching is defined as two or more teachers working harmoniously to fulfill the needs of every student in the classroom. Co-teaching focuses the student on learning by providing a social networking support that allows them to reach their full cognitive potential. Co-teachers work in sync with one another to create a climate of learning.

Classroom management

Teachers and school discipline

Throughout the history of education the most common form of school discipline was corporal punishment. While a child was in school, a teacher was expected to act as a substitute parent, with all the normal forms of parental discipline open to them.

Medieval schoolboy birched on the bare buttocks

In past times, corporal punishment (spanking or paddling or caning or strapping or birching the student in order to cause physical pain) was one of the most common forms of school discipline throughout much of the world. Most Western countries, and some others, have now banned it, but it remains lawful in the United States following a US Supreme Court decision in 1977 which held that paddling did not violate the US Constitution.[35]

30 US states have banned corporal punishment, the others (mostly in the South) have not. It is still used to a significant (though declining) degree in some public schools in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas. Private schools in these and most other states may also use it. Corporal punishment in American schools is administered to the seat of the student’s trousers or skirt with a specially made wooden paddle. This often used to take place in the classroom or hallway, but nowadays the punishment is usually given privately in the principal’s office.

Official corporal punishment, often by caning, remains commonplace in schools in some Asian, African and Caribbean countries.

Currently detention is one of the most common punishments in schools in the United States, the UK, Ireland, Singapore and other countries. It requires the pupil to remain in school at a given time in the school day (such as lunch, recess or after school); or even to attend school on a non-school day, e.g. «Saturday detention» held at some schools. During detention, students normally have to sit in a classroom and do work, write lines or a punishment essay, or sit quietly.

A modern example of school discipline in North America and Western Europe relies upon the idea of an assertive teacher who is prepared to impose their will upon a class. Positive reinforcement is balanced with immediate and fair punishment for misbehavior and firm, clear boundaries define what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior.[36] Teachers are expected to respect their students; sarcasm and attempts to humiliate pupils are seen as falling outside of what constitutes reasonable discipline.[37]

Whilst this is the consensus viewpoint amongst the majority of academics, some teachers and parents advocate a more assertive and confrontational style of discipline[38] (refer to Canter Model of Discipline).[39] Such individuals claim that many problems with modern schooling stem from the weakness in school discipline and if teachers exercised firm control over the classroom they would be able to teach more efficiently. This viewpoint is supported by the educational attainment of countries—in East Asia for instance—that combine strict discipline with high standards of education.[40][41][42]

It’s not clear, however that this stereotypical view reflects the reality of East Asian classrooms or that the educational goals in these countries are commensurable with those in Western countries. In Japan, for example, although average attainment on standardized tests may exceed those in Western countries, classroom discipline and behavior is highly problematic. Although, officially, schools have extremely rigid codes of behavior, in practice many teachers find the students unmanageable and do not enforce discipline at all.

Where school class sizes are typically 40 to 50 students, maintaining order in the classroom can divert the teacher from instruction, leaving little opportunity for concentration and focus on what is being taught. In response, teachers may concentrate their attention on motivated students, ignoring attention-seeking and disruptive students. The result of this is that motivated students, facing demanding university entrance examinations, receive disproportionate resources. Given the emphasis on attainment of university places, administrators and governors may regard this policy as appropriate.

Obligation to honor students rights

Sudbury-model democratic schools claim that popularly based authority can maintain order more effectively than dictatorial authority for governments and schools alike. They also claim that in these schools the preservation of public order is easier and more efficient than anywhere else. Primarily because rules and regulations are made by the community as a whole, thence the school atmosphere is one of persuasion and negotiation, rather than confrontation since there is no one to confront. Sudbury model democratic schools’ proponents argue that a school that has good, clear laws, fairly and democratically passed by the entire school community, and a good judicial system for enforcing these laws, is a school in which community discipline prevails, and in which an increasingly sophisticated concept of law and order develops, against other schools today, where rules are arbitrary, authority is absolute, punishment is capricious, and due process of law is unknown.[43][44]

Occupational hazards

Teachers face several occupational hazards in their line of work, including occupational stress, which can negatively impact teachers’ mental and physical health, productivity, and students’ performance. Stress can be caused by organizational change, relationships with students, fellow teachers, and administrative personnel, working environment, expectations to substitute, long hours with a heavy workload, and inspections. Teachers are also at high risk for occupational burnout.[45]

