A state is a political association with effective sovereignty over a geographic area and representing a population. These may be nation states, sub-national states or multinational states. A state usually includes the set of institutions that claim the authority to make the rules that govern the exercise of coercive violence for the people of the society in that territory, though its status as a state often depends in part on being recognized by a number of other states as having internal and external sovereignty over it. In sociology, the state is normally identified with these institutions: in Max Weber’s influential definition, it is that organization that «(successfully) claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory,» which may include the armed forces, civil service or state bureaucracy, courts, and police. Recently much debate has surrounded the issue of State-building with competing schools of thought on how to support the emergence of capable states.

Definition

Although the term often includes broadly all institutions of government or rule—ancient and modern—the modern state system bears a number of characteristics that were first consolidated beginning in earnest in the 15th century, when the term «state» also acquired its current meaning. Thus the word is often used in a strict sense to refer only to modern political systems.

Within a federal system, the term state also refers to political units, not completely sovereign themselves; however, these systems are subject to the authority of a constitution defining a federal union which is partially or co-sovereign with them.

In casual usage, the terms «country,» «nation,» and «state» are often used as if they were synonymous; but in a more strict usage they can be distinguished:

* «Country» denotes a geographical area.

* «Nation» denotes a people who are believed to or deemed to share common customs, origins, and history. However, the adjectives «national» and «international» also refer to matters pertaining to what are strictly «states», as in «national capital», «international law».

* «State» refers to the set of governing and supportive institutions that have sovereignty over a definite territory and population.

Etymology

The word «state» and its cognates in other European languages («stato» in Italian, «état» in French, «Staat» in German and «estado» in Spanish and Portuguese) ultimately derive from the Latin STATVS, meaning «condition» or «status». [«state.» Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 26 February 2007. [Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/state] .] With the revival of the Roman law in the 14th century in Europe, this Latin term was used to refer to the legal standing of persons (such as the various «estates of the realm» — noble, common, and clerical), and in particular the special status of the king. The word was also associated with Roman ideas (dating back to Cicero) about the «status rei publicae», the «condition of the republic.» In time, the word lost its reference to particular social groups and became associated with the legal order of the entire society and the apparatus of its enforcement.Skinner, Quentin. 1989. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521359783&id=1QrSKH_Q5M8C&pg=RA1-PA6&lpg=RA1-PA6&ots=Nn0ouzVO1R&dq=Skinner+Political+Innovation+Conceptual+Change&sig=660qldsyiEPiohCBXir3QqAwCWE#PRA1-PA90,M1 The State] . In Political Innovation and Conceptual Change, edited by T. Ball, J. Farr and R. L. Hanson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521359783&id=1QrSKH_Q5M8C&pg=RA1-PA6&lpg=RA1-PA6&ots=Nn0ouzVO1R&dq=Skinner+Political+Innovation+Conceptual+Change&sig=660qldsyiEPiohCBXir3QqAwCWE#PRA1-PA90,M1 ISBN 0521359783] ]

In other languages meaning can be different. Polish ‘państwo’ can be derived from the word ‘pan’=lord, the one who has power (‘Lord Jesus’=’Pan Jezus’). ‘Państwo’ therefore denotes a state, when someone is governing (is in charge). The word ‘państwo’ also suggest some kind of social organisation, as its second meaning in Polish relates to «family» (państwo Smith = the Smiths).

It has also been claimed that the word «state» originates from the medieval «state» or regal chair upon which the head of state (usually a monarch) would sit. By process of metonymy, the word state became used to refer to both the head of state and the power entity he represented (though the former meaning has fallen out of use).Fact|date=February 2007 Two quotations which reference these different meanings, both commonly, though probably apocryphally, attributed to King Louis XIV of France, are «L’État, c’est moi» («I am the State») and «Je m’en vais, mais l’État demeurera toujours.» («I am going away, but the State will always remain»). A similar association of terms can today be seen in the practice of referring to government buildings as having authority, for example «The White House today released a press statement…».

Empirical and juridical senses of the word state

The word «state» has both an empirical and a juridical sense, i.e., entities can be states either «de facto» or «de jure» or both.Jackson, Robert H., and Carl G. Rosberg. 1982. [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-8871%28198210%2935%3A1%3C1%3AWAWSPT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K Why Africa’s Weak States Persist: The Empirical and The Juridical in Statehood] . World Politics 35 (1):1-24. [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-8871%28198210%2935%3A1%3C1%3AWAWSPT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-K] ]

Empirically (or de facto), an entity is a state if, as in Max Weber’s influential definition, it is that organization that has a ‘monopoly on legitimate violence’ over a specific territory.Weber, Max. 1994. The Profession and Vocation of Politics. In [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521397197&id=6uA68XdxBv4C&pg=PA394&lpg=PA394 Political Writings] . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521397197&id=6uA68XdxBv4C&pg=PA394&lpg=PA394 ISBN 0521397197] .] Such an entity imposes its own legal order over a territory, even if it is not legally recognized as a state by other states (e.g., the Somali region of Somaliland).

Juridically (or de jure), an entity is a state in international law if it is recognized as such by other states, even if it does not actually have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force over a territory. Only an entity juridically recognized as a state can enter into many kinds of international agreements and be represented in a variety of legal forums, such as the United Nations.

States, government types, and political systems

The concept of the state can be distinguished from two related concepts with which it is sometimes confused: the concept of a form of government or regime, such as democracy or dictatorship, and the concept of a political system. The form of government identifies only one aspect of the state, namely, the way in which the highest political offices are filled and their relationship to each other and to society. It does not include other aspects of the state that may be very important in its everyday functioning, such as the quality of its bureaucracy. For example, two democratic states may be quite different if one has a capable, well-trained bureaucracy or civil service while the other does not. Thus generally speaking the term «state» refers to the instruments of political power, while the terms regime or form of government refers more to the way in which such instruments can be accessed and employed.Bobbio, Norberto. 1989. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0816618135&id=4AE8ur83g8AC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=8883y8Du41&dq=Bobbio+Democracy+and+Dictatorship&sig=kfL3Vpo83GuEdGmhXJMmTIbBNnw Democracy and Dictatorship: The Nature and Limits of State Power] . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0816618135&id=4AE8ur83g8AC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=8883y8Du41&dq=Bobbio+Democracy+and+Dictatorship&sig=kfL3Vpo83GuEdGmhXJMmTIbBNnw ISBN 0816618135] .]

Some scholars have suggested that the term «state» is too imprecise and loaded to be used productively in sociology and political science, and ought to be replaced by the more comprehensive term «political system.» The «political system» refers to the ensemble of all social structures that function to produce collectively binding decisions in a society. In modern times, these would include the political regime, political parties, and various sorts of organizations. The term «political system» thus denotes a broader concept than the state.Easton, David. 1990. The Analysis of Political Structure. New York: Routledge.]

