Skip to content

The History of Stress

We hear the word “stress” all the time, but where did it come from?

KEY POINTS

- The term “stress” emerged out of the field of engineering to describe the actual physical strain put on a structure, but has now been broadened.

- Selye (1936) discovered that after a rat was exposed to a stressor, a typical “syndrome” appeared which was not related to the physical damage.

- The stress response proposed by Selye (1976) suggested that three interdependent elements accompanied any specific stressor.

The notion of “stress” is ingrained in both academic and public discourse, creating a popular phenomenological term that is rarely defined. As accurately noted by Selye (1976), the founder of the term as we know it today, “everybody knows what stress is and nobody knows what it is” (p. 692).

The term “stress” emerged out of the field of engineering to describe the actual physical strain put on a structure. In the mid-1930s, however, the paper “A Syndrome Produced by Diverse Nocuous Agents” was published in Nature (Selye, 1936), which discussed experiments on rats who were given “acute non-specific nocuous agents,” or, “stressors,” which included exposure to cold, surgical injury, spinal shock, excessive muscular exercise, or sub-lethal drug administration.

Selye’s discovery

Selye’s discovery

In his investigation, Selye (1936) discovered that after a rat was exposed to a stressor, a typical “syndrome” appeared which was not related to the physical damage done by the stressor. Selye noted that regardless of the type of stressor to which the rats were exposed, two stages emerged after exposure: In the first stage, 6-48 hours after the initial injury, amongst a myriad of symptoms, rats experienced a notable decrease in size of the thymus (the organ responsible for producing T cells, critical to immunity strategies). In the second stage, beginning at 48 hours after the initial injury, it seemed the brain structures responsible for the production of the organism’s growth ceased to function in favor of other structures which would be more greatly needed, economizing the body’s resources. Selye’s work would be seminal in exploring the biomarkers of stress and provide a catalyst for stress research in general.

Emerging from this study, the stress response proposed by Selye (1976) suggested that three interdependent elements accompanied any specific stressor. These were: hypertrophy in the adrenal cortex (essentially an enlargement in the structure of the brain which stimulates androgen glucocorticoid production), atrophy in the lymphatic system (responsible for the defense of the immune system), and gastrointestinal ulcers.

The GAS model

In noting the abundant health issues derived from “stress,” Selye (1976; 1980) developed the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) model, which suggested that the odd behavioral and physiological reactions to stress are caused by disrupting homeostasis, the body’s natural balance. The GAS model accounts for three distinct phases that activate when one is under stress: the alarm reaction (made up of the “shock” and “anti-shock” phase), resistance stage, and exhaustion stage.

Within homeostasis, the body adapts to minor stressors, however when a stressor exceeds the amount of adaptation given in homeostasis, the body enters into the shock phase of the first stage, alarm, where cells in the hypothalamus begin to activate, the sympathetic nervous system (which regulates the body’s “sympathico- adrenal system,” otherwise known as the “fight or flight” response) is suppressed.

However, in the “anti-shock” phase, when the stressor persists, the sympathetic nervous system is activated, and the “fight or flight” reaction occurs in an attempt to best mobilize the body’s resources in case of danger. This occurs through the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenalcortical (HPA) axis.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related Posts

Title

The system of word

accentuation inherited from PG underwent no changes in Early OE.

In

OE a syllable was made prominent by an increase in the force of

articulation; in other words, a dynamic or a force stress was

employed. In disyllabic and polysyllabic words the accent fell on the

root-morpheme or on the first syllable. Word stress was fixed; it

remained on the same syllable in different grammatical forms of the

words, and, as a rule, did not shift in word-building either. For

example, the Nom.

hlāford,

cyning,

Dat. hlāforde,

cyninge.

Polysyllabic

words, especially compounds, may have had 2 stresses, chief and

secondary, the chief stress being fixed on the first root-morpheme,

and the secondary stress on the second. For example, Norðmonna,

here the chief stress falls on the first component, while the second

component gets the secondary stress; the Gen. plural ending – a is

unstressed.