A 2000 study found that 42% of UK teachers experienced occupational stress, twice the figure for the average profession. A 2012 study found that teachers experienced double the rate of anxiety, depression, and stress than average workers.[45]

There are several ways to mitigate the occupational hazards of teaching. Organizational interventions, like changing teachers’ schedules, providing support networks and mentoring, changing the work environment, and offering promotions and bonuses, may be effective in helping to reduce occupational stress among teachers. Individual-level interventions, including stress-management training and counseling, are also used to relieve occupational stress among teachers.[45]

Apart from this, teachers are often not given sufficient opportunities for professional growth or promotions. This leads to some stagnancy, as there is not sufficient interests to enter the profession. An organisation in India called Centre for Teacher Accreditation (CENTA) is working to reduce this hazard, by trying to open opportunities for teachers in India.

Teaching around the world

Math and physics teacher at a junior college in Sweden, in the 1960s

There are many similarities and differences among teachers around the world. In almost all countries teachers are educated in a university or college. Governments may require certification by a recognized body before they can teach in a school. In many countries, elementary school education certificate is earned after completion of high school. The high school student follows an education specialty track, obtain the prerequisite «student-teaching» time, and receive a special diploma to begin teaching after graduation. In addition to certification, many educational institutions especially within the US, require that prospective teachers pass a background check and psychiatric evaluation to be able to teach in classroom. This is not always the case with adult further learning institutions but is fast becoming the norm in many countries as security[25] concerns grow.

International schools generally follow an English-speaking, Western curriculum and are aimed at expatriate communities.[46]

Australia

Education in Australia is primarily the responsibility of the individual states and territories. Generally, education in Australia follows the three-tier model which includes primary education (primary schools), followed by secondary education (secondary schools/high schools) and tertiary education (universities or TAFE colleges).

Canada

Teaching in Canada requires a post-secondary degree Bachelor’s Degree. In most provinces a second Bachelor’s Degree such as a Bachelor of Education is required to become a qualified teacher. Salary ranges from $40,000/year to $90,000/yr. Teachers have the option to teach for a public school which is funded by the provincial government or teaching in a private school which is funded by the private sector, businesses and sponsors.

France

In France, teachers, or professors, are mainly civil servants, recruited by competitive examination.

Germany

In Germany, teachers are mainly civil servants recruited in special university classes, called Lehramtstudien (Teaching Education Studies). There are many differences between the teachers for elementary schools (Grundschule), lower secondary schools (Hauptschule), middle level secondary schools (Realschule) and higher level secondary schools (Gymnasium).

Salaries for teachers depend on the civil servants’ salary index scale (Bundesbesoldungsordnung).

India

In ancient India, the most common form of education was gurukula based on the guru-shishya tradition (teacher-disciple tradition) which involved the disciple and guru living in the same (or a nearby) residence. These gurukulam was supported by public donations and the guru would not accept any fees from the shishya. This organized system stayed the most prominent form of education in the Indian subcontinent until the British invasion. Through strong efforts in 1886 and 1948, the gurukula system was revived in India.[47][48]

The role and success of a teacher in the modern Indian education system is clearly defined. CENTA Standards define the competencies that a good teacher should possess. Schools look for competent teachers across grades. Teachers are appointed directly by schools in private sector, and through eligibility tests in government schools.

Ireland

Salaries for primary teachers in Ireland depend mainly on seniority (i.e. holding the position of principal, deputy principal or assistant principal), experience and qualifications. Extra pay is also given for teaching through the Irish language, in a Gaeltacht area or on an island. The basic pay for a starting teacher is €27,814 p.a., rising incrementally to €53,423 for a teacher with 25 years service. A principal of a large school with many years experience and several qualifications (M.A., H.Dip., etc.) could earn over €90,000.[49]

Teachers are required to be registered with the Teaching Council; under Section 30 of the Teaching Council Act 2001, a person employed in any capacity in a recognised teaching post — who is not registered with the Teaching Council — may not be paid from Oireachtas funds.[50][51]

From 2006 Garda vetting has been introduced for new entrants to the teaching profession. These procedures apply to teaching and also to non-teaching posts and those who refuse vetting «cannot be appointed or engaged by the school in any capacity including in a voluntary role». Existing staff will be vetted on a phased basis.[52][53]

Philippines

To become a teacher in the Philippines, one must have a bachelor’s degree in education. Other degrees are also allowed as long they are able to get 18 units of professional education subjects (10 units for arts and sciences degrees). A board exam must be taken to become a professional teacher in the Philippines. Upon passing the board exam, the Professional Regulatory Commission will issue a teaching licence.[54][55]

United Kingdom

Education in the United Kingdom is a devolved matter with each of the countries of the United Kingdom having separate systems.