The historical development of the state

The earliest forms of the state emerged whenever it became possible to centralize power in a durable way. Agriculture and writing are almost everywhere associated with this process. Agriculture allowed for the production and storing of a surplus. This in turn allowed and encouraged the emergence of a class of people who controlled and protected the agricultural stores and thus did not have to spend most of their time providing for their own subsistence. In addition, writing (or the equivalent of writing, like Inca quipus) because it made possible the centralization of vital information.Giddens, Anthony. 1987. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0520060393&id=wJu1Z4cTdsIC&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=Giddens+Contemporary+Critique+of+Historical+Materialism+the+Nation+State+and+Violence&sig=OwPRjSxlp6Hng4YHp74wHYWSaGQ#PPP1,M1A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism. 3 vols. Vol. II: The Nation-State and Violence] . Cambridge: Polity Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0520060393&id=wJu1Z4cTdsIC&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=Giddens+Contemporary+Critique+of+Historical+Materialism+the+Nation+State+and+Violence&sig=OwPRjSxlp6Hng4YHp74wHYWSaGQ#PPP1,M1 ISBN 0520060393] . See [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0520060393&id=wJu1Z4cTdsIC&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=Giddens+Contemporary+Critique+of+Historical+Materialism+the+Nation+State+and+Violence&sig=OwPRjSxlp6Hng4YHp74wHYWSaGQ#PPP7,M1 chapter 2] .]

Some political philosophers believe the origins of the state lie ultimately in the tribal culture which developed with human sentience, the template for which was the alleged primal «alpha-male» microsocieties of our earlier ancestors, which were based on the coercion of the weak by the strong. Fact|date=July 2007 However anthropologists point out that extant band- and tribe-level societies are notable for their «lack» of centralized authority, and that highly stratified societies—i.e., states—constitute a relatively recent break with the course of human history. [Boehm, Christopher. 1999. [http://www.google.co.nz/books?id=ljxS8gUlgqgC|Hierarchy in the Forest] . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [http://www.google.co.nz/books?id=ljxS8gUlgqgC|ISBN 0674006917] .]

The state in classical antiquity

The history of the state in the West usually begins with classical antiquity. During that period, the state took a variety of forms, none of them very much like the modern state. There were monarchies whose power (like that of the Egyptian Pharaoh) was based on the religious function of the king and his control of a centralized army. There were also large, quasi-bureaucratized empires, like the Roman empire, which depended less on the religious function of the ruler and more on effective military and legal organizations and the cohesion of an aristocracy.

Perhaps the most important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population, and in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.

In contrast, Rome developed from a monarchy into a republic, governed by a senate dominated by the Roman aristocracy. The Roman political system contributed to the development of law, constitutionalism and to the distinction between the private and the public spheres.

From the feudal state to the modern state in the West

The story of the development of the specifically modern state in the West typically begins with the dissolution of the western Roman empire. This led to the fragmentation of the imperial state into the hands of private and decentralized lords whose political, judicial, and military roles corresponded to the organization of economic production. In these conditions, according to Marxists, the economic unit of society corresponded exactly to the state on the local level.

The state-system of feudal Europe was an unstable configuration of suzerains and anointed kings. A monarch, formally at the head of a hierarchy of sovereigns, was not an absolute power who could rule at will; instead, relations between lords and monarchs were mediated by varying degrees of mutual dependence, which was ensured by the absence of a centralized system of taxation. This reality ensured that each ruler needed to obtain the ‘consent’ of each estate in the realm. This was not quite a ‘state’ in the Weberian sense of the term, since the king did not monopolize either the power of lawmaking (which was shared with the church) or the means of violence (which were shared with the nobles).

The formalization of the struggles over taxation between the monarch and other elements of society (especially the nobility and the cities) gave rise to what is now called the Standestaat, or the state of Estates, characterized by parliaments in which key social groups negotiated with the king about legal and economic matters. These estates of the realm sometimes evolved in the direction of fully-fledged parliaments, but sometimes lost out in their struggles with the monarch, leading to greater centralization of lawmaking and coercive (chiefly military) power in his hands. Beginning in the 15th century, this centralizing process gave rise to the absolutist state.Poggi, G. 1978. The Development of the Modern State: A Sociological Introduction. Stanford: Stanford University Press.]

The modern state

The rise of the «modern state» as a public power constituting the supreme political authority within a defined territory is associated with western Europe’s gradual institutional development beginning in earnest in the late 15th century, culminating in the rise of absolutism and capitalism.

As Europe’s dynastic states — England under the Tudors, Spain under the Habsburgs, and France under the Bourbons — embarked on a variety of programs designed to increase centralized political and economic control, they increasingly exhibited many of the institutional features that characterize the «modern state.» This centralization of power involved the delineation of political boundaries, as European monarchs gradually defeated or co-opted other sources of power, such as the Church and lesser nobility. In place of the fragmented system of feudal rule, with its often indistinct territorial claims, large, unitary states with extensive control over definite territories emerged. This process gave rise to the highly centralized and increasingly bureaucratic forms of absolute monarchical rule of the 17th and 18th centuries, when the principal features of the contemporary state system took form, including the introduction of a standing army, a central taxation system, diplomatic relations with permanent embassies, and the development of state economic policy—mercantilism.

Cultural and national homogenization figured prominently in the rise of the modern state system. Since the absolutist period, states have largely been organized on a national basis. The concept of a national state, however, is not synonymous with nation-state. Even in the most ethnically homogeneous societies there is not always a complete correspondence between state and nation, hence the active role often taken by the state to promote nationalism through emphasis on shared symbols and national identity.Breuilly, John. 1993. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0719038006&id=6sEVmFtkpngC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=jaRrjiINsh&dq=Breuilly+Nationalism+and+the+State&sig=xdUZ4zKU-os0Mx75Wk9gO3LuYhU Nationalism and the State] . New York: St. Martin’s Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0719038006&id=6sEVmFtkpngC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=jaRrjiINsh&dq=Breuilly+Nationalism+and+the+State&sig=xdUZ4zKU-os0Mx75Wk9gO3LuYhU ISBN SBN0719038006] .]

It is in this period that the term «the state» is first introduced into political discourse in more or less its current meaning. Although Niccolò Machiavelli is often credited with first using the term to refer to a territorial sovereign government in the modern sense in «The Prince», published in 1532, it is not until the time of the British thinkers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and the French thinker Jean Bodin that the concept in its current meaning is fully developed.

Today, most Western states more or less fit the influential definition of the state in Max Weber’s «Politics as a Vocation». According to Weber, the modern state monopolizes the means of legitimate physical violence over a well-defined territory. Moreover, the legitimacy of this monopoly itself is of a very special kind, «rational-legal» legitimacy, based on impersonal rules that constrain the power of state elites.

However, in some other parts of the world states do not fit Weber’s definition as well. They may not have a complete monopoly over the means of legitimate physical violence over a definite territory, or their legitimacy may not be adequately described as rational-legal. But they are still recognizably distinct from feudal and absolutist states in the extent of their bureaucratization and their reliance on nationalism as a principle of legitimation.

Since Weber, an extensive literature on the processes by which the «modern state» emerged from the feudal state has been generated. Marxist scholars, for example, assert that the formation of modern states can be explained primarily in terms of the interests and struggles of social classes.Anderson, Perry. 1979. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN086091710X&id=EhtMbM1Z8BkC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=kKEFE8hSdz&dq=Perry+Anderson+Lineages+of+the+Absolutist+State&sig=6wtAz_EZf89y2x2Y6bZB3Rgkh6Y Lineages of the absolutist state] . London: Verso. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN086091710X&id=EhtMbM1Z8BkC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=kKEFE8hSdz&dq=Perry+Anderson+Lineages+of+the+Absolutist+State&sig=6wtAz_EZf89y2x2Y6bZB3Rgkh6Y ISBN 086091710X] .]