In

words with prefixes the position of the stress varied: verb prefixes

were unaccented, while in nouns and adjectives the stress was

commonly fixed on the prefix:

ā-`

risan, `mis-dæd

Old English Vowel System

The

system of OE vowels in the 9th

and 10th

centuries is shown below:

Monophthongs

|

Short |

Long |

Front vowels

|

[i] [y] [e] |

[i:] [y:] [e:] |

Back vowels

|

[u] [o] [a] [a]

[o]

cann |

[u:] [o:] [a:] |

Diphthongs

|

[ea] |

[ea:] |

|

[eo] |

[eo:] |

|

[io] |

[io:] |

|

[ie] |

[[ie:] |

OE

vowels underwent different kinds of alterations: qualitative

and quantitative, dependent and independent. In

accented syllables the oppositions between vowels were clearly

maintained. In unaccented positions the original contrasts between

vowels was weakened or lost; the distinction of short and long vowels

was neutralised so that by the age of writing the long vowels in

unstressed syllables had been shortened. As for originally short

vowels, they tended to be reduced to a neutral sound, losing their

qualitative distinctions and were often dropped in unstressed final

syllables.

Changes in the system of vowels:

1)

Fracture/breaking

(преломление)

– diphthongization of short vowels ‘a’, ‘e’ before the

clusters: ‘r+ con.’, ‘l + con.’, ‘ h+ con., final ‘ h’:

ærm – earm, herte – heorte, selh – seolh;

2)

Gradation /ablaut:

(alternation of vowels in different grammatical forms: in strong

verbs: Infinitive (giban),

Past. sing. (gaf),

Past Pl. (gebum),

Second Part. (gibans);

3)Palatalisation:

diphthongisation of vowels under the influence of the initial palatal

consonants ‘g’, ‘c’ (before front vowels) and the cluster

‘sc’ (all vowels): gefan – giefan, scacan – sceacan;

4)

Mutation/Umlaut

(перегласовка) — a change of vowel caused by partial

assimilation to the following vowel: i-mutation

– caused by ‘i’, ‘j’ of the following syllable: namnian –

nemnan, fullian- fyllan; back/velar

mutation

– phonetic change caused by a back vowel (u, o, a) of the following

syllable, which resulted in the diphthongisation of the preceding

vowel: hefon – heofon;

5)

Contraction:

if, after a consonant had dropped, two vowels met inside a word, they

were usually contracted into one long vowel: slahan – sleahan –

sle:an;

6)

Lengthening of Vowels:

before ‘nd’, ‘ld, ‘mb’: bindan – bīndan; climban –

clīmban

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

History of stress

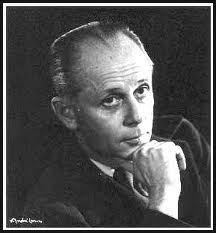

The term stress was borrowed from the field of physics by one of the fathers of stress research Hans Selye. In physics, stress describes the force that produces strain on a physical body (i.e.: bending a piece of metal until it snaps occurs because of the force, or stress, exerted on it).

Hans Selye began using the term stress after completing his medical training at the University of Montreal in the 1920’s. He noticed that no matter what his hospitalized patients suffered from, they all had one thing in common. They all looked sick. In his view, they all were under physical stress.

He proposed that stress was a non-specific strain on the body caused by irregularities in normal body functions. This stress resulted in the release of stress hormones. He called this the “General Adaptation Syndrom” (a closer look at general adaptation syndrome, our body’s short-term and long-term reactions to stress).

The Great Debate

Selye pioneered the field of stress research and provided convincing arguments that stress impacted health. But not all agreed with his physiological view of stress as a non-specific phenomenon though. What about psychological stress?(i.e.: loss of the beloved, frustration, tending to an ill child, or work problems)? Could these situations also be stressful? Many physicians, psychologists, and researchers thought so.

A physician named John Mason conducted an experiment in which two groups of monkeys were deprived of food for a short period of time.

In group 1, monkeys were alone, while in group 2, monkeys watched others receive food. Even though both groups of monkeys were under the physical stress of hunger, those that saw others eat had higher stress hormone levels. He therefore showed that psychological stress was as powerful as physical stress at inducing the body’s stress response.

Many argued that if stress was a non-specific phenomenon then everyone should react the same way to the same stressors. BUT this did not seem right. Many were also convinced that there had to be common elements that would elevate everyone’s stress hormone levels.

In one interesting experiment, researchers measured the stress hormone levels of experienced parachute jumpers.

Jumping out of a plane surely had to be stressful! Strangely, their stress hormone levels were normal.

