A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsory.[2] In these systems, students progress through a series of schools. The names for these schools vary by country (discussed in the Regional terms section below) but generally include primary school for young children and secondary school for teenagers who have completed primary education. An institution where higher education is taught is commonly called a university college or university.

In addition to these core schools, students in a given country may also attend schools before and after primary (elementary in the U.S.) and secondary (middle school in the U.S.) education.[3] Kindergarten or preschool provide some schooling to very young children (typically ages 3–5). University, vocational school, college or seminary may be available after secondary school. A school may be dedicated to one particular field, such as a school of economics or dance. Alternative schools may provide nontraditional curriculum and methods.

Non-government schools, also known as private schools,[4] may be required when the government does not supply adequate or specific educational needs. Other private schools can also be religious, such as Christian schools, gurukula (Hindu schools), madrasa (Arabic schools), hawzas (Shi’i Muslim schools), yeshivas (Jewish schools), and others; or schools that have a higher standard of education or seek to foster other personal achievements. Schools for adults include institutions of corporate training, military education and training and business schools.

Critics of school often accuse the school system of failing to adequately prepare students for their future lives,[5] of encouraging certain temperaments while inhibiting others,[6] of prescribing students exactly what to do, how, when, where and with whom, which would suppress creativity,[7] and of using extrinsic measures such as grades and homework, which would inhibit children’s natural curiosity and desire to learn.[8]

In homeschooling and distance education, teaching and learning take place independent from the institution of school or in a virtual school outside a traditional school building, respectively. Schools are organized in several different organizational models, including departmental, small learning communities, academies, integrated, and schools-within-a-school.

Etymology

The word school derives from Greek σχολή (scholē), originally meaning «leisure» and also «that in which leisure is employed», but later «a group to whom lectures were given, school».[9][10][11]

History and development

The concept of grouping students together in a centralized location for learning has existed since Classical antiquity. Formal schools have existed at least since ancient Greece (see Academy), ancient Rome (see Education in Ancient Rome) ancient India (see Gurukul), and ancient China (see History of education in China). The Byzantine Empire had an established schooling system beginning at the primary level. According to Traditions and Encounters, the founding of the primary education system began in 425 AD and «… military personnel usually had at least a primary education …». The sometimes efficient and often large government of the Empire meant that educated citizens were a must. Although Byzantium lost much of the grandeur of Roman culture and extravagance in the process of surviving, the Empire emphasized efficiency in its war manuals. The Byzantine education system continued until the empire’s collapse in 1453 AD.[12]

In Western Europe, a considerable number of cathedral schools were founded during the Early Middle Ages in order to teach future clergy and administrators, with the oldest still existing, and continuously operated, cathedral schools being The King’s School, Canterbury (established 597 CE), King’s School, Rochester (established 604 CE), St Peter’s School, York (established 627 CE) and Thetford Grammar School (established 631 CE). Beginning in the 5th century CE, monastic schools were also established throughout Western Europe, teaching religious and secular subjects.

In Europe, universities emerged during the 12th century; here, scholasticism was an important tool, and the academicians were called schoolmen. During the Middle Ages and much of the Early Modern period, the main purpose of schools (as opposed to universities) was to teach the Latin language. This led to the term grammar school, which in the United States informally refers to a primary school, but in the United Kingdom means a school that selects entrants based on ability or aptitude. The school curriculum has gradually broadened to include literacy in the vernacular language and technical, artistic, scientific, and practical subjects.

Obligatory school attendance became common in parts of Europe during the 18th century. In Denmark-Norway, this was introduced as early as in 1739–1741, the primary end being to increase the literacy of the almue, i.e., the «regular people».[13] Many of the earlier public schools in the United States and elsewhere were one-room schools where a single teacher taught seven grades of boys and girls in the same classroom. Beginning in the 1920s, one-room schools were consolidated into multiple classroom facilities with transportation increasingly provided by kid hacks and school buses.

Islam was another culture that developed a school system in the modern sense of the word. Emphasis was put on knowledge, which required a systematic way of teaching and spreading knowledge and purpose-built structures. At first, mosques combined religious performance and learning activities. However, by the 9th century, the madrassa was introduced, a school that was built independently from the mosque, such as al-Qarawiyyin, founded in 859 CE. They were also the first to make the Madrassa system a public domain under Caliph’s control.

Under the Ottomans, the towns of Bursa and Edirne became the main centers of learning. The Ottoman system of Külliye, a building complex containing a mosque, a hospital, madrassa, and public kitchen and dining areas, revolutionized the education system, making learning accessible to a broader public through its free meals, health care, and sometimes free accommodation.

Regional terms

The term school varies by country, as do the names of the various levels of education within the country.

United Kingdom and Commonwealth of Nations

In the United Kingdom, the term school refers primarily to pre-university institutions, and these can, for the most part, be divided into pre-schools or nursery schools, primary schools (sometimes further divided into infant school and junior school), and secondary schools. Various types of secondary schools in England and Wales include grammar schools, comprehensives, secondary moderns, and city academies. While they may have different names in Scotland, there is only one type of secondary school. However, they may be funded either by the state or independently funded. Scotland’s school performance is monitored by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education. Ofsted reports on performance in England and Estyn reports on performance in Wales.

In the United Kingdom, most schools are publicly funded and known as state schools or maintained schools in which tuition is provided for free. There are also private schools or private schools that charge fees. Some of the most selective and expensive private schools are known as public schools, a usage that can be confusing to speakers of North American English. In North American usage, a public school is publicly funded or run.

In much of the Commonwealth of Nations, including Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, and Tanzania, the term school refers primarily to pre-university institutions.

India

In ancient India, schools were in the form of Gurukuls. Gurukuls were traditional Hindu residential learning schools, typically the teacher’s house or a monastery. Schools today are commonly known by the Sanskrit terms Vidyashram, Vidyalayam, Vidya Mandir, Vidya Bhavan in India.[14][15] In southern languages, it is known as Pallikoodam or PaadaSaalai. During the Mughal rule, Madrasahs were introduced in India to educate the children of Muslim parents. British records show that indigenous education was widespread in the 18th century, with a school for every temple, mosque, or village in most regions. The subjects taught included Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Theology, Law, Astronomy, Metaphysics, Ethics, Medical Science, and Religion.

A school building in Kannur, India

Under British rule, Christian missionaries from England, the United States, and other countries established missionary and boarding schools in India. Later as these schools gained popularity, more were started, and some gained prestige. These schools marked the beginning of modern schooling in India. The syllabus and calendar they followed became the benchmark for schools in modern India. Today most schools follow the missionary school model for tutoring, subject/syllabus, and governance, with minor changes.

Schools in India range from large campuses with thousands of students and hefty fees to schools where children are taught under a tree with a small / no campus and are free of cost. There are various boards of schools in India, namely Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), Madrasa Boards of various states, Matriculation Boards of various states, State Boards of various boards, Anglo Indian Board, among others. Today’s typical syllabus includes Language(s), Mathematics, Science – Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Geography, History, General Knowledge, and Information Technology/Computer Science. Extracurricular activities include physical education/sports and cultural activities like music, choreography, painting, and theatre/drama.

Europe

In much of continental Europe, the term school usually applies to primary education, with primary schools that last between four and nine years, depending on the country. It also applies to secondary education, with secondary schools often divided between Gymnasiums and vocational schools, which again, depending on country and type of school, educate students for between three and six years. In Germany, students graduating from Grundschule are not allowed to progress into a vocational school directly. Instead, they are supposed to proceed to one of Germany’s general education schools such as Gesamtschule, Hauptschule, Realschule or Gymnasium. When they leave that school, which usually happens at age 15–19, they may proceed to a vocational school. The term school is rarely used for tertiary education, except for some upper or high schools (German: Hochschule), which describe colleges and universities.