Scholars working in the broad Weberian tradition, by contrast, have often emphasized the institution-building effects of war. For example, Charles Tilly has argued that the revenue-gathering imperatives forced on nascent states by geopolitical competition and constant warfare were mostly responsible for the development of the centralized, territorial bureaucracies that characterize modern states in Europe. States that were able to develop centralized tax-gathering bureaucracies and to field mass armies survived into the modern era; states that were not able to do so did not.Tilly, Charles. 1992. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN1557863687&id=w4zjW_RjNb0C&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&ots=uKjqZcZf6T&dq=Coercion,+Capital,+and+European+States&sig=UjCM07nwXyw8otUoSLTmdiKYUs4 Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1992] . Cambridge, Massachusetts: B. Blackwell. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN1557863687&id=w4zjW_RjNb0C&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&ots=uKjqZcZf6T&dq=Coercion,+Capital,+and+European+States&sig=UjCM07nwXyw8otUoSLTmdiKYUs4 ISBN 1557863687] .]

State and civil society

The modern state is both separate from and connected to civil society. The nature of this connection has been the subject of considerable attention in both analyses of state development and normative theories of the state. Earlier thinkers, such as Thomas Hobbes emphasized the supremacy of the state over society. Later thinkers, by contrast, beginning with G. W. F. Hegel, have tended to emphasize the points of contact between them. Jürgen Habermas, for example, has argued that civil society forms a public sphere, that is, a site of extra-institutional engagement with matters of public interest autonomous from the state and yet necessarily connected with it.

Some Marxist theorists, such as Antonio Gramsci, have questioned the distinction between the state and civil society altogether, arguing that the former is integrated into many parts of the latter. Others, such as Louis Althusser, maintain that civil organizations such as churches, schools, and even trade unions are part of an ‘ideological state apparatus.’ In this sense, the state can fund a number of groups within society that, while autonomous in principle, are dependent on state support.

Given the role that many social groups have in the development of public policy and the extensive connections between state bureaucracies and other institutions, it has become increasingly difficult to identify the boundaries of the state. Privatization, nationalization, and the creation of new regulatory bodies also change the boundaries of the state in relation to society. Often the nature of quasi-autonomous organizations is unclear, generating debate among political scientists on whether they are part of the state or civil society. Some political scientists thus prefer to speak of policy networks and decentralized governance in modern societies rather than of state bureaucracies and direct state control over policy. [Kjaer, Anne Mette. 2004. [http://www.amazon.com/dp/0745629792 Governance] . London: Verso. [http://www.amazon.com/dp/0745629792 ISBN 0745629792] ] Alfred Stepan also introduced the idea of `political society’ those organisations that move periodically between the state and non-state sectors (such as Political Parties). Whaites has argued that in developing countries there are dangers inherent in promoting strong civil society where states are weak, risks that should be considered and mitigated by those funding civil society or advocating its role as an alternative source of service provision [Alan Whaites. 1998. Viewpoint NGOs, civil society and the state: avoiding theoretical extremes in real world issues [http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a713661019~db=all~order=page Development in Practice] ] .

The state and the international system

Since the late 19th century the entirety of the world’s inhabitable land has been parceled up into states with more or less definite borders claimed by various states. Earlier, quite large land areas had been either unclaimed or uninhabited, or inhabited by nomadic peoples who were not organized as states. Currently more than 200 states comprise the international community, with the vast majority of them represented in the United Nations.

These states form what International relations theorists call a system, where each state takes into account the behavior of other states when making their own calculations. From this point of view, states embedded in an international system face internal and external security and legitimation dilemmas. Recently the notion of an «international community» has been developed to refer to a group of states who have established , procedures, and institutions for the conduct of their relations. In this way the foundation has been laid for international law, diplomacy, formal regimes, and organizations.

The state and supranationalism

In the late 20th century, the globalization of the world economy, the mobility of people and capital, and the rise of many international institutions all combined to circumscribe the freedom of action of states. These constraints on the state’s freedom of action are accompanied in some areas, notably Western Europe, with projects for interstate integration such as the European Union. However, the state remains the basic political unit of the world, as it has been since the 16th century. The state is therefore considered the most central concept in the study of politics, and its definition is the subject of intense scholarly debate.

The state and international law

By modern practice and the law of international relations, a state’s sovereignty is conditional upon the diplomatic recognition of the state’s claim to statehood. Degrees of recognition and sovereignty may vary. However, any degree of recognition, even recognition by a majority of the states in the international system, is not binding on third-party states.

The legal criteria for statehood are not obvious. Often, the laws are surpassed by political circumstances. However, one of the documents often quoted on the matter is the Montevideo Convention from 1933, the first article of which states:

:The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

Contemporary approaches to the study of the state

There are three main traditions within political science and sociology that shape ‘theories of the state’: the pluralist, the Marxist, and the institutionalist. In addition, anarchists present a tradition which is similar to, but different from, the Marxian one.

Each of these theories has been employed to gain understanding on the state, while recognizing its complexity. Several issues underlie this complexity. First, the boundaries of the state sector are not clearly defined, while they change constantly. Second, the state is not only the site of conflict between different organizations, but also internal conflict and conflict within organizations. Some scholars speak of the ‘state’s interest,’ but there are often various interests within different parts of the state that are neither solely state-centered nor solely society-centered, but develop between different groups in civil society and different state actors.

Pluralism

Pluralism has been very popular in the United States. In fact, it might be seen as the dominant vision of politics in that country.

Within this tradition, Robert Dahl sees the state as either (1) a neutral arena for settling disputes among contending interests or (2) a collection of agencies which themselves act as simply another set of interest groups. With power diffused across society among many competing groups, state policy is a product of recurrent bargaining. Although pluralism recognizes the existence of inequality, it asserts that all groups have an opportunity to pressure the state. The pluralist approach suggests that the modern democratic state’s actions are the result of pressures applied by a variety of organized interests. Dahl called this kind of state a polyarchy. [Robert Dahl. 1973. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0135969816&id=9XY5gFcp6n0C&q=Dahl+Modern+Political+Analysis&dq=Dahl+Modern+Political+Analysis&pgis=1 Modern Political Analysis] . Prentice Hall. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0135969816&id=9XY5gFcp6n0C&q=Dahl+Modern+Political+Analysis&dq=Dahl+Modern+Political+Analysis&pgis=1 ISBN 0135969816] ]

In some ways, the development of the pluralist school is a response to the «power elite» theory presented in 1956 by the sociologist C. Wright Mills concerning the U.S. and furthered by research by G. William Domhoff, among others. In that theory, the most powerful elements of the political, military, and economic parts of U.S. society are united at the top of the political system, acting to serve their common interests. The «masses» were left out of the political process. In context, it might said that Mills saw the U.S. elite as in part being very similar to that of the Soviet Union, then the major geopolitical rival of the U.S. One response was the sociologist Arnold M. Rose’s publication of «The Power Structure: Political Process in American Society» in 1967. He argued that the distribution of power in the U.S. was more diffuse and pluralistic in nature.

The importance of democratic elections of political leaders in the U.S. (and not the Soviet Union) provides evidence in favor of the pluralist perspective for that country. We might reconcile power elite theory with pluralism in terms of Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of democracy. To him, «democracy» involved the (non-elite) masses choosing «which» elite would have the power.