Stress hormone levels were then measured in both people jumping for the first time and their instructors. They found a big difference! On the day before the jump, student’s levels were normal while instructors’ levels were very high. On the jump day, students’ levels were very high, while instructor’s levels were normal.

They concluded that 24 hours before the jump, the instructors’ anticipation resulted in higher stress hormone levels because they knew what to expect. The students were oblivious!

But on jump day, the novelty and unpredictability of the situation made the students stress hormone levels sky rocket!

Over the next 30 years researchers conducted experiments showing that although the type of stressors resulting in the release of stress hormones are different for everyone there are common elements to situations that elevate stress hormones in everyone.

In essence, they discovered the recipe for stress: N.U.T.S.!

Novelty

Unpredictability

Threat to the ego

Sense of Control

Close-up on …The General Adaptation Syndrome

In Hans Selye’s theory, General Adaptation Syndrome had three stages.

Stage 1 : Alarm reaction

This is the immediate reaction to a stressor. In the initial phase of stress, humans exhibit a “fight or flight” response. This stage takes energy away from other systems (e.g. immune system) increasing our vulnerability to illness.

Did you know? |

| Hans Selye pioneered the field of stress research and provided arguments that stress impacted health. |

Stage 2 : Resistance

If alarm reactions continue, the body begins getting used to being stressed. But this adaptation is not good for your health, since energy is concentrated on stress reactions.

Stage 3 : Exhaustion

This is the final stage after long-term exposure to a stressor. The body’s resistance to stress is gradually reduced and collapses as the immune system becomes ineffective. In Selye’s view, patients who experience long-term stress could succumb to heart attacks or severe infection due to their reduced resistance to illness.

For other uses, see Stress.

| Primary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˈ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 501 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˈ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02C8 |

| Secondary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˌ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 502 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˌ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02CC |

In linguistics, and particularly phonology, stress or accent is the relative emphasis or prominence given to a certain syllable in a word or to a certain word in a phrase or sentence. That emphasis is typically caused by such properties as increased loudness and vowel length, full articulation of the vowel, and changes in tone.[1][2] The terms stress and accent are often used synonymously in that context but are sometimes distinguished. For example, when emphasis is produced through pitch alone, it is called pitch accent, and when produced through length alone, it is called quantitative accent.[3] When caused by a combination of various intensified properties, it is called stress accent or dynamic accent; English uses what is called variable stress accent.

Since stress can be realised through a wide range of phonetic properties, such as loudness, vowel length, and pitch (which are also used for other linguistic functions), it is difficult to define stress solely phonetically.

The stress placed on syllables within words is called word stress. Some languages have fixed stress, meaning that the stress on virtually any multisyllable word falls on a particular syllable, such as the penultimate (e.g. Polish) or the first (e.g. Finnish). Other languages, like English and Russian, have lexical stress, where the position of stress in a word is not predictable in that way but lexically encoded. Sometimes more than one level of stress, such as primary stress and secondary stress, may be identified.

Stress is not necessarily a feature of all languages: some, such as French and Mandarin, are sometimes analyzed as lacking lexical stress entirely.

The stress placed on words within sentences is called sentence stress or prosodic stress. That is one of the three components of prosody, along with rhythm and intonation. It includes phrasal stress (the default emphasis of certain words within phrases or clauses), and contrastive stress (used to highlight an item, a word or part of a word, that is given particular focus).

Phonetic realization[edit]

There are various ways in which stress manifests itself in the speech stream, and they depend to some extent on which language is being spoken. Stressed syllables are often louder than non-stressed syllables, and they may have a higher or lower pitch. They may also sometimes be pronounced longer. There are sometimes differences in place or manner of articulation. In particular, vowels in unstressed syllables may have a more central (or «neutral») articulation, and those in stressed syllables have a more peripheral articulation. Stress may be realized to varying degrees on different words in a sentence; sometimes, the difference is minimal between the acoustic signals of stressed and those of unstressed syllables.

Those particular distinguishing features of stress, or types of prominence in which particular features are dominant, are sometimes referred to as particular types of accent: dynamic accent in the case of loudness, pitch accent in the case of pitch (although that term usually has more specialized meanings), quantitative accent in the case of length,[3] and qualitative accent in the case of differences in articulation. They can be compared to the various types of accent in music theory. In some contexts, the term stress or stress accent specifically means dynamic accent (or as an antonym to pitch accent in its various meanings).