In Eastern Europe modern schools (after World War II), of both primary and secondary educations, often are combined. In contrast, secondary education might be split into accomplished or not. The schools are classified as middle schools of general education. For the technical purposes, they include «degrees» of the education they provide out of three available: the first – primary, the second – unaccomplished secondary, and the third – accomplished secondary. Usually, the first two degrees of education (eight years) are always included. In contrast, the last one (two years) permits the students to pursue vocational or specialized educations.

North America and the United States

In North America, the term school can refer to any educational institution at any level and covers all of the following: preschool (for toddlers), kindergarten, elementary school, middle school (also called intermediate school or junior high school, depending on specific age groups and geographic region), high school (or in some cases senior high school), college, university, and graduate school.

In the United States, school performance through high school is monitored by each state’s department of education. Charter schools are publicly funded elementary or secondary schools that have been freed from some of the rules, regulations, and statutes that apply to other public schools. The terms grammar school and grade school are sometimes[why?] used to refer to a primary school. In addition, there are tax-funded magnet schools which offer different programs and instruction not available in traditional schools.

Africa

In West Africa, «school» can also refer to «bush» schools, Quranic schools, or apprenticeships. These schools include formal and informal learning.

Bush schools are training camps that pass down cultural skills, traditions, and knowledge to their students. Bush schools are semi-similar to traditional western schools because they are separated from the larger community. These schools are located in forests outside of the towns and villages, and the space used is solely for these schools. Once the students have arrived in the forest, they cannot leave until their training is complete. Visitors are prohibited from these areas.[16]

Instead of being separated by age, Bush schools are separated by gender. Women and girls cannot enter the boys’ bush school territory and vice versa. Boys receive training in cultural crafts, fighting, hunting, and community laws among other subjects.[17] Girls are trained in their own version of the boys’ bush school. They practice domestic affairs such as cooking, childcare, and being a good wife. Their training is focused on how to be a proper woman by societal standards.

Qur’anic schools are the principal way of teaching the Quran and knowledge of the Islamic faith. These schools also fostered literacy and writing during the time of colonization. Today, the emphasis is on the different levels of reading, memorizing, and reciting the Quran. Attending a Qur’anic school is how children become recognized members of the Islamic faith. Children often attend state schools and a Qur’anic school.

In Mozambique, specifically, there are two kinds of Qur’anic schools. They are the tariqa based and the Wahhabi-based schools. What makes these schools different is who controls them. Tariqa schools are controlled at the local level. In contrast, the Wahhabi are controlled by the Islamic Council.[18] Within the Qur’anic school system, there are levels of education. They range from a basic level of understanding, called chuo and kioni in local languages, to the most advanced, which is called ilimu.[19]

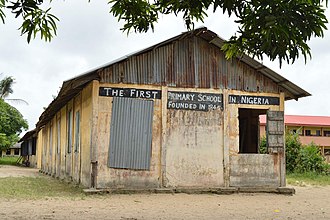

In Nigeria, the term school broadly covers daycares, nursery schools, primary schools, secondary schools and tertiary institutions. Primary and secondary schools are either privately funded by religious institutions and corporate organisations or government-funded. Government-funded schools are commonly referred to as public schools. Students spend six years in primary school, three years in junior secondary school, and three years in senior secondary school. The first nine years of formal schooling is compulsory under the Universal Basic Education Program (UBEC).[20] Tertiary institutions include public and private universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education. Universities can be funded by the federal government, state governments, religious institutions, or individuals and organisations.

Ownership and operation

Many schools are owned or funded by states. Private schools operate independently from the government. Private schools usually rely on fees from families whose children attend the school for funding; however, sometimes such schools also receive government support (for example, through School vouchers). Many private schools are affiliated with a particular religion; these are known as parochial schools.

Components of most schools

A school entrance building in Australia

Schools are organized spaces purposed for teaching and learning. The classrooms where teachers teach and students learn are of central importance. Classrooms may be specialized for certain subjects, such as laboratory classrooms for science education and workshops for industrial arts education.

Typical schools have many other rooms and areas, which may include:

- Cafeteria (Commons), dining hall or canteen where students eat lunch and often breakfast and snacks.

- Athletic field, playground, gym, or track place where students participating in sports or physical education practice

- Schoolyards, all-purpose playfields typically in elementary schools, often made of concrete.

- Auditorium or hall where student theatrical and musical productions can be staged and where all-school events such as assemblies are held

- Office where the administrative work of the school is done

- Library where students ask librarians reference questions, check out books and magazines, and often use computers

- Computer labs where computer-based work is done and the internet accessed

- Cultural activities where the students uphold their cultural practice through activities like games, dance, and music

Education facilities in low-income countries

In low-income countries, only 32% of primary, 43% of lower secondary and 52% of upper secondary schools have access to electricity.[21] This affects access to the internet, which is just 37% in upper secondary schools in low-income countries, as compared to 59% in those in middle-income countries and 93% in those in high-income countries.[21]

Access to basic water, sanitation and hygiene is also far from universal. Among upper secondary schools, only 53% in low-income countries and 84% in middle-income countries have access to basic drinking water. Access to water and sanitation is universal in high-income countries.[21]

Security

The safety of staff and students is increasingly becoming an issue for school communities, an issue most schools are addressing through improved security. Some have also taken measures such as installing metal detectors or video surveillance. Others have even taken measures such as having the children swipe identification cards as they board the school bus. These plans have included door numbering to aid public safety response for some schools.[clarification needed]

Other security concerns faced by schools include bomb threats, gangs, and vandalism.[22] In recognition of these threats, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 advocates for upgrading education facilities to provide a safe, non-violent learning environment.[23]

Health services

School health services are services from medical, teaching and other professionals applied in or out of school to improve the health and well-being of children and, in some cases, whole families. These services have been developed in different ways around the globe. However, the fundamentals are constant: the early detection, correction, prevention, or amelioration of disease, disability, and abuse from which school-aged children can suffer.

Online schools and classes

Some schools offer remote access to their classes over the internet. Online schools also can provide support to traditional schools, as in the case of the School Net Namibia. Some online classes also provide experience in a class. When people take them, they have already been introduced to the subject and know what to expect. Classes provide high school/college credit, allowing students to take the classes at their own pace. Many online classes cost money to take, but some are offered free.

Internet-based distance learning programs are offered widely through many universities. Instructors teach through online activities and assignments. Online classes are taught the same as in-person, with the same curriculum. The instructor offers the syllabus with their fixed requirements like any other class. Students can virtually turn their assignments in to their instructors according to deadlines. This being through via email or on the course webpage. This allows students to work at their own pace yet meet the correct deadlines. Students taking an online class have more flexibility in their schedules to take their classes at a time that works best.

Conflicts with taking an online class may include not being face to face with the instructor when learning or being in an environment with other students. Online classes can also make understanding the content challenging, especially when unable to get in quick contact with the instructor. Online students have the advantage of using other online sources with assignments or exams for that specific class. Online classes also have the advantage of students not needing to leave their house for a morning class or worrying about their attendance for that class. Students can work at their own pace to learn and achieve within that curriculum.[24]

The convenience of learning at home has been an attraction point for enrolling online. Students can attend class anywhere a computer can go – at home, in a library, or while traveling internationally. Online school classes are designed to fit a student’s needs while allowing students to continue working and tending to their other obligations.[25] Online school education is divided into three subcategories: Online Elementary School, Online Middle School, Online High school.