The absence of democratic elections do not rule out pluralism, however. The old Soviet Union is sometimes described as being ruled by an elite, which ran society via a bureaucracy which united the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the military, and Gosplan, the economic planning apparatus. However, bureaucratic rule from above is never perfect. This meant that, so to some extent, Soviet policies reflected a pluralistic competition of interest groups within the Party, the military, and Gosplan, including factory managers.

Marxism

Marxist theories of the state were relatively influential in continental Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. But it is hard to summarize the theory developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. After all, the effort by Hal Draper to distill their political thinking in his «Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution» (Monthly Review Press) took several thick volumes. But many have tried.

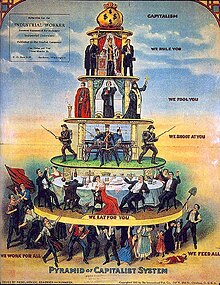

For Marxist theorists, the role of modern states is determined or related to their role in capitalist societies. They would agree with Weber on the crucial role of coercion in defining the state. (In fact, Weber himself starts his analysis with a quotation from Leon Trotsky, a Bolshevik leader.) But Marxists reject the mainstream liberal view that the state is an institution established in the collective interest of society as a whole (perhaps by a social contract) to reconcile competing interests in the name of the common good. Contrary to the pluralist vision, the state is not a mere «neutral arena for settling disputes among contending interests» because it leans heavily to support one interest group (the capitalists) alone. Nor does the state usually act as merely a «collection of agencies which themselves act as simply another set of interest groups,» again because of the state’s systematic bias toward serving capitalist interests.

In contrast to liberal or pluralist views, the American economist Paul Sweezy and other Marxian thinkers have pointed out that the main job of the state is to protect capitalist property rights in the means of production. At first, this seems hardly controversial. After all, many economics and politics textbooks refer to the state’s crucial role in defending property rights and in enforcing contracts. But the capitalists own a share of the means of production that is far out of proportion to the capitalists’ role in the total population. More importantly, in Marxian theory, ownership of the means of production gives that minority social power over those who do not own the means of production (the workers). Because of that power, i.e., the power to exploit and dominate the working class, the state’s defense of them is nothing but the use of coercion to defend capitalism as a class society. [Sweezy, Paul. 1942. The Theory of Capitalist Development. New York: Monthly Review, ch. 13.] Instead of serving the interests of society as a whole, in this view the state serves those of a small minority of the population.

Among Marxists, as with other topics, there are many debates about the nature and role of the capitalist state. One division is between the «instrumentalists» and the «structuralists.»

On the first, some contemporary Marxists apply a literal interpretation of the comment by Marx and Frederich Engels in «The Communist Manifesto» that «The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.» In this tradition, Ralph Miliband argued that the ruling class uses the state as its «instrument» (tool) to dominate society in a straightforward way. For Miliband, the state is dominated by an elite that comes from the same background as the capitalist class and therefore shares many of the same goals. State officials therefore share the same interests as owners of capital and are linked to them through a wide array of interpersonal and political ties. [Miliband, Ralph. 1983. Class power and state power. London: Verso.] In many ways, this theory is similar to the «power elite» theory of C. Wright Mills.

Miliband’s research is specific to the United Kingdom, where the class system has traditionally been integrated strongly into the educational system (Eton, Oxbridge, etc.) and social networks. In the United States, the educational system and social networks are more heterogeneous and seem less class-dominated to many. But a social connection between state managers and the capitalist class can be seen in the dependence of the major politicians and their parties on campaign contributions from the rich, on approval from the capitalist-owned media, on advice from corporate-endowed «think tanks,» and the like.

In the second view, other Marxist theorists argue that the exact names, biographies, and social roles of those who control the state are irrelevant. Instead, they emphasize the «structural» role of the state’s activities. Heavily influenced by the French philosopher Louis Althusser, Nicos Poulantzas, a Greek neo-Marxist theorist argued that capitalist states do not always act on behalf of the ruling class, and when they do, it is not necessarily the case because state officials consciously strive to do so, but because the structural position of the state is configured in such a way to ensure that the interests of capital are always dominant.

Poulantzas’ main contribution to the Marxian literature on the state was the concept of «relative autonomy» of the state: state policies do not correspond exactly to the collective or long-term interests of the capitalist class, but help maintain and preserve capitalism over the long haul. The «power elite,» if one exists, may act in ways that go against the wishes of capitalists. While Poulantzas’ work on ‘state autonomy’ has served to sharpen and specify a great deal of Marxist literature on the state, his own framework came under criticism for its «structural functionalism.»

But this kind of criticism can be answered by considering what happens if state managers «do not» work to favor the operations of capitalism as a class society. [ Fred Block. 1977 «The Ruling Class Does Not Rule.» «Socialist Revolution» May-June.] They find that the economy are punished by a capital strike or capital flight, encouraging higher unemployment, a decline in tax receipts, and international financial problems. The decline in tax revenues makes it more necessary to borrow from the bourgeoisie. Because the latter will charge high interest rates (especially to a government seen as hostile), the state’s financial problems deepen. Such events might be seen in Chile in 1973, under Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular government. Added to the relatively «automatic» workings of the economy (under the spur of profit-seeking businesses) are the ways in which an anti-capitalist government provokes anti-government conspiracies, including those by the Central Intelligence Agency and local political forces, as actually happened in 1973.

Unless they are ready to actually mobilize the working population to revolutionize society and move beyond capitalism, «sober» state managers will pull back from anti-capitalist policies. In any event, they would likely never go so far as to «rock the boat» because of their acceptance of the dominant ideology encouraged by the prevailing educational system.

Despite the debates among Marxist theorists of the state, there are also many agreements. It is possible that both «instrumental» and «structural» forces encourage political unity of the state managers with the capitalist class. That is, both the personal influence of capitalists and the societal constraints on state activity play a role.

Of course, no matter how strong this link, the Marx-Engels dictum that «The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie» does not say that the executive will always do a «good job» in such management. (As Poulantzas pointed out, the state maintains some autonomy.) First, there is the problem of reconciling the particular interests of individual capitalist organizations with each other. For example, different parts of the media may disagree on the nature of needed government regulations. Further, it is often unclear what the long-run class interests of capitalists are, beyond the simple defense of capitalist property rights. It may be impossible to discover class interests until after the fact, i.e., after a policy has been implemented. Third, state managers may use their administrative power to serve their own interests and even to facilitate their entrance into the capitalist class.

Finally, pressure from working-class organizations (labor unions, social-democratic parties, etc.) or other non-capitalist forces (environmentalists, etc.) may push the state from toeing the capitalist «line» exactly. In the end, these problems imply that the state will always have some autonomy from obeying the exact wishes of the capitalist class.

In this view, the Marxian theory of the state does not really contradict the pluralist vision of the state as an arena for the contention of many interest groups, including those based in the state itself. Rather, the Marxian proposition is that this multi-sided competition and its results are strongly «biased» in the direction of reproducing the capitalist system over time.

It should be emphasized that all of the Marxist theories of the state discussed above refer only to the «capitalist» state in «normal» times (without civil war and the like). During a period of economic and social crisis, the absolute need to maintain order may raise the power of the military — and military goals — in governmental affairs, sometimes even leading to the violation of capitalist property rights.