A prominent syllable or word is said to be accented or tonic; the latter term does not imply that it carries phonemic tone. Other syllables or words are said to be unaccented or atonic. Syllables are frequently said to be in pretonic or post-tonic position, and certain phonological rules apply specifically to such positions. For instance, in American English, /t/ and /d/ are flapped in post-tonic position.

In Mandarin Chinese, which is a tonal language, stressed syllables have been found to have tones that are realized with a relatively large swing in fundamental frequency, and unstressed syllables typically have smaller swings.[4] (See also Stress in Standard Chinese.)

Stressed syllables are often perceived as being more forceful than non-stressed syllables.

Word stress[edit]

Word stress, or sometimes lexical stress, is the stress placed on a given syllable in a word. The position of word stress in a word may depend on certain general rules applicable in the language or dialect in question, but in other languages, it must be learned for each word, as it is largely unpredictable. In some cases, classes of words in a language differ in their stress properties; for example, loanwords into a language with fixed stress may preserve stress placement from the source language, or the special pattern for Turkish placenames.

Non-phonemic stress[edit]

In some languages, the placement of stress can be determined by rules. It is thus not a phonemic property of the word, because it can always be predicted by applying the rules.

Languages in which the position of the stress can usually be predicted by a simple rule are said to have fixed stress. For example, in Czech, Finnish, Icelandic, Hungarian and Latvian, the stress almost always comes on the first syllable of a word. In Armenian the stress is on the last syllable of a word.[5] In Quechua, Esperanto, and Polish, the stress is almost always on the penult (second-last syllable). In Macedonian, it is on the antepenult (third-last syllable).

Other languages have stress placed on different syllables but in a predictable way, as in Classical Arabic and Latin, where stress is conditioned by the structure of particular syllables. They are said to have a regular stress rule.

Statements about the position of stress are sometimes affected by the fact that when a word is spoken in isolation, prosodic factors (see below) come into play, which do not apply when the word is spoken normally within a sentence. French words are sometimes said to be stressed on the final syllable, but that can be attributed to the prosodic stress that is placed on the last syllable (unless it is a schwa, when stress is placed on the second-last syllable) of any string of words in that language. Thus, it is on the last syllable of a word analyzed in isolation. The situation is similar in Standard Chinese. French (some authors add Chinese[6]) can be considered to have no real lexical stress.

Phonemic stress[edit]

With some exceptions above, languages such as Germanic languages, Romance languages, the East and South Slavic languages, Lithuanian, as well as others, in which the position of stress in a word is not fully predictable, are said to have phonemic stress. Stress in these languages is usually truly lexical and must be memorized as part of the pronunciation of an individual word. In some languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Lakota and, to some extent, Italian, stress is even represented in writing using diacritical marks, for example in the Spanish words célebre and celebré. Sometimes, stress is fixed for all forms of a particular word, or it can fall on different syllables in different inflections of the same word.

In such languages with phonemic stress, the position of stress can serve to distinguish otherwise identical words. For example, the English words insight () and incite () are distinguished in pronunciation only by the fact that the stress falls on the first syllable in the former and on the second syllable in the latter. Examples from other languages include German Tenor ([ˈteːnoːɐ̯] «gist of message» vs. [teˈnoːɐ̯] «tenor voice»); and Italian ancora ([ˈaŋkora] «anchor» vs. [aŋˈkoːra] «more, still, yet, again»).

In many languages with lexical stress, it is connected with alternations in vowels and/or consonants, which means that vowel quality differs by whether vowels are stressed or unstressed. There may also be limitations on certain phonemes in the language in which stress determines whether they are allowed to occur in a particular syllable or not. That is the case with most examples in English and occurs systematically in Russian, such as за́мок ([ˈzamək], «castle») vs. замо́к ([zɐˈmok], «lock»); and in Portuguese, such as the triplet sábia ([ˈsaβjɐ], «wise woman»), sabia ([sɐˈβiɐ], «knew»), sabiá ([sɐˈβja], «thrush»).