Stress

As a profession, teaching has levels of work-related stress (WRS)[26] that are among the highest of any profession in some countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States.[27] The degree of this problem is becoming increasingly recognized and support systems are being put into place.[28][29]

Stress sometimes affects students more severely than teachers, up to the point where the students are prescribed stress medication. This stress is claimed to be related to standardized testing, and the pressure on students to score above average.[30][31]

According to a 2008 mental health study by the Associated Press and mtvU,[32] eight in 10 U.S. college students said they had sometimes or frequently experienced stress in their daily lives. This was an increase of 20% from a survey five years previously. Thirty-four percent had felt depressed at some point in the past three months, 13 percent had been diagnosed with a mental health condition such as an anxiety disorder or depression, and 9 percent had seriously considered suicide.[32]

Discipline towards students

The activity of carrying out the flag ceremony at Indonesian schools every Monday morning, With the aim of educating discipline and a sense of national spirit

Schools and their teachers have always been under pressure – for instance, pressure to cover the curriculum, perform well compared to other schools, and avoid the stigma of being «soft» or «spoiling» toward students. Forms of discipline, such as control over when students may speak, and normalized behaviour, such as raising a hand to speak, are imposed in the name of greater efficiency. Practitioners of critical pedagogy maintain that such disciplinary measures have no positive effect on student learning. Indeed, some argue that disciplinary practices detract from learning, saying that they undermine students’ dignity and sense of self-worth – the latter occupying a more primary role in students’ hierarchy of needs.

See also

- Bullying in teaching

- Criticism of schooling

- Educational technology

- Free education

- List of colleges and universities by country

- List of schools by country

- List of songs about school

- List of television series about school

- Mobile phone use in schools

- Music school

- Secular education

- School and university in literature

- School bullying

- School meal

- School story

- School uniform

- School-to-prison pipeline

- Student transport

- Teaching for social justice

- University-preparatory school

- Year-round school

References

- ^ Research handbook on innovation governance for emerging economies : towards better models. Kuhlmann, Stefan. Cheltehnham, UK. 27 January 2017. ISBN 978-1-78347-191-1. OCLC 971520924.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Roser, Max; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (2019). «Primary and Secondary Education». Our World in Data. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ «Understanding the American Education System». www.studyusa.com. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ [1], Ganesh Harpavat, International Schools, on Perseus

- ^ «Schools don’t prepare children for life. Here’s the education they really need | Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett». The Guardian. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Keogh, Barbara (9 September 2009). «Why it’s important to understand your child’s temperament». www.greatschools.org. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Sir Ken (27 June 2006), Do schools kill creativity?, retrieved 4 August 2021

- ^ «‘Schools are killing curiosity’: why we need to stop telling children to shut up and learn». The Guardian. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary; H.G. Liddell & R. Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ School[dead link], on Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ σχολή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Bentley, Jerry H. (2006). Traditions & Encounters a Global Perspective on the Past. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 331.

- ^ «Leseferdighet og skolevesen 1740–1830» (PDF). Open Digital Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ «School Meaning Sanskrit Arth Translate Kya Matlab». www.bsarkari.com. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (13 January 2019). «Vidyalaya, Vidyālaya, Vidya-alaya: 7 definitions». www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Watkins Hanna, Mark (May 1943). «The West African «Bush» School». American Journal of Sociology. 48 (6): 666–675. doi:10.1086/219263. S2CID 144208852.

- ^ Watkins Hanna, Mark (May 1943). «The West African «Bush» Schools». American Journal of Sociology. 48 (6): 666–675. doi:10.1086/219263. S2CID 144208852.

- ^ Bonate, Liazat (2016). Islamic Education in Africa. Indiana University Press.

- ^ Bonate, Lizzat (2016). Islamic Education in Africa. Indiana University Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^ «Universal Basic Education Commission | Home». www.ubec.gov.ng. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b c #CommitToEducation. UNESCO. 2019. ISBN 978-92-3-100336-3.

- ^ «School Vandalism Takes Its Toll». Wrensolutions.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ «SDG4’s 10 targets». Global Campaign For Education. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Laird, Ellen. «I’m Your Teacher, Not Your Internet-Service Provider.» Chronicle of Higher Education n.d.: n.p. Print

- ^ «Online Education Offers Access and Affordability». Usnews.com. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ «Work-Related Stress in teaching». Wrsrecovery.com. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Ross, Genesis R. (2010). Teacher Stress, Burnout and NCLB: The U.S. Educational Ecosystem and the Adaptation of Teachers (MS thesis). Miami University. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Teacher Support for England & Wales». Teachersupport.info. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ «Teacher Support for Scotland». Teachersupport.info. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ «Survey confirms student stress, but next step is unclear (May 06, 2005)». Paloaltoonline.com. 6 May 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ «Children & School Anxiety, Stress Management». Webmd.com. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ a b «mtvU and Associated Press poll shows how stress, war, the economy and other factors are affecting college students’ mental health» (PDF). Half Of Us. 19 March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013.

Further reading

- Dodge, B. (1962). Muslim Education in the Medieval Times, The Middle East Institute, Washington D.C.

- Education as Enforcement: The Militarization and Corporatization of Schools, edited by Kenneth J. Saltman and David A. Gabbard, RoutledgeFalmer 2003. Review.

- Makdisi, G. (1980). On the origin and development of the college in Islam and the West, in Islam and the Medieval West, ed. Khalil I. Semaan, State University of New York Press.

- Nakosteen, M. (1964). History of Islamic origins of Western Education AD 800–1350, University of Colorado Press, Boulder.

- Ribera, J. (1928). Disertaciones Y Opusculos, 2 vols., Madrid.

- Spielhofer, Thomas, Tom Benton, Sandie Schagen. «A study of the effects of school size and single-sex education in English schools.» Research Papers in Education, June 2004:133 159, 27.

- Toppo, Greg. «High-tech school security is on the rise.» USA Today, 9 October 2006.

- Traditions and Encounters, by Jerry H. Bentley and Herb F. Ziegler.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from #CommitToEducation, 35, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO. To learn how to add open license text to Wikipedia articles, please see this how-to page. For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

External links

The word «school» is so familiar in our vocabulary that few people are interested in where the word came from. «School» — so it is pronounced in Russian, «schoe» — as it sounded in ancient Greece, where it comes from. True, it was interpreted a little differently: «rest», «leisure» and «idleness», in other words — «pleasant pastime». The etymology of the word «school» implied that it was not complete inaction and relaxation, but the management of clever and instructive conversations, the favorite art of Greek philosophers, in their spare time. Over time, these wise men and thinkers had permanent students, and the concept of «school» began to denote the educational process, and later the premises adapted to it.

Classes in the school of the past did not differ much from modern lessons. Naturally, the temporary difference has made its own adjustments, but the principle is painfully similar to what we are accustomed to: the same disobedient disciples, strict teachers and bored lessons.

School of Ancient Time

The process of education was still at the very first stage of human development, so we can assume that the first schools appeared exactly at that time. The meaning of the word «school» in the Ancient World bore a different meaning: the children were taught not to read and write (it still did not exist), but the ability to survive in the world around them. The ability to hunt and martial arts were the most important lessons for boys. Girls, like at all times, mastered farming, needlework, cooking. Well and where without examinations? Of course, they were, but represented a difficult test, the so-called «initiation rite.» The young man, for testing his willpower and patience, could be tormented by fire, beat, cut through the skin, which almost always caused the teenager to lose consciousness. The successful passing of such an examination was for the boy pride, as he became a full member of an adult society.