In a non-capitalist system such as feudalism, Marxian historians have said that the state did not really exist in the sense that it does today (using Weber’s definition). That is, the central state did not monopolize force in a specific geographic area. The feudal king typically had to depend on the military power of his «lieges.» This meant that the country was more of an alliance than a unified whole. Further, the difference between the state and civil society was weak: the feudal lords were not simply involved in «economic» activity (production, sale, etc.) but also «political» activity: they used force against their serfs (to extract rents), while acting as judge, jury, and police.

Getting further beyond capitalism, Marxist theory says that since the state is central to protecting class inequality, it will «wither away» once class inequality of power is abolished. In practice, no self-styled Marxist leader or government has ever made attempts to move toward a society without a state. Of course, that is to be expected. After all, no society has ever completely abolished classes. In addition, no self-described «socialist» country has been able to do without a military defense against capitalist invasion or destabilization. Third, in Marxian theory, impetus for the abolition of the state would not come from the leaders or the government themselves as much as from the working people that they are supposed to represent.

Anarchism

The anarchists share many of the Marxian propositions about the state. But in contrast, anarchists argue that a country’s collective interests can be served without having a centralized organization. The maintenance of law and order does not require that there be a sector of society that monopolizes the legitimate use of force. It is possible for society to prosper without a state, even without a long period of classes «withering away.» In fact, anarchists see the state as a parasite that can and should be abolished.

Thus, they oppose the state as a matter of principle and reject the Marxian view that it may be needed temporarily as part of a transition to socialism or communism. They propose different strategies for the elimination of the state. There is a dichotomy of views regarding its replacement. Anarcho-capitalists envision a free market guided by the invisible hand offering critical or valuable functions traditionally provided by to replace the state; other anarchists (such as Bakunin and Kropotkin in the 19th century) tend to put less emphasis on markets, arguing for a form of socialism without the state. Such socialism would require worker self-management of the means of production and the federation of worker organizations in communes which will then federate into larger units.

Anarchists consider the state to be the institutionalization of domination and privilege. According to key theoristsFact|date=November 2007, the state emerged to ratify and deepen the dominance of the victors of history. Unlike Marxists, anarchists believe that the state, while reflecting social interests, is not a mere executive committee of the ruling class. In itself, without class rule, it is a position of power over the whole society that can dominate and exploit society. Naturally enough, many fractions of the ruling classes and even the oppressed classes strive to control the state, forming different and ever-changing alliances.Fact|date=November 2007 They also reject the need for a state to serve the collective needs of the people. Hence, they reject not only the current state, but the Marxian idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat). Instead, they see the state as an inherently oppressive force which takes away the ability of people to make decisions about the things that affect their lives.

Institutionalism

Both the Marxist and pluralist approaches view the state as reacting to the activities of groups within society, such as classes or interest groups. In this sense, they have both come under criticism for their ‘society-centered’ understanding of the state by scholars who emphasize the autonomy of the state with respect to social forces.

In particular, the «new institutionalism,» an approach to politics that holds that behavior is fundamentally molded by the institutions in which it is embedded, asserts that the state is not an ‘instrument’ or an ‘arena’ and does not ‘function’ in the interests of a single class. Scholars working within this approach stress the importance of interposing civil society between the economy and the state to explain variation in state forms.

«New institutionalist» writings on the state, such as the works of Theda Skocpol, suggest that state actors are to an important degree autonomous. In other words, state personnel have interests of their own, which they can and do pursue independently (at times in conflict with) actors in society. Since the state controls the means of coercion, and given the dependence of many groups in civil society on the state for achieving any goals they may espouse, state personnel can to some extent impose their own preferences on civil society. [Rueschemeyer, Dietrich, Theda Skocpol, and Peter B. Evans, eds. 1985. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521313139&id=sYgTwHQbNAAC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=Jyo8optLgc&dq=Skocpol+Rueschemeyer+Bringing+the+State+Back+In&sig=1m3dvluBo9jULIAoYBzEdhVnIeU Bringing the State Back In] . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521313139&id=sYgTwHQbNAAC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&ots=Jyo8optLgc&dq=Skocpol+Rueschemeyer+Bringing+the+State+Back+In&sig=1m3dvluBo9jULIAoYBzEdhVnIeU ISBN 0521313139] .]

‘New institutionalist’ writers, claiming allegiance to Weber, often utilize the distinction between ‘strong states’ and ‘weak states,’ claiming that the degree of ‘relative autonomy’ of the state from pressures in society determines the power of the state—a position that has found favor in the field of international political economy.

The state in modern political thought

The rise of the modern state system was closely related to changes in political thought, especially concerning the changing understanding of legitimate state power. Early modern defenders of absolutism such as Thomas Hobbes and Jean Bodin undermined the doctrine of the divine right of kings by arguing that the power of kings should be justified by reference to the people. Hobbes in particular went further and argued that political power should be justified with reference to the individual, not just to the people understood collectively. Both Hobbes and Bodin thought they were defending the power of kings, not advocating democracy, but their arguments about the nature of sovereignty were fiercely resisted by more traditional defenders of the power of kings, like Sir Robert Filmer in England, who thought that such defenses ultimately opened the way to more democratic claims.

These and other early thinkers introduced two important concepts in order to justify sovereign power: the idea of a state of nature and the idea of a social contract. The first concept describes an imagined situation in which the state — understood as a centralized, coercive power — does not exist, and human beings have all their natural rights and powers; the second describes the conditions under which a voluntary agreement could take human beings out of the state of nature and into a state of civil society. Depending on what they understood human nature to be and the natural rights they thought human beings had in that state, various writers were able to justify more or less extensive forms of the state as a remedy for the problems of the state of nature. Thus, for example, Hobbes, who described the state of nature as a «war of every man, against every man,» [Hobbes, Thomas. 1651. [http://oll.libertyfund.org/Texts/Hobbes0123/Leviathan1909/HTMLs/0161_Pt02_Part1.html#LF-BK0161pt01ch13 Leviathan] . Part I, chapter 13.] argued that sovereign power should be almost absolute since almost all sovereign power would be better than such a war, whereas John Locke, who understood the state of nature in more positive terms, thought that state power should be strictly limited. [Locke, John. 1689. [http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/HTML.php?recordID=0364#hd_lf128-04_head_025 Two Treatises of Government] . Second Treatise, chapter 2.] Both of them nevertheless understood the powers of the state to be limited by what rational individuals would agree to in a hypothetical or actual social contract.

The idea of the social contract lent itself to more democratic interpretations than Hobbes or Locke would have wanted. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for example, argued that the only valid social contract would be one were individuals would be subject to laws that only themselves had made and assented to, as in a small direct democracy. Today the tradition of social contract reasoning is alive in the work of John Rawls and his intellectual heirs, though in a very abstract form. Rawls argued that rational individuals would only agree to social institutions specifying a set of inviolable basic liberties and a certain amount of redistribution to alleviate inequalities for the benefit of the worst off. Lockean state of nature reasoning, by contrast, is more common in the libertarian tradition of political thought represented by the work of Robert Nozick. Nozick argued that given the natural rights that human beings would have in a state of nature, the only state that could be justified would be a minimal state whose sole functions would be to provide protection and enforce agreements.