England

Salaries for nursery, primary and secondary school teachers ranged from £20,133 to £41,004 in September 2007, although some salaries can go much higher depending on experience and extra responsibilities.[56] Preschool teachers may earn an average salary of £19,543 annually.[57] Teachers in state schools must have at least a bachelor’s degree, complete an approved teacher education program, and be licensed.

Many counties offer alternative licensing programs to attract people into teaching, especially for hard-to-fill positions. Excellent job opportunities are expected as retirements, especially among secondary school teachers, outweigh slowing enrollment growth; opportunities will vary by geographic area and subject taught.[citation needed]

Scotland

In Scotland, anyone wishing to teach must be registered with the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS). Teaching in Scotland is an all graduate profession and the normal route for graduates wishing to teach is to complete a programme of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) at one of the seven Scottish Universities who offer these courses. Once successfully completed, «Provisional Registration» is given by the GTCS which is raised to «Full Registration» status after a year if there is sufficient evidence to show that the «Standard for Full Registration» has been met.[58]

For the salary year beginning April 2008, unpromoted teachers in Scotland earned from £20,427 for a Probationer, up to £32,583 after 6 years teaching, but could then go on to earn up to £39,942 as they complete the modules to earn Chartered Teacher Status (requiring at least 6 years at up to two modules per year.) Promotion to Principal Teacher positions attracts a salary of between £34,566 and £44,616; Deputy Head, and Head teachers earn from £40,290 to £78,642.[59]

Teachers in Scotland can be registered members of trade unions with the main ones being the Educational Institute of Scotland and the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association.

Wales

Education in Wales differs in certain respects from education elsewhere in the United Kingdom. For example, a significant number of students all over Wales are educated either wholly or largely through the medium of Welsh: in 2008/09, 22 per cent of classes in maintained primary schools used Welsh as the sole or main medium of instruction. Welsh medium education is available to all age groups through nurseries, schools, colleges and universities and in adult education; lessons in the language itself are compulsory for all pupils until the age of 16.

Teachers in Wales can be registered members of trade unions such as ATL, NUT or NASUWT and a report in 2010 suggested that the average age of teachers in Wales was falling with teachers being younger than in previous years. It was suggested that a proportion of older teachers had faced discrimination and did not have their experience valued.[60] A growing cause of concern at that time was that attacks on teachers in Welsh schools reached an all-time high between 2005 and 2010.[61]

United States

Students of a U.S. university with their professor on the far right, 2009

In the United States, each state determines the requirements for getting a license to teach in public schools. Teaching certification generally lasts three years, but teachers can receive certificates that last as long as ten years.[62] Public school teachers are required to have a bachelor’s degree and the majority must be certified by the state in which they teach. Many charter schools do not require that their teachers be certified, provided they meet the standards to be highly qualified as set by No Child Left Behind. Additionally, the requirements for substitute/temporary teachers are generally not as rigorous as those for full-time professionals. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are 1.4 million elementary school teachers,[63] 674,000 middle school teachers,[64] and 1 million secondary school teachers employed in the U.S.[65]

In the past, teachers have been paid relatively low salaries. However, average teacher salaries have improved rapidly in recent years. US teachers are generally paid on graduated scales, with income depending on experience. Teachers with more experience and higher education earn more than those with a standard bachelor’s degree and certificate. Salaries vary greatly depending on state, relative cost of living, and grade taught. Salaries also vary within states where wealthy suburban school districts generally have higher salary schedules than other districts. The median salary for all primary and secondary teachers was $46,000 in 2004, with the average entry salary for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree being an estimated $32,000. Median salaries for preschool teachers, however, were less than half the national median for secondary teachers, clock in at an estimated $21,000 in 2004.[66][67][68] For high school teachers, median salaries in 2007 ranged from $35,000 in South Dakota to $71,000 in New York, with a national median of $52,000.[69] Some contracts may include long-term disability insurance, life insurance, emergency/personal leave and investment options.[70]