Sumerians: a highly educated nation

Very interesting information has been preserved about the schools of Sumerians — one of the first civilizations. «The house of tablets» — the so-called educational institutions of the population, which for 3 thousand years BC. E. Mastered pottery, skillfully irrigated fields, weaved, spun, forged tools of labor from copper and bronze.

The Sumerians skillfully wrote poems, composed music, had their own writing, knew astronomy, and mastered the main rules of algebra (multiplication, division and even extraction from the square root). It was such schools that gave way to the young men who later became leaders.

School in Egypt

It was very hard for the students of Egypt, because the learning process was complicated: it was required to know more than 700 characters, the writing of which required great accuracy.

An indispensable subject of training was the three-tailed whip that lay at the feet of the teacher. The pupils began school hours with memorizing verses, repeating large passages aloud for the teacher, and at the end of the day they could already freely tell them.

How the ancient Greeks learned

In Ancient Greece, school attendance was allowed exclusively for boys from wealthy families — the sons of slaves were not there, so they had to start working from an early age. The girls were at home training, under the supervision of their mother, and mastered the sciences, which could be useful to them in their future family life: housekeeping, music, needlework, weaving and, of course, literacy. Studying at school was paid. And since the Athenians, like all slave owners, despised people working for money, then the teachers did not use respect in society. The meaning of the word «school» was associated with the teacher, and hence with the poor way of life that he led. If a person has not received any news for a long time, then his acquaintances said that the latter either died or became a teacher. A beggarly existence did not allow him to even make himself felt.

The boys attended the school from the age of 7 and necessarily accompanied by a slave-educator who looked after the child and carried his school things. The main lessons were writing, reading and counting. It is from those ancient times that the word «school» originates.

The reading consisted of studying Homer’s poems — «Illyada» and «Odyssey.» In addition to gaining additional knowledge of geography, the child was exemplified by the courage and perseverance of the heroes of works in the struggle against difficulties.

In the account visual aids were pebbles and a special board with the numbers of numbers marked on it: units, tens, hundreds.

The letter was first dealt with on a ditch from wood covered with wax, and later on papyrus. The predecessor of the modern handle was a style — a special metal or bone stick, sharpened from one end.

Particular attention was paid to music, which was an integral part of the life of the Greeks. Each boy learned to sing and play the flute or cithara.

Also, students diligently engaged in gymnastics, giving the body harmony, flexibility — Greece needed a healthy nation.

Unlike modern schools (in which the origin of the word «school» interests a small percentage of students), in institutions of the past, teachers could punish children for disobedience and poor academic performance. For this there was a stick and rods.

At school, classes were completed by the age of 16. Children of wealthy parents for another 2 years could continue their education.

1 September is the day of knowledge

The history of the word «school» is always associated with the date of September 1 — the next vital step with bouquets of flowers, a meeting with friends and the first bell. Why did the choice fall on this day for the start of the school year? If the origin of the word «school» is associated with Ancient Greece, then the Byzantium is the founder of the autumn tradition, in which September 1 marked the beginning of the creation of the world by the Lord. It was to this number that field work ended, in which both old and young were involved. Grand Prince Ivan III at the end of the XV century announced on September 1 the beginning of the New Year (otherwise, Novoliyet) and the church-state holiday. Later, according to the decree of Peter the Great, the New Year was transferred to the usual for everyone on January 1, and the church calendar and agricultural calendar were left unchanged due to the employment of the population during the agricultural hardship period.

On September 1, the doors of schools open in countries such as the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic States. In Germany and Spain in each province, the academic year depends on the timing of harvesting and begins no later than October 1. In Italy, this date is the starting point. Children of the Danes go to school in mid-August, and the British, Canadians and Americans — on the first Tuesday of September. The etymology of the word «school» unites all countries, even Japan, sending the younger generation to get knowledge on April 1.

The meaning of the word «school»

In modern Russian, the word «school» is given much more importance than we are accustomed to. So, synonyms for the word «school» can be easily selected, knowing its full meaning. It:

- Educational institution (primary and secondary, higher school);

- A specialized educational institution (music, children’s sports school);

- The educational system as a whole;

- Training, overgrowth of experience (philological school, school of life);

- Socio-political, scientific and artistic direction (Moscow Linguistic School, School of Modern Art);

- Nursery for growing plants.

Based on the above definitions, you can choose synonyms for the word «school». It is an educational institution, a school, a gymnasium, a nursery, a film school, intelligence school, a boarding school, preparedness, style, class, skill and a number of other words.

School: root and root words

The root of the word «school» is the basis for such derivatives: «schoolboy», «schoolgirl», «school», «schoolboy», «schoolchildren». By the way, the word «schoolboy» is understood as «indulging», «babbling», that is, to lead like a schoolboy. «Schoolchildren» refers to the tricks inherent in the student, the child. Earlier in use was the word «schoolboy», according to a mistaken opinion, borrowed from the Ukrainian language and is now obsolete. In fact, it has Polish roots («szkolarz» — so it is written by the Poles). From the word «schoolboy» there are derivatives — «schooling» and «schoolboy», the meaning of which in the Ukrainian language bears both positive and negative meaning and is deciphered as:

- Collective to the «schoolboy»;

- Stay in school;

- Adherence to primitive, dogmatic norms, patterns, a helpless pupil approach to anything.

- A student of bad behavior;

- Disrespectful attitude towards the individual. This can be observed in the works of many Russian writers.

According to the interpretation of V. Dal, «schooling» is defined as a dry and dull drill, pedantry, persistently following the accepted, often nonsensical and petty rules.

The origin of the word «school» according to Y. Kamensky

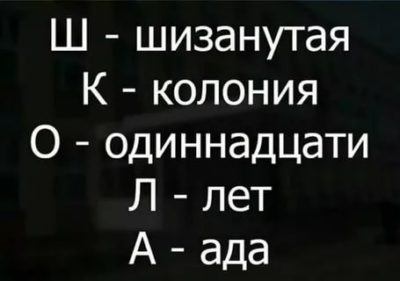

There is another version of the origin of the word «school», consisting of an abbreviation, which was invented by the Czech teacher and thinker J. Kamensky (1562-1670). He developed a well-known idea of universal education in his native language, and gave the name from the initial letters of the motto, translated into Russian as «It’s wise to think, act nobly, and skillfully speak.»

History of some words

Just as the history of the word «school», the origin of the words associated with it attracts attention.

Portfolio. It has French roots and consists of two parts: «port» («wear») and «fel» («sheet of paper»).

Notebook. It comes from the Greek «tetradion», which means «folded out of four parts». It is in this way that the Greeks made notebooks in ancient times, sewing four leaves for comfort.

Holidays. The favorite word of all schoolboys in a literal translation from Latin means «doggies». Where is the connection? «Vacation» (doggie), the Romans called the star Sirius, as they thought — the hunting dog of Orion the trapper. At the appearance of Sirius in Rome, a very hot summer came and a break was declared in all classes, which was called «vacations».

School, lyceum, gymnasium, academy who invented all this ?! — Orthodox journal

What does school have to do with rest? Why was it customary in the gymnasium to study without clothes? What ancient Greek hero was buried at the academy? What connects the pagan god Apollo with the Lyceum?