Some contemporary thinkers, such as Michel Foucault, have argued that political theory needs to get away from the notion of the state: «We need to cut off the king’s head. In political theory that has still to be done.» [Foucault, Michel. 2000 [1976] . Truth and Power. In [http://www.amazon.com/dp/1565847091 Power] , edited by J. D. Fearon. New York: The New Press, p. 123. [http://www.amazon.com/dp/1565847091 ISBN 1565847091] ] By this he meant that power in the modern world is much more decentralized and uses different instruments than power in the early modern era, so that the notion of a sovereign, centralized state is increasingly out of date.

Others have advocated the consideration of the state within the context of complex underlying elite relationships, themselves shaped by factors that include outside pressures. This work has been prominent in the thinking of State-building theorists such as Alan Whaites, who focuses on dynamics shaping the nature and capability of states. Whaites’ model of state-building offers a conceptualization of why some states work well and others become characterized by patronage, corruption and conflict. [Whaites, Alan, States in Development: Understanding State-building, [http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/State-in-Development-Wkg-Paper.pdf] ]

See also

* Country

* Elite theory

* Failed state

* International relations

* List of countries by date of nationhood

* List of sovereign states

* Montevideo Convention

* Nation

* Nation-building

* Police state

* Political power

* Political settlement

* Province

* Regional state

* Social contract

* State-building

* State country

* Statism

* The justification of the state

* The purpose of government

* U.S. state

* Unitary state

References

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

«The State» redirects here. For other uses, see State.

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state.[1][2] One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a «state» is a polity that maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, although other definitions are not uncommon.[3][4] Absence of a state does not preclude the existence of a society, such as stateless societies like the Haudenosaunee Confederacy that «do not have either purely or even primarily political institutions or roles».[5] The level of governance of a state, government being considered to form the fundamental apparatus of contemporary states,[6][7] is used to determine whether it has failed.[8]

Most often, a country has a single state, with various administrative divisions. It is a unitary state or a federal union; in the latter type, the term «state» is sometimes used to refer to the federated polities that make up the federation. (Other terms that are used in such federal systems may include “province”, “region[citation needed]” or other terms.)

Most of the human population has existed within a state system for millennia; however, for most of prehistory people lived in stateless societies. The earliest forms of states arose about 5,500 years ago[9] as governments gained state capacity in conjunction with rapid growth of cities, invention of writing and codification of new forms of religion. Over time, a variety of forms of states developed, which used many different justifications for their existence (such as divine right, the theory of the social contract, etc.). Today, the modern nation state is the predominant form of state to which people are subject.[10] Sovereign states have sovereignty; any ingroup’s claim to have a state faces some practical limits via the degree to which other states recognize them as such.

Etymology[edit]

The word state and its cognates in some other European languages (stato in Italian, estado in Spanish and Portuguese, état in French, Staat in German) ultimately derive from the Latin word status, meaning «condition, circumstances». Latin status derives from stare, «to stand,» or remain or be permanent, thus providing the sacred or magical connotation of the political entity.

The English noun state in the generic sense «condition, circumstances» predates the political sense. It was introduced to Middle English c. 1200 both from Old French and directly from Latin.

With the revival of the Roman law in 14th-century Europe, the term came to refer to the legal standing of persons (such as the various «estates of the realm» – noble, common, and clerical), and in particular the special status of the king. The highest estates, generally those with the most wealth and social rank, were those that held power. The word also had associations with Roman ideas (dating back to Cicero) about the «status rei publicae«, the «condition of public matters». In time, the word lost its reference to particular social groups and became associated with the legal order of the entire society and the apparatus of its enforcement.[11]

The early 16th-century works of Machiavelli (especially The Prince) played a central role in popularizing the use of the word «state» in something similar to its modern sense.[12] The contrasting of church and state still dates to the 16th century. The North American colonies were called «states» as early as the 1630s.[citation needed] The expression «L’État, c’est moi» («I am the State») attributed to Louis XIV, although probably apocryphal, is recorded in the late 18th century.[13]

Definition[edit]

There is no academic consensus on the definition of the state.[1] The term «state» refers to a set of different, but interrelated and often overlapping, theories about a certain range of political phenomena.[2] According to Walter Scheidel, mainstream definitions of the state have the following in common: «centralized institutions that impose rules, and back them up by force, over a territorially circumscribed population; a distinction between the rulers and the ruled; and an element of autonomy, stability, and differentiation. These distinguish the state from less stable forms of organization, such as the exercise of chiefly power.»[14]

The most commonly used definition is by Max Weber[15][16][17][18][19] who describes the state as a compulsory political organization with a centralized government that maintains a monopoly of the legitimate use of force within a certain territory.[3][4] Weber writes that the state «is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.»[20]

While defining a state, it is important to not confuse it with a nation; an error that occurs frequently in common discussion. A state refers to a political unit with sovereignty over a given territory.[21] While a state is more of a “political-legal abstraction,” the definition of a nation is more concerned with political identity and cultural or historical factors.[21] Importantly, nations do not possess the organizational characteristics like geographic boundaries or authority figures and officials that states do.[21] Additionally, a nation does not have a claim to a monopoly on the legitimate use of force over their populace,[21] while a state does, as Weber indicated. An example of the instability that arises when a state does not have a monopoly on the use of force can be seen in African states which remain weak due to the lack of war which European states relied on.[22] A state should not be confused with a government; a government is an organization that has been granted the authority to act on the behalf of a state.[21] Nor should a state be confused with a society; a society refers to all organized groups, movements, and individuals who are independent of the state and seek to remain out of its influence.[21]

Neuberger offers a slightly different definition of the state with respect to the nation: the state is “a primordial, essential, and permanent expression of the genius of a specific [nation].»[23]

The definition of a state is also dependent on how and why they form. The contractarian view of the state suggests that states form because people can all benefit from cooperation with others[24] and that without a state there would be chaos.[25] The contractarian view focuses more on the alignment and conflict of interests between individuals in a state. On the other hand, the predatory view of the state focuses on the potential mismatch between the interests of the people and interests of the state. Charles Tilly goes so far to say that states “resemble a form of organized crime and should be viewed as extortion rackets.»[26] He argued that the state sells protection from itself and raises the question about why people should trust a state when they cannot trust one another.[21]

Tilly defines states as «coercion-wielding organisations that are distinct from households and kinship groups and exercise clear priority in some respects over all other organizations within substantial territories.»[27] Tilly includes city-states, theocracies and empires in his definition along with nation-states, but excludes tribes, lineages, firms and churches.[28] According to Tilly, states can be seen in the archaeological record as of 6000 BC; in Europe they appeared around 990, but became particularly prominent after 1490.[28] Tilly defines a state’s «essential minimal activities» as:

- War making – «eliminating or neutralizing their outside rivals»

- State making – «eliminating or neutralizing their rivals inside their own territory»

- Protection – «eliminating or neutralizing the enemies of their clients»

- Extraction – «acquiring the means of carrying out the first three activities»

- Adjudication – «authoritative settlement of disputes among members of the population»

- Distribution – «intervention in the allocation of goods among the members of the population»

- Production – «control of the creation and transformation of goods and services produced by the population»[29][30]

Importantly, Tilly makes the case that war is an essential part of state-making; that wars create states and vice versa.[31]