Dialects of the same language may have different stress placement. For instance, the English word laboratory is stressed on the second syllable in British English (labóratory often pronounced «labóratry», the second o being silent), but the first syllable in American English, with a secondary stress on the «tor» syllable (láboratory often pronounced «lábratory»). The Spanish word video is stressed on the first syllable in Spain (vídeo) but on the second syllable in the Americas (video). The Portuguese words for Madagascar and the continent Oceania are stressed on the third syllable in European Portuguese (Madagáscar and Oceânia), but on the fourth syllable in Brazilian Portuguese (Madagascar and Oceania).

Compounds[edit]

With very few exceptions, English compound words are stressed on their first component. Even the exceptions, such as mankínd,[7] are instead often stressed on the first component by some people or in some kinds of English.[8] The same components as those of a compound word are sometimes used in a descriptive phrase with a different meaning and with stress on both words, but that descriptive phrase is then not usually considered a compound: bláck bírd (any bird that is black) and bláckbird (a specific bird species) and páper bág (a bag made of paper) and páper bag (very rarely used for a bag for carrying newspapers but is often also used for a bag made of paper).[9]

Levels of stress[edit]

Some languages are described as having both primary stress and secondary stress. A syllable with secondary stress is stressed relative to unstressed syllables but not as strongly as a syllable with primary stress : for example, saloon and cartoon both have the main stress on the last syllable, but whereas cartoon also has a secondary stress on the first syllable, saloon does not. As with primary stress, the position of secondary stress may be more or less predictable depending on language. In English, it is not fully predictable, but the different secondary stress of the words organization and accumulation (on the first and second syllable, respectively) is predictable due to the same stress of the verbs órganize and accúmulate. In some analyses, for example the one found in Chomsky and Halle’s The Sound Pattern of English, English has been described as having four levels of stress: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary, but the treatments often disagree with one another.

Peter Ladefoged and other phoneticians have noted that it is possible to describe English with only one degree of stress, as long as prosody is recognized and unstressed syllables are phonemically distinguished for vowel reduction.[10] They find that the multiple levels posited for English, whether primary–secondary or primary–secondary–tertiary, are not phonetic stress (let alone phonemic), and that the supposed secondary/tertiary stress is not characterized by the increase in respiratory activity associated with primary/secondary stress in English and other languages. (For further detail see Stress and vowel reduction in English.)

Prosodic stress[edit]

| Extra stress |

|---|

| ˈˈ◌ |

Prosodic stress, or sentence stress, refers to stress patterns that apply at a higher level than the individual word – namely within a prosodic unit. It may involve a certain natural stress pattern characteristic of a given language, but may also involve the placing of emphasis on particular words because of their relative importance (contrastive stress).

An example of a natural prosodic stress pattern is that described for French above; stress is placed on the final syllable of a string of words (or if that is a schwa, the next-to-final syllable). A similar pattern is found in English (see § Levels of stress above): the traditional distinction between (lexical) primary and secondary stress is replaced partly by a prosodic rule stating that the final stressed syllable in a phrase is given additional stress. (A word spoken alone becomes such a phrase, hence such prosodic stress may appear to be lexical if the pronunciation of words is analyzed in a standalone context rather than within phrases.)

Another type of prosodic stress pattern is quantity sensitivity – in some languages additional stress tends to be placed on syllables that are longer (moraically heavy).

Prosodic stress is also often used pragmatically to emphasize (focus attention on) particular words or the ideas associated with them. Doing this can change or clarify the meaning of a sentence; for example:

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (Somebody else did.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did not take it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did something else with it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took one of several. or I didn’t take the specific test that would have been implied.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took something else.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took it some other day.)

As in the examples above, stress is normally transcribed as italics in printed text or underlining in handwriting.

In English, stress is most dramatically realized on focused or accented words. For instance, consider the dialogue

«Is it brunch tomorrow?»

«No, it’s dinner tomorrow.»

In it, the stress-related acoustic differences between the syllables of «tomorrow» would be small compared to the differences between the syllables of «dinner«, the emphasized word. In these emphasized words, stressed syllables such as «din» in «dinner» are louder and longer.[11][12][13] They may also have a different fundamental frequency, or other properties.