School is about rest

School. Who would have thought that this is about vacation! However, if we turn to the ancient Greek language, from where this word migrated to us, it turns out that this is really so. Sholē (schole) means leisure, rest, the opportunity to spend time freely, idle.

Moreover, this leisure itself was perceived by the ancient Greek as an absolute value, as the only worthy way of spending time. Physical labor in antiquity was despised because it is not leisure, and therefore, a deviation from the normal way of life. For us, modern people, this is, of course, nonsense.

We live in a society where it is simply not accepted not to work, and we call the one who shies away from work «parasites» or «nets».

But for the ancient Greeks, it was the opposite: if you work, then you are a slave and must provide everything necessary for a class of free people, who, in turn, could use their leisure time to become worthy citizens. And the educational system just served this purpose — to educate a person whose activity, as Aristotle notes, will be virtuous.

Moreover, genuine teaching — for the ancients it was very important — was thought possible only when a person was freed from the «difficulties» of labor, when his head was not occupied with worries and worries about the future. And here it is interesting to note that the word «schollet» also meant enchanted contemplation, a kind of cutting off of everything that interferes with a pure and direct perception of nature or some kind of phenomenon.

And this connotation of «schollet» surprisingly resonates with Christian theology, and more specifically, with the ideal of the monastery and monastic life.

As you know, monasteries began to form in the XNUMXth century. They were founded at first, as a rule, away from crowded and noisy cities. Why? Precisely because one of the main goals of monastic life is divine contemplation, that is, the complete aspiration of the mind to God.

And perhaps this is when the world around a person and his inner world are completely calmed down, when vanity, noise and anxiety are left somewhere behind a closed door. The very possibility of contemplating God, as the famous holy blessed Augustine wrote, opens up when a person refuses any form of activity. Achieving «peace» of thought is the path to God-thinking.

And when the saint speaks of «peace», he uses the Latin word «otium», which in its meaning is very close to the Greek «schola». It turns out that a genuine, sublime school is the path to God-thinking.

Gymnasium is about asceticism

Today, a gymnasium is an educational institution with an in-depth educational program with some subjects that, as a rule, are not taught in a regular school. But initially the gymnasium was not intended at all for this.

In ancient Greece, from where the word «gymnasium» (γυμνάσιον) came to us, it was believed that the ideal citizen was supposed to be developed not only intellectually, but also physically. In everything, as you know, the Greeks strove to observe the ideal of measure, which meant that both the mind and the body of a person should be equally perfect. In addition, in the event of war, each citizen was obliged to take up arms and protect his policy, for which, again, some preparation was required.

And for this, a gymnasium was set up — a platform for physical exercises. The word itself comes from «γυμνός» (gymnos), which means naked, naked. Indeed, youths in Greece went in for sports without clothes. It is assumed that this custom appeared after the thirty-second Olympics, when one of the participants in the competition managed to reach the finish line first due to the fact that a loincloth came off him.

But later, the functions of the gymnasium expanded significantly. A whole complex of buildings appeared, where it was possible not only to exercise, but also to develop one’s intellect: politics, rhetoric, literature, philosophy were studied here, many hours of conversations and discussions were held, in which scientists-philosophers took part.

However, if we return to the original meaning of the gymnasium as a place for training or as an exercise in general, we will see that Christianity has its own gymnasium — asceticism.

After all, if you look at the Greek word askēsis (ἄσκησις), it turns out that it also translates as exercise, training.

Therefore, ascetic practice is not about the infringement and mortification of the human body. Everything is quite the opposite: asceticism is the training of the body and soul for their strengthening and final transformation. In other words, a Christian gymnasium is a system of exercises that bring a person closer to God.

Academy and its holy graduates

Today the Academy is both a huge scientific organization and a higher educational institution that trains experts and teachers for universities. However, it was originally the name of one of the most famous and elite gymnasiums in the Athenian policy. The Academy (Ἀκαδήμεια) was founded by the famous philosopher Plato in 386 BC and got its name from the sacred olive grove, where the school buildings were located and where, according to legend, the ancient Greek hero Akadem was buried.

In fact, it was here that the first scientific traditions were formed, which became exemplary for all subsequent generations of scientists and researchers. Moreover, such great Church Fathers as Saints Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian passed through the Plato Academy.

And largely thanks to the education they received at this Academy, they managed to make a real breakthrough in Christian theology.

Not to mention the fact that, in principle, most of the Church Fathers were intellectually connected with the educational system that took shape in the Academy and other famous schools of antiquity.

Lyceum: why walks are good for study

In 1811, the grand opening of the Imperial Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum took place, which we first of all know because Pushkin studied there.

It cannot be said that the poet showed himself here as a brilliant student — according to the results of the final exams, Alexander Sergeevich took only 26th place among 29 students — but his name, of course, glorified the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum for centuries.

It is all the more interesting that Pushkin is connected with the great philosopher of antiquity, Aristotle, precisely through the beloved educational institution he praised in many poems.

Lyceum (Λύκειον) — in the Latin pronunciation «lyceum» — is the most famous elite gymnasium of antiquity, founded by this famous philosopher. Aristotle rented buildings for his gymnasium near the temple in honor of Apollo of Lycea, from which the name of the school came.

Lyceum, by the way, is also known as Peripatos — this was the name of the city gardens intended for walking. Here free Greeks could not only hide from the heat of the day, but also listen to philosophical conversations, lectures and speeches of scientists.

At the school of Aristotle, some classes were taught to be conducted during leisurely walks along the paths of the garden located on the territory of Lyceum, and therefore the students of this gymnasium were sometimes called «peripatetics».

The practice of such philosophical walks was reflected in the work of the artist Mikhail Nesterov, who painted the famous pair portrait «Philosophers». This painting depicts the priest Pavel Florensky and Sergiy Bulgakov, leisurely walking and talking with each other, the outstanding representatives of religious and philosophical thought.

So walks can be very beneficial for your studies. Especially if they are held in the company of a great philosopher.

Source: https://foma.ru/shkola-litsey-gimnaziya-akademiya-kto-voobshhe-vse-eto-pridumal.html

How to transfer a child to another school?

We want to transfer the child to another school, is it possible? Can a school refuse to accept a student during the school year? What is the transfer procedure? How long should a personal file be issued?

The right to choose a school

According to the law, parents of underage students have the right to choose an educational institution (clause 3 of article 44 of the Federal Law «On Education in the Russian Federation»). Circumstances may be different: change of place of residence, relations in the team have not developed, the quality of education is not satisfied, etc. Parents are concerned about the questions: is it possible to transfer during the school year and how to do it.

Is it possible to transfer to another school in the middle of the school year

You can transfer to another school at any time. According to the current legislation, any school to which a parent applies has no right to refuse admission, except in cases where there are no free places at the school. Priority should be given to admitting children admitted “at the place of residence”. However, on the basis of the Order of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation No. 32, for those who do not apply for registration, there should also be no restrictions.

In what cases is it possible to refuse admission to school?

Refusal to admit to school is possible, firstly, if there are no vacant places in the school and, secondly, when entering a school with in-depth study of certain academic subjects or for specialized training, or in a school that “implements educational programs integrated with additional pre-professional educational programs in the field of physical culture and sports «, refusal is possible if the child does not pass in the course of individual selection.

The legislation gives educational organizations the right to carry out individual selection when admitting students to the level of basic and secondary education (from 5 to 11 grades), when entering schools with in-depth study of certain academic subjects or for specialized training. The procedure for carrying out such a selection should be established at the level of the legislation of the constituent entity of the Russian Federation.

Also, educational organizations that implement educational programs integrated with additional pre-professional educational programs in the field of physical culture and sports can conduct a competition or individual selection.