Modern academic definitions of the state frequently include the criteria that a state has to be recognized as such by the international community.[32]

Liberal thought provides another possible teleology of the state. According to John Locke, the goal of the state or commonwealth is «the preservation of property» (Second Treatise on Government), with ‘property’ in Locke’s work referring not only to personal possessions but also to one’s life and liberty. On this account, the state provides the basis for social cohesion and productivity, creating incentives for wealth-creation by providing guarantees of protection for one’s life, liberty and personal property. Provision of public goods is considered by some such as Adam Smith[33] as a central function of the state, since these goods would otherwise be underprovided. Tilly has challenged narratives of the state as being the result of a societal contract or provision of services in a free market – he characterizes the state more akin as a protection racket in the vein of organized crime.[30]

While economic and political philosophers have contested the monopolistic tendency of states,[34] Robert Nozick argues that the use of force naturally tends towards monopoly.[35]

Another commonly accepted definition of the state is the one given at the Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States in 1933. It provides that «[t]he state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.»[36] And that «[t]he federal state shall constitute a sole person in the eyes of international law.»[37]

Confounding the definition problem is that «state» and «government» are often used as synonyms in common conversation and even some academic discourse. According to this definition schema, the states are nonphysical persons of international law, governments are organizations of people.[38] The relationship between a government and its state is one of representation and authorized agency.[39]

Types of states[edit]

Charles Tilly distinguished between empires, theocracies, city-states and nation-states.[28] According to Michael Mann, the four persistent types of state activities are:

- Maintenance of internal order

- Military defence and aggression

- Maintenance of communications infrastructure

- Economic redistribution[40]

Josep Colomer distinguished between empires and states in the following way:

- Empires were vastly larger than states

- Empires lacked fixed or permanent boundaries whereas a state had fixed boundaries

- Empires had a «compound of diverse groups and territorial units with asymmetric links with the center» whereas a state had «supreme authority over a territory and population»

- Empires had multi-level, overlapping jurisdictions whereas a state sought monopoly and homogenization[41]

According to Michael Hechter and William Brustein, the modern state was differentiated from «leagues of independent cities, empires, federations held together by loose central control, and theocratic federations» by four characteristics:

- The modern state sought and achieved territorial expansion and consolidation

- The modern state achieved unprecedented control over social, economic, and cultural activities within its boundaries

- The modern state established ruling institutions that were separate from other institutions

- The ruler of the modern state was far better at monopolizing the means of violence[42]

States may be classified by political philosophers as sovereign if they are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Other states are subject to external sovereignty or hegemony where ultimate sovereignty lies in another state.[43] Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union. A federated state is a territorial and constitutional community forming part of a federation.[44] (Compare confederacies or confederations such as Switzerland.) Such states differ from sovereign states in that they have transferred a portion of their sovereign powers to a federal government.[45]

One can commonly and sometimes readily (but not necessarily usefully) classify states according to their apparent make-up or focus. The concept of the nation-state, theoretically or ideally co-terminous with a «nation», became very popular by the 20th century in Europe, but occurred rarely elsewhere or at other times. In contrast, some states have sought to make a virtue of their multi-ethnic or multinational character (Habsburg Austria-Hungary, for example, or the Soviet Union), and have emphasised unifying characteristics such as autocracy, monarchical legitimacy, or ideology. Other states, often fascist or authoritarian ones, promoted state-sanctioned notions of racial superiority.[46] Other states may bring ideas of commonality and inclusiveness to the fore: note the res publica of ancient Rome and the Rzeczpospolita of Poland-Lithuania which finds echoes in the modern-day republic. The concept of temple states centred on religious shrines occurs in some discussions of the ancient world.[47] Relatively small city-states, once a relatively common and often successful form of polity,[48] have become rarer and comparatively less prominent in modern times. Modern-day independent city-states include Vatican City, Monaco, and Singapore. Other city-states survive as federated states, like the present day German city-states, or as otherwise autonomous entities with limited sovereignty, like Hong Kong, Gibraltar and Ceuta. To some extent, urban secession, the creation of a new city-state (sovereign or federated), continues to be discussed in the early 21st century in cities such as London.

State and government[edit]

A state can be distinguished from a government. The state is the organization while the government is the particular group of people, the administrative bureaucracy that controls the state apparatus at a given time.[49][50][51] That is, governments are the means through which state power is employed. States are served by a continuous succession of different governments.[51] States are immaterial and nonphysical social objects, whereas governments are groups of people with certain coercive powers.[52]

Each successive government is composed of a specialized and privileged body of individuals, who monopolize political decision-making, and are separated by status and organization from the population as a whole.

States and nation-states[edit]

States can also be distinguished from the concept of a «nation», where «nation» refers to a cultural-political community of people. A nation-state refers to a situation where a single ethnicity is associated with a specific state.

State and civil society[edit]

In the classical thought, the state was identified with both political society and civil society as a form of political community, while the modern thought distinguished the nation state as a political society from civil society as a form of economic society.[53]

Thus in the modern thought the state is contrasted with civil society.[54][55][56]

Antonio Gramsci believed that civil society is the primary locus of political activity because it is where all forms of «identity formation, ideological struggle, the activities of intellectuals, and the construction of hegemony take place.» and that civil society was the nexus connecting the economic and political sphere. Arising out of the collective actions of civil society is what Gramsci calls «political society», which Gramsci differentiates from the notion of the state as a polity. He stated that politics was not a «one-way process of political management» but, rather, that the activities of civil organizations conditioned the activities of political parties and state institutions, and were conditioned by them in turn.[57][58] Louis Althusser argued that civil organizations such as church, schools, and the family are part of an «ideological state apparatus» which complements the «repressive state apparatus» (such as police and military) in reproducing social relations.[59][60][61]

Jürgen Habermas spoke of a public sphere that was distinct from both the economic and political sphere.[62]

Given the role that many social groups have in the development of public policy and the extensive connections between state bureaucracies and other institutions, it has become increasingly difficult to identify the boundaries of the state. Privatization, nationalization, and the creation of new regulatory bodies also change the boundaries of the state in relation to society. Often the nature of quasi-autonomous organizations is unclear, generating debate among political scientists on whether they are part of the state or civil society. Some political scientists thus prefer to speak of policy networks and decentralized governance in modern societies rather than of state bureaucracies and direct state control over policy.[63]

State symbols[edit]

- flag

- coat of arms or national emblem

- seal or stamp

- national motto

- national colors

- national anthem

History[edit]

The earliest forms of the state emerged whenever it became possible to centralize power in a durable way. Agriculture and a settled population have been attributed as necessary conditions to form states.[64][65][66][67] Certain types of agriculture are more conducive to state formation, such as grain (wheat, barley, millet), because they are suited to concentrated production, taxation, and storage.[64][68][69][70] Agriculture and writing are almost everywhere associated with this process: agriculture because it allowed for the emergence of a social class of people who did not have to spend most of their time providing for their own subsistence, and writing (or an equivalent of writing, like Inca quipus) because it made possible the centralization of vital information.[71] Bureaucratization made expansion over large territories possible.[72]

The first known states were created in the Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mesoamerica, and the Andes. It is only in relatively modern times that states have almost completely displaced alternative «stateless» forms of political organization of societies all over the planet. Roving bands of hunter-gatherers and even fairly sizable and complex tribal societies based on herding or agriculture have existed without any full-time specialized state organization, and these «stateless» forms of political organization have in fact prevailed for all of the prehistory and much of human history and civilization.