The main stress within a sentence, often found on the last stressed word, is called the nuclear stress.[14]

Stress and vowel reduction[edit]

In many languages, such as Russian and English, vowel reduction may occur when a vowel changes from a stressed to an unstressed position. In English, unstressed vowels may reduce to schwa-like vowels, though the details vary with dialect (see stress and vowel reduction in English). The effect may be dependent on lexical stress (for example, the unstressed first syllable of the word photographer contains a schwa , whereas the stressed first syllable of photograph does not /ˈfoʊtəˌgræf -grɑːf/), or on prosodic stress (for example, the word of is pronounced with a schwa when it is unstressed within a sentence, but not when it is stressed).

Many other languages, such as Finnish and the mainstream dialects of Spanish, do not have unstressed vowel reduction; in these languages vowels in unstressed syllables have nearly the same quality as those in stressed syllables.

Stress and rhythm[edit]

Some languages, such as English, are said to be stress-timed languages; that is, stressed syllables appear at a roughly constant rate and non-stressed syllables are shortened to accommodate that, which contrasts with languages that have syllable timing (e.g. Spanish) or mora timing (e.g. Japanese), whose syllables or moras are spoken at a roughly constant rate regardless of stress. For details, see isochrony.

Historical effects[edit]

It is common for stressed and unstressed syllables to behave differently as a language evolves. For example, in the Romance languages, the original Latin short vowels /e/ and /o/ have often become diphthongs when stressed. Since stress takes part in verb conjugation, that has produced verbs with vowel alternation in the Romance languages. For example, the Spanish verb volver (to return, come back) has the form volví in the past tense but vuelvo in the present tense (see Spanish irregular verbs). Italian shows the same phenomenon but with /o/ alternating with /uo/ instead. That behavior is not confined to verbs; note for example Spanish viento «wind» from Latin ventum, or Italian fuoco «fire» from Latin focum. There are also examples in French, though they are less systematic : viens from Latin venio where the first syllabe was stressed, vs venir from Latin venire where the main stress was on the penultimate syllable.

Stress «deafness»[edit]

An operational definition of word stress may be provided by the stress «deafness» paradigm.[15][16] The idea is that if listeners perform poorly on reproducing the presentation order of series of stimuli that minimally differ in the position of phonetic prominence (e.g. [númi]/[numí]), the language does not have word stress. The task involves a reproduction of the order of stimuli as a sequence of key strokes, whereby key «1» is associated with one stress location (e.g. [númi]) and key «2» with the other (e.g. [numí]). A trial may be from 2 to 6 stimuli in length. Thus, the order [númi-númi-numí-númi] is to be reproduced as «1121». It was found that listeners whose native language was French performed significantly worse than Spanish listeners in reproducing the stress patterns by key strokes. The explanation is that Spanish has lexically contrastive stress, as evidenced by the minimal pairs like tópo («mole») and topó («[he/she/it] met»), while in French, stress does not convey lexical information and there is no equivalent of stress minimal pairs as in Spanish.

An important case of stress «deafness» relates to Persian.[16] The language has generally been described as having contrastive word stress or accent as evidenced by numerous stem and stem-clitic minimal pairs such as /mɒhi/ [mɒ.hí] («fish») and /mɒh-i/ [mɒ́.hi] («some month»). The authors argue that the reason that Persian listeners are stress «deaf» is that their accent locations arise postlexically. Persian thus lacks stress in the strict sense.

Stress «deafness» has been studied for a number of languages, such as Polish[17] or French learners of Spanish.[18]

Spelling and notation for stress[edit]

The orthographies of some languages include devices for indicating the position of lexical stress. Some examples are listed below:

- In Modern Greek, all polysyllables are written with an acute accent (´) over the vowel of the stressed syllable. (The acute accent is also used on some monosyllables in order to distinguish homographs, as in η (‘the’) and ή (‘or’); here the stress of the two words is the same.)

- In Spanish orthography, stress may be written explicitly with a single acute accent on a vowel. Stressed antepenultimate syllables are always written with that accent mark, as in árabe. If the last syllable is stressed, the accent mark is used if the word ends in the letters n, s, or a vowel, as in está. If the penultimate syllable is stressed, the accent is used if the word ends in any other letter, as in cárcel. That is, if a word is written without an accent mark, the stress is on the penult if the last letter is a vowel, n, or s, but on the final syllable if the word ends in any other letter. However, as in Greek, the acute accent is also used for some words to distinguish various syntactical uses (e.g. té ‘tea’ vs. te a form of the pronoun tú ‘you’; dónde ‘where’ as a pronoun or wh-complement, donde ‘where’ as an adverb). For more information, see Stress in Spanish.