Such schools can assess the ability to engage in a particular sport, as well as require a certificate of the absence of contraindications for engaging in the corresponding sport. (Clause 5,6, Art.

67 of the Federal Law «On Education in the Russian Federation»)

How is the procedure for transferring from school to school approved?

The transfer procedure was approved by Order of the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia dated 12.03.2014 N 177 «On approval of the Procedure and conditions for the transfer of students from one organization carrying out educational activities in educational programs of primary general, basic general and secondary general education, to other organizations carrying out educational activities in educational programs of the appropriate level and focus «:

5. In case of transfer of an adult student on his initiative or a minor student on the initiative of his parents (legal representatives), the adult student or parents (legal representatives) of a minor student:

- select the host organization;

- contact the selected organization with a request for the availability of free places, including using the Internet;

- in the absence of vacant places in the selected organization, they apply to the local authorities in the field of education of the corresponding municipal district, urban district to determine the host organization from among the municipal educational organizations;

- apply to the source organization with an application for the expulsion of the student in connection with the transfer to the receiving organization. The transfer application can be sent in the form of an electronic document using the Internet.

6. In the application of an adult student or parents (legal representatives) of a minor student for expulsion by transfer to the host organization, the following shall be indicated:

a) surname, name, patronymic (if any) of the student;

b) date of birth;

c) class and profile of training (if any);

d) the name of the host organization. In case of moving to another locality, only the settlement, the subject of the Russian Federation is indicated.

7. On the basis of an application by an adult student or parents (legal representatives) of a minor student about expulsion by transfer, the source organization within three days shall issue an administrative act on the expulsion of the student by transfer with an indication of the host organization.

8. The source organization issues the following documents to the adult student or parents (legal representatives) of the minor student:

student’s personal file;

documents containing information about the student’s progress in the current academic year (an extract from the class journal with the current marks and results of intermediate certification), certified by the seal of the original organization and the signature of its head (person authorized by him).

9. The requirement to provide other documents as a basis for enrollment of students in the host organization in connection with the transfer from the source organization is not allowed.

10. The documents specified in clause 8 of this Procedure are submitted by the adult student or the parents (legal representatives) of the minor student to the host organization, together with an application for the student’s enrollment in the specified organization in the order of transfer from the original organization and the presentation of the original document proving the identity of the adult student or parent ( legal representative) of a minor student.

Source: https://usperm.ru/content/kak-perevesti-rebenka-v-druguyu-shkolu

There is / there are (there’s / there’re)

This grammar topic teaches you how to work with the popular English construction there is / there are… Or, in other words, how to say: there is something, there is not something.

At the airport (there are) many rules. — There are a lot of rules at the airport.

There is no stadium in the town. — There isn’t a stadium in the town.

We use this construction when the sentence says that something is / not is somewhere. In other words, something is somewhere or something is not somewhere. To do this, in English, we use the construction there is / there are.

The word there in this construction will not change under any circumstances. Will change, according to the law of the genre, the verb to be in number and in tenses, we will talk below.

Here you need to be careful and not confuse the adverb there (there) and part of the construction there is / are… The difference will be visible in the context and translation: there, which is included in there is / are, will not even be translated, it just «is». For example:

There is only one restaurant there. — There (is) only one restaurant.

The second part of this construction is the already known verb «be» — to be in the form is and are (is for the singular, are for the plural).

There is a cake in the fridge. — There’s a cake in the fridge.

There’s a hole in my pocket. — There’s a hole in my pocket.

In the last sentence, we abbreviated there is to there’s, which is quite typical for spoken English.

There are two men in the room. “There are two men in the room.

There’re many mistakes in your test, you must do it over. — There are many mistakes in your test, you must redo it. (there are = there’re)

Often a student asks the question: why can’t I just say through a verb to be? For example:

Many mistakes are in your test.

Everything is very simple: such a sentence is grammatically correct, but the speaker will not say so, it will sound less natural to his ear. In addition, the design there is / are very popular with native speakers, so definitely not worth avoiding.

Interestingly, sentences with there is / are we translate from the end, the construction itself may not be translated at all, or it may be translated by the word «is».

There are many Italian foodstuffs in this shop. — There are many Italian products in this store.

There are seven days in a week. — There are seven days in a week.

Denial

It is a pleasure to work with this construction: to build negation, we

add a particle not or the word no after is / are

There isn’t any cold water in the fridge. — There is no cold water in the refrigerator.

There is no lamp in my son’s room. — There is no lamp in my son’s room.

You noticed that after there is not there must be an article a or an; after there is no we do not put either the article or any.

There are not two but three kids in their family. — Their family has not two, but three children.

There aren’t problems with this child. — There are no problems with this child.

There are no guests at the party. — There are no guests at the party.

Question

To build a question, you just need to rearrange the words in the construction itself. there is / are.

Is there a scarf in the wardrobe? — Is there a scarf in the closet?

Is there a dog in the car? «Is there a dog in the car?»

What is there on the table? — What (is) on the table?

Are there letters for me? — Are there any letters for me?

Are there students in the lecture hall? — Are there students in the classroom?

How many days are there in February? — How many days in February?

Very often the question arises in sentences where we need to list items in both the singular and the plural. What to do in these cases?

The choice of is or are will depend on the first noun immediately after the construction there is / are.

There is one bathroom and two bedrooms in my flat. — My apartment has two bedrooms and one bathroom.

As «bathroom» in the singular comes the first, we chose there is.

Source: https://speakasap.com/ru/en-ru/grammar/konstrukciya-there-is-are/

My school / Meine Schule

With this article, you can easily tell or write about your school in German.

Questions on the topic «School»: Wo liegt sie? — Where is she? Wie ist sie? — What is she? Welche Räume gibt es hier? — What are the offices in it? Wo liegen diese Räume? — Where are these offices? Wie kann sie sein? — What can it be? Welche Schulfächer gibt es in der 6. Klasse? — How many subjects are there in the 6th grade? Und in der 7. Klasse? — And in the 7th? Was nehmen die Kinder in die Schule mit? — What do children take with them to school?

Welchen Stundenplan wünschen sich einige Kinder? — What kind of schedule do some kids want?

School story in German:

Das Gebäude meiner Schule liegt in der ____ Straße, das ist ein zweistöckiges Gebäude.

My school is located on _____ Street. This is a two-story house.

Vor dem Schulgebäude befindet sich ein Schulhof. Da gibt es einen großen Sportplatz. Auf diesem Sportplatz können die Schüler während der Pausen und nach dem Unterricht spielen und Sport treiben.

There is a school yard in front of the school. There is a large sports ground. On this playground, students can play or exercise during breaks and after classes.

Durch die breite Eingangstür kommt man in die Vorhalle. Hier ist die Wardrobe. Im Erdgeschoss befindet sich das Schuldirektorskabinett, die Bibliothek, die Speisehalle, der Sportsaal und das Artzkabinett. Im Erdgeschoss sind auch Klassenzimmer. Hier lernen die Schüler der ersten-dritten Klassen.

Wide entrance doors lead to the lobby. Here is the wardrobe. On the ground floor there is the director’s office, library, dining room, gym and doctor’s office. There are also classrooms where pupils of the first and third grades study.

Im ersten Stock befindet sich das Lehrerzimmer und viele verschiedene Klassenzimmer. Das sind Physik-, Mathematik-, Chemie-, Geschichte-, Biologie- und Fremdsprachenkabinette.