The primary competing organizational forms to the state were religious organizations (such as the Church), and city republics.[73]

Since the late 19th century, virtually the entirety of the world’s inhabitable land has been parcelled up into areas with more or less definite borders claimed by various states. Earlier, quite large land areas had been either unclaimed or uninhabited, or inhabited by nomadic peoples who were not organised as states. However, even within present-day states there are vast areas of wilderness, like the Amazon rainforest, which are uninhabited or inhabited solely or mostly by indigenous people (and some of them remain uncontacted). Also, there are so-called «failed states» which do not hold de facto control over all of their claimed territory or where this control is challenged. Currently the international community comprises around 200 sovereign states, the vast majority of which are represented in the United Nations.[citation needed]

Pre-historic stateless societies[edit]

For most of human history, people have lived in stateless societies, characterized by a lack of concentrated authority, and the absence of large inequalities in economic and political power.

The anthropologist Tim Ingold writes:

It is not enough to observe, in a now rather dated anthropological idiom, that hunter gatherers live in ‘stateless societies’, as though their social lives were somehow lacking or unfinished, waiting to be completed by the evolutionary development of a state apparatus. Rather, the principal of their socialty, as Pierre Clastres has put it, is fundamentally against the state.[74]

Neolithic period[edit]

During the Neolithic period, human societies underwent major cultural and economic changes, including the development of agriculture, the formation of sedentary societies and fixed settlements, increasing population densities, and the use of pottery and more complex tools.[75][76]

Sedentary agriculture led to the development of property rights, domestication of plants and animals, and larger family sizes. It also provided the basis for the centralized state form[77] by producing a large surplus of food, which created a more complex division of labor by enabling people to specialize in tasks other than food production.[78] Early states were characterized by highly stratified societies, with a privileged and wealthy ruling class that was subordinate to a monarch. The ruling classes began to differentiate themselves through forms of architecture and other cultural practices that were different from those of the subordinate laboring classes.[79]

In the past, it was suggested that the centralized state was developed to administer large public works systems (such as irrigation systems) and to regulate complex economies. However, modern archaeological and anthropological evidence does not support this thesis, pointing to the existence of several non-stratified and politically decentralized complex societies.[80]

Ancient Eurasia[edit]

Mesopotamia is generally considered to be the location of the earliest civilization or complex society, meaning that it contained cities, full-time division of labor, social concentration of wealth into capital, unequal distribution of wealth, ruling classes, community ties based on residency rather than kinship, long distance trade, monumental architecture, standardized forms of art and culture, writing, and mathematics and science.[81][82] It was the world’s first literate civilization, and formed the first sets of written laws.[83][84] Bronze metallurgy spread within Afro-Eurasia from c. 3000 BCE, leading to a military revolution in the use of bronze weaponry, which facilitated the rise of states.[85]

Classical antiquity[edit]

Although state-forms existed before the rise of the Ancient Greek empire, the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.[86]

Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population, and in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.

Feudal state[edit]

During Medieval times in Europe, the state was organized on the principle of feudalism, and the relationship between lord and vassal became central to social organization. Feudalism led to the development of greater social hierarchies.[87]

The formalization of the struggles over taxation between the monarch and other elements of society (especially the nobility and the cities) gave rise to what is now called the Standestaat, or the state of Estates, characterized by parliaments in which key social groups negotiated with the king about legal and economic matters. These estates of the realm sometimes evolved in the direction of fully-fledged parliaments, but sometimes lost out in their struggles with the monarch, leading to greater centralization of lawmaking and military power in his hands. Beginning in the 15th century, this centralizing process gives rise to the absolutist state.[88]

Modern state[edit]

Cultural and national homogenization figured prominently in the rise of the modern state system. Since the absolutist period, states have largely been organized on a national basis. The concept of a national state, however, is not synonymous with nation state. Even in the most ethnically homogeneous societies there is not always a complete correspondence between state and nation, hence the active role often taken by the state to promote nationalism through emphasis on shared symbols and national identity.[89]

Charles Tilly argues that the number of total states in Western Europe declined rapidly from the Late Middle Ages to Early Modern Era during a process of state formation.[90] Other research has disputed whether such a decline took place.[91]

For Edmund Burke (Dublin 1729 — Beaconsfield 1797), «a state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation» (Reflections on the Revolution in France).[92]

According to Hendrik Spruyt, the modern state is different from its predecessor polities in two main aspects: (1) Modern states have greater capacity to intervene in their societies, and (2) Modern states are buttressed by the principle of international legal sovereignty and the juridicial equivalence of states.[93] The two features began to emerge in the Late Middle Ages but the modern state form took centuries to come firmly into fruition.[93] Other aspects of modern states is that they tend to be organized as unified national polities, and that they have rational-legal bureaucracies.[94]

Sovereign equality did not become fully global until after World War II amid decolonization.[93] Adom Getachew writes that it was not until the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples that the international legal context for popular sovereignty was instituted.[95] Historians Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper argue that «Westphalian sovereignty» – the notion that bounded, unitary states interact with equivalent states – «has more to do with 1948 than 1648.»[96]

Theories for the emergence of the state[edit]

Earliest states[edit]

Theories for the emergence of the earliest states emphasize grain agriculture and settled populations as necessary conditions.[82] Some argue that climate change led to a greater concentration of human populations around dwindling waterways.[82]

Modern state[edit]

Hendrik Spruyt distinguishes between three prominent categories of explanations for the emergence of the modern state as a dominant polity: (1) Security-based explanations that emphasize the role of warfare, (2) Economy-based explanations that emphasize trade, property rights and capitalism as drivers behind state formation, and (3) Institutionalist theories that sees the state as an organizational form that is better able to resolve conflict and cooperation problems than competing political organizations.[93]

According to Philip Gorski and Vivek Swaroop Sharma, the «neo-Darwinian» framework for the emergence of sovereign states is the dominant explanation in the scholarship.[97] The neo-Darwininian framework emphasizes how the modern state emerged as the dominant organizational form through natural selection and competition.[97]

Theories of state function[edit]

Most political theories of the state can roughly be classified into two categories. The first are known as «liberal» or «conservative» theories, which treat capitalism as a given, and then concentrate on the function of states in capitalist society. These theories tend to see the state as a neutral entity separated from society and the economy. Marxist and anarchist theories on the other hand, see politics as intimately tied in with economic relations, and emphasize the relation between economic power and political power. They see the state as a partisan instrument that primarily serves the interests of the upper class.[51]

Anarchist perspective[edit]

Anarchism is a political philosophy which considers the state and hierarchies to be unnecessary and harmful and instead promotes a stateless society, or anarchy, a self-managed, self-governed society based on voluntary, cooperative institutions.

Anarchists believe that the state is inherently an instrument of domination and repression, no matter who is in control of it. Anarchists note that the state possesses the monopoly on the legal use of violence. Unlike Marxists, anarchists believe that revolutionary seizure of state power should not be a political goal. They believe instead that the state apparatus should be completely dismantled, and an alternative set of social relations created, which are not based on state power at all.[98][99]

Various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the state and political power as the Beast in the Book of Revelation.[100][101]

Anarcho-capitalist perspective[edit]