The American Federation of Teachers’ teacher salary survey for the 2006–07 school year found that the average teacher salary was $51,009.[71] In a salary survey report for K-12 teachers, elementary school teachers had the lowest median salary earning $39,259. High school teachers had the highest median salary earning $41,855.[72] Many teachers take advantage of the opportunity to increase their income by supervising after-school programs and other extracurricular activities. In addition to monetary compensation, public school teachers may also enjoy greater benefits (like health insurance) compared to other occupations. Merit pay systems are on the rise for teachers, paying teachers extra money based on excellent classroom evaluations, high test scores and for high success at their overall school. Also, with the advent of the internet, many teachers are now selling their lesson plans to other teachers through the web in order to earn supplemental income, most notably on TeachersPayTeachers.com.[73] The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 also aims to substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers through international cooperation by 2030 in an effort to improve the quality of teaching around the world.[74]

Assistant teachers

Assistant teachers are additional teachers assisting the primary teacher, often in the same classroom. There are different types around the world, as well as a variety of formal programs defining roles and responsibilities.

One type is a Foreign Language Assistant, which in Germany is run by the Educational Exchange Service (Pädagogischer Austauschdienst).

British schools employ teaching assistants, who are not considered fully qualified teachers, and as such, are guided by teachers but may supervise and teach groups of pupils independently. In the United Kingdom, the term «assistant teacher» used to be used to refer to any qualified or unqualified teacher who was not a head or deputy head teacher.[original research?]

The Japanese education system employs Assistant Language Teachers in elementary, junior high and high schools.

Learning by teaching (German short form: LdL) is a method which allows pupils and students to prepare and teach lessons or parts of lessons, with the understanding that a student’s own learning is enhanced through the teaching process.

See also

- AI teaching assistant

- Bullying in teaching

- Certified teacher

- School of education

- Student teacher

- Substitute teacher

- Teacher Support Network (in the UK)

- Education policy#Teacher policy

References

- ^ Williamson McDiarmid, G. & Clevenger-Bright M. (2008), ‘Rethinking Teacher Capacity’, in Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S. & Mc Intyre, D. (Eds.): Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. Enduring questions in changing contexts. New York/Abingdon: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- ^ «Transfer to». Aft.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Kollerová, L. (2022). «Teachers can make a difference in bullying: Effects of teacher interventions on students’ adoption of bully, victim, bully-victim or defender roles across time». Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 51 (12): 2312–2327. doi:10.1007/s10964-022-01674-6. ISSN 0047-2891. PMC 9596519. PMID 36053439. S2CID 252009527.

- ^ Burger, C. (2022). «School bullying is not a conflict: The interplay between conflict management styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment». International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (18): 11809. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811809. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 9517642. PMID 36142079.

- ^ Briggs, F., Hawkins, R. (2020). Child Protection: A guide for teachers and child care professionals. Routledge. ISBN 9781003134701.

- ^ For a review of literature on competences required by teachers, see F Caena (2011) ‘Literature review: Teachers’ core competences:

requirements and development’ accessed January 2017 at «Homepage | European Education Area» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017. - ^ for a useful discussion see, for example: Cochran-Smith, M. (2006): ‘Policy, Practice, and Politics in Teacher Education’, Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press

- ^ see for example Cummings, W.K. (2003) ‘The Institutions of Education. A Comparative Study of Educational Development in the Six Core Nations’, Providence, MA:

Symposium Books. - ^ F Caena (2011) ‘Literature review: Teachers’ core competences: requirements and development’ accessed January 2017 at «Homepage | European Education Area» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017. citing Altet et al., 1996; Conway et al., 2010; Hansen, 2008; Seifert, 1999; Sockett, 2008

- ^ ‘Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers’, 2005, Paris: OECD publications [1] Archived 30 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ F Caena (2011) ‘Literature review: Teachers’ core competences: requirements and development’ accessed January 2017 at «Homepage | European Education Area» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Williamson McDiarmid, G. & Clevenger-Bright M. (2008) ‘Rethinking Teacher Capacity’, in Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S. & Mc Intyre, D. (Eds.). ‘Handbook of Research on

Teacher Education. Enduring questions in changing contexts’. New York/Abingdon: Routledge/Taylor & Francis cited in F Caena (2011) - ^ Teaching Patterns: a Pattern Language for Improving the Quality of Instruction in Higher Education Settings by Daren Olson. Page 96

- ^ Motivated Student: Unlocking the Enthusiasm for Learning by Bob Sullo. Page 62

- ^ Barkley, S., & Bianco, T. (2006). The Wonder of Wows. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 42(4), 148-151.