- In Portuguese, stress is sometimes indicated explicitly with an acute accent (for i, u, and open a, e, o), or circumflex (for close a, e, o). The orthography has an extensive set of rules that describe the placement of diacritics, based on the position of the stressed syllable and the surrounding letters.

- In Italian, the grave accent is needed in words ending with an accented vowel, e.g. città, ‘city’, and in some monosyllabic words that might otherwise be confused with other words, like là (‘there’) and la (‘the’). It is optional for it to be written on any vowel if there is a possibility of misunderstanding, such as condomìni (‘condominiums’) and condòmini (‘joint owners’). See Italian alphabet § Diacritics. (In this particular case, a frequent one in which diacritics present themselves, the difference of accents is caused by the fall of the second «i» from Latin in Italian, typical of the genitive, in the first noun (con/domìnìi/, meaning «of the owner»); while the second was derived from the nominative (con/dòmini/, meaning simply «owners»).

Though not part of normal orthography, a number of devices exist that are used by linguists and others to indicate the position of stress (and syllabification in some cases) when it is desirable to do so. Some of these are listed here.

- Most commonly, the stress mark is placed before the beginning of the stressed syllable, where a syllable is definable. However, it is occasionally placed immediately before the vowel.[19] In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), primary stress is indicated by a high vertical line (primary stress mark:

ˈ) before the stressed element, secondary stress by a low vertical line (secondary stress mark:ˌ). For example, [sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən] or /sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən/. Extra stress can be indicated by doubling the symbol: ˈˈ◌. - Linguists frequently mark primary stress with an acute accent over the vowel, and secondary stress by a grave accent. Example: [sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən] or /sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən/. That has the advantage of not requiring a decision about syllable boundaries.

- In English dictionaries that show pronunciation by respelling, stress is typically marked with a prime mark placed after the stressed syllable: /si-lab′-ə-fi-kay′-shən/.

- In ad hoc pronunciation guides, stress is often indicated using a combination of bold text and capital letters. For example, si-lab-if-i-KAY-shun or si-LAB-if-i-KAY-shun

- In Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian dictionaries, stress is indicated with marks called znaki udareniya (знаки ударения, ‘stress marks’). Primary stress is indicated with an acute accent (´) on a syllable’s vowel (example: вимовля́ння).[20][21] Secondary stress may be unmarked or marked with a grave accent: о̀колозе́мный. If the acute accent sign is unavailable for technical reasons, stress can be marked by making the vowel capitalized or italic.[22] In general texts, stress marks are rare, typically used either when required for disambiguation of homographs (compare в больши́х количествах ‘in great quantities’, and в бо́льших количествах ‘in greater quantities’), or in rare words and names that are likely to be mispronounced. Materials for foreign learners may have stress marks throughout the text.[20]

- In Dutch, ad hoc indication of stress is usually marked by an acute accent on the vowel (or, in the case of a diphthong or double vowel, the first two vowels) of the stressed syllable. Compare achterúítgang (‘deterioration’) and áchteruitgang (‘rear exit’).

- In Biblical Hebrew, a complex system of cantillation marks is used to mark stress, as well as verse syntax and the melody according to which the verse is chanted in ceremonial Bible reading. In Modern Hebrew, there is no standardized way to mark the stress. Most often, the cantillation mark oleh (part of oleh ve-yored), which looks like a left-pointing arrow above the consonant of the stressed syllable, for example ב֫וקר bóqer (‘morning’) as opposed to בוק֫ר boqér (‘cowboy’). That mark is usually used in books by the Academy of the Hebrew Language and is available on the standard Hebrew keyboard at AltGr-6. In some books, other marks, such as meteg, are used.[23]

See also[edit]

- Accent (poetry)

- Accent (music)

- Foot (prosody)

- Initial-stress-derived noun

- Pitch accent (intonation)

- Rhythm

- Syllable weight

References[edit]

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1955). «Duration and intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stress». Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 27 (4): 765–768. Bibcode:1955ASAJ…27..765F. doi:10.1121/1.1908022.

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1958). «Experiments in the perception of stress». Language and Speech. 1 (2): 126–152. doi:10.1177/002383095800100207. S2CID 141158933.