On the second floor there is a teacher’s room and many different rooms: physics, mathematics, chemistry, history, biology and foreign languages.

Alle Klassenzimmersind groß, hell und gemütlich. Sie sind immer sauber. In den Klassenzimmern stehen Tische, Stühle, Bücherschränke. In jedem Kabinett hängt natürlich eine breite Tafel.

All offices are bright, large and comfortable. They are always taken away. The classrooms have tables, chairs, bookcases. A wide board hangs in each office.

Meine Schule hat gute Traditionen. Die Schulabende, Sportfeiertage, verschiedene Treffen sind immer sehr interessant.

My school has good traditions. School evenings, sports events and various meetings are always very interesting.

Presentation «My School» in German:

Source: http://startdeutsch.ru/poleznoe/temy/234-moya-shkola-meine-schule

History of words — School, Gymnasium, Lyceum

A lot of joyful and touching memories are associated with the words school, lyceum, gymnasium in the life of each student and his parents, a significant part of each person’s life is intertwined with studies, and, therefore, with school, etc.

Where did the words for the names of educational institutions come from?

History of the word «lyceum»

The history of the word «lyceum» dates back to ancient Greece. On the very edge of ancient Athens, near the temple of Apollo of Lycea, the great philosopher Aristotle founded a school called Lyceum in honor of the nearby temple. Translated from the ancient Greek, Lycean is «the destroyer of wolves.» The school has glorified itself over the centuries, and since then, significant educational institutions in many countries have been assigned the status of a lyceum.

Modern lyceums appeared in the 19th century, it was an average — between a university and a gymnasium — format of an educational institution. The term had the literal meaning of «grammar school of higher sciences.»

History of the word «school»

This word also came to us from Ancient Greece, where «schole» meant «pleasant pastime.» This concept did not imply absolute inaction, but clever and instructive conversations for which Greek philosophers have long been famous. Over time, these sages and thinkers acquired permanent students, and the «school» became associated with the educational process, and later with a room adapted for study.

The schools of the ancient Sumerians were called «Houses of tablets», they taught writing, writing poetry, writing music, the basics of astronomy, algebra and other sciences.

In the schools of Egypt, knowledge of more than 700 hieroglyphs was required, and for negligence they were punished with a whip.

Only boys studied in schools, for girls education was meant only at home.

History of the word «gymnasium»

The word «gymnasium» also originated in Ancient Greece, where it originally meant

«A place for gymnastic exercises.»

In this sense, the word found its application in the ancient cities of Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor and others. Over time, the concept of «gymnasium» included any physical exercise.

In educational institutions with this name, boys fenced, fisted, hunted on horseback, studied sciences such as hygiene, dance, music, rhetoric and mathematics.

Gymnasiums have changed over time, in a number of countries they have become educational institutions with a sports bias, in other countries, mainly in Europe, — places for studying the works of ancient authors.

Starting from the 19th century, girls began to study in gymnasiums.

Today, in most countries, the term «gymnasium» is understood as a secondary educational institution of general education.

Source: https://www.virtualacademy.ru/news/istoriya-slov-shkola-gimnaziya-licei/

Freshman, cake and zashkvar — how to understand what your child is talking about

Some of the phrases of adolescents sound like an adult set of sounds. To distinguish a hypozhor from a freshman and to speak the same language with children, you need to regularly replenish your vocabulary. Mel and Moscow International University have put together a small memo that will help you not to feel completely old.

Mela newsletter

We send our interesting and very useful newsletter twice a week: on Tuesday and Friday

Hype

What is on everyone’s lips. «Hype», «hype» (short for hypodermic needle, «medical needle») — in 1920s America meant the dose of heroin, as well as heroin itself and the euphoric effect it causes. In the second half of the 20th century, the meaning of the word was transformed into something like «hype», which rises on any occasion in the press, and thus became synonymous with the word «media», «media». Hence the famous rap group Public Enemy’s 1988 song «Don’t believe the hype.»

In the Russian language, the word took root several years ago thanks to the new wave of popularity of hip-hop culture and rap. And the hype went beyond the subculture in Russia after the rapper Purulent defeated the favorite of all generations, Oxxymiron, in a rap battle (a competition between two rappers).

Purulent — from an underground group called «Antihype», whose ideological component was freedom of creative expression and the absence of the pursuit of fashion.

Thus, “hype” (that is, try to do something because it’s in a trend, play on the trendy) also acquired negative connotations and gave rise to such a monster as “hypozhor” — a soulless, unprincipled exploiter of trends for the sake of self-promotion. …

- Kirkorov hype / on hype — Philip Kirkorov is in fashion thanks to his new video.

- Sobolev — haypozhor — Nikolai Sobolev does something for the sake of recognition and money, and not from the heart.

Flex

Show off, show off, show off. Comes from the English verb flex — «to bend, bend», and in slang means «to pretend, to be fake» — that is, «to brag about what you do not have.» Besides, in rap culture «flex» is to swing to the beat of the music (as a rule, it looks rather pompous).

Flex got widespread in 2014, when the American hip-hop duo Rae Sremmurd released the video hit No Flex Zone. has already gained more than 294 million views, which turns the meaning of the text: the guys who read about the flex-free space (that is, a place where you don’t need to brag about your expensive things and acquaintances) became superstars, got a good deal of hype, and now they can flex their achievement for the rest of their days …

In Russian, like the word «pontovatsya», it does not necessarily mean something bad — sometimes you can flex if you have something. There is also a mocking antonym — «low flex», when a person has absolutely nothing to brag about. In fact, there is no need to add “low”: depending on the context, the word “flexit” can be used both literally and figuratively.

- Sasha flexes on the dance floor — Sasha dances great.

- Petya is on low flex today — Petya looks and behaves monstrously.

Go

No connection with the ancient Chinese game. «Go» in slang is just a Russified version of the English verb to go, that is, «to go.» The phrase began to be used in online games. «Go, I created» means «I created a server in the game, join.» Now that’s what they say with any call to action. «Go» is often used in conjunction with another word, verb or noun, so it can mean both «go somewhere» or «let’s do something.»

With the word «go» do not use the prepositions «in» or «on» together with a noun. If we usually say “go to Vitya [to visit]”, “go to the concert”, then in the case of “go” it is correct to say “go Vitya”, “go kants”.

- Go LS — let’s discuss it in private messages.

- Go chill — let’s rest.

You can learn more about teenage slang on October 27 at a free lecture by Maxim Krongauz «What language do our children speak?» at the Moscow International University.

Lol, rofl, cake

It means «funny». Each of these words carries the same meaning, but there are often cases of simultaneous use of the first two — «lol kek» (sometimes teenagers jokingly add «cheburek»).

Lol — tracing paper from the English abbreviation LOL and stands for laugh out loud («laugh out loud»). Rofl or ROFL is very similar to LOL. This is also an abbreviation — rolling on the floor laughing, that is, «rolling on the floor laughing.»

It is permissible to use the verb form «rofl» — «roflit», that is, to joke.

Kek has gaming roots, and Kek is the same lol, but in the language of World of Warcraft players. In this multiplayer game, you can fight for different factions and at the same time communicate via an internal chat with rivals.

The word lol, sent by a representative of the alliance to a player from the horde, was automatically translated as kek, and thus the game simulated communication with a foreigner. There is also a version that kek comes from the Korean ke-ke-ke — the designation for laughter.

Teenagers keen on Korean culture brought cake to Russian as well.

The person using these words is not necessarily really laughing. In addition, each of them can not only demonstrate that a person is funny or ridicule someone, but also be used as surprise or even outrage.