- ^ a b Patrick, B.C., Hisley, J. & Kempler, T. (2000) «What’s Everybody so Excited about?»: The Effects of Teacher Enthusiasm on Student Intrinsic Motivation and Vitality», The Journal of Experimental Education, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 217–236

- ^ Brooks, Douglas M. (1985). «The Teacher’s Communicative Competence: The First Day of School». Theory into Practice. 24 (1): 63. doi:10.1080/00405848509543148.

- ^ Motz, B. A.; de Leeuw, J. R.; Carvalho, P. F.; Liang, K. L.; Goldstone, R. L. (2017). «A dissociation between engagement and learning: Enthusiastic instructions fail to reliably improve performance on a memory task». PLOS ONE. 12 (7): e0181775. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1281775M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181775. PMC 5521834. PMID 28732087.

- ^ All Of Us Should Be Teachers, Even If Just For One Day Archived 9 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post, 27 September 2016

- ^ Amatora, M. (1950). Teacher Personality: Its Influence on Pupils. Education, 71(3), 154-158

- ^ Baker, J. A., Terry, T., Bridger, R., & Winsor, A. (1997). Schools as caring communities: A relational approach to school reform. School Psychology Review, 26, 576-588.

- ^ a b Bryant, Jennings . 1980. Relationship between college teachers’ use of humor in the classroom and students’ evaluations of their teachers. Journal of educational psychology. 72, 4.

- ^ Fraser, B. J., & Fisher, D. L. (1982). Predicting students’ outcomes from their perceptions of classroom psychosocial environment. American Educational Research Journal, 19, 498- 518.

- ^ a b Hartmut, J. (1978). Supportive dimensions of teacher behavior in relationship to pupil emotional cognitive processes. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 25, 69-74.

- ^ a b c Osborne, E.;. Salzberger, I.; Wittenberg, G. W. 1999. The Emotional Experience of Learning and Teaching. Karnac Books, London.

- ^ a b Baker, J. A.Teacher-Student Interaction in Urban At-Risk Classrooms: Differential Behavior, Relationship Quality, and Student Satisfaction with School. The Elementary School Journal Volume 100, Number 1, 1999 by The University of Chicago.

- ^ Moos, R. H. (1979). Evaluating Educational Environments: Measures, procedures, findings, and policy implications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Goorian, Brad (December 1999). «Sexual Misconduct by School Employees» (PDF). ERIC Digest (134): 1. ERIC #: ED436816. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Charol (June 2004). «Educator Sexual Misconduct: A Synthesis of Existing Literature» (PDF). U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Under Secretary. p. 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ Educator Sexual Misconduct: A Synthesis of Existing Literature Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine see page 8 and page 20

- ^ «Union Official: Teachers Who Engage in Consensual Sex With Teen Pupils Shouldn’t Face Prosecution». Fox News. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- ^ Kissen, Rita (2002). Getting Ready for Benjamin: Preparing Teachers for Sexual Diversity in the classroom. p. 62.

- ^ «7.30 Report — 10/12/1999: Shortage of male primary school teachers». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 August 2003. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ Walter Evans (1965) letter to Roy Glasgow of Naval Postgraduate School, quoted by his son Gregory Walter Evans (December 2004) «Bringing Root Locus to the Classroom», IEEE Control Systems Magazine, page 81

- ^ «Ingraham v. Wright». Bucknell.edu. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Kollerová, L. (2022). «Teachers can make a difference in bullying: Effects of teacher interventions on students’ adoption of bully, victim, bully-victim or defender roles across time». Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 51 (12): 2312–2327. doi:10.1007/s10964-022-01674-6. ISSN 0047-2891. PMC 9596519. PMID 36053439. S2CID 252009527.

- ^ «Maintaining Classroom Discipline» (PDF). Federal Education Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Tauber, Robert T. (2007). Classroom Management: Sound Theory and Effective Practice. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 112. ISBN 9780275996680.