- ^ a b Monrad-Krohn, G. H. (1947). «The prosodic quality of speech and its disorders (a brief survey from a neurologist’s point of view)». Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 22 (3–4): 255–269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1947.tb08246.x. S2CID 146712090.

- ^ Kochanski, Greg; Shih, Chilin; Jing, Hongyan (2003). «Quantitative measurement of prosodic strength in Mandarin». Speech Communication. 41 (4): 625–645. doi:10.1016/S0167-6393(03)00100-6.

- ^ Mirakyan, Norayr (2016). «The Implications of Prosodic Differences Between English and Armenian» (PDF). Collection of Scientific Articles of YSU SSS. YSU Press. 1.3 (13): 91–96.

- ^ San Duanmu (2000). The Phonology of Standard Chinese. Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- ^ mankind in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Publishers, HarperCollins. «The American Heritage Dictionary entry: mankind». www.ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ «paper bag» in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Ladefoged (1975 etc.) A course in phonetics § 5.4; (1980) Preliminaries to linguistic phonetics p 83

- ^ Beckman, Mary E. (1986). Stress and Non-Stress Accent. Dordrecht: Foris. ISBN 90-6765-243-1.

- ^ R. Silipo and S. Greenberg, Automatic Transcription of Prosodic Stress for Spontaneous English Discourse, Proceedings of the XIVth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS99), San Francisco, CA, August 1999, pages 2351–2354

- ^ Kochanski, G.; Grabe, E.; Coleman, J.; Rosner, B. (2005). «Loudness predicts prominence: Fundamental frequency lends little». The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 118 (2): 1038–1054. Bibcode:2005ASAJ..118.1038K. doi:10.1121/1.1923349. PMID 16158659. S2CID 405045.

- ^ Roca, Iggy (1992). Thematic Structure: Its Role in Grammar. Walter de Gruyter. p. 80.

- ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Peperkamp, Sharon; Sebastián-Gallés, Núria (2001). «A robust method to study stress «deafness»«. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 110 (3): 1606–1618. Bibcode:2001ASAJ..110.1606D. doi:10.1121/1.1380437. PMID 11572370.

- ^ a b Rahmani, Hamed; Rietveld, Toni; Gussenhoven, Carlos (2015-12-07). «Stress «Deafness» Reveals Absence of Lexical Marking of Stress or Tone in the Adult Grammar». PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143968. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043968R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143968. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4671725. PMID 26642328.

- ^ 3:439, 2012, 1-15., Ulrike; Knaus, Johannes; Orzechowska, Paula; Wiese, Richard (2012). «Stress ‘deafness’ in a language with fixed word stress: an ERP study on Polish». Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 439. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00439. PMC 3485581. PMID 23125839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Sebastián-Gallés, N; Navarrete, E; Peperkamp, Sharon (2008). «Persistent stress ‘deafness’: The case of French learners of Spanish». Cognition. 106 (2): 682–706. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.001. hdl:11577/2714082. PMID 17592731. S2CID 2632741.

- ^ Payne, Elinor M. (2005). «Phonetic variation in Italian consonant gemination». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002240. S2CID 144935892.

- ^ a b Лопатин, Владимир Владимирович, ed. (2009). § 116. Знак ударения. Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник (in Russian). Эксмо. ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5.

- ^ Some pre-revolutionary dictionaries, e.g. Dahl’s Explanatory Dictionary, marked stress with an apostrophe just after the vowel (example: гла’сная). See: Dahl, Vladimir Ivanovich (1903). Boduen de Kurtene, Ivan Aleksandrovich (ed.). Толко́вый слова́рь живо́го великору́сского языка́ [Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). Saint Petersburg: M.O. Wolf. p. 4.

- ^ Каплунов, Денис (2015). Бизнес-копирайтинг: Как писать серьезные тексты для серьезных людей (in Russian). p. 389. ISBN 978-5-000-57471-3.

- ^ Aharoni, Amir (2020-12-02). «אז איך נציין את מקום הטעם». הזירה הלשונית – רוביק רוזנטל. Retrieved 2021-11-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links[edit]

- «Feet and Metrical Stress», The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

- «Word stress in English: Six Basic Rules», Linguapress

- Word Stress Rules: A Guide to Word and Sentence Stress Rules for English Learners and Teachers, based on affixation

Selye’s discovery

Selye’s discovery