- Lol, is this free? — Wow, is it really free?

- Yes, you roflish! — You’re not serious, are you?

Yell

Laugh, roll with laughter, clutching the stomach, to tears. «Yell» and its derivatives («yelled», «yelled», «yelled») in this meaning have been massively used for about three to four years.

All this time it occupies one of the first places in the hate lists («lists of hate») of those who insist on using the word in its original meaning — «shout out loud».

Defenders of slang fend off and recall the historical meaning of «digging, plowing the ground,» urging purists to use it that way.

The yell’s journey from scream to cackle is long and measured in decades, and other jargon will need to be remembered to trace this evolution. Like many things on the Russian-speaking Internet, it all started with threads (comment threads under the publication) on the forums.

If the user laughed at the picture in the thread, he lost. Thread by thread — and “losing” as a result of wordplay and typos turned into “yelling”, and then naturally reduced to “yelling”.

Gradually, the word came out of the underground and became widespread.

- I’m yelling / yelling — it’s very funny to me.

- Shout from you — you are funny (used both in the literal sense and with sarcasm).

Agrit

Simply get angry. It comes from gaming slang, and specifically from MMO games (Massively Multiplayer Online Game, that is, network games that several players can play at the same time), for example, Dota.

In them, in addition to heroes played by living people, there are mobs — inanimate monsters. To provoke aggression and then the attack of the mob means to make him aggressive, to «aggro» him, from aggression, «aggression».

In everyday life, it is used as a synonym for the word «angry, angry.»

- I wanted the best, but you get aggrieved.

- There, this grandmother would be angry at me, ruined my whole mood.

If your child is angry because he doesn’t know where to go after school, tell him about the Moscow International University workshop «From School to University: Territory of the Future.» On it, a teenager will decide on a future profession, and parents will receive answers to all questions about admission.

Zashchwar

«Unworthy business»; «To grind» means to engage in affairs that defame honor and reputation. Like much in modern Russian, the word comes from prison jargon.

Unlike other expressions that have become widely used and in the eyes of the public have practically lost their original criminal flair (such as «lawlessness», thanks to the active use in the media to describe social events in the 1990s), «zashkvar», at least few remember about the history of its origin, while it remains exclusively a slang expression, not recognized outside of youth subcultures.

Initially, this expression is associated with homophobic sentiments in the zone — a homosexual or one who was raped by inmates was called «greasy». Everything that the «greasy» touched was considered dirty, and the actions of such a person were automatically perceived as unworthy.

In its modern meaning, the word has been reduced to «zashkvar», has lost the connotation of hatred towards members of the LGBT + community, and in youth slang is already used to denote any shameful actions.

- His clothes are greedy — he dresses unfashionably.

- What Zemfira said about Monetochka is a complete mess — the singer Zemfira reacted inadequately to the music of the singer Monetochka.

Chan and Kun

«Chan» is a nice girl, «kun» is a nice guy. Users of Dvach (one of the most popular forums) contributed many words related to anime to the Internet, and the cartoons for teenagers and adults themselves have earned such authority among young people that even those who do not watch them began to use the terminology.

Originally, «chan» and «kun» are respectful prefixes to names in Japanese; «Chan» — an appeal to little girls or women of the same age, «kun» — to boys and men of the same age.

They will not call everyone in the Russian language the word «chan» or «tyanochka» — they will demonstrate sympathy; talking about the guy «kun» — will compliment his appearance.

- Lamp chan — a beautiful sweet girl.

- Coon is not needed — I can do without the guys.

Eshkere

This exclamation in itself does not carry any meaning and is used rather as an interjection. With its help, they express delight for any reason, often in an ironic sense. Etymologically, the word goes back to esketit — a simplification of the expression Let’s get it.

Depending on the context, the phrase means a whole range of emotions and calls from «let’s do it!» to «come on, come on!». The author of esketit — American rapper Lil Pump — shouted this word at his concerts out of an overabundance of emotions and without any specific purpose.

The author of the Russified version is the rapper FACE, who cemented the word in the track «Burger» among other interjections (such as «grrra» and «hey!»). Now the word is almost never used, but it can still be found in comments on social networks.

- Eshkere-ee! — I’m good! Cool! Blimey! Wow!

Freshman

Newbie, new face. In the original sense, it is translated from English as «freshman», although in everyday usage it is also used to designate high school students.

Since 2007, XXL hip-hop magazine regularly publishes a list of new faces in rap, which is called XXL Freshman List — this is how the word freshman began to be used in a new meaning.

Now this is the name not only for young people and school graduates, but also for recently appeared on the horizon and very promising rap artists, and indeed any new person in some business.

- Freshmen of this year are not at all happy.

- A typical one-day freshman, today he is a star, and tomorrow he will be nobody.

For high school students, parents and teachers, the workshop will host lectures, master classes and quests. More information about the program can be found here.

To get to the workshop, just register on the website and on October 27, come to the address st. Leningradsky prospect, 17.

Source: https://mel.fm/podrostki/9281346-slang

English[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- enPR: sko͞ol, IPA(key): /skuːl/

- (General Australian) IPA(key): /skuːɫ/

-

Audio (Received Pronunciation) (file) - Rhymes: -uːl

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English scole, from Old English scōl (“place of education”), from Proto-West Germanic *skōlā, from Late Latin schola, scola (“learned discussion or dissertation, lecture, school”), from Ancient Greek σχολεῖον (skholeîon), from σχολή (skholḗ, “spare time, leisure”), from Proto-Indo-European *seǵʰ- (“to hold, have, possess”). Doublet of schola and shul.

Compare Old Frisian skūle, schūle (“school”) (West Frisian skoalle, Saterland Frisian Skoule), Dutch school (“school”), German Low German School (“school”), Old High German scuola (“school”), German Schule (“school”), Bavarian Schui (“school”), Old Norse skóli (“school”).

Influenced in some senses by Middle English schole (“group of persons, host, company”), from Middle Dutch scole (“multitude, troop, band”). See school1. Related also to Old High German sigi (German Sieg, “victory”), Old English siġe, sigor (“victory”).

Alternative forms[edit]

- schole (obsolete)

Noun[edit]

school (countable and uncountable, plural schools)

- (Canada, US) An institution dedicated to teaching and learning; an educational institution.

-

Our children attend a public school in our neighborhood.

-

Harvard University is a famous American postsecondary school.

- Synonyms: academy, college, university

-

- (Britain) An educational institution providing primary and secondary education, prior to tertiary education (college or university).

-

2013 July 19, Mark Tran, “Denied an education by war”, in The Guardian Weekly, volume 189, number 6, page 1:

-

One particularly damaging, but often ignored, effect of conflict on education is the proliferation of attacks on schools […] as children, teachers or school buildings become the targets of attacks. Parents fear sending their children to school. Girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence.

-

-

- (UK) At Eton College, a period or session of teaching.

-

Divinity, history and geography are studied for two schools per week.

-

- Within a larger educational institution, an organizational unit, such as a department or institute, which is dedicated to a specific subject area.

-

We are enrolled in the same university, but I attend the School of Economics and my brother is in the School of Music.

- Synonyms: college, department, faculty, institute

-

- An art movement, a community of artists.

-

The Barbizon school of painters were part of an art movement towards Realism in art, which arose in the context of the dominant Romantic movement of the time.

-

- (considered collectively) The followers of a particular doctrine; a particular way of thinking or particular doctrine; a school of thought.

-

1963, Margery Allingham, chapter 3, in The China Governess[1]:

-