- ^ Charles, C.M (2005). «Building Classroom Discipline» (PDF). University of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Baumann, Chris (2016). «School discipline, school uniforms and academic performance». International Journal of Educational Management. 30 (6): 1003–1029. doi:10.1108/IJEM-09-2015-0118.

- ^ Sui-chu Ho, Esther (2009). «Characteristics of East Asian Learners: What We Learned From PISA» (PDF). hkier.fed.cuhk.edu.hk/. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Munro, Kelsey (November 2016). «Strict classroom discipline improves student outcomes and work ethic, studies find». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018.

- ^ The Crisis in American Education — An Analysis and a Proposal, The Sudbury Valley School Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1970), Law and Order: Foundations of Discipline Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine (pg. 49-55). Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ Greenberg, D. (1987) The Sudbury Valley School Experience «Back to Basics — Political basics.» Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Knowing all this, we would expect; nay, insist (one would think) that the schools, in training their students to contribute productively to the political stability and growth of America, would be democratic and non-autocratic; be governed by clear rules and due process; be guardians of individual rights of students. A student growing up in schools having these features would be ready to move right into society at large. I think it is safe to say that the individual liberties so cherished by our ancestors and by each succeeding generation will never be really secure until our youth, throughout the crucial formative years of their minds and spirits, are nurtured in a school environment that embodies these basic American truths.

Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Naghieh, Ali; Montgomery, Paul; Bonell, Christopher P.; Thompson, Marc; Aber, J. Lawrence (2015). «Organisational interventions for improving wellbeing and reducing work-related stress in teachers» (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD010306. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010306.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25851427. S2CID 205204278. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Teachers International Consultancy (17 July 2008). «Teaching at international schools is not TEFL». Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Madalsa Ujjwal, 2008, «Swami Dayanand Saraswati Life and Ideas», Book Treasure Publications, Jodhpur, pp. 96–97

- ^ Joshi, Ankur; Gupta, Rajen K. (July 2017). «Elementary education in Bharat (that is India): insights from a postcolonial ethnographic study of a Gurukul». International Journal of Indian Culture and Business Management.

- ^ «Circular 0040/2011 (New Pay Scales for New Appointees to Teaching in 2011)» (PDF). Department of Education, Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ «Requirement For Teachers To Be Registered With The Teaching Council Under Section 30 Of The Teaching Council Act, 2001». Department of Education and Skills, Ireland. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ «Teaching Council Act, 2001». Office of the Attorney General, Ireland. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ «New arrangements for the vetting of teaching and non-teaching staff». Department of Education and Science, Ireland. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ «Recruitment procedures – requirements for Garda vetting». Department of Education and Science, Ireland. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ «TEACHER». Professional Regulatory Commission, Philippines. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ «How To Become A Teacher In The Philippines». Bukas. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ «‘Teacher Salaries from September 2007’ TDA (Training and Development Agency)» (PDF). Tda.gov.uk. 31 March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «Preschool Teacher Salaries in the United Kingdom». indeed. July 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Training to be a teacher Archived 29 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine GTC Scotland

- ^ «Scotland: Headteachers and deputy headteachers’ pay». Tes. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ «Wales’ teachers ‘getting younger’«. BBC News. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ «Attacks on teachers in Wales on the rise». BBC News. 7 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010.

- ^ «Teacher certification». Teacherportal.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «Elementary School Teachers, Except Special Education». Bls.gov. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «Middle School Teachers, Except Special and Vocational Education». Bureau of Labor Statistics. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «Secondary School Teachers, Except Special and Vocational Education». Bls.gov. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «Downloads and 2019 Wage Data». American Federation of Teachers. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ «Preschool Teachers». Occupational Outlook Handbook. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ «U.S. Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics. (July 18, 2007). Teachers—Preschool, Kindergarten, Elementary, Middle, and Secondary: Earnings«. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- ^ «Spotlight on Statistics: Back to School». Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- ^ «Make It Happen: A Student’s Guide,» Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine National Education Association. Retrieved 7/5/07.

- ^ 2007 «Survey & Analysis of Teacher Salary Trends,» Archived 16 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine American Federation of Teachers. Retrieved 8/7/10.

- ^ 2008 «Teacher Salary- Average Teacher Salaries» Archived 13 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine PayScale. Retrieved 9/16/08.

- ^ Hu, Winnie (14 November 2009). «Selling Lessons Online Raises Cash and Questions». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ «SDG4’s 10 targets». Global Campaign For Education. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

External links

- Dictionary

- T

- Teacher

Transcription

-

- US Pronunciation

- US IPA

- UK Pronunciation

- UK IPA

-

- [tee-cher]

- /ˈti tʃər/

- /ˈtiːtʃə(r)/

-

- US Pronunciation

- US IPA

-

- [tee-cher]

- /ˈti tʃər/

Definitions of teacher word

- noun teacher a person who teaches or instructs, especially as a profession; instructor. 1

- noun teacher instructor 1

- noun teacher professor 1

- noun teacher master 1

- countable noun teacher A teacher is a person who teaches, usually as a job at a school or similar institution. 0

- noun teacher a person whose occupation is teaching others, esp children 0

Information block about the term

Origin of teacher

First appearance:

before 1250

One of the 11% oldest English words

First recorded in 1250-1300, teacher is from the Middle English word techer. See teach, -er1

Historical Comparancy

Parts of speech for Teacher

teacher popularity

A common word. It’s meaning is known to most children of preschool age. About 99% of English native speakers know the meaning and use the word.

Most Europeans know this English word. The frequency of it’s usage is somewhere between «mom» and «screwdriver».

Synonyms for teacher

noun teacher

- advisor — one who gives advice.

- annalist — a writer of annals

- bandleader — A bandleader is the person who conducts a band, especially a jazz band.

- buttinski — a person who interferes in the affairs of others; meddler.

Antonyms for teacher

noun teacher

- apprentice — An apprentice is a young person who works for someone in order to learn their skill.

- beginner — A beginner is someone who has just started learning to do something and cannot do it very well yet.

- catechumen — a person, esp in the early Church, undergoing instruction prior to baptism

- grad — one hundredth of a right angle.

- greenie — Slang. an amphetamine pill, especially one that is green in color.

Top questions with teacher

- how much do teacher make?

- how much do a teacher make?

- how to become a teacher?

- how much does a teacher make?

- when is teacher appreciation week?

- how do you spell teacher?

- when is teacher appreciation day?

- how much do teacher get paid?

- how to become a substitute teacher?

- how much does teacher get paid?

- how much does high school teacher make?

- how much does a teacher make a year?

- how much do a teacher make a year?

- how to be a teacher?

- how much money does a teacher make?

See also

- All definitions of teacher

- Synonyms for teacher

- Antonyms for teacher

- Related words to teacher

- Sentences with the word teacher

- teacher pronunciation

- The plural of teacher

Matching words

- Words starting with t

- Words starting with te

- Words starting with tea

- Words starting with teac

- Words starting with teach

- Words starting with teache

- Words starting with teacher

- Words ending with r

- Words ending with er

- Words ending with her

- Words ending with cher

- Words containing the letters t

- Words containing the letters t,e

- Words containing the letters t,e,a

- Words containing the letters t,e,a,c

- Words containing the letters t,e,a,c,h

- Words containing the letters t,e,a,c,h,r

- Words containing t

- Words containing te

- Words containing tea

- Words containing teac

- Words containing teach

- Words containing teache

1

: one that teaches

especially

: one whose occupation is to instruct

2

: a Mormon ranking above a deacon in the Aaronic priesthood

Synonyms

Example Sentences

Experience is a good teacher.

She is a first-grade teacher.

a teacher of driver’s education

Recent Examples on the Web

My first organ teacher taught me how to practice efficiently.

—

An unidentified body was found Saturday evening in the car of a Port Orange teacher who was last seen in October 2020, said the Volusia County Sheriff’s Department.

—

At least, that’s the explanation one Texas mom offered her daughter’s first-grade teacher.

—

The Reverend Danny Bryant, a former teacher at the Covenant School, noted that the expulsion of the legislators was taking place on Maundy Thursday, when Jesus was betrayed.

—

Saba Ansari, a teacher at Bridge Builder Academy in Richardson, wants to demystify science for her students right from the start.

—

In January, the district told teachers that everyone would be required to use the names and pronouns listed for students in the database.

—

Courses are taught by experienced artists and teachers, and online profiles of all instructors provide you with info about their expertise and portfolios.

—

But teachers are not trained to give that help.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘teacher.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

First Known Use

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Time Traveler

The first known use of teacher was

in the 14th century

Dictionary Entries Near teacher

Cite this Entry

“Teacher.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/teacher. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on teacher

Last Updated:

11